Abstract

The parvicellular portion of the ventroposteromedial nucleus (VPMpc) is the part of the thalamus that processes gustatory information. Anatomical evidence shows that the VPMpc receives ascending gustatory inputs from the parabrachial nucleus (PbN) in the brainstem and sends projections to the gustatory cortex (GC). Although taste processing in PbN and GC has been the subject of intense investigation in behaving rodents, much less is known on how VPMpc neurons encode gustatory information. Here we present results from single-unit recordings in the VPMpc of alert rats receiving multiple tastants. Thalamic neurons respond to taste with time-varying modulations of firing rates, consistent with those observed in GC and PbN. These responses encode taste quality as well as palatability. Comparing responses to tastants either passively delivered, or self-administered after a cue, unveiled the effects of general expectation on taste processing in VPMpc. General expectation led to an improvement of taste coding by modulating response dynamics, and single neuron ability to encode multiple tastants. Our results demonstrate that the time course of taste coding as well as single neurons' ability to encode for multiple qualities are not fixed but rather can be altered by the state of the animal. Together, the data presented here provide the first description that taste coding in VPMpc is dynamic and state-dependent.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Over the past years, a great deal of attention has been devoted to understanding taste coding in the brainstem and cortex of alert rodents. Thanks to this research, we now know that taste coding is dynamic, distributed, and context-dependent. Alas, virtually nothing is known on how the gustatory thalamus (VPMpc) processes gustatory information in behaving rats. This manuscript investigates taste processing in the VPMpc of behaving rats. Our results show that thalamic neurons encode taste and palatability with time-varying patterns of activity and that thalamic coding of taste is modulated by general expectation. Our data will appeal not only to researchers interested in taste, but also to a broader audience of sensory and systems neuroscientists interested in the thalamocortical system.

Keywords: coding, expectation, palatability, state-dependent, taste, thalamus

Introduction

Neurons in the parvicellular portion of the ventroposteromedial nucleus of the thalamus (VPMpc) receive inputs conveying gustatory information from the parabrachial nucleus (PbN) (Karimnamazi and Travers, 1998; Bester et al., 1999; Holtz et al., 2015). VPMpc neurons process ascending gustatory signals and send their output to the gustatory cortex (GC) (Pritchard et al., 1989; Allen et al., 1991; Shi and Cassell, 1998; Verhagen et al., 2003; Samuelsen et al., 2013). The VPMpc exerts a strong influence on GC activity (Samuelsen et al., 2013). Silencing of VPMpc changes the background state of gustatory cortical networks. In addition, inactivation of VPMpc alters taste-evoked dynamics and reduces neurons' ability to encode taste in GC. The function of VPMpc is not limited to processing physiochemical signals. Lesions of VPMpc impair anticipatory contrast and autoshaping (Reilly and Pritchard, 1996, 1997), suggesting an involvement of the thalamus in the anticipation of taste.

Despite the key role of VPMpc, little is known about how thalamic neurons encode taste. Most of what is known about VPMpc in rodents comes from experiments in anesthetized or paralyzed animals (Scott and Erickson, 1971; Scott and Yalowitz, 1978; Nomura and Ogawa, 1985; Ogawa and Nomura, 1988; Verhagen et al., 2003). Recordings in urethane-anesthetized rats revealed that almost half of VPMpc neurons respond to taste and that taste responses are multimodal and broadly tuned. In addition, these experiments suggested that VPMpc can encode the hedonic value of taste (Verhagen et al., 2003). Although these studies have shaped our understanding of thalamic processing, it is not clear how the patterns of activity observed in anesthetized rats relate to those recently described in other gustatory regions in alert animals. Recordings in the PbN (Di Lorenzo et al., 2009; Rosen et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2014) and in GC (Fontanini and Katz, 2006; Jones et al., 2007; Samuelsen et al., 2013) show that, in behaving rodents, neurons respond to taste with time-varying modulations of firing rates. Given the interconnectivity of VPMpc with these two areas, it is likely that in alert animals thalamic neurons may display heterogeneous temporal dynamics and multiplex gustatory information via time-varying modulations of firing rates. In addition, recent analyses of taste coding in GC show that temporal coding of gustatory information is shaped by the state of the animal. Specifically, expectation enhances taste coding by shortening the latency at which gustatory information is encoded by GC spiking activity (Samuelsen et al., 2012). These results, together with data from other sensory systems (Krupa et al., 1999; Cano et al., 2006; McAlonan et al., 2008; Saalmann and Kastner, 2011), suggest that also VPMpc might modify its temporal coding scheme according to the anticipatory state of the animal.

Here we present results from single-unit recordings in alert rats unveiling how VPMpc processes chemosensory information. First, we analyzed taste coding for passively delivered tastants, focusing on the temporal dynamics of chemosensory and palatability coding. We then compared, for each neuron, responses to passively delivered tastants with responses to cued and self-delivered stimuli. This approach was used to probe the effects of general expectation on taste processing.

To our knowledge, our results provide the first description that taste coding in VPMpc is dynamic and state-dependent and that expectation modulates the thalamic coding of taste.

Materials and Methods

Experimental subjects.

All the experimental procedures were performed according to federal, state, and university regulations regarding the use of animals in research and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stony Brook University. Eleven adult female Long–Evans rats (280–350 g) served as the subjects in this study. Animals were maintained on a 12 h light/12 h dark schedule and were given ad libitum access to chow and water, unless otherwise specified.

Surgical procedures.

Rats were anesthetized using an intraperitoneally injected ketamine/xylazine/acepromazine mixture (100, 5.2, and 1 mg/kg, respectively) with supplemental doses (30% of induction dose) to maintain surgical levels of anesthesia. After placing rats in a stereotaxic device, the scalp was sterilized with 0.1% iodine and excised to reveal the skull. Holes were drilled for the placement of anchoring screws and electrode bundles. Micro-drivable electrode bundles, consisting of 16 25-μm formvar-coated nichrome microwires (Katz et al., 2001) or 4 tetrodes (Jaramillo and Zador, 2011), were inserted dorsal to VPMpc (anteroposterior, −3.6 mm from bregma; mediolateral, 1.1 mm from bregma; dorsoventral, 5.9 mm from dura) (Verhagen et al., 2003; Samuelsen et al., 2013) in one or both hemispheres. All implants were cemented to the skull with dental acrylic. Intraoral cannulae (IOC) (Phillips and Norgren, 1970) were implanted bilaterally and cemented onto the head cap with dental acrylic (Katz et al., 2001; Fontanini and Katz, 2005). Rats received antibiotic treatment (topical: Neosporin ointment, Pfizer; systemic: penicillin benzathine) and analgesics (procaine and ketorolac) immediately after the surgery and for up to 4 d following the surgery. Rats were allowed to recover from the surgery for at least a week.

Behavioral training and general expectation behavioral paradigm.

After recovery from surgery, rats were water restricted (45 min of water/d) for ∼5 d and habituated to the behavioral/recording chamber (MED Associates) as well as to receiving fluids through IOC (Phillips and Norgren, 1970; Katz et al., 2001; Fontanini and Katz, 2005) for 2–3 d. Once habituated, rats were trained to self-administer and passively receive tastants. In our experiments, training lasted ∼2 weeks (i.e., until rats showed stable behavior and self-delivered >6 trials for each taste). Every trial began with an auditory cue. The cue was a sine wave at one of the following frequencies: 3000, 6000, or 9000 Hz; it had an intensity of 80 dB and a duration of 500 ms. Rats learned to respond by poking the nose into a port in the chamber after the offset of the cue and within a response window (3 s). Successful responses led to the delivery of a gustatory stimulus (∼40 μl delivered by a pressurized, computer-controlled system) into the rat's mouth via a manifold of four polyimide tubes slid into one of the IOC. The following tastants were used: 100 mm NaCl (N), 100 mm sucrose (S), 200 or 100 mm citric acid (C), and 1 mm quinine HCl (Q). Water was not delivered as a stimulus for technical reasons (because of diameter limitation, we could use only 4 polyimide tubing for the manifold) and for consistency with previous work from our and other laboratories in alert rats (Katz et al., 2001; Fontanini and Katz, 2006; Piette et al., 2012; Sadacca et al., 2012; Samuelsen et al., 2012; Gardner and Fontanini, 2014). Tastants were delivered in pseudorandom order following each cued, head entry. We defined this type of trial as self-administration (Self). Each taste delivery was followed, 5 s later, by a water rinse (∼45 μl) delivered into the contralateral IOC. The volume of water delivered as a rinse is consistent with previous studies using similar methods (Fontanini and Katz, 2006; Grossman et al., 2008; Samuelsen et al., 2012). Analysis of firing rates in VPMpc 5–6 s after the rinse reveals a complete return to baseline firing (baseline, 1 s before passive taste delivery: 16.0 ± 1.64 Hz; 5–6 s after water rinse: 15.96 ± 1.62 Hz, paired-samples t test, n = 128, p = 0.67). This suggests that the rinse, together with the awake rat's tendency to wash its own tongue with saliva, is enough to clear the tongue from the previously presented tastant. After self-administering the taste, rats were required to wait a variable intertrial interval of 30–50 s until the next trial started. At random times during the intertrial interval, taste solutions (followed by a rinse, 5 s later) were delivered by the computer-controlled system in the absence of any cue. These trials were defined as Passive deliveries. Recordings were performed exclusively upon completion of training and once learning had occurred, such that the effects of expectation could be studied at steady state. Recording sessions normally lasted 45 min, wherein each taste solution for each condition was delivered in at least 6 trials.

Electrophysiological recordings.

A Plexon Multichannel Acquisition Processor (Plexon) was used for electrophysiological recordings. Single-unit waveforms were amplified (gain from 4000 to 16,000), bandpass filtered (from 300 to 8000 Hz), and digitized (sampling rate: 40 kHz). Single units were recorded with either wires or tetrodes. Unique single-unit waveforms of at least 3:1 signal-to-noise ratio were recorded and isolated relying on voltage threshold detection and a template matching algorithm. Units were further sorted off-line using cluster cutting techniques and examination of interspike interval plots (Offline Sorter, Plexon).

Data analysis.

All data analyses were performed using customized MATLAB scripts (The MathWorks). Data are presented as mean ± SEM in the main text, unless otherwise indicated. A bootstrap procedure was used to estimate the mean and 95% CI and to determine significance; 1000 runs were used, unless otherwise indicated.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (auROC) method.

In this study, we used the auROC method for the following: (1) normalization of firing rate according to its baseline; (2) comparison across taste-evoked responses (see palatability index [PI]); and (3) comparison of state-related modulation (see modulation index [MI]). Detailed description of this method can be found in previous publications (Cohen et al., 2012; Jezzini et al., 2013). Briefly, the auROC method compares two distributions of firing rates (or spike counts). It yields a quantity between 0 and 1, which is the auROC value. When comparing taste-evoked activity to its baseline with the auROC method, values >0.5 indicate that the evoked firing rate is above baseline (i.e., excitatory modulation), whereas values <0.5 mean that the evoked activity is below baseline (i.e., inhibitory modulation).

Taste responsiveness.

Taste responsiveness and response latency were assessed using the adaptive change point method (CP) (Gallistel et al., 2004; Jezzini et al., 2013). Briefly, the CP method relies on the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of spike occurrences across all trials for a given taste for each single unit. Spikes were polled across trials within a temporal window going from 1 s baseline (i.e., 1 s before taste deliveries for Passive or 1 s before cue onset for Self) to 2.5 s after taste delivery. Only 2.5 s after taste delivery were analyzed for consistency with previous publications on taste processing in alert rats (Katz et al., 2001; Fontanini and Katz, 2006, 2009; Grossman et al., 2008; Yoshida and Katz, 2011; Piette et al., 2012; Sadacca et al., 2012; Samuelsen et al., 2012, 2013; Li et al., 2013). The timing of each spike was adjusted relative to the timing of stimulus delivery. The cumulative sum of spike counts was computed at the time of each spike occurrence. Putative variations of spike counts were identified as the points where the cumulative sum of the spike count produced local maximal changes in slope (putative CP). The significance of changes in the slope of the CDF were determined by comparing spike counts before and after each putative CP using a binomial test (p < 0.05) (Gallistel et al., 2004). A significant change in the slope of the CDF was defined as a CP and indicated the onset of a firing rate modulation. To avoid artifactual detection of CPs in the baseline period, which would have inflated the number of modulations, we used an adaptive procedure. Briefly, we ran the first CP sweep of the CDF at a fixed tolerance level (using the algorithm in Gallistel et al., 2004; p = 0.05). If a CP was detected before taste delivery, the CP analysis was repeated by decreasing the tolerance level, to make the CP detection more conservative. Adjacent modulation periods were compared with t test (based on firing rate during modulated periods), and modulation periods that were not significantly different were merged. Modulation periods were required to last >10 ms. Post hoc test (t test p < 0.01, one-side) between firing rates in modulated periods and baseline activity was used to determine significant response periods. A neuron was defined as taste-responsive if it had a significant modulation period for at least 1 of 4 taste stimuli. The response latency was determined by the onset of the first response period. The CP analysis was also used to establish the average number of modulation periods per neuron and its time course. The average number of modulations per neuron was assessed by averaging across neurons the sum of the number of modulation periods computed for each taste response over 2.5 s. The time course of modulations was established by averaging across neurons the number of modulations for each 1-ms-long bin. Because each neuron contributed with responses to 4 tastants, the maximum theoretical number of modulations for each 1 ms bin was 4. Minimal numbers of modulations were observed at time 0 and 2.5 s due to the method used to compute the CP.

Taste specificity.

A taste-responsive neuron was considered taste-specific (TasteS) when it featured different responses to different taste stimuli (Jezzini et al., 2013; Samuelsen et al., 2013). This method differs from a comparison between taste responses and water response, but it tests a reasonable definition of taste specificity and is consistent with previous work. Taste-evoked activity (from 0 to 2.5 s after taste delivery) was computed for 250-ms-wide bins. A two-way ANOVA (taste identity × time course) was used to determined taste specificity. If the taste main effect or the interaction term was significant (p < 0.01), a neuron was defined as taste-specific.

Taste classification.

To assess how well each taste is encoded by a single unit or an ensemble of neurons, we used a previously described decoding procedure (Jezzini et al., 2013). This analysis is based on a cross-validation procedure and a Euclidean distance-based classifier (for details, see Jezzini et al., 2013). In this study, a 250 ms bin size was used. Decoding performance was defined as the ratio of test trials that were classified correctly over all trials. When the decoding performance for a certain taste was larger than chance level (significance was based on a binomial distribution), the unit was deemed as taste coding. For the ensemble-based classification, significant decoding was defined by the lower bound of 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI) larger than chance level (0.25). The difference between two populations was considered significant, when it fell outside of the bootstrapped CI. To estimate the minimal number of neurons needed to reach a decoding accuracy of 95%, we created a large surrogate neuronal population from the available data by randomly reassigning the labels of the responses to different tastes (Jezzini et al., 2013; Rigotti et al., 2013). This classification method was also used with a moving window (250 ms bin size, 50 ms step) to assess decoding performance over time.

Taste palatability.

A neuron was defined as palatability coding when: (1) it was taste-specific and (2) its responses followed the intrinsic hedonic value of taste. The choice of limiting the study of palatability to the group of taste-specific neurons was motivated by the consideration that neurons that were not taste-specific could not convey information pertaining to taste (hence, they could not convey palatability information). This conservative criterion led us to exclude 6 taste-responsive neurons whose responses contained some palatability information but were not taste-specific. We used two methods to assess palatability coding. Both methods analyzed the entire time course of responses using a sliding window (250 ms bin size, 50 ms step). The first method is based on PI (see Palatability index, below). A taste-specific neuron was defined to be palatability coding, when its PI was significantly larger than the 97.5 percentile of baseline PI distribution for a continuous period of 200 ms (80% of 250 ms window). The second method was based on Spearman's rank correlation between firing rates and hedonic rank of taste (Sadacca et al., 2012). Because the 4 taste stimuli used in the current study have been widely studied, their preference relationship (i.e., hedonic rank: S > N ≫ C > Q) has been well established (Grill and Norgren, 1978; Breslin et al., 1992; Berridge, 2000; Sadacca et al., 2012). We calculated the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) between firing rates and the taste hedonic rank. When a period longer than 200 ms was significant (p < 0.05), the neuron was defined as palatability coding (this criteria was based on previous studies; Sadacca et al., 2012).

Palatability index.

As measure of palatability-related information, we used a PI, as shown in previous work (Grossman et al., 2008; Fontanini et al., 2009; Jezzini et al., 2013). This method considers the difference in evoked activity between taste stimuli with similar and opposite palatability. To avoid biases introduced by differences in firing rates across neurons, we used the auROC method (see above) to estimate the difference between taste pairs. Briefly, the auROC method yielded a normalized difference between two firing rate distributions (e.g., between S and N). According to this method, a value of auROC of 0.5 means that two distributions are the same. The absolute deviation from 0.5 is the measure of the difference between a taste pair, which we call auROC_D. A 250 ms sliding window with 50 ms steps was applied to taste-evoked activity, and the auROC_D was calculated for every pair. The PI was defined as follows: PI = <d>opposite − <d>same; where <d>opposite = ¼ (auROC_DSQ + auROC_DSC + auROC_DNQ + auROC_DNC), and <d>same = ½ (auROC_DSN + auROC_DCQ), subscripts mean taste pairs (e.g., SN means the taste pair of S and N). The PI ranges from −0.5 to 0.5, with positive values indicating palatability coding and negative values indicating inverse palatability coding (i.e., different neural activity for tastants with similar hedonic value, and similar activity for tastants with opposite hedonic value). Significance was based on a 95% CI of baseline PI distribution, which was assessed by pooling PIs of all units before passive taste deliveries (from −1 to 0 s according to taste delivery).

Time course of taste identity coding.

To quantify the time course of taste coding, we analyzed data relying on a sliding window procedure. A 250 ms window and 50 ms steps were used. Two distinct but convergent analyses were used. First, a one-way ANOVA test was used to compare activity across tastants to determine whether a neuron was taste-specific in a specific bin (p < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction). The first significant bin after taste delivery was defined as the onset of taste coding. The percentage of units that showed significant modulations within each bin were computed. Differences between groups were assessed on the basis of a two-proportion test (p < 0.05; for bins with number <5, Fisher exact test is used, p < 0.05). The second method used to analyze the time course of taste coding relied on the taste classification procedure (see above) applied to each time bin. The decoding performance described how well a given taste was encoded by a neuron within a given time window.

State-dependent modulation of taste responses.

To determine whether a neuron was modulated by the anticipatory state of the animal, we compared taste evoked activity between Self and Passive conditions. To determine the effects of the anticipatory state on general firing activity, we compared firing rates averaged across the entire 2.5 s analysis period. A neuron was defined as significantly modulated, when at least one of the tastants showed a significant difference across conditions (t test, p < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction). To determine whether expectation modulated a neuron's response profile to the 4 tastants, a three-way ANOVA test was used (taste × time × condition, 250 ms bin size was used). A significant response profile modulation was defined by p < 0.01 for at least one of the following terms: time × condition, taste × condition, taste × time × condition. The time course of the modulation was assessed by MI (see Modulation index, below).

Modulation index.

To assess the time course of the difference between responses to Self and Passive, we quantified the MI as follows. First, we calculated the auROC value (see above) between two responses to the same tastants delivered in the two conditions, using a 250 ms moving window (50 ms step). Then, we defined the MI by subtracting 0.5 from the auROC value. As a result, MI ranged from −0.5 to 0.5, with 0 meaning no difference. Positive MI indicated an increase of firing activity of Self versus Passive, whereas negative values indicated a reduction. For each response, significant modulations were determined on the basis of a 95% bootstrapped CI, obtained by shuffling trials between the two conditions. The absolute value of MI was used as a measure of absolute change. In the case of population MI, significance for taste responses over time was determined by comparing the population MIs at a given bin (total of 66 bins) to baseline MIs (t test, p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction). The baseline MIs were calculated by on the basis of spiking activity before passive deliveries and cue onsets.

Principal component analysis (PCA) on taste response pattern.

PCA was used to analyze the pattern of stimulus-evoked response dynamics. The use of PCA is based on Narayanan and Laubach (2009). Temporal patterns were analyzed for all significant taste responses. A response × time (250 ms bin, from −1 to 2.5 s) matrix of auROC normalized responses to all the tastants was compiled. PCA was applied to this matrix. Principal components (PCs) accounting for >5% of the variance were selected. The eigenvectors of selected PCs were used to describe the temporal dynamics of taste responses. In Figure 2D, taste responses were sorted using values of PC1, PC2, and PC3, according to a hierarchical cluster tree based on pairwise Euclidean distance. For each taste response, the dominant PC was determined on the basis of the PC with the largest absolute score. Among 196 significant responses, we identified 127 PC1 dominated, 46 PC2 dominated, and 23 PC3 dominated responses. The percentage of responses with different dominant PCs was computed for taste-responsive units, taste-specific units, palatability-coding units, expectation-modulated units, and non–expectation-modulated units. The χ2 goodness of fit test was used to compare distributions of different PC dominated responses for the various groups of neurons using.

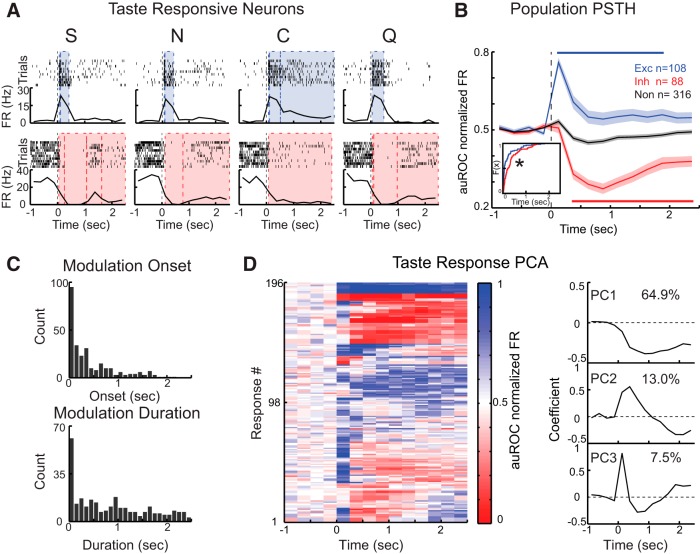

Figure 2.

Responses to taste stimuli are time-varying. A, Representative examples of neurons responding to passive deliveries with increases (top row) or decreases (bottom row) in firing rates. For each neuron, raster plots (top) and PSTHs (bottom) are shown in response to sucrose (S), NaCl (N), citric acid (C), and quinine (Q). Time 0 indicates the onset of taste delivery. Bin size is 250 ms. Shaded areas represent periods in which firing rates are significantly modulated relative to baseline (blue represents excitatory; red represents inhibitory). Dashed lines indicate onsets and offsets of different modulations. B, Population PSTH of excitatory (blue), inhibitory (red), and nonsignificant (black) responses to taste stimuli. Shaded areas represent SEM. Solid lines above and below traces indicate the period in which responses are significantly different from those in unresponsive neurons (independent-samples t test, p < 0.05). Inset, Cumulative density function of response latencies for excitatory (blue) and inhibitory (red) responses. *Significant difference between the two distributions (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p < 0.05). C, Distribution of modulation onsets (top) and modulation durations (bottom). D, Identification of response patterns with PCA. Left, Pseudocolor plot of auROC normalized responses to taste. Time 0 indicates when the stimulus is delivered. Right, Eigenvectors shown for the first three principal components. Top, Monophasic component accounting for 64.9% of variance. Middle, Biphasic component accounting for 13% of variance. Bottom, Triphasic component accounting for 7.5% of variance.

Histological procedures.

At the end of the experiments, rats were deeply anesthetized using the ketamine/xylazine/acepromazine mixture. Electrolytic lesions (10 μA, 10 s) via selected electrode wires were made to mark final positions of the electrodes. Subsequently, rats were perfused intracardially with 0.9% saline followed by 10% formalin. Fixed brains were stored in 10% formalin and cut into 40 or 80 μm coronal sections for standard Nissl staining. Electrode tracks and final positions were verified and reconstructed based on histology, stereotaxic coordinates of the initial positioning, and recording notes.

Results

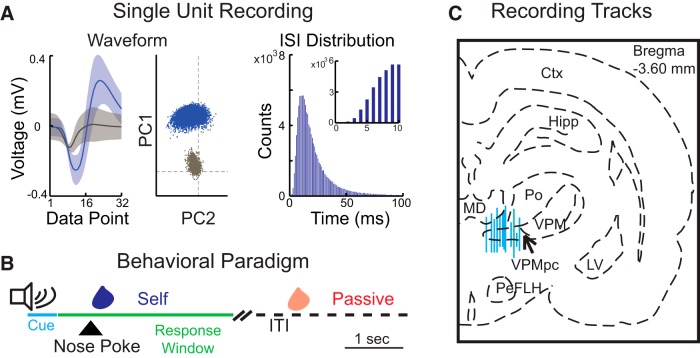

A total of 128 single units (Fig. 1A) were recorded from VPMpc of 11 rats engaged in a behavioral paradigm involving passive deliveries and self-administrations of gustatory solutions (Fig. 1B). Electrode positioning was verified with post hoc histological reconstruction of recording tracts (Fig. 1C). Only recordings from electrodes passing through VPMpc were used for analysis.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedures. A, Representative single-unit recording in VPMpc. Left, Average single-unit spike waveform (blue) and noise (gray). Shadings represent 95% CI. The interval between each data point was 25 μs. Middle, PCA of waveform shape for spikes (blue) and noise (gray). Dashed lines indicate 0. Right, Interspike interval (ISI) distribution of action potentials for the isolated waveform. Inset, Zoom-in from 0 to 10 ms. B, Schematic representation of the behavioral paradigm for passive deliveries and self-deliveries. Each trial begins with a 0.5-s-long auditory cue. Entering a nose port within 3 s from the offset of the cue triggers a self-administration (Self) of a taste solution. Taste solutions can also be delivered passively (Passive) during the intertrial interval (30–50 s). Each taste delivery is followed by a water rinse (not shown). C, Schematic representation of a coronal section of the rat brain (modified from Paxinos and Watson, 2006) showing the dorsoventral range of recordings in gustatory thalamus (VPMpc). Blue lines indicate reconstructed recording tracks from the first to the last recording session. MD, Mediodorsal thalamic nuclei; Po, posterior thalamic nuclear group; VPM, ventroposteromedial thalamic nuclei; Hipp, hippocampus; LV, lateral ventricle; Ctx, cortex; PeFLH, perifornical part of lateral hypothalamus.

VPMpc neurons respond to taste with time-varying modulations in firing rates

To assess how taste affects spiking activity of VPMpc neurons, we analyzed the time course of firing rate modulations in response to gustatory solutions passively delivered into the mouth via an IOC. Figure 2A shows raster plots and PSTHs for two representative neurons: one excited (top) and one suppressed (bottom) by taste delivery. Use of a change point analysis (Jezzini et al., 2013) (see Materials and Methods) revealed that 92 of 128 units (71.9%) showed spiking dynamics that were significantly modulated (either enhanced or depressed) by taste delivery. These neurons were defined as taste-responsive (TasteR). In total, taste delivery suppressed 37 neurons, excited 34 neurons, and had mixed effects on 21 neurons. When individual responses to tastants were analyzed (total response number = 4 × 128), 196 were significantly different from baseline: 108 were excitatory and 88 inhibitory. Figure 2B shows population averages (i.e., PopPSTH) of excitatory and inhibitory responses. On average, excitatory responses showed significantly faster onset compared with inhibitory responses (227 ± 33 ms, n = 108, vs 361 ± 41 ms, n = 88). This was confirmed by comparing response latency distributions of excitatory and inhibitory responses (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p < 0.05; Fig. 2B, inset).

Neurons could show multiple firing rate modulations within the first 2.5 s following taste delivery. Analysis of the onset of these modulations revealed that 69.2% (193 of 279 modulations detected in 196 responses) of modulations started within the first 0.5 s, 16.5% (46 of 279) between 0.5 and 1 s, and 14.3% (40 of 279) after 1 s (Fig. 2C, top panel). The distribution of the duration of significant firing rate modulations was also analyzed (Fig. 2C, bottom panel), revealing that, whereas the median was 701.7 ms, the distribution was rather heterogeneous and spread over the entire 2.5 s (95% CI: 29.4, 2332.2 ms). This result suggests a richness and variety of temporal profiles in VPMpc firing responses. Figure 2D, which shows the entire population of significant taste responses, illustrates the different time courses. To better extract the most frequent trends in the time course of responses, we applied PCA on responses patterns (Narayanan and Laubach, 2009). Activity of significant responses (108 excitatory and 88 inhibitory) from −1 to 2.5 s around taste delivery was normalized using an auROC procedure (see Materials and Methods). The first three principal components (PCs) accounted for 85.3% of total variance (PC1 64.9%, PC2 13%, and PC3 7.5%; Fig. 2D, right). The eigenvector that accounted for the largest variance represented a monotonic component (PC1) that outlasted the 2.5 s period examined. Additional response patterns involved mixed, either biphasic (PC2) or triphasic (PC3), modulations.

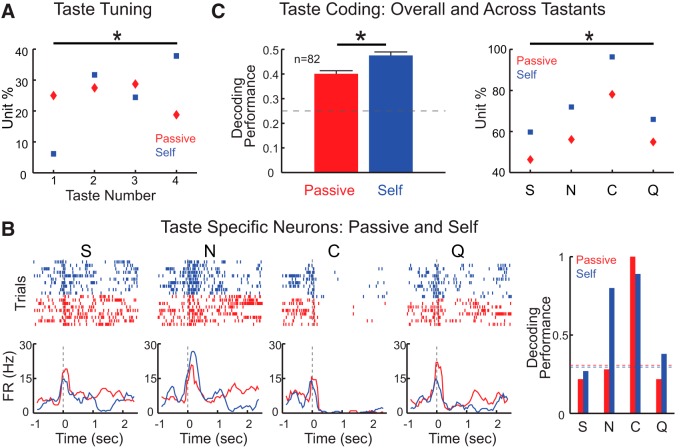

Processing of taste identity in VPMpc

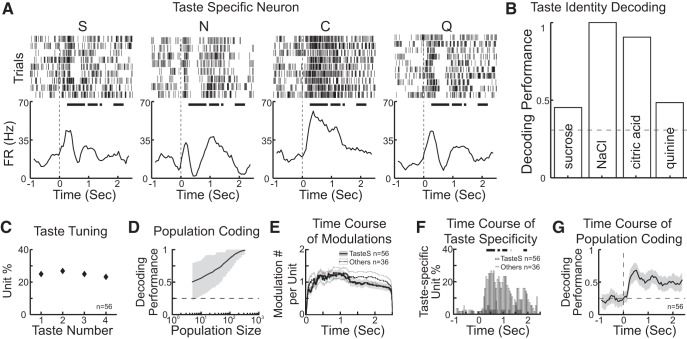

After characterizing the temporal dynamics of taste-evoked responses, a series of analyses were performed to determine how information pertaining to taste identity is encoded by VPMpc neurons. Each of the taste-responsive neurons was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA (time × taste) to identify whether it responded differently to the 4 tastants (Jezzini et al., 2013; Samuelsen et al., 2013). Neurons that were taste-responsive and showed significantly different responses to the 4 tastants according to the two-way ANOVA were defined as taste-specific. This method yielded 56 taste-specific units from 92 taste-responsive units, which accounted for 43.7% of all recorded units (56 of 128). Taste-specific units were analyzed with a Euclidean distance-based classification algorithm (Jezzini et al., 2013) to evaluate how many and which gustatory stimuli were encoded by each unit. Figure 3A shows a representative thalamic neuron whose firing is taste-specific. This neuron responded more strongly to citric acid; however, it did not encode exclusively for citric acid. The time course of this neuron's response was different for each of the tastants, allowing for an above chance classification performance of all 4 tastants (Fig. 3B, best two classifications for NaCl and citric acid). The coding profile of each VPMpc taste-specific neuron was analyzed. Similar percentages of neurons encoded for 1 (25%, 14 of 56), 2 (26.8%, 15 of 56), 3 (25%, 14 of 56), or 4 (23.2%, 13 of 56) taste qualities, as revealed by the distribution plot in Figure 3C. The average decoding performance of each taste-specific neuron was 0.43 ± 0.02 (n = 56). Performing the classification analysis using data from neuronal ensembles instead of single neurons led to higher performance. Using the entire group of 56 taste-specific neurons recorded led to a correct performance of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67, 0.92). To determine the size of the ensemble needed for a highly accurate performance (i.e., 95% correct), a surrogate population of thalamic neurons was created on the basis of response statistics of this group of taste-specific neurons (Jezzini et al., 2013; Rigotti et al., 2013). As Figure 3D shows, the minimal number of taste-specific, VPMpc-like neurons needed to reach 95% correct classification was 195.

Figure 3.

Taste identity coding in VPMpc. A, Representative raster plots and PSTHs for a taste-specific neuron responding to passively delivered S, N, C, and Q. Time 0 indicates when taste delivery occurs. PSTHs are smoothed by a moving window (250 ms, 50 ms step). Thick line above PSTHs indicates times at which responses to the 4 tastants are significantly different (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05, Bonferroni correction). B, Histogram representing the decoding performance for the representative neuron. Horizontal dashed line indicates the significance level. C, Distribution of units that encode for 1, 2, 3, or 4 taste qualities. D, Population decoding performance computed on the basis of virtual ensembles with increasing numbers of units. Horizontal dashed line indicates chance level. Shading represents the bootstrapped CI. E, Time course of firing rate modulations observed for taste-specific neurons (TasteS, solid line) and taste-responsive neurons that were not taste specific (Others, dashed line). Shading around traces represents SEM. F, Percentage of taste-specific neurons in the first 2.5 s following taste delivery. Empty bars represent taste-specific neurons (TasteS). Gray bars represent all the other taste-responsive neurons that were not taste-specific (Others). Time 0 indicates taste delivery. Thick line above the histogram indicates the time points in which the proportion of taste-specific neurons in TasteS group is significantly higher than that in the Others group (two-proportion z test, p < 0.05). G, Time course of decoding performance based on the entire population of taste-specific neurons (n = 56). Shading represents the bootstrapped CI. Horizontal dashed line indicates chance level (0.25) performance. Time 0 indicates taste delivery.

Next, we investigated the temporal evolution of firing activity in taste-specific neurons. Taste-specific neurons responded with modulations of firing rates that could occur at any time during the 2.5 s following taste delivery. The number of taste modulations was computed for each neuron and for each taste response. On average, each neuron could have 3.21 ± 0.42 (n = 56) modulations per 2.5 s, a number similar to that obtained for taste-responsive neurons that were not taste-specific (2.78 ± 0.22, n = 36, independent-samples t test, p = 0.46). The time course of firing rates modulations was also analyzed, revealing a homogeneous distribution over time (Fig. 3E). A series of additional analyses were performed to better understand the temporal evolutions of taste responses. To determine whether taste-specific neurons exhibited specific temporal signatures, we related their response patterns to the results of the PCA featured in Figure 2. The prevalence of different eigenvectors was analyzed for responses observed in taste-specific neurons and in taste-responsive neurons that were not taste-specific. Among all the responses from taste-specific neurons, 65.5% (78 of 119 responses) were dominated by PC1, 24.4% (29 of 119) by PC2, and 10.1% (12 of 119) by PC3. This distribution was not significantly different from the one observed in the group of taste-responsive neurons that were not taste-specific (PC1 dominated: 63.6%, 49 of 77 responses; PC2 dominated: 22.1%, 17 of 77; PC3 dominated: 14.3%, 11 of 77; χ2 goodness of fit test, p = 0.40). These results suggest that taste-specific neurons do not produce temporal patterns of spiking that are significantly different from those produced by the rest of thalamic neurons.

To assess how information is encoded during the time course of a response, we performed ANOVA-based and classification-based analyses using a moving window (250 ms window, 50 ms step) on the 2.5-s-long period following taste delivery. Figure 3F shows the proportion of taste-specific units that passed a one-way ANOVA test (p < 0.05, Bonferroni correction) at each time point. This analysis shows how many neurons were taste-specific at each time point following taste delivery. A significant number of neurons in VPMpc become taste-specific after the third bin (i.e., in the interval between 100 and 350 ms) following passive taste delivery. The largest number of taste-specific neurons occurred at ∼0.5 s, and taste specificity continued to be above baseline for most of the 2.5 s window examined. As control, the same analysis was applied to neurons that were not identified as taste-specific by the two-way ANOVA method (Fig. 3F, Others). As expected, this group showed very little taste specificity over time. The two histograms were significantly different (two-proportion test, p < 0.05) for most of the 2.5 s period examined. Figure 3G shows results from a moving-window decoding analysis based on the ensemble of all taste-specific neurons recorded. This analysis revealed the time course of the ensemble-based classification averaged across tastants. Also in this case, taste coding showed an early onset (i.e., classification became significantly above chance starting from the third bin; i.e., in the interval between 100 and 350 ms, following taste delivery), approached a peak at ∼0.5 s, and lasted to the end of the temporal window analyzed.

Processing of taste palatability in VPMpc

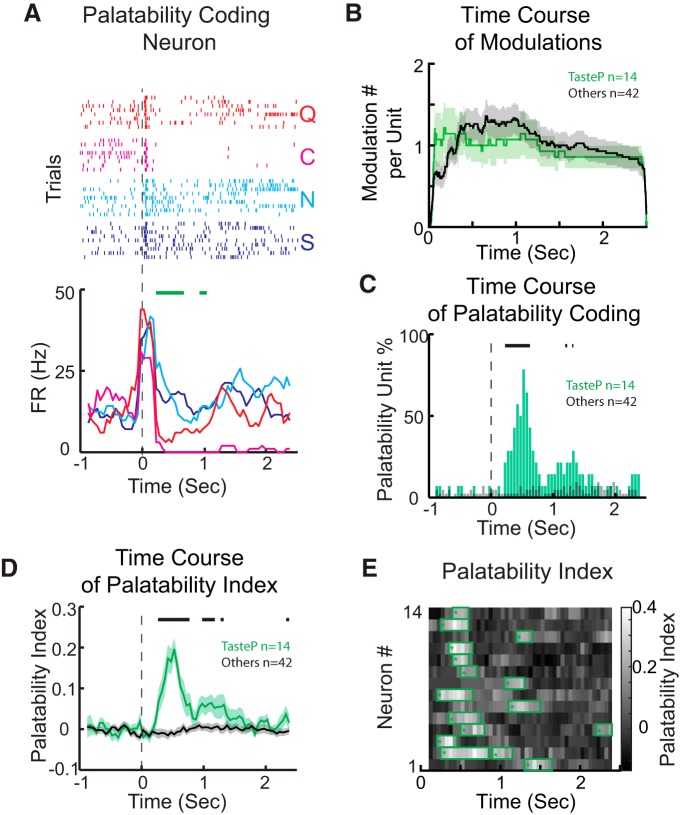

Taste identity is not the only feature processed by gustatory circuits. Neurons in GC (Yamamoto et al., 1985; Accolla and Carleton, 2008; Grossman et al., 2008; Sadacca et al., 2012), mPFC (Jezzini et al., 2013), BLA (Fontanini et al., 2009), and other taste-related regions (Li et al., 2013; Weiss et al., 2014) have been shown to encode information about taste palatability. Recordings from anesthetized rats suggested the presence of a possible “hedonic tone” in VPMpc as well (Verhagen et al., 2003). Visual inspection of recordings from alert rats confirms this prediction. Figure 4A features a representative example of a VPMpc neuron whose firing activity appears to encode the hedonic value of taste stimuli. Raster plots (Fig. 4, top panel) and PSTHs (Fig. 4, bottom panel) show a similarity of responses to tastants belonging to the same hedonic category. Indeed, between 250 ms and 1 s, responses to sucrose are similar to those evoked by NaCl, and responses to citric acid are similar to those evoked by quinine. To quantify the number of neurons coding for palatability, we computed a PI (see Materials and Methods) based on a within-neuron analysis of response similarity. The PI was computed only for the group of taste-specific neurons (n = 56). This stringent criterion was motivated by the consideration that neurons that were not taste-specific could not convey, by definition, information pertaining to taste. A neuron was classified as palatability coding if it responded similarly to tastants with similar palatability and differently to tastants with opposite palatability. Neurons were required to have a PI that was significantly above baseline for at least 200 ms to be defined as palatability coding. According to this analysis, 24% of the taste-specific neurons (14 of 56) appeared to be coding for palatability. This number represented 10.9% of the total number of neurons recorded (14 of 128). Recently, a second method was introduced to assess palatability coding (Piette et al., 2012; Sadacca et al., 2012). This analysis relies on the correlation between taste-evoked responses and hedonic ranking (i.e., sucrose > NaCl > citric acid > quinine). We adapted the same method and defined a neuron as palatability coding if the Spearman correlation coefficient was significant for at least 200 ms. Of the 56 taste-specific units, 19 turned out to be coding for palatability (33.9%), which accounts for 14.8% of total VPMpc units recorded (19 of 128).

Figure 4.

Taste palatability coding in VPMpc. A, Raster plots (top) and PSTHs (bottom) for a representative palatability-coding neuron. Responses to S and N (the palatable pair) are excitatory, whereas responses to C and Q (the aversive pair) show a sharp decline followed by inhibition. Green bars represent the time at which the palatability index is significant. B, Time course of response modulations observed for palatability-coding neurons (TasteP, green line) and taste-specific neurons that were not palatability-coding (Others, black line). Shading around traces represents SEM. C, Time course of the percentage of palatability-coding neurons. Green bars represent the percentage of palatability-coding neurons at a given moment within the palatability-coding neuron group (TasteP). Gray bars represent, as a control, the percentage of cells in the group of taste-specific neurons that were not coding for palatability (Others). Thick lines above the histogram indicate the time points at which the proportion of palatability-coding neurons in TasteP is significantly different from that in Others (two-proportion z test, p < 0.05). D, Analysis of the palatability index over 2.5 s following taste delivery. Green line indicates the index computed for palatability-coding neurons (TasteP, n = 14). Black line indicates the palatability index computed, as control, for neurons that are taste-specific, but not palatability-coding (Others, n = 42). Thick lines above the traces indicate the period in which the palatability index for palatability-coding neurons is significantly different from Others (independent-samples t test, p < 0.05). E, Pseudocolor plot showing the palatability index over 2.5 s following taste delivery for all the palatability-coding neurons. Green boxes represent the periods in which the PI is significantly above baseline.

A series of analyses were performed to investigate the dynamics of palatability-related firing. First, responses for each palatability-coding neuron were related to the different firing patterns described by the PCA outlined in Figure 2D. Taste responses of palatability-coding neurons showed the following distribution: 68.8% (22 of 32 responses) were dominated by PC1, 18.8% (6 of 32) by PC2, and 12.5% (4 of 32) by PC3. This distribution was similar to the one observed for the group of taste-specific neurons that did not code for palatability (64.4%, 56 of 87 responses, were dominated by PC1, 26.4%, 23 of 87, by PC2, and 9.2%, 8 of 87, by PC3; χ2 goodness of fit test, p = 0.55). This analysis excludes the existence of specific patterns of firing characteristic of palatability coding. To complement this observation, we computed the number of modulations observed for each palatability-coding neuron over 2.5 s following taste delivery. On average, 3.21 ± 0.56 modulations were observed for each palatability-coding neuron (n = 14), a number similar to the one observed for taste-specific neurons that did not code for palatability (3.21 ± 0.53, n = 42, independent-samples t test, p = 1). Figure 4B shows how firing rate modulations could occur at any time in the window under examination.

To determine how the time course of activity translated into processing of palatability, we computed the number of neurons that were coding for hedonic value in each 250 ms bin (50 ms step) after taste delivery. Figure 4C shows that the number of neurons coding for palatability rises at ∼0.2 s and peaks at ∼0.5 s. The number of palatability-coding neurons shows a second peak at ∼1.3 s before reaching baseline between 1.5 and 2 s. As a control, the number of taste-specific neurons that were not coding for palatability was plotted and showed no modulation. A similar time course was revealed by analyzing the time course of the palatability index. Figure 4D, E shows the PI averaged across palatability-coding neurons and a heat map of PI for each neuron, respectively. Both suggest the presence of two waves of significant PI elevations. Among 14 palatability-coding neurons, 10 showed early onset of palatability coding (before 0.5 s), 6 had late modulation (after 0.75 s), and two of these six neurons showed early and late modulations. The number of neurons showing both early and late modulations is similar to the one expected by the relative proportions of neurons in the two groups. This result suggests that the two waves of palatability information might not converge on the same neurons.

Together, these results indicate that neurons in VPMpc of alert rats can encode not only taste quality, but also taste palatability, and that palatability coding emerges soon after taste delivery.

Effects of general expectation on taste coding

Studies in several sensory systems demonstrated that thalamic responses depend upon the behavioral state of the animal (Cano et al., 2006; Lesica et al., 2006; McAlonan et al., 2008; Saalmann and Kastner, 2011; Pais-Vieira et al., 2013). Previous work has identified general expectation as a state strongly affecting taste coding in GC (Samuelsen et al., 2012). To investigate whether gustatory processing in VPMpc varies depending on the general anticipatory state of the animal, we compared responses to self-administered (Self) and passively delivered (Passive) taste stimuli. Comparison of the number of taste-responsive neurons did not reveal any significant difference; 71.9% (92 of 128) of the neurons recorded responded to Passive and 64% (82 of 128) to Self (two proportion z test, p = 0.18) taste stimuli. A similar proportion of neurons was taste-specific in the two conditions (Self: 63 of 128, 49.2% vs Passive: 56 of 128, 43.7%, two proportion z test, p = 0.38). However, we observed significant differences in firing rates and taste-response profiles in the two conditions. When analyzing the entire response averaged over 2.5 s, 36.7% (47 of 128) of neurons significantly changed their firing rates depending on whether tastants were passively or self-delivered (paired-samples t test, p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction). When the analysis was restricted to neurons that were either taste-responsive or taste-specific in at least one of the two delivery conditions, the proportion of cells that significantly changed firing rates was 40.1% (43 of 105 taste-responsive neurons in the two conditions) and 46.3% (38 of 82 taste-specific neurons in the two conditions), respectively. Of the taste-responsive neurons that were modulated by the behavioral state (n = 43), 34.8% (15 of 43) increased, 62.8% (27 of 43) decreased their firing activity, and 2.3% (1 of 43) had mixed effects across the four taste stimuli, in response to Self, compared with Passive deliveries. In addition to changes in firing rates, neurons changed their response profiles to the 4 tastants. For this analysis, we compared response profiles with a three-way ANOVA (taste × condition × time) for neurons that were taste-specific in either one of the delivery conditions (n = 82). A total of 62.2% (51 of 82) of neurons had significantly different taste response profiles depending on the condition. Additional analyses of single neuron ability to encode for single or multiple tastants was performed on taste-specific neurons using a classification algorithm. We observed significant differences in the number of taste qualities encoded by each neuron. In the case of Passive deliveries, an equal proportion of neurons classified above chance for 1, 2, 3, or 4 tastants (24.4% [20 of 82], 26.8% [22 of 82], 28% [23 of 82], and 18.3% [15 of 82], respectively; two neurons did not allow for above-chance classification in the Passive condition). In contrast, in the case of Self deliveries, neurons classifying only one taste quality represented the minority, and the majority of neurons encoded for four qualities (6.1% [5 of 82] of neurons encoded for one taste quality, 31.7% [26 of 82] for two taste qualities, 24.4% [20 of 82] for three taste qualities, and 37.8% [31 of 82] for four taste qualities). The two distributions were significantly different (χ2 goodness of fit test, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5A). A post hoc comparison revealed that significantly more neurons classified 4 tastants (two-proportion z test, p < 0.01) and fewer classified 1 tastant (two-proportion z test, p < 0.01) in Self relative to Passive. Figure 5B shows a representative neuron's responses to passively delivered and self-administered tastants. The histogram on the right represents the classification performance for this neuron, which can encode for three stimuli in the case of Self but only one for Passive.

Figure 5.

State dependency of taste coding. A, Proportion of neurons that encode 1, 2, 3, and 4 tastants when stimuli are either passively delivered (red, Passive) or self-administered (blue, Self). *Significant difference between the two distributions (χ2 goodness of fit test, p < 0.01). B, Raster plots (top) and PSTHs (bottom) for a representative neuron responding to the same stimuli either passively delivered (red) or self-administered (blue). Right, Histogram showing the decoding performance for the representative neuron, which encoded significantly just for C in the case of passive and for C, N, and Q in the case of self-administrations. Horizontal dashed lines indicate significant decoding level. C, Left, Decoding performance for passively delivered (red) and self-administered (blue) tastants. Horizontal dashed line indicates chance level. Right, Proportion of neurons decoding for different tastants in the two conditions. *Significance (two-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

To investigate whether this change in single neuron's ability to represent information about multiple taste qualities impacted coding, a series of analyses were performed. First, we compared the classification performance for neurons that encoded for one taste quality with that for neurons that encoded for four qualities. In the case of both Passive and Self, the group of neurons encoding for four qualities allowed for a significantly better average classification performance than the group of neurons encoding for only 1 tastant. In the case of Passive deliveries, the average classification performance was 0.31 ± 0.01 for the population encoding only one quality and 0.53 ± 0.02 for the population encoding four qualities (independent-samples t test, p < 0.01). The same was observed for Self deliveries, in which the classification performance was 0.26 ± 0.02 for neurons encoding only one quality and 0.58 ± 0.02 for neurons encoding four qualities (independent-samples t test, p < 0.01). The results of this analysis suggest that increasing the proportion of neurons encoding for 4 tastants, and decreasing the proportion of those encoding for 1 tastant (i.e., the change observed in the case of Self) should result in an overall improvement in taste coding. To test this hypothesis, we averaged the classification performance across neurons and compared it for the two conditions (i.e., Self and Passive). When the best classification performance (i.e., the classification for the “best” taste) was analyzed for each neuron, a higher coding performance was observed for responses to Self than Passive deliveries (0.75 ± 0.02 vs 0.70 ± 0.02, paired-samples t test, p < 0.05, n = 82). Furthermore, when the performance of each neuron in classifying all 4 tastants was computed and averaged, the overall classification was significantly better in Self compared with Passive deliveries (0.47 ± 0.01 for Self vs 0.40 ± 0.01 for Passive, paired-samples t test, p < 0.01, n = 82; Fig. 5C, left). Figure 5C (right) shows the percentage of units that significantly decode each of the 4 tastants, which confirms a higher classification performance for Self (two-way ANOVA [taste × condition], p < 0.05). The improvement of taste coding for self-administered tastants was further confirmed by ensemble-based classification. The population of taste-specific neurons analyzed (n = 82) led to a classification performance of 0.96 (CI: 0.92, 1) for Self and 0.79 (CI: 0.71, 0.96) for Passive. Virtual ensembles were constructed based on the statistics of the neurons that were taste-specific either in Self or Passive; the size of the population required for accurate classification (i.e., 95%) was 65 in the case of Self and 120 in the case of Passive deliveries.

Additional analyses were performed to determine whether expectation changed the coding of palatability. The prevalence of palatability-coding neurons was not significantly affected by expectation (17.9%, 23 of 128, in the case of Self and 10.9%, 14 of 128, in the case of Passive, two-proportion z test, p = 0.11). Similarly, a comparison of the palatability index in the two conditions did not reveal any significant difference (66 bins, independent-samples t test, p > 0.05).

Together, these results suggest that, in the case of self-administered tastants, neurons improved their ability to represent multiple taste qualities compared with the Passive condition. This effect resulted in enhanced taste coding, but no difference was observed in palatability coding.

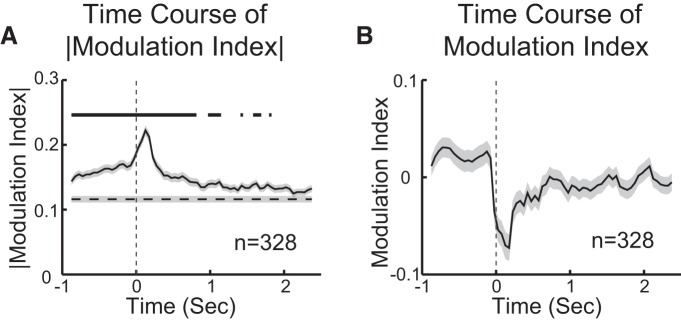

Effect of general expectation on temporal dynamics

To understand the effects of expectation on the time course of taste responses, we analyzed response dynamics in neurons that were taste-specific either in Self or Passive conditions (82 of 128). To determine whether the effects of expectation were mediated by differences in the magnitude of taste-evoked activity over time, an MI based on differences in auROC was computed for each taste response of each neuron (n = 328) (see Materials and Methods). The absolute value of MI was used to assess the time at which the largest state-dependent change in activity occurred. Figure 6A shows that the absolute value of MI is significantly different from baseline for more than half of our analysis period (−1 to 2.5 s; independent-samples t test, p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction), with a peak at bin 0–250 ms. Prestimulus increases in MI are likely related to the presence of the cue signaling the time for self-administration. The signed MI was examined to determine whether the early difference in responses was biased toward Self or Passive (Fig. 6B). A bias toward an early reduction of responses to Self was observed, with the largest reduction occurring in the 50–300 ms bin. This observation was confirmed by examining the percentage of responses that, in the 50–300 ms bin, showed a significant reduction in firing frequency in the case of Self (37.2%, 122 of 328, of responses showing a reduction with Self compared with 17.7%, 58 of 328, showing an increase with Self).

Figure 6.

Effects of the behavioral state on taste-evoked activity. A, Time course of the absolute modulation index for neurons that were taste-specific in either condition (n = 82 neurons × 4 tastants). Dashed line indicates baseline level of the modulation index. Shading around the trace represents SEM. Thick line above the trace indicates the time points in which the modulation index is significantly above baseline (independent-samples t test, p < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction). B, Time course of the signed modulation index. Shading around the trace represents SEM. The negative modulation index shortly after time 0 (i.e., taste delivery) indicates that responses to Passive are overall larger than responses to Self.

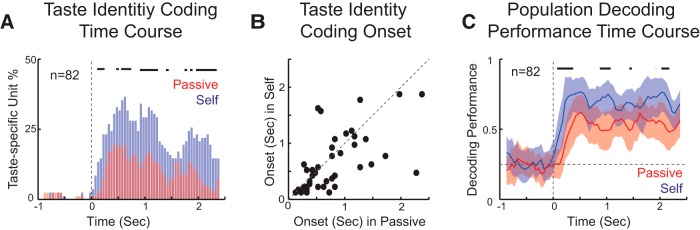

Additional analyses were performed on the group of neurons that were taste-specific, either in Passive or Self delivery (n = 82), to determine the impact of expectation-dependent changes on the dynamics of taste coding. First, we compared the time course of the percentage of taste-specific neurons for each time bin in the two conditions. This analysis revealed differences starting shortly after stimulus delivery and appearing throughout the 2.5 s period. As shown in Figure 7A, significantly more neurons were taste-specific in the case of Self compared with Passive. Interestingly, whereas only a few neurons were taste-specific in the first two bins (i.e., 0–250 and 50–300 ms) following Passive deliveries, neurons began to show taste specificity as early as the first bin (i.e., 0–250 ms) in the case of self-administration. The proportion of taste-specific neurons was significantly larger for Self relative to Passive in the bins: 0–250, 50–300, and 100–350 ms (two-proportion z test, p < 0.05). This result was further confirmed by the results in Figure 7B, showing a significantly shorter latency of taste coding for Self compared with Passive in the subset of neurons for which the onset of coding could be detected (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.05, n = 47). Analysis of the time course of coding confirmed this result. Both the average of single-neuron classification performance (data not shown) as well as the population-based classification performance (Fig. 7C) revealed a similar phenomenon. The average taste classification performance was higher for Self-administration, and the increase in performance showed an early onset but was not limited to the early phase of the response.

Figure 7.

Effects of the behavioral state on the time course of coding. A, Time course of identity coding for passively delivered and self-administered tastants. Percentage of taste-specific neurons in the first 2.5 s following passive delivery (red represents Passive) or self-delivery (blue represents Self). Time 0 indicates onset of delivery. Thick lines above histograms indicate the time points at which the histograms for the two conditions are significantly different (two-proportion z test, p < 0.05). B, Comparison of the onset of taste coding for Passive and Self. Each dot indicates the onset of coding for each cell in the two conditions (n = 47). C, Time course of decoding performance based on the entire population of taste-specific neurons. Red represents Passive. Blue represents Self. Shading around tracing represents the bootstrapped CI. Thick lines above traces indicate the time points at which decoding is significantly different (bootstrap procedure, p < 0.05).

Finally, a series of analyses were performed to determine whether neurons that were modulated by expectation displayed characteristic responses to passively delivered stimuli. First, we compared the number of firing rate modulations over 2.5 s following taste for neurons modulated and neurons not modulated by expectation. A neuron was defined as affected by expectation if a three-way ANOVA test (taste × time × condition) held a p < 0.01 for the terms, including condition. No significant difference was observed (modulated: 2.70 ± 0.28, n = 63 vs not-modulated: 3.05 ± 1.04, n = 19, independent-samples t test, p = 0.65), indicating that the propensity to be affected by expectation did not correlate with a larger number of firing rate modulations. In addition, PCA was performed to determine whether neurons that were modulated by expectation featured specific patterns of firing. The prevalence of responses with patterns of activity described in Figure 2D was computed for cells modulated by expectation and cells not modulated by expectation. Responses from cells modulated by expectation had the following distribution: 67.8% (82 of 121 responses) of responses were dominated by PC1, 22.3% (27 of 121) by PC2, and 9.9% (12 of 121) by PC3. Although this distribution was statistically different from the one observed for responses in neurons not modulated by expectation (PC1 dominated: 54.5%, 18 of 33; PC2 dominated: 30.3%, 10 of 33; PC3 dominated: 15.1%, 5 of 33; χ2 goodness of fit test, p < 0.05), the difference was small. A post hoc analysis revealed that only the proportion of PC1-dominated responses was different (χ2 goodness of fit test, p < 0.05), suggesting that neurons that are modulated by expectation tend to have monophasic responses more frequently than those that are not modulated by expectation.

Discussion

The results presented here provide novel evidence on how VPMpc of alert rats encodes gustatory information. Multielectrode recordings revealed that intraorally delivered tastants significantly modify firing rates in a large percentage of VPMpc neurons. Firing rate modulations were typically time-varying. Approximately half of the neurons recorded produced responses that were taste-specific; and, with the exception of 25% of the neurons, most of the cells encoded for more than one taste quality. Neurons in VPMpc also encoded palatability. The experiments presented here also provide evidence that thalamic coding of taste is state-dependent. Generally expected stimuli (i.e., cued and self-administered tastants) were encoded more effectively and more rapidly than passively delivered tastants. The enhancement in classification performance is related to an increase in the number of tastants being encoded by each neuron.

Thalamic coding of passively delivered tastants

Approximately half of VPMpc neurons encode the chemical identity of a gustatory stimulus passively delivered directly in the mouth of the animal. This result is in agreement with previous findings in anesthetized rodents (Verhagen et al., 2003). As a population, taste-specific thalamic neurons encode taste quite effectively. The performance of an ensemble comprising all the taste-specific neurons recorded was 0.7–0.8 (i.e., tastants were encoded correctly in 70%–80% of the passive delivery trials, depending on the population used for analysis). A decoding analysis performed on virtual populations of thalamic neurons demonstrated that an ensemble of only 120–195 (depending on the template population used) neurons was needed to correctly classify taste quality in 95% of the trials.

Analysis of the breadth of tuning revealed that just 25% of the neurons encoded for a single taste quality, when stimuli were delivered unexpectedly via intraoral cannula. This result is consistent with a progressive reduction in selectivity observed as gustatory information goes from the periphery to the cortex. In the PbN, ∼40% of neurons respond exclusively to a single taste quality when tastants were intraorally delivered (Nishijo and Norgren, 1990), although neurons responding to actively licked tastants were recently reported to be more broadly tuned (Weiss et al., 2014). In the case of GC, previous work showed that the percentage of neurons encoding only for a single tastant is limited to 10% (Jezzini et al., 2013). The reduction in single taste specificity from PbN to VPMpc suggests a convergence of parabrachial inputs encoding different single qualities onto VPMpc neurons. A similar convergence can be envisioned for VPMpc projections to GC.

Further evidence that neurons in VPMpc integrate more than just the physiochemical properties of a single tastant comes from results demonstrating their ability to code for palatability. The data presented here confirm in alert rats a suggestion coming from experiments in anesthetized animals (Verhagen et al., 2003). Relying on two analyses previously validated for GC, hypothalamus, amygdala, and medial prefrontal cortex (Fontanini et al., 2009; Piette et al., 2012; Sadacca et al., 2012; Jezzini et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013), we found that a group of taste-specific neurons is responsible for processing palatability.

Not all of the neurons that responded to taste were chemosensory or palatability coding. Although our data do not provide any direct evidence on the function of these neurons, it is reasonable to propose that they may be involved in coding multisensory information associated with taste. Previous experiments in anesthetized animals show that VPMpc neurons can encode also tactile and thermic information (Verhagen et al., 2003).

Temporal dynamics of taste coding and sources of information

Identifying the sources of chemosensory and palatability signals to VPMpc is beyond the scope of this investigation. However, an analysis of the temporal dynamics of thalamic responses might provide some hints. Thalamic coding of gustatory information is rapid and persistent. Neurons become taste-specific ∼225 ms after stimulus delivery, reach a peak at ∼525 ms, and continue to be taste-specific for at least 2.5 s. Although the early onset is likely due to a rapid inflow of information coming from the PbN, the persistency of responses may be the result of recurrent interactions of VPMpc with PbN and GC (Yamamoto et al., 1980; Jones et al., 2006; Sherman, 2012). Reciprocal connections between the gustatory thalamus, PbN, and GC are well documented (Allen et al., 1991; Shi and Cassell, 1998; Holtz et al., 2015). The multiphasic changes in firing rates observed with the PCA, although not associated with a specific functional specialization of neurons, might indeed reflect waves of information arising from different sources.

Similar interactions might be responsible for palatability coding in the thalamus. The time course of palatability coding revealed potentially two palatability epochs: one peaking ∼450 ms and the second occurring ∼1 s after taste delivery. The early phase of palatability coding precedes the palatability epoch observed in GC (Katz et al., 2001; Piette et al., 2012; Sadacca et al., 2012; Jezzini et al., 2013) and might depend on inputs from the PbN (Ogawa et al., 1987; Yamamoto et al., 1994; Karimnamazi and Travers, 1998; Bester et al., 1999; Krout and Loewy, 2000; Söderpalm and Berridge, 2000; Holtz et al., 2015). The protracted palatability phase, on the other hand, is likely arising from interactions with GC. Our data suggest that the two waves of palatability information might not converge on the same neurons.

State dependency of thalamic taste processing

To investigate the state dependency of thalamic taste coding, we analyzed responses to stimuli that were either passively delivered or self-administered following a cue. Almost 37% of all the neurons recorded had different responses depending on whether tastants were generally expected or not. Firing rates differed in the two conditions even before taste delivery, likely a result of anticipatory changes in firing (Pritchard et al., 1989; Krupa et al., 2004; Samuelsen et al., 2012, 2013; Pais-Vieira et al., 2013). The difference in firing activity peaked shortly after stimulus delivery (between 0 and 250 ms) and lasted up to 2 s. The overall effect was a reduction of firing rates in the case of self-administrations compared with passive deliveries. However, this effect was not dominant, as a large percentage of neurons also showed an increase in firing rates in the case of self-administration. Despite the mixed effects on overall firing rates, self-deliveries were associated with an improvement in taste coding both at the single neuron level and at the population level. The effects of expectation were limited to taste coding and were not observed for palatability coding. A significant change in the breadth of coding was observed. In the case of passive deliveries, 24.4% of the neurons encoded for only a single tastants and 18.3% for all 4 tastants. General expectation enhanced the ability of single neurons to encode for more tastants; in this condition, only 6.1% of the neurons encoded for only 1 tastant and 37.8% for all 4 tastants. Our results emphasize the advantage of dense representations compared with narrow tuning; a population of neurons encoding for more tastants allows for better taste classification compared with a population of narrowly tuned neurons. In addition, these results indicate that the tuning of gustatory neurons is not fixed and hard wired but rather dependent on the state of the animal. Our experimental evidence is also consistent with results from recordings in brainstem and in GC, showing significant differences in tuning for neurons recorded from animals in different behavioral states (Nishijo and Norgren, 1990; Fontanini and Katz, 2008; Chen et al., 2011; Yoshida and Katz, 2011; Samuelsen et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2014). According to this view, taste coding does not rely on a unique scheme but is dynamically modulated by the state of the animal. This conclusion is in accord with recent theoretical results emphasizing the importance of modulating the sparseness of representations to achieve an ideal balance between generalization and discrimination (Barak et al., 2013).

An additional effect of general expectation was an increase in the speed of taste coding. This result dovetails nicely with the data recently reported for GC (Samuelsen et al., 2012), in which it is shown that a similar paradigm accelerates taste coding. Whether the phenomenon observed here for the thalamus is the cause of the effect observed in GC is not known, but it is reasonable to speculate that it might play a role. As for the sources of this modulation in VPMpc, given the presence of well-described cue-responses in GC (Samuelsen et al., 2012), it is reasonable to speculate that corticothalamic inputs might play a role in priming VPMpc neurons to receive sensory inputs. In addition, although very few data exist on neuromodulatory projections in VPMpc, it is likely that these inputs might also play a role in modulating VPMpc activity, similar to that observed for other thalamic nuclei (Hallanger et al., 1987; Sherman, 2012; Varela, 2014).

In conclusion, despite occupying a crucial position in taste pathways, VPMpc remains a relatively understudied thalamic nucleus. Indeed, little is known about how VPMpc processes gustatory information in alert rodents. Our results show that VPMpc neurons are broadly tuned to multiple taste qualities and dynamically encode taste quality and palatability. By studying taste coding in two different conditions, we were able to demonstrate that temporal dynamics as well as taste tuning are state-dependent and affected by the general expectation of taste. These results demonstrate the importance of taking into account the behavioral state of the animal when investigating coding schemes in taste.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01-DC010389 and the Klingenstein Foundation Fellowship to A.F. We thank Amy Cheung for help with histological procedures; Mrs. Martha Stone and Drs. Matthew Gardner, Luca Mazzucato, Chad Samuelsen, Ahmad Jezzini, Santiago Jaramillo, Dinu Florin Albeanu, and Arianna Maffei for technical help and/or insightful discussions.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Accolla R, Carleton A. Internal body state influences topographical plasticity of sensory representations in the rat gustatory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4010–4015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708927105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GV, Saper CB, Hurley KM, Cechetto DF. Organization of visceral and limbic connections in the insular cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;311:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.903110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak O, Rigotti M, Fusi S. The sparseness of mixed selectivity neurons controls the generalization-discrimination trade-off. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3844–3856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2753-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173–198. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester H, Bourgeais L, Villanueva L, Besson JM, Bernard JF. Differential projections to the intralaminar and gustatory thalamus from the parabrachial area: a PHA-L study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:421–449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990322)405:4<421::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;3B2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin PA, Spector AC, Grill HJ. A quantitative comparison of taste reactivity behaviors to sucrose before and after lithium chloride pairings: a unidimensional account of palatability. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:820–836. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.106.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M, Bezdudnaya T, Swadlow HA, Alonso JM. Brain state and contrast sensitivity in the awake visual thalamus. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1240–1242. doi: 10.1038/nn1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Gabitto M, Peng Y, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. A gustotopic map of taste qualities in the mammalian brain. Science. 2011;333:1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1204076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JY, Haesler S, Vong L, Lowell BB, Uchida N. Neuron-type-specific signals for reward and punishment in the ventral tegmental area. Nature. 2012;482:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature10754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo PM, Platt D, Victor JD. Information processing in the parabrachial nucleus of the pons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:365–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Katz DB. 7 to 12 Hz activity in rat gustatory cortex reflects disengagement from a fluid self-administration task. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:2832–2840. doi: 10.1152/jn.01035.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Katz DB. State-dependent modulation of time-varying gustatory responses. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:3183–3193. doi: 10.1152/jn.00804.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Katz DB. Behavioral states, network states, and sensory response variability. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1160–1168. doi: 10.1152/jn.90592.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Katz DB. Behavioral modulation of gustatory cortical activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:403–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Grossman SE, Figueroa JA, Katz DB. Distinct subtypes of basolateral amygdala taste neurons reflect palatability and reward. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2486–2495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3898-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Fairhurst S, Balsam P. The learning curve: implications of a quantitative analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13124–13131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404965101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MP, Fontanini A. Encoding and tracking of outcome-specific expectancy in the gustatory cortex of alert rats. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13000–13017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1820-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Norgren R. The taste reactivity test: II. Mimetic responses to gustatory stimuli in chronic thalamic and chronic decerebrate rats. Brain Res. 1978;143:281–297. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SE, Fontanini A, Wieskopf JS, Katz DB. Learning-related plasticity of temporal coding in simultaneously recorded amygdala-cortical ensembles. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2864–2873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4063-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallanger AE, Levey AI, Lee HJ, Rye DB, Wainer BH. The origins of cholinergic and other subcortical afferents to the thalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;262:105–124. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz SL, Fu A, Loflin W, Corson JA, Erisir A. Morphology and connectivity of parabrachial and cortical inputs to gustatory thalamus in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:139–161. doi: 10.1002/cne.23673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo S, Zador AM. The auditory cortex mediates the perceptual effects of acoustic temporal expectation. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:246–251. doi: 10.1038/nn.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezzini A, Mazzucato L, La Camera G, Fontanini A. Processing of hedonic and chemosensory features of taste in medial prefrontal and insular networks. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18966–18978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2974-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LM, Fontanini A, Katz DB. Gustatory processing: a dynamic systems approach. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LM, Fontanini A, Sadacca BF, Miller P, Katz DB. Natural stimuli evoke dynamic sequences of states in sensory cortical ensembles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18772–18777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705546104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimnamazi H, Travers JB. Differential projections from gustatory responsive regions of the parabrachial nucleus to the medulla and forebrain. Brain Res. 1998;813:283–302. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00951-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DB, Simon SA, Nicolelis MA. Dynamic and multimodal responses of gustatory cortical neurons in awake rats. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4478–4489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04478.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]