Abstract

Fibulins are extracellular matrix proteins associated with elastic fibres. Homozygous Fibulin-4 mutations lead to life-threatening abnormalities such as aortic aneurysms. Aortic aneurysms in Fibulin-4 mutant mice were associated with upregulation of TGF-β signalling. How Fibulin-4 deficiency leads to deregulation of the TGF-β pathway is largely unknown. Isolated aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) from Fibulin-4 deficient mice showed reduced growth, which could be reversed by treatment with TGF-β neutralizing antibodies. In Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs increased TGF-β signalling was detected using a transcriptional reporter assay and by increased SMAD2 phosphorylation. Next, we investigated if the increased activity was due to increased levels of the three TGF-β isoforms. These data revealed slightly increased TGF-β1 and markedly increased TGF-β2 levels. Significantly increased TGF-β2 levels were also detectable in plasma from homozygous Fibulin-4R/R mice, not in wild type mice. TGF-β2 levels were reduced after losartan treatment, an angiotensin-II type-1 receptor blocker, known to prevent aortic aneurysm formation. In conclusion, we have shown increased TGF-β signalling in isolated SMCs from Fibulin-4 deficient mouse aortas, not only caused by increased levels of TGF-β1, but especially TGF-β2. These data provide new insights in the molecular interaction between Fibulin-4 and TGF-β pathway regulation in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysms.

In developed countries 1–2% of all deaths are caused by aortic aneurysms and dissections1. In these countries the incidence of thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) is approximately 25 per 100,000 persons per year2. In general, a TAA is characterized by degeneration of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), including (phenotypic) loss of SMCs and changes in SMC proliferation3,4,5. Several genes have been identified in both syndromic and non-syndromic forms of TAA, including ECM genes, genes encoding contractile proteins in SMCs and genes involved in the regulation of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathway6,7,8.

There are three mammalian TGF-β isoforms: TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3. They are encoded by different genes, but show a high degree of amino acid sequence homology. All TGF-β isoforms bind to the latency-associated protein (LAP) and via the latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP) to the ECM. Upon activation TGF-βs can bind to the type-II TGF-β receptors (TβRII), which recruit the type-I TGF-β receptor (TβRI), also called activin receptor-like kinase (ALK)-5. ALK-5 is transphosphorylated by TβRII and subsequently downstream SMAD proteins (i.e. SMAD2/3) are phosphorylated. Activated SMAD2 and -3 associate with SMAD4, leading to translocation to the nucleus where they interact with target gene promoters and regulate transcription of genes encoding for plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-I, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and ECM proteins9.

A crucial role for the TGF-β pathway in syndromes associated with TAA became evident from both studies in patients and in mouse models10,11,12,13,14. Although TAAs are usually associated with increased TGF-β signalling, this association has also been observed with loss of function mutations in TGF-β and TGF-β receptors15. The identification of these mutations has led to new insights in the pathogenesis of aneurysm formation, but the molecular mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Mutations in genes of the TGF-β pathway and the ECM lead to phenotypic and functional SMC loss: Tgfbr2 mutations in Loeys-Dietz syndrome lead to decreased expression of SMC contractile proteins5. Furthermore, SMCs from mice with Marfan syndrome, another syndromic form of TAAs caused by mutations in the ECM glycoprotein Fibrillin-1, display an altered expression profile with morphological changes, but retain expression of vascular SMC markers4. In addition, increased TGF-β signalling inhibits proliferation of SMCs16.

Upregulated TGF-β signalling has been observed in another heritable form of TAA caused by a deficiency in the extracellular matrix protein Fibulin-413,17,18,19,20. Fibulin-4 regulates proper elastogenesis by tethering lysyl oxidase to tropoelastin to facilitate crosslinking21,22. In Fibulin-4 deficient patients and mice elevated TGF-β signalling has been shown12,13,20. However, the exact mechanism by which Fibulin-4 deficiency leads to increased TGF-β signalling remains to be determined. To further investigate this we isolated SMCs from the aortic arch of hypomorphic Fibulin-4 (Fibulin-4R/R) mice, displaying a 4-fold reduction of Fibulin-4 expression. This leads to congenital vascular abnormalities in these mice, including TAAs and vascular tortuosity12. Heterozygous Fibulin-4+/R mice, which have a 2-fold reduced Fibulin-4 expression, show minor irregularities and ECM changes in the aortic wall. Our data reveal that TGF-β signalling is enhanced in isolated SMCs derived from the aortas of Fibulin-4 deficient mice. We observed a decreased proliferation rate in Fibulin-4R/R SMCs, which could be reverted by addition of TGF-β neutralizing antibodies. We found that this increased TGF-β signal transduction activity is not only associated with increased levels of TGF-β1, but especially with enhanced TGF-β2 levels. Increased levels of TGF-β2 could also be detected in blood and aortic tissue lysates of the Fibulin-4R/R mice. Treatment of Fibulin-4R/R mice with losartan, an angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker, reduced the increased TGF-β2 levels in blood plasma. This study shows that increased TGF-β signalling in SMCs of Fibulin-4 deficient mice leads to decreased proliferation of SMCs and could be caused by increased bioavailability of TGF-β1 and especially TGF-β2.

Results

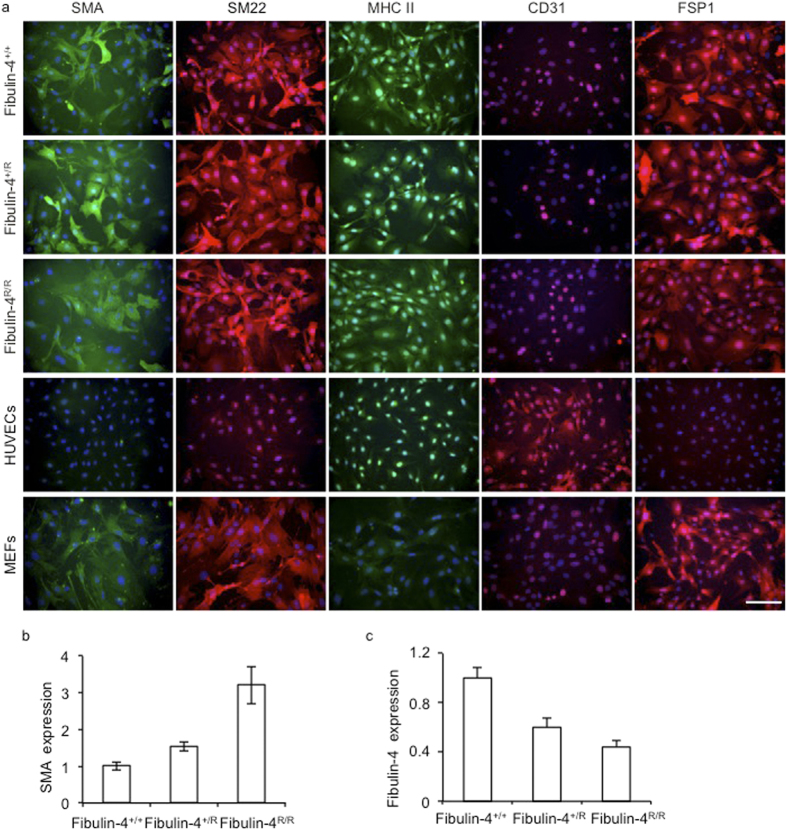

Characterization of SMCs derived from Fibulin-4 deficient aortas

To examine TGF-β signalling in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs, we isolated SMCs from the aortic arches of Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice. To confirm that the cells we isolated were SMCs, the cells were analysed for the presence of SMC markers, including α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), smooth muscle specific protein-22 (SM22), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain II (MHC II) and fibroblast specific protein 1 (FSP1), which stains SMCs with a rhomboid phenotype23,24. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were taken along as positive control for CD31 staining and were negative for all other markers, while mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were positive controls for FSP1, and SMA and SM22 staining25. Isolated SMCs showed positive staining for α-SMA, SM22, MHC II, FSP1 and were negative for CD31 (Fig. 1a) confirming the SMC phenotype. QPCR expression analysis also showed no detectable CD31 and von Willebrand Factor (an additional endothelial marker) mRNA expression (data not shown). α-SMA was highly expressed and seemed somewhat increased in Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs (Fig. 1b). Next, the levels of Fibulin-4 were analysed by QPCR. These data revealed that expression levels of Fibulin-4 mRNA in Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs were downregulated (Fig. 1c). These data show that we isolated a population of SMCs with a gradual reduced Fibulin-4 expression level, which we used for further cell biological and molecular analyses.

Figure 1. Characterization of isolated SMCs from the aortic arch.

(a) Immunofluorescent staining of aortic SMCs isolated from Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/Rmice showed that these cells stained positively for SMA, SM22, MHC II and FSP1. The SMCs were negative for the endothelial marker CD31, while HUVECs were positive. HUVECs were negative for all other stainings. MEFs stained positive for SMA, SM22 and FSP1 and were negative for MHC II and CD31. Magnification 20x, scale bar 100 μm. (b) Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show gradual increased SMA mRNA expression levels compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. (c) Fibulin-4 mRNA expression in SMCs. Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show gradual decreased Fibulin-4 mRNA expression levels compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs.

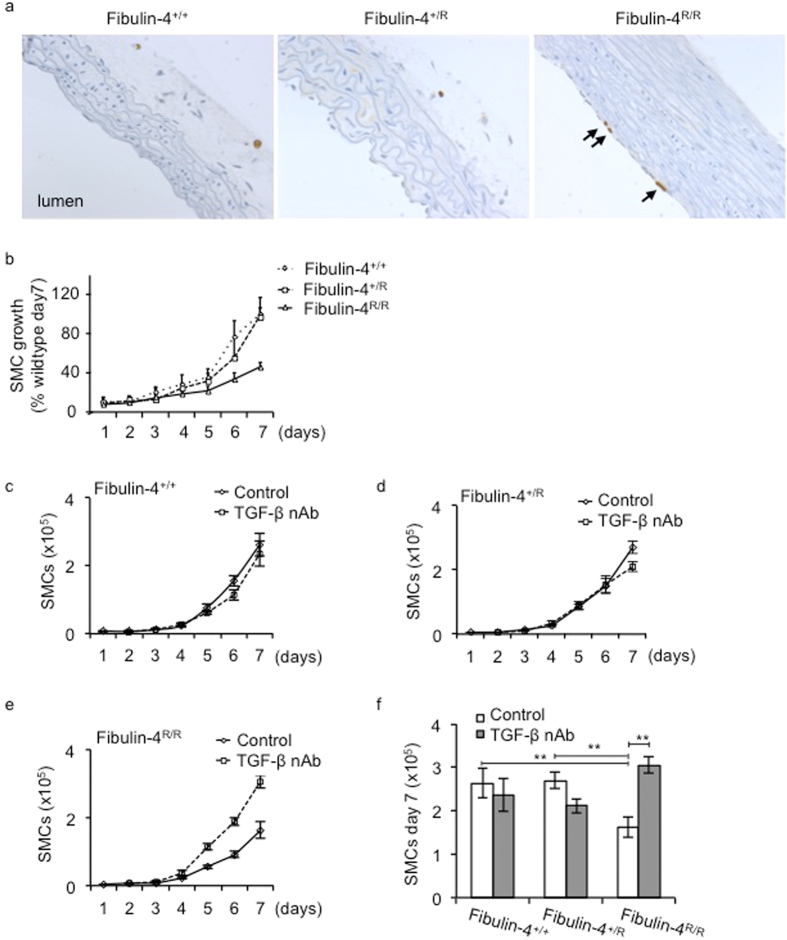

TGF-β reduces proliferation of Fibulin-4 R/R SMCs

Previously we showed in 10 days old Fibulin-4R/R mice increased BrdU uptake indicating increased proliferation of SMCs, leading to changes in the tunica adventitia of the aorta12. However, in adult Fibulin-4R/R mice (100 days old) increased proliferation was observed specifically in the endothelial layer (Fig. 2a). No proliferation of SMCs in the adventitia or media of the aortic wall was observed. Next, we analysed proliferation rates of the SMCs with reduced Fibulin-4 expression in vitro. Figure 2b shows similar growth rates of all three genotypes until day 5, after which proliferation was decreased in Fibulin-4R/R SMCs. As TGF-β can inhibit cell proliferation, we determined whether the reduced growth of Fibulin-4R/R SMCs is a consequence of increased TGF-β activity. Therefore, SMCs were treated with TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (nAb), which neutralize all three TGF-β isoforms26,27. Treatment with the TGF-β nAb reversed the growth inhibition observed in Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (Fig. 2c–f). On day 7 the number of Fibulin-4R/R SMCs was significantly increased after treatment with TGF-β nAb compared to non-treated Fibulin-4R/R SMCs. Moreover, proliferation was similar to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. These data indicate that Fibulin-4 deficiency leads to increased TGF-β, which inhibits proliferation of SMCs.

Figure 2. Reduced proliferation of Fibulin-4R/R SMCs is reversed by inhibition of the TGF-β pathway.

(a) Increased BrdU uptake indicating active proliferation of endothelial cells is present in the aortic wall from 100 days old Fibulin-4R/R mice and is indicated by the arrows. (b) Growth analyses of Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs revealed a reduced growth starting from day 5 for Fibulin-4R/R SMCs as compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (3 dishes per experiment were counted and the average of 3 independent experiments is shown). Treatment of (c) Fibulin-4+/+, (d) Fibulin-4+/R and (e,f) Fibulin-4R/R SMCs with TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (nAb) significantly increased proliferation of Fibulin-4R/R SMCs from day 5. (f) At day 7 the number of treated Fibulin-4R/R SMCs was significantly higher and comparable to the amount of Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Data represent 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

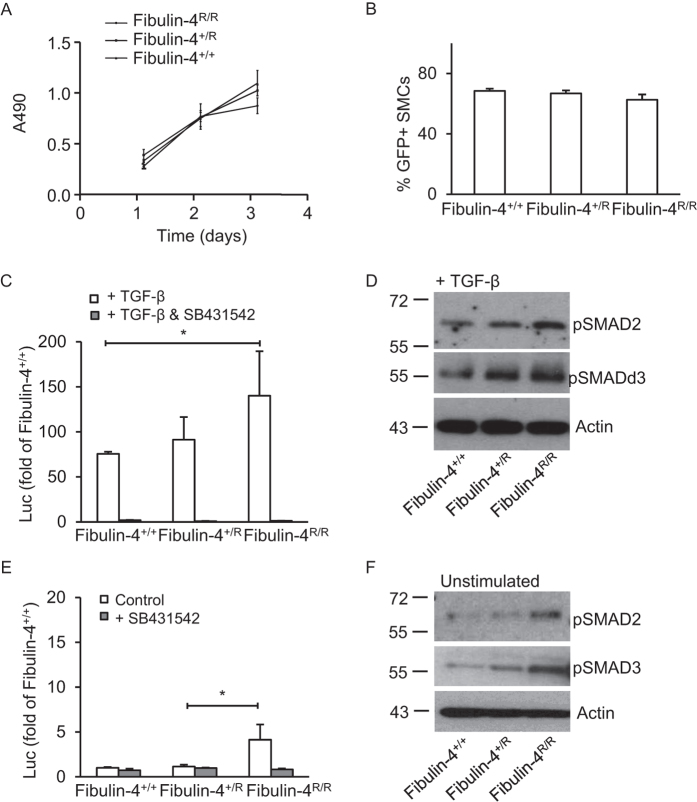

Fibulin-4 expression regulates TGF-β signalling in aortic SMCs

Since we observed that TGF-β neutralizing antibodies revert the decreased proliferation rates of Fibulin-4R/R SMCs, we further analysed transcriptional consequences of increased TGF-β signalling in these cells using a SMAD3/SMAD4 dependent promoter transcriptional reporter construct (CAGA-luciferase)28. Although there was a difference in proliferation between different genotypes at later time points, this was not observed during the shorter duration of this assay (Fig. 3a). To determine whether transfection efficiency was similar between the different genotypes a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing construct was transfected and GFP expression determined. Flow cytometric analysis showed no differences between the percentages of GFP expressing Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs (Fig. 3b) and thus no differences in transfection efficiencies among these different genotype. Next, we used the CAGA-luciferase reporter construct to assess TGF-β signalling activity in Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs. Stimulation with TGF-β of Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs showed a strong induction of luciferase activity, which was increased in a Fibulin-4 dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3c). Addition of the TβRI kinase inhibitor SB431542, a compound selectively blocking TGF-β type-I receptor kinase activity29, abolished TGF-β-induced transcriptional responses. Analysis of downstream pSMAD2 and pSMAD3 by western blotting revealed a gradual increase in SMAD2 and SMAD3 phosphorylation after stimulation with TGF-β in Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (Fig. 3d), confirming the CAGA-luciferase reporter data. These data indicate that Fibullin-4 deficient cells show increased signalling upon exogenous TGF-β stimulation.

Figure 3. Increased TGF-β signalling in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs.

(a) Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show similar proliferation rates in the time course of the experiment (MTS proliferation assay) (b) Transfection with green fluorescent protein (GFP) encoding plasmids display no difference in percentage of transfected SMCs between Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs. (c) The TGF-β response assay reveals a gradual increase in TGF-β activity in Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs, after stimulation with exogenous TGF-β. Data represent fold change relative to unstimulated Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. Addition of the ALK-5 kinase inhibitor (SB431542) abolishes the TGF-β response in Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs. (d) Western blot analyses for TGF-β signalling downstream mediators pSMAD2 and pSMAD3 on TGF-β stimulated SMCs show a gradual increase in TGF-β signalling in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. (e) Measurement of basal TGF-β activity (no stimulation with exogenous TGF-β) by the CAGA-luciferase reporter show increased TGF-β activity in Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs, which can be inhibited by the TβRI kinase inhibitor SB431542. (f) These data were confirmed by western blot analyses for pSMAD2 and pSMAD3. All data shown are representative for in total n = 3 independent experiments and all performed under serum starved conditions (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To explore whether basal TGF-β signalling is also affected in Fibulin-4 deficient cells, SMCs were transfected with the CAGA-luciferase reporter and TGF-β signalling without exogenous addition of TGF-β ligand was analysed. This showed that luciferase activity was already increased in untreated Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (Fig. 3e). This could be reversed by SB431542, suggesting a TGF-β mediated effect. Western blot analysis showed gradually increased basal phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in untreated Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs (Fig. 3f). Taken together, these data indicate that increased phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 leads to enhanced transcriptional activation of downstream TGF- β signalling genes and reduced growth in Fibulin-4 mutant cells.

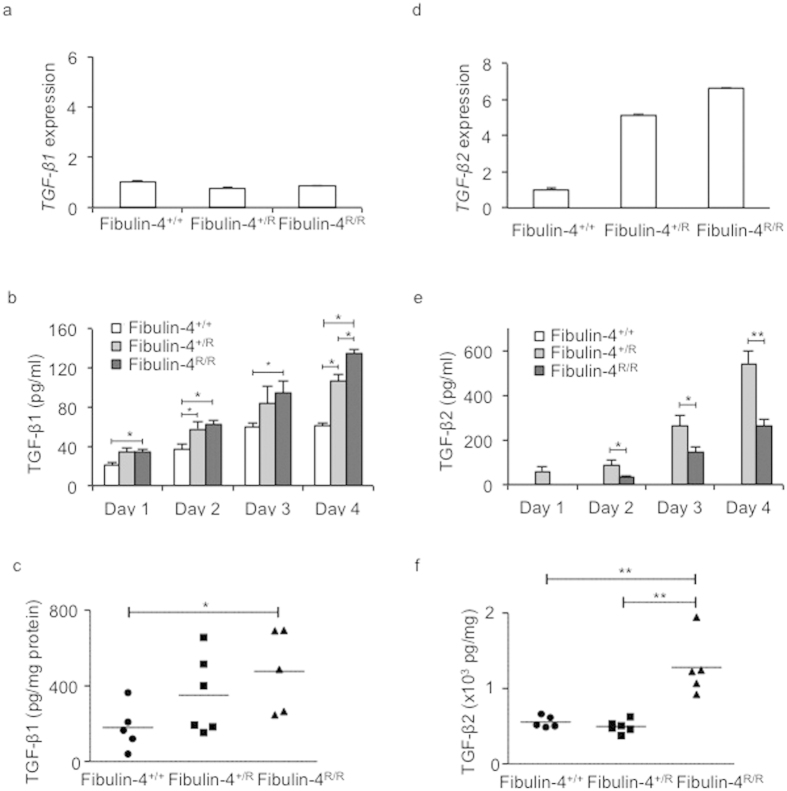

Increased TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 levels in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs

Since we observed increased basal TGF-β signalling in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs, we analysed whether this was due to increased TGF-β levels. Subconfluent Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs were serum-starved and conditioned medium was collected for 4 consecutive days to determine TGF-β1, − β2 and −β 3 levels. TGF-β3 levels were very low and did not differ between the different genotypes (data not shown). Although Tgf-β1 mRNA levels in SMCs did not differ between the genotypes (Fig. 4a), TGF-β1 levels in Fibulin-4R/R SMCs conditioned medium were higher compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (Fig. 4b). Conditioned medium from Fibulin-4+/R SMCs showed intermediate TGF-β1 levels. To analyse whether the increased TGF-β1 levels were also observed in vivo, we prepared lysates from aortic arches of Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice and measured TGF-β1 levels. These data revealed a similar gradual increase in TGF-β1 levels in aortic arch lysates of Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Strong increase of TGF-β2 levels in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs.

(a) Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show equal Tgf-β1 mRNA expression levels compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. (b) Increased TGF-β1 levels measured in conditioned medium (CM) from Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ CM on day 1–4 after serum starvation. Fibulin-4+/R SMCs showed significant increased TGF-β1 levels on day 2 and 4 after serum starvation compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. Furthermore, on day 4 Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show significant increased TGF-β1 levels compared to Fibulin-4+/RSMCs (n = 4 per day for each genotype). Two-way ANOVA analysis for genotype and between days p < 0.05. (c) Gradually increased TGF-β1 is also observed in aortic arch lysates of Fibulin-4+/R (n = 6) and Fibulin-4R/R mice (n = 5) compared to Fibulin-4+/+ aortas (n = 5). This increase is significant in Fibulin-4R/R aortic arch lysates compared to Fibulin-4+/+ aortic arch lysates. (d) Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs show gradual increased Tgf-β2 mRNA expression levels compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs. (e) Measurement of TGF-β2 revealed markedly increased levels in CM of Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs, while TGF-β2 was undetectable in CM of Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs (experiments were performed in at least 3 independent experiments). Two-way ANOVA analysis for genotype and between days p < 0.05. (f) Measurements in aortic arch lysates display significantly increased TGF-β2 in Fibulin-4R/R aortas compared to Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4+/+ aortas (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

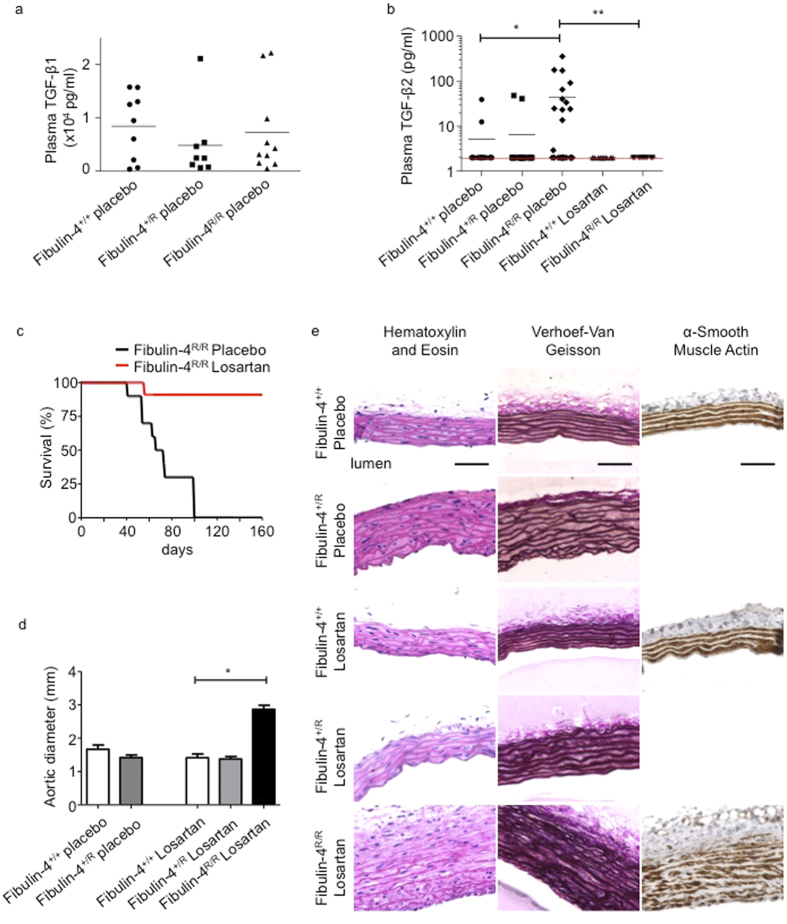

Next, we analysed TGF-β2 expression in the SMCs. Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs showed >5-fold increased Tgf-β2 mRNA expression levels (Fig. 4d). ELISA analysis on conditioned medium from Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs revealed strongly increased TGF-β2 levels in medium from Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs compared to Fibulin-4+/+ SMCs, in which TGF-β2 was undetectable (Fig. 4e). TGF-β2 levels were already significantly higher in conditioned medium from Fibulin-4+/R SMCs. Increased TGF-β2 levels were also detectable in Fibulin-4R/R aortic arch lysates, when compared to aortic arch lysates from Fibulin-4+/+ and Fibulin-4+/R mice (Fig. 4f). Given the increased TGF-β levels in SMCs and aortic tissue derived from Fibulin-4 deficient mice, we determined TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 levels in plasma samples from these mice. TGF-β1 levels were not significantly different among plasma from Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice (Fig. 5a). In contrast, plasma TGF-β2 levels were very low in wild type mice and could be detected in 2 out of 15 Fibulin-4+/+ mice and 2 out of 19 Fibulin-4+/R mice (Fig. 5b). TGF-β2 levels could be detected in plasma from 12 out of 24 Fibulin-4R/R mice with significantly higher concentrations compared to Fibulin-4+/+ and Fibulin-4+/R mice. These data show that specifically TGF-β2 levels in aortic tissue and plasma of Fibulin-4 deficient mice are strongly increased.

Figure 5. Increased levels of TGF-β2 are detectable in plasma from 100 days old Fibulin-4R/R mice, which reduces on Losartan treatment.

(a) TGF-β1 measurements in plasma samples showed no difference between placebo treated Fibulin-4+/+ (n = 9), Fibulin-4+/R (n = 8) and Fibulin-4R/R mice (n = 10). (b) TGF-β2 was detectable in plasma of 12 out of 24 placebo treated Fibulin-4R/R mice compared to only 2 out of 15 in placebo treated Fibulin-4+/+ mice and 2 out of 19 in Fibulin-4+/R mice. TGF-β2 levels are significantly higher in Fibulin-4R/R mice compared to placebo treated Fibulin-4+/+ and Fibulin-4+/R mice. Losartan treatment of Fibulin-4R/R mice seemed to reduce the TGF-β2 levels (0 out of 9) as compared to placebo treated Fibulin-4R/R mice. The red line indicates the detection of the ELISA (Chi-square p < 0.001). (c) Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows an increased survival of Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/Rmice compared to placebo treated Fibulin-4R/Rmice. (d) Aortic diameter of 160 days old placebo and losartan treated Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R mice and Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/R mice. Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/Rmice have significantly enlarged aortic diameters compared to wild type mice, while there are no differences between placebo and Losartan Fibulin-4+/Rmice and wild type mice. (e) HE, elastin and αSMA staining of ascending thoracic aortas. Placebo and losartan treated Fibulin-4+/R mice (160 days old) show an increase in aortic wall thickness and some elastin breaks compared to Fibulin-4+/+ mice. Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/Rmice show despite of their survival disrupted aortic wall architecture. In addition, despite losartan treatment there is loss of smooth muscle cell content in the media of Fibulin-4R/R mice. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Losartan treatment rescues lethality and lowers plasma TGF-β2 levels in Fibulin-4 R/R mice

Next, adult mice were treated with Losartan, an angiotensin-II type-I receptor blocker, which prevents aortic root enlargement and reduces circulating TGF-β1 in a Marfan mouse model30. Compared to the increased secretion of TGF-β2 in placebo treated Fibulin-4R/R mice we observed, TGF-β2 levels were not detectable in the 10 losartan treated Fibulin-4R/R mice. Consistent with previous studies31, Losartan treatment of wild type, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice showed improved survival rates of Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/R mice until at least the age of 160 days compared to placebo treated Fibulin-4R/R mice, which maximally survive until the age of 100 days (Fig. 5c). All losartan and placebo treated wild type and Fibulin-4+/R mice survived at least until the duration of the experiment (data not shown). Despite improved survival, 160 days old Losartan treated Fibulin-4R/R mice developed significantly enlarged aortic diameters compared to losartan treated wild type mice (Fig. 5d), and a thickened and degenerated aortic wall architecture as evidenced by fragmentation of its elastin layers (Fig. 5e). Previously, we showed a reduced SMA staining in the aortic wall of 100 days old Fibulin-4 deficient mice, indicative for SMC loss31. This SMC loss is not ameliorated by losartan treatment of Fibulin-4R/R mice (Fig. 5e). Both placebo and Losartan treated Fibulin-4+/R mice showed an increase in aortic wall thickness and minor elastin breaks compared to wild type mice, which was also previously observed in non-treated Fibulin-4+/R mice12. These results show that lethality and increased plasma TGF-β2 levels in Fibulin-4R/R mice can be reduced by losartan treatment, showing a causal relation between increased TGF-β signalling and lethality in aneurysmal Fibulin-4 mice.

Discussion

In this study we show that TGF-β signalling is gradually enhanced in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs in a Fibulin-4 dose-dependent manner and influences proliferation of these cells. The increased TGF-β signalling is consistent with increased TGF-β1 levels, and especially with increased TGF-β2 levels, detected in plasma from Fibulin-4 deficient mice.

Previous analyses on aortas from Fibulin-4 deficient mice showed increased TGF-β signalling associated with aneurysm formation by gene expression analysis and increased nuclear pSMAD2 staining in the SMCs of these aortas12. Isolation of aortic SMCs from these mice provided the opportunity to assess TGF-β signalling in vitro. Fibulin-4R/R SMCs have a reduced proliferation rate compared to Fibulin-4+/R and wild type SMCs, which is reversed by TGF-β inhibition. Reduced proliferation only takes place after a prolonged incubation time, which is most probably caused by the requirement of certain levels of TGF-β before it affects the proliferation rates of the SMCs. However, in the aortic wall local active TGF-β concentrations can be much higher, due to local activation of the ECM bound TGF-β. In our previous studies we found a hyperproliferation of SMCs as well as a decreased SMC content in the aortic wall of Fibulin-4 deficient mice12,31. The hyperproliferation of SMCs was specifically found in the adventitial layers of the aortic wall of newborns. Tsai et al. showed that TGF-β can transform from an inhibitor to a stimulant of SMC proliferation in the context of elevated SMAD332. We observed a gradual increase in TGF-β signalling in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs, which could be reverted by inhibition of TGF-β. These data indicate that the proliferation of Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs is reduced due to increased TGF-β signalling, thereby potentially contributing to aortic aneurysm formation.

ELISA analyses point to increased TGF-β1 levels in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs and strongly increased TGF-β2 levels, also detected in plasma of Fibulin-4R/R mice. The three TGF-β isoforms are involved in both overlapping and divergent roles. While Tgf-β1 null mice develop an autoimmune-like inflammatory disease33 and Tgf-β3 knockout mice show abnormal lung development and cleft palate34, Tgf-β2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects, including cardiovascular, pulmonary, skeletal, ocular, inner ear and urogenital manifestations35. Tgf-β2 heterozygous mutations in patients result in a different phenotype compared to Tgf-β2 knock-out mice15. TGF-β2 haplo-insufficiency predisposes for adult-onset vascular disease, including aortic tortuosity and dilation, cerebrovascular disease and mitral valve disease, which overlaps with the phenotype of Fibulin-4 deficient patients. The phenotype of the TGF-β2 deficient patients also shows overlap with other TGF-β signalopathies including Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, the aneurysm-osteoarthritis syndrome and similarly present with a paradoxical, probably compensatory, local increase in TGF-β1 and TGF-β2. Furthermore, increased Tgf-β2 expression has been detected in patients with the Loeys-Dietz syndrome36. The fact that TGF-β2 haplo-insufficiency results in a cardiovascular phenotype and local increased TGF-β2, stresses the potential importance of TGF-β2 in the vasculopathy. For various TGF-β superfamily members it is known that their effects are very concentration dependent37,38. Very high or very low levels of these cytokines can have similar or opposite effects on cells. In addition, crucial in the regulation of TGF-β activity is its activation from the latent ECM-bound complexes. This might explain the, at first sight, contradictory findings. This also suggests that increased TGF-β2 expression is part of a common pathophysiologic process involved in aortic aneurysm formation in these syndromes. Whether it is a direct or indirect consequence of Fibulin-4 deficiency has to be determined in further studies.

We observed that specifically the TGF-β2 isoform is elevated and detected at higher levels in the conditioned medium from these cells and in vivo in aortic lysates and blood. TGF-β2 differs in its receptor binding properties from TGF-β1 and TGF-β3. While TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 have a high affinity for binding to TβRII, TGF-β2 primarily binds to the transforming growth factor type-III receptor (TβRIII), also called betaglycan, after which it presents the ligand to the TβRI-TβRII signalling complex39. Bee et al. showed a specific regulatory role for the TGF-β receptor-IIb (TβRIIb), an alternatively spliced variant of TβRII, in TGF-β2 signal transduction. TβRIIb mutations result in TGF-β2 dependent increased SMAD2 phosphorylation, which is involved in aortic aneurysm progression40. Human SMCs express TβRI, TβRII and TβRIII, while in SMCs derived from atherosclerotic lesions TβRII expression is decreased41. This indicates that alterations in TGF-β receptor expression probably contribute to the regulation of the TGF-β pathway. As our data point to markedly increased TGF-β2 levels in Fibulin-4 deficient SMCs, analyses on TGF-β receptors on these SMCs might further clarify the process of TGF-β regulation and determine its role in the pathogenesis of Fibulin-4 associated aortic aneurysms.

Increased TGF-β levels or TGF-β signalling is associated with multiple diseases. Enhanced TGF-β signalling is known to mediate a pathologic increase in ECM secretion and deposition and is causative for fibrosis in multiple disorders throughout the body42. Overexpression of TGF-β2 is likely to induce trabecular meshwork ECM deposition43 and increased ECM deposition is also observed in aortic aneurysm formation. TGF-β2 is also frequently overexpressed in malignant cancers, where it induces immunosuppression and stimulates metastasis formation44. TGF-β2 expression can be targeted with antisense oligonucleotides, which are currently under investigation in clinical trials45. As inhibition with pan TGF-β neutralizing antibodies is likely to induce side effects, aortic aneurysms associated with increased TGF-β2 might benefit from a TGF-β2 specific intervention decreasing systemic side effects by targeting the other isoforms. In Marfan patients, mouse models for Loeys-Dietz syndrome and transverse aortic constriction (TAC), losartan treatment prevents aortic aneurysm formation accompanied by reduced TGF-β1 levels in patients with Marfan syndrome, and reduced TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 levels in Loeys-Dietz syndrome and TAC mice30,36,46,47. Our data indicate that losartan could also serve as an important therapeutic agent. The exact mechanism how losartan treatment leads to reduced TGF-β signalling needs to be determined.

Fibulin-4 binds LTBP-1 with high affinity and therefore an important role for Fibulin-4 in the association of LTBP-1 with microfibrils is predicted. The large latent complex (LLC), which is formed by LTBP and LAP-bound TGF-β, is linked to microfibrils through binding of LTBP-1 to Fibrillin-1. Therefore, Fibulin-4 might be additionally involved in sequestering of the LLC through LTBP-1 binding48. We speculate that reduced Fibulin-4 levels lead to defective sequestering to the ECM and thereby increased free TGF-β1 and TGF-β2. In conclusion, these data show that SMC derived TGF-β2 is associated with aortic aneurysm formation and levels decrease upon losartan treatment, which improves survival of Fibulin-4 deficient mice. Specific intervention on TGF-β2 could provide more information on its role in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysm formation. In vitro analyses on isolated SMCs provide the opportunity to determine the molecular link between Fibulin-4 and TGF-β pathway regulation, and to further unravel its role in aortic aneurysm formation.

Material and Methods

Animals

Mice containing the Fibulin-4R allele were generated as previously described12. All mice used were bred in a C57BI/6J background and were kept in individually ventilated cages to keep animals consistently micro-flora and disease free. To avoid stress-related vascular injury, mice were earmarked and genotyped 4 weeks after birth. Animals were housed at the Animal Resource Centre (Erasmus University Medical Centre), which operates in compliance with the “Animal Welfare Act” of the Dutch government, using the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” as its standard. As required by Dutch law, formal permission to generate and use genetically modified animals was obtained from the responsible local and national authorities. All animal studies were approved by an independent Animal Ethical Committee (Dutch equivalent of the IACUC).

Treatment of mice

Fibulin-4+/+ and Fibulin-4R/R mice received 0.6 gram/liter losartan (Sigma, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands) or placebo in their drinking water as previously described30,31. Adult Fibulin-4R/R mice and their wild type littermates were treated during 10 weeks or 18 weeks, starting at the age of 5 weeks. Blood samples from placebo or losartan treated Fibulin-4+/+ and Fibulin-4R/R mice were obtained by cardiac puncture and collected in lithium heparin vials (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany).

Isolation of SMCs and cell culture

Vascular SMCs were isolated from the luminal side of the aortic arch from Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R male mice. The tissue was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cut into 5-mm pieces with the luminal side on 0.1% gelatine coated cell culture dishes and incubated. After 7–10 days, smooth muscle-like cell outgrowth was observed. SMCs were maintained in DMEM (Lonza, Leusden, the Netherlands), supplemented with 10% etal calf serum (HyClone, Thermo Scientific, Breda, the Netherlands), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands). Cells were used at passage 5–11.

Immuno-fluorescent and –histochemical stainings

Subconfluent SMCs, Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), isolated as described before49, and Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs), isolated from 8 day old C57/Bl6 mouse embryos, were grown on coverslips and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilised with 0.1% Triton/PBS and blocked with PBS containing 1.5% bovine serum albumin/0.15% glycine (Sigma). Next, coverslips were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies; mouse anti-smooth muscle actin 1:1500 (Progen, Heidelberg, Germany), rabbit polyclonal anti-SM22 alpha antibody 1:400 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse monoclonal anti-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain II 1G12 1:500 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-CD31 1:800 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, USA) and rabbit anti-Fibroblast Specific Protein1 (FSP-1)/S100A4 1:1600 (Millipore, MA, USA). The next day cells were incubated with secondary antibodies anti-mouse alexafluor 488 1:1000 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) for SMA and MHC II and anti-rabbit alexafluor 594 1:1000 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) for SM22, CD31 and FSP-1, and mounted with DAPI. Slides were analysed with the LEICA DMRBE Aristoplan Microscope equipped with the Hamamatsu ORCA-ER Camera. Pictures were taken at 25x magnification. To analyse in vivo SMC content and proliferation 4 μm sections of paraffin embedded aortas were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, elastin (Verhoeff-van Gieson), and α-smooth muscle actin as described before31. BrdU staining was performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Proliferation assay

Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs were seeded in triplicate in 6 cm dishes (5000 cells/well) and allowed to attach overnight. Next, cells were treated with TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (kindly provided by Dr. E. de Heer, Leiden University Medical Centre, Dept. of Pathology26,27) and counted every day using a Burker cell counting chamber. Medium was replaced every other day. The MTS proliferation assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, USA). In short, SMCs were seeded in 96-well plates (1500 cells/well) and allowed to attach overnight. At day-1, -2 and -3 medium was changed to 100 μl complete DMEM + 20 μl MTS substrate and the metabolic activity of the cells was analysed by absorbance change at 490 nm after 2 hours.

TGF-β response assay

TGF-β response in SMCs was determined using (CAGA)12−MLP−Luciferase promoter reporter construct28. This construct contains 12 palindromic repeats of the SMAD3/4 binding element derived from the PAI-1 promoter and was shown to be highly specific and sensitive to TGF-β. The assay was performed as described previously29. In short SMCs were seeded in 1% gelatin coated 24-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Subconfluent cells were transfected using Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A β-galactosidase plasmid was co-transfected to correct for transfection efficiency. After 6 hours, medium was changed to DMEM containing 10% FCS and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. Next, cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β3 (kindly provided by Kenneth K. Iwata, OSI, Inc., New York, USA) in the presence or absence of 10 uM SB431542 (Tocris/R&D systems, Abington, UK) for 6 hours. After stimulation the cells were washed, lysed and luciferase activity was determined according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). β-Galactosidase activity in the lysates was determined using β-gal substrate (0.2 M H2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ortho-nitrophenyl-phosphate, 0.25% β-mercaptoethanol) and measuring absorbance change at 405 nm. The luciferase count was corrected for β-galactosidase activity. The relative increase in luciferase activity was calculated versus controls. All experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate. To determine the transfection efficiency of Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R SMCs they were transfected with a GFP plasmid as described above, trypsinised and fixed with 1% PFA. Subsequently, SMCs were analysed with flow cytometry for the percentage of GFP transfected SMCs compared to the total amount of SMCs.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described before50. In short, equal amounts of protein (DC protein assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) were separated on 10% SDS−polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whattman, Dassel, Germany) and blocked with 5% milk powder in Tris-HCl buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). After washing, blots were overnight incubated with rabbit anti-pSMAD2 (Cell signaling Technologies, USA) and rabbit anti-pSMAD3 (kindly provided by Dr. E. Leof, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (all GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Detection was performed by chemoluminescence according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Afterwards, blots were stripped and reprobed with mouse anti-β-actin antibodies as a loading control.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA concentration and purity was determined spectrometrically. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using random primers. cDNA samples were subjected to 40 cycles real-time PCR analysis using maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix 2× (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) and primers shown in Table 1. Reactions were performed in triplicates for each sample. Product specificity was determined by melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. The average Ct values of the triple reactions were calculated for each gene and all values were normalized for cDNA content by Hprt expression. The levels of fold-change for each gene were calculated relative to the gene expression levels in baseline wild type SMCs. RNA isolated from HUVECs and fibroblasts were used as controls for the genes analysed.

Table 1. Primers used for quantitative real time PCR.

| Genes | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| Fibulin-4 | 5′-GGGTTATTTGTGTCTGCCTCG-3′ | 5′-TGGTAGGAGCCAGGAAGGTT-3′ |

| SMA | 5′-GTCCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAA-3′ | 5′-TCGGATACTTCAGCGTCAGGA-3 |

| TGF-β1 | 5′-CAACAATTCCTGGCGTTACC-3′ | 5′-TGCTGTCACAAGAGCAGTGA-3′ |

| TGF-β2 | 5′-CCGCCCACTTTCTACAGACCC-3′ | 5′-GCGCTGGGTGGGAGATGTTAA-3′ |

Forward and reverse primers are displayed for each gene from 5′ to 3′.

TGF-β ELISAs

SMC conditioned medium was prepared by seeding the cells and growing them to subconfluence. Medium was changed to serum-free DMEM, containing antibiotics as described above, and incubated for 4 days. Samples were collected every day and frozen at −20 until analysis. Lysates were prepared from aortic arches of 14–15 week old Fibulin-4+/+, Fibulin-4+/R and Fibulin-4R/R mice and protein amounts were determined (Pierce BCA protein assay kit, Thermo Scientific). Total TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 levels in CM samples, aortic arch lysates and plasma samples were determined by commercially available duo-sets (R&D Systems) using transient acidification as described before51.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test and unpaired student’s t-test were performed to analyse the specific sample groups for significant differences. The two-way ANOVA test was used to test significant differences between independent variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference between groups. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 and 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ramnath, N. W. M. et al. Fibulin-4 deficiency increases TGF-β signalling in aortic smooth muscle cells due to elevated TGF-β2 levels. Sci. Rep. 5, 16872; doi: 10.1038/srep16872 (2015).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. E. de Heer for providing the TGF-β neutralizing antibody and Dr. E. Leof for providing the p-SMAD-3 antibody. This work was supported by the ‘Lijf en Leven’ grant (2008) ‘early detection and diagnosis of aneurysms and heart valve abnormalities’ (JE and PH). LH and MP are supported by the Alpe d’HuZes/Bas Mulder award 2011 (UL 2011-5051).

Footnotes

Author Contributions N.R. and L.H. designed and performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the main manuscript. P.H. isolated vSMCs and contributed to the TGF-β reporter assays. L.R. contributed to the preparation of Fig. 5 with the Losartan treatment data. M.P. contributed to real time PCR. and ELISA data. M.V. contributed to immunohistochemical stainings. A.H.J.D. supervised losartan treatment experiments, R.K., P.D. and J.E. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Lindsay M. E. & Dietz H. C. Lessons on the pathogenesis of aneurysm from heritable conditions. Nature 473, 308–316, doi: nature1014510.1038/nature10145 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson C., Thelin S., Stahle E., Ekbom A. & Granath F. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation 114, 2611–2618, doi: CIRCULATIONAHA.106.63040010.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630400 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isselbacher E. M. Thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation 111, 816–828, doi: 10.1161/01.Cir.0000154569.08857.7a (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton T. E. et al. Phenotypic alteration of vascular smooth muscle cells precedes elastolysis in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Circ Res 88, 37–43 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamoto S. et al. TGFβR2 mutations alter smooth muscle cell phenotype and predispose to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiovasc Res 88, 520–529, doi: cvq23010.1093/cvr/cvq230 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz H. C. et al. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature 352, 337–339, doi: 10.1038/352337a0 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Mutations in myosin light chain kinase cause familial aortic dissections. Am J Hum Genet 87, 701–707, doi: S0002-9297(10)00522-710.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.006 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Laar I. M. et al. Mutations in SMAD3 cause a syndromic form of aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis. Nat Genet 43, 121–126, doi: ng.74410.1038/ng.744 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P. & Arthur H. M. Extracellular control of TGFβ signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 857–869, doi: nrm226210.1038/nrm2262 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys B. L. et al. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFβR1 or TGFβR2. Nat Genet 37, 275–281, doi: ng151110.1038/ng1511 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neptune E. R. et al. Dysregulation of TGF-β activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet 33, 407–411, doi: 10.1038/ng1116ng1116 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K. et al. Perturbations of vascular homeostasis and aortic valve abnormalities in fibulin-4 deficient mice. Circ Res 100, 738–746, doi: 01.RES.0000260181.19449.9510.1161/01.RES.0000260181.19449.95 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard M. et al. Altered TGFβ signaling and cardiovascular manifestations in patients with autosomal recessive cutis laxa type I caused by fibulin-4 deficiency. Eur J Hum Genet 18, 895–901, doi: ejhg20104510.1038/ejhg.2010.45 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard M. et al. Novel MYH11 and ACTA2 mutations reveal a role for enhanced TGFβ signaling in FTAAD. Int J Cardiol 165, 314–321, doi: S0167-5273(11)00920-X10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.079 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard M. et al. Thoracic aortic-aneurysm and dissection in association with significant mitral valve disease caused by mutations in TGFβ2. Int J Cardiol 165, 584–587, doi: S0167-5273(12)01135-710.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.029 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin J. R., Newman W., Beall L. D., Tucker A. & Madri J. Vascular cells respond differentially to transforming growth factors β 1 and β 2 in vitro. Am J Pathol 138, 37–51 (1991). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson L. K., Opitz J. M. & Zhou H. Lethal osteogenesis imperfecta-like condition with cutis laxa and arterial tortuosity in MZ twins due to a homozygous fibulin-4 mutation. Pediatr Dev Pathol 15, 137–141, doi: 10.2350/11-03-1010-CR.1 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. L. et al. Longer term survival of a child with autosomal recessive cutis laxa due to a mutation in FBLN4. Am J Med Genet A 161A, 1148–1153, doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35827 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappanayil M. et al. Characterization of a distinct lethal arteriopathy syndrome in twenty-two infants associated with an identical, novel mutation in FBLN4 gene, confirms fibulin-4 as a critical determinant of human vascular elastogenesis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7, 61, doi: 1750-1172-7-6110.1186/1750-1172-7-61 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. et al. Fibulin-4 deficiency results in ascending aortic aneurysms: a potential link between abnormal smooth muscle cell phenotype and aneurysm progression. Circ Res 106, 583–592, doi: CIRCRESAHA.109.20785210.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207852 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. et al. Fibulin-4 regulates expression of the tropoelastin gene and consequent elastic-fibre formation by human fibroblasts. Biochem J 423, 79–89, doi: BJ2009099310.1042/BJ20090993 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi M. et al. Fibulin-4 conducts proper elastogenesis via interaction with cross-linking enzyme lysyl oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 19029–19034, doi: 090826810610.1073/pnas.0908268106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisset A. C. et al. Intimal smooth muscle cells of porcine and human coronary artery express S100A4, a marker of the rhomboid phenotype in vitro. Circ Res 100, 1055–1062, doi: 01.RES.0000262654.84810.6c10.1161/01.RES.0000262654.84810.6c (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H. et al. Heterogeneity of smooth muscle cell populations cultured from pig coronary artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22, 1093–1099 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Chen H., Seth A. & McCulloch C. A. Mechanical force regulation of myofibroblast differentiation in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285, H1871–1881, doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00387.200300387.2003 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. et al. The autocrine production of transforming growth factor-β 1 during lymphocyte activation. A study with a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA. J Immunol 145, 1415–1422 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga C. L. et al. Anti-transforming growth factor (TGF)-β antibodies inhibit breast cancer cell tumorigenicity and increase mouse spleen natural killer cell activity. Implications for a possible role of tumor cell/host TGF-β interactions in human breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest 92, 2569–2576, doi: 10.1172/JCI116871 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S. et al. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF β-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J 17, 3091–3100, doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawinkels L. J. et al. Interaction with colon cancer cells hyperactivates TGF-β signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncogene 33, 97–107, doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.536 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habashi J. P. et al. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science 312, 117–121, doi: 312/5770/11710.1126/science.1124287 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moltzer E. et al. Impaired vascular contractility and aortic wall degeneration in fibulin-4 deficient mice: effect of angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blockade. PLoS One 6, e23411, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023411PONE-D-10-06286 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. et al. TGF-β through Smad3 signaling stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297, H540–549, doi: 91478.200710.1152/ajpheart.91478.2007 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull M. M. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359, 693–699, doi: 10.1038/359693a0 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V. et al. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-β 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet 11, 415–421, doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram U. et al. Double-outlet right ventricle and overriding tricuspid valve reflect disturbances of looping, myocardialization, endocardial cushion differentiation, and apoptosis in TGF-β(2)-knockout mice. Circulation 103, 2745–2752 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo E. M. et al. Angiotensin II-dependent TGF-β signaling contributes to Loeys-Dietz syndrome vascular pathogenesis. J Clin Invest 124, 448–460, doi: 6966610.1172/JCI69666 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battegay E. J., Raines E. W., Seifert R. A., Bowen-Pope D. F. & Ross R. TGF-β induces bimodal proliferation of connective tissue cells via complex control of an autocrine PDGF loop. Cell 63, 515–524, doi: 0092-8674(90)90448-N(1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen S. E. et al. Bidirectional effects of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) on colony-stimulating factor-induced human myelopoiesis in vitro: differential effects of distinct TGF-β isoforms. Blood 78, 2239–2247 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Casillas F., Wrana J. L. & Massague J. Betaglycan presents ligand to the TGF β signaling receptor. Cell 73, 1435–1444, doi: 0092-8674(93)90368-Z(1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee K. J., Wilkes D. C., Devereux R. B., Basson C. T. & Hatcher C. J. TGFβRIIb mutations trigger aortic aneurysm pathogenesis by altering transforming growth factor β2 signal transduction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 5, 621–629, doi: CIRCGENETICS.112.96406410.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.964064 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey T. A. et al. Decreased type II/type I TGF-β receptor ratio in cells derived from human atherosclerotic lesions. Conversion from an antiproliferative to profibrotic response to TGF-β1. J Clin Invest 96, 2667–2675, doi: 10.1172/JCI118333 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarakoon R., Overstreet J. M. & Higgins P. J. TGF-β signaling in tissue fibrosis: redox controls, target genes and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Signal 25, 264–268, doi: S0898-6568(12)00283-510.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.003 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchshofer R. & Tamm E. R. The role of TGF-β in the pathogenesis of primary open-angle glaucoma. Cell Tissue Res 347, 279–290 doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1274-7 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschinski F. et al. The antisense oligonucleotide trabedersen (AP 12009) for the targeted inhibition of TGF-β2. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 12, 2203–2213 doi: BSP/CPB/E-Pub/000238-12-16(2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawinkels L. J. & Ten Dijke P. Exploring anti-TGF-β therapies in cancer and fibrosis. Growth Factors 29, 140–152, doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595411 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke B. S. et al. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 358, 2787–2795, doi: 358/26/278710.1056/NEJMoa0706585 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S. Q. et al. Aortic remodeling after transverse aortic constriction in mice is attenuated with AT1 receptor blockade. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33, 2172–2179, doi: ATVBAHA.113.30162410.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301624 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massam-Wu T. et al. Assembly of fibrillin microfibrils governs extracellular deposition of latent TGF β. J Cell Sci 123, 3006–3018, doi: jcs.07343710.1242/jcs.073437 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawinkels L. J. et al. VEGF release by MMP-9 mediated heparan sulphate cleavage induces colorectal cancer angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer 44, 1904–1913 doi: S0959-8049(08)00456-510.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.031 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaijzel E. L. et al. Multimodality imaging reveals a gradual increase in matrix metalloproteinase activity at aneurysmal lesions in live fibulin-4 mice. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 3, 567–577, doi: CIRCIMAGING.109.93309310.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.933093 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawinkels L. J. et al. Active TGF-β1 correlates with myofibroblasts and malignancy in the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Cancer Sci 100, 663–670 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]