Abstract

IL-7 is known to be vital for T cell homeostasis but has previously been presumed to be dispensable for TCR-induced activation. Here, we show that IL-7 is critical for the initial activation of CD4+ T cells in that it provides some of the necessary early signaling components, such as activated STAT5 and Akt. Accordingly, short-term in vivo IL-7Rα blockade inhibited the activation and expansion of autoantigen-specific CD4+ T cells and, when used to treat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), prevented and ameliorated disease. Our studies demonstrate that IL-7 signaling is a prerequisite for optimal CD4+ T cell activation and that IL-7R antagonism may be effective in treating CD4+ T cell-mediated neuroinflammation and other autoimmune inflammatory conditions.

Keywords: IL-7, T cells, EAE, Signaling pathways

1. Introduction

CD4+ T cell homeostasis is highly dependent on the availability of several cytokines, especially IL-7 [1]. A member of the IL-2 cytokine family, IL-7 binds the IL-7R complex to initiate signaling cascades that induce anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members, enhance glycolysis and other metabolic processes, and promote T cell survival [2–9]. Not surprisingly, deficiency in either IL-7 or its receptor is characterized by severe lymphopenia [10,11]. TCR engagement also activates multiple signaling cascades, some of which overlap with, or can be separately triggered by, IL-7 [3,4]. Upon T cell stimulation, IL-7Rα (CD127) is downregulated over several days [12] and thus IL-7 is not currently thought to play a direct role in antigen-induced T cell activation [10, 11]. Whether IL-7 and TCR signals synergize during initial CD4+ T cell priming and activation events is still unclear, although concurrent IL-7 and TCR signals appear to be required for lymphopenia-induced homeostatic T cell proliferation, a process similar to antigen-induced proliferation [13–15].

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a CD4+ T cell-mediated autoimmune disorder of the CNS characterized by inflammation, demyelination and progressive decline of motor and sensory functions [16]. The etiopathogenesis of this disease is incompletely defined, but genetic and environmental factors have been implicated [16,17]. Several myelin-associated autoantigens have been identified in MS and its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), but development of therapies aimed at the specific elimination of autoreactive CD4+ T cells has proved challenging [16]. As in other autoimmune diseases, current treatments are broadly immunosuppressive, exhibit limited effectiveness, and are associated with significant adverse effects [18,19]. Notably, high IL-7 serum levels and association with certain IL7RA allelic variants have been reported in MS patients [20–22]. Moreover, inhibition of IL-7R signaling reportedly reduced disease severity in the monophasic MOG and the relapsing/remitting PLP models of EAE [23]. Interestingly, disease reduction by IL-7R blockade was also observed in other autoimmunity models, including lupus [24], type I diabetes [25,26] and collagen-induced arthritis [27].

Our studies of the role of IL-7 in EAE provided strong evidence that IL-7 is required for efficient activation and expansion of CD4+ T cells, and that cross-talk between IL-7R and TCR signaling decreases the activation threshold in low-affinity autoreactive T cells. Importantly, short-term in vivo treatment with blocking anti-IL-7Rα antibody induced apoptosis of autoreactive CD4+ T cells undergoing activation with minimal effects on naïve cells, indicating that antigen-engaged clonotypes at early stages of activation are particularly sensitive to IL-7 withdrawal. Consequently, treatment with anti-IL-7Rα antibody ameliorated disease in the PLP139–151-induced relapsing/remitting model of EAE regardless of whether this treatment was applied at early or late stages of the disease.

2. Methods

Our study was designed to investigate the role of IL-7 in antigen-dependent CD4 T cell activation and neuroinflammation using in vitro and in vivo approaches. For each study, individual mice were randomized in different groups and analyzed under identical experimental conditions, but the experimenters were not blinded to the group identities. Estimation of group sizes to achieve statistically significant measurements was based on previous in vitro and in vivo experiments without calculation by power analysis.

2.1. Mice

SJL mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), C57BL/6 mice were obtained from The Scripps Research Institute, C57BL/6 IL-7−/− and C57BL/6 Ly5a+ mice were provided by Dr. Charles Surh and C57BL/6 Bcl-2 transgenics (B6Bcl-2) by Dr. Bruce Beutler. Thy1.1 5B6 PLP139–151 TCR transgenic mice and STAT5b-CA mice expressing constitutively active STAT5 have been described [28]. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions and all procedures approved by The Scripps Research Institute's Animal Research Committee (La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.2. CD4+ T cell activation and FACS

Splenocytes from PLP-specific TCR transgenic mice were pretreated with either anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibodies (0–250 μg/ml) for up to 1 h and cultured with or without rIL-7 (0–1000 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of PLP (0–100 μg/ml) or plate-bound anti-CD3 (0–10 μg/ml) plus soluble anti-CD28 (5 μg/ml) for up to 7 days. In instances where PLP transgenic T cells were not used, T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus soluble anti-CD28 antibodies as indicated. All cell culture densities for these in vitro assays were ≤200,000 cells/well. CD4+ T cells were analyzed by FACS using antibodies to Vβ6 (PLP-transgenic CD4+ T cells), CD4, CD25, CD69, CD127, and Bcl-2. CFSE analysis was performed as described [29]. For T cell signaling analysis, splenocytes were activated with PLP and stained with the indicated antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies or BD PharMingen). Mononuclear cell subset characterization of thymus, BM, spleen, and CNS was determined by FACS using commercially-available antibodies (BioLegend, eBiosciences, BD PharMingen). Active caspase 3 and 8 positive CD4+ T cells were identified according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cell Technology). For intracellular cytokine assessments, cells were incubated with PLP139–151 (20 μg/ml) in the presence of monensin (BioLegend) for 5 h, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antibodies to IL-2, IL-17, IFN-γ or TNF-α (all from BioLegend), and analyzed by FACS. All FACS data were acquired on an LSR II and analyzed by FloJo software.

2.3. Relapsing EAE induction and treatment protocols

Standard protocols were followed for induction of relapsing EAE (R-EAE) and adoptive transfer with polarized TH1 cells in SJL mice [23,30]. Anti-IL-7Rα antibody (clone A7R34; rat IgG2a) was produced at the Scripps Antibody Core facility and administered to mice i.p. 3 times per week at 200 μg/injection. A rat IgG2a isotype antibody (clone RTK2758; BioLegend) specific for KLH was similarly administered to control mice. Anti-IL-7 antibody (clone M25) was provided by Dr. Charles Surh, and an additional anti-IL-7Rα antibody (clone SB/199) was purchased from eBioscience. All antibodies were azide-free and contained <0.1 endotoxin units/μg of antibody (Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate test).

2.4. T cell proliferation and cytokine analysis

Splenocyte cultures were stimulated with PLP139–151 (10 μg/ml) for 72 h, [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation, and IL-2, -10, -17 and IFN-γ levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA (BioLegend).

2.5. Adoptive transfer of PLP-specific transgenic T cells

Recipient SJL mice (Thy1.2, 7–9 mice/group) were immunized with PLP139–151 to induce EAE, and simultaneously transferred i.v. with FACS-purified naive (CD62Lhi) CD4+ T cells (3.5 × 106 cells/mouse) from Thy1.1 5B6 PLP131–151 TCR transgenic mice. At the first sign of disease (day 10), mice were randomized in two groups, one receiving the anti-IL-7Rα antibody and the other the isotype control antibody. Five days later, Thy1.1 PLP139–151-specific T cells were isolated from the CNS [31], restimulated with PLP131–151 (10 μg/ml) peptide plus human IL-2 (5 ng/ml) and intracellular cytokine expression determined. For CFSE analysis, R-EAE was induced or not in Thy1.2 SJL mice as above and, on day 10, naïve (CD62Lhi) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1 PLP131–151 TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells were transferred i.v. (5 × 106 cells/mouse) and anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibodies were injected i.p. twice (days 10 and 12). Three days later, division of the transferred PLP-specific T cells was defined by CFSE dilution.

2.6. Statistical analysis

EAE severity scores are given as the average of the treatment group per day and were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. All other group mean comparisons were assessed using Student's t-test. Incidence was calculated using Fisher's exact test. Group mean area under the curve (AUC) values for disease fold reduction determinations and statistical analyses were calculated using Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Anti-IL-7Rα blocks activation of CD4+ T cells

IL-7 is essential for the development and long-term survival of CD4+ T cells, but whether it is necessary for antigen-induced activation is unclear. To address this question, total splenocytes from 5B6 transgenic mice expressing a low-affinity PLP-specific TCR [32,33] were treated for 1 h with either a blocking anti-IL-7Rα (clone A7R34) or an isotype control antibody (anti-KLH) and then stimulated with PLP139–151 peptide in the presence or absence of rIL-7. Notably, anti-IL-7Rα antibody treatment almost completely inhibited upregulation of activation markers (CD69 and CD25) (Fig. 1A) and proliferation (Fig. 1B) of the transgenic CD4+ T cells. Defective activation was associated with increased apoptosis (Fig. 1C) and failure to induce BCL-2 (Fig. 1D). Anti-IL-7Rα antibody added concurrent to stimulation yielded similar results, but when added >24 h post-TCR stimulation did not hinder expression of CD69 and CD25, indicating that IL-7 was only required during the initial phase(s) of T cell activation. Similar results were obtained using the low-affinity OVA323–339 peptide-specific OT-II TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells, i.e. markedly reduced responses to OVA peptide in the presence of anti-IL-7Rα antibodies.

Fig. 1.

IL-7 is required for CD4+ T cell activation. (A) Receptor-blocking anti-IL-7Rα antibodies inhibit antigen-induced upregulation of activation markers on naïve PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells. Shown are histograms of CD69 or CD25 cell-surface levels at 1, 2 and 7 days post-treatment with the indicated stimuli and antibodies. (B) Reduced PLP-specific CD4+ TCR transgenic T cell proliferation in the presence of anti-IL-7Rα antibodies and APCs. Proliferating cells were identified by FACS via CFSE-dilution. (C) Treatment with anti-IL-7Rα (blue) but not control (red) antibodies causes increased apoptosis of PLP-TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells 48 h following PLP stimulation. (D) The presence of anti-IL-7Rα (blue), but not control (red), antibodies inhibits upregulation of Bcl-2 in PLP-TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells stimulated with PLP up to 4 days. Day 4 is depicted. For panels A-D, splenocytes from PLP-TCR transgenic mice were pretreated with anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibodies (25 μg/ml each), cultured with or without IL-7 (10 ng/ml) as indicated, and stimulated with PLP (10 μg/ml). All FACS plots are gated on CD4+ T cells. Horizontal bars in A and B indicate activated or proliferating cells, respectively. The data are representative of 3–6 independent experiments.

Inhibition of activation by anti-IL-7Rα antibody was not the result of direct antibody-mediated cytotoxicity or apoptosis since unstimulated CD4+ T cells, untreated or treated for up to 7 days with anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibody, had equivalent viability. Complete inhibition of PLP-induced activation was also observed when transgenic CD4+ T cells were stimulated in the presence of another anti-IL-7Rα antibody clone (SB/199, rat IgG2b) or the Fab fragment of the anti-IL-7Rα antibody (A7R34). Moreover, a neutralizing anti-IL-7 antibody (M25, rat IgG2b) showed similar inhibitory activity (Fig. S1). Thus, at the time of antigen stimulation, IL-7 is critical for the optimal activation and survival of low-affinity CD4+ T cells.

3.2. CD4+ T cells from IL-7-deficient mice exhibit impaired activation

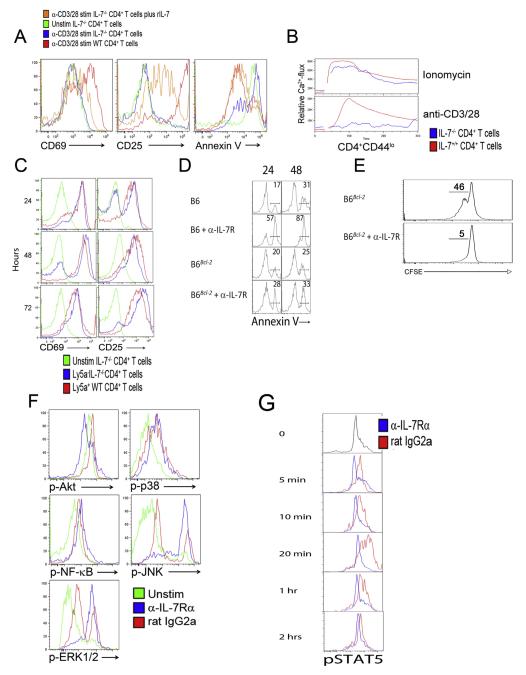

Next, we analyzed activation responses of CD4+ T cells from IL-7-deficient mice. Similar to findings with the anti-IL-7Rα antibody, anti-CD3/CD28 antibody-stimulated IL-7−/− CD4+ T cells showed markedly reduced upregulation of CD69 and CD25 (Fig. 2A, left and middle panels) and increased apoptosis (Annexin V+) (Fig. 2A, right panel) 48-hour post-stimulation. Naive CD4+ T cells from these mice also failed to mobilize Ca2+ in response to TCR triggering (Fig. 2B). The reduced response of IL-7−/− CD4+ T cells is likely not due to an intrinsic defect as previously postulated [10] since activation could be significantly restored by the addition of rIL-7 (Fig. 2A) or co-culture with total IL-7-producing splenocytes from wild-type (WT, Ly5a) mice (Fig. 2C). Moreover, treatment of these mixed splenocyte cultures with anti-IL-7Rα suppressed activation of both IL-7−/− and WT CD4+ T cells. Therefore, defective activation of CD4+ T cells from IL-7−/− mice is due to lack of IL-7-mediated costimulation. Taken together, experiments with anti-IL-7Rα and anti-IL-7 antibodies, or with IL-7-deficient mice, uniformly suggest that IL-7 is required for initial CD4+ T cell activation, proliferation, and survival.

Fig. 2.

STAT5 and Akt phosphorylation in CD4+ T cell activation requires IL-7. (A) Inefficient activation and increased apoptosis of TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells from IL-7−/− mice are corrected by rIL-7 treatment. Splenocytes from WT (red) or IL-7−/− (blue) mice were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 h. CD69 and CD25 cell-surface levels and Annexin V positivity were determined on CD4+ T cells by FACS. Addition of rIL-7 (10 ng/ml, orange) prevented apoptosis (Annexin V upregulation) of IL-7−/− CD4+ T cells and restored activation. Green lines, unstimulated IL-7−/− CD4+ T cells. (B) CD4+ T cells from IL-7−/− mice (blue) mobilize Ca2+ after ionomycin but not anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. CD4+ T cells from WT mice (red) were used as positive control. (C) Wild-type splenocytes restore TCR-activation of CD4+ T cells from IL-7−/− mice in mixed cultures. Splenocytes from Ly5a−IL-7−/− and Ly5a+ WT mice were mixed 1:1 and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. CD69 and CD25 expression on gated Ly5a−IL-7−/− (blue) and Ly5a+ WT (red) CD4+ T cells was determined by FACS. Green lines, unstimulated IL-7−/− CD4+ T cells. (D) Transgenic Bcl-2-expression rescues CD4+ T cells from IL-7R blockade-dependent activation-induced cell death (AICD). WT or Bcl-2 transgenic C57BL/6 splenocytes were pretreated with anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibodies and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. Annexin V expression was analyzed on CD4+ T cells every 24 h for 96 h (24 and 48 hour time points are depicted). Numbers indicate % cells in the respective gate. (E) The Bcl-2 transgene fails to restore TCR-induced CD4+ T cell proliferation in the presence of anti-IL-7Rα antibodies. (F) PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells show a stress phenotype in the presence of anti-IL-7Rα antibodies. Splenocytes from PLP-TCR transgenic mice were treated with anti-IL-7Rα or isotype antibodies and stimulated with PLP. Time points up to 2 h were analyzed by FACS for phosphorylation (activation) of Akt, p38, NF-κB p65, JNK, and Erk1/2. Histograms depict the 20 min time point, when isotype-treated control cells reached maximal activation. Blue, IL-7Rα antibody-treated CD4+ T cells; red, isotype-treated CD4+ T cells; green, unstimulated CD4+ T cells. (G) TCR stimulation induces STAT5 phosphorylation in an IL-7-dependent manner. Splenocytes from PLP-TCR transgenic mice were treated with anti-IL-7Rα or isotype antibodies (25 μg/ml each) and stimulated with PLP (10 μg/ml). CD4+ T cells were analyzed at the indicated time points by FACS for STAT5 phosphorylation (activation). Blue, IL-7Rα antibody-treated cells; red, isotype-treated cells. All data are representative of 3–5 independent experiments.

3.3. IL-2 cannot substitute for IL-7 in CD4+ T cell activation

To determine whether IL-2 could replace IL-7 in T cell activation, we added increasing concentrations of rIL-2 to PLP-stimulated TCR-transgenic splenocyte cultures containing the blocking anti-IL-7Rα antibody. Similar to cultures without rIL-2, no activation of CD4+ T cells was observed up to 250 ng/ml (Fig. S2). Thus, the requirement for IL-7 at early stages of activation cannot be overcome by excess IL-2, a finding consistent with the low expression of the high-affinity IL-2Rα (CD25) on naive CD4+ T cells [12].

3.4. BCL-2 does not reverse anti-IL-7Rα inhibition of T cell activation

To test whether IL-7Rα blockade inhibited T cell activation by simply interfering with the pro-survival effects of IL-7, we performed survival and proliferation experiments with total splenocytes from BCL-2 transgenic mice. BCL-2 transgenic CD4+ T cells were protected from activation-induced cell death (AICD) following TCR engagement in the presence of anti-IL-7Rα antibodies (Fig. 2D). Importantly, however, BCL-2-overexpression did not restore TCR-induced proliferative responses of anti-IL-7Rα antibody-treated CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2E).

3.5. IL-7 signaling activates STAT5 and Akt following TCR engagement

We next sought to identify the main signaling pathways affected by IL-7Rα blockade in PLP-stimulated TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells. Strikingly, anti-IL-7Rα antibody treatment resulted in persistent hyperphosphorylation of JNK and Erk1/2, but markedly reduced phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 2F). This activation profile resembles that of cells highly stressed from IL-7 withdrawal [34]. In contrast, NF-κBp65 phosphorylation was equivalent in both treatment groups, indicating that NF-κB activation is IL-7-independent. Notably, anti-IL-7Rα antibody also strongly inhibited TCR-induced STAT5-phosphorylation (Fig. 2G). To directly demonstrate that STAT5 activation via IL-7 is required for CD4+ T cell activation, purified CD4+CD25− T cells from STAT5b-CA mice expressing constitutively activated STAT5 [35] were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence or absence of anti-IL-7Rα antibody. Anti-IL-7Rα antibody-treated CD4+ T cells upregulated CD25 and CD69, indicating that constitutive STAT5 activation is sufficient to rescue T cell activation in the absence of IL-7 signaling (Fig. 3). Thus, IL-7 is critical for the induction of the PI3K/Akt pathway, STAT5 phosphorylation, and Ca2+ mobilization, and ensuing optimal T cell activation.

Fig. 3.

Constitutive STAT5 phosphorylation compensates for the lack of IL-7 signaling during CD4+ T cell activation. Purified CD4+CD25− T cells from C57BL/6 and STAT5-CA transgenic mice were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 72 h in the presence or absence of anti-IL-7Rα antibody (25 μg/ml). CD4+ T cells were analyzed by FACS for acquisition of the activation markers CD25 and CD69. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

3.6. Blockade of IL-7 signaling eliminates recently activated autoreactive T cells

The requirement of IL-7 at the early phase of antigenic stimulation of CD4+ T cells strongly suggest that IL-7R blockade would preferentially interfere with survival and expansion of recently activated T cells during ongoing in vivo immune responses, including against self-antigens. To test this possibility, we utilized the EAE model of SJL mice immunized with the PLP139–151 peptide [30,32], in which T cell re-activation in the CNS is required for inflammation [16,36]. Naive (CD44low CD62Lhi) Thy1.1 PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells were CFSE labeled and transferred into Thy1.2 SJL recipients at day 10 post-EAE induction. These mice were then treated or not with anti-IL-7Rα antibody (2 injections/3 days, beginning at the time of cell transfer), to determine whether brief treatment would preferentially induce apoptosis of antigen-engaged CD4+ T cells. We observed a >90% reduction in the number of antigen-engaged but not yet dividing (CFSEhi) transgenic CD4+ T cells in anti-IL-7Rα-treated mice compared to the isotype-antibody control group (0.6 ± 0.2 × 105 vs. 6 ± 2 × 105; p < 0.001; Fig. 4A), with most of the remaining IL-7Rα-blocked CFSEhi transgenic cells being preapoptotic (Fig. 4B). In sharp contrast, this short-term treatment had no measurable effects on the numbers of host polyclonal CD4+ T cells. Moreover, parallel transfer of CFSE-labeled PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells into naïve SJL hosts showed no reduction of these cells after anti-IL-7Rα treatment up to 7 days (Fig. 4C). Thus, in vivo, short-course of IL-7Rα blockade primarily affects survival and expansion of recently-engaged CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 4.

IL-7Rα blockade in vivo induces preferential elimination of antigen-stimulated autoreactive CD4+ T cells. (A) Antigen-engaged PLP-specific CD4+ TCR transgenic T cells are mostly eliminated from LN and spleen in SJL mice undergoing EAE and treated for a short time with anti-IL-7Rα (blue line) compared to isotype control antibody (rat IgG2a, red line). Naive (CD44low CD62Lhi) Thy1.1 PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells (Thy1.1, CD90.1) were CFSE labeled and transferred into SJL recipients (Thy1.2) at day 10 post-EAE induction. These mice were then treated or not with anti-IL-7Rα antibody (200 μg, 2 injections/3 days, starting at the time of cell transfer), and LN and spleen cells were harvested and analyzed by FACS. n = 4–5 mice/group; p < 0.001. Insets depict plots at smaller Y-axis scale to better visualize CFSE dilution. (B) Anti-IL-7Rα antibody treatment of EAE mice induces apoptosis of transferred PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells. Undivided (CFSEhi) TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells from panel A were analyzed by FACS for Annexin V positivity. n = 4–5 mice/group; p < 0.001. (C) Anti-IL-7Rα antibody treatment does not induce loss of PLP-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells in unimmunized (non-EAE) SJL recipients. Cell transfer and treatments were as detailed in panel A. (D) Effector PLP-specific CD4+ TCR transgenic T cells also require IL-7 signaling. Naive PLP-specific CD4+ TCR transgenic T cells (Thy1.1, CD90.1) were transferred into SJL recipients (Thy1.2) simultaneously with EAE induction (day 0). After disease appearance (day 10; EAE severity score ≥ 1), these mice were treated with anti-IL-7Rα or control antibodies (200 μg, 3 injections/5 days), and LN and spleen cells were harvested and analyzed by FACS using antibodies to CD4 and CD90.1 to identify donor cells. n = 3–4 mice/group; p < 0.01. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments.

3.7. Effector CD4+ T cells also require IL-7 signaling

Since IL-7Rα expression by CD4+ T cells is reacquired several days after activation (fig. S3) [12], we examined whether effector CD4+ T cells are also IL-7-dependent. We transferred naive PLP-specific CD4+ TCR transgenic T cells (Thy1.1) into SJL recipients (Thy1.2) simultaneously with EAE induction (day 0). After allowing for transgenic T cell expansion and early disease manifestations (day 10; EAE severity score ≥ 1), we administered anti-IL-7Rα or control antibodies (3 injections/5 days). There was a significant reduction of CNS-infiltrating transgenic CD4+ T cells in the anti-IL-7Rα antibody-treated mice, and fewer of these cells expressed IL-2, IL-17, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (Table S1). In addition, anti-IL-7Rα – treated mice showed a >65% reduction in the number of PLP-specific CD4+ T cells in spleen (34 ± 2 × 104 vs. 11 ± 1 × 104; p < 0.01) (Fig. 4D), with the majority of these cells undergoing apoptosis (75% Annexin V+ Thy1.1 versus 19% Thy1.2). These results strengthen the conclusion that, compared to unstimulated cells, recently activated as well as re-engaged effector CD4+ T cells are critically dependent on IL-7 during early activation and undergo apoptosis if deprived of this vital signal.

3.8. IL-7R blockade reduces EAE incidence and severity

The requirement for IL-7 during T cell activation led us to assess the effectiveness of IL-7Rα blockade in the relapsing/remitting model of EAE in which both TH1 and TH17 CD4+ cells have been implicated [16,23,37]. We initially administered anti-IL-7Rα or control antibody (200 μg 3 days a week i.p. until study termination) simultaneously with immunization of SJL mice with PLP139–151-peptide, and observed a delayed onset as well as significantly decreased (>5-fold) incidence and severity of disease in the anti-IL-7Rα-antibody-treated group compared to controls (Fig. 5A and B). After 2 weeks of antibody treatment, there was also a striking decrease in CNS-infiltrating mononuclear cells (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells > 20-fold, B cells > 100-fold, monocytes > 4-fold, and DCs > 40-fold; Table S2), a higher percentage of apoptotic CD4+ T cells in the periphery (Annexin V+ 32 ± 3% vs. 12 ± 4%, p ≤ 0.05; and activation of caspases 3 and 8, Fig. 5C), decreased in vitro responses to PLP, and reduced IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-17 production (Fig. S4). Consistent with the known IL-7 requirement for T cell development and survival, this prolonged treatment resulted in reductions of thymic and peripheral T cell subsets (Table S2), but had no effects on regulatory T cells (CD4+CD25+−FoxP3+), which have been reported to express very low levels of IL-7Rα [38,39]. Overall, these results indicate that in vivo IL-7R blockade has significant effects on EAE and associated inflammatory responses.

Fig. 5.

Relapsing/remitting EAE is attenuated by IL-7Rα blockade. (A) Incidence and (B) severity of PLP-induced R-EAE in SJL mice is significantly reduced by administration of anti-IL-7Rα (open circles) compared to isotype control antibody (closed circles). n = 8–11 mice/group; p < 0.001. (C) Increased conversion of procaspases 3 and 8 to active caspases in CD4+ T cells obtained two weeks after R-EAE induction from anti-IL-7Rα antibody-treated mice (blue line) compared to controls (red line). n = 8–11 mice/group; p < 0.01. (D) Incidence and (E) severity of R-EAE induced in SJL mice by transfer of polarized TH1 cells were reduced by treatment with anti-IL-7Rα antibody (open circles) compared to isotype antibody (closed circles). n = 5–8 mice/group; p < 0.001. (F) Incidence and (G) severity of PLP-induced R-EAE is reduced if anti-IL-7Rα antibodies are administered at the start of acute disease (day 8). n = 8–11 mice/group; p < 0.001 from days 8–35. (H) Incidence and (I) severity of relapses in PLP-induced R-EAE mice are reduced when anti-IL-7Rα antibody treatment is initiated prior to the first relapse (day 20). n = 8–11 mice/group; p < 0.001 from days 20–35. R-EAE was induced in young female SJL mice either by injection of PLP peptide in CFA plus PTX (A, B, F, G, H, and I) or by adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells obtained from PLP-immunized SJL donors and polarized in vitro with PLP and IL-12 to TH1 cell type (D and E). Arrows indicate initiation of anti-IL-7Rα or isotype control antibody treatment (200 μg, 3 times/week). Data are expressed as either daily group means (incidence) or mean ± SEM (EAE Severity Score), and are representative of 3–5 independent experiments.

Blockade of IL-7Rα also effectively reduced EAE incidence and severity (>4-fold) in SJL recipients adoptively transferred with polarized Th1-type PLP-specific CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5D and 5E), indicating that EAE-mediating Th1 cells are highly sensitive to IL-7Rα blockade. Of direct clinical relevance, we found that IL-7Rα blockade was very effective in averting disease progression in PLP-induced EAE even when applied after the first signs of disease (day 8) (Fig. 5F and G) or at the early stages of relapse (day 20) (Fig. 5H and I), with pathologic manifestations rapidly resolving after treatment initiation without further recurrence.

4. Discussion

The study reported herein shows that IL-7 is a cofactor required for optimal activation of CD4+ T cells at the early stages of antigen engagement, and that its absence renders TCR signaling incomplete, leading to impaired expression of activation markers and increased apoptosis. We also show that a brief in vivo treatment with anti-IL-7Rα antibody results in preferential depletion of recently activated autoreactive CD4+ T cells without significant effects on polyclonal naïve T cells. Moreover, antibody-mediated IL-7Rα blockade ameliorated EAE regardless of the disease stage at which treatment was initiated. These findings indicate that IL-7 acts as an accessory factor for efficient T cell activation, and that inhibition of signaling by this cytokine may effectively reduce neuroinflammatory and other autoimmune responses.

The reliance of CD4+ T cell activation on IL-7 is likely due to an overlap in components of the signaling cascades initiated by TCR and IL-7. After TCR stimulation, many signaling molecules and pathways are simultaneously engaged that aid in cellular activation and proliferation, including Zap-70, PLCγ-1, Ca2+ flux, NF-κB, MAPK, Akt (via Lck and PI3K), STAT5, and Erk [4]. Activation of PI3K triggers both Ca2+ mobilization via activation of Tec family kinases and PLCγ [40,41], and also results in phosphorylation of Akt, which promotes survival by inducing anti-apoptotic factors such as BCL-2 [42]. On the other hand, IL-7 activates Jak1 and Jak3, leading to phosphorylation and translocation of STAT5 to the nucleus and expression of several genes critical for T cell activation, such as Cd69, Il2ra, and bcl-2 [43–45]. Our findings indicate that modulation of several key pathways during CD4+ T cell activation, specifically those involving PI3K/Akt, STAT5, Ca2+ flux and, to a lesser extent, JNK and Erk1/2, are dependent on IL-7 signaling. Thus, IL-7Rα blockade likely impairs T cell activation and proliferation by limiting the PI3K/Akt cascade as well as STAT5 phosphorylation. This result is consistent with an earlier study showing that activated STAT5 was required for antigen-induced T cell proliferation, although STAT5 phosphorylation was attributed to CD3ζ-Lck-dependent TCR signaling [43]. However, the present findings indicate that STAT5 phosphorylation following TCR engagement is dependent on concurrent IL-7R-mediated signals. Thus, by directly activating several key signaling molecules, IL-7 appears to critically synergize with TCR signals, leading to efficient CD4+ T cell activation and protection from activation-induced cell death. A priming effect of IL-7 or IL-15 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to suboptimal stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 or RA-associated autoantigens has been reported by others and attributed to amplification of Erk phosphorylation [46]. IL-7 has also been shown to synergize with other cytokines, such as IL-21 and IL-18, and promote proliferation of CD8+ T cells [47,48].

IL-7Rα is transiently downregulated over a period of several days during which time the high-affinity IL-2Rα is upregulated [12]. Interestingly, IL-2 could not compensate for IL-7 at the early stages of T cell activation when the IL-7R is highly expressed. These findings suggest that IL-7 provides immediate post-stimulation signals necessary for the activation and survival of CD4+ T cells, and that these survival signals are independent of those provided by IL-2 at later stages of T cell activation and expansion.

IL-7 is known to promote T cell survival by increasing expression or function of the pro-survival proteins BCL-2, BCL-XL and MCL1, and reducing the cell death-promoting proteins BAX, BAD and BIM [49–51]. Interestingly, in IL-7-deficient mice enforced expression of BCL-2 greatly increased T cell development and survival [52,53] but failed to correct homeostatic proliferation [13]. Our results are consistent with these findings by demonstrating that a Bcl-2 transgene protected in vitro TCR-stimulated T cells from IL-7 withdrawal but did not restore proliferation. These data clearly indicate that IL-7 has a distinct function in promoting efficient T cell activation and proliferative responses, independent of its prosurvival effect.

The pathogenic contribution of IL-7 has been documented in several autoimmune syndromes, and diverse mechanisms have been implicated. Our earlier studies in the MRL-Faslpr lupus model showed that disease progression was associated with excess IL-7 resulting from the combined effects of increased production by fibroblastic reticular cells and reduced consumption by the expanding CD4−CD8− double-negative T cells, which permanently downregulated the IL-7R. Consequently, disease was inhibited by IL-7R blockade [24]. Similarly, a high serum concentration of IL-7 was shown to correlate with Th1-driven MS, and treatment with anti-IL-7 or anti-IL-7R antibodies reduced disease in EAE models [23]. Disease reduction was also shown in EAE mice deleted of the Il7ra gene [54,55], although this effect might be a reflection of severe lymphopenia in these mice. Nonetheless, in one of these studies evidence was presented that IL-7R expression in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells is required for disease expression [54,55]. Other autoimmune diseases reportedly reduced by antibody-mediated IL-7R blockade include type I diabetes in NOD mice, attributed to upregulation of the inhibitory molecule PD-1 on effector T cells [25,26], and collagen-induced arthritis [27].

The present study provides direct evidence that inhibition of EAE and likely other autoimmune syndromes by IL-7R blockade is primarily due to inefficient T cell activation, which requires the coordinate action of both TCR and IL-7 signaling pathways. Hence, deprivation of autoreactive T cells from the IL-7 accessory signal leads to disease amelioration whether applied at the early or late stages of EAE, and even at the initiation of relapses. This treatment caused significant reductions in CNS-infiltrating Th1 and Th17 cells, the dominant pathogenic cell types in EAE and MS. It was also effective in reducing disease upon transfer of differentiated Th1 cells, suggesting that IL-7 is required not only for Th1 cell differentiation [23] but also for the effector functions of these cells. Especially important for clinical applications was the finding that short-term anti-IL-7R antibody treatment primarily eliminated recently activated autoreactive T cells while sparing non-engaged T cells. A potential explanation for this differential effect might be that naïve T cells require IL-7 intermittently, as indicated by the transient IL-7R downregulation following IL-7 engagement [12,50,56]. In contrast, at the initiation of T cell activation, IL-7 is required for effective TCR signaling as well as for the induction of survival and metabolic pathways necessary for cell division and expansion. Thus, a therapeutic effect to avert disease recurrence in autoimmunity could be achieved with a short treatment without broader adverse effects on thymopoiesis or T cell repertoire composition.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate that IL-7 is not merely a T cell trophic factor but an active partner required for optimal TCR-mediated CD4+ T cell activation. This costimulatory function of IL-7 is mediated by a set of signaling components that appear to converge with those induced by TCR. The coordinate action of these two signaling pathways may be particularly required for the expansion of low-affinity autoreactive T cells. Thus, interference with IL-7 signaling is likely to be applicable to the treatment of a wide spectrum of autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This is manuscript number 29180 from the Department of Immunology and Microbial Science of The Scripps Research Institute. We would like to thank M. Kat Occhipinti for editorial assistance, and John Scatizzi, Dilki Wichramarachchi, and Tannaz Hasnat for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grant AR065919 from the NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2015.08.007.

References

- [1].Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of naive and memory T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kittipatarin C, Khaled AR. Interlinking interleukin-7. Cytokine. 2007;39:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.07.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Palmer MJ, Mahajan VS, Trajman LC, Irvine DJ, Lauffenburger DA, Chen J. Interleukin-7 receptor signaling network: an integrated systems perspective. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2008;5:79–89. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jiang Q, Li WQ, Aiello FB, Mazzucchelli R, Asefa B, Khaled AR, Durum SK. Cell biology of IL-7, a key lymphotrophin. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:513–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Jacobs SR, Zhao Y, Rathmell JC. IL-7 promotes Glut1 trafficking and glucose uptake via STAT5-mediated activation of Akt to support T-cell survival. Blood. 2008;111:2101–2111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Johnson SE, Shah N, Bajer AA, LeBien TW. IL-7 activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway in normal human thymocytes but not normal human B cell precursors. J. Immunol. 2008;180:8109–8117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barata JT, Silva A, Brandao JG, Nadler LM, Cardoso AA, Boussiotis VA. Activation of PI3K is indispensable for interleukin 7-mediated viability, proliferation, glucose use, and growth of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:659–669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jacobs SR, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC. IL-7 is essential for homeostatic control of T cell metabolism in vivo. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3461–3469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chehtane M, Khaled AR. Interleukin-7 mediates glucose utilization in lymphocytes through transcriptional regulation of the hexokinase II gene. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C1560–C1571. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00506.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maraskovsky E, Teepe M, Morrissey PJ, Braddy S, Miller RE, Lynch DH, Peschon JJ. Impaired survival and proliferation in IL-7 receptor-deficient peripheral T cells. J. Immunol. 1996;157:5315–5323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].von Freeden-Jeffry U, Vieira P, Lucian LA, McNeil T, Burdach SE, Murray R. Lymphopenia in interleukin (IL)-7 gene-deleted mice identifies IL-7 as a nonredundant cytokine. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1519–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dooms H, Wolslegel K, Lin P, Abbas AK. Interleukin-2 enhances CD4+ T cell memory by promoting the generation of IL-7R alpha-expressing cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:547–557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan JT, Dudl E, LeRoy E, Murray R, Sprent J, Weinberg KI, Surh CD. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seddon B, Zamoyska R. TCR and IL-7 receptor signals can operate independently or synergize to promote lymphopenia-induced expansion of naive T cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3752–3759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Seddon B, Tomlinson P, Zamoyska R. Interleukin 7 and T cell receptor signals regulate homeostasis of CD4 memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:680–686. doi: 10.1038/ni946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:683–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Holmoy T. Immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: concepts and controversies. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2007;187:39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gold R. Combination therapies in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl. 1):51–60. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-1008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Steinman L, Martin R, Bernard C, Conlon P, Oksenberg JR. Multiple sclerosis: deeper understanding of its pathogenesis reveals new targets for therapy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:491–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gregory SG, Schmidt S, Seth P, Oksenberg JR, Hart J, Prokop A, Caillier SJ, Ban M, Goris A, Barcellos LF, Lincoln R, McCauley JL, Sawcer SJ, Compston DA, Dubois B, Hauser SL, Garcia-Blanco MA, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL. Interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) shows allelic and functional association with multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ng2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].C. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics. Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory SG, Rioux JD, McCauley JL, Haines JL, Barcellos LF, Cree B, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lundmark F, Duvefelt K, Iacobaeus E, Kockum I, Wallstrom E, Khademi M, Oturai A, Ryder LP, Saarela J, Harbo HF, Celius EG, Salter H, Olsson T, Hillert J. Variation in interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) influences risk of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1108–1113. doi: 10.1038/ng2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee LF, Axtell R, Tu GH, Logronio K, Dilley J, Yu J, Rickert M, Han B, Evering W, Walker MG, Shi J, de Jong BA, Killestein J, Polman CH, Steinman L, Lin JC. IL-7 promotes T(H)1 development and serum IL-7 predicts clinical response to interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002400. (93ra68) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gonzalez-Quintial R, Lawson BR, Scatizzi JC, Craft J, Kono DH, Baccala R, Theofilopoulos AN. Systemic autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation are associated with excess IL-7 and inhibited by IL-7Ralpha blockade. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lee LF, Logronio K, Tu GH, Zhai W, Ni I, Mei L, Dilley J, Yu J, Rajpal A, Brown C, Appah C, Chin SM, Han B, Affolter T, Lin JC. Anti-IL-7 receptor-alpha reverses established type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by modulating effector T-cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:12674–12679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203795109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Penaranda C, Kuswanto W, Hofmann J, Kenefeck R, Narendran P, Walker LS, Bluestone JA, Abbas AK, Dooms H. IL-7 receptor blockade reverses autoimmune diabetes by promoting inhibition of effector/memory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:12668–12673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203692109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hartgring SA, Willis CR, Alcorn D, Nelson LJ, Bijlsma JW, Lafeber FP, van Roon JA. Blockade of the interleukin-7 receptor inhibits collagen-induced arthritis and is associated with reduction of T cell activity and proinflammatory mediators. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2716–2725. doi: 10.1002/art.27578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2005;11:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lawson BR, Koundouris SI, Barnhouse M, Dummer W, Baccala R, Kono DH, Theofilopoulos AN. The role of alpha beta + T cells and homeostatic T cell proliferation in Y-chromosome-associated murine lupus. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2354–2360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lawson BR, Manenkova Y, Ahamed J, Chen X, Zou JP, Baccala R, Theofilopoulos AN, Yuan C. Inhibition of transmethylation down-regulates CD4 T cell activation and curtails development of autoimmunity in a model system. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5366–5374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McGavern DB, Truong P. Rebuilding an immune-mediated central nervous system disease: weighing the pathogenicity of antigen-specific versus bystander T cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:4779–4790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Reddy J, Bettelli E, Nicholson L, Waldner H, Jang MH, Wucherpfennig KW, Kuchroo VK. Detection of autoreactive myelin proteolipid protein 139–151-specific T cells by using MHC II (IAs) tetramers. J. Immunol. 2003;170:870–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Waldner H, Whitters MJ, Sobel RA, Collins M, Kuchroo VK. Fulminant spontaneous autoimmunity of the central nervous system in mice transgenic for the myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cell receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:3412–3417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rajnavolgyi E, Benbernou N, Rethi B, Reynolds D, Young HA, Magocsi M, Muegge K, Durum SK. IL-7 withdrawal induces a stress pathway activating p38 and Jun N-terminal kinases. Cell. Signal. 2002;14:761–769. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Burchill MA, Goetz CA, Prlic M, O'Neil JJ, Harmon IR, Bensinger SJ, Turka LA, Brennan P, Jameson SC, Farrar MA. Distinct effects of STAT5 activation on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell homeostasis: development of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells versus CD8+ memory T cells. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5853–5864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kawakami N, Nagerl UV, Odoardi F, Bonhoeffer T, Wekerle H, Flugel A. Live imaging of effector cell trafficking and autoantigen recognition within the unfolding autoimmune encephalomyelitis lesion. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1805–1814. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Baeten DL, Kuchroo VK. How cytokine networks fuel inflammation: Interleukin-17 and a tale of two autoimmune diseases. Nat. Med. 2013;19:824–825. doi: 10.1038/nm.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, Zaunders J, Sasson S, Landay A, Solomon M, Selby W, Alexander SI, Nanan R, Kelleher A, de St Groth B. Fazekas. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, Gottlieb PA, Kapranov P, Gingeras TR, de St Groth B. Fazekas, Clayberger C, Soper DM, Ziegler SF, Bluestone JA. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Juntilla MM, Koretzky GA. Critical roles of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in T cell development. Immunol. Lett. 2008;116:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fruman DA, Bismuth G. Fine tuning the immune response with PI3K. Immunol. Rev. 2009;228:253–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Li WQ, Jiang Q, Khaled AR, Keller JR, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 inactivates the pro-apoptotic protein Bad promoting T cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29160–29166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Welte T, Leitenberg D, Dittel BN, al-Ramadi BK, Xie B, Chin YE, Janeway CA, Jr., Bothwell AL, Bottomly K, Fu XY. STAT5 interaction with the T cell receptor complex and stimulation of T cell proliferation. Science. 1999;283:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tomita K, Saijo K, Yamasaki S, Iida T, Nakatsu F, Arase H, Ohno H, Shirasawa T, Kuriyama T, O'Shea JJ, Saito T. Cytokine-independent Jak3 activation upon T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation through direct association of Jak3 and the TCR complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25378–25385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Li G, Miskimen KL, Wang Z, Xie XY, Brenzovich J, Ryan JJ, Tse W, Moriggl R, Bunting KD. STAT5 requires the N-domain for suppression of miR15/16, induction of bcl-2, and survival signaling in myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2010;115:1416–1424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Deshpande P, Cavanagh MM, Le Saux S, Singh K, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. IL-7-and IL-15-mediated TCR sensitization enables T cell responses to self-antigens. J. Immunol. 2013;190:1416–1423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gagnon J, Chen XL, Forand-Boulerice M, Leblanc C, Raman C, Ramanathan S, Ilangumaran S. Increased antigen responsiveness of naive CD8 T cells exposed to IL-7 and IL-21 is associated with decreased CD5 expression. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2010;88:451–460. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Walsh MC, Pearce EL, Cejas PJ, Lee J, Wang LS, Choi Y. IL-18 synergizes with IL-7 to drive slow proliferation of naive CD8 T cells by costimulating self-peptide-mediated TCR signals. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3992–4001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Khaled AR, Durum SK. Lymphocide: cytokines and the control of lymphoid homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:817–830. doi: 10.1038/nri931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mazzucchelli R, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:144–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pellegrini M, Bouillet P, Robati M, Belz GT, Davey GM, Strasser A. Loss of Bim increases T cell production and function in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1189–1195. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Akashi K, Kondo M, von Freeden-Jeffry U, Murray R, Weissman IL. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Maraskovsky E, O'Reilly LA, Teepe M, Corcoran LM, Peschon JJ, Strasser A. Bcl-2 can rescue T lymphocyte development in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice but not in mutant rag-1−/− mice. Cell. 1997;89:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Walline CC, Kanakasabai S, Bright JJ. IL-7Ralpha confers susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Genes Immun. 2011;12:1–14. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ashbaugh JJ, Brambilla R, Karmally SA, Cabello C, Malek TR, Bethea JR. IL7Ralpha contributes to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through altered T cell responses and nonhematopoietic cell lineages. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4525–4534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Park JH, Yu Q, Erman B, Appelbaum JS, Montoya-Durango D, Grimes HL, Singer A. Suppression of IL7Ralpha transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines: a novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.