Abstract

AIM: To investigate the role of DNA-PKcs subunits in radiosensitization by hyperthermia on hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cell lines.

METHODS: HepG2 cells were exposed to hyperthermia and irradiation. Hyperthermia was given at 45.5 °C. Cell survival was determined by an in vitro clonogenic assay for the cells treated with or without hyperthermia at various time points. DNA DSB rejoining was measured using asymmetric field inversion gel electrophoresis (AFIGE). The DNA-PKcs activities were measured using DNA-PKcs enzyme assay system.

RESULTS: Hyperthermia can significantly enhance irradiation-killing cells. Thermal enhancement ratio as calculated at 10% survival was 2.02. The difference in radiosensitivity between two treatment modes manifested as a difference in the α components and the almost same β components, which α value was considerably higher in the cells of combined radiation and hyperthermia as compared with irradiating cells (1.07 Gy-1 vs 0.44 Gy-1). Survival fraction showed 1 logarithm increase after an 8-hour interval between heat and irradiation, whereas DNA-PKcs activity did not show any recovery. The cells were exposed to heat 5 min only, DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited at the nadir, even though the exposure time was lengthened. Whereas the ability of DNA DSB rejoining was inhibited with the increase of the length of hyperthermic time. The repair kinetics of DNA DSB rejoining after treatment with Wortmannin is different from the hyperthermic group due to the striking high slow rejoining component.

CONCLUSION: Determination with the cell extracts and the peptide phosphorylation assay, DNA-PKcs activity was inactivated by heat treatment at 45.5 °C, and could not restore. Cell survival is not associated with the DNA-PKcs inactivity after heat. DNA-PKcs is not a unique factor affecting the DNA DSB repair. This suggests that DNA-PKcs do not play a crucial role in the enhancement of cellular radiosensitivity by hyperthermia.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains one of the most difficult tumors to treat[1-15]. About 90% of patients are unresectable at presentation because of tumor size, location, or underlying parechymal disease[16-20]. Those patients are sometimes recommended to receive non-surgical therapies, including radiotherapy[21-28], radiofrequency hyperthermia[29,30], or the hyperthermia as an adjuvant to radiation in the treatment of local and regional disease[31]. Thermoradiotherapy currently offers the most significant advantages in the treatment of certain types of cancer[32]. Numerous uncontrolled studies have been performed in which comparable lesions were treated with either radiation alone or combined with hyperthermia[33]. Although many of these studies are difficult to evaluate, they give strong evidence that adjuvant heat treatment increases the probability of complete response and, consequently, tumor control. The cause of this radiosensitization has not been firmly established, however, in part this sensitization is thought to be through inhibition of repair of radiation induced DNA damage[34-36]. The mode of this repair inhibition is still unclear. Protein denaturation and aggregation appear to be the most relevant process underlying the biological effects of hyperthermia.

Several studies have shown that hyperthermia could inhibit both recovery of radiation induced potentially lethal radiation damage (PLD) and sublethal damage (SLD)[37]. Such inhibition was dependent on the time, temperature, and sequence of hyperthermia treatment. It was shown that polymerase β may be one of the mechanisms involved in thermo-radiosensitization[38]. In addition, DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) plays a central role in the repair of DSB[39]. DNA-PKcs is a complex consisting of three proteins: Ku70 and Ku80 and the catalytic subunit, DNA-PKcs[39]. The Ku70 and Ku80 proteins are involved in binding to the DNA ends at DSB and this binding activates the DNA-PKcs[39]. A possible mechanism for hyperthermic radiosensitization is mediated through the heat lability of Ku subunits of DNA-PKcs[40]. To support this mechanism, we have used HepG2 cells to study the relationship of DNA-PKcs activity in thermal radiosensitization and the kinetics of DNA DSB rejoining with the time after irradiation, addressing the main question that the role of DNA-PKcs subunits in thermal radiosensitization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HepG2 cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and was grown in MEM medium supplemented with 100 × 103 U•L-1 penicillin, 100 mg•L-1 streptomycin, and 100 mL•L-1 fetal calf serum at 37 °C in a humidified incubator, at an atmosphere of 50 mL•L-1 CO2 and 950 mL•L-1 air. Cells were maintained in a phase of nearly logarithmic growth by subculturing every 4 d at an initial concentration of 2 × 105 cells in T-25 tissue culture flasks for both clonogenic assay and DNA DSB rejoining studies, 2 × 106 cells in T-75 tissue culture flasks for determination of DNA-PKcs activity. The cells were passed several times through a 20-gauge needle in syringe to make the clamp cells single in each subculturing.

Hyperthermia treatment

Hyperthermia was carried out by sealing cell cultures grown in tissue culture flasks with parafilm and immersing the flasks into a temperature control waterbath (± 0.05 °C). The continuous heating experiments ranged from 5 to 30 min at an interval of 5 min. After heating at 45.5 °C, flasks were put into ice for 10 min for the DNA DSB rejoining and DNA-PKcs activity studies, or a 37 °C waterbath for 5 min to equilibrate to 37 °C for clonogenic assay. At this point, if required, the flasks were irradiated on the ice.

Radiation treatment

Cells in flasks were irradiated using a Pantak X-ray machine operated at 320 kV, 10 mA with a 2 mm Al filter (effective photon energy about 90 kV), at a dose rate of 2.7 Gy·Min⁻¹. Dosimetry was performed with a Victoreen dosimeter which was used to calibrate an in-field ionization monitor.

Clonogenic survival

Cells were trypsinized at 37 °C for 10 min, and pipetted 7 times to keep the clamp cells to be single cell suspension using 20-gauge needle and 5 mL syringe in 5 mL medium. The single cell suspension was adjusted and seeded into 60-mm tissue culture dishes at various densities aiming at 20-200 colonies per dish. Cells were irradiated at room temperature in 5 mL medium and were immediately kept at 37 °C, 50 mL•L-1 CO2 incubator for 13 d. Cells were stained with crystal violet and colonies of more than 50 cells were counted. The radiation results presented for heat plus X-rays were corrected for the cell killing caused by heat alone.

Induction and repair of DNA DSB

Cells for DNA DSB repair experiments were labeled with 3.7 MBq·L-1.14C-thymidine plus 2.5 μmol•L-1 cold thymidine for the entire period of growth. The cells were used 3 d later as the concentration reached 1 × 106 cells/T-25 flask. When indicated by the experimental protocol, cells were treated with 20 μmol•L-1 Wortmannin for 1 hour or hyperthermia at 45.5 °C for various times before irradiation. Cells were cooled to 4 °C prior to irradiation and were irradiated on ice. After irradiation, the medium was replaced with fresh growth medium pre-warm at 42 °C to rapidly restore to 37 °C, and then cells were quickly returned to the incubator at 37 °C to allow for repair. Cells were prepared for DNA DSB analysis at various time intervals thereafter.

After completion of the repair time interval, cells were trypsinized for 90 min in ice for the first 4 h, and 10 min at 37 °C at later points. The cells were collected with 5 mL cold medium, centrifuged at 4 °C, and washed with 5 mL cold serum-free medium. The cells were resuspended in 165 μL cold serum-free medium. This cell suspension was mixed with an equal volume of 10 g•L-1 agarose (InCert agarose, FMC) to reach a concentration of 3 × 109 cells·L-1. The cell-agarose suspension was then pipetted into a 3 mm diameter glass tubes and placed into ice to allow for solidification. The solidified cell-agarose suspension was extruded from the glass tubes and cut into 3 × 5 mm cylindrical blocks containing approximately 1.5 × 105 cells/block[41]. Blocks were then placed in lysis buffer containing 10 mmol•L-1 Tris, pH8.0, 50 mmol•L-1 NaCl, 0.5 mol•L-1 EDTA, 2 g•L-1 N-Lauryl Sarcosyl (NLS), A 0.1 g•L-1 proteinase E & O, and incubated first at 4 °C for 45 min and then at 50 °C for 16-18 h. Following lysis, agarose blocks were washed for 1 hour at 37 °C in a buffer containing 10 mmol•L-1 Tris, pH8.0 and 0.1 mol•L-1 EDTA, and were then treated for 1 hour at 37 °C in the same buffer, at pH7.5, with 0.1 g•L-1 RNAase A. Cells from identically treated non-irradiated cultures were also processed at pre-defined times to determine the signal generated by non-irradiated cells as background. For dose response, a similar protocol was also employed to determine the induction of DNA DSB except that in this case cells were embedded in agarose prior to irradiation with various doses on the ice, and were lysed immediately thereafter.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Asymmetric field inversion gel electrophoresis (AFIGE) was carried out in 5 g•L-1 Seakem agarose (FMC), cast in the presence of 0.5 mg•L-1 ethidium bromide, in 0.5 × TBE (45 mmol•L-1 Tris, pH8.2, 45 mmol•L-1 Boric Acid, 1 mmol•L-1 EDTA) at 10 °C for 40 h. During this time, cycles of 1.25 V·cm-1 for 900 s in the direction of DNA migration alternated with cycles of 5.0 V·cm-1 for 75 s in the reverse direction. The agarose gels were quantified to estimate DNA damage by means of a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Gels were dried and exposed to radiation-sensitive screens for 48-96 h. DNA DSB was quantitated by calculating the fraction of activity released (FAR) from the well into the lane in irradiated and non-irradiated samples. The FAR measured in non-irradiated cells (background) was subtracted from the results shown with irradiated cells. Gel images were obtained either by photographing ethidium bromide-stained gels under UV light, or from the PhosphorImager.

Repair kinetics were fitted assuming two exponential components of rejoining according to the equation[42] FAR = Ae-bt +Ce-dt. The first term in the equation was fitted to the slow and the second to the fast component of rejoining. Fitting was achieved using the non-linear regression analysis routines of a commercially available software package (SAS). Parameters A and C describe the amplitudes, and parameter b and d and the rate constants of the slow and the fast components of rejoining, respectively. From these parameters the half-time for the rejoining of the slow and the fast components were calculated as t50,fast = ln2/b, and t50,slow = ln2/d, respectively. The fraction of DSB rejoined by fast kinetics was calculated as Ffast = A/A+C and Fslow = C/A+C.

Determination of DNA-PKcs activity

Cell extract preparation: Cells (2 × 106) were grown in the T-75 tissue culture flask for 5 d. After treatment, about 30 × 106 cells were collected in cold PBS after being trypsinized at 37 °C for 10 min, centrifuged at 4 °C, and resuspended with 1 mL cold PBS and transferred to Eppendorf tube. After spun 1500 r•min⁻¹ for 5 min at 4 °C, PBS was replaced with 0.5 mL (about 4 volumes of cells) hypotonic buffer containing 10 mmol•L-1 HEPES KOH pH7.9 at 4 °C, 5 mmol•L-1 KCl, 1.5 mmol•L-1 MgCl2, 20 mmol•L-1 b-Glu, 0.2 mmol•L-1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.5 mmol•L-1 dithiothreitol (DTT). The cells were put on ice for 10 min, frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed for 3 cycles, adjusted salt being 50 mmol•L-1 KCl in hypotonic buffer (16 μL, 1.6 mol•L-1 KCl), and allowed to stay for 10 min on ice. After centrifugation (40 min at 14000 r•min⁻¹ at 4 °C), cytoplasm extract was obtained from the collection of supernatants. Nuclei were resuspended with 50 mmol•L-1 KCl hypotonic buffer (100 mL), the salt was adjusted to 400 mmol•L-1 KCl with 3 mol•L-1 KCl in the buffer (13 μL), mixed in the cold room (4 °C) for 30 min. After centrifuged at 14000 r•min⁻¹ for 15 min at 4 °C, nucleic extract was obtained from the collection of supernatants. Protein concentration of both cytoplasm and nucleic extracts were determined using Bio-Rad protein II assay.

Activity assay of DNA-PKcs: In 1.5 mL microfuge tube, the reaction buffer was set up on ice in a mixture containing 4 μL 5 × kinase buffer (250 mmol•L-1 HEPES, pH7.5, 50 mmol•L-1 MgCl2, 1 mmol•L-1 EGTA, 5 mmol•L-1 DTT), 2 μL 10 × substrate peptide (2 mmol•L-1), 2 μL 10 × sonacated calf thymus DNA (100 μg•L-1), 2 μL (7.4 MBq·L-1) of (γ-32P) ATP. In this reaction buffer mixture, an equal volume (5 μg in 10 μL) of nucleic extract was added and mixed quickly. The optimal incorporation time was found to be 15 min at 30 °C. After incubation, the reaction was terminated with 20 μL stop solution (300 g•L-1 acetic acid, 1 mmol•L-1 ATP). Out of 40 μml reaction mixture, 20 μL was spotted on Watermann P81 phosphocellulose paper, and washed 4 times with 150 g•L-1 acetic acid for 15 min each time. The filters were placed in scintillation vials, and the adsorbed radioactivity was quantitated. To calculate the specific activity of (γ-32P) ATP, we removed 5 μL from any two reaction tubes, and added to scintillation vial to count. Calculation of the specific activity of (γ-32P) ATP in cpm/pmol is shown as follows (40/5) × X/10000 = X/1250 [40 is the sum of the reaction volume (20 μL) + stop buffer (20 μL), 5 is the volume (μL) used for the specific activity of (γ-32P) ATP, X is the average counts, and 10000 is the number of pmoles of ATP in the reaction]. Calculation of incorporated ATP (pmol) is (CPMreaction with DNA-CPMreaction without DNA)/The specific activity of [γ-32P] ATP in 1012 cpm•mol⁻¹.

RESULTS

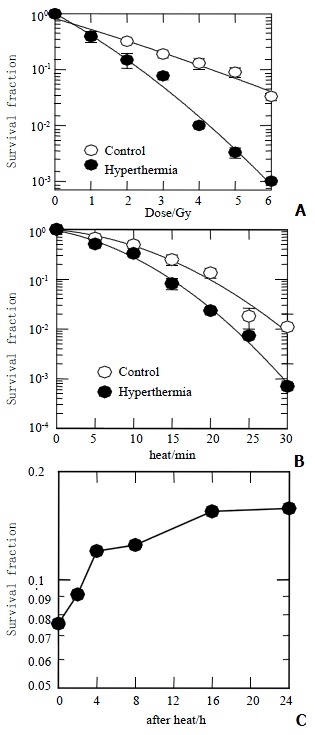

The survival curves of HepG2 cell exposure to X-ray combined with or without hyperthermia are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B. The mean dose of survival fraction at 2 Gy (SF2) was 0.230 ± 0.033 for the group of radiation alone, and 0.148 ± 0.043 for the radiation combined with hyperthermia group. The linear-quadratic model S = e-αD-βD2 was applied to describe the survival data in Figure 1, where S is the fraction of cells surviving a dose D, and α and β are constants. The α and β values are 0.805 ± 0.037 Gy-1 and 0.072 ± 0.012 Gy-2 for the group of radiation alone, and 0.950 ± 0.018 Gy-1 and 0.010 ± 0.001 Gy-2 for the group of radiation combined with hyperthermia. The α/β ratios are 11.2 Gy and 97 Gy for the groups of radiation alone and combination modes, respectively. Thermal enhancement ratio as calculated at 10% survival (TER10) was 2.02. The difference in radiosensitivity between these two groups can be interpreted as being due to some phenomena, which manifest as a difference in the a components. Figure 1B shows the survival curves for cells exposed for various periods of time to 45.5 °C. The combination of hyperthermia with 3 Gy X-ray significantly improved the killing effects in comparison of hyperthermia alone. Figure 1C shows a combination of hyperthermia at 45.5 °C for 15 min first and then 3 Gy of X-rays. When the time intervals between hyperthermia and radiation in existence, the cell survival increased with the time interval increase within 8 h, but no significant change was observed 8 h later.

Figure 1.

Survival fraction of HepG2. A: Exposure to X-rays combined with (close circles) or without (open circles) 45.5 °C for 15 min; B: Heat-induced clonogenic cell death as a function of time combined with (close circles) or without (open circles) 3 Gy of X-rays; C: Irradiated with 3 Gy of X-rays at different hours after heat of 15 min at 45.5 °C.

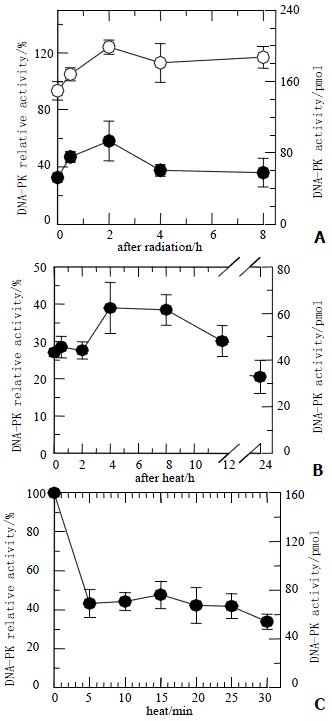

The DNA-PKcs activity was measured before and after irradiation with 40 Gy X-ray, or hyperthermia for 20 min at 45.5 °C, or both. All of DNA-PKcs values were expressed with both relative percentage at left side and pmol at right of figures in this paper. Figure 2A shows that DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited by about 70% at heating. Radiation stimulated DNA-PKcs activity increased about 30% in the cells treated with or without hyperthermia at the 2nd hour. In order to determine whether the level of DNA-PKcs activity recovers its activity after hyperthermia, the time point was extended to 24 h to correspond to clonogenic survival in Figure 1C. As shown in Figure 2B, no restore was found in DNA-PKcs activity up to 24 h. The DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited after the cells exposed to heat at 45.5 °C for 5 min (Figure 2C). The DNA-PKcs activity remained at almost the same level despite the hyperthermic time extending.

Figure 2.

DNA-PKcs activity of HepG2 cells. A: Cells were heated at 45.5 °C for 20 min and then received 40 Gy of X-rays (closed circles) or irradiated with 40 Gy of X-rays only (open circles). At various periods, DNA-PKcs activity in heated cells was inhibited, and kept at low level about 30%. The DNA-PKcs activity in both groups showed slight increase; B: After heated at 45.5 °C for 20 min, DNA-PKcs activity was still inhibited at various periods; C: DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited after exposure to heat at 45.5 °C for 5 min, even though the heat time was prolonged, DNA-PKcs activity levels still remained unchanged.

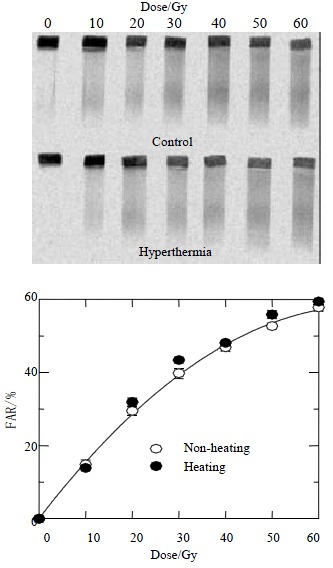

To understand the role of DNA-PKcs subunits in radiosensitization by hyperthermia, induction of X-ray induced DNA DSB was measured by AFIGE. Figure 3 shows the dose response curves for HepG2 cells receiving radiation combined with or without hyperthermia. The upper panel shows a typical gel scanned with 14C-TdR, while the lower panel shows the quantitative data as described in the Methods. The FAR, a measure of DNA DSB presence, increased almost linearly with dose up to 30 Gy but bended downward at higher doses. Similar increases in FAR as a function of dose were observed in radiation alone or combined with hyperthermia, suggesting similar yields of DNA DSB.

Figure 3.

Dose response curves for HepG2 cells received radiation combined with or without hyperthermia. The upper panel shows a typical gel scanned with 14C-TdR, while the lower panel shows quantitative data as described in the Methods. The FAR increases almost linearly with dose up to 30 Gy but bends downward at higher doses. Similar increases in FAR as a function of dose are observed in radiation alone or combined with hyperthermia, suggesting similar yields of DNA DSBs.

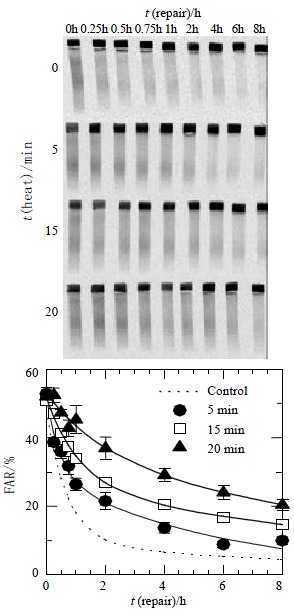

The rate of rejoining of radiation-induced DNA DSB was subsequently examined to determine whether differences in repair between radiation alone and combined with hyperthermia for different periods of time account for the results shown in Figure 2A that the DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited after heat. Figure 4 shows that DNA DSB repairs kinetics in HepG2 cells. Cells were irradiated with 40 Gy and prepared for AFIGE after various periods of incubation at 37 °C to allow for repair. The upper panel in the Figure shows a typical AFIGE gel, while the lower panel shows its quantification as described in the Methods. The rejoining of DNA DSB decreased with increasing the lengths of hyperthermic time at 45.5 °C. Table 1 shows that the half-time for rejoining of the fast components was shorter in the control group or exposure to heat for 5 min than the exposure to longer time (15 and 20 min). However, the half-time of slow components in both control and hyperthermic groups were almost the same which ranged between 7 and 9 h.

Figure 4.

DNA DSBs repair kinetics in HepG2 cells. Cells were irradiated with 40 Gy and prepared for AFIGE after various periods of incubation at 37 °C to allow for repair. The upper panel in the Figure shows a typical AFIGE gel, while the lower panel shows its quantification as described in the materials and Methods. The rejoining of DNA DSBs was decreasing with the increase of the lengths of hyperthermic time at 45.5 °C.

Table 1.

The half-time and fraction of DNA DSB rejoined by fast and slow kinetics

| T50, fast | T50, slow | Ffast | Fslow | |

| Control | 0.49 | 7.07 | 0.80 | 0.20 |

| 5 min | 0.33 | 4.15 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| 15 min | 0.92 | 9.37 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| 20 min | 1.25 | 9.24 | 0.30 | 0.70 |

| 20 mmol•L-1 Wort. | 0.87 | 7 × 108 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

Wortmannin inhibits the entire family of PI-3 kinases and probably also other cellular kinases. To evaluate the contribution of DNA-PKcs to Wortmannin-induced inhibition of DNA DSB rejoining, we searched for Wortmannin treatment, which is able to compare heat-induced inhibition of DNA DSB rejoining. Figure 5 indicates the kinetics of DNA DSB rejoining after treatment with Wortmannin. We found that the slow rejoining component is strikingly high. The deficiency of DNA DSB rejoining was found in Wortmannin treatment cells after 2 h. These results are different from those in hyperthermic groups.

Figure 5.

The kinetics of DNA DSBs rejoining after treatment with Wortmannin. The slow rejoining component is strikingly high. The deficiency of DNA DSBs rejoining was found in Wortmannin treatment cells after 2 h.

DISCUSSION

Tumors of liver are among the most common malignancies in the world. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma was the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths behind gastric cancer in China. Surgical resection has been accepted as the only curative therapy for primary liver cancer. Unfortunately, most patients were surgically unresectable[1-28]. Hyperthermia[29,30], radiation therapy[21-28], or combination of both[31,32] were introduced as an alternative therapeutic approach. The cause of this radiosensitization has not been firmly established.

The inhibition of DNA-PKcs by hyperthermia has been demonstrated in several studies[40,43,44]. In our series, DNA-PKcs activity was inhibited by about 60% after hyperthermia at 45.5 °C for 5 min, and no significant change was found after increasing hyperthermia time. This result is similar to other reports[40,43]. Interestingly, the rejoining of DNA DSB was decreasing with the increase of the hyperthermic time at 45.5 °C. The decrease of DNA DSB repair did not correspond proportionally to the heat inhibited DNA-PKcs activity which was kept at a same low activity level between 5 and 30 min. This means DNA-PKcs is not critical for DNA DSB repair in heat.

The activity of DNA-PKcs depends upon the presence of double-stranded DNA ends, and is based on the similarity of their DNA-binding properties, and Ku was identified as the DNA-targeting component of this protein complex[45-51]. This can be used to explain the fact that DNA-PKcs activity increased by about 30% at the 2nd hour after 40 Gy X-ray irradiation, which produced plenty of DNA DSB. After hyperthermia at 45.5 °C for 15 min, DNA-PKcs activity was stable at a low level (30%) up to 24 h. We are eager to know whether the low level DNA-PKcs affects the clonogenic survival. The results showed that the effects of thermal radiosensitization were lowered, even though DNA-PKcs activity did not restore. This indicated that there was no correlation between thermal inactivation of DNA-PKcs and radiosensitization by heat.

Wortmannin is a fungal metabolite originally characterized as an irreversible inhibitor of PI3K-like family including DNA-PKcs[52]. The inhibition of DNA-PKcs by Wortmannin could increase the slow rejoining component, resulting in deficiency of DNA DSB repair. The kinetics of DNA DSB rejoining in hyperthermia groups different from that treated with wortmannin, inhibited the DNA-PKcs activity. This confirms that DNA DSB repair is not completely affected by DNA-PKcs, other factors might also involve in the repair.

DNA-PKcs is not critical for radiosensitization by heat. What might explain the synergistic interaction between heat and radiation? One possibility is that homologous recombination may impair after heat shock, but the contribution of this repair pathway in mammalian cells seems limited[53]. Another possibility is that heat-induced loss of activity of DNA repair enzymes other than DNA-PKcs has been observed and proposed previously as the mechanism that underlies DNA repair inhibition and radiosensitization. These enzymes include DNA polymerases[37], ATM system[54], ATR system[38], etc. Motsumoto found recently that heating up to 90 min affected only marginally DNA-PKcs activity in four different human cell lines (results not published). The contradictory results are due to the methods of measurement, which can not distinguish between inhibition of ATM and DNA-PKcs as the substrate, and peptide is good for both kinases.

In clonogenic assay, the difference in radiosensitivity between radiation and thermal radiation groups manifested as α difference in the a components. The dose range over which the linear component dominates in a linear-quadratic (LQ) survival relationship depends on the relative values of α and β: the higher the relative value of α, the more linear response at low doses and the less sensitive it is to dose fraction[55]. In hyperthermia group, the α/β ratio is high, with no detectable influence of the quadratic function over the first two decades of reduction in cell survival, implying that accumulation of sublethal injury plays a negligible role in cell killing by thermal radiosensitization clinically[56]. From these results, we can deduce that heat inhibits the repair of radiation-induced single-strand breaks and radiation-induced chromosome aberrations. This inability to repair molecular damage translates into the inability to repair both sublethal damage and potentially lethal damage produced by radiation.

In conclusion, when the DNA-PKcs activity was determinated using the cell extracts and the peptide phosphorylation assay, DNA-PKcs activity was inactivated by heat treatment at 45.5 °C, and could not restore. Cell survival is not associated with the DNA-PKcs inactivity after heat. DNA-PKcs is not a unique factor affecting DNA DSB repair. This suggests DNA-PKcs does not play a crucial role in the enhancement of cellular radiosensitivity by hyperthermia.

Footnotes

Edited by Ma JY

References

- 1.Niu Q, Tang ZY, Ma ZC, Qin LX, Zhang LH. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential biomarker of metastatic recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:565–568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan J, Wu ZQ, Tang ZY, Zhou J, Qiu SJ, Ma ZC, Zhou XD, Ye SL. Multimodality treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with tumor thrombi in portal vein. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:28–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe C, Pilz T, Klostermann C, Berna M, Schild HH, Sauerbruch T, Caselmann WH. Clinical characteristics and outcome of a cohort of 101 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:208–215. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu MC, Shen F. Progress in research of liver surgery in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:773–776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yip D, Findlay M, Boyer M, Tattersall MH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in central Sydney: a 10-year review of patients seen in a medical oncology department. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:483–487. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i6.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu MD, Chen JW, Xie XY, Liang LJ, Huang JF. Portal vein embolization by fine needle ethanol injection: experimental and clinical studies. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:506–510. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i6.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang YF, Yang ZH, Hu JQ. Recurrence or metastasis of HCC: predictors, early detection and experimental antiangiogenic therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:61–65. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu ZQ, Fan J, Qiu SJ, Zhou J, Tang ZY. The value of postoperative hepatic regional chemotherapy in prevention of recurrence after radical resection of primary liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:131–133. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sithinamsuwan P, Piratvisuth T, Tanomkiat W, Apakupakul N, Tongyoo S. Review of 336 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma at Songklanagarind Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:339–343. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang ZY, Sun FX, Tian J, Ye SL, Liu YK, Liu KD, Xue Q, Chen J, Xia JL, Qin LX, et al. Metastatic human hepatocellular carcinoma models in nude mice and cell line with metastatic potential. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:597–601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bramhall SR, Minford E, Gunson B, Buckels JA. Liver transplantation in the UK. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:602–611. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Tang ZY, Ye SL, Liu YK, Chen J, Xue Q, Chen J, Gao DM, Bao WH. Establishment of cell clones with different metastatic potential from the metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line MHCC97. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:630–636. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma--cause, treatment and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:445–454. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JH, Lin G, Yan ZP, Wang XL, Cheng JM, Li MQ. Stage II surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma after TAE: a report of 38 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:133–136. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Wu PH, Li JQ, Zhang WZ, Lin HG, Zhang YQ. Segmental transcatheter arterial embolization for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:511–512. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i6.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng N, Ye SL, Sun RX, Zhao Y, Tang ZY. Effects of cryopreservation and phenylacetate on biological characters of adherent LAK cells from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:233–236. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin LX, Tang ZY, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, Zhou XD, Ye QH, Ji Y, Huang LW, Jia HL, Sun HC, et al. P53 immunohistochemical scoring: an independent prognostic marker for patients after hepatocellular carcinoma resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:459–463. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin LX, Tang ZY. The prognostic molecular markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:385–392. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang G, Long M, Wu ZZ, Yu WQ. Mechanical properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:243–246. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao WH, Ma ZM, Zhou XR, Feng YZ, Fang BS. Prediction of recurrence and prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection by use of CLIP score. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:237–242. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Wu ZQ, Ma ZC, Fan J, Qin LX, Zhou J, Wang JH, Wang BL, Zhong CS. Phase I clinical trial of oral furtulon and combined hepatic arterial chemoembolization and radiotherapy in unresectable primary liver cancers, including clinicopathologic study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:449–454. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Liu KD, Lu JZ, Xie H, Yao Z. Improved long-term survival for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with a combination of surgery and intrahepatic arterial infusion of 131I-anti-HCC mAb. Phase I/II clinical trials. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1998;124:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s004320050166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Liu KD, Yu YQ, Yang BH, Cai XJ, Xie H, Cao SL. Observation of changes in peripheral T-lymphocyte subsets by flow cytometry in patients with liver cancer treated with radioimmunotherapy. Nucl Med Commun. 1995;16:378–385. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Wang Y, Zhou Q, Gui SY, Li X. The point mutation of p53 gene exon7 in hepatocellular carcinoma from Anhui Province, a non HCC prevalent area in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:480–482. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Liu KD, Lu JZ, Cai XJ, Xie H. Human anti- (murine Ig) antibody responses in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving intrahepatic arterial 131I-labeled Hepama-1 mAb. Preliminary results and discussion. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;39:332–336. doi: 10.1007/BF01519987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Xie H, Liu KD, Lu JZ, Chai XJ, Wang GF, Yao Z, Qian JM. Radioimmunotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using 131I-Hepama-1 mAb: preliminary results. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1993;119:257–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01212721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu LX, Jiang HC, Piao DX. Radiofrequence ablation of liver cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:393–399. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seong J, Keum KC, Han KH, Lee DY, Lee JT, Chon CY, Moon YM, Suh CO, Kim GE. Combined transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and local radiotherapy of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:393–397. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang ZY, Yu YQ, Zhou XD, Ma ZC, Yang BH, Lin ZY, Lu JZ, Liu KD, Fan Z, Zeng ZC. Treatment of unresectable primary liver cancer: with reference to cytoreduction and sequential resection. World J Surg. 1995;19:47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00316979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Nishimura Y, Masunaga S, Mitumori M, Okuno Y, Fujishiro M, Kanamori S, Horii N, Akuta K, et al. Clinical results of radiofrequency hyperthermia for malignant liver tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:359–365. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seong J, Lee HS, Han KH, Chon CY, Suh CO, Kim GE. Combined treatment of radiotherapy and hyperthermia for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:252–259. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1994.35.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sneed PK, Stauffer PR, McDermott MW, Diederich CJ, Lamborn KR, Prados MD, Chang S, Weaver KA, Spry L, Malec MK, et al. Survival benefit of hyperthermia in a prospective randomized trial of brachytherapy boost +/- hyperthermia for glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall EJ. Hyperthermia. In: Hall E, editor. J., editors. Radiobiology for the radiologist. Philadelphia: J B Lippincott; 1994. pp. 278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iliakis G, Seaner R. A DNA double-strand break repair-deficient mutant of CHO cells shows reduced radiosensitization after exposure to hyperthermic temperatures in the plateau phase of growth. Int J Hyperthermia. 1990;6:801–812. doi: 10.3109/02656739009140827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Awady RA, Dikomey E, Dahm-Daphi J. Heat effects on DNA repair after ionising radiation: hyperthermia commonly increases the number of non-repaired double-strand breaks and structural rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1960–1966. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kampinga HH, Dikomey E. Hyperthermic radiosensitization: mode of action and clinical relevance. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:399–408. doi: 10.1080/09553000010024687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raaphorst GP. Recovery of sublethal radiation damage and its inhibition by hyperthermia in normal and transformed mouse cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90804-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raaphorst GP, Feeley MM. Hyperthermia radiosensitization in human glioma cells comparison of recovery of polymerase activity, survival, and potentially lethal damage repair. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith GC, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:916–934. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto Y, Suzuki N, Sakai K, Morimatsu A, Hirano K, Murofushi H. A possible mechanism for hyperthermic radiosensitization mediated through hyperthermic lability of Ku subunits in DNA-dependent protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:568–572. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iliakis GE, Metzger L, Denko N, Stamato TD. Detection of DNA double-strand breaks in synchronous cultures of CHO cells by means of asymmetric field inversion gel electrophoresis. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991;59:321–341. doi: 10.1080/09553009114550311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzger L, Iliakis G. Kinetics of DNA double-strand break repair throughout the cell cycle as assayed by pulsed field gel electrophoresis in CHO cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991;59:1325–1339. doi: 10.1080/09553009114551201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ihara M, Suwa A, Komatsu K, Shimasaki T, Okaichi K, Hendrickson EA, Okumura Y. Heat sensitivity of double-stranded DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) activity. Int J Radiat Biol. 1999;75:253–258. doi: 10.1080/095530099140717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woudstra EC, Konings AW, Jeggo PA, Kampinga HH. Role of DNA-PK subunits in radiosensitization by hyperthermia. Radiat Res. 1999;152:214–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gottlieb TM, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase: requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell. 1993;72:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H, Zeng ZC, Bui TA, Sonoda E, Takata M, Takeda S, Iliakis G. Efficient rejoining of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks in vertebrate cells deficient in genes of the RAD52 epistasis group. Oncogene. 2001;20:2212–2224. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Zeng ZC, Perrault AR, Cheng X, Qin W, Iliakis G. Genetic evidence for the involvement of DNA ligase IV in the DNA-PK-dependent pathway of non-homologous end joining in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1653–1660. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.8.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu B, Zhou XY, Wang X, Zeng ZC, Iliakis G, Wang Y. The radioresistance to killing of A1-5 cells derives from activation of the Chk1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17693–17698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Zeng ZC, Bui TA, DiBiase SJ, Qin W, Xia F, Powell SN, Iliakis G. Nonhomologous end-joining of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-stranded breaks in human tumor cells deficient in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Cancer Res. 2001;61:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asaad NA, Zeng ZC, Guan J, Thacker J, Iliakis G. Homologous recombination as a potential target for caffeine radiosensitization in mammalian cells: reduced caffeine radiosensitization in XRCC2 and XRCC3 mutants. Oncogene. 2000;19:5788–5800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiBiase SJ, Zeng ZC, Chen R, Hyslop T, Curran WJ, Iliakis G. DNA-dependent protein kinase stimulates an independently active, nonhomologous, end-joining apparatus. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1245–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wymann MP, Bulgarelli-Leva G, Zvelebil MJ, Pirola L, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD, Panayotou G. Wortmannin inactivates phosphoinositide 3-kinase by covalent modification of Lys-802, a residue involved in the phosphate transfer reaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1722–1733. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roth DB, Wilson JH. Relative rates of homologous and nonhomologous recombination in transfected DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3355–3359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Recruitment of ATM protein to double strand DNA irradiated with ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25571–25575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Withers HR, McBride WH. Biologic basis of radiation therapy. In: Perez C, Brady L, editors. W. eds: Principles & Practice of Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven; 1998. p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall EJ. Hyperthermia. In: Hall E, editor. J., editors. Radiobiology for the radiologist. Philadelphia: J B Lippincott; 1994. pp. 271–272. [Google Scholar]