Abstract

Dysregulated cytokine metabolism plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of many forms of liver disease, including alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease. In this study we examined the efficacy of Misoprostol in modulating LPS-inducible TNFα and IL-10 expression in healthy human subjects and evaluated molecular mechanisms for Misoprostol modulation of cytokines in vitro. Healthy subjects were given 14 day courses of Misoprostol at doses of 100, 200, and 300 µg four times a day, in random order. Baseline and LPS-inducible cytokine levels were examined ex vivo in whole blood at the beginning and the end of the study. Additionally, in vitro studies were performed using primary human PBMCs and the murine macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7, to investigate underlying mechanisms of misoprostol on cytokine production. Administration of Misoprostol reduced LPS inducible TNF production by 29%, while increasing IL-10 production by 79% in human subjects with no significant dose effect on ex vivo cytokine activity; In vitro, the effect of Misoprostol was largely mediated by increased cAMP levels and consequent changes in CRE and NFκB activity, which are critical for regulating IL-10 and TNF expression. Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies demonstrated that Misoprostol treatment led to changes in transcription factor and RNA Polymerase II binding, resulting in changes in mRNA levels. In summary, Misoprostol was effective at beneficially modulating TNF and IL-10 levels both in vivo and in vitro; these studies suggest a potential rationale for Misoprostol use in ALD, NASH and other liver diseases where inflammation plays an etiologic role.

Keywords: inflammation, cAMP, CREB, NFκB, ChIP, liver disease

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic and alcoholic liver diseases are major health and economic problem worldwide [1–4]. Manifestation of both diseases ranges from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis, and could result in hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have increased circulating levels of gut-derived endotoxin (LPS) [5–7]. Endotoxemia leads to activation of cytokine producing cells, predominantly monocytes and Kupffer cells, and secretion of a variety of cytokines, resulting in an imbalance in cytokine homeostasis [8–11]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-10 and chemokines such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), and the hepatic acute phase cytokine, interleukin-6 (IL-6), play pivotal roles in modulating many of the systemic manifestations of liver injury and fibrosis [7, 12–18]. We and others reported that elevated serum TNF levels and increased monocyte TNF production in patients with alcoholic hepatitis (AH) are correlated with disease severity and poor prognosis [12, 19–21]. Subsequently, we showed that monocytes from AH patients have increased basal as well as LPS-stimulated TNF mRNA levels compared to monocytes from healthy control subjects [12]. Similarly, the TNF levels are elevated in patients with NASH, and have been shown to play a pathogenic role in this disease [7, 22]. Blocking TNF production prevents the development of experimental ALD/NASH and is beneficial for patients with AH and NASH [23–25]. Thus, there is compelling evidence for the role of TNF and other pro-inflammatory cytokines in the development and progression of liver disease. Currently there is no FDA-approved therapy to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with either ALD or NASH.

Prostaglandins (PGEs) are derivatives of fatty acids that are produced in most tissues of the body, and play an important role in cell mediated immune responses. Prostaglandins have protective effects against liver injury, due to downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly TNF α and IL-6, and upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 [26–36]. Importantly, it has been shown that PBMCs from alcoholic patients have significantly lower endogenous levels of PGE2 compared to PBMCs from non-alcoholic subjects. Alcoholics with abnormal liver function tests have PGE2 levels about1/3 normal [37]. Thus, altered prostaglandin production may also contribute to increased inflammatory cytokine production in ALD.

In the context of inflammatory cytokine expression, it has been shown that PGE1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects through activation of cAMP. PGE1 analogues have been used in experimental models of ischemia-reperfusion injury and inflammation; in clinical treatments of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, pulmonary hypertension, and glomerulonephritis; in hepatic, renal, and cardiac surgeries; and in neurosurgical procedures, due to their documented anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective actions [28, 30, 31, 33–36]. However, the use of prostaglandins in clinical settings has been limited because of poor oral bioavailability, significant toxicity profiles such as diarrhea, emesis, and hypotension [38, 39], and short half-lives [40, 41]. Misoprostol, which is a structural analogue of naturally occurring PGE1, is designed to overcome these problems. This compound has diminished prostaglandin side-effects, such as emesis, and diarrhea, as well as reduced undesirable effects on the cardiovascular system [42]. Misoprostol is an FDA-approved drug for the prevention/treatment of NSAID-(nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) induced gastric ulcer in high risk patients at a dosage of 200 µg orally, four times daily. Misoprostol has been reported to decrease proinflammatory cytokine production (TNF α, IL-6, and IL-8), and increase IL-10 levels in diseases/experimental paradigms not involving the liver [14, 27, 43]. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of Misoprostol therapy on LPS inducible TNF and IL-10 expression, which play a critical role in the development of alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease. Accordingly, we examined the efficacy of Misoprostol in modulating LPS inducible cytokine responses employing whole blood (ex-vivo) analysis before and after Misoprostol administration to healthy control subjects. We also examined underlying molecular mechanisms of Misoprostol treatment on LPS-inducible cytokine expression in isolated human peripheral blood monocytes (PBMC) and a murine macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Protocol

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and monitored by the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) at the Clinical Research Center (CRC) at University of Louisville. All study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and any potential risks/side effects. Informed consent was obtained. Nine normal subjects, 5 male, and 4 female, were enrolled in this double-blinded, dose finding, efficacy study. Each subject was assigned to one of the three groups which received Misoprostol (PGE1) at 100, 200 and 300 µg, orally, four times daily doses in a randomized fashion. The drug was administered in three phases; each phase spanning 14 days with a washout period of at least 10 days between each dose phase. All subjects were examined by the Principal Investigator before starting on Misoprostol, and blood samples were sent for complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, CD4+T count and CRP (C-reactive protein) to assure they were within normal limits. At each visit, information was obtained about compliance, adverse events, alcohol abstinence, contraceptive methods, and usage of any other medications during this period. Subjects were excluded from this study if they had a history of liver disease, myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, renal insufficiency, peptic ulcer disease, malignancy, autoimmune disorders, or systemic infections in the last two months; if they did not agree to practice effective contraceptive methods; or if they used over-the-counter vitamins, herbals, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids that could alter cytokine metabolism before participation in this study. For female subjects, a urine pregnancy test was performed before starting each new dose of Misoprostol, and they started each phase of the study within 5 days of starting a menstrual period. During Phase 1, fasting blood samples were collected on day 1 before the start of medication, and on day 14, 2 hours after taking the last dose of medication. Samples were collected in the same way for Phase 2 on days 25 and 38, and for Phase 3 on days 48 and 62.

2.2. Ex vivo human studies

A 10-mL sample of heparinized (10 U/ml) blood was collected and diluted 1:4 with RPMI 1640 medium (Bio Whitaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL). After 24 hour incubation with and without 1 µg/ml of LPS at 37°C with 5% CO2, samples were collected and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cell-free supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until assayed for cytokine measurement.

2.3. Materials

RAW 264.7 murine monocytes were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4) was purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, MI). Before use, LPS was dissolved in sterile, pyrogen-free water, sonicated, and diluted with sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Penicillin, streptomycin, DMEM media, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY); Anti-p65 antibody was from Biomol Research Laboratories Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), phospho CREB (Serine 133) and CREB antibodies were from Sigma (Saint-Louis, Missouri, USA). Misoprostol and H89 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

2.4. Isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from whole blood and treatment

PBMCs from healthy volunteers were isolated by Ficoll-Paque™ PREMIUM (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation as described previously [44]. The buffy coat was re-suspended in RPMI media supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 10 U/ml penicillin, and 10 µg/ml streptomycin and plated in cell culture flasks for two hours. After the cells were attached to the plastic, they were rinsed twice with PBS, scraped, counted and plated at 1 million cells/ml density. Purity of CD14+ cells was determined using BD FACSCantotm II flow cytometry system and yielded more than 75%. Cells were plated at 0.5 million/ml density, treated with Misoprostol (10 µM) for 90 minutes and further stimulated with 1µg/ml LPS.

2.5. Cell culture and treatments

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 10 U/ml penicillin, and 10 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Before treatment, cells were plated at 0.5 million/ml density, treated with 10 µM Misoprostol for 90 minutes and further stimulated with LPS, 100 ng/ml. PKA inhibitor, H89 was used at 10 µM concentration 30 minutes before Misoprostol treatment. All treatments were done in triplicates.

2.6. TNFα, IL-10 and cyclic AMP assay

TNFα and IL-10 cytokines were measure in cell free supernatants using ELISA kits (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA). Cyclic AMP concentrations in cell lysates were quantified using cAMP complete ELISA kit (Enzo, Life Sciences, Inc. Farmingdale, NY).

2.7. RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

RT-PCR assays were used to assess TNF-α and IL-10 mRNA levels. Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real time PCR was performed as described previously [44]. The parameter Ct (threshold cycle) was defined as the fraction cycle number at which the fluorescence passed the threshold. The relative gene expression of TNF-α was analyzed using 2−ΔΔCt method by normalizing with 18S gene expression in all the experiments.

2.8. Nuclear protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Cell nuclear extracts were prepared and protein levels analyzed by western blot as described previously [44].

2.9. Plasmids, transfections and Luciferase assay

NF-κB-Luciferase reporter construct was obtained from BD Biosciences/Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). CRE(1) Luciferase reporter vector was obtained from Panomics (Panomics, Inc., Fremont, CA). Transfections were carried out using FuGene according to instructions from the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). To control for differences in transfection efficiency, transfected cells were scraped and re-plated after 24 hours at a density of 0.5×106 cells/well in 24 well plates and treated for 6 hours. Luciferase activity was measured using Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). After treatments, total cell lysates were prepared in reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase enzymatic activity was measured in a TD 20/20 Luminometer using a specific substrate provided by Promega.

2.10. ChIP (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation) assay

The transcription factor and RNA polymerase II (RNA POL II) binding in TNF and IL-10 promoter regions was detected using a ChIP assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer, as described previously [44, 45]. ChIP antibodies directed against NFkB (p65), CREB and RNA Polymerase II (Millipore, Billerica, MA) were used for immunoprecipitation, and against a non-specific control rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). ChIP-qPCR was performed as described earlier [45]. The two primer pairs tested spanned regions in TNF promoter:

−195 to −117 (region I, p65 binding site) and −88 to +31 (region II, transcription start site, TSS) with respect to the transcription start site of REFSEQ: NM_013693.2:

ChIP-Primer for region I of TNF promoter:

FP 5’-CAACTTTCCAAACCCTCTGC-3’

RP 5’-ATGTGGAGGAAGCGGTAGTG-3’

ChIP-Primer for region II of TNF promoter:

FP 5’-TTTTCCGAGGGTTGAATGAG-3’

RP 5’-CTGGCTAGTCCCTTGCTGTC-3’

For IL-10 promoter two primer pairs tested spanned regions −377 to −270 (region I, CREB binding site) and −68 to +37 (region II, transcription start site, TSS) with respect to the transcription start site of REFSEQ: NM_010548.2:

ChIP-Primer for region I of IL-10 promoter:

FP 5’-TGTTCTGGAATAGCCCATTT-3’

RP 5’-TATTTCCTGAGGCAGACAGC-3’

ChIP-Primer for region II of IL-10 promoter

FP 5’-CAAAAACCTTTGCCAGGAAG-3’

RP 5’-TGTGGCTTTGGTAGTGCAAG-3’

2.11. Statistical Analysis

In vitro experiments related to mechanism were repeated at least three times. Representative data are presented as means ± SD for experiments preformed in triplicate. Student’s t-test and ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test was used for the determination of statistical significance. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

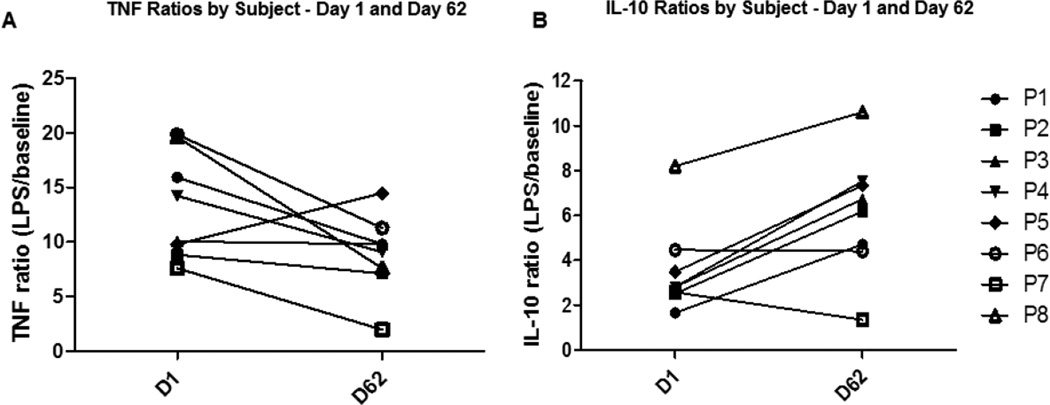

For ex vivo experiments, Day 1 to Day 62 ratios were used rather than day 1/day 14, or day 25/day 38, and day 49/day 62, as it became clear after the experiment that there was a likely carry-over effect of the medication due to the relatively short wash-out period and there was no does response effect (Fig. 1). Changes in TNF and IL-10 cytokine levels in response to Misoprostol administration are presented as a ratio of LPS-treated and baseline (without LPS treatment) for each subject at the beginning (Day 1) and at the end (Day 62) of the study. A one-sided Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used to test for paired differences between beginning and end of study ratios for each cytokine. Both SAS and R software were used for this test. All tests were performed using 8 subjects (one subject was excluded because an infected cyst developed while using 300 µg of Misoprostol).

Figure 1. Effect of Misoprostol administration on ex vivo cytokine production in humans.

Whole blood was collected from study subjects before (Day 1) and after Misoprostol administration (Day 62) and treated ex vivo with and without LPS (1µg/ml) for overnight. TNF and IL-10 production was measured in cell free supernatants by ELISA. Data are presented as ratios of LPS-stimulated over unstimulated levels for each study subject (P1–P8). (A) TNF ratios were significantly decreased (P=0.02) and (B) IL-10 ratios were significantly increased (P=0.027) after Misoprostol administration.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Misoprostol dosage and tolerance

Normal subjects were given varying doses of Misoprostol in random order: 100, 200 and 300 µg four times daily. Side effects were reported by subjects at each visit and/or by telephone contact during the study period. Dosages of 100 and 200 µg of Misoprostol were well tolerated by most of the subjects without significant side effects, while subjects who received 300 µg developed more gastrointestinal side effects, including diarrhea and/or abdominal cramping. In general, diarrhea decreased after a few days of Misoprostol treatment at dosages of 100 and 200 µg of Misoprostol, while most subjects who were on Misoprostol in a dose of 300 µg, had significant diarrhea with abdominal pain and cramping. Data from one subject was excluded due to the development of an infected cyst during the 300 µg treatment, and this dose was intolerable for two other subjects who completed this phase of study on a reduced dose. The side effects are enumerated with their relative incidence at the different dosages (Table 1)

Table 1.

The side effects profile for Misoprostol during the study

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms |

Misoprostol 100 µg |

Misoprostol 200 µg |

Misoprostol 300 µg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 22% | 33% | 67% |

| Nausea | 22% | 11% | 33% |

| Abdominal pain | 33% | 22% | 56% |

| Abdominal cramping | 33% | 22% | 56% |

3.2. Misoprostol modulates LPS-inducible cytokine production in humans

Normal subjects were given varying doses of misoprostol over a period of 62 days as described in 2.1. Whole blood was diluted with RPMI media as described in Methods and treated with and without LPS for 24 hours. After 24 hours, cell-free supernatant was collected and TNF and IL-10 levels were measured by ELISA. Induction of TNF and IL-10 by LPS was calculated as a ratio of LPS-stimulated to unstimulated (baseline) before (Day 1) and after Misoprostol administration (Day 62). Day 1 to Day 62 ratios were used rather than day 1/day 14, or day 25/day 38, and day 49/day 62, as it became clear after the experiment that there was a carry-over effect of the medication due to short wash-out period and there was no dose response (Fig. 1). TNF ratios before Misoprostol treatment were 13.2 which dropped to 9 on day 62 (29% decrease, P=0.02). There was a significant increase from 3.6 on day 1 to 6.2 on day 62 in IL-10 ratios (79% increase, P=0.027) (Fig. 1).

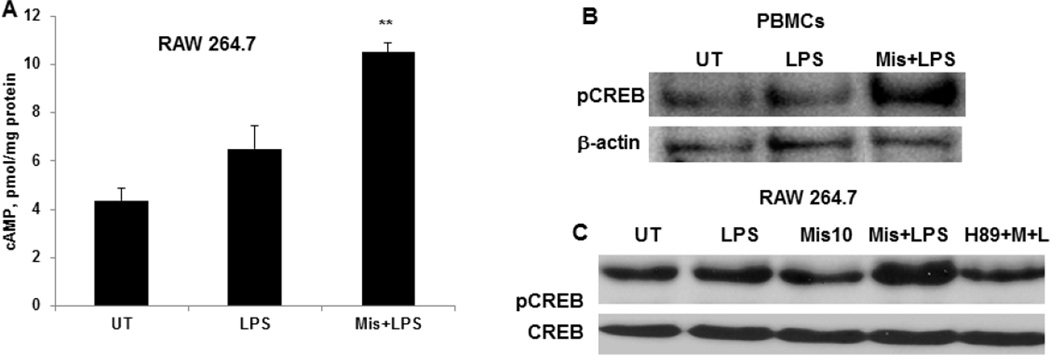

3.3. Misoprostol increases LPS-inducible intracellular cAMP levels and CREB phosphorylation

To examine the underlying molecular mechanisms of Misoprostol effect on LPS-inducible cytokines, we performed in vitro experiments using both human primary PBMCs and murine macrophage cell line 264.7. The immunosuppressive effect of Misoprostol (a PGE1 analog) has been shown to be mediated by its binding to G-protein-coupled EP receptors (EP1–EP4). Binding to EP2 and 4 receptors results in activation of adenyl cyclase, leading to increased intracellular cAMP levels [46]. Indeed, pretreatment of cells with misoprostol resulted in significant increases in LPS inducible cAMP levels (Fig. 2A). cAMP effects on cytokine production are largely mediated by PKA, which phosphorylates and activates the transcription factor, CREB [47–49]. Hence, we examined whether nuclear pCREB levels were affected by misoprostol. RAW and PBMCs were pretreated with misoprostol (10µM) and further stimulated with LPS for 30 minutes. Nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis. Misoprostol exposure resulted in increased phosphorylation of CREB in both PBMCs and RAW cells (fig. 2B, C); pretreatment with PKA inhibitor, H89 prevented misoprostol effect on CREB phosphorylation (fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Misoprostol significantly increases LPS-inducible intracellular cAMP and nuclear pCREB levels.

(A) RAW 264.7 cells were treated with LPS with and without Misoprostol pretreatment for 3 hours and intracellular cAMP levels were measured by cAMP kit. Data are presented as mean±SD, n=3. P<0.01 compared to LPS alone. (B) Human PBMCs were treated with 1 ug/ml LPS for 30 minutes with and without Misoprostol pretreatment and nuclear pCREB levels were analyzed by Western blot. (C) Murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) were treated with PKA inhibitor H89 before Misoprostol (10 µM) and further stimulated with LPS (100ng/ml) for 30 minutes. Nuclear pCREB levels were analyzed by Western blot.

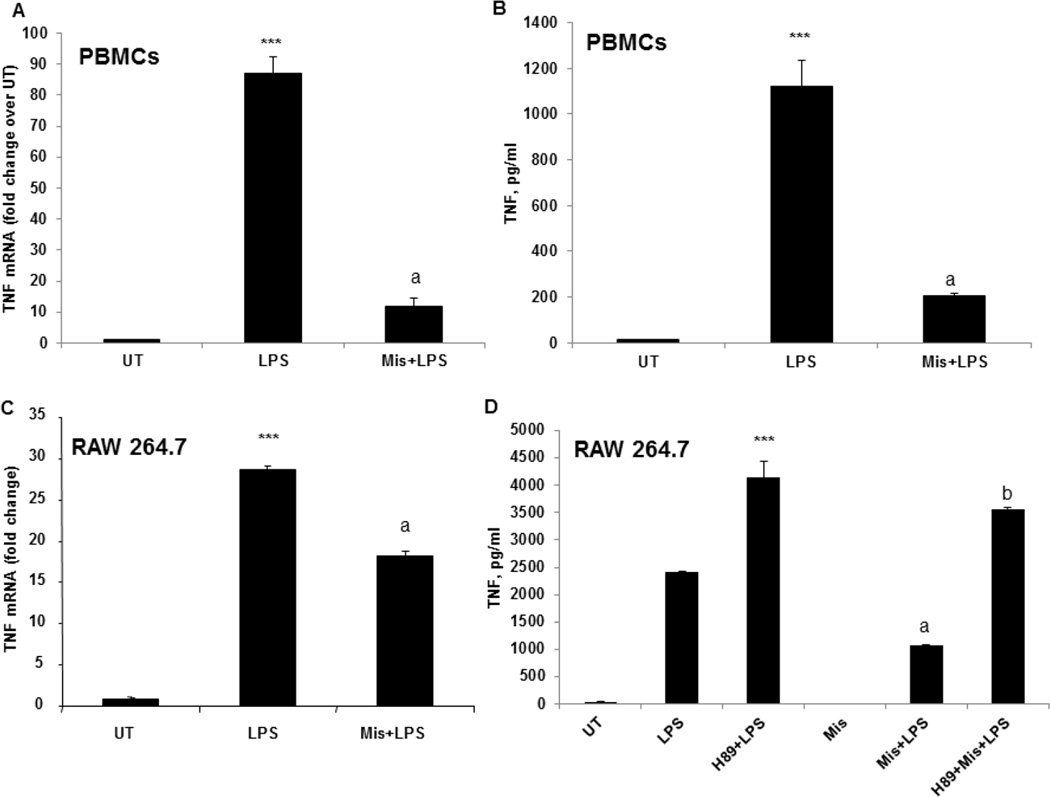

3.4. Misoprostol inhibits LPS-inducible TNF expression in a PKA dependent manner

Next, the effect of Misoprostol on LPS-inducible TNF expression was assessed in human PBMCs and RAW 264.7 cells. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood of healthy volunteers and pretreated with Misoprostol 10 µM for 90 minutes and further stimulated with LPS, 1 µg/ml. The effect of Misoprostol on TNF mRNA expression was evaluated at 3 hours and TNF protein levels were measured at 6 hours after LPS stimulation. Misoprostol significantly attenuated LPS-inducible TNF expression at both protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 3A, B). The same effect was observed in RAW cells pretreated with Misoprostol (Fig. 3C). Next, we examined if the PKA inhibitor, H89, would reverse the observed Misoprostol effect on TNF expression after LPS stimulation. Prior to Misoprostol treatment, cells were pretreated with H89 and then stimulated with LPS. TNF levels in cell free supernatants were measured using ELISA kit. H89 pre-treatment resulted in an augmented response of cells to LPS-inducible TNF production and abolished inhibitory effect of Misoprostol (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Misoprostol significantly attenuates LPS-inducible TNF expression in a PKA dependent manner. (A) PBMCs were pretreated with misoprostol and stimulated with LPS, 1 µg/ml. TNF mRNA expression was examined by real time RT PCR after 3h of LPS stimulation. (B) Cell-free supernatant was collected 6 hours after LPS stimulation, and TNF protein was measured using ELISA kit.***P<0.001 compared to untreated (UT), aP<0.001 compared to LPS. Data are presented as mean±SD, n=3. (C) TNF mRNA levels were analyzed by real time PCR in RAW 264.7 cells treated with LPS for 2 hours with and without Misoprostol pretreatment. ***P<0.001 compared to untreated (UT), aP<0.001 compared to LPS. D. RAW cells were pretreated with H89 (10 µM) before Misoprostol and further stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 hours. TNF production was measured in cell free supernatants using TNF ELISA kit. Data are presented as mean±SD, n=3. ***P<0.0001 compared to LPS, aP<0.001 compared to LPS, bP<0.001 compared to Mis+LPS.

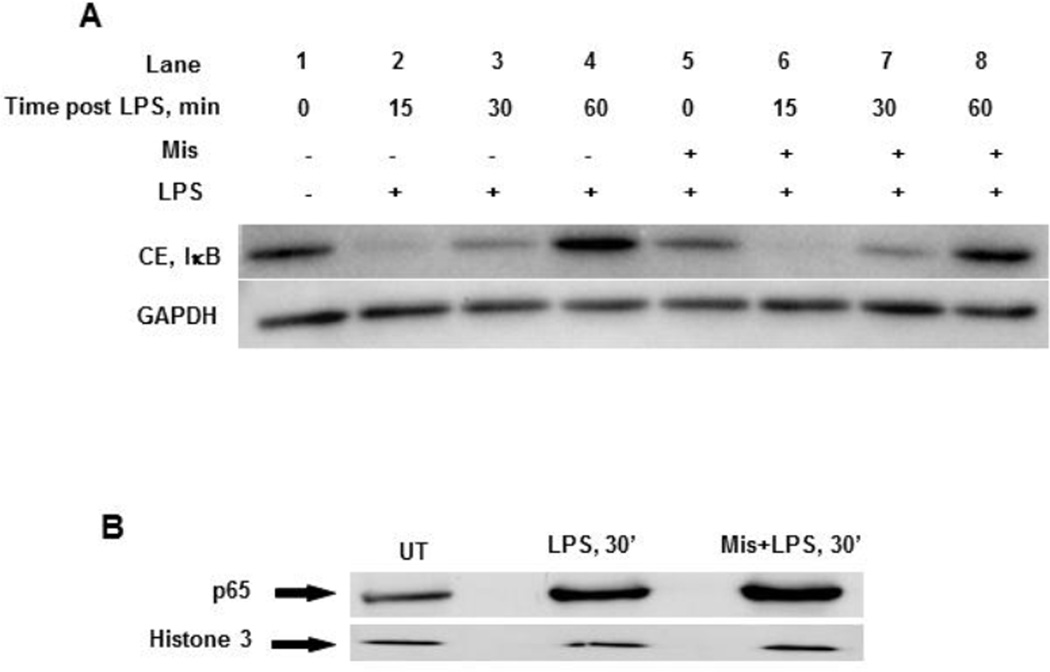

3.5. Misoprostol does not affect LPS-induced IκBα Degradation and NFκB Nuclear Translocation

LPS stimulation leads to the degradation of IκBα, which sequesters NFκB in the cytoplasm in unstimulated conditions, and allows the translocation of NFκB into the nucleus, where it can bind to the promoter of target genes (e.g. TNF) and initiate transcription. To examine the effect of misoprostol on IκBα degradation, Western blot analysis was performed using cytoplasmic extracts obtained from cells with and without Misoprostol pretreatment. As expected, IκBα degradation was observed at 15 and 30 minutes in cells treated with LPS (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3); however there was no significant effect of Misoprostol on the rate or the level of IκBα degradation (Fig. 4A; compare lanes 2, 3 and 6, 7). After degradation, IκBα returned to basal level in 60 minutes in both untreated and misoprostol treated cells (Fig 5A, lanes 4 and 8). Correspondent to IκBα degradation in the cytoplasm, nuclear levels of p65 were not reduced by Misoprostol; if anything, we observed a slight increase (Fig. 4B). These data show that misoprostol does not affect LPS-induced IκBα proteolysis and NFκB activation.

Figure 4. Misoprostol does not affect IκB degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to LPS.

(A) RAW cells with and without Misoprostol pretreatment were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for indicated times, and cytoplasmic IκB levels were analyzed by Western blot. (B) Nuclear p65 levels in RAW cells after 30 minutes of LPS treatment with and without Misoprostol pretreatment. Histone 3 was used as a loading control.

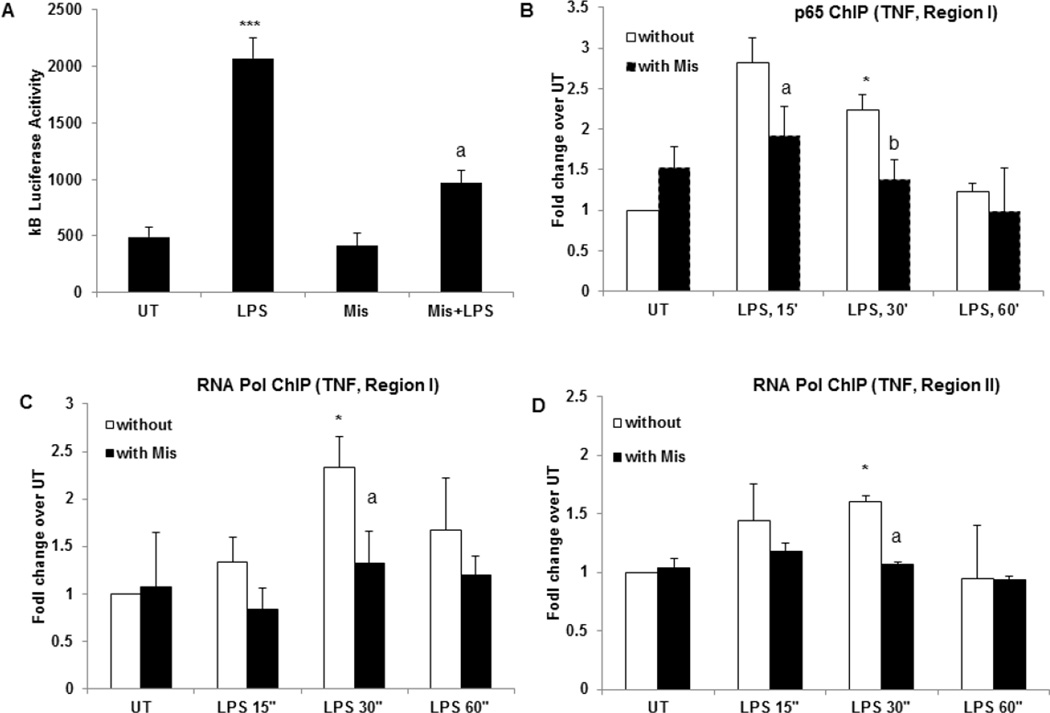

Figure 5. Misoprostol significantly attenuates LPS inducible NFκB activity and p65 recruitment to TNF promoter.

(A) RAW cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing the NFκB-responsive IκB promoter. The transfected cells were pretreated with Misoprostol (10 µM) and stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 hours. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared and equal amounts were assayed for luciferase activity. ***P<0.01 and aP<0.05 compared to LPS. (B) RAW cells treated with and without Misoprostol were stimulated with LPS for indicated times. ChIP was performed with p65 antibody and TNF promoter was examined by qChIP PCR at p65 binding region (region I). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to UT without Mis, aP<0.05 compared to LPS, 15’ alone, bP<0.05 compared to LPS, 30’. (C) RNA Polymerase II ChIP was performed on cells treated as in (B), TNF promoter was examined by qChIP PCR at p65 binding region (regions I). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to UT without Mis, aP<0.05 compared to LPS, 30’ alone. (D) RNA Polymerase II binding to TSS site on TNF promoter (region II) was examined in cells treated as in (B) and (C). *P<0.05 compared to UT without Mis, aP<0.05 compared to LPS, 30’ alone. Data are presented as means±SD, n=3.

3.6. Misoprostol attenuates transcriptional activity of NFκB and recruitment of p65 and RNA polymerase II to TNF promoter

We further examined the effect of misoprostol on NFκB transcriptional activity by transient transfection of RAW cells with a reporter construct carrying a luciferase gene under the control of an NFκB promoter containing 3 tandem repeats of the κB sequence (κB-luc). After transfection, cells were replated in 24-well plate and treated. Stimulation of cells with LPS for 6 hours resulted in a four-fold increase in NFκB dependent transcription as indicated by kB luciferase activity (Fig. 5A). Misoprostol pretreatment of cells significantly attenuated LPS-stimulated NFκB activity, whereas Misoprostol itself had no effect (Fig. 5). These results are in agreement with our earlier findings [44, 50, 51] which showed that increased cellular cAMP levels have no effect on LPS-inducible NFκB activation, but can significantly decrease transcriptional stimulation by NFκB. To further examine if decreased NFκB activity results in decreased binding of p65 to the TNF promoter, we performed ChIP analysis. Cells with and without Misoprostol pretreatment were treated with LPS for indicated times and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Prepared chromatin was immune-precipitated with ChIP grade p65 antibody and qChIP-PCR was performed to examine the p65 occupancy on TNF promoter region (region I). We chose this region based on previous studies which showed that p65 binding to this region is critical for LPS-inducible TNF expression [52]. As expected, correspondent to increased TNF mRNA expression in LPS stimulated cells, p65 binding was significantly increased in 15 minutes after LPS stimulation (Fig. 5B); however, Misoprostol treatment led to a marked attenuation of p65 binding (Fig. 5B). Further, immune-precipitation with RNA POL II antibody showed that the recruitment of RNA Pol II to the same region was significantly increased in LPS stimulated cells which reached the peak at 30 minutes after LPS stimulation; this recruitment was decreased in Misoprostol treated cells (Fig. 5C). RNA POL II recruitment was also increased with LPS in TSS region (II) of TNF promoter (Fig. 5D). Notably, in Misoprostol treated cell no RNA POL II occupancy in the TSS region was observed even after LPS stimulation (Fig. 5D). These data demonstrate that Misoprostol treatment results in decreased p65 binding and RNA POL II recruitment to TNF promoter ultimately leading to attenuation of TNF transcription.

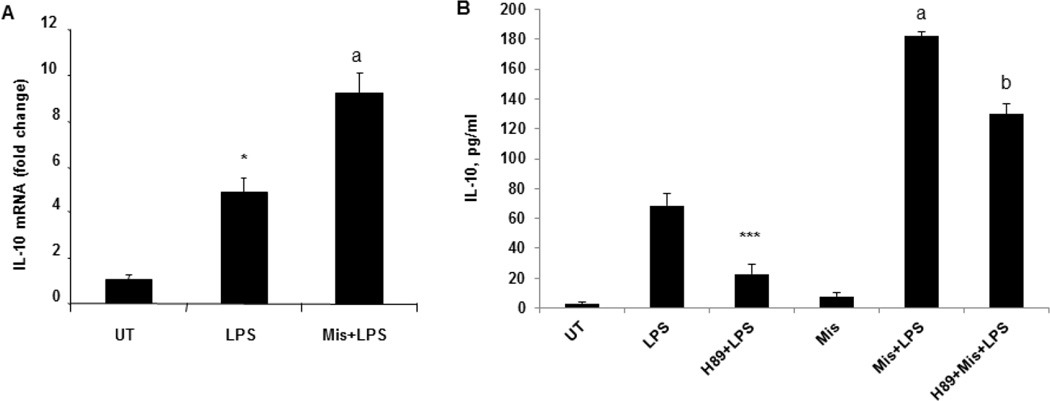

3.7. Misoprostol increases LPS inducible IL-10 expression in a PKA dependent manner

Effect of Misoprostol was also examined on LPS inducible IL-10 expression. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with Misoprostol and stimulated with LPS. Misoprostol treatment resulted in a significant increase in LPS-inducible IL-10 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 6A, B). Importantly, Misoprostol effect on IL-10 expression was mediated by PKA; when we used PKA inhibitor, H89 before Misoprostol pretreatment, we observed that H89 markedly decreased LPS-inducible IL-10 and reduced Misoprostol effect (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Misoprostol significantly increase LPS-inducible IL-10 expression in a PKA dependent manner.

(A) RAW cells pretreated with 10 µM Misoprostol were further stimulated with LPS, 100ng/ml, for 2 hours and IL-10 mRNA expression was analyzed by real time PCR. *P<0.05 compared to UT, aP<0.05 compared to LPS. (B) IL-10 production was measured in cell free supernatants of RAW cells treated with H89, Misoprostol and further stimulated with LPS for 6 hours. ***P<0.01 compared to LPS, aP<0.001 compared to LPS). Data are presented as means±SD, n=3.

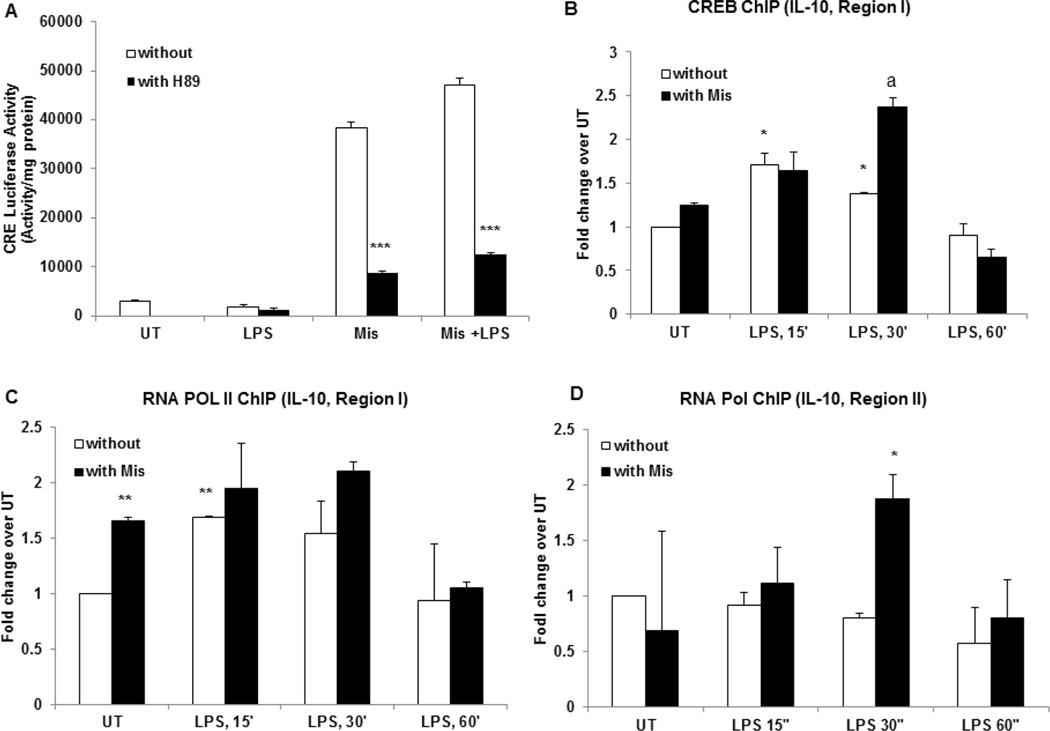

3.8. Misoprostol increases CRE transcriptional activity and CREB binding to IL-10 promoter

To further examine the underlying mechanisms of Misoprostol effect of IL-10 expression, we tested whether misoprostol increases the transcriptional activity of cAMP responsive element (CRE). We performed transient transfection in RAW 264.7 cells with a CRE luciferase reporter. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were with Misoprostol. Prior to Misoprostol treatment some cells were pre-treated with PKA inhibitor H89. At 6 hours, cells were collected and lysed and luciferase activity was measured. Misoprostol significantly increased CRE promoter activity in a PKA-dependent manner demonstrating that misoprostol effect is largely mediated by cAMP-PKA (Fig. 7A). We further examined whether misoprostol treatment actually increases CREB binding to IL-10 promoter by ChIP analysis using CREB antibody. We designed primers for the IL-10 promoter regions spanning CREB binding and TSS sites as described in 2.10. LPS treatment transiently increased CREB binding to region I; importantly, correspondent with increased CREB levels and transcriptional activity, Misoprostol treatment resulted in much higher and prolonged CREB binding (Fig. 7B). Further, commensurate with the increased CREB binding, we observed a significant binding of RNA POL II to region I at 15 and 30 minutes after LPS treatment; Notably, Misoprostol increased the baseline binding of RNA POL II (Fig. 7C). Misoprostol treatment also significantly increased RNA POL II binding to region overlapping TSS (II), which was not observed by LPS treatment alone (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7. Misoprostol significantly increases CRE transcriptional activity and CREB binding to IL-10 promoter.

Cells were transfected with a CRE luciferase reporter vector as described in 2.9. The transfected cells were treated with Misoprostol (10 µM), H89 (10 µM) and LPS (100 ng/ml). Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared in 6 hours after LPS treatment and equal amounts were assayed for luciferase activity. ***P<0.001 compared to cells without Misoprostol treatment. Data are presented as means±SD, n=3. (B) RAW cells treated with and without Misoprostol were stimulated with LPS for indicated times. ChIP was performed with CREB antibody and IL-10 promoter was examined by qChIP PCR at CREB binding region (region I). *P<0.05 compared to UT without Mis, aP<0.01 compared to LPS, 30’ alone. (C) RNA Polymerase II ChIP was performed on cells treated as in (B), Il-10 promoter was examined by qChIP PCR at CREB binding region (I). **P<0.01 compared to UT without Mis, aP<0.05 compared to LPS, 30’ alone. (C) RNA Polymerase II binding to TSS site on IL-10 promoter was examined in cells treated as in (B) and (C) (II). *P<0.05 compared to LPS, 30’ alone. Data are presented as means±SD, n=3.

4. Discussion

An imbalance in the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of several disease states including alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease. In this regard, data from clinical studies and animal models have shown that there is an increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as, TNF in ALD/NAFLD, while there is decreased activity of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 [4, 53–55]. It has also been shown that the imbalance between TNF and IL-10 increases with the progression of the disease from simple hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis [53, 56–58]. Our earlier work documented that decreased cAMP levels played a causal role in the priming of monocytes/macrophages leading to an increase in LPS-inducible TNF expression [50]. We have also shown that increased cAMP signaling significantly attenuates liver inflammation, injury and development of fibrosis [59]. The results from the present study strongly indicate that Misoprostol both in vivo and in vitro is highly effective in decreasing the expression of the endotoxin-inducible pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF, and increasing the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. Importantly, we show for the first time that the underlying mechanisms of the antiinflammatory function of Misoprostol involve promoter recruitment of transcription factor(s) and RNA Polymerase II, leading to modulation of LPS-inducible TNF and IL-10 gene expression.

LPS-inducible transcriptional induction of the TNF gene is critically mediated by nuclear translocation of NFκB and promoter binding [60–62]. Examination of nuclear p65 levels demonstrated that Misoprostol did not affect LPS-inducible NFκB nuclear translocation. However, Misoprostol significantly suppressed LPSinducible NFκB promoter activity and TNF mRNA expression (Fig. 5). These data strongly suggest that Misoprostol decreased the transcriptional activity of NFκB by affecting its ability to interact with the TNF promoter. Similarly, our earlier work and others have demonstrated that cAMP can decrease LPS-inducible NFκB transcriptional activity and nuclear translocation rather that NFκB activation leading to a decrease in macrophage activation and TNF mRNA expression [44, 50, 63–65]. Taken together, the present data indicate that Misoprostol attenuates NFκB transcriptional activity and TNF expression via its ability to increase cellular cAMP. The observed decrease in the recruitment of NFκB to the TNF promoter in the Misoprostol treated cells could be due the cAMP-mediated epigenetic mechanisms such as transcriptionally repressive promoter histone modifications, and are currently being investigated. Further, transcriptional activity of NFκB can also be significantly influenced by its interaction with its co-activator CBP/p300 via p65 [49, 66–68]. In this regard, increased levels of pCREB can compete with p65, by interacting with CBP/p300 (both RelA (p65) and pCREB interact with CBP/p300 in the same region) [49]. Accordingly, increased levels of pCREB mediated by Misoprostol could decrease NFκB transcriptional activity by competing with its co-activator CBP/p300. Taken together, these data suggest that Misoprostol could affect the transcriptional potential of NFκB by interfering with its promoter binding as well as its optimal transcriptional activity.

The effect of cAMP on IL-10 expression in macrophages and peripheral blood monocytes is well established [47–49, 69]. Accordingly, the observed increase in IL-10 expression by Misoprostol also likely relates to its ability to increase cellular cAMP levels. A cAMP response element (CRE) is present in the promoter region of the human IL-10 gene which mediates the effect of cAMP on IL-10 production [70, 71]. Particularly, an increase in intracellular cAMP leads to activation of cAMP-specific PKA which, in turn, phosphorylates CREB and is required for increased IL-10 production in human mononuclear cells [47]. In view of this, the ChIP data demonstrate that the Misoprostol induced increase in cAMP/PKA and pCREB does indeed play a contributory role in the induction and enhancement of IL-10 gene expression (Fig. 6, 7). These observations are also supported by other studies wherein PGE1 analogs increase IL-10 expression [29, 31, 72].

The results of this study demonstrate for the first time that Misoprostol can effectively attenuate LPS induced imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The presented findings strongly suggest that Misoprostol can have potential therapeutic application in disease states driven by increased inflammatory cytokines accompanied by a decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as ALD and NASH. Further, since there is no FDA approved drug for the treatment of ALD or NASH, the potential application of Misoprostol as a “repurposed drug” has clinical importance that warrants further clinical investigation.

Highlights.

We demonstrate the efficacy of Misoprostol in modulating LPS-inducible cytokine production in humans

Misoprostol anti-inflammatory function is critically mediated through increased cAMP signaling involving activation of PKA and CREB

Misoprostol decreases NFkB activity and binding to TNF promoter leading to decreased TNF gene expression

Increased CREB activity by Misoprostol results in increased CREB binding to IL-10 promoter and IL-10 genes expression

Acknowledgments

We thank Marion McClain for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R21AA022189 (LG), R01AA018869 (CJM), R01AA014185(CJM), 1U01AA021893 (CJM), U01AA021901 (CJM), 1R01AA023681(CJM) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (CJM).

Abbreviations

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase A

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor α

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

Leila Gobejishvili performed in vitro experiments and analyzed the data. Smita Ghare performed ChIP analysis. These two authors contributed equally to this work. Drs. Hill and McClain provided critical insight in designing the clinical trial and recruited human subjects for this study; Dr. Khan collected whole blood and performed ex vivo studies. Dr. Barker designed and optimized ChIP primers for gene promoter analysis. Dr. Cambon performed statistical analysis for ex vivo study. Dr. Barve and Dr. McClain provided substantial contributions to discussions of content, and to reviewing and editing the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Hill DB, McClain CJ. Anti-TNF therapy in alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(2):261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwenger KJ, Allard JP. Clinical approaches to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(7):1712–1723. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orman ES, Odena G, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis, management, and novel targets for therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):77–84. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keshavarzian A, et al. Leaky gut in alcoholic cirrhosis: a possible mechanism for alcohol-induced liver damage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera CA, et al. Role of endotoxin in the hypermetabolic state after acute ethanol exposure. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):G1252–G1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.6.G1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peverill W, Powell LW, Skoien R. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of NASH: beyond steatosis and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(5):8591–8638. doi: 10.3390/ijms15058591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode C, Kugler V, Bode JC. Endotoxemia in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis and in subjects with no evidence of chronic liver disease following acute alcohol excess. J Hepatol. 1987;4(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui H, et al. Plasma endotoxin concentrations in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease: reevaluation with an improved chromogenic assay. J Hepatol. 1991;12(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanji AA, Khettry U, Sadrzadeh SM. Lactobacillus feeding reduces endotoxemia and severity of experimental alcoholic liver (disease) Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;205(3):243–247. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolan JP. The role of endotoxin in liver injury. Gastroenterology. 1975;69(6):1346–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1989;9(3):349–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClain C, et al. Cytokines and alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1993;13(2):170–182. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuman MG, et al. Role of cytokines in ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in vitro in Hep G2 cells. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton AJ, Ham J, Kunkel SL. Kupffer cell-derived cytokines induce the synthesis of a leukocyte chemotactic peptide, interleukin-8, in human hepatoma and primary hepatocyte cultures. Hepatology. 1991;14(6):1112–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheron N, et al. Circulating and tissue levels of the neutrophil chemotaxin interleukin-8 are elevated in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis, and tissue levels correlate with neutrophil infiltration. Hepatology. 1993;18(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill DB, Marsano LS, McClain CJ. Increased plasma interleukin-8 concentrations in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1993;18(3):576–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maher JJ. Rat hepatocytes and Kupffer cells interact to produce interleukin-8 (CINC) in the setting of ethanol. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(4 Pt 1):G518–G523. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.4.G518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClain C, et al. Dysregulated cytokine metabolism, altered hepatic methionine metabolism and proteasome dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(11 Suppl):180S–188S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000189276.34230.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bird GL, et al. Increased plasma tumor necrosis factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(12):917–920. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-12-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spahr L, et al. Soluble TNF-R1, but not tumor necrosis factor alpha, predicts the 3-month mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2004;41(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarrar MH, et al. Adipokines and cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(5):412–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilg H, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody therapy in severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2003;38(4):419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, et al. Probiotics and antibodies to TNF inhibit inflammatory activity and improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37(2):343–350. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams LA, et al. A pilot trial of pentoxifylline in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(12):2365–2368. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hossain MA, Izuishi K, Maeta H. Effect of short-term administration of prostaglandin E1 on viability after ischemia/reperfusion injury with extended hepatectomy in cirrhotic rat liver. World J Surg. 2003;27(10):1155–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6914-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianotti L, et al. Prostaglandin E1 analogues misoprostol and enisoprost decrease microbial translocation and modulate the immune response. Circ Shock. 1993;40(4):243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakazawa K, et al. Effect of prostaglandin E1 on inflammatory responses and gas exchange in patients undergoing surgery for oesophageal cancer. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(2):199–203. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi HK, et al. Unique regulation profile of prostaglandin e1 on adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307(3):1188–1195. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.056432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naruo S, et al. Prostaglandin E1 reduces compression trauma-induced spinal cord injury in rats mainly by inhibiting neutrophil activation. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20(2):221–228. doi: 10.1089/08977150360547125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Perrot M, et al. Prostaglandin E1 protects lung transplants from ischemia-reperfusion injury: a shift from pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokines. Transplantation. 2001;72(9):1505–1512. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200111150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haynes DR, Whitehouse MW, Vernon-Roberts B. The prostaglandin E1 analogue, misoprostol, regulates inflammatory cytokines and immune functions in vitro like the natural prostaglandins E1, E2 and E3. Immunology. 1992;76(2):251–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson RG. Prostaglandin E1 and myocardial reperfusion injury. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2649–2650. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato S, et al. Suppressive effect of pulmonary hypertension and leukocyte activation by inhaled prostaglandin E1 in rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Exp Lung Res. 2002;28(4):265–273. doi: 10.1080/01902140252964357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakuma F, Miyata M, Kasukawa R. Suppressive effect of prostaglandin E1 on pulmonary hypertension induced by monocrotaline in rats. Lung. 1999;177(2):77–88. doi: 10.1007/pl00007632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugawara Y, et al. Protective effect of prostaglandin E1 against ischemia/reperfusion-induced liver injury: results of a prospective, randomized study in cirrhotic patients undergoing subsegmentectomy. J Hepatol. 1998;29(6):969–976. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxwell WJ, et al. Prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 synthesis by peripheral leucocytes in alcoholics. Gut. 1989;30(9):1270–1274. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.9.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cattral MS, et al. Toxic effects of intravenous and oral prostaglandin E therapy in patients with liver disease. Am J Med. 1994;97(4):369–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pickles H, O'Grady J. Side effects occurring during administration of epoprostenol (prostacyclin, PGI2), in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;14(2):177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golub M, et al. Metabolism of prostaglandins A1 and E1 in man. J Clin Invest. 1975;56(6):1404–1410. doi: 10.1172/JCI108221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho MJ, Allen MA. Chemical stability of prostacyclin (PGI2) in aqueous solutions. Prostaglandins. 1978;15(6):943–954. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer RF. Misoprostol preclinical pharmacology. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30(11 Suppl):118S–125S. doi: 10.1007/BF01309396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotani N, et al. Intraoperative prostaglandin E1 improves antimicrobial and inflammatory responses in alveolar immune cells. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1943–1949. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gobejishvili L, et al. S-adenosylmethionine decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced phosphodiesterase 4B2 and attenuates tumor necrosis factor expression via cAMP/protein kinase A pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337(2):433–443. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.174268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghare SS, et al. Coordinated histone H3 methylation and acetylation regulate physiologic and pathologic fas ligand gene expression in human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2014;193(1):412–421. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(4):1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eigler A, et al. Anti-inflammatory activities of cAMP-elevating agents: enhancement of IL-10 synthesis and concurrent suppression of TNF production. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63(1):101–107. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brenner S, et al. cAMP-induced Interleukin-10 promoter activation depends on CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein expression and monocytic differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(8):5597–5604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen AY, Sakamoto KM, Miller LS. The role of the transcription factor CREB in immune function. J Immunol. 2010;185(11):6413–6419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gobejishvili L, et al. Chronic ethanol-mediated decrease in cAMP primes macrophages to enhanced LPS-inducible NF-kappaB activity and TNF expression: relevance to alcoholic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291(4):G681–G688. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00098.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gobejishvili L, et al. Enhanced PDE4B expression augments LPS-inducible TNF expression in ethanol-primed monocytes: relevance to alcoholic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(4):G718–G724. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90232.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuprash DV, et al. Similarities and differences between human and murine TNF promoters in their response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1999;162(7):4045–4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zahran WE, et al. Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor and Interleukin-10 Analysis in the Follow-up of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Progression. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28(2):141–146. doi: 10.1007/s12291-012-0236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolo AP, Teodoro JS, Palmeira CM. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(1):59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawaratani H, et al. The effect of inflammatory cytokines in alcoholic liver disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:495156. doi: 10.1155/2013/495156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das SK, Balakrishnan V. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2011;26(2):202–209. doi: 10.1007/s12291-011-0121-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.An L, Wang X, Cederbaum AI. Cytokines in alcoholic liver disease. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(9):1337–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwamoto S, et al. TNF-alpha is essential in the induction of fatal autoimmune hepatitis in mice through upregulation of hepatic CCL20 expression. Clin Immunol. 2013;146(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gobejishvili L, et al. Rolipram attenuates bile duct ligation-induced liver injury in rats: a potential pathogenic role of PDE4. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;347(1):80–90. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.204933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas JG, et al. Molecular mechanisms in down-regulation of tumor necrosis factor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(24):9563–9567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muller JM, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Baeuerle PA. Nuclear factor kappa B, a mediator of lipopolysaccharide effects. Immunobiology. 1993;187(3–5):233–256. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(15):1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ollivier V, et al. Elevated cyclic AMP inhibits NF-kappaB-mediated transcription in human monocytic cells and endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(34):20828–20835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shames BD, et al. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha production by cAMP in human monocytes: dissociation with mRNA level and independent of interleukin-10. J Surg Res. 2001;99(2):187–193. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beshay E, Croze F, Prud'homme GJ. The phosphodiesterase inhibitors pentoxifylline and rolipram suppress macrophage activation and nitric oxide production in vitro and in vivo. Clin Immunol. 2001;98(2):272–279. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghosh S, Hayden MS. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(11):837–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(10):692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerritsen ME, et al. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(7):2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zidek Z. Adenosine -cyclic AMP pathways and cytokine expression. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1999;10(3):319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Platzer C, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive elements are involved in the transcriptional activation of the human IL-10 gene in monocytic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(10):3098–3104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3098::AID-IMMU3098>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alvarez Y, et al. The induction of IL-10 by zymosan in dendritic cells depends on CREB activation by the coactivators CREB-binding protein and TORC2 and autocrine PGE2. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):1471–1479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waiser J, et al. The immunosuppressive potential of misoprostol--efficacy and variability. Clin Immunol. 2003;109(3):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]