Abstract

AIM: To seek the X associated protein (XAP) with the constructed bait vector pAS2-1X from normal human liver cDNA library.

METHODS: The X region of the HBV gene was amplied by PCR and cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pAS2-1.The reconstituted plasmid pAS2-1X was transformed into the yeast cells and the expression of X protein (pX) was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Yeast cells were cotransformed with pAS2-1X and the normal human liver cDNA library and were grown in selective SC/-trp-leu-his-ade medium, the second screen was performed with the LacZ report gene. Furthermore, segregation analysis and mating experiment were performed to eliminate the false positive and the true positive clones were selected for PCR and sequencing.

RESULTS: Reconstituted plasmid pAS2-1X including the anticipated fragment of X gene was proved by auto-sequencing assay. Western blot analysis showed that reconstituted plasmid pAS2-1X expressed BD:X fusion protein in yeast cells. Of 5 × 106 transformed colonies screened, 65 grew in the selective SC/-trp-leu-his-ade medium, 5 scored positive for β-gal activity, and only 2 remaining clones passed through the segregation analysis and mating experiment. Sequence analysis identified that two clones contained similar cDNA fragment: GAACTTGCG.

CONCLUSION: The short peptide (glutacid-leucine-alanine)is a possible required site for XAP binding to pX. Normal human liver cDNA library has difficulties in expressing the integrated XAP on yeast cells.

INTRODUCTION

Modern biological investigations indicate many proteins have relationship with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma[1-8]. More and more evidences have demonstrated hepatitis B virus (HBV) X protein which encoded by the smallest open reading frame (ORF) of the HBV genome plays an important role in the carcinogenesis[9-13]. At a molecular level, several endogenous genes critical for cell proliferation or apoptosis and the inflammatory response seemed interacted with HBx, such as c-Fos, c-Jun, CREB, CD44,TNF-α, p21 and p53[14-21]. In addition, DNA transfection approaches have clearly demonstrated that pX is a transactivator of a wide variety of viral and cellar promoters[22-24],but the underlying mechanism of transactivation is currently obsure. Since HBx has no ability to bind DNA, protein- protein interaction seems to be crucial for HBx transactivation[25-28]. One most direct way to identify the mechanism of HBx transactivation is to find out host proteins that interact specifically with HBx. We use the yeast two -hybrid system, a genetic approach to search the clone genes that interact with a protein of interest by in vivo complementation in yeast cells, to seek XAP from normal human liver cDNA library.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

To make the bait plasmid, the X region of the HBV gene was amplified by PCR using as forward and reverse primers XF and XR, which contain an EcoRI and Pst I site respectively for ease of cloning.The sequence of the primers, with the restriction enzyme site underlined are: XF: ACGGAATTCATGGCTGCTAGGCTGTG, XR: ATCCTGCAGAGGTGAAAAAGTTGCAT. These bind to nucletide positions 1374 and 1838 on HBV genome. The templates for this reaction were sera of HBV DNA posistive patients. The 464 bp product was cloned into the respective restriction enzyme sites of plasmid pAS2-1 (Clontech) and this plamid was subsequently named pAS2-1X.

Westem Blot analysis

Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109(Clontech) was grown in YPD medium(10 g·L-1 yeast extract, 20 g·L-1 peptone, 20 g·L-1dextrose). This yeast strain carries LacZ. HIS3 and ADE2 reporter genes under the control of Gal4-binding sites was used to screen the liver cDNA library. Yeast cells were transformed with pAS2-1X using lithium acetate method previsously published by Gietz et al[29] and were grown in selective SC/-trp medium. Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysates were prepared according to Urea/SDS method. A part of protein exact were resolved on a 120 g·L-1 SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluride membrane. After blocking with nonfat dried milk, the membrane was treated with 1:3000 diluted Gal4 DNA-BD monoclonal antibody(Clontech) followed by 1:1000 dilured alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Subsequently the blot was developed by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium. The untransformed yeast cells were used for negative control.

Screening of the liver cell cDNA library by the yeast two-hybrid system

The screening procedure used was a modification of the method described by Gietz et al[29]. Yeast cells AH109 were transformed with pAS2-1X and pACT2-cDNA library (Clotech) by Liac-mediated transformation and were grown in selective SC/-trp-leu-his-ade medium for 7 days. After about 3 days at 30 °C, the growing colonies were assayed for α-gal activity by replica plating the yeast transformants onto Whatman filter papers, the filters were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for 10 s twice and incubated for 1-8 h at 30°C in a buffer containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-D-galactopyranoside(X-gal) solution. Positive interactions were detected by the appearance of blue colonies. Segregation analysis and mating experiment were done to exclude the type I ,II, III false positive and true positive colonies were obtained.

Sequence analysis of pACT2-cDNA

The pACT2-cDNA plasmid genome was isolated following the standard protocol. Briefly, the true positive clones were grown in SC/-leu medium, cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 g·L-1 Triton 100, 10 g·L-1SDS, 10 mmol L-1 NaCl, 10 mmol·L-1 Tris-HCl pH8.0, 1 mmol·L-1 Na2EDTA) and phenol, chloroform and isoamyl alcohol(volume fraction 25:24:1). After addition of acid-washed glass beads (Sigma), samples were centrifugated and plamid DNA recovered. The pACT2-cDNA plasmid DNA was purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation to permit PCR using the Matchmaker AD LD-Insert Screening Amplimers (Clotech) which anneals to GAL4-AD. Auto-sequencing assay was performed in Shanghai Shenggong Biological Corporation.

RESULTS

Plasmid construction

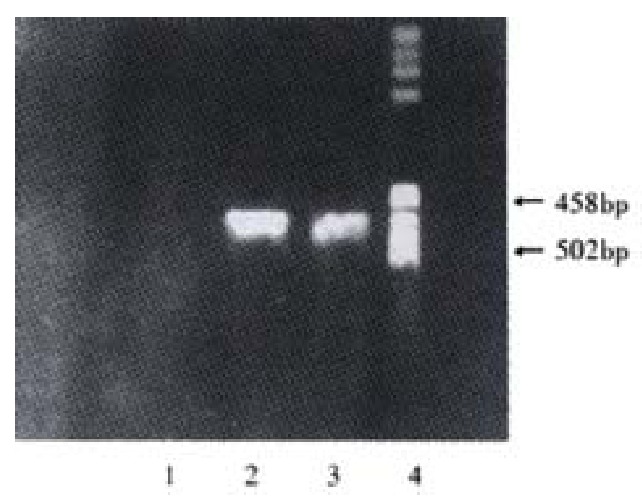

The HBV X fragment was successfulily generated by PCR(Figure 1) and cloned into plamsid pAS2-1. Reconstituted plasmid pAS2-1X including the anticipated fragment of X gene was proved by digesting with resticted endonuclease and auto-sequencing assay as follows: GACTGTATCGCCGGTATTGCAATA CCCAGCTTTGACTCATATGGCCAT GGAGGCCGAATTCATGGCTGCTAG GCTGTGCTGCCAACTGGATCCTGC GCGGGACGTCCTTTGTTTACGTCC CGTCAGCGCTGAATCCCGCGGACG ACCCCTCCCGGGGCCGCTTGGGGC TCTACCGCCCGCTTCTCCGCCTGT TGTACCGACCGACCACGGGGCGCA CCTCTCTTTACGCGGACTCCCCGT CTGTGCCTTCTCATCTGCCGGACC GTGTGCACTTCGCTTCACCTCTGC ACGTCGCATGGAAACCACCGTGAA CGCCCACCGGAACCTGCCCAAGGC CTTGCATAAGAGGACTCTTGGACT TGCAGCAATGTCAACGACCGACCT TGAGGCATACTTCAAAGACTGTGT GTTTAACGAGTGGGAGGAGTTGGG GGAGGAGATTAGGTTAAAGGTCTT TGTACTAGGAGGCTGTAGGCATAA ATTGGTGTGTTCACCAGCACCATG CAACTTTTTCACCTCTGCAGCCAA GCTAATTCCGGGCGAATTTCTTAT GATTTATGATTTTTATTATTAAAT AAGTTATAAAAAAAATAAGTGTAT ACAAATTTTAAAGGTGACTTTTAN GTTTTAAAACGAAAATTNTTATTN TTGAGTAACTNTTTCCTGGAGGTC AAGGTTGCTT (underlined fractions are restriction enzyme site).

Figure 1.

Electrophoresis of X gene PCR products. 1: Negative control; 2:Positive control; 3:Sample; 4: Marker

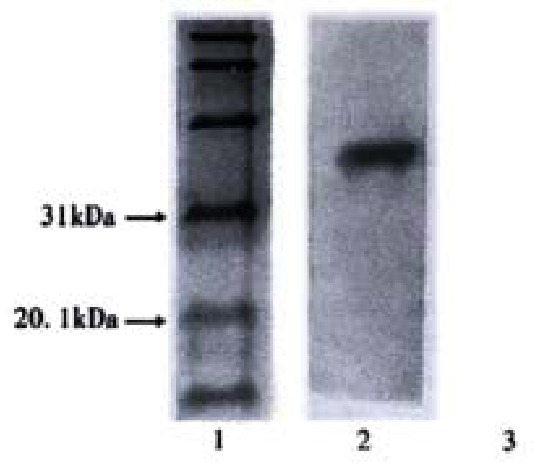

Westem Blot analysis

Westem Blot Analysis proved that yeast cells transformed with pAS2-1X have positive signal which can not be seen in the control, pAS2-1X can express BD:X fusion protein yeast cells(Figure 2). Besides, The colony-lift assay showed that the reconstruted plasmid could not active LacZ reporter gene in yeast. pAS2-1X can be used as bait vector in yeast two-hybrid system.

Figure 2.

Western blot of yeast after being transformed with pAS2-1X. 1:Marker; 2: pX; 3: Negative control

Screening of the liver cell cDNA library

Of 5 × 10 6 transformed colonies screened, 65 grew in the selective SC/-trp-leu-his-ade medium. Out of these HIS + ADE + prototrophs, 5 scored positive for β-gal activity, only 2 remaining clones passed through the segregation analysis and mating experiment.

Sequence analysis

PCR (Figure 3) and sequence analysis identified that two clones contained the same cDNA sequence: GAACTTGCG, which encodes glutacid-leucine -alanine.

Figure 3.

Library cDNA amplified from positive yeast clones. 1:100 bp DNA ladder; 2. 3: positive cloned

DISSCUSION

Persistent Hepatitis B virus infection is strongly associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC). The viral X gene encodes a 17-kd protein, termed pX, fuctions a transcriptional activator of a variety of viral and cellular genes, it is capable of interacting with a wide variety of cellular protein, including cell-cycle control and apoptosis protein. There are well documented that pX acts through apoptosis pathway involving Fas and caspase 3[30-33], it also interacts with p53, a wellknow tumor suppressor gene[34-36] and inhibits nucleotide excision repair[37-39]. However, ample evidences showed that pX may function by additional profound mechanisms in HCC[40-43].

Identification and characterization of proteins in a cell with which a given protein interacts is often helpful for understanding the function and mechanisms of action of that protein.The yeast two-hybrid system is a molecular genetic test for protein interaction, which is firstly established by Fileds et al in 1989[44].It’s a powerful and sensitive technique for the identification of genes that code for proteins which interact in a biologically significant fashion with a protein of interest. The assay is performed in the yeast cells so as to reflect the real situations in vivo and has the potential to identify the weak and transient interaction between two protein. In addition, since the cDNA libiary can be constructed according to various type of tissues,organs and cells, many proteins interact with transcription factors, protein kinases, phosphatases, receptors, cytoskeletal proteins as well as proteins involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis can be study by this elegant approach. Although the yeast two-hybrid system has become a standard procedure for molecular biologists, it remains some deficiency. The most important problem is different types of false positives, fortunately, they can be eliminated by other method such as segregation analysis and mating experiment[29,45].

Our study successfully constructed the bait vector pAS2-1X, HIS and ADE independent growth and blue -colony formation in the α -gal assay by yeast cells harboring both pAS2-1X and pACT2-cDNA recombinant plasmids and the behaviors of cells in false-positive elimination tests suggested the isolated clones can specifically interact with pX and the results were reliable.

It should be greatly concerned that XAPs studied by the yeast two-hybrid system in the past were different in size, structure and biological functions[46]: Lee et al[47] indentified an XAP1 that is a human homolog of the monkey UV-damaged DNA-binding protein in 1995; Kuzhandaivelu et al[48] discovered an XAP2 which is known as the p38 subunit of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex (ARA9) in 1996; Huang et al[49] reported an XAPC7 contained a polypeptide with high sequence homology to the PROS-28.1 subunit of proteasome of Drosophila melanogaster and the α proteasome subunit of Arabidopsis thalinna in 1996; Cong et al[50] isolated an XAP3 which is a human homolog of the rat protein kinase C-binding protein in 1997; Melegari et al[51] proved an XIP incluing two consensus phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C and Casein kinase II in 1998; Sun et al[52]demonstrared a p55sen appeared to be related to the family of EGF-like protein in gengeral in 1998; Rahmani et al[53,54] identified an HVDVC3 which is a third member of the family of human genes that encode the voltage-dependent anion channel. The reasonable explantation for these distinct results has not been obtained yet. Whether there exists different kinds of XAP or funtional fragment interacting with pX or the repetitive results depend on the high transformation efficiency remains obscure. One of the possible mechanism may be a specific fragment can interact with pX specially and the proteins containing this fragment thus can bind to pX. Sequence analysis shown that both two true positive clones we isolated contained the sequence encodes glutacid-leucine -alanine, therefore, it’s rational to deduce this short peptide is a required site for XAP binding to pX.

The interaction of proteins shall locate at nucleus in yeast two-hybrid system. However, some proteins require modification such as glycosylation outside the necleus after the expression, and others are only correctily folded and actived in the cooperation of some particular proteins which don’t exist in yeast cells, so not all proteins can obtain normal structure and biological function in yeast cells. The cDNA library used for seeking XAP in the past research including Epstein-Barr virus transformed human peripheral lymphocyte cDNA library, Hela λ gt11 cDNA library or senescent human liver cDNA library, were all library consititued from abnormal cells.Our study had not isolated integrated cDNA sequence of XAP partly owing to the difference between normal human liver cDNA library and abnormal cells cDNA library in protein’s expression, modification and activation.

In conclusion, the short peptide(glutacid-leucine-alanine) is a possibly required site for XAP binding to pX. Normal human liver cDNA library has difficulties in expressing the integrated XAP on yeast cells.

Footnotes

Edited by Wang JH and Xu XQ

References

- 1.Kong XB, Yang ZK, Liang LJ, Huang JF, Lin HL. Overexpression of P-glycoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical implication. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:134–135. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun JJ, Zhou XD, Liu YK, Zhou G. Phase tissue intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in nude mice human liver cancer metastasis model. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:314–316. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i4.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao CZ, Dai YM, Yu HY, Wang JJ, Ni CR. Relationship between expression of CD44v6 and nm23-H1 and tumor invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:412–414. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i5.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng T, Zeng ZC, Zhou L, Chen WY, Zuo YP. Detection of human liver-specific F antigen in serum and its preliminary application. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:175–176. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin GY, Chen ZL, Lu CM, Li Y, Ping XJ, Huang R. Immunohistochemical study on p53, H-rasp21, c-erbB-2 protein and PCNA expression in HCC tissues of Han and minority ethnic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:234–238. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang XF, Wang CM, Dai XW, Li ZJ, Pan BR, Yu LB, Qian B, Fang L. Expressions of chromogranin A and cathepsin D in human primary hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:693–698. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mei MH, Xu J, Shi QF, Yang JH, Chen Q, Qin LL. Clinical significance of serum intercellular adhesion molecule-1 detection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:408–410. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao CY, Li YL, Liu SX, Feng ZJ. Changes of IL-6 and relevant cytokines in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and their clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(Suppl 3):33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu DY, Moon HB, Son JK, Jeong S, Yu SL, Yoon H, Han YM, Lee CS, Park JS, Lee CH, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X-protein. J Hepatol. 1999;31:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu HZ, Cheng GX, Chen JQ, Kuang SY, Cheng Y, Zhang XL, Li HD, Xu SF, Shi JQ, Qian GS, et al. Preliminary study on the production of transgenic mice harboring hepatitis B virus X gene. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:536–539. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i6.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang XZ, Tao QM. The relationship between HBV x gene and hepatocellular carcinoma. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1999;7:1063–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu DY, Moon HB, Son JK, Jeong S, Yu SL, Yoon H, Han YM, Lee CS, Park JS, Lee CH, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X-protein. J Hepatol. 1999;31:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao FG, Sun WS, Cao YL, Zhang LN, Song J, Li HF, Yan SK. HBx-DNA probe preparation and its application in study of hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:320–322. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i4.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feitelson MA. Hepatitis B x antigen and p53 in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s005340050060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin LL, Su JJ, Li Y, Yang C, Ban KC, Yian RQ. Expression of IGF- II, p53, p21 and HBxAg in precancerous events of hepatocarcinogenesis induced by AFB1 and/or HBV in tree shrews. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:138–139. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara-Pezzi E, Serrador JM, Montoya MC, Zamora D, Yáñez-Mó M, Carretero M, Furthmayr H, Sánchez-Madrid F, López-Cabrera M. The hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) induces a migratory phenotype in a CD44-dependent manner: possible role of HBx in invasion and metastasis. Hepatology. 2001;33:1270–1281. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin GY, Chen ZL, Lu CM, Li Y, Ping XJ, Huang R. Immunohistochemical study on p53, H-rasp21, c-erbB-2 protein and PCNA expression in HCC tissues of Han and minority ethnic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:234–238. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun BH, Zhang J, Wang BJ, Zhao XP, Wang YK, Yu ZQ, Yang DL, Hao LJ. Analysis of in vivo patterns of caspase 3 gene expression in primary hepatocellular carcinoma and its relationship to p21(WAF1) expression and hepatic apoptosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:356–360. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng DY, Zheng H, Tan Y, Cheng RX. Effect of phosphorylation of MAPK and Stat3 and expression of c-fos and c-jun proteins on hepatocarcinogenesis and their clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:33–36. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natoli G, Avantaggiati ML, Chirillo P, Puri PL, Ianni A, Balsano C, Levrero M. Ras- and Raf-dependent activation of c-jun transcriptional activity by the hepatitis B virus transactivator pX. Oncogene. 1994;9:2837–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lara-Pezzi E, Majano PL, Gómez-Gonzalo M, García-Monzón C, Moreno-Otero R, Levrero M, López-Cabrera M. The hepatitis B virus X protein up-regulates tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1998;28:1013–1021. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caselmann WH. Trans-activation of cellular genes by hepatitis B virus proteins: a possible mechanism of hepatocarcinogenesis. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:253–302. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60737-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hildt E, Hofschneider PH, Urban S. The role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Virol. 1996;7:333–347. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura T, Lin Y, Dorjsuren D, Ohno S, Yamashita T, Murakami S. Human hepatitis B virus X protein is detectable in nuclei of transfected cells, and is active for transactivation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1453:330–340. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Z, Zhang Z, Doo E, Coux O, Goldberg AL, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B virus X protein is both a substrate and a potential inhibitor of the proteasome complex. J Virol. 1999;73:7231–7240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7231-7240.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Moriya K, Fujie H, Tsutsumi T, Kanegae Y, Kimura S, Saito I, Koike K. Induction of apoptosis after switch-on of the hepatitis B virus X gene mediated by the Cre/loxP recombination system. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 12):3257–3265. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maguire HF, Hoeffler JP, Siddiqui A. HBV X protein alters the DNA binding specificity of CREB and ATF-2 by protein-protein interactions. Science. 1991;252:842–844. doi: 10.1126/science.1827531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lara-Pezzi E, Armesilla AL, Majano PL, Redondo JM, López-Cabrera M. The hepatitis B virus X protein activates nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT) by a cyclosporin A-sensitive pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:7066–7077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gietz RD, Triggs-Raine B, Robbins A, Graham KC, Woods RA. Identification of proteins that interact with a protein of interest: applications of the yeast two-hybrid system. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;172:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun BH, Zhao XP, Wang BJ, Yang DL, Hao LJ. FADD and TRADD expression and apoptosis in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:223–227. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XZ, Chen XC, Yang YH, Chen ZX, Huang YH, Tao QM. Relationship between HBxAg and Fas/FasL in patients with hepatocelluar carcionoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(suppl 3):17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin EC, Shin JS, Park JH, Kim H, Kim SJ. Expression of fas ligand in human hepatoma cell lines: role of hepatitis-B virus X (HBX) in induction of Fas ligand. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:587–591. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990812)82:4<587::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottlob K, Fulco M, Levrero M, Graessmann A. The hepatitis B virus HBx protein inhibits caspase 3 activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33347–33353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SG, Rho HM. Transcriptional repression of the human p53 gene by hepatitis B viral X protein. Oncogene. 2000;19:468–471. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H, Kim HT, Yun Y. Liver-specific enhancer II is the target for the p53-mediated inhibition of hepatitis B viral gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19786–19791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prost S, Ford JM, Taylor C, Doig J, Harrison DJ. Hepatitis B x protein inhibits p53-dependent DNA repair in primary mouse hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33327–33332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groisman IJ, Koshy R, Henkler F, Groopman JD, Alaoui-Jamali MA. Downregulation of DNA excision repair by the hepatitis B virus-x protein occurs in p53-proficient and p53-deficient cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:479–483. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jia L, Wang XW, Harris CC. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits nucleotide excision repair. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:875–879. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<875::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker SA, Lee TH, Butel JS, Slagle BL. Hepatitis B virus X protein interferes with cellular DNA repair. J Virol. 1998;72:266–272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.266-272.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin GY, Chen ZL, Lu CM, Li Y, Ping XJ, Huang R. Immunohistochemical study on p53, H-rasp21, c-erbB-2 protein and PCNA expression in HCC tissues of Han and minority ethnic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:234–238. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SW, Lee YM, Bae SK, Murakami S, Yun Y, Kim KW. Human hepatitis B virus X protein is a possible mediator of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:456–461. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lian Z, Liu J, Pan J, Satiroglu Tufan NL, Zhu M, Arbuthnot P, Kew M, Clayton MM, Feitelson MA. A cellular gene up-regulated by hepatitis B virus-encoded X antigen promotes hepatocellular growth and survival. Hepatology. 2001;34:146–157. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qin LL, Su JJ, Li Y, Yang C, Ban KC, Yian RQ. Expression of IGF- II, p53, p21 and HBxAg in precancerous events of hepatocarcinogenesis induced by AFB1 and/or HBV in tree shrews. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:138–139. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bartel P, Chien CT, Sternglanz R, Fields S. Elimination of false positives that arise in using the two-hybrid system. Biotechniques. 1993;14:920–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang XZ, Tao QM. Advances on research of hepatitis B virus pX associated Protein. GanZang. 2000;5:55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee TH, Elledge SJ, Butel JS. Hepatitis B virus X protein interacts with a probable cellular DNA repair protein. J Virol. 1995;69:1107–1114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1107-1114.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuzhandaivelu N, Cong YS, Inouye C, Yang WM, Seto E. XAP2, a novel hepatitis B virus X-associated protein that inhibits X transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4741–4750. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, Kwong J, Sun EC, Liang TJ. Proteasome complex as a potential cellular target of hepatitis B virus X protein. J Virol. 1996;70:5582–5591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5582-5591.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cong YS, Yao YL, Yang WM, Kuzhandaivelu N, Seto E. The hepatitis B virus X-associated protein, XAP3, is a protein kinase C-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16482–16489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melegari M, Scaglioni PP, Wands JR. Cloning and characterization of a novel hepatitis B virus x binding protein that inhibits viral replication. J Virol. 1998;72:1737–1743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1737-1743.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun BS, Zhu X, Clayton MM, Pan J, Feitelson MA. Identification of a protein isolated from senescent human cells that binds to hepatitis B virus X antigen. Hepatology. 1998;27:228–239. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahmani Z, Maunoury C, Siddiqui A. Isolation of a novel human voltage-dependent anion channel gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:337–340. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahmani Z, Huh KW, Lasher R, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis B virus X protein colocalizes to mitochondria with a human voltage-dependent anion channel, HVDAC3, and alters its transmembrane potential. J Virol. 2000;74:2840–2846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2840-2846.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]