SUMMARY

During the development of peripheral nerves, pioneer axons often navigate over mesodermal tissues. In this paper, we examine the role of the mesodermal cell determination gene tinman on cells that provide pathfinding cues in Drosophila. We focus on a subset of peripheral nerves, the transverse nerves, that innervate abdominal segments. During wild-type embryonic development, the transverse nerve efferents associate with glial cells located on the dorsal aspect of the CNS midline (transverse nerve exit glia). These glial cells have cytoplasmic extensions that prefigure the transverse nerve pathway from the CNS to the body wall musculature prior to transverse nerve formation. Transverse nerve efferents extend along this scaffold to the periphery, where they fasciculate with projections from a peripheral neuron – the LBD. In tinman mutants, the transverse nerve exit glia appear to be missing, and efferent fibers remain stalled at the CNS midline, without forming transverse nerves. In addition, fibers of the LBD neurons are often truncated. These results suggest that the lack of exit glia prevents normal transverse nerve pathfinding. Another prominent defect in tinman is the loss of all dorsal neurohemal organs, FMRFamide-expressing thoracic structures which likely contain the homologs of the transverse nerve exit glia in the thoracic segments. Our results support the hypothesis that the exit glia have a mesodermal origin and that glia play an essential role in determining transverse nerve axon pathways.

Keywords: body wall muscles, lateral bipolar dendrite neuron, exit glia, FMRFamide, neurohemal organ, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Many studies have implicated glial cells in providing cues for pathfinding (Silver et al., 1982; Klämbt and Goodman, 1991). During the development of the vertebrate cerebral commissures, a ‘sling’ of glial cells is formed before the navigation of commissural axons to the contralateral side of the brain (Silver et al., 1982). This sling is later used as a bridge that allows the commissural axons to cross the midline. In the insect developing nervous system, specialized glial cells prefigure the pathway of the main axonal nerve tracts (Jacobs and Goodman, 1989; Klämbt and Goodman, 1991). Genetic or surgical ablation of these glial cells results in dramatic pathfinding defects (Bastiani and Goodman, 1986).

Mesodermal tissues also appear to be involved in the process of pathfinding and target recognition. For example, in the grasshopper limb bud, motorneuron growth cones are directed by undifferentiated muscle pioneers (Ball et al., 1985). This and other studies suggest that many of the cues required for proper establishment of connections are present on the surface of mesodermal cells. Interestingly, some glial cells may have a mesodermal origin as suggested by recent studies in Drosophila mesodermless mutants (Edwards et al., 1993).

Several genes that affect mesodermal cell determination have been identified in Drosophila. The zygotic transcriptional regulator genes twist and snail are required for early mesoderm determination (Alberga et al., 1987; Thisse et al., 1987). In the absence of these genes, mesoderm does not form, and gastrulation is severely disrupted. Two other genes, the homeobox genes tinman (tin) and bagpipe (bap), are involved in the subsequent early differentiation of mesoderm into visceral and somatic mesoderm (Bodmer et al, 1990; Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993; Bodmer, 1993). tin is downstream of twist and is required for the formation of visceral muscles, the heart and a subset of body wall muscles. bap depends on the expression of tin, and is also required for the formation of visceral muscles. The identification of these genes provides an opportunity to investigate the role of mesodermal tissues in pathfinding.

In this paper, we describe the development of the transverse nerves (TN), peripheral nerves that emerge from the CNS midline (Osborne, 1964). Prior to the formation of the TN, glial cells with long processes (TN exit glia) prefigure almost the entire TN pathway to the periphery. Later, these processes are followed by TN pioneering axons. In tin mutants, these exit glia are missing and the formation of the transverse nerves is severely disrupted. Dorsal neurohemal organs (DNH), which contain likely homologs of TN exit glia in the thoracic segments, are likewise absent in the mutant. Our observations in tin mutants suggest that TN exit glia are required for axon pathfinding, and that these glia and the support cells of DNH organs have a mesodermal origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Flies

Flies were raised at 25°C in a standard Drosophila medium. The strain Canton-S (CS) was used as wild-type. The tinman alleles tin346 and tin45, were obtained from M. Frasch, and tinEC40 from M. Pardue (characterized in Bodmer, 1993). A deficiency for the region 93C3-93F, Df(3R)eB52, was obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. A small deficiency that fails to complement tin, Df(3R)EX5 was generated by the excision of a P-element localized close to the tin gene. Studies were carried out using tin alleles over the two deficiencies or tin346/tinEC40. The anatomical and developmental analysis in wild type was based on 31 first instar and 40 embryonic samples. Characterization of tin was based on 15 first instar and 20 embryonic samples. Eggs were collected every 30 minutes from fly cages placed at 25°C. Embryos were then incubated at 18°C until desired stages (Johansen et al, 1989; Klämbt et al., 1991; Van Vactor et al., 1993). For studies in first instar larvae, larvae were collected 0–12 hours after hatching.

Immunocytochemistry

Larval body walls were processed for immunocytochemistry according to Gorczyca et al. (1993). Embryonic fillets were prepared as described in Halpern et al. (1991). The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-HRP (1:200–1:400; Sigma) to label axons and synaptic terminals (Jan and Jan, 1982), anti-fasciclin II (mAb 1D4; 1:5; gift of C. S. Goodman) to label axons in embryos (Seeger et al., 1993; Van Vactor et al., 1993), anti-ELAV to label neuronal nuclei (1:200; gift of K. White), and anti-FMRFamide (polyclonal PT4; 1:1000; gift of P. Taghert). Secondary antibodies were rhodamine- or FITC-conjugated IgGs at 1:120 dilution. To label muscles, FITC- or rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes) was used. Samples were observed under epifluorescence or confocal microscopy. Confocal images were processed using the NIH program Image.

Intracellular injections

Cells were viewed on an Zeiss Axiovert 35 under Nomarski optics using a 40× long working distance objective and electrophoretically filled (3 nA for 10 minutes) with 5% Lucifer Yellow (Sigma) as in Halpern et al. (1991), except that samples were prefixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5–30 minutes. Anti-Lucifer Yellow (1:200; Molecular Probes) immunocytochemistry was performed as above on some of the injected samples.

RESULTS

To study the role of mesodermal cells on pathfinding, we examined the development of the body wall muscle innervation in the mesodermal cell fate mutant tin. The body wall muscles of Drosophila larvae are composed of a regular array

Two putatively null tin alleles, tin346 and tinEC40, and a severe hypomorphic tin allele, tin45, were used for the present studies. These alleles were examined over deficiencies of the 93E region or in heteroallelic combinations. Similar results were obtained in all of these combinations supporting the notion that the phenotypes observed resulted from the loss of function of tin. The above tin alleles were reported to have an embryonic lethal phenotype (Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993; Bodmer, 1993) which included a distended midgut and the lack of several body wall muscles such as muscles 25, 7 and 5. In this study, we found that some tin homozygote embryos hatch and survive as first instar larvae, even though they have the midgut and body wall muscle defects. The mutants could be readily distinguished because they failed to grow, exhibited lethargic behavior and had very large midguts.

The expression of tin during embryonic development is restricted exclusively to mesodermal cells (Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993). Its expression is dependent upon the expression of the mesoderm-determining gene twi, and begins in the mesodermal cells that invaginate from the ventral midline during gastrulation. During later embryonic development, its expression becomes restricted to two sets of cells, one of which will become the visceral mesoderm, and the other the cells of the heart. There is no evidence reported of tin expression in cells of ectodermal origin (Bodmer et al, 1990; Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993).

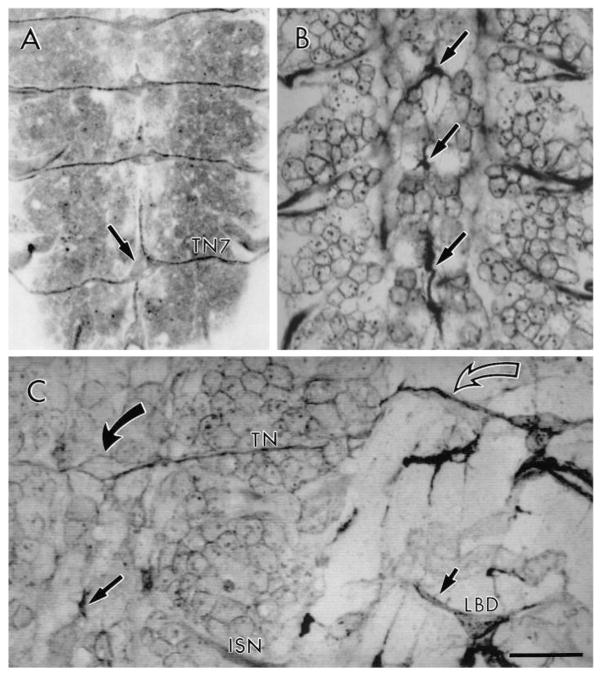

The transverse nerve is missing in tin larvae

The most conspicuous defect in tin mutant larvae was that most TNs were missing (Fig. 1; Table 1). In wild-type larvae, TNs can be readily visualized using anti-HRP antibodies, which stain neurons. The TN exits the CNS at its dorsal midline as an unpaired nerve, which then splits into a left and right branch (Fig. 1A). The anterior three TNs bifurcate close to their point of emergence whereas TNs 5–8 diverge much more distally, with TN 8 branching well down its pathway to the posterior regions of the body. Virtually all tin mutant larvae had few if any TNs (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Those TNs that remained were generally found in more posterior segments. When absent, the TN was replaced by a stump or a clump of short irregular fibers (Fig. 2B).

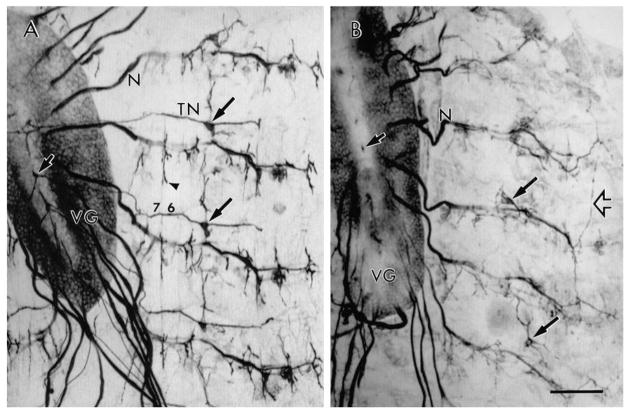

Fig. 1.

Innervation of the body wall muscles in wild-type and tin mutant first instar larvae as shown by anti-HRP immunocytochemistry. (A) View of wild-type body wall muscles and ventral ganglion (VG) showing TNs, ISNs and SNs (N), and innervation of body wall muscles (arrowheads). N also marks the first abdominal segment-A1. TNs never innervate A1. Muscles 6 and 7 are marked for reference. (B) View of body wall muscles and ventral ganglion in a tin45/Df(3R)eB52 sample showing the lack of TNs. Long arrows in A and B point to the LBD cell bodies. Short arrow points to a TN emergence site at the dorsal CNS midline. Open arrow in B points to an abnormal ISN fiber which crosses a segment boundary. In all figures up is anterior. Bar, 52 μm. of 30 muscle fibers per hemisegment (Crossley, 1978). Neuromuscular junctions of abdominal segments A2–A8 are innervated by two major nerves, the segmental (SN) and intersegmental (ISN) nerves, and one small peripheral nerve, the transverse nerve (described as the segment boundary nerve by Bodmer and Jan, 1987), that exit the CNS in a segmentally repeated pattern (Fig. 1A). The intersegmental nerve and the segmental nerve exit together from the dorsolateral aspect of the larval CNS while the TN exits from the CNS dorsal midline.

Table 1.

Peripheral nerves and DNH organs in wild-type and tin mutants as revealed by anti-HRP

| % DNH present | % TN present (A2–A8) | % LBD dorsal projections | % normal projections

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNa | SNb | ISN | ||||

| Control | 97 (n=39) | 100 (n=81) | 97 (n=77) | 100 (n=74) | 97 (n=71) | 100 (n=79) |

| tin346/Df | 2 (n=39) | 16 (n=86) | 13 (n=73) | 42 (n=70) | 11 (n=67) | 38 (n=70) |

n=hemisegments scored.

%=% of normal (nerves scored by examining innervation of muscles 6, 7, 12 and 13 for SNb, muscles 5 and 8 for SNa, and ISN scored by examining its trajectory towards the dorsal musculature.

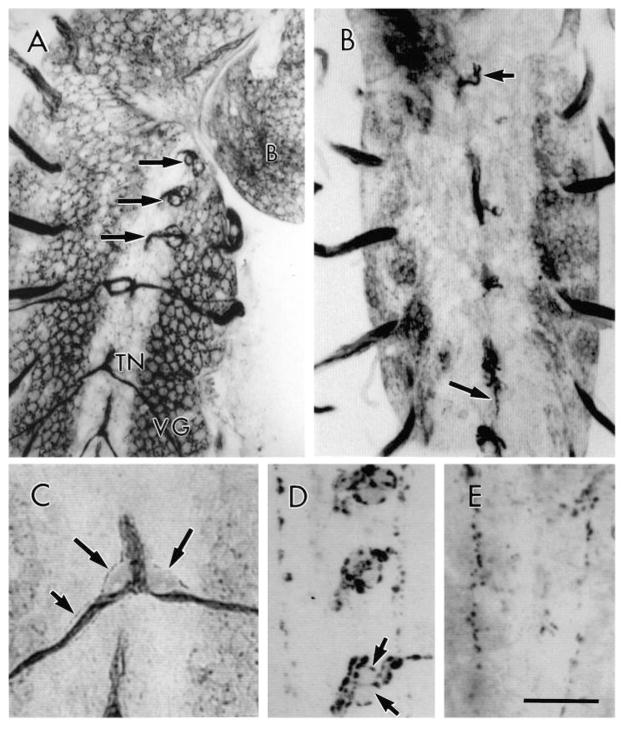

Fig. 2.

TN and DNH organ localization at the dorsal CNS midline in wild-type and tin larvae. (A) CNS dorsal midline in wild-type, showing the thoracic DNH organs (arrows), and the anterior TNs as they exit the CNS. (B) CNS dorsal midline in a tin45/Df(3R)eB52 showing the lack of TNs in abdominal segments (large arrow). Also note the presence of a small DNH remnant in T3 (small arrow). (C) View of a TN in a wild-type larva as it emerges from the CNS showing the exit glia (long arrows) close to the two TN branches. Short arrow points to a glial process around the nerve. (D) Dorsal view of the thoracic CNS midline showing FMRFamide-like immunoreactivity in the three DNH organs in wild-type. Arrows point to two support cells. (E) View of FMRFamide-like immunoreactivity in a similar region as in D in a tin mutant. Note the absence of FMRFamide-containing varicosities and support cells. VG, ventral ganglion, B, brain. Bar, 25 μm in A, 30 μm in B, 10 μm in C, and 18 μm in D,E.

At every branch point, the wild-type TN is associated with two cells, each of which is often found close to one arm of the branch (Fig. 2C). These cells stain dimly with anti-HRP, but adequately stand out against the fluorescence background. Lucifer Yellow injections into these cells showed that they displayed processes that extended down the nerves and presumably enwrapped them (not shown, but see Fig. 2C small arrow). We termed these cells TN exit glia because they resemble the previously described exit glia associated with the SN and ISN (Klämbt and Goodman, 1991). In tin, these exit glia were never observed on TN remnants or at their base.

DNH organs are also missing in tin

The thoracic CNS segments (T1–T3), like segment A1, lack TNs and muscle 25. However along the CNS dorsal midline, there is one dorsal neurohemal organ (DNH) per thoracic segment (Fig. 2A,D). DNH organs are composed of two dimly staining (with anti-HRP) cells that protrude from the midline, and which are linked to the CNS by a stalk. These cells are surrounded by varicosities of at least two axons that contain FMRFamide-like peptide (see below; White et al., 1986; Schneider et al., 1991).

Another prominent defect in tin mutants was the lack of DNH organs (Fig. 2B,E; Table 2). The two cells and the varicose endings were missing although, rarely, an axon or two would emerge from the dorsal CNS where the DNH organ should have been. At wild-type thoracic segments, 6 lateral FMRFamide-containing neurons (1 per thoracic hemisegment), termed Tv neurons, project toward the dorsal CNS midline and are believed to provide the FMRFamide-containing endings that innervate the DNH organs (see Schneider et al., 1991). In tin most of the Tv cells were missing or failed to exhibit FMRF immmunoreactivity (Table 2). On rare occasions when a DNH organ remnant developed (n=7), two immunoreactive Tvs were present in that segment.

Table 2.

% of expected FMRFamide-containing Tv neurons and DNH organs in tin mutants

| N† | No. of Tv | No. of DNH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected number* | – | 6 | 3 |

| Control** | 18 | 100% | 100% |

| tin346/Df(3R)eB52 | 30 | 40% | 13% |

| tin45/Df(3R)eB52 | 18 | 17% | 0% |

expected number/sample based in White et al. (1986) and this report.

controls are heterozygote TM3/Df(3R)eB52 or tin/TM3 samples.

number of thoracic segments analyzed.

The TN is required for normal LBD pathfinding

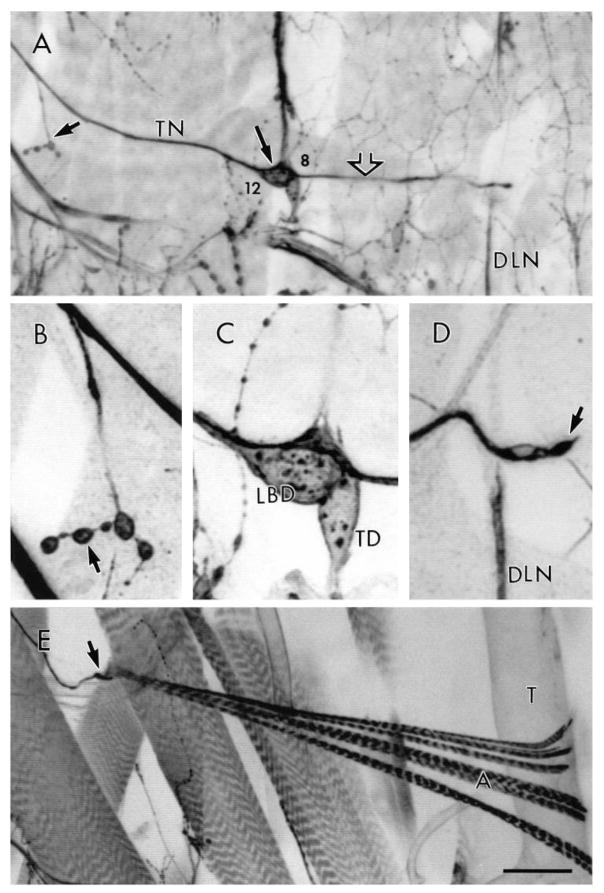

In wild type, each TN branch courses laterally over the dorsal CNS, then continues its path onto the ventral body wall musculature along the segmental boundary (Figs 1A, 3A). Just prior to the medial aspect of muscle 7, the TN branches off to innervate a small, deep body wall muscle (muscle 25; Fig. 3A,B). The TN continues over several other muscles at the intersegmental boundary, and reaches a prominent neuron cell body – the lateral bipolar dendrite cell (LBD, Figs 1A, 3A,C; Bodmer and Jan, 1987) – that rests on the posterior side of muscle 8, and is adjacent to another neuron, the tracheal dendrite (TD) neuron (Fig. 3C). After passing the LBD, the TN extends farther along the segment boundary and terminates slightly past the dorsal longitudinal ‘nerve’ (Bodmer and Jan, 1987) (Fig. 3A). The distal tip of the TN appears as a specialized ending (Fig. 3D,E) that contacts the base of the alary muscles (Rizki, 1978) and contains both typical motorneuron terminals as well as thick, neuritic endings. The latter are the dorsal termini of the LBD which may have a sensory or neuromodulatory function. It is not known if the motorneuron to the alary muscle travels the full length of the TN or if it merges with it at the level of the LBD. Lucifer Yellow dye fills (n=9) reveal that the LBD cell is a bipolar neuron that sends projections both dorsally to the end of the TN (not shown), and ventrally toward the CNS. The ventral projection was never seen to enter the CNS, but terminated part way up the TN, usually around muscle 7. In all fills, the dorsal projection reached the base of the alary muscles.

Fig. 3.

The TN visualized by HRP antibodies. (A) Trajectory of a first instar TN through the segment boundary showing the innervation onto muscle 25 (small arrow) and the LBD neuron (arrowhead). Open arrow points to the TN dorsal projection. Muscles 8 and 12 are marked as reference. (B) Innervation of muscle 25 by the TN. Arrow points to a synaptic bouton on muscle 25. (C) LBD and TD neurons. (D) TN dorsal tip (arrow) detached from alary muscle. (E) Connection of a 3rd instar TN dorsal tip (small arrow) with alary muscle (A). T, trachea; DLN, dorsal longitudinal nerve. Bar, 21 μm in A, 7 μm in B,C, 5 μm in D, and 70 μm in E.

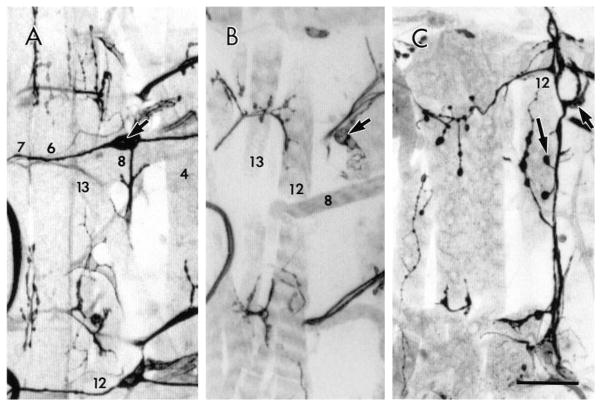

In tin, both the dorsal (distal end) and the ventral projection of the LBD neurons are disrupted (n=77) when the TN does not form (Figs 1B, 4B,C; Table 1). Ventrally extending processes were observed crossing segment boundaries and fasciculating with branches of the ISN or SN, or terminating on muscles such as fibers 8 or 12 with specialized endings that resemble the innervation of muscles by motorneurons (Fig. 4B,C). The less common cases where TNs were normal in tin (n=14; Table 1) were very informative in determining an interaction between LBD and TN, because there was a strong correlation between a normal TN and a normally projecting LBD. These observations suggest that the efferent TN fibers and/or the TN exit glial processes may be required for the proper pathfinding of the LBD projections.

Fig. 4.

Defective neuromuscular junctions in tin mutants. (A) Neuromuscular junctions in muscles 6, 7, 12, and 13 in two abdominal segments of a control first instar larva stained with anti-HRP. Note the pathway of the TN through the segment boundary, and the LBD cell body (arrow). (B,C) Examples of aberrant innervation of ventral longitudinal muscles in tin45/Df(3R)eB52. (B) Neuromuscular junctions in a tin sample lacking muscles 6 and 7. Arrow points to an LBD neuron which shows aberrant dorsal and ventral projections. Note the lack of a TN at the segment boundaries. (C) Abdominal body wall segments in a tin sample in which either muscle 6 or 7 was missing. Note the absence of a TN and the abnormal LBD (short arrow) ventral projection. Aberrant processes appear to innervate muscle 6 or 7. Long arrow points to abnormal nerve endings in the dorsal aspect of muscle 12. Normally, this muscle is only innervated at its ventral aspect (see A). Bar, 30 μm in A, 20 μm in B, and 25 μm in C.

TNs contain the efferent processes of the muscle 25 motorneuron. In tin, muscle 25 was often missing (Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993; this report), raising the possibility that its absence could be due to the lack of innervation. Although the absence of a TN was usually accompanied by a missing muscle 25, we did find three instances where the TN was missing but muscle 25 was present with no boutons on its surface. Therefore, it is likely that the frequent lack of innervation to muscle 25 is not the cause of its disappearance in tin mutants, and that innervation is not required for the survival of muscle 25.

Another clear phenotype of tin mutant larvae was the abnormal innervation of SNb target muscles (Fig. 4). This was often, but not always, associated with a loss of some muscle fibers. A common phenotype was the presence of ectopic innervation onto muscle 12 when muscle 5 was missing. (Fig. 4B). However, even when all muscles were present and appeared normal, the routes followed by motorneurons could be abnormal. Typically, a motorneuron would travel over the wrong face of the muscle or travel too far and then backtrack to its appropriate target. The other branches of the SN were not examined in detail in part because the junctions are deeper and obscured by other muscles. Another defect that was common in tin was a misrouting of the ISN (Fig. 1B). This was not examined in detail but was often noted to innervate aberrant regions, to terminate abruptly, or to cross to more anterior or posterior segments.

Development of the aberrant TN phenotype in tin embryos

To determine how the tin TN phenotype arose during development, wild-type and tin embryos were examined prior to the formation of the TN. In wild-type mid-stage 15 embryos, the growth cones that pioneer the TN have not yet exited to the surface of the CNS midline. However, two large cells are already located at the site of emergence of the TN prior to the arrival of its pioneer axons. These cells can be clearly seen in live or fixed dissected samples under Nomarski optics, because they have a characteristic morphology with long lateral processes, they are much larger than other cells present in the dorsal CNS midline and they are the dorsal most cells of the CNS midline. They could also be clearly identified in anti-HRP and anti-FAS II stained preparations, though they did not stain or they stained dimly with these antibodies. Staining with antibodies against the neuronal antigen ELAV (Robinow and White, 1991) showed that these cells were devoid of ELAV immunoreactivity. We confirmed our ability to identify them (Fig. 5A, B) by Lucifer Yellow intracellular fills (n=11). These segmentally repeated cells have been previously described (Caudy et al., 1986; Beer et al, 1987; Bodmer and Jan 1987; Montell and Goodman,1989; Nelson and Laughon, 1993), but their origin, fate and role in pathfinding had remained unclear (see discussion). Developmental analysis of increasingly older embryos and of first instar larvae revealed that these cells correspond to the TN exit glia (see below).

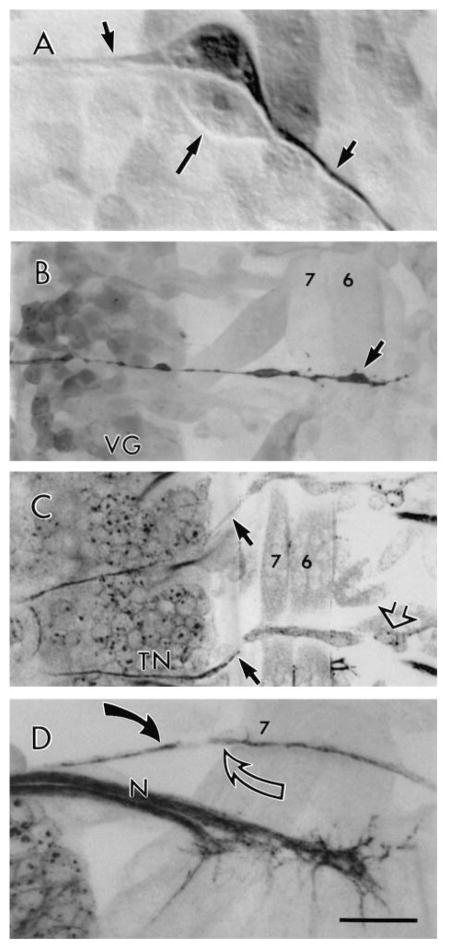

Fig. 5.

TN exit glia and development of the TN in wild type. (A) Intracellular Lucifer Yellow fill of one of the TN exit glia pair in an early stage 15 embryo showing its bipolar morphology (short arrows). Long arrow points to the other uninjected TN exit glia in that segment. (B) TN exit glia lateral process (arrow) revealed by anti-Lucifer Yellow immunocytochemistry of a filled TN exit glia. Note that the TN process leaves the dorsal CNS and travels along the body wall muscle segment boundary to muscle 6. VG, ventral ganglion. (C) Distal projection of the TN exit glia (small black arrows). Note that the TN glial processes extend from the CNS to the body wall. Also note that in the lower segment, TN pioneer axons are reaching the body wall in close association with the TN exit glia process. Open arrow points to an LBD neuron, whose projections are out of the plane of focus. (D) View of an abdominal segment in a late stage 16 embryo. At this stage the efferent TN fibers (black arrow) and the LBD ventral projections (open arrow) meet at the level of muscle 7. Bar, 7 μm in A, 17 μm in B, 21 μm in C, and 11 μm in D.

During stages 15 and 16, the TN exit glia are spindle shaped, with long and thin lateral processes that travel to the edge of the CNS (Figs 5A,B; 6A,C), and over to the segment boundary near muscle 7 up to the level of the LBD neuron cell body (Fig. 5C). TN exit glia are observed in abdominal segments A1 through A8, even though a TN never forms in A1 (not shown). The trajectory of the TN exit glia prefigures the pathway that is later to be followed by TN pioneer axons (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 6.

TN exit glia and axons in stage 16 wild-type (A) and tin (B,C) embryos. (A) TN exit glia in abdominal segments A4–A8 at stage 16. Note darkly stained (anti-Fas II) TN pioneer processes associated with TN exit glia lateral projections. (B) CNS dorsal midline in tin346/Df(3R)eB52 stage 16 mutant embryo. Note the lack of exit glia and the presence of short processes directed along the midline (arrows). (C) tin mutant embryo in which one of the TNs is normal (upper). In this segment the TN is completely formed, exit glia are present (curved black arrow), and LBD fibers (curved open arrow) are continuous with the TN. In the posterior (lower) segment, there are a few short fibers (long arrow) at the point of emergence of the TN, no TN exit glia are observed, and LBD fibers (short arrow) reach only to muscle 7. Bar, 22 μm in A, 17 μm in B, and 15 μm in C.

During late stage 15, the first TN growth cones contact the TN exit glia. These pioneer processes emerge between the anterior and posterior corner cells (aCC and pCC; Bastiani et al., 1985). The growth cones of the TN pioneer axons make contact with the TN exit glia cell bodies, and then split into a right and left branch that follow the lateral processes of the TN exit glia toward the lateral edge of the CNS. When the pioneer fibers leave the CNS (mid stage 16), they traverse the ventral body wall clinging to the exit glial process that extends along the segment border (Fig. 5C). At muscle 7, they contact centrally projecting fibers from the LBD neuron (Fig. 5D).

LBD cells are first visible with anti-HRP and anti-FAS II antibodies by early stage 15. At this time, the LBD soma is devoid of projections and localized to the posterior face of muscle 8, just dorsal to muscle 12. During late stage 15, LBD neurons start to extend both ventral and dorsal projections which can be specifically recognized by FasII antibody staining (unlike the TDs). By mid-stage 16, the ventral LBD projection, which travels along the insertion points of muscles 6 and 7 (segment boundary), encounters the efferent TN fibers (Fig. 5D).

In tin embryos, TN exit glia could not be found (Fig. 6B). We do not know if in the mutant these cells fail to differentiate or if they differentiate abnormally. In stage 16 tin embryos, the absence of the TN was always correlated to the absence of TN exit glia. In some tin samples, 1 or 2 TN would form normally (Table 1). On these occasions, TN exit glia could always be identified, and had a normal morphology (Fig. 6C).

Mutant embryos from early to late stage 16 were examined to see if TN pioneer growth cones could be identified in the absence of TN exit glia. TN growth cones were found in tin embryos but, unlike wild type, they appeared stalled at the surface of the CNS midline, even in embryos as old as late stage 16 (Fig. 6B, arrows). These stalled axons displayed a number of processes that ran in several directions along the CNS dorsal midline for a few tens of micrometers. Their corresponding LBD neuron extended processes to muscles 6/7 or had no centrally directed processes. In the few instances where a normal TN was formed in a tin embryo (Table 1), the LBD displayed a normal ventral projection (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that TN pioneer growth cones require TN exit glia to find their pathway to the periphery.

The idea that the exit glia are responsible for the TN pathway can also be supported by occasional instances of abnormal TN development in wild-type embryos. In one example, when an exit glia was aberrantly positioned close to an adjacent segment and its lateral processes exited through that segment, the TN followed it. In addition, its corresponding LBD neuron shifted its ventral projection into that posterior segment (not shown). Interestingly, the contralateral glial process traveled to its normal position and all aspects of TN and LBD morphology were normal on that side.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the role of a mesodermal cell fate gene, tin, on axon pathfinding in Drosophila embryos and larvae. Our major finding was that in tin mutants most TNs, as well as the larval DNH organs, were missing. The lack of TNs was accompanied by the absence of specialized glial cells, the TN exit glia. These glial cells prefigure the TN pathway before the emergence of the TN pioneer growth cones. In a similar manner, the loss of DNH organs was accompanied by the absence of their support cells.

We attribute the loss of TNs in tin mutants to missing exit glia. In tin, TN efferents appear at the dorsal surface of the CNS at the normal time, and their growth cones extend some distance down the midline. However, when the exit glia are missing, the TN efferents are unable to find their proper route off the CNS roof and remain at this location well into the first instar stage. In the few instances when exit glia are present in tin specimens, the TN efferents grow along the glial process and the TN forms normally. It is unlikely that the TN efferents are directly affected by tin, because tin expression is not found in cells of ectodermal origin and the TN behaves normally up until the time that it would meet the exit glia. In wild type, exit glia are fully formed well before the emergence of TN efferents whereas, in mutants, the glia do not appear even by the time of lethality in the first instar.

At least three different glial lineages have been described in Drosophila embryonic CNS (reviewed in Klämbt and Goodman, 1991). The longitudinal glia, which in embryos prefigure the CNS longitudinal tracts and which later form a sheath around them, arise from a glioblast in the ventral neurogenic region. The midline glia, which are required for the formation and separation of the commissures, arise from the mesectodermal region (Klämbt et al., 1991). Perineural glia, which form a sheath around the CNS, are suggested to be derived from mesodermal tissue as determined by analysis of mesodermless twi mutants (Edwards et al., 1993). Cell transplantation experiments have provided evidence that the TN exit glia are derived from mesoderm (Beer et al, 1987). Expression of tin has not been reported in the TN exit glia, in cells along the CNS, or in cells which are known to migrate to the CNS (Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993; Bodmer, 1993). However, the TN exit glia precursors or the exit glia themselves may express tin only in early development as do other mesodermal cells. A case in point is the somatic mesoderm which gives rise to the body wall musculature. tin is not expressed in this tissue after it has morphologically differentiated from the visceral mesoderm fairly early in development. Yet several body wall muscles fail to develop and many are abnormal in tin. The lack of tin expression in a fully differentiated mesoderm derivative does not rule out a direct effect on that cell.

Another interpretation of our results is that mesodermal tissues exert an inductive process over the dorsal surface of the developing CNS, allowing the differentiation or maintenance of TN exit glia. In tin the mesodermal cells that contribute to the formation of the midgut, and which develop in direct contact with the dorsal surface of the CNS, undergo a change in cell fate (Azpiazu and Frasch, 1993; Bodmer, 1993). In the absence of the normal cellular environment that surrounds the dorsal CNS, TN exit glia might not form or might degenerate.

In both grasshoppers and Drosophila, exit glia for the SN and ISN have been extensively described. These glial cells are located at the exit point of CNS peripheral axons, before these axons form during the embryonic period. Later the glia wrap around nerves forming a sheath (reviewed in Klämbt and Goodman, 1991). Our observation of TN exit glia extending long processes that prefigure the TN path, and that later are seen in close association with TN pioneer growth cones, suggests that they are important for pathfinding. Similar roles for glial cells have been documented in both vertebrate and invertebrate systems (Silver et al., 1982; Klämbt et al., 1991). During the development of Drosophila, midline glia are required for proper crossing of commissural axons to the contralateral side and for the separation of the commissures. In mutations such as star, rhomboid and spitz, in which these glia are absent or degenerate, commissures form abnormally or not at all (Klämbt et al., 1991). In the developing vertebrate nervous system, glial cells are also required for the formation of the cerebral commissures and for migration of neuronal precursors (Rakic, 1971; Silver et al., 1982).

Montell and Goodman (1989) have shown that cells similar to the TN exit glia described in this report express the extracellular matrix molecule laminin during the embryonic period (stage 15). This observation together with the evidence that glia are required for TN axon pathfinding, suggest a possible involvement of laminin in the guidance of the TN pioneer fibers. This would be consistent with studies in vertebrate systems, where laminin has been implicated in neurite outgrowth and cell migration (reviewed in Hynes and Lander, 1992).

In the study by Montell and Goodman (1989), it was suggested that these laminin immunoreactive cells might represent muscle pioneers. We do not believe that the TN exit glia are muscle pioneers, because the TN exit glia can be observed in late embryos as well as in larvae, well after all larval muscles are formed (Johansen et al., 1989; Bate, 1990). In addition, they do not serve as a scaffold for myocyte attachment. TN exit glia are also not likely to correspond to adult muscle precursors. Bate et al. (1991) and Broadie and Bate (1991) have studied the localization of adult muscle precursors. None of the adult muscle precursors that were identified resembled the TN exit glia. Beer et al. (1987) speculated that these cells were monopolar neurons. However, we view them as exit glia because (1) they lie at the point where pioneer axons exit the CNS, (2) in the embryonic period they form a scaffold over which pioneer axons extend, and (3) in the mature animal they appear to enwrap the TN, and define the TN branch point into a left and right arm. In Phormia, electron microscopy of these cells in late larvae clearly demonstrates glial cell morphology (Osborne, 1964). In addition, the present study indicates that the TN exit glia are not labelled by the actin-binding molecule phalloidin, their HRP staining is very light and distinct from that of neurons and they are not labelled by Elav antibodies. All these properties are characteristic of glial cells (see Klämbt and Goodman, 1991).

Carr and Taghert (1988) have studied the development of the TN homolog in Manduca. In the moth the TN arises from the dorsal CNS midline, and contains both motor and neuroendocrine axons. The TN motor axons in the moth innervate the closure muscles of the spiracles in each segment. In Drosophila and Phormia (Osborne, 1964), the TN is also an unpaired nerve. As in Manduca, the Drosophila TN carries at least one motor axon directly from the CNS, which in the fly, but not in the moth, innervates a single body wall muscle. This muscle is the only body wall muscle of segments A2–8 which is not innervated through either the ISN or SN. In Drosophila the TN terminates on the alary muscles which insert on pericardial cells. In Manduca, a cell with very similar morphology to the LBD, known as L1, contains neurosecretory granules in varicosities along its projections within the TN (Wall and Taghert, 1991) and terminates on the alary muscles and heart. Whether the fly LBD has a neurosecretory function is not known. However, the 8th segment TN contains a FMRFamide-like immunoreactive axon, and the DNH organs show allatotropin- and FMRFamide-like immunoreactivity (Zitnan et al., 1993; White et al., 1986).

The studies of Carr and Taghert (1988) on the development of the TN in Manduca are particularly enlightening. Similar to our studies, they found that, prior to the emergence of TN growth cones, there were two groups of non-neuronal cells, which they called the strap and the bridge, that anticipated the pathway of the TN. They also found that the TN pioneer growth cones navigated to the periphery in close association with these cells. They suggest that these cells are mesodermally derived. These results, together with studies in Drosophila and in grasshopper, suggest that the involvement of glial cells in establishing a blue print over which growth cones find their correct pathways is a common mechanism used by a wide variety of species.

Some of the neuromuscular junction defects found in tin mutants were targeting mistakes. In some cases, these defects might be accounted for by the lack of certain body wall muscles in tin. This is supported by the studies of Cash et al. (1992) in homeotic mutants (reviewed in Keshishian et al., 1993). In those studies, when abdominal segments were transformed into thoracic segments, certain abdominal-specific muscles, such as muscle 5, were missing. When this occurred, the motorneurons to muscle 5 innervated neighboring muscles, such as muscle 12, in ectopic regions. In tin mutants muscle 5 was often missing, and muscle 12 received ectopic innervation from the nerve that carries muscle 5 motorneurons. When all muscles were present, the inappropriate innervation in tin mutants might have been due to a change in muscle cell fate, in such manner that cell surface molecules required for normal target recognition (Van Vactor et al., 1993; Keshishian et al., 1993) were missing or misplaced. Another point that should be mentioned is that missing or abnormal body wall muscles or unidentified mesodermal derivatives in the body wall may also give rise to some of the SN and ISN defects that were observed.

In Drosophila larvae, the thoracic CNS segments are devoid of a TN. However, at similar CNS regions, there is a DNH organ composed of two weakly anti-HRP immunoreactive cells and extensive innervation by FMRFamide-containing fibers. Like the TN exit glia, the DNH organ cells are missing in tin. This raises the possibility that the DNH cells might be the TN exit glia homologs in the thoracic CNS. Unlike TN exit glia, they differentiate into neurosecretory organs, express the insect hormone allatotropin (Zitnan et al., 1993), and become innervated by FMRFamide-containing endings.

Interestingly in tin, the Tv neurons lack FMRFamide immunoreactivity. There was a strong correlation between the presence of a DNH organ remnant and the presence of FMRFamide immunoreactive Tvs. One explanation for this is that the innervation of DNH organs may be required for the survival of Tv neurons. Alternatively, the establishment or maintenance of FMRFamide might be innervation dependent in the DNH organs. The lack of Tv cells is not likely to be due to a general alteration in neuronal populations in tin, because the defect was rather specific to Tvs – other FMRFamide-containing neurons appeared normal.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the pathfinding of fibers in the TN requires the presence of normal exit glia on the dorsal surface of the CNS. In addition, the mesodermal cell fate gene tinman is required for the development of the exit glia. The defects observed in tin mutants demonstrate that the loss of these glia has wide ranging effects on the developmental cascade associated with the formation of the TN.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr R. Murphey, Dr J. Nambu, T. Lahey, and C. Augart for helpful comments on the manuscript and E. Chen for photographic assistance. We also thank Dr M. Frasch for the tin alleles, tin346 and tin45 prior to publication, and Dr M. Pardue for the tinEC40 allele. We are grateful to Drs. C. S. Goodman, P. Taghert, and K. White for their generous gift of antibodies and to Dr L. Schwartz for the use of his computer. We also express thanks to the reviewers for their insightful critiques of the manuscript. Supported by NIH grant NS30072 and an Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship to V. B.

References

- Alberga A, Boulay JL, Dennefeld C. The snail gene required for mesoderm formation in Drosophila is expressed dynamically in derivatives of all three germlayers. Development. 1987;111:983–992. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu N, Frasch M. tinman and bagpipe: two homeobox genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball EE, Ho RK, Goodman CS. Development of neuromuscular specificity in the grasshopper embryo: guidance of motorneuron growth cones by muscle pioneers. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1808–1819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-07-01808.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani MJ, Doe CQ, Helfand SL, Goodman CS. Neuronal specificity and growth cone guidance in grasshopper and Drosophila embryos. TINS. 1985;8:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani M, Goodman CS. Guidance of neuronal growth cones in the grasshopper embryo. III Recognition of specific glial pathways. J Neurosci. 1986;6:3542–3551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03542.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate M. The embryonic development of larval muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1990;110:791–804. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate M, Rushton E, Currie D. Cells with persistent twist expression are the embryonic precursors of adult muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1991;113:79–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer J, Technau G, Campos-Ortega J. Lineage analysis of transplanted individual cells in embryos of Drosophila melanogaster. Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1987;196:222–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00376346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R, Jan YN. Morphological differentiation of the embryonic peripheral neurons in Drosophila. Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1987;196:69–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00402027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R, Jan LY, Jan YN. A new homeobox-containing gene, msh-2, is transiently expressed early during mesoderm formation in Drosophila. Development. 1990;110:661–669. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1993;118:719–729. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadie K, Bate M. The development of adult muscles in Drosophila: ablation of identified muscle precursor cells. Development. 1991;113:103–118. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr J, Taghert P. Formation of the transverse nerve in moth embryos. I a scaffold of nonneuronal cells prefigures the nerve. Dev Biol. 1988;130:487–499. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash S, Chiba A, Keshishian H. Alternate neuromuscular target selection following the loss of single muscle fibers in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2051–2064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02051.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudy M, Jan NY, Jan L. Pioneer pathfinding of segment boundary nerves by identified cells in Drosophila embryos. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1986;12:196. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley C. The morphology and development of the Drosophila muscular system. In: Ashburner, Wright, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. 2b. Academic Press; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Swales L, Bate M. The differentiation between neuroglia and connective tissue sheath in insect ganglia revisited: the neural lamella and perineural sheath cells are absent in a mesodermless mutant of Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333:301–308. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca M, Augart C, Budnik V. Insulin-like receptor and insulin-like peptide are localized at neuromuscular junctions in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3692–3704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03692.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern M, Chiba A, Johansen J, Keshishian H. Growth cone behavior underlying the development of stereotypic synaptic connections in Drosophila embryos. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3227–3238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03227.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R, Lander A. Contact and adhesive specificities in the associations, migrations and targeting of cells and axons. Cell. 1992;68:303–322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90472-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN. Antibodies to horseradish peroxidase as specific neuronal markers in Drosophila and grasshopper embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;72:2700–2704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Goodman CS. Embryonic development of axon pathways in the Drosophila CNS. I A glial scaffold appears before the first growth cones. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2402–2411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02402.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen J, Halpern M, Keshishian H. Axonal guidance and the development of muscle fiber specific innervation in Drosophila embryos. J Neurosci. 1989;9:4318–4332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04318.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshishian H, Chiba A, Chang T, Halfon M, Harkins E, Jarecki J, Wang L, Anderson M, Cash S, Halpern M, Johansen J. Cellular mechanisms governing synaptic development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:757–787. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klämbt C, Goodman CS. The diversity and pattern of glia during axon pathway formation in the Drosophila embryo. Glia. 1991;4:205–213. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klämbt C, Jacobs J, Goodman CS. The midline of the Drosophila central nervous system. A model for the genetic analysis of cell fate, cell migration, and growth cone guidance. Cell. 1991;64:801–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90509-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell D, Goodman CS. Drosophila laminin: sequence of B2 subunit and expression of all three subunits during embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2441–2453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson H, Laughon A. Drosophila glial architecture and development: analysis using a collection of new cell-specific markers. Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1993;202:341–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00188733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne MP. The structure of the unpaired ventral nerves in the blowfly larva. Quart J Micr Sci. 1964;105:325–329. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Neuron-glia relationship during granule cell migration in developing cerebellar cortex: a golgi and electron microscopic study in Macacus rhesus. J Comp Neurol. 1971;141:283–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.901410303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki TM. The circulatory system and associated cells and tissues. In: Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. 2b. NewYork: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 397–452. [Google Scholar]

- Robinow S, White K. Characterization and spatial distribution of the ELAV protein during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:443–461. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M, Tear G, Ferres-Marco D, Goodman CS. Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila: genes necessary for for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron. 1993;10:409–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90330-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, O’Brien M, Taghert P. In situ hybridization analysis of the FMRFamide neuropeptide gene in Drosophila. I Restricted expression in embryonic and larval stages. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304:608–622. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J, Lorenz S, Wahlsten S, Coughlin J. Axonal guidance during development of the great cerebral commissures: descriptive and experimental studies, in vivo, on the role of preformed glial pathways. J Comp Neurol. 1982;210:10–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.902100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Stoetzel C, Messal M, Perrin-Schmitt F. Genes of the Drosophila dorsal group control the specific expression of the zygotic gene twist in presumptive mesodermal cells. Genes Dev. 1987;1:709–715. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vactor D, Sink H, Frambrough D, Tsoo R, Goodman CS. Genes that control neuromuscular specificity in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;73:1137–1153. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90643-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall JB, Taghert PH. Segment-specific modifications of a neuropeptide phenotype in embryonic neurons of the moth, Manduca sexta. J Comp Neurol. 1990;309:375–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.903090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Hurteau T, Punsal P. Neuropeptide FMRFamide-like immunoreactivity in Drosophila: development and distribution. J Comp Neurol. 1986;247:430–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitnan D, Frantisek S, Bryant PJ. Neurons producing specific neuropeptides in the central nervous system of normal and pupariation-delayed Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1993;156:117–135. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]