Abstract

Objective:

In this study we aimed to define clinical, radiologic and pathological specialties of patients who applied to General Surgery Department of Atatürk University Medical Faculty with granulomatous mastitis and show medical and surgical treatment results. With the help of this study we will be able to make our own clinical algorithm for diagnosis and treatment.

Materials and Methods:

We searched retrospectively addresses, phone numbers and clinical files of 93 patients whom diagnosed granulomatous mastitis between a decade of January 2001 – December 2010. We noted demographic specialties, ages, gender, medical family history, main complaints, physical findings, radiological and laboratory findings, medical treatments, postoperative complications and surgical procedures if they were operated; morbidity, recurrence and success ratios, complications after treatment for patients discussed above.

Results:

In this study we evaluated 93 patients, 91 females and 2 males, with granulomatous mastitis retrospectively who applied to General Surgery Department of Atatürk University Medical Faculty between January 2001 and December 2010. Mean age was 34.4 years. The diagnosis was confirmed by histopathologic examination of the lesions. Seventy three patients had idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis and 20 patients had specific granulomatous mastitis IGM (18 tuberculosis mastitis, 1 alveolar echinococcosis and 1 silk reaction). All the patients had surgical debridement or antibiotic, and anti-inflammatory treatment with results bad clinical response before applied our clinic.

Conclusion:

Empiric antibiotic therapy and drainage of the breast lesions are not enough for complete remission of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. The lesion must be excised completely. In selected patients, corticosteroid therapy can be useful. In the patients with tuberculous mastitis, abscess drainage and antituberculous therapy can be useful, but wide excision must be chosen for the patients with recurrent disease.

Keywords: Mastitis, granulomatous mastitis, tuberculosis mastitis

Özet

Amaç:

Atatürk Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi genel cerrahi kliniğine başvuran ve granülomatöz mastit tanısı alan hastaların klinik, patolojik ve radyolojik özelliklerini belirlemek ve bu hastaların medikal ve cerrahi tedavi sonuçlarını bildirmektir. Bu sayede tanı yöntemleri ve tedavi algoritması üzerinde kliniğimiz deneyimine göre hareket etmek mümkün olacaktır.

Gereç ve Yöntem:

Ocak 2001 - Aralık 2010 arasındaki 10 yıllık dönemde histopatolojik olarak granülomatöz mastit tanısı alan 93 olgunun hastane dosyalarına, adres ve telefon kayıtlarına ulaşıldı, dosyaları retrospektif olarak incelendi. Olguların demografik özellikleri yaşları, cinsiyeti, aile hikayesi, şikayetleri, fizik muayene bulguları, radyolojik ve laboratuvar bulguları, medikal tedavisi, ameliyat edilmiş ise ameliyatın şekli, ameliyat sonrası komplikasyonlar, tedavi sonrası morbidite ve nüks oranları not edildi, başarı oranları ve komplikasyonları çıkarıldı.

Bulgular:

Çalışma yaşları 20 ile 73 arasında değişmekte olan toplam 93 olgu üzerinde yapıldı. Hastaların 91’i kadın 2’si erkekti. Ortalama yaş 34,4 idi. Hastaların tanısı histopatolojik inceleme ile kondu. İdiopatik granülomatöz mastit tanısı alan 73, tüberküloz mastit tanısı alan 18, Ekinokokus Alveolaris tanısı alan 1 ve yabancı cisim reaksiyonu olan 1 hasta çalışmaya alındı. Tüm olguların ilk müracaatlarında antibiyotik, antiinflamatuar tedavi veya apse drenajı sonucu tedaviye cevap alınamadığı saptandı. Çoğu hasta dış merkezli apse drenajı sonrası nüks şikayeti ile kliniğimize sevk edilmişti.

Sonuç:

İdiopatik granülomatöz mastitin tedavisinde apse drenajı ve antibiyotik tedavisi tek başına yeterli değildir. Hastalığın kesin tedavisi için lezyonun geniş olarak veya total eksizyonu gerekmektedir. Seçilmiş hastalarda kortikosteroid tedavisi etkili olmakla birlikte apse, cilde fistül, inatçı yara enfeksiyonlarında cerrahi tedavi yine ilk seçenek olarak düşünülmelidir. Tüberküloz mastit tanısı konan hastalara apse drenajı ve antitüberküloz tedavisi etkili olmakla birlikte nüks eden ve kronikleşen vakalarda cerrahi olarak total eksisyon seçilmelidir.

Introduction

Granulomatous mastitis (GM) is a rare benign disease of the breast, first described by Kessler and Wolloch in 1972 [1]. It has two forms: Idiopathic GM (IGM) and specific GM (SGM). Idiopathic GM is defined as GM without any other attributable causes and SGM can be a rare secondary complication of tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, syphilis, corynebacterial infection, foreign body reaction, vasculitis, fungal and parasitic infections, etc. [2–4].

The primary presentation of GM is a firm breast mass, which is tender. The full presentation includes breast masses, tumorous indurations, skin ulcerations, inflammation, local pain, tenderness, galactorrhea, abscesses and fistulae. Many patients have a mass fixed to the skin or underlying structures and retraction of the nipple. In those situations, GM is easily confused with cancer. Therefore, an early and correct diagnosis is very important for an appropriate treatment and not delaying the treatment of cancer. Some patients have hyperaemia, pain and fever and they are regarded as nonspecific infection [5–7].

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is diagnosed with the presence of non-caseified granulomatous inflammation on histological sections. It generally occurs 2–6 years after pregnancy. Usual age range is 17–42 years. The aetiology is unknown; however, autoimmune diseases, such as granulomatous thyroiditis, granulomatous prostatitis, granulomatous orchitis, immune response to local trauma; local irritants; undetected organisms, such as viruses, mycotic, and parasitic infections; hyperprolactinemia; diabetes mellitus; alpha-1 antitrypsin and the use of oral contraceptives are the postulated causes. It occurs unilaterally in 75% of the cases, it is painful in 25% of the cases and axillary lymphadenopathy is present in 15% of the cases [5, 6]. There is not a pathognomonic sign on ultrasonography (USG), mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There is not a definite treatment modality. Surgical wide excision, corticosteroid therapy, colchicine, methotrexate, azathioprine, etc. can be used [8–10].

Specific granulomatous mastitis is generally seen in Asia or Africa. It can be encountered at every age. The most common causes are sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. The breast is affected in less than 1% of sarcoidosis patients. There are granulomas without caseification necrosis and giant cells on histological sections. Corticosteroid therapy is the mainstay of the treatment [2–4].

Breast tuberculosis is account for less than 0.1% of all known breast diseases globally but it comprises up to 3% of treatable breast lesions in developing countries. It may have different clinical presentations. A breast mass with an associated sinus tract is most common presentation and accounts for 39% of the cases. The other presentations include an isolated breast mass in 23%, a sinus tract without a breast mass in 12%, and tender breast nodularity in 23%. In affected individuals, 40–70% has been reported to have an associated axillary lymphadenopathy. Histologically, the most common findings include caseous necrosis, granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells of Langhan’s type. Diagnosis rests on the clinical suspicion and the histopathological findings of the breast lesion. The mainstay of the treatment is a 6–12 month-duration antituberculous chemotherapy [11–13].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the clinical, pathological and radiological features of the patients with GM and to establish the diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities.

Materials and Methods

In this study, we evaluated 93 patients with histologically proven granulomatous mastitis retrospectively who applied to General Surgery Department of Atatürk University Medical Faculty between January 2001 and December 2010. Hospital file records were evaluated and the patients were called for control. The patients who came for control of the disease were asked to have an USG and mammography.

The diagnosis of GM was based on open biopsy, and the pus was sent for microscopy, culture and antibiotic sensitivity. Age, gender, history, symptoms, physical examination signs, radiologic and laboratory data, medical treatment, type of operation, morbidity and recurrence were evaluated.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Atatürk University Medical Faculty ethics committee.

Results

The study included 93 patients (20–73 years, mean age 34.4 years) who were treated for GM between 01.01.2001 and 31.12.2010. Seventy-three patients with IGM and twenty patients with SGM (18 tuberculous mastitis (TM), 1 alveolar echinococcosis and 1 silk reaction) were evaluated. Two of the patients were males (1 with IGM and 1 with TM) and 91 were females. Follow-up period changed between 4 months and 10 years, mean 36±9.69 months.

The demographic properties of the patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic properties of the patients

| Aetiology | Number of cases | Male | Female | Mean age | Right breast | Left breast | Bilaterality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis | 73 | 1 | 72 | 33.3 | 33 | 35 | 5 |

| 2. Tuberculous mastitis | 18 | 1 | 17 | 38.4 | 5 | 12 | 1 |

| 3. Echinococcal disease | 1 | - | 1 | 57 | 1 | - | - |

| 4. Foreign body reaction | 1 | - | 1 | 26 | 1 | - | - |

All of the patients had a painful breast mass in one or two breast at the beginning of the illness. As the illness progressed, some of the patients began to complain of ulcerations, indurations, abscesses and fistula formations (Figure 1). Twelve (13%) patients had a palpable axillary mass. Two patients with IGM were taking an antipsychotic drug, risperidone.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance of a patient with IGM including skin ulcerations, abscesses and fistulae.

All patients had USG, and some of them had mammography (Mammomat Inspiration; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and MRI (Magnetom, Skyra; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). USG showed ill-defined, hypoechoic, heterogeneous lesions in most of the patients. Besides, USG showed dilated ducts with thick debris, or cystic lesions with debris, or severe inflammatory changes.

While the mammographic views showed heterogeneous masses with spiculations in some patients, ill-defined increased radio opacity was the unique finding in most patients.

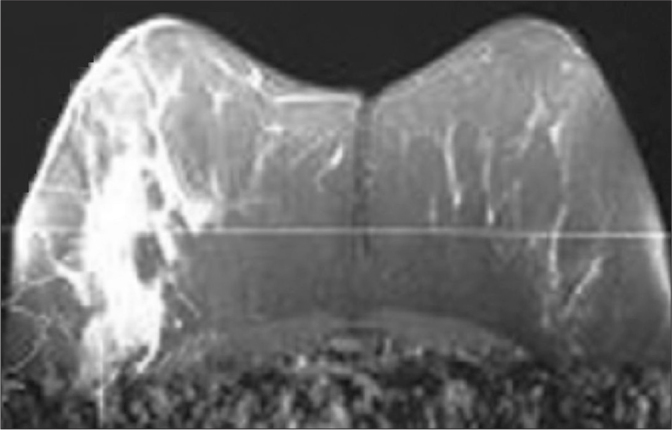

MRI findings were not pathognomonic for GM. An ill-defined mass with Type III contrast line was the most common finding in most of the patients. Imagination findings are seen in Figures 2–6.

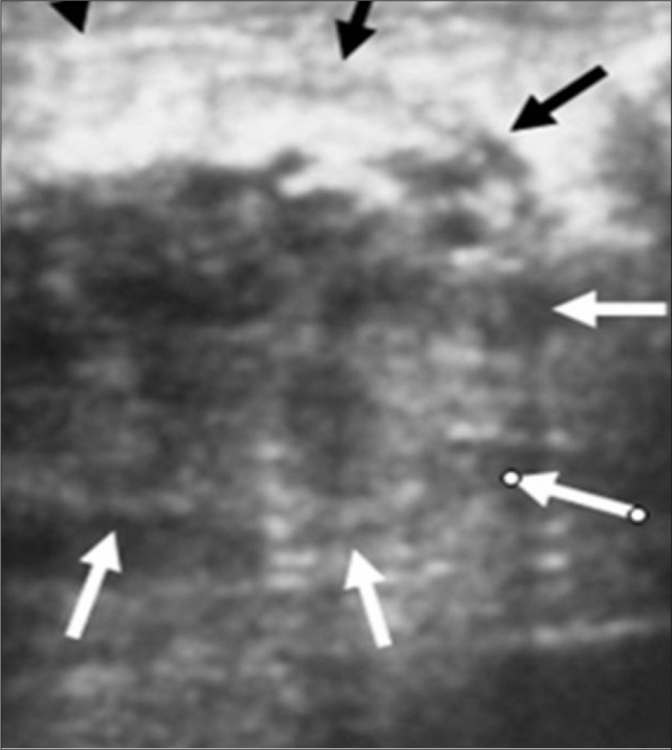

Figure 2.

An ill-defined, hypoechoic, heterogeneous 6 cm lesion is seen in the upper-inner quadrant of the left breast on ultrasonography in a patient with TM.

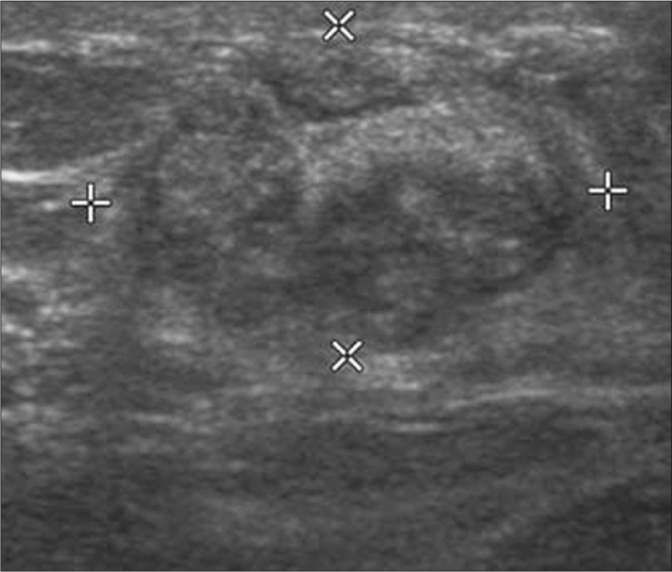

Figure 3.

A hypoechoic, heterogeneous mass is seen in the left breast on ultrasonography in a patient with IGM.

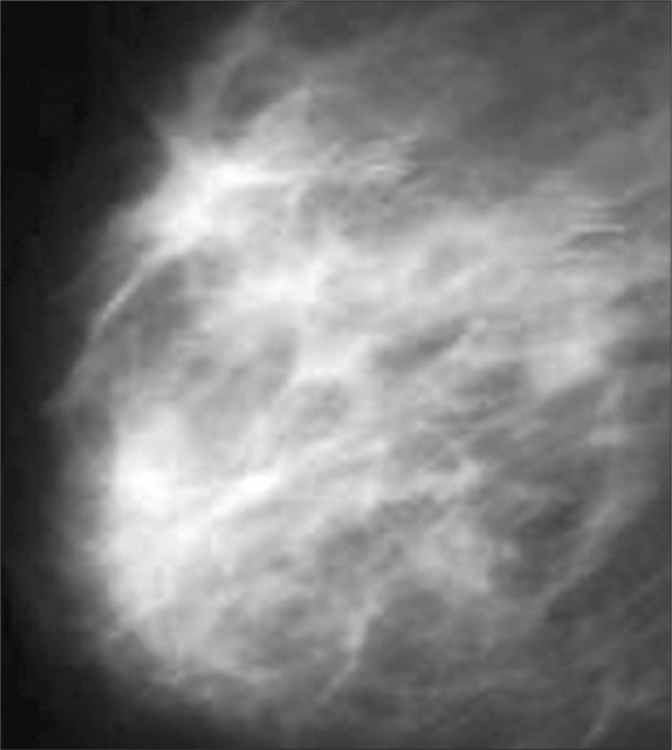

Figure 4.

Mediolateral oblique mammographic (Mammomat Inspiration, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) views showing a 3×4 cm heterogeneous mass with spiculations in a patient with IGM.

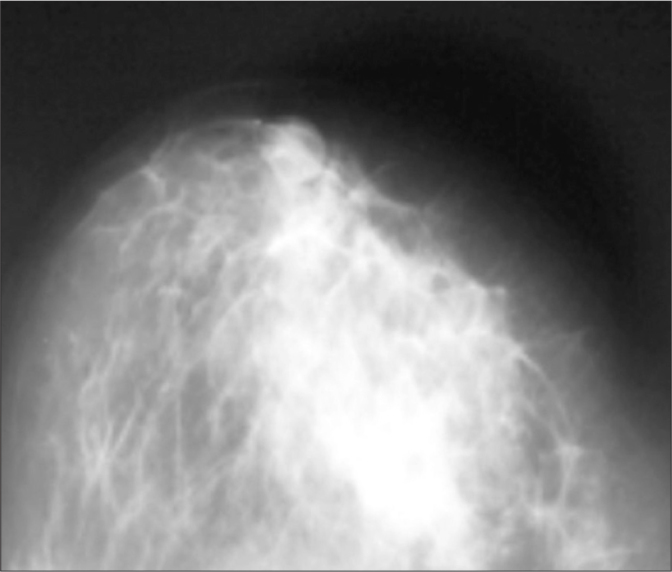

Figure 5.

Craniocaudal mammographic views showing a 3×3 cm ill-defined increased radio opacity within the inferior-medial quadrant of the left breast in a patient with IGM.

Figure 6.

An ill-defined mass with Type III contrast line on MRI (Magnetom, Skyra; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) in a patient with IGM.

All patients had either prescribed empiric antibiotic therapy or undergone drainage of the breast lesions on several occasions, without relief of their symptoms.

In ten patients, USG and mammography findings were suspicious for malignancy. These patients had a core needle biopsy before the operation, and the malignancy was excluded.

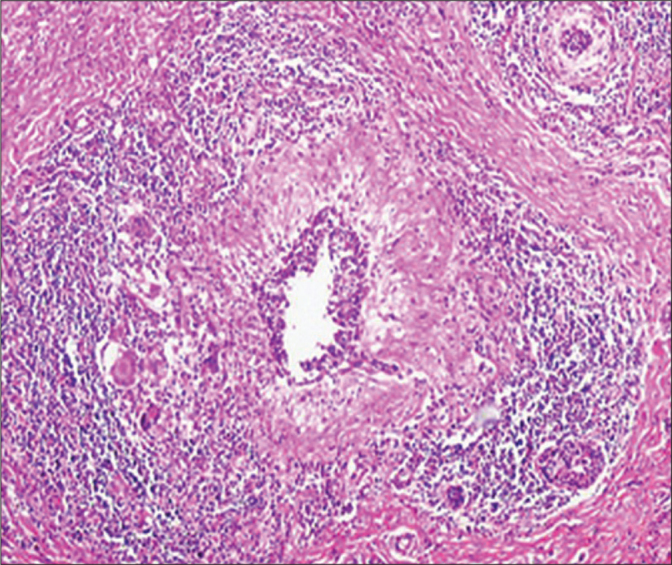

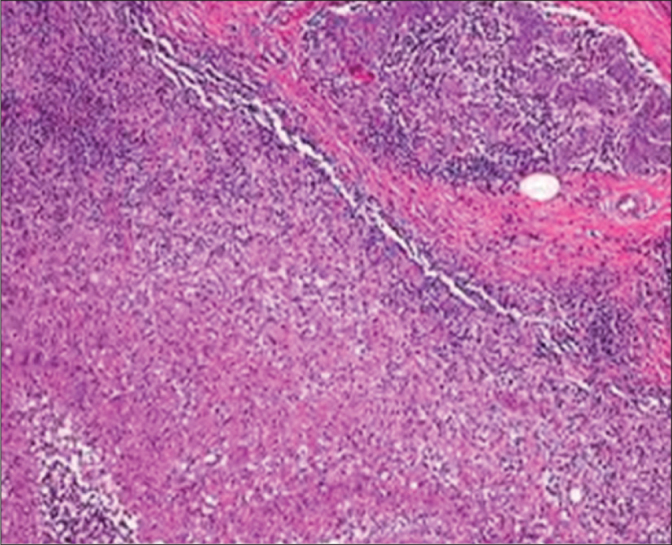

Histopathological examination proved the diagnosis in all patients. Histopathological figures of two patients are seen in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7.

The histopathological examination of the specimen revealed granulomas with central caseation necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, Langhans’ giant cells and intense lymphocytic infiltration at the periphery of the granulomas in a patient with TM (H&E, ×40).

Figure 8.

The histopathological examination of the specimen revealed granulomas with histiocytes, Langhans’ giant cells, plasma cells lymphocytes in a patient with IGM (H&E, ×40).

In our study, no microorganisms were demonstrated by Gram stain, and also bacterial, fungal and tuberculosis cultures were negative.

One of 73 patients with IGM was male. Five female patients had bilateral mastitis. Thirty-seven patients underwent drainage of the breast lesion and a biopsy was taken from the wall of the abscess cavity. Symptoms persisted in 9 of 37 patients. Therefore, 4 of them had wide excision, 3 of these patients had a relief of the symptoms and 1 patient had a drainage of the abscess again. 5 of these 9 patients had corticosteroid therapy, 2 of them had a relief of the symptoms, 1 had a wide excision, 2 patients refused a surgical procedure and have a persistent disease.

Thirty-six of 73 patients with IGM had wide excision. Thirty-two of 36 patients who had wide excision had a relief of the symptoms. Four patients necessitated a drainage of the abscess again, 3 of them had a relief of the symptoms.

In the tuberculous mastitis group, one patient was male. One female patient had a bilateral disease. Two female patients had associated pulmonary tuberculosis, and one female patient had an associated axillary lymphadenopathy. Clinically, all of these patients had tender, erythematous, firm breast masses with or without sinus formation. The results of routine laboratory exam, including hematologic and biochemical parameters, were unremarkable. Tuberculin skin test was positive in all patients. Histologically these patients had caseous necrosis, granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells of Langhan’s type. In all patients, the surgical specimens were proved negative for acid-fast bacilli on staining, as well as negative on culture (Lowenstein Jensen). Twelve patients had a relief of the symptoms after drainage of the abscess and antituberculous chemotherapy. Six patients necessitated wide excision. Antituberculous chemotherapy included ethambutol 1200 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, rifampicin 450 mg and pyrazinamide 1500 mg daily for two months, and was followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for an additional four months.

One female patient had been proven to have alveolar echinococcosis in the histologic examination of the lumpectomy specimen. She died due to brain metastasis.

One female patient had undergone lumpectomy 1 year ago and GM developed due to foreign body reaction. The patient had a wide excision and it was seen that the reaction was due to silk.

Discussion

Granulomatous mastitis is a rare benign disease of breast, however the diagnosis and treatment of the disease is not easy in every case [1, 3, 5].

The longest study in the literature belongs to Al-Khaffaf et al. [14] with 133 patients diagnosed and treated in 25 years. Hee et al. [15] reviewed 58 patients with IGM and 10 patients with TM in a 10-year period. Peyvandi et al. [16] reported 54 patients, and Kok and Telisinghe [17] reported 43 patients with GM. There are similar papers from Turkey reporting the patients with GM. However, the number of the patients is lower than reported in our series. For example, Erözgen et al. [18] reported 33 patients with GM, 25 with IGM and 8 with TM. Akyıldız et al. [19] reported 30 patients, Aksoy et al. [20] reported 19 patients and Gürleyik et al. [21] reported 19 patients with GM.

Granulomatous mastitis has two forms: IGM and SGM. SGM can be a rare secondary complication of tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, syphilis, corynebacterial infection, foreign body reaction, vasculitis, fungal and parasitic infections, etc. [2–4]. In our series, there were 18 tuberculous mastitis cases, 1 alveolar echinococcosis and 1 silk reaction case. The GM case due to primary alveolar echinococcosis is the first case in the literature.

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is diagnosed with the presence of non-caseified granulomatous inflammation on histological sections after the infectious (tuberculosis, fungal infections, etc.) and non-infectious (sarcoidosis, vasculitis, etc.) causes of the granulomatous mastitis have been excluded. Although the aetiology of IGM remains unclear, some factors are claimed to cause the disease including autoimmune diseases such as granulomatous thyroiditis, granulomatous prostatitis, granulomatous orchitis, immune response to local trauma, local irritants, undetected organisms such as viruses, mycotic, and parasitic infections, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes mellitus, alpha-1 antitrypsin and the use of oral contraceptives [5, 6].

Al-Khaffaf et al. [14] did not find a relationship between GM and smoking. However, they reported that the patients with GM had a high BMI.

In our study, 2 patients were taking an antipsychotic drug, risperidone. This drug is known to result in hyperprolactinemia. High levels of prolactinemia in the cases of IGM on antidepressant therapy, suggests a possible side effect of selective inhibitors of serotonin reuptake (SSRI). Also, a functional crosstalk between serotonin and dopamine receptors is noteworthy [22–24]. Bellavia et al. [22] reported that the cases of IGM related to the chronic use of antidepressant therapy should be treated with non-surgical therapeutic approaches, where possible, a conservative approach based on administration of an anti-inflammatory therapy is favoured. Prolactin levels may have an important role in the cases with recurrence. In case of a high prolactin level and recurrence, medical treatment to control prolactin levels may be the best choice of treatment.

Erozgen et al. [18] reported that the most common complaint was a mass in 27 patients and pain in 17 patients. All of our patients had a painful localized mass in one or two breast at the beginning of the illness. When the illness became chronic, some of them began to complain of abscess and fistulisation of the abscess to the skin. In our series, 13% of the patients had a palpable axillary mass. It has been reported that up to 25% of cases can involve both breasts [1, 3, 5]. In our series, the disease was commonly unilateral (87 patients unilateral, 6 patients bilateral), and the right and left breasts were affected equally (40 cases in the right breast and 47 cases in the left breast).

Idiopathic GM is more frequent in premenopausal women, but can be seen in different ages, such as an 11-year-old girl [5, 25] as well as the cases in the 6th, 7th and 8th decades [25, 26]. The majority of our patients were of childbearing age, with a mean age of 34.4 years, and most of them were multiparous and had breastfed their children.

There is not a pathognomonic sign on USG, Mammography and MRI. There can be an irregular tubular hypoechoic lesion, a lobulated hypoechoic mass, parenchymal irregularities without a mass, fistulisation to skin or axillary lymphadenopathies on USG.

A focal asymmetric opacity, enhancement of density, diffuse enhancement of fibroglandular mass density, an irregular mass, ellipsoid mass, retraction and heterogeneity of breast parenchyma can be seen on mammography. Cases with micro-calcifications are confused with cancer.

A pathognomonic imagination for GM on MRI has not been reported in the literature [6–9].

In our series, all patients had an USG initially, 30 patients had a mammography and 16 patients had an MRI.

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is not recommended for the diagnosis. A core needle biopsy or open biopsies are encouraged for the exact diagnosis [27].

In our series, the diagnosis of all patients was proven histologically by the examination of open biopsy specimens.

There is no clear clinical consensus regarding the ideal therapeutic management of IGM. Histopathological confirmation, combined with exclusion of malignancy and other causes of granulomatous disease, is of great importance in guiding clinical decision making and preventing inappropriate and unnecessary treatments. Surgical wide excision, steroid therapy, colchicine, methotrexate, azathioprine can be used [8–10]. Oral prednisolone is preferred for corticosteroid therapy. Dosage is 0.8 mg/kg/day. Treatment period is 6 months. However, a 50% recurrence rate has been reported after stopping the therapy [7]. Erozgen et al. [18] gave steroid to 24 of the 25 patients with IGM, and saw only 1 recurrence at the end of 11 month follow up. We gave steroid to 5 patients with IGM for 6 months. Only 2 patients had a complete resolution of the disease. All 5 patients received the medication during 6 months, and no major side effect has been encountered.

Aksoy et al. [20] performed a wide excision in 15 patients and gave steroid therapy to 4 patients. Patients who underwent wide excision had a complete resolution of the disease. No recurrence was seen at the end of the 1-year follow up. However, only 1 patient who received steroid therapy had a complete resolution of the disease.

Asoğlu et al. [28] reported that in persistent and recurrent cases, mastectomy can be advised. Similarly, we performed mastectomy for 2 cases with IGM after the study ended. One of the patients had received steroid therapy and undergone multiple surgical excisions. She was a patient included in our study. The other patient was not in our series. She had underwent multiple surgical procedures in different hospitals. There was a fistulised lesion in her breast. She denied a wide excision. Both of the patients had a complete resolution of the disease after the mastectomy procedures.

Mammary tuberculosis may be primary if there is no other tuberculous focus, or secondary to a pre-existing lesion located elsewhere in the body. It is generally believed that tuberculous infection of the breast is usually secondary to a pre-existing tuberculous focus located elsewhere in the body [13, 15, 29]. Primary tuberculous infection of the breast may occur through skin abrasions or through the milk duct openings on the nipple. Direct extension from contiguous structures like the underlying ribs is another possible mode of infection, as previously reported by Eroğlu et al., [30]. In our study, we found that most of the cases are primary tuberculosis and only two female patients had an associated pulmonary tuberculosis, and 1 female patient had an associated axillary lymphadenopathy. Although mammary tuberculosis is much more common in females, it has been previously reported to occur in males [31]. In our series, one of the patients was male.

The clinical presentation of mammary tuberculosis is variable [11–13]. Constitutional symptoms of tuberculosis (fever, weight loss, night sweats or failing of general health) are infrequently encountered. A breast mass with an associated sinus tract (39%), an isolated breast mass (23%), a sinus tract without a breast mass (12%), and tender breast nodularity (23%) have been reported in the series by Khanna et al. [32]. Associated axillary lymphadenopathy has been reported in 40% to 71% of the affected individuals. An isolated breast mass without an associated sinus tract can commonly mimic the presentation of a breast cancer, since the clinically palpable breast mass is usually firm, ill-defined and irregular, and can be associated with fixation to the skin. This diagnostic dilemma can be further complicated by the presence of an associated axillary adenopathy. However, pain and palpable tenderness is associated far more frequently with a tuberculous mass than with a malignant breast mass, and involvement of the nipple and areola complex is less commonly seen in mammary tuberculosis [11–13, 32].

In our previous paper [13], confusion with that of the diagnosis of a breast cancer could have been entertained since all three patients had a firm, irregular breast mass with varying degrees of fixation to the overlying skin and since the second patient presented with associated axillary lymphadenopathy. Therefore, histopathological evaluation at the time of open surgical biopsy was critical for confirming the diagnosis of mammary tuberculosis and excluding the diagnosis of breast cancer.

Another disease process that must be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of mammary tuberculosis is that of IGM. Idiopathic GM usually occurs in women of reproductive age. In both IGM and TM, there is a usually hard breast lump in the clinical presentation. The accurate diagnosis of IGM versus that of TM is based on the particular histological features of the biopsy specimens. In TM, the most common features include caseous necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, Langhans’ giant cells and granulomas. The presence of predominantly neutrophils in the background, and the lack of caseous necrosis may favour a diagnosis of IGM rather than that of TM [2–4, 27]. In all our cases, the presence of caseous necrosis, in addition to other features mentioned above in the histologic evaluation of biopsy specimens, favoured the diagnosis of TM.

Lastly, any patient presenting with a breast mass that is associated with a draining sinus tract needs to be differentiated from actinomycosis by the absence of sulphur granules in the discharge and by fungal culture [33].

Breast imaging modalities, such as mammography and ultrasound, may be useful adjuvant diagnostic tools in the overall process of diagnosing TM [13, 27, 29]. However, these imaging modalities are by no means reliable in distinguishing TM from that of a breast malignancy [34]. The most common mammographic findings are dense breast parenchyma with or without an associated ill-defined mass-like density and associated skin thickening. In our previously reported series, ultrasound revealed a 5 mm sinus tract connecting the breast lesion to the skin for the first case, 6 cm heterogeneous breast mass and two suspicious axillary lymph nodes for the second case. However, in all three cases, mammography showed increased radio opacity within the breast tissue, which was nonspecific and non-diagnosis [13].

The accurate diagnosis of TM has traditionally relied upon the demonstration of a classical caseous lesion, acid-fast bacilli within such a lesion, and/or the demonstration of epithelioid granulomas, Langhans’ giant cells and lymphocytic aggregates [13, 27, 29]. It has been more recently recognized that an AFB-positive smear is not always sufficient evidence for the definitive mycobacterial diagnosis of tuberculosis. We primarily use staining, smear examination and culture in our mycobacteriology laboratory for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. In our mycobacteriology laboratory, smear and culture positivity were found as 46% and 63%, respectively, as recently published by Saglam et al., [34] from our institution. FNA is generally a reliable diagnostic procedure, particularly if the aspirated material can be examined by the stains for acid-fast bacilli. In our present report, FNA was performed but was not diagnostic for mammary tuberculosis. The accurate diagnosis was only achieved after histopathological evaluation of the open surgical biopsy specimens.

Medical treatment with a four drug regimen of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol forms the basis of TM treatment [13, 27, 29]. Surgical intervention is generally reserved for diagnostic purposes, aspiration/drainage of a residual breast mass (representing a “cold abscess”), excision of a residual mass and excision of a residual sinus tract. In refractory cases of TM causing significant destruction of the breast tissue, simple mastectomy may need to be considered [2–4]. In our series, 12 patients had a complete resolution of the disease after abscess drainage and antituberculous therapy. Six patients necessitated wide excision. Ethambutol 1200 mg, streptomycin 750 mg, rifampicin 450 mg and pyrazinamide 1500 mg were used for antituberculous therapy. The treatment period was 6 months.

Tuberculous mastitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any case of a painful breast mass, mastitis, or breast abscess that appears refractory to conventional therapy. Its recognition and differentiation from that of a breast malignancy is absolutely necessary. Diagnosis rests on clinical suspicion and histopathological findings. Antituberculous chemotherapy, initiated immediately upon diagnosis, forms the mainstay of the treatment for mammary tuberculosis.

In our series, one female patient had been proven to have alveolar echinococcosis in the histologic examination of the lumpectomy specimen. Her liver and other organs were normal. Therefore, we accepted her as a primary alveolar echinococcosis case. She was treated with albendazole (10 mg/kg/day). In a few months, she died due to brain metastasis. This is the unique case in the literature with primary alveolar echinococcosis of the breast. Albayrak et al. [35] presented a case of alveolar echinococcosis in which exophytic growth of an alveolar cyst led to its adhesion to the intra-abdominal and pelvic organs and also to metastasis to the breast. This is the first case of alveolar echinococcosis metastasis to the breast to be reported in the literature.

One female patient had undergone lumpectomy 1 year ago and GM developed due to foreign body reaction. The patient had a wide excision and it was seen that the reaction was due to silk.

In conclusion, empiric antibiotic therapy and drainage of the breast lesions are not enough for complete remission of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. The lesion must be excised completely. In selected patients, corticosteroid therapy can be useful. In the patients with tuberculous mastitis, abscess drainage and antituberculous therapy can be useful, but wide excision must be chosen for the patients with recurrent disease.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Atatürk University Medical Faculty.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was not obtained due to retrospective nature of the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - E. Korkut; Design - E. Korkut; Supervision - M.N.A.; Resources - I.D.S.; Materials - N.G.; Data Collection and/or Processing - E. Karadeniz; Analysis and/or Interpretation - E. Korkut; Literature Search - M.N.A.; Writing Manuscript - E. Korkut; Critical Review - I.D.S.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Kessler E, Wolloch Y. Granulomatous mastitis: a lesion clinically simulating carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1972;58:642–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/58.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diesing D, Axt-Fliedner R, Hornung D, Weiss JM, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Granulomatous mastitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;269:233–6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tse GM, Poon CS, Ramachandram K, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: A clinicopathological review of 26 cases. Pathology. 2004;36:254–7. doi: 10.1080/00313020410001692602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panzacchi R, Gallo C, Fois F, et al. Primary sarcoidosis of the breast: case description and review of the literature. Pathologica. 2010;102:104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, Shatnawi NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: Time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J. 2004;10:318–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heer R, Shrimankar J, Griffith CDM. Granulomatous mastitis can mimic breast cancer on clinical, radiological or cytological examination: a cautionary tale. Breast. 2003;12:283–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(03)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Çakır B, Tunçbilek N, Karakaş HM, Ünlü E, Özyılmaz F. Granulomatous mastitis mimicing breast carcinoma. Breast J. 2002;8:251–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hur SM, Cho DH, Lee SK, et al. Experience of treatment of patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:1–6. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.85.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pistolese CA, Di Trapano R, Girardi V, Costanzo E, Di Poce I, Simonetti G. An unusual case of bilateral granulomatous mastitis. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/694697. 694697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Tymms KE, Buckhingham JM. Methotrexate in the management of granulomatous mastitis. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:247–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2002.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandhi D, Verna P, Sharma S, Dhawan AK. Borderline-lepromatous leprosy manifesting as granulomatous mastitis. Lepr Rev. 2012;83:202–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditmyer H, Craig L. Mycotic mastitis in three dogs due to Blastomyces bermatitidis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:356–8. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akçay MN, Sağlam L, Polat P, Erdoğan F, Albayrak Y, Povoski SP. Mammary tuberculosis-importance of recognition and differentiation from that of a breast malignancy: report of three cases and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Khaffaf B, Knox F, Bundred NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: A 25 year experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hee RNS, Kuk YN, Hyun EY, et al. Differential diagnosis in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis and tuberculous mastitis. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:111–8. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peyvandi LB, Klpfel N, Grant E, Lyengar G. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: Imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR. 2009;193:574–81. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kok KY, Telisinghe PU. Granulomatous mastitis: Presentation, treatment and outcome in 43 patients. Surgeon. 2010;8:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erözgen F, Ersoy YE, Akaydın M, et al. Corticosteroid treatment and timing of surgery in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis confusing with breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;123:447–52. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akyıldız EÜ, Aydoğan F, İlvan Ş, Calay Z. İdiopathic granulomatous mastitis. J Breast Health. 2010;6:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aksoy Ş, Aren A, Karagöz B, et al. Granülomatöz mastit ve cerrahi tedavi. İstanbul Tıp Dergisi. 2010;11:164–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gürleyik G, Aktekin A, Aker F, Karagülle H, Sağlam A. Surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous lobulşar mastitis. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:119–23. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellavia M, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. Granulomatous mastitis during chronic antidepressant therapy: Is it possible a conservative therapeutic approach? J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:371–2. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CH, Hsu CW, Tsoo T, Chou J. Idiopatic granulomatous mastitis associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Csemi G, Szajiki K. Granulomatous lobular mastitis following drug-induced galactorrhea and blunt trauma. Breast J. 1999;5:398–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.1999.97040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Rodiguez JA, Pattullo A. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a mimicking disease in a pregnant woman: a case report. BMC Research Notes. 2013;6:95. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuli R, O’hara BJ, Hines J, Rosenberg AL. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis masquerading as carcinoma of the breast: a case report and review of the literature. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2007;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Jarrah A, Taranikanti V, Lakhtakia R, Al-Jahri A, Sawhney S. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Diagnostic strategy and therapeutic implications in Omani patients. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:241–7. doi: 10.12816/0003229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asoğlu O, Özmen V, Karanlık H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:108–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuervo SI, Bonilla DA, Murcia MI, et al. Tuberculosis of the breast. Biomedica. 2013;33:36–41. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572013000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eroğlu A, Kürkçüoğlu C, Karaoğlanoğlu N, Kaynar H. Breast mass caused by rib tuberculosis abscess. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:324–6. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopala S, Agarwal R. Tuberculous mastitis in men: case report and systematic review. Am J Med. 2008;121:539–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khanna R, Prasanna GV, Gupta P, Kumar M, Khanna S, Khanna AK. Mammary tuberculosis: report on 52 cases. Postgraduate Med J. 2002;78:422–4. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.921.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmasi A, Asgari M, Khodadadi N, Rezaee A. Primary actinomycosis of the breast presenting as a mass. Breast Care. 2010;5:105–7. doi: 10.1159/000301599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saglam L, Akgun M, Aktas E. Usefulness of induced sputum and fiberoptic bronchoscopy specimens in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Intern Med Res. 2005;33:260–5. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albayrak Y, Kargı A, Albayrak A, Gelincik İ, Çakır YB. Liver Alveolar Echinococcosis Metastasized to the Breast. Breast Care. 2011;6:289–91. doi: 10.1159/000331314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]