Abstract

Glomerular disease often features altered histologic patterns of extracellular matrix (ECM). Despite this, the potential complexities of the glomerular ECM in both health and disease are poorly understood. To explore whether genetic background and sex determine glomerular ECM composition, we investigated two mouse strains, FVB and B6, using RNA microarrays of isolated glomeruli combined with proteomic glomerular ECM analyses. These studies, undertaken in healthy young adult animals, revealed unique strain- and sex-dependent glomerular ECM signatures, which correlated with variations in levels of albuminuria and known predisposition to progressive nephropathy. Among the variation, we observed changes in netrin 4, fibroblast growth factor 2, tenascin C, collagen 1, meprin 1-α, and meprin 1-β. Differences in protein abundance were validated by quantitative immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis, and the collective differences were not explained by mutations in known ECM or glomerular disease genes. Within the distinct signatures, we discovered a core set of structural ECM proteins that form multiple protein–protein interactions and are conserved from mouse to man. Furthermore, we found striking ultrastructural changes in glomerular basement membranes in FVB mice. Pathway analysis of merged transcriptomic and proteomic datasets identified potential ECM regulatory pathways involving inhibition of matrix metalloproteases, liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, notch, and cyclin-dependent kinase 5. These pathways may therefore alter ECM and confer susceptibility to disease.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, cell-matrix-interactions, albuminuria

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex niche of structural and regulatory proteins that provide the supporting scaffold for cells. In addition to the loose networks of ECM surrounding all cells, basement membranes (BMs) represent the condensed networks of ECM, which underlie all epithelial sheets. ECM determines tissue rigidity,1 has roles in cell signaling,2–4 is critical for tissue development5,6 and is implicated in genetic and acquired diseases.7–10 Proteomic approaches are being pursued for global analyses of the complex niche represented by ECM11–13 and such studies are beginning to help unravel ECM roles in health and disease.14,15

Glomerular disease often features altered histologic patterns of ECM. Candidate-based investigations of glomerular ECM demonstrate the presence of tissue-restricted isoforms of collagen IV16 and laminin,17 and mutations of genes encoding these proteins cause glomerular disease.18 Dysregulated glomerular ECM is only understood at a rudimentary level although there is potential for therapeutic targeting.18 We recently exploited mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics to characterize healthy human glomerular ECM in an unbiased manner,19 identifying 144 proteins, demonstrating the complexity of this niche. Furthermore, we identified a core of highly connected ECM proteins which may be required for BM assembly.20

Alongside ECM changes, glomerular disease features loss of barrier integrity manifest as increased albuminuria. In overtly healthy human populations, albuminuria varies with racial background21,22 and sex.23,24 This is recapitulated in inbred mouse strains: for example, young adult FVB mice have 8-fold greater albuminuria than B6 mice25 and within each of these strains, males have 2-fold greater albuminuria than females.25 The albuminuria range between female B6 and male FVB mice corresponds, after factoring for weight, to human albuminuria of 30–300 mg/day. Notably, there are no significant differences in systemic blood pressure between FVB and B6 mice but the former have significantly fewer glomeruli/kidney.25 Furthermore, FVB mice have more severe disease than B6 mice in nephropathy models.26,27

In this investigation, we tested the hypotheses that genetic background and sex influence glomerular ECM and that ECM composition relates to the degree of albuminuria. We investigated B6 and FVB mouse strains using RNA microarrays of isolated glomeruli combined with proteomic analyses of glomerular ECM and we examined ECM structure with electron microscopy (EM).

Results

RNA Profiling

We undertook principal component analysis (PCA) of all detected transcripts in microarrays from glomeruli isolated from B6 and FVB mice.25 The determinants of sample variation were strain and sex (PC-1: 94.4%; PC-2: 3.6% of the total variation) (Supplemental Figure 1A). Using gene ontology (GO) classification, the subset of ECM transcripts was selected and a further PCA revealed that the strains could still be distinguished, (PC-1, 91.6%; PC-2, 6.3% of the total variation) but there was less variation between sexes (Supplemental Figure 1A). Similar separation was observed using unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Supplemental Figure 1B) where the ECM transcript data segregated into clusters relating to strains and within the strains, sexes clustered together. Upregulated gene clusters were categorized by GO enrichment analysis (Supplemental Table 1) and the top five enriched terms were annotated onto the clustered heat map (Supplemental Figure 1B). This revealed enrichment of neuronal development and peptidase inhibitor activity in FVB glomeruli. Conversely, GO ECM terms, including adhesion and receptor binding, were enriched to B6 glomeruli. Thus, the glomerular transcriptome, including ECM transcripts, is influenced by strain and, to a lesser extent, by sex.

ECM Enrichment

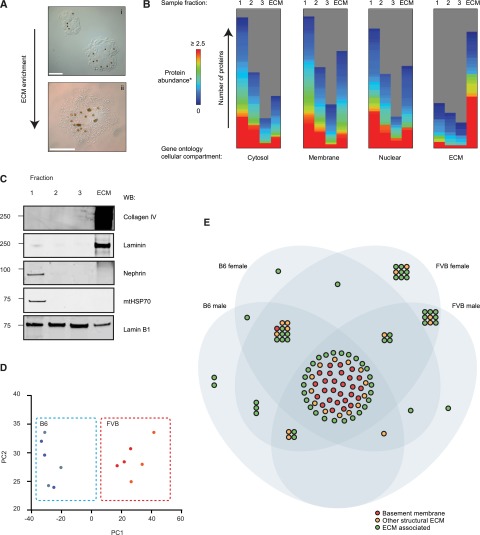

To analyze glomerular ECM using proteomics we developed a workflow for ECM isolation, adapted from our human glomerular studies19 (Supplemental Figure 2A). We harvested mouse glomeruli using Dynabead perfusion25 and this approach yielded significantly more glomeruli/kidney versus sieving (Supplemental Figure 2B). Glomeruli were fractionated to produce an enriched ECM fraction (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 2A) and enrichment was confirmed by GO analysis of MS identifications (Figure 1B). Western blotting also confirmed enrichment with increased laminin and collagen IV but reduced cellular proteins in the ECM fraction (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Proteomic analysis identifies genetic background as a regulator of ECM composition. (A) Glomeruli isolated by Dynabead perfusion and magnetic particle concentration. Dynabeads can be seen in glomeruli (brown dots): (i) isolated glomerulus prior to detergent extraction, (ii) glomerulus post detergent extraction. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (B) Isolated fractions were analyzed by MS. Fractions 1–3 represent the supernatants from the extraction protocol, the ECM fraction represents the final ECM enriched fraction. Identified proteins were grouped by GO cellular compartment and visualized with MeV. Height of the bar represents the number of proteins in each GO compartment identified in the indicated fraction. (C) Western blot analysis confirming ECM enrichment. (D) Principal component analysis of glomerular ECM proteins identified by MS. B6 females, blue dots; B6 males, gray dots; FVB females, orange dots; FVB males, red dots. (E) Venn diagram glomerular ECM proteins identified by MS. Nodes (circles) represent proteins. ECM proteins were categorized as BM, other structural ECM or ECM-associated proteins and were colored accordingly. The Venn diagram sets indicate in which ECMs each protein was identified. *Protein abundance was determined by normalized spectral counting. MeV, multiple experimental viewer.

ECM Proteomes

Triplicate enriched ECM fractions from the four groups (i.e., FVB and B6 male and females) were analyzed by MS. Identified proteins were classified as ECM as previously defined.19,20 A combination of the mouse matrisome resource12 and DAVID GO28 was used to classify proteins as BM, other structural ECM or ECM-associated (Supplemental Table 2). Overall, 115 ECM proteins were identified, consistent with murine colon (106), murine lung (143), human aorta (103), and human glomerular ECM (144),12,19,29 and PCA analyses found the main cause of sample variation was strain (PC-1, 85.6%; PC-2, 4.7% of the total variation) (Figure 1D). We compared the ECM proteome with the ECM transcriptome and found a weak, but significant, correlation (r=0.22, P<0.001) (Supplemental Figure 2C), in keeping with previous studies in skin.30

The proteomic data were used to generate a glomerular ECM protein–protein interaction network. Most glomerular ECM proteins (58%) were identified in all four groups of mice (Figure 1E, Supplemental Table 2). This common subset of proteins, including all known major glomerular ECM components, formed the most highly connected network, making 92% of reported protein–protein interactions and contained almost all (96%) of the BM and 52% of other structural ECM proteins identified in the dataset. ECM-associated proteins were more peripherally associated with the interaction network (Figure 2). The subset of connected proteins likely represents components essential for glomerular ECM assembly and/or maintenance.

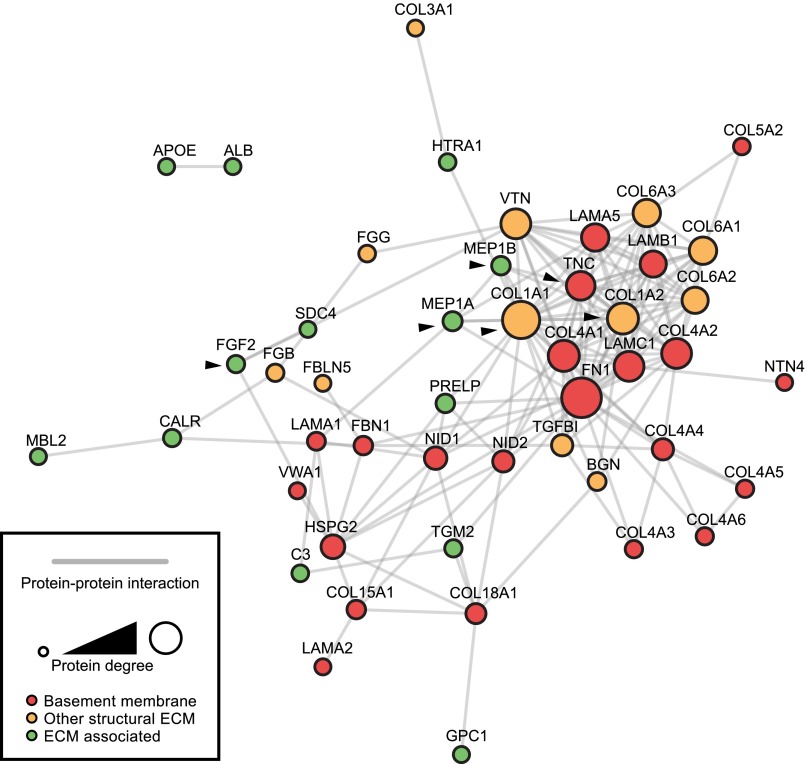

Figure 2.

Protein interaction network constructed from enriched glomerular ECM proteins identified by MS. Nodes (circles) represent proteins and edges (gray lines) represent reported protein–protein interactions. Nodes are labeled with gene names for clarity. ECM proteins were categorized as BM, other structural ECM or ECM-associated proteins and were colored accordingly. Node diameter is proportional to number of interaction partners (degree). The interaction network was clustered, and topological parameters were computed. Self-interactions were excluded from the analysis. Black arrowheads indicate proteins that were selected for further study.

Using topological network analysis of all ECM proteins identified by MS, BM proteins made significantly more interactions than ECM-associated proteins (Supplemental Figure 3A). Moreover, 60% of BM and other structural ECM proteins were shared in human and mouse datasets (Supplemental Figure 3B) and the mouse–human shared interactome contained 74% of all protein–protein interactions identified from both datasets, thus emphasizing the overlap between human and mouse glomerular ECM in both composition and network topology.

Enriched ECM Proteins

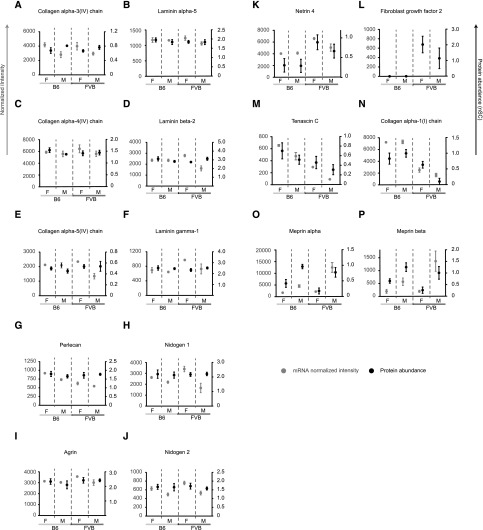

Globally there were no significant differences in the subtypes of ECM proteins between mouse groups (Supplemental Figure 3, C–E). Therefore to assess variation in individual proteins we focused on abundant proteins (>5 spectral counts) present in our interaction network (Figure 2). While we did not find significant changes in known GBM components (Figure 3, A–J), we observed consistent variation in others. Netrin 4 was more abundant (microarray and MS) in FVB versus B6 mice (Figure 3K). FGF2 protein was detected in FVB but not B6 (MS), however Fgf2 transcripts were below the microarray detection level (Figure 3L). Tenascin C levels (microarray and MS) were highest in B6 females and lowest in FVB males (Figure 3M). Alpha-1 and -2 chains of collagen I were more abundant (microarray and MS) in B6 versus FVB (Figure 3N) and in both strains, the matrix metalloproteases meprin 1-α and meprin 1-β were more abundant in males than females (Figure 3, O and P). These candidates were therefore selected for further investigation.

Figure 3.

Glomerular ECM proteins regulated by genetic background or sex. Comparison of selected ECM protein abundance determined by MS and microarray transcript level. (A–J) Known major glomerular ECM components do not show robust alteration in protein abundance detected by MS. (K–P) Specific ECM proteins have altered protein MS abundance due to stain and sex.

Validation of Candidates and Correlation with Albuminuria

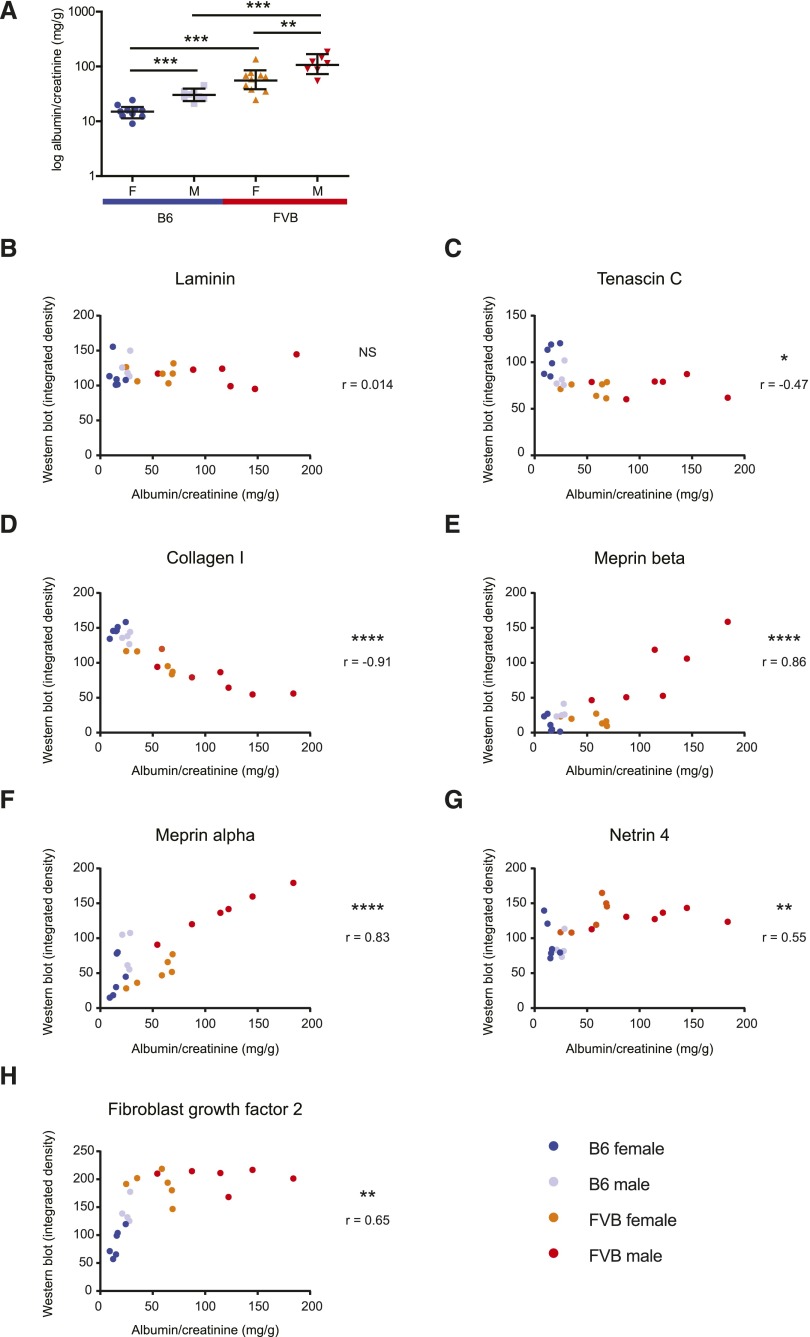

In the main cohort of mice, protein abundance was validated using quantitative immunohistochemistry. Here we found that laminin and collagen IV were equally detected across all four groups whereas FGF2 and netrin 4 were highest in FVB, collagen I and tenascin C were highest in B6 and meprins were highest in males (Figure 4, A and B). To determine whether changes in ECM protein abundance correlated with albuminuria, we measured albumin creatinine ratios (ACR) in a second cohort of mice and analyzed candidate ECM proteins in these mice by quantitative Western blot (Figure 4C, Supplemental Figure 4). We found albuminuria at 18 weeks followed the previously reported pattern (B6f<B6m<FVBf<FVBm)25 (Figure 5A) and there was correlation between abundance of candidate ECM proteins and albuminuria. As predicted from the microarray and MS, laminin abundance did not correlate with ACR (r=0.014, P>0.95) (Figure 5B). Collagen I had a strong negative correlation (r=−0.91, P<0.0001) and tenascin C had a weaker correlation (r=−0.47, P=0.027) (Figure 5, C and D). Meprin 1-α and 1-β correlated most strongly with ACR (r=0.83, P<0.0001 and 0.86, P<0.0001, respectively) (Figure 5, E and F) whereas netrin 4 and FGF2 showed a weaker correlation (r=0.55, P=0.0087 and r=0.65, P=0.0012, respectively) (Figure 5, G and H). Finally we performed validation with qRT-PCR and that found both Ntn4 and Fgf2 increased in FVB compared with B6 mice (Supplemental Figure 5, A and B). Tenascin C showed an expression pattern B6f>B6m>FVBf>FVBm in both microarray and MS datasets. The order was slightly different with qRT-PCR where B6m>B6f>FVBf>FVBm (Supplemental Figure 5C). In keeping with microarray and MS, collagen I-α 2 was increased in B6 mice (Supplemental Figure 5D). Only the qRT-PCR of meprin α and β did not follow the pattern of microarray or MS (Supplemental Figure 5, E and F). Overall these findings validate the selected ECM proteins and demonstrate striking correlation with albuminuria.

Figure 4.

Validation of glomerular ECM proteins regulated by genetic background or sex. (A) Representative fluorescence immunohistochemistry images using antibodies to proteins, which were indicated by mass spectrometry (MS) to be altered due to genetic background or sex. Dapi staining in blue, scale bar represents 25 mm. (B) Quantification of normalized mean pixel intensity of glomeruli, measured using fiji image J software. F, females; M, males. Points represent individual glomerular measurements n>60 from n=3 mice. Box plots indicate 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper bounds, respectively), 1.5× interquartile range (whiskers) and median (line). (C) Western blot analysis of glomerular ECM extracts using antibodies to proteins, which were indicated by MS to be altered due to genetic background or sex.

Figure 5.

Correlation of glomerular ECM protein abundance with albumin-to-creatinine ratio. (A) Overnight albumin-to-creatinine ratios were evaluated in 18-week-old adult mice (n=8–10). Data were log transformed before analysis and are presented as geometric means and confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by least squares difference. There was a significant increase in urinary albumin in male and female FVB mice compared with sex-matched B6 animals. Within each strain, males had elevated albuminuria versus females. (B–H) Correlation of albumin-to-creatinine ratio with abundance of selected glomerular ECM protein candidates detected by Western blot (n=4–6). Correlation analysis was performed using two-tailed Pearson correlation *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. M, males; F, females.

BM Ultrastructural Variation

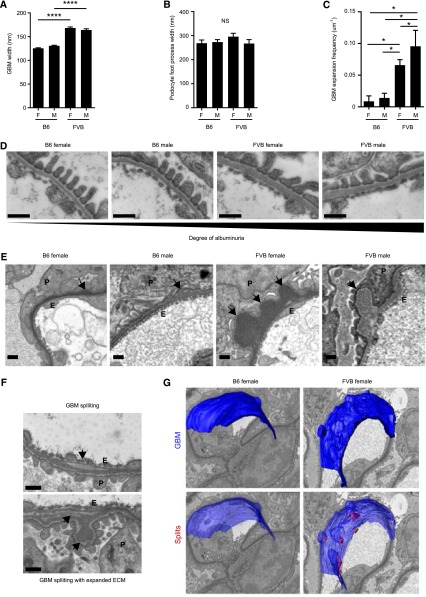

Having discovered compositional change in ECM, we proceeded to investigate ECM organization. Transmission EM (TEM) and serial block face scanning EM (SBF-SEM) were used to examine glomerular BMs (GBMs). GBMs were significantly thicker in FVB than B6 mice (Figure 6A) although podocyte foot process width was unchanged (Figure 6B). The thickened GBM was confirmed with SBF-SEM using 3D reconstructions (Supplemental Movie 1). Moreover, SBF-SEM identified reproducible sub-podocyte regions of thickened and expanded GBM in FVB mice (Figure 6, C–E, Supplemental Movies 2 and 3), only rarely observed in B6 (Figure 6E, Supplemental Movies 4 and 5). In association with the expanded regions, there was splitting of the GBM in FVB mice, whereas B6 GBMs were smooth and regular without splits (Figure 6, F and G). Manual contouring (segmenting) of SBF-SEMs enabled visualization of these ultrastructural variations (Supplemental Movies 6–9).

Figure 6.

Structural abnormalities in glomerular ECM in disease-susceptible FVB mice. (A, D) The GBM is significantly thicker in FVB compared with B6 mice, whereas in both strains podocyte cytoarchitecture is preserved, with normal foot processes (TEM images). (A) Quantification of GBM thickness. (B) Quantification of podocyte foot process width. (E) The GBM of FVB mice contain significantly more sub-podocyte GBM expansions compared with B6 mice (SBF-SEM images). Arrows highlight sub-podocyte GBM expansions. (C) Quantification of sub-podocyte GBM expansions. (F) Representative images of GBM splitting (arrows) in FVB female mice (TEM images). GBM, glomerular BM. *P<0.05; ****P<0.001, n=15 glomeruli from n=3 mice. (G) 3D model of B6 and FVB GBMs (blue) and splits within the GBM (red). Splits are closely associated with areas of expansion in FVB mice. Scale bars represent 500 nm. F, female; M, male; E, endothelial cells; P, podocytes.

Biologic Pathways Analysis

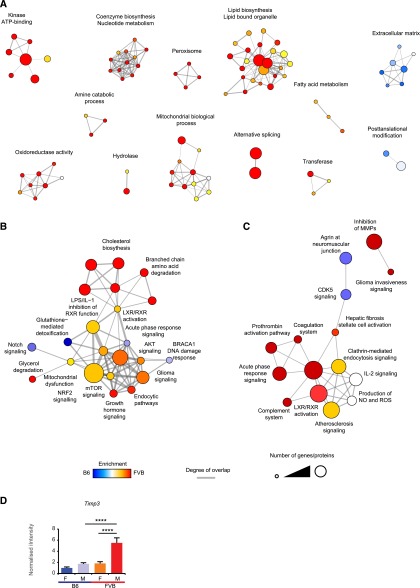

Available exome data from B6 and FVB mice were interrogated for the 4586 genes predicted from the microarray to be influenced by strain (Anova; P<0.01) together with known glomerular genes. No frame-shift, truncation or read-through mutations were found (Supplemental Figure 6). Because analysis of quantitative trait loci would be a substantial and independent study,31 we performed GO enrichment and pathway analyses on proteomic and microarray datasets to gain insight into ECM regulatory pathways. Components and GO terms selectively enriched in a strain-dependent manner were hierarchically clustered to produce a heat map and associated dendograms (Supplemental Figure 7A). In this analysis, the FVB data associated with terms for inflammation, wound healing and cell adhesion, whereas collagen and epithelial development terms associated with the B6 strain. We created a GO enrichment map view for proteins enriched in FVB or B6 and, for each strain, found a single highly clustered network of GO terms, all related to ECM. The only difference in the two clusters was the enrichment of protease inhibitor terms in the FVB cluster (Supplemental Figure 7B). Using GO enrichment map view for the whole microarray, we found few terms enriched to B6 glomeruli and these included an ECM cluster and terms relating to post-translation modifications (Figure 7A). However, FVB glomeruli had many enriched terms (Figure 7A). Three clusters relating to peroxisome, fatty acid metabolism and lipid biosynthesis and organelles would be consistent with altered lipid processing. Similarly, clusters relating to coenzyme biosythesis and mitochondrial biologic processes would be consistent with altered mitochondrial biology. Using pathway prediction tools to compare ECM transcripts and ECM proteins, we identified a link from lipid metabolic pathways via LXR/RXR signaling to NRF2 and mTOR signaling pathways, which were predicted to be more active in FVB versus B6 glomeruli (Figure 7, B and C). Conversely, notch signaling and CDK5 signaling were predicted to be active in B6 glomeruli (Figure 7, B and C). In FVB glomeruli, inhibition of matrix metalloproteases was predicted with several approaches (Supplemental Figures 1B, 7, B and C). Interestingly, metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP3) was detected by MS in only FVB animals, but microarray data suggested no difference in expression. Further analysis with qRT-PCR demonstrated that Timp3 levels were significantly increased in FVB males (Figure 7D). Overall, these analyses reveal potential novel pathways, which may regulate glomerular ECM and confer susceptibility to glomerular disease.

Figure 7.

GO enrichment map and ingenuity pathway analysis. (A) GO enrichment map of terms significantly enriched in FVB or B6 glomerular microarray. (B) Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of canonical pathways enriched in whole glomerular microarray. (C) IPA of canonical pathways enriched in glomerular ECM proteomic dataset. Nodes (circles) represent GO terms/IPA canonical pathways significantly enriched in the microarray/proteomic data-sets, edges (lines) represent overlap of proteins within terms. Node size relates to the number of genes/proteins which are allocated to a given term and node color relates to the enrichment to either FVB (red) or B6 (blue). (D) qPCR analysis of Timp3 levels. M, males; F, females.

Discussion

Using global analyses of glomerular ECM and validation with quantitative immunohistochemistry, Western blot and qRT-PCR, we report: (1) unique strain- and sex-dependent glomerular ECM signatures correlating with variations in albuminuria and known predisposition to progressive nephropathy, (2) striking ultrastructural changes in glomerular basement membranes in high albuminuria/nephropathy-susceptible FVB mice, and (3) a core set of structural ECM proteins, which form multiple protein–protein interactions, and which are conserved from mouse to man.

Among changes in composition, netrin 4 was enriched in glomerular ECM from FVB mice. Netrin 4 may be involved in BM assembly32 and epithelial cells adhere to netrin 4 via α1β2 and α3β1 integrins,33 both of which are expressed by podocytes. However, the regulation of this ECM component and its requirement for GBM assembly has not been examined. FGF2 was also upregulated in FVB datasets and this growth factor, enriched in BMs, has tissue-specific roles including angiogenesis, cell proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation.34 FGF2 signals via the FGF receptor tyrosine kinase and FGFR signaling is critical for the growth and patterning of all renal lineages.34 In the glomerulus, FGF2 is expressed by podocytes and mesangial cells and podocytes lacking FGF signaling fail to rearrange their actin cytoskeleton.34 Increased FGF2 expression has also been associated with nephropathy models, suggesting that regulation of this pathway requires tight control.34 Our data support a pathologic role for increased FGF2 signaling in the glomerulus, and suggests it may influence ECM synthesis.

Components enriched to B6, low albuminuria/nephropathy-resistant mice included tenascin C and collagen I. Tenascin C is a glycoprotein that modulates the functions of fibronectin35 and it is involved in neuronal guidance.36 Collagen I is the predominant structural component of bone and cartilage and a functional role in the glomerulus has yet to be found. Both collagen I and tenascin C are associated with wounding and organ fibrosis, however, our data suggest these proteins may be protective. In our analysis we found few changes related to sex, although protein levels of meprin metalloproteases were enriched to males of both strains. Meprins were originally identified in kidney and intestine and have been shown to have roles in angiogenesis, cancer, inflammation, fibrosis and neurodegenerative disease processes.37 Meprin 1-α and meprin 1-β are unique in their ability to process and release both C- and N-propeptides from type I procollagen,38 and many other ECM substrates.39 Our data support a role for these ECM regulatory proteins as sex-associated modifiers of glomerular barrier function.

Having identified changes in ECM composition, we used serial EM sectioning to interrogate structure and we identified GBM defects, which correlated with barrier dysfunction. Abnormal GBM is found across a range of human disease; however, the homogenous expansions we observed were unlike immune-complex deposits. The defects were similar to those seen in mice with global and podocyte-specific deletion of adhesion and matrix proteins, although these phenotypes are often dependent on the genetic background of the mice.27,40,41 We speculate that weakened or split regions of GBM are sensed by podocytes and/or endothelial cells leading to increased synthesis of ECM in an attempt to repair the damage. Alternatively GBM expansions are weak points in the capillary walls susceptible to splitting. We observed these structural changes despite no alterations in known GBM components; collagen IV α-3,4,5 and laminin 521, perlecan, agrin and nidogen 1 and 2. In future studies it would be important to investigate whether changes in netrin 4 or meprins, which were increased in the GBM of FVB and males, respectively, contribute to the structural changes we have observed.

Having identified altered composition and organization of ECM, the question of cause and effect remained. We therefore screened whole exome data from FVB and B6 mice and did not find any mutations in known ECM or glomerular genes. Notably, our previous studies have shown that young adult FVB mice have significantly fewer glomeruli per kidney compared with B6 mice.25 It has been postulated that congenital nephron deficit predisposes to arterial hypertension and progressive kidney injury42; however, there were no significant differences in systemic arterial pressure between the two adult strains used in this study.25 It remains possible that altered intraglomerular hemodynamics are present in FVB mice and these contribute to the altered ECM we report.

To appreciate regulatory pathways associated with our observations, we performed systems-level analysis. With global microarray data we found enrichment of GO terms relating to mitochondrial dysfunction, activation of NRF2 and lipid metabolism with FVB mice. NRF2 is an antioxidant transcription factor and it increases the expression of ROS detoxification genes, which have been associated with diabetic kidney disease.43 In the B6 strain, notch signaling was active and this pathway is key for glomerular patterning.44 In addition, notch intracellular domain expression is increased in glomerular epithelial cells in diabetic nephropathy and in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.45,46 Analysis of the proteomics data predicted CDK5 pathway activity in B6 mice and the Cyclin I-CDK5 complex safeguards podocytes against apoptosis via MAPK signaling.47 By combining microarray and proteomic data we identified activity of the LXR/RXR pathway with the FVB strain. LXR/RXR are nuclear hormone receptors that act as transcription factors to regulate the expression of genes involved in cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism.48 In the kidney, LXRs are specifically expressed in renin-producing juxtaglomerular cells and LXRs were shown to regulate renin expression in vivo, suggesting crosstalk between the RAAS and lipid metabolism.49 Overall our systems-level analysis identified novel pathways, which may lead to changes in ECM and therefore could be the targets of therapeutic intervention to restore glomerular barrier function.

Concise Methods

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies used were against actin (clone AC-40; Sigma-Aldrich-Aldrich, Poole, UK) mtHSP70 (MA3–028; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts), nidogen (MAB1946; EMD Millipore), tenascin C (MAB2138; R&D Systems), and meprin β (MAB28951; R&D Systems). Polyclonal antibodies used were against lamin B1 (ab16048; Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, UK), pan-collagen IV (ab6586; Abcam, Inc.), pan-laminin (ab11575; Abcam, Inc.), nephrin (ab58968; Abcam, Inc.), fibroblast growth factor 2 (ab106245; Abcam, Inc.), netrin 4 (AF1132; R&D Systems), meprin α (AP5858a; Agent), and collagen I (2150–1410; AbD Serotec). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 680 (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) or IRDye 800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) were used for Western blotting. Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Life Technologies) were used for immunohistochemistry.

Mice

C57BL/6JOlaHsd (referred throughout as B6) and FVB/NHanHsd (referred throughout as FVB) mice were used for these experiments and the four experimental groups were B6 female, B6 male, FVB female, and FVB male. n=3 mice per group were used for MS, n=3 mice for microarray, n=3 mice for qRT-PCR, n=3 animals for immunohistochemistry, and n=6 mice for Western blot. For the measurement of albuminuria, urine was collected from 18-week-old mice by housing them individually in metabolic cages for 18 hours. Albumin concentrations were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, Texas).25,50 Urinary creatinine concentrations were assessed by a commercially available assay (Cusabio, Newark, Delaware).25 Data were log transformed before analysis and are presented as geometric means and confidence intervals.

Global Microarray

This methodology is described in Supplementary Methods.

Isolation of Murine Glomeruli and Enrichment of Glomerular ECM

The glomeruli of 18-week-old male and female mice (n=3 in each of four groups) were isolated through the Dynabead-based isolation method.51 All steps were carried out at 4°C to minimize proteolysis. Pure glomerular isolates from three mouse kidneys were incubated for 30 minutes in extraction buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 25 mM EDTA, 25 μg/ml leupeptin, 25 μg/ml aprotinin and 0.5 mM AEBSF) to solubilize cellular proteins, and samples were then centrifuged at 14000× g for 10 minutes to yield fraction 1. The remaining pellet was incubated for 30 minutes in alkaline detergent buffer (20 mM NH4OH and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS) to further solubilize cellular proteins and to disrupt cell–ECM interactions. Samples were then centrifuged at 14000× g for 10 minutes to yield fraction 2. The remaining pellet was incubated for 30 minutes in a deoxyribonuclease (DNase) buffer (10 μg/ml DNase I (Roche, Burgess Hill, UK) in PBS) to degrade DNA. The sample was centrifuged at 14000× g for 10 minutes to yield fraction 3, and the final pellet was re-suspended in reducing sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 4% (w/v) sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), 0.004% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 8% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol) to yield the ECM fraction. Samples were heat denatured at 70°C for 20 minutes.

Western Blotting

This methodology is described in Supplementary Methods.

qRT-PCR

This methodology is described in Supplementary Methods.

MS Data Acquisition

Protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining. Gel lanes were sliced and subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion as described previously.52 Liquid chromatography–tandem MS analysis was performed using a nanoACQUITY UltraPerformance liquid chromatography system (Waters, Elstree, UK) coupled offline to an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Desalted peptides were separated on a bridged ethyl hybrid C18 analytical column (250 mm length, 75 μm inner diameter, 1.7 μm particle size, 130 Å pore size; Waters) using a 45-min linear gradient from 1% to 25% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid at a flow rate of 200 nl/min. Peptides were selected for fragmentation automatically by data-dependent analysis.

MS Data Analysis and Data Deposition

Tandem mass spectra were extracted using extract_msn (Thermo Fisher Scientific) executed in Mascot Daemon (version 2.2.2; Matrix Science, London, UK). Peak list files were searched against a modified version of the Uniprot mouse database (version 3.70; release date, May 3, 2011), containing ten additional contaminant and reagent sequences of non-mouse origin, using Mascot (version 2.2.06; Matrix Science).53 Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification; oxidation of methionine and hydroxylation of proline and lysine were allowed as variable modifications. Only tryptic peptides were considered, with up to one missed cleavage permitted. Monoisotopic precursor mass values were used, and only doubly and triply charged precursor ions were considered. Mass tolerances for precursor and fragment ions were 0.4 Da and 0.5 Da, respectively. MS datasets were validated using rigorous statistical algorithms at both the peptide and protein level54,55 implemented in Scaffold (version 3.6.5; Proteome Software, Portland, Oregon). Protein identifications were accepted upon assignment of at least two unique validated peptides with ≥90% probability, resulting in ≥99% probability at the protein level. These acceptance criteria resulted in an estimated protein false discovery rate of 0.1% for all datasets. MS data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://www.proteomexchange.org) with the dataset identifier PDX000811 and DOI 10.6019/PXD000811.

Bioinformatic Analyses

This methodology is described in Supplementary Methods.

Immunohistochemistry and Image Analysis

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were dewaxed and treated with recombinant proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 15 minutes. Sections were blocked with 5% (v/v) donkey serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.5% (v/v) BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes and with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed three times with PBS, incubated with secondary antibodies, mounted with polyvinyl alcohol mounting medium (Fluka 10981; Sigma-Aldrich) and imaged using Delta Vision (Applied Precision) restoration microscope using a 60× objective. The images were collected using a Coolsnap HQ (Photometrics) camera with a Z optical spacing of 0.2 μm. Raw images were then deconvolved using the Softworx software and projections of these deconvolved images are shown in the results. Images were also collected using a 20× objective and 3D Histech Pannoramic 250 Flash slide scanner. Images were processed and analyzed using Fiji/ImageJ software (version 1.46r; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Pannoramic Viewer (http://www.3dhistech.com/). Raw images were subjected to signal rescaling using linear transformation for display in the figures. For calculation of mean pixel intensity, a region of interest was drawn around glomeruli and the mean pixel intensity in the selected region measured. This was performed on secondary only controls and on the test samples. The signal from secondary only control samples was subtracted from test samples. Mean pixel intensity measurements were acquired from >60 glomeruli per biologic replicate.

Electron Microscopy

We used TEM and SBF-SEM to investigate glomerular ultrastructure. Tissue samples were fixed for at least 1 hour in a mix of 2% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The samples were post-fixed with reduced osmium (1% OsO4 and 1.5% K4Fe(CN)6) for 1 hour, then with 1% tannic acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour, and finally with 1% uranyl acetate in water overnight. The specimens were dehydrated with alcohols, infiltrated with TAAB LV resin and polymerized for 12 hours at 60°C. Ultrathin 70-nm sections were cut with a Leica Ultracut S ultramicrotome and placed on formvar/carbon-coated slot grids. The grids were observed in a Tecnai 12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. EMdata were screened for ECM characteristics between using Fiji/ImageJ software (version 1.46r; National Institutes of Health). GBM thickness was quantified in five regions per observation and reported as mean values. For SBF-SEM the polymerized samples were trimmed, glued to aluminum pins and sputter coated with gold/palladium (60 seconds at standard settings). Automated sectioning (60 nm) was completed in a Gatan 3View. The images were taken with FEI Quanta 250 FEG SEM at 3.8 kV accelerating voltage and 0.4 Torr chamber pressure with a pixel size of 12 nm. Models were generated from SBF-SEM using IMOD 3Dmod software developed by David Mastronade and co-workers at the Boulder Laboratory for three-dimensional electron microscopy, which can be downloaded from http://bio3d.colorado.edu/imod/download.html.

Mouse Strain SNP Analysis

The Jackson laboratory phenome resource was used in order to screen for small nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ECM proteins identified in this study, and transcripts identified by whole glomerular microarray. The SNP/genotype variation query tool (http://phenome.jax.org/) was used with the following criteria: Choose data sets, strains and filtering options, C57BL/6J, FVB/NJ, polymorphism between certain strains, all examined calls must be nonblank. We screened genes encoding ECM proteins identified by MS in this study, transcripts identified by whole glomerular microarray in addition to genes associated with glomerular disease.

Statistical Analysis

All measurements are shown as mean±SEM. Box plots indicate 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper bounds, respectively), 1.5×interquartile range (whiskers) and median (black line). Bar chart error bars represent standard error of the mean. Analysis of thickness of GBM, podocyte foot process width and frequency of GBM sub-podocyte expansions were compared using one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni correction. Numbers of protein–protein interactions and normalized fluorescence intensity were compared using Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance tests with post hoc Bonferroni correction.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellowship award (090006) to R.L., a Kids Kidney Research grant awarded to R.L. and A.S.W to support a studentship for M.J.R, a Kidney Research UK Senior Non-Clinical Fellowship (SF1/2008) and Medical Research Council New Investigator Award (MR/J003638/1) both to D.A.L., a Wellcome Trust grant (092015) to M.J.H. and by the Wellcome Trust (097820/Z/11/B) support for the bioinformatics department. The mass spectrometer and microscopes used in this study were purchased with grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Wellcome Trust and the University of Manchester Strategic Fund. Mass spectrometry was performed in the Biomolecular Analysis Core Facility, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, and we thank Stacey Warwood for advice and technical support and Julian Selley for bioinformatic support.

M.J.R., R.L., A.S.W., and D.L. planned the study, designed experiments and wrote the manuscript. K.L.P., M.K.J., S.C., T.D., J.H., A.M., and T.S. performed experiments and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. A.B., J.D.H., D.K., R.K., and M.H. contributed to the study design and analysis and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014050479/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Swift J, Ivanovska IL, Buxboim A, Harada T, Dingal PC, Pinter J, Pajerowski JD, Spinler KR, Shin JW, Tewari M, Rehfeldt F, Speicher DW, Discher DE: Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science 341: 1240104, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiller HB, Hermann MR, Polleux J, Vignaud T, Zanivan S, Friedel CC, Sun Z, Raducanu A, Gottschalk KE, Théry M, Mann M, Fässler R: β1- and αv-class integrins cooperate to regulate myosin II during rigidity sensing of fibronectin-based microenvironments. Nat Cell Biol 15: 625–636, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seong J, Tajik A, Sun J, Guan JL, Humphries MJ, Craig SE, Shekaran A, García AJ, Lu S, Lin MZ, Wang N, Wang Y: Distinct biophysical mechanisms of focal adhesion kinase mechanoactivation by different extracellular matrix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 19372–19377, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plotnikov SV, Pasapera AM, Sabass B, Waterman CM: Force fluctuations within focal adhesions mediate ECM-rigidity sensing to guide directed cell migration. Cell 151: 1513–1527, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hynes RO: The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science 326: 1216–1219, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miner JH: Building the glomerulus: a matricentric view. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 857–861, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arriazu E, Ruiz de Galarreta M, Cubero FJ, Varela-Rey M, Perez de Obanos MP, Leung TM, Lopategi A, Benedicto A, Abraham-Enachescu I,, Nieto N: Extracellular matrix and liver disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 21: 1078–1097, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachs N, Sonnenberg A: Cell-matrix adhesion of podocytes in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 200–210, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pozzi A, Voziyan PA, Hudson BG, Zent R: Regulation of matrix synthesis, remodeling and accumulation in glomerulosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des 15: 1318–1333, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce JA, Pollard JW: Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 239–252, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soteriou D, Iskender B, Byron A, Humphries JD, Borg-Bartolo S, Haddock MC, Baxter MA, Knight D, Humphries MJ, Kimber SJ: Comparative proteomic analysis of supportive and unsupportive extracellular matrix substrates for human embryonic stem cell maintenance. J Biol Chem 288: 18716–18731, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naba A, Clauser KR, Hoersch S, Liu H, Carr SA, Hynes RO: The matrisome: in silico definition and in vivo characterization by proteomics of normal and tumor extracellular matrices. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: M111.014647, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashid ST, Humphries JD, Byron A, Dhar A, Askari JA, Selley JN, Knight D, Goldin RD, Thursz M, Humphries MJ: Proteomic analysis of extracellular matrix from the hepatic stellate cell line LX-2 identifies CYR61 and Wnt-5a as novel constituents of fibrotic liver. J Proteome Res 11: 4052–4064, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byron A, Humphries JD, Humphries MJ: Defining the extracellular matrix using proteomics. Int J Exp Pathol 94: 75–92, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lennon R, Randles MJ, Humphries MJ: The importance of podocyte adhesion for a healthy glomerulus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 160, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miner JH, Sanes JR: Collagen IV alpha 3, alpha 4, and alpha 5 chains in rodent basal laminae: sequence, distribution, association with laminins, and developmental switches. J Cell Biol 127: 879–891, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miner JH, Patton BL, Lentz SI, Gilbert DJ, Snider WD, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sanes JR: The laminin alpha chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of alpha1-5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8-11, and cloning of a novel alpha3 isoform. J Cell Biol 137: 685–701, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh JH, Miner JH: The glomerular basement membrane as a barrier to albumin. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 470–477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lennon R, Byron A, Humphries JD, Randles MJ, Carisey A, Murphy S, Knight D, Brenchley PE, Zent R, Humphries MJ: Global analysis reveals the complexity of the human glomerular extracellular matrix. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 939–951, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byron A, Randles MJ, Humphries JD, Mironov A, Hamidi H, Harris S, Mathieson PW, Saleem MA, Satchell SC, Zent R, Humphries MJ, Lennon R: Glomerular cell cross-talk influences composition and assembly of extracellular matrix. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 953–966, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Saab G, Salvalaggio PR, Axelrod D, Davis CL, Abbott KC, Brennan DC: Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 363: 724–732, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanevold CD, Pollock JS, Harshfield GA: Racial differences in microalbumin excretion in healthy adolescents. Hypertension 51: 334–338, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould MM, Mohamed-Ali V, Goubet SA, Yudkin JS, Haines AP: Microalbuminuria: associations with height and sex in non-diabetic subjects. BMJ 306: 240–242, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksen BO, Ingebretsen OC: The progression of chronic kidney disease: a 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int 69: 375–382, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long DA, Kolatsi-Joannou M, Price KL, Dessapt-Baradez C, Huang JL, Papakrivopoulou E, Hubank M, Korstanje R, Gnudi L, Woolf AS: Albuminuria is associated with too few glomeruli and too much testosterone. Kidney Int 83: 1118–1129, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baleato RM, Guthrie PL, Gubler MC, Ashman LK, Roselli S: Deletion of CD151 results in a strain-dependent glomerular disease due to severe alterations of the glomerular basement membrane. Am J Pathol 173: 927–937, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laouari D, Burtin M, Phelep A, Martino C, Pillebout E, Montagutelli X, Friedlander G, Terzi F: TGF-alpha mediates genetic susceptibility to chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 327–335, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA: Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Didangelos A, Yin X, Mandal K, Baumert M, Jahangiri M, Mayr M: Proteomics characterization of extracellular space components in the human aorta. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 2048–2062, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Küttner V, Mack C, Rigbolt KT, Kern JS, Schilling O, Busch H, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Dengjel J: Global remodelling of cellular microenvironment due to loss of collagen VII. Mol Syst Biol 9: 657, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hageman RS, Leduc MS, Caputo CR, Tsaih SW, Churchill GA, Korstanje R: Uncovering genes and regulatory pathways related to urinary albumin excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 73–81, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneiders FI, Maertens B, Böse K, Li Y, Brunken WJ, Paulsson M, Smyth N, Koch M: Binding of netrin-4 to laminin short arms regulates basement membrane assembly. J Biol Chem 282: 23750–23758, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yebra M, Diaferia GR, Montgomery AM, Kaido T, Brunken WJ, Koch M, Hardiman G, Crisa L, Cirulli V: Endothelium-derived Netrin-4 supports pancreatic epithelial cell adhesion and differentiation through integrins α2β1 and α3β1. PLoS ONE 6: e22750, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiser J, Sever S, Faul C: Signal transduction in podocytes—spotlight on receptor tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 104–115, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Mackie EJ, Pearson CA, Sakakura T: Tenascin: an extracellular matrix protein involved in tissue interactions during fetal development and oncogenesis. Cell 47: 131–139, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varnum-Finney B, Venstrom K, Muller U, Kypta R, Backus C, Chiquet M, Reichardt LF: The integrin receptor alpha 8 beta 1 mediates interactions of embryonic chick motor and sensory neurons with tenascin-C. Neuron 14: 1213–1222, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broder C, Becker-Pauly C: The metalloproteases meprin α and meprin β: unique enzymes in inflammation, neurodegeneration, cancer and fibrosis. Biochem J 450: 253–264, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Broder C, Arnold P, Vadon-Le Goff S, Konerding MA, Bahr K, Müller S, Overall CM, Bond JS, Koudelka T, Tholey A, Hulmes DJ, Moali C, Becker-Pauly C: Metalloproteases meprin α and meprin β are C- and N-procollagen proteinases important for collagen assembly and tensile strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 14219–14224, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker-Pauly C, Barre O, Schilling O, Auf dem Keller U, Ohler A, Broder C, Schutte A, Kappelhoff R, Stocker W, Overall CM: Proteomic analyses reveal an acidic prime side specificity for the astacin metalloprotease family reflected by physiological substrates. Cell Proteomics 10(9): M111.009233, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kos CH, Le TC, Sinha S, Henderson JM, Kim SH, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, Gerszten RE, Pollak MR: Mice deficient in alpha-actinin-4 have severe glomerular disease. J Clin Invest 111: 1683–1690, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Girgert R, Martin M, Kruegel J, Miosge N, Temme J, Eckes B, Muller GA, Gross O: Integrin alpha2-deficient mice provide insights into specific functions of collagen receptors in the kidney. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair, 3: 19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hershkovitz D, Burbea Z, Skorecki K, Brenner BM: Fetal programming of adult kidney disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 334–342, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyata T, Kikuchi K, Kiyomoto H, van Ypersele de Strihou C: New era for drug discovery and development in renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 469–477, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z, Chen S, Boyle S, Zhu Y, Zhang A, Piwnica-Worms DR, Ilagan MX, Kopan R: The extracellular domain of Notch2 increases its cell-surface abundance and ligand responsiveness during kidney development. Dev Cell 25: 585–598, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niranjan T, Bielesz B, Gruenwald A, Ponda MP, Kopp JB, Thomas DB, Susztak K: The Notch pathway in podocytes plays a role in the development of glomerular disease. Nat Med 14: 290–298, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waters AM, Wu MY, Onay T, Scutaru J, Liu J, Lobe CG, Quaggin SE, Piscione TD: Ectopic notch activation in developing podocytes causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1139–1157, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brinkkoetter PT, Olivier P, Wu JS, Henderson S, Krofft RD, Pippin JW, Hockenbery D, Roberts JM, Shankland SJ: Cyclin I activates Cdk5 and regulates expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL in postmitotic mouse cells. J Clin Invest 119: 3089–3101, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ: Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science 294: 1866–1870, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morello F, de Boer RA, Steffensen KR, Gnecchi M, Chisholm JW, Boomsma F, Anderson LM, Lawn RM, Gustafsson JA, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ: Liver X receptors alpha and beta regulate renin expression in vivo. J Clin Invest 115: 1913–1922, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dessapt-Baradez C, Woolf AS, White KE, Pan J, Huang JL, Hayward AA, Price KL, Kolatsi-Joannou M, Locatelli M, Diennet M, Webster Z, Smillie SJ, Nair V, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Long DA, Gnudi L: Targeted glomerular angiopoietin-1 therapy for early diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 33–42, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takemoto M, Asker N, Gerhardt H, Lundkvist A, Johansson BR, Saito Y, Betsholtz C: A new method for large scale isolation of kidney glomeruli from mice. Am J Pathol 161: 799–805, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humphries JD, Byron A, Bass MD, Craig SE, Pinney JW, Knight D, Humphries MJ: Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci Signal 2: ra51, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS: Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20: 3551–3567, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R: A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 75: 4646–4658, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R: Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74: 5383–5392, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.