Abstract

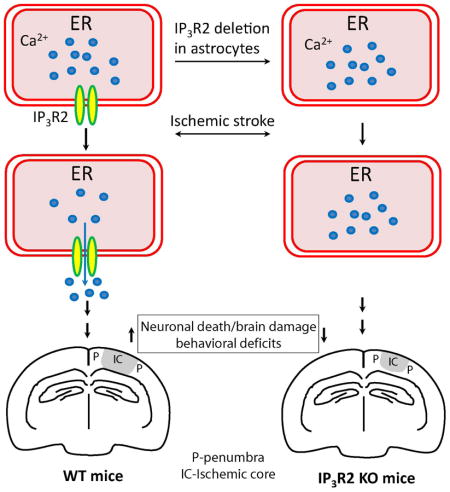

Inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-mediated intracellular Ca2+ increase is the major Ca2+ signaling pathway in astrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS). Ca2+ increases in astrocytes have been found to modulate neuronal function through gliotransmitter release. We previously demonstrated that astrocytes exhibit enhanced Ca2+ signaling in vivo after photothrombosis (PT)-induced ischemia, which is largely due to the activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). The aim of this study is to investigate the role of astrocytic IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling in neuronal death, brain damage and behavior outcomes after PT. For this purpose, we conducted experiments using homozygous type 2 IP3R (IP3R2) knockout (KO) mice. Histological and immunostaining studies showed that IP3R2 KO mice were indeed deficient in IP3R2 in astrocytes and exhibited normal brain cytoarchitecture. IP3R2 KO mice also had the same densities of S100β+ astrocytes and NeuN+ neurons in the cortices, and exhibited the same glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and glial glutamate transporter (GLT-1) levels in the cortices and hippocampi as compared with wild type (WT) mice. Two-photon (2-P) imaging showed that IP3R2 KO mice did not exhibit ATP-induced Ca2+ waves in vivo in the astrocytic network, which verified the disruption of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes of these mice. When subject to PT, IP3R2 KO mice had smaller infarction than WT mice in acute and chronic phases of ischemia. IP3R2 KO mice also exhibited less neuronal apoptosis, reactive astrogliosis, and tissue loss than WT mice. Behavioral tests, including cylinder, hanging wire, pole and adhesive tests, showed that IP3R2 KO mice exhibited reduced functional deficits after PT. Collectively, our study demonstrates that disruption of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling by deleting IP3R2s has beneficial effects on neuronal and brain protection and functional deficits after stroke. These findings reveal a novel non-cell-autonomous neuronal and brain protective function of astrocytes in ischemic stroke, whereby suggest that the astrocytic IP3R2-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway might be a promising target for stroke therapy.

Keywords: photothrombosis, ischemic stroke, astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, two-photon imaging, infarction, neuronal death, reactive astrogliosis, behavioral tests

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a leading neurological disorder that causes brain damage, disability and death, and thus has a major impact on public health. Despite tremendous efforts being taken in translational research, treatment strategies for ischemic stroke are still limited [1;2]. Thus, identifying new molecular pathways that can reduce neuronal death and improve stroke outcomes has remained an intensive research area. Astrocytes are the predominant glial cell type in the central nervous system (CNS). Although astrocytes are electrically non-excitable, Ca2+ signaling is the signature feature of astrocytes in the brain and plays an important role in astrocyte-neuron communications [3–5]. Astrocytes generally employ metabotropic receptors that are coupled with Gq/11 (i.e., G-protein coupled receptors, GPCRs) to activate phospholipase C (PLC). PLC causes the liberation of IP3 that activates IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) to mediate Ca2+ release from internal stores. Stimulation of various GPCRs, including the P2Y receptors, metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and γ-aminobutyric acid b receptors (GABAbRs), can induce Ca2+ increase in astrocytes in vivo [6–10]. Astrocytic Ca2+ increases caused by the simulation of mGluR5 can modulate synaptic function through activation of neuronal extrasynaptic NMDA receptors manifested as slow inward currents (SICs) [11–14]. PLC/IP3R is the major Ca2+ signaling pathway in astrocytes.

Studies have shown that astrocytes are quiescent with respect to somatic Ca2+ fluctuation in vivo under normal conditions with anesthesia [6;8;9;12]; however, under pathological conditions, including ischemia, status epilepticus, traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease,, astrocytes display different properties in Ca2+ signaling in vivo [6;12;15–17]. Using two photon (2-P) microscopy, we have previously demonstrated that astrocytes exhibit enhanced Ca2+ signaling in vivo after photothrombosis (PT)-induced cerebral ischemia in mice [6]. Such Ca2+ signaling is characterized by high-frequency intercellular Ca2+ waves and increased amplitude among the astrocytic network. Using pharmacological reagents, we further showed that the PT-induced astrocytic Ca2+ signals are largely mediated by mGluR5 and GABAbRs and that, group I mGluR inhibitors, including 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), significantly reduce infarct volume and suppress Ca2+-dependent calpain activation [18]. In addition, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid AM (BAPTA-AM), which can be selectively loaded in astrocytes in vivo to buffer the global intracellular Ca2+ [12], also significantly reduces ischemic infarction [6]. These studies indicate that astrocytic Ca2+ signals contribute to neuronal death and brain damage after ischemia. However, these pharmacological inhibitors might not act specifically on astrocytes, and BAPTA is also a non-pathway specific Ca2+ chelator. In addition, many other signaling pathways can mediate Ca2+ increases in astrocytes [19–21]. Studies also show that type 2 IP3R (IP3R 2) is primarily expressed and the predominant IP3R in astrocytes in the rodent brain [22–24], and thus in the current study, we investigated the role of astrocytic IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway in ischemia using IP3R2 KO mice. We initially characterized their brain and subsequently examined the role of astrocytic IP3R2 in brain damage in acute and chronic phases after PT-induced focal ischemic stroke. Furthermore, we assessed whether and how astrocytic IP3R2 affects long-term histological and behavioral outcomes after PT. Using infarct volume measurements, cell death assays, immunostaining and behavioral tests, our results demonstrate that deletion of IP3R2 in astrocytes can ameliorate brain damage, apoptotic neuronal death, tissue loss, reactive astrogliosis and reduce functional deficits after PT. Our findings suggest that astrocytic GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway might be a promising target for stroke therapies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

The IP3R2 KO mice were generated as described previously [25;26]. They are global IP3R2 KO mice as IP3R2 is also expressed outside the CNS in WT mice. All mice were maintained at the University of Missouri mouse facility under pathogen-free conditions according to institutional guidelines. Positive mice were genotyped by PCR amplification of their DNA obtained from tail snips. Adult male and female mice aged 8–10 weeks were used in this study. All procedures were performed according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care Quality Assurance Committee.

2.2. PT-induced brain ischemia model

The procedure for PT was well established as described in our previous studies [18;27–29]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized by ketamine and xylazine (130 mg/10 mg/kg body weight), and the photosensitive dye rose Bengal dissolved in saline was injected through the tail vein at a dose of 30 mg/kg. For histological and immunocytochemical studies, PT was induced in an area of intact skull with 1.5 mm in diameter centered at −0.8 mm from the bregma and 2.0 mm lateral to the midline in somatosensory cortex. This area was focally illuminated for 2 min through a 10× objective (NA=0.3) with the X-cite 120 PC metal halide lamp (power set at 12%, EXFO, Canada) of a Nikon FN1 epi-fluorescent microscope (~13 mW green light of bandwidth 540–580 nm). Mice were sacrificed at different times after PT. Similarly, for behavioral tests, PT was induced in a region with a diameter of 2.5 mm centered at 2.0 mm to the left of bregma in somatosensory cortex which covers forelimb responsive site [30–32].

2.3. Infarct volume and brain tissue loss measurements

The procedures were similar to our previous studies [27–29;33]. For histological and immunostaining studies, adult mice were transcardially perfused at different times after PT with phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH7.4), followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) PBS. The brain was then post-fixed in 4% PFA PBS at 4 °C overnight and transferred to PBS with 30% sucrose for 2–3 days until it sunk. Coronal sections of brain slices with a thickness of 30 μm were cut using a cryostat (CM1900, Leica) and serially put on gelatin-coated glass slides or in 48-well plates with 0.01 M PBS. To measure the infarct volume, every fifth brain slice on the glass slides was stained with 0.25% cresyl violet (Nissl-staining). The infarct volume was determined by measuring the areas showing the loss of Nissl-staining in brain sections using the ImageJ software (NIH) as in our previous studies [27–29;33]. The total infarct volume of ischemic tissue was calculated by multiplying the individual infarct area by the total thickness of the five slices (150 μm). Brain tissue loss was estimated from the Nissl-stained brain sections in every fifth brain section (giving a distance of 150 μm between two sections) that covered entire lesion. Tissue loss (%) was quantified as the area of contralateral hemisphere minus the area ipsilateral hemisphere and divided by the area of contralateral hemisphere [29;34].

2.4. Western blot analyses

We used Western blot analysis to determine IP3R2, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and glial glutamate transporter (GLT-1) protein levels in WT and IP3R2 KO mice [18;27]. Total protein was extracted from freshly-harvested brain cortices and hippocampi using a lysis buffer plus protease inhibitor (Pierce Biotechnology, IL), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, MO), pH 8.2. The homogenized tissues were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant fluid was the total cell lysate. The protein concentration of the cell lysate was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, IL). Equivalent amounts of protein from each sample were diluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels at 100 mV, and subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) and were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 3% (w/v) BSA with 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide in TBST with rabbit anti-IP3R2 antibody (1:1000, kindly provided by Dr. Ju Chen, University of California, San Diego) [26], mouse anti-GFAP (1:2500, Millipore), mouse anti-GLT1 (1:1000, Millipore, CA) and monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:2000, Cytoskeleton, CO). The membranes were incubated with goat HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) or rabbit HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2500, Sigma, CA) diluted in 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBST for one h at room temperature. The membranes were then exposed to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents (Pierce, IL) and autoradiograph films (ISC BioExpress, UT) to visualize bands.

2.5. Immunostaining analyses

The floating method was used for immunostaining as described in our previous studies [6;18;27;28;35]. Brain sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse anti-neuronal nuclei (NeuN) monoclonal antibody (1:200, Millipore, CA), a mouse anti-GFAP monoclonal antibody (1:800, Millipore), a mouse anti-S100β monoclonal antibody (1:500, Sigma), and rabbit anti-IP3R2 (Millipore). Brain sections were then incubated with Rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200) or FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200, Millipore) for 4 h at room temperature. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon FN1 epi-fluorescence microscope or an Olympus FV1000 confocal fluorescent microscope.

2.6. Fluoro-Jade B (FJB) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining

Brain sections were stained with FJB to detect degenerating neurons as described in our previous studies [27;28;33]. Briefly, brain sections fixed with 4% PFA on glass slides were washed with ddH2O and immersed in 0.06% potassium permanganate for 20 min, and then immersed into 0.0004% FJB in 0.1% acetic acid solution for 45 min in the dark. For detecting apoptotic neurons, TUNEL staining was performed using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, CA) similar to our previous studies [18;36]. Briefly, brain tissue sections were incubated in freshly prepared permeabilization solution (0.1% triton x-100, 0.1% sodium citrate) for 2 min on ice. TUNEL reaction mixture was then added on the brain sections and incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C for 60 min in the dark. Images of the FJB- and TUNEL-stained sections were acquired with MetaVue imaging software (Molecular Device, CA) using a Nikon epi-fluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a CoolSNAP-EZ CCD-camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ).

2.7. Cell counting

The number of GFAP+, FJB+ and TUNEL+ cells in the penumbra were counted using MetaMorph imaging software as in our previous studies [18;29;35]. Cell counting was performed by an experimenter blind to experimental conditions. Cells were counted if they contained a whole-cell body [27;37] and data were presented as number per mm2. The data from 3 slices of each mouse brain were averaged as a single value for that mouse and the summary data were the average value from multiple mice and expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

2.8. In vivo 2-P Ca2+ imaging in astrocytes and data analysis

Detailed procedures for surgery and in vivo imaging have been described in our previous publications [6;12;38]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of urethane (1.5–2.0 mg/g body weight) dissolved in ACSF. A circular craniotomy (2.0 mm in diameter) was made using a high speed drill over the somatosensory cortex at coordinates −0.8 mm from bregma and 2.0 mm lateral to the midline. A custom-made metal frame was attached to the skull with cyanocrylate glue, and the dura was then carefully removed with fine forceps. After astrocytes in the cortex were labeled with Ca2+ indicator fluo-4 AM, mice were transferred to the stage of a 2-P microscope for in vivo imaging. Images were obtained using a Leica SP 1500 microscope using a 60× (NA=0.9) water immersion objective. A Mai Tai laser (Spectra-Physics, CA) was used for 2-P excitation (820 nm). For ATP administration, ACSF containing 0.5 mM ATP was applied to the cortex. The cranial window was then refilled with 2% agarose containing 0.5 mM ATP. ACSF containing the same concentration was applied on the surface of solidified agarose before imaging. Imaging was usually performed on astrocytes 80–100 μm below the cortical surface within 15–60 min after ATP administration. Multiple time-lapse imaging was performed to monitor Ca2+ signals for a period of 7.5 min for each with acquisition rates of one image every two seconds. For each animal, 15–25 astrocytes in 4–5 fields were imaged, and all the astrocytes imaged were used for analysis. Throughout the experiment (about 3–4 h from the beginning of surgery to the end of imaging), the mice were maintained at 37 °C using a heating pad (Fine Science Tool, CA) and at a surgical level of anesthesia. Importantly, it has been reported that animals anesthetized with urethane maintain relative constant physiological parameters including heartbeat and blood oxygen levels and mimic a sleep-like brain state [39–41].

Ca2+ signals were analyzed as described in our previous studies [6;12]. Briefly, the fluorescent signals were quantified by measuring the mean pixel intensities of the cell body of each astrocyte using MetaMorph software (Molecular Device, CA). Ca2+ changes were expressed as ΔF/Fo values vs. time, where Fo was the baseline fluorescence. To calculate the magnitude of Ca2+ signals without subjective selection of threshold values, we integrated the ΔF/Fo signal over the imaging period and normalized to 300 s using Origin software (OriginLab Corporation, MA). The resulting value was expressed as ΔF/Fo.s in all graphs. Data collected from multiple cells from each mouse were averaged and the averaged value of these cells was used as a single value for that mouse. The summary data were the average value from multiple mice.

2.9. Behavior tests

A battery of behavioral tests were performed on control (N=8) and ischemic mice (N=16) on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14 and 21 after PT as described in our previous study and elsewhere [29]. Pre-training was done before ischemia. These tests included cylinder, hanging wire, pole and adhesive removal tests [42;43].

2.10. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were reported as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were made by a student’s paired t-test for two groups or a one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni post hoc test) for multiple groups. p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of IP3R2 deficient mice

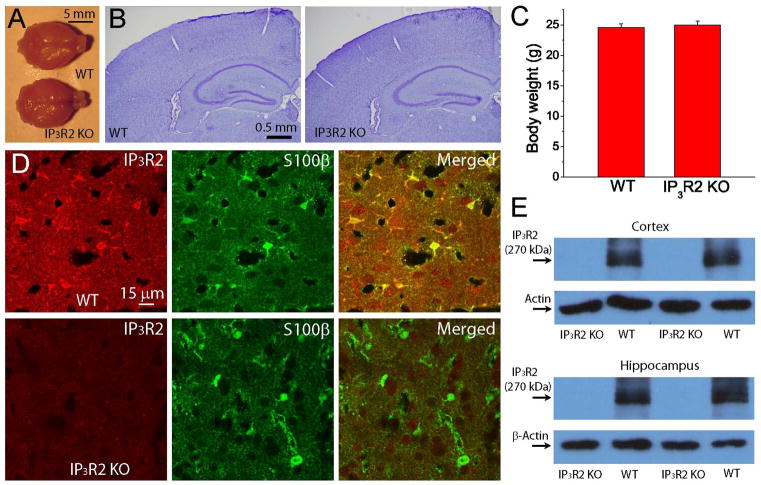

In order to examine the roles of IP3R in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, we used homozygous IP3R2 KO mice. Compared with WT litter mates, IP3R2 KO mice are viable and fertile and display no gross anatomical abnormalities of whole brain and normal brain cytoarchitecture of the cortex and hippocampus as revealed by Nissl staining (Fig. 1A–B), consistent with the results from a study by Petravicz et al [25]. In addition, IP3R2 KO and WT mice have similar body weights, suggesting no metabolic difference (Fig. 1C). To confirm the deficiency of IP3R2 in knockout mice, we first performed immunostaining of IP3R2 and S100β in brain sections based on genotyping and found that immunofluorescent signals of IP3R2 are only present in the astrocytes in WT mice based on the colocalization with S100β signals, while IP3R2 signals in astrocytes is absent in IP3R2 KO mice (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, our data from Western blot study also showed that a 270 kD band of IP3R2 is absent in the hippocampus and cortex in IP3R2 KO mice (Fig. 1E). Based on immunostaining and Western blot analysis, we confirmed that IP3R2 is indeed absent in astrocytes in homozygous IP3R2 KO mice.

Fig. 1. Deletion of IP3R2 in astrocytes in mouse brain.

A) Whole brain images of adult WT and IP3R2 KO mice. The brains were perfused and fixed in PFA. B) Nissl staining of coronal brain sections of adult WT and IP3R2 KO mice showing no anatomical abnormality. C) Body weight of WT (N=16) and IP3R2 KO mice (N=20) at two months old. D) Immunostaining of IP3R2 and S100β in WT (upper panels) and IP3R2 KO (lower panels) mice in the cortex. E) Western blotting images of IP3R2 in the cortex and hippocampus. Notice the absence of the IP3R2 band in IP3R2 KO mice.

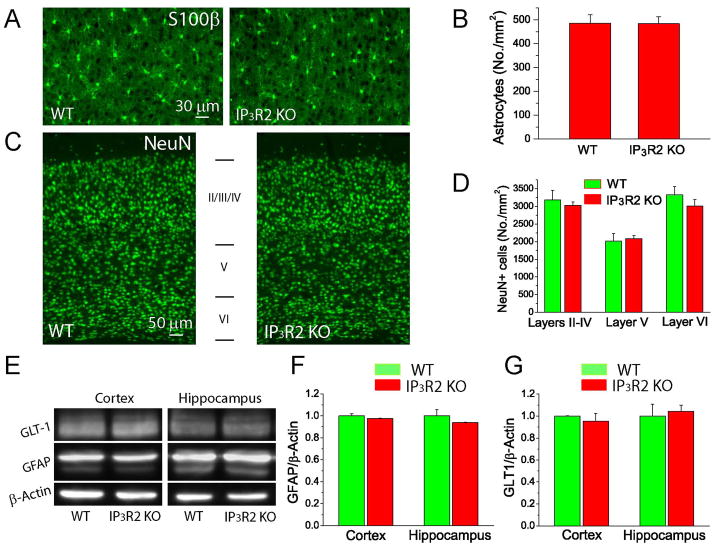

We further examined whether there are other cellular and molecular changes presumably caused by astrocytic deletion of IP3R2. Using immunostaining, our data show that there is no difference in the densities of mature cortical S100β+ astrocytes (Fig. 2A–B) and cortical NeuN+ neurons in layers II–IV, V and VI (Fig. 2C–D) between the two genotypes, indicating no cell-autonomous and non-cell autonomous effect of astrocytic IP3R2 on the astrocytic and neuronal populations in the cortex. GFAP is also an important cellular marker of astrocytes, but there was no difference in GFAP levels in the cortices and hippocampi between the two groups (Fig. 2E–F). Importantly, there was also no difference in the protein levels of GLT-1, the major astrocytic glutamate transporter in adult mice (Fig. 2E & G), suggesting that deletion of IP3R2 does not affect glutamate uptake by astrocytes under normal conditions.

Fig. 2. Characterization of WT and IP3R2 KO mice.

A–B) Fluorescent images of S100β staining (A) and the densities of S100β+ astrocytes in the cortices of WT and IP3R2 KO mice (B). C–D) Fluorescent images of NeuN staining (C) and the densities of NeuN+ neurons in the different layers in the cortices (D). E–G) Western blot images (E) and analysis of GFAP (F) and GLT-1 (G) levels in the hippocampus and cortex.

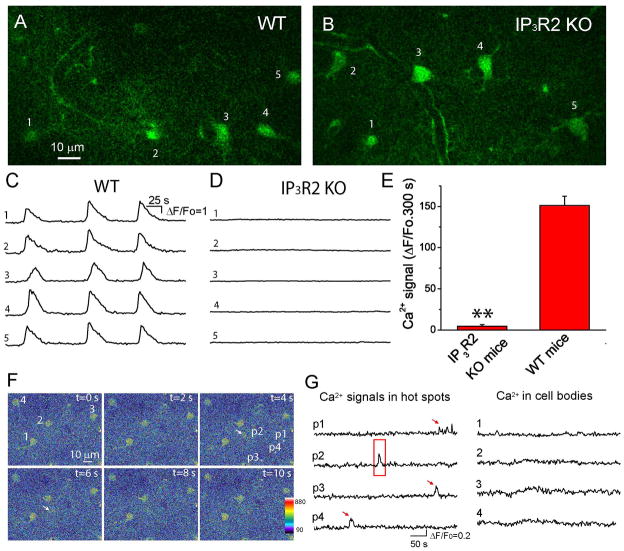

3.2. IP3R2 KO mice do not exhibit ATP-stimulated somatic Ca2+ waves in astrocytes in vivo

In order to test whether the deletion of IP3R2 affects Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, we performed in vivo Ca2+ imaging on astrocytes using 2-P microscopy [6;12;38]. Previously, we have shown that stimulation of GPCR agonists including ATP, dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) and chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG), can induce astrocytic intercellular somatic Ca2+ waves including the appearance of high-frequency and regenerative Ca2+ waves in astrocytic network by the continuous presence of ATP [6;12;38]. Therefore, we examined the ATP-stimulated, astrocytic Ca2+ waves in WT and IP3R2 KO mice using in vivo 2-P imaging. Continuous presence of ATP on the dura-removed cortex induced regenerative and sustained intercellular Ca2+ waves in astrocytes in WT mice in vivo under anesthesia (Fig. 3A, 3C & 3E); however, IP3R2 KO litter mates did not exhibit intercellular waves under the same conditions (Fig. 3B, 3D–3E), in agreement with previous studies that IP3R2 is the predominant IP3R in astrocytes in the mouse brain [22–24]. Our data, from a functional study of in vivo Ca2+ imaging, demonstrated that IP3R2 is expressed in astrocytes. Moreover, the deletion of IP3R2 abolishes ATP-stimulated somatic Ca2+ waves in astrocytes.

Fig. 3. Deletion of IP3R2 in mice abolishes ATP-stimulated somatic Ca2+ oscillations and waves in astrocytes in vivo.

A–B) Single frame images of astrocytes labeled with fluo-4 in the cortices of WT and IP3R2 KO mice. C–D) Time courses of somatic fluo-4 fluorescence of individual astrocytes indicated by the numbers in the upper panels in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP. Note there is no somatic Ca2+ oscillation or wave observed in IP3R2 KO mice. E) Summary of somatic Ca2+ signals of astrocytes from WT (59 astrocytes from N=4 mice) and IP3R2 KO (36 astrocytes from N=3 mice) mice. Data were average values of Ca2+ signal from individual mice. The Ca2+ signal for each mouse was the average value of multiple cells. Ca2+ signals of individual astrocytes were obtained by integration of ΔF/Fo fluorescence over 300 s. ** p<0.005, t-test. F) Pseudocolor fluorescent images shown the appearance of one hot spot in the process (p2 with an arrow) near an astrocyte. Notice hot spots p1, p3 and p4 in the processes exhibited Ca2+ increases at different times from p2 (see G). Four astrocyte somata were labeled with numbers 1–4. G) Time courses of Ca2+ signals in the processes and cell bodies of astrocytes.

We and others have shown that, under normal conditions, astrocytes do not exhibit somatic Ca2+ waves in vivo without GPCR agonist stimulation; however, astrocytes do exhibit spontaneous and low frequency Ca2+ activities in the somata as well as in the fine processes [8;12;44]. Here, using in vivo 2-P imaging, we revealed that IP3R2 KO mice also exhibited spontaneous and low frequency Ca2+ increases in the fine processes, but did not exhibit Ca2+ increases in the somata (Fig. 3F–G). The data suggest that astrocytes can mediate IP3R2-independent Ca2+ signaling under normal conditions, in agreement with a recent report using the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6 [45].

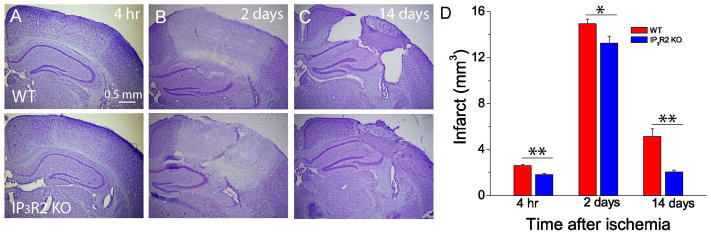

3.3. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 ameliorates neuronal injury, apoptosis and brain damage after PT

To determine the role of IP3R2 in brain damage after ischemic stroke, we used PT-induced focal ischemia model. PT was induced unilaterally in the somatosensory cortex through the intact skulls of WT and IP3R2 KO mice. It has been known that the evolution of brain infarction is time dependent in acute phase and stabilized from day one postischemia [29;46], and tissue shrinkage and loss take place in the chronic phase of ischemia [29;47]. We therefore sacrificed mice at 4 h, 2 and 14 days after PT for histochemical study and infarct volume measurement. Our results showed that an ischemic lesion based on Nissl staining could be identified 4 h after PT (Fig. 4A). The ischemic core was clearly demarcated from surrounding tissue, and the underlying white matter was also partly affected two days after PT (Fig. 4B). It was also apparent that a glial scar barrier separating the normal brain tissue from the ischemic core had developed at this time point (Fig. 4B). Statistically, IP3R2 KO mice exhibit significantly smaller infarction than WT mice 4 h, 2 and 14 days after PT (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 attenuates ischemia-induced brain damage in acute and chronic phases after PT.

A–C) Representative Nissl staining images of brain sections in the middle of brain infarction at 4 h, 2 days and 14 days after PT in WT and IP3R2 KO mice. D) Infarct volumes at 4 h, 2 days and 14 days after PT in WT and IP3R2 KO mice. Data were obtained from N=10–12 mice at each time point for each group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, t-test.

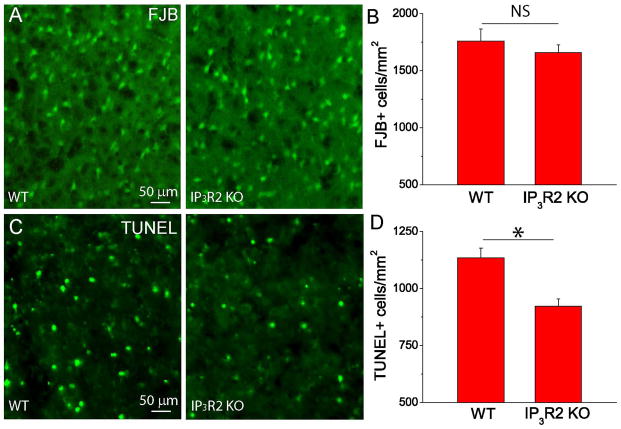

FJB detects degenerating neurons early after stroke. FJB+ neurons peak at 24 h and remain stable until three days after ischemia [46]. Apoptotic neuronal death occurs at a delayed time point after stroke and can be detected by TUNEL staining [18;48;49]; therefore, to further test the role of astrocytic IP3R2 on mediating neuronal death, we conducted FJB staining two days after PT and TUNEL staining seven days after PT to compare the degenerating and apoptotic neurons between the WT and KO mice. Our data showed that IP3R2 KO mice have similar density of FJB+ neurons (Fig. 5A–B), but have a significantly reduced density of TUNEL+ neurons (Fig. 5C–D) in the penumbra as compared with WT mice. It is worth noting that since WT mice had a larger infarction than IP3R2 KO mice, the total number of FJB+ neurons in the WT was still larger than IP3R2 KO mice. Thus, our results indicate that IP3R2 in astrocytes plays an important role in brain damage and neuronal death after ischemia.

Fig. 5. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 alleviates neuronal apoptosis after PT.

(A) Representative images of FJB staining in the penumbra at two days after PT from WT and IP3R2 KO mice. (B) Summary of the densities of FJB+ cells in the penumbra two days after PT. N=6 mice for each group. (C) Representative images of TUNEL staining in penumbra seven days after PT from WT and IP3R2 KO mice. (D) Summary of the densities of TUNEL+ cells in the penumbra from WT and IP3R2 KO mice seven days after PT. N=4 mice for each group. In (B) and (D), the average value of three brain sections in the middle of infarction from each mouse was used as a single value for that mouse. *p<0.05, t-test. NS-no significant difference.

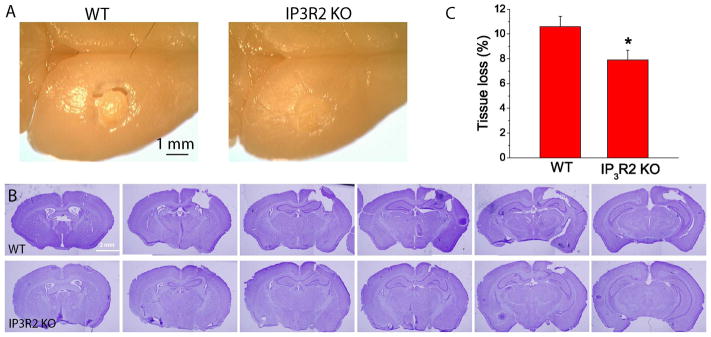

Interestingly, we observed that WT mice had cavities surrounding the infarction 14 days after PT, presumably due to the shrinkage of peri-infarct tissue whereas KO mice exhibited a compact ischemic tissue (Fig. 6A–B), which is consistent with our previous study using inhibitors of group 1 mGluRs [18]. Although overall infarct volumes were greatly reduced for both groups of mice at this time point as compared with 4 h and 2 days after PT, IP3R2 KO mice had a much smaller infarct volume than WT mice (Fig. 4C–D). IP3R2 KO mice also exhibited significantly less tissue loss than WT mice (Fig. 6C). These data demonstrate that deletion of IP3R2 in astrocytes can protect the brain from long-term damage after PT-induced ischemia.

Fig. 6. IP3R2 KO mice have reduced tissue loss in the chronic phase of ischemia.

A) Images of whole brains of WT and IP3R2 KO mice 14 days after ischemia. Notice tissue crack (the large tissue loss) in the WT mice. B) Rostrocaudal series of Nissl-stained coronal sections showing the infarction 14 days after PT of WT and IP3R2 KO mice. C) Summary of tissue loss of WT and IP3R2 KO mice. Data were the average values of N=12 mice for each group. *p<0.05, t-test.

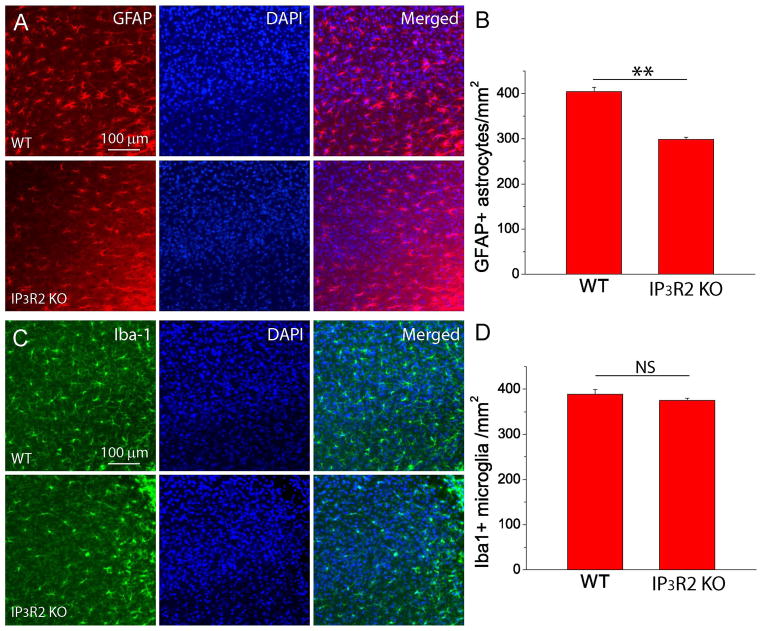

3.4. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 perturbs reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation in the penumbral region

A hallmark of the focal ischemic stroke is reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation manifested by the large upregulation of GFAP expression in reactive astrocytes [29;50–53]. The process of reactive gliosis is spatial and temporal dependent after focal ischemia and includes both proliferation of glial cells and upregulation of GFAP and Iba1 in existing astrocytes and microglia. Overall, reactive gliosis increases GFAP+ astrocytes and Iba+ microglia in the peri-infarct region [29;47;54]. Therefore, we conducted GFAP and Iba1 immunostaining and counted GFAP+ astrocytes and Iba+ microglia in the penumbra to determine the effects of astrocytic IP3R2 on reactive gliosis two weeks after PT [18;29]. Our data show that IP3R2 KO mice exhibited a significant decrease in the density of GFAP+ reactive astrocytes as compared with WT mice (Fig. 7A–B), but the densities of Iba1+ microglia between the two groups were similar (Fig. 7C–D). In addition, from visual inspection, reactive astrocytes in WT mice have thicker GFAP+ processes than in IP3R2 KO mice, while Iba1+ microglia exhibit similar morphology between the two groups.

Fig. 7. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 attenuate reactive astrogliosis after PT.

A–B) GFAP staining images (A) and densities of GFAP+ astrocytes (B) in the penumbra of WT and IP3R2 KO mice at two weeks after PT. C–D) Iba1 staining images (C) and densities of Iba1+ microglia (D) in the penumbra of WT and IP3R2 KO mice at two weeks after PT. The data were average values of brain sections in the middle of infarction from three mice in each group. **p<0.005, t-test. NS-no significant difference.

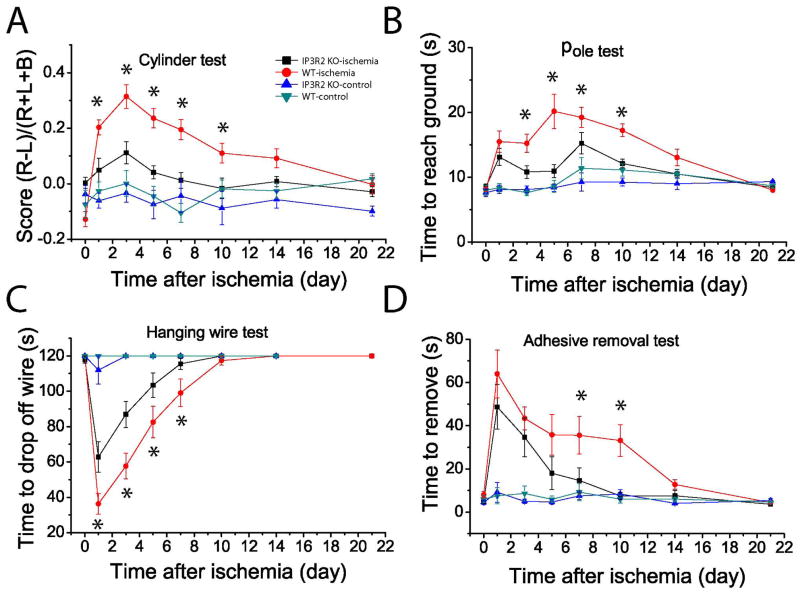

3.5. Deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 reduces behavioral deficits after PT

An important goal of neuroprotective research in ischemia is to improve long-term behavioral outcomes. Since our data showed that IP3R2 KO mice have a reduced infarct volume and tissue loss compared to WT mice after PT, we set out to determine whether there is a causal link to ischemia-induced behavioral deficits. We conducted a battery of behavioral tests including cylinder, hanging wire, pole, and adhesive removal tests. We started behavioral tests prior to PT to establish a baseline performance, and conducted the same tests 1, 3, 5, 10, 14 and 21 days after PT. The cylinder test was conducted to evaluate the asymmetricity of forelimb use for weight shifting during vertical exploration and assess motor deficits after an ischemic stroke [43]. Data analysis showed that IP3R2 KO mice exhibited less difference in the frequency of usage between non-impaired and impaired paws than WT mice after PT. Statistical differences of performance were observed on days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 post-ischemia (Fig. 8A). This can be explained by the fact that IP3R2 KO mice used their impaired forelimb more frequently than WT mice since they had less neuronal death and brain damage. The pole test was used to evaluate simple motor function after a stroke [55]. WT mice appeared to need more time to reach the ground than the KO mice at day 3, 5, 7 and 10 after PT, even though there was no significant difference after day 14 between the two groups (Fig. 8B). To evaluate the grasping ability and forelimb strength after ischemia, the hanging wire test was performed [43]. There was a significant difference between IP3R2 KO and WT mice at days 1, 3, 5 and 7 after ischemia (Fig. 8C). To further evaluate sensory-motor deficits involving the sensory-motor cortex, cortico-spinal tract and striatum after ischemia, we also performed the adhesive removal test [56]. Our data showed that IP3R2 KO mice needed significantly shorter time to remove the adhesive dots than WT mice on days 7 and 10 after PT (Fig. 8D). Notably, there was no difference in these tests between the two groups under non-ischemic conditions, suggesting that IP3R2 in astrocyte does not modulate motor function, concordant with a recent report [57]. Overall, our study on four different behavioral tests indicate that IP3R2 KO mice had significantly less behavioral deficits than WT mice over the time course of three weeks after PT.

Fig. 8. IP3R2 KO mice exhibit reduced functional deficits after PT.

Four behavioral tests, i.e., cylinder (A), hanging wire (B), pole (C) and adhesive removal (D) tests were performed on sham and ischemic mice to assess functional deficits and recovery of WT and IP3R2 KO mice over a time course of three weeks after PT. The value of day 0 is the data from pre-ischemic mice for the ischemic group in each test. N = 8 and 16 mice for control and ischemic mice of both groups. *p < 0.05, ANOVA test, compared between WT and IP3R2 KO mice at multiple time points after PT.

4. Discussion

In current study we investigated whether and how disruption of PLC/IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway in astrocytes would affect neuronal death, brain infarction and long-term histological and behavioral outcomes using IP3R2 KO mice and the PT-induced ischemia model. The following main findings were observed. First, deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 did not cause any change in astrocytic and neuronal populations nor in GFAP and GLT-1 levels in the mouse brain. In vivo 2-P imaging indeed showed that ATP-stimulated Ca2+ waves in astrocytes were absent in live IP3R2KO mice, while, interestingly, spontaneous Ca2+ activities in the processes of astrocytes were still observed. Second, IP3R2 KO mice exhibited reduced brain damage, neuronal death and tissue loss after PT as compared with WT mice. Third, deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 attenuated reactive astrogliosis, but not microglia activation. Fourth, behavioral tests demonstrated that IP3R2 KO mice exhibited less ischemia-induced functional deficits than WT mice. These results demonstrate that deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 is beneficial in protecting against neuronal death and brain damage and reducing behavioral deficits after ischemia, and suggest the involvement of the astrocytic PLC/IP3R2 Ca2+ signaling pathway in these processes.

IP3R2 KO mice originally were generated for studying Ca2+ signaling in atrial myocytes [26] and were later used for studying Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, neuron-glia interactions and neurovascular coupling in the CNS [9;10;25;45;58;59]; however, they were not well characterized in the brain [25;60]. In the current study, we demonstrated that IP3R2 was indeed deleted in astrocytes of IP3R2 KO mice and that global brain architecture, body weight, astrocytic and neuronal populations, GLT-1 and GFAP expression levels remained the same as that recorded for WT mice. Using 2-P in vivo imaging, we showed that there was no regenerative somatic Ca2+ wave in the astrocytic network of IP3R2 KO mice in the continuous presence of ATP, which further validated the absence of IP3R2 and IP3R2-mediated Ca2+ signaling in IP3R2 KO mice. Several studies using the same IP3R2 KO mice showed that astrocytic IP3R2 does not modulate synaptic activity, short- and long-lerm plasticity and neurovascular coupling [10;25;58;59]. Together, these findings suggest that astrocytic IP3R2-mediated Ca2+ signaling is not critical for neuronal function and has no cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous effects in the CNS under physiological conditions. However, a recent study also showed that IP3R2 KO mice display depression-like behaviors which was modulated by reduced astrocyte-derived ATP [60]. In contrast, others have shown that IP3R2 conditional KO (IP3R2 cKO) mice had no such behavioral alterations [57]. The different results from these two studies might result from the use of astrocyte-specific IP3R2 constitutive vs. conditional KO mice. The background of strains may have also contributed to these differing observations. In our study, IP3R2 KO and WT mice exhibited the same motor behaviors in cylinder, hanging wire, pole, and adhesive removal tests under non-ischemic conditions.

Enhanced astrocytic Ca2+ signaling has been demonstrated to induce the release of glutamate and D-serine that can stimulate and modulate NR2B-subunit-containing NMDA receptors [11;13;61–63]. Studies using brain slice preparations showed that group 1 mGluRs in astrocytes play a major role in interacting with neurons. They mediate Ca2+ increases in response to synaptically released glutamate [64;65], while their stimulation with agonist DHPG can induce the release of glutamate through a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway as well as modulate neuronal excitability through activation of NR2B-containing NMDARs characterized as SICs [11–14]. Moreover, MPEP can significantly inhibit CHPG and DHPG-stimulated Ca2+ increase in astrocytes in vivo and reduce neuronal excitation in brain slice preparations [12]. The mGluR5 selective antagonist MPEP and mGluR1 selective antagonist LY367385 can suppress whisker stimulation evoked astrocytic Ca2+ responses in vivo in mice [8]. Thus, Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes serves as a mediator of bidirectional interactions between neurons and astrocytes. Previously, we demonstrated for the first time that ischemia induces a prolonged and enhanced Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes which can be largely inhibited by mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP [6]; moreover, MPEP can reduce brain infarction after ischemia through suppression of Ca2+-dependent calpain activation [18]. The current study further showed that IP3R2 KO mice exhibited reduced brain infarction and neuronal cell death after PT as compared with WT mice. These studies led us to conclude that disruption of PLC/IP3R2 Ca2+ signaling pathway can reduce Ca2+-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes under ischemic conditions and consequently ameliorate glutamate excitotoxicity, neuronal death and brain damage. A recent study using brain slice recordings provided evidence that astrocyte-mediated glutamate release causes neuronal excitotoxicity under ischemic conditions [66]. Oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) induces neuronal SICs and IP3R2 KO mice exhibit lower frequency of SICs than WT mice. Consistent with our results, IP3R2 KO mice had smaller infarct volume than WT mice at 6 h after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), a very acute phase. Similarly, it has been reported that transgenic mice conditionally expressing dominant-negative SNARE (dn-SNARE) protein under control of the GFAP promoter exhibited a reduced PT-induced brain lesion and improved behavioral performance [67]. Their study suggests that these dnSNARE mice produced a neuroprotective effect through a decrease in Ca2+-dependent vesicular release of D-serine from astrocytes and reduced surface expression of neuronal NMDA receptors [67;68]. Thus, ischemia-induced Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes could mediate glutamate excitotoxicity through the activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in neurons, similar to what has been observed in the pathological condition of status epilepticus [12].

Although it has been reported that astrocytic mGluR5 is developmentally regulated with lower expression levels in adult mice than in neonatal mice [7], the mGluR5 inhibitor can largely inhibit ischemia-induced astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in adult mice, and OGD increases the frequency of SICs in brain slice preparations [6;66]. In addition, mGluR5 is upregulated in reactive astrocytes after OGD [69]. These studies suggest that mGluR5-mediated astrocytic Ca2+ increases could cause additional glutamate release and contribute to excitotoxicity under ischemic conditions.

In addition to Ca2+-dependent vesicular release of glutamate, volume-sensitive ion channels can also mediate glutamate release [70]. Glutamate and DHPG can increase astrocyte water permeability and swelling through the activation of mGluR5-mediated PLC/IP3R Ca2+ signaling pathway [71;72]. Brain edema, including cytotoxic and vasogenic edema, is significantly developed in the acute phase after ischemia [29]. Cytotoxic edema is characterized by swelling of different cell types in the brain, including astrocytes [73;74]. Thus, reduction of volume-sensitive ion channel-mediated glutamate release could be another mechanism that contributes to the difference in ischemia-induced neuronal death and brain damage between IP3R2 KO and WT mice.

Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling may play different roles in neuronal death and brain damage in different brain injury models. Zheng et al. reported that using a tiny ischemic lesion model generated by a single vessel laser irradiation, an increase in astrocytic Ca2+ can stimulate energy metabolism and ATP production in astrocytic mitochondria and, thus, reduces brain damage [16]. Similarly, in stab wound injury (SWI) model which also produces a tiny lesion, IP3R2 KO mice had increased neuronal loss as compared with WT mice [75]. It has been known that ketamine is an antagonist of NMDAR and is neuroprotective in brain injury [76], but, the different results cannot be explained by the use of ketamine/xylazine as anesthesia in the current study as WT mice exhibit higher frequency of NMDAR-mediated SICs than KO mice. The different results are likely due to the different stroke models, severity of brain injury and the post-ischemic time points for infarct volume measurements. Our current study discovered that astrocytic Ca2+ signals have different effects on neuronal death and brain damage in mild vs. severe brain injury models.

Our current study shows that the deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 attenuates GFAP+ reactive astrocytes in the chronic phase after PT (Fig. 7). In the SWI model, deletion of IP3R2 in astrocytes also attenuates reactive astrogliosis, and Ca2+-dependent up-regulation of N-cadherin in astrocytes is required for reactive astrogliosis and neuroprotection [75]. Activation of the Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFATs) transcription factor by Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin is another possible mechanism that enhances reactive astrogliosis as inhibition of NFATs can reduce astrocyte activation and cognitive performance in an Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) mouse model [77;78]. In addition to Ca2+-dependent pathways, other signaling pathways could also mediate reactive astrogliosis [52;79]. While reactive astrogliosis is a common phenomenon for various neural diseases including brain injury, they are highly dynamic in morphology, proliferation and gene expression after ischemia [29;50;51;80]. Although the mechanisms and signaling pathways by which astrocytes are activated might be different in different stages after brain injury, these studies indicate that Ca2+ signaling and its related pathways are the important regulators in reactive astrogliosis in ischemic stroke and other neurodegenerative diseases. Attenuation of reactive astrogliosis is associated with either increase or decrease in infarct lesion after ischemia [81;82]. Although we cannot arrive at a conclusion whether glial scar is beneficial or detrimental in neuronal and brain protection after ischemia, the current study suggests that attenuation of reactive astrogliosis resulting from the deletion of IP3R2 might exert a beneficial effect on the reduction of brain damage and functional deficits in IP3R2 KO mice experiencing ischemic stroke. It is interesting to observe that the populations of activated Iba1+ microglia are the same between the two groups, suggesting there is no non-cell-autonomous effect of astrocytic IP3R2 on reactive gliosis.

Although lesion size is the most precise outcome measure of tissue pathology, functional recovery is an essential measure of outcome and is typically used as a primary end-point in clinical trials. In PT model, the size and location of infarction can be controlled [28] and behavioral deficits can be observed if a large enough infarction is induced [29;30;83]. In the current study, we targeted ischemia in forelimbs somatosensory cortex, and we therefore conducted a battery of motor function behavioral tests including cylinder, hanging wire, pole, and adhesive removal tests [42;43;56] to determine the role of IP3R2 in functional deficit and recovery after PT. Consistent with the study from Petravicz et al [57], we showed that IP3R2 KO and WT mice exhibit the same behaviors in cylinder, hanging wire, pole, and adhesive removal tests under non-ischemic conditions (Fig. 8). In contrast to the non-ischemic condition, IP3R2 KO mice have significantly better performance than WT mice after PT, indicating that IP3R2 KO mice display less functional deficits or impairments than WT mice (Fig. 8). This is consistent with histological study showing that IP3R2 KO mice have a significant reduction in infarction and tissue loss than WT mice. Thus, our study revealed previously unknown role of IP3R2 in the reduction of functional deficits after ischemia. Although there are multiple factors that affect ischemia-induced functional deficits, our results showing that IP3R2 KO mice have reduced reactive astrogliosis suggest that mitigating reactive astrogliosis may have beneficial effects on improving behavioral outcomes.

In our previous study, we found that astrocytes exhibit spontaneous Ca2+ increases in the processes and soma in anesthetized and head-fixed, awake mice; these fast Ca2+ increases in the processes are not synchronized with somatic Ca2+ increases [12]. Here, we show that under the same imaging conditions IP3R2 KO mice abolished receptor-stimulated somatic Ca2+ waves in astrocytes, but these mice still exhibited spontaneous Ca2+ transients in the processes of astrocytes (Fig 3). In fully awake, non-anesthetized and head fixed mice, spontaneous Ca2+ transients in IP3R2 KO mice were not markedly different from WT [45]. Similarly, the startle-evoked somatic Ca2+ response was almost abolished in IP3R2 KO mice, whereas the responses in the processes were increased in both IP3R2 KO and WT mice, but with no significant difference between them. Although the molecular nature of Ca2+ activities in the cell processes remain to be elucidated, these studies suggest that there are currently unknown IP3R2-independent Ca2+ signaling pathways in the astrocytes that might be important for functional modulation in the CNS. As reported in a recent study on the olfactory bulb, Ca2+ increases in astrocytic processes are suggested as a potential regulator of neurovascular coupling as these Ca2+ signals precede the onset of functional hyperemia [84]. For future study in ischemia, it will be important to determine whether there is any alteration of these IP3R2-independent Ca2+ transients in astrocytic processes and whether mild and severe brain injuries induce different frequencies and magnitudes of Ca2+ signals in soma and processes. Resolving these issues could lead to a better understanding of why IP3R2 KO mice have a smaller lesion in severe focal ischemia, but a larger lesion than WT mice in mild focal ischemia. Eventually, we will delineate the roles of somatic and process Ca2+ signals in astrocytes during brain damage and functional impairment after ischemia.

In summary, the current study using IP3R2 KO mice demonstrates that although deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 does not cause any alterations in brain cytoarchitecture, astrocytic and neuronal populations, GFP and GLT-1 levels and behavioral function under physiological conditions, it can ameliorate brain damage and neuronal death as well as attenuate reactive astrogliosis and tissue loss after PT. Significantly, the deletion of astrocytic IP3R2 also reduced ischemia-induced functional deficits. Our study revealed previously unknown roles of astrocytic IP3R2-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway in non-cell-autonomous neuronal and brain protection after ischemic stroke and indicates that targeting the astrocytic Ca2+ signaling pathway might be a promising strategy for stroke therapy. In future studies, it will be important to determine whether somatic and process Ca2+ signals plays different roles in neuronal death and brain damage and whether astrocytes exhibit different properties of Ca2+ signaling during severe and mild ischemic strokes.

Research Highlights.

IP3R2 KO mice exhibited normal brain cytoarchitecture, the same densities of mature astrocytes and neurons, the same GFAP and GLT-1 levels as WT mice.

IP3R2 KO mice did not exhibit ATP-induced Ca2+ waves in vivo in the astrocytic network, but exhibit spontaneous Ca2+ increases in astrocytic processes.

IP3R2 KO mice had smaller infarction than WT mice in acute and chronic phases of ischemia. These KO mice also exhibited less neuronal apoptosis, reactive astrogliosis, and tissue loss than WT mice.

IP3R2 KO mice exhibited reduced functional deficits after PT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01NS069726] and the American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant (SDG) [0735133N] to SD.

Footnotes

Author contributions

HL, YX and NZ generated ischemic mice using the PT model, conducted histological and immunostaining study, fluorescent imaging and data analysis. YX also did the Western blot analysis and 2-P imaging. HL and YY did behavioral tests. QZ did Western blot analysis. SD conceived the study, supervised and participated in designing the experiments and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Iadecola C, Anrather J. Stroke research at a crossroad: asking the brain for directions. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1363–1368. doi: 10.1038/nn.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dirnagl U, Endres M. Found in Translation: Preclinical Stroke Research Predicts Human Pathophysiology, Clinical Phenotypes, and Therapeutic Outcomes. Stroke. 2014;45:1510–1518. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haydon PG. GLIA: listening and talking to the synapse. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:185–193. doi: 10.1038/35058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte Control of Synaptic Transmission and Neurovascular Coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding S. In vivo astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in health and brain disorders. Future Neurology. 2013;8:529–554. doi: 10.2217/fnl.13.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding S, Wang T, Cui W, et al. Photothrombosis ischemia stimulates a sustained astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in vivo. GLIA. 2009;57:767–776. doi: 10.1002/glia.20804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun W, McConnell E, Pare JF, et al. Glutamate-Dependent Neuroglial Calcium Signaling Differs Between Young and Adult Brain. Science. 2013;339:197–200. doi: 10.1126/science.1226740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Lou N, Xu Q, et al. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling evoked by sensory stimulation in vivo. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:816–823. doi: 10.1038/nn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thrane AS, Rangroo Thrane V, Zeppenfeld D, et al. General anesthesia selectively disrupts astrocyte calcium signaling in the awake mouse cortex. PNAS. 2012;109:18974–18979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nizar K, Uhlirova H, Tian P, et al. In vivo Stimulus-Induced Vasodilation Occurs without IP3 Receptor Activation and May Precede Astrocytic Calcium Increase. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:8411–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3285-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding S, Fellin T, Zhu Y, et al. Enhanced Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals Contribute to Neuronal Excitotoxicity after Status Epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10674–10684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2001-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angulo MC, Kozlov AS, Charpak S, Audinat E. Glutamate released from glial cells synchronizes neuronal activity in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6920–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0473-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Ascenzo M, Fellin T, Terunuma M, et al. mGluR5 stimulates gliotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. PNAS. 2007;104:1995–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuchibhotla KV, Lattarulo CR, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Synchronous Hyperactivity and Intercellular Calcium Waves in Astrocytes in Alzheimer Mice. Science. 2009;323:1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1169096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng W, Talley Watts L, Holstein DM, Wewer J, Lechleiter JD. P2Y1R-initiated, IP3R-dependent stimulation of astrocyte mitochondrial metabolism reduces and partially reverses ischemic neuronal damage in mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:600–611. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choo AM, Miller WJ, Chen YC, et al. Antagonism of purinergic signalling improves recovery from traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2013;136:65–80. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Zhang N, Sun G, Ding S. Inhibition of the group I mGluRs reduces acute brain damage and improves long-term histological outcomes after photothrombosis-induced ischaemia. ASN NEURO. 2013:5. doi: 10.1042/AN20130002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding S. Ca2+ Signaling in Astrocytes and its Role in Ischemic Stroke. In: Parpura V, Schousboe A, Verkhratsky A, editors. Glutamate and ATP at the Interface of Metabolism and Signaling in the Brain. Springer International Publishing; 2014. pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nedergaard M, Rodroguez JJ, Verkhratsky A. Glial calcium and diseases of the nervous system. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verkhratsky A, Rodroguez JJ, Parpura V. Calcium signalling in astroglia. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2012;353:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertle DN, Yeckel MF, Hertle DN, Yeckel MF. Distribution of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isotypes and ryanodine receptor isotypes during maturation of the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2007;150:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holtzclaw LA, Pandhit S, Bare DJ, et al. Astrocytes in adult rat brain express type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. GLIA. 2002;39:69–84. doi: 10.1002/glia.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharp AH, Nucifora FC, Jr, Blondel O, et al. Differential cellular expression of isoforms of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors in neurons and glia in brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;406:207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petravicz J, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Loss of IP3 Receptor-Dependent Ca2+ Increases in Hippocampal Astrocytes Does Not Affect Baseline CA1 Pyramidal Neuron Synaptic Activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4967–4973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Zima AV, Sheikh F, Blatter LA, Chen J. Endothelin-1-Induced Arrhythmogenic Ca2+ Signaling Is Abolished in Atrial Myocytes of Inositol-1,4,5-Trisphosphate(IP3)-Receptor Type 2-Deficient Mice. Circ Res. 2005;96:1274–1281. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000172556.05576.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Xie Y, Wang T, et al. Neuronal protective role of PBEF in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1962–1971. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang T, Cui W, Xie Y, et al. Controlling the Volume of the Focal Cerebral Ischemic Lesion through Photothrombosis. American Journal of Biomedical Science. 2010;2:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Zhang N, Lin H, et al. Histological, cellular and behavioral assessments of stroke outcomes after photothrombosis-induced ischemia in adult mice. BMC Neuroscience. 2014;15:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarkson AN, Huang BS, MacIsaac SE, Mody I, Carmichael ST. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature. 2010;468:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature09511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tennant KA, Adkins DL, Donlan NA, et al. The Organization of the Forelimb Representation of the C57BL/6 Mouse Motor Cortex as Defined by Intracortical Microstimulation and Cytoarchitecture. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:865–876. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown CE, Li P, Boyd JD, Delaney KR, Murphy TH. Extensive Turnover of Dendritic Spines and Vascular Remodeling in Cortical Tissues Recovering from Stroke. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4101–4109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4295-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Zhang N, Sun G, Ding S. Inhibition of the group I mGluRs reduces acute brain damage and improves long-term histological outcomes after photothrombosis-induced ischemia. ASN NEURO. 2013;5:e00117. doi: 10.1042/AN20130002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Xiong X, Ouyang Y, Barreto G, Giffard R. Heat shock protein 72 (Hsp72) improves long term recovery after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;488:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie Y, Wang T, Sun GY, Ding S. Specific disruption of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling pathway in vivo by adeno-associated viral transduction. Neuroscience. 2010;170:992–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Li H, Ding S. The Effects of NAD+ on Apoptotic Neuronal Death and Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Function after Glutamate Excitotoxicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15:1012–1022. doi: 10.3390/ijms151120449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, You Y, Li X, et al. Brain Injury Does Not Alter the Intrinsic Differentiation Potential of Adult Neuroblasts. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5075–5087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0201-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding S. In Vivo Imaging of Ca2+ Signaling in Astrocytes Using Two-Photon Laser Scanning Fluorescent Microscopy. In: Milner R, editor. Astrocytes. Humana Press; 2012. pp. 545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S, Boyd J, Delaney K, Murphy TH. Rapid Reversible Changes in Dendritic Spine Structure In Vivo Gated by the Degree of Ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5333–5338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1085-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy TH, Li P, Betts K, Liu R. Two-Photon Imaging of Stroke Onset In Vivo Reveals That NMDA-Receptor Independent Ischemic Depolarization Is the Major Cause of Rapid Reversible Damage to Dendrites and Spines. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1756–1772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5128-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clement EA, Richard A, Thwaites M, Ailon J, Peters S, Dickson CT. Cyclic and Sleep-Like Spontaneous Alternations of Brain State Under Urethane Anaesthesia. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balkaya M, Krober J, Gertz K, Peruzzaro S, Endres M. Characterization of long-term functional outcome in a murine model of mild brain ischemia. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2013;213:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Blizzard KK, Zeng Z, DeVries AC, Hurn PD, McCullough LD. Chronic behavioral testing after focal ischemia in the mouse: functional recovery and the effects of gender. Experimental Neurology. 2004;187:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Kerr JN, Helmchen F. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nature Methods. 2004;1:31–37. doi: 10.1038/nmeth706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan R, Huang BS, Venugopal S, et al. Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes from Ip3r2−/− mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:708–717. doi: 10.1038/nn.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu F, Schafer DP, McCullough LD. TTC, Fluoro-Jade B and NeuN staining confirm evolving phases of infarction induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2009;179:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haupt C, Witte OW, Frahm C. Up-regulation of Connexin 43 in the glial scar following photothrombotic ischemic injury. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2007;35:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Jin K, Chen M, et al. Early Detection of DNA Strand Breaks in the Brain After Transient Focal Ischemia: Implications for the Role of DNA Damage in Apoptosis and Neuronal Cell Death. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;69:232–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding S. Dynamic reactive astrocytes after focal ischemia. Neural Regenerative Research. 2014;9:2048–2052. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.147929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choudhury GR, Ding S. Reactive astrocytes and therapeutic potential in focal ischemic stroke. Neurobiology of Disease. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.05.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burda J, Sofroniew M. Reactive Gliosis and the Multicellular Response to CNS Damage and Disease. Neuron. 2014;81:229–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson MA, Ao Y, Sofroniew MV. Heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes. Neuroscience Letters. 2014;565:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barreto GE, Sun X, Xu L, Giffard RG. Astrocyte Proliferation Following Stroke in the Mouse Depends on Distance from the Infarct. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balkaya M, Krober JM, Rex A, Endres M. Assessing post-stroke behavior in mouse models of focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:330–338. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouet V, Boulouard M, Toutain J, et al. The adhesive removal test: a sensitive method to assess sensorimotor deficits in mice. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:1560–1564. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petravicz J, Boyt KM, McCarthy KD, Astrocyte IP. 3R2-dependent Ca2+ signaling is not a major modulator of neuronal pathways governing behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014:8. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonder DE, McCarthy KD. Astrocytic Gq-GPCR-Linked IP3R-Dependent Ca2+ Signaling Does Not Mediate Neurovascular Coupling in Mouse Visual Cortex In Vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:13139–13150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2591-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal Short- and Long-Term Plasticity Are Not Modulated by Astrocyte Ca2+ Signaling. Science. 2010;327:1250–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.1184821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao X, Li LP, Wang Q, et al. Astrocyte-derived ATP modulates depressive-like behaviors. Nat Med. 2013;19:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6822–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parpura V, Haydon PG. Physiological astrocytic calcium levels stimulate glutamate release to modulate adjacent neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:8629–8634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aguado F, Espinosa-Parrilla JF, Carmona MA, Soriano E. Neuronal Activity Regulates Correlated Network Properties of Spontaneous Calcium Transients in Astrocytes In Situ. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9430–9444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09430.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porter JT, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Intracellular Calcium Oscillations in Astrocytes: A Highly Plastic, Bidirectional Form of Communication between Neurons and Astrocytes In Situ. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07817.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong Qp, He Jq, Chai Z. Astrocytic Ca2+ waves mediate activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in hippocampal neurons to aggravate brain damage during ischemia. Neurobiology of Disease. 2013;58:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hines DJ, Haydon PG. Inhibition of a SNARE-Sensitive Pathway in Astrocytes Attenuates Damage following Stroke. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:4234–4240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5495-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deng Q, Terunuma M, Fellin T, Moss SJ, Haydon PG. Astrocytic activation of A1 receptors regulates the surface expression of NMDA receptors through a Src kinase dependent pathway. GLIA. 2011;59:1084–1093. doi: 10.1002/glia.21181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paquet M, Ribeiro F, Guadagno J, Esseltine J, Ferguson S, Cregan S. Role of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 signaling and homer in oxygen glucose deprivation-mediated astrocyte apoptosis. Molecular Brain. 2013;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takano T, Kang J, Jaiswal JK, et al. Receptor-mediated glutamate release from volume sensitive channels in astrocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:16466–16471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506382102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gunnarson E, Axehult G, Baturina G, et al. Identification of a molecular target for glutamate regulation of astrocyte water permeability. GLIA. 2008;56:587–596. doi: 10.1002/glia.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gunnarson E, Song Y, Kowalewski JM, et al. Erythropoietin modulation of astrocyte water permeability as a component of neuroprotection. PNAS. 2009;106:1602–1607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812708106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Benesova J, Hock M, Butenko O, Prajerova I, Anderova M, Chvatal A. Quantification of astrocyte volume changes during ischemia in situ reveals two populations of astrocytes in the cortex of GFAP/EGFP mice. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:96–111. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lukaszevicz AC, Sampaio N, Guegan C, et al. High Sensitivity of Protoplasmic Cortical Astroglia to Focal Ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:289–298. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanemaru K, Kubota J, Sekiya H, Hirose K, Okubo Y, Iino M. Calcium-dependent N-cadherin up-regulation mediates reactive astrogliosis and neuroprotection after brain injury. PNAS. 2013;110:11612–11617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300378110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sleigh J, Harvey M, Voss L, Denny B. Ketamine-More mechanisms of action than just NMDA blockade. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2014;4:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Furman JL, Sama DM, Gant JC, et al. Targeting Astrocytes Ameliorates Neurologic Changes in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:16129–16140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2323-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Norris CM, Kadish I, Blalock EM, et al. Calcineurin Triggers Reactive/Inflammatory Processes in Astrocytes and Is Upregulated in Aging and Alzheimer’s Models. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:4649–4658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0365-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sofroniew M, Vinters H. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, et al. Genomic Analysis of Reactive Astrogliosis. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:6391–6410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen J, Ishii Y, Xu G, et al. PDGFR-β as a positive regulator of tissue repair in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:353–367. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bao Y, Qin L, Kim E, et al. CD36 is involved in astrocyte activation and astroglial scar formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1567–1577. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clarkson AN, Lopez-Valdes HE, Overman JJ, Charles AC, Brennan KC, Thomas Carmichael S. Multimodal examination of structural and functional remapping in the mouse photothrombotic stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:716–723. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Otsu Y, Couchman K, Lyons DG, et al. Calcium dynamics in astrocyte processes during neurovascular coupling. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:210–218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]