Abstract

Infants, 18-24 months old who have difficulty learning words compared to their peers are often referred to as “Late Talkers” (LTs). These children are at risk for continued language delays as they grow older. One critical question is how to best identify which LTs will have language disorders, such as Specific Language Impairment (SLI) at school age, in order to maximize the opportunity for early and appropriate intervention and support. Recent research suggests that LTs are not only slower to learn and speak words than their peers, but are also slower to recognize and interpret known words in real time.

This investigation examined online moment-by-moment processing of novel word learning in 18-month-olds. A low vocabulary, late talking group (LT, N=14) and an age and cognitive-level matched typical group (TYP, N=14) of infants participated in an eye-tracked novel word learning task and completed standardized testing of vocabulary and cognitive ability. Infants were trained on two novel word-picture pairs and then were tested using an adaptation of the looking while listening paradigm. Results suggest that there are differences between groups in the time-course of looking to the novel target picture during testing. These findings suggest that LTs and typical infants developed strong enough representations to recognize novel words using traditional measures of accuracy and reaction time, however interesting group differences emerge when using additional fine-grained processing measures. Implications for differences in emerging knowledge and learning patterns are discussed.

Keywords: Infants, toddlers, late talkers, word learning, fast mapping, eye tracking

1. Introduction

Most children begin saying their first words around 12 months, although there is considerable variance in both comprehension and production at this age. At 18-24 months, infants have approximately 50 words in their productive vocabulary and are beginning to produce two words together. Though this ability to understand and say new words can appear simple, it is a complex process that involves the coordination of many skills that rely on visual and auditory processing. Infants and toddlers learn to link a set of sound sequences to the appropriate referent, often without explicit feedback. By the time most toddlers have reached their second birthday, they are able learn words quickly and seem to increase the number of words in their vocabulary on a daily basis. There are significant individual differences in vocabulary infants’ abilities at 18-24 months, with some infants and toddlers displaying very low levels of vocabulary comprehension and production. These infants are often referred to as Late Talkers (LT).

Late Talkers are healthy full-term toddlers, typically 18-24 months old, with normal cognitive development, normal hearing and no significant birth history; however, they have delays in the onset of producing their first words (Ellis Weismer & Evans, 2002; Ellis & Thal, 2008; Thal, 2000). Most often, Late Talkers are defined by having fewer than 50 words in their productive vocabulary at the age of 24 months, with no two-word combinations and importantly these LTs are at risk for continued language delay (Ellis & Thal, 2008; Thal, Marchman & Tomblin, 2013; Rescorla & Dale, 2013). Persistent language delay in young children can result in Specific Language Impairment (SLI). Children with SLI have consistent difficulty acquiring and using language despite the absence of hearing, intellectual, emotional, or frank neurological impairments (cf. Bishop, 1997; Leonard, 1998). They often continue to have clinically significant language problems throughout adolescence and adulthood (e.g., Bishop & Edmundson, 1987; Tomblin, Zhang, Buckwalter, & O’Brien, 2003), placing them at risk for continued social, academic, and employment failure.

Of the infants classified as LTs at 18-24 months of age, a subset (approximately 17-26%) will continue to have language impairment by age six (Paul, 1996; Rescorla, 2002). A key question for Speech-Language Pathologists, researchers and most importantly, parents, is: How do we determine which late talking infants will have SLI versus those who will be typical by school age? Infant vocabulary levels combined with factors such as socioeconomic status (SES) and family history of impairment have low sensitivity and specificity in correctly classifying children as having SLI at age five (Dale, Price, Bishop, & Plomin, 2003), and correctly identify less than 30% of LTs who will have SLI (Ellis & Thal, 2008; Zubrick, Taylor, Rice, & Slegers, 2007; Thal, Marchman & Tomblin, 2013). The large degree of variability in the rates of word learning may contribute to the difficulty differentiating LTs at risk for SLI from LTs who will go on to develop typically. Further, as Ellis Weismer and colleagues point out (Ellis Weismer, Venker, Evans, & Moyle, 2012), an additional problem in the early identification of children with SLI is that late talking does not denote a clinical diagnosis. It merely means only that a toddler’s expressive and/or receptive vocabulary is at the low end of the normal distribution for toddlers that age. To begin addressing the difficulty in correctly identifying and predicting which LTs will continue to have language learning problems, one approach is to examine other factors that might prove to be better “early indicators” of SLI other than low vocabulary skills. Specifically, that is to examine lexical processing abilities in LT infants and toddlers as they learn new words.

1.1. Lexical processing deficits in SLI

Children with SLI have significant difficulties with the lexical-phonological aspects of word learning and word processing. Lexical-phonological deficits are often defined as difficulty with processing and representation of the word form (Mainela-Arnold, Coady, & Evans 2008; 2010a; 2010b). Thus, words in the lexicons of children with SLI are less well specified as compared to their peers, making their lexical access vulnerable to interference from other words and requiring more of the speech signal for them to recognize words during spoken language processing as compared to typical children (Mainela-Arnold, Evans, & Coady, 2008). Children with SLI are significantly slower and less accurate in accessing and producing words in their lexicon and significantly slower and less accurate in differentiating words from non-words (Katz, Curtiss & Tallal, 1992; Lahey & Edwards, 1996, 1999; Leonard, Nippold, Kail, & Hale, 1983; Leonard, 1998; Leonard, Ellis Weismer, Miller, Francis, Tomblin, & Kail, 2007).

Children with SLI also have significant deficits in phonological working memory, which is a foundational skill necessary for word learning (Alt & Plante, 2006). They have significant difficulty holding nonwords in memory long enough to repeat those nonwords during repetition tasks (e.g., Coady & Evans, 2008), and unlike normal language controls, are unable to use lexical and sub-lexical information from words stored in their lexicon to facilitate repetition of nonwords that are structurally similar to words they already know (Coady, Evans, & Kluender, 2010). The impact of phonological working memory deficits in SLI can be in their poor performance on novel word learning tasks, and children with SLI have significant difficulty learning new words and linking these newly learned words to their referents (Dollaghan, 1987; Ellis Weismer & Hesketh, 1996; Gray, 2003; Rice, Buhr, & Oetting, 1992). They can require more than twice the number of training trials before they are able to show the same level of performance as typical controls (Ellis Weismer & Hesketh, 1996, 1998; Gray, 2005; Rice, Buhr, & Oetting, 1992) and even after increased exposure to the novel word form, children with SLI are slower and less accurate at linking novel labels to novel objects (Alt & Plante, 2006; Dollaghan, 1987; Ellis Weismer & Evans, 2002; Gray, 2004, 2005, 2006; Oetting, Rice & Swank, 1995).

1.2. Novel Word Learning in Late-talking Infants

A key question in LT research is differentiating those infants who are at the low end of the normal distribution from those infants who are significant at risk for SLI. One approach has been to explore the extent to which factors such as lexical processing abilities may be “early indicators” of SLI. Similar to children with SLI, LTs are also significantly slower and less accurate in their ability to recognize familiar words as compared to their peers (Fernald & Marchman, 2012). LT’s also appear to have difficulty linking novel labels to novel objects (Ellis Weismer, Venker, Evans, & Moyle, 2012; Ellis & Evans, 2009; Ellis, Evans, Travis, Elman, Thal, & Lin, 2010) and are slower linking them to novel referents as compared to normal controls (Ellis Weismer & Evans, 2002). LT’s are also less sensitive to phonological characteristics of novel words during word learning tasks and unlike typical children are not able to use lexical and sublexical phonological knowledge stored in their lexicons to aid in novel word learning (Ellis Weismer, Venker, Evans, & Moyle, 2012; MacRoy-Higgins, Schwartz, Shafer, & Marton, 2013).

While the findings from these studies suggest that LTs have similar difficulty attending to lexical-phonological aspects of novel words during novel word learning tasks, traditional novel word learning paradigms do not lend themselves to detailed examination of real-time lexical processing that may be helpful in characterizing lexical processing deficits similar to SLI. Thus, one question is whether examining the time course of processing newly learned novel words by LTs may be useful in determining which LTs are at risk for SLI. Before one can embark on costly longitudinal studies, the first question is whether the time-course of lexical processing of LTs is similar to that of their normal language peers or not.

Recent studies suggest that eye-tracking paradigms may provide useful insights into lexical processing. For instance, SLI eye-tracking studies demonstrate how poorly specified lexical-phonological word forms impacts real-time language processing not only at the initial stages of lexical processing, but throughout the time course of entire word and when listening to spoken sentences (McMurray, Samuelson, Lee, & Tomblin, 2010; Borovsky, Elman, Burns, & Evans 2013), and show that children with SLI experience greater activation of phonological competitor words in their lexicon (McMurray, Samuelson, Lee, & Tomblin, 2010). In particular, children with SLI exhibit fewer looks to pictures of target words and more looks to pictures of phonological competitors, as compared to normal language controls, when phonological competitors both share initial phonemes as well as when they rhyme (McMurray, Samuelson, Lee, & Tomblin, 2010).

1.3. Eye-Tracking

Eye-tracking is also being used in infant research and has its immediate origins from the Looking-While-Listening (LWL) paradigm developed by Fernald (Fernald, 1998; Fernald, Perfors, & Marchman, 2006; Fernald, Zangl, Portillo, & Marchman, 2008). In LWL, participant’s eye gaze is monitored using a video camera while they look at a computer monitor on which are displayed two images. The paradigm allows for moment-by-moment tracking of gaze, and makes it possible to generate real-time measures of not only where a child looks (as is possible with the Preferential Looking paradigm), but the speed with which an image is fixated. LWL has produced a rich body of findings that have revealed a tight link between the speed of anticipatory looking and a range of variables, including a child’s age, socio-economic status, language input, among others (Fernald, Hurtado, Weisleder, & Marchman, 2011; Hurtado, Marchman, & Fernald, 2008; Weisleder, Hurtado, Otero, & Fernald, 2012).

LTs are significantly slower and less accurate when looking at pictures of spoken familiar words in their vocabulary as compared to their normal language age-matched peers (Fernald & Marchman, 2012) and individual differences in infants’ speed and accuracy of recognizing spoken familiar words at 18 months predicts individual differences in vocabulary knowledge at 30 months (Fernald & Marchman, 2012). The individual differences in typical infants’ speed and accuracy of recognizing spoken familiar words at 25 months also predicts individual differences in cognitive and language outcomes at 8;0 years of age (Marchman & Fernald, 2008).

The use of an automated eye-tracker makes it possible to extend the LWL paradigm to displays involving a larger number of objects, but also to track with great precision saccades, fixations, gaze durations, regressions, blinks, pupillometry, among many other variables. Presentation of stimuli can be made gaze-contingent, which is particularly useful for younger age ranges in which participant attention fluctuates.

This very detailed, automatic eye-tracking methodology allows researchers to explore the moment-by-moment lexical and cognitive processing in infants and toddlers (Bergelson & Swingley, 2011; Mani & Huettig, 2013). Examining this detailed lexical processing may enable us to better understand the patterns of recognizing, understanding and learning new words in young children at risk for language impairment. Unlike previous infant looking paradigm studies, eye-tracking allows us various advantages for clinical infant research, but not without some potential error (Aslin, 2012; Morgante, Zolfaghari & Johnson, 2012; Creel, 2012). Using eye-tracking methods, we are able to pre-define regions of interest to examine when the infant is looking at the specific picture or area of interest in addition to classifying an eye shift to one side or the another. Additionally, with eye-tracking methods we are able to acutely focus on questions about the speed, timing, number and pattern of looks, which may give us information about when and how different groups may learn and process novel words. This suggests that eye-tracking can provide the means to examine in detail the time course of novel word learning and novel word processing abilities in LT’s.

Previous eye-tracking studies have found that both infants, as well as children with SLI appear to have different gaze patterns during language processing and word learning tasks as compared to normal language controls (Borovsky, Burns, Elman & Evans, 2013; Borovsky, Elman & Fernald, 2012; Yu & Smith, 2011). For example, Yu and Smith (2011) found differences in eye gaze fixation patterns for 14-months olds with weak versus strong novel word learning abilities. Other research has suggested differences in number of fixations during a sentence comprehension task between children with varying reading comprehension abilities (Nation, Marshall & Altmann, 2003). McMurray and colleagues (2010) also observed that adolescents with SLI had fewer fixations to the target picture than other pictures, while in a younger group of children with and without SLI, Andreu et al., (2012) found that a group of children with SLI was just as fast as the control group in recognizing pictures of nouns, but slower with more difficult stimuli (i.e., verbs).

1.4. The Present Study

The purpose of this study is to use eye-tracking to conduct a fine grained analysis of real-time lexical processing of a novel word in 18 month olds with low vocabulary (i.e. Late Talkers) as compared to a group of age and nonverbal cognitive matched typical 18 month olds. If LTs have difficulty learning novel words, similar to children with SLI, the phonological representations of novel word forms may be poorly specified compared to typical peers. Because eye-tracking allows us to measure continuous differences in lexical activation and representation, it may be possible to use this method to compare relative differences in novel word form comprehension without requiring a binomial correct or incorrect manual response. For example, LT’s may require more of the speech stream before they are able to recognize the word and as a result their first look latencies to target pictures may be slower and durations of their looking fixations may be more variable than that of their normal language peers. Similarly, if the phonological representations of the novel words are poorly specified in LT’s, making the link between the novel word and its referent more tenuous, one might anticipate less stability in the overall looking pattern between target and distractors during the time-course of the spoken word during testing.

Specifically in our study, we predict LTs will show a different pattern of learning novel words than the typical group. The traditional measures of accuracy and reaction time may reveal differences between groups with the LT group having less accuracy overall and slower reaction times as we have seen in previous research. Further, we expect the finer grained measures of learning may reveal additional insights of different learning patterns between groups. Doing these detailed analyses of gaze patterns may help us identify if and how lexical processing differences occur between groups during novel word learning tasks. Thus, we predict the duration of first look to target may be longer for the typical group than the LT group indicating learning of the novel word. This may be an important measure to explore as some previous work has found the longer duration of the first look to target may be indicative of better understanding of the novel word (Ellis et al. 2010). We also predict the number of looking fixations may reveal differences in attention or graded learning differences between groups with the typical group have fewer number of looks in comparison to the LT group. Finally, we hypothesize the time-course plot may reveal different patterns of learning between groups with varying differentiation points between target and distracter. This result may indicate learning at an earlier time point and a stronger representation of the novel word.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 28 infants participated in the study, and consisted of a group of 14 LTs (7 girls and 7 boys, age M = 18 mos.; 9.78 days, SD = 7.49 days), and a group of 14 typically developing controls (7 girls and 7 boys, age M = 18 mos.; 9.92 days, SD = 10.2 days). Group assignment was based on the MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory-Words & Sentences (MBCDI:WS, Fenson, Marchman, Thal, Dale, Reznick, & Bates, 2007). All fourteen late talkers had productive vocabulary scores at or below the 15th percentile on the MBCDI:WS (M = 8.5 percentile, SD = 4.25, range 1-15th percentile) while the fourteen infants in the typical group had productive vocabulary scores above the 20th percentile with an average of 46th percentile on the MBCDI:WS (SD = 21.74, range 23-93rd percentile), see Table 1.

Table 1.

Group descriptive information: Means and SDs: BSID-IIIa, MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentencesb, Maternal Education, Age

| LT (N=14) | TYP (N=14) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayley Cognitive Subscale a | 100.71 (8.73) | 101.42 (7.18) | .82 |

| Bayley Language Subscale a | 95 (7.18) | 104.28 (10.76) | .01 |

|

Words & Sentences

Production Percentile b |

8.5 (4.25) | 46.85 (21.74) | <.001 |

|

Words & Sentences

Number of Words Produced b |

15.21 (8.16) | 89.42 (66.86) | <.001 |

| Mom’s Education | 16.42 years | 16.57 years | .81 |

| Infants Age in Days | 549.78 (7.49) | 551.64 (10.42) | .59 |

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III (Bayley, 2005)

MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentences (Fenson et al., 2007)

The two groups were also matched on cognitive scores, gender, age, and maternal education. Infants in the LT group had an average standard score of 100.71 (SD= 8.73) on the Cognitive Scale of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III (BSID-III) Cognitive and Language subscales (Bayley, 2005), and an average standard score of 95 (SD= 7.18) on the Language Scale of the BSID-III. Infants in the typical group had an average standard score of 101.42 (SD = 7.18) on the Cognitive Scale of the BSID-III and an average standard score of 105.35 (SD = 11.04) on the Language Scale of the BSID-III (see Table 1).

At the initial time of testing participants were 18 months of age. All of the infants included in the analysis were reported to have normal hearing and vision and from monolingual English speaking homes. Additionally, all infants were reported to have normal medical history with no serious complications at birth, and no known neurological impairments or developmental disabilities. All mothers reported a near-term or full- term pregnancy with at least 36 weeks gestation. In addition to the parent report of normal hearing, all infants were reported to have passed infant hearing screenings at birth and had no report of recent or chronic ear infections. To confirm parent report, infants’ middle ear function was assessed using tympanometry during the first visit to the lab to screen hearing. All participants had typical middle ear function at time of testing.

Infants and their parents were recruited in the surrounding metropolitan region of San Diego, California. Parents had responded to flyers and ads posted in the community. The infants came into the lab for two separate sessions. Each appointment was approximately 1.5-hours long and all infants received a children’s book and parents received $10 per session in return for their time, travel and participation.

2.2. Experimental Stimuli

The stimuli for the experimental task consisted of two words that were two-syllable nonsense words with the same low phonotactic frequency (e.g., “pimo” and “moku”). Each of the nonwords were 916 ms in length and were recorded by a native Californian English speaker in an infant directed voice. The auditory stimuli were recorded using a mono channel at 44,100 kHz sampling rate. Each of the object pictures1 were bright and colorful, but differed in form and color. The pictures were JPG files edited to fit a 400 × 400 pixel square, which is a common image size for visual stimuli used in language experiments for children and adults (Borovsky et al., 2012; 2013). Each object served equally often as target and distracter and location of the pictures were counterbalanced on the screen. These words were two of the stimuli used in Graf Estes, Evans, Alibali, & Saffran (2007) and were not heard or exposed previously. Both the object pictures and novel words were counterbalanced.

2.3. Procedure

Infant test sessions took place in child-friendly testing rooms within the Center for Research in Language at UCSD. Each of the two visits lasted ~1.5 hours. During the session, parents signed the consent forms and returned the MBCDI:WS form (which was sent home prior to the visit)2, and infants completed the experimental and behavioral tasks.

2.3.1. Novel Word Learning Task

The task consisted of a training phase followed by a test phase.

1) Training

The training phase consisted of two novel label-object pairs trained over four trials, which occurred at the beginning of the experiment. During the training trials the novel object moved back and forth across the screen for 20 seconds while the novel word label played over speakers seven times (therefore each object was labeled a total of 14 times across two 20-second blocks). We chose to present the novel items across fixed set of four 20-second blocks, rather than using a criterion approach, to control the number of exposures to the novel label object pair and allow for potential to explore differences in learning during the training phase. This training phase was recorded by the eye-tracker, however, the each infants’ attention was able to vary.

2) Test phase

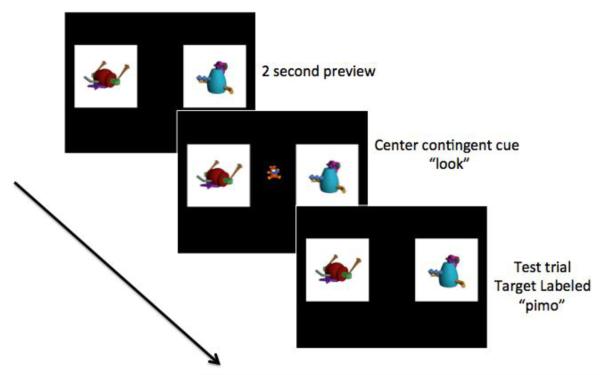

The test phase was initiated immediately after the training phase. Each test trial began with a silent object preview period where the participants saw the two novel object pictures on the screen (the position of the picture on the left or right side of the screen was counterbalanced across trials). This preview period alleviated memory demands placed on the infant by establishing a baseline period for all infants to view the location of the two objects before the test trials began. Following the preview period, a center attention-getter picture (such as a small picture of a teddy bear or toy duck) appeared at the midpoint between the two pictures. The purpose of this center attention-getter stimulus was to control the starting fixation position for all infants before they heard the target label (i.e., starting at the center fixation point for each trial) and to insure all infants attended to the center point prior to beginning the test trial. See center gaze-contingent cue in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Example of Novel Word Test Trial

The appearance of the central attention cue was paired with an auditory stimulus, “look” to help direct the infant’s attention towards the central stimulus. Once the participant viewed the central object for 100 ms, the central object disappeared and the Target and Distractor objects appeared and the Target was labeled. The novel object pictures remained on screen for a total of four seconds post object-label. There were a total of eight test trials. Each trial (including preview) lasted a total of six seconds (see Figure 1 for example). In addition to the test trials there were other filler trials with known words as well as “whoopie” trials, which included interesting images accompanied by encouraging words. The average length of the recording session was approximately 8 minutes.

2.3.2. Eye-Tracking Methods

The eye-tracking was controlled by the SR Research Eyelink Experiment Builder software and eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 2000 Remote Eyetracker with remote arm configuration at 500 Hz (SR Research, 2011). The Eyelink system automatically classifies eye movements as saccades, fixations and blinks using the eye-tracker’s default threshold settings. The position of the display and eye-tracking camera was maintained approximately 580–620 mm from the face using a moveable remote monitor arm. Fixations were recorded automatically every 2 ms for each trial from the onset of the images until the end of the task. Offline, the data were binned into 10ms intervals, then analyses were performed based on predefined time periods of interest.

The infant participant sat in his/her parent’s lap or in a child booster seat approximately 24 inches from a 17″ LCD display monitor. A small sticker was placed on each participant’s forehead to allow the eye-tracker to measure eye movements. Before the task, a manual five-point calibration and validation routine was completed, using a standard animated black and white bull’s-eye image and whistling noise. The calibration process typically took less than two minutes. To prevent parents from influencing their infants’ responses, the parents wore headphones during the tasks.

Once calibration was completed, stimuli were presented using a PC computer running SR Research Eyelink Experiment Builder software (SR Research, 2011). In between trials, a dot/bull’s eye appeared in the center of the screen and served as a drift correction before each trial. Once the participants fixated on this center dot location, the experimenter began the trial.

3. Results

3.1. Approach to Analysis

Our data consisted of recordings of participants’ eye gaze to two images during a testing phase after they had been exposed to novel object-word pairs. We first examined whether differences in the overall time-course occurred between groups by examining gaze divergence points during the time course (Section 3.2). The goals of the second set of analyses (Section 3.3) were to: 1) use a traditional analysis to assess overall learning of all trials after a novel word learning task and 2) to identify “learned” or “correct” trials to further analyze more fine grained detailed aspects of novel word learning. Using the same definition and method as Yu & Smith’s (2011), where a trial was considered “learned” if infants’ looking towards the target object in response to the spoken label exceeded looking towards the distractor image. This was examined trial by trial for each of the target words and a target word was counted as learned if the absolute looking to the target was greater than to the distractor for each trial. For those trials identified as learned several fine-grained analyses were then conducted to characterize the time course of recognition of newly acquired (novel) words in both groups. Specifically, we measured: (1) the latency of the first look to target, (2) duration of the first look fixation, (3) number of fixations towards the images in response to the novel word label using only trials where the participant was correct (Section 3.4-53). Finally, we conducted a post-hoc exploratory analysis (Section 3.6) to examine spatial looking patterns, which may be of general interest with respect to understanding group differences in general gaze behaviors across groups.

Analyses focused on group differences in eye-movement behavior in a time window between 500-2300 ms after the onset novel label. This analysis period was selected because previous research suggests the minimum latency to initiate an eye movement in infants is approximately 233-367 ms, with mean latencies considerably longer (Canfield, Smith, Brezsnyak, & Snow, 1997; Haith, Wentworth, & Canfield, 1993). Further, previous studies using the LWL procedure consistently examine familiar word recognition over an 1800 ms time window from target word onset (e.g., Fernald, Thorpe, & Marchman, 2010; Fernald & Marchman, 2012). Additionally, novel word learning in children and infants is a process that takes longer than in recognition of known words (Bion, Borovsky, & Fernald, 2013). Therefore, rather than using a random time window for our analysis of our experimental data, we chose to use a shifted window of 1800 ms, beginning at 500 and ending at 2300 ms. This time window selection allows us to examine data which encompass the longer latencies for novel word recognition.

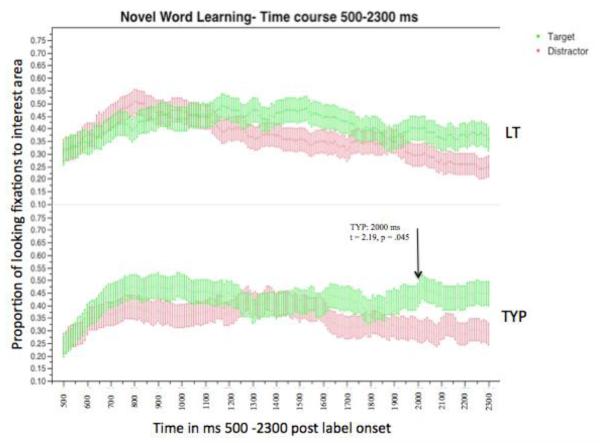

3.2. Target divergence time

The mean proportion of time that the LT and typical participants fixated on each of the images (target and distractor) was calculated at each 10-ms time window post label-onset (Figure 3) for all trials. Visual inspection of these time-course plots indicates differences between groups. Specifically, for the LT group, initially there seems to be slightly more fixations to the distractor picture than the target picture. Later in the time-course, the timing at which fixations to the target object diverges from distractor fixations also appears different between groups.

Figure 3.

Novel word learning time

The target divergence time measure is defined as the time at which fixations to the “target” object diverges from fixations to the “distractor” (Borovsky et al., 2012; Borovsky et al., 2013). To examine the divergence during incremental lexical processing of novel words during the time course, the mean proportion of time fixating to the target and distractor images at each 10 ms time window was calculated across all participants in both the LT and typical groups. These time course plots are helpful to visualize qualitative differences in looking patterns. In our analysis of time course plots and divergence time there was no minimal criterion of amount of time to look at either picture. To test whether there may in fact be differences in looking patterns by each group, point-by-point t-tests at each 10 ms bin between mean looking proportions to the target object and mean looking proportions to the distractor object were calculated. As done in earlier work, a criterion was used to minimize the possibility that these multiple comparisons may yield spurious differences by chance. Specifically, the time point reported is the earliest time point that a minimum of five consecutive two tailed t-tests with an alpha level of p < .05 indicate a significant difference between the fixation to the target compared to distractor (see Borovsky, Elman & Fernald, 2012).

Using these analyses, we see different divergence patterns between groups. Specifically, the typical group showed distinction between target and distractor at the 2000 ms post label onset and continuing to the end of the time window (t = 2.19, p = .045), whereas the LTs did not have the five consecutive points of significant divergence at any time during the time window (see Figure 3). When we calculated a target divergence time for each individual infant using the same procedure as above, only 3 of 14 LTs showed a significant divergence between the novel target and distractor pictures, while 11 of 14 typical infants displayed a significant divergence time between the two pictures.

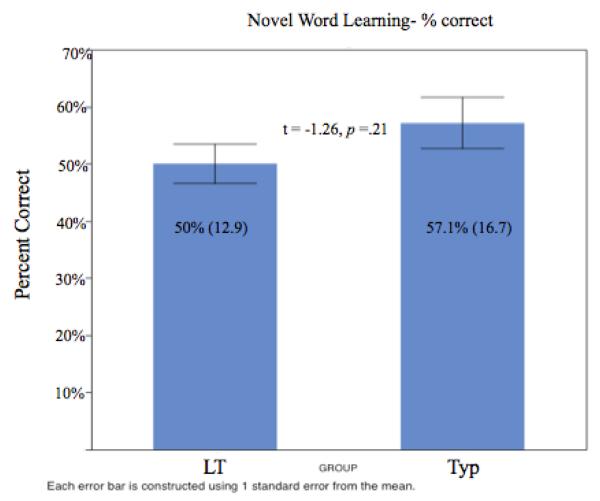

3.3. Accuracy and learning

As described above (3.1) we initially identified “learned” trials using a metric defined by Yu & Smith (2011). Following this procedure, we calculated an overall accuracy score on a trial by trial basis based upon whether the infant’s proportion of looking to the target exceeded the infant’s proportion of looking to the distracter across the 500 – 2300 ms time window. A trial was counted as “learned” if there was greater proportion of looking to the target than to the distractor. The number of learned trials out of the total eight novel test trials was calculated for each infant to obtain an accuracy or learning score. This allowed us to measure whether there were overall learning differences between groups using traditional analyses. Based on this measure the LT group learned an average of 4 out of 8 trials correct (range 3-6) and typical group learned an average of 4.57 out of 8 trials correct (range 2-7). Using this approach, the LT group was no less accurate in learning to link the novel word to a novel object as compared to the typical group (LT = 50%; TYP = 57.1%), (z (26) = −1.23, p = .21; See Figure 2). Using the traditional approach the number of learned trials did not differ for the LT and typical groups, however, it is possible that the relative differences between proportion of looking to target and distractor differed. For the LT group, the average proportion of looking to the target was .71 (SD = .20) and distracter M= .15 (SD = .17). For the typical group the average proportion of looking to the target was .60 (SD = .20) and distracter was M= .18 (SD = .16). The looking proportions to the two objects were significantly different for both the LT and typical groups respectively, (LT: t (55) = −12.92, p < .001) (TYP: t (63) = −11.74, p < .001). In examining the difference in looking proportions between groups, mean differences in looking proportion between target and distractor were significantly different between groups (p = .01). Specifically, across identified “learned” trials, the mean difference between the target and distractors was .56 (SD = .33) for the LT group and for the typical group the mean difference was .42 (SD = .29).

Figure 2.

Accuracy: Total correct out of 8 trials by group

3.4. Latency and duration of first look to target

For correct or “learned” trials, we then examined the latency of the first look to the target picture during the 500-2300 ms time window. Latency was calculated as the timing of the saccade that landed on the target picture after the onset of the label. There were no significant differences in the latency of first look to target picture for the LT (M = 860.87, SD = 392.54) and typical (M = 960.19, SD = 412.13) groups, t (26) = −.953, p = .343, d = .246). We were also interested in the duration of the first look to target. Prior research suggests that the duration of first look to the target differs between SLI and LT children as compared to normal controls (Borovsky et al., 2013; Ellis et al., 2010; Schafer & Plunkett, 1998). Similar to latency of the first look to target the LT infants did not differ from the typical group in the duration of this first look to target (LT: M = 541.64 ms (SD = 488.72); typical: M = 433.62 ms (SD = 241.41), t (26) = 1.56, p = .12, d = .15; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Group comparisons for fixation measures of mean duration, and mean number of fixations to target picture and mean number of fixations during trial

| Fixations to Target Pieturc | LTN=14 | TYPN=14 | t-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of 1st Fixation (in ms) | 541.64(488.72) | 433.62 (241.41) | 1.56 | .12 |

| # of Fixations to Target | 2.48(.93) | 2.48(.95) | −0.12 | .989 |

| # of Fixations during Trial | 3.98 (1.25) | 4.35 (1.13) | −1.72 | .086 |

3.5. Fixations to Target

Previous work has found differences in number of fixations between LT and typical groups (Ellis, Evans, Travis, Elman, Thal & Lin, 2010); as well as among better and poorer reading comprehension abilities (Nation et al., 2003). We examined the average number of fixations to the target, defined as the average number of times the infant fixates to the target picture during the time window; and average number of fixations during the trial which is defined as the number of times the infant fixates on the experimental screen at any point during the time window4. Again, there was no significant difference in the total number of fixations to the target picture during the course of the trial for the two groups (LT: M = 2.48, SD = .95 and TYP: M = 2.48, SD = .93, t (26) = −.012, p = .989), nor a significant difference in the total number of fixations across the correct test trials (LT: M = 3.98, SD = 1.25 and TYP: M = 4.35, SD = 1.13, t (26) = −1.72, p = .086; d = .31 see Table 2).

3.6. Post hoc analyses

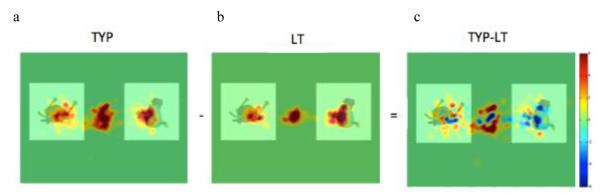

The initial time-course analysis revealed that there were differences between LT and typical groups in the looking patterns to two large areas of interest of 400 × 400 pixels each. While the time-course analyses are useful, these areas were large enough to have the potential to wash out differences in eye-movement behavior that may occur on a finer spatial scale within predefined areas of interest. Therefore, we decided to examine patterns of looking on a finer spatial scale as an exploratory post-hoc analysis.

3.6.1. Fixation Distribution

Recent work used a spatial analysis in a eye-tracking study that compared typical developing adolescents and adolescents with SLI in a sentence comprehension task and found that this spatial analysis revealed significant differences in gaze patterns between the two groups (Borovsky et al., 2013). It suggests there are more global differences between SLI and typical groups in what we might call “style of gaze” (Borovsky et al., 2013). This recent finding piqued our curiosity as to whether there also were similar differences between LT and typical groups in the spatial distribution of gaze across the visual scene. Such potential differences might reflect, for example, a tendency to fixate on more central or more peripheral areas of the display or a more focal or diffuse pattern of gazes.

We conducted a post-hoc exploratory analysis in our data to examine whether there are differences on a finer spatial scale within the predefined areas of interest. To our knowledge, this analysis has been carried out between SLI and typical school-age groups, but not yet in any infant-toddler groups. To examine potential spatial differences in eye movements that were both language-mediated and linguistically unaffected, we calculated fixation distribution maps for each group using iMap v2.1 software (Caldara & Miellet, 2011). As in our earlier analyses, the eye trackers default threshold settings for defining fixations and saccades as well as the same time period were used for this analysis. Maps were generated by summing the coordinates of mean fixation durations for each participant across the relevant time-window and then normalizing these durations to z-scores. These data were smoothed with a 20-pixel (approximately 1-degree visual angle) filter. iMap determines statistical significance using a robust multiple correction Pixel test (Chauvin, Worsley, Schyns, Arguin, & Gosselin, 2005). Because this approach has been questioned recently in the literature (McManus, 2013), we followed the strategy recommended by Miellet et al. (2014) for carrying out additional analyses that do not rely on the assumptions that have been questioned.

3.6.2. iMap analyses

In the first analysis, iMap2.1 was used to locate areas where there were significant differences in gaze duration between typical and LT groups. Figure 4a shows fixation durations for the typical group; Figure 4b shows fixation durations for the LT group. In Figure 4c, we see the difference map indicating areas where TYP>LT (red) and where LT>TYP (blue); (Zcrit for the difference map, assuming two-tailed tests, is 4.438875; areas that exceed Zcrit are shown with white lines around them).

Figure 4.

Group fixation maps and difference fixation maps. Areas of dark red in the subtraction image indicate regions where the Typical group fixated significantly more than did the LT group, and areas of dark blue indicate areas where the LT group fixated more than the Typical group.

Due to the controversies about how to determine significance with the very large number of comparisons in voxel/pixel data (similar to fMRI data), we ran a second set of analyses that did not involve multiple comparisons. We used the data-driven ROIs and calculated subject means for fixation duration, total fixation duration, and # of fixations. The means were broken down by group (TYP vs. LT) and “area”. “Area 1” were areas where the initial iMap analysis suggested greater durations for TYP>LT; “Area 2″ were areas were the reverse was true. Because of unequal variance across TYP and LT groups, we used the Welch t-test (two-tailed, independent groups) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

ROI analysis of mean total fixation duration and number of fixations

| Area 1 (TYP >LT) | Area 2 (LT>TYP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean fixation duration | p<0.002* | p<0.001* |

| Total fixation duration | p<0.002* | p<0.001* |

| # of fixations | p<0.002* | p<0.001* |

Although, these data are exploratory, the gaze patterns of the two groups seem to differ. Specifically, the LT group shows a more narrowed looking pattern and a bias towards the right side of the screen, while the typical group shows a gaze pattern reflecting looking to both sides of the screen and a more global gaze pattern (see Figure 4).

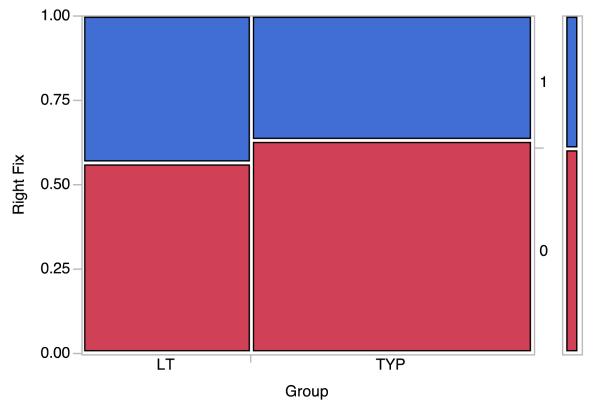

3.6.3. Analysis of RVF bias

To verify whether the apparent LT bias toward the right side of the display was statistically significant, the following additional analysis was conducted. We used the raw fixation data from the eye-tracker and for each fixation (for each subject), determined whether the fixation was to the right of the left-side border of the image that was displayed on the right side of the display (the display was 1280×1024 pixels; the left edge of the right image was at approximately 800 pixels). Fixations to the right of this were coded as “1” and fixations to the left were coded as “0”.

These data were nominal (binary) in form, therefore we carried out contingency analyses, using both ChiSquare (Likelihood ration) and Fisher Exact Tests. The ChiSquare value (df = 1; N=1185) was p = 0.0200. Fishers Exact Test (test that probability (Right Fix = 1) is greater for the LT group than TYP group, yielded a p = 0.0117, d = −4.47, see Figure 5). These analyses indicate that the LT group has fewer overall fixations compared to the typical group, but they did have a right side bias. The LT group focused on a more narrow area and spent relatively less time fixating on the details of the pictures. The potential implications of these differences are addressed in the discussion below.

Figure 5.

Mosaic plot revealing right field bias in LT group compared to TYP group.

4. Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to examine the real-time moment-by-moment online lexical processing abilities of late talking and typical infants at 18 months after a novel word learning task. First, we asked whether 18-month-old LTs interpret and learn novel words, like typical infants. Using a different experimental method and slightly different design than previous studies, the evidence from the current study of late talking and typical 18-month-olds suggests that there are emerging differences between groups in learning and interpreting novel words.

If we look at only the traditional measures of overall accuracy and latency of fixating to the novel target picture, we do not see significant differences between the LT and typical groups. However, traditional accuracy analyses may not be the most useful analysis in our eye tracking paradigm. While the similar result between groups was not initially expected, it was useful to identify which trials would most likely reflect meaningful looking behaviors or emerging comprehension of the novel word. We interpret this result as indicating that both groups had developed similar and sufficiently strong word representations during the test trials to support the behaviors that are reflected in these measures. We would expect similar results from other tasks, such as Preferential Looking, that yield roughly similar outcome measures.

Unlike previous research using the traditional fast-mapping tasks or the LWL paradigms to measure word recognition, the current study used eye-tracking methodology to measure word learning, which allowed additional details to be examined during a novel word-learning task. The current study also used a slightly different design (i.e., gaze contingent) to ensure that every infant began each trial at the same location. Using the gaze contingent design required that the infants’ must focus their attention on the center location before the target label was played and the picture options displayed. The infant’s latency of the first saccade, starting at a center point, then measured the latency time from the center to the target picture. The benefits of this gaze contingent modification were that all infants were required to attend to the center point prior to the beginning of each test trial, which then allowed the data from each test trial to be used to analyze latency and other important variables. The disadvantage of this design was the infants’ attention may still have varied during the test phase. Further, a potential limitation of the measure of latency time in our design is it may capture a potentially random looking pattern to the target picture. Due to this potential known limitation of latency time in the study we wanted to include and examine measures beyond latency time (e.g. first look, duration, time course differentiation, etc.)

This study also included a unique phase where the pictures were shown or “previewed” before the word was played during testing to control for potential differences in the memory abilities of the LT and typical infants. This methodology also allows us to interpret our results using a perspective of graded learning or emerging knowledge and to step away from the traditional “all or nothing” interpretation of word learning behavior. Instead we can examine the pattern of novel word learning and the qualitative details of what is learned and how that information is processed. This helps us interpret the findings that did distinguish the LTs and typical groups.

Using the more traditional approach to accuracy, our results found that both the LT and typical groups had similar overall learning of the novel words. At first glance the overall accuracy or learning results-- 50% and 57%, respectively, may seem at or below chance performance in comparison to traditional 2FC designs. However, what we were actually interested in was what those trials were reflecting by completing the more detailed aspects of the fine grained analysis for the two groups. Our design reflects continuous looking data and accuracy in this case was defined by whether an infant’s proportion of looking was greater to the target than the distracter across trials. Importantly, in our study we do not classify infants looking simply to the left or right side, but specific predefined regions of interest. If we took a simple proportion of the number of pixels that correspond to the pictures out of the pixels available on the monitor, chance would be 24.4% of the area and would be a better indicator of chance. Thus, if using 24.4% chance as a criterion for learning, both groups did learn the novel words, yet their learning may be at different levels of knowledge. Therefore, both groups had sufficiently strong word representations during the test trials as reflected in overall accuracy as well as proportion of looking. While the results of traditional measures, such as accuracy and reaction time suggest no differences between the groups, the other more fine-grained measures such as gaze divergence, among others may be more reflective of whether both groups learned and processed the novel words in the same way.

Despite finding no significant group differences in overall accuracy or latency (i.e. traditional reaction time) to target, we did find that the point of divergence between target and distractor pictures was different for each group (LT = ns8; TYP = 2000 ms). When examining the time-course of the two groups (See Figure 3), the late talker group had initial overlap of looking to both the target and distractor, but does not show significant distinction between the two pictures, while the typical group initially shows more separation in looking to the two pictures and ultimately distinguishes the target word picture at an earlier time point. We interpret these data as indicating emerging differences in the level of knowledge of the newly learned word.

Further, the moment-by-moment processing in the time-course plots revealed emerging group differences in the mean proportion of time spent fixating during the test trials with typical infants having greater proportion of time fixating to the target. These results indicate that infants with low compared to typical 18-month vocabularies may have different emerging representations of novel words across the time course. This data along with the exploratory analyses suggest that the typical group is potentially activating and considering both objects in response to the label before settling on the target and this is occurring earlier in the time course than we see in the LT group. At first glance, the target divergence differences and proportion of fixations during the time course analysis may seem slight, however these measures are more precise than other measures that classify looking anywhere to the left or right (not necessary the picture) as used in many LWL paradigms. Group differences in LWL paradigms may inflate fixation proportions in their looking measures, while in our analysis we only count looks to the 24.4% of the pixels where the pictures physically exist on the screen.

Such differences in divergence times have been noted elsewhere. Borovsky, Elman, & Fernald (2012), in an eye-tracking study in which typically developing children (aged 3-10 years) and college age adults were presented with simple sentences and asked to point to a final target that the sentence was about, showed group differences in divergence times. The specific effect was that age-normalized vocabulary was the primary predictor of the speed with which participants’ gaze toward the target diverged from distractors. This was true across all age groups. In fact, children with high age-normalized vocabularies had faster divergence times than college-aged adults with low age-normalized vocabularies.

The interpretation of gaze divergence remains open. However, given that this measure distinguishes LT from typical groups, we offer some suggestions about what it may reflect. First, recall that the time of divergence is not the same as the time of first fixation. The latter simply measures the moment in time when the first look toward the target occurred. LT and typical groups do not differ significantly in time of first fixation. This suggests that the conditions of learning in our study have enabled the two groups to develop representations that are sufficiently strong to drive the mechanisms required to guide an initial look towards the target object. This does not mean that the representations are equal in all regards, however.

Unlike first fixation point, the divergence point is the moment in time (operationally, the five successive moments) when a participant’s overall pattern of looking shifts between competing images. That is, the point of divergence indicates when a pattern of sustained looking to the target occurs. We interpret this as directly reflecting the participant’s focus of attention. In the case of the typical participants, the focus of attention is on the correct referent of the novel word by 2000 ms post label onset. In the case of the LT, attention appears to remain divided. What might drive these differences in attentional patterns? We propose several hypotheses. First, the earlier focus on the target by typical developing children might reflect a greater confidence level that the object is indeed the reference to the auditory stimulus, whereas the LTs are uncertain and still checking (and thus their gaze continues to wander back and forth). This would be consistent with the typically developing children having developed more robust representations than the LT children (even though both representations are sufficiently strong to initiate first fixations at roughly the same point in time). A second possibility is that perhaps the attentional difference reflects a familiarity preference that is manifest in the typical group by the 2000 ms time point. The LTs, in contrast, not having yet mastered the novel word, might have their attention be divided by competing between a familiarity preference and novelty preference (see Horst, Samuelson, Kucker, & McMurray, 2011; Mather & Plunkett, 2011 for review of novelty vs. familiarity preferences in infants word learning). A third possibility is that LTs have intrinsic difficulties in controlling attentional mechanisms. This possibility is consistent with the Borovsky, Burns, Elman, & Evans (2013) finding that spatial maps of gaze of SLI adolescents showed more diffuse looking patterns, compared to their TD controls. A difference in attentional skills between typical and LT children would make sense from the perspective of word learning, because difficulties attending to (or conversely, disengaging from) a target stimulus could interfere with learning the link between a novel word and its referent. We believe that understanding the differences in representations and processes that are responsible for the differences in typical and LT divergence times should be an important goal for future research.

Further, the exploratory analysis examining the spatial gaze fixation patterns between groups suggest that in addition to the similarities and differences in learning novel words, LT and typical groups may also be viewing and processing the novel images differently. The exploratory analysis revealed that the LT group processes the images more narrowly and show a right field bias, whereas the typical group processes the images more globally and distributed evenly across the two sides of the display. Although there is limited work examining visual processing of novel object in infants and toddlers, work by Akshoomoff, Stiles, & Wulfeck suggest that children with language impairment may have an immature and less efficient approach to the visuospatial processing tasks (2006).

From an SLI perspective, research suggests that school age children with SLI may also have deficits in visual processing in addition to their verbal impairments (Alt, 2013). Further, research has consistently found that children with SLI have difficulty learning the lexical-semantic features of novel words in addition to their lexical-phonological processing deficits. In particular, children with SLI attend to qualitatively different semantic features of novel objects during word learning tasks as compared to typical children (Alt & Plante, 2006; Alt, Plante, & Creusere, 2004; Munro, 2007). Additionally, taken together these weaker representations in novel words in children with SLI and the early processing differences we see in our current late talkers may be useful in discovering both where and why children with novel word learning difficulties have weaker representations of new words. Taking our time course and spatial gaze findings andthe findings from Borovsky et al., 2013, these data suggest that examination of the visual processing during novel word learning is warranted in future research and may give insight into differences between late talking and typical infants in aspects “when” during the time course and “where” infants are looking during lexical processing tasks.

In conclusion, our study found differences as well as some interesting similarities between the LT and typical groups for time-course measures and emerging differences in additional fine-grained processing measures (i.e. number of fixations) as well as differing spatial patterns. Importantly, using eye-tracking measures allows us to examine interesting additional details of looking behavior that suggests interesting similarities as well as unique emerging differences between groups while they learned new words. Future work should continue to examine the fine grained processing details of novel word learning to determine how, why and potentially where there are differences in the emerging knowledge and learning patterns during lexical and visual processing in young infants and toddlers.

Highlights.

We examine online moment-by-moment processing of novel word learning in 18-month-old late talking and typical infants

Both late talking and typical infants developed strong enough representations to recognize novel words using traditional measures of accuracy and reactions time

There are differences between groups in the time-course of looking to the novel target picture

Additional fine-grained processing measures reveal emerging group differences

Late talkers may show differences in emerging knowledge and learning patterns

CEU questions.

1) What is one benefit of the gaze-contingent design used in the eyetracking study?

There are no benefits of a gaze-contingent design.

Does not matter where the eye is fixated.

Can measure language comprehension in real-time.

Allows each trial to begin from the same center location.

2) Late Talkers and typical peers have significantly different first fixation durations to the target novel words (T/F) (False)

3) Late Talkers showed interesting spatial differences in their eye-gaze patterns. (T/F) (True)

4) Which description below best summarizes the timecourse of fixations to the target and distractor?

Late Talkers showed an identical pattern of fixations to the target and distractor pictures compared to the typical group.

Late Talkers showed a different pattern of fixations to target and distractor pictures compared to the typical group and never distinguished between the two pictures.

The typical group never distinguished between the target and distractor pictures.

The typical group distinguished between the target and distractor pictures early in the timecourse but not across the entire timecourse.

5) The findings of this study suggest?

Late Talkers show slower speed of lexical processing while learning novel words.

Late Talkers learn novel words the same way as typical infants.

Late Talkers may have different emerging representations of novel words than typical infants.

Late Talkers view and process the pictures like their typical peers and visual processing should not be taken into consideration.

Learning Outcomes.

The reader will be able to understand many benefits of using eye- tracking methods to study young infant and toddler populations with and without language disorders. Readers will learn that examining moment-by-moment time course of novel word learning allows additional insight into different learning patterns. Finally, readers should understand the data from this article suggest late talkers may have different emerging representations of novel words than their typical peers, which may contribute to their difficulty learning new words.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to the families who participated in this project. We also wish to thank Kim Sweeney and research assistants at the Center for Research in Language at UCSD for their assistance during this project. This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health: 5F31DC012254 to E. Ellis, DC10106 and DC01368 to A. Borovsky, HD053136 to J. Elman, and DC005650 to J. Evans.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Object pictures were adapted Fribbles images. Tarr, M. (2011) Fribbles. [Stimulus images]. Available from the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition and Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, http://www.tarrlab.org/.

MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentences were obtained from the parent, but were scored after the visit by a research assistant blind to the experimental questions and details of the test session.

Based on this measure of accuracy the LT group had an average of 4 out of 8 trials correct (range 3-6) and typical group had an average of 4.57 out of 8 trials correct (range 2-7), these trials were used in subsequent analyses of reaction time, duration of first look, and number of trials.

The two groups were assumed to be independent for the analyses.

ns = non-significant. The LT group did not have the five consecutive points of significant divergence during the time window.

REFERENCES

- Akshoomoff N, Stiles J, Wulfeck B. Perceptual organization and visual immediate memory in children with specific language impairment. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12:465–474. doi: 10.1017/s1355617706060607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt M. Visual Fast Mapping in School-Aged Children With Specific Language Impairment. Topics in Language Disorders. 2013;33:328–346. doi: 10.1097/01.TLD.0000437942.85989.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt M, Plante E. Factors that influence lexical and semantic fast mapping of young children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:941–954. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/068). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt M, Plante E, Creusere M. Semantic features in fast-mapping: Performance of preschoolers with specific language impairment versus preschoolers with normal language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:407–420. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu L, Sanz-Torrent M, Guárdia-Olmos J. Auditory word recognition of nouns and verbs in children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI) Journal of Communication Disorders. 2012;45(1):20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslin D. Infant eyes: A window on cognitive development. Infancy. 2012;17:126–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson E, Swingley D. At 6 to 9 months, human infants know the meanings of many common nouns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2011;109:3253–3258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113380109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bion R, Borovsky A, Fernald A. Fast mapping, slow learning: Disambiguation of novel word–object mappings in relation to vocabulary learning at 18, 24, and 30 months. Cognition. 2013;126:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Uncommon understanding: development and disorders of language comprehension in children. Psychology Press; Hove: 1997. Hove: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM, Edmundson A. Language impaired four year olds: Distinguishing transient from persistent impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:156–173. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5202.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovsky A, Burns E, Elman JL, Evans JL. Lexical Activation during Sentence Comprehension in Adolescents with History of Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2013.09.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovsky A, Elman J, Fernald A. Knowing a lot for one’s age: Vocabulary and not age is associated with the time course of incremental sentence interpretation in children and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112:417–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield RL, Smith EG, Brezsnyak MP, Snow KL. Information processing through the first year of life: A longitudinal study using the visual expectation paradigm. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1997;62(2):i–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldara R, Miellet S. iMap: A novel method for statistical fixation mapping of eye movement data. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43(3):864–878. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey S, Bartlett E. Acquiring a single new word. Proceedings of the Stanford Child Language Conference. 1978;15:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin A, Worsley KJ, Schyns PG, Arguin M, Gosselin F. Accurate statistical tests for smooth classification images. Journal of Vision. 2005;5(9):659–667. doi: 10.1167/5.9.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield RL, Smith EG, Brezsnyak MP, Snow KL. Information processing through the first year of life: A longitudinal study using the visual expectation paradigm. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1997;62(2):i–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creel SC. Looking ahead: Comment on Morgante, Zolfaghari, and Johnson. Infancy. 2012;17(2):141–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale P, Price T, Bishop D, Plomin R. Outcomes of early language delay: I. Predicting persistent and transient language difficulties at 3 and 4 years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:544–560. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/044). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan C. Fast mapping in normal and language-impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:218–222. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E, Evans JL. Word Learning and Habituation in 18-Month Olds. Poster presented at the annual American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in New Orleans, LA.Nov, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E, Evans JL, Travis K, Elman J, Thal D, Lin C. A Microgenetic Analysis of Word Learning in Infants with and without Language Delay using a Preferential Looking Paradigm. Symposium on Research in Child Language Disorders.Jun, 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E, Thal D. Early language delay and risk for language impairment. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education. 2008;15:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Evans J. The role of processing limitations in early identification of specific language impairment. Topics in Language Disorders. 2002;22:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Hesketh LJ. Lexical learning by children with specific language impairment: Effects of linguistic input presented at varying speaking rates. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1996;39:177–190. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3901.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Hesketh LJ. The impact of emphatic stress on novel word learning by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1444–1458. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4106.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Venker C, Evans JL, Moyle M. Fast Mapping in Late Talking Toddlers. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2012;34:69–89. doi: 10.1017/S0142716411000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Marchman V, Thal D, Dale P, Reznick J, Bates E. MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: Users’ guide and technical manual. 2nd edition Paul H. Brookes; Baltimore: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A. Approval and disapproval: Infant responsiveness to vocal affect in familiar and unfamiliar languages. Child Development. 1998;64:657–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Hurtado N, Weisleder A, Marchman VA. Infants’ early language experience influences emergence of the fast-mapping strategy. Meeting of the society of research on child development; Montreal CA. April 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Marchman VA. Individual differences in lexical processing at 18 months predict vocabulary growth in typically- developing and late-talking toddlers. Child Development. 2012;83:203–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Perfors A, Marchman VA. Picking up speed in understanding: Speech processing efficiency and vocabulary growth across the 2nd year. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:98–116. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Thorpe K, Marchman VA. Blue car, red car: Developing efficiency in online interpretation of adjective-noun phrases. Cognitive Psychology. 2010;60:190–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Zangl R, Portillo AL, Marchman V. Looking while listening: Using eye movements to monitor spoken language comprehension by infants and young children. In: Sekerina I, Fernandez E, Clahsen H, editors. Developmental psycholinguistics: On-line methods in children’s language processing. John Benjamins; Amsterdam: 2008. pp. 97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Graf Estes K, Evans JL, Alibali MW, Saffran JR. Can infants map meaning to newly segmented words? Statistical segmentation and word learning. Psychological Science. 2007;18:254–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word-learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: What predicts success? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:56–67. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: Predictors and poor learners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:1117–1132. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/083). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: Effect of phonological or semantic cues. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:1452–1467. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/101). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. The relationship between phonological memory, receptive vocabulary, and fast mapping in young children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:955–969. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/069). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haith MM, Wentworth N, Canfield RL. The formation of expectations in early infancy. In: Rovee-Collier C, Lipsitt LP, editors. Advances in Infancy Research. Vol. 8. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1993. pp. 251–297. [Google Scholar]

- Horst JS, Samuelson LK, Kucker SC, McMurray B. What’s new? Children prefer novelty in referent selection. Cognition. 2011;118:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado N, Marchman VA, Fernald A. Does input influence uptake? Links between maternal talk, processing speed and vocabulary size in Spanish-learning children. Developmental Science. 2008;11:F31–F39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz W, Curtiss S, Tallal P. Rapid automatized naming and gesture by normal and language-impaired children. Brain and Language. 1992;43:623–641. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(92)90087-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey M, Edwards J. Why do children with specific language impairment name pictures more slowly than their peers? Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1081–1098. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3905.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey M, Edwards J. Naming errors of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, Hearing Research. 1999;42:195–205. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4201.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LB. Children with specific language impairment. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Ellis Weismer S, Miller C, Francis D, Tomblin B, Kail R. Speed of processing, working memory, and language impairment in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:408–428. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/029). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LB, Nippold MA, Kail R, Hale CA. Picture naming in language impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1983;26:609–615. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2604.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRoy-Higgins M, Schwartz R, Shafer V, Marton K. Influence of phonotactic probability/neighbourhood density on lexical learning in late talker. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2013;48:188–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainela-Arnold E, Evans JL, Coady JA. Lexical representations in children with SLI: Evidence from a frequency manipulated gating task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2008;51:381–393. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/028). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainela-Arnold E, Evans J, Coady J. Beyond capacity limitations II: Effects of lexical processes on word recall in verbal working memory tasks in children with and without SLI. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010a;53(6):1656–1672. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/08-0240). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainela-Arnold E, Evans J, Coady J. Explaining lexical semantic deficits in specific language impairment: The role of phonological similarity, phonological working memory, and lexical competition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010b;53:1742–1756. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/08-0198). (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani N, Huettig F. Prediction during language processing is a piece of cake - but only for skilled producers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2012;38(4):843–847. doi: 10.1037/a0029284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather E, Plunkett K. Mutual exclusivity and phonological novelty constrain word learning at 16 months. Journal of Child Language. 2011;38:933–950. doi: 10.1017/S0305000910000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus IC. iMAP and iMAP2 produce erroneous statistical maps of eye-movement differences. Perception. 2013;42:1075–1084. doi: 10.1068/p7520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray B, Samelson VM, Lee SH, Tomblin JB. Eye-movements reveal the time-course of online spoken word recognition language impaired and normal adolescents. Cognitive Psychology. 2010;60:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miellet S, Lao J, Caldara R. An appropriate use of iMap produces correct statistical results: a reply to McManus (2013) iMAP and iMAP2 produce erroneous statistical maps of eye-movement differences. Perception. 2014;43:451–457. doi: 10.1068/p7682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgante JD, Zolfaghari R, Johnson SP. A critical test of temporal and spatial accuracy of the Tobii T60XL eye tracker. Infancy. 2012;17:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro N. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Sydney; Australia: 2007. The quality of word learning in children with specific language impairment. [Google Scholar]

- Nation K, Marshall C, Altmann G. Investigating individual differences in children’s real-time sentence comprehension using language-mediated eye movements. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2003;86:314–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting JB, Rice ML, Swank LK. Quick incidental learning (QUIL) of words by school-age children with and without SLI. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:434–445. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3802.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R. Clinical implications of the natural history of slow expressive language development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1996;5:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;46:360–371. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/028). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L, Dale P. Late Talkers: Language Development, Interventions, and Outcomes. Brookes Publishing Co; Baltimore, MD: 2013. pp. 169–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Buhr JC, Oetting JB. Specific-language-impaired children’s quick incidental learning of words: The effect of a pause. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:1040–1048. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3505.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer G, Plunkett K. Rapid Word Learning by Fifteen-Month-Olds in Tightly Controlled Conditions. Child Development. 1998;69:309–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SR Research . SR Research Experiment Builder. SR Research Ltd; Mississauga, Ontario, Canada: 2011. [Google Scholar]