Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is now a well-recognized and potentially severe complication of HSCT that carries a high risk of death. In those who survive, TA-TMA may be associated with long-term morbidity and chronic organ injury. Recently, there have been new insights into the incidence, pathophysiology, and management of TA-TMA. Specifically, TA-TMA can manifest as a multi-system disease occurring after various triggers of small vessel endothelial injury, leading to subsequent tissue damage in different organs. While the kidney is most commonly affected, TA-TMA involving organs such as the lung, bowel, heart, and brain is now known to have specific clinical presentations. We now review the most up-to-date research on TA-TMA, focusing on the pathogenesis of endothelial injury, the diagnosis of TA-TMA affecting the kidney and other organs, and new clinical approaches to the management of this complication after HSCT.

Keywords: Thrombotic microangiopathy, TA-TMA, Kidney disease, Complement activation, Hematopoietic cell transplant, Eculizumab

1. Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is now a well-recognized and potentially severe complication of HSCT that can lead to a high risk of death [1]. In those who survive, TA-TMA may be associated with long-term morbidity including hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), gastrointestinal or central nervous system disease, and pulmonary hypertension [2,3].

Over the past several years, there have been new insights into the incidence, pathophysiology, and management of TA-TMA. Specifically, TA-TMA can manifest as a multi-system disease occurring after various triggers of small vessel endothelial injury, leading to subsequent tissue damage in different organs. While the kidney is most commonly affected, TA-TMA involving organs such as the lung, bowel, heart, and brain is now known to have specific clinical presentations. Additionally, TA-TMA shares features with other thrombotic microangiopathies such as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), but is now considered a separate disorder occurring post-HSCT [4].

Our limited understanding of the pathogenesis of TA-TMA for the past 30 years has prevented the evaluation of rational therapeutic interventions. In contrast, greater understanding of the roles of the complement alternative pathway in aHUS and ADAMTS13 in TTP has led to targeted therapies to improve clinical outcomes in patients with these disorders [5–7]. Recently, we observed that both the classical and alternative complement systems may be involved in TA-TMA, supporting the potential use of complement modulating therapies in patients at highest risk for the worse outcomes [8]. We now review the most up-to-date research on TA-TMA, focusing on the pathogenesis of endothelial injury, the diagnosis of TA-TMA affecting the kidney and other organs, and new clinical approaches to the management of this complication after HSCT.

2. Clinical and histologic features

TA-TMA is identified when HSCT patients present with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, defined as de novo acute anemia and thrombocytopenia not explained by another process, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), excessive transfusion requirements, and schistocytosis in the blood. The diagnosis of TA-TMA requires a very high index of suspicion, especially in the detection of multi-organ involvement, as the diverse signs and symptoms of TA-TMA can be mistaken for other common transplant complications such as graft versus host disease (GVHD), infections, or medication-induced hypertension. TA-TMA can affect multiple organs, each of which exhibits specific features of injury. A tissue diagnosis can be challenging in HSCT recipients, especially children, at high risk for procedural complications. Therefore, relying on objective, organ-specific clinical criteria is critical to the timely recognition of TA-TMA after HSCT [9–11].

2.1. Kidney

The kidney appears to be the most common organ affected by small vessel injury associated with HSCT. There are several “renal” manifestations of TA-TMA, including decreased kidney function — as evidenced by a less-than-normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR), proteinuria, and hypertension [4,12,13].

It should be noted that, especially in children, serum creatinine and creatinine-based GFR estimates may not always be sensitive enough to detect renal dysfunction after HSCT because of the small body size and potentially low muscle mass of these patients [14–16]. In patients at risk for TA-TMA, kidney function should be monitored precisely and regularly. This strategy facilitates the early recognition of a decrease in GFR and thus the timely diagnosis of and treatment initiation for TA-TMA since prompt clinical interventions for TA-TMA appear to be associated with improved outcomes [17]. Therefore, we strongly suggest adopting alternative and apparently more sensitive modalities of GFR monitoring. Nuclear medicine isotopes or other injected tracers used for measuring GFR make for more complicated, invasive, and costly assessments than serum creatinine determinations but represent the gold standard for measuring kidney function [16]. Alternatively, serum cystatin C measurements allow more accurate GFR determinations than serum creatinine measurements if appropriate formulas are used to calculate cystatin C-based GFR estimations [18,19]. However, more research is needed to determine if potential non-GFR determinants of cystatin C, such as steroid use, thyroid disease, or inflammation, impact the precision of cystatin C to estimate kidney function in the HSCT population [16]. Until more data becomes available, pediatric centers should work with their nephrology and nuclear medicine colleagues to develop protocols that extend beyond mere serum creatinine measurements to accurately and repeatedly monitor GFR in their transplant recipients.

Regular urine monitoring for proteinuria is another valuable and relatively inexpensive tool to detect the development of TA-TMA Centers should thus use routine urinary screening for new-onset proteinuria as part of their peri-transplant care. In children with proteinuria during the daytime, this should include an assessment of a first-morning urine sample to rule out a benign orthostatic component. It may also include a more specific quantification of albuminuria, which has been associated with a higher risk of CKD and mortality among HSCT recipients [20,21]. Additionally, a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (normal for patients at least 3 years of age is <0.2 mg/mg with ratios of up to 0.7 mg/mg considered normal in younger children, and nephrotic range is >2 mg/mg) can be obtained in those patients with either evidence of proteinuria on routine dipstick analysis or in those with potentially false negative urinalysis results from dilute urine secondary to high volume intravenous fluids or tubular injury after HSCT. Sequential protein-to-creatinine ratios can then be used to more precisely follow proteinuria over time. Such quantitative assessments may also offer prognostic information (see below) in those individuals who develop TA-TMA [4].

The diagnosis of renal TA-TMA requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and should be especially considered in patients requiring substantially more antihypertensive therapy than would otherwise be expected in those receiving corticosteroid or calcineurin inhibitor therapy for GVHD prophylaxis or treatment [12,22]. Accordingly, we have adopted an unwritten rule at our center stating that “HSCT recipients are allowed one antihypertensive agent for receiving steroids, and a second for their calcineurin inhibitor: TA-TMA should be strongly considered in any patient requiring more than 2 antihypertensive medications, until proven otherwise” [22]. We refer providers to consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents especially since certain groups of HSCT patients, such as those with bone marrow failure syndromes and metabolic disorders, can have short stature due to their primary disease and blood pressure normal values are based on age, gender, and height [23].

If hypertension is indeed confirmed in a transplant recipient, it should be treated expeditiously. In pediatric HSCT recipients, especially those diagnosed with TA-TMA, blood pressure should accordingly be maintained at least below the 95th systolic and diastolic percentages for age, gender, and height and below 140/90 in adult patients [22,23]. Regarding the treatment of hypertension in HSCT recipients, several aspects are worth consideration. First, if the hypertension is at least in part due to TA-TMA, addressing this underlying cause obviously represents a highly reasonable first choice in management. Second, treating these patients with classes of antihypertensive agents that appear to target the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of their elevated blood pressure is intuitive: In patients on steroids, prescribing diuretics to counter steroid-induced fluid and sodium retention and using vasodilators to antagonize steroid-associated vasoconstriction appears reasonable, as does the latter treatment for patients on calcineurin inhibitors due to their vasoconstrictive properties [24]. In addition, there appears to be a role for antagonists of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) in patients with TA-TMA and hypertension as the endothelial inflammation seen in this patient population appears to activate the RAS [25]. At our center, we especially prefer the use of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), such as losartan, in this setting because they may target the RAS more broadly than angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. It is important to note that agents blocking the RAS should be used with caution in subjects with significant acute kidney injury, as commonly occurs in some subjects with TA-TMA. Therefore, they may offer a more favorable risk/benefit profile when used to treat the chronic complications of TA-TMA including proteinuria and/or hypertension. In patients with TA-TMA accompanied by both hypertension and significant acute kidney injury, vasodilating agents (in particular calcium channel blockers) may represent a relatively safe first line class of agents to treat their acute hypertension early in the disease process.

Renal dysfunction, proteinuria, and hypertension may also be observed in transplant recipients who do not develop TA-TMA [26]. Alternative etiologies, other than TA-TMA, in this patient population include, but are not limited to, exposure to nephrotoxic and prohypertensive medications and infections such as BK virus nephropathy [27,28]. Because of the complexity introduced into the care of transplant recipients by this plethora of findings and differential diagnoses, only repeated and diligent assessments by experienced clinicians will therefore result in a high likelihood of accurately diagnosing (or ruling out) TA-TMA and thus optimizing outcomes.

In view of these challenges, it is not surprising that the most reliable modality to diagnose TA-TMA is histological. Unfortunately, an autopsy diagnosis remains a more common way of obtaining such histological proof than would be desired. In patients who have evidence of renal dysfunction, a kidney biopsy is another valid approach to be considered if there is concern for TA-TMA, although this procedure carries an obviously increased risk of bleeding and other complications in these transplant recipients with their often present thrombocytopenia and hypertension [22].

In our experience, a carefully planned and performed kidney biopsy facilitates the diagnosis of TA-TMA and guides medical management, especially in those patients without irreversible complications. Histopathologic findings of TA-TMA are not limited to the demonstration of microthrombi in the glomeruli, but may also include characteristic patterns of C4d deposition in the renal arterioles, as previously described [29]. If kidney biopsy is considered in HSCT recipient, a careful determination of the risk and benefit of a kidney biopsy is critical, as is the performance of the procedure by an experienced team in a setting where the patient can be carefully monitored.

2.2. Lungs

Pulmonary arteriolar involvement with TA-TMA has been documented in several retrospective cohorts after transplantation. The exact incidence of pulmonary hypertension (PH) after HSCT is not known due to a lack of prospective studies. In the 40 patients reported in the literature from retrospective analyses, overall mortality was 55% (22/40), with 86% (19/22) of deaths attributed to PH and 14% (3/22) to relapse of the primary malignancy. HSCT patients with pulmonary TA-TMA often succumb to severe and acute PH after presenting with unexplained hypoxemia [30].

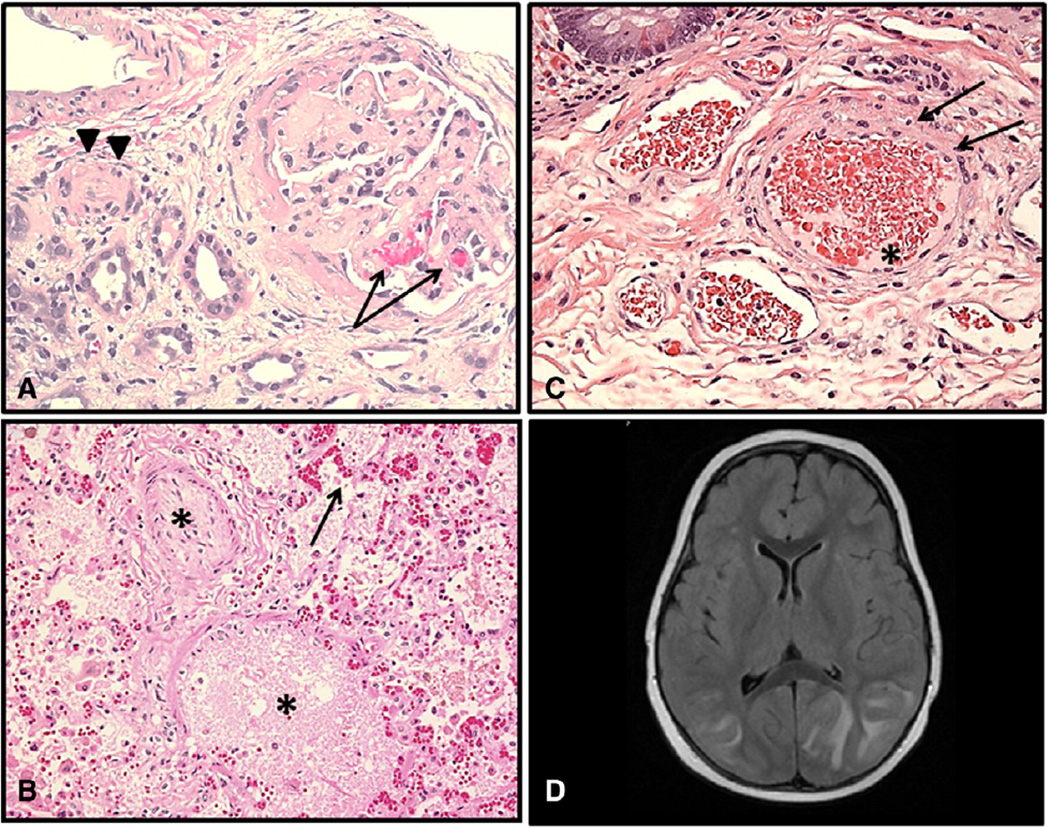

Microangiopathic changes in pulmonary arterioles present as denuded and injured endothelium, microthrombosis, and schistocyte extravasation into the lung interstitium (Fig. 1). These changes in the pulmonary vasculature lead to increased pulmonary artery pressures, right ventricular failure, and death [30–32]. The largest retrospective study described to date by Jodele et al. reported 5 cases of PH developing in pediatric HSCT patients after a prolonged course of untreated TA-TMA resulting in the death of 80% of patients with evidence of advanced TA-TMA and PH on autopsy specimens [9]. Untreated microangiopathy in pulmonary arterioles leads to fibroblast infiltration and smooth muscle proliferation resulting in pulmonary arterial hypertrophy which in turn leads to PH that can be acutely exacerbated by stressors such as infection or anesthesia, resulting in acute clinical deterioration [33].

Fig. 1.

Histologic examples of TA-TMA affecting various organs. (A) Renal cortex with glomeruli showing thickened capillary walls and occluded vessel lumens. Red blood cell fragments can be seen (arrows) trapped in the mesangial matrix (H&E stain; magnification ×200). Renal arteriole with separation of the endothelial cell layer and nearly occluded by endothelial debris (arrow heads) (H&E stain; magnification ×200). (B) Lung arteriole showing denuded endothelial layer with large amount of debris nearly occluding vascular lumen (star) Red blood cell fragments extravagated into interstitial tissue (arrow) (H&E stain; magnification ×200). (C) Submucosal arterioles of the small bowel showing injured endothelial cells and red cell extravasation (arrows). Vessel lumen is occupied by schistocytes and fibrinoid debris (star) (H&E stain; magnification ×200). (D) Brain MRI: hyperintense FLAIR signal involving the bilateral (left > right) cortex and subcortical white matter. Effacement of sulci suggests associated swelling. Findings are suggestive of posterior reversible encephalopathy (PRES).

Our group at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center recently completed a prospective echocardiographic screening study with the goal of determining an association of TA-TMA with pulmonary vascular injury presenting as elevated right ventricular (RV) pressure. One hundred consecutive HSCT patients underwent scheduled echocardiographic screening on day +7 after transplantation, independent of their clinical condition. Raised right ventricular pressure at day +7 (n = 13, 13%) was significantly associated with the development of later TA-TMA (p = 0.004), and may indicate early vascular injury in the lungs in patients with thrombotic microangiopathy [34].

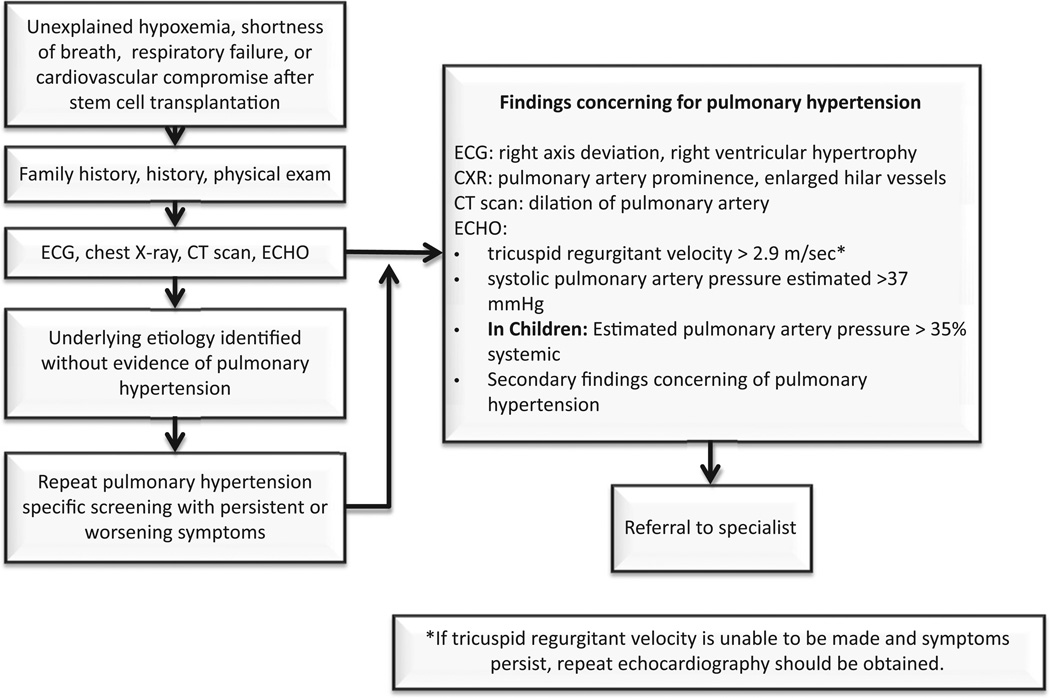

The differential diagnosis of respiratory symptoms after HSCT is broad making the diagnosis of pulmonary microangiopathy and PH difficult, so HSCT patients with unexplained hypoxemia or respiratory distress after transplantation should receive a thorough evaluation for PH and TA-TMA [30]. Transthoracic echocardiography is an excellent noninvasive screening tool for PH [35,36]. Dedicated echocardiography specifically targeting signs of PH should be requested and should be interpreted by a cardiologist or PH specialist. It is important to note that in most institutions, routine echocardiography requested to evaluate cardiac function will not include a comprehensive right-sided heart evaluation and will not be sufficient to rule out PH. For this reason, specific echocardiographic protocols have been developed as previously published by Dandoy et al. (BBMT 2013, Appendix 1) [30]. Fig. 2 displays an algorithm for the non-invasive evaluation of HSCT recipients with TA-TMA at risk for PH. Cardiac catheterization remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of PH, but given the potential risks of cardiac catheterization in a population with other significant comorbidities, such as those after HSCT, invasive testing is reserved for those in whom a clear diagnosis cannot be achieved with noninvasive means.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for evaluation of pulmonary hypertension in HSCT patients with TA-TMA.

2.3. Gastrointestinal tract

There is a growing body of evidence outlining the impact of TA-TMA on the small vasculature of the gastrointestinal tract after HSCT. Diarrhea and vomiting, especially when accompanied by significant abdominal pain and bleeding caused by ischemic bowel changes due to microangiopathy, may be signs of intestinal TA-TMA (or iTMA). Unidentified iTMA can lead to significant morbidity and mortality [37,38]. However, similar gastrointestinal symptoms may also be findings of acute gut GVHD or infectious colitis, making the clinical diagnosis difficult. Histologic tissue analysis by an experienced pathologist is often crucial for differentiating between GVHD and iTMA (Fig. 1).

Inamoto et al. reported 92% (80/87) of patients having histologic evidence of TA-TMA on colonoscopic biopsies that were obtained for a clinical diagnosis of acute gut GVHD. Tissue examination showed histologic signs of microangiopathy including small vessel endothelial swelling or denudation, non-inflammatory crypt degeneration, detachment or apoptosis of epithelial cells, wedge-shaped segmental injury, and/or interstitial edema with hemorrhage or fragmented red blood cells (Fig. 1). Only 30% of evaluated patients had histologic evidence of GVHD itself [11]. Additionally, smaller studies have also included both endoscopic and post-mortem sampling of the gut which have shown microscopic signs of GVHD and iTMA occurring at the same time [39–41]. Because the diagnosis of iTMA is contingent upon evaluating the vasculature of the submucosa, identification is dependent upon appropriate sampling by the consulting proceduralist and pathologist reviewing specimens. Differentiation of iTMA from GVHD is very important since continuation of calcineurin inhibitors can significantly worsen symptoms in affected patients [11]. This relationship was supported by an elegant experiment showing that rats exposed to tacrolimus can undergo microangiopathic changes in the bowel within days of drug exposure [42]. When tacrolimus was removed, the process was reversible. A similar phenomenon has been documented in patients receiving the same class of medication to suppress graft rejection in the solid organ transplant setting [43,44].

Our recent review of a prospective clinical cohort of HSCT patients showed that severe gastrointestinal bleeding was observed only in patients with systemic signs of TA-TMA and histologic iTMA diagnosis was supported by tissue examination of deceased patients [4]. However, the diagnosis of iTMA in the absence of other systemic signs of TMA is possible and must be taken under careful consideration when approaching transplant patients with concerning symptoms [11]. Table 1 lists our currently proposed histologic signs of iTMA based on the published literature, but future work should be dedicated to establish objective clinical and histologic iTMA diagnostic criteria to aid in the selection of appropriate therapies after HSCT.

Table 1.

Criteria for diagnosis of intestinal TA-TMA.

|

2.4. Central nervous system

Although neurologic deficits have been reported in up to half of all patients with TA-TMA, a detailed understanding of central nervous system (CNS) disease remains elusive [45,46]. Manifestations can include confusion, headaches, hallucinations, or seizures. Although the CNS vasculature can certainly be affected by TA-TMA,the most common TA-TMA-related CNS injury is likely due to acute uncontrolled TMA-associated hypertension, including PRES (see renal section above) that may result in CNS bleeding. PRES may present with headaches, visual disturbances, mental status changes, or seizures. Neuroimaging reveals signal abnormalities in posterior portions of the brain but can include the brainstem, cerebellum and basal ganglia, and symptoms are often preceded by significant hypertension [47,48]. This highlights again the crucial nature of aggressive hypertension management in HSCT recipients, as well as the importance of good hemostasis. While limiting platelet transfusions in the setting of active microangiopathic disease would be ideal so as not to fuel the underlying disease process, often times in practice this is superseded by the need to prevent associated bleeding complications.

2.5. Polyserositis

Polyserositis is a common but often missed feature of TA-TMA that results from generalized vascular injury. It often presents as refractory pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, and ascites without overall generalized edema even in patients with nephrotic range protein-uria. Polyserositis after allogeneic HSCT is often thought to be a presentation of chronic GVHD [15,49]. TA-TMA should be included in the differential diagnosis, especially in patients who do not exhibit other symptoms of GVHD, like chronic skin or mucosal changes and in patients with polyserositis after autologous HSCT. Patients with TA-TMA most likely will have proteinuria and hypertension in addition to signs of microangiopathic anemia, signs that are far less common in those diagnosed with chronic GVHD.

Pericardial effusions alone or as a part of polyserositis are also strongly associated with TA-TMA after HSCT. Lerner et al. found a 45% incidence of pericardial effusion in patients with TA-TMA, a risk that it is much higher than the reported incidence in the overall HSCT population [10,50,51]. Dandoy et al. supported this observation by documenting a 52% incidence of pericardial effusion in patients with TA-TMA in a prospective study using echocardiographic screening in 100 consecutive HSCT patients [34]. The pathogenesis of this phenomenon in patients with TA-TMA is not yet understood, but these patients often have intractable pericardial effusions requiring medical or surgical interventions until TA-TMA is controlled. HSCT patients that develop chest pain, tachycardia, cardiomegaly on chest X-ray, or have signs of hypoxemia should be evaluated for pericardial effusion through echocardiography and tested for laboratory signs of TA-TMA [52,53].

3. Incidence and risk factors

The incidence of TA-TMA is 10–35% as reported in the largest retrospective reviews and studies examining renal and other tissues [22]. In our prospective TA-TMA study, 39% of patients met published diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA, but 18% had severe disease likely affecting overall post-transplant outcomes [4]. The incidence of severe TA-TMA was similar to those from retrospective reviews, likely capturing the most advanced cases requiring clinical interventions.

TA-TMA is more common after allogeneic HSCT, but also remains a significant complication of autologous transplantation. In autologous recipients, TA-TMA istypically reported as severe, multi-visceral disease in patients with neuroblastoma receiving carboplatin, etoposide, and melphalan (CEM) high dose chemotherapy regimens followed by autologous stem cell infusion [15,54].

Several other risk factors published in retrospective studies have been associated with the development of TA-TMA after allogeneic HSCT, most notably medications used in the course of transplant and infectious complications. Conditioning agents including busulfan, fludarabine, cisplatin, and radiation may increase the risk of later TA-TMA [55–59]. Other medications commonly reported to be associated with TA-TMA include those used for GVHD prophylaxis, especially the calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and cyclosporine and the newer mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors [59–63].

Some have speculated that GVHD itself increases the risk for TA-TMA, but reports have been conflicting and limited by retrospective study designs [64–70]. Finally, viral infections are often considered to be a “trigger” for TA-TMA, as patients showing signs of small vessel injury can also have concomitant infections such as CMV, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, HHV-6, and BK virus [54,71–73]. The exact mechanisms leading to endothelial injury during primary viral infection or reactivation remain unknown. It remains to be determined if viral infections are a cause of small vessel endothelial injury in the context of TA-TMA or are simply a manifestation of overall disease severity in acutely ill HSCT recipients.

Similarly, the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine and tacrolimus are often implicated in TA-TMA following both HSCT and solid organ transplantation in retrospective reports, but their association with TA-TMA, independent of the development of acute GVHD, has been difficult to discern [74]. Most recently, Labrador et al. reviewed 102 adult allogeneic recipients from 2007 to 2012 who received GVHD prophylaxis with either tacrolimus/methotrexate (n = 34) or tacrolimus/sirolimus (n = 68) and found no difference in the risk of TA-TMA between the groups [75]. However, the authors did note that patients with high grade acute GVHD, a prior transplant, and very high tacrolimus levels (>25 ng/ml) had independently higher risks of developing TA-TMA. Shayani et al. reviewed 177 patients receiving allogeneic HSCT at their institution from 2005 to 2007 with a combination of sirolimus and tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis. While median tacrolimus levels during the first 30 days after transplant were not associated with developing TMA, a sirolimus level >9.9 ng/ml in the first 2 weeks was independently associated with a doubling of the risk for TMA. Additionally, acute GVHD and myeloablative conditioning were also associated with a higher risk of TMA [76].

Although several studies have identified an association between the development of TA-TMA and acute GVHD, the relationship is confounded by exposure to calcineurin inhibitors and retrospective analyses, precluding an accurate examination of temporal associations [54,64, 77]. Nevertheless, a causal link between acute GVHD and the subsequent development of TA-TMA is biologically plausible given that during engraftment, donor T-lymphocytes first encounter host endothelial cells, which are the primary target cells involved in patients with TA-TMA [59,65,66]. In support of this theory, Changsirikulchai et al. showed in an autopsy study that the odds of developing TA-TMA were four times higher in patients with acute GVHD than in patients without it [64].

Similarly, expanding on their previous case report, Mii et al. recently noted an association between GVHD, both acute and chronic, in 7 patients developing TA-TMA after HCT [78,79]. In these patients undergoing HCT, they observed histological findings very similar to acute cellular and/or antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplant, supporting an inflammatory mechanism of injury, or “GVHD”, in the pathogenesis of TA-TMA. Specifically, they observed glomerulitis, tubilitis and glomerular C4d deposition - a marker of classical complement activation - in the kidney biopsy and autopsy specimens from their cohort. We recently reviewed kidney tissue specimens from children undergoing HSCT and compared C4d staining, a marker of antibody mediated rejection in kidney transplant recipients, in those subjects with (n = 8) and without (n = 12) histological evidence of TA-TMA. We observed that diffuse or focal renal arteriolar C4d staining was more common in subjects with histologic TA-TMA (75%) compared to controls (8%). While these studies are small, further research is needed to determine if C4d staining of tissue samples identifies specific areas of injury, and with respect to the kidney, if small vessel C4d staining may explain the significant and often refractory hypertension typical of TA-TMA [29].

Classically, GVHD involves the epithelial tissues of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs. It remains conceivable that GVHD could also damage endothelial tissue and therefore TA-TMA may represent, “renal GVHD” [21,67]. Along these lines, Sadeghi et al. recently demonstrated the tissue-specific injury patterns and expression of inflammatory genes in their mouse model of GVHD. They found that activation of inflammatory cytokines and histological evidence GVHD was similar in the liver - an organ known to be affected by GVHD - and the kidney, an organ that until recently was not believed to be a target of GVHD [80]. However, a causal link between TA-TMA and GVHD remains to be proven. Evidence against an association includes the fact that both complications can occur independently of each other and increasing immunosuppression, the primary treatment for GVHD, typically does not prevent or treat TA-TMA [56,81, 82]. TA-TMA is also well documented after autologous HSCT and in patients after allogeneic HSCT without any evidence of GVHD. Our prospective study in children and young adults showed that GVHD was not a risk factor for the development of TA-TMA in a time dependent analysis. This study was not able to examine cyclosporine as a risk factor for TA-TMA as >95% of study subjects received cyclosporine for GVHD prophylaxis and there was no difference in cyclosporine trough levels between patients with TA-TMA and those without.

4. Diagnostic criteria

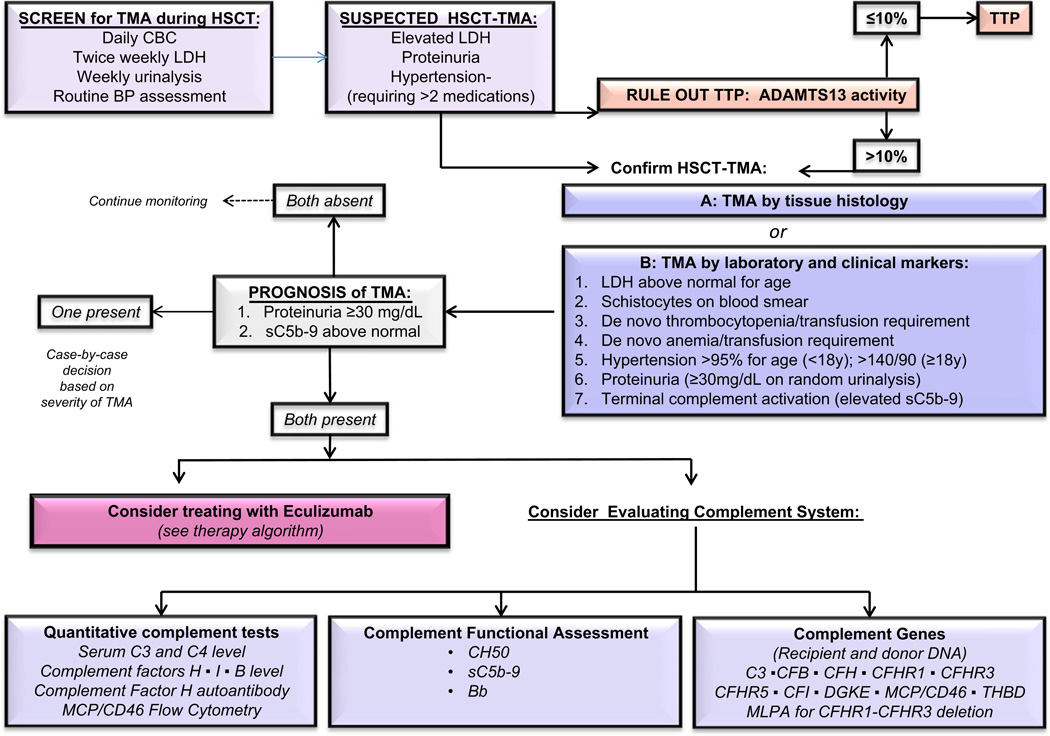

The limited feasibility of tissue diagnosis after HSCT has led to the development of noninvasive diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA that have been updated several times [54,82,83]. A retrospective validation study published by Cho et al. in 2010, outlined limitations in the prior guidelines and expanded on them to include the concept of “probable-TMA,” which did not require renal or neurologic findings for a diagnosis of TA-TMA [84]. Indeed, our prospective study showed that serum creatinine is a very poor marker of acute kidney injury (AKI) after HSCT and neurologic symptoms are mainly prevalent in severe multi-visceral TA-TMA. Prospectively proposed guidelines suggested including proteinuria of >30 mg/dL and hypertension (disproportional to what would be expected from steroid and calcineurin use) as early markers of kidney injury in addition to already established hematologic disease markers (Table 2) [4]. This study suggested that TA-TMA should be suspected when patients after HSCT develop an acute elevation in LDH and have proteinuria and severe hypertension, since other markers such as schistocytes appear later in the disease course. Patients with 5 or more of 7 TA-TMA associated markers listed in Table 2 had much more severe disease in our prospective TMA study in which all markers were monitored starting prior to the transplant conditioning regimen. Terminal complement activation as measured by the plasma level of the soluble membrane attack complex (sC5b-9) and proteinuria were shown to be the most significant risk factors in patients with TA-TMA who developed the worse outcomes after HSCT. Specifically, patients with TA-TMA who had elevated sC5b-9 above normal and proteinuria >30 mg/dL at the time of TA-TMA diagnosis had an 84% non-relapse mortality rate at 1 year after HSCT, while all TA-TMA patients without these features recovered from microangiopathy and survived. Our diagnostic and risk assessment algorithm suggests to initiate close monitoring in HSCT patients with elevated LDH, proteinuria and hypertension and to consider prompt clinical intervention with complement inhibitors such as eculizumab in patients who exhibit proteinuria and complement activation at the time of TA-TMA diagnosis (Fig. 3). Testing for plasma sC5b-9 level at TA-TMA diagnosis is strongly suggested as it will aid in determining patients who may benefit from complement blocking therapy.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA.

| The diagnosis of TA-TMA maybe be established | |

|---|---|

| A. Microangiopathy diagnosed on tissue biopsy | |

| or | |

| B. Laboratory and clinical markers indicating TMA | |

| Laboratory or clinical marker |

Description |

|

1Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) |

Elevated above the upper limit of normal for age |

| 2Proteinuria | A random urinalysis protein concentration of ≥30 mg/dL |

| 3Hypertension | >18 years of age: a blood pressure at the 95th percentile value for age, sex and height. |

| ≥18 years of age: a blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg. | |

|

4De novo thrombocytopenia |

Thrombocytopenia with a platelet count <50 × 109/L or a ≥50% decrease in the platelet count |

| 5De novo anemia | A hemoglobin below the lower limit of normal for age or anemia requiring transfusion support |

|

6Evidence of microangiopathy |

The presence of schistocytes in the peripheral blood or histologic evidence of microangiopathy on a tissue specimen |

|

7Terminal complement activation |

Elevated plasma concentration of sC5b-9 above upper normal laboratory limit |

Present: consider diagnosis of TA-TMA. Monitor very closely.

at TA-TMA diagnosis indicate high features associated with poor outcome: consider therapeutic intervention.

Fig. 3.

Diagnosis and risk assessment algorithm for TA-TMA after HSCT.

TA-TMAshares numerous features with TTP including thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, increased lactate dehydrogenase, microangiopathic changes, renal failure and sometimes neurologic changes but their basic mechanisms and clinical courses, however, differ. TTP is secondary to severely reduced activity of von Willebrand factor cleaving protease (ADAMTS13). Plasma ADAMTS13 activity can be moderately decreased in the setting of TA-TMA, especially in cases presenting with acute severe hemolysis, however is not severely decreased (<5–10% activity) as seen in patients with TTP. Since acute management of TTP would require prompt initiation of therapeutic plasma exchange, it is a good practice to measure ADAMTS13 activity in HSCT patient with signs of thrombotic microangiopathy so as not to miss the diagnosis of TTP, even though TTP is very rare after HSCT [85,86].

5. Mechanisms of endothelial injury: focus on complement system abnormalities

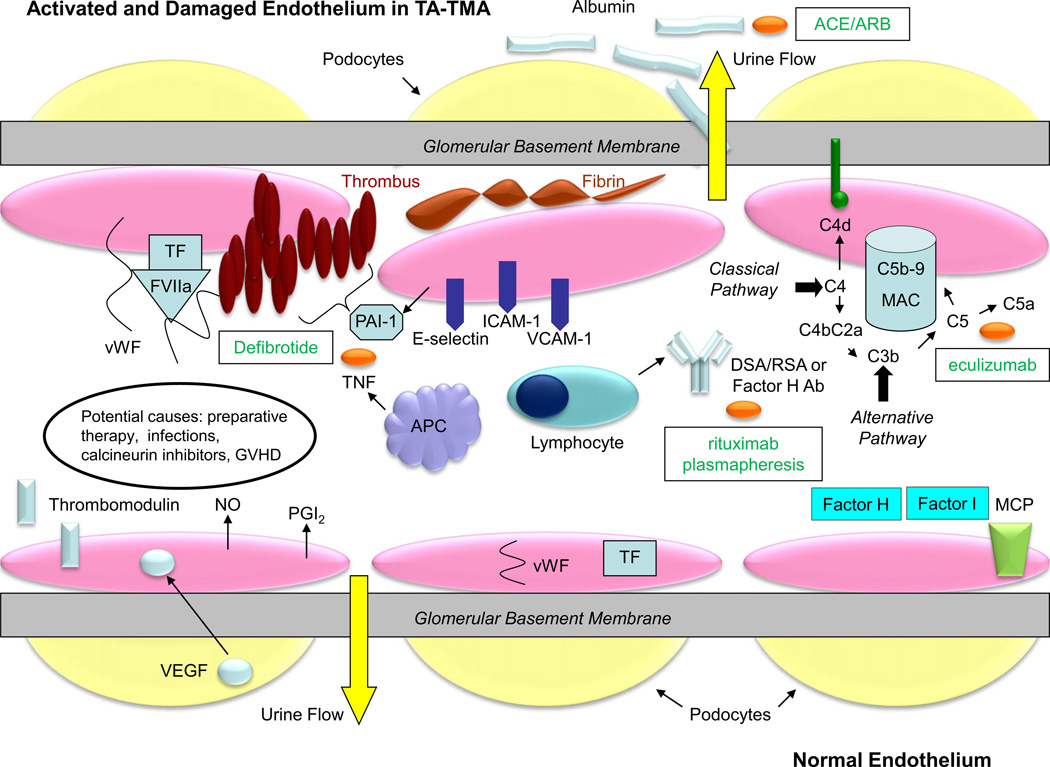

Vascular endothelial injury after HSCT is likely multifactorial. Most markers of endothelial injury have been evaluated in HSCT recipients with GVHD or veno-occlusive disease of the liver (VOD). Few studies have specifically examined markers of endothelial injury in subjects with TA-TMA [87]. In Fig. 4, we summarize the most frequently reported markers of endothelial injury in patients with thrombotic microangiopathy, not limited to HSCT-associated TMA, and also describe potential therapeutic options.

Fig. 4.

Molecular pathogenesis and potential treatments for thrombotic microangiopathy in the glomerular endothelium. The glomerular filtration barrier consists of fenestrated endothelial cells, the glomerular basement membrane, and the podocyte foot processes. In normal endothelium (bottom half of the figure), podocytes produce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which binds to receptors in the endothelial cells, maintaining the integrity of the microvasculature. Endothelial cells produce nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2) and express thrombomodulin on their surface, preventing the activation of the coagulation cascade and complement. Tissue factor (TF) and von Willebrand factor (VWF) remain internalized, and factor H, factor I, and membrane co-factor protein (MCP) block the activation and amplification of complement [54,122,123]. In TMA (top half of the figure), the endothelium becomes damaged and activated. TF is expressed on the cell surface, binding factor VIIa (FVIIa) and VWF, which promote thrombus formation with activated platelets (brown ovals). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) prevents fibrinolysis of the clot. Activated endothelial cells express adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1), permitting the local recruitment of antigen presenting cells (APCs) and lymphocytes. Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) is released from the endothelial cell and binds to the Tie2 receptor which leads to vascular destabilization and vascular leakage. Activated APCs expressed tumor necrosis factor (TNF), potentiating the inflammatory response. Activated lymphocytes produce potentially donor specific (DSA, solid organ transplant) or recipient specific (RSA, HSCT) antibody, which can activate the classical complement cascade. Anti-factor H antibody can prevent inhibition of the alternative complement pathway. Activated complement leads to generation of the membrane attack complex (MAC), which induces cell lysis. C4d remains covalently bound to tissue and is a marker of complement activation. Tissue damage and inflammation leads to fibrin deposition. Ultimately, albumin leaks into the urinary space when the integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier is lost [6,54,65,67,123–127]. Potential treatments for TA-TMA are shown in the boxes. Defibrotide blocks PAI-1 and attenuates the effects of TNF. Rituximab may reduce the production of damaging antibodies (DSA, RSA, or anti-factor H antibody) and plasmapheresis may remove them. Plasmapheresis may also remove Ang-2. Eculizumab stops the progression of the complement cascade to the MAC. Finally, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy reduces proteinuria, preventing inflammation and the progression of CKD [112,128–130].

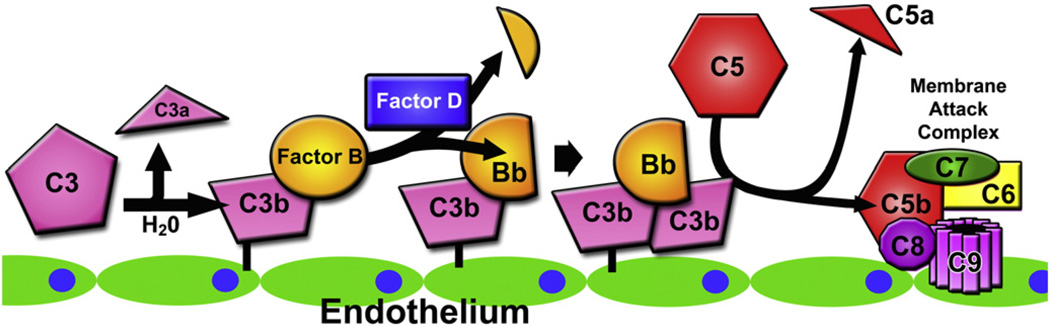

The most recent data indicates that TA-TMA belongs to the groups of disorders that can present with complement system dysregulation. The role of the complement system has been well-established in the pathogenesis of other thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs), perhaps most notably in aHUS where defects in one or more regulatory proteins of the alternative pathway of the complement system allow for the uninhibited formation of the C3 convertase C3bBb on the surface of endothelial cells. Formation of additional molecules of C3b, the activated form of C3, by this convertase on the cell surface leads to the formation of the C5 convertase C3bBb•C3b, ultimately promoting the formation of the lytic complex C5b-9 and the potent anaphylatoxin C5a, causing injury to the endothelial cell and ultimately all of the characteristic clinical findings of TMA. Defects in complement regulation in aHUS can be either genetically determined by mutations in genes such as CFH, CFI, MCP, CFB, C3, and CFHR5 or acquired through the formation of neutralizing autoantibodies to Factor H (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Alternative complement pathway dysregulation and endothelial injury. Activation of C3 by hydrolysis leads to formation of C3b with a reactive thioester moiety, which covalently binds to an endothelial cell surface. C3b binding is enhanced on endothelial cells injured through many convergent pathways. Once C3b is bound to the cell surface, Factor B binds to C3b and is cleaved by Factor D to its enzymatically active fragment Bb. The C3bBb complex serves as a C3 convertase, generating more molecules of C3b, which can in turn complex with new molecules of Bb, leading to amplification of this pathway. C3bBb bound to a second molecule of C3b (C3bBb•C3b) serves as a C5 convertase, which cleaves C5 into C5a and C5b. This fragment of C5b serves as a nidus for the formation of the lytic membrane attack complex (C5b-9) on the endothelial cell surface, furthering endothelial cell injury.

In our previously published experience, we have identified complement regulatory defects in a series of six patients who developed TA-TMA after HSCT [8]. These patients exhibited a high prevalence of a heterozygous CFHR3–CFHR1 deletion (83%) compared to that found in the donor population (33%), which is comparable to that found in the general population, where the prevalence of this deletion is approximately 25% [88]. Half of our patients (3 of 6) with TA-TMA after HSCT also demonstrated the presence of Factor H autoantibodies, compared to none (0 of 18) in a control population of patients who did not develop TA-TMA. Haploinsufficiency of CFHR1 leading to a partial deficiency may lead to deregulated C5 convertase activity, whereas neutralizing autoantibodies to Factor H may also lead to uninhibited alternative pathway C3 convertase formation on the cell surface, suggesting a prominent role for complement in the disease pathogenesis of HSCT-related TMA. A majority of the patients in this published series (67%) responded favorably to antibody-depleting therapies such as rituximab and therapeutic plasma exchange, possibly by neutralizing Factor H antibody activity.

Based on these observations and improved understanding of the role of complement in TA-TMA, we have recently published our experience using eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed towards C5 which prevents formation of the C5b-9 membrane attack complex and has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of aHUS (see treatment section below) [17,89]. In brief, in our case series of 6 patients with HSCT-TMA treated with eculizumab, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic monitoring of eculizumab serum levels and total complement hemolytic activity (CH50) was used to ensure a therapeutic medication trough level of >99 µg/mL. All HSCT patients required higher or more frequent dosing of eculizumab than the standard dosing for children with aHUS to achieve adequate and effective levels of eculizumab and clinical response. Four patients who responded favorably to the drug were able to achieve and maintain an adequate trough level, whereas the two patients who did not respond to the drug, and ultimately succumbed to severe multisystem organ dysfunction, were unable to achieve an adequate eculizumab trough level. Our extended experience with now 18 patients treated with eculizumab also supports the need for more intense eculizumab dosing to achieve normalization of sC5b-9 levels and resolution of TA-TMA with sustained complete response rates of >60%. These experiences underscore the role of complement as a mediator of this disease, and that complement-directed therapy and in particular, eculizumab, may have a prominent role in this disease’s treatment.

Whereas complement dysregulation, uncontrolled complement activation on cell surfaces, and resulting cellular injury are the primary biological mechanisms leading to endothelial cell injury in aHUS, emerging experimental and clinical evidence suggests that complement plays a secondary but direct role in facilitating other primary forms of TMA. Ultralarge multimers of von Willebrand factor present in severe ADAMTS13 deficiency that unfold under shear stress in the microvasculature can activate complement, and a murine model of TTP demonstrated positive immunofluorescence for complement activation products [90]. Furthermore, elevated circulating levels of complement activation markers C3a, C5a, and sC5b-9 were found to be present in patients with relapsed TTP, which improved with plasmapheresis [91,92].

Similarly, Shigatoxin has been demonstrated in vitro to disrupt the activity of Factor H as a cofactor for Factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b to its inactive form iC3b, and elevated plasma levels of the Bb fragment of Factor B as well as sC5b-9 were demonstrated in patients with Shigatoxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS) [93, 94]. Based on this evidence, a small series of patients with severe central nervous system manifestations of STEC-HUS was successfully treated with eculizumab, leading to the widespread use of eculizumab in the 2011 German STEC-HUS epidemic [95–97]. This has led some investigators to speculate that all TMAs are complement-mediated disease [98]. The complement system also appears to participate in the pathogenesis of “secondary” forms of TMA such as that in the context of systemic lupus erythematosus, HELLP syndrome during pregnancy, malignant hypertension, and TMA associated with calcineurin inhibitor exposure in solid organ transplantation, as mutations in complement regulatory genes have been identified in such patients [99–102]. Indeed, such evidence may suggest that all forms of TMA may be either facilitated by, or caused by, activation of the complement system.

Based on our published experience describing the complement dysregulation identified in patients with HSCT-TMA as well as the response of these patients to complement-directed therapy, combined with additional evidence that complement plays a role in the pathogenesis of this entity, TA-TMA after HSCT can be grouped with other complement-mediated disorders. However, there are also distinct features of HSCT associated TMA that separates it from primary forms of TMA such as aHUS and TTP, as well as other secondary forms of TMA. One such distinguishing feature is the convergent multifactorial nature of endothelial injury that begins the pathological process. Iatrogenic factors during the HSCT are unfortunately very common and may all serve as endothelial insults. Many of these factors, particularly GVHD and infections, may also stimulate multiple complement pathways, propelling the process forward. Recipient and donor, or both, genotypes may play a significant role in tissue susceptibility to develop TA-TMA. Another distinguishing feature after HSCT is immune dysregulation occurring in the post-HSCT period leading to Factor H autoantibody formation and creating an opportune environment for complement activation on the injured endothelium. Indeed, all patients with these autoantibodies in our published series were negative for these autoantibodies prior to transplantation and some of them did not have identified genetic predisposition for CFH antibody formation as reported in DEAP-HUS, indicating that the complement dysregulation may be a de novo process in HSCT patients with or without antibody formation. HSCT patients with TA-TMA also respond to complement blockade in a different way than patients with aHUS, requiring a specific eculizumab dosing schedule for the HSCT population (see below) and are able to discontinue complement blocking therapy after TA-TMA process is aborted, unlike patients with aHUS in whom lifelong therapy is recommended.

6. Outcomes and prognosis

Kidney injury, both acute (AKI) and chronic (CKD), is a well documented consequence of TA-TMA. In general, AKI and CKD remain as significant complications for many HSCT recipients, regardless of whether they develop TA-TMA or not [103]. For example, Rajpal et al. recently compared the incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI in the first 100 days after transplant and 1 year survival across two different time periods, 1990–1999 versus 2000–2009, in 1400 children receiving their first HCT. The risk of needing dialysis remained about 8% during the entire 20 year study period. The risk of death by 1 year among those receiving dialysis in the first 100 days significantly decreased over time, from 89% in 1990–1999 to 77% in 2000–2009. However, these numbers indicate that kidney injury requiring dialysis after HSCT is associated with a very poor prognosis, as <25% of the children needing dialysis survived to 1 year.

In our prospective cohort of children and young adults receiving allogeneic HSCT, acute dialysis was required by 8/90 (8.9%) of the subjects during the first year after transplant, similar to observed by Rajpal et al. [4,104] While the risk of needing dialysis was higher among the subjects developing TA-TMA (5/39, 12.8%) compared to those without TA-TMA (3/51, 5.9%), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.29). Nevertheless, the prognosis following a diagnosis of TA-TMA is poor. Specifically, the subjects in our cohort developing TA-TMA were statistically more likely to need more anti-hypertensive medications to control their blood pressure, require admission to the intensive care unit, develop respiratory failure, or have significant gastrointestinal bleeding within the first year after transplant.

TA-TMA also increases the risk for later CKD after HSCT. In a retrospective study of 100 adult allogeneic HCT recipients, those diagnosed with TA-TMA were 4.3 times more likely to develop CKD and 9 times more likely to have hypertension compared to those without TA-TMA. In patients surviving acute TA-TMA, kidney function was 40% of normal 2 years post-HSCT [12]. Hale et al. observed 10% prevalence of TA-TMA among 293 pediatric allogeneic HSCT recipients and found that kidney function decreased by 65% following a diagnosis of TA-TMA [57]. Furthermore, half of those developing TA-TMA required antihypertensive medication for at least 6 months after transplant.

The reported mortality rate in patients with TA-TMA is often very high, although it remains difficult to determine if TA-TMA was the exact cause of death or an association with overall clinical severity [1]. In our prospective cohort, we observed that subjects with TA-TMA were almost 5 times more likely to die during the first year after transplant compared to those without TA-TMA. Non-relapse mortality at 1 year after-transplantation was 43.6% in patients with TA-TMA versus 7.8% in those without (p < 0.0001) [4]. Other recent reports have supported that TA-TMA may be associated with an increased risk of death. In their analysis of 102 allogeneic recipients (8 of whom developed TA-TMA), Labrador et al. found that TA-TMA was associated with significantly worse survival at 6 and 15 months after HSCT. However, in the final multivariate model, TA-TMA was not associated with worse survival, likely because of its strong association with acute GVHD which itself had an adjusted HR of 12.5 (95% CI 4.5–34.5) for death [75]. Among a cohort of 177 HCT recipients, Shayani et al. found that the cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality at 2 years was significantly worse in those developing TA-TMA (33.3%) compared to those who did not (12.3%). In their multivariable model adjusted for conditioning and acute GVHD, TA-TMA was independently associated with worse survival with an adjusted hazard ratio for non-relapse mortality of 2.8 (95% CI 1.3–5.9) [76].

Finally, Arai et al. reviewed 90 allogeneic recipients who survived at least 28 days at their institution. Eleven patients were diagnosed with TA-TMA a median of 42 days after transplant. At 1-year, overall survival was significantly worse in the 11 subjects diagnosed with TA-TMA (31.2%) compared to those who did not develop TA-TMA (69.8%). Additionally, those diagnosed with TA-TMA also had significantly worse non-relapse mortality, 39% versus 9% compared to those without TA-TMA [105]. In patients with TA-TMA and multi-organ involvement mortality reaches >90%. Patients with pulmonary TA-TMA often die from progressive PH and patients with iTMA often succumb to uncontrollable GI bleeding.

7. Treatment

TA-TMA management can be supportive and also disease targeted. First-line therapy consists of supportive measures that may include withdrawal or minimization of potential triggering agents (i.e., calcineurin inhibitors), treatment of co-existing conditions such as infections and GVHD that may promote TA-TMA, and aggressive hypertension management [22]. Even though cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus have been implicated as risk factors for TA-TMA, there is no solid evidence supporting the discontinuation or dose reduction of these medications, especially given the risk of a potential flare of GVHD. In a large retrospective study evaluating factors influencing the development of TA-TMA published by Uderzo et al., cyclosporine withdrawal was a significant factor only in the univariate analysis, but this observation was not supported in the multivariate analysis [73]. Very often these medications are stopped in patients with TA-TMA due to AKI or severe hypertension, most notably in patients presenting with PRES. Therapies that control GVHD, like cyclosporine and steroids, have been shown to worsen TA-TMA [11]. Additionally, many antiviral medications are nephrotoxic and can substantially contribute to continued deterioration of renal function. Given the lack of conclusive data, we support that all adjunctive therapies, including GVHD prophylaxis and treatment, should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis in transplant recipients presenting with TA-TMA and the risks and benefits carefully considered for each patient.

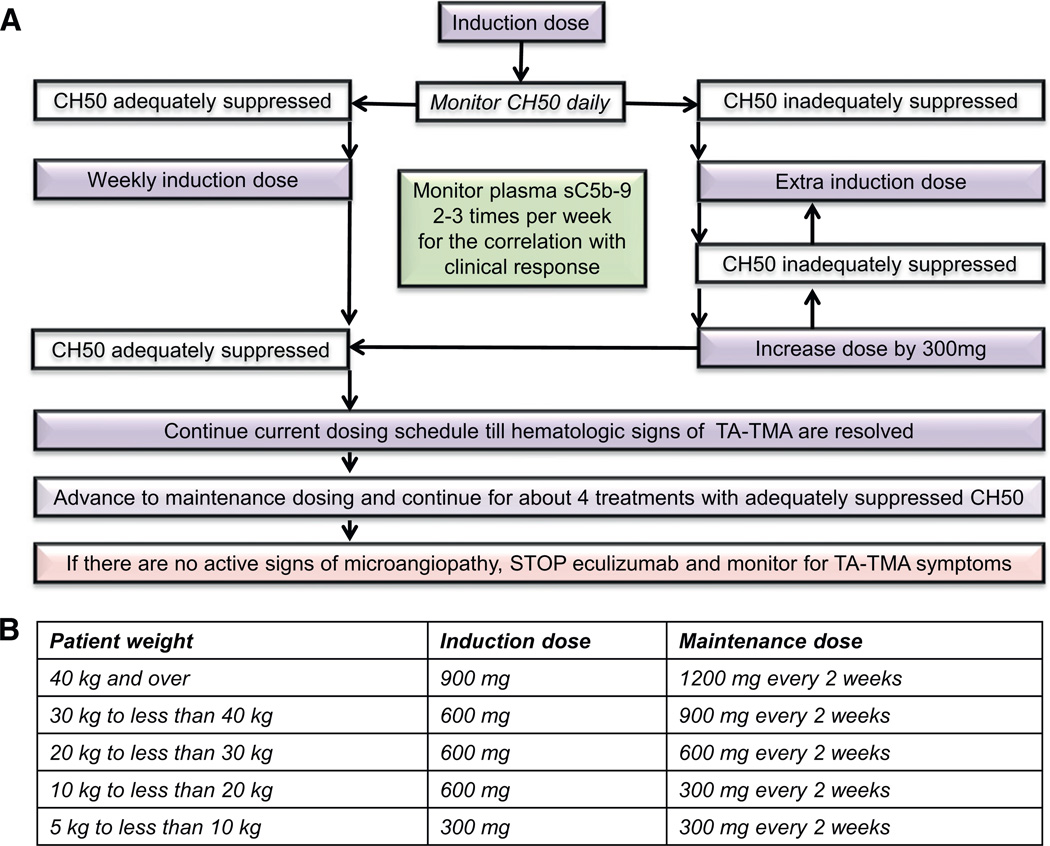

The most promising targeted therapy to date for HSCT-associated TMA is complement blockade with eculizumab, but eculizumab therapy itself poses certain challenges such as the reported difficulty of achieving therapeutic levels in critically ill HSCT patients, limited availability in certain countries, and significant cost associated with this therapy [17]. In our pilot study of 6 children treated with eculizumab for multi-visceral TA-TMA, we observed that patients after HSCT required higher doses or more frequent eculizumab infusions than currently recommended to achieve therapeutic drug levels and a clinical response in children with aHUS. Our extended experience in 18 patients (unpublished) treated with eculizumab supports our initial observations for eculizumab dosing and monitoring requirements in the HSCT population. Twelve of 18 patients (67%) with high risk disease had resolution of TA-TMA using the intensified dosing regimen guided by pharmacodynamic monitoring by measuring CH50 and adjusting eculizumab dosing schedule to maintain an adequately suppressed CH50 level. The main two assays used for measuring CH50 are enzyme immunoassay and hemolysis assay. To achieve and to sustain therapeutic eculizumab level >99 µg/mL, CH50 should be less than 10% of the lower limit of normal, corresponding to 0–3 CAE if using a standard enzyme immunoassay or 0–15 CH50 units if the Diamedix hemolytic assay is used (Fig. 6). Patients with C4d deposition in the renal arterioles and without documented complement gene abnormalities or detectable CFH autoantibodies also have a favorable response to eculizumab. It is important to note that treatment time to control TA-TMA in the HSCT population is longer from what it is typically seen in aHUS and at least 4–6 weeks of induction therapy with therapeutic eculizumab levels should be continued before considering a patient a non-responder. Larger, multi-institutional, controlled studies are certainly needed to better evaluate the use of eculizumab in HSCT recipients, but our pilot data support that patients with TA-TMA and high risk features, who historically have very poor outcome, should at least be considered as early candidates for eculizumab, as delaying therapy may prevent patients from achieving the best response and maximizing recovery of organ function [4]. It is recommended to use eculizumab as a monotherapy with pharmacodynamics monitoring and dose adjustments, as shown in Fig. 6. Concurrent use of therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) would remove eculizumab from the blood as well as replenish C5 available for activation, and supplemental doses would be required after each TPE session. Concurrent use of eculizumab and rituximab may affect rituximab activity as this medication in part depends on complement activity.

Fig. 6.

Eculizumab administration and monitoring schema for HSCT patients with TA-TMA. First eculizumab dose for HSCT-associated TA-TMA should be given based on patient’s weight, as listed in the table (B) according to eculizumab package insert. Subsequent doses and administration timing will be adjusted based on CH50 monitoring. CH50 should be monitored each day during eculizumab induction therapy to determine when the next eculizumab dose is needed, since patients with TA-TMA often require eculizumab dosing more often than weekly in the beginning of the therapy to sustain a therapeutic eculizumab level. To maintain therapeutic eculizumab serum level of ≥99 µg/mL, CH50 level needs to remain adequately suppressed each day as follows: CH50 level should be maintained at less than 10% of the lower limit of normal, corresponding to 0–3 CAE if using a standard enzyme immunoassay or 0–15 CH50 units if the Diamedix hemolytic assay is used. Subsequent eculizumab doses need to be given when CH50 level becomes inadequately suppressed (defined as a CH50 level >3 by enzyme immunoassay and >15 by Diamedix hemolytic assay), but no longer than every 7 day intervals. If CH50 level remains inadequately suppressed by dosing less than 7 day intervals, dose should be increased by 300 mg/dose and daily CH50 monitoring should continue. If CH50 level is adequately suppressed for 7 days, then eculizumab induction doses should be given weekly. When steady CH50 suppression is achieved and hematologic TA-TMA parameters and plasma sC5b-9 level normalize (response), eculizumab should be advanced to a maintenance schedule as listed in table (B) based on patient’s weight, as recommended in eculizumab package insert. CH50 level shall be checked at least prior to each eculizumab dose to assure adequate dosing. If TA-TMA remains controlled after about 4 maintenance doses, eculizumab may be discontinued. Patient should be carefully monitored with twice a week LDH, CBC and differential, weekly urinalysis, and twice a week sC5b-9 for 4 weeks after eculizumab therapy is discontinued. Weekly CH50 level should be checked until it returns to normal. Anti-meningococcal prophylaxis should be provided from the start of the therapy until about 8 weeks after stopping eculizumab.

In contrast to patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and aHUS who must often receive life-long therapy with eculizumab, all HSCT patients reported so far who responded to eculizumab were able to discontinue therapy after TA-TMA was controlled without disease relapses. This might be explained that TA-TMA after HSCT may occur as a result of tissue injury from chemotherapy, infection and temporary immune dysregulation with or without a genetic predisposition, resulting in classical or alternative complement dysregulation that can be cured by terminal complement blockade using eculizumab.

Another potential treatment for TA-TMA, TPE, has a benefit that remains debatable due to variable outcome measurements in retrospective reviews and lack of controlled prospective trials. Blood and bone marrow transplant (BMT) consensus guidelines on TA-TMA have reported poor responses and high mortality rates in patients treated with TPE from 1991 to 2003 with median response rate of 36.5% (range, 0%–80%) with an associated mortality of 80% (range, 44%–100%) likely due to the use of TPE in the most severe TMA cases. More current literature (2003–2011) reported better median response rate of 59% (range, 27%–80%), again in uncontrolled, heterogeneous populations [22]. To date, only one prospective trial has assessed the therapeutic benefit of TPE in TA-TMA. Worel and coworkers reported responses of 64% (7/11) in patients diagnosed with TA-TMA who were treated with immediate withdrawal of cyclosporine and initiation of TPE [58]. Our group observed that TPE was more beneficial in patients who received this therapy early after TA-TMA diagnosis [106]. Even though microangiopathy resolved in 90% of the patients receiving TPE in our cohort, only 50% of patients starting TPE as early as 4–17 days after TA-TMA diagnosis fully recovered renal function and survived.

Although TPE for the treatment of TA-TMA has been discouraged in many reports, TPE can be a suitable therapeutic option in selected cases. TPE can be used in HSCT patients with documented Factor H autoantibodies in conjunction with rituximab as antibody depleting therapy. It can also considered as initial therapy in very catabolic patients, where it may be very challenging to achieve therapeutic eculizumab levels or in those when other therapy options for TA-TMA are not available. If initiated promptly, TPE should be performed as a daily procedure using a single-volume plasma exchange and continued until resolution of microangiopathy and then tapered to every other day for approximately 2 weeks, twice a week for a week, and then discontinued with very close monitoring of TMA markers as previously described [106]. It is important to note that it usually takes 2–3 weeks of daily TPE sessions to resolve TA-TMA after HSCT before initiating the taper, in contrast to only 5 days of therapy in patients with aHUS, and TPE should not be discontinued prematurely in HSCT patients as it may result in a TA-TMA flare.

The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab has been reported as successful TA-TMA therapy in selected cases where it has been used as a monotherapy or in combination with TPE or defibrotide [107–110]. Of the 15 reported cases in the literature, 12 showed a positive response to rituximab [108,111–113]. The exact mechanism of action of rituximab in TA-TMA is not known. Reports of benefit in patients with C4d deposition in the kidney arterioles or complement Factor H autoantibodies after HSCT suggest possible effects of antibody depletion and immune regulation [78,110,111]. If rituximab (375 mg/m2/dose intravenous weekly) is used in conjunction with TPE, it has to be administered immediately after the daily TPE procedure to allow for maximum efficacy before the next plasma exchange session.

Defibrotide, a polydeoxyribonucleotide salt, has been shown to protect against endothelial damage by inhibiting TNFα-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro and has also demonstrated profibrinolytic, anti-thrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and thrombolytic activity [114–117]. Defibrotide has been used to treat hepatic VOD with a reported 30–60% complete response rate [112]. In addition, defibrotide exhibits protective properties to the endothelium that has been potentially damaged by cyclosporine, tacrolimus and tacrolimus combined with sirolimus, and defibrotide has been shown to prevent acute GVHD grades 2 to 4 in HSCT patients receiving prophylaxis for VOD [118,119]. Since both VOD and TA-TMA are disorders resulting from endothelial injury, defibrotide has also been used in the treatment of TA-TMA as mono-therapy or in combination with other agents. The most experience in using defibrotide for TA-TMA is reported by investigators in Europe. Two Italian multi-center retrospective studies examined 551 HSCT patients using strict published criteria for the diagnosis of TA-TMA. TA-TMA was observed in 76 (13.8%) of all patients receiving HSCT. These studies reported a 55% response rate with defibrotide (as mono-therapy or/and combination with other therapies) in patients affected by grade 3–4 TA-TMA without any major adverse effects documented [73,120,121]. Defibrotide dosing (6.25 mg/kg/dose intravenous every 6 h) for these patients was adopted from that used in VOD therapy. At this time, however, defibrotide is available in the United States only as a research drug for the treatment of VOD. Prospective studies should be carried out to examine defibrotide efficacy and the dosing regimen required in patients with TA-TMA.

8. Future directions

Ongoing efforts should be dedicated to raising awareness about TA-TMA and teaching HSCT providers to recognize and evaluate this transplant complication early in its course. TA-TMA, especially the multi-visceral form, can be easily missed, potentially contributing to the dismal outcomes of this disease. Novel TA-TMA biomarkers, reflecting predisposition for injury to specific organs, need to be identified in order to aid earlier TA-TMA diagnosis and for the guidance of targeted therapies. Endothelial injury markers first identified in patients with GVHD or VOD should be studied in HSCT recipients developing TA-TMA to better understand tissue injury pathways involved in this complication. Complement gene studies are currently underway and likely will provide specific insight as to the pathogenesis in some patients with TA-TMA after HSCT. It will be important to understand if recipient or donor complement system genotypes contribute to the pathogenesis of TA-TMA. In some patients TA-TMA likely results as direct tissue damage and an additional mechanism of endothelial injury by factors such as specific viruses or chemotherapeutic agents will need to be examined. With the increasing body of evidence that the complement system is dysregulated in the majority of patients with TA-TMA, especially with severe disease, complement blockade should be examined in well-designed clinical trials. Eculizumab has been shown to be effective even in patients with multi-visceral high risk disease if started early and dosed appropriately. Complement blockade in HSCT patients will likely be required as only a temporary measure to resolve acute TA-TMA and will therefore not have the down side of requiring lifelong complement blockade and the associated immunosuppression required in such patients as those with PNH or aHUS. Risk stratification can identify patients who may most benefit this therapy, but should be validated in larger, multi-center cohorts. Other novel complement-targeting agents should be investigated as potential therapeutic options for TA-TMA to reduce or even eliminate cost-limiting factors currently relevant to eculizumab therapy.

Practice points.

TA-TMA is multi-visceral disease resulting from microvascular endothelial injury in various organs.

The kidney is most often affected, but pulmonary, gastrointestinal and CNS involvement of TA-TMA should be considered and evaluated.

TA-TMA should be suspected if an HSCT recipient has an acute rise in LDH along with proteinuria, hypertension and schistocytes in the blood.

Complement system dysregulation plays an important role in the severity of TA-TMA.

Patients with proteinuria of ≥30 mg/dL and activated terminal complement measured by elevated plasma sC5b-9 levels should be considered for prompt therapy with eculizumab due to high risk disease and poor outcomes.

Clinical interventions should be considered early in the disease course to increase success controlling and reverting TA-TMA.

Research agenda.

Continue to refine the diagnostic and risk criteria for TA-TMA in larger, multi-center studies

Generate further novel insights into the pathogenesis of TA-TMA in patients in whom complement is not involved

Further study TA-TMA as a multi-visceral disease with organ-specific differential diagnoses

Conduct rigorous trials testing novel therapies for TA-TMA and identification of patients who would most benefit from early interventions

Determine the genetic and non-genetic triggers for activation of complement in TA-TMA

Acknowledgments

SJ research is supported by NIH P50DK096418 grant (Pediatric Center of Excellence in Nephrology: Critical Translational Studies in Pediatric Nephrology; Proteomics for early diagnosis of TA-TMA) and unrestricted research grant from Alexion Pharmaceuticals for complement genes in TA-TMA. BLL has a New Investigator Award from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Funding source

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

BPD serves on the speaker’s bureau and as a consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals. SJ and BLL are co-inventors of a patent application: “Compositions and Methods for Treatment of HSCT-Associated Thrombotic Microangiopathy” (application number PCT/US2014/055922). CED, MCM,JE, SMD,JG have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.George JN, Li X, McMinn JR, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, Selby GB. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome following allogeneic HPC transplantation: a diagnostic dilemma. Transfusion. 2004;44:294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kersting S, Koomans HA, Hene RJ, Verdonck LF. Acute renal failure after allogeneic myeloablative stem cell transplantation: retrospective analysis of incidence, risk factors and survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:359–365. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh CR, McSweeney P, Schrier RW. Acute renal failure independently predicts mortality after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1999–2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jodele S, Davies SM, Lane A, Khoury J, Dandoy C, Goebel J, et al. Refined diagnostic and risk criteria for HSCT-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a prospective study in children and young adults. Blood. 2014;124:645–653. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-564997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keir L, Coward RJ. Advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:523–533. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1637-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters AM, Licht C. aHUS caused by complement dysregulation: new therapies on the horizon. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:41–57. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1556-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai HM. Untying the knot of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Med. 2013;126:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jodele S, Licht C, Goebel J, Dixon BP, Zhang K, Sivakumaran TA, et al. Abnormalities in the alternative pathway of complement in children with hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood. 2013;122:2003–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jodele S, Hirsch R, Laskin B, Davies S, Witte D, Chima R. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in pediatric patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner D, Dandoy C, Hirsch R, Laskin B, Davies SM, Jodele S. Pericardial effusion in pediatric SCT recipients with thrombotic microangiopathy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:862–863. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inamoto Y, Ito M, Suzuki R, Nishida T, Iida H, Kohno A, et al. Clinicopathological manifestations and treatment of intestinal transplant-associated microangiopathy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:43–49. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glezerman IG, Jhaveri KD, Watson TH, Edwards AM, Papadopoulos EB, Young JW, et al. Chronic kidney disease, thrombotic microangiopathy, and hypertension following T cell-depleted hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmeister PA, Hingorani SR, Storer BE, Baker KS, Sanders JE. Hypertension in long-term survivors of pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laskin BL, Nehus E, Goebel J, Khoury JC, Davies SM, Jodele S. Cystatin C-estimated glomerular filtration rate in pediatric autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1745–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laskin BL, Goebel J, Davies SM, Khoury JC, Bleesing JJ, Mehta PA, et al. Early clinical indicators of transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in pediatric neuroblastoma patients undergoing auto-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:682–689. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz GJ, Furth SL. Glomerular filtration rate measurement and estimation in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:1839–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jodele S, Fukuda T, Vinks A, Mizuno K, Laskin BL, Goebel J, et al. Eculizumab therapy in children with severe hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;20:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.12.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nehus EJ, Laskin BL, Kathman TI, Bissler JJ. Performance of cystatin C-based equations in a pediatric cohort at high risk of kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hingorani S, Gooley T, Pao E, Sandmaier B, McDonald G. Urinary cytokines after HCT: evidence for renal inflammation in the pathogenesis of proteinuria and kidney disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:403–409. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hingorani SR, Seidel K, Lindner A, Aneja T, Schoch G, McDonald G. Albuminuria in hematopoietic cell transplantation patients: prevalence, clinical associations, and impact on survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laskin BL, Goebel J, Davies SM, Jodele S. Small vessels, big trouble in the kidneys and beyond: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood. 2011;118:1452–1462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-321315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin JE, Geller DS. Glucocorticoid-induced hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:1059–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1928-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moulder JE, Cohen EP, Fish BL. Captopril and losartan for mitigation of renal injury caused by single-dose total-body irradiation. Radiat Res. 2011;175:29–36. doi: 10.1667/RR2400.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hingorani S. Chronic kidney disease after liver, cardiac, lung, heart-lung, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0785-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haines HL, Laskin BL, Goebel J, Davies SM, Yin HJ, Lawrence J, et al. Blood, and not urine, BK viral load predicts renal outcome in children with hemorrhagic cystitis following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1512–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell PH, Swanson K, Josephson MA, Artz AS, Parsad SD, Ramaprasad C, et al. BK virus infection is associated with hematuria and renal impairment in recipients of allogeneic hematopoetic stem cell transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(9):1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.04.016. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laskin BL, Maisel J, Goebel J, Yin HJ, Luo G, Khoury JC, et al. Renal arteriolar C4d deposition: a novel characteristic of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Transplantation. 2013;96:217–223. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829807aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dandoy CE, Hirsch R, Chima R, Davies SM, Jodele S. Pulmonary hypertension after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1546–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houtchens J, Martin D, Klinger JR. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:845864. doi: 10.1155/2011/845864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkowska-Ptasinska A, Sulikowska-Rowinska A, Pazik J, Komuda-Leszek E, Durlik M. Thrombotic nephropathy and pulmonary hypertension following autologous bone marrow transplantation in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: case report. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:295–296. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabinovitch M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4306–4013. doi: 10.1172/JCI60658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dandoy C, Davies SM, Hirsch R, Chima RS, Paff Z, Cash M, et al. Abnormal echocardiography seven days after stem cell transplant may be an early indicator of thrombotic microangiopathy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milan A, Magnino C, Veglio F. Echocardiographic indexes for the non-invasive evaluation of pulmonary hemodynamics. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:225–239. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.01.003. [quiz 332-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery JL, Barbera JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2493–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aljitawi OS, Rodriguez L, Madan R, Ganguly S, Abhyankar S, McGuirk JP. Late-onset intestinal perforation in the setting of posttransplantation microangiopathy: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3892–3893. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hewamana S, Austen B, Murray J, Johnson S, Wilson K. Intestinal perforation secondary to haematopoietic stem cell transplant associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83:277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narimatsu H, Kami M, Hara S, Matsumura T, Miyakoshi S, Kusumi E, et al. Intestinal thrombotic microangiopathy following reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:517–523. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]