INTRODUCTION

Granulomatosis with polyangitis (GPA) is an autoimmune disease that presents as granulomatosis and polyangitis affecting primarily the lower and upper respiratory tract and kidney. Up to 60% of GPA patients have otologic findings, including otitis media, hearing loss, vertigo and facial paralysis (1, 2). The most common pathological finding of GPA in the middle ear is granulation tissue characterized by hypertrophied submucosa with inflammatory cell infiltration (3). Granulation tissue is the primary cause of observed conductive hearing loss. The etiology of sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo and facial nerve paresis, in the absence of otic capsule or facial nerve invasion by granulation tissue is presumed to be secondary to vasculitis. In this paper, we investigate the presence of vasculitis in GPA in the temporal bone and its relation to audio-vestibular and facial nerve pathology.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Four cases with manifestations of vasculitis attributed to GPA were identified from the temporal bone collection. The temporal bones were removed at autopsy and processed for light microscopy. They were decalcified in EDTA and processed for celloidin embedding. Serial sectioning was performed in the axial plane at a thickness of 20 um, staining every tenth section with hematoxylin and eosin. All stained sections were examined under light microscopy. Graphic reconstruction of the cochlea was performed to quantify hair cells, the stria vascularis, and cochlear neuronal cells. All temporal bones were compared with normal age-matched controls.

RESULTS

Case I

Clinical History

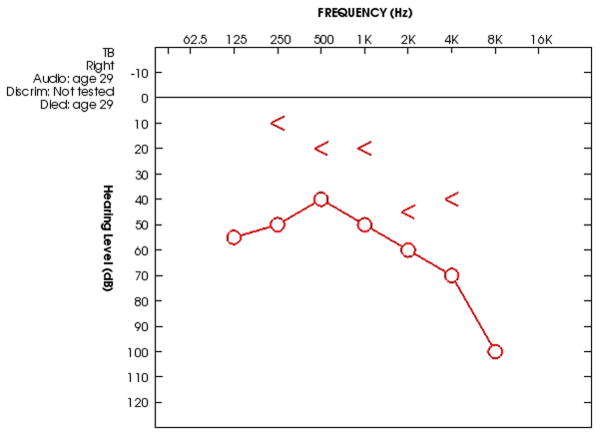

This 29 year old patient had GPA with tracheal, pulmonary and renal involvement and a positive C-ANCA serology. At the age of 29 the patient had acute otitis media on the right secondary to GPA associated granulomatosis. The patient underwent a myringotomy and was given antibiotic treatment. Within one week the patient developed an ipsilateral paralysis of the facial nerve and again underwent myringotomy. One month later the patient underwent a mastoidectomy. Serial audiograms showed mixed hearing loss in the right ear. An audiogram performed 1 week prior to death showed a persistent mixed hearing loss with a progressive sensorineural hearing loss above 2 KHz (Figure 1). The patient died 1 month after the mastoidectomy from pulmonary complications of GPA. The operative report with intra-operative findings was not available for review. There was no documented history of medical treatment (e.g. corticosteroids, immunosuppresants) for GPA prior to death.

Figure 1.

Audiogram of the right ear 1 week prior to death shows a mixed hearing loss

Histopathology

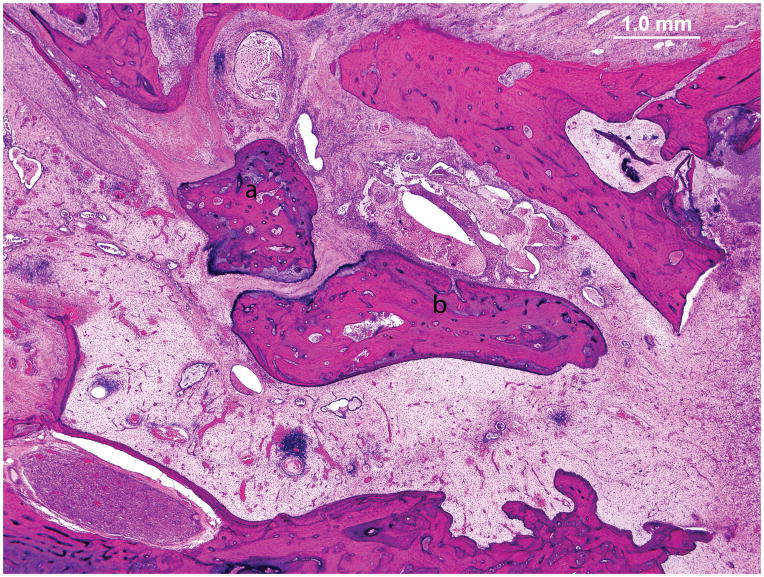

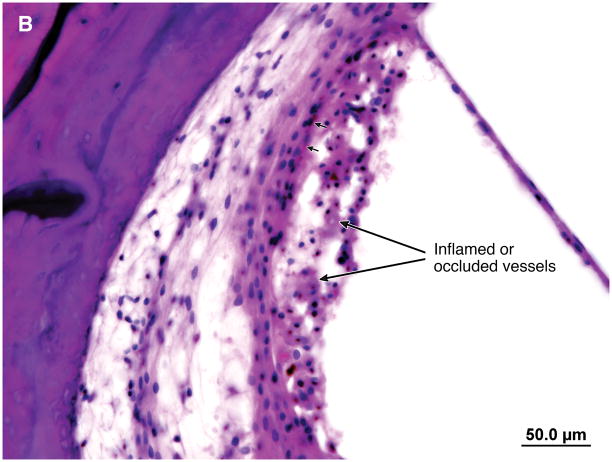

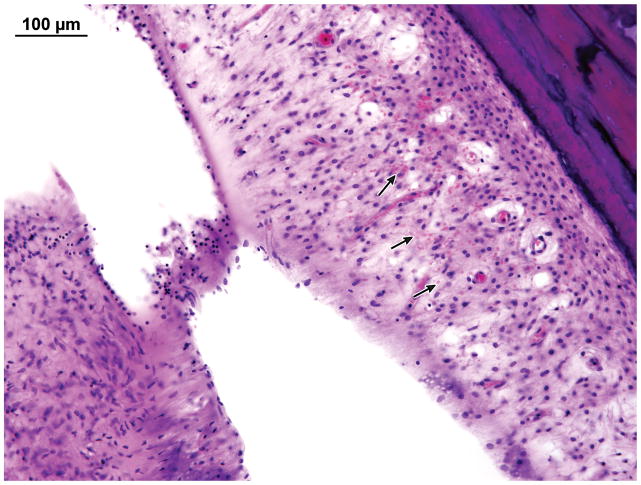

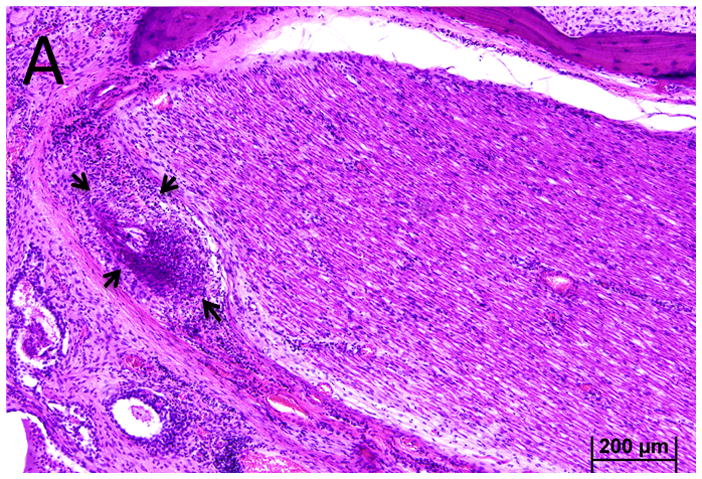

A wide mastoidectomy cavity was visible. The middle ear mucosa was thickened and edematous. Granulation tissue with fibrous stroma containing vascularized tissue and a lymphocytic infiltration filled the middle ear cleft (Figure 2). The Eustachian tube was occluded by granulation tissue. There was inflammation in the vasa nervorum of the intratemporal facial nerve. Distal to the vasculitis there was vacuolization of the vertical segment of the facial nerve (Figure 3). Vessels in the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament had thick walls and some were occluded (Figure 4). In the hook region of the cochlear duct there was hemorrhage and patchy necrosis in the spiral ligament (Figure 5). Hemorrhage was seen in the stroma of the crista of superior semicircular canal. Hemorrhage and inflammatory cells were identified in the vestibule.

Figure 2.

Case I. Photomicrograph of the right middle ear. There was granulation tissue filling the mesotympanum. The ossicles are anatomically intact but surrounded by inflammatory tissue. Malleus (a), Incus (b).

Figure 3.

Case I. A. The vasa nervorum in the proximal vertical segment of the facial nerve is occluded. There was a marked lymphocyte infiltration (arrows). B. Distal to the vasculitis there was vacuolization of the vertical segment of the facial nerve.

Figure 4.

Case I. A. The scala media in the basal turn of the cochlea. B. Vessels in the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament were thickened and in some instances occluded (arrows). Punctate areas of hemosiderin deposition suggest prior hemorrhage (arrow heads.)

Figure 5.

Case I. In the hook region of the cochlear duct there was hemorrhage. Arrows point to erythrocytes.

Case II

Clinical History

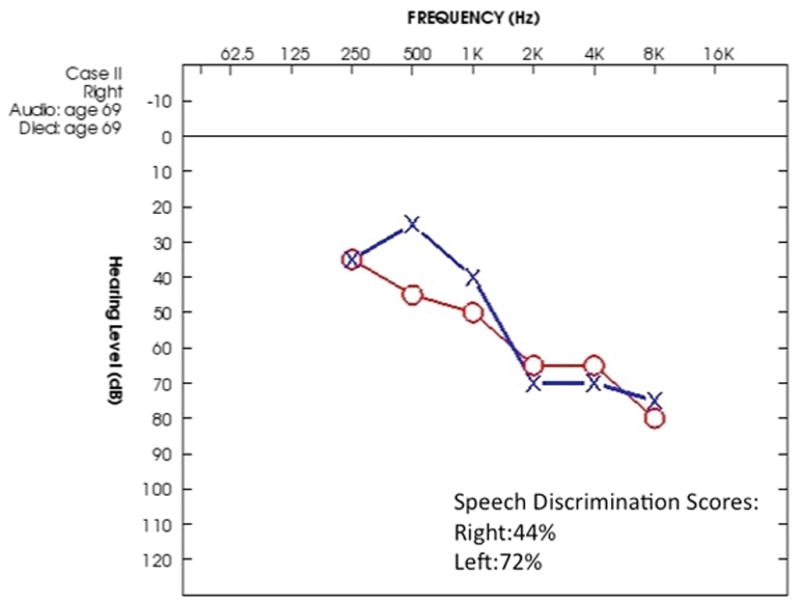

This 69-year-old patient developed nasal obstruction and bloody discharge from the right nostril. Granulation tissue was found on examination, and biopsy results were consistent with GPA. Ten days later, the patient had a severe vertiginous attack with spontaneous nystagmus. Vertiginous symptoms persisted for several days. The audiogram showed asymmetric bilateral down-sloping sensorineural hearing loss (Figure 6). The patient died six weeks after the vertiginous episode. She received no immunosuppressive therapy or corticosteroids prior to death.

Figure 6.

Case II. The audiogram shows an asymmetric down sloping sensorineural hearing loss with a more pronounced loss of speech discrimination on the right.

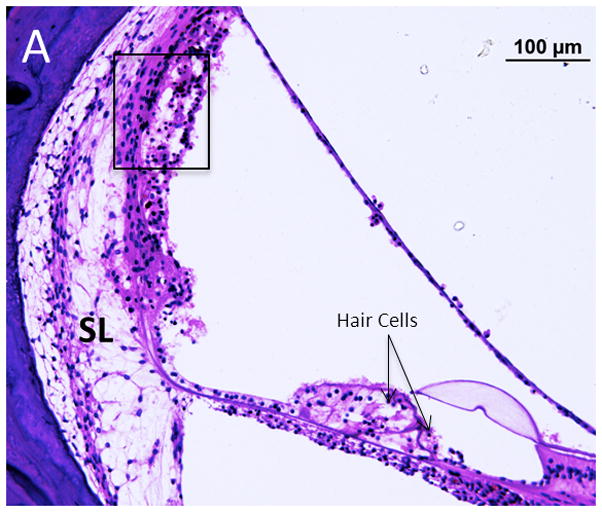

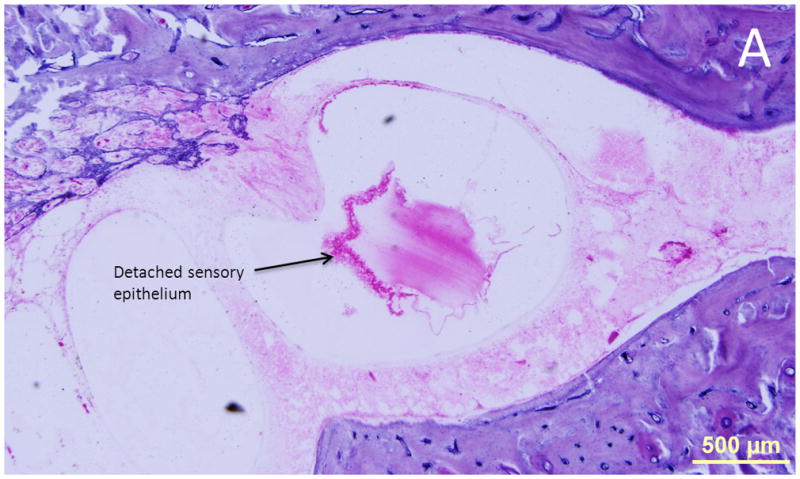

Histopathology

Findings were similar on both sides. There was mild to moderate loss of outer and inner hair cells in the apical and middle turns, and severe loss in the basal turn. The stria vascularis was unremarkable and the spiral ligament showed loss predominantly in the middle turn. The cochlear neuron population appeared normal when compared to age matched controls. The cristae of the superior and horizontal canals were degenerated on the right side, and the sensory epithelium and cupula were detached from the crista on the right side as well (Figure 7.) There was loss of dendrites in the crista of the canals. The ampulla of the posterior canal was partially collapsed, and the cupula was separated from the crista. The sensory epithelium, however, appeared normal. There were areas of hemorrhage in the perilymphatic spaces of the vestibule. Pigmented macrophages were seen in the vestibular epithelium and the perilymphatic space. The maculae of utricle and saccule appeared normal. On the left side, the vestibular organs appeared normal.

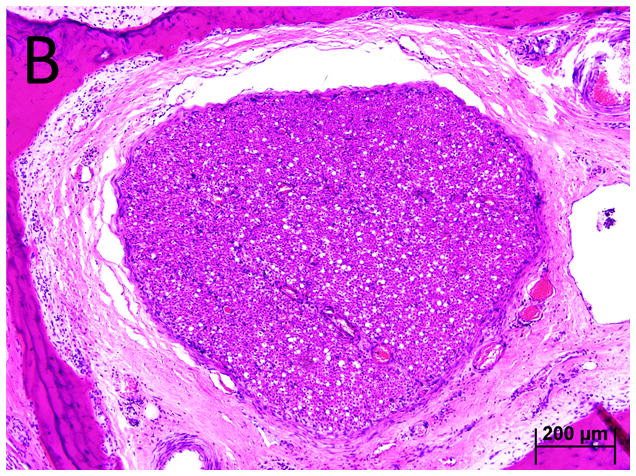

Figure 7.

Case II. There was ischemic necrosis of the lateral crista with detached sensory epithelium and cupula. These changes are attributable to ischemia in the distribution of the ampullary branch of the anterior vestibular artery (not shown.)

Case III

Clinical History

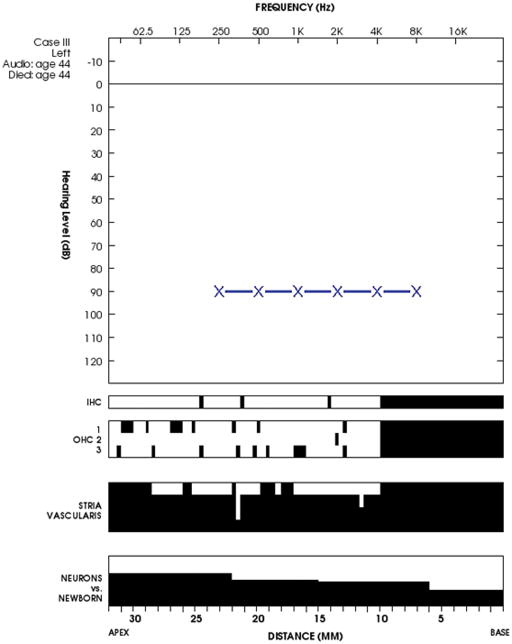

This patient presented with symptoms of nasal obstruction and bilateral hearing loss at the age of 44. The patient had bilateral purulent otorrhea, perforation of the tympanic membranes and bilateral severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss. She was diagnosed with GPA and received prednisolone and cyclophosphamide. An audiogram 3 months later showed significantly improved bone thresholds though a mixed hearing loss persisted in both ears. An audiogram 6 months before death showed a severe to profound loss in both ears (Figure 8.) She died of respiratory failure 7 months after the onset of her disease.

Figure 8.

Audiocytocochleogram for case III. There is a severe sensorineural hearing loss prior to death. Speech discrimination scores were not available. In the cytocochleogram black bars indicate loss. Overall the hair cells and spiral ganglion cells are well preserved with predominant loss of the stria vascularis.

Histopathology

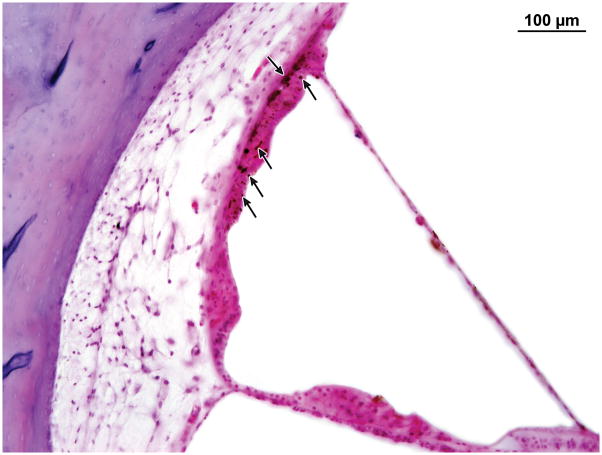

Left Ear: There was granulation tissue in the middle ear characterized by fibrous tissue, monocytes and lymphocytes. The cytologic elements of the organ of corti and vestibular organs were present in normal numbers. Hemosiderin deposition was found in the stria vascularis of all turns of the cochlea which can be considered as evidence of a vascular/hemorrhagic cause of her sensorineural hearing loss (Figure 9). The internal auditory canal was unremarkable. The labyrinthine artery was patent. The neuronal cell population was normal in number in the geniculate and Scarpa’s ganglia.

Figure 9.

Case III. Hemosiderin deposition (arrow heads) in the stria vascularis.

Case IV

Clinical History

At the age of 35 this patient developed acute otitis media. His symptoms worsened and he began to have arthralgias and epistaxis. An audiogram at the age of 36 revealed Right> Left conductive hearing loss. The patient underwent tympanostomy tube placement for serous effusions. There was no history of facial paralysis. The patient died of renal failure at the age of 36. There was no documented history of the patient having received corticosteroids or immunosuppresive therapy.

Histopathology

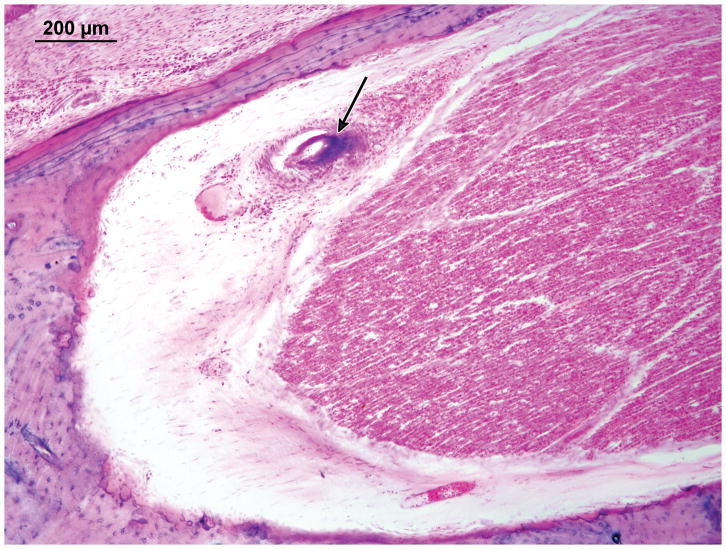

Right Ear: There was granulation tissue in the middle ear with thickened mucosa, fibrous stroma and a lymphocytic infiltrate. Outer hair cells and inner hair cells were well preserved. The vestibular epithelium was well preserved. The primary finding of interest was vasculitis within the fallopian canal in the tympanic segment of the facial nerve (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Case IV. Vasculitis (arrow) of the vasa nervorum in the tympanic segment of the facial nerve.

DISCUSSION

Granulomatosis with polyangitis (GPA), is an autoimmune condition that presents as small vessel vasculitis and inflammation of granulomatous and necrotizing character. GPA has two distinct pathologies—interstitial granulomatosis and vasculitis. Vasculitis in GPA involves small vessels, arterioles, capillaries and venules. Serine proteinase 3 (PR3) is the major autoantigen thought to be involved in the vasculitis. PR3 is translocated from granules in neutrophils to the membrane under the influence of cytokines, such as TNF alpha, making them available for PR3 ANCA binding. These neutrophils then release pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteases and reactive oxygen species that lead to vascular damage by direct cytotoxicity to vessel endothelial cells. When the vasculitis is necrotizing, as occurs in diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, it may only be detected indirectly by evidence of hemorrhage (4).

In our study, in addition to granulation tissue in the middle ear, we observed evidence of vasculitis in the cochlea, vestibule and facial nerve. We observed capillary occlusion with thickened walls in the stria vascularis and spiral ligament. Hemorrhage was evident in the spiral ligament and within the vestibule consistent with patterns of necrotizing vasculitis observed in the lungs. Vasculitis was also seen in the vasa nervorum of the intratemporal facial nerve with and without the clinical correlation of facial paresis. Hemorrhage within the cochlea and inflammatory changes in the vasa nervorum of the facial nerve have also been observed in other autoimmune conditions including systemic lupus erythematosus and polyarteritis nodosa (5,6.) The summary of findings is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Findings

| Case | Age at Death | Gender | Determinants of GPA Diagnosis | Non otologic organ involvement | Location of granulomatosis in temporal bone | Location of vasculitisin temporal bone | Hearing loss | Vertigo | Facial Paresis | Medical Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 29 | M | Mastoid biopsy and C-ANCA serology | Tracheal, pulmonary, renal | Middle ear Eustachian tube, and Mastoid | Facial nerve, cochlea, semicircular canals and vestibule | Mixed | Not recorded (NR) | Yes | None |

| II | 69 | F | Nasal biopsy | Nasal, renal | No | Semicircular canals | Sensorineural | Yes | No | None |

| III | 44 | F | Lung biopsy | Pulmonary | Middle ear | Cochlea | Mixed progressing to severe sensorineural | NR | NR | Cyclophosphamide and Prednisolone |

| IV | 35 | M | Nasal biopsy | Nasal, renal | Middle Ear | Facial nerve | Conductive | NR | No | None |

While most hearing loss in GPA is mixed, the incidence of sensorineural hearing loss has been reported to be as high as 47%. The hearing loss if detected early, can be reversed with immunosuppressive treatment (2,6,7) and is presumed to be the result of vasculitis. Several lines of evidence support the role of vasculitis in some patterns of hearing loss. In 1982, Kornblut, Wolff, and Fauci described a group of 60 patients with GPA, 45% of which had otologic manifestations (9). The audiometric pattern identified was a predominantly flat configuration. A flat pattern might be predicted by a vasculitis that affects the capillary bed of the stria vascularis as seen in strial presbycusis. Hearing loss in other forms of immune mediated vasculitis, such as Takayasu’s arteritis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis (EGPA) and polyarteritis nodosa, is known to occur. Moreover, a reduction in the endocochlear potential is correlated with ABR threshold elevation in autoimmune mouse models (10) in which the stria vascularis is affected. These findings would suggest that the vascular changes we observe in the stria vascularis may account at least in part for the potentially reversible sensorineural hearing loss in GPA.

Evidence for a vasculitis mediated vestibulopathy was identified in two of the four cases where there was hemorrhage within the vestibule. Only case II had clear documentation of vestibular symptoms that were acute in onset. The pathology in the vestibule shared similar features to the lateral cochlear wall suggestive of a hemorrhagic necrosis. Unlike the cochlear findings however, the vestibule had mild PMNs infiltration that we presume to be a reaction to the hemorrhage. The normal appearance of the utricule, saccule and posterior canal sensory epithelium and vestibular neurons also suggest that these changes were related to acute hemorrhage rather than neuropathy.

In addition to inner ear findings, we found vasculitis involving the vasa nervorum of the facial nerve that may result in facial paresis. Cranial nerve palsies in patients with GPA may be the result of granulomatous mass formation involving the nerve or result from vasculitis of the vasa nervorum in the generalized disease stage (10). Facial nerve involvement has been reported in 8% to 10% of reported patients although usually associated with otitis media (11,12).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we described the histopathology of the temporal bone in four individuals with GPA. Hemorrhage, changes in vessel caliber and lymphocytic infiltration characterized the vasculitis of granulomatosis with polyangitis in the temporal bone. These findings can be correlated to sensorineural hearing loss, vestibulopathy and facial nerve paresis observed in this condition.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Garyfallia Pagonis and Jennifer T. O’Malley for technical assistance. We would like to thank Victor Chobrok M.D., PhD of Regional Hospital Pardubice, Czech Republic and Iwao Ohtani, M.D. of Fukushima Medical College, Japan for providing specimens for this study.

Supported in part by NIH grant 1U24DC011943-01

Contributor Information

Felipe Santos, Department of Otolaryngology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Otology and Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Mehti Salviz, Department of Otolaryngology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Otology and Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Haris Domond, Department of Otolaryngology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Otology and Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Joseph B. Nadol, Department of Otolaryngology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Otology and Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

References

- 1.Takagi D, Nakamaru Y, Maguchi S, Furuta Y, Fukuda S. Otologic Manifestations of Wegener’s Granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1684–1690. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200209000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakthavachalam S, Driver MS, Cox C, Spiegel JH, Grundfast KM, Merkel PA. Hearing loss in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Otol Neurotol. 2004;5:833–7. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200409000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merchant SN, Nadol JB Jr, editors. Schuknecht’s Pathology of the Ear. 3. People’s Medical Publishing; House-USA, Shelton, Connecticut: 2010. p. 942. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis WD, Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Surgical pathology of the lung in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Review of 87 open lung biopsies from 67 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:315–33. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon TH, Paparella MM, Schachern PA. Systemic vasculitis: a temporal bone histopathologic study. Laryngoscope. 1989 Jun;99(6 Pt 1):600–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joglekar S, Deroee AF, Morita N, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Paparella M. Polyarteritis nodosa: a human temporal bone study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010 Jul-Aug;31(4):221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lidar M, Carmel E, Kronenberg Y, Langevitz P. Hearing loss as the presenting feature of systemic vasculitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Jun;1107:136–41. doi: 10.1196/annals.1381.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamazaki H, Fujiwara K, Shinohara S, Kikuchi M, Kanazawa Y, Kurihara R, Kishimoto I, Naito Y. Reversible cochlear disorders with normal vestibular functions in three cases with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:236–40. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornblut AD, Wolff SM, Fauci AS. Ear disease in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 1982;92(7 Pt 1):713–7. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruckenstein MJ. Autoimmune inner ear disease. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:426–30. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000136101.95662.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holle JU, Gross WL. Neurological involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(1):7–11. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834115f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald TJ, DeRemee RA. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:220–231. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198302000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]