Abstract

AIM: Ursolic acid (UA) and oleanolic acid (OA) are triperpene acids having a similar chemical structure and are distributed wildly in plants all over the world. In recent years, it was found that they had marked anti-tumor effects. There is little literature currently available regarding their effects on colon carcinoma cells. The present study was designed to investigate their inhibitory effects on human colon carcinoma cell line HCT15.

METHODS: HCT15 cells were cultured with different drugs. The treated cells were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and their morphologic changes observed under a light microscope. The cytotoxicity of these drugs was evaluated by tetrazolium dye assay. Cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry (FCM). Data were expressed as means ± SEM and Analysis of variance and Student’ t-test for individual comparisons.

RESULTS: Twenty-four to 72 h after UA or OA 60 μmol/L treatment, the numbers of dead cells and cell fragments were increased and most cells were dead at the 72nd hour. The cytotoxicity of UA was stronger than that of OA. Seventy-eight hours after 30 μmol/L of UA or OA treatment, a number of cells were degenerated, but cell fragments were rarely seen. The IC50 values for UA and OA were 30 and 60 μmol/L, respectively. Proliferation assay showed that proliferation of UA and OA-treated cells was slightly increased at 24 h and significantly decreased at 48 h and 60 h, whereas untreated control cells maintained an exponential growth curve. Cell cycle analysis by FCM showed HCT15 cells treated with UA 30 and OA 60 for 36 h and 72 h gradually accumulated in G0/G1 phase (both drugs P < 0.05 for 72 h), with a concomitant decrease of cell populations in S phase (both drugs P < 0.01 for 72 h) and no detectable apoptotic fraction.

CONCLUSION: UA and OA have significant anti-tumor activity. The effect of UA is stronger than that of OA. The possible mechanism of action is that both drugs have an inhibitory effect on tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle arrest.

INTRODUCTION

Ursolic acid (UA) and oleanolic acid (OA) are triperpene acids having a similar chemical structure and are distributed widely in plants all over the world[1-20]. They are of interest to scientists because of their biological activities. OA has antifungal[21,22], insecticidal[23], anti-HIV[24,25], diuretic[26], complement inhibitory[27], blood sugar depression[28] and gastrointestinal transit modulating[29] activities. UA and OA also possess liver-protection[30-33] and anti-inflammatory effects[34-37]. In recent years, it was found that they had marked anti-tumor effects and exhibited cytotoxic activity toward many cancer cell line in culture[38-44]. Concerning their effects on colon carcinoma cells, there is little available so far in the current literature. The present study was designed to investigate their inhibitory effects on the human colon carcinoma cell line HCT15.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs and reagents

UA and OA were gifts from Professor Qing-Yao Yang, Department of Biology, Shanghai Teachers University. UA was extracted from Catharantus roseus L. with purity 99%, and OA from Ziziphus jujuba Mill. with purity 98%. The drugs were dissolved in 100% ethanol and then diluted 10 times with RPMI-1640 as the working solution, the final concentration of ethanol being less than 2%. Meª-2SO was purchased from the Sigma Company (USA).

Cell line and culture medium

HCT15 had been introduced from the NCI (USA) and was cultured and kept in this laboratory. The culture medium used was RPMI-1640 with 10% BSA (Huamei BG, Co Ltd, China).

Cell morphology observation

The morphology of the live cells was observed with an inverted microscope and the live and dead cells were identified after 1% Trypan blue staining[45]. Cell smear was stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE). Cytotoxicity identification with tetrazolium dye assay (MTT) 1.8 × 104 cells were inoculated to each of the 3 parallel wells on a 96-well plate and cultured over night. Different concentrations of UA and OA were added with a final volume of 0.2 mL and cultured for 72 more hours. MTT 20 μL (5 g/L) was added to each well. 4 h later samples were centrifuged and the supernatant was discarded. 180 μL Me2SO was added and the 570 nm absorbance was read. The mean value of each concentration (3 well) was obtained. Experiments were repeated three times[46].

The inhibition rate (%) = (1 - average rate of the treated/average of the control) × 100

Flowcytometric detection of cell cycle

Cell cycle was determined by flowcytometric assays[47]. To 1 mL of cell suspension with a concentration of 1 × 108/L, 30 μmol/L UA and OA 60 μmol/L were added. The cells were collected after being cultured for 36 h and 72 h, respectively. Collected cells were treated with absolute alcohol, then with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant discarded. 0.01% Rnase was added and samples were shaken for 10 min in a 37 °C water bath. Samples were stained with 0.05% propidium iodide for 10 min in 4 °C in darkness. The cell cycle distribution was detected with flowcytometer (Model FACSCALIBAR, B.D., USA) and 10000 cells were analyzed with MODFIT software.

Data analysis

Data are displayed as percentage of control condition. Data were expressed as means ± SEM and Analysis of variance and Student’ t-test for individual comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Changes in cell morphology

When HCT15 cells were treated with UA 60 μmol/L for 24 hours, a number of cells were found dead with a lot of cellular fragments. Among the intact cells, the dead ones accounted for more than 30%. Seventy-two hours later, the number of cells decreased significantly and the remaining cells became shrunken with disappearance of cellular refraction. On the smear stained with HE, a large amount of cellular fragments could be found. When treated with OA 60 μmol/L for 24 hours, a few cells were dead. There were relatively large amounts of cellular fragments and the dead cells accounted for about 15% at 72 h. Within 72 hours of either UA or OA treatment at a concentration of 30 μmol/L, a percentage of the cells became rugate at the periphery with blurred cellular borders. There was no obvious cell fragmentation. Relatively large amount of degenerated cells could be seen on HE stained smear, but degenerated cells with OA were markedly less than that with UA.

The cytotoxicity

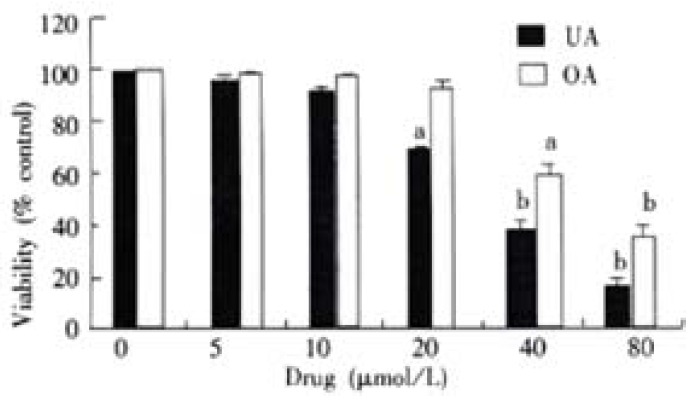

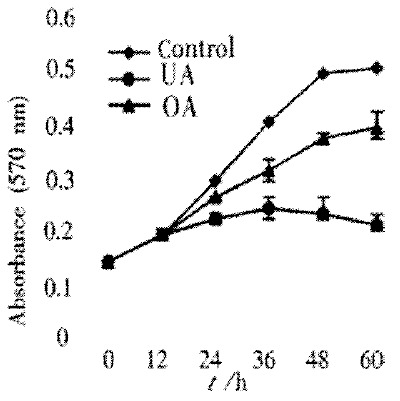

Cell viability was significantly decreased by treatment of UA and OA for 72 h in a dose-dependent manner. Their IC50 were 30 μmol/L for UA and 60 μmol/L for OA (Figure 1). Proliferation assay showed that proliferation of UA and OA-treated cells slightly increased at 24 h and significantly decreased at 48 h and 60 h, whereas untreated control cells maintained exponential growth curves (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effects of UA and OA on viability of colon carcinoma cell line. Relative cell viability was assessed by MTT assays. HCT15 cells were treated with various concentrations of UA and OA, respectively for 48 h. Data points represent mean values of 3 replicates, with bar indicating SEM. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control.

Figure 2.

Effects of UA and OA on proliferation of HCT15 cells. HCT15 cells were treated with 30 μmol/L UA and OA, respectively. The absorbance of 570 nm means the amount of living cells. Data points represent mean values of 3 replicates, with bar indicating SEM. P < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control.

Change in cell cycle

When treated the HCT15 cells with different doses of UA and OA for different times, the cell cycle obtained by FCM were as shown in Table 1. HCT15 cells treated with UA 30 μmol/L and OA 60 μmol/L for 12 h and 48 h gradually accumulated in G0/G1 phase, with a concomitant decrease of cell population in S phase and no detectable apoptotic fraction.

Table 1.

The cell cycle distribution of colon carcinoma cell line HCT15 treated with UA and OA (n = 3 -x ± s)

| Cell cycle |

Control |

UA (30 μmol/L) |

OA (60 μmol/L) |

|||

| 36 h | 72 h | 36 h | 72 h | 36 h | 72 h | |

| G0 + G1 | 62 ± 7 | 50 ± 7 | 70 ± 6 | 81 ± 10a | 68 ± 9 | 76 ± 6a |

| S | 31 ± 5 | 42 ± 8 | 22 ± 4a | 9 ± 3b | 26 ± 4 | 12 ± 3b |

| G2 + M | 7 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | 10 ± 2 | 6 ± 1 | 12 ± 2 |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs control.

DISCUSSION

UA and OA both belong to pentacyclic triterpenoid acids. They have a similar molecular structure, but have different sites of the methyl group on the E loop: if the methyl group at C19 of UA is moved to C20, it becomes OA. They are distributed widely in plants. In Korean traditional medicine, UA was used in anti-tumor therapy for a long time. Recently, it has been indicated in and outside China that UA and OA have a definitive antitumor activity by various routes[48-50].

This paper observed the anti-tumor activity of UA and OA on the HCT15 cells with some preliminary studies on their mechanism of action. With concentrations higher than their IC50, there was obvious cell death and fragmentation. With the IC50 concentration, a few cell fragments were found, but cell death was also obvious. To investigate the effects of UA and OA on the viability of HCT15 cells, HCT15 viability was assessed by MTT assay. In addition, we performed a proliferation assay to identify the anti-proliferation effect of UA and OA. The results showed that cell viability was significantly decreased in a concentration-dependent manner and proliferation was markedly inhibited by both drugs. It was shown that both drugs possessed an inhibitory effect on HCT15 cells. The activity was significantly stronger with UA than with OA. According to changes in HCT15 cell morphology, UA and OA have a direct cytotoxic effect on HCT15 cells. Also it has been reported that UA exhibited both cytotoxic and cytostatic activity in A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells[48] and OA has a cytotoxic activity against many cancer cell lines[43]. After incubation of the HCT15 cells with UA or OA for different times, the cell cycle was notably changed. When treated with IC50 concentration for 36 and 72 hours, the G0/G1 phase cells were gradually increased, with a concomitant decrease of cell population in S phase and no detectable apoptotic fraction. This result was in accordance with an inhibitory effect of UA and OA on HCT15 cells proliferation. These observations suggest that UA and OA may be involved in the action of the G0/G1 checkpoint and inhibition of DNA replication. Some studies have supported this inference. They have found that oleanane-type triterpenoids had inhibitory effects on DNA polymerase beta and DNA topoisomerases[51,52]. Many papers have demonstrated that UA can induce apoptosis[53,54]. But in the present study FCM assays showed that no apoptotic fraction in treated HCT15 cells. It is worth studying this further by using other methods of detecting apoptosis.

In conclusion, UA and OA have a definite anti-tumor activity on HCT15 cells. The effect of UA is stronger than that of OA. The possible mechanism of action is that both drugs have an inhibitory effect on tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle arrest.

The toxicity of UA and OA is low and their distribution in plants is extensive. Besides their anti-tumor activity, they also possess immuno-regulatory and liver-protective effects. Therefore, they have a bright future in clinical application. Further investigation to explore their potential in tumor treatment may prove to be worthwhile.

Footnotes

Edited by Pagliarini R

References

- 1.Zhu N, Sheng S, Sang S, Jhoo JW, Bai N, Karwe MV, Rosen RT, Ho CT. Triterpene saponins from debittered quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:865–867. doi: 10.1021/jf011002l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeoka G, Dao L, Teranishi R, Wong R, Flessa S, Harden L, Edwards R. Identification of three triterpenoids in almond hulls. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:3437–3439. doi: 10.1021/jf9908289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upadhyay RK, Pandey MB, Jha RN, Singh VP, Pandey VB. Triterpene glycoside from Terminalia arjuna. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2001;3:207–212. doi: 10.1080/10286020108041392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Si J, Gao G, Chen D. [Chemical constituents of the leaves of Crataegus scabrifolia (Franch.) Rehd] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:422–43, 448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo X, Zhang L, Quan S, Hong Y, Sun L, Liu M. [Isolation and identification of Triterpenoid compounds in the fruits of Chaenomeles lagenaria (Loisel.) Koidz] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:546–57, 576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Zhu Z, Wang C, Yang J. [Determination of oleanolic acid and total saponins in Aralia L] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:518–21, 574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi L, Cai Z, Wu G, Yang S, Ma Y. [RP-HPLC determination of water-soluble active constituents and oleanolic acid in the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum Ait. collected from various areas] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:77–9, 127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding H, Wang Y, Wang S, You W. [Quantitative determination of ursolic acid in Herba cynomorii by ultraviolet spectrophotometry] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:102–13, inside back cover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou F, Liang P, Zhou Q, Qin Z. [Chemical constituents of the stem and root of Syzygium buxifolium Hook. Et Arn] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1998;23:164–15, 192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamel MS, Mohamed KM, Hassanean HA, Ohtani K, Kasai R, Yamasaki K. Acylated flavonoid glycosides from Bassia muricata. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:1259–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar E, Riaz M, Malik A. Ursene type nortriterpene from Debregeasia salicifolia. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:382–385. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui BS, Sultana I, Begum S. Triterpenoidal constituents from Eucalyptus camaldulensis var. obtusa leaves. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:861–865. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad D, Juyal V, Singh R, Singh V, Pant G, Rawat MS. A new secoiridoid glycoside from Lonicera angustifolia. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:420–424. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou AJ, Yang H, Jiang B, Zhao QS, Lin ZW, Sun HD. A new ent-kaurane diterpenoid from Isodon phyllostachys. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:417–419. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye WC, Zhang QW, Liu X, Che CT, Zhao SX. Oleanane saponins from Gymnema sylvestre. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:893–899. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Setzer WN, Setzer MC, Bates RB, Jackes BR. Biologically active triterpenoids of Syncarpia glomulifera bark extract from Paluma, north Queensland, Australia. Planta Med. 2000;66:176–177. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-11129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen LH, Harrison LJ. Xanthones and triterpenoids from the bark of Garcinia vilersiana. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Camino MC, Cert A. Quantitative determination of hydroxy pentacyclic triterpene acids in vegetable oils. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:1558–1562. doi: 10.1021/jf980881h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CW, Wu TS, Hsieh YS, Kuo SC, Chao PD. Terpenoids of Syzygium formosanum. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:327–328. doi: 10.1021/np980313w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vo DH, Yamamura S, Ohtani K, Kasai R, Yamasaki K, Nguyen TN, Hoang MC. Oleanane saponins from Polyscias fruticosa. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:451–457. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)00618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang HQ, Hu J, Yang L, Tan RX. Terpenoids and flavonoids from Artemisia species. Planta Med. 2000;66:391–393. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong TS, Hwang EI, Lee HB, Lee ES, Kim YK, Min BS, Bae KH, Bok SH, Kim SU. Chitin synthase II inhibitory activity of ursolic acid, isolated from Crataegus pinnatifida. Planta Med. 1999;65:261–263. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquina S, Maldonado N, Garduño-Ramírez ML, Aranda E, Villarreal ML, Navarro V, Bye R, Delgado G, Alvarez L. Bioactive oleanolic acid saponins and other constituents from the roots of Viguiera decurrens. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashiwada Y, Nagao T, Hashimoto A, Ikeshiro Y, Okabe H, Cosentino LM, Lee KH. Anti-AIDS agents 38. Anti-HIV activity of 3-O-acyl ursolic acid derivatives. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1619–1622. doi: 10.1021/np990633v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma C, Nakamura N, Hattori M, Kakuda H, Qiao J, Yu H. Inhibitory effects on HIV-1 protease of constituents from the wood of Xanthoceras sorbifolia. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:238–242. doi: 10.1021/np9902441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarez ME, María AO, Saad JR. Diuretic activity of Fabiana patagonica in rats. Phytother Res. 2002;16:71–73. doi: 10.1002/ptr.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assefa H, Nimrod A, Walker L, Sindelar R. Enantioselective synthesis and complement inhibitory assay of A/B-ring partial analogues of oleanolic acid. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1619–1623. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshikawa M, Matsuda H. Antidiabetogenic activity of oleanolic acid glycosides from medicinal foodstuffs. Biofactors. 2000;13:231–237. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M. Effects of oleanolic acid glycosides on gastrointestinal transit and ileus in mice. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yim TK, Wu WK, Pak WF, Ko KM. Hepatoprotective action of an oleanolic acid-enriched extract of Ligustrum lucidum fruits is mediated through an enhancement on hepatic glutathione regeneration capacity in mice. Phytother Res. 2001;15:589–592. doi: 10.1002/ptr.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saraswat B, Visen PK, Agarwal DP. Ursolic acid isolated from Eucalyptus tereticornis protects against ethanol toxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. Phytother Res. 2000;14:163–166. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(200005)14:3<163::aid-ptr588>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latha PG, Panikkar KR. Modulatory effects of ixora coccinea flower on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice. Phytother Res. 1999;13:517–520. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199909)13:6<517::aid-ptr524>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong HG. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2E1 expression by oleanolic acid: hepatoprotective effects against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury. Toxicol Lett. 1999;105:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ismaili H, Tortora S, Sosa S, Fkih-Tetouani S, Ilidrissi A, Della Loggia R, Tubaro A, Aquino R. Topical anti-inflammatory activity of Thymus willdenowii. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001;53:1645–1652. doi: 10.1211/0022357011778250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giner-Larza EM, Máñez S, Recio MC, Giner RM, Prieto JM, Cerdá-Nicolás M, Ríos JL. Oleanonic acid, a 3-oxotriterpene from Pistacia, inhibits leukotriene synthesis and has anti-inflammatory activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;428:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryu SY, Oak MH, Yoon SK, Cho DI, Yoo GS, Kim TS, Kim KM. Anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory triterpenes from the herb of Prunella vulgaris. Planta Med. 2000;66:358–360. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baricevic D, Sosa S, Della Loggia R, Tubaro A, Simonovska B, Krasna A, Zupancic A. Topical anti-inflammatory activity of Salvia officinalis L. leaves: the relevance of ursolic acid. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Xu LZ, Zhu WP, Zhang TM, Li XM, Jin AP, Huang KM, Li DL, Yang QY. Effects of ursolic acid and oleanolic acid on Jurkat lymphoma cell line in vitro. Zhongguo Aizheng Zazhi. 1999;9:395–397. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollósy F, Idei M, Csorba G, Szabó E, Bökönyi G, Seprödi A, Mészáros G, Szende B, Kéri G. Activation of caspase-3 protease during the process of ursolic acid and its derivative-induced apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3485–3491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rios MY, González-Morales A, Villarreal ML. Sterols, triterpenes and biflavonoids of Viburnum jucundum and cytotoxic activity of ursolic acid. Planta Med. 2001;67:683–684. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martín-Cordero C, Reyes M, Ayuso MJ, Toro MV. Cytotoxic triterpenoids from Erica andevalensis. Z Naturforsch C. 2001;56:45–48. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-1-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauthier F, Taillet L, Trouillas P, Delage C, Simon A. Ursolic acid triggers calcium-dependent apoptosis in human Daudi cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:737–745. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko HH, Yen MH, Wu RR, Won SJ, Lin CN. Cytotoxic isoprenylated flavans of Broussonetia kazinoki. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:164–166. doi: 10.1021/np980281c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cha HJ, Park MT, Chung HY, Kim ND, Sato H, Seiki M, Kim KW. Ursolic acid-induced down-regulation of MMP-9 gene is mediated through the nuclear translocation of glucocorticoid receptor in HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:771–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mascotti K, McCullough J, Burger SR. HPC viability measurement: trypan blue versus acridine orange and propidium iodide. Transfusion. 2000;40:693–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40060693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Xu LZ, He KL, Guo WJ, Zheng YH, Xia P, Chen Y. Reversal effects of nomegestrol acetate on multidrug resistance in adriamycin-resistant MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:253–263. doi: 10.1186/bcr303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao WX, Cheng QM, Fei XF, Li SF, Yin HR, Lin YZ. A study of preoperative methionine-depleting parenteral nutrition plus chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:255–258. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollósy F, Mészáros G, Bökönyi G, Idei M, Seprödi A, Szende B, Kéri G. Cytostatic, cytotoxic and protein tyrosine kinase inhibitory activity of ursolic acid in A431 human tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:4563–4570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi CY, You HJ, Jeong HG. Nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by oleanolic acid via nuclear factor-kappaB activation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:49–55. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subbaramaiah K, Michaluart P, Sporn MB, Dannenberg AJ. Ursolic acid inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2399–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wada S, Iida A, Tanaka R. Screening of triterpenoids isolated from Phyllanthus flexuosus for DNA topoisomerase inhibitory activity. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:1545–1547. doi: 10.1021/np010176u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng JZ, Starck SR, Hecht SM. DNA polymerase beta inhibitors from Baeckea gunniana. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1624–1626. doi: 10.1021/np990240w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi BM, Park R, Pae HO, Yoo JC, Kim YC, Jun CD, Jung BH, Oh GS, So HS, Kim YM, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate inhibits ursolic acid-induced apoptosis via activation of protein kinase A in human leukaemic HL-60 cells. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;86:53–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2000.d01-10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim DK, Baek JH, Kang CM, Yoo MA, Sung JW, Chung HY, Kim ND, Choi YH, Lee SH, Kim KW. Apoptotic activity of ursolic acid may correlate with the inhibition of initiation of DNA replication. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:629–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]