Abstract

Activity of the renin-angiotensin Aldosterone system is increased in patients with heart failure (HF). The Angiotensinogen gene and specifically M235T polymorphism has been linked to susceptibility to hypertension, coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Its role in heart failure is not yet sufficiently demonstrated. The aim of the present study was to assess the association between rs699 (M235T) polymorphism and heart failure in terms of diagnosis and prognosis. We included all patients over 20 years old consulting in the Emergency Department for acute dyspnea. According to the results of the B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP level), patients were divided into two groups: HF and non-HF group. DNA study was performed for all subjects and their genotypes were identified as TT, CT or CC. Mortality was followed for one year. We included 234 patients. We found the diagnosis of HF in 73 patients out of 160 (45%). Our results showed that the frequency of the T allele was higher in HF group patients than in non-HF group (69% vs. 33%, P<0.01). Patients carrying the TT and CT genotypes had a higher proportion of HF than those carrying the CC genotype (respectively 53% and 31% vs. 15%, P<0.01). According to multivariate analysis, TT genotype presented the highest risk of HF (OR=4.9 95% CI: 2.12-9.1) and the highest risk of death (OR=6.45 95% CI: 3.6-16.4) compared to the other two genotypes. The current study suggests that M235T polymorphism might be associated with increased risk of both HF and death.

Keywords: Angiotensinogen, polymorphism, M235T, heart failure, mortality

Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) a major health problem associated with high morbidity and mortality, it’s an ever increasing problem worldwide [1]. Heart failure may result from Coronary heart disease and hypertension what are the major causes of HF. Other underlying conditions include idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC), valvular and congenital heart diseases [2]. Although the exact molecular mechanisms of HF are still under intensive investigation, genetic polymorphisms of major neurohormonal systems involved in the pathophysiology of HF have been discussed [3].

The activity of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is often increased in patients with cardiovascular disease [4]. The RAS is a key element in pressure/volume homeostasis, and plays an important role in the regulation of blood pressure and in cardiac function [5,6]. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the component of RAS that is released by the liver and is cleaved by Renin. To date, M235T polymorphism has been linked to susceptibility to hypertension, coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation [7-9]. It’s role as a marker of HF diagnosis or prognosis is not well recognized.

Results of available studies remain controversial and even the related meta-analyzes published studies focused on small sample sizes and lack of significant reliable data on some ethnicities especially African and North African [10].

In the present study, we investigated the association between M235T polymorphism and acute heart failure in North African patients consulting for dyspnea and the impact of this polymorphism on the prognosis of HF.

Methods

Subjects and study design: This is a prospective descriptive study carried out in the emergency department Fattouma Bourguiba university hospital. We included all patients aged over 20 years consulting for dyspnea. We excluded all patients with cardio-respiratory arrest, coma or circulatory shock. At the time of study entry, family history, physical examination findings, medical therapy, and results of prior cardiac testing were collected. Detailed information for all available electrocardiograms was also recorded. Patients were divided into two groups according to the Nt pro-BNP rate: Group HF with NT pro-BNP higher or equal to 1600 pg/mL. Non HF group with pro NT PRO-BNP lower than 400 pg/mL. For intermediate values, patients were classified in the HF group or non HF after being evaluated by two independent reviewers (one emergency physician and one cardiologist) who established the diagnosis of LVD on the basis of clinical data, NT pro-BNP levels and echocardiography findings. 4 ml of blood in an EDTA tube for DNA extraction, and 4 ml of blood in a Heparin tube for the biochemical tests were collected from each patient.

Biochemical measurements

Serum total cholesterol, HDL-C and triglycerides were measured using enzymatic methods on Beckman auto analyzer (Randox, Antrim, UK). LDL-C cholesterol was calculated using Friedewald’s formula [11]. NT-proBNP was measured by the electrochemiluminescence assay (Elecsys 2010, Roche Diagnostics, Germany).

Biochemical serum parameters (creatinin, uric acid, glycemia) were determined on Cobas 6000™ (Roche Diagnostics).

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes using the standard salt precipitation method (Miller and al., 1988). Genotyping for the AGT M235T was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). The primers used were 5’-GATGCGCACAAGGTCCTGTC-3’ (Forward) and 5’-CAGGGTGCTGTCCACACTGG ACCCC-3’ (reverse). The PCR products were digested with 3 U of Tth111I (Fermentas), and the fragments were separated on a 3% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized with UV light. To assess genotyping reliability, we perform double sampling RFLP-PCR in more than 20% of the samples and found no differences.

Outcomes

The main outcomes were the diagnosis of HF and mortality rate after one year of hospitalization. Secondary outcomes for this study included all-cause of mortality and number of hospitalization after the discharge from hospital. Clinical events (death and hospital readmission for HF) were recorded over a median follow-up period of one year. Date of death was confirmed by calling the patient’s family members.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS version 18.0 program was used for the statistical analysis, and the significance level was set at 5%. The Pearson chi-square test was used to determine the association between categorical variables. The odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were also calculated. Differences between frequencies were assessed using the chi-square test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statically significant.

Results

We included 234 patients who were divided into two groups; patients with acute heart failure: HF group: (126, 53%); and patients without heart failure: Non HF groups: (108, 64%). The characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of the patients were men, with a mean age of 65±13 years and a mean ejection fraction of 59% for the Non HF group and 46% for the HF group. All patients were NYHA class III or IV at the time of admission. Examination findings were similar between the two groups. Compared with Non-HF patients, HF group presented with significantly higher Nt proBNP, lipids and Troponin levels compared to whom HF patients (P≤0.001).

Table 1.

Epidemiologic, clinical and biological characteristics of the samples

| Total (n=234) | Heart failure (n=126) | Non heart failure (n=108) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| Male | 153 (64.8) | 73 (56.6) | 80 (74.8) | 0.003 |

| Female | 83 (35.2) | 56 (43.4) | 27 (25.2) | 0.006 |

| Age year mean (SD) | 65 (13) | 67 (13) | 65 (14) | 0.639 |

| History n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 106 (47.5) | 69 (59.5) | 37 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 77 (34.8) | 57 (49.1) | 20 (19) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 49 (22.1) | 36 (30.8) | 13 (12.4) | 0.001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 43 (19.2) | 39 (33.3) | 4 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 85 (44.3) | 37 (43.5) | 48 (44.9) | 0.485 |

| Renal failure | 58 (25.9) | 38 (32.5) | 20 (18.7) | 0.013 |

| Smoking | 129 (57.6) | 64 (54.7) | 65 (60.7) | 0.218 |

| Medications n (%) | ||||

| No medication | 50 (22,5) | 13 (11.4) | 37 (34.25) | 0.02 |

| Diuretics | 33 (14,9) | 31 (27.19) | 2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| ACEI | 47 (21.2) | 29 (25.43) | 18 (16.66) | 0.031 |

| Digoxin | 7 (23.2) | 5 (4.38) | 2 (1.8) | 0.071 |

| B2 agonists | 77 (74.7) | 30 (26.31) | 47 (43.5) | 0.121 |

| Others | 8 (3.6) | 6 (5.2) | 2 (1.8) | 0.07 |

| Physical exam mean (SD) | ||||

| BMI (Kg/m²) | 28.6 (4.88) | 29 (5.9) | 28.3 (3.49) | 0.09 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 141.4 (26.9) | 141.2 (28.3) | 141.5 (25.5) | 0.249 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.16 (20.1) | 72.2 (18.5) | 76.17 (21.4) | 0.063 |

| HR (beat/min) | 102 (22.04) | 99 (21.8) | 106.8 (21.6) | 0.524 |

| RR (cycle/min) | 24 (5.23) | 24.4 (5.5) | 24.71 (4.9) | 0.298 |

| SaO2 (%) | 85.5 (11.6) | 84.6 (12.9) | 86.4 (9.9) | 0.047 |

| Cardiac ultra sound | ||||

| LVEF % (SD) | 51 (16) | 46.1 (17) | 59.2 (11.6) | 0.05 |

| E/A mean (SD) | 2.06 | 1.57 | 2.7 | 0.006 |

| Biology mean (SD) | ||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 9.6 | 10.6 | 7.83 | 0.099 |

| Creatinin (µmol/L) | 129 (91) | 145 (109) | 110 (57) | 0.001 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 5.9 (1.2) | 6.47 (2.8) | 5.1 (0.94) | 0.7 |

| Uric acid (mmol/L) | 289 (72) | 301.8 (79.6) | 213 (57.4) | 0.007 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.72 (1.1) | 4.83 (1.21) | 4.39 (1.05) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerid (mmol/L) | 2.1 (0.41) | 2 (0.8) | 1.71 (0.87) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.99 (1.06) | 3.4 (0.7) | 2.96 (1.04) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.12 (0.05) | 1.04 (0.46) | <0.001 |

| NT pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 2708 | 4767.9 | 436 | <0.001 |

| Troponin (µg/L) | 0.86 (1.6) | 1.16 (1.8) | 0.09 | 0.001 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; RR: respiratory rate; SaO2: oxygen’s saturation; LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction.

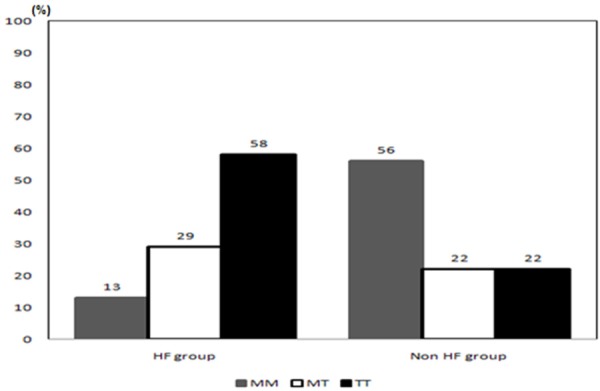

The genotypic frequencies of AGT* M235T polymorphism were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and were statistically different between HF and Non HF groups. 166 (71%) patients had at least one mutated allele (MT or TT). The TT genotype is more predominant in HF groups than in Non HF group (58% vs. 22%, P<0.001). In contrast, the non-mutated genotype (MM) was found more frequently among non-HF group (44% vs. 15%, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic characteristics of the patients

| Total n=234 | Heart Failure n=126 | NON Heart Failure n=108 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphisms n (%) | ||||

| MM | 68 (29.1) | 20 (15.87) | 48 (44.44) | <0.001 |

| MT | 68 (29.1) | 32 (25.39) | 36 (33.33) | <0.001 |

| TT | 98 (41.9) | 74 (58.73) | 24 (22.22) | <0.001 |

MM: methionine-methionine genotype; MT: methionine-threonine genotype; TT: threonine-threonine genotype.

Overall mortality was 17% (40 patients), with a higher incidence noted in the presence of mutation and was differently distributed according to the genotype: 13%, 11% and 20% respectively for MM, MT and TT. The majority of death were seen in HF group (n=31, 77%) and most were TT (58%). Among deaths belonging to the non-HF group the most common genotype was MM (56%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of deaths according to the diagnosis of heart failure and genotype.

Predictors of mortality were determined by performing logistic regression analysis. Heart failure and LVEF were the most predictive factors of mortality, with an OR 4 (95% CI, 1.7-9.5) and 3.7 (95% CI, 1.2-5.3) respectively.

However, for all patients, the TT genotype had an OR 1.61 (95% CI, 0.5-4.6) (P<0.001) and the MT genotype OR was 1.2 (95% CI, 0.4-3.2) (P=0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of mortality at one year

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.1 | [2.4-15.2] | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 1.1 | [0.6-2.2] | 0.7 |

| LVEF | 3.2 | [1.23-5.31] | <0.001 |

| Nt pro-BNP | 2.4 | [1.13-6] | 0.02 |

| HF diagnosis | 4 | [1.7-9.5] | 0.001 |

| Rehospitalization | 1.8 | [0.8-4.1] | 0.05 |

| Polymorphism | |||

| MM | 1 | - | - |

| MT | 1.20 | [0.4-3.2] | 0.057 |

| TT | 1.61 | [0.5 to 4.6] | <0.001 |

Discussion

Although the association between the AGT M235T polymorphism and cardiovascular diseases has been demonstrated in many previously published studies, the specific association of this polymorphism with heart failure is still controversial. Our study is the first to assess Tunisian patients presenting to the emergency room with dyspnea to identify the diagnostic and prognostic value of the genetic polymorphism of the AGT M235T gene. Ethnic difference polymorphism found between our population and European population compared to African and Asian can be justified by the high rate of cardiovascular disease in developed countries and more precisely the prevalence of HF. HF is around 20 to 30 per thousand in European countries [12], versus 3-20 per thousand in Asian countries [13]. This prevalence strongly increases with age from 75 years.

The RAAS plays an important role in the pathogenesis of HF by producing biologically active Angiotensin II by vasoconstriction, sodium retention myocardial fibrosis and other factors that modulated by RAAS pathways [14]. Many studies have investigated the relationship between AGT M235T polymorphism and hypertension. Chen et al. in 2003 found that the genotype of the AGT gene at exon-2 could be associated with an increased risk of essential hypertension [15]. In an Egyptian study, gene polymorphism of AGT was significantly associated with cardiovascular disease and was positively correlated with blood pressure. Moreover, the frequency of TT genotype was higher in patients with cardiovascular disease compared with healthy controls (47% versus 23%) [16].

Numbers of studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between this polymorphism and HF. Among these studies, Guerra et al. studied 363 HF patients and noted that the absence of the allele 235T contributes to the reduction of the risk of heart failure with a (P=0.001) [17]. Sanderson et al. were the first to explore the association of M235T polymorphism with heart failure in a cohort of Chinese patients, and their results showed that M235T polymorphism did not appear to be related to survival or severity of the syndrome [18]. In a Spanish study, Hernandez et al. demonstrated that the homozygous T allele of angiotensinogen is responsible for the incidence of coronary artery disease in the canary islands population; this relationship between AGT* M235T polymorphism and coronary artery disease could be involved in the increasing risk of HF among these patients [19]. Pilbrow et al. tested the association between M235T polymorphism and heart failure risk in a cohort in New Zealand and suggested that M235T polymorphism may provide prognostic information for long-term survival in heart failure patients [20]. This study suggests that TT genotype was predominant in heart failure patients compared to non HF group (58% vs. 22%, P<0.001). The majority of deaths were recorded in the heart failure group (31/40) and the TT genotype reached an OR of 1.61 (95% CI, 0.5-4.6), which is similar to the results found in the Caucasian population [OR=1.66 (95% CI, 1.13-2.46)] [19], but contrary to those in Asian patients [OR=0.62 (95% CI, 0.18-2.37)] [13] and those of a recent meta-analysis published by Jiang et al. [21]. Due to the absence of Tunisian publications on the AGT* M235T polymorphism, these results may contribute to enlarge the knowledge on the relevance of AGT* M235T polymorphism in the diagnosis of HF patients in Tunisian population.

Study limitation

It should be noted that our study has some significant limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the method of choice for follow-up would have been to call patients in order to achieve further questioning and a thorough clinical examination with para-clinical investigations but this method requires preparation and logistics which we do not have.

Nt pro-BNP is the gold standard in the diagnosis of HF in this study, but its value in nuclear when its level is found in the gray zone (400-1600 pg/mL). Echocardiography remains the gold standard for this disease but this facility is not always immediately available to most of emergency department services. Finally, our findings need to be validated and confirmed in other North African countries.

Conclusion

The association between AGT M235T polymorphism and HF seems confirmed in this study and the clinical as the genetic of this Tunisian population as comparable to other world populations. In addition, AGT M235T polymorphism is a good independent predictor for prognosis at one year.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MC, Straus SM, Hofman A, Deckers JW, Witteman JC, Stricker BH. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1614–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson G, Gibbs CR, Davies MK, Lip GY. ABC of heart failure. Pathophysiology. BMJ. 2000;320:167–170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleumink GS, Schut AF, Sturkenboom MC, Deckers JW, van Duijn CM, Stricker BH. Genetic polymorphisms and heart failure. Genet Med. 2004;6:465–474. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000144061.70494.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholls MG, Richards AM, Agarwal M. Theimportance of the reninangiotensin systemin cardiovascular disease. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:295–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall JE, Mizelle HL, Woods LL. The renin-angiotensin system and long-term regulation of arterial pressure. J Hypertens. 1986;4:387–397. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang WL, He HW, Yang ZJ. The angiotensinogen gene polymorphism is associated with heart failure among Asians. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4207. doi: 10.1038/srep04207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson M, Williams SM. Role of two angiotensinogen polymorphisms in blood pressure variation. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:865–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buraczyńska M, Pijanowski Z, Spasiewicz D, Nowicka T, Sodolski T, Widomska-Czekajska T, Ksiazek A. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms: Assessment of the risk of coronary heart disease. Kardiol Pol. 2003;58:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai CT, Lai LP, Lin JL, Chiang FT, Hwang JJ, Ritchie MD, Moore JH, Hsu KL, Tseng CD, Liau CS, Tseng YZ. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109:1640–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124487.36586.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Zhang L, Wang HW, Wang XY, Li XQ, Zhang LL. The M235T polymorphism in the angiotensinogen gene and heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2014;15:190–195. doi: 10.1177/1470320312465455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rader DJ, Hoeg JM, Brewer HB. Quantitation of plasma apolipoproteinsin the primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:1012–1025. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayasi BM. Contemporary trends in the epidemiology and management of cardiomyopathie and pericarditis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Heart. 2007;93:1176–1183. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solar A, Filippatos G. Esc Guidelines For The Diagnosis And Treatment Of Acute And Chronic Heart Failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–2442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman CM, Palmer LJ, McQuillan BM, Hung J, Burley J, Hunt C, Thompson PL, Beilby JP. Polymorphisms in the angiotensinogen gene are associated with carotid intimal-medial thickening in females from a community-based population. Atherosclerosis. 2001;159:209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Jiang YF, Cheng K. Meta-Analysis On The Association Of Agt M235t Polymorphism And Essential Hypertension In Chinese Population. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaker OG, Eldemellawy HH, Kassem HH. Angiotensinogen Gene M235t Polymorphism And Coronary Artery Disease In The Egyptian Population. A Genetic Association Study. Heart Mirror Journal. 2009;3:1687–6652. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saud CG, Reis AF, Dias AM, Cardoso RN, Carneiro AC, Souza LP, Fonseca AB, Ribeiro GS, Faria CA. Agt* M235t Polymorphism In Acute Ischemic Cardiac Dysfunction: The Gisca Project. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95:144–152. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2010005000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanderson JE, Yu CM, Young RP, Shum IO, Wei S, Arumanayagam M, Woo KS. Influence of gene polymorphisms of the renin-angiotensin system on clinical outcome in heart failure among the Chinese. Am Heart J. 1999;137:653–657. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arngrímsson R, Purandare S, Connor M, Walker JJ, Björnsson S, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Geirsson RT, Björnsson H. Angiotensinogen: A Candidate Gene Involved In Preeclampsia? Nat Genet. 1993;4:114–115. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilbrow AP, Palmer BR, Frampton CM, Yandle TG, Troughton RW, Campbell E, Skelton L, Lainchbury JG, Richards AM, Cameron VA. Angiotensinogen M235T and T174M gene polymorphisms in combination doubles the risk of mortality in heart failure. Hypertension. 2007;49:322–327. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253061.30170.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang WL, He HW, Yang ZJ. The angiotensinogen gene polymorphism is associated with heart failure among Asians. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4207. doi: 10.1038/srep04207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]