Abstract

Background

Lake Tanganyika in the African Great Rift Valley is known as a site of adaptive radiation in cichlid fishes. Diverse herbivorous fishes coexist on a rocky littoral of the lake. Herbivorous cichlids have acquired multiple feeding ecomorphs, including grazer, browser, scraper, and scooper, and are segregated by dietary niche. Within each ecomorph, however, multiple species apparently coexist sympatrically on a rocky slope. Previous observations of their behavior show that these cichlid species inhabit discrete depths separated by only a few meters. In this paper, using carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) stable isotope ratios as markers, we followed the nutritional uptake of cichlid fishes from periphyton in their feeding territories at various depths.

Results

δ15N of fish muscles varied among cichlid ecomorphs; this was significantly lower in grazers than in browsers and scoopers, although δ15N levels in periphyton within territories did not differ among territorial species. This suggests that grazers depend more directly on primary production of periphyton, while others ingest animal matter from higher trophic levels. With respect to δ13C, only plankton eaters exhibited lower values, suggesting that these fishes depend on production of phytoplankton, while the others depend on production of periphyton. Irrespective of cichlid ecomorph, δ13C of periphyton correlated significantly with habitat depth, and decreased as habitat depth became deeper. δ13C in territorial fish muscles was significantly related to that of periphyton within their territories, regardless of cichlid ecomorph, which suggests that these herbivorous cichlids depend on primary production of periphyton within their territories.

Conclusions

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios varied among ecomorphs and among cichlid species in the same ecomorphs sympatrically inhabiting a littoral area of Lake Tanganyika, suggesting that these cichlids are segregated by nutrient source due to varying dependency on periphyton in different ecomorphs (especially between grazers and browsers), and due to segregation of species of the same ecomorph by feeding depth, grazers and browsers in particular.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40851-015-0016-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tanganyikan cichlid, Stable isotope, Herbivore, Ecomorph, Adaptive radiation

Background

Cichlid fish communities in Lake Tanganyika are a magnificent example of adaptive radiation, in which mulitple species rapidly evolve from a common ancestor as a consequence of their adaptation to various ecological niches. After the formation of the lake 9–12 Ma, more than 200 species have diverged from eight colonizing lineages [1-4].

In a rocky littoral of Lake Tanganyika, 17 species of herbivorous cichlids coexist [5,6]. These include 11 Tropheini, three Lamprologini, one Ectodini, one Eretmodini, and one Tilapini species (Table 1). Therefore, this herbivorous fish community has become established through repetitive adaptations to herbivory in these cichlid tribes [4].

Table 1.

Study species of herbivorous fishes in Lake Tanganyika and their ecomorphs based on feeding habits, territoriality, and the number of samples we collected

| Tribe | Species | Abbreviation | Feeding ecomorph | Feeding territory | Number of algal farms | Sampling depth (m) | Number of fish individuals | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tilapiini | Oreochromis tanganicae | Otan | biter | no | - | - | 5 | [13,52] |

| Ectodini | Xenotilapia papilio | Xpap | scooper | breeding pairs only | - | - | 5 | [13,14] |

| Eretmodini | Eretmodus cyanostictus | Ecya | scraper | breeding pairs only | 5 | 2.2(1.9-2.4) | 5 | [53,54] |

| Lamprologini | Telmatochromis temporalis | Ttem | browser | yes | 4 | 8.1(2.4-19.6) | 5 | [7,55] |

| Lamprologini | Telmatochromis vittatus | Tvit | browser | no | - | 5 | [56] | |

| Lamprologini | Variabilichromis moorii | Vmoo | browser | yes | 5 | 4.6(2.5-6.7) | 5 | [57] |

| Tropheini | Interochromis loocki | Iloo | grazer | dominant males only | 3 | 6.8(3.1-13.0) | 5 | [39] |

| Tropheini | Pseudosimochromis curvifrons | Pcur | browser | dominant males only | 5 | 1.3(1.0-2.1) | 5 | [7,20] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis famula | Pfam | grazer | dominant males only | - | - | 5 | [19] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis fasciolatus | Pfas | grazer | dominant males only | - | - | 5 | [58,59] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis macrognathus | Pmac | grazer | yes | 5 | 0.3(0.3-0.4) | 5 | [60] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis polyodon | Ppol | grazer | yes | 4 | 3.0(2.5-3.3) | 5 | [7] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis horii | Phor | grazer | yes | 3 | 15.2(15.0-15.7) | 4 | [61] |

| Tropheini | Petrochromis trewavasae | Ptre | grazer | yes | 6 | 10.1(6.4-13.7) | 5 | [7] |

| Tropheini | Simochromis diagramma | Sdia | browser | no | - | - | 5 | [7] |

| Tropheini | Tropheus moorii | Tmoo | browser | yes | 3 | 8.7(6.0-10.5) | 5 | [7,16,62] |

| Tropheini | Limnotilapia dardennii | Ldar | browser | no | - | - | 5 | [10] |

| non-cichlid | Lamprichthys tanganicanus | Ltan | plankton eater | no | - | - | 5 | [63] |

| non-cichlid | mixed of Stolothrissa tanganicae and Limnothrissa miodon | Kape | plankton eater | no | - | - | 5 | [63] |

Sampling depth indicate the depth in which algal farm samples were collected, shown as in average (minimum - maximum).

Tanganyikan cichlids are unique in the richness of convergent forms that evolved in the lake and coexist in similar habitats [4]. Five tribes of the family have acquired multiple herbivorous feeding ecomorphs; specifically, grazer, browser, scooper, and scraper [7-10]. Grazers comb unicellular algae from epilithic assemblages using multiple rows of similar-sized slender teeth with fork-like tricuspid tips [11,12]. Browsers nip and nibble filamentous algae using their bicuspid teeth, which line the outermost edges of both jaws [9]. Scoopers protrude and thrust their jaws into sand, intake a small amount of sand, and then eject it from the mouth or gill-openings to filter prey [13,14]. Scrapers rub epiphyton from rock surfaces using several rows of chisel-like teeth [15]. Fishes in each feeding ecomorph exhibit distinct specialized morphologies, such as jaw structure [8,16] and intestine length [17,18], physiological abilities, such as specific digestive enzymes [17], and specialized behaviours such as cropping frequency, substratum choice for feeding [7,16] and territoriality [19,20]. How do sympatric herbivorous cichlid species specialize by feeding depth and consequent food-source segregation to enable coexistence of closely relative species with similar feeding ecomorphs?

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios were used as indicators of material flow from primary producers to herbivorous cichlids. Stable carbon isotopes are known to vary by water depth due to light intensity, photosynthetic activity and consequent dissolved CO2 availability differ along water depth [21-23]. This value can thus indicate the relative depth at which the carbon source of cichlid fish is produced. The dependence of cichlids on primary production can be estimated by nitrogen stable isotope ratio. The composition of algal farms and stomach contents were analyzed by an amplicon metagenomics approach in a previous study [6], and it shows that algal farm composition is varied in the axis of depth, but stomach contents are highly variable among cichlid species, even those inhabiting similar depth ranges. Stomach content analyses show directly what is ingested, but there are limitations; not all ingested material is assimilated, some food items are dissolved in the stomach more quickly than others, and stomach content reflects feeding during only the short periods immediately before capture [24-26]. Therefore, in addition to stomach content analysis, stable isotope markers that provide time-integrated information can be useful tools for determining dietary sources for each cichlid species and clarifying the basis of their dietary segregation.

On a rocky littoral in Lake Tanganyika, we observed algal farms of 10 herbivorous cichlid species, measured the water depth, and collected periphyton inside the farms. At the same time, specimens of 17 herbivorous cichlid species sympatrically inhabiting a rocky shore and three plankton-eating fishes were collected. Algal farms and fish muscles were analyzed using carbon and stable isotope analyses.

Methods

Sampling for stable isotope analysis

This study was performed in accordance with the Regulations on Animal Experimentation at Ehime University. Approval is not needed for experimentation on fishes under Japanese law, Act on Welfare and Management of Animals. We sampled 17 species of herbivorous cichlids from Kasenga Point (8°43′S, 31°08′E) near Mpulungu, Zambia at the southern tip of Lake Tanganyika in November 2010 using gill net (Table 1). The dorsal white muscles of fishes were excised and dried for stable isotope analyses. Periphyton samples were simultaneously collected from 10 territorial cichlid species. Each periphyton sample was collected from each territory of cichlid. We defined the territory as the place where the territory holder fed on periphyton and defended against conspecific and heterospecific herbivores [27]. Whether a site was located within or outside of a cichlid fish territory was determined by 20 min of observation immediately prior to sampling. Periphyton samples were dried for stable isotope analysis.

Stable isotope analysis

The stable isotope ratio of nitrogen (N) is useful in trophic level analysis as the nitrogen pools of animals have δ15N signatures regularly enriched by a certain value (typically, 3.4‰) relative to their food sources [28]. Stable isotope ratios of carbon (C) differ strongly among terrestrial plants, phytoplankton, and benthic algae [29], and can be used as tracers of C pathways within food webs. Samples of fish muscles, benthic animals, detritus, and periphyton collected from cichlid territories were dried in an oven at 60°C for 24 h, and ground into fine powder. The fish and benthic animal samples were treated with 2:1 chloroform:methanol solution for 24 h to remove lipid [30]. The periphyton and detritus samples were treated with 1.0 N HCl for 24 h and then washed with distilled water twice to remove mineral carbon. These treated samples were dried in an oven at 60°C for 24 h, again. C and N stable isotope ratios (per mil) were measured using a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (SerCon, LTD., ANCA-SL). Stable isotopes were measured as a delta (δ) value in units of per thousand deviations from the standards (‰) and are calculated as δX = [(Rsample/Rstandard) − 1] × 103, where X is 15N or 13C, and R is the ratio of the heavy (15N or 13C) to the light (14N or 12C) isotope.

Statistical analysis for stable isotope data

We analyzed δ15N and δ13C values of fish muscles and periphyton within their feeding territories using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM). The category of ecomorph was included as a fixed factor, and cichlid species as a nested factor. GLMM was conducted by an R package, lmerTest 2.0-3. Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to compare mean differences between ecomorphs using the glht function in the multcomp package in R. The differences of δ15N and δ13C values of fish muscles and periphyton within their territories were analyzed using a generalized linear model (GLM) for each ecomorph using cichlid species as a fixed factor. GLM is conducted by glm function in R 3.0.2 [31]. Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to compare mean differences between species using the glht function in the multcomp package in R. To test the effect of depth on δ13C and δ15N of algal farms, GLMM was conducted with depth as a fixed factor and cichlid species as a random factor. A GLMM was also conducted to test the effect of C and N stable isotope ratios in periphyton and cichlid ecomorphs on the isotope ratios in the muscles of territorial cichlids. Species were included as a random factor.

Stable isotope mixing model

Probability distributions for the proportional contributions of the potential dietary sources to the diet of each cichlid species were determined using the Bayesian stable isotope mixing model (MixSIAR), using MixSIAR GUI 1.0 [32,33]. δ15N and δ13C of each cichlid species were used as mixture data, and the same values from periphyton within territories defended by each cichlid species and those of other benthic animals and detritus were used as source data, together with their C and N concentration values. Markov Chain Monte Carlo parameters were set as follows, chain length = 50,000, burn in = 25,000, thin = 25, number of chains = 3. Trace plots and the result of Gelman-Rubin, Heidelberger-Welch, and Geweke diagnostic tests were used to confirm that the model had converged [33]. Discrimination values for δ15N and δ13C were provided as 3.4 ± 1.5‰ and 0.9 ± 1.1‰ [average ± standard deviation (SD)], respectively following Cabana and Rasmussen [28] and Harvey et al. [34], but SD of δ15N was enlarged because the discrimination value of δ15N can be larger in herbivorous fishes [35,36].

Results and discussion

Difference in C and N stable isotope ratios among ecomorphs

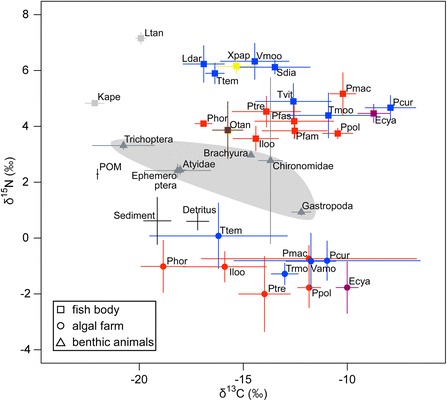

δ13C and δ15N stable isotope ratios of herbivorous cichlid muscles and periphyton within their algal farms varied widely as shown in Figure 1. As a result of GLMMs, both δ13C and δ15N values of cichlid muscles were significantly different among feeding ecomorphs (Table 2). The muscle δ15N was significantly lower in grazer than browsers, although δ15N values of periphyton within territories were not different among territorial species (Tables 2 and 3), suggesting that grazers depend more directly on primary production of periphyton, while others ingest animals with higher trophic level. This result agrees with the observations in previous studies. Previous studies show that grazers comb unicellular algae and cyanobacteria from the epiphytic assemblages using brush-like jaws [11,12,37], and animals were rarely found in their stomachs [7,10,38]. On the other hand, browsers nip and nibble filamentous algae and cyanobacteria using their nail clipper-like jaws [8,16,37], and Telmatochromis temporalis, Limnotilapia dardennii, and Simochromis diagramma ingest ephemeropteran and dipteran larvae, and fish fry [7,10,38]. Xenotilapia papilio, a scooper, had a relatively high value of δ15N (Figure 1), partly as this fish intakes and filters sand to capture diptera and copepoda, as well as algae and cyanobacteria within sand [14,38].

Figure 1.

δ13C-δ15N map for herbivorous cichlids, periphytons inside their algal farms, and other potential dietary items such as benthic animals, detritus, sediment, and particulate organic matter (POM). Abbreviations of cichlid species are shown in Table 1. Square, circle, and triangle indicate samples of fish muscles, periphyton collected from each cichlid territory, and benthic animals, respectively. Red, blue, purple, and plots indicate each ecomorph, grazer, browser, and scraper respectively. Plots of benthic animals are enclosed in a grey shadow. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Table 2.

Results of generalized linear mixed-model analyses to test the effect of cichlid ecomorphs on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of their muscles

| δ 13 C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecomorph | Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p |

| Intercept (biter) | −15.75 | 2.69 | 13.0 | −5.86 | <0.001 |

| browser | 2.51 | 2.87 | 13.0 | 0.88 | NS |

| grazer | 2.76 | 2.87 | 13.0 | 0.96 | NS |

| plankton eater | −5.29 | 3.29 | 13.0 | −1.61 | NS |

| scooper | 0.42 | 3.80 | 13.0 | 0.11 | NS |

| scraper | 7.02 | 3.80 | 13.0 | 1.85 | NS |

| Post-hoc test | Estimate | SE | z value | p | |

| browser-biter | 2.51 | 2.87 | 0.88 | NS | |

| grazer-biter | 2.76 | 2.87 | 0.96 | NS | |

| plankton eater-biter | −5.29 | 3.29 | −1.61 | NS | |

| scooper-biter | 0.42 | 3.80 | 0.11 | NS | |

| scraper-biter | 7.02 | 3.80 | 1.85 | NS | |

| grazer-browser | 0.25 | 1.44 | 0.17 | NS | |

| plankton eater-browser | −7.80 | 2.15 | −3.62 | <0.01 | |

| scooper-browser | −2.10 | 2.87 | −0.73 | NS | |

| scraper-browser | 4.50 | 2.87 | 1.57 | NS | |

| plankton eater-grazer | −8.05 | 2.15 | −3.74 | <0.01 | |

| scooper-grazer | −2.34 | 2.87 | −0.82 | NS | |

| scraper-grazer | 4.26 | 2.87 | 1.48 | NS | |

| scooper-plankton eater | 5.70 | 3.29 | 1.73 | NS | |

| scraper-plankton eater | 12.30 | 3.29 | 3.74 | <0.01 | |

| scraper-scooper | 6.60 | 3.80 | 1.74 | NS | |

| δ 15 N | |||||

| Ecomorph | Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p |

| Intercept (biter) | 3.87 | 0.81 | 13.0 | 4.77 | <0.001 |

| browser | 1.64 | 0.87 | 13.0 | 1.89 | NS |

| grazer | 0.30 | 0.87 | 13.0 | 0.34 | NS |

| plankton eater | 2.13 | 0.99 | 13.0 | 2.14 | NS |

| scooper | 2.29 | 1.15 | 13.0 | 2.00 | NS |

| scraper | 0.60 | 1.15 | 13.0 | 0.52 | NS |

| Post-hoc test | Estimate | SE | z value | p | |

| browser-biter | 1.64 | 0.87 | 1.89 | NS | |

| grazer-biter | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.34 | NS | |

| plankton eater-biter | 2.13 | 0.99 | 2.14 | NS | |

| scooper-biter | 2.29 | 1.15 | 2.00 | NS | |

| scraper-biter | 0.60 | 1.15 | 0.52 | NS | |

| grazer-browser | −1.34 | 0.43 | −3.10 | <0.05 | |

| plankton eater-browser | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.75 | NS | |

| scooper-browser | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.75 | NS | |

| scraper-browser | −1.04 | 0.87 | −1.20 | NS | |

| plankton eater-grazer | 1.83 | 0.65 | 2.82 | <0.05 | |

| scooper-grazer | 1.99 | 0.87 | 2.30 | NS | |

| scraper-grazer | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.35 | NS | |

| scooper-plankton eater | 0.16 | 0.99 | 0.16 | NS | |

| scraper-plankton eater | −1.53 | 0.99 | −1.54 | NS | |

| scraper-scooper | −1.69 | 1.15 | −1.47 | NS |

Species are included as a nested factor of ecomorph. SE, standard error; DF, degree of freedom; NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Results of the generalized linear mixed-model analysis for testing the effect of cichlid ecomorph on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of periphyton within their territories

| δ 13 C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecomorph | Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p |

| Intercept (browser) | −13.17 | 1.20 | 6.4 | −10.98 | <0.001 |

| grazer | −1.24 | 1.61 | 6.4 | −0.77 | NS |

| scraper | 3.12 | 2.63 | 5.9 | 1.19 | NS |

| Post-hoc test | Estimate | SE | z value | p | |

| grazer-browser | −1.24 | 1.61 | −0.77 | NS | |

| scraper-browser | 3.12 | 2.63 | 1.19 | NS | |

| scraper-grazer | 4.36 | 2.57 | 1.69 | NS | |

| δ 15 N | |||||

| Ecomorph | Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p |

| Intercept (browser) | −0.81 | 0.30 | 7.0 | −2.70 | <0.05 |

| grazer | −0.57 | 0.41 | 7.2 | −1.41 | NS |

| scraper | −1.17 | 0.65 | 6.1 | −1.80 | NS |

| Post-hoc test | Estimate | SE | z value | p | |

| grazer-browser | −0.57 | 0.41 | −1.41 | NS | |

| scraper-browser | −1.17 | 0.65 | −1.80 | NS | |

| scraper-grazer | −0.59 | 0.64 | −0.93 | NS |

Species are included as a nested factor of ecomorph. SE, standard error; DF, degree of freedom; NS, not significant.

With regard to δ13C, plankton eaters (Limnothrissa miodon and Stolothrissa tanganicae) had significantly lower values, suggesting that these fishes depend on phytoplankton as a carbon source as δ13C of phytoplankton is known to be lower than that of benthic algae [29]. On the other hand, no significant difference was found in δ13C among the other ecomorphs, suggesting that all of the herbivorous cichlids depend on periphyton as carbon source.

Difference among species within ecomorphs

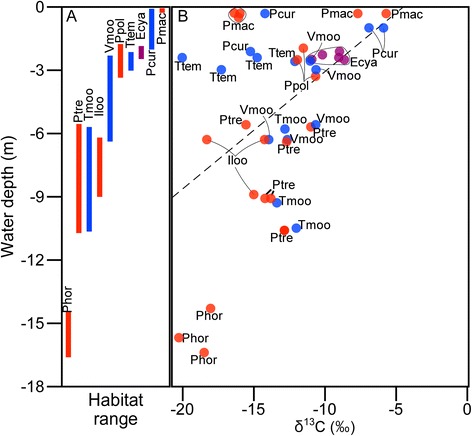

In both browsers and grazers, muscle δ15N and δ13C differed significantly among species (Table 4). Muscle δ13C of L. dardennii and T. temporalis were significantly smaller than that of the other browsers, δ13C of Petrochromis horii was smallest, and that of Interochromis loocki, and P. trewavasae were intermediate, and the values of other grazers were significantly higher (Table 4). Although δ13C of their algal farms were not significantly varied between species in grazers (Table 5), significant positive correlation was shown between δ13C of periphyton and the depth those samples were collected (Figure 2, Table 6). This tendency is due partly to the fact that relative content of δ13C of algae and cyanobacteria increases when growth rate/photosynthesis activity becomes higher, and when available aqueous CO2 decreases [39]. These herbivorous cichlids segregate their habitat depth by species in a-few-meter scale (Figure 2, [5-7,16]), and differences in habitat depth cause differences in δ13C of periphyton within cichlid territories.

Table 4.

Results of generalized linear models for testing the effect of cichlid species of each ecomorph on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of their muscles

| δ13 C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| browser | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Ldar) | −16.9 | 0.7 | −25.3 | <0.001 | |

| Pcur | 9.0 | 0.9 | 9.5 | <0.001 | |

| Sdia | 3.4 | 0.9 | 3.6 | <0.01 | |

| Tmoo | 6.0 | 0.9 | 6.3 | <0.001 | |

| Ttem | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | NS | |

| Tvit | 4.3 | 0.9 | 4.6 | <0.001 | |

| Vmoo | 2.5 | 0.9 | 2.6 | <0.05 | |

| grazer | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Iloo) | −14.4 | 0.6 | −25.2 | <0.001 | |

| Pfam | 1.9 | 0.8 | 2.3 | <0.05 | |

| Pfas | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.3 | <0.05 | |

| Pmac | 4.2 | 0.8 | 5.2 | <0.001 | |

| Ppol | 3.9 | 0.8 | 4.9 | <0.001 | |

| Phor | −2.5 | 0.9 | −2.9 | <0.01 | |

| Ptre | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | NS | |

| δ15 N | |||||

| browser | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Ldar) | 6.2 | 0.3 | 24.3 | <0.001 | |

| Pcur | −1.6 | 0.4 | −4.3 | <0.001 | |

| Sdia | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.3 | NS | |

| Tmoo | −1.8 | 0.4 | −5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Ttem | −0.3 | 0.4 | −0.9 | NS | |

| Tvit | −1.3 | 0.4 | −3.7 | <0.001 | |

| Vmoo | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | NS | |

| grazer | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Iloo) | 3.6 | 0.2 | 16.5 | <0.001 | |

| Pfam | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | NS | |

| Pfas | 0.6 | 0.3 | 2.0 | NS | |

| Pmac | 1.6 | 0.3 | 5.3 | <0.001 | |

| Ppol | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | NS | |

| Phor | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.7 | NS | |

| Ptre | 1.0 | 0.3 | 3.2 | <0.01 |

SE, standard error; NS, not significant.

Table 5.

Results of generalized linear models for testing the effect of herbivorous cichlid species of each ecomorph on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of periphyton within their territories

| δ 13 C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| browser | |||||

| Species | Estimate | SE | t value | p | |

| Intercept (Pcur) | −11.6 | 1.3 | −9.1 | <0.001 | |

| Tmoo | −1.4 | 2.1 | −0.7 | NS | |

| Ttem | −4.5 | 1.9 | −2.3 | <0.05 | |

| Vmoo | −0.5 | 1.8 | −0.3 | NS | |

| grazer | |||||

| Species | Estimate | SE | t value | p | |

| Intercept (Iloo) | −15.9 | 1.6 | −10.2 | <0.001 | |

| Pmac | 3.2 | 2.0 | 1.6 | NS | |

| Ppol | 4.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | NS | |

| Phor | −2.9 | 2.2 | −1.3 | NS | |

| Ptre | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | NS | |

| δ 15 N | |||||

| browser | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Pcur) | −1.0 | 0.4 | −2.3 | <0.05 | |

| Tmoo | −0.3 | 0.7 | −0.5 | NS | |

| Ttem | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.7 | NS | |

| Vmoo | −0.1 | 0.6 | −0.2 | NS | |

| grazer | |||||

| Estimate | SE | t value | p | ||

| Intercept (Iloo) | −1.0 | 0.5 | −2.0 | NS | |

| Pmac | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | NS | |

| Ppol | −0.7 | 0.7 | −1.1 | NS | |

| Phor | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | NS | |

| Ptre | −1.1 | 0.7 | −1.7 | NS |

SE, standard error; DF, degree of freedom; NS, not significant.

Figure 2.

Habitat depth of each cichlid species (A) and relation between habitat depth and δ13C of periphyton (B). Dotted line in B indicates the fitted line. Red, blue, and purple colors indicate cichlid ecomorph, grazer, browser, and scraper, respectively.

Table 6.

Results of the generalized linear mixed-model analysis testing the effect of habitat depth on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios of algal farms

| Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C | |||||

| (Intercept) | −11.64 | 0.88 | 8.7 | −13.19 | <0.001 |

| depth | 0.35 | 0.13 | 12.2 | −2.69 | <0.05 |

| δ15N | |||||

| (Intercept) | −1.06 | 0.32 | 9.3 | −3.30 | <0.01 |

| depth | 0.03 | 0.05 | 12.8 | −0.65 | NS |

Cichlid species was analyzed as a random factor. SE, standard error; DF, degree of freedom; NS, not significant.

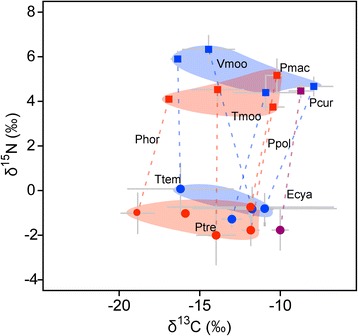

δ13C values in muscles of territorial cichlids were also significantly affected by δ13C value of the periphyton within their territories, irrespective of ecomorph, although δ15N of muscles was not related to that of periphyton (Figure 3, Table 7). This correlation in δ13C suggests that these herbivorous cichlids depend on the primary production of the periphyton within their territories, especially for their carbon sources.

Figure 3.

δ13C-δ15N map for herbivorous cichlids (square plots) and their algal farms (circle plots). The same species pair is connected by a broken line. Abbreviations of cichlid species are shown in Table 1. Red, blue, and purple plots indicate each ecomorph, grazer, browser, and scraper, respectively. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Table 7.

Results of generalized linear mixed model for testing the effect of δ13 C/δ15 N in the periphyton within territories and the effect of fish ecomorph on δ13 C/δ15 N of cichlid muscles

| Estimate | SE | DF | t value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C | |||||

| (Intercept) | 1.7 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 0.4 | NS |

| δ13C in periphyton | 1.1 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 3.0 | <0.05 |

| grazer in ecomorph | 0.6 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 0.4 | NS |

| scraper in ecomorph | 0.3 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 0.1 | NS |

| δ15N | |||||

| (Intercept) | 5.8 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 10.0 | <0.001 |

| δ15N in periphyton | 0.5 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 1.0 | NS |

| grazer in ecomorph | −0.6 | 0.6 | 5.0 | −0.9 | NS |

| scraper in ecomorph | −0.2 | 1.1 | 5.0 | −0.2 | NS |

Fish species are included as a random factor. SE, standard error; DF, degree of freedom.

Difference in δ15N implies the difference in intake of animal matters. δ15N of Pseudosimochromis curvifrons, Simochromis diagramma, Tropheus moorii, and Telmatochromis vittatus were significantly smaller than that of L. dardennii (Table 4), δ15N of Petrochromis trewavasae and P. polydon were higher than that of I. loocki. L. dardennii ingest detritus in addition to algae and cyanobacteria [10], and detritus appears to enrich δ15N in this cichlid by its higher δ15N value compared to periphyton (Figure 1). It should also be noted that Yamaoka et al. [40] suggests that I. loocki is a strict herbivore.

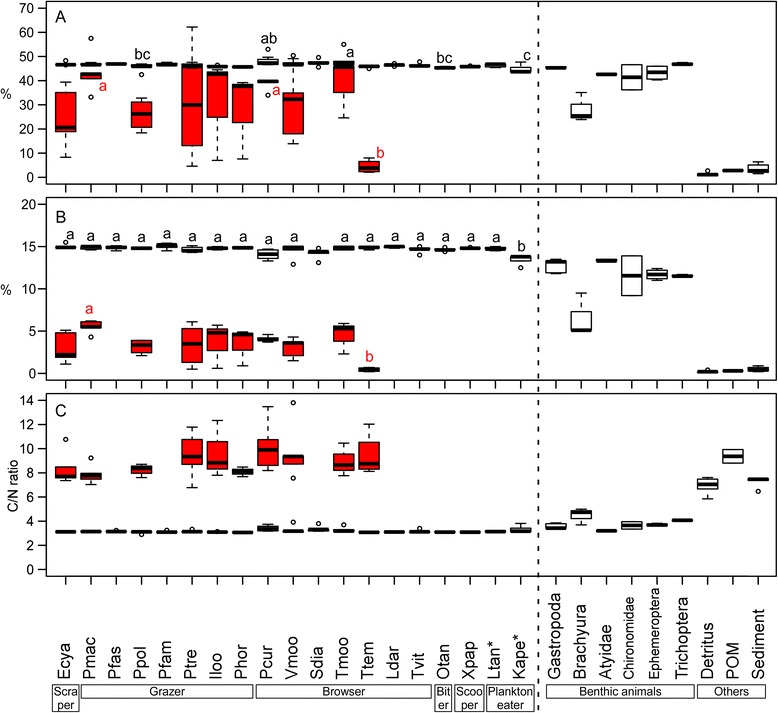

Differences in C and N stable isotope ratios between fish muscles and periphyton within their defending algal farms

Fractions in δ15N between cichlid muscles and their algal farms were 5.9 ± 0.7‰ (average ± SD, n = 10 species) and were large differentials comparing to 3.4‰, which is the most cited value as a diet-tissue discrimination factor [41-44]. The results of our Bayesian mixed-model show that territorial herbivorous species depend mostly on periphyton and detritus within territories, both occupying 51.9–69.1% in total, except for T. temporalis and V. moorii that utilize more benthic animals (Table 8). δ15N of these cichlids were significantly higher, and δ13C were significantly smaller than those of other territorial and herbivorous cichlids (Additional file 1: Table S1). It is known, however, that the trophic-step fractionation in herbivorous fishes varies and some have relatively higher values (e.g., 4.8 ± 1.3‰ in herbivorous fishes on coral reefs) partly because of higher excretion rates in such fishes [35]. Dependency on periphyton by these cichlids may thus be an underestimate. In our system, nitrogen contents of periphytons and detritus were low (3.4 ± 1.9%, 0.2 ± 0.1%, respectively, average ± SD) and their C/N ratios were much higher (9.0 ± 1.7, 6.9 ± 0.7, respectively) than those of cichlid fishes (3.2 ± 0.2, Figure 4). Therefore, these herbivorous cichlids appear to require other nitrogen sources with high nitrogen contents and low C/N ratios, such as benthic animals, to meet their nitrogen demand. These nitrogen supplies from animal matters may partly cause the enrichment of δ15N in these herbivorous cichlids [45].

Table 8.

Predicted diet proportion of herbivorous cichlids in Lake Tanganyika from a Bayesian mixing model with δ13 C and δ15 N of each cichlid species as mixture data, those of periphyton within their territories and those of other benthic animals as source data

| cichlid species | periphyton within each territory | detritus | Atyidae/Ephemeroptera | Trichoptera | Chironomidae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eretmodus cyanostictus | 43.5 ± 20.7 | 24.2 ± 17.8 | 8.2 ± 10.1 | 7.5 ± 9.2 | 16.6 ± 13.7 |

| Telmatochromis temporalis | 14.6 ± 12.1 | 25.2 ± 16.9 | 31.3 ± 17.0 | 14.1 ± 11.7 | 14.8 ± 11.0 |

| Variabilichromis moorii | 22.0 ± 15.1 | 21.2 ± 16.5 | 20.7 ± 15.5 | 15.8 ± 13.2 | 20.2 ± 14.9 |

| Pseudosimochromis curvifrons | 44.0 ± 16.7 | 25.1 ± 17.2 | 10.8 ± 9.8 | 7.7 ± 7.7 | 12.5 ± 11.8 |

| Petrochromis macrognathus | 34.3 ± 15.2 | 26.6 ± 18.5 | 11.9 ± 10.4 | 9.2 ± 9.1 | 18.0 ± 14.1 |

| Petrochromis polyodon | 46.6 ± 21.9 | 22.2 ± 16.4 | 8.3 ± 10.5 | 7.3 ± 10.2 | 15.7 ± 13.7 |

| Petrochromis horii | 23.3 ± 15.0 | 28.9 ± 17.7 | 21.0 ± 15.3 | 14.6 ± 12.5 | 12.2 ± 11.6 |

| Petrochromis trewavasae | 29.5 ± 18.0 | 22.4 ± 16.9 | 16.5 ± 13.4 | 11.7 ± 11.6 | 20.0 ± 15.9 |

| Tropheus moorii | 33.0 ± 19.6 | 21.2 ± 16.4 | 15.0 ± 13.9 | 11.6 ± 12.1 | 19.2 ± 15.8 |

Analyses were conducted by MixSIAR. δ13C and δ15N of Atyidae and Ephemeroptera are quite similar (as shown in Figure 1) and cannot be distinguished. The dominant dietary items are shown in bold.

Figure 4.

Box plots of carbon (A) and nitrogen (B) contents, C/N ratio (C) of fish muscles, periphyton within their territories, benthic animals, detritus, sediments, and particulate organic matter (POM) in water column. Red boxes and red letters indicate values and statistical result of periphyton. Shared letters on boxes indicate no significant differences, and pairs that do not share any letters in common were significantly different by the Tukey’s post hoc test between fish species. Species abbreviations are shown in Table 1. *denotes non-cichlid fish.

In this study, all samples for stable isotope analyses were collected a single time. It has been suggested that most primary producers have temporal variation in δ15N and δ13C because of the variation in their photosynthesis rate and in the availability of nutrients [43,46], and high temporal shifts in δ13C and δ15N in pelagic phytoplankton is also indicated in Lake Tanganyika [47]. δ13C and δ15N of herbivorous cichlids are time-integrated values reflecting their diet for a few months, and therefore, direct comparison of these values between cichlids and periphyton may have some shortcomings. This may cause the large gap in δ15N between herbivorous cichlids and periphyton within their territories. On the other hand, significant relation in δ13C between territorial cichlids and periphyton within their territories were observed. This indicate that the depth segregation among cichlids is stable as partly shown in Takeuchi et al. [5], and variation in δ13C along depth is relatively high comparing to the temporal variation. Further time-series sampling and analyses of periphyton and cichlid fishes will reveal the detailed habitat segregation throughout years.

Effect of the depth segregation on cichlid diversification

Specialization at a specific depth may enhance diversification. In Lake Victoria, light environments are different by depth and cichlid species have adapted and differentiated their vision. The adapted visions are associated with the male nuptial colorations, and have led to speciation and diversification of species [48]. Further, repeated lake-level fluctuation is thought to drive diversification of Tanganyikan cichlid through the repetitive shrink and expansion of habitats [49]. One Tanganyikan cichlid, Telmatochromis temporalis, has diversified into two genetically-distinct ecomorphs: a large-bodied rock-living ecomorph, and a small-bodied shell-living ecomorph [50,51]. This diversification occurred repeatedly in places where rocky habitat and shell beds are adjacent. Therefore, a variant that mature in small size in original population in the rocky habitat is thought to have shifted to the shell bed when the shell bed became a suitable depth as a result of lake-level changes [51]. In this way, under stenotopic constraints for specific depths and substrata, each population undergoes local selection, and gene flow between populations living in different environments can be restricted. Further, when habitats are separated, ancestral species may be diversified into different environments and sufficiently specialized not to mix with each other after their habitats are reunified and these populations re-encounter each other.

Conclusions

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios revealed the material flows from primary producers to herbivorous cichlids that inhabit various depths on a rocky littoral area of Lake Tanganyika. Carbon stable isotope value of primary producers was significantly correlated with the water depth at which the periphyton was collected. In the cichlids, both territorial grazers and browsers, carbon and nitrogen stable isotope values were significantly different among species, and this was caused by their habitat depth segregation. In this way, we show that multiple species of the same ecomorph living sympatrically on a rocky shore segregate not only by habitat depth but also by feeding depth. This specialization on specific depth may drive speciation and diversification, and prevent close relatives being mixed during water level fluctuations of the lake.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to three anonymous referees for improving the manuscript. We are also grateful to members of the Maneno Team (Tanganyika Research Project Team) and staff of LTRU, Mpulungu, Zambia, for their support. This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B, nos 22770024, 25840159) for HH, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B, no. 22405010) for MK. The research presented here was conducted under permission of fish research in Lake Tanganyika from the Zambian Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Fisheries and complied with the current law in Zambia.

Abbreviations

- C

Carbon

- DF

Degree of freedom

- GLM

Generalized linear model

- GLMM

Generalized linear mixed model

- N

Nitrogen

- NS

Not significant

- POM

Particulate organic matter

- SD

Standard deviation

- SE

Standard error

Additional file

Result of Tukey’s post-hoc test of multiple comparison between cichlid species of each ecomorph on carbon and stable isotope ratios of their muscles. Table S2. Result of Tukey’s post-hoc test of multiple comparison between cichlid species of each ecomorph on carbon and stable isotope ratios of periphytons within their territories.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HH, MK, MH participated in the design of the study. MH, MK arranged the permission and condition of field research. HH, HM conducted field research. JS, KO, HH carried out the stable isotope analysis. HH, JS analyzed data. HH wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Hiroki Hata, Email: hata@sci.ehime-u.ac.jp.

Jyunya Shibata, Email: jshiba@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

Koji Omori, Email: omori.koji.mj@ehime-u.ac.jp.

Masanori Kohda, Email: maskohda@sci.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Michio Hori, Email: hori@terra.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Salzburger W, Meyer A, Baric S, Verheyen E, Sturmbauer C. Phylogeny of the Lake Tanganyika cichlid species flock and its relationship to the Central and East African haplochromine cichlid fish faunas. Syst Biol. 2002;51:113–135. doi: 10.1080/106351502753475907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salzburger W, Mack T, Verheyen E, Meyer A. Out of Tanganyika: Genesis, explosive speciation, key-innovations and phylogeography of the haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danley PD, Husemann M, Ding B, Dipietro LM, Beverly EJ, Peppe DJ. The impact of the geologic history and paleoclimate on the diversification of East African cichlids. Int J Evol Biol. 2012;2012:574851. doi: 10.1155/2012/574851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muschick M, Indermaur A, Salzburger W. Convergent evolution within an adaptive radiation of cichlid fishes. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2362–2368. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi Y, Ochi H, Kohda M, Sinyinza D, Hori M. A 20-year census of a rocky littoral fish community in Lake Tanganyika. Ecol Freshw Fish. 2010;19:239–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0633.2010.00408.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hata H, Tanabe AS, Yamamoto S, Toju H, Kohda M, Hori M. Diet disparity among sympatric herbivorous cichlids in the same ecomorphs in Lake Tanganyika: amplicon pyrosequences on algal farms and stomach contents. BMC Biol. 2014;12:90. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takamura K. Interspecific relationships of aufwuchs-eating fishes in Lake Tanganyika. Environ Biol Fishes. 1984;10:225–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00001476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbomba NB. Comparative morphology of the feeding apparatus in cichlidian algal feeders of Lake Tanganyika. Afr Stud Monogr. 1983;3:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mbomba NB. Comparative feeding ecology of aufwuchs eating cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika with reference to their developmental changes. Physiol Ecol Japan. 1986;23:79–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori M, Gashagaza MM, Nshombo M, Kawanabe H. Littoral fish communities in Lake Tanganyika: irreplaceable diversity supported by intricate interactions among species. Conserv Biol. 1993;7:657–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07030657.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaoka K. Morphology and feeding behaviour of five species of genus Petrochromis (Teleostei, Cichlidae) Physiol Ecol Japan. 1982;19:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaoka K. Comparative osteology of the jaw of algal-feeding cichlids (Pisces, Teleostei) from Lake Tanganyika. Rep USA Mar Bio Inst Kochi Univ. 1987;9:87–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brichard P. Pierre Brichard’s book of cichlids and all the other fishes of Lake Tanganyika. Neptune City, NJ: TFH Publications; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanagisawa Y. Parental care in a monogamous mouthbrooding cichlid Xenotilapia flavipinnis in Lake Tanganyika. Ichthyol Res. 1986;33:249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaoka K, Hori M, Kuratani S. Ecomorphology of feeding in “goby-like” cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika. Physiol Ecol Japan. 1986;23:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaoka K. Feeding behaviour and dental morphology of algae scraping cichlids (Pisces: Teleostei) in Lake Tanganyika. Afr Stud Monogr. 1983;4:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturmbauer C, Mark W, Dallinger R. Ecophysiology of aufwuchs-eating cichlids in Lake Tanganyika: niche separation by trophic specialization. Environ Biol Fishes. 1992;35:283–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00001895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner CE, McIntyre PB, Buels KS, Gilbert DM, Michel E. Diet predicts intestine length in Lake Tanganyika’s cichlid fishes. Funct Ecol. 2009;23:1122–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01589.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohda M. Coexistence of permanently territorial cichlids of the genus Petrochromis through male-mating attack. Environ Biol Fishes. 1998;52:231–242. doi: 10.1023/A:1007381217885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuwamura T. Overlapping territories of Psedosimochromis curvifrons males and other herbivorous cichlid fishes in Lake Tanganyika. Ecol Res. 1992;7:43–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02348596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecky RE, Hesslein RH. Contributions of benthic algae to lake food webs as revealed by stable isotope analysis. J N Am Benthol Soc. 1995;14:631–653. doi: 10.2307/1467546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doi H, Kikuchi E, Hino S, Itoh T, Takagi S, Shikano S. Seasonal dynamics of carbon stable isotope ratios of particulate organic matter and benthic diatoms in strongly acidic Lake Katanuma. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2003;33:87–94. doi: 10.3354/ame033087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishikawa N, Doi H, Finlay JC. Global meta-analysis for controlling factors on carbon stable isotope ratios of lotic periphyton. Oecologia. 2012;170:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menzel D. Utilization of algae for growth by the angelfish, Holacanthus bermudensis. ICES J Mar Sci. 1959;24:308–13.

- 25.Feller R, Taghon G, Gallagher E, Kenny G, Jumars P. Immunological methods for food web analysis in a soft-bottom benthic community. Mar Biol. 1979;54:61–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00387052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michener R, Schell D. Stable isotope ratios as tracers in marine aquatic food webs. In: Lajtha K, Michener R, editors. Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science. Oxford: Blackwell; 1994. pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohda M. Intra- and interspecific territoriality of a temperate damselfish Eupomacentrus altus, (Teleostei: Pomacentridae) Physiol Ecol Japan. 1984;21:35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabana G, Rasmussen JB. Modelling food chain structure and contaminant bioaccumulation using stable nitrogen isotopes. Nature. 1994;372:255–257. doi: 10.1038/372255a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.France RL. Differentiation between littoral and pelagic food webs in lakes using stable carbon isotopes. Limnol Oceanogr. 1995;40:1310–1313. doi: 10.4319/lo.1995.40.7.1310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team: R: a language and environment for statistical computing. In. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013

- 32.Moore JW, Semmens BX. Incorporating uncertainty and prior information into stable isotope mixing models. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:470–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stock BC, Semmens BX: MixSIAR GUI User Manual, version 1.0. [http://conserver.iugo-cafe.org/user/brice.semmens/MixSIAR]

- 34.Harvey CJ, Hanson PC, Essington TE, Brown PB, Kitchell JF. Using bioenergetics models to predict stable isotope ratios in fishes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2002;59:115–124. doi: 10.1139/f01-203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mill AC, Pinnegar JK, Polunin NVC. Explaining isotope trophic-step fractionation: why herbivorous fish are different. Funct Ecol. 2007;21:1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis AM, Blanchette ML, Pusey BJ, Jardine TD, Pearson RG. Gut content and stable isotope analyses provide complementary understanding of ontogenetic dietary shifts and trophic relationships among fishes in a tropical river. Freshw Biol. 2012;57:2156–2172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2012.02858.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamura K. Interspecific relationship between two aufwuchs eaters Petrochromis polyodon and Tropheus moorei (Pisces: Cichlidae) of Lake Tanganyika, with a discussion on the evolution and functions of a symbiotic relationship. Physiol Ecol Japan. 1983;20:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hori M. Structure of littoral fish communities organized by their feeding activities. In: Kawanabe H, Hori M, Nagoshi M, editors. Fish Communities in Lake Tanganyika. Kyoto, Japan: Kyoto University Press; 1997. pp. 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goericke R, Montoya JP, Fry B. Physiology of isotopic fractionation in algae and cyanobacteria. In: Lajtha K, Michener RH, editors. Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaoka K, Hori M, Kuwamura T. Interochromis, a new genus of the Tanganyikan cichlid fish. S Afr J Sci. 1998;94:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minagawa M, Wada E. Stepwise enrichment of 15 N along food chains: Further evidence and the relation between δ15N and animal age. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48:1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(84)90204-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vander Zanden MJ, Rasmussen JB. Variation in δ15N and δ13C trophic fractionation: Implications for aquatic food web studies. Limnol Oceanogr. 2001;46:2061–2066. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.8.2061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Post DM. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology. 2002;83:703–718. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCutchan JH, Lewis WM, Kendall C, McGrath CC. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos. 2003;102:378–390. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12098.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hata H, Umezawa Y. Food habits of the farmer damselfish Stegastes nigricans inferred by stomach content, stable isotope, and fatty acid composition analyses. Ecol Res. 2011;26:809–818. doi: 10.1007/s11284-011-0840-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabana G, Rasmussen JB. Comparison of aquatic food chains using nitrogen isotopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10844–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.O’Reilly CM, Hecky RE, Cohen AS, Plisnier P-D. Interpreting stable isotopes in food webs: Recognizing the role of time averaging at different trophic levels. Limnol Oceanogr. 2002;47:306–309. doi: 10.4319/lo.2002.47.1.0306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seehausen O, Terai Y, Magalhaes IS, Carleton KL, Mrosso HDJ, Miyagi R, et al. Speciation through sensory drive in cichlid fish. Nature. 2008;455:620–626. doi: 10.1038/nature07285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sturmbauer C, Baric S, Salzburger W, Rüber L, Verheyen E. Lake level fluctuations synchronize genetic divergences of cichlid fishes in African lakes. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:144–154. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi T, Watanabe K, Munehara H, Ruber L, Hori M. Evidence for divergent natural selection of a Lake Tanganyika cichlid inferred from repeated radiations in body size. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:3110–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Winkelmann K, Genner MJ, Takahashi T, Rüber L. Competition-driven speciation in cichlid fish. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3412. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trewavas E. Tilapiine fishes of the genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. London: British Museum (Natural History); 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morley J, Balshine S. Faithful fish: territory and mate defence favour monogamy in an African cichlid fish. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2002;52:326–331. doi: 10.1007/s00265-002-0520-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morley J, Balshine S. Reproductive biology of Eretmodus cyanostictus, a cichlid fish from Lake Tanganyika. Environ Biol Fishes. 2003;66:169–179. doi: 10.1023/A:1023610905675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poll M. Poissons Cichlidae, vol. III (5B) Brussels, Belgium: Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochi H, Yanagisawa Y. Commensalism between cichlid fishes through differential tolerance of guarding parents toward intruders. J Fish Biol. 1998;52:985–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb00598.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karino K. Depth-related differences in territory size and defense in the herbivorous cichlid, Neolamprologus moorii, in Lake Tanganyika. Ichthyol Res. 1998;45:89–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02678579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ochi H, Takeyama T, Yanagisawa Y. Increased energy investment in testes following territory acquisition in a maternal mouthbrooding cichlid. Ichthyol Res. 2009;56:227–231. doi: 10.1007/s10228-008-0088-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kohda M, Takemon Y. Group foraging by the herbivorous cichlid fish, Petrochromis fasciolatus, in Lake Tanganyika. Ichthyol Res. 1996;43:55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02589608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamaoka K. A revision of the cichlid fish genus Petrochromis from Lake Tanganyika, with description of a new species. JPN J Ichthyol. 1983;30:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi T, Koblmüller S. A new species of Petrochromis (Perciformes: Cichlidae) from Lake Tanganyika. Ichthyol Res. 2014;61:252–64. doi: 10.1007/s10228-014-0396-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yanagisawa Y, Nishida M. The social and mating system of the maternal mouthbrooder Tropheus moorii (Cichlidae) in Lake Tanganyika. JPN J Ichthyol. 1991;38:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coulter GW. Pelagic fish. In: Coulter GW, editor. Lake Tanganyika and Its Life. London: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 111–138. [Google Scholar]