In May 2013 the actress Angelina Jolie informed the press that she had undergone bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) because she carried a maternally inherited pathogenic BRCA1 mutation. This decision created huge publicity worldwide [1] and led to enormous interest in hereditary breast cancer/genetic testing. Here we comment on our recently published research article in Breast Cancer Research and provide more recent observations. This reported a 2.5-fold increase in referrals of UK women with family histories of breast cancer 3–4 months following Ms Jolie’s revelation [1]. We also highlighted increased interest in BRRM; however, as it takes 9–12 months from initial BRRM enquiries to the operative procedure, we can now report a similar 2.5-fold increase in uptake of BRRM in the 6–24 months following this.

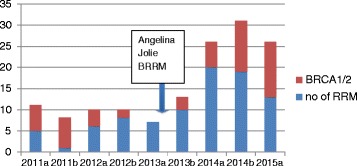

The Genesis Prevention Centre Family History clinic (GPCFHC) covers an extended population of around 5 million. Although the main impact of the Angelina effect was from June to November 2013, this trend continued through 2014 with increased referrals from 201 in January–June 2012 to 388 (odds ratio (OR) 1.93) in January to June 2014 and rising by 366 (OR 2.09) for the last 6 months to give a total of 754 for 2014. Women attending for risk assessment and discussions concerning BRRM, unprompted, still mention the effects of Angelina Jolie on their attendance anecdotally to clinic physicians and still reflect on the impact of her speaking publicly in their pre-surgery consultations with the clinical psychologist in 2015. A clear upward trend in BRRM can be seen starting around 6 months after the news announcement in May 2013 (Fig. 1). The number of high-risk women without BRCA1/2 mutations undergoing BRRM (n = 12; 18 months from January 2011) rose to 52 (18 months from January 2014). The number in mutation carriers rose from 17 to 31. The overall combined rise from 29 BRRMs to 83 was significant (high-risk women at GPCFHC, n = 2012; chi-square p < 0.0001). Again BRRM numbers annually had been stable at around 20 (2000–2011). We speculate that the BRRM rate rise was probably contributed by the ‘Angelina effect’. This effect was seen not just in carriers of BRCA1/BRCA2, but was actually greater in those without mutations. Nonetheless, 23/31(74 %) BRRMs in mutation carriers were in women >18 months after testing positive, indicating a delay in decision-making, whereas prior to 2013 the majority of women had BRRM within 18 months of testing positive [2]. There was a slight rise in the number of unaffected women newly testing positive for BRCA1/2 in Manchester from 81 to 116 in the 2 years before and the 2 years after Angelina’s announcement, although this could have been impacted by new National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines announced in June 2013 [3]. This research was exempt from ethical approval as this is an audit of clinical service and does not contain identifiable data.

Fig. 1.

Number of BRRMs carried out at Wythenshawe and Christie hospitals per 6-month period from 2011 and proportion with mutations in high-risk genes. a January–June, b July–December, red proportion with BRCA1/2/TP53 mutations, BRRM bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy

The present audit of further new referrals and BRRM rates indicates that the Angelina effect has been prolonged and has impacted on increased referral and BRRM rates. It would be interesting to see results from centres worldwide. Plans to offer breast cancer risk assessment on a population basis could further affect uptake of BRRM [4]. It is also possible that similar effects will be seen on the already increasing rates of contralateral mastectomy in women with breast cancer [5].

Acknowledgements

This audit was sponsored with support from the Genesis Breast Cancer Prevention Appeal. The authors would like to thank other surgeons undertaking BRRM not named as authors on this letter (John Murphy, Ged Lambe, Siobhan O’Ceallaigh and Stuart Wilson), and breast care nurse Laura Potter.

Abbreviations

- BRRM

Bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy

- GPCFHC

Genesis Prevention Centre Family History clinic

- OR

Odds ratio

Footnotes

See related research by Evans et al. http://www.breast-cancer-research.com/content/16/5/442

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and commented on drafts of the letter. DGE conceived the study, collated the data, and undertook the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

D. Gareth Evans, Phone: 00 44 (0)161 276 6206, Email: gareth.evans@cmft.nhs.uk.

Julie Wisely, Email: julie.wisely@mhsc.nhs.uk.

Tara Clancy, Email: Tara.Clancy@cmft.nhs.uk.

Fiona Lalloo, Email: Fiona.Lalloo@cmft.nhs.uk.

Mary Wilson, Email: Mary.wilson@uhsm.nhs.uk.

Richard Johnson, Email: Richard.Johnson@UHSM.NHS.UK.

Jonathon Duncan, Email: Jonathan.Duncan@UHSM.NHS.UK.

Lester Barr, Email: Lester.Barr@UHSM.NHS.UK.

Ashu Gandhi, Email: Ashu.Gandhi@UHSM.NHS.UK.

Anthony Howell, Email: Tony.Howell@ics.manchester.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Evans DG, Barwell J, Eccles DM, Collins A, Izatt L, Jacobs C, Donaldson A, Brady AF, Cuthbert A, Harrison R, Thomas S, Howell A, The FH02 Study Group, RGC teams. Miedzybrodzka Z, Murray A. The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:442. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans DG, Lalloo F, Ashcroft L, Shenton A, Clancy T, Baildam AD, Brain A, Hopwood P, Howell A. Uptake of risk reducing surgery in unaffected women at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer is risk, age and time dependent. Cancer Epid Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2318–24. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DG, Graham J, O’Connell S, Arnold S, Fitzsimmons D. Familial breast cancer: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;346:f3829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans DG, Howell A. Can the breast screening appointment be used to provide risk assessment and prevention advice? Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:84. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0595-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu NN, Barr L, Ross GL, Evans DG. Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy: review of risk factors and risk-reducing strategies. Int J Surg Oncol. 2015;2015:901046. doi: 10.1155/2015/901046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]