Abstract

Anemia is an important public health and clinical problem. Observational studies have linked iron deficiency and anemia in children with many poor outcomes, including impaired cognitive development. In this study, we summarize the evidence for the effect of daily iron supplementation on cognitive performance in primary-school-aged children. We searched electronic databases (including MEDLINE and Wangfang database) and other sources (August 2015) for randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials involving daily iron supplementation on cognitive performance in children aged 5-12 years. We combined the data using random effects meta-analysis. We identified 3219 studies; of these, we evaluated 5 full-text papers including 1825 children. Iron supplementation cannot improve global cognitive scores (Mean difference 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] -2.69 to 4.79, P<0.01). Our analysis suggests that iron supplementation improves global cognitive c outcomes among primary-school-aged children is still unclear.

Keywords: Iron supplementation, cognitive performance, meta-analysis

Introduction

An estimated 25% of school-aged children worldwide are anemic [1]. Iron deficiency is associated with inadequate dietary iron and, in developing settings, hookworm and schistosomiasis [2]. In developed settings, anemia is prevalent among disadvantaged populations, including newly arrived refugees, indigenous people [3].

In observational studies, iron deficiency has been associated with impaired cognitive [4,5]. a causal relation between iron deficiency and cognitive impairment has not been confirmed [6]. The effect of longer-term treatment remains unclear. There is an urgent need for further large randomised controlled trials with long-term follow-up.

Optimizing cognitive in primary-school-aged children could have life-long benefits. We performed this meta analysis of the effects of daily iron supplementation, a commonly used strategy to combat anemia in primary-school-aged children. To further confirm that whether daily iron supplementation can improve cognitive impairment.

Methods

Information sources

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE and wanfang database. We reviewed the references of the identified articles and of previous systematic reviews. There was no language restriction applied. We performed the searches on July 4, 2015.

Inclusion criteria

We included randomized controlled trials that included primary-school-aged children (5-12 yr) who were randomly assigned to daily (≥ 5 d/wk) oral iron supplementation or control. We included studies that did not specifically recruit participants from this age range if the mean or median age of participants was between 5 and 12 years. We excluded studies that included only children with a known developmental disability or a condition that substantially altered iron metabolism, including severe anemia. We included trials involving participants from all countries and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Outcomes

We included the following primary outcomes: cognitive performance (as measured by study authors).

Data extraction

Two authors independently assessed the remaining full-text studies against the inclusion criteria; Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed for outcomes for which at least 2 studies provided data. We determined the mean difference (MD) for the difference between outcome means or the change from baseline for continuous data measured on the same scale.

We quantified heterogeneity using I2. We considered substantial heterogeneity to exist if I2 was above 50%. We created forest plots to present the effect size and relative weights for each study and the overall calculated effect size. Random-effects meta-analysis was used with calculation of I2.

Result

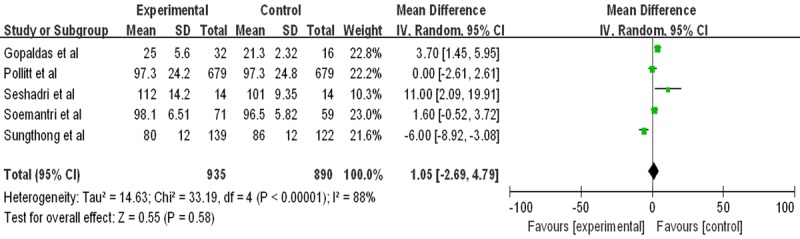

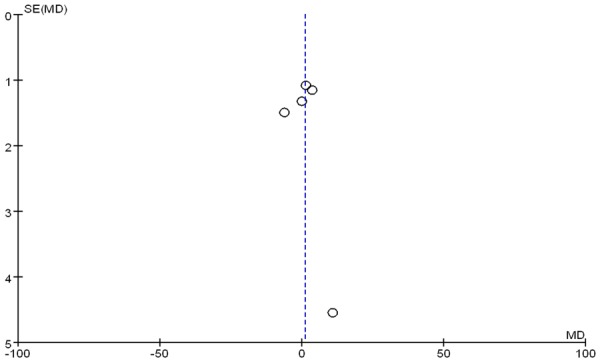

We combined the data using random effects meta-analysis. We identified 3219 studies; of these, we evaluated 5 full-text papers including 1825 children. Iron supplementation cannot improve global cognitive scores (Mean difference 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] -2.69 to 4.79, P<0.01). As showed in Figure 1. No publication bias is found in this meta analysis (Figure 2). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Forest plots for global cognitive performance and cognitive performance by anemia status. *Inverse variance, random effects.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the risk of bias among the included studies.

Table 1.

Studies included in this meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Age at recruitment yr | Baseline | Intervention | Control | No. randomized | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopaldas et al [12] | India | 8-15 | Iron status unknown. subgroups: anemic, nonanemic | Frrous sulfate (30 mg or 40 mg) | Placebo | Total: 480; iron: 239; placebo: 241 | 3 month |

| Pollitt et al [13] | Thailand | 9-11 | Subgroups: anemic, not anemic | Frrous sulfate (50 mg or 100 mg)+albendazole | Placebo+albendazole | Total: 1358; iron: 679; placebo: 679 | 16 week |

| Seshadri et al [14] | India | 5-8 | Anemia and iron status unknow | Unkown (20 mg element iron)+folic acid | Control | Total: 97; iron: 63; placebo: 34 | 60 d |

| Soemantri et al [15] | Indonesia | 8.1-11.6 | Subgroups: anemic, not anemic, iron deficient, not iron deficient, iron deficient anemia, iron deficient not anemic, nonanemic noniron deficient | Ferrous sulfate (10 mg/kg/d) | Placebo | Total: 130; iron: 71; placebo: 59 | 3 month |

| Sungthong et al [16] | Thailand | 6-13 | Anemia and iron status unknown | Ferrous sulfate (300 mg)+albendazole | Placebo+albendazole | Total: 263; iron: 140; placebo: 123 | 16 week |

Discussion

Daily supplementation provides the highest dose of iron of any nonparenteral approach and is a commonly recommended clinical and public health strategy for the prevention and treatment of anemia [7]. Our data are chiefly extrapolatable to iron supplementation interventions; alternative approaches to improving iron stores such as food fortification are under evaluation by other systematic reviews [8].

In this review, we found evidence that iron supplementation on cognitive performance among primary-school-aged children is still not sure, including on IQ among children with anemia. Previous systematic reviews have evaluated the efficacy of iron delivered by multiple approaches. A Cochrane review of intermittent iron supplementation in children found insufficient studies reporting cognitive outcomes or adverse effects [9]. Two previous reviews have evaluated the effects of iron on cognitive outcomes among primary-school-aged children. Sachdev and colleagues [10] reported improvements in overall cognitive performance (SMD 0.30) and IQ (SMD 0.41) among children who received parenteral or enteral iron (including fortification). Falkingham and colleagues [11] found no improvement in overall IQ from iron supplementation, but they reported improvements in IQ among participants with anemia (MD 2.5) and improvements in attention and concentration among adults and children older than 6 years of age.

Limitations

Our review is limited by significant heterogeneity, which we addressed by use of random effects meta-analysis and predefined subgroup analyses. This heterogeneity appears to be mainly because of differences in baseline anemia status. Unfortunately, several important outcomes (particularly physical performance and growth) were reported by relatively few studies. Further randomized trials evaluating the nonhematologic effects of iron, especially outcomes such as cognitive performance, growth and safety, are needed.

Conclusion

In this review, our analysis suggests that iron supplementation improves global cognitive c outcomes among primary-school-aged children is still unclear.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltzfus RJ, Chwaya HM, Tielsch JM, Schulze KJ, Albonico M, Savioli L. Epidemiology of iron deficiency anemia in Zanzibari schoolchildren: the importance of hookworms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:153–159. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofides A, Schauer C, Zlotkin SH. Iron deficiency and anemia prevalence and associated etiologic risk factors in First Nations and Inuit communities in Northern Ontario and Nunavut. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:304–307. doi: 10.1007/BF03405171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong KS, Park H, Ha E, Hong YC, Ha M, Park H, Kim BN, Lee SJ, Lee KY, Kim JH, Kim Y. Evidence that cognitive deficit in children is associated not only with iron deficiency, but also with blood lead concentration: a preliminary study. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;29:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang B, Zhan S, Gong T, Lee L. Iron therapy for improving psychomotor development and cognitive function in children under the age of three with iron deficiency anaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD001444. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001444.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.More S, Shivkumar VB, Gangane N, Shende S. Effects of iron deficiency on cognitive function in school going adolescent females in rural area of central India. Anemia. 2013;2013:819136. doi: 10.1155/2013/819136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs BA. Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood. 2013;121:2607–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-453522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britto JC, Cancado R, Guerra-Shinohara EM. Concentrations of blood folate in Brazilian studies prior to and after fortification of wheat and cornmeal (maize flour) with folic acid: a review. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2014;36:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De-Regil LM, Jefferds ME, Sylvetsky AC, Dowswell T. Intermittent iron supplementation for improving nutrition and development in children under 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD009085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009085.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachdev H, Gera T, Nestel P. Effect of iron supplementation on mental and motor development in children: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:117–132. doi: 10.1079/phn2004677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkingham M, Abdelhamid A, Curtis P, Fairweather-Tait S, Dye L, Hooper L. The effects of oral iron supplementation on cognition in older children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2010;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seshadri S, Gopaldas T. Impact of iron supplementation on cognitive functions in preschool and school-aged children: the Indian experience. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:675–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.3.675. discussion 685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hathirat P, Valyasevi A, Kotchabhakdi NJ, Rojroongwasinkul N, Pollitt E. Effects of an iron supplementation trial on the Fe status of Thai schoolchildren. Br J Nutr. 1992;68:245–252. doi: 10.1079/bjn19920081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seshadri S, Hirode K, Naik P, Malhotra S. Behavioural responses of young anaemic Indian children to iron-folic acid supplements. Br J Nutr. 1982;48:233–240. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soemantri AG. Preliminary findings on iron supplementation and learning achievement of rural Indonesian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:698–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.3.689. discussion 701-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sungthong R, Mo-Suwan L, Chongsuvivatwong V, Geater AF. Once weekly is superior to daily iron supplementation on height gain but not on hematological improvement among schoolchildren in Thailand. J Nutr. 2002;132:418–422. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]