Abstract

AIM: Chronic liver diseases, such as fibrosis or cirrhosis, are more common in men than in women. This gender difference may be related to the effects of sex hormones on the liver. The aim of the present work was to investigate the effects of estrogen on CCL4-induced fibrosis of the liver in rats.

METHODS: Liver fibrosis was induced in male, female and ovariectomized rats by CCL4 administration. All the groups were treated with estradiol (1 mg/kg) twice weekly. And tamoxifen was given to male fibrosis model. At the end of 8 wk, all the rats were killed to study serum indicators and the livers.

RESULTS: Estradiol treatment reduced aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hyaluronic acid (HA) and type IV collagen (CIV) in sera, suppressed hepatic collagen content, decreased the areas of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) positive for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and lowered the synthesis of hepatic type I collagen significantly in both sexes and ovariectomy fibrotic rats induced by CCL4 administration. Whereas, tamoxifen had the opposite effect. The fibrotic response of the female liver to CCL4 treatment was significantly weaker than that of male liver.

CONCLUSION: Estradiol reduces CCL4-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. The antifibrogenic role of estrogen in the liver may be one reason for the sex associated differences in the progression from hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen is frequently used for anticonception and treatments of menopausal disorders. Its clinical use has increased steadily during the last years due to reports of decreased morbidity and mortality during postmenopausal estrogen treatment[1]. There have been reports of decreased morbidity in cardiovascular disease, suggesting estrogenic effects on tissues other than on the classic reproductive organs.

Population data have long suggested that chronic liver disease progresses at unequal rates in both sexes for viral hepatitis and other forms of injury with a similar incidence in males and females. In chronic viral hepatitis the major sequelae, such as fibrosis or cirrhosis, are more common in men than in women[2,3]. Although establishing the actual rate of fibrosis in a patient would require serial liver biopsy, which is seldom done, a reasonable approximation can be inferred from the incidence of fibrosis-related complications[4-6]. The development of cirrhosis is more common in men than in women (2.3 to 2.6:1). Although the liver is not a classic sex hormone target, livers in both men and women have been shown to contain estrogen receptors and respond to estrogens by regulating liver function. Therefore, sex hormones may play a role in the progression from hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis. It showed that estradiol treatment resulted in reducing hepatic fibrosis in rats induced by dimethylnitrosamine (DMN). However, much current evidence suggests that women develop alcoholic liver disease at lower levels of alcohol intake and over a shorter period of time as compared to men. In other words, females are more susceptible to alcohol-induced liver injury than males[7]. The specific mechanisms concerning a gender-related difference in susceptibility are largely unknown.

CCL4-induced fibrosis shares several characteristics with human fibrosis of different etiologies; thus, it is an adequate model of human fibrosis[8-10]. The aim of the present work was to study the effects of estrogen on CCL4-induced fibrosis of the liver in rats, and to investigate the possible mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and female Spratgue-Dawley rats (Experimental Animal Holding Unit of Shaanxi Province, China) were housed in a temperature-humidity-controlled environment with 12-h light-dark cycles (lights on from 07:00 to 19:00) and had unrestricted access to food and water. Forty male rats, weighing 220 ± 21 g, corresponding to an age of approximately 10 wk, were divided into four groups of ten each. For CCL4 group, 400 mL/L CCL4 in peanut oil were injected subcutaneously at a dose of 2 mL/kg twice weekly, and the first dosage was doubled. The estrogen group, apart from the used of CCL4, was treated subcutaneausly with estradiol 1 mg/kg twice weekly (The Ninth Pharmaceutical Plant of Shanghai, China). The anti-estrogen group, along with the CCL4 treatment described above, was given Tamoxifen 6 mg/kg every day orally (The First Pharmaceutical Plant of Suzhou, China). The rats were fed a modified high fat diet containing 5 g/kg cholesteral and 200 g/kg pig oil. The control group was given normal food and water, and received injection of peanut oil vehicle twice weekly.

Fifty female rats 10 wk old, weighing 208 ± 17 g, were divided into five groups with ten each. The ovariectomy (Ovx) group was initiated with a bilateral ovariectomy and the sham operation group was initiated with just a sham operation. The two estrogen groups, with bilateral ovariectomy and with sham operation, were treated subcutaneously with estradiol (1 mg/kg twice weekly). All of the above four groups received 400 mL/L of CCL4 in peanut oil at a dose of 2 mL/kg twice weekly, and were fed with a high fat diet containing 5 g/kg cholesteral and 200 g/kg pig oil. The CCL4 and estradiol were used after 2 wk of operation. The control group was given normal food and water, and received injection of peanut oil vehicle twice weekly.

At the end of the 8-week experimental period, all the rats were fasted overnight and put to death by cervical dislocation after anaesthetised by intramuscular injection of sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg). Blood was collected from the animals and the serum obtained was analysed. The liver was removed rapidly.

Estimation of serum indicators

In serum, activities of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were assayed by a 917-Hitachi Automatic Analyzer. Serum hyaluronic acid (HA) and type IV collagen (CIV) concentrations were measured radioimmunologically using commercial kit (Shanghai Navy Medical Institute, China).

Parameters of hepatic antioxidation

Parameters of antioxidation in the liver was determined by measuring the levels of hepatic malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (kit: Jiancheng Medical Institute, Nanjing, China).

Histopathological study

Excised liver tissues from each rat were fixed in 100 mL/L neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and masson's trichrome. The evaluation of hepatic fibrosis was determined by a semi-quantitative method to assess the degree of histologic injury in chronic hepatic fibrosis[11,12].

Immunohistochemical examination

Liver tissue sections were mounted on slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in alcohol. The level of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Neomarkers, USA), type I collagens (Boster, Wuhan, China), transforming growth factor β1(TGFβ1) and platelet -derived growth factor (PDGF) (Dako, USA) were determined by immunohistochemical methods in female groups. Based on the extent of histological staging, the α-SMA, type I collagens, TGFβ1 and PDGF positive cells were expressed as a percentage of the total area of the specimen.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as ¯x ± s unless otherwise indicated. The Mann-Whitney u test for nonparametric and unpaired values, student's t-test or Fisher's exact test was used as appropriate. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Changes of serum indicators and hepatic antioxidation date

At the end of 8-week experimental period, 8 rats were dead because of infection at the region of injection and hepatic crack by unsuitable handling. Table 1 gives the values for the activities of the serum indicator enzymes, the markers of hepatic fibrosis, and the hepatic antioxidation data.

Table 1.

Liver enzymes, serum fibrosis indicators and hepatic antioxidation (¯x ± s)

| Group | n | ALT (nkat/L) | AST (nkat/L) | HA (μg/L) | CIV (μg/L) | MDA (nmol/g) | SOD (kNU/g) |

| Males | |||||||

| Control | 10 | 31 ± 6 | 66 ± 18 | 115 ± 31 | 18 ± 5 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 1.6 |

| CCL4 | 10 | 576 ± 262a | 699 ± 241a | 530 ± 122a | 54 ± 14a | 10.5 ± 3.4a | 2.2 ± 1.1a |

| CCL4 + E | 8 | 355 ± 125c | 314 ± 179c | 232 ± 78c | 30 ± 10c | 6.6 ± 2.8c | 5.0 ± 1.6c |

| CCL4 + Tam | 8 | 884 ± 294c | 1073 ± 453c | 703 ± 187c | 69 ± 5c | ||

| Females | |||||||

| Control | 10 | 35.8 ± 7.9 | 64.5 ± 20.8 | 121 ± 26 | 17 ± 4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 8.7 ± 2.8 |

| CCL4 | 9 | 540 ± 252a | 631 ± 268a | 388 ± 81a | 41 ± 11a | 7.1 ± 2.1a | 4.0 ± 1.5a |

| CCL4 + Ovx | 10 | 658 ± 220 | 697 ± 240 | 586 ± 145c | 53 ± 14c | 9.1 ± 2.9c | 2.8 ± 1.0c |

| CCL4 + E | 8 | 314 ± 163c | 302 ± 153c | 267 ± 83c | 29 ± 7c | 4.7 ± 2.2c | 5.9 ± 2.0c |

| CCL4 + Ovx + E | 9 | 311 ± 146c | 321 ± 121c | 236 ± 119c | 31 ± 7c | 4.8 ± 2.3c | 6.2 ± 2.5c |

P < 0.05, vs control;

P < 0.05, vs CCL4

It is evident that CCL4 produced a marked increase in the activities of serum ALT and AST in both male and female rats. Although the extent of that was lower in female group than in male group, it was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The CCL4 plus estradiol group showed a significant decrease in the enzyme levels, but the levels were still higher than those of control groups. In ovariectomy rats, when CCL4 were given, the enzyme levels were higher than those of the sham operation rats in both estradiol used or none-used groups, but the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The levels of serum ALT and AST in Tamoxifen group were significantly higher than those of the CCL4 group and estrogen used groups.

As for the changing trend of fibrotic markers in serums, HA and CIV were similar with those of the enzyme levels in all groups. The results showed that the levels of HA and CIV in CCL4 used groups were significantly higher than those of control groups, especially in male group. Tamoxifen could increase the extent of that and estrogen could decrease it significantly. In ovariectomy groups, the HA and CIV were significantly higher than those of shame operation groups.

Tissue antioxidation date indicated that MDA was increased and SOD was decreased in CCL4 treated rats significantly, whereas estradiol had the opposite effect. The MDA was higher and SOD was lower in males than those of females treated with CCL4.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical changes

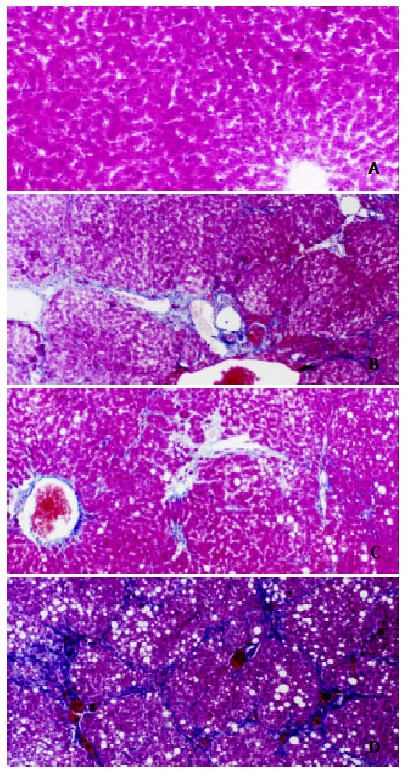

The control livers showed normal lobular architecture with central veins and radiating hepatic cords (Figure 1A). Prolonged administration of CCL4 causes severe pathological damages: inflammation, necrosis, and collagen deposition (Figure 1B, male). The semiquantitative hepatic collagen staging value was 3.3 ± 0.7 in males, and 2.4 ± 1.1 in females. It was showed that the staging value was significantly decreased in female rats. After administration of estradiol, the extent of hepatic fibrosis was significantly weaker than that of CCL4 groups (Figure 1C:male): the semiquantitative staging value was 2.0 ± 1.1 in males and 1.6 ± 0.9 in females respectively. Ovariectomy significantly increased the staging value (3.1 ± 0.7). Moreover, the staging value was highest when given Tamoxifen to the experimented rats (3.7 ± 0.5 Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Effects of estradiol and tamoxifen on the histology of CCL4 induced fibrotic rat liver. Masson trichome stain, scale bar = 40 μm, original magnification, × 100. 1A: Normal rat liver; 1B: CCL4 group shows fibrosis; 1C: Estrogen group with less fibrosis than in group B; 1D: Tamoxifen group shows marked fibrosis than in group B.

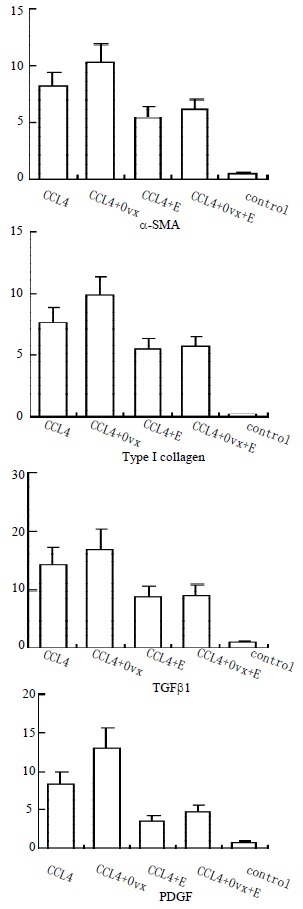

Analysis of α-SMA, an activation marker of rat hepatic stellate cells (HSC) by immunohistochemistry showed staining in vascular smooth muscle cell of control rat livers, but not in sinusoids. In the CCL4 model, the positive cells of α-SMA, type I collagen, TGFβ1 and PDGF within centrilobular and periportal fibrotic bands. The percentage areas of these staining in the liver of female rats were showed in Figure 2. The results suggest that administration of CCL4 significantly increased the percentage areas of all of the four marker staining. Ovariectomy group has a marked higher percentage area than that of CCL4 group and it could be significantly suppresed by estradiol used.

Figure 2.

Percentage area (%) of α-SMA, type I collagen, TGFβ1, and PDGF in female rats

DISCUSSION

Hepatic fibrosis is usually initiated by hepatocyte damage, leading to recruitment of inflammatory cells and platelets, activation of kupffer cells and subsequent release of cytokines and growth factors (e.g. TGFβ1 and PDGF)[13,14]. These factors probably link the inflammatory and reparative phase of liver cirrhosis, by activating HSC[15-18]. Upon activation, HSC proliferate and transform into myofibroblast-like cells that deposit large amounts of connective tissue components[19-27].

The present study showed that estradiol reduces CCL4-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Estradiol administration reduces HA and CIV in serums, suppresses hepatic collagen content, reduces the areas of HSC positive for α-SMA, and lowers the synthesis of hepatic type I collagen in both sexes. The fibrotic response of the female liver to CCL4 treatment was significantly weaker than that of male liver. It suggested that physiological levels of estrogen have an antifibrogenic effect. These effects of estrogen were also confirmed by ovariectomy in female rats at the time of CCL4 administration. These findings suggest that the antifibrogenic role of estrogen in the liver may be one reason for the sex associated differences in the progression from hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis.

Hepatic fibrogenesis is often associated with hepatocellular necrosis and inflammation accompanied by the repair processes[28-29]. Chronic administration of CCL4 caused fibrosis as indicated by an increase in serum marker enzymes. Raised serum enzyme levels in CCL4-injected rats can be attributed to the damaged hepatocellulal structural integrity[30-32]. The administration of estradiol in this study seems to decrease the serum enzymes (ALT, AST), and then preserve the structural integrity of the hepatocellular membrane. Decreased hepatocyte damage suppressing the stimulant effect to the Kupffer cells and subsequent by lower the HSC activation[33].

Peroxidation of lipids can dramatically change the properties of biological membranes, resulting in severe cell damage and could play a significant role in the pathogenesis of disease. It has showed that lipid peroxidation, free-radical-mediated process, and certain lipid peroxidation products induce genetic overexpression of fibrogenic cytokines and increase the synthesis of collagen. Free radicals and MDA can stimulate the synthesis of collagen and initiate the activation of HSC[34,35]. Relevant to the latter findings, estradiol and its derivatives are strong endogenous anti-oxidants that reduce lipid peroxide levels in liver and serum. Free radicals, generated mainly by Kupffer cells, are thought to cause tissue injury by initiating lipid peroxidation and irreversibly modifying membrane structure. The present study shows that CCL4 administration leads to parallel increase in MDA and collagen, and subsequent decrease in SOD, a radical scavenging agent, and that estradiol had the opposite effect. These findings suggest that the antifibrotic effect of estradiol may be caused, at least in part, by its radical scavenging action or antioxidant activity.

Cell proliferation, α-SMA expression, retinoid disappearance, and the formation of collagens and other ECM materials are characteristics of the activated phenotype of HSC[36]. So HSC are regarded as the primary target cells of hepatic fibrogenesis. Studies in vitro have shown that HSC and their activated counterparts may be induced to proliferate by polypeptide growth factors and cytokines, such as TGFβ1 and PDGF[37,38]. As these growth factors are produced by infiltrating inflammatory cells, Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells, they might act as paracrine mediators which trigger the transformation of HSC in vivo. The present data show that estradiol suppresses HSC proliferation and parallel with inhibit TGFβ1 and PDGF expression in CCL4-induced fibrosis in male and female rats. These findings suggest that estrogen may exert its suppressive effect on hepatic fibrosis by indirectly modulating the synthesis and releasing of cytokines and other growth factors which in turn altering HSC activation and proliferation.

Chronic fibrotic diseases can differ from each other in etiology. But, in terms of pathogenesis, they share some basic common features[1]. For instance, three serious chronic disease-atherosclerosis, glomerulosclerosis, and liver fibrosis-may appear very different in their development. In all three, though, a central, and indeed an essential, role is playd by macrophages and by ECM-producing cells: smooth muscle cells (SMC) in atherosclerosis, mesangial cell in glomerulosclerosis, and HSC in liver fibrosis. The three types of cells have many properties in common both structurally and functionally, including a changes in cell biology with deposition of matrix proteins. Therefore, factors which affect the development of atherosclerosis or glomerulosclerosis may affect liver fibrossis by similar mechanisms. Studies show that estradiol suppresses atherosclerosis and glomerulosclerosis in rats by directly affecting the estrogen receptor on SMC and mesangial cell. Livers in both male and Female rats have shown to contain high affinity, low capacity estrogen receptors and respond to estrogen by regulating liver function. In the present study, Tamoxifen, an antiestrogen act by occupying the estrogen-binding site of the receptor protein, increases fibrogenesis in CCL4-induced fibrosis of the liver. It suggests that estradiol may suppress hepatic fibrosis also by a direct receptor mechanism. This remains to be confirmed.

In conclusion, estrogen may play an important role as an endogenous fibrosuppressant, accounting for sex-associated differences in the progression from hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis. The following mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain the antifibrogenic effect of estrogens: (A) a hepatocellular membrane protection and radical scavenging action. (B) a modulation of HSC proliferation and collagen synthesis, (C) a modulation in the expression of pro-and anti-fibrogenic cytokines and may be (D) a estrogen receptor mechanism. However, the real importance of these mechanisms is still to be elucidated.

Footnotes

Edited by Zhao M

Supported by the Doctorate Foundation of Xi'an Jiaotong University, No.2001-13.

References

- 1.Tan E, Gurjar MV, Sharma RV, Bhalla RC. Estrogen receptor-alpha gene transfer into bovine aortic endothelial cells induces eNOS gene expression and inhibits cell migration. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:788–797. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinzani M, Romanelli RG, Magli S. Progression of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases: time to tally the score. J Hepatol. 2001;34:764–767. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan JC, MA JY, Pan BR, MA LS. Study of hepatitis B in China. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:611–616. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji XL. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:95–97. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie QH, Cheng YQ, Xie YM, Zhou YX, Cao YZ. Inhibiting effect of antisense oligonucleotides phosphorthioate on gene expression of TIMP-1 in rat liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:363–369. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai WJ, Jiang HC. Advances in gene therapy of liver cirrhosis: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:1–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Järveläinen HA, Lukkari TA, Heinaro S, Sippel H, Lindros KO. The antiestrogen toremifene protects against alcoholic liver injury in female rats. J Hepatol. 2001;35:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du WD, Zhang YE, Zhai WR, Zhou XM. Dynamic changes of type I, III and IV collagen synthesis and distribution of collagen-producing cells in carbon tetrachloride-induced rat liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:397–403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i5.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu CH. Fibrodynamics-elucidation of the mechanisms and sites of liver fibrogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:388–390. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu HL, Li XH, Wang DY, Yang SP. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 expression in fibrotic rat liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:881–884. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George J, Rao KR, Stern R, Chandrakasan G. Dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in rats: the early deposition of collagen. Toxicology. 2001;156:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilette C, Rousselet MC, Bedossa P, Chappard D, Oberti F, Rifflet H, Maïga MY, Gallois Y, Calès P. Histopathological evaluation of liver fibrosis: quantitative image analysis vs semi-quantitative scores. Comparison with serum markers. J Hepatol. 1998;28:439–446. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao ZL, Li DG, Lu HM, Gu XH. The effect of retinoic acid on Ito cell proliferation and content of DNA and RNA. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:443–444. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruck R, Shirin H, Aeed H, Matas Z, Hochman A, Pines M, Avni Y. Prevention of hepatic cirrhosis in rats by hydroxyl radical scavengers. J Hepatol. 2001;35:457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer M, Schuppan D. TGFbeta1 in liver fibrosis: time to change paradigms? FEBS Lett. 2001;502:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei HS, Li DG, Lu HM, Zhan YT, Wang ZR, Huang X, Zhang J, Cheng JL, Xu QF. Effects of AT1 receptor antagonist, losartan, on rat hepatic fibrosis induced by CCl (4) World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:540–545. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i4.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang X, Li DG, Wang ZR, Wei HS, Cheng JL, Zhan YT, Zhou X, Xu QF, Li X, Lu HM. Expression changes of activin A in the development of hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:37–41. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Meng Y, Yang XS, Wu PS, Li SM, Lai WY. CYP11B2 expression in HSCs and its effect on hepatic fibrogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:885–887. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang GC, Zhang JS, Zhang YE. Effects of retinoic acid on proliferation, phenotype and expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in TGF-beta1-stimulated rat hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:819–823. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei HS, Lu HM, Li DG, Zhan YT, Wang ZR, Huang X, Cheng JL, Xu QF. The regulatory role of AT 1 receptor on activated HSCs in hepatic fibrogenesis: effects of RAS inhibitors on hepatic fibrosis induced by CCl (4) World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:824–828. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen PS, Zhai WR, Zhou XM, Zhang JS, Zhang YE, Ling YQ, Gu YH. Effects of hypoxia, hyperoxia on the regulation of expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:647–651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JY, Zhang QS, Guo JS, Hu MY. Effects of glycyrrhetinic acid on collagen metabolism of hepatic stellate cells at different stages of liver fibrosis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:115–119. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie YM, Nie QH, Chou YX, Cheng YQ, Kang WZ. Detection of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 RNA expressions in cirrhotic liver tissue using digoxigenin labelled probe by in situ hybridization. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X, Liu CH, Xu GF, Chen WH, Liu P. Successive observation of laminin and collagen IV on hepatic sinusoid during the formation of the liver fibrosis in rats. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:260–262. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao XX, Tang YW, Yao DM, Xiu HM. Effect of Yigan Decoction on the expression of type I, III collagen proteins in experimental hepatic fibrosis in rats. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:263–267. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang GC, Zhang JS. Intercellular signal transduction of activated hepatic stellate cells. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:1056–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T, Hu JH, Cai Q, Ji YP. Signal conducting molecule in hepatic stellate cells. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:805–807. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei DX, Peng CH, Peng SY, Jiang XC, Wu YL, Shen HW. Safe upper limit of intermittent hepatic inflow occlusion for liver resection in cirrhotic rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:713–717. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li D, Zhang LJ, Chen ZX, Huang YH, Whang XZ. Effects of TNFα IL-6 and IL-10 on the development of experimental rat liver fibrosis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:1242–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang LT, Zhang B, Chen JJ. Effect of anti-fibrosis compound on collagen expression of hepatic cells in experimental liver fibrosis of rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:877–880. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i6.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang YT, Chang XM, Li X, LiHL Effects of spironolactone on expression of type I/III collagen proteins in rat hepatic fibrosis. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:1120–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Q, Yan YC, Gao YX. Inhibitory effect of Quxianruangan capsulae on liver fibrosis in rats and chronic hepatitis atients. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:1246–1249. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao XX, Tang YW, Yao DM, Xiu HM. Effects of Yigan Decoction on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:511–514. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parola M, Robino G. Oxidative stress-related molecules and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen WH, Liu P, Xu GF, Lu X, Xiong WG, Li FH, Liu CH. Role of lipid peroxidation in liver fibrogenesis induced by dimethylnitrosamine in rats. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2001;9:645–648. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyoshi H, Terada T. Centrilobular and perisinusoidal fibrosis in experimental congestive liver in the rat. J Hepatol. 1999;30:433–439. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gandhi CR, Kuddus RH, Uemura T, Rao AS. Endothelin stimulates transforming growth factor-beta1 and collagen synthesis in stellate cells from control but not cirrhotic rat liver. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;406:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00683-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel A, Kuddus RH, Rao AS, Gandhi CR. Down-regulation of endothelin receptors by transforming growth factor beta1 in hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 1999;30:440–450. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]