Abstract

Gustatory cortex (GC) is widely regarded for its integral role in the acquisition and retention of conditioned taste aversions (CTAs) in rodents, but large lesions in this area do not always result in CTA impairment. Recently, using a new lesion mapping system, we found severe CTA expression deficits were associated with damage to a critical zone that included the posterior half of GC in addition to the insular cortex (IC) that is just dorsal and caudal to this region (visceral cortex). Importantly, lesions in anterior GC were without effect. Here, neurotoxic-induced bilateral lesions were placed in the anterior half of this critical damage zone, at the confluence of the posterior GC and the anterior visceral cortex (termed IC2), the posterior half of this critical damage zone that contains just VC (termed IC3), or both of these subregions (IC2+IC3). Then, pre- and post-surgically acquired CTAs (to 0.1M NaCl and 0.1M sucrose, respectively) were assessed postsurgically in 15-min single-bottle and 96-h two-bottle tests. Li-injected rats with histologically-confirmed bilateral lesions in IC2 exhibited the most severe CTA deficits, while those with bilateral lesions in IC3 were relatively normal, exhibiting transient disruptions in the single-bottle sessions. Group-wise lesion maps showed CTA-impaired rats had more extensive damage to IC2 than did unimpaired rats. Some individual differences in CTA expression among individual rats with similar lesion profiles were observed, suggesting idiosyncrasies in the topographical representation of information in IC. Nevertheless, this study implicates IC2 as the critical zone of IC for normal CTA expression.

Keywords: gustatory cortex, visceral cortex, brain mapping, taste learning

Graphical Abstract

Bilateral ibotenic-acid lesions were targeted to the area of insular cortex (IC) where gustatory cortex (GC) and visceral cortex (VC) are conjoined (in IC2) and/or the area of VC just posterior to that (in IC3). Rats IMPAIRED on postsurgical conditioned taste aversion (CTA) expression tests had significantly more damage in IC2 than UNIMPAIRED rats. Damage to IC3 was not associated with CTA deficits.

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral taste receptors are often considered the gatekeepers of the alimentary tract, transducing the primary signals that critically guide the selection of nutritious foods and fluids, over potentially toxic ones. The functional utility of these signals, however, depends, in large part, on their higher order integration with other visceral information. That is, incoming taste signals must be processed in context, checked against current nutritional need states, and linked in memory to their consequent postingestive effects. Yet while a great deal has been gleaned about peripheral mechanisms of taste signal transduction, comparatively little is known about how these signals are then centrally processed to garner functional significance.

The insular cortex (IC) is of particular interest in this regard. First, IC comprises a region of taste-responsive neurons in its agranular and dysgranular subdivisions between +0.2 mm and +2.3 mm anterior to bregma (see Figure 1), collectively called the gustatory cortex (GC) (Kosar et al, 1986a; Cechetto and Saper, 1987; Hanamori et al, 1998; but see Yamamoto et al, 1984; Ogawa et al, 1990). GC receives direct sensory input from the thalamus, but is reciprocally connected with limbic structures as well (Norgren and Leonard, 1973; Norgren, 1975; Norgren and Wolf, 1975; Kosar et al, 1986b; Allen et al, 1991; Saper, 1982; Shi and Cassell, 1998; Katz et al, 2001; Reynolds and Zahm, 2005; Maffei et al, 2012). Just dorsal and caudal to the posterior end of GC is a region of IC that responds to various types of visceral stimulation (Cechetto and Saper, 1987, Allen et al, 1991; Hanamori et al, 1998). This putative visceral cortex (VC) sends and receives projections to the nearby GC, but little is known about the functions to which these signals contribute (Krushel and van Der Kooy, 1988; Allen et al, 1991). The IC is generally considered a substrate for multisensory integration and the proximity of GC and VC, as well as their respective connections to other central circuits involved in sensory and motivational processing, makes this region of IC an ideal candidate as a functional conduit for taste-visceral integration. The relative approximate locations of the gustatory and visceral cortices in IC are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of a lateral view of insular cortex (IC), subdivided into three AP zones referenced in the present study (right), coupled with four representative coronal sections of IC on the left. The approximated areas conventionally considered gustatory cortex (GC) and visceral cortex (VC) are marked with blue and red hatched lines, respectively. The anterior half of GC is conventionally considered to be located in AI and DI (above the rhinal fissure) in IC1. The posterior portion of GC is conventionally considered to be located in AI and DI (above the rhinal fissure) in IC2. The anterior portion of VC is primarily located in GI in IC2. The posterior portion of VC is conventionally considered to be located in DI/GI in IC3. Solid black vertical lines demark the AP borders of these three zones on the lateral surface view. All zones include AI, DI, and GI, above the rhinal fissure. For purposes of visualizing and quantifying lesion damage in IC, the IC and the surrounding area were mapped onto a 2-D lesion mapping grid. A detailed description of how these maps were derived is included in the Materials and Methods section of this paper. Briefly, as illustrated on the 1.2 mm AP plate, the region of interest is divided into five major dorsoventral (DV) subsections and five major mediolateral (ML) subsections, comprising a grid. The DV subsections are plotted in the five major columns of the 2-D mapping grid, and the ML subsections are plotted in five subcolumns within each of the DV columns, as shown to the left of the plates. Within each particular cell or subregion of the superimposed grid, if less than one-half the area was destroyed, then a lesion score of 0 was assigned. If at least one-half of the neuronal tissue was destroyed, then a lesion score of 0.5 was assigned. If all of the neuronal tissue was destroyed, then a lesion score of 1 was assigned. Each serial 50 micron coronal section was mapped this way into each successive row in the lesion mapping grid. Other Abbreviations: AI, agranular insular cortex; AP, anteroposterior; D, dorsal; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; GI, granular insular cortex; IC, insular cortex; L, lateral; M, medial; rf, rhinal fissure; V, ventral. Atlas plates used with permission (Paxinos and Watson, 2007).

Thus it is not surprising that GC has long been considered a critical substrate for conditioned taste aversion (CTA) retention and acquisition, a conclusion primarily derived from lesion- and pharmacologically-induced disruptions of the area (Yamamoto et al, 1980; Braun et al, 1982; Lasiter and Glanzman, 1982; Dunn and Everitt, 1988; Bermudez-Rattoni and McGaugh, 1991; Rosenblum et al, 1995; Naor and Dudai, 1996; Nerad et al, 1996; Rosenblum et al, 1997; Schafe and Bernstein, 1998; Cubero et al, 1999; Berman and Dudai, 2001; Fresquet et al, 2004; Roman and Reilly, 2007; Stehberg and Simon, 2011). CTA is a robust and well-studied form of taste-visceral integration, whereby the hedonic value of a taste stimulus changes as a consequence of it having been previously followed by an aversive visceral event (Garcia et al, 1955; Barker, Best, and Domjan, 1977). However, in contrast to much of the previous work, a recent study from our laboratory found that rats with large bilateral ibotenic acid– induced lesions that were well-centered in the conventionally defined GC failed to disrupt a presurgically-conditioned taste aversion to NaCl (Hashimoto et al., 2014). In an effort to further explore the basis for the lack of a GC lesion effect, we conducted another study in which rats had lesions bilaterally placed in either the anterior GC, posterior GC, or both (Schier et al., 2014). We once again found that, on average, expression of a presurgical CTA was not compromised in rats with extensive bilateral lesions to GC, when tested in single- and two-bottle tests after surgery. Nor was the group impaired in their ability to acquire and then subsequently express a second CTA after surgery, a negative result consistent with that reported by Geddes et al. (2008). Close inspection of the behaviors of individual rats did, however, reveal subsets of rats on each test that exhibited significant CTA deficits. To determine whether there were any specific commonalities in the lesion topographies of the rats that were impaired, we developed and applied a high-resolution lesion mapping system. This approach revealed that CTA-impaired rats commonly had more lesion damage to an area that encompassed the posterior half of GC and the surrounding IC than did rats that were unimpaired (see Figure 2). Lesion damage to the anterior half of the GC was not associated with CTA deficits. Thus, these studies suggested that the region of IC that includes the posterior GC and the putative VC was best associated with CTA deficits, but GC on the whole was not.

Figure 2.

Group-wise lesion maps replotted from our previous study (Schier et al, 2014) showing the average insular cortex lesion scores on 2-D lesion mapping grids in color scale for a group of rats (n=8) that exhibited significantly IMPAIRED postsurgical CTA expression in the last 48-h of a two-bottle preference test with the 0.1 M sucrose CS versus dH2O (left side), relative to the average lesion profiles for a group of rats (n=20) that were UNIMPAIRED on the same test (right side). Impairment was determined as preference scores ≥2.0 SD from the mean of the lithium chloride-injected SHAM group on this test. Comparison of the average lesion profiles of these two groups indicates a critical zone where damage was associated with CTA impairment, in the posterior portion of gustatory cortex (GC) and the surrounding area just dorsal and posterior to that (the putative visceral cortex, VC). The solid black horizontal lines demarcate the anterior border of GC (+2.3 mm), the approximate center of GC (+1.2 mm), the posterior border of GC (+0.2 mm), and the posterior border of VC (−0.8 mm), relative to bregma. The dashed gray horizontal lines at +3.0 and −1.8 mm provide additional AP reference points. A more detailed description of how these maps are derived is included in the Materials and Methods section of this paper. Abbreviations: A, Anterior; P, Posterior; AI, agranular insular cortex (dorsal to the rhinal fissure); D, dorsal to insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; GI, granular insular cortex; L, lateral; M, medial; V, ventral to rhinal fissure.

Incidentally, Blonde et al. (2015) also found that a group of rats with extensive bilateral lesions that conjointly encompassed the majority of the GC and the posterior region of IC identified by Schier et al. (2014) exhibited CTA deficits to a sucrose taste stimulus in a postsurgical brief-access test. These lesions also impeded NaCl and KCl taste sensitivity as assessed psychophysically in separate two-response operant tests and slowed the acquisition rate of a NaCl versus KCl taste discrimination, but these particular deficits were not correlated with the CTA deficits. It is important to note that the anatomical boundaries of GC and VC were largely mapped on the basis of tract tracing and passive responsiveness to stimulation (and often with anesthetized subjects), and thus are limited in functional scope. Taken together, the recent studies from our laboratory suggest that subregions of IC are likely organized with respect to function as well. Given that taste and visceral events are intimately linked in various ingestive behaviors (see Spector, 2000), it seems possible that there may be a region of insular cortex devoted to taste-visceral integration that defies such strict GC/VC boundaries. Thus, for the purposes of the present study, we have operationally subdivided the area of IC that encompasses these two cortices into 3 anterior-posterior (AP) zones, as outlined in Figure 1. The extent of lesion damage in IC1 (anterior GC) was not associated with CTA in our previous study. IC2 comprises the anterior portion of the critical zone of damage associated with CTA deficits and generally includes the juncture of GC and VC. IC3 is the posterior portion of the critical zone of damage associated CTA deficits and generally includes just the VC.

Our previous study provided a compelling association between a specific region of posterior IC and CTA deficits. It did not allow us, however, to discern whether bilateral lesions in this region are sufficient to interfere with CTA expression when the anterior GC (IC1) is left intact. Moreover, if indeed a complete lesion in IC1 is irrelevant, it is unclear whether it is necessary to destroy both IC2 and IC3 or if the true critical zone of damage leading to CTA deficits is located within yet a smaller subregion in this area of IC. Thus, in an effort to further probe the contributions of a selective region of IC to CTA expression, the present experiment targeted bilateral lesions to specifically encompass the entire IC2 and IC3 zones (i.e., our previously indicated critical brain site associated with CTA deficits), just the IC2 zone, or just the IC3 zone. Both the postsurgical retention and expression of a presurgically trained CTA and the acquisition and subsequent expression of a second postsurgically trained CTA were measured in short (15-min) single-bottle test sessions and longer term (96-h) two-bottle preference test sessions. The individual lesion topographies were then mapped using our high-resolution lesion mapping system. Commonalities in the lesion topographies of rats with significant CTA deficits were compared to those of rats that were unimpaired in order to more specifically pinpoint the putative critical zone of IC that must remain intact for normal expression of CTA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were singly housed in standard polycarbonate shoebox cages in a climate-controlled colony room on a 12:12 h light: dark schedule with ad libitum access to rodent chow (LabDiet, Purina Mills Inc.) and deionized water, except as noted in the Behavioral Procedures section below. The experiment was run in two consecutive phases (ns=59 and 30, respectively). All behavioral procedures and schedules were identical between the two phases. The included surgical groups, as well as the stereotaxic coordinates used to target ibotenic acid lesions to two specific zones of posterior insular cortex (IC2 and IC3), differed slightly between phases for reasons discussed in the Surgery section below. All rats in the first phase, including rats that underwent SHAM surgeries, were treated for pinworms (Ivermectin 0.2–0.4 mg/kg, sc, every ~3–6 days) throughout the course of the experiment. All experimental and surgical procedures were approved by the Florida State University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery

Following presurgical CTA training (described below), Li- and Na-injected groups were further subdivided into IC lesion placement groups. The surgical groups and corresponding stereotaxic coordinates are listed in Table 1. All surgeries were performed under isoflurane anesthesia (~5% induction rate, ~2–2.5% maintenance rate). Once at a surgical anesthetic plane, the rat was positioned in the stereotaxic apparatus with blunt ear bars (model 900, Kopf Instruments). The skull was then exposed through a midline incision in the overlying skin and muscle, such that bregma and lambda were visible. The skull was leveled at bregma and lambda by adjusting the bite bar. Small access holes were drilled through the skull just over the target sites. Using bregma as the reference point (0.0 mm), a glass micropipette tip (diameter ~40–50 µm) attached to a 1.0 µl Hamilton syringe containing ibotenic acid (IBO; 20 mg/ml in phosphate buffered saline, PBS, Tocris Bioscience) or just PBS (for SHAMs) was positioned at the designated stereotaxic coordinates (see Table 1). Then, the infusate was slowly administered in two microinfusions (i.e., two infusions of 0.05 ul for a total volume of 0.1 ul/site) or in a single microinfusion of 0.07 ul at each IC3 site in phase 2. Each microinfusion was separated by a period of approximately two minutes, during which the pipette was left in place to allow the infusate to diffuse into the tissue. After all infusions were administered, the midline incision was closed with wound clips. Rats were given postoperative analgesic (Carprofen, 5 mg/kg, sc) and antibiotic (Gentamicin, 8 mg/kg, sc) at the conclusion of the surgery and for three days thereafter. Rats were given at least 10 days (range: 10–33 days) to recover before postsurgical testing commenced.

Table 1.

CTA training groups, lesion groups, and stereotaxic coordinates.

| CTA GROUP/Ns | LESION GROUP/Ns | STEREOTAXIC TARGET COORDINATES+ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC2 | IC3 | |||||||||

| AP | ML | DV | Vol. (µl) |

AP | ML | DV | Vol. (µl) |

|||

| Li-injected (n=68) | SHAM IC2+IC3 (PBS) |

Phase 1 (n=8) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | ± 6.0 | −6.7 | 0.1 |

| Phase 2 (n/a) | N/A | N/A | ||||||||

| UNILATERAL^ IC2+IC3 (IBO) |

Phase 1 (n=9) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | ±6.0 | −6.7 | 0.1 | |

| Phase 2 (n=9) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.2 | ± 6.3 | −6.5 | 0.07 | ||

| −6.9 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| −0.6 | ±6.4 | −6.5 | 0.07 | |||||||

| −7.0 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| IC2* (IBO) |

Phase 1 (n=9) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | N/A | ||||

| Phase 2 (n/a) | N/A | N/A | ||||||||

| IC3* (IBO) |

Phase 1 (n=9) | N/A | −0.4 | ±6.0 | −6.7 | 0.1 | ||||

| Phase 2 (n=6) | N/A | −0.2 | ± 6.3 | −6.5 | 0.07 | |||||

| −6.9 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| −0.6 | ±6.4 | −6.5 | 0.07 | |||||||

| −7.0 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| BILAT IC2+IC3 (IBO) |

Phase 1 (n=9) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | ± 6.0 | −6.7 | 0.1 | |

| Phase 2 (n=6) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.2 | ± 6.3 | −6.5 | 0.07 | ||

| −6.9 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| −0.6 | ± 6.4 | −6.5 | 0.07 | |||||||

| −7.0 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| Na-injected (n=21) | SHAM IC2+IC3 (PBS) |

Phase 1 (n=7) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | ± 5.9 | −6.7 | 0.1 |

| Phase 2 (n/a) | N/A | N/A | ||||||||

| BILAT IC2+IC3 (IBO) |

Phase 1 (n=8) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | ± 6.0 | −6.7 | 0.1 | |

| Phase 2 (n=6) | +0.5 | ±5.9 | −6.8 | 0.1 | −0.2 | ± 6.3 | −6.5 | 0.07 | ||

| −6.9 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| −0.6 | ± 6.4 | −6.5 | 0.07 | |||||||

| −7.0 | 0.07 | |||||||||

Notes. Symbols: + all stereotaxic target coordinates were based on Paxinos and Watson (2007);

Unilateral lesions were made to one hemisphere, with left v. right hemisphere placement counterbalanced across rats;

The single target lesions was made in one hemisphere, and the double lesion was made in the alternative hemisphere with the corresponding IC2+IC3 target coordinates of the same phase (left v. right hemisphere placements counterbalanced across rats).

Abbreviations: CTA, conditioned taste aversion, Li, lithium chloride, Na, sodium chloride; IC, insular cortex; AP, anterior-posterior; ML, medial-lateral; DV, dorsal-ventral; Vol, volume; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; IBO, 20 mg/ml ibotenic acid in PBS; BILAT, bilateral.

To ensure that the selective single lesions targeted to IC2 or IC3 alone sufficiently destroyed corresponding areas in both hemispheres, all rats that were assigned to the single IC2 or IC3 lesion groups received that single lesion in one hemisphere, but received a double target lesion (IC2+IC3) to the alternative hemisphere. Left versus right hemisphere placement of the single and double target lesions was roughly balanced across individual rats within the same group. Lesion-hemisphere assignment was likewise counterbalanced across rats in the unilateral lesion group.

As mentioned above and shown in Table 1, the coordinates and IBO volumes used to target lesions to IC3 differed slightly between the two phases of the experiment. Because in the first phase the coordinates and infusion volumes for IC3 resulted in very limited to damage to IC3, especially with respect to sufficient DV spread, a different strategy was employed in phase 2. In particular, a total of four sites were targeted in IC3, including two AP sites, with two DV levels each. Although smaller IBO infusion volumes were used at each particular site compared to the first phase iteration, the greater number of infusion sites resulted in greater total volume of IBO targeted in IC3 for the second iteration. Coordinates and infusion volumes for IC2 were the same for both phases. It is important to stress that for the final analyses, rats were included in a particular lesion group on the basis of the histologically-confirmed size and location of the lesion, not the targeted surgery group (see below).

Behavioral Procedures

Two CTAs, each with a different taste conditioned stimulus (CS), were trained and tested in series. One CTA (CS: 0.1 M NaCl) was trained presurgically and tested postsurgically with a 15-min single-bottle intake test and a 96-h two-bottle choice test (v. dH2O). The second CTA (CS: 0.1 M sucrose) was both trained and tested postsurgically. Aside from the different CSs, the procedures used to train and test the two CTAs were identical. All training and testing took place in the homecage. All rats were placed on a restricted water-access schedule, in which deionized water (dH2O) was presented for 15 min each morning and for 30 min approximately 5 h later each afternoon (for 3–6 days, depending on phase). Intakes were measured to the nearest ml. Then, for CTA training, the CS was presented in place of water in the morning session. At the end of this session, the rat was injected with either 2 mEq LiCl (0.15 M, ip, Li-injected) to induce visceral malaise or an equal volume of 0.15 M NaCl (ip, Na-injected) to serve as an unconditioned control. Deionized water was presented as usual in the afternoon session. On the following two days, rats received dH2O in the morning and afternoon sessions. Then, the CS was presented again in the morning session followed by LiCl or NaCl injection for a second training trial. In order to help ensure all Li-injected rats received the comparable exposures to LiCl, and to maintain the association between the CS and the LiCl US, rats that failed to drink at least 1 ml of the CS on their own were orally administered 0.5 ml of the CS via 1 ml syringe immediately prior to the LiCl injection [for Trial 2 with the sucrose CS, this included one rat from the IC2+IC3-Li group, one rat from the IC2-Li group, three rats from the SHAM-Li group, and three rats from the UNI-Li group].

For CTA testing, rats were again placed on the restricted water-access schedule for 3 days as described above. The CS was presented in place of water for 15 min in the morning session. No LiCl or NaCl injections were made at the end of this single-bottle retention test. Instead, at the conclusion of the single-bottle retention test, two bottles were placed on the home-cage. One bottle contained the CS and the other bottle contained dH2O. At the end of each 24-h period, the amounts consumed from each bottle were measured, the bottles were refilled with fresh fluids, and the left/right position of the CS and dH2O were switched. This two-bottle choice test continued for four consecutive 24-h periods for a total of 96-h. Preference scores were calculated by dividing the total CS intake over the 96-h period by the total fluid intake (CS + dH2O) over the 96-h period.

Histology and Lesion Mapping

At the conclusion of behavioral testing, rats were euthanized by lethal overdose of Euthasol (sodium pentobarbital and sodium phenytoin, Virbac Corporation, Fort Worth, TX; ~150 mg/kg, ip) and transcardially perfused with heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M PBS) (PFA). Then, each skull was placed in a stereotaxic holder, leveled against bregma and lambda by adjusting the bite bar, and a small band of skull was removed parallel to and just anterior to the interaural line, exposing the fixed brain. A blade securely mounted in a stereotaxic probe holder was slowly guided in a dorsal to ventral motion across the ML plane. This type of blocking procedure was done in order to help ensure a uniform stereotaxic plane of section for each brain. The remainder of the skull was manually removed and the blocked brain was stored in 4% PFA until sectioning. Serial coronal sections (50 µm thick) were made on a vibratome. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, Nissl stained, and coverslipped. Then, each brain was examined section by section under a light microscope (Leica model DMRB, McBain Instruments) to map the lesion damage in insular cortex and the surrounding area (see below for details) or to confirm SHAM surgeries.

The lesion mapping system has been described in detail previously (Schier et al, 2014). Briefly, the insular cortex and surrounding area was plotted onto a 2-D grid (Excel, Microsoft Office), wherein each row represented a single 50 µm section and each column represented a subdivision of insular cortex (agranular, dorsal to the rhinal fissure, AI; dysgranular, DI; granular, GI; dorsal to granular, D; ventral to the rhinal fissure, V). Each of these dorsal to ventral cortical subdivisions was further divided into five medial to lateral subdivisions, represented in five subcolumns. In particular, these comprise the medial-lateral thirds of the cortical tissue, the claustrum, which runs just medial to IC, and the area just medial to that (i.e., medial to external capsule). Representative examples of these 2-D plots, one of a targeted IC2 lesion and one of a targeted IC3 lesion, are shown in Figure 4. Lesion damage in each subdivision was scored on a ternary scale, with 0 (or white) representing less than half of the subdivision with damage, 0.5 (yellow) representing more than half but less than complete damage to the subdivision, and 1 (or red) representing complete damage (no intact tissue) to the subdivision. The score was entered into the corresponding cell on the 2-D grid. The entire lesion was mapped onto this grid in this manner section by section (row by row). Because tissue shrinks with histological processing, a correction factor was used in order to put each 50 µm section in register with the stereotaxic atlas. However, the procedure used to make these calculations was modified from our previous one for two reasons. First, in the present study, many of the lesions extended beyond GC, where the local tissue characteristics appear to differentially respond to histological processing (i.e., less shrinkage). Second, the extent of shrinkage and relative distance between histological landmarks appeared to vary, sometimes considerably, across individual rats. Thus, here, a landmark-based registration procedure was adopted. Each brain was surveyed for a select set of standard histological landmarks across the AP span of the collected tissue (e.g., anterior start of the striatum, Cpu, joining of the corpus callosum, disappearance of the indusium grisium below the corpus callosum, rostral joining of the anterior commissure, emergence of the CA3 field in hippocampus, among others). Then, the number of sections between one landmark and the next landmark was counted and divided into the actual stereotaxic difference represented in the atlas (based on Paxinos and Watson, 2007), yielding a correction factor for each 50 µm section between those two particular landmarks. Thus, the relative “thickness” (AP distance) that a given section represented in the corresponding row on the mapping grid was determined by multiplying the section thickness (50 µm) by that local correction factor and the AP coordinate of the section (and corresponding row on the map grid) was estimated by its position relative to the two flanking landmarks.

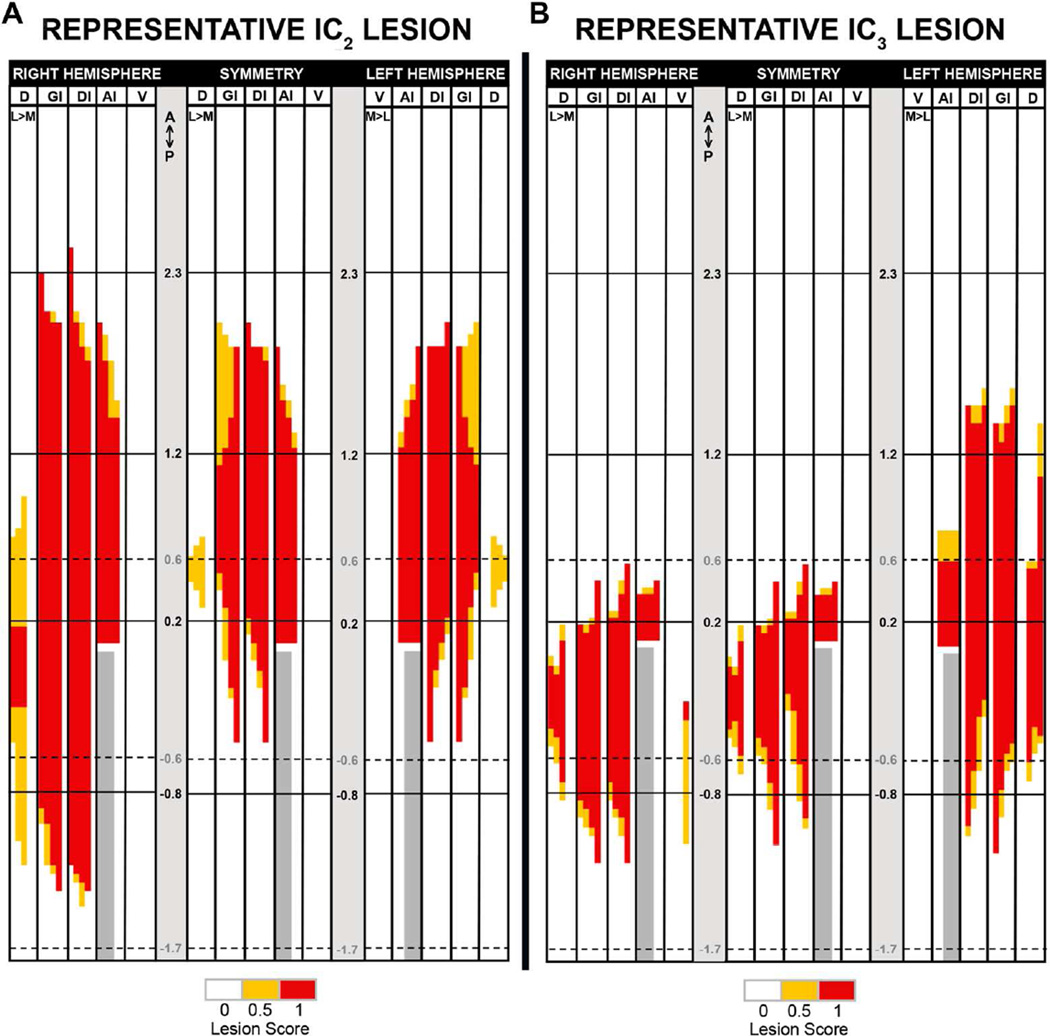

Figure 4.

Left and right hemisphere and symmetry lesion maps (viewed facing the front of brain) from the representative rat with a complete bilateral IC2 lesion (A) or IC3 lesion (B) from Figure 3. Solid lines indicate the 12.3, 11.2, 10.2, −0.8 mm AP levels relative to bregma. Dotted lines demark the AP levels for the corresponding representative photomicrographs at 10.6, −0.6, and −1.7 mm relative to bregma (presented in Fig. 3). Refer to Materials and Methods for more detailed descriptions of the definitions of the various IC subregions in the grid and lesion-mapping system. Briefly, the maps for each hemisphere were separately generated by scoring the lesion in each designated subregion of IC and the surrounding area in each serial section of tissue according to the legend (at bottom) as: no lesion (0, white), at least one-half lesion (0.5, yellow) or full lesion (1, red). Symmetry maps were generated by comparing the lesion score in each grid cell across the two hemispheres and assigning the lower of those two scores to the corresponding cell in the symmetry map. Ant, anterior; Pos, posterior; AI, agranular insular cortex (dorsal to the rhinal fissure); D, dorsal to insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; GI, granular insular cortex; L: lateral; M, medial; V, ventral to rhinal fissure; based on Paxinos and Watson (2007).

For each brain, after each hemisphere was separately mapped, a third map— referred to as a symmetry map—was generated by comparing the score in each cell among the two hemispheres, and assigning the lowest of those two scores to the corresponding cell in the symmetry map.

To compare lesion profiles across rats, the individual symmetry maps were then rendered to the same scale. To do this, for a given map, the total microns that each grid row represented along the AP axis (determined as described above) was first rounded to the nearest multiple of 10 (e.g., 73.2 microns to 70 microns) and then the row was further subdivided into 10 micron rows (i.e., 7 rows, in this example). In effect, this put each lesion map on the same 10-micron AP scale. The symmetry lesion maps of individual rats were aligned at these 10-micron AP coordinates for comparison.

For the purposes of this study, bilateral lesion scores were calculated by summing the lesion scores in the symmetry map for designated regions of interest. For rats with the unilateral lesions, lesion scores were calculated from the hemisphere map with lesion. Lesion scores calculated with this system have previously been validated against another tool commonly used to derive lesion volume (i.e., Neurolucida, see Schier et al., 2014 for a more detailed description). Total lesion score, lesion scores for particular subregions of interest, and proportions of those subregions of interest damaged (lesion score for subregion divided by total number of grid cells in subregion) were calculated for each rat. Group-wise average lesion scores were generated by averaging the scores in each corresponding cell across a selected group of individual symmetry maps (e.g., maps of rats with significant CTA deficits). The group-wise average lesion scores were rendered in color scale in the figures to best reveal the commonalities and differences in lesion topographies both within and among selected subsets of rats.

All verifications and lesion mappings were performed by an experimenter unaware of the intended lesion placement. One experimenter scored all of the lesions from phase 2 and approximately one-half of the lesions of phase 1, and a second experimenter scored the remaining half of the phase 1 lesions. Each experimenter scored roughly equal proportions of the phase 1 brains belonging to each of the experimental subgroups, and both experimenters scored three of the same test lesions/brains to assess inter-rater reliability. Pearson’s correlations were calculated to compare the lesion scores assigned in various randomly selected subdivisions from each of these three test brains across the two experimenters. This yielded an r of 0.95 (P < 0.0001), confirming good inter-rater reliability in this region of interest with this lesion mapping system.

Data Analyses

First, in a planned comparison, the Li-injected SHAM group was compared with the Li-injected UNI group at: each presurgical CTA acquisition trial with NaCl, the postsurgical test with NaCl, the postsurgical CTA acquisition trial with sucrose, and the postsurgical test with sucrose with independent Mann-Whitney U-tests. The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (B-H FDR) procedure was used to adjust for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). These tests revealed that Li-injected rats with unilateral lesions were no different than Li-injected SHAM controls on any of the behavioral trials and tests (closest p=0.007, on the postsurgical 96-h two-bottle test, with a q*-value of ≤0.006). Thus, these two groups were collapsed into one for all subsequent paired group-wise comparisons. Because the experimental design did not lend itself to a full factorial analysis, separate pair-wise independent Mann-Whitney U-tests were conducted between each experimental group for each CTA acquisition trial and test. Again, B-H FDR was used to adjust the cut-off value (q*-value) for the multiple comparisons conducted for each CTA trial or test set. For presentation purposes, all group medians + semi interquartile ranges (SIQRs) are shown in a single figure for each CTA trial or test.

In order to determine which areas of lesion was best associated with CTA deficits, individual lesion scores for each of the three designated IC zones, as well as the anterior-posterior halves of each of these zones, were calculated from each rat’s symmetry map. This analysis included all Li-injected rat with bilateral lesions, even those that did not meet the lesion criterion. It is important to keep in mind that these zones were derived on the basis of our previous study (Schier et al, 2014) to encompass specific subregions associated with CTA deficits; the anterior-posterior halves of each of these zones are simply that and were not guided by any chemotopic or cytoarchitectonic organization. Moreover, it is important to note that lesion scores were calculated from all three subdivisions of IC (AI, DI, and GI) above the rhinal fissure in each IC zone, unless specified otherwise; this includes the small strip of AI just below VC in the IC3 zone. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess associations between behavioral performance and lesion scores at each CTA trial/test. All p-values were compared against the corresponding B-H FDR adjusted q*-value.

In addition to the lesion group analysis, Li-injected rats with bilateral lesions were divided into two performance groups (IMPAIRED or UNIMPAIRED) for each CTA trial/test. Group assignment was determined by first calculating the 97.5 percentile intake or preference score from the SHAM-Li or UNI-Li group (UNI-Li or SHAM-Li) dataset for each CTA trial/test. Any rats that had greater than or equal intake volumes or preference scores than that criterion value were considered IMPAIRED; the remaining rats that had intake or preference scores below that value were considered UNIMPAIRED. The particular control group used for these designations was determined on a trial/test by trial/test basis as the Li-injected control group (SHAM-Li or UNI-Li) that had higher value at the 97.5 percentile level. The average overlap maps of these two groups were calculated and rendered in color scale for each CTA trial/test as described above. Independent Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed on the proportion of IC2 and IC3 damaged for groups of rats designated as IMPAIRED versus UNIMPAIRED for each CTA trial/test.

RESULTS

Lesions and Lesion Subtypes

In total, 24 rats were excluded from all analyses due to problems with the histological processing that rendered the tissue and/or lesion difficult to see or due to extremely small (or no) lesions (i.e., misses). Final group sizes are indicated in the figure captions. The remaining Li- injected rats were included for group-wise analyses if they had at least 50% bilateral lesions in IC2 and/or IC3 and were assigned to a particular lesion subgroup based on whether that damage was in IC2, IC3, or both (refer to Figure 1 for an approximated surface view of each of these IC zones). Median ± SIQR proportions of bilateral (symmetry) damage to IC2 and IC3 for each group of rats that met the ≥50% bilateral lesion are as follows: IC2+IC3-Li (IC2: 0.76 ± 0.02; IC3: 0.99 ± 0.07), IC2-Li (IC2: 0.72 ± 0.09; IC3: 0.20 ± 0.05), IC3-Li (IC2: 0.21 ± 0.14; IC3: 0.87 ± 0.08). Respective representative IC2 and IC3 lesions are shown in Figures 3 and 4. Li-injected rats with unilateral lesions (UNI IC-Li) were included if ≥ 50% of IC2 or IC3 was damaged in one hemisphere, without any lesion damage in the contralateral hemisphere. The median ± SIQR proportion of damage to IC2 was 0.73±0.18 and to IC3 was 0.995±0.13 for this UNI-Li group. Na-injected rats with ≥50% bilateral lesions in IC2 or IC3 were included for comparison as well (IC-Na group: IC2: 0.70 ± 0.17; IC3: 0.93 ± 0.05). In addition to this primary damage in IC, that generally included all three layers (AI, GI, and DI), almost all of the lesions damaged the adjacent claustrum and most of these lesions also extended a little dorsal to the local IC subregion. In a few cases, there was some damage that spread ventrally beyond the rhinal fissure, though this was usually minimal.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of the left and right hemispheres along the AP extent of the regions of interest in a representative IC2 lesion (A) and IC3 lesion (B). Solid black arrowheads indicate the borders of the lesion. The rat with the IC2 lesion shown here was significantly impaired on all CTA tests, while the rat with the IC3 lesion shown here was not impaired on any test. The corresponding grid maps from these representative lesions are displayed in Figure 4. All photomicrographs were rendered to grayscale, put on a white background, and the brightness and contrast were globally adjusted in Photoshop for presentation purposes. (Scale bar: 1.0 mm.)

Group-wise Postsurgical Expression of a Presurgically Trained CTA to NaCl

Prior to the surgery, all included groups consumed comparable amounts of the 0.1 M NaCl CS on the first acquisition trial (Figure 5, top panel, all ps ≥ 0.02, q*-value of 0.003). On the second trial, all Li-injected groups significantly reduced their intakes relative to the Na-injected groups (all ps ≤ 0.003, q*-value =0.03). No differences were found among the Li-injected groups or among the Na-injected groups (ps ≥ 0.26, q*-value = 0.03).

Figure 5.

Median + SIQR 0.1 M NaCl intake on Trials 1 and 2 of presurgical CTA training (A, top panel), postsurgical 15-min single-bottle retention test (B, middle panel), and postsurgical 96-h two-bottle preference test (C, bottom panel) for Li-injected rats that met the lesion criterion (≥50% bilateral lesion) in IC2 (n=9), IC3 (n=9), or IC2+IC3 (n=6), Li-injected rats that met the lesion criterion in one hemisphere, unilateral control (UNI, n=13), Li-injected rats in the SHAM-operated control group (n=8), Na-injected rats that met the lesion criterion in IC (n=10) or served as SHAM-operated controls (n=7). Symbols within each of the three Li-injected lesion plots represent individual rats. A rat is represented by the same symbol in each of the three panels. Dashed line represents the IMPAIRED v. UNIMPARED cutoff value as derived from the Li-injected control group (97.5 percentile).

Table 2 presents pair-wise group comparisons on the two postsurgical tests with the NaCl CS. On the 15-min single-bottle test, all three Li-injected lesion groups consumed significantly more NaCl than did the Li-injected control group (UNI IC-Li + SHAM-Li; Figure 5, middle panel). Even so, these intake levels were still generally lower, though in some cases not statistically so, than that of the two Na-injected groups. When the NaCl CS was subsequently pitted against dH2O in the 96-h two-bottle test, the Li-injected control groups (UNI IC-Li and SHAM-Li) continued to avoid the NaCl CS. Interestingly, the IC3-Li group also exhibited strong avoidance of the NaCl CS on this test (not significantly different from Li-injected controls). Conversely, the IC2-Li and IC2+IC3-Li groups continued to fail to completely avoid the NaCl CS in the two-bottle test as compared to the Li-injected controls. In fact, these preference scores were on par with that of the two Na-injected groups (Figure 5, bottom panel).

Table 2.

Group-wise comparisons on tests of postsurgical expression of a presurgically-trained CTA.

| CS: 0.1 M NaCl, 15-MIN SINGLE BOTTLE TEST, q* = 0.02 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-Na | IC2+IC3−Li | IC2−Li | IC3−Li | UNI IC-Li+ SHAM-Li |

SHAM-Na | |

| IC-Na | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.007 | 0.00001 | 0.35 | |

| IC2+IC3−Li | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.001 | 0.10 | ||

| IC2−Li | 0.79 | 0.007 | 0.07 | |||

| IC3−Li | 0.003 | 0.04 | ||||

|

UNI-Li+ SHAM-Li |

0.0001 | |||||

| SHAM-Na | ||||||

| CS: 0.1 M NaCl, 96-H TWO-BOTTLE TEST, q* = 0.02 | ||||||

| IC-Na | IC2+IC3−Li | IC2−Li | IC3−Li |

UNI IC-Li+ SHAM-Li |

SHAM-Na | |

| IC-Na | 0.18 | 0.84 | 0.008 | 0.00003 | 0.53 | |

| IC2+IC3−Li | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.002 | 0.05 | ||

| IC2−Li | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.60 | |||

| IC3−Li | 0.16 | 0.008 | ||||

|

UNI IC-Li+ SHAM-Li |

0.0002 | |||||

| SHAM-Na | ||||||

Values are p-values from Mann-Whitney U-tests. Bolded and italicized values are statistically significant after B-H FDR adjustment (q-value) for multiple comparisons. Insular cortex zones are outlined in Figure 1.

Abbreviations: IC, Insular Cortex; Li, Lithium chloride injected group; Na, Sodium chloride injected group; UNI, unilateral.

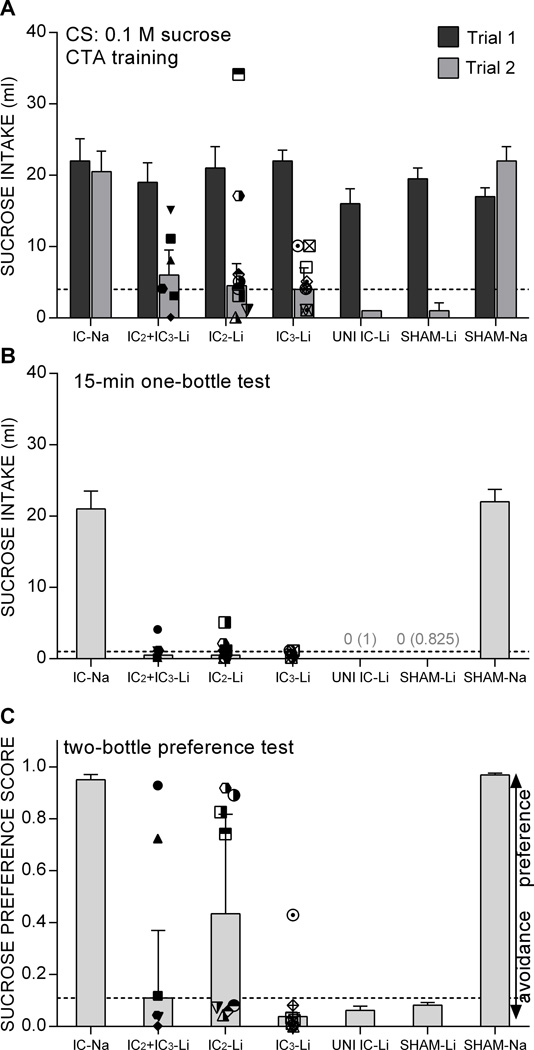

Group-wise Comparisons of Postsurgical Acquisition and Expression of a Postsurgically Trained CTA to sucrose

All groups consumed comparable amounts of 0.1 M sucrose on the first acquisition trial (Figure 6, top panel, all ps ≥ 0.01 with q* value ≤ 0.003). Table 3 presents pair-wise group comparisons for the second trial of acquisition and the subsequent tests. As expected, the Li-injected control groups significantly reduced CS intake on Trial 2, relative to the Na-injected control groups. The IC3-Li group likewise significantly suppressed CS intake, relative to the Na-injected controls, as did the IC2+IC3-Li group. The IC2-Li group significantly suppressed CS intake on Trial 2 compared to the SHAM-Na control group, but not the IC-Na control group. That said, CS intake for all three Li-injected bilateral lesion groups was significantly greater than that of the SHAM+UNI IC-LI control group. Nevertheless, after the second CS-LiCl pairing (Trial 2), even the IC2-Li group almost completely avoided the sucrose CS in the 15-min single-bottle test (Figure 6, middle panel). Then, in the two-bottle preference test, while the Li-injected control group and the IC3-Li group continued to avoid the sucrose CS, the IC2-Li group had a significantly higher preference for the sucrose CS. At the same time, this preference in the IC2-Li group was not completely reversed to the level of the Na-injected groups’ (Figure 6, lower panel). The IC2+IC3-Li group showed a CS preference that was intermediary to that of the Li-injected controls and IC3-Li groups and the IC2-Li group.

Figure 6.

Median + SIQR 0.1 M sucrose intake on Trials 1 and 2 of postsurgical CTA training (A, top panel), 15-min single-bottle retention test (B, middle panel), and 96-h two-bottle preference test (C, bottom panel) for Li-injected rats that met the lesion criterion (≥50% bilateral lesion) in IC2 (n=8), IC3 (n=9), or IC2+IC3 (n=6), Li-injected rats that met the lesion criterion in one hemisphere, unilateral control (UNI, n=13), Li-injected rats in the SHAM-operated control group (n=8), Na-injected rats that met the lesion criterion in IC (n=10) or served as SHAM-operated controls (n=7). Symbols within each of the three Li-injected lesion plots represent individual rats. A rat is represented by the same symbol in each of the three panels. Dashed line represents the IMPAIRED v. UNIMPARED cutoff value as derived from the Li-injected control group (97.5 percentile). Gray text in panel B indicates the median (SIQR) for the UNI-Li and SHAM-Li groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Group-wise comparisons on tests of postsurgical CTA acquisition and expression.

| CS: 0.1M SUCROSE, CTA TRIAL 2, q* = 0.03 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-Na | IC2+IC3−Li | IC2−Li | IC3−Li | UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

SHAM-Na | |

| IC-Na | 0.009 | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.00002 | 0.28 | |

| IC2+IC3−Li | 1.0 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.003 | ||

| IC2−Li | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |||

| IC3−Li | 0.007 | 0.001 | ||||

|

UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

0.0001 | |||||

| SHAM-Na | ||||||

| CS: 0.1M SUCROSE, 15-MIN SINGLE-BOTTLE TEST, q* = 0.03 | ||||||

| IC-Na | IC2+IC3−Li | IC2−Li | IC3−Li |

UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

SHAM-Na | |

| IC-Na | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.00001 | 0.53 | |

| IC2+IC3−Li | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.003 | ||

| IC2−Li | 0.59 | 0.15 | 0.001 | |||

| IC3−Li | 0.29 | 0.001 | ||||

|

UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

0.0001 | |||||

| SHAM-Na | ||||||

| CS: 0.1M SUCROSE, 96-HR TWO-BOTTLE TEST, q* = 0.03 | ||||||

| IC-Na | IC2+IC3−Li | IC2−Li | IC3−Li |

UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

SHAM-Na | |

| IC-Na | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | 0.00001 | 0.31 | |

| IC2+IC3−Li | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.003 | ||

| IC2−Li | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| IC3−Li | 0.23 | 0.001 | ||||

|

UNI IC-Li +SHAM-Li |

0.0001 | |||||

| SHAM-Na | ||||||

Values are p-values from Mann-Whitney U-tests. Bolded and italicized values are statistically significant after B-H FDR adjustment (q-value) for multiple comparisons. Insular cortex zones are outlined in Figure 1.

Abbreviations: IC, Insular Cortex; Li, Lithium chloride injected group; Na, Sodium chloride injected group; UNI, unilateral.

Characteristics of the Lesions in Posterior Insular Cortex Best Associated with CTA Expression Deficits

The group-wise data above suggest that lesions in the posterior insular cortex that are principally located in the IC2 zone—which putatively includes both the posterior GC and anterior VC (see Figure 1)—produce significant impairments in the postsurgical expressions of presurgically and postsurgically trained CTAs. Indeed, survey of the behaviors of the individual rats in each of the three Li-injected lesion groups also confirmed that the IC2-Li and IC2+IC3-Li groups had the greatest proportions of rats with persistent and profound impairments across the CTA trials/tests, with perhaps the exception of the 15-min single-bottle test. However, this survey also revealed that (a) not all the rats with categorized extensive damage in IC2 were impaired and (b) some rats with lesion limited to IC3 were somewhat impaired, especially on the 15-min single-bottle test. Thus, to better assess the specific areas of damage associated with CTA deficits, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated to compare intake and preference scores with the extent of lesion (lesion score) on the whole as well as within several subregions of interest in and around posterior insular cortex (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between extent of lesion in designated insular cortex zones and CS Intake and Preference Score.

| 0.1 M NaCl POSTSURGICAL TESTS |

0.1 M SUCROSE POSTSURGICAL TESTS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-min | 96-h | Trial 2 | 15-min | 96-h | |

| Total Lesion Size | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| IC2+IC3 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| IC2 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.56 |

|

IC2 (AI+DI only) |

0.46 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.54 |

| IC3 | 0.19 | −0.16 | 0.06 | −0.10 | −0.33 |

| Anterior IC2 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| Posterior IC2 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.49 |

| Anterior IC3 | 0.23 | −0.20 | 0.07 | −0.10 | −0.28 |

| Posterior IC3 | 0.06 | −0.24 | 0.003 | −0.08 | −0.41 |

| Posterior IC2+ Anterior IC3 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Posterior IC1 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| IC2+ Posterior IC1 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.52 |

Values are Spearman’s r. Significant correlations, determined with B-H FDR q-value, appear in bolded and italicized font. Insular cortex zones are outlined in Figure 1.

Abbreviations: IC, Insular Cortex; AI, agranular insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex.

Additionally, to reveal areas of damage associated with deficits, we categorized Li-injected rats with bilateral lesions as IMPAIRED (≥97.5 percentile of SHAM-Li or UNI-Li group) or UNIMPAIRED (< 97.5 percentile of SHAM-Li or UNI-Li group) separately for each CTA test. Then, the lesion symmetry maps of each individual rat belonging to the IMPAIRED behavioral subgroup were compiled to generate an average lesion score map for each CTA trial/test. The same was done for the UNIMPAIRED subgroup for comparison.

From this analysis, it is clear that overall lesion size or extent of damage in the IC3 zone of insular cortex were not related to the degree of deficit on any of the CTA trials/tests. On the other hand, the extent of damage in the IC2 zone was significantly correlated with CTA deficits, particularly on the postsurgical 96-h two-bottle preference tests for both the NaCl CS and the sucrose CS. Within this zone, the anterior half of IC2 (approx. coordinates) was more correlated with impaired CTA expression, than was the posterior half of IC2 on these tests. The area just rostral to IC2 (i.e., the posterior half of IC1) was also significantly correlated with deficient performance on the 96-h two-bottle tests. Notably, the very posterior portion of IC1 contains the most anterior strip of VC in the granular subregion just dorsal to GC (see Figure 1). Even so, the correlations between the damage to these two subregions (anterior IC2 and posterior IC1) and the 96-h two-bottle preference deficits did not appear to account for much more of the variance relative to the correlation between the damage in the IC2 zone on the whole and the 96-h two-bottle preference deficits (see Table 4). Thus, the reason that lesion damage to these more anterior areas appears to be strongly correlated with CS preference is likely because these cases also had a good portion of posterior IC2 damaged as well. In fact, there was a significant positive correlation between lesion damage in IC2 and the lesion damage in the posterior portion of IC1 (Spearman r=0.84, p<0.0001), further suggesting these lesions generally extended across this entire area.

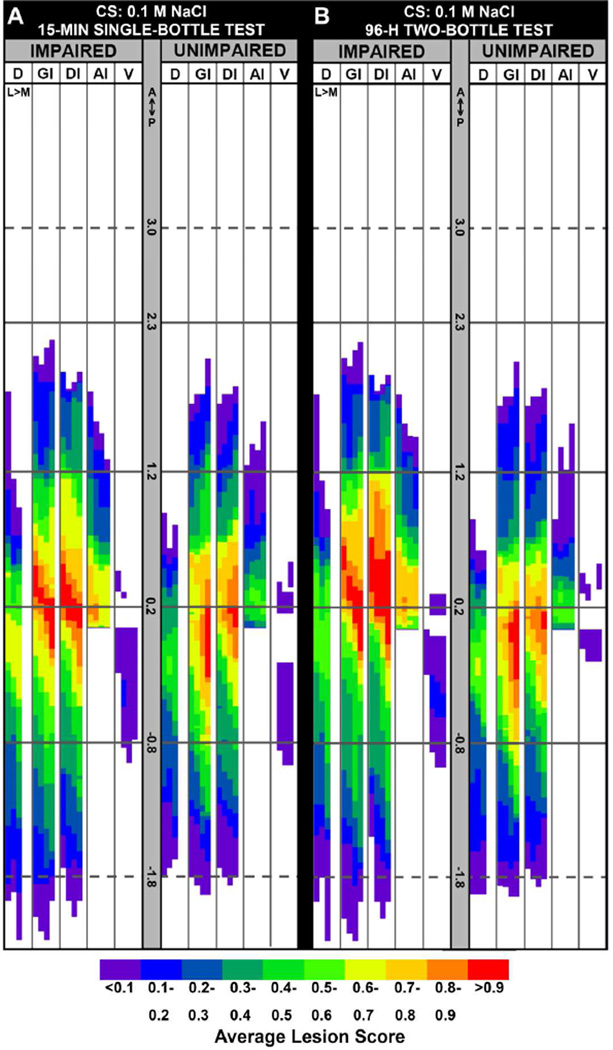

The corresponding lesion overlap maps from the IMPAIRED group for these tests corroborate this (see Figures 7 and 8). Nearly all the IMPAIRED rats exhibited complete or near complete lesions in IC2, spanning from its posterior border to just over its anterior border. Direct comparison of the proportion of IC2 damaged for the groups of rats considered IMPAIRED versus those considered UNIMPAIRED confirmed that the IMPAIRED rats had significantly more damage to IC2 than did the UNIMPAIRED rats on the 96-h two-bottle tests (see Figure 9, corresponding statistics and p-values appear in the figure caption). There were no differences among these subsets with respect to the extent of damage in IC3.

Figure 7.

A: Group-wise lesion maps showing the average insular cortex lesion profiles in color scale for a group of rats (n=13) that were significantly IMPAIRED on the postsurgical 15-min single-bottle retention test of a presurgically acquired CTA to 0.1 M NaCl and for the group of rats that were UNIMPAIRED (n=14) on that same test. B: Group-wise lesion maps showing the average insular cortex lesion profiles in color scale for a group of rats (n=10) that were significantly IMPAIRED on the postsurgical 96-h two-bottle preference test with the 0.1 M NaCl CS versus dH2O and for the group of rats that were UNIMPAIRED (n=16) on that same test. Impairment was determined as intake or preference scores ≥97.5 percentile of the Li-injected control group scores on the same test. The solid black horizontal lines demarcate the anterior border of GC (+2.3 mm), the approximate center of GC (+1.2 mm), the posterior border of GC (+0.2 mm), and the posterior border of VC (−0.8 mm), AP relative to bregma. The dashed gray horizontal lines at +3.0 and −1.8 mm provide additional AP reference points. Compare with Figures 2 and 8. Abbreviations: A, Anterior; P, Posterior; AI, agranular insular cortex (dorsal to the rhinal fissure); D, dorsal to insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; GI, granular insular cortex; L, lateral; M, medial; V, ventral to rhinal fissure.

Figure 8.

A: Group-wise lesion maps showing the average insular cortex lesion profiles in color scale for a group of rats (n=9) that were significantly IMPAIRED on the second trial of postsurgical acquisition of a CTA to 0.1 M sucrose and for the group of rats that were UNIMPAIRED (n=12) on that same session. B: Group-wise lesion maps showing the average insular cortex lesion profiles in color scale for a group of rats (n=7) that were significantly IMPAIRED on the postsurgical 96-h two-bottle preference test with the 0.1 M sucrose CS versus dH2O and for the group of rats that were UNIMPAIRED (n=15) on that same test. Impairment was determined as intake of preference scores ≥97.5 percentile of the Li-injected control group scores on the same test. The solid black horizontal lines demarcate the anterior border of GC (+2.3 mm), the approximate center of GC (+1.2 mm), the posterior border of GC (+0.2 mm), and the posterior border of VC (−0.8 mm), AP relative to bregma. The dashed gray horizontal lines at +3.0 and −1.8 mm provide additional AP reference points. Compare with Figures 2 and 7. Abbreviations: A, Anterior; P, Posterior; AI, agranular insular cortex (dorsal to the rhinal fissure); D, dorsal to insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; GI, granular insular cortex; L, lateral; M, medial; V, ventral to rhinal fissure.

Figure 9.

Median + SIQR proportions damaged of IC2 and IC3 zones plotted as a function of impairment group for each CTA test. Top left panel (A): Postsurgical 15-min single-bottle test with the 0.1 M NaCl CS [proportion of damage to IC2 for IMPAIRED rats versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=52.0, nIMPAIRED = 13; nUNIMPAIRED = 14, p=0.06; proportion of damage to IC3 for the IMPAIRED rats versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=84.0, nIMPAIRED = 13; nUNIMPAIRED = 14, p=0.75]. Top right panel (B): Postsurgical 96-h two-bottle test with the 0.1 M NaCl CS versus dH2O [proportion of damage to IC2 for IMPAIRED rats versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=28.0, nIMPAIRED = 12; nUNIMPAIRED = 15, p=0.003; proportion of damage to IC3 for the IMPAIRED rats versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=80, nIMPAIRED = 12; nUNIMPAIRED = 15, p=0.64]. Bottom left panel (C): Postsurgical CTA acquisition Trial 2 with the 0.1 M sucrose CS: [proportion of damage to IC2 for the IMPAIRED rats versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=46.0, nIMPAIRED = 11; nUNIMPAIRED = 15, p=0.06; proportion of damage to IC3 for the IMPAIRED versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=81.0, nIMPAIRED = 11; nUNIMPAIRED = 15, p=0.96]. Bottom right panel (D): Postsurgical 96-h two-bottle test with the 0.1 M sucrose CS versus dH2O: [proportion of damage to IC2 for IMPAIRED versus UNIMPAIRED rats: U=20.0, nIMPAIRED = 8; nUNIMPAIRED = 18, p=0.004; proportion of damage to IC3 for the IMPAIRED versus the UNIMPAIRED rats: U=58.0, nIMPAIRED = 8; nUNIMPAIRED = 18, p=0.45]. Asterisks indicate significant differences.

The relationships between particular lesion topographies and impairments on the postsurgical 15-min single-bottle test of the presurgically trained NaCl CS were less clear. As mentioned above, the greatest number of rats was impaired on this test, including individual rats from each of the three Li-injected lesion groups. Our correlational approach did not reveal any particular commonalities in the lesion profiles associated with the deficit. The strongest, albeit non-significant, correlation was with the posterior half of the IC2. Despite this, the overlap lesion map of the rats IMPAIRED on this test clearly shows that all or nearly all these rats also had complete or near complete damage to this particular subregion (see Figure 7). As such, this map further highlights that even those rats from the IC3 group that were impaired had some damage in that posterior part of IC2. Similarly, CTA deficits on Trial 2 of the postsurgical acquisition phase with sucrose were not significantly correlated with the extent of lesion in any particular zone. As shown in the overlap maps of Figure 8, if anything, the IMPAIRED rats tended to show more damage centered in the posterior part of IC2, while the UNIMPAIRED rats tended to have damage centered more posterior to that. Most of the Li-injected rats with lesions completely avoided the sucrose CS in the 15-min single-bottle test; thus, as expected, no significant correlations or critical damage zones were revealed. In general, all rats that were impaired on the 96-h tests were impaired on the 15-min tests (including the postsurgical test with the NaCl CS and Trial 2 with the sucrose CS) as well, but some rats that were impaired on these 15-min tests were not subsequently impaired on the 96-h tests. A discussion of some factors that may contribute to the differential behavioral profiles follows.

DISCUSSION

Although lesion studies have traditionally revealed a critical role for GC in CTA (e.g., Braun et al, 1982; Lasiter and Glanzman, 1982; Dunn and Everitt, 1988; Bermudez-Rattoni and McGaugh, 1991; Nerad et al, 1996; Cubero et al, 1999; Fresquet et al, 2004; Roman and Reilly, 2007), several recent reports have questioned this attribution (Geddes et al, 2008; Hashimoto and Spector, 2014, Schier et al, 2014; Blonde et al, 2015). Indeed, a previous study in rats from our laboratory failed to find evidence of CTA impairment following extensive damage in GC (Schier et al, 2014). However, in that study, rats with specific damage of the posterior GC and overlying granular IC (collectively referred to as IC2 here) as well as a portion of IC posterior to that area (referred to as IC3 here) displayed significant CTA deficits, whereas rats sustaining damage to anterior GC (referred to as IC1 here) did not. The present study has further refined the critical area of IC that must be damaged to disrupt CTA expression. This critical region includes the entire posterior portion of conventionally defined GC coupled with the overlying granular layer of IC, usually considered as the anterior portion of visceral cortex, (i.e., IC2). In contrast, substantial damage to more posterior regions of the visceral cortex (i.e., IC3) leaves rats relatively unimpaired with respect to CTA.

In particular, here, a group of rats that had bilateral lesions in IC2 subsequently failed to display a presurgically acquired CTA to 0.1 M NaCl in the 15-min single-bottle and 96-h two-bottle tests. Although this group successfully acquired a second CTA to 0.1 M sucrose postsurgically, the rate of this acquisition was somewhat slower than Li-injected controls. In other words, whereas Li-injected SHAM and UNI controls avoided the CS on the second trial, IC2-Li rats showed complete avoidance of the CS, only after that second trial in the 15-min single-bottle test. This avoidance, however, was only transitory; later, this group failed to avoid the same CS in the 96-h two-bottle preference test. By comparison, a group that had extensive bilateral lesions in IC2, but also had extensive damage in IC3 (IC2+IC3-Li) tended to show a similar pattern of deficits, though, in many cases, these deficits were not as strong. A third group of rats with histologically confirmed bilateral lesions in IC3 was less encumbered. Although this IC3-Li group had some difficulty avoiding the NaCl CS in the postsurgical 15-min single-bottle test of the presurgically acquired CTA, they were able to avoid the same CS in the 96-h two-bottle preference tests and were able to acquire a second CTA to sucrose after two trials and maintain that avoidance of the CS over a 96-h two-bottle test. Coupled with our prior work showing that lesions of anterior GC (i.e., IC1) did not disrupt CTA expression, the outcomes from the present experiment suggest that the area encompassing the conventionally defined posterior GC and the overlying portion of the anterior VC (i.e., IC2; see Figure 1) is the critical subregion of IC for CTA, while the more posterior portion of VC (i.e., IC3) is not.

IC2

Further bolstering this specific association between IC2 and CTA, lesion size in this area was significantly positively correlated with CS preference on both the postsurgical expression of a presurgically trained CTA (to NaCl) and postsurgically-trained CTA (to sucrose) in 96-h two-bottle tests. In some cases, CTA deficits were best associated with the anterior half of IC2 and the IC just rostral to that, in the posterior half of IC1, but these correlations must be considered in context. First, many of the lesions that were principally positioned in IC3 and were not associated with CTA deficits also extended into the posterior half of IC2, and, thus likely somewhat weakening the relative association between posterior IC2 and CS intake/preference. As discussed before, the fact that (a) the correlations between the damage in the anterior IC2 or posterior IC1 and performance on the 96-h two-bottle preference tests did not account for much more of the variance than did damage in the IC2 zone on the whole, and (b) the proportion of damage in posterior IC1 was significantly correlated with the proportion of damage in IC2, together suggest that the lesion topography best associated with impaired CTAs was one that spanned the entire IC2 zone. Accordingly, prior studies, including our own (Hashimoto and Spector, 2014), which showed that rats with extensive lesions well centered in the GC and with significant damage to the anterior portion of what is considered IC2 here did not display CTA impairments, likely included rats with insufficient damage of the entire IC2, especially in its posterior extreme.

Furthermore, it was somewhat that in the present study the group of rats that were originally categorized as having single IC2 lesions tended to be more impaired than the group of rats that were categorized as having lesion to this same area (IC2) plus lesions to IC3 (IC2+IC3) in the group-wise analyses. Yet, a closer examination of the lesion topographies of the rats categorized into each of these two groups indicated that the IC2-Li group tended to have somewhat more damage to the anterior half of IC2 (median ± SIQR proportion of anterior IC2 with lesion= 0.68±0.07) than did those that were categorized as belonging to the IC2+IC3-Li group (median ±SIQR proportion of anterior IC2 with lesion = 0.58±0.03). Of course, future studies will be needed to continue to systematically parse this CTA zone in IC2 and determine whether it is indeed necessary to destroy the entire span of IC2 or whether the true critical zone of damage leading to CTA deficits is located within yet a smaller subregion in this area of IC2.

IC3

It is quite clear that lesion size in IC3 (or any portion of it) was not correlated with impaired CTA. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically target lesions to the posterior VC (IC3 zone) and examine CTA in the rat. Previous studies have shown that lesions to subrhinal agranular insular cortex just below IC2 and IC3 (Mackey et al, 1986), which by most conventional definitions is outside the VC, and lesions centered even more posterior in IC than would have been included in our IC3 zone, also do not seem to affect CTA retention (Nerad et al, 1996). Although it is generally assumed that this viscerosensory area is important for processing LiCl, the available data are equivocal (Bernstein and Koh, 2007; St. Andres et al, 2007; Contreras et al, 2007). In the present study, the fact that all lesion subgroups eventually acquired a second postsurgical CTA suggests that this subregion is not absolutely essential for LiCl signal processing.

Sources of Behavioral Variability

A close survey of the behaviors of individual rats across the various CTA tests reveals some exceptions to the aforementioned findings. First, impairments on the 15-min single-bottle sessions (postsurgical NaCl retention test, postsurgical sucrose CTA trial 2) were more distributed across the lesion subtypes. Several rats from all three lesion groups initially failed to abstain from consuming the CS in these sessions, but then later exhibited complete CS avoidance when given a choice between the CS and water. Notably, these single-bottle sessions were conducted under a strict water-deprivation schedule, in which the Li-injected rats must weigh the need to obtain fluid over the need to avoid a potentially toxic stimulus. Thus, these particular demands may unveil CTAs that are somewhat weaker than that observed in Li-injected controls, but are not altogether lacking. Alternatively (or perhaps additionally), it could be that some aspect of these “other” lesion topographies interfere with the ability to recall or perceive the specific attributes of the CS (e.g., quality, intensity) and/or contextual cues that were encoded during the acquisition phase at a later single-bottle test. But, when the CS is pitted against a distinct and safe alternative source of hydration (i.e., dH2O) in the two-bottle test, these particular rats have a sufficient amount of sensory information in order to avoid the CS.

Rate of postsurgical CTA acquisition depends on many of the same processes, as well as the perceived intensity of the LiCl-induced signal arising from the viscera (Nowlis, 1974; Nachman and Ashe, 1973). Even partial losses in any of these signals or capacities can weaken CTA, without completely abolishing it. Clearly though, in the present study, neither the IC lesions associated with these sorts of transient or partial CTA deficits, nor those that completely disrupt CTA expression in the 96-h two-bottle tests discussed above, appear to render the animals completely insensitive to any of the stimuli. All rats were able to eventually acquire a postsurgical CTA to sucrose, and were able to discriminate the taste CSs from water, though other non-taste cues may be contributing to these behaviors too. The overlap maps of the IMPAIRED rats for both the postsurgical 15-min single-bottle test of the presurgically acquired CTA to NaCl and the second trial of CTA training with the sucrose CS indicated that all these rats had complete or near complete damage of the posterior half of IC2. Otherwise, there was little else in common among the lesion topographies of these rats. Some of the bimodality within each of the lesion groups may be explained by differences in the type of cues or strategy employed by a given rat in a particular test situation. Further experimental work will be needed to systematically test the hypothesis that these various lesion topographies affect different types of information or processing that ultimately weakens CTA expression, as observed in the 15-min single bottle tests.

Sources of Anatomical and Topographical Variability

Seemingly more difficult to reconcile is the fact that three out of the 15 rats categorized as having extensive bilateral damage to the IC2 zone showed absolutely no signs of impairment on any of the CTA tests, despite having lesion topographies that were nearly identical to the rats that showed the most consistent and profound impairments. Similarly, one out of the 9 rats categorized as having primarily extensive IC3 damage, with little IC2 damage, was relatively impaired on all CTA tests. While the general picture that is emerging from our recently published work (Hashimoto and Spector, 2014; Schier et al., 2014; Blonde et al, 2015) points to a more complex functional topography of GC and IC, findings that encourage the use and comprehensive analysis of more targeted lesions, the high resolution lesion mapping approach employed here has also begun to underscore the possible incidence of anatomical variation between individual rat brains. In fact, Hashimoto and Spector (2014) first reported the relatively considerable inter-subject and inter-hemispheric variability in the relative position of the intersection of the middle cerebral artery and the rhinal fissure (see also, Kida et al, 2015). This is of particular importance in terms of understanding the organization of GC, given that this landmark is commonly used to describe the relative position of taste-responsive neurons in IC and has accordingly been used to guide lesion placement and/or drug infusions in GC. Similarly, through the use of our high resolution lesion mapping system, we found that the AP distances between several forebrain anatomical landmarks, and hence the relative positions of brain areas, varied among the adult male outbred Sprague-Dawley rats in analyzed here. Variability in these landmarks across brains and hemispheres can make it difficult to compare the effects of particular lesion locations on taste-guided behaviors or the topographical organization of taste-related cortical activity across rats. While some of this variability may be due to differential deformation and shrinkage dynamics inherent in histological processing of the tissue, in vivo mapping of rodent brains also shows some degree of inter-subject anatomical variability (e.g. Figini et al, 2014). To help mitigate some of these sources of variability, our lesion mapping system was modified slightly from our previous iteration (as described in Schier et al, 2014). In the present application, lesion and tissue sizes were adjusted according to the relative distances between several anatomical landmarks along the AP extent of the tissue collected for each individual brain (see Materials and Methods). In effect, this permitted the alignment of each brain against a set of common landmarks to compare lesion placement and size. Admittedly, this area and these landmarks can be somewhat difficult to parse, especially in brains with lesion damage, but the high level of correspondence among the lesion scores and maps generated by two separate experimenters from the same brain/lesions provides some assurance that the lesions were mapped in as consistent a manner as possible. Whatever the basis for these anatomical differences, these correction procedures help to ensure that all brains and lesions are compared in similar registration. For these reasons, although we cannot entirely dismiss the possibility, it is not likely that the lesions of these anomalous rats (3 with IC2 lesions, 1 with IC3 lesions) were simply in a different registration, so to speak.

However, in addition to these morphological idiosyncrasies across brains and hemispheres, the neural representation of information may differ between brains and between hemispheres. Indeed, others have noted some topographical variability in the relative location of clusters of quality-specific taste-responsive neurons in insular cortex among individual subjects (Accolla et al, 2007; 2008; Chen et al, 2011; Kida et al, 2011), though this may be due to some extent in the variation of the location of the middle cerebral artery. In other rodent cortical areas, this sort of variation has been more systematically examined (e.g., Riddle and Purves, 1995; Frost et al, 2013). For instance, one study found that the cluster of neurons that elicits a specific motor response (e.g., paw extension), varies not only in size (i.e., number of neurons), but also in location relative to bregma across a cohort of an inbred strain of rats (Frost et al, 2013). Thus, it is possible that for the three rats with confirmed extensive IC2 lesions, the critical CTA zone was either larger than the group average or located in a different area of IC. In other words, in these rats, it is possible that relevant information was stored or otherwise processed in an area outside the lesion in at least one hemisphere, and thus sufficient functionality was spared. Likewise, the critical CTA zone may be shifted slightly more posterior in one or both of the hemispheres of the one impaired rat with extensive IC3 damage, but minimal IC2 damage. It is important to note that unilateral lesions to posterior insular cortex did not impede CTAs. While this suggests then that CTA-related information processing must be distributed bilaterally in posterior insular cortex, it could very well be that the relative positions of the critical CTA zone is somewhat bilaterally asymmetrical in a given rat. It is impossible to confirm whether such idiosyncrasies in cortical topographies underlie the differences observed in the present study, but this technical caveat also serves to highlight the increasing need to consider these issues in order to advance an understanding of the functional organization of the IC.

Combining the strategies used in the present study with others, such as optogenetics, will permit manipulations of insular cortical activity with more favorable spatial and temporal resolution and, in doing so, will help to track these sorts of individual differences in topographic representations of processes associated with taste and visceral signals as well as their integration in behaving subjects. Nevertheless, the fact that there were overall group-wise differences in average CS intakes/preferences of between rats that had significant lesion damage in IC2 versus those that had significant damage in IC3, coupled with the fact that lesion size in IC2, but not IC3, was correlated with deficits in the two-bottle preferences tests, suggest that the association between lesions in IC2 and impaired CTA expression is sufficiently stereotyped, making it the best IC target for damage-induced impairments in CTA expression. The individual deviations from this only underscore that such critical brain sites are average constructs.

Conclusions and Future Directions

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine the function of this specific region of posterior insular cortex that includes IC2 and IC3 with neurotoxic lesions that do not also conjointly damage anterior and/or posterior areas of IC. Whether the CTA deficits produced by lesions to this area were related to disruptions in stimulus detection, hedonic processing, memory, or some other mechanism is unclear. But with this critical brain site in IC where damage results in disruption of CTA more delimited, it can now be more selectively manipulated and other taste-guided behavioral tasks can be applied in order to further determine whether its role is specific to this particular taste-visceral process or whether it contributes to other functions as well. Moreover, because the hedonic valences of tastes are somewhat plastic, changing with the internal milieu and by association with particular visceral consequences (e.g., Spector et al, 1988; Berridge, 1991), and because linking the specific attributes of a particular taste (calling upon detection and discriminative function) to its physiological consequences is critical in an animal’s selection of nutrients and avoidance of toxins in the environment (see Domjan, 1975), this area and other surrounding areas may very well contribute to other behaviors that depend on taste-visceral integration. Combining various sorts of targeted manipulations of neural structures with comprehensive behavioral and anatomical analyses will be arguably indispensable to ultimately unveiling the functional organization of taste and visceral signals in insular cortex, and throughout the CNS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders grants R01 DC009821 (ACS) and F32 DC013494 (LAS).

We would like to thank Kelly Palmer for her assistance collecting data and Charles Badland for his help with figure production.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: All authors had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: LAS and ACS. Acquisition of data: LAS and GDB. Analysis and interpretation of data: LAS and ACS. Drafting of the manuscript: LAS and ACS. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: LAS, GDB, and ACS. Statistical analysis: LAS. Obtained funding: ACS and LAS. Administrative, technical, and material support: GDB. Study supervision: LAS and ACS.

LITERATURE CITED

- Accolla R, Bathellier B, Petersen CC, Carleton A. Differential spatial representation of taste modalities in the rat gustatory cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1396–1404. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5188-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accolla R, Carleton A. Internal body state influences plasticity of sensory representations of gustatory cortex. PNAS. 2008;105(10):4010–4015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708927105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GV, Saper CB, Hurley KM, Cechetto DF. Organization of visceral and limbic connections in the insular cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;311(1):1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.903110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker L, Best MR, Domjan M, editors. Learning mechanisms in food selection. Waco: Baylor University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berman DE, Dudai Y. Memory extinction, learning anew, and learning the new: Dissociations in the molecular machinery of learning in cortex. Science. 2001;91(5512):2417–2419. doi: 10.1126/science.1058165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Rattoni F, McGaugh JL. Insular cortex and amygdala lesions differentially affect acquisition on inhibitory avoidance and conditioned taste aversion. Brain Res. 1991;549(1):165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90616-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IL, Koh MT. Molecular signaling during taste aversion learning. Chem Senses. 2007;32:99–103. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjj032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]