Abstract

Evidence suggests that diets meeting recommendations for fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake are more costly. Dietary costs may be a greater constraint on the diet quality of people of lower socioeconomic position (SEP). The aim of this study was to examine whether dietary costs are more strongly associated with F&V intake in lower-SEP groups than in higher-SEP groups. Data on individual participants’ education and income were available from a population-based, cross-sectional study of 10 020 British adults. F&V intake and dietary costs (GBP/d) were derived from a semi-quantitative FFQ. Dietary cost estimates were based on UK food prices. General linear models were used to assess associations between SEP, quartiles of dietary costs and F&V intake. Effect modification of SEP gradients by dietary costs was examined with interaction terms. Analysis demonstrated that individuals with lowest quartile dietary costs, low income and low education consumed less F&V than individuals with higher dietary costs, high income and high education. Significant interaction between SEP and dietary costs indicated that the association between dietary costs and F&V intake was stronger for less-educated and lower-income groups. That is, socioeconomic differences in F&V intake were magnified among individuals who consumed lowest-cost diets. Such amplification of socioeconomic inequalities in diet among those consuming low-cost diets indicates the need to address food costs in strategies to promote healthy diets. In addition, the absence of socioeconomic inequalities for individuals with high dietary costs suggests that high dietary costs can compensate for lack of other material, or psychosocial resources.

Key words: Economics, Food prices, Fruit and vegetable intake, Socioeconomic status

Consumption of a healthy diet is a priority for reducing obesity and its associated chronic diseases( 1 ). People who do not meet dietary guidelines such as for fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake are at an increased risk of CVD( 2 ) and all-cause mortality( 3 ). However, a study in a representative sample of UK adults showed that diets meeting F&V recommendations were more costly( 4 ). This is concordant with a line of research in the USA showing that adherence to a healthy diet (lower energy-density, higher intake of vitamins, minerals and dietary fibre) is more costly than adherence to a less healthy diet( 5 – 7 ).

Economic factors such as food price, cost of healthy diets, personal or household income or the amount of money available to purchase food may be important for dietary quality( 5 , 6 , 8 – 12 ). Studies have shown that constraining food budgets can lower the nutritional adequacy of the diet( 13 , 14 ) and that economic uncertainty may adversely affect people’s food choices( 15 ). Dietary costs may therefore be a barrier for the uptake and maintenance of healthy diets( 16 , 17 ).

Dietary costs as a constraint on diet quality could be especially crucial for less-educated groups, who tend to prioritise low-cost in food choices( 18 ) and may lack other resources that motivate healthy eating( 19 – 24 ). Socioeconomic disparities in health and nutrition are well-documented( 25 – 31 ). There is some evidence suggesting that dietary costs are in the causal pathway between socioeconomic position (SEP) and diet( 8 , 9 , 30 , 31 ). On the other hand, one study reported that the association between income, diet cost and diet quality was stronger in less-educated individuals than in more-educated individuals( 9 ). This suggests that SEP can act as a moderator in the relationship between dietary cost and diet. Yet, it remains to be evaluated whether dietary costs are equally important for diet quality across socioeconomic groups.

In a UK population-based cross-sectional study with data on SEP (defined as education and income), individual dietary costs and diet quality, we sought to describe whether the association between dietary costs and F&V intake varied across socioeconomic groups. We hypothesised that SEP, dietary costs and F&V intake would be inter-related, and more specifically that dietary costs would be more strongly associated with F&V intake for people of low SEP than people of high SEP.

Methods

Study sample

The Fenland Study is a population-based cohort study of adults born between 1950 and 1975 and registered with general practices in Cambridgeshire, UK, conducted by the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit( 32 ). The study aimed to include at least 10 000 adults. Recruitment started in 2005, and included attendance to one of three clinical sites in Cambridgeshire for a highly detailed in-person assessment with numerous anthropometric, biological and clinical measurements. At the time of the present analysis, complete data from 10 452 participants were available (collected between 2005 and 2013). Exclusion criteria of the Fenland Study included pregnancy, previously diagnosed diabetes, inability to walk unaided, psychosis or terminal illness. We excluded participants with extreme values for energy intake based on sex-specific cutoffs suggested by Willett( 33 ). In addition, we excluded participants with no data on energy intake. This resulted in an analytic sample of 9911 participants.

Ethical approvals

The study was approved by the NRES Committee – East of England Cambridge Central – and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Demographics and socioeconomic position

Self-reported data on sex, age and household size (for analysis with income as SEP) were obtained from the Fenland questionnaire. For each participant, self-reported highest educational qualification and annual household income were used as indicators of SEP. Education was measured in four categories: ‘no qualifications’, ‘compulsory education’ (O-levels or general certificate of secondary education), ‘further education’ (A-levels and vocational equivalents) and ‘higher education’ (degree level). Educational attainment was stratified into ‘<11 years of education’ (included no qualifications and general certificate of secondary education), ‘11–13 years of education’ (A-levels) and ‘16+ years of education’ (included university degree or equivalent and beyond). Household income was measured in three strata: <£20 000, £20 000–40 000 and >£40 000 per year. Participants self-reported smoking status as ‘current’, ‘former’ or ‘never’.

Dietary assessment

Participants recorded the frequency and portions of consumption of foods and beverages by completing a 130-item, semi-quantitative FFQ to assess habitual consumption of food. This FFQ has been used in the UK EPIC studies, and it has been shown to generate reproducible and valid food intake assessments( 34 ). Nutrition composition analyses of dietary intake data yielded grams of daily intake of F&V, which we used as primary outcome variables. Fruit included eleven items from the FFQ, including fresh, dried and tinned varieties, but excluded fruit juice. Vegetables included twenty-six items from the FFQ, including fresh, frozen and tinned varieties, but not potatoes. A variable on alcohol intake was derived on the basis of four items in the FFQ. Participants reported on their weekly intake of units ‘wine’, ‘beer, lager or cider’, ‘port, sherry, vermouth, liquers’ and ‘spirits’. Weekly unit intake was transformed into grams of alcohol intake per d (1 U=8 g of ethanol).

Dietary costs

We used established techniques to derive the monetary costs of diets( 35 , 36 ). Individual dietary costs (the monetary value attached to consumed diets) were estimated by merging a food price variable with the FFQ nutrient composition database( 35 ). Retail prices for each of the foods in the FFQ were obtained in June 2012 from five key supermarket chains using MySupermarket.com, a website for comparing supermarket food prices nationwide in the UK. These five nationwide retailers (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Waitrose and Ocado) together had a 68 % market share in 2012( 37 ). The lowest, non-promotion price from the five retailers was selected. For packaged goods including most fresh produce, the medium package size was typically selected. Prices were adjusted for preparation and waste( 36 ) to yield an adjusted food price for each 100 g edible portion( 38 ). Combining this new variable with the Fenland food and nutrient database allowed the derivation of the monetary value of each participant’s diet. The variable obtained for each respondent was dietary costs per d (£/d – crude diet cost). Three dietary cost variables were used for analysis: (1) crude dietary cost, (2) dietary cost per 8·4 MJ and (3) energy-adjusted dietary costs. The dietary cost per 8·4 MJ (2000 kcal) reflects a daily energy ration for many adults, and it has been used widely in the literature (e.g.( 13 , 39 , 40 )). The energy-adjusted dietary costs variable was created by energy-adjusting daily (crude) diet costs on the method of residuals and then categorised into quartiles( 41 ), a standard energy adjustment and stratification technique in epidemiological studies( 35 ).

Analytical approach

First, general linear model analysis was applied to describe the socioeconomic gradient in combined F&V intake and dietary costs as continuous variables, using both education and income as socioeconomic predictors. The addition of covariates into the models was theoretically informed a priori, and it included age, sex, energy intake (for analysis with crude dietary costs as outcome) and household size (for analysis with income as socioeconomic indicator). Smoking and alcohol intake variables were tested as additional confounders but were left out of the models as they did not change the coefficients by >10 %. Both daily (crude) dietary costs and dietary cost per 8·4 MJ were examined as dependent variables. Second, we examined dietary costs as an independent variable by stratifying energy-adjusted dietary costs into quartiles and presenting participant characteristics across quartiles. Quartiles were based on the entire sample, and thus all quartiles of dietary costs were equal. Finally, we examined the joint associations between combined F&V intake by (energy adjusted) dietary cost quartiles and SEP. A cross-product term of dietary cost quartiles and SEP was added to the adjusted model to test for effect modification by SEP. As sensitivity analysis, we additionally adjusted the models with interactions between dietary cost quartiles and education for income, and the models with interactions between dietary cost quartiles and income for education.

Given the low prevalence of missing data, we conducted complete case analysis. A two-sided α level of 0·05 was used to test for statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0.

Results

Mean age of the participants was 47·8 years (sd 7·4), and 46·1 % were men. Half of the sample had household incomes over £40 000 per year and 14 % had household income <£20 000 per year. Nearly one-third of the sample had a university degree or higher, and 45 % of the sample had further education. Women reported lower energy intake than men (7·7 v. 8·8 MJ/d) but a higher intake of F&V (585 v. 474 g/d) than men. The average estimated dietary costs were £4·26 per d and £4·46 per 8·4 MJ.

Table 1 shows the mean F&V intake (g/d) by demographic strata. After adjustment for sex, F&V intake and dietary costs both increased with age. After adjustment for age, women reported eating more F&V. Relative to people with highest educational attainment, those with the lowest level of education had a 10 % lower mean F&V intake after adjustment for sex and age (501 v. 553 g for lowest and highest education, respectively). Similarly, relative to people with highest incomes, those with lowest incomes had a 6 % lower mean F&V intake after adjustment for sex and age (511 v. 545 g). These trends were all statistically significant.

Table 1.

Mean daily fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake and dietary costs by demographic and sociodemographic strata among UK adults – The Fenland Study (Mean values and 95 % confidence intervals)

| F&V intake (g/d) | Daily dietary cost (£/d) | Dietary energy cost (£/8·4 MJ) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | 95 % CI | Mean | 95 % CI | Mean | 95 % CI | |

| Total | 9911 | 528 | 522, 533 | 4·22 | 4·20, 4·25 | 4·48 | 4·46, 4·50 |

| Age group (years)* | |||||||

| 29–39 | 1427 | 498 | 483, 512 | 4·14 | 4·08, 4·21 | 4·25 | 4·20, 4·30 |

| 40–49 | 3932 | 510 | 502, 519 | 4·21 | 4·17, 4·25 | 4·38 | 4·35, 4·41 |

| 50–59 | 4003 | 541 | 532, 549 | 4·26 | 4·22, 4·30 | 4·57 | 4·54, 4·60 |

| ≥60 | 549 | 557 | 534, 581 | 4·28 | 4·18, 4·39 | 4·73 | 4·65, 4·81 |

| P trend | <0·001 | 0·015 | <0·001 | ||||

| Sex† | |||||||

| Male | 4551 | 472 | 462, 482 | 4·29 | 4·24, 4·33 | 4·24 | 4·21, 4·28 |

| Female | 5360 | 581 | 572, 590 | 4·16 | 4·12, 4·20 | 4·72 | 4·69, 4·75 |

| P difference | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | ||||

| Educational attainment (years)‡ | |||||||

| ≤11 | 2157 | 497 | 484, 509 | 4·13 | 4·07, 4·19 | 4·39 | 4·33, 4·43 |

| 13 | 4377 | 525 | 515, 534 | 4·27 | 4·22, 4·31 | 4·50 | 4·46, 4·53 |

| 16+ | 3074 | 547 | 537, 558 | 4·23 | 4·18, 4·28 | 4·52 | 4·45, 4·56 |

| P trend | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | ||||

| Household income (£/year)§ | |||||||

| <20 000 | 1320 | 504 | 488, 520 | 4·14 | 4·06, 4·21 | 4·21 | 4·15, 4·27 |

| 20 000–40 000 | 3458 | 523 | 512, 533 | 4·22 | 4·17, 4·28 | 4·34 | 4·30, 4·38 |

| >40 000 | 4833 | 538 | 528, 548 | 4·28 | 4·23, 4·33 | 4·61 | 4·57, 4·65 |

| P trend | <0·001 | <0·002 | <0·001 | ||||

Adjusted for sex.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for sex and age. Additionally adjusted for energy intake (MJ/d) when F&V intake or daily dietary cost was the dependent variable, 3 % (303 individuals) had missing data on educational attainment.

Adjusted for sex, age and household composition. Additionally adjusted for energy intake (MJ/d) when F&V intake or daily dietary cost was the dependent variable, 7 % (671 individuals) had missing values on household composition and 3 % (300 individuals) had missing values on income.

Both income and educational attainment were positively associated with higher mean dietary costs per d and higher mean dietary costs per 8·4 MJ. Whereas education was more strongly related to F&V intake, income was more strongly related to diet cost. The difference in daily dietary costs between those with lowest v. highest incomes was approximately 7 %, whereas the difference between those with lowest v. highest educational attainment was approximately 3 %. Results for dietary costs per 8·4 MJ were similar, with a 9 % difference by income and 3 % difference by education.

Participant characteristics and dietary intakes were systematically associated with diet cost. Table 2 shows the characteristics of participants within quartiles of energy-adjusted diet cost. Participants with lower energy-adjusted dietary costs were on average younger, more likely to be male, consuming less alcohol and were more likely to be current smokers. Mean F&V intake was 50 % lower among those in the lowest quartile of energy-adjusted dietary costs compared with the highest (742 v. 375 g/d, respectively).

Table 2.

Characteristics of individuals within quartiles of energy-adjusted dietary costs in the Fenland Study (Mean values and standard deviations; percentages; n 10 020)

| Q1 [0·7–3·6]* | Q2 [3·6–4·1]* | Q3 [4·1–5·0]* | Q4 [5·0–14·9]* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | |

| Age (years) | 46·7 | 7·5 | 47·4 | 7·4 | 48·3 | 7·4 | 49·0 | 7·2 |

| Sex (% women) | 42·9 | 52·4 | 57·2 | 63·2 | ||||

| Low education (%)† | 26·1 | 21·3 | 21·0 | 21·3 | ||||

| Low income (%)‡ | 18·2 | 13·1 | 11·8 | 11·7 | ||||

| Current smoker (%) | 15·2 | 13·2 | 9·4 | 14·1 | ||||

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 86·3 | 149·2 | 118·5 | 172·4 | 158·7 | 230·2 | 244·9 | 351·2 |

| Fruit intake (g/d) | 167·7 | 134·0 | 214·1 | 147·5 | 258·5 | 170·7 | 350·0 | 285·8 |

| Vegetable intake (g/d) | 202·6 | 95·7 | 243·1 | 99·1 | 289·3 | 109·1 | 386·6 | 192·7 |

| Combined F&V intake (g/d) | 370·3 | 179·8 | 457·3 | 187·0 | 547·7 | 214·4 | 736·6 | 381·0 |

| Energy intake (MJ/d) | 8·5 | 2·7 | 7·8 | 2·3 | 7·8 | 2·2 | 8·4 | 2·3 |

F&V, fruit and vegetable.

Values in brackets indicate the range in crude costs within each quartile. Q1 represents the lowest quartile of dietary costs, whereas Q4 represents the highest quartile of dietary costs.

Low education was defined as ‘<11 years of education’ (included no qualifications and general certificate of secondary education). A total of 309 individuals had missing values on educational attainment.

Low income was defined as ‘<£20 000 per year’. A total of 303 individuals had missing values on income.

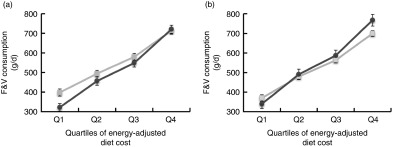

The association between dietary costs and F&V intake by strata of SEP is presented in two figures. Fig. 1(a) shows the adjusted mean (95 % CI) F&V intake per d by energy-adjusted dietary cost quartiles for those with lowest and highest educational attainment. Dietary cost was significantly and positively associated with F&V intake for all strata of education, but the association was strongest for those with lowest educational attainment. In the highest quartile of dietary cost, individuals with low educational attainment achieved similar levels of F&V intake as individuals with intermediate (not shown) and highest educational attainment. However, at lower quartiles of dietary cost, significant differences in F&V intake were apparent, and at the lowest quartile those with lowest education consumed 76 g per d (20 %) less F&V than those with highest education (P difference<0·001).

Fig. 1.

(a) Estimated mean (95 % CI) fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption (g/d) by quartiles of energy-adjusted dietary cost, stratified for educational attainment. Estimates are presented for highest (16+ years of education) and lowest (<11 years of education) educational attainment only. (b) Estimated mean (95 % CI) F&V consumption (g/d) by quartiles of dietary cost, stratified for household income. Estimates are presented for highest (>£40 000/year) and lowest (<£20 000/year) income groups only. (a)  , high education;

, high education;  , low education. (b)

, low education. (b)  , high income;

, high income;  , low income.

, low income.

The inter-relationship between income and dietary costs was slightly different. Fig. 1(b) shows the association between F&V intake across dietary costs quartiles for highest and lowest income strata. In the lowest quartile of dietary cost, those with lowest income consumed 30 g per d (8 %) less F&V than those with highest income. F&V intakes were similar between the two income groups in quartiles two and three, and a reversal was observed in the highest quartile of dietary cost, in which those with lowest income consumed 67 g per d (10 %) more than those with highest incomes.

Interaction terms for SEP indicators and energy-adjusted dietary costs confirmed the pattern shown in Fig. 1(a) and (b); the difference in F&V intake between participants with highest and lowest dietary costs was largest in those with low education (F-value for interaction-term=4·1, P<0·001) and low income (F=4·5, P<0·001). Adjusting the analysis with the education-dietary costs interaction for income and vice versa did not alter the results.

Discussion

In the present study, we confirm earlier research that higher dietary costs were associated with more healthy dietary patterns, more specifically with higher F&V intakes. Moreover, we provide novel evidence that dietary costs may have a stronger role in low socioeconomic groups. While higher F&V intakes were associated with higher dietary costs for the sample overall, educational differences were not evident in the stratum of adults with highest dietary costs but amplified among those with lower-cost diets. Within the lowest dietary costs quartile, those with highest education consumed approximately 20 % more F&V (80 g/d – equivalent to one serving) than those with lowest levels of education. This finding was consistent with our hypothesis that dietary costs would be more strongly related to F&V intake for people of low SEP than to people of high SEP.

The greater educational inequalities in F&V intake at low levels of dietary costs may reflect the importance of other, unmeasured individual factors such as one’s ability to use dietary knowledge and attitudes to achieve better-quality diets within a given food budget( 19 , 20 ). This is consistent with literature indicating that higher SEP (income, education and occupation) is associated with nutrition and health literacy and other psychosocial resources( 19 , 22 – 24 ) and may explain why more highly educated individuals consumed more F&V even at a lower diet cost. Alternatively, other – unmeasured – material resources (e.g. access to health-promoting goods and services( 42 )) may have explained the accentuated educational inequalities. Yet, the lack of a socioeconomic gradient in F&V intake at higher dietary cost levels may indicate that sufficient (food-related) material resources can compensate for a potential lack of psychosocial resources.

As demonstrated before( 43 ), the use of different socioeconomic indicators generated slightly different results. First, differences in F&V consumption between income groups in the lowest dietary cost group were much smaller than between educational groups. This may reflect the fact that income is a proxy for food budgets( 44 ). For the low income–F&V intake association, food purchasing power may be the most important factor( 45 ), whereas for the low education–F&V intake association nutritional knowledge and other psychosocial resources( 19 , 24 ) may additionally have a role. Second, individuals with the highest diet cost on lowest incomes consumed even more F&V than those with highest incomes. Examples exist of population groups who consume healthy diets despite lower income than the general population( 46 , 47 ). Alternatively, our crude income measure may not adequately reflect socioeconomic status of the person in charge of the food shopping.

Although previous studies have provided evidence that dietary costs are in the causal pathway between SEP and diet( 8 , 9 , 30 , 31 ), this study suggests that dietary costs are not equally important for F&V intake across all socioeconomic groups. Rather, educational differences in intake were only observed in individuals with the lowest diet cost. This is consistent with one study that showed that the income–diet cost–diet pathway was stronger in lower-educated individuals than in higher-educated individuals( 9 ). Dietary costs as a constraint on quality may therefore be more important for less-educated groups, who tend to prioritise low-cost in food choices( 18 ). Explanations for this prioritisation may be other competing expenditures that take precedence, or a lack of capacity to resist unhealthy environments( 48 ).

Strengths and limitations

A number of factors may have biased the results of this study. First, F&V intakes and dietary cost estimates were derived from an FFQ, which is an instrument that is subject to error and known biases( 33 , 49 ). The reported F&V intakes in our sample were relatively high. This may present an upward reporting bias (and the associated lack of heterogeneity) or over-estimation of intakes, as imputed portion sizes may have been larger than portions actually consumed. If so, this may be one explanation for the relatively shallow socioeconomic patterning. Yet, the F&V intakes found in the present study are comparable to numbers presented in previous UK studies( 50 ). Second, the definition of dietary costs used in this study should be viewed as an estimation of the intrinsic monetary value of diet, and not a measure of food expenditure( 8 ). Indeed, a study on the methods of deriving dietary costs demonstrated a downward bias, mainly for high SES individuals, which is likely to result in an underestimation of SES differentials( 35 ). Yet, it was also shown that this type of measurement of dietary cost is moderately related to actual food expenditures. In conclusion, the use of the FFQ in combination with the food price variable to derive F&V intake and dietary cost estimates has likely resulted in an underestimation of socioeconomic differences. Third, the use of this mostly white, more highly educated sample with higher household incomes may also have contributed to an underestimation of social gradients presented in this manuscript. Fourth, although individual data were collected between 2005 and 2013, dietary cost data were derived with 2012 food price data. A UK study showed that food prices had risen over the period 2002–2012, especially more healthy items( 51 ). This means that individuals who attended the study site in 2005 have been assigned to dietary costs from 2012 that are higher than their actual dietary costs in 2005. As this is especially true for individuals who consumed more F&V, this time lag may have amplified the association between dietary costs and F&V intake. Last, although in this study we found an association between SEP/dietary costs and F&V intake, this may be different for other food groups.

Strengths of this study included the large population-based sample with detailed sociodemographic and dietary measures. An additional strength is the derivation of individual-level dietary cost, which can provide some insights into the economic mechanisms that contribute to social patterns of dietary intake( 35 , 39 ). Advantages of using individual-level dietary costs in analysis is that the costs reflect the quantities and types of foods reported to be consumed( 35 ).

Conclusion

The present study has implications for epidemiological studies and public health policy. This study has provided insight into the importance of economic access to food; having higher dietary costs, a proxy for food spending( 35 ), was positively associated with F&V intake. Yet, the question of access to food has three components: economic access, physical access and behavioural and psychosocial resources that support access. It remains to be evaluated whether economic access acts as an independent factor. It is likely that environmental factors such as area deprivation or accessibility of healthy foods are important for a healthy diet as well, and thus future studies could assess the interplay between economic and physical access. In addition, cohort studies with information on dietary costs could be complemented with more detailed information on psychosocial resources such as nutrition knowledge or executive functioning. Last, future studies could examine policies that have aimed to improve financial and physical access to food simultaneously, and to evaluate their effectiveness. Potentially, a beneficial side effect of reducing financial constraints in access to healthy food may be reduced dietary inequalities.

The strong association between dietary costs and diet quality underscores the importance of economic resources as an important determinant of adherence to a healthy diet. A recent trial that involved a 20 % price-reduction intervention in combination with skill-building demonstrated significant increases in F&V purchases( 52 ). Yet, lowering the economic barriers to F&V consumption alone (e.g. by decreasing prices or increasing food budgets) may not diminish dietary inequalities by itself if other barriers are not addressed. Although food costs and economic resources should be considered in any evaluation of food access, addressing socioeconomic inequalities itself by a re-distribution of income (e.g. distribution of vouchers) or improving dietary education (e.g. stimulating cooking skills) may prove to be a worthwhile investment. Public health initiatives to promote healthy diets should address the broader environmental determinants of healthy food intake, incorporating both affordability and accessibility to prevent further widening of dietary inequalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the volunteers who participated in the Fenland Study, as well as Fenland Study Coordination, Field Epidemiology, and data management. They also thank Dr Laura O’Connor who assisted us in introducing food price data into the food and nutrient database for this cohort.

This work was undertaken by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, and Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. Core MRC Epidemiology Unit support through programmes MC_UU_12015/1 and MC_UU_12015/5 is acknowledged. Funders had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation or publication of the manuscript.

The study analysis was devised by J. D. M. and P. M. P. M., N. G. F., N. J. W., S. J. G. and S. B. were responsible for data collection. J. D. M. led on data analysis, in consultation with P. M. J. D. M. and P. M. drafted the manuscript together. All authors provided intellectual input to the manuscript. J. D. M. is the guarantor.

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, et al. (2005) The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ 83, 100–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hung H-C, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, et al. (2004) Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Nutr Cancer Inst 96, 1577–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oyebode O, Gordon-Dseagu V, Walker A, et al. (2014) Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data. J Epidemiol Community Health 68, 856–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Timmins KA, Hulme C & Cade JE (2013) Dietary value for money? Investigating how the monetary value of diets in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) relate to dietary energy density. Proc Nutr Soc 72, E295. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee JW, Ralston R & Truby H (2011) Influence of food cost on diet quality and risk factors for chronic disease: a systematic review. Nutr Diet 68, 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G, et al. (2013) Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 3, e004277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monsivais P, Aggarwal A & Drewnowski A (2011) Following federal guidelines to increase nutrient consumption may lead to higher food costs for consumers. Health Aff 30, 1471–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monsivais P, Aggarwal A & Drewnowski A (2012) Are socio-economic disparities in diet quality explained by diet cost? J Epidemiol Community Health 66, 530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, et al. (2011) Does diet cost mediate the relation between socioeconomic position and diet quality? Eur J Clin Nutr 65, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drewnowski A & Specter SE (2004) Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. J Clin Nutr 79, 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blakely T, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y, et al. (2011) Do effects of price discounts and nutrition education on food purchases vary by ethnicity, income and education? Results from a randomised, controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Heal 65, 902–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epstein LH, Jankowiak N, Nederkoorn C, et al. (2012) Experimental research on the relation between food price changes and food-purchasing patterns: a targeted review. Am J Clin Nutr 95, 789–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murakami K, Sasaki S, Takahashi Y, et al. (2009) Monetary cost of self-reported diet in relation to biomarker-based estimates of nutrient intake in young Japanese women. Public Health Nutr. 12, 1290–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drewnowski A & Darmon N (2005) Food choices and diet costs: an economic analysis. J Nutr 135, 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waterlander WE, de Haas WE, van Amstel I, et al. (2010) Energy density, energy costs and income— how are they related? Public Health Nutr 13, 1599–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Darmon N, Ferguson EL & Briend A (2002) A cost constraint alone has adverse effects on food selection and nutrient density: an analysis of human diets by linear programming. J Nutr 132, 3764–3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertoni AG, Foy CG, Hunter JC, et al. (2011) A multilevel assessment of barriers to adoption of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) among African Americans of low socioeconomic status. J Heal Care Poor Underserved 22, 1205–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bowman SA (2006) A comparison of the socioeconomic characteristics, dietary practices, and health status of women food shoppers with different food price attitudes. Nutr Res 26, 318–324. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKinnon L, Giskes K & Turrell G (2014) The contribution of three components of nutrition knowledge to socio-economic differences in food purchasing choices. Public Health Nutr 17, 1814–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McLeod ER, Campbell KJ & Hesketh KD (2011) Nutrition knowledge: a mediator between socioeconomic position and diet quality in Australian first-time mothers. J Am Diet Assoc 111, 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wardle J & Steptoe A (2003) Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health 57, 440–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caraher M, Dixon P, Lang T, et al. (1999) The state of cooking in England: the relationship of cooking skills to food choice. Br Food J 101, 590–609. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inglis V, Ball K & Crawford D (2005) Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 45, 334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anderson ES, Winett RA & Wojcik JR (2007) Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann Behav Med 34, 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith GD & Brunner E (1997) Socio-economic differentials in health: the role of nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 56, 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. James WP, Nelson M, Ralph A, et al. (1997) Socioeconomic determinants of health. The contribution of nutrition to inequalities of health. Br Med J 314, 1545–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galobardes B, Morabia A & Bernstein MS (2001) Diet and socioeconomic position: does the use of different indicators matter? Int J Epidemiol 30, 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. (2006) Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 60, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hulshof KF, Brussaard JH, Kruizinga AG, et al. (2003) Socio-economic status, dietary intake and 10 y trends: the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Darmon N & Drewnowski A (2008) Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr 87, 1107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mullie P, Clarys P, Hulens M, et al. (2010) Dietary patterns and socioeconomic position. Eur J Clin Nutr 64, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Lucia Rolfe E, Loos RJF, Druet C, et al. (2010) Association between birth weight and visceral fat in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 92, 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Willett W (1998) Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd ed New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A, et al. (1997) Validation of dietary assessment methods in the UK arm of EPIC using weighed records, and 24-hours urinary nitrogen and potassium and serum vitamin C and carotenoids as biomarkers. Int J Epidemiol 26, S137–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Monsivais P, Perrigue MM, Adams SL, et al. (2013) Measuring diet cost at the individual level: a comparison of three methods. Eur J Clin Nutr 67, 1220–1225. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Monsivais P & Drewnowski A (2009) Lower-energy-density diets are associated with higher monetary costs per kilocalorie and are consumed by women of higher socioeconomic status. J Am Diet Assoc 109, 814–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. BBC News (2012) Tesco market share dips below 30%. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-16817254 (accessed March 2015).

- 38. Paul AA & Southgate DAT (1992) McCance and Widdowson’s the Composition of Foods, 5th ed. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rehm C, Monsivais P & Drewnowski A (2011) The quality and monetary value of diets consumed by adults in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 94, 13333–13339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rydén PJ & Hagfors L (2011) Diet cost, diet quality and socio-economic position: how are they related and what contributes to differences in diet costs? Public Health Nutr 14, 1680–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Willett W & Stampfer M (1998) Implications for total energy intake for epidemiologic analyses In Nutritional Epidemiology, pp. 273–301 [W Willett, editor]. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Braveman P, Egerter S & Barclay C (2011) Exploring the Social Determinants of Health. Income, Wealth and Health. San Fransisco, CA: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vlismas K, Stavrinos V & Panagiotakos DB (2009) Socio-economic status, dietary habits and health-related outcomes in various parts of the world: a review. Cent Eur J Public Health 17, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Turrell G, Hewitt B, Patterson C, et al. (2003) Measuring socio-economic position in dietary research: is choice of socioeconomic indicator important? Public Health Nutr 6, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Turrell G & Kavanagh AM (2006) Socio-economic pathways to diet: modelling the association between socio-economic position and food purchasing behaviour. Public Health Nutr 9, 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Darmon N & Khlat M (2001) An overview of the health status of migrants in France, in relation to their dietary practices. Public Health Nutr 4, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Monsivais P, Rehm CD & Drewnowski A (2013) The DASH diet and diet costs among ethnic and racial groups in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 173, 1922–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marteau TM & Hall PA (2013) Breadlines, brains, and behaviour. BMJ 347, f6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Drewnowski A (2001) Diet image: a new perspective on the foodfrequency questionnaire. Nutr Rev 59, 370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mulligan AA, Luben RN, Bhaniani A, et al. (2014) A new tool for converting FFQ data into nutrient and food group values: FETA research methods and availability. BMJ Open 4, e004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jones NRV, Conklin AI, Suhrcke M, et al. (2014) The Growing Price Gap between More and Less Healthy Foods: Analysis of a Novel Longitudinal UK Dataset. PLOS ONE 9, e109343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ball K, Mcnaughton SA, Le HND, et al. (2015) Influence of price discounts and skill-building strategies on purchase and consumption of healthy food and beverages: outcomes of the supermarket healthy eating for life randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 101, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]