Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of mood-stabilizing medications for depression and suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder.

Method

The Treatment of Early Age Mania (TEAM) study is a multicenter, prospective, randomized and masked comparison of divalproex sodium (VAL), lithium carbonate (LI), and risperidone (RISP) in an 8-week parallel clinical trial. 279 children with DSM-IV diagnoses of bipolar I disorder, mixed or manic, aged 6-15 years were enrolled. The primary outcome measure was improvement on the Clinical Global Impression scale for depression (CGI-BP-I-D). Secondary outcome measures included the Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS-R) and suicidality status. Statistics included longitudinal analysis of outcomes using generalized linear mixed models with random intercept both for the complete data set and by using last observation carried forward.

Results

CGI-BP-I-D ratings were better in the RISP group (60.7%) as compared to the LI (42.2%; p = .03) or VAL (35.0%; p=.003) groups from baseline to the end of the study. CDRS scores in all treatment groups improved equally by study end. In week 1, scores were lower with RISP compared to VAL (mean = 4.72, 95%CI: 2.67-6.78), and compared to LI (mean = 3.63, 95%CI: 1.51-5.74), though group differences were not present by the end of the study. Suicidality was infrequent, and there was no overall effect of treatment on suicidality ratings.

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms, present in the acutely manic or mixed phase of pediatric bipolar disorder, improved with all three medications, though RISP appeared to yield more rapid improvement than LI or VAL and was superior using a global categorical outcome.

Keywords: bipolar, depression, pediatrics, treatment, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Several studies in recent years have highlighted treatment strategies for pediatric bipolar disorder (BD), particularly for manic symptoms during the acute manic phase of the illness1, 2. However, there is little data regarding the effect of treatment on depressive symptoms that occur in the context of acute manic or mixed episodes. Mood lability and impulsivity are constituent symptoms in BD and present substantial risk in the context of suicidal ideation. The presence of mixed mood states and rapid cycling BD are common in pediatric BD, so that depressive symptoms often co-occur with manic symptoms in this age group3-5. Mixed mood states are associated with increased risk of suicide attempts in youth with BD, so management of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in the context of manic symptoms have clear clinical significance6.

Current treatment strategies have emphasized the use of traditional mood stabilizers (anticonvulsants and lithium carbonate) and second generation antipsychotics for acute mania or mixed states7. Yet it is less clear how these treatments affect depressive symptoms that may also be present. A growing perspective in the adult literature is that antidepressants may be suboptimal for treatment of bipolar depression8-11. Some anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have demonstrated efficacy in treating bipolar depression in adults12. However, there is no clear consensus for how to optimally manage depression and suicidality that occur in the context of manic symptoms in children and adolescents with BD13-15.

The recently completed TEAM (Treatment of Early Age Mania) study evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of three common pharmacologic treatments for BD. Representative examples of three classes of medicines, lithium (traditional mood stabilizer), divalproex sodium (anticonvulsant mood stabilizer), and risperidone (second generation antipsychotic) were tested in a multisite, masked, randomized clinical trial in children and adolescents aged 6-15. The primary and secondary outcome variables included CGI-BP (Clinical Global Impression-Bipolar) and KMRS (Kiddie Mania Rating Scale) scores, respectively. Risperidone was found to be more efficacious than lithium carbonate or divalproex sodium for treatment of manic symptoms, though not necessarily in terms of tolerability16.

The TEAM study systematically collected data on a weekly basis not only about manic symptoms—the primary aim of the study—but also about a variety of other symptom categories, including depressive symptoms and suicidality. Given the clinical urgency of suicidality and prominence of depressive symptoms in manic and mixed mood state exacerbations of pediatric BD, our aim was to review the TEAM data set and assess the effectiveness of anti-manic medications specifically in terms of effect on depression and suicidality that were present during acute manic or mixed episodes.

METHOD

The TEAM multicenter study involved a prospective, randomized comparison of three treatments, divalproex sodium (VAL), lithium carbonate (LI), and risperidone (RISP) in an 8-week parallel clinical trial. A detailed description of the TEAM study procedures has been previously published16. This secondary analysis focuses on the prospectively determined outcome of these pharmacological treatments on depressive symptoms as well as suicidality through the course of this clinical trial.

Medication titration goals included serum levels for lithium (1.1-1.3 mEq/L), and divalproex sodium (111-125 ug/mL) and total daily dosage of risperidone (4-6 mg). Medications were titrated so long as dose-limiting adverse events were not present. Participants with weight gain over 15% of baseline were discontinued. Details regarding medication titration schedules are described elsewhere16.

Participants

Two hundred and seventy-nine child and adolescent outpatients aged 6-15 years of age who were included in the final analysis were recruited from five study sites (one site closed early in the study and was combined with another site nearby) across the United States. Participants were included if they had a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode (based on the Washington University Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [WASHU-K-SADS]) and a Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) score of less than 60. Comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) were included to reflect comorbidities commonly seen in clinical practice. To this end, patients with depressive symptoms were included as well as those with suicidal ideation, as long as there was no imminent risk during the study period. The participants were particularly remarkable in that many had significant psychotic symptoms and acuity that reflected lengthy durations of illness; however, as noted in previous publications on this sample, participants were included to allow appropriate applicability to commonly encountered clinical situations. Exclusionary factors included a lifetime history of schizophrenia, pervasive developmental disorder, IQ under 70, a major medical or neurological illness, or substance abuse or dependence in the previous 4 weeks. Stimulant medications on a stable dose for the prior 3 months were permitted; however, other psychotropic drugs including antidepressants were excluded. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site and was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Outcome Variables

Detailed psychiatric assessments were done at baseline and at week 8, the conclusion of the study. Interim visits occurred weekly and included monitoring treatment effects and real time tracking of manic and depressive symptoms. For this analysis, CGI-BP Improvement in Depression (CGI-BP-I-D) rating was the primary outcome variable, similar to the primary outcome variable for the main study. Secondary outcome variables included score change in the Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) and suicidality status. The suicidality status was separately analyzed by using the suicidal ideation question (Item 13) from the CDRS. Scores of 1 and 2 were considered negative for suicidality, while scores of 3 (thoughts about suicide or self-harm) through 7 (suicide attempt) were considered positive.

All participants were evaluated with the WASH-U-K-SADS, a semi-structured, clinician-administered diagnostic instrument, administered at baseline and again at week 8 with an independent rater blinded to both treatment assignment and week 1-7 ratings. CGI-BP Depression Severity ratings (CGI-BP-S-D) were assessed at baseline, and Improvement ratings (CGI-BP-I-D) were obtained at week 8 for purposes of group comparisons. CGI-BP-I-D ratings of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) were considered positive treatment responses, and ratings of 3-7 were considered non-responders. The CDRS was administered both at baseline and weekly over the 8 weeks of the study. The baseline CDRS rating reflects symptoms during the current mood episode, while the weekly CDRS ratings represent symptoms in the prior week. In order to examine temporal changes in symptoms on a weekly basis, weeks 1-7 CDRS and suicidality ratings were included in the data set for analysis. Week 8 ratings were included but analyzed as compared to baseline ratings as both the baseline and week 8 ratings were performed by blinded raters. Additionally, the scope of week 8 assessments included the entirety of the study rather than the interim week to week periods. By including analyses of the week 1-7 ratings, we were able to avail ourselves of real-time changes that were recorded during the study. In that manner, details that related to suicidality and depression could be assessed in addition to the overall response through the entire study.

Statistical Analysis

CGI-BP-I-D ratings were assessed at the end of the study, week 8. Analogous to Geller et al16, study participants who discontinued treatment before week 8 assessment were considered non-responders15. In addition to the primary CGI analyses where dropouts were coded as non-response, last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was used to determine CGI response status. CGI-BP-I-D ratings were also assessed for completers (participants with no missing data) of the trial and presented for comparison purposes. CGI-BP-S-D ratings at baseline were compared across treatment groups using a Kruskal-Wallis test. Chi-square test of association was used to assess differences in proportions of improvement on CGI-BP-I-D at week 8 across treatment arms. Multiple logistic regression models were used to compare CGI-BP-I-D response at week 8 across medication groups after adjusting for demographic and clinical history characteristics including age, race, clinical site, KMRS, and CDRS baseline scores. Logistic regressions were similarly performed three ways: coding dropouts as non-response, LOCF, and restricted to completers only.

CDRS scores at baseline and at week 8 were compared across treatment groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bartlett's test for equal within-group variances. Generalized linear mixed effects regression models were fit to describe within-patient changes in suicidality status and CDRS scores over time by treatment arm. The models included a random intercept to account for within-participant correlation of outcomes over time. Fixed effects included medication group (represented as two indicator variables), follow-up time, and their interaction. The models estimated the following measures of association 1) patient-specific odds ratio (OR) of suicidality and 2) change in mean within-patient depression score. These patient-specific estimates were adjusted for baseline age, race, KMRS score at each week, and CDRS or suicidality status at baseline to account for the possibility that the baseline rater was different from raters in weeks 1-7. CDRS models also adjusted for clinical site as a fixed effect as well as first-order autoregressive residual variance-covariance structure for within-person responses. Due to low frequency of the outcome, the suicidality models did not adjust for site.

Missing data on CDRS scores and suicidality status due to treatment discontinuation and drop-out were handled in multiple ways. Analyses were done by comparing characteristics for individuals with and without missing data. In the primary analysis for CDRS scores, all available data for each patient up to the visit when they dropped out from the study were included. By using the generalized linear mixed models, we assumed that the probability of missing data depends on treatment arm and follow-up time, as well as other measured covariates included in the model. In the second level of analysis, data from dropouts were imputed using the LOCF method. For comparison purposes, the analysis was repeated for completers only. CDRS scores were calculated with and without item 13 to allow for the possibility that suicidality may confound overall CDRS scores. Subgroup analyses were also done for participants with baseline CDRS scores of 45 or greater to account for potential confounds related to depression status at baseline.

Missing data due to discontinuation as applied to suicidality status were handled in multiple ways as well. In addition to using all available data, LOCF and completers only, analyses were also done by coding missing data as best case (dropouts coded as non-suicidal), worst case (dropouts coded as suicidal), and applying attribution ratings for dropouts. Attributions included coding as best case or worst case depending upon the reason for dropout, e.g. moving or relocation coded as best case, hospitalization coded as worst case.

RESULTS

Discontinuation

Of the 279 enrolled participants, 69 (24.7%) discontinued the treatment during the first 8 weeks of the study. Among the dropouts, suicidal status could not be uniformly established in weekly follow-up ratings, but other reasons for discontinuation in the original sample are described in Table 1 (adapted from Geller et al. 2012—supplemental material: eTable 1)16. Reasons for discontinuation included: changed their mind (n = 37), side effects (n = 15), worsening of symptoms (n = 7), psychiatric hospitalization (n = 4, of which one patient was hospitalized due to increased suicidal ideation) and geographical relocation, onset of severe medical illness, weight/body mass index (BMI) increase (all n = 1), and other (n = 3). Of 37 participants who “changed their mind,” 25 did not state a specific reason. The remaining 12 gave the following reasons: participant did not improve (n = 8), parents disagreed (n = 1), community psychiatrist objected (n = 1), weight gain (n = 1), and patient began lactating (n = 1)16. Depressive symptoms were not prominent among identified reasons for discontinuation. Assignment to the RISP group was associated with lower likelihood for dropout as compared to LI (OR 0.39; p=0.011), but not as compared to VAL (OR 0.53; p=0.09)16. LI and VAL did not differ in terms of dropouts (OR 1.35; p=0.35)16.

Table 1.

Discontinuation Rates by Reason and Medicationa

| Total (24.7%; 69/279) | Risperidone (15.7%; 14/89) | Lithium (32.2%; 29/90) | Divalproex Sodium (26.0%; 26/100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons for Discontinuation, n (%) | ||||

| Changed Mind | 37/69 (53.6) | 8/14 (57.8) | 15/29 (51.7) | 14/26 (53.8) |

| Side effects | 15/69 (21.7) | 3/14 (21.4) | 8/29 (27.6) | 4/26 (15.4) |

| Worsening of Symptoms | 7/69 (10.1) | 0/14 (0) | 4/29 (13.8) | 3/26 (11.5) |

| Psychiatric Hospitalization | 4/69 (5.8) | 1/14 (7.1) | 1/29 (3.4) | 2/26 (7.7) |

| Geographical relocation | 1/69 (1.4) | 0/14 (0) | 0/29 (0) | 1/26 (3.8) |

| Onset of severe medical illness | 1/69 (1.4) | 0/14 (0) | 0/29 (0) | 1/26 (3.8) |

| Weight/BMI increase | 1/69 (1.4) | 1/14 (7.1) | 0/29 (0) | 0/26 (0) |

| Other | 3/69 (4.3) | 1/14 (7.1) | 1/29 (3.4) | 1/26 (3.8) |

Note: BMI = body mass index

Adapted from Geller et al.16, eTable 1.

Completers vs. Dropouts

Comparison of completers and dropouts did not reveal any significant differences between the groups with respect to age, depression, and mania severity at baseline. Lifetime suicidality risk at baseline was slightly higher for those who discontinued treatment (49% vs. 44%); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p value = 0.5).

CGI-BP Depression Ratings

Median scores for baseline CGI-BP-S-D severity were 4 for each treatment group; this rating corresponds to “moderately ill” status. The middle 50 percent (i.e., the difference between 25th and 75th percentiles) of CGI-BP-S-D scores in the VAL group had slightly worse baseline scores compared to RISP and LI (4-5 versus 3-5), but this difference did not reach significance when groups were compared (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value=0.245). Week 8 ratings showed a distinct improvement in CGI-BP-I-D ratings in the RISP group compared to the VAL and LI groups. These group differences persisted whether missing data was coded as non-response or by using LOCF. A higher proportion of improvement in the RISP group was also found when analysis was restricted to study completers (Table 2A).

Table 2A.

Clinical Global Impression-Bipolar (CGI-BP) Depression Improvement From Baseline to Week 8

| Dropouts Coded as No Improvement | Last Observation Carried Forward | Completers only, n=216 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | n | Percent with improvement (CGI ≤ 2) | n | Percent with improvement (CGI ≤ 2) | n | Percent with improvement (CGI < 2) |

| LI | 90 | 42.2 | 85 | 47.1 | 62 | 61.3 |

| RISP | 89 | 60.7* | 89 | 67.4** | 78 | 69.2*** |

| VAL | 100 | 35.0 | 97 | 44.3 | 76 | 46.1 |

Note: LI = lithium carbonate; RISP = risperidone; VAL = divalproex sodium.

p-value for chi square test = 0.001

p-value for chi square test = 0.003

p-value for chi square test = 0.013

Logistic regression models for CGI improvement at week 8 were done three ways: coding dropouts as non-response, as LOCF, or restricting analysis to completers only (Table 2B). Comparing CGI-BP-I-D ratings at week 8 showed superior performance for RISP compared to VAL or LI while controlling for race, age, KMRS, baseline CDRS score, and clinical site (first model, dropouts coded as no improvement: estimated OR of improvement = 2.13, 95%CI 1.09, 4.18, p-value = 0.027 for RISP vs. LI and estimated OR of improvement = 2.58, 95%CI 1.32, 5.05, p-value = 0.006 for RISP vs. VAL). Of note, in this logistic regression model, the LOCF analysis showed that improvement in CGI scores was associated with better concurrent KMRS scores, but this was not found in the primary CGI analyses. Similarly, analysis restricted to completers only found that CGI improvement was also associated with improvement in KMRS scores; however, the improvement was not associated with treatment group as it was in the other two analyses.

Table 2B.

Logistic Regression Model of Clinical Global Impression-Bipolar (CGI-BP) Depression Improvement

| Dropouts coded as no improvement | Last observation carried forward | Completers only, n=216 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI for OR | p value | OR | 95%CI for OR | p value | OR | 95%CI for OR | p value | |

| RISP vs. LI | 2.13 | 1.09, 4.18 | 0.027 | 2.03 | 1.01, 4.08 | 0.046 | 0.80 | 0.34, 1.85 | 0.596 |

| VAL vs. LI | 0.83 | 0.43, 1.58 | 0.565 | 1.08 | 0.56, 2.09 | 0.820 | 0.59 | 0.26, 1.34 | 0.209 |

| RISP vs. VAL | 2.58 | 1.32, 5.05 | 0.006 | 1.88 | 0.95, 3.74 | 0.070 | 1.34 | 0.59, 3.02 | 0.482 |

| white vs. other | 0.72 | 0.26, 2.01 | 0.534 | 0.81 | 0.29, 2.28 | 0.695 | 0.74 | 0.22, 2.54 | 0.634 |

| black vs. other | 0.37 | 0.12, 1.16 | 0.089 | 0.56 | 0.18, 1.8 | 0.334 | 1.11 | 0.27, 4.57 | 0.886 |

| age at baseline (per year) | 1.04 | 0.94, 1.15 | 0.429 | 1.05 | 0.94, 1.16 | 0.389 | 1.11 | 0.98, 1.26 | 0.101 |

| KMRS score | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.03 | 0.649 | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.98 | 0.001 | 0.87 | 0.82, 0.92 | <0.0001 |

| CDRS at baseline | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.225 | 1.03 | 1.00, 1.06 | 0.097 | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.06 | 0.180 |

| Clinical Site (Children's National Med Center as reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Johns Hopkins Medical Inst. | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.35 | <0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.38 | <0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.06, 0.51 | 0.002 |

| University of Pittsburgh. | 1.01 | 0.4, 2.51 | 0.990 | 0.83 | 0.31, 2.21 | 0.705 | 0.76 | 0.24, 2.37 | 0.637 |

| University of Texas | 0.13 | 0.05, 0.31 | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 0.06, 0.42 | <0.0001 | 0.34 | 0.11, 1.08 | 0.067 |

| Washington University | 0.18 | 0.07, 0.42 | <0.0001 | 0.13 | 0.05, 0.33 | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 0.05, 0.47 | 0.001 |

Note: Boldface type represents statistically significant data. CDRS = Children's Depression Rating Scale; KMRS = Kiddie Mania Rating Scale; LI = lithium carbonate; RISP = risperidone; VAL = divalproex sodium.

Odds of CGI-BP-I-D improvement were lower at Johns Hopkins Medical Institute (JHMI), University of Texas, and Washington University compared to Children's National after adjustment for study medication, patient's age, race, baseline CDRS, and KMRS. The estimated adjusted odds of CGI Improvement is 0.15, 95%CI: 0.06 to 0.35, p-value<0.0001 for JHMI vs. Children's National, 0.13, 95%CI: 0.05 to 0.31, p-value<0.0001 for University of Texas vs. Children's National, and 0.18, 95%CI: 0.07 to 0.31, p-value <0.0001 for Washington University vs. Children's National. There was no statistical difference in odds of CGI-BP-I-D improvement between University of Pittsburgh and Children's National Medical Center after adjustment for study medication, patient's age, race, baseline CDRS, and KMRS.

CDRS Depression Ratings

From the original study results16, CDRS scores show similarities between treatment arms at baseline and also similar levels of clinical improvement by study end. Mean CDRS scores did not differ between groups at baseline (LI: n=90, mean = 46.76, SD 10.31; RISP: n=89, mean = 48.34, SD 10.73; VAL: n=100, mean = 48.77, SD 9.99; one-way ANOVA p-value=0.378). When a minimum baseline score of 45 or greater was used as a cutoff, the sample was smaller but similar in terms of CDRS scores (LI: n=50, mean=54.06, SD=7.13; RISP: n=52, mean=55.48, SD=7.91; VAL: n=63, mean=54.86, SD=6.58; one-way ANOVA p-value=0.608). Thus, no treatment group had worse depression at baseline. Each treatment was compared head-to-head, and endpoint CDRS scores did not differ between treatments using an LOCF analysis (one-way ANOVA p-value = 0.600).

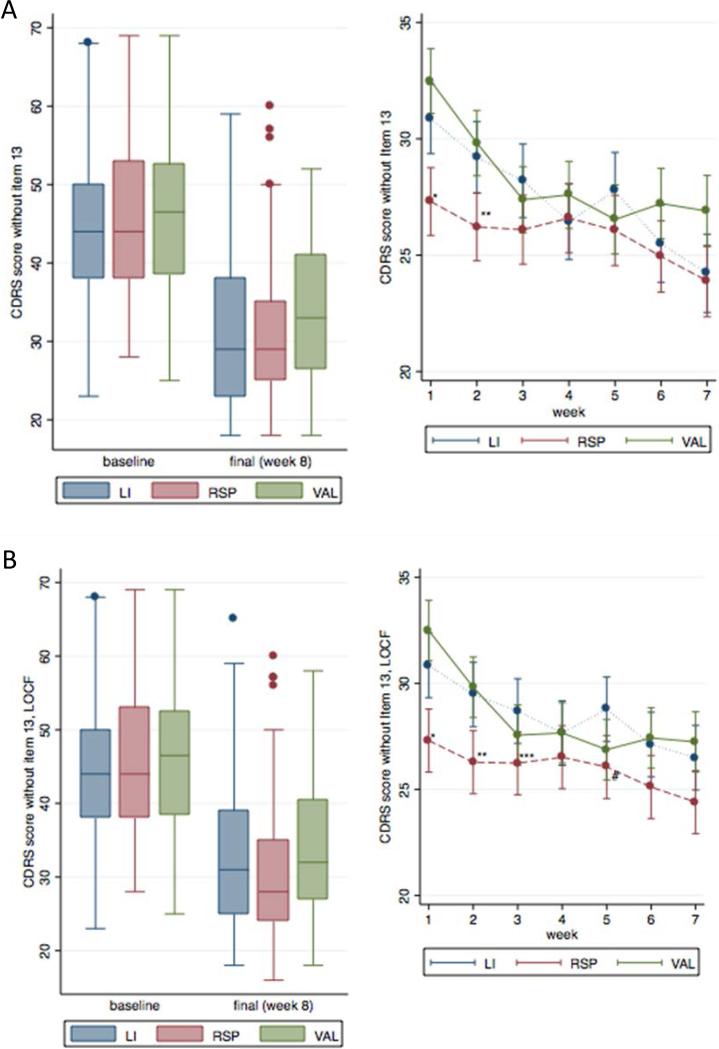

In contrast, analysis of the weekly CDRS scores showed a pattern of early improvement in the RISP group compared to the VAL and LI groups. Figures 1A and 1B show CDRS scores (excluding item 13) for three treatment groups at baseline compared to week 8 as well as within-patient changes in CDRS scores between weeks 1 and 7. Assessment of individual data points shows that very few outliers exist, and de novo depression appears to be at a minimum. All treatments led to improvement, but a closer look at the weekly ratings shows that the RISP group had significantly lower scores at weeks 1 and 2 when all available data were included, and at weeks 1-3 and week 5 for LOCF analysis.

Figure 1.

A) Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) scores—analysis with all available data included. Note: χ2 test statistic (df = 14) for the overall statistical effect of medication = 48.2, p < .0001. LI = lithium carbonate; RISP = risperidone; VAL = divalproex sodium. *VAL vs. RSP, p < .0001 and for LI vs. RSP, p = .001; **VAL vs. RSP and for LI vs. RSP, p = .001. B) CDRS scores—analysis with last observation carried forward (LOCF). Note: χ2 test statistic (df = 14) for the overall statistical effect of medication = 47.3, p value < .0001. *p value for VAL vs. RSP <.0001 and for Li vs. RSP = .001; **p value for VAL vs. RSP = .002 and for Li vs. RSP = .001; ***p value for Li vs. RSP = .024; #p value for Li vs. RSP = .029.

A similar result was found when restricting the sample to those who completed the trial. At week 5, VAL appeared to be superior to LI in two models, all data included (estimated difference in CDRS scores = 2.64 for LI vs. VAL, 95% CI: 0.43-4.86; p=0.019) and LOCF (estimated difference in CDRS scores = 2.64 for LI vs. VAL = 3.06, 95% CI: 0.96-5.15; p=0.004). No statistically significant differences in CDRS scores were present between LI and VAL at any of the other weekly visits. Also at week 5, RISP appeared to be superior to LI in the LOCF model (estimated difference in CDRS scores for LI vs. RISP = 2.40, 95% CI: 0.25-4.56; p=0.029). However, none of the week 5 findings were present in the model of completers only. CDRS scores were calculated excluding item 13, which involves suicidality; however, overall and weekly group differences were similar whether or not item 13 was included or not. Results of CDRS scores analyses when item 13 is included are shown in Figure S1, available online. All treatments showed a decrease in CDRS scores over time with a plateau that appeared to occur by week 6; at that point, group differences no longer existed. Details of weekly CDRS ratings and analyses are included in Table S1 (available online).

A subgroup analysis was done for participants with baseline CDRS scores of 45 or greater. The treatment groups were similar at baseline and did not differ by study end, whether by looking at all available data or LOCF. However, a closer look at weekly ratings suggested a similar pattern, as found in the overall sample. Early improvement was identified in weeks 1 and 2 in the RISP group as compared to LI and VAL. The differences did not persist after the first two weeks, but a difference between VAL and LI was found in week 5 as was found in the overall sample. Details of the subgroup analysis are found in Table 3. The weekly ratings were also calculated excluding item 13, but results were similar when 13 was included in overall CDRS scores for weekly visits. These data is available in Table S2, available online.

Table 3.

Results of Subgroup Analysis for Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) Scores of 45+ at Baseline

| LI vs. VAL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Point Estimate | 95%CI | p-value |

| 1 | −0.36 | −3.25, 2.52 | .804 |

| 2 | −0.53 | −3.5, 2.43 | .724 |

| 3 | 1.98 | −1.06, 5.01 | .202 |

| 4 | 1.01 | −2.09, 4.12 | .522 |

| 5 | 3.36 | 0.21, 6.52 | .036 |

| 6 | −0.90 | −4.08, 2.29 | .582 |

| 7 | −3.40 | −6.58, −0.21 | .037 |

| VAL vs. RISP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Point Estimate | 95%CI | p-value |

| 1 | 5.33 | 2.49, 8.17 | <.001 |

| 2 | 3.62 | 0.77, 6.48 | .013 |

| 3 | −0.84 | −3.74, 2.06 | .570 |

| 4 | −0.34 | −3.26, 2.58 | .820 |

| 5 | −1.72 | −4.7, 1.25 | .256 |

| 6 | 1.52 | −1.49, 4.53 | .322 |

| 7 | 2.19 | −0.83, 5.2 | .156 |

| LI vs. RISP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Point Estimate | 95%CI | p-value |

| 1 | 4.97 | 1.95, 7.98 | .001 |

| 2 | 3.09 | 0.01, 6.17 | .049 |

| 3 | 1.13 | −2.01, 4.28 | .480 |

| 4 | 0.67 | −2.54, 3.88 | .681 |

| 5 | 1.64 | −1.6, 4.88 | .320 |

| 6 | 0.63 | −2.65, 3.9 | .708 |

| 7 | −1.21 | −4.47, 2.05 | .466 |

Note: Boldface type represents statistically significant data. Results of generalized linear mixed models looking at differences in scores between treatment arms at each weekly visit adjusted for site, age, race, Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (KMRS), baseline CDRS scores, and clinical site (models include all available data, exclude item 13). Chi-square test statistic (df = 14) for the overall statistical effect of medication on CDRS = 45.1, p-value <.0001. LI = lithium carbonate; RISP = risperidone; VAL = divalproex sodium.

In the model that assumes a linear CDRS trajectory over time between baseline and week 7, there was a gradual decrease in CDRS scores over time in LI and VAL, but no such linear response in RSP (p-value for differences in slopes: RSP vs. LI = 0.079, RSP vs. VAL = 0.024, and LI vs VAL = 0.679). However, in the time period between baseline and week 1, a statistically significant decline in CDRS scores was most pronounced in the RSP group: 10.8 (95%CI: between 9.2 and 12.4 points) compared to 7.6 (95%CI between 5.99 and 9.11) for LI and 8.6 (95%CI: between 7.15 and 10.09) for VAL. There was no additional statistically significant decline in CDRS scores in RSP group between weeks 1 and 7, while in LI and VAL groups, the CDRS scores continued to gradually decline until week 7. These data are described in Table S3, available online.

Suicidality Ratings

Suicidality, item 13 on the CDRS, was separately assessed and found to improve equally among the treatment groups from baseline to study end. Suicidality was uncommon at all weekly ratings. There was no statistically significant overall effect of treatment in any of the analyses. However, group comparisons were more variable depending upon the level of analysis for dropouts, e.g. best case, worst case, etc. Suicidality was an uncommon occurrence, and, except as noted, did not differ in terms of group comparisons. Additional levels of analytic modeling are shown in Figure S2, available online.

DISCUSSION

This analysis aimed to elucidate treatment outcomes regarding depression and suicidality in the TEAM study of acute mania and mixed states in youth. Suicidality and depression were prominent in the sample at intake and improved significantly in all three medication groups by study end. The results varied by the outcome measure used. When analyzing global depression severity ratings (CGI-BP-I-D) at study endpoint, RISP had significantly higher response rates than either VAL or LI; VAL and LI did not differ. However, when looking at a dimensional depression severity scale (CDRS), the three medication groups did not differ in degree of change from baseline to endpoint. Risperidone emerged as yielding the most rapid clinical improvement in CDRS scores. RISP was associated with more rapid improvement, lowest proportion of discontinuation (15.7% vs. 32.2% for LI and 26% for VAL), and is associated with lower depression ratings in the first three weeks of treatment as revealed by two methods of data analysis.

Dropouts might confound the relationship between treatment status and suicidality status. Dropouts were not related to baseline characteristics, such as age, baseline severity, or baseline suicidality; therefore, it is feasible that dropouts do not have more severe initial disease. Treatment discontinuation might be related to the study procedures or to the characteristics of the treatment. The most common reason for drop out in the TEAM study was “changed mind” (52% of dropouts), followed by “side effects” (22% of dropouts). Analysis that included both omitting dropouts as well as LOCF methods yielded similar conclusions.

The titration schedule for VAL and LI was gradual in order to maximize tolerability and mimic standard clinical care. Previous reports of the TEAM study have addressed tolerability vis-a-vis the titration schedules for the medications.16,17 RISP also had a gradual titration schedule, though it was not correlated to serum levels, as were VAL and LI. However, regardless of the titration schedule, the improvement with RISP was superior in terms of manic symptoms and more rapid in terms of depressive symptoms. All medicines had gradual titration schedules, but even so, the improvement with risperidone was rapidly realized in the sample and significantly better than the rate of improvement for the other two treatments.

The apparent more rapid improvement yielded by risperidone may have particular clinical significance. Risperidone is an atypical antipsychotic, thus it may be thought to cause a global calming effect rather than an acute antidepressant effect. However, the extent of improvement was sustained throughout the course of the study and led to improved symptoms to the same extent as the other treatments, albeit more rapidly. Effective treatment of depression present during manic/mixed states may involve more than a typical antidepressant effect offered by traditional mood stabilizers.

The existing literature is scant regarding optimal treatment of bipolar depression in pediatrics, with only one double-blinded randomized clinical trial having been reported. A recent double-blind placebo-controlled trial found that CDRS scores rapidly improved with an olanzapine/fluoxetine combination18. One uncontrolled, open-label study of 20 participants suggests improvement with lamotrigine either as monotherapy or as an adjunct19. A recent pharmacy usage study found that nearly half of the children and adolescents with bipolar depression take a combination of a traditional mood stabilizer (anticonvulsant or lithium) and an antipsychotic; few are on monotherapy with a single antidepressant or mood stabilizer20. A number of second-generation antipsychotic medications have FDA indications in adults for treatment of bipolar depression, namely, olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, quetiapine, and lurasidone21, 22. Two studies of risperidone in adults with bipolar depression have found either no clear benefit in a treatment refractory population or modest benefit as an adjunctive treatment.23,24 Despite increasing interest, a clear consensus for how best to treat bipolar depression in adults is still elusive25. Applicability to pediatric populations may be difficult to infer, especially as trials are often geared to mania as opposed to mixed mood states, which are typical in pediatrics.

Despite our finding that risperidone improved depressive symptoms quickly, all three medicines eventually led to an improvement in depressive symptoms. Although solid treatment reccomendations are speculative at this stage, this differential rate of response may motivate future investigations exploring the role of polypharmacy. If a differential rate of response is replicated in subsequent studies, then risperidone may be initiated along with a traditional mood stabilizer in order to take advantage of rapid improvement in depression and suicidality. After the traditional mood stabilizer yields sufficient therapeutic benefit, risperidone may be tapered in order to lower the risks of weight gain or metabolic side effects that were identified in the primary report of the TEAM study16. Although the sample was very small, a recent study in adults showed improvement in bipolar depression happened more quickly with a combination of risperidone and valproic acid verus risperidone alone26. Similar to our study, this group found that despite the early improvement, at study end, both groups had the same degree of improvement.

Important limitations should be considered with this study. The first is that this analysis reflects a secondary review of the data. The primary outcome measures for the TEAM study emphasized mania ratings, not depression ratings. As such, depression ratings did not necessarily correlate between the assessment tools. For example, baseline suicidality rates were not comparable to the weekly ratings, since at baseline, lifetime symptoms of suicidality were measured as opposed to weekly ratings that only reflected a single week in the study.

A second limitation involves missing data due to dropouts. Having more detailed information on reasons for discontinuing the treatment would have improved assessment of depression and suicidality status for the dropouts. We addressed this limitation by using multiple methods of analysis for both CDRS scores and suicidality assuming missing at random and no significant change in depression or suicidality after study termination. Overall results did not appreciably change when considering all data available, LOCF, or completers only. Modeling for suicidality also included assigning best case, worst case or qualified outcomes for dropouts, although it did not differ in terms of treatment groups. We settled upon reporting all available data and LOCF for CDRS scores, as it appeared to be the most balanced approach in handling outcome attributions for the various group assignments and patterns of dropouts. In addition, we assigned “non-response” status to dropouts in logistic regression models for week-8 CGI-BP-I-D ratings. Although this may artificially attribute negative outcomes to dropouts, the conclusions regarding treatment outcomes were nevertheless consistent. We also reported outcomes for completers and did not find significant differences in overall outcomes.

For suicidality status, we also applied additional methods of analyses to account for dropouts. We considered best case, worst case and attribution scenarios. It became clear that differing levels of analyses magnified dropout effects in treatment groups in various ways. More dropouts occurred in the LI group, so if best-case scenarios were applied, then LI appeared to have a better outcome. Similarly, if data were restricted to completers only, then negative outcomes related to dropouts were not considered. Overall, we considered LOCF as the most informative parameter; however, additional analyses are also provided as supplemental data. There was no overall treatment effect on suicidality status. Suicidality as measured by one item on CDRS score is uncommon in this sample, so statistical analysis of this particular item may be less meaningful.

Another limitation is sample size. Thus, weekly ratings reflecting non-significant trends in our data set may ultimately prove to be significant with higher participant numbers. Since VAL and LI arms had a higher proportion of dropouts, if drop out is associated with a worse patient outcome, it is more likely that the initial improvement seen in the RISP group compared to LI and VAL is not limited to first 3 weeks of treatment. Some uncertainty exists as to the depression status at baseline. Given that this study included a variety of manic and mixed manic states, depressive symptoms were very common. Additional analysis limited to high CDRS baseline scores did not change the overall finding, though restriction to higher baseline scores limited the sample size. Despite these limitations, given the paucity of data in this area, this study still provides meaningful information about children who are treated for BD.

In this study, the evidence suggests that the most rapid symptom resolution may occur with risperidone. Given the need for rapid stabilization in the face of depression or suicidality, evidence for rapid treatment improvement may have important treatment implications. As the trend for treatment of bipolar depression in adults changes to emphasize primary use of mood stabilizers, it may be that the trend will similarly change for pediatric BD27, 28. Treatment for BD may not be consistent between children and adults, but risk for suicidality in BD is high in both groups. All three medicines are effective, though from this analysis, risperidone may be preferred in clinical circumstances that require rapid stabilization of depression in children and adolescents with acute mania or mixed mood states of BD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study received funding from NIMH cooperative agreement grants U01 MH064846 (Geller/WU), U01 MH064850 (Wagner/UTMB), U01 MH064851 (Axelson/Pitt), U01 MH064868 (Luby/WU), U01 MH064869 (Walkup/JHU), U01 MH064887 (Joshi/CNMC), and U01 MH064911 (discontinued site/reallocated). Partial support for statistical work was also received from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; 1UL1TR001079).

Dr. Yenokyan served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the pivotal contributions of Barbara Geller, MD, of Washington University, in designing and overseeing this project from its inception through to its publication.

The opinions and assertions contained in this report are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIH, or NIMH. Disclosure: Dr. Salpekar has served as a member of a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for studies sponsored by the NIMH Intramural Program. He has received honoraria from the Gulf Child Mental and Behavioral Health Society and has served as a consultant for Sunovion. Dr. Joshi holds leadership positions as president of AACAP for the term 2013-2015 and as a psychiatry director of the ABPN. Dr. Axelson has served as a consultant for Janssen Research and Development and has received royalties from Wolters Kluwer. Dr. Reinblatt has received research funding from NIMH and honoraria from the Osler Institute and the National Board of Medical Examiners. Dr. Walkup has received free drug/placebo from the following pharmaceutical companies for NIMH-funded studies: Eli Lilly and Co. (2003), Pfizer (2007), and Abbott (2005). He was paid for a one-time consultation with Shire (2011). He is a paid speaker for the Tourette Syndrome - Center for Disease Control and Prevention outreach educational programs, AACAP, and the American Psychiatric Association. He has received royalties for books on Tourette syndrome from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press. He has received grant funding from the Hartwell Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association. He is an unpaid advisor to the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, Consumer Reports, and the Trichotillomania Learning Center. Dr. Vitiello has received salary support from NIH, income from private practice, and consultant fees from the American Physician Institute for Advanced Professional Studies. Dr. Luby has received grant or research support from NIMH. She has received royalties from Guilford Press. Dr. Wagner has received honoraria from UBM Medica, the Las Vegas Psychiatric Society, AACAP, Partners Healthcare, Weill Cornell Medical School, and the Nevada Psychiatric Association. Dr. Riddle has received research funding from NIH and honoraria from the REACH Institute and has served as a member of a DSMB for studies supported by the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act and sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). He has served on a committee of the Institute of Medicine, has provided expert witness testimony for Teva Canada, and has received aripiprazole from Bristol-Myers Squibb for an NIMH-sponsored study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

This article was reviewed under and accepted by ad hoc editor Argyris Stringaris, MD, PhD, MRCPsych.

Clinical trial registration information: Study of Outcome and Safety of Lithium, Divalproex and Risperidone for Mania in Children and Adolescents (TEAM);; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00057681.

Drs. Yenokyan and Nusrat and Ms. Sanyal report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jay A. Salpekar, Kennedy Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore..

Dr. Paramjit T. Joshi, Children's National Medical Center and George Washington University, Washington, DC.; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) and with the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN).

Dr. David A. Axelson, Nationwide Children's Hospital and The Ohio State University, Columbus..

Dr. Shauna P. Reinblatt, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine..

Dr. Gayane Yenokyan, Johns Hopkins Biostatistics Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

Ms. Abanti Sanyal, Johns Hopkins Biostatistics Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

Dr. John Walkup, New York Presbyterian Hospital—Weill Cornell Medical College, New York..

Dr. Benedetto Vitiello, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Bethesda, MD..

Dr. Joan Luby, Washington University in St. Louis..

Dr. Karen Dineen Wagner, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston..

Dr. Nasima Nusrat, Children's National Medical Center and George Washington University, Washington, DC..

Dr. Mark A. Riddle, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine..

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu HY, Potter MP, Woodworth KY, et al. Pharmacologic treatments for pediatric bipolar disorder: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):749–762. e39. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW. Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):846–871. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000170554.23422.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halfon N, Labelle R, Cohen D, Guile JM, Breton JJ. Juvenile bipolar disorder and suicidality: a review of the last 10 years of literature. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(3):139–151. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fornaro M, Martino M, De Pasquale C, Moussaoui D. The argument of antidepressant drugs in the treatment of bipolar depression: mixed evidence or mixed states? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(14):2037–2051. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.719877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosgrove VE, Roybal D, Chang KD. Bipolar depression in pediatric populations : epidemiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2013;15(2):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s40272-013-0022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, et al. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1113–1122. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force Report on Antidepressant Use in Bipolar Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249–1262. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaemi SN, Wingo AP, Filkowski MA, Baldessarini RJ. Long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(5):347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strejilevich SA, Martino DJ, Marengo E, et al. Long-term worsening of bipolar disorder related with frequency of antidepressant exposure. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(3):186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazquez G, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Comparison of antidepressant responses in patients with bipolar vs. unipolar depression: a meta-analytic review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(1):21–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muzina DJ, Elhaj O, Gajwani P, Gao K, Calabrese JR. Lamotrigine and antiepileptic drugs as mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2005;(426):21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein BI. Recent progress in understanding pediatric bipolar disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):362–371. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strawn JR, Adler CM, McNamara RK, et al. Antidepressant tolerability in anxious and depressed youth at high risk for bipolar disorder: a prospective naturalistic treatment study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):523–30. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser M, Galling B, Correll CU. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence rates, correlates, and targeted interventions. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(5):507–523. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geller B, Luby JL, Joshi P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of risperidone, lithium, or divalproex sodium for initial treatment of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed phase, in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):515–528. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitiello B, Riddle MA, Yenokyan G, et al. Treatment moderators and predictors of outcome in the Treatment of Early Age Mania (TEAM) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):867–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Detke HC, DelBello MP, Landry J, Usher RW. Olanzapine/Fluoxetine combination in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang K, Saxena K, Howe M. An open-label study of lamotrigine adjunct or monotherapy for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:298–304. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000194566.86160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhowmik D, Aparasu RR, Rajan SS, Sherer JT, Ochoa-Perez M, Chen H. The utilization of psychopharmacological treatment and medication adherence among Medicaid enrolled children and adolescents with bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frye MA, Prieto ML, Bobo WV, et al. Current landscape, unmet needs, and future directions for treatment of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S17–23. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(14)70005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor DM, Cornelius V, Smith L, Young AH. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:452–469. doi: 10.1111/acps.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a STEP-BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:210–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shelton RC, Stahl SM. Risperidone and paroxetine given singly and in combination for bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1715–1719. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller S, Dell'Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S3–11. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(14)70003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moosavi SM, Ahmadi M, Monajemi MB. Risperidone versus risperidone plus sodium valproate for treatment of bipolar disorders: a randomized, double-blind clinical-trial. Glob j health sci. 2014;6:163–7. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeFilippis MS, Wagner KD. Bipolar depression in children and adolescents. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:209–13. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang K. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric bipolar depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:73–80. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/kchang. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.