Abstract

Lower-extremity veins have efficient wall structure and function and competent valves that permit upward movement of deoxygenated blood toward the heart against hydrostatic venous pressure. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play an important role in maintaining vein wall structure and function. MMPs are zinc-binding endopeptidases secreted as inactive pro-MMPs by fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle (VSM), and leukocytes. Pro-MMPs are activated by various activators including other MMPs and proteinases. MMPs cause degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen and elastin, and could have additional effects on the endothelium, as well as VSM cell migration, proliferation, Ca2+ signaling, and contraction. Increased lower-extremity hydrostatic venous pressure is thought to induce hypoxia-inducible factors and other MMP inducers/activators such as extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, prostanoids, chymase, and hormones, leading to increased MMP expression/activity, ECM degradation, VSM relaxation, and venous dilation. Leukocyte infiltration and inflammation of the vein wall cause further increases in MMPs, vein wall dilation, valve degradation, and different clinical stages of chronic venous disease (CVD), including varicose veins (VVs). VVs are characterized by ECM imbalance, incompetent valves, venous reflux, wall dilation, and tortuosity. VVs often show increased MMP levels, but may show no change or decreased levels, depending on the VV region (atrophic regions with little ECM versus hypertrophic regions with abundant ECM) and MMP form (inactive pro-MMP versus active MMP). Management of VVs includes compression stockings, venotonics, and surgical obliteration or removal. Because these approaches do not treat the causes of VVs, alternative methods are being developed. In addition to endogenous tissue inhibitors of MMPs, synthetic MMP inhibitors have been developed, and their effects in the treatment of VVs need to be examined.

Introduction

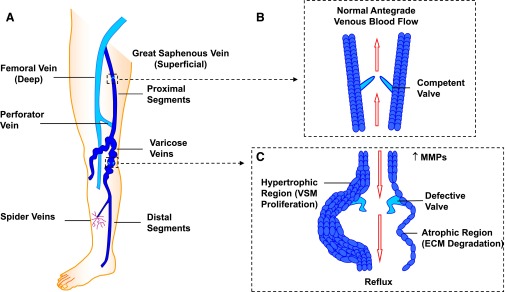

Veins are a large network of vessels that transfer deoxygenated blood from different tissues to the heart. In the lower extremity, an intricate system of superficial and deep veins is responsible for the transfer of blood against hydrostatic venous pressure. Superficial veins include the small saphenous vein, which is located in the back of the leg and runs from the ankle until it meets the popliteal vein at the saphenopopliteal junction, and the great saphenous vein, which is located in the medial side of the leg and runs from the ankle until it meets the common femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction. Deep veins include the tibial, popliteal, femoral, deep femoral, and common femoral veins (Recek, 2006). In all parts of the lower extremity other than the foot, blood flows from the superficial veins, which carry blood from the skin and subcutaneous tissue, to the deep veins, which are embedded in the muscles and carry blood from all other parts of the leg (Recek, 2006; Lim and Davies, 2009) (Fig. 1). The movement of blood from the superficial veins to deep veins and toward the heart is guided by bicuspid valves that protrude from the inner wall and ensure blood movement in one direction. Muscle contractions in the calf, foot, and thigh also help to drive the blood toward the heart and against gravity and the high hydrostatic venous pressure, which could reach 90–100 mm Hg at the ankle in the standing position (Recek, 2006).

Fig. 1.

The lower-extremity venous system and changes in VVs. The lower extremity has an intricate system of superficial and deep veins connected by perforator veins (A), and venous valves that allow blood flow in the antegrade direction toward the heart (B). Vein dysfunction may manifest as small spider veins and could progress to large dilated VVs with incompetent valves (C). VVs mainly show atrophic regions where an increase in MMPs increases ECM degradation, but could also show hypertrophic regions in which increased MMPs and ECM degradation would promote VSMC proliferation, leading to tortuosity, dilation, defective valves, and venous reflux (C).

Veins are relatively thin compared with arteries, but the vein wall still has three histologic layers. The innermost layer, the tunica intima, is made of endothelial cells (ECs) which are in direct contact with blood flow. The tunica media contains a few layers of vascular smooth muscle (VSM) and is separated from the intima by the internal elastic lamina. The outermost layer, the adventitia, contains fibroblasts embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM) of proteins such as collagen and elastin (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007).

The ECM and other components of the vein wall are modulated by different ions, molecules, and enzymes. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are endopeptidases that are often recognized for their ability to degrade ECM components and therefore play a major role in venous tissue remodeling. MMPs may also affect bioactive molecules on the cell surface and regulate the cell environment through G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). MMPs may promote cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation and could play a role in cell apoptosis, immune response, tissue healing, and angiogenesis. Alterations in MMP expression and activity occur in normal biologic processes such as pregnancy, but have also been implicated in vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and aneurysms. MMPs also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of chronic venous disease (CVD) and varicose veins (VVs). VVs are a common health problem characterized by unsightly twisted and dilated veins in the lower extremities. If untreated, VVs may cause many complications, including thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis, and venous leg ulcer, making it important to carefully examine the pathogenetic mechanisms involved to develop better treatment options.

In this review, we will use data reported in PubMed and other scientific databases as well as data from our laboratory to provide an overview of MMP structure, substrates, and tissue distribution. We will then discuss CVD, the structural and functional abnormalities in VVs, the changes in MMP levels, and the potential factors that could change MMP expression/activity in VVs, including venous hydrostatic pressure, inflammation, hypoxia, and other MMP activators and inducers. We will also discuss the mechanisms of MMP actions and how they could cause ECM abnormalities, and EC and VSM dysfunction leading to venous dilation and VV formation. We will end the review by describing some of the current approaches used for the treatment of VVs, and explore the potential benefits of endogenous tissue inhibitors of MMP (TIMPs) and synthetic MMP inhibitors as new tools for the management of VVs.

MMP Structure

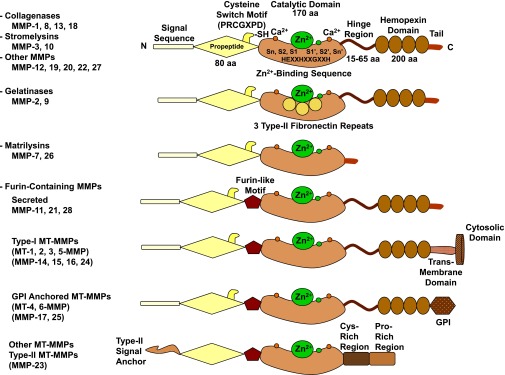

MMPs were discovered in the early 1960s as a collagen proteolytic activity during the ECM protein degradation associated with resorption of the tadpole tail (Gross and Lapiere, 1962). MMPs are endopeptidases, also called matrixins, and belong to the metzincins superfamily of proteases. MMPs are highly homologous, multidomain, zinc (Zn2+)-dependent metalloproteinases that degrade various components of ECM. Generally, MMPs have a propeptide sequence, a catalytic metalloproteinase domain, a hinge region (linker peptide), and a hemopexin domain (Fig. 2). Additionally, all MMPs have 1) homology to collagenase-1 (MMP-1); 2) a prodomain cysteine switch motif PRCGXPD whose cysteine sulfhydryl group chelates the active-site Zn2+, keeping MMPs in the pro-MMP zymogen form; and 3) a Zn2+-binding motif to which Zn2+ is bound by three histidines from the conserved sequence HEXXHXXGXXH, a conserved glutamate, and a conserved methionine from the sequence XBMX (Met-turn) that is located eight residues downstream from the Zn2+-binding motif and supports the structure surrounding the catalytic Zn2+ (Bode et al., 1999; Visse and Nagase, 2003) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Major subtypes and structures of MMPs. A typical MMP consists of a propeptide, a catalytic metalloproteinase domain, a linker peptide (hinge region), and a hemopexin domain. The propeptide has a cysteine switch PRCGXPD whose cysteine sulfhydryl (–SH) group chelates the active site Zn2+, keeping the MMP in the latent pro-MMP zymogen form. The catalytic domain contains the Zn2+-binding motif HEXXHXXGXXH; two Zn2+ ions (one catalytic and one structural); specific S1, S2, …, Sn and S1′, S2′, …, Sn′pockets, which confer specificity; and two or three Ca2+ ions for stabilization. Some MMPs show exceptions in their structures. Gelatinases have three type II fibronectin repeats in the catalytic domain. Matrilysins have neither a hinge region nor a hemopexin domain. Furin-containing MMPs such as MMP-11, -21, and -28 have a furin-like proprotein convertase recognition sequence in the propeptide C terminus. MMP-28 has a slightly different cysteine switch motif PRCGVTD. MT-MMPs typically have a transmembrane domain and a cytosolic domain. MMP-17 and -25 have a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. MMP-23 lacks the consensus PRCGXPD motif, has a cysteine residue located in a different sequence ALCLLPA, may remain in the latent inactive proform through its type II signal anchor, and has a cysteine-rich region and an immunoglobulin-like proline-rich region. aa, amino acid.

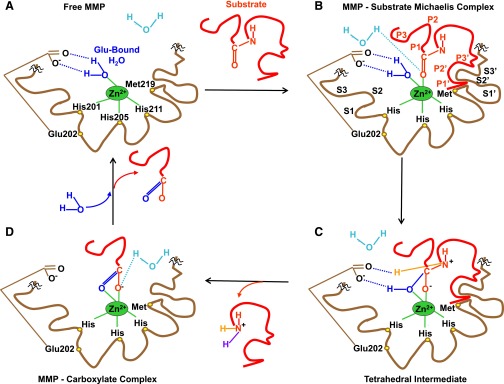

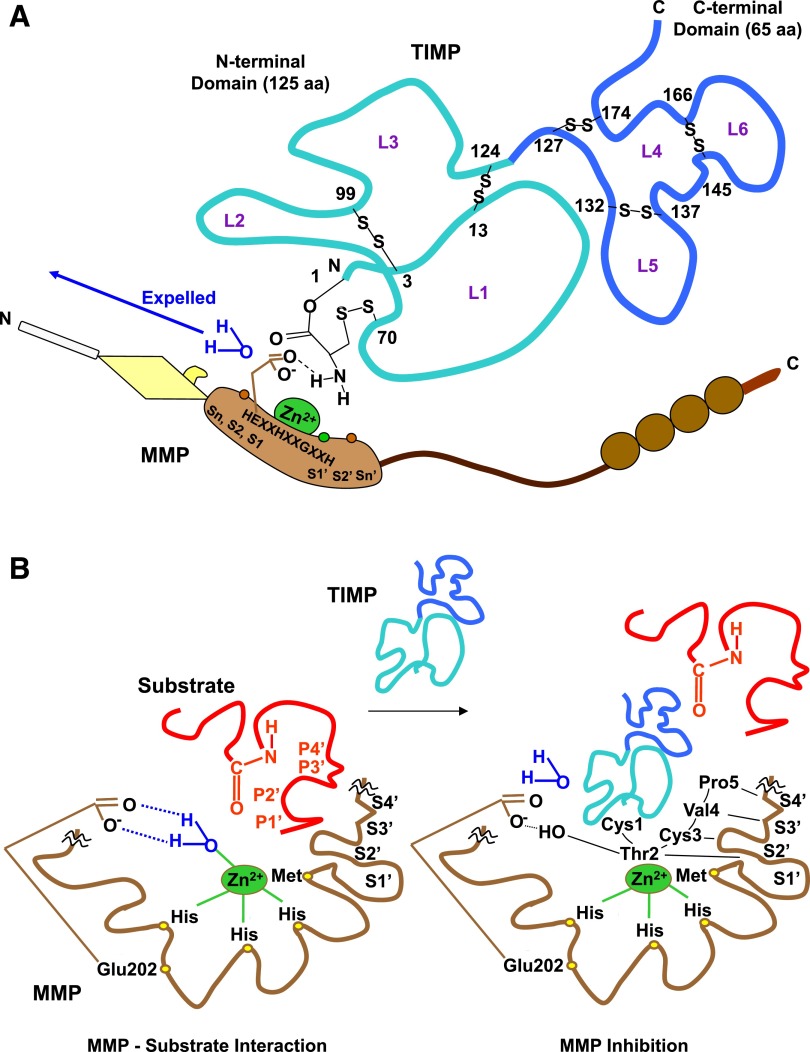

Fig. 3.

MMP-substrate interaction. For simplicity, MMP-3 is used as a prototype, and only the catalytic domain is shown, with the rest of the MMP structure interrupted by squiggles. (A) In preparation for substrate binding, an incoming H2O molecule is polarized between the free MMP basic Glu202 and acidic Zn2+. Zn2+ is localized in the MMP HEXXHXXGXXH motif by binding imidazole rings from three histidines (His201, His205, His211), whereas Met219 in the conserved XBMX Met-turn serves as a hydrophobic base to support the structure surrounding the catalytic Zn2+. (B) Using H+ from free H2O, the substrate carbonyl binds to Zn2+, forming a Michaelis complex. MMP S1, S2, S3, ..., Sn pockets on the left side of Zn2+ and primed S1′, S2′, S3′, ..., Sn′ pockets on the right side of Zn2+ confer binding specificity to substrate P1, P2, P3, ..., Pn and P1′, P2′, P3′, ..., Pn′ substituents, respectively. S1 and S3 are located away from the catalytic center, whereas S2 is close to Zn2+. (C) Substrate-bound H2O is freed. Zn2+-bound O from Glu-bound H2O performs a nucleophilic attack on substrate carbon, and Glu202 abstracts a proton from Glu-bound H2O to form an N–H bond with substrate N, thus forming a tetrahedral intermediate. (D) Free H2O is taken up, and the second proton from Glu-bound H2O is transferred to the substrate, forming another N–H bond. This allows the substrate scissile C–N bond to break, releasing the N portion of the substrate and forming an MMP-carboxylate complex. Another free H2O is taken up, releasing the remaining carboxylate portion of the substrate and the free MMP (A). The positions of conserved His and Glu vary in different MMPs.

Since its discovery, the MMP family has grown to 28 members in vertebrates, at least 23 in humans, and 14 in blood vessels (Visse and Nagase, 2003) (Table 1). Based on their substrates and the organization of their different domains, MMPs are classified into collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins, membrane-type MMPs (MT-MMPs), and other MMPs. Different classes of MMPs may have specific structural features that may vary from the prototypical MMP structure (Pei et al., 2000; English et al., 2001; Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013) (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Members of the MMP family, their distribution in vascular tissues and other representative tissues, and examples of their substrates

| MMP (Other Name) Cromosome | Molecular Mass, Pro/Active | Distribution | Collagen Substrates | Noncollagen ECM Substrates | Nonstructural ECM Component Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | |||||

| Collagenases | |||||

| MMP-1 (collagenase-1) | 55/45 | Platelets, endothelium, intima, SMCs, fibroblasts, vascular adventitia, VVs (interstitial/fibroblast collagenase) | I, II, III, VII, VIII, X, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, nidogen, perlecan, proteoglycan link protein, serpins, tenascin-C, versican | α1-antichymotrypsin, α1-antitrypsin, α1-proteinase inhibitor, IGF-BP-3, -5, IL-1β, L-selectin, ovostatin, pro-TNF-α peptide, SDF-1 |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-8 (collagenase-2) | 75/58 | Macrophages, neutrophils (PMNL collagenase) | I, II, III, V, VII, VIII, X, gelatin | Aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen | α2-antiplasmin, pro-MMP-8 |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-13 (collagenase-3) | 60/48 | SMCs, macrophages, VVs, pre-eclampsia, breast cancer | I, II, III, IV, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, fibronectin, laminin, perlecan, tenascin | Plasminogen activator 2, pro-MMP-9, -13, SDF-1 |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-18 (collagenase-4) | 70/53 | Xenopus (amphibian, Xenopus collagenase) | I, II, III, gelatin | α1-antitrypsin | |

| 12q14 | Human heart, lung, colon | ||||

| Gelatinases | |||||

| MMP-2 (gelatinase-A, type IV collagenase) | 72/66 | Platelets, endothelium, VSM, adventitia, aortic aneurysm, VVs | I, II, III, IV, V, VII, X, XI, gelatin | Aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, proteoglycan link protein, versican | Active MMP-9, -13, FGF-R1, IGF-BP-3, -5, IL-1β, pro-TNF-α, TGF-β |

| 16q13-q21 | |||||

| MMP-9 (gelatinase-B, type IV collagenase) | 92/86 | Endothelium, VSM, adventitial microvessels, macrophages, aortic aneurysm, VVs | IV, V, VII, X, XIV, gelatin | Aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, proteoglycan link protein, versican | CXCL5, IL-1β, IL2-R, plasminogen, pro-TNF-α, SDF-1, TGF-β |

| 20q11.2-q13.1 | |||||

| Stromelysins | |||||

| MMP-3 (stromelysin-1) | 57/45 | Platelets, endothelium, intima, VSM, coronary artery disease, hypertension, VVs, synovial fibroblasts, tumor invasion | II, III, IV, IX, X, XI, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, decorin, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, perlecan, proteoglycan, proteoglycan link protein, versican | α1-antichymotrypsin, α1-proteinase inhibitor, antithrombin III, E-cadherin, fibrinogen, IGF-BP-3, L-selectin, ovostatin, pro-HB-EGF, pro-IL-1β, pro-MMP-1, -8, -9, pro-TNF-α, SDF-1 |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-10 (stromelysin-2) | 57/44 | Atherosclerosis, uterine, pre-eclampsia, arthritis, carcinoma cells | III, IV, V, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen | Pro-MMP-1, -8, -10 |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-11 (stromelysin-3) | 51/44 | Uterine, brain, angiogenesis | Does not cleave | Aggrecan, fibronectin, laminin | α1-antitrypsin, α1-proteinase inhibitor, IGF-BP-1 |

| 22q11.23 | |||||

| Matrilysins | |||||

| MMP-7 (matrilysin-1) | 29/20 | Endothelium, intima, VSM, uterine, VVs | IV, X, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, elastin, enactin, fibronectin, laminin, proteoglycan link protein | α2-antiplasmin, β4 integrin, decorin, defensin, E-cadherin, Fas-ligand, plasminogen, pro-MMP-2, -7, -8, pro-TNF-α, syndecan, transferrin |

| 11q21-q22 | |||||

| MMP-26 (matrilysin-2, endometase) | 28/19 | Breast cancer cells, human endometrial tumor | IV, gelatin | Casein, fibrinogen, fibronectin | β1-proteinase inhibitor, fibrin, fibronectin, pro-MMP-2 |

| 11p15 | |||||

| Membrane Type | |||||

| MMP-14 (MT1-MMP) | 66/56 | Platelets, VSM, human fibroblasts, uterine, brain, angiogenesis | I, II, III, gelatin | Aggrecan, elastin, fibrin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, perlecan, proteoglycan, tenascin, vitronectin | αvβ3 integrin, CD44, pro-MMP-2, -13, pro-TNF-α, SDF-1, tissue transglutaminase |

| 14q11-q12 | |||||

| MMP-15 (MT2-MMP) | 72/50 | Human fibroblasts, leukocytes, pre-eclampsia | I, gelatin | Aggrecan, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, perlecan, tenascin, vitronectin | Pro-MMP-2, -13, tissue transglutaminase |

| 16q13 | |||||

| MMP-16 (MT3-MMP) | 64/52 | Human leukocytes, angiogenesis | I | Aggrecan, casein, fibronectin, laminin, perlecan, vitronectin | Pro-MMP-2, -13 |

| 8q21.3 | |||||

| MMP-17 (MT4-MMP) | 57/53 | Brain, breast cancer | Gelatin | Fibrin | |

| 12q24.3 | |||||

| MMP-24 (MT5-MMP) | 57/53 | Leukocytes, cerebellum, astrocytoma, glioblastoma | Gelatin | Chondroitin sulfate, dermatin sulfate, fibrin, fibronectin | Pro-MMP-2, -13 |

| 20q11.2 | |||||

| MMP-25 (MT6-MMP) | 34/28 | Leukocytes (leukolysin), anaplastic astrocytomas, glioblastomas | IV, gelatin | Fibrin, fibronectin, pro-MMP-2 | |

| 16p13.3 | |||||

| Other MMPs | |||||

| MMP-12 (metalloelastase) | |||||

| 11q22.3 | 54/45-22 | SMCs, fibroblasts, macrophages | IV, gelatin | Casein, elastin, fibronectin, laminin | Plasminogen |

| MMP-19 (RASI-1) | 54/45 | Liver | I, IV, gelatin | Aggrecan, casein, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, tenascin | |

| 12q14 | |||||

| MMP-20 (enamelysin) | 54/22 | Tooth enamel | V | Aggrecan, cartilage oligomeric protein, amelogenin | |

| 11q22.3 | |||||

| MMP-21 (Xenopus-MMP) | 62/49 | Fibroblasts, macrophages, human placenta | α1-antitrypsin | ||

| 10q26.13 | |||||

| MMP-22 (chicken-MMP) | 51 | Chicken fibroblasts | Gelatin | ||

| 1p36.3 | |||||

| MMP-23 (CA-MMP) | 28/19 | Ovary, testis, prostate | Gelatin | ||

| 1p36.3 | Other (type II) MT-MMP | ||||

| MMP-27 (human MMP-22 homolog) | Leukocytes, macrophages, heart, kidney, endometrium, menstruation, bone, osteoarthritis, breast cancer | ||||

| 11q24 | |||||

| MMP-28 (epilysin) | 56/45 | Skin keratinocytes | Casein | ||

| 17q21.1 |

CA-MMP, cysteine array MMP; CXCL5, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5; FGF-R1, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; IGF-BP, insulin-like growth factor binding protein; IL, interleukin; PMNL, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; pro-HB-EGF, pro-heparin-binding epidermal growth factor–like growth factor; RASI-1, rheumatoid arthritis synovium inflamed-1; SDF-1, stromal cell–derived factor-1.

Pro- and Active MMPs

Matrixins are synthesized as pre–pro-MMPs, and the signal peptide is removed during translation to generate pro-MMPs. In pro-MMPs, the cysteine from the PRCGXPD “cysteine switch” motif coordinates with the catalytic Zn2+ to keep pro-MMP inactive (Nagase et al., 2006). To activate pro-MMPs, the cysteine switch is cleaved and the hemopexin domain is detached, often by other proteinases or MMPs (Nagase et al., 2006). Furin-containing MMPs such as MMP-11, -21, and -28 and MT-MMPs have a furin-like pro-protein convertase recognition sequence at the C terminus of the propeptide and are activated intracellularly by the endopeptidase furin (Pei and Weiss, 1995) (Fig. 2). Following their intracellular activation by furin, MT-MMPs proceed to activate other pro-MMPs on the cell surface (English et al., 2001). For example, activation of pro-MMP-2 occurs on the cell surface, where it first binds via its carboxyl terminus to an integrin or MMP-14–TIMP-2 complex, thus allowing the catalytic site of MMP-2 to be exposed, then is cleaved and activated by MT-MMPs. Due to its cell surface activation, MMP-2 may accumulate pericellularly and induce substantial localized collagenolytic activity (Visse and Nagase, 2003). Stromelysins MMP-3 and -10 are also secreted from cells as pro-MMPs and are activated on the cell surface. MMPs can also be activated by heat, low pH, thiol-modifying agents such as 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate, mercury chloride, N-ethylmaleimide, oxidized glutathione, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and chaotropic agents by interfering with the cysteine-Zn2+ coordination at the cysteine switch. Other specific MMP activators include plasmin for MMP-9, both MMP-3 and hypochlorous acid for MMP-7, and MMP-7 for MMP-1 (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013).

MMP Substrates

MMPs play a major role in tissue remodeling by promoting turnover of ECM proteins. ECM is the extracellular component of mammalian tissue that provides support and anchorage for cells, segregates tissues from one another, regulates cell movement and intercellular communication, and provides a local depot for cellular growth factors. ECM consists mainly of fibers, proteoglycans, and polysaccharides. Fibers are mostly glycoproteins and include collagen, the main extracellular protein, and elastin, which is exceptionally unglycosylated and provides flexibility for the skin, arteries, and lungs. Proteoglycans contain more carbohydrates than proteins, attract water to keep the ECM hydrated, and bind and store growth factors. Syndecan-1 is a proteoglycan and integral transmembrane protein that binds chemotactic cytokines during the inflammatory process. Laminin is found in the basal lamina of epithelia, and fibronectin binds cells to ECM, modulates the cytoskeleton, and facilitates cell movement. ECM contains other proteins and glycoproteins such as vitronectin, aggrecan, entactin, tenascin, and fibrin; polysaccharides such as hyaluronic acid; and proteolytic enzymes that continuously cause turnover of ECM proteins (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013).

ECM and its protein components provide the structural scaffolding for blood vessel support, cell migration, differentiation and signaling, as well as epithelialization and wound repair. Collagen and elastin are essential for vein wall structural integrity and are important MMP substrates. Collagen types I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, and XIV are broken down by MMPs with different efficacies. Other MMP substrates include the ECM proteins fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin, entactin, tenascin, aggrecan, and myelin basic protein (Table 1). Casein is not a physiologic MMP substrate, but is digested by a wide range of proteinases and is, therefore, used to measure MMP activity (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013).

The hemopexin domain confers much of the substrate specificity for MMPs (Patterson et al., 2001; Suenaga et al., 2005) and is essential in the degradation of fibrillar collagen, whereas the catalytic domain is essential in degrading noncollagen substrates (Visse and Nagase, 2003). MMP catalytic activity generally requires Zn2+ and a water molecule flanked by three conserved histidine residues and a conserved glutamate, with a conserved methionine acting as a hydrophobic base to support the structure surrounding the catalytic Zn2+ in the MMP molecule. In the initial transition states of the MMP-substrate interaction, Zn2+ is penta-coordinated with a substrate's carbonyl oxygen atom, one oxygen atom from the MMP glutamate-bound water (H2O), and the three MMP conserved histidines. The Zn2+-bound water then performs a nucleophilic attack on the substrate, resulting in the release of a water molecule and breakdown of the substrate (Fig. 3) (Bode et al., 1999; Pelmenschikov and Siegbahn, 2002; Park et al., 2003; Jacobsen et al., 2010). Other alternative transition states during MMP-substrate interaction have been hypothesized whereby Zn2+ is penta-coordinated with a substrate's carbonyl oxygen atom, two oxygen atoms from the MMP conserved glutamate, and two of the three conserved histidines. One oxygen from glutamate then performs a nucleophilic attack on the substrate, causing substrate degradation (Manzetti et al., 2003). Peptide catalysis also depends on specific subsites or pockets (S) within the MMP molecule that interact with corresponding substituents (P) in the substrates. The MMP S1′ pocket is the most important for substrate specificity and binding, is extremely variable, and may be shallow, intermediate, or deep (Bode et al., 1999; Park et al., 2003; Jacobsen et al., 2010). MMP-1 and -7 have shallow S1′ pockets; MMP-2, -9, and -13 have intermediate S1′ pockets; and MMP-3, -8, and -12 have deep S1′ pockets (Park et al., 2003). S2′ and S3′ are shallower and, therefore, more solvent-exposed than S1′ (Jacobsen et al., 2010). The S3 pocket is also important for substrate specificity, second to S1′ (Nagase et al., 2006).

Degradation of particular substrates is carried out by specific classes of MMPs. Stromelysin-1 and -2 (MMP-3 and -10) do not cleave interstitial collagen but digest several ECM components and participate in pro-MMP activation. MMP-3 has similar substrate specificity but higher proteolytic efficiency than MMP-10. Although stromelysin-3 (MMP-11) does not cleave interstitial collagen, it has very weak activity toward ECM molecules, and is distantly related to MMP-3 and -10 (Pei and Weiss, 1995). Also, certain ECM proteins may require the cooperative effects of several MMPs for complete degradation. For example, collagenases MMP-1, -13, and -18 unwind triple-helical collagen and hydrolyze the peptide bonds of fibrillar collagen types I, II, and III into 3/4 and 1/4 fragments (Chung et al., 2004; Nagase et al., 2006), and the resulting single α-chain gelatins are then further degraded into oligopeptides by gelatinases MMP-2 and -9 (Patterson et al., 2001). Gelatinases have three type II fibronectin repeats in the catalytic domain that bind gelatin, collagen, and laminin (Fig. 2). Although MMP-2 is a gelatinase, it can also function as a collagenase, acting much like MMP-1 but in a weaker manner (Nagase et al., 2006). Thus, MMP-2 degrades collagen in two stages: interstitial collagenase–like degradation followed by gelatinolysis promoted by the fibronectin-like domain (Aimes and Quigley, 1995). Similarly, MMP-9 is both a collagenase and gelatinase. As a collagenase, MMP-9 binds α2 chains of collagen IV with high affinity even when it is inactive (Olson et al., 1998), making the substrate rapidly available.

Tissue Distribution of MMPs

MMPs are produced by different tissues and cells (Table 1). Dermal fibroblasts and leukocytes are major sources of MMPs, especially MMP-2 (Saito et al., 2001), and platelets are important sources of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -14 (Seizer and May, 2013). In general, MMPs are either secreted from cells or anchored to the plasma membrane by heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (Visse and Nagase, 2003). MMPs, including MMP-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -9, -12, -13, and MT1-MMP and MT3-MMP, are expressed in vascular cells and tissues (Chen et al., 2013). In the rat inferior vena cava (IVC), MMP-2 and -9 are localized in different layers of the venous wall, suggesting interaction with ECs, VSM, and ECM (Raffetto et al., 2008). Other studies showed MMP-1, -2, -3, and -7 in ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs); MMP-2 in the adventitia (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007); MMP-9 in ECs, medial VSMC, and adventitial microvessels; and MMP-12 in VSMCs and fibroblasts of human great saphenous vein (Woodside et al., 2003). Changes in MMP expression, distribution, or activity could alter vein wall structure and function, and persistent changes in MMPs could contribute to the pathogenesis of CVD.

Chronic Venous Disease

CVD is a common disease of the lower extremity with significant social and economic implications. According to clinical-etiology-anatomy-pathophysiology classification, CVD has seven clinical stages, C0–C6, with C0 indicating no visible signs of CVD; C1, telangiectasies (spider veins); C2, VVs; C3, edema; C4a, skin pigmentation or eczema; C4b, lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche; C5, healed ulcer; and C6, active ulcer (Fig. 4). The term chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is often used for the advanced stages of CVD, C4–C6 (Eklof et al., 2004).

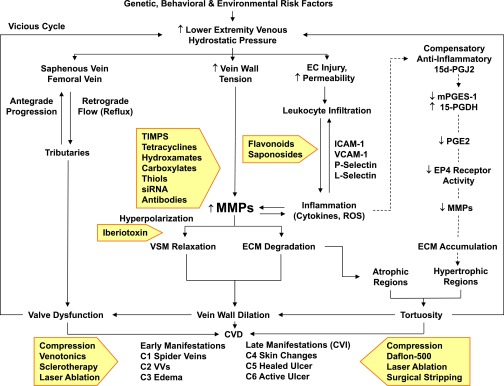

Fig. 4.

Pathophysiology and management of CVD. Certain genetic, behavioral, and environmental risk factors cause an increase in hydrostatic pressure in the lower-extremity saphenous and femoral veins, leading to venous reflux and valve dysfunction. Increased hydrostatic pressure also increases vein wall tension, leading to increases in MMPs, and could also cause EC injury, increased permeability, leukocyte infiltration, and increased levels of adhesion molecules, inflammatory cytokines, and ROS, leading to further increases in MMPs. Increased MMPs may cause VSM hyperpolarization and relaxation as well as ECM degradation, leading to vein wall dilation, valve dysfunction, and progressive increases in venous hydrostatic pressure (vicious cycle). Increased MMPs generally promote ECM degradation, particularly in atrophic regions. Other theories (indicated by dashed arrows) suggest a compensatory anti-inflammatory pathway involving prostaglandins and their receptors that leads to decreased MMPs and thereby ECM accumulation, particularly in hypertrophic regions of VVs. Persistent valve dysfunction and progressive vein wall dilation and tortuosity lead to different stages of CVD and CVI. Current therapies of CVD and CVI (presented in shaded arrows) include physical, pharmacological, and surgical approaches. Inhibitors of the activity or action of MMPs (also presented in shaded arrows) may provide potential tools for the management of CVD/CVI. 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-delta-12,14-prostaglandin J2; mPGES-1, membrane-associated prostaglandin E synthase-1; 15-PGDH, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

VVs are a common venous disorder affecting over 25 million adults in the United States (Beebe-Dimmer et al., 2005). VVs are abnormally distended and twisted superficial lower-extremity veins that often show incompetent valves, venous reflux, and wall dilation (Fig. 1). VV pathology, however, may not be confined to the lower extremities and could affect other tissues in a generalized fashion. In patients with VVs, arm veins also show increased distensibility, suggesting a systemic disease of the vein wall (Zsoter and Cronin, 1966). In addition to their unsightly cosmetic appearance, VVs can cause complications such as thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis, and venous leg ulcers (Eklof et al., 2004).

Risk factors for VVs include age, gender, pregnancy, estrogen therapy, obesity, phlebitis, and prior leg injury. Females may have enhanced estrogen receptor–mediated venous relaxation and more distended veins as compared with men (Raffetto et al., 2010b). Pregnancy-associated increases in uterine size and body weight along with hemodynamic changes could contribute to increased venous pressure in the lower extremities and the development of VVs. Other environmental and behavioral factors such as prolonged standing (Mekky et al., 1969) and a sedentary lifestyle could increase the risk for CVD (Jawien, 2003; Lacroix et al., 2003).

Family history and genetic and hereditary factors could also contribute to the risk for VVs (Lee et al., 2005). Primary lymphedema-distichiasis, a rare syndrome characterized by a mutation in the FOXC2 region of chromosome 16, is associated with VVs at an early age (Ng et al., 2005). VVs have been linked to the D16S520 marker on chromosome 16q24 in nine families, and the localization of the marker near FOXC2 supports linkage between VVs and FOXC2, and provides evidence that CVD could be inherited in an autosomal dominant mode with incomplete penetrance (Serra et al., 2012). Also, patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome often have VVs, supporting heritability of VVs (Delis et al., 2007). Other evidence for a genetic component of VVs include the following: a heterozygous mutation in the Notch3 gene identified in the cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy pedigree with VVs (Saiki et al., 2006); a microarray analysis of 3063 human cDNAs from VVs showing upregulation of 82 genes, particularly those regulating ECM, cytoskeletal proteins, and myofibroblast production (Lee et al., 2005); individuals with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV being prone to vascular pathology and VVs (Badauy et al., 2007); identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region of the MMP-9 gene among Chinese patients with VVs, with a 1562 C-to-T substitution associated with increased MMP-9 promoter activity and plasma levels (Xu et al., 2011); and the reduction of the elasticity of the lower-limb vein wall in children of VV patients (Reagan and Folse, 1971).

Structural and Functional Abnormalities in VVs

Although VVs often appear as engorged, dilated, and twisted veins, structurally, they may have both atrophic and hypertrophic regions (Fig. 4). Atrophic regions have a decrease in ECM and possible increase in inflammatory cells, whereas hypertrophic regions may show abnormal VSMC proliferation and even ECM accumulation (Mannello et al., 2013). Histologically, VVs lack clear boundaries between the intima, media, and adventitia. In VVs, VSMCs are disorganized, jammed into the intima and media, and surrounded by abundant unstructured material. Elastic fibers are thickened and fragmented in the intima and adventitia, and collagen is disorganized, making it difficult to distinguish between the media and adventitia (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007).

VVs and adjacent veins show an imbalance in ECM protein content mainly due to changes in collagen and/or elastin. Measurements of collagen content in VV walls have shown variable results ranging from an increase (Gandhi et al., 1993) to a decrease (Haviarova et al., 1999) or no change (Kockx et al., 1998). Both cultured dermal fibroblasts from patients with CVD and cultured VSMCs from VVs show increased synthesis of type I collagen but decreased synthesis of type III collagen, despite normal gene transcription, suggesting that VV patients may have a systemic abnormality in collagen production and post-translational inhibition of type III collagen synthesis in various tissues. Because type III collagen is important for blood vessel elasticity and distensibility, alterations in collagen synthesis and the ratio of collagen type I to type III may affect vein wall architecture and lead to structural weakness, venous dilation, and VV formation (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007). Decreased elastin content has also been observed in VVs and may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease, as decreased elasticity could lead to vein wall dilation (Venturi et al., 1996). However, some studies showed increased elastic networks in VVs (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007).

VVs also show incompetent valves, but whether valve dysfunction precedes or follows the changes in VV walls is currently debated. One view suggests that valve dysfunction leads to higher venous pressure, which causes vein wall damage and dilation. The vein wall dilation would then further distort the valves, leading to further increases in venous pressure and wall dilation. In support of this view, VVs show valve hypertrophy, increased width of the valvular annulus (Corcos et al., 2000), decreased collagen content, and reduced viscoelasticity (Psaila and Melhuish, 1989), as well as increased monocyte and macrophage infiltration and inflammation in the valvular sinuses compared with distal VV walls (Ono et al., 1998). However, venous dilation and VVs are often seen below competent valves (Naoum et al., 2007). Also, increased collagen and decreased elastin have been demonstrated in both VVs and competent saphenous vein segments in proximity to varicosities, suggesting that ECM imbalance may occur in the vein wall prior to valve insufficiency (Gandhi et al., 1993). These observations led to the suggestion that primary vein wall dilation may cause the valves to become distorted and dysfunctional, leading to venous reflux and higher venous pressure, ultimately causing more venous dilation and VVs (Raffetto and Khalil, 2008b). In support of this view, VVs do not always develop in a descending direction (from thigh, calf, to ankle), and antegrade VV progression (normal direction of venous flow) may be caused by changes in the vein wall that lead to valve dysfunction (Naoum et al., 2007). Regardless of which pathologic event occurs first, both wall dilation and valve dysfunction would lead to vein dysfunction and abnormal blood flow, with blood moving away from the heart during reflux (backflow) that typically lasts longer than 0.5 second in superficial VVs (Raffetto and Khalil, 2008b).

MMP Levels in VVs

Several studies have shown increased MMP levels in VVs. One study showed increased MMP-1, -2, -3, and -7 levels in VVs, with a particular increase in MMP-2 activity (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007). Another study showed increased MMP-1 protein levels in the great saphenous vein, along with increased MMP-1 and -13 in proximal versus distal VV segments, with no change in MMP mRNA levels, suggesting that the increased MMP protein levels may be caused by changes in MMP post-transcriptional modification and protein degradation (Gillespie et al., 2002). MMP levels also vary in different layers of the VV wall. Immunohistochemical studies in VVs showed localization of MMP-1 to fibroblasts, VSMCs, and ECs; MMP-9 to ECs and adventitial microvessels with increased levels in medial VSMCs; and MMP-12 to VSMCs and fibroblasts (Woodside et al., 2003). MMP localization to the adventitia and fibroblasts is consistent with the role of MMPs in ECM degradation. Other studies showed increased MMP-2 levels in all layers and MMP-1, -3, and -7 in the intima and media of VVs (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007).

Despite studies showing increased MMPs in VVs, some studies showed no change or even a decrease in specific MMPs. In one study, active MMP-1 and total MMP-2 decreased, whereas total MMP-1 did not change in VVs (Gomez et al., 2014). Interestingly, measurements of collagen content in VV walls also showed variable results ranging from an increase (Gandhi et al., 1993) to no change (Kockx et al., 1998) to a decrease (Haviarova et al., 1999). The variability in MMP levels may be caused by examining VV segments from different regions, i.e., atrophic versus hypertrophic regions, or veins from patients at different stages of CVD, or failure to distinguish between pro-MMP and active forms of MMP.

MMP activity can be modulated by multiple factors in vivo and ex vivo. Some of these factors include increased venous hydrostatic pressure, inflammation, hypoxia, and oxidative stress. These factors may promote MMP activity in VVs.

Venous Hydrostatic Pressure and MMPs in VVs

Increased venous hydrostatic pressure is one of the factors that could increase MMP levels/activity in VVs (Fig. 4). Increased mechanical stretch or pressure in human tissues is associated with increased expression of specific MMPs in fibroblasts, ECs, and VSMCs (Asanuma et al., 2003). Also, in isolated rat IVC, prolonged increases in vein wall tension are associated with decreased vein contraction and increased levels of MMP-2 and -9 in the intima and MMP-9 in the media. The decreased contraction was prevented in IVC pretreated with MMP inhibitors, supporting a role of MMPs as a link between increased venous pressure/wall tension, decreased vein contraction, and increased venous dilation (Raffetto et al., 2008). Increased venous pressure may increase venous MMP expression by inducing intermediary factors such as inflammation and hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs).

Inflammation and MMPs in VVs

Increased venous pressure may induce EC permeability and injury, leukocyte attachment and infiltration, and inflammation (Schmid-Schonbein et al., 2001). In a rat model of femoral arteriovenous fistula, the resulting pressurized saphenous vein showed increased leukocyte infiltration and inflammation with increased expression of P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Takase et al., 2004). Leukocytes are a major source of MMPs (Saito et al., 2001). Increased adhesion molecules could further facilitate leukocyte adhesion and infiltration, causing further inflammation and increased MMP levels in the vein wall. MMPs in turn cause ECM degradation, vein wall weakening, and wall/valve fibrosis, leading to vein wall dilation, valve dysfunction, further increases in venous pressure, and CVD (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013) (Fig. 4). The pressure/inflammation/MMP pathway may occur mostly in atrophic regions of VVs, as indicated by the increased ECM degradation in these regions.

Studies have shown increased monocyte/macrophage infiltration in the walls and valves of saphenous vein specimens from patients with CVD (Ono et al., 1998; Sayer and Smith, 2004). VVs show increased infiltration of inflammatory cells and expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and ICAM-1 in ECs (Aunapuu and Arend, 2005). Also, the plasma levels of endothelial and leukocyte activation markers including ICAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and L-selectin are increased in patients with VVs, and are associated with increased plasma pro-MMP-9, suggesting polymorphonuclear activation and granule release in response to postural blood stasis in VVs (Jacob et al., 2002).

Pressure-induced leukocyte infiltration and inflammation could increase MMPs by increasing the release of cytokines. Urokinase may be involved in the inflammatory reaction and could upregulate tumor necrosis factor-α expression in damaged vessels. Tumor necrosis factor-α increases MMP-9 promoter activity in plasmids, likely through activator protein-1, nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, or specificity protein-1 (Sato et al., 1993). Likewise, interleukins such as interleukin-17 and -18 induce MMP-9 expression via nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells and activator protein-1 pathways (Reddy et al., 2010).

Cytokines may also augment MMP expression by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS). MMP expression in fibroblasts depends on NADPH oxidase-1 expression (Arbiser et al., 2002). Also, urokinase may regulate MMP-9 expression by increasing ROS generation in fibroblasts (Zubkova et al., 2014). In addition to producing MMPs, leukocytes generate oxidants that can both activate (via oxidation of the prodomain thiol, followed by autolytic cleavage) and inactivate MMPs (via modification of amino acids critical for catalytic activity), providing a mechanism to control bursts of proteolytic activity (Fu et al., 2004).

Hypoxia and MMPs in VVs

Increased venous pressure may augment MMP levels and reduce venous contraction via a pathway involving HIFs (Fig. 5). HIFs are nuclear transcriptional factors that regulate genes involved in oxygen homeostasis. The expression and activity of HIFs may also be regulated by mechanical stretch. For instance, HIF-1α and -2α mRNA and protein levels are increased in rat capillary ECs of skeletal muscle fibers exposed to prolonged stretch (Milkiewicz et al., 2007), and HIF-1α protein increases in response to mechanical stress in the rat ventricular wall (Kim et al., 2002). Also, our laboratory has shown that prolonged increases in rat IVC wall tension are associated with increased HIF-1α and -2α mRNA, increased MMP-2 and -9 mRNA expression, and reduced contraction that is reversed by the HIF inhibitors 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthio]-butadiene (U0126) and echinomycin and enhanced with the HIF stabilizer dimethyloxaloylglycine (Lim et al., 2011) (Fig. 5). The mechanism by which mechanical stretch regulates HIFs may involve phosphoinositide 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Mechanical stretch may stimulate phosphoinositide 3-kinase by activating Ca2+ influx through transient receptor potential ion channels such as TRPV4 (Thodeti et al., 2009). Mechanical stretch may also be transduced by integrins to activate signaling cascades that ultimately cause MAPK activation. MAPK could also be activated via stretch-induced stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinases or GPCRs or generation of ROS in response to biomechanical stress. The role of MAPK is supported by the observation that the increase in HIF mRNA expression and the reduction in IVC contraction associated with prolonged vein wall stretch are reversed in veins treated with MAPK inhibitors (Lim et al., 2011). Additional evidence supporting the role of HIFs as factors linking increased venous pressure and MMP expression in VVs is that HIF-1α and -2α transcription factors and HIF target genes are upregulated in VVs (Lim et al., 2012), and that the expression and activity of MMP-2 and -9 can be regulated by HIF-1α in hemodialysis grafts and arteriovenous fistulas (Misra et al., 2008). In addition to mechanical stretch, low oxygen tension, hormones, cytokines, heat, and low pH may also induce HIF expression and, in turn, increase MMP levels.

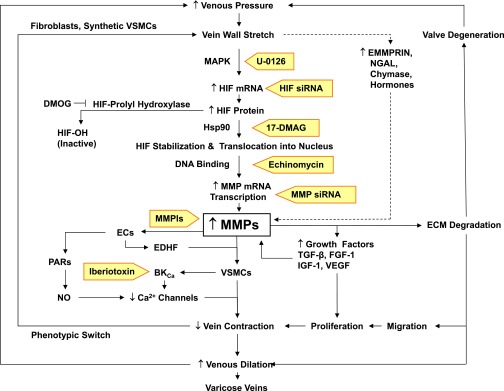

Fig. 5.

Mechanisms linking increased venous pressure to increased MMP expression and VVs. Increased venous pressure causes vein wall stretch, which increases HIF mRNA and protein levels and, in turn, MMP levels. Increased wall stretch may also increase other MMP inducers such as EMMPRIN, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin (NGAL), chymase, and hormones. Increased MMPs may activate PARs in ECs, leading to nitric oxide (NO) production and venous dilation. MMPs may also stimulate ECs to release EDHF, which in turn opens BKCa channels in VSM, leading to hyperpolarization, decreased Ca2+ influx, and decreased vein contraction. Loss of contractile function in VSM could cause a phenotypic switch to synthetic VSMCs. MMPs may also increase the release of growth factors, leading to VSMC proliferation. MMPs also cause ECM degradation, leading to VSMC migration, proliferation, further decreases in vein contraction and increases in venous dilation, and VVs. MMP-induced ECM degradation may also cause valve degeneration, leading to further increases in venous pressure. As indicated in shaded arrows, inhibitors of MMP synthesis [U0126, HIF small interfering RNA (siRNA), 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG), echinomycin, MMP small interfering RNA], activity (MMPIs), or actions (iberiotoxin) may provide new tools for management of VVs. DMOG, dimethyloxaloylglycine (an experimental inhibitor of HIF-prolyl hydroxylase); FGF, fibroblast growth factor; Hsp90, heat shock protein 90; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin.

Other Potential MMP Activators in VVs

Other MMP activators have been identified in veins and may promote MMP activity in VVs. Extracellular MMP inducer (EMMPRIN; CD147, basigin) is a widely expressed membrane protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily that has been implicated in tissue remodeling and various pathologic conditions, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and aneurysm. Interestingly, high-volume mechanical ventilation causes acute lung injury and upregulation of MMP-2, MMP-9, MT1-MMP, and EMMPRIN mRNA (Foda et al., 2001). Also, EMMPRIN, MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and MT2-MMP are overexpressed in dermal structures of venous leg ulcers, which would favor unrestrained MMP activation and ECM turnover (Norgauer et al., 2002).

Prostanoids are bioactive lipids produced by most blood and vascular cells and may play a role in VVs. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) controls vascular tone, inflammation, and vascular wall remodeling through activation of prosatglandin E2 receptor 1-4 (EP1-4) receptor subtypes (Majed and Khalil, 2012). PGE2 stimulation of EP2/EP4 receptors causes MMP activation in human endometriotic epithelial and stromal cells (Lee et al., 2011). PGE2 synthesis may be decreased in VVs due to an increase in anti-inflammatory 15-deoxy-delta-12,14-prostaglandin J2, a decrease in the synthesizing enzyme membrane-associated prostaglandin E synthase-1, and an increase in the degrading enzyme 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, with an overall decrease in both PGE2 and its receptor EP4, leading to decreased MMP-1 and -2 activity and collagen accumulation that may account for the intimal hyperplasia observed in some regions of VVs (Gomez et al., 2014) (Fig. 4).

Other MMP activators include chymase, a chymotrypsin-like serine protease purified from mast cell granules and cardiovascular tissues in mammals, which may be involved in increasing MMP-9 activity and monocyte/macrophage accumulation in the aorta of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (Takai et al., 2014). Also, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone increase the levels and activity of MMP-2 and -9 in uterine and aortic tissues (Yin et al., 2012; Dang et al., 2013). Some MMP modulators could enhance MMP activity by preventing MMP degradation. For instance, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin forms a complex with MMP-9 and thereby protects it from proteolytic degradation and increases its levels (Serra et al., 2014). The list of MMP activators is growing, and whether these activators are increased in VVs needs to be examined.

Mechanisms of MMP Actions in VVs

Although MMPs are generally recognized for their proteolytic effects on ECM proteins, MMPs could also contribute to the pathogenesis of VVs by affecting different components of the vein wall and different cellular and molecular pathways in VSMCs and the endothelium.

MMPs and ECM Abnormalities in VVs

Changes in MMP activity alter the composition of ECM and, in turn, contribute to structural and functional abnormalities in VVs. Although it is generally believed that MMP levels increase in VVs, decreased MMP levels have also been observed (Gomez et al., 2014), and this may partially explain the different pathologies in the atrophic versus hypertrophic regions of VVs. An increase in MMP activity is predicted to degrade and decrease ECM in atrophic regions of VVs (Mannello et al., 2013). On the other hand, a decrease in MMP activity may lead to ECM accumulation in the media of hypertrophic regions of VVs, which could interfere with the contractile function of VSMCs, thus hindering venous contraction and leading to venous dilation and VVs (Badier-Commander et al., 2000) (Fig. 4).

Changes in ECM content in VVs often involve MMP-induced degradation of major ECM proteins such as collagen and elastin. Collagen type III and fibronectin are decreased in cultured VSMCs from VVs, likely due to post-transcriptional degradation by MMP-3 (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2005). Elastin levels are also decreased in VVs, possibly due to increased elastolytic activity of MMPs or other elastases produced by macrophages, monocytes, platelets, and fibroblasts (Venturi et al., 1996). The changes in collagen and elastin content in VVs are dynamic processes that may depend on the stage of CVD. For instance, increased collagen content may compensate for decreased elastin levels at early stages of VVs, whereas collagen levels may decrease at later stages of the disease. This may explain the divergent reports regarding collagen content in VVs, where some studies showed a decrease (Haviarova et al., 1999), whereas other studies showed hardly any change (Venturi et al., 1996; Kockx et al., 1998) or even an increase (Gandhi et al., 1993).

MMPs and VSM Dysfunction in VVs

In addition to changes in ECM, VVs may show alterations in VSMC growth, proliferation, migration, and contractile function (Fig. 5). When compared with smooth muscle cells (SMCs) from normal veins, SMCs from VVs are more dedifferentiated and show increased migration, proliferation, and MMP-2 production, which may contribute to vein wall remodeling and weakening against increased hydrostatic pressure (Xiao et al., 2009). MMP-1 and -9 levels have also been shown to increase human aortic SMC migration (Jin et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2010). MMP-induced ECM proteolysis may modulate cell-matrix adhesion either by removal of sites of adhesion or by exposing a binding site and, in turn, facilitate VSMC migration. MMPs can also facilitate VSMC proliferation by promoting permissive interactions between VSMCs and components of ECM, possibly via integrin-mediated pathways (Morla and Mogford, 2000). MT1-MMP may stimulate the release of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and promote the maturation of osteoblasts (Karsdal et al., 2002). Also, upregulation of MMP-2 increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor a (VEGFa), whereas downregulation of MMP-2 decreases VEGFa expression in human gastric cancer cell line SNU-5 (Mao et al., 2014). MMP-induced release of growth factors may involve cleaving the growth factor–binding proteins or matrix molecules, and may partly explain the VSMC proliferation observed in hypertrophic regions of VVs (Zhang et al., 2004).

Although MMPs stimulate growth factor release, MMPs may be regulated by growth factors (Hollborn et al., 2007). For example, overexpression of VEGFa in SNU-5 cells increases MMP-2 expression, whereas downregulation of VEGFa decreases MMP-2 expression (Mao et al., 2014). Also, platelet-derived growth factor-BB increases MMP-2 expression in rat VSMCs, possibly via Rho-associated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, and p38 MAPK phosphorylation (Cui et al., 2014). Also, in a study on carotid plaques, epidermal growth factor (EGF) upregulated MMP-9 activity and increased MMP-1, -9, and EGF receptor (EGFR) mRNA transcripts in VSMCs (Rao et al., 2014). In contrast, TGF-β1 may downregulate MMPs via a TGF-β1 inhibitory element in the MMP promoter. Interestingly, MMP-2 does not have this element, and TGF-β1 may upregulate MMP-2.

Because proliferating and synthetic VSMCs do not contract, the MMP and growth factor–mediated VSMC proliferation is expected to decrease venous contraction and promote dilation (Fig. 5). MMPs may also affect VSM contraction mechanisms. VSM contraction is triggered by increases in Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space. MMPs do not inhibit phenylephrine-induced aortic contraction in Ca2+-free solution, suggesting that they do not inhibit the Ca2+ release mechanism (Chew et al., 2004). On the other hand, MMP-2 and -9 cause aortic relaxation by inhibiting Ca2+ influx (Chew et al., 2004), and MMP-2 inhibits Ca2+-dependent contraction in rat IVC (Raffetto et al., 2010a). It has been proposed that, during substrate degradation, MMPs may produce Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)–containing peptides, which could bind to αvβ3 integrin receptors and inhibit Ca2+ entry into VSM (Waitkus-Edwards et al., 2002). This is unlikely, as RGD peptides do not affect IVC contraction (Raffetto et al., 2010a). The mechanism by which MMPs inhibit Ca2+ entry could involve direct effects on Ca2+ or K+ channels. In rat IVC, MMP-2–induced relaxation is abolished in high KCl depolarizing solution, which prevents K+ ion from moving out of the cell via K+ channels. Importantly, blockade of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCas) by iberiotoxin inhibited MMP-2–induced IVC relaxation, suggesting that MMP-2 actions may involve hyperpolarization and activation of BKCa, which in turn lead to decreased Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Raffetto et al., 2007) (Fig. 5). The MMP-induced inhibition of venous tissue Ca2+ influx and contraction may lead to venous dilation and VVs.

MMPs and Endothelium-Dependent Relaxation

The endothelium controls vascular tone by releasing relaxing factors, including nitric oxide and prostacyclin, and through hyperpolarization of the underlying VSMCs by endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (Feletou and Vanhoutte, 2006). MMPs may stimulate protease-activated receptors (PARs), which are GPCRs that may play a role in venous dilation in VVs (Fig. 5). PAR-1–4 have been identified in humans, and MMP-1 has been shown to activate PAR-1 (Boire et al., 2005). PAR-1 is expressed in VSMCs (McNamara et al., 1993), ECs, and platelets (Coughlin, 2000), and is coupled to increased nitric oxide production (Garcia et al., 1993), which could contribute to venous dilation and VV formation.

EDHF-mediated relaxation may involve the opening of small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and hyperpolarization of ECs. EC hyperpolarization may spread via myoendothelial gap junctions, causing relaxation of VSMCs. EDHF could also cause hyperpolarization through opening of BKCa in VSM (Feletou and Vanhoutte, 2006). MMP-2 may increase EDHF release and enhance K+ efflux via BKCa, leading to venous tissue hyperpolarization and relaxation (Raffetto et al., 2007). However, MMP-3 upregulation may impair endothelium-dependent vasodilation (Lee et al., 2008), making it important to further examine the effects of MMPs on EDHF.

Management of VVs

The first line of management of VVs includes graduated compression stockings, which help relieve edema and pain and control progression to the more severe forms of CVI with skin changes and ulceration (Fig. 4). Compression stockings could also prevent venous thromboembolism following surgery, although they may not improve deep vein hemodynamics. Pharmacological treatment of VVs using venotonic drugs may improve venous tone, capillary permeability, and leukocyte infiltration. Venotonic drugs include naturally occurring plant extracts and glycosides such as α-benzopyrones (coumarins), γ-benzopyrones (flavonoids), saponosides (escin, horse chestnut seed extract, ruscus extract, Centella asiatica), and plant extracts (blueberry and grape seed, Ginkgo biloba, ergots) (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013). Benzopyrones include escletin, umbelliferone, dicoumarols, diosmin (Daflon-500), quercetin, oxerutin, troxerutin, rutosides, hesperitin, hesperidine, catechin (green tea), flavonoic acid, and venoruton (Raffetto and Khalil, 2008a). Diosmin is a flavonoid and an active ingredient in Daflon-500 that may improve venous tone, microvascular permeability, lymphatic activity, and microcirculatory nutritive flow (Le Devehat et al., 1997). Rutosides enhance endothelial function in patients with CVI (Cesarone et al., 2006). Flavonoids may affect the endothelium and leukocytes and reduce edema and inflammation. Saponosides, such as escin (horse chestnut seed extract), may limit venous wall distensibility and morphologic changes by causing Ca2+-dependent venous contraction (Raffetto and Khalil, 2011). Other compounds tested in advanced CVI include pentoxifylline, functioning through unknown mechanisms, and red vine leaves (AS 195) and PGE1, which may increase microcirculatory blood flow and transcutaneous oxygen tension and alleviate edema (Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013).

Sclerotherapy under duplex ultrasound guidance is another approach to obliterate dilated VVs and improve venous hemodynamics. Concentrated sclerosing agents such as hypertonic saline, sodium morrhuate, and ethanolamine oleate have side effects and are not frequently used. Sodium tetradecyl sulfate (which is a liquid or foam detergent), sodium morrhuate, and polidocanol are Food and Drug Administration–approved sclerosing agents for treatment of VVs (Mann, 2011).

Surgical approaches for treatment of VVs include endovenous ablation with a radiofrequency or infrared laser, typically at wavelengths 810–1320 nm but as high as 1470 and 1550 nm. The high-intensity endoluminal thermal heat causes endothelial protein denaturation and vein occlusion (Proebstle et al., 2002). Laser treatment has relatively good outcome and occlusion rates with only a 2% recanalization rate 4 years after radiofrequency therapy (Merchant et al., 2005) and 3–7% VV recurrence rate 2–3 years after infrared laser therapy (Min et al., 2003). Other approaches include surgical stripping of the saphenous vein with high ligation of the saphenofemoral junction. Large VV clusters that communicate with the incompetent saphenous vein can also be avulsed by “stab phlebectomy.” Transilluminated power phlebectomy is an alternative to open phlebectomy in removing clusters of varicosities, as it uses fewer incisions and less operation time (Aremu et al., 2004).

Although there are some treatment options for VVs, these treatments focus on the symptoms rather than the causes of the venous disorder. The identification of the role of MMPs in the pathogenesis of CVD has prompted the search for inhibitors of MMP expression or activity. MMP inhibitors (MMPIs) can be used to prevent MMPs from binding with their substrates and degrading the ECM, and thereby prevent the development or recurrence of VVs. MMPIs include endogenous inhibitors such as TIMPs and α2-macroglobulin, as well as synthetic Zn2+-dependent and Zn2+-independent inhibitors.

TIMPs and TIMP/MMP Ratio

TIMPs are endogenous, naturally occurring MMPIs that bind MMPs in a 1:1 stoichiometry (Bode et al., 1999; Nagase et al., 2006) (Fig. 6). Four homologous TIMPs, TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4, have been identified. TIMP-1 and -3 are glycoproteins, whereas TIMP-2 and -4 do not contain carbohydrates. TIMPs have poor specificity for a given MMP, and each TIMP can inhibit multiple MMPs with different efficacy. For example, whereas TIMP-2 and -3 can inhibit MT1-MMP and MT2-MMP, TIMP-1 is a poor inhibitor of MT1-MMP, MT3-MMP, MT5-MMP, and MMP-19 (Baker et al., 2002). Also, the binding of TIMP-1 and -2 to MMP-10 (stromelysin-2) is 10-fold weaker than their binding to MMP-3 (stromelysin-1) (Batra et al., 2012). TIMP-1 has a Thr2 residue that interacts with the specific P1′ substituent of MMP-3, and substitutions at Thr2 affect the stability of the TIMP-MMP complex and the specificity for different MMPs. For example, a substitution of alanine for Thr2 causes a 17-fold decrease in binding of TIMP-1 to MMP-1 relative to MMP-3 (Meng et al., 1999).

Fig. 6.

TIMP-MMP interaction. TIMP-1 and MMP-3 are used as prototypes. (A) TIMP is an ∼190 amino acid (aa) protein, with an N-terminal domain (loops L1, L2, and L3) and C-terminal domain (loops L4, L5, and L6), which fold independently as a result of six disulfide bonds between 12 specific Cys residues. The N-terminal Cys1-Thr-Cys-Val4 and Glu67-Ser-Val-Cys70 are connected via a disulfide bond between Cys1 and Cys70 and are essential for MMP inhibition, as they enter the MMP active site and bidentately chelate the MMP Zn2+. The carbonyl oxygen and α-amino nitrogen in the TIMP Cys1 coordinate with the MMP Zn2+, which is localized in the MMP molecule via the three histidines in the HEXXHXXGXXH motif. The TIMP α-amino group then expels Zn2+-bound H2O by binding the MMP H2O binding site and forming an H bond with carboxylate oxygen from conserved MMP Glu202 (E in the HEXXHXXGXXH sequence). (B) TIMP Thr2 side chains then enter the MMP S1′ pocket in a manner similar to that of a substrate P1′substituent, largely determining the affinity to MMP. The Thr2 –OH group could also interact with Glu202, further contributing to expelling Zn2+-bound H2O and preventing substrate degradation. Additionally, the TIMP Cys3, Val4, and Pro5 interact with MMP S2′, S3′, and S4′ pockets in a P2′-, P3′-, and P4′-like manner, further preventing substrate binding or degradation. The amino acids involved in Zn2+- and pocket-binding vary in different TIMPs.

TIMPs localize to specific regions within the veins. In one study, TIMP-2 and -3 localized predominantly to VSM of the tunica media, and although TIMP-2 was not identifiable in the connective tissue of the endothelium or tunica media, TIMP-3 was identified in the elastic tissue of the vein wall (Aravind et al., 2010). Other studies showed TIMP-1, -2, and -3 in the intima and TIMP-1 and -2 in the media of control veins, as compared with TIMP-1 and -3 in the intima and TIMP-1, -2, and -3 in the media of VVs (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007).

A change in either TIMP or MMP levels could alter the TIMP/MMP ratio and cause a net change in specific MMP activity. In one study, MMP-1 and -7 and TIMP-1, -2, and -3 levels were only slightly modified, whereas MMP-2 and -3 levels were increased in skin from patients with VVs compared with control subjects, thereby decreasing the TIMP/MMP ratio, increasing MMP-2 and -3 activity, and promoting ECM degradation (Sansilvestri-Morel et al., 2007), particularly in atrophic regions of VVs. Other studies have shown an increase in TIMP/MMP ratios and a net decrease in certain MMP activities in specific regions of VVs. For instance, one study showed a 3-fold increase in the TIMP-1/MMP-2 ratio in pulverized VVs and suggested that the resulting decrease in MMP-2 proteolytic activity could be the cause of the accumulation of ECM often observed in hypertrophic regions of VVs (Badier-Commander et al., 2001). These observations highlight the importance of further examining the levels of TIMPs as related to specific MMPs in different regions of VVs.

α2-Macroglobulin, Monoclonal Antibodies, and Other Endogenous MMP Inhibitors

Human α2-macroglobulin is a glycoprotein consisting of four identical subunits and is found in blood and tissue fluids. α2-Macroglobulin is a general proteinase inhibitor that inhibits most endopeptidases, including MMPs, by entrapping the peptidase within the macroglobulin. The complex is then rapidly cleared by endocytosis via low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (Strickland et al., 1990). Monoclonal antibodies are MMPIs that have high specificity and affinity for MMPs and can detect MMPs in the body fluids and tissues of patients (Raffetto and Khalil, 2008a). Monoclonal antibodies REGA-3G12 and REGA-2D9 are specific to MMP-9 and do not cross-react with MMP-2. MMP inhibition by REGA-3G12 does not appear to involve the MMP Zn2+-binding group or the fibronectin region, but may involve the catalytic domain. REGA-1G8 is not as specific and cross-reacts with serum albumin.

Other proteinase inhibitors inhibit certain MMPs. For example, a secreted form of β-amyloid precursor protein or a C-terminal fragment of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer protein can inhibit MMP-2. Reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs is a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol–anchored glycoprotein expressed in many cells, including VSMCs, and when it is expressed in transfected human fibrosarcoma–derived cell line HT1080, it causes inhibition of MMP-2, -9, and -14 activity (Oh et al., 2001). Also, tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 is a serine proteinase inhibitor that inhibits MMP-1 and -2 (Herman et al., 2001).

Synthetic MMP Inhibitors

Synthetic MMPIs have been developed as potential therapies for degenerative and vascular diseases (Table 2). For more details and for the original references regarding the different categories of MMPIs, their MMP specificity, IC50 or Ki, and their use in experimental trials, the reader is referred to previous reviews (Benjamin and Khalil, 2012; Kucukguven and Khalil, 2013).

TABLE 2.

MMP inhibitors, their specificity to MMPs (Ki or IC50 < 1 nM to 10 μM), and their experimental trials

For details and original references, see Benjamin and Khalil (2012) and Kucukguven and Khalil (2013).

| MMP Specificity, IC50 or Ki | Experimental Trials | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMPI Main Categories, Number, Specific Chemistry, Other Names | <1 nM | 1–10 nM | 11–100 nM | 0.1–1 µM | 1–10 µM | ||

| 1 | ZBGs, hydroxamic acids | ||||||

| Succinyl hydroxamate batimastat (BB-94) | MMP-1, 2, 8, 9 | MMP-3 | |||||

| Marimastat (BB-2516) | MMP-1, 2, 9, 14 | MMP-7 | Glioblastoma, lung, breast, ovarian, prostate cancer | ||||

| Ilomastat (GM6001, galardin) | MMP-1, 2, 8, 9, 26 | MMP-7, 12 | MMP-3, 14 | ||||

| 2 | Sulfonamide hydroxamate, AG3340, Prinomastat | MMP-2, 3, 9, 13, 14 | MMP-1 | MMP-7 | Neovascularization, lung cancer, uveal melanoma, gliomas, prostate cancer | ||

| 3 | Succinyl hydroxamate | MMP-1 | |||||

| 4 | RS-104966 | MMP-13 | MMP-1 | ||||

| 7 | Sulfonamide hydroxamate | MMP-2 | MMP-8, 9, 14 | MMP-1, 3 | MMP-7 | Decrease tumor invasion | |

| 8 | Sulfonamide hydroxamate | MMP-3 | MMP-2 | MMP-9 | Chronic nonhealing wounds | ||

| 10 | MMP-2, 3 | MMP-1 | |||||

| 12 | MMP-3 | ||||||

| 5 | Carboxylic acids | MMP-13 | MMP-3, 8 | MMP-2 | MMP-7, 9, 14 | Osteoarthritis | |

| 6 | MMP-11 | MMP-3, 12 | MMP-1, 9, 14 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||

| 9 | Sulfonylhydrazides | MMP-2, 9 | MMP-1 | MMP-7 | MMP-3 | ||

| 16 | Thiol- and cyclic mercaptosulfides | MMP-9 | MMP-2 | MMP-1, 7, 14 | MMP-3 | ||

| 19 | Aminomethyl benzimidazoles | MMP-11 | MMP-2, 9, 13 | ||||

| 17 | Phosphorous-based | ||||||

| Sulfonamide phosphonate | MMP-8 | MMP-2 | MMP-3 | ||||

| 18 | Sulfonamide phosphonate | MMP-8 | MMP-2, 9, 13, 14 | MMP-1, 3 | MMP-7 | Liver disease, multiple sclerosis, breast cancer | |

| 20 | Carbamoyl phosphonate | MMP-2 | Melanoma | ||||

| 21 | Carbamoyl phosphonate | MMP-2 | Melanoma, prostate cancer | ||||

| 22 | Nitrogen-based | ||||||

| Oxazoline | MMP-11 | ||||||

| 23 | Dionethiones and pyrimidine-2,4,6 triones Ro-28-2653 | MMP-2, 14 | MMP-8, 9 | MMP-3 | Antiangiogenic and anti-invasive in tumor models | ||

| 24 | Dionethiones and pyrimidine-2,4,6 triones | MMP-13 | MMP-2, 9, 12 | Osteoarthritis | |||

| 25 | Heterocyclic bidentate chelators | ||||||

| Terphenyl backbone, AM-6 | MMP-3 | ||||||

| 26 | Biphenyl backbone, 1,2-HOPO-2 | MMP-8, 12 | MMP-2, 3 | MMP-13 | Heart ischemia and reperfusion | ||

| 27 | Diphenyl ether backbone | MMP-2, 9, 13 | MMP-3 | MMP-1 | Brain edema following ischemia–reperfusion | ||

| 28 | Biphenyl backbone, pyrone-based | MMP-3, 9, 12 | MMP-8 | MMP-2, 13 | |||

| 29 | Biphenyl backbone, hydroxypyridinone derivative | MMP-8, 12 | |||||

| 30 | Biphenyl backbone, AM-2 | MMP-8, 12 | MMP-3 | MMP-2 | |||

| 31 | Biphenyl backbone | MMP-2, 8, 12, 13 | |||||

| 34 | Non-ZBGs | MMP-13 | Osteoarthritis | ||||

| 35 | MMP-12 | MMP-2, 8, 13 | MMP-3, 9 | ||||

| 36 | MMP-2, 8, 13 | ||||||

| 37 | MMP-13 | Osteoarthritis | |||||

| 38 | Pyrimidine dicarboxamide | MMP-13 | |||||

| 39 | Pyrimidine dicarboxamide | MMP-13 | |||||

| 40 | Mechanism-Based | ||||||

| Diphenyl ether backbone, SB-3CT | MMP-2 | MMP-9, 14 | MMP-3 | Inhibits liver metastasis in T-cell lymphoma and bone metastasis in prostate cancer | |||

| 42 | Diphenyl ether backbone, thiol-containing | MMP-2, 9 | MMP-14 | MMP-3 | |||

| 43 | Diphenyl ether backbone | MMP-2 | MMP-14 | MMP-9 | MMP-3 | ||

| 45 | Diphenyl ether backbone | MMP-9 | MMP-2 | MMP-3, 14 | |||

AG3340, (S)-N-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-4-((4-(pyridin-4-yloxy)phenyl)sulfonyl)thiomorpholine-3-carboxamide; AM-2, 3-Hydroxy-6-methyl-pyran-4(1H)–one-2-carboxy-N-(4-phenylbenzylamide); AM-6, 3-Hydroxy-6-methyl-pyran-4(1H)–one-2-carboxy-N-(4,4-biphenylbenzylamide); 1,2-HOPO-2, 1-Hydroxy-2(1H)-pyridinone; Ro-28-2653, 5-(4-Biphenylyl)-5-[4-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-piperazinyl]-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-pyrimidinetrione; RS-104966, 4-[(4-Phenoxyphenyl)sulfonylmethyl]-N-hydroxyoxane-4-carboxamide

MMP inhibition can be achieved via a Zn2+-binding group (e.g., hydroxamic acid, carboxylic acid, sulfhydryl group) or noncovalent interaction with groups on the MMP backbone such as the S1′, S2′, S3′, and S4′ pockets to which the MMPI side chains bind in a fashion similar to that of the substrate P1′, P2′, P3′, and P4′ substituents. The efficacy and specificity of inhibition are determined by which pockets are blocked for a given MMP (Hu et al., 2007).

Zn2+-binding globulins (ZBGs) displace the Zn2+-bound water molecule on an MMP and inactivate the enzyme. A ZBG is also an anchor that keeps the MMPI in the MMP active site and allows the backbone of the MMPI to enter the MMP substrate-binding pockets (Jacobsen et al., 2010). ZBGs have the potential to be used clinically if their potency and selectivity against specific MMPs are enhanced and their targets are better-defined using site-specific delivery (Li et al., 2005). ZBGs such as hydroxamic acids include succinyl (Hu et al., 2007), sulfonamide (Scozzafava and Supuran, 2000), and phosphinamide hydroxamates (Pochetti et al., 2006). Batimastat (BB-94), marimastat (BB-2516), and ilomastat (GM6001) are examples of broad-spectrum succinyl hydroxamates (Hu et al., 2007) with a collagen-mimicking structure that inhibits MMPs by bidentate chelation of the active site Zn2+ (Wojtowicz-Praga et al., 1997). Other ZBGs include carboxylic acids, sulfonylhydrazides, thiols (Jacobsen et al., 2010), aminomethyl benzimidazole-containing ZBGs, phosphorous- and nitrogen-based ZBGs (Skiles et al., 2001; Jacobsen et al., 2010), and heterocyclic bidentate chelators (Puerta et al., 2004). Tetracyclines (Hu et al., 2007) and mechanism-based inhibitors also depend on Zn2+ ion for inhibition. 2-[[(4-phenoxyphenyl)sulfonyl]methyl]-thiirane (SB-3CT) (compound 40) is a mechanism-based MMPI that coordinates with MMP Zn2+, thus allowing conserved MMP Glu202 to perform a nucleophilic attack and form a covalent bond with the compound (Jacobsen et al., 2010). The covalent bond impedes MMPI dissociation as compared with the traditional chelating competitive MMPIs, and therefore reduces the rate of catalytic turnover and decreases the amount of MMPI needed to saturate the MMP active site (Bernardo et al., 2002). SB-3CT and its successors have shown clinical promise, and more selective MMPIs may be developed through covalent modifications in the active site (Jacobsen et al., 2010).

Some MMPIs, such as compound 37, do not have ZBGs and do not bind to the highly conserved Zn2+-binding group (Johnson et al., 2007). Also, some MMPIs are specific to certain MMPs. Small interfering RNA inhibits the transcriptional product of MMP-2 (Chetty et al., 2006). Glycosaminoglycan sulodexide decreases MMP-9 secretion from white blood cells without MMP prodomain displacement (Mannello et al., 2013), and may specifically inhibit proteases with cysteine residues such as MMP-2 and -9 (Serra et al., 2014). Statins such as atorvastatin inhibit MMP-1, -2, and -9 expression in human retinal pigment epithelial cells (Dorecka et al., 2014) and MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 secretion from rabbit macrophages and cultured rabbit aortic and human saphenous vein VSMCs (Luan et al., 2003). Also, in a rat model of heart failure, pravastatin suppressed an increase in myocardial MMP-2 and -9 activity (Ichihara et al., 2006). Deep sea water components such as Mg2+, Cu2+, and Mn2+ may inhibit proliferation and migration of cultured rat aortic VSMCs by inhibiting not only extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and MAPK kinase phosphorylation but also MMP-2 activity (Li et al., 2014), a mechanism that may involve interference with Zn2+ binding at the MMP catalytic active site. Despite the marked advances in the design of MMPIs, therapeutic inhibition of MMPs remains a challenge, and the tetracycline antibiotic doxycycline is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved MMPI (Chen et al., 2013). Another limitation of MMPIs is that they may cause musculoskeletal side effects, including joint stiffness, inflammation, pain, and tendonitis (Renkiewicz et al., 2003).

Venous versus Arterial MMPs

Although this review focused on venous MMPs, this should not minimize the role of MMPs in other parts of the circulation. MMPs are expressed in the arterial system, and could have significant effects on the arterial structure and function as those discussed in the veins. For example, MMP-2 and -9 cause inhibition of Ca2+ entry–dependent mechanisms of contraction not only in rat IVC (Raffetto et al., 2010a), but also in rat aorta (Chew et al., 2004). However, veins differ from arteries in their structure and function, and the effects of MMPs on the veins should not always be generalized to the arteries. For instance, veins have few layers of VSMCs compared with several layers in the arteries. Also, venous and arterial VSMCs originate from distinct embryonic locations and are exposed to different pressures and hemodynamic conditions in the circulation (Deng et al., 2006). Interestingly, cell culture studies have shown that, although cell migration and MMP-2 and -9 levels could be similar in saphenous vein VSMCs and internal mammary artery VSMC, venous VSMCs exhibit more proliferation and invasion as compared with arterial VSMCs (Turner et al., 2007). Other studies have shown that MMP-2 expression is higher in cultured VSMCs from human saphenous veins than in those from human coronary artery. In contrast, MMP-3, -10, -20, and -26 expression is higher in coronary artery VSMCs than saphenous vein VSMCs (Deng et al., 2006). As with MMPs, TIMPs may show different expression levels in veins versus arteries. For instance, the expression levels of TIMP-1, -2, and -3 are higher in cultured VSMCs from human saphenous veins than in human coronary artery VSMCs (Deng et al., 2006). These observations make it important to further study the differences in the expression and activity of MMPs and TIMPs in veins versus arteries and in venous versus arterial disease.

Perspectives

MMPs and TIMPs could be important biomarkers for the progression of CVD and potential targets for the management of VVs. One challenge to understanding the pathogenesis of VVs is that studies often focus on measuring certain MMPs or TIMPs, and it is important not to generalize the findings to other MMPs and TIMPs. Because vein remodeling is a dynamic process, an increase in one MMP in a certain region may be paralleled by a decrease of other MMPs in other regions. Also, because of the differences in the proteolytic activities of different MMPs toward different substrates, the activities of MMPs may vary during the course of CVD. This makes it important to examine different MMPs and TIMPs in various regions of VVs and at different stages of the disease. Another challenge is that TIMPs and other available MMPIs have poor selectivity and many biologic actions, and therefore cause side effects (Hu et al., 2007). New synthetic MMPIs are being developed, and their effectiveness in treatment of VVs needs to be examined. It is also important to develop specific approaches to modify the expression or activity of MMPs locally in the vicinity of VVs while minimizing their systemic effects.

Abbreviations

- BKCa

large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- CVD

chronic venous disease

- CVI

chronic venous insufficiency

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- EMMPRIN

extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer

- EP1

prostaglandin E2 receptor 1

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MMPI

MMP inhibitor

- MT-MMP

membrane-type MMP

- PAR

protease-activated receptor

- PGE

prostaglandin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SB-3CT

2-[[(4-phenoxyphenyl)sulfonyl]methyl]-thiirane

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of MMP

- U0126

1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthio]-butadiene

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VSM

vascular smooth muscle

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- VV

varicose vein

- ZBG

Zn2+-binding globulin

- Zn2+

zinc

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: MacColl, Khalil.

Performed data analysis: MacColl.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MacColl, Khalil.

Footnotes