Abstract

There is promising evidence that poverty-targeted cash transfer programs can have positive impacts on adolescent transitions to adulthood in resource poor settings, however existing research is typically from small scale programs in diverse geographic and cultural settings. We provide estimates of the impact of a national unconditional cash transfer program, the Kenya Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children, on pregnancy and early marriage among females aged 12 to 24, four years after program initiation. The evaluation was designed as a clustered randomized controlled trial and ran from 2007 to 2011, capitalizing on the existence of a control group, which was delayed entry to the program due to budget constraints. Findings indicate that, among 1,549 females included in the study, while the program reduced the likelihood of pregnancy by five percentage points, there was no significant impact on likelihood of early marriage. Program impacts on pregnancy appear to work through increasing the enrollment of young women in school, financial stability of the household and delayed age at first sex. The Kenyan program is similar in design to most other major national cash transfer programs in Eastern and Southern Africa, suggesting a degree of generalizability of the results reported here. Although the objective of the program is primarily poverty alleviation, it appears to have an important impact on facilitating the successful transition of adolescent girls into adulthood.

Keywords: Kenya, Cash transfers, adolescent girls, pregnancy, early marriage

1. Introduction

The period between adolescence and adulthood marks a significant stage of growth in a young’s woman life, wherein her transition to marriage and fertility have critical impacts on her future life trajectory and wellbeing. In developing countries, the dynamics and age at which these transitions occur are key concerns, not only for their association with human capital development, but also because of close linkages between poverty, health, vulnerability, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk, autonomy, intimate partner violence and other factors (Jewkes et al., 2001; Bearinger et al., 2007; Jewkes et al., 2001; Jain & Kurz, 2007; Walker, 2012). Despite recent improvements in child marriage prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), an average of 41% of women aged 20 to 24 were first married or in a union before or by age 18 (UNICEF, 2011; Walker, 2012). In addition, estimates indicate that approximately 16 million girls aged 15 to 19 give birth each year, and nearly all (approximately 95 percent) of these births take place in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (WHO, 2014a). Young age at pregnancy increases the risk of harm for the mother and child, and delivery complications are estimated to be a leading cause of death for adolescent girls in developing countries (WHO, 2014b).

Research has shown that there is a bidirectional relationship between household-level poverty and early marriage and pregnancy. Poverty both influences the timing of life transitions, and is itself a consequence of early transitions. Poor households, or girls themselves, may initiate early marriage as an economic strategy to alleviate the household’s consumption burden, secure future welfare and chances at life, or improve the family’s socioeconomic status (Sanyukta et al., 2003; Oleke et al., 2006; Palermo & Peterman, 2009; Walker, 2012). Poor women may be more likely to have multiple partners, engage in transactional sex or be placed in sexually compromising relationships because of lack of other opportunities, or exposure to unsafe environments (Halperin & Epstein, 2004; Hallman, 2005; Robinson & Yeh, 2011). In communities where HIV infection rates are high, early marriage is socially perceived as a health protection strategy, though some studies from SSA find that married women are more likely to be infected by their partners as compared to their unmarried peers, due to the confluence of factors described above (Clark, 2004; Kelly et al., 2003; Glynn et al., 2001). Poverty and age at first pregnancy are both intertwined with education, further handicapping vulnerable young women and households from curbing the cycle of low human capital development and economic security.

In a recent systematic review of strategies that work to reduce adolescent childbearing in LMICs, McQueston and colleagues (2013) Social cash transfers (SCTs) were recommended as one of the three successful program types to reduce adolescent fertility. Despite this recommendation, the geographic spread and program design of the reviewed SCTs are diverse and present challenges to external validity, while the literature around impact pathways responsible for effects on adolescent reproductive health outcomes remains thin. Therefore, when SCTs are not designed to affect adolescent outcomes such as early marriage and pregnancy, leading to limitations around sample sizes and availability of indicators, it is difficult to identify the age groups, contexts and pathways through which we may replicate positive results.

This study examines the Government of Kenya’s main anti-poverty program, the Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (CT-OVC), and analyzes impacts on early pregnancy and marriage among females aged 12 to 24 at the four-year follow-up in 2011. The program is a large-scale unconditional cash transfer (UCT), meaning that receipt of cash is not tied to any specific behavior or compliance of the household, as is the case in a conditional cash transfer (CCT). The evaluation was designed as a clustered randomized controlled trial (RCT), capitalizing on the existence of a control group, which was delayed entry to the program due to budget constraints. However, since prioritization of elderly-headed households took place in treatment communities where eligible households exceeded budget allocations and no such prioritization was given in control communities, the evaluation framework can be characterized as quasi-experimental. The study adds to a growing but scarce literature on how SCTs impact adolescent fertility and marriage, and is the first to address these dynamics in the context of a national UCT targeted at the household-level in Africa. Furthermore, we examine pathways through which the Kenyan CT-OVC may affect early pregnancy, including increased education and mobility, specifically adolescence in-migration to study households. Since the findings are from a national program that is similar in design and operation to many other national SCTs in Africa whose main objective is also poverty alleviation, our findings have policy and programmatic implications well beyond Kenya.

2. Social cash transfers, fertility and marriage

2a. Social cash transfers and safe transitions to adulthood: A framework

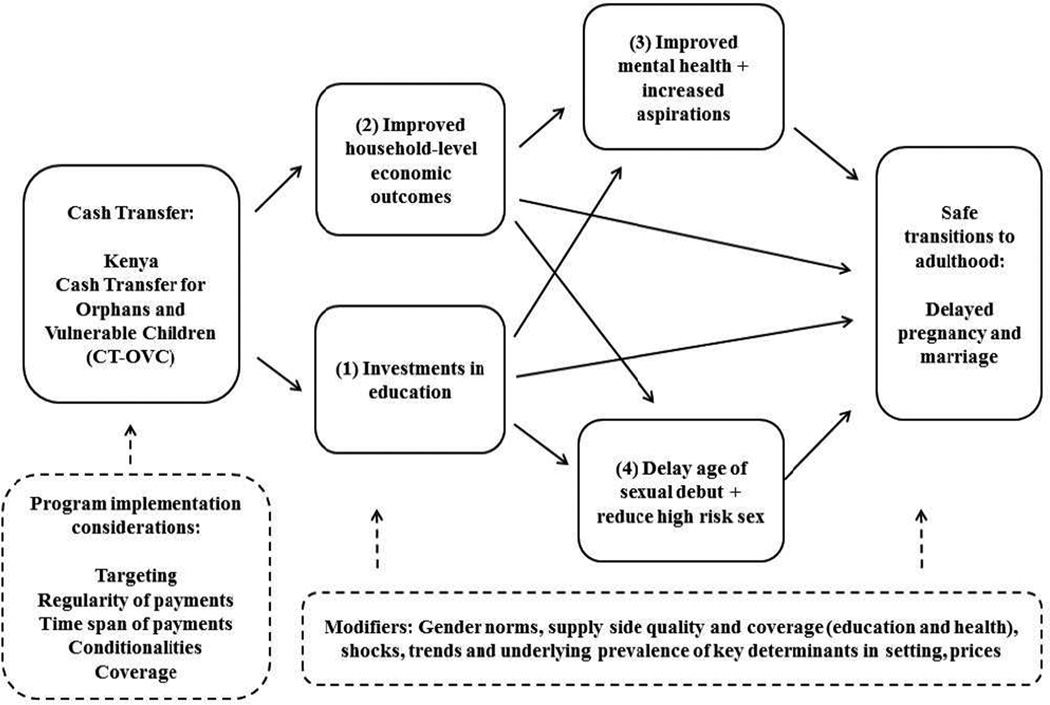

Economic theory of household decision making underlies our analysis, in which households make decisions on the quantity and quality of time and resources invested in their children’s human capital (health, education, wellbeing) in order to maximize household utility, subject to budget and time constraints (Strauss & Thomas 1995). Therefore, the adolescents’ final outcomes depend on individual-level inputs, household and community or environmental factors. Since the SCT is unconditional, the transfer acts as an increase in both overall monetary resources available to the household for increased adolescent-specific inputs, as well as a direct expansion of the budget constraint. To conceptually explore adolescent girls’ safe transitions into adulthood, we draw on previous frameworks (UNICEF et al. 2015) to identify four potential determinants (and associated pathways) which link SCTs to fertility and marriage outcomes: 1) increased investment in girls’ education, 2) increase in household economic stability, 3) improved mental health and increased aspirations of girls, and 4) delay of girls’ sexual debut and reduced high-risk sex. Figure 1 lays out the conceptual model for these pathways, where determinants (1) and (2) are more distal, and determinants (3) and (4) are more proximate to the outcomes themselves. In addition, there may be important modifiers of the relationships which may vary by underlying gender norms, supply side health or education quality and coverage, shocks, trends and prevalence of key factors in the setting, among others.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for cash transfers and girls safe transition to adulthood.

Notes: Modified from UNICEF et al. 2015

There are varying levels of evidence for each of the determinants and pathways explored here. Firstly, there is robust evidence that SCTs increase school enrollment and attendance across a variety of settings (Baird et al. 2011; Case et al. 2005; The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team 2012; Miller et al. 2008; Robertson et al. 2013). Education, especially primary school completion, has also been shown to delay the onset of fertility and marriage, and change fertility preferences (Behrman 2015; Lesthaeghe et al. 1985). Secondly, education protects a young woman’s short and long term well-being, as it may remove her from risky environments and endow her with the skills to improve her decision-making ability (Mensch & Lloyd 1998; Martin 1995). Finally, households often view school completion to be a prerequisite for marriage or childbearing, and thus follow social norms to delay these activities until education is completed (Cohen & Bledsoe 1993). As there are multiple pathways through which education has been found to directly and indirectly affect pregnancy and marriage outcomes, we expect that it will be an important protective factor in facilitating safe transitions to adulthood for girls in our sample.

There is also robust evidence that SCTs, and particularly UCTs in SSA, contribute to higher household economic security, and overall wellbeing, as measured by household poverty and consumption, including evidence from the Kenyan CT-OVC (Handa et al. 2014b; The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation team 2012a). Depending on the size of the transfer, the SCT has the ability to help sustain the household’s welfare during economic fluctuations and build resilience to shocks. These factors decrease the likelihood of the household needing to marry their daughter due to financial reasons (receipt of brideprice) or sending her to work in the market at an early age (Anderson 2007). Additionally, if some of the transfer is given directly to the girl, she may also be less likely to feel the need to earn her keep in the household or engage in transactional sex, which would contribute to more proximate determinants of safe transitions (Luke 2004; Maganja et al. 2007). There is some evidence that increased household economic security can also lead to decreased stress and overall increased mental health in the household. For example, the Give Directly RCT, a UCT in Western Kenya, found impacts on psychological wellbeing as measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. In particular, there were decreases in depression, stress, worry, and in the levels of the stress hormone cortisol among adults, all hypothesized to be a direct result of less poverty-related stress (Haushofer & Shapiro, 2013).

A smaller body of evidence points to impact pathways (3) and (4), improved mental health and increased aspirations of girls themselves, as well as delay of sexual debut and reduced high-risk sex. For example, a pilot RCT in Zomba, Malawi, which randomized unconditional transfers and transfers conditional on school attendance to girls aged 13 to 22, found that there were significant reductions in psychological distress, as measured by the General Health Questionnaire 12 screening instrument, among baseline school girls (Baird et al. 2013). Additionally, in the Kenyan CT-OVC, there was a 24 percent decrease in depressive symptoms, as measured by the CES-D, within a sample of adolescents aged 15 to 24; however, these impacts were driven primarily by boys (Kilburn et al. 2015). The Kenyan CT-OVC was also found to reduce the odds of sexual debut by 31 percent among the same age group, but there were no impacts on additional behavioral outcomes such as condom use, transactional sex or number of partners (Handa et al. 2014a). Using quasi-experimental methods, authors found that the South African Child Support Grant (CSG), a UCT, increased likelihood of abstaining from sexual behavior for females and engaging in sex with multiple partners for both males and females aged 15 to 17 (Heinrich et al. 2015). Cluver and colleagues (2015) also used quasi-experimental methods and found that the CSG decreased odds of transactional sex and age-disparate sex for girls aged 10 to 18, while no associations were found for boys. Therefore, there is not only support for pathways through distal determinants of schooling investments and household financial wellbeing, but also increasing evidence, particularly from UCTs in SSA, for more proximate determinants of safe transitions to adulthood.

Across all pathways, individual and household characteristics are expected to modify the determinants and pathways. In particular, age of the girl is an important modifier, where relatively younger and older adolescents are exposed to different sets of factors modifying pregnancy and marriage decisions. Finally, it is important to note that program implementation considerations, including targeting, regularity and span of payments, have implications for the expected impacts across the conceptual framework (see Figure 1). One of the key factors here is the time span of payments. If an adolescent is exposed to six months of payments, the potential for impact along the casual chain is relatively small, in comparison to exposure for three to four years, where the potential for impact is higher. For our outcomes in particular, since pregnancy or marriage have implications for migration of girls into new households, dynamics of in and out migration into study samples will be an important focus for evaluations seeking to parse out impacts and pathways. We return to this issue in later sections.

2b. Review of empirical literature: SCTs, early marriage and pregnancy

There is sparse, but increasing empirical evidence examining direct linkages between SCTs and pregnancy and marriage among young girls in developing countries. In addition to the studies reviewed by McQueston and colleagues (2013), we identify five studies that show that SCTs have the potential to affect adolescent marriage and childbearing. Gulematova-Swan (2009) used the well-known Mexican Oportunidades CCT evaluation data, from the urban expansion in 2002 to 2004, to show that young women living in intervention areas delayed both marriage and age at first and second pregnancies. Stecklov and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that across CCT evaluation samples in Mexico, Honduras and Nicaragua, fertility among women younger than age 20 decreased in households receiving transfers, though the effect was not significant in any setting. These CCTs generally included household co-responsibilities in order to receive benefits, such as health clinic visits for children under five, school enrollment and primary-aged children and attendance at monthly health education meetings. Alam and colleagues (2010), used a quasi-experimental case-control design to demonstrate that the Pakistani Female School Stipend Program, also a CCT targeted towards girls in sixth to eighth grades, increased age at marriage by 1.2 to 1.5 years over a six-year period. The same program had no impact on the probability of ever giving birth and only a weakly significant effect on the total number of live births.

The last two studies come from the African context, both introduced in the previous section. Baird and colleagues (2011) examined pregnancy and marriage among a sample of over 3,800 never-married Malawian girls aged 13 to 22 at baseline over a 24-month period. The study was conducted in the Zomba district and was designed as an RCT, and included both an unconditional arm, and an arm conditional on school attendance. Findings after two years indicated that the program reduced the likelihood of ever being pregnant and ever being married by 27 and 44 percent respectively. However, impacts were driven by the unconditional arm and by girls who dropped out of school after the start of the intervention. Finally, Heinrich and colleagues (2015) examined the effect of the South African CSG on a range of risky behaviors, including early pregnancy. The CSG was given to caregivers starting in 1998, with an explicit condition of school enrollment introduced in 2009. Heinrich and colleagues used eligibility and enrollment criteria and propensity score matching to identify program impacts and found that females aged 15 to 17 were 10.5 percentage points less likely to have experienced pregnancy.

In summary, although the evidence is promising, it is often mixed, or limited to a subgroup and specific geographic settings. Furthermore, the applicability of smaller field experiments such as the Zomba CCT, or larger programs such as the Latin American CCTs, to national UCTs in the African setting, is not clear. None of the existing national programs in Africa provide cash directly to the young woman (as was done in Zomba) and very few are conditional (as in Latin America). This paper addresses the question of whether such results are replicable at a nationwide-level and unconditionally, the latter of which is similar to most such programs operating in Africa.

3. The Kenyan Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children

The Kenyan CT-OVC was instituted mid-2007, implemented by Department of the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Development of the Government of Kenya and covered approximately 240,000 households nationwide as of 2014 (Mwasiaji, 2015). The program began with a small pre-pilot in 2004 followed by an initial expansion in 2006, which included the seven districts of Kisumu, Migori, Homa Bay, Suba, Nairobi and Garissa. Geographical targeting was determined by the Government of Kenya at the district level, with selection based on relative poverty and HIV prevalence. At the community-level or administrative unit of ‘Location,’ targeting was conducted in a two-stage process. Households qualified for the program based on the following characteristics: 1) the presence of at least one OVC under the age of 18 with at least one deceased parent, or whose parent or main caregiver is chronically ill; and 2) being ultra-poor, defined as belonging to the lowest expenditure quintile. Community members were elected democratically or appointed by the chief on the basis of their knowledge of the community to form Location OVC Committees (LOCs); members were asked to identify potentially eligible households within each community. Information and documentation in supporting the household’s qualification was gathered by LOCs during household visits and were sent to the program’s Monitoring and Evaluation group in Nairobi for verification. By June 2012, just after the last wave of data collection, the CT-OVC was estimated to cover approximately 150,000 households, or nearly 50% of the ultra-poor OVCs across 69 program districts, with representation in all 47 counties of Kenya (World Bank, 2012).

The CT-OVC program provides a monthly cash sum to eligible households of 1500 Kenyan Shillings (Ksh, USD $21), comprising nearly 20% of monthly total household expenditure; the level of the transfer was increased to Ksh 2000 per household in the 2011–2012 fiscal year to adjust for inflation. The CT-OVC is a UCT, and thus imposes no conditions for households receiving benefits, although at time of enrollment, beneficiaries were told that they were expected to use the money for the care and development of the OVC resident in the household. To foster gradual independence from the program, households with an OVC over the age of 18 are no longer eligible. Impact evaluation results using the 2007 to 2011 data indicate that the program employed effective targeting (Handa et al. 2012), increased human capital investment (The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team 2012b), increased household consumption of food and non-food items (The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team 2012a), thus meeting several important poverty-related targets.

4. Study design and data collection

4a. Overview of study design

The evaluation strategy for the Kenyan CT-OVC is a cluster randomized longitudinal design. The study covers four Locations in each of the seven districts selected for expansion, for a total of 28 Locations randomized to treatment (14 Locations) and control (14 Locations). Due to budget constraints, it was not possible to roll out the program to scale in all districts; consequently two Locations in each district were randomly chosen by lottery to serve as delayed-entry controls and the program was implemented in the other two Locations per district. In total, three rounds of data were collected. The baseline household survey was conducted between March and August 2007 preceding the program’s implementation during the same year. It contained 1,542 and 755 treatment and control households respectively (a ratio of 2:1), which were randomly selected via computer generated ranking in each Location (on average 110 and 54 households per Location in treatment and control households respectively). At that time, survey teams and households did not know their treatment status to avoid biases in responses and survey enumeration. Baseline sample sizes were determined based on power calculations in order to observe a change for the primary impact evaluation indicators of school enrollment (five percent), curative health care (20 percent), and per capita consumption (10 percent), accounting for possible intra-cluster correlation. The first follow-up (wave 2) was conducted roughly 24 months after baseline, (in 2009) and was comprised of 1,325 treatment and 583 control households. The second follow up (wave 3 in 2011) comprised 1,280 and 531 treatment and control households, respectively.

In each of the three rounds of data collection, household decision-makers were surveyed using a comprehensive demographic household survey asking about the household’s composition, characteristics of its membership (including education and marital status), monthly expenditures, assets, and agricultural productivity. In the 2011 third wave of the survey, a fertility module was introduced, which asked all female residents age 12 to 49 a series of questions regarding pregnancy, health behavior around birth, and other fertility history. Therefore, although the longitudinal data often include information on household and individual characteristics since the 2007 baseline, information on fertility is only available for one point in time in 2011. Further information on sample design is available elsewhere (Handa et al. 2012; Handa et al. 2014a). This study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethics Review Committee (Protocol #265) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina.

4b. Randomization at baseline and attrition

Since our outcome measures come from the 2011 wave of the survey, we relied on the successful randomization of the program at baseline to identify impacts. To check whether the randomization was successful, we ran summary statistics on key household characteristics at baseline. These results are presented in the first two columns of Supplementary Table A1, where the figures in bold indicate statistical significance at the p<0.10 level between treatment and control arms of the study in each wave. We found that households in each arm were well balanced in terms of poverty characteristics and geographical distribution, but that there were statistically significant differences in the age, sex and schooling levels of household heads across arms. These differences are likely due to the central Ministry’s prioritization process, which favored households headed by elderly, when the number of eligible households exceeded the budget in each Location. Since the final prioritization process was not conducted in control Locations, households in the control arm of the study were drawn from a slightly larger eligibility list, resulting in the differences in characteristics of heads of households observed in Supplementary Table A1. These characteristics are controlled for in subsequent analysis. It is important to note that there is no element of self-selection into the program; household eligibility is completely supply-driven and take-up is universal.

Although attrition levels at the household level were high between the baseline and first follow-up in 2009 (18 percent), corresponding with the political turmoil and election violence, we examine differential attrition at the household and individual level and find little evidence of differential attrition (see Supplementary material, Tables A2–A4). Thus we conclude that selective attrition is unlikely to be a concern in subsequent analysis.

5. Empirical strategy

We examine the likelihood of ever experiencing pregnancy (including current pregnancy) and ever being married or have co-habited among young women aged 12 to 24. These are cross-sectional estimates because fertility information was only collected in 2011 (wave 3 of the survey). Of the total number of women in the qualifying age group, 55 (3.3 percent of the analysis sample) were recorded in household rosters, for which fertility information was not collected. However missing observations were balanced between treatment and control groups (p=0.51). In addition, for the main analysis, based on reported age at first pregnancy, we dropped all cases where the first birth or pregnancy occurred prior to program initiation in 2007 so that no individual in the analysis sample had been pregnant or had a birth at baseline. This restriction resulted in dropping 122 girls, approximately 8.1 percent of the treatment group and 5.4 percent of the control group (p=0.06). Since the percentage of girls ever pregnant at baseline was larger in the treatment group, we believe our estimates are biased downward, as this may indicate that treatment girls are at slightly higher risk for pregnancy at baseline. Further robustness checks are presented in section 6c relaxing this assumption.

Our basic model examines the impact of assignment to treatment, T, upon individual i living in household j and cluster k’s likelihood of ever experiencing a pregnancy or being married:

| (1) |

The coefficient of XT in equation (1) establishes our basic program impact on pregnancy or marriage. In this model, HJk represents a vector of household and locational controls. Xtjk represents a vector of individual-level controls; standard errors are clustered at the household level to account for multiple responses within the same household, although results are robust to clustering at the level of randomization (Location). We control for both individual level (age, relationship to head), and household level (age of head, schooling attainment of head, living in Nairobi district) in the analysis. These covariates are selected based on balancing between treatment and control groups presented in Section 6a. All models are probit regressions with marginal effects reported.

We then extend the analysis to explore two potential pathways through which the SCT can affect outcomes: schooling and in-migration. We augment equation (1) with these additional variables to see if they explain variation in the treatment effect on outcomes of interest. We operationalize schooling as 1) current enrollment and 2) grade attainment. We operationalize in-migration by an indicator that the girl moved into the household after the baseline and either before wave 2 or wave 3. Migration is directly related to the time span of protective benefits, where girls who move into treatment households receive associated benefits for shorter amounts of time, in comparison to girls who reside in households for the full study period. We estimate an extension of our main equation, where the individual level mediating indicator, for example, education (Eduijk) is added to the equation. We compare the coefficient of XT with the original equation to assess if the program impact has attenuated when accounting for girl’s education.

| (2) |

All other components of the estimation remain fixed, including additional covariates, treatment of standard errors and estimation samples.

6. Results

6a. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents means for the analytical sample for the key dependent variables and controls by treatment status at baseline. Out of the 1,547 females age 15 to 24 who meet the sample criteria, approximately 15 percent and seven percent had ever been pregnant or married respectively. There are significant differences in pregnancy status (19 percent control versus 13 percent treatment), however none for marriage. The average age and school attainment among girls was approximately 16 and six (or standard 6) years respectively. Approximately 75 percent of the sample was currently enrolled in school and approximately 25 percent of girls had moved into the sample since baseline. The sample was primarily comprised of daughters (43 percent) and granddaughters (36 percent) and approximately 22 percent live in urban areas. Among all the background indicators presented, five show significant differences between treatment and control arms: relationship to head (daughter and granddaughter), head of household’s age and education and indicator for living in Nairobi. Consequently, we controlled for these covariates in our regression analysis to account for the uneven sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for analysis sample of females aged 12 to 24 in 2011, by treatment status

| Outcome variables (2011, N = 1,547) | All | Control | Treatment | P-value of diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever been pregnant | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Ever married or co-habiting | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| Individual-level variables (2011) | ||||

| Age in years | 16.08 | 16.32 | 15.99 | 0.06 |

| Schooling attainment | 6.27 | 6.18 | 6.31 | 0.53 |

| Currently enrolled in school | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.04 |

| Moved into household over panel period | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| Child of household head | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.00 |

| Grandchild of household head | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Child in law or step child of household head | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.73 |

| Niece of household head | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.32 |

| Other relative or non-relative of household head | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| Household head or spouse | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.89 |

| Adopted child or fostered child of household head |

0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| Household-level variables (2007) | ||||

| Female headed household | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.26 |

| Head of household’s age in years | 54.98 | 49.64 | 57.18 | 0.00 |

| Household head’s highest grade attained | 3.81 | 4.40 | 3.56 | 0.01 |

| Urban residence | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.80 |

| Garissa district | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.81 |

| Homa Bay district | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| Kisumu district | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.45 |

| Kwale district | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.43 |

| Migori district | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.52 |

| Nairobi district | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| Suba district | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.81 |

Sample is restricted to adolescent girls who had never had a birth at baseline. P-values are reported from Wald tests on the equality of means of Treatment and Control for each variable. Standard errors are clustered at the household level.

6b. Main impact results

Table 2 presents results from estimates of equation 1 for first pregnancy and Table 3 presents estimates for early marriage. In both tables, column 1 shows the ‘total’ treatment effect without any controls, while subsequent columns introduce controls (column 2), and mediators (columns 3 – 5). Table 2 indicates that young women in treatment households were 5.5 percentage points less likely to have ever been pregnant relative to their counterparts in control households (significant at p<0.05 level). Column 2 adds control variables, but the treatment effect remains significant at 4.9 percentage points at the p<0.05 level. Likewise, the mediating variables in columns 3 – 5 indicate a slight reduction in treatment effect; however, none of the mediators appear to completely account for the treatment effect. Columns 3 and 4 show that schooling attainment and enrollment were protective in predicting first pregnancy, but only school enrollment is statistically significant; girls who moved into the household were at higher risk for early pregnancy. In all models, being the daughter or granddaughter of the household head and living in Nairobi were protective factors, whereas increasing age was a risk factor for early pregnancy. Although other control and mediating factors are similarly correlated with marriage as in early pregnancy, the program treatment indicator is insignificant across all models.

Table 2.

Probit of first pregnancy with mediators among females aged 12 to 24 in 2011

| (1) Unadjusted |

(2) with covariates |

(3) with covariates and schooling attainment |

(4) with covariates and school enrollment |

(5) with covariates and partial treatment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment status | −0.055 (2.52)** |

−0.049 (2.42)** |

−0.049 (2.39)** |

−0.040 (2.15)** |

−0.042 (2.16)** |

| Age in years | 0.035 (12.72)*** |

0.037 (11.79)*** |

0.016 (5.85)*** |

0.033 (12.18)*** |

|

| Child of household head | −0.089 (4.97)*** |

−0.088 (4.91)*** |

−0.048 (2.98)*** |

−0.050 (2.68)*** |

|

| Grandchild of household head |

−0.071 (3.71)*** |

−0.070 (3.63)*** |

−0.018 (0.99) |

−0.052 (2.59)*** |

|

| Head of household’s age in years |

0.001 (1.54) |

0.001 (1.63) |

0.001 (2.34)** |

0.001 (1.25) |

|

| Household head’s highest grade attained |

−0.003 (1.37) |

−0.002 (1.07) |

0.002 (0.87) |

−0.002 (0.98) |

|

| Lives in Nairobi | −0.047 (2.48)** |

−0.044 (2.23)** |

−0.041 (2.53)** |

−0.033 (1.62) |

|

| Grade attainment | −0.003 (1.10) |

||||

| Currently enrolled in school |

−0.315 (9.32)*** |

||||

| Moved into household over panel period |

0.121 (5.49)*** |

||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| N | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 |

Probit models with marginal effects. Robust t-statistics in parentheses clustered at the household level.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

All control variables from 2011 round with the exception of household head characteristics. Sample is restricted to adolescent girls who had never had a birth at baseline.

Table 3.

Probit of marriage or cohabitation with mediators among females aged 12 to 24 in 2011

| (1) Unadjusted |

(2) with covariates |

(3) with covariates and schooling attainment |

(4) with covariates and school enrollment |

(5) with covariates and partial treatment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment status | −0.020 (1.27) |

−0.003 (0.45) |

−0.001 (0.21) |

−0.000 (0.02) |

−0.000 (0.09) |

| Age in years | 0.007 (4.96)*** |

0.007 (4.26)*** |

0.001 (1.71)* |

0.006 (3.76)*** |

|

| Child of household head | −0.075 (5.96)*** |

−0.071 (5.56)*** |

−0.034 (2.61)*** |

−0.044 (4.25)*** |

|

| Grandchild of household head |

−0.045 (4.56)*** |

−0.037 (4.42)*** |

−0.015 (2.50)** |

−0.032 (3.66)*** |

|

| Head of household’s age in years |

0.000 (0.98) |

0.000 (1.42) |

0.000 (1.63) |

0.000 (0.60) |

|

| Household head’s highest grade attained |

−0.002 (2.57)** |

−0.001 (1.73)* |

−0.000 (1.44) |

−0.001 (2.01)** |

|

| Lives in Nairobi | −0.018 (3.59)*** |

−0.013 (3.34)*** |

−0.006 (1.93)* |

−0.012 (2.96)*** |

|

| Grade attainment | −0.004 (3.14)*** |

||||

| Currently enrolled in school | −0.103 (4.12)*** |

||||

| Moved into household over panel period |

0.055 (4.05)*** |

||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| N | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 | 1,547 |

Probit models with marginal effects. Robust t-statistics in parentheses clustered at the household level.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

All control variables from 2011 round with the exception of household head characteristics. Sample is restricted to adolescent girls who had never had a birth at baseline.

To further explore the role of mediators in the pregnancy analysis, we conducted a subsample analysis by enrollment status (columns 1a – 1d) and those moving into the household (columns 2a – 2d) in Table 4. The analysis showed that while the magnitude of the treatment effect is twice as large among those not currently enrolled in school (11.6 percentage points in adjusted model, column 1d, p<0.1), the sample size is small for girls out of school (n=383). This suggests a somewhat complex interaction of the program effect with schooling whereby the SCT actually has a larger protective effect among the most at risk females, those not currently enrolled in school. The estimates comparing adjusted models in columns 2b and 2d suggest a slightly larger treatment effect on young women who moved into the household during the study period, as compared to those who were residents during the full study period (7.8 percentage points versus 3.1 percentage points). However, in neither case are these coefficients significant. While a full analysis of mobility and migration is outside the current scope of the paper (due to data limitations), and sample sizes are quite small and associated standard errors large, this is suggestive of an overall protective environment within treatment households for OVC, which is a major objective of the program.

Table 4.

Probit of ever experiencing pregnancy among females aged 12 to 24 by subsample

| (1a) Enrolled |

(1b) Enrolled |

(1c) Not enrolled |

(1d) Not enrolled |

(2a) Full resident |

(2b) Full resident |

(2c) In movers |

(2d) In movers |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment status | −0.023 (1.60) |

−0.013 (1.19) |

−0.055 (0.92) |

−0.116 (1.88)* |

−0.041 (1.81)* |

−0.031 (1.62) |

−0.064 (1.27) |

−0.078 (1.42) |

| Age in years | 0.008 (5.25)*** |

0.029 (2.86)*** |

0.023 (9.19)*** |

0.074 (8.41)*** |

||||

| Child of household head | 0.023 01.44) |

−0.287 (4.98)*** |

0.004 (0.20) |

−0.218 (5.33)*** |

||||

| Grandchild of household head | 0.022 (1.26) |

−0.071 (0.86) |

−.005 (0.20) |

−0.152 2.84)*** |

||||

| Head of household’s age in years |

0.000 (0.62) |

0.006 (2.52)** |

0.001 (0.85) |

0.001 (0.63) |

||||

| Household head’s highest grade attained |

0.002 (1.71)* |

−0.002 (0.30) |

0.000 (0.24) |

−0.014 (1.97)** |

||||

| Lives in Nairobi | −0.033 (4.70)*** |

0.012 0.14) |

−0.020 (1.10) |

−0.120 (2.43)** |

||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| N | 1,164 | 1,164 | 383 | 383 | 1,168 | 1,168 | 379 | 379 |

Probit models with marginal effects. Robust t-statistics in parentheses clustered at the household level.

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

All control variables from 2011 round with the exception of household head characteristics.

6c. Extensions

We conducted two extensions to further investigate program effects found in the main analysis. First, we re-ran the main models using an alternative pregnancy outcome, log of total fertility rate. The sample size for this analysis was 1,669 and included girls who had been pregnant before the baseline survey, or had multiple births starting before the program period. The mean percentage of girls who had ever been pregnant was approximately 21 percent, up from 15 percent in the main analysis. In addition, nearly half of the girls who have ever been pregnant had more than one birth. Therefore, it is possible that the program may delay subsequent early births, or work to increase birth spacing. These results are found in Supplementary Tables A5. Although treatment effects are consistent and negative across models, coefficients are never significant, indicating that the program works mainly through prevention of first pregnancies. However, we are not able to detect a significant effect on subsequent childbearing or total fertility among this age group. Second, we ran a parallel analysis among men aged 18 to 30 to see if the SCT was increasing the likelihood of marriage for men, and thus inclusion of their wives moving into study households. We present descriptive statistics in Supplementary Table A6 and impacts in Supplementary Table A7. The analysis shows that the program had a negative but insignificant impact on marriage for men in the sample across all models. We tried alternative age ranges for men (15 to 24, 18 to 24 and 18 to 28) and found similar results. This indicates that girls who moved into treatment households were not necessarily doing so because they were moving in to marry men in treatment households, and were, thereby, not at higher risk for pregnancy or marriage outcomes.

7. Discussion and conclusion

This paper provides the first evidence on the impact of a national household-level UCT on early pregnancy and marriage among young women in Africa. Though delayed fertility and early marriage are not explicit objectives of the program, these results indicate that after four years, the Kenyan CT-OVC reduced the probability of being pregnant among young women age 12 to 24 who had never given birth at baseline, by five percentage points or 34% (model 3, adjusted). This magnitude is lower than impacts found for the South African CSG among adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 (10.5 percentage points) using quasi-experimental methods, and on par with decreases found in a pilot RCT in Zomba, Malawi among girls aged 13 to 22 in the UCT arm (6.7 percentage point, or 27%). Within our sample, schooling, measured by either current enrollment or grade attainment, was strongly protective of early pregnancy. The CT-OVC has been shown to have an important impact on secondary school enrollment (The Kenya CT-OVC 2012), thus it is probable that an important pathway through which the CT-OVC affects early pregnancy is by keeping women in school. Schooling has also been identified as playing an important role among a variety of development programming seeking to reduce adolescent childbearing (McQueston et al. 2013). However, our mediation analysis shows that the Kenyan CT-OVC has direct effects on first pregnancy, even after controlling for its impact through schooling. Furthermore, the program impact is smallest among the sample of enrolled girls, indicating that, similar to findings by Baird and colleagues (2011) in Malawi, treatment effects were largest among the group of most disadvantaged girls.

In addition to the education pathway, we identify three other plausible pathways: 1) delay in sexual debut or engagement in risky sex, 2) the income effect associated with increased household financial stability and 3) increases in mental health and aspirations. As previously mentioned, Handa and colleagues (2014) showed that the Kenyan CT-OVC reduced the odds of sexual debut by 31%. Due to the low percentage overlap between the sample utilizing the youth module and our sample from the household questionnaire, we are unable to use sexual debut as a mediating factor in our analysis. However, we can conclude that one of the pathways through which the transfer is likely working is through delay of sexual debut. Although the Kenyan CT-OVC was also found to impact mental health within the same sample of youth, since impacts were driven by males, we lack any supporting evidence for this pathway. In terms of financial security, although we do not have data to directly support the idea that households gave part of the transfer directly to girls, it is plausible that since the transfer was ‘tagged’ as being for the OVC, households acted in a way that was consistent with this prioritization. The analysis examining expenditure impacts shows significant increases were found on food (including four of seven food groups, and substitution away from basic starches), health and clothing, while significant decreases were found on alcohol and tobacco (The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team 2012a). In addition, operational data from 2009 indicates that the primary caregiver of the OVC is the main decision-maker when it comes to spending of the transfer (70%), and that in 21 percent and seven percent of cases, children and OVCs respectively were reported to be the beneficiaries of transfer money, while in the remaining cases, the household as a whole was reported to benefit (Ward et al. 2010). We are aware of only one study in which the transfer was partially given to girls; in the case of the Zomba pilot in Malawi, girls were given a proportion (approximately 1/3) of the transfer, which varied from equivalents of one to five USD per month (Baird et al. 2011). It is unclear if and how a SCT targeted and transferred exclusively to adolescent girls would operate on a larger scale, a design component which was more recently investigated qualitatively in the context of HIV prevention in South Africa (MacPhail et al. 2013).

There are several limitations that warrant discussion. First, all measures are self-reported, including pregnancy, and it is plausible that respondents would tend to underestimate or not report pregnancies among young girls due to social desirability bias. However, our study protocols and instruments are identical to those of the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey upon which national estimates of fertility are based. In addition, because of the wording in the questionnaire, which asks about births, we are unable to capture the timing of miscarriages and abortions, and therefore, it is possible that some of the girls who are included in the analysis and categorized as never having had a birth pre-program, have actually experienced a pregnancy which was terminated early. If this represented a significant portion of the sample, we may be diluting the treatment effect, as the transfer impact is concentrated among impacts on first births. We are unable to implement stronger identification strategies that control for individual unobserved heterogeneity, including difference in difference analysis, because we only have outcome indicators at wave 3. Although we do show suggestively that adolescents who are daughters or granddaughters of the household are less likely to experience early pregnancy and marriage, since we do not collect orphanhood indicators for the full sample, we cannot explore this relationship in more detail. Finally, since a prioritization took place in favor of elderly-headed households in Locations where eligible exceeded budget allocations in treatment areas, and not control areas, the study is not fully experimental, and rather should be interpreted as quasi-experimental.

Although this analysis offers the first evidence of an unconditional national SCT program on first pregnancy and marriage among adolescent girls, and demonstrates significant and positive protective effects on first pregnancy, there is need for further research to confirm impact pathways we propose in our conceptual framework. While there is emerging evidence for many of these pathways to safe transition to adulthood, the magnitudes and pathways will differ based on moderating factors and design of the SCT itself. More sophisticated evaluation designs are also needed. In particular, future research should collect detailed information on adolescents who move in and out of households, including reasons for moving, to ascertain how dynamics around mobility are connected with fertility, marriage and the SCT. Longitudinal data on youth are needed so that designs are not limited to cross-sectional analyses relying on successful randomization at baseline. In addition, more work is needed to understand how SCTs affect boys’ behavior in the same contexts. Finally, there is need for cost effectiveness analyses so that SCTs can be compared to alternative strategies for improved adolescent reproductive health and life trajectories of young women in developing contexts. Despite national law stipulating the minimum age of 18 for marriage, according to the most recent nationally-representative data, approximately 32% of women aged 25 to 49 were married by age 18 in Kenya (KNBS & ICF Macro, 2010). In addition, 14.5% of 15 to 19 year old girls had given birth to at least one child, indicating a need for effective and scalable interventions. The results presented here add to a growing body of evidence showing that poverty-targeted SCTs appear to be a promising strategy to promote safe transitions to adulthood of youth residing in beneficiary households.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examine cash transfer impacts on pregnancy and marriage of females aged 12 – 24.

Transfers decrease first pregnancy by 5 percentage points (34%).

There are no measurable impacts on early marriage.

Education, financial security and delays in sexual debut likely mediating factors.

National unconditional cash transfers can facilitate safe transitions for youth.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Technical Working Group of the Children’s Department, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Development, Government of Kenya, and to Daniel Musembi in particular, for support to the follow-up study of the Cash Transfer-Orphans and Vulnerable Children. Participants at the Population Association of America annual conference 2013, the Association of Public Policy and Management annual conference 2013 and the 8th Annual Poppov Conference on Population, Reproductive Health and Economic Development for helpful comments; and to Audrey Pereira for editorial assistance. This study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethics Review Committee (Protocol #265) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina. The research was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health through Grant Number 1R01MH093241 and by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development R24 HD050924 to the Carolina Population Center. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sudhanshu Handa, Professor and Chair, Department of Public Policy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Chief, Social and Economic Policy Unit, UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti, Florence Italy.

Amber Peterman, Social Policy Specialist, UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti, Piazza SS. Annunziata 12, 50122 Florence, Italy, apeterman@unicef.org, Tel: +39 055 2033193, Fax: +39 055 2033220

Carolyn Huang, Doctoral student, Department of Public Policy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Carolyn Halpern, Professor, Department of Materal and Child Health, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health

Audrey Pettifor, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health

Harsha Thirumurthy, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health

References

- Alam A, Baez JE, Del Carpio XV. Does cash for school influence young women’s behavior in the longer term? Washington D.C.: World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. The Economics of Dowry and Brideprice. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2007;21(4):151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Baird S, McIntosh C, Ozler B. Cash or condition? Evidence from a cash transfer experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2011;126:1709–1753. [Google Scholar]

- Baird S, de Hoop J, Ozler B. Income Shocks and Adolescent Mental Health. Journal of Human Resources. 2013;48(2):370–403. [Google Scholar]

- Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. The Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1220–1231. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman J. Does Schooling Affect Women’s Desired Fertility? Evidence from Malawi, Uganda and Ethiopia. Demography, forthcoming. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Hosegood V, Lund F. The reach and impact of child support grants: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal. Development Southern Africa. 2005;22(4):467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. Early Marriage and HIV Risks in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;35(3):149–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Boyes M, Orkin M, Pantelic M, Molwena T, Sherr L. Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa: a propensity-score-matched case-control study. The Lancet Global Health. 2013;1:362–70. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B, Bledsoe CH, editors. Social dynamics of adolescent fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. National Academies Press; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn JR, Caraël M, Auvert B, Kahindo M, Chege J, Musonda R, Buvé A. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS. 2001;15:S51–S60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulematova-Swan M. Evaluating the Impact of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs on Adolescent Decisions about Marriage and Fertility: The Case of Oportunidades (Doctoral dissertation) 2009. Retrieved from: http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3363363 (AAI3363363). [Google Scholar]

- Handa S, Halpern CT, Pettifor A, Thirumurthy H. The Government of Kenya’s Cash Transfer Program Reduces the Risk of Sexual Debut Among Young People Age 15 −25. PLoS ONE. 2014a;9(1):85473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa S, Seidenfeld D, Davis B, Tembo G and the Zambia Cash Transfer Evaluation Team. Innocenti Working Paper No. 2014-08. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research; 2014b. Are Cash Transfers a Silver Bullet? Evidence from the Zambian Child Grant. [Google Scholar]

- Handa S, Huang C, Hypher N, Teixeira C, Soares FV, Davis B. Targeting effectiveness of social cash transfer programmes in three African countries. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 2012;4(1):78–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Cho H, Rusakaniko S, Iritani B, Mapfumo J, Halpern C. Supporting adolescent orphan girls to stay in school as HIV risk prevention: evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1082. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman K. Gendered socioeconomic conditions and HIV risk behaviours among young people in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2005;4(1):37–50. doi: 10.2989/16085900509490340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DT, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa’s high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. The Lancet. 2004;364(9428):4–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haushofer J, Shapiro J. Welfare Effects of Unconditional Cash Transfers: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Kenya. Working paper. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C, Hoddinott J, Samson M. Reducing Adolescent Risky Behaviors in a High-Risk Context: The Effects of Unconditional Cash Transfers in South Africa. Working paper. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Kurz K. New Insights on Preventing Child Marriage: A Global Analysis of Factors and Programs. Washington, D.C.: International Center for Research on Women; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52(5):733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, Lutalo T, Wawer MJ. Age differences in sexual partners and risk of HIV-1 infection in rural Uganda. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;32(4):446–451. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn K, Thirumurthy H, Halpern C, Pettifor A, Handa S. Effects of a large-scale unconditional cash transfer program on mental health outcomes of young people in Kenya: a cluster randomized trial; Working paper; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R, Vanderhoeft C, Becker S, Kibet M. Individual and contextual effects of education on proximate fertility determinants and on life-time fertility in Kenya. 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Luke N. Age and Economic Asymmetries in the Sexual Relationship of Adolescent Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;34(2):67–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail C, Adato M, Kahn K, Selin A, Twine R, Khoza S, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of Cash Transfers for HIV Prevention among Adolescent South African Women. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2301–2312. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0433-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maganja RK, Maman S, Groves A, Mbwambo JK. Skinning the goat and pulling the load: transactional sex among youth in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):974–981. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TC. Women’s education and fertility: results from 26 Demographic and Health Surveys. Studies in family planning. 1995:187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S. Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7449):1152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1152-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwasiaji W. Scaling up Cash Transfer Programmes in Kenya. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, One pager No. 286. IPC-IG, Brasilia, Brazil. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- McQueston K, Silverman R, Glassman A. The Efficacy of Interventions to Reduce Adolescent Childbearing in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Studies in Family Planning. 2013;44(4):369–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch BS, Lloyd CB. Gender differences in the schooling experiences of adolescents in low-income countries: The case of Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 1998:167–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Tsoka M, Reichert K. Impact evaluation report: External evaluation of the Mchinji social cash transfer pilot. Draft. Boston, MA: Center for International Health and Development, Boston University; Lilongwe: Center for Social Research, University of Malawi; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oleke C, Blystad A, Moland KM, Rekdal OB, Heggenhougen K. The Varying Vulnerability of African Orphans The case of the Langi, northern Uganda. Childhood. 2006;13(2):267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T, Peterman A. Are Female Orphans at Risk for Early Marriage, Early Sexual Debut, and Teen Pregnancy? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(2):101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Yeh E. Transactional Sex as a Response to Risk in Western Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2011;3(1):35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L, Mushati P, Eaton JW, Dumba L, Mavise G, Makoni J, Gregson S. Effects of unconditional and conditional cash transfers on child health and development in Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet. 2013;381(9874):1283–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyukta M, Greene M, Malhotra A. Too Young to Wed: The Lives, Rights, and Health of Young Married Girls. Washington D.C.: ICRW; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stecklov G, Winters P, Todd J, Regalia F. Demographic externalities from poverty programs in developing countries: Experimental evidence from Latin America. Washington, D.C.: Department of Economics, American University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J, Thomas D. Human Resources: Empirical Modeling of Household and Family decisions. In: Behrman J, Srinivasan TN, editors. Handbook of Development Economics, 3A. North-Holland: Amsterdam; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team. The impact of the Kenya Cash Transfer Program for Orphans and Vulnerable Children on household spending. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 2012a;4(1):9–37. [Google Scholar]

- The Kenya CT-OVC Evaluation Team. The impact of Kenya’s Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children on human capital. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 2012b;4(1):38–49. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, EPRI, University of Oxford, UNDP, USAID et al. Social Protection Programs Contribute to HIV Prevention. Policy Brief. 2015 Retrieved from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/transfer/publications/briefs/SocialProtectionHIVBrief_Jan2015.pdf.

- UNICEF. Child Marriage: Progress. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.childinfo.org/marriage_progress.html.

- Walker JA. Early Marriage in Africa - Trends, Harmful Effects and Intervention. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2012;16(2):231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P, Hurrell A, Visram A, Riemenschneider N, Pellerano L, O’Brien C, et al. Operational and Impact Evaluation, 2007–2009. Oxford, UK: Oxford Policy Management; 2010. Cash Transfer Programme for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (CT-OVC), Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Adolescent Pregnancy: Fact Sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014a. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014b. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Kenya – Cash Transfer Programme for Orphan’s and Vulnerable Children: Midterm review. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group; 2012. Retrieved from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2012/04/24011873/kenya-cash-transfer-programme-orphans-vulnerable-children-mid-term-review. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.