While a decade of research and policy interventions has begun to transform hospital discharge processes, research focused on hospital admissions is lacking. Emergency departments (EDs) are increasingly serving as portals of hospital admission, contributing to national concerns about ED volumes, wait times, and discontinuity of care.1Despite this, there is a paucity of research examining other options for hospital admission.

Direct admission, defined as admission to a hospital without receiving care in the hospital’s ED, is 1 alternative. Although direct admission has potential benefits for patients and health care systems, little is known about its use or effectiveness. To our knowledge, only 1 study has examined outcomes associated with pediatric direct admissions and there are no national statistics about the characteristics of this admission approach.2 To address this gap, we used a nationally representative data set to determine pediatric direct admission rates, characteristics, and costs relative to admission through EDs and characterize variation in direct admission rates across diagnoses and hospitals.

Methods

We analyzed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s 2009 Kids’ Inpatient Database, including nonneonatal, nonmaternal, and nonelective pediatric hospitalizations in children younger than 18 years.3 Our study received institituional review board approval from the Baystate Medical Center and was deemed exempt from participation consent. Interhospital transfers, including transfers to or from a different hospital or health care facility, were excluded as a result of our inability to accurately assess total hospital costs. Reasons for hospitalization were categorized using All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups.4Weighted direct admission frequencies, proportions, and hospital-level variation in direct admission rates were calculated for each All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Group. For the 10mostcommon All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups, we assessed differences between children admitted directly and those admitted through EDs using Rao-Scott χ2 tests for categorical variables and weighted t tests for continuous variables. Hierarchical generalized linear models with a random effect for hospitals were developed to assess differences in total hospital costs between children admitted directly and through EDs, using cost-to-charge ratios provided by the Kids’ Inpatient Database and controlling for the characteristics shown in the Table.6

Table.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics Associated With Direct and ED Admissions Among Children Hospitalized for the 10 Most Common Indications Weighted to Reflect National Estimatesa

| Characteristics | Direct Admission, No. (SD Weighted Frequency) [%] |

ED Admission, No. (SD Weighted Frequency) [%] |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | |||

| Age, y | 1.8 | 2.1 | <.01 |

| Female | 68 316 (2983)[45.3] | 248 463 (8224)[44.2] | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 67 801 (2920)[44.9] | 214 282 (8115)[38.1] | <.001 |

| Black | 15 694 (1141)[10.4] | 99 185 (7048)[17.6] | |

| Hispanic | 29 298 (3293)[19.4] | 131 068 (8520)[23.3] | |

| Other | 10 170 (663)[6.7] | 43 928 (3305)[7.8] | |

| Missing | 28 010 (3019)[18.6] | 74 292 (8806)[13.2] | |

| Insurance status | |||

| Public | 75 600 (4161)[50.1] | 306 304 (11 485)[54.4] | <.001 |

| Private | 66 573 (2602)[44.1] | 215 290 (7930)[38.3] | |

| Uninsured | 3231 (260) [2.1] | 23 010 (1881)[4.1] | |

| No charge/other/unknown | 5569 (567) [3.7] | 18 151 (1154)[3.2] | |

| Comorbid complex chronic conditionb | 14 062 (865)[9.3] | 52 007 (2643)[9.2] | .06 |

| APR-DRG disease severity | |||

| 1 (Lowest) | 90 015 (4060)[59.6] | 329 248 (10 709)[58.5] | .04 |

| 2 | 51 301 (2375)[34.0] | 198 331 (7136)[35.2] | |

| 3 | 8841 (583) [5.9] | 31 767 (1677)[5.6] | |

| 4 (Highest) | 815 (88) [0.5] | 3409 (254) [.6] | |

| Hospitalc | |||

| Geographic region | |||

| Northeast | 16 865 (1490)[11.2] | 127 032 (12 105)[22.6] | <.001 |

| Midwest | 37 289 (3178)[24.7] | 109 547 (10 175)[19.5] | |

| South | 61 227 (4250)[40.6] | 214 214 (14 651)[38.1] | |

| West | 35 592 (4539)[23.6] | 111 961 (10 702)[19.9] | |

| Bed size | |||

| Small | 14 254 (1363)[9.4] | 62 696 (8566)[11.1] | .51 |

| Medium | 38 420 (3984)[25.5] | 131 823 (10 806)[23.4] | |

| Large | 87 936 (5250)[58.3] | 321 592 (16 949)[57.2] | |

| Rural | 29 248 (1833)[19.4] | 60 147 (1803)[1.7] | <.001 |

| Hospital type, No. (%) | |||

| Children’sd | 16 954 (4179)[11.2] | 89 765 (12 722)[16.0] | .17 |

| Teaching | 63 489 (5230)[42.1] | 303 483 (17 484)[53.9] | <.001 |

| Hospital control | |||

| Public | 20 844 (1994)[13.8] | 71 769 (6365)[12.8] | .33 |

| Private | |||

| Nonprofit | 99 782 (5632)[66.1] | 385 077 (17 956)[68.4] | |

| Investor-owned | 19 983 (2693)[13.2] | 59 266 (6884)[1.5] |

Abbreviations: APR-DRG, All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Group; ED, emergency department.

The 10 most common reasons for hospitalization (APR-DRGs) included pneumonia, asthma, bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, appendectomy, upper respiratory tract infection, seizures, urinary tract infection, and bipolar disorder.

Identified using Feudtner complex chronic conditions algorithm.5

Characteristics missing for 8%of cohort for all variables except geographic region.

Freestanding children’s hospital according to the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions indicator.

Results

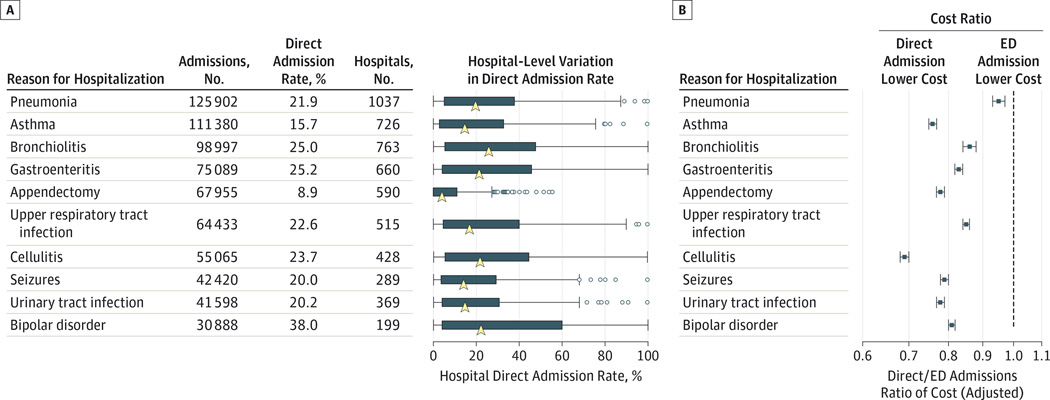

Of 1.47 million nonelective pediatric hospitalizations, 24.6% occurred via direct admission. The 10 most common diagnoses accounted for 49.2% of these hospitalizations (Figure). Among children with these diagnoses, children admitted directly were more likely to be white, privately insured, and had lower disease severity compared with children admitted through EDs (Table). There was substantial variation in direct admission rates across conditions, ranging from 8.9% for appendectomy to 38.0% for bipolar disorder (Figure). Similarly, we observed considerable hospital-level variation, with appendectomy showing the least variation and bipolar disorder showing the greatest variation in direct admission rates. In models adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics and disease severity, direct admissions were associated with 5% to 31% lower costs than ED admissions.

Figure.

Variation in Direct Admission Rates Across Conditions and Hospitals and Associated Adjusted Costs of Direct Admission Relative to Admissions Originating in Emergency Departments (EDs).

Discussion

Direct admissions represent approximately 1 in 4 unscheduled pediatric hospitalizations nationally, with characteristics of children admitted directly aligning with those more likely to have a medical home, including white race/ethnicity and private health insurance coverage.7 The substantial variation in direct admission practices across hospitals and conditions may be influenced by disparities in access to timely outpatient acute care as well as differences in hospitals’ and referring physicians’ capacities to facilitate admissions without ED involvement.

While the differences in costs between direct and ED admissions were striking, we acknowledge that our findings may have been influenced by residual confounding and we were unable to draw definitive conclusions about quality, safety, and effectiveness. In addition, direct admission points of origin were not reflected in these analyses. Nevertheless, our results suggest that increasing access to direction admissions may be a means to reduce ED volumes and health care costs. To accomplish this, research is needed to better understand key stakeholders’ admission preferences, the drivers of these cost differences, and conditions and procedures best suited for this admission approach.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Charlton Grant Research Program at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr Lagu is supported by award K01HL114745 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Shieh had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Leyenaar, Lagu, Lindenauer.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Leyenaar, Shieh, Pekow, Lindenauer.

Drafting of the manuscript: Leyenaar.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Shieh, Pekow.

Obtained funding: Leyenaar.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lagu, Lindenauer.

Study supervision: Lagu, Pekow, Lindenauer.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

References

- 1.Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1204431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leyenaar JK, Shieh MS, Lagu T, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Variation and outcomes associated with direct hospital admission among children with pneumonia in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):829–836. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2009 HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) website. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2023.111767. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All patient refined diagnosis related groups methodology overview. [Accessed October 20, 2014]; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Published 2003.

- 5.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population based study of Washington state. 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homer CJ. Health disparities and the primary care medical home: could it be that simple? Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]