Abstract

Objective

Spiritually integrated psychotherapy (SIP) is increasingly common, though systematic assessment of interest in such treatments, and predictors of such interest, has not yet been conducted among acute psychiatric patients.

Methods

We conducted a survey with 253 acute psychiatric patients (95-99% response rate) at a private psychiatric hospital in Eastern Massachusetts, USA to assess for interest in SIP, religious affiliation, and general spiritual/religious involvement, alongside clinical and demographic factors.

Results

More than half (58.2%) of patients reported “fairly” or greater interest in SIP and 17.4% reported “very much” interest. Demographic and clinical factors were not significant predictors except that current depression predicted greater interest. Religious affiliation and general spiritual/religious involvement were associated with more interest, however many affiliated patients reported low/no interest (42%), and conversely many unaffiliated patients reported “fairly” or greater interest (37%).

Conclusions

Many acute psychiatric patients, particularly individuals with major depression, report interest in integrating spirituality into their mental health care. Assessment of interest in SIP should be considered in the context of clinical care.

Keywords: Spirituality, Religion, Culture, Patient Preferences

Introduction

Throughout world history, spirituality and religion have been powerful social forces shaping politics, family structure, and economics around the globe. More recently, it has also become apparent that these domains impact human health and healthcare (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). In particular, a considerable body of research now ties spiritual/religious life to mental health and functioning (Seybold, & Hill, 2001), and recent data underscores its clinical relevance both within the general population (Rasic, Robinson, Bolton, Bienvenu, & Sareen, 2011) and clinical samples across the lifespan (e.g., Dew et al. 2011; Rosmarin, Malloy, & Forester, 2014). Further, it is increasingly recognized that spirituality is important to individuals who utilize mental health services – in some studies, more than of 80% of psychiatric patients report drawing upon religion to cope with distress (Rosmarin, Bigda-Peyton, Öngur, Pargament, & Björgvinsson, 2013). These trends, coupled with an emphasis on patient-centered care by the National Institute of Health, have led to an important development within the field of psychotherapy: The growth of spiritually integrated psychotherapies (SIPs), which are psychosocial approaches that draw upon spiritual/religious content. Much like conventional psychotherapies, SIPs target various presenting problems such as depression (Propst, Ostrum, Watkins, Dean, & Mashburn, 1992), anxiety disorders (Rosmarin, Pargament, Pirutinsky, & Mahoney, 2010), and serious mental illness (Weisman de Mamani, Tuchman, & Duarte, 2010). While SIPs are not entirely new given that spirituality is a core component of 12-step interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous,1 utilizing spirituality in the context of treatment for non-substance-use disorders is indeed recent development. Further, empirical research on SIPs is growing at a rapid pace – over 40 controlled trials have been conducted in the past two decades (Rosmarin, Pargament, & Robb, 2010), and meta-analyses have demonstrated comparable efficacy relative to traditional approaches (McCullough, 1999).

While others have cogently articulated a rationale as well as methods for assessing and addressing patient spirituality in the context of treatment (e.g., Aten & Leach, 2009; Pargament & Krumrei, 2009), the promulgation of SIPs also raises concerns. Ethically speaking, SIPs should only be used with patients who desire such treatments (Pargament, 2007) – promotion of spiritually-based healthcare with patients whom are not interested in such approaches may constitute proselytization (Groopman, 2004). According to some estimates in American samples more than 55% of psychotherapy patients desire SIPs (Rose, Westefeld, & Ansely, 2001), but this may be a function of religious affiliation, general spiritual/religious involvement, geography (e.g., residence in the Southern United States, where religiousness is more common), or demographic factors such as older age, female gender, or ethnic minority status, all of which are associated with more spiritual/religious involvement (Pew Forum, 2008). It is possible that desire for spiritually-integrated treatment may be higher among patients with certain presenting problems/diagnoses such as mania and psychosis, which are commonly co-opted by spiritual/religious themes (Menezes, & Moreira-Almeida, 2010). We therefore examined the extent to which acute psychiatric patients professed interest in SIP, as well as demographic, clinical and religious predictors of interest.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

We administered a brief survey to 253 patients from a psychiatric day program over a period of 8-10 months. In order to prevent selective recruitment of patients with personal interest in spirituality, patients were initially solicited to participate in “a research study” without mention of the subject matter. Subsequently, prospective subjects were provided with an informed consent document that disclosed the nature of the study, and given the option to participate or withdraw. Less than 5% of subjects refused to participate prior to being informed about the nature of the study, and less than 1% of subjects provided with the informed consent document refused to participate. Demographic and clinical information were obtained from subjects’ clinical files, including diagnoses, which were conferred by a structured interview and consultation with a board certified psychiatrists. This study received Intuitional Review Board approval, all subjects provided written informed consent to participate and no monetary or other compensation was offered or provided. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1, and were largely consistent with the patient population in the study setting (Björgvinsson, Kertz, Bigda-Peyton, Rosmarin, Aderka & Neuhaus, 2014).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample.

| Demographics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age | M = 34.1, SD = 13.35, Range = 18-66 |

| Gender (Female) | n = 146, 57.7% |

| Race (White) | n = 215, 85.0% |

| Married | n = 53, 20.9% |

| College degree | n = 116, 45.8% |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Number of Current Diagnoses | M = 1.92, SD = 1.13, Range = 0-5 |

| Current Mood Disorder | n = 207, 81.8% |

| Current Anxiety Disorder | n = 140, 55.3% |

| Current Alcohol Use Disorder | n = 32, 12.6% |

| Current Psychotic Disorder | n = 14, 5.5% |

| Current Eating Disorder | n = 10, 4.0% |

| Lifetime Psychotic Disorder | n = 47, 18.6% |

| Previous Hospitalization | n = 138, 54.5% |

| High suicide risk | n = 93, 36.8 |

Notes: Overall n = 253; n = 16 patients presented with no current diagnosis, however n = 15 of these patients had a past Major Depressive Episode and all presented with significant suicidality. Current Mood Disorders include Major Depression (n = 159), Bipolar Disorder (n = 39), and Mood Disorder with Psychotic Features (n = 9). Mood, Anxiety, Alcohol Use, Psychotic, and Eating Disorders are not mutually exclusive groups. Previous hospitalization refers to past six months. Suicide risk was assessed with a structured interview (Sheehan, Lecrubier, Harnett-Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, et al., 1991).

Measures

Interest in Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy was assessed with the item “To what extent would you like to include your spirituality in your mental health treatment?” which was rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (anchors ranging from “Not at All” to “Very Much”). Prior to administration of this item, spirituality was defined as “a broad term that refers to any way of relating to that which is sacred, that may or may not be linked to established institutionalized systems,” and participants were provided with an opportunity to ask a trained interviewer any questions they had about this definition2.

Religious Affiliation was assessed with the item “What is your religious preference?” Open-ended responses were reviewed and coded by a research assistant into the following categories: Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Other or None.3

General Spirituality/Religion was assessed with a series of five items. Three items assessed for belief in God, importance of religion, and importance of spirituality, and each rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (anchors ranging from “Not at All” to “Very Much”). A fourth and fifth item, taken from the Duke Religion Index (Koenig, Parkerson Jr., & Meador, 1997) assessed for public and private religious activity, were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale with anchors ranging from “Rarely or Never” to “More than once a day”). In order to minimize the risk of Type-I errors in our main analyses we created a summary measure of general spirituality/religion4, using standardized scores (to ensure equal weighting across items). The resulting scale was internally consistent (α = .78) and all items loaded on a single factor, supported by a scree plot examination, with an eigenvalue of 2.43 and accounting for 60.7% of scale variance.

Analytic Plan

First, descriptive statistics were used to characterize levels of spiritual/religious involvement and interest in SIP in the sample overall. Subsequently, we conducted Pearson correlations and t-tests to examine demographic and clinical predictors of this variable. Finally, we utilized regression to evaluate the extent to which patient spirituality/religion was associated with interest in spiritually integrated treatment, controlling for significant demographic and clinical covariates. Bonferonni correction was employed for all multiple comparisons.

Results

Spiritual/religious characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. These figures appear somewhat lower than the surrounding region in that 82% of the population of Massachusetts professes “fairly” or greater belief in God, 30% attend religious services weekly or more frequently, and 61% pray on a weekly basis (Pew Forum, 2008).

Table 2. Spiritual/Religious Characteristics of the Sample.

| Religious Affiliation | |

| Catholic | n = 55, 21.7% |

| Protestant | n = 50, 19.8% |

| Jewish | n = 18, 7.1% |

| Buddhist | n = 13, 5.1% |

| Hindu | n = 2, 0.8% |

| Other | n = 15, 5.9% |

| None | n = 100, 39.5% |

| General Spiritual/Religious Involvement | |

| Affiliation (with any religious group) | n = 153, 60.5% |

| Belief in God (“fairly” or greater) | n = 179, 70.8% |

| Importance of Spirituality (“fairly” or greater) | n = 166, 65.6% |

| Importance of Religion (“fairly” or greater) | n = 116, 45.8% |

| Public Religious Activity (weekly or greater) | n = 122, 48.2% |

| Private Religious Activity (weekly or greater) | n = 206, 81.5% |

Notes: See text for description of items to assess for spiritual/religious characteristics. Please contact the authors for full distributions of spiritual/religious characteristics within the sample.

The distribution of interest in SIP in the sample is presented in Table 3. More than half (58.2%) of patients reported “fairly” or greater interest, and 17.4% reported “very much” interest (top anchor), however the modal response was “not at all” (n = 57, 22.5% of the sample). Interest in SIP was not associated with female gender, t(250) = 1.38, ns, greater age, r = .14, ns, geriatric age, t(250) = 0.55, ns, or by ethnicity (White vs. non-White), college education, homelessness, or marital status, t(249) ranging from .06-1.79, ns for all tests. On the whole, clinical characteristics were also unrelated to levels of interest in spiritually integrated psychotherapy. A non-significant trend was observed in that interest in spiritually integrated treatment was more common among patients with a current mood disorder, F(1,250) = 5.88, p = .08. Upon closer examination, we observed that this was specific to patients with Major Depression only (n = 159) and not patients with Bipolar Disorder (n = 39) or a Mood Disorder with psychotic features (n = 9); further, when tested alone, current Major Depression was significantly associated with interest in spiritually integrated mental health treatment, F(250, 1) = 8.09, p < .005. However, interest was not associated with the presence of a current anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, psychotic disorder, or eating disorder, F(1, 250) ranging from 0.08-4.19, ns. Interest was also not associated with number of current diagnoses, r = .124, ns, previous hospitalization, t(246) = 1.58, ns, or lifetime psychotic disorders, F(1, 250) = 0.78, ns. With respect to patient spirituality/religion, we observed that general spirituality/religion was associated with greater age on the whole r = .21, p < .001, but no other demographic or clinical factors. As such, we controlled for age as well as Major Depression in subsequent analyses.

Table 3. Interest in Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy among Acute Psychiatric Patients.

| Response | Frequency/Percentage |

| Very Much | 44 (17.4%) |

| Moderately | 51 (20.2%) |

| Fairly | 52 (20.6%) |

| Slightly | 48 (19.0%) |

| Not at All | 57 (22.5%) |

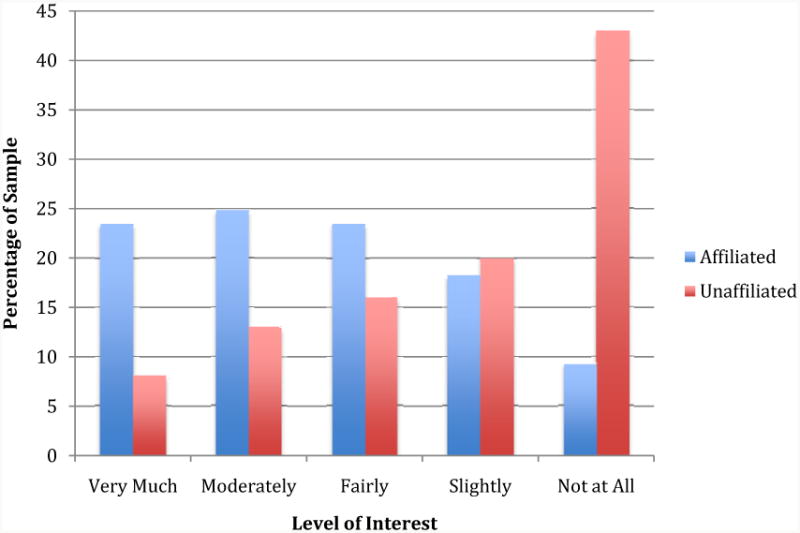

Both religious affiliation (i.e., with any religious group) and general spirituality/religion were significantly associated with interest in SIP (r2 = 0.14 for religious affiliation, and r2 = 0.45 for general spirituality/religion). While SIP was significantly greater among religiously affiliated patients, t(250) = 6.71, p < .001, more than one third (37%) of patients with no religious affiliation reported “fairly” or greater interest in SIP, and nearly one in twelve (8%) unaffiliated patients reported “very much” interest. Conversely, a sizable number of affiliated patients did not endorse interest (14% “not at all”; 28% “slightly”). See Figure 1. To explore these results further, we compared levels of interest between patients with high versus low spirituality/religion, using a mean-split from our general spirituality/religion summary index. Patients with high spirituality/religion reported significantly greater interest in spiritually integrated psychotherapy, t(250) = 11.64, p < .001. However, similar to affiliation, many patients with high levels of spiritual/religious involvement reported low interest in SIP (4.5% “not at all”; 9.7% “slightly”), and conversely, 27.7% of patients with low spirituality/religion reported “fairly” or greater interest in integrating spirituality into psychotherapy.

Figure 1. Interest in Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy among Religiously Affiliated and Unaffiliated Patients.

Notes. Religious affiliation (i.e., association with any religious group) was significantly associated with greater interest in spiritually integrated psychotherapy. However, a sizable number of affiliated patients did not endorse interest (14% “not at all”; 28% “slightly”). Conversely, 37% of patients without religious affiliation reported “fairly” or greater interest in integrating spirituality into their psychotherapy.

Discussion

In this study, levels of interest in SIP were quite high among acute psychiatric patients – more than half of those surveyed in this study endorsed fairly or greater interest. However, the distribution of scores was bi-modal with nearly a quarter (22.5%) of patients reporting no interest at all in SIP. Similarly, levels of spiritual/religious involvement were also high – over 70% of patients endorsed belief in God, and more than 60% professed religious affiliation. Yet, only 20-36% reported weekly religious activity – notably, these latter numbers are significantly less than national and even regional averages (Pew Forum, 2008). On the whole, these results suggest that spirituality plays an important role in the lives of a many psychiatric patients. Further, a large number of patients desire spiritually-integrated treatment, though for some patients this domain is neither desirable nor important. To this end, clinicians must be prepared to address spiritual issues in the context of patient care, when clinically indicated and desirable by patients to do so.

A second important finding from this study is that religious affiliation and general spirituality/religion were not synonymous with interest in SIP. While affiliation and spiritual involvement predicted greater interest with medium-to-large effect sizes, a sizable number of affiliated/involved patients (42%) reported little or no interest in SIP, and conversely many unaffiliated/uninvolved patients (37%) reported high interest in SIP. These results suggest that clinicians should not conclude on the basis of religious affiliation alone whether spirituality is or is not subjectively important to a given patient's mental health treatment. To this end, the current practice of solely assessing for religious affiliation (e.g., “Do you identify with a religious group?”) during a consultation appears to be insufficient. At a minimum, a starting point for addressing patient spirituality should include asking the following two questions of all patients, irrespective of their spiritual identity or lack thereof: (1) To what extent is your spirituality relevant to your presenting problem? (2) To what extent would you like to include your spirituality in your mental health treatment?

We were surprised to find that interest in SIP was not associated with certain known demographic correlates of spiritual life including greater age, female gender, and non-White race. The lack of a correlation between age (measured both continuously, and categorically as geriatric vs. non-geriatric) may reflect a spiritual resurgence among younger Americans that some have noted in recent years (Newport, 2003). Alternatively, or perhaps additionally, it should be recognized that mindfulness and meditation – both of which have a clear spiritual/religious origins (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) – are now a common and increasingly utilized in psychotherapy (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, Oh, 2010). While these are typically delivered in a secular way without explicit reference to spirituality or religion, their widespread popularization may nevertheless create greater openness to SIP among younger patients.

We were also surprised that clinical factors on the whole were not associated with interest in SIP, with the notable exception that current Major Depression predicted greater interest. Cognitive symptoms of depression often include loss of hope and meaning in life, and there are robust ties between religious coping and depressive symptoms (e.g., Koenig, et al., 1992). To this end, it is possible that spirituality – which often conveys themes of hope and meaning – may have particular appeal to individuals with depression. Indeed. It is also notable that depression is the most studied target in clinical trials of SIP, with many promising results. The lack of association between mania/psychosis and interest in SIP was also surprising given that a large literature has discussed the relevance of spirituality/religion to these symptom clusters (Mohr, Brandt, Borras, Gilliéron, Huguelet, 2006). These results may suggest that the extant literature has overemphasized the relevance of religion to certain symptom clusters at the expense of others, and that more attention to spiritual/religious factors across a broader range of diagnostic categories is warranted.

Limitations of this study include a demographically homogenous sample that originated from a single clinical program. However, the geographic location of the study – Eastern Massachusetts – likely provided for conservative evaluation of interest in SIP among acute psychiatric patients in the United States. This sample was also diagnostically heterogeneous, however this allowed for additional analyses comparing interest in SIP among specific diagnostic groups, and the naturalistic setting increases potential generalizability of findings. Study measures were also limited in that a single item was used to assess for interest in SIP and methods for integrating spirituality into treatment were not operationalized. Further research using more nuanced approaches to assess for how patients wish spirituality to be addressed is warranted. However, our results nevertheless suggest that many patients desire SIP and it is thus incumbent upon our field to identify evidence-based approaches to facilitate the integration of patient spirituality into psychotherapy.

Acknowledgments

David H. Rosmarin, Ph.D. affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. Financial support for this study was received from the Gertrude B. Nielsen Charitable Trust, and the Tamarack Foundation, the Rogers Family Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health (K23 077287-01A2) and the Harvard Catalyst Pilot Grant Program.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Public Health Significance: This study suggests that many patients desire spiritually-integrated psychotherapy. Furthermore, many religiously affiliated patients report low interest, and conversely many unaffiliated patients report high interest.

Alcoholics Anonymous has existed since the early 20th Century.

Given the heterogeneous nature of spirituality, previous research has utilized focus groups and other iterative methods to assess for interest in SIP (e.g., Arnold, Avants, Margolin, Marcotte, 2002). Our approach was admittedly less nuanced, but viewed as necessary given our study design and statistical approach.

Only responses of n = 2 or greater were coded as separate categories.

Initially, all five general spirituality/ religion items were entered into a factor analysis with Direct Oblimin rotation, however the resulting pattern matrix yielded an uninterpretable two-factor structure in which frequency of public religious activity loaded by itself on a separate factor. Thus, we conducted a second factor analysis including the remaining four items.

References

- Arnold RM, Avants SK, Margolin A, Marcotte D. Patient attitudes concerning the inclusion of spirituality into addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23(4):319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aten JD, Leach MM, editors. Spirituality and the therapeutic process: A comprehensive resource from intake to termination. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton J, Rosmarin DH, Aderka I, Neuhaus E. Effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for severe mood disorders in an acute naturalistic setting: A benchmarking study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2014;43(3):209–220. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.901988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew RE, Daniel SS, Goldston DB, Mccall WV, Kuchibhatla M, Schleifer C, et al. Koenig HG. A prospective study of religion/spirituality and depressive symptoms among adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;120(1-3):149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman J. God at the Bedside. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(12):1176–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(2):169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Jr, Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research: A 5-item measure. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Pieper C, Meador KG, Shelp F, et al. DiPasquale B. Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(12):1693–1700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME. Research on religion-accomodative counseling: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(1):92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes A, Jr, Moreira-Almeida A. Religion, spirituality, and psychosis. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2010;12(3):174–179. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr S, Brandt PY, Borras L, Gilliéron C, Huguelet P. Toward an integration of spirituality and religiousness into the psychosocial dimension of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1952–1959. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. Americans say more religion in U.S. would be positive. 2013 Jan 1; Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/video/162860/americans-say-religion-positive.aspx.

- Pargament KI. Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Krumrei EJ. Clinical assessment of clients' spirituality. In: Aten JD, Leach MM, editors. Spirituality and the therapeutic process: A comprehensive resource from intake to termination. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Forum. Pew research religion & public life project: Religious landscape survey. 2008 Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report-religious-landscape-study-full on September 8, 2014.

- Propst LR, Ostrom R, Watkins P, Dean D, Mashburn D. Comparative efficacy of religious and nonreligious cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of clinical depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(1):94–103. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose EM, Westefeld JS, Ansely TN. Spiritual issues in counseling: Clients' beliefs and preferences. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48(1):61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Bigda-Peyton JS, Öngur D, Pargament KI, Björgvinsson T. Religious coping among psychotic patients: Relevance to suicidality and treatment outcomes. Psychiatry Research. 2013;210(1):182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Malloy MC, Forester BP. Spiritual struggle and affective symptoms among geriatric mood disordered patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29(6):653–660. doi: 10.1002/gps.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Pirutinsky S, Mahoney A. A randomized controlled evaluation of a spiritually- integrated treatment for subclinical anxiety in the Jewish community. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(7):799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Robb HB., III Spiritual and religious issues in behavior change: Introduction. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(4):343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Seybold KS, Hill PC. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(1):121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview. Journal of Clinical Psychiatryc. 59(20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman de Mamani AG, Tuchman N, Duarte EA. Incorporating religion/spirituality into treatment for serious mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(4):348–357. [Google Scholar]