Abstract

β-Glucosidase is an important component of the cellulase complex. It not only hydrolyzes cellobiose and short-chain cellooligosaccharides to glucose, but also removes the inhibitory effect of cellobiose on the β-1, 4-endoglucanase and exoglucanase, thereby increasing the overall rate of cellulose biodegradation. β-glucosidasefrom culture supernatant of a fungus Penicillium simplicissimum was purified to homogeneity, by using ammonium sulfate fraction, Sephadex G-100 chromatography, and its properties were studied. The molecular mass of the enzyme was about 126.0 kDa, as identified by 12% SDS-PAGE. The optimum pH and temperature were 4.4 ~ 5.2 and 60 °C, respectively. The enzyme was stable in pH 5.2 ~ 6.4 and under 40 °C. Metal profile of the enzyme showed that Mn2+ enhances its activity, while Cu2+, Co2+and Fe3+ cause obvious inhibition. The Km and Vmax was 14.881 mg/ml and 0.364 mg ml/min against salicin as a Substrate. This enzyme had secondary protein structure as evidenced by FTIR spectrum.

Keywords: beta-glucosidase, Penicillium simplicissimum, purification, characterization

Introduction

Cellulases are a group of enzymes which consists of endoglucanase (EC 3.2.1.4), cellobiohydrolase (EC 3.2.1.91), and β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21) which are mostly used for hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomasses for ethanol production. Among these three enzymes, β-glucosidase is an important component of cellulase enzyme complex which is an essential for complete hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose. This enzyme induces cellulase enzyme system by the formation of sophorose and gentiobiose (Ramani et al., 2012[32]). This enzyme has a key attention to the scientists because most of the fungus lacks this enzyme such as Trichoderma reesie which is widely used in saccharification of lignocellulosic biomasses. Mostly the β-glucosidases from fungal sources are preferred over bacterial source due to ease in recovery process with high activity and are stable in wide range of pH and temperature (Lis and Sharon, 1993[26]).

β-Glucosidases are ubiquitous and can be found in bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. These are produced intracellular and extracellular in various organisms depending on the cultivation conditions. These enzymes can be classified on the basis of substrate activity and nucleotide sequence identity (Bhatia et al., 2002[5]; Henrissat and Davies, 1997[18]). Based on their substrate specificity, they are divided into three classes, class I which contain aryl β-glucosidases, class II contains true cellobiases and class III contains β-glucosidases having broad substrate specificity. Most of the β-glucosidases belongs to class III which can cleave β 1,4; β 1,6; β 1,2 and α 1,3; α 1,4; α 1,6 glycosidic bonds (Bhatia et al., 2002[5]; Riou et al., 1998[33]). Henrissat and Bairoch (1996[17]) stated that β-glucosidases are in family 1 and 3 from the 88 glycosyl hydrolase families. Family 1 contains β-glucosidases which are found in archeabacteria, plants and mammals and also exhibit β-glactosidase activity. Family 3 contains β-glucosidases which are produced from fungi, bacteria and plants having a characteristics two-domain structure (Varghese et al., 1997[36]).

β-Glucosidases are mostly used in cellulose conversion process but also have broad applications such as activation of phytohormones and defense against pathogens in plants (Esen, 1993[15]), cellular signaling and oncogenesis (Bhatia et al., 2002[5]), release of aroma from wine grapes and hydrolysis of bitter compounds during juice extraction, formation of alkyl- and aryl-glycosides by trans-glycosylation from natural polysaccharides or their derivatives and alcohols and also used in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and detergent industries (Bhat, 2000[4]; Gargouri et al., 2004[16]). There are a many reports about cellulases of genus Penicillium but still there is no report of cellulase (β-glucosidase) from Penicillium simplicissimum. This study was aimed to produce β-glucosidase from this fungus species and also purification and characterization with implementation on cellulose hydrolysis.

Experimental

Microorganism

A strain of Penicillium simplicissimum H-11 was obtained from Biological Engineering Research laboratory, Center of Life Science and Technology Harbin Institute of Technology Harbin, China. The strain was grown on PDA slants and used for β-glucosidase enzyme production.

Inoculum's development

Inoculum was developed by using the following medium (g/L)

(NH4)2SO4 3.0,

FeSO4·7H2O 0.005,

KH2PO4 1.0,

MnSO4·H2O 0.0016,

MgSO4·7H2O 0.5,

ZnSO4·7H2O 0.0017,

CaCl2 0.1,

CoCl2 0.002,

NaCl 0.1,

ball milled cellulose 20.

This medium was inoculated with spores of five days old Penicillium simplicissimum and incubated at 30 °C for three days of fermentation with agitation speed of 280 rpm. After the termination of the fermentation period, this culture broth was used as an inoculum source.

Enzyme production

Medium used for enzyme production comprised of (g/L)

wheat bran 18,

rice straw 13.5,

bean cake powder 4.5,

KH2PO4 0.4,

CaCl2·2H2O 0.03,

MgSO4·7H2O 0.03.

This medium was aseptically inoculated with culture of Penicillium simplicissimum. Fermentation was carried out in 20 L fermentation tank at 30 °C with agitation speed of 280 rpm for four days of fermentation period. After the end of the fermentation period, the fermentation broth was collected, filtered with gauze and centrifuged at 8000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. The cell free supernatant obtained after centrifugation was used as a source of crude β-glucosidase enzyme.

Assay of β-glucosidase

The enzyme activities were assayed using the method of Tomaz and Roche (2002[35]). The reaction mixture consisted 0.2 ml substrate (1% Salicin), 0.1 ml enzyme solution, and 0.1 ml citrate buffer (pH 4.8). The mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. The method of DNS was used to measure the change of sugar. One unit of the activity (U) was defined as the amount of the enzyme that liberated 1 µg sugar from the substrate per minute under standard assay conditions. Protein content was estimated by Bradford (1976[8]) method using BSA as a standard.

Purification of β-glucosidase

Ammonium sulphate precipitation

Cell free supernatant was precipitated by adding ammonium sulphate at different saturation levels (30-90 %). After each addition, the enzyme solution was stirred for 1 h at 4 °C. The protein precipitated was collected by centrifugation at 8000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C and resuspended in minimum volume of 0.05 M citrate buffer, pH 4.8. to get the concentrated enzyme suspension. After that the enzyme suspension was dialyzed against same buffer with 3-5 changes.

Sephadex G-100 gel filtration chromatography

The concentrated enzyme sample was purified on sephadex G-100 column (2 cm x 120 cm). The sephadex column was equilibrated with 0.05 M Citrate buffer, pH 4.8. The dialyzed enzyme sample was loaded on to sephadex G-100 column eluted with the same buffer. Fractions (each of 5 ml/tube) were collected at a flow rate of 30 ml/h by fraction collector. The fractions showing absorbance at 280 nm was analyzed for β-glucosidase activity and the active fractions were pooled dialyzed and then lyophilized. The lyophilized enzyme sample was stored at -20 °C for further studies.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE (12 %) was performed according to the method described by Laemmli (1970[25]) using a mini slab gel apparatus. The molecular weight was determined by interpolation from linear semi-logarithmic plot of relative molecular weight versus the Rf value (relative mobility) using standard molecular weight markers (low molecular weight markers, Pharmacia).

HPLC analysis of β-glucosidase

A Hypersil ODS column (4.6 mm × 100 mm) of High Performance Liquid Chromatography (Agilent 1100 Series) was used to test the enzyme purity. The 5μL sample volume was injected and separated using the solvent system of acetonitrile-water (70:30) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. A highly sensitive MWD UV detector was used to read the absorbance.

FTIR analysis of β-glucosidase

Mixture of sample and KBr (5 % sample, 95 % KBr) were passed into a disk for Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (Magna-IR 560 ESP, FTIR Nicolet Company USA) measurement (Irfan et al., 2011[19]). The spectra were recorded with 32 scans in the frequency range of 4000 - 400 cm-1with a resolution of 4 cm-1. Disks were prepared in triplicates to obtain a constant spectrum.

UV-absorption spectrum of β-glucosidase

Ultraviolet absorption spectrum of enzyme was recorded in aqueous solution with double beam spectrophotometer (VARIAN Cary 4000 UV-VIS spectrophotometer, USA) at ambient temperature (30 °C).

Characterization of enzyme

Effect of temperature on activity and stability of β-glucosidase

The effect of temperature on activity of β-glucosidase was determined by incubating crude enzyme mixture in 1% Salicin in 10 mM Citrate buffer (pH 5.0) at temperatures between 40 to 90 °C with regular interval of 5 °C. Enzyme activity was assayed by DNS method at different temperatures as described above. Thermostability studies of the enzyme were conducted by pre-incubating the enzyme solution at 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80 °C for 4 h. After this incubation the enzyme activity was checked by standard assay procedure.

Effect of pH on activity and stability of β-glucosidase

The optimum pH for the enzyme was determined by incubating enzyme with substrate (1% Salicin) prepared in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 2.8, 3.2, 3.6, 4.0, 4.4, 4.8, 5.2, 5.6, 6.0, 6.4 and 6.8). To check the stability at different pH, the enzyme was placed in different pH buffers at room temperature (30 °C) for 12 h. After that the enzyme activity was measured using standard assay procedure.

Effect of various metal ions on activity of β-glucosidase

Various metal ions including Sn2+, Cu2+, Li+, Zn2+, Co2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Fe3+and Mg2+ was applied to check the optimum activity of enzyme. Each metal ion was used at a concentration of 10 mM.

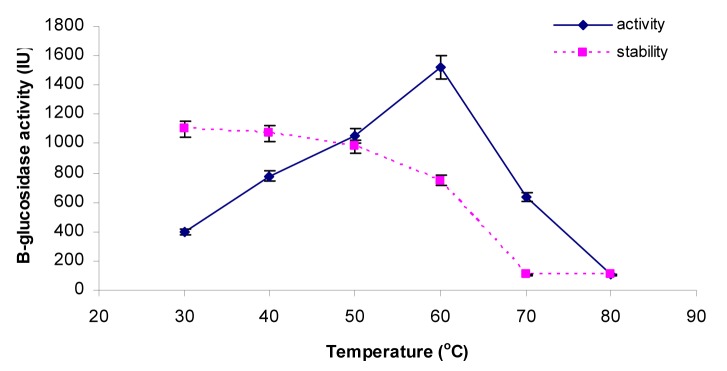

Substrate specificity

Effects of various substrates such as Xinghua filter paper, microcrystalline cellulose (1 %), xylan (1 %), CMC-Na (1 %), pNPG (1 %), pNPC (1 %), Chitin (1 %) and Salicin (0.5 %) on purified CMCase activity were determined. The β-glucosidase towards salicin was taken as control.

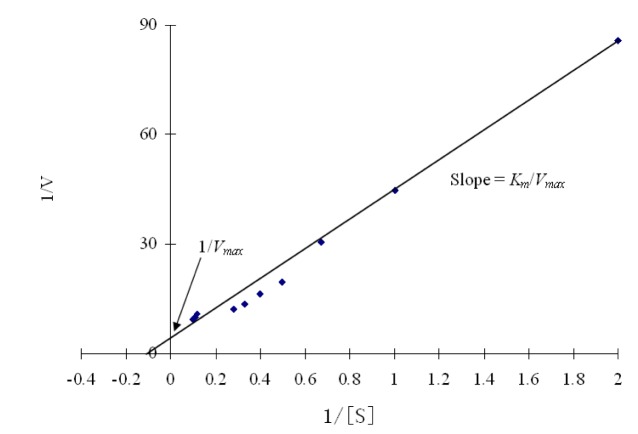

Enzyme kinetics

The Km and Vmax of β-glucosidase were calculated by linear regression analysis by Lineweaver-Burk plot (double reciprocal plot) using various concentration of Salicin (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45 and 50 mg/ml). The experiments were carried out in triplicates and then the activity measured according to the standard assay conditions.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

Hydrolysis of cellubiose was performed in 500 Erlenmeyer flask at 50 °C. One gram of cellubiose was dissolved in 100 ml of 0.05 M citrate buffer pH 5 and 0.5 g of β-glucosidase powder was also added and incubated at 50 °C for 1 h. After 1 h sample was taken and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography. 15 µL of sample was injected into carbohydrate column (4.6 × 250mm) using solvent system of acetonitrile water (75:25) with flow rate of 1.4 mL/min. RI detector (refractive index) was used for detection and each sample was operated in triplicates to obtain constant results.

Results and Discussion

Purification of β-glucosidase

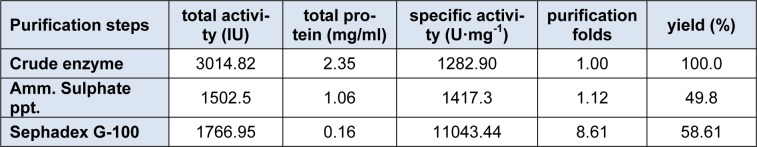

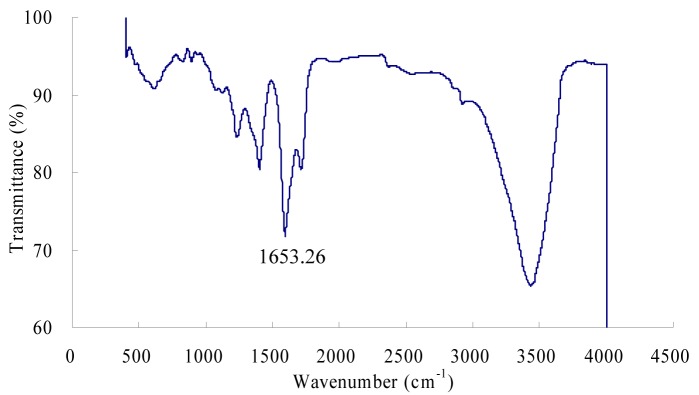

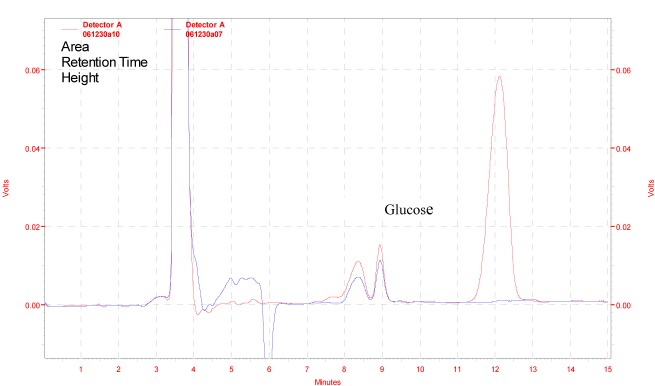

The enzyme β-glucosidase was produced from Penicillium simplicissimum by submerged fermentation at 30 °C for 72 h of fermentation period. Table 1(Tab. 1) summarizes the purification steps of β-glucosidase enzyme. The crude enzyme solution was fractionated with ammonium sulphate fractionation. After 80% ammonium sulphate saturation, the enzyme suspension was dialyzed using citrate buffer (pH 4.8) for 48 h at 4 °C. The dialyzed enzyme solution was loaded on to a sephadex G-100 column. The elution profile of the enzyme solution was shown in Figure 1(Fig. 1). The elution profile showed that there are two peaks, peak 1 and peak 2. Peak 1 exhibits the strong β-glucosidase activity as compared to the peak 2. This peak 1 yielded 58.61 % enzyme activity with purification fold of 8.61 having specific activity of 11043.44 U/mg.

Table 1. Purification profile of β-glucosidase from P. simplicissimum H11.

Figure 1. Sephadex G-100 elution profile of β-glucosidase.

The specific activity was improved from 1282.90 to 11043.44 U/mg. These results indicated that sephadex G-100 column chromatography yielded pure enzyme. So, the fractions of peak 1 was pooled and lyophilized for further use. Elshafei et al., (2011[14]) reported that both sephadex G-100 and sephadex G-200 were best for the purification of β-glucosidase enzyme from Aspergillus terreus NRRL 265. Chauve et al., (2010[10]) purified β-glucosidase enzyme from two fungal species with purity yield of 95 % and purification factor of 53 using anion exchange chromatography. In another study (Liu et al., 2012[27]) by using sephadex G-100, purification fold of 5.1 was obtained with recovery of 20 %.

Purity check of β-glucosidase

The enzyme solution obtained from sephadex G-100 column chromatography was converted into powder form by lyophilization. This enzyme preparation was further checked by SDS-PAGE to confirm the homogeneity. The results (Figure 2(Fig. 2)) indicated that SDS-PAGE showed a single band which confirms the homogeneous enzyme preparation. The molecular weight of the β-glucosidase enzyme was determined by plotting a graph between linear logarithms of relative molecular mass versus the Rf value. From this calculation it was found that the β-glucosidase exhibits the molecular mass of 126.0 kDa.

Figure 2. Purity check of β-glucosidase (a) SDS-PAGE and (b) HPLC chromatogram.

β-Glucosidase enzyme from Penicillium funiculosum NCL1, Penicillium purpurogenum KJS506 and Penicillium occitanis had molecular mass of 120 kDa, 89.6 kDa and 98 kDa respectively (Ramani et al., 2012[32]; Jeya et al., 2010[20]; Bhiri et al., 2008[7]). β-Glucosidase enzyme from A. terreus NRRL 265 exhibits molecular mass of 116 kDa (Elshafei et al., 2011[14]). To check the further purity of the β-glucosidase enzyme, the enzyme solution was loaded on to a Hypersil ODS column of High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Results (Figure 2(Fig. 2)) reveals that the enzyme showed a single peak at retention time of 1 min confirming that the enzyme solution was pure.

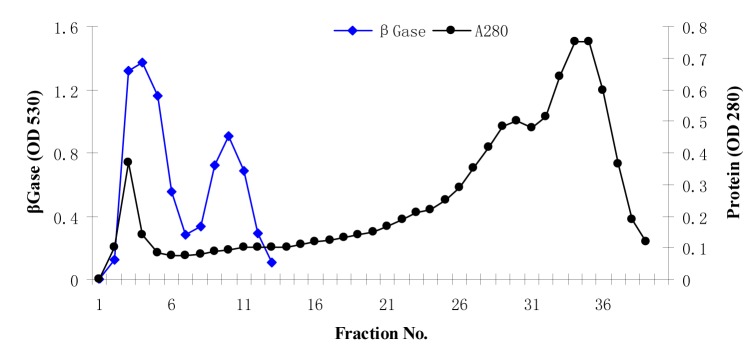

FTIR analysis of the β-glucosidase

The purified β-glucosidase enzyme was characterized by FTIR spectroscopy (Figure 3(Fig. 3)). The IR spectrum of the purified enzyme indicated that there are some peaks in 611.00 ~ 615.00 cm-1 regions which belong to the secondary amide of the amide V which is due to the out of plan NH bending (Elliot and Ambrose, 1950[13]). The peaks at 1240.00 cm-1 and 1400.00 cm-1 represents the secondary amide III bands and primary amide of the amide III bands which is CN stretching vibration and NH bending vibration respectively. β-Glucosidase enzyme had a strong absorption peak at 1653.26 cm-1, which is a characteristic peak of the α-helix, is caused by the symmetric stretching vibration of C = O stretching vibration and NH bond which is confirmed by many studies (Dong et al., 1992[12]; Susi and Byler, 1986[34]; Byler and Susi, 1986[9]). The bands between 1700 - 1600 cm−1 are considered to be the most sensitive regions for protein secondary structural components (amide I band) and these peaks are due to the C = O stretch vibrations of the peptide linkages (Kong and Yu, 2007[22]). The bands at 3100 cm-1 and 3300 cm-1 represents the amide B and amide A linkages which was due to the NH stretching (Elliot and Ambrose, 1950[13]; Krimm and Bandekar, 1986[23]; Banker 1992[1]; Miyazawa et al., 1956[29]).

Figure 3. FTIR spectrum of β-glucosidase enzyme.

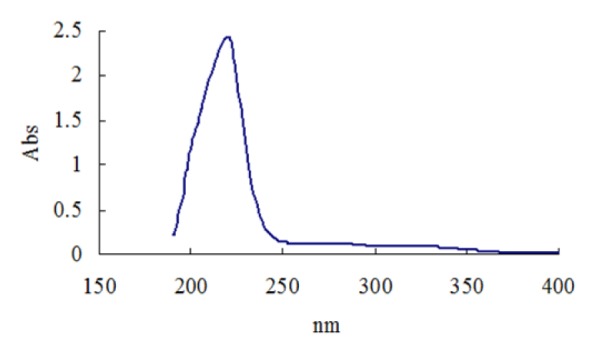

Ultraviolet absorption spectrum of ß-glucosidase

The purified ß-glucosidase enzyme solution was used for UV absorption spectrum by using buffer as control, the full band scan detection on a UV spectrometer. The results (Figure 4(Fig. 4)) indicated that β-glucosidase enzyme showed a maximum absorption peak at 219.0 nm indicating the presence of an aromatic side chain, especially the presence of tyrosine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, or their residues. The purified cellulase enzyme from Aspergillus oryzae ITTC-4857.01 exhibit maximum absorption peaks at 270 nm (Begum and Absar, 2009[3]) and 290 nm (Begum, 2005[2]) indicating some structural resemblance of the enzyme.

Figure 4. Ultraviolet absorption spectrum of β-glucosidase produced from Penicillium simplicissimum.

Characterization of β-Glucosidase

Effect of temperature on activity and stability

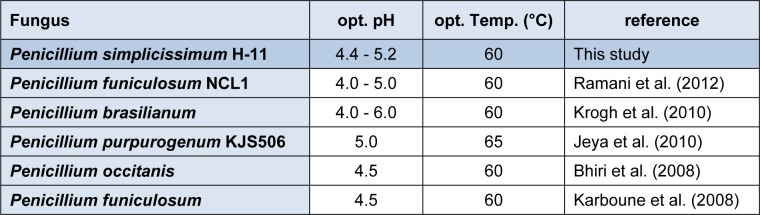

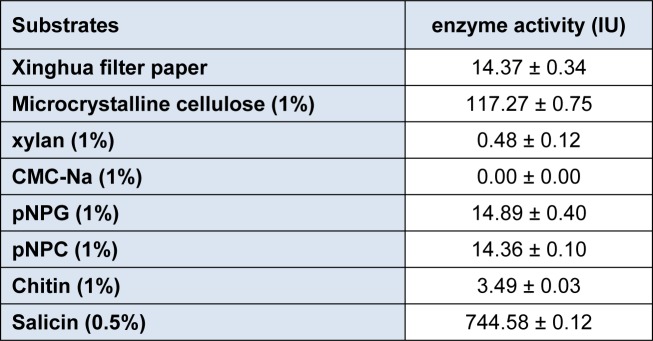

The activities of the β-glucosidase were assayed at various temperatures ranging from 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C and 80 °C to check the optimum temperature. Results (Figure 5(Fig. 5)) indicated that enzyme activity was increased with increase in temperature and peak activity was observed at 60 °C. After that, as the temperature was increased from 60 °C to 80 °C, there was a sharp decline in enzyme activity from 1523.0 ± 1.75 IU to 106.1 ± 0.70 IU respectively. Thermostability profile of the enzyme revealed that the β-glucosidase enzyme was stable at temperature up to 50 °C for 4 h of pre-incubation period. But higher temperature up to 80 °C causes denaturation of the enzyme. This thermostability of the enzyme at 50 °C for 4 h is very beneficial for enzymatic hydrolysis of the lignocellulosic biomasses. Our findings were similar to the others who also reported that most of the species of this genus Penicillium (Penicillium funiculosum NCL1, Penicillium brasilianum, Penicillium occitanis and Penicillium funiculosum) have optimum temperature of 60 °C (Ramani et al., 2012[32]; Krogh et al., 2010[24]; Bhiri et al., 2008[7]; Karboune et al., 2008[21]) while one species, Penicillium purpurogenum KJS506 exhibits optimum temperature of 65 °C (Jeya et al., 2010[20]) respectively. In a recent report (Bhatti et al., 2013[6]) β-glucosidase enzyme from Fusarium saloni had optimum temperature and thermostability at 65 °C.

Figure 5. Effect of temperature on β-glucosidase activity and stability.

Effect of pH on activity and stability

The activity of the enzyme was assayed using citrate buffer at various pH (2.8, 3.2, 3.6, 4.0, 4.4, 4.8, 5.2, 5.6, 6.0, 6.4 and 6.8) at 50 °C for 30 min. The result (Figure 6(Fig. 6)) indicated that the optimum pH of β-glucosidase was about from 4.4 to 5.2. Further increase or decrease of pH beyond these resulted decline in enzyme activity. To check the pH stability of the enzyme, the enzyme solution was pre-incubated at various pH for 12h at room temperature (i.e. 30 °C). The enzyme was stable in pH range of 4 to 6.8. β-Glucosidases from various species of Penicillium have optimum pH range of 4.0 - 6.0 (Ramani et al., 2012[32]; Krogh et al., 2010[24]; Jeya et al., 2010[20]; Bhiri et al., 2008[7]; Karboune et al., 2008[21]). β-Glucosidase enzyme from Penicillium funiculosum was stable in pH range of 2.5 - 6.0 retaining 80 % of the activity after 2 h incubation at 25 °C (Karboune et al., 2008[21]). In another report (Bhiri et al., 2008[7]) β-glucosidase enzyme from Penicillium occitanis was stable in pH range from 3 to 9 after 24 h incubation at 4 °C. Table 2(Tab. 2) also compares the optimum pH of various species of the genus Penicillium. So, these findings indicated that the β-Glucosidase enzyme from Penicillium species exhibits a wide range of pH stability.

Figure 6. Effect of pH on β-glucosidase activity and stability.

Table 2. Comparison of optimum pH and temperature of some species of genus Penicillium.

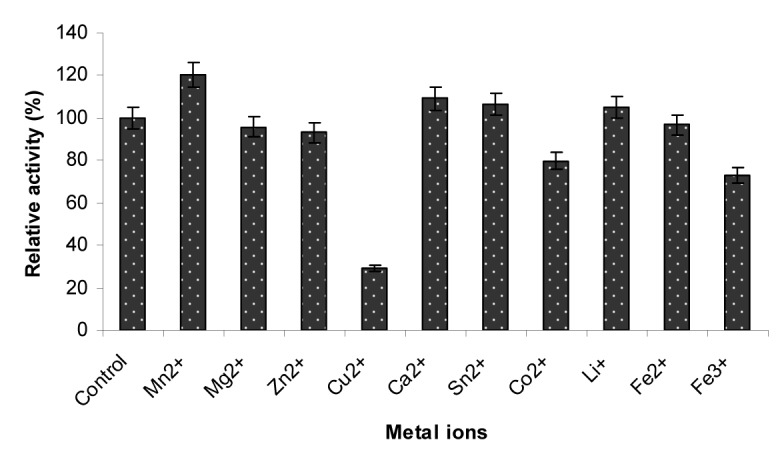

Effect of different metal ion

To check the effect of metal ions (10 mmol/L) the enzyme was treated with different metals for 30 min at 50 °C. After that the enzyme activity was determined using standard procedure. The results (Figure 7(Fig. 7)) showed that Mn2+ (120.46 %), Ca2+ (109.14 %), Sn2+ (106.50) and Li+ (104.91) were the activators while Cu2+ (29.08 %) and Fe2+ (73.05) were the inhibitors of the β-glucosidase enzyme respectively (Table 3(Tab. 3)). Our findings were mostly in accordance with other studies. β-glucosidases of other fungal species were strongly activated by Zn2+ (Ramani et al., 2012[32]), Mn,2+ Mg2+ (Chen et al., 2012[11]), Mn,2+ Fe2+ (Ma et al., 2011[28]) and strongly inhibited by Hg2+, Cu2+ (Bhiri et al., 2008[7]), Ag+, Hg2+ (Elshafei et al., 2011[14]) and Cu 2+, Pb2+, Cd2+ (Ma et al., 2011[28]) respectively.

Figure 7. Effect of metal ions on β-glucosidase activity.

Table 3. Substrate specificities of β-glucosidase.

Substrate-specificity of the enzyme

The purified β-glucosidase enzyme was used to check the substrate specificity by reacting with various substrates like Xinghua filter paper, microcrystalline cellulose (1%), xylan (1%), CMC-Na (1%), pNPG (1%), pNPC (1%), Chitin (1%) and Salicin (0.5%). From the results (Table 3(Tab. 3)) it was observed that the enzyme β-glucosidase can effectively hydrolyze the Salicin (744.58 ± 0.12 IU) followed by microcrystalline cellulose (117.27 ± 0.75 IU). This enzyme can degrade filter paper, pNPG , pNPC and Chitin up to some extent but it had no activity against CMC-Na. Very similar findings were also reported by Ramani et al. (2012[32]) indicating Salicin as a best substrate for β-glucosidase activity. Various studies suggested that pNPG was good substrate for β-glucosidase activity (Elshafei et al., 2011[14]; Liu et al., 2012[27]).

Enzyme kinetics

The kinetic parameters Km and Vmax of the β-glucosidase enzyme was estimated by Lineweaver-Burk plot by using various concentrations of salicin as a substrate. The main purpose of this kinetics is to check the catalytic efficiency of proteins. Results (Figure 8(Fig. 8)) revealed that the Km and the Vmax of β-glucosidase were 14.881 mg/ml and 0.364 mg/ml, respectively. Km is the dissociation constant which represent the affinity of substrate in enzyme substrate (ES) complex. If the Km value is low, it means that enzyme had a stronger affinity with substrate. β-glucosidase enzyme from Penicillium purpurogenum KJS506 had a Vmax value of 934 U mg/protein (Jeya et al., 2010[20]). Ramani et al., (2012[32]) reported Km value of 0.057 mM from Penicillium funiculosum NCL1. Penicillium brasilianum also produced β-glucosidase enzyme which have Km and Vmax value of 0.09 mM and 76 mol min-1mg-1 respectively (Krogh et al., 2010[24]). In another study (Bhiri et al., 2008[7]) the β-glucosidase enzyme of Penicillium occitanis has Km and Vmax value of 0.37 mM and 0.55 μmolmin-1mg-1 respectively. Fusarium saloni β-glucosidase enzyme possessed Km and Vmax value of 1 mM and 55.6 μmolmin-1 respectively (Bhatti et al., 2013[6]).

Figure 8. Lineweaver-Burk plots of β-glucosidase against salicin.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

The efficiency of the β-glucosidase enzyme was checked by hydrolyzing the cellulobiose to glucose. Figure 9(Fig. 9) illustrated the HPLC chromatograms of standard glucose and cellubiose (upper graph) and experimental (lower graph) study. Results indicated that this enzyme efficiently hydrolyze the cellubiose and produced 10 mg/ml of glucose in one hour of incubation at 50 °C. This results were comparable to Mutalik et al., (2012[30]) who reported that cellulase enzyme preparation from Ruminococcus albus can produce 17.4 mg/ml of glucose from 3.5 % substrate (Sugarcane bagasse) after 66 h of saccharification at 39 °C. Complete hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose is done by the action of endoglucanases, cellubiohydrolases and β-glucosidase (Olsson et al., 2004[31]; Wilson and Irwin, 1999[37]).

Figure 9. Enzymatic degradation of cellobiose by β-glucosidase enzyme produced from Penicillium simplicissimum H-11, Red line indicates standard and blue line indicates experimental.

Crystalline nature of cellulose hindered the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic material and this is insoluble in water (Olsson et al., 2005[31]). But here the nature of the substrate, source of enzyme and saccharification conditions played a pivotal role to make the process cost effective particularly in ethanol production.

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by Shenyang Agricultural University Youth Fund (20081019); Shenyang Agricultural University Postdoctoral Fund (82523) in National Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Soil and Fertilizer Resources and Plant Nutrition and new fertilizer academic innovation team project

Notes

Hongzhi Bai and Hui Wang contributed equally as first authors.

References

- 1.Banker J. Amide modes and protein conformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1120:123−43. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90261-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begum MF. Bangladesh: University of Rajshahi, Department of Botany; 2005. Screening of Aspergilli from cellulosic waste materials and studies on their cellulolytic properties. Ph.D. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begum MF, Absar N. Purification and characterization of intracellular cellulase from Aspergillus oryzae ITCC-4857.01. Mycobiology. 2009;37:121–127. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat MK. Cellulases and related enzymes in biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv. 2000;18:355–83. doi: 10.1016/s0734-9750(00)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia Y, Mishra S, Bisaria VS. Microbial β-glucosidases: cloning, properties, and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2002;22:375–407. doi: 10.1080/07388550290789568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatti HN, Batool S, Afzal N. Production and characterization of a novel β-glucosidase from Fusarium solani. Int J Agric Biol. 2013;15:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhiri F, Chaabouni SE, Limam F, Ghrir R, Marzouki N. Purification and biochemical characterization of extracellular beta-glucosidases from the hypercellulolytic Pol6 mutant of Penicillium occitanis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2008;149:169–182. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analyt Biochem. 1976;72:248. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byler DM, Susi H. Examination of the secondary structure of proteins by deconvolved FTIR spectra. Biopolymer. 1986;25:469−87. doi: 10.1002/bip.360250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chauve M, Mathis H, Huc D, Casanave D, Monot F, Ferreira NL. Comparative kinetic analysis of two fungal β–glucosidases. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2010;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Chen Y, Lu MJ, Chang J, Wang HC, Ke H, et al. A highly efficient β-glucosidase from the buffalo rumen fungus Neocallimastix patriciarum W5. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong A, Caughey B, Caughey WS, Bhat KS, Coe JE. Secondary structure of the pentraxin female protein in water determined by infrared spectroscopy: Effects of calcium and phosphorylcholine. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9364−70. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott A, Ambrose EJ. Structure of synthetic polypeptides. Nature. 1950;165:921−2. doi: 10.1038/165921a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elshafei AM, Hassan MM, Morsi NM, Elghonamy DH. Purification and some kinetic properties of β-glucosidase from Aspergillus terreus NRRL 265. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:19556–19569. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esen A. ß-glucosidases: Overview, biochemistry and molecular biology. Washington DC, USA: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gargouri M, Smaali I, Maugard T, Legoy MD, Marzouki N. Fungus b-glycosidases. Immobilization and use in alkyl-β-glycoside synthesis. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2004;29:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henrissat B, Davies GJ. Structural and sequence based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 1997;7:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irfan M, Syed Q, Abbas S, GulSher M, Baig S, Nadeem M. FTIR and SEM analysis of thermo-chemical fractionated of Sugarcane Bagasse. Turk J Biochem. 2011;36:322–328. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeya M, Joo AR, Lee KM, Tiwari MK, Lee KM, Kim SH, et al. Characterization of beta-glucosidase from a strain of Penicillium purpurogenum KJS506. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:1473–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karboune S, Geraert PA, Kermasha S. Characterization of selected cellulolytic activities of multi-enzymatic complex system from Penicillium funiculosum. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:903–909. doi: 10.1021/jf072847l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong J, Yu S. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic analysis of protein secondary structures. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2007;39:549–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1986;38:181−364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogh KB, Harris PV, Olsen CL, Johansen KS, Hojer-Pedersen J, Borjesson J, et al. Characterization and kinetic analysis of a thermostable GH3 beta-glucosidase from Penicillium brasilianum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriaophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lis H, Sharon N. Protein glycosylation. Europ J Biochem. 1993;218:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu D, Zhang R, Yang X, Zhang Z, Song S, Miao Y, et al. Characterization of a thermostable b-glucosidase from Aspergillus fumigatus Z5, and its functional expression in Pichia pastoris X33. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma S, Leng B, Xu X, Zhu X, Shi Y, Tao Y, et al. Purification and characterization of β-1,4-glucosidase from Aspergillus glaucus. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:19607–19614. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyazawa T, Shimanouchi T, Mizushima S. Characteristic infrared bands of monosubstituted amides. J Chem Phys. 1956;24:408. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutalik S, Kumar CSV, Swamy S, Manjappa S. Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic feedstock by Rumniococcus albus in production of biofuel ethanol. Ind J Biotechnol. 2012;11:453–457. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson L, Jorgensen H, Krogh KBR, Roca C. Bioethanol production from lignocellulosic material. In: Dumitriu S, editor. Polysaccharides: structural diversity and functional versatility. 2nd. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2005. pp. 957–993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramani G, Meera B, Vanitha C, Rao M, Gunasekaran P. Production, purification, and characterization of a β-glucosidase of Penicillium funiculosum NCL1. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;167:959–972. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riou C, Salmon JM, Vallier MJ, Gunata Z, Barre P. Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity of a novel highly glucose-tolerant β-glucosidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3607–3614. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3607-3614.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Susi H, Byler DM. Resolution-enhanced fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 1986;130:290−311. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)30015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomaz T, Roche A. Hydrophobic interaction, chromatography of trichoderma reesei cellulase on polypropylene glycol-sepharose. Sep Sci Technol. 2002;37:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varghese JN, Hrmova M, Fincher GB. Three-dimensional structure of a barley beta-D-glucan exohydrolase, a family 3 glycosyl hydrolase. Structure. 1997;7:179–190. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson DB, Irwin DC. Genetics and properties of cellulases. In: Tsao GT, editor. Recent progress in bioconversion of lignocellulosics. Berlin: Springer; 1999. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]