Abstract

Acupuncture and related therapies such as moxibustion and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation are often used to manage cancer-related symptoms, but their effectiveness and safety are controversial. We conducted this overview to summarise the evidence on acupuncture for palliative care of cancer. Our systematic review synthesised the results from clinical trials of patients with any type of cancer. The methodological quality of the 23 systematic reviews in this overview, assessed using the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews Instrument, was found to be satisfactory. There is evidence for the therapeutic effects of acupuncture for the management of cancer-related fatigue, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and leucopenia in patients with cancer. There is conflicting evidence regarding the treatment of cancer-related pain, hot flashes and hiccups, and improving patients’ quality of life. The available evidence is currently insufficient to support or refute the potential of acupuncture and related therapies in the management of xerostomia, dyspnea and lymphedema and in the improvement of psychological well-being. No serious adverse effects were reported in any study. Because acupuncture appears to be relatively safe, it could be considered as a complementary form of palliative care for cancer, especially for clinical problems for which conventional care options are limited.

Cancer is a major cause of disease burden worldwide. According to estimates from the International Agency for Research of Cancer1, the global adult population in 2012 included 14.1 million new cancer cases, 32.6 million existing cancer patients who had received a diagnosis within the previous 5 years and 8.2 million cancer deaths, accounting for 14.7% of all deaths. The incidence of cancer continues to increase. It is predicted that in 2035, approximately 24.0 million new cancer cases will be diagnosed and 14.6 million deaths will be attributable to cancer. This increasing cancer incidence and the continual improvement in cancer treatment will lead to an increase in the number of patients living with cancer. This will mandate progress in palliative care strategies for the control of symptoms related to cancer itself, as well as symptoms induced by cancer therapies.

According to the World Health Organisation2, palliative care is an approach that aims to improve the quality of life (QoL) of patients with life-threatening illnesses by relieving pain, distressing symptoms or other side effects related to treatment. Unlike the traditional concept of confining palliative care to the last 6 months of life, the current model recommended by the US National Comprehensive Cancer Network extends palliative care across the entire disease trajectory. Based on this concept, cancer palliative care focuses not only on the treatment of cancer-related symptoms such as pain, fatigue and insomnia, but also on relief of the side effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy such as nausea, vomiting, leukopenia and xerostomia3. This shift in the treatment model is partly related to the failure of aggressive care such as prolonged hospitalisation or intensive care unit admission to increase the life expectancy or improve the QoL of patients with incurable cancer4.

Acupuncture is one of the major treatment methods in traditional Chinese medicine. Related therapies such as moxibustion and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) are also often used separately or in combination with acupuncture. These therapies are widely used for supportive and palliative care of patients with cancer5. The existing systematic reviews (SRs) have summarised the evidence on the use of acupuncture and related therapies for the management of various cancer-related symptoms, including nausea and vomiting6,7, cancer-related pain (CRP)7,8 and fatigue7,9. These SRs have drawn contradictory conclusions. For example, Posadzki and colleagues9 reviewed seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies in the treatment of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and concluded that the risk of bias (RoB) amongst the included RCTs was too high for any reliable conclusions to be drawn. In contrast, another SR7 suggested that acupuncture is useful for the reduction of fatigue on the basis of one well-designed RCT. The disagreement amongst these four SRs could be attributed to differences in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategies, databases and search periods.

The contradictory results of these individual SRs make it difficult to draw conclusions on the potential effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies. An overview of the existing SRs is needed to provide an update on all synthesised clinical evidence on acupuncture and related therapies for palliative cancer care10. Although such an overview11 has already been conducted, its trustworthiness is limited for the following reasons: first, the search dates were limited to 2000 to 2011; hence, SRs published outside this time frame, including those published or updated since8,9,12,13,14, were not included. Second, the search strategy of the previous overview did not include Chinese-language databases, which may have led to the omission of clinical evidence15. Third, the methodological quality of the included SRs was not appraised with a validated instrument16, which limits the interpretation of their overall trustworthiness.

To overcome these limitations, we conducted an up-to-date overview of SRs to evaluate the methodological quality of SRs and meta-analyses of acupuncture for management of symptoms for palliative care of cancer and to describe the clinical evidence reported in these SRs and meta-analyses.

Results

SR search and screening results

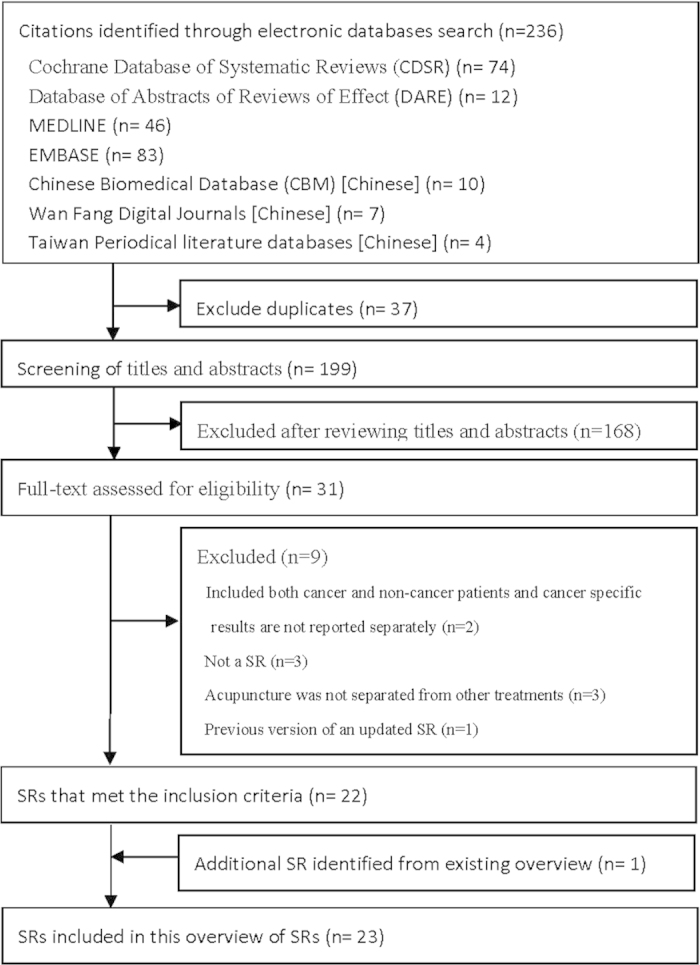

The database search strategies yielded 236 records, and 37 duplicates were identified and excluded. We excluded 168 citations after screening the titles and abstracts; thus, the full texts of the remaining 31 citations were retrieved for further assessment. Nine publications were excluded for the following reasons: two included patients with and without cancer and did not report the cancer-specific results separately, three were not SRs, three did not report the results of acupuncture and related therapies separately from those of other treatments and one was an early version of an updated SR. After this process, 22 SRs met the inclusion criteria. We further identified one additional SR by checking the reference list of a previous overview11. The other nine SRs included in that overview11 had already been identified by the literature search. Thus, a total of 23 SRs were included in this overview. Details of the literature search and selection can be found in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature selection on systematic reviews of acupuncture for cancer palliative care Keys: SR, systematic review.

Characteristics of included SRs

The 23 SRs were published between 2005 and 2014, and 14 (60.9%) of them were published after 2012. This overview includes 14 new SRs that were not included in the previous overview. Of the 22 SRs that provided a cut-off date on their literature search, 12 (55.0%) conducted their literature search after 2011 (i.e., after the publication of the previous overview11).

Overall, these SRs reported the results from 248 primary studies (median, 7) and 17,392 patients (median, 548). Three SRs (13.0%) were published in Chinese, and the rest were written in English. Three (13.0%) were Cochrane SRs. Thirteen (56.5%) SRs included only RCTs, and the rest included multiple study designs, including both clinical trials and observational studies. Seventeen (73.9%) of the SRs covered various types of cancer. Three SRs focused on patients with breast cancer6,7,17, and three other SRs summarised only evidence on patients with prostate cancer18, head and neck cancer19 and lung cancer20. Eleven SRs6,7,14,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 included any type of acupuncture or related therapy either with or without needle insertion. Nine SRs8,9,12,17,19,27,28,29,30 included only acupuncture with needle insertion and excluded other forms of related therapy, including TENS, laser acupuncture, acupressure and moxibustion. The remaining three SRs focused only on one particular form of acupuncture or related therapy, including TENS13, moxibustion31 and acupoint injection32.

Sixteen SRs summarised the evidence on a single outcome, including CRP8,13,21,22,26,27, fatigue9,24,31, hot flashes17,18, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)14,20, hiccups29 and irradiation-induced xerostomia19. The remaining seven SRs6,7,12,20,28,30,32 reported evidence on a wide range of outcomes in the palliative care of patients with cancer. The characteristics of these SRs can be found in Tables 1, 2, 3. Table 1 describes the SRs that included only RCTs on needle acupuncture. Table 2 reports the SRs that included RCTs that focused on acupuncture-related therapies. Table 3 highlights the SRs that included results from various study designs on both needle acupuncture and related therapies. The methodological quality of the included SRs as assessed by the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) is shown in Table 4 and Appendix 3. The corresponding results from these SRs can be found in Tables 5, 6, 7 and are supplemented with quantitative results reported in Appendix 4.

Table 1. Characteristics of included systematic reviews of RCT on needle acupuncture for cancer palliative care.

| Firstauthor andyear ofpublication | Includedstudydesign | Diagnosis | Searchperiod | Nature of acupuncture and relatedinterventions | Nature of controlinterventions | Outcomes | No. ofstudies(No. of patients)included | Meta-analysisconducted? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee, 2009b | OnlyRCT | Breastcancer | Aug.2008 | Acupuncture with needle insertion: needle acupuncture or electro-acupuncture. Related therapies including laser acupuncture and moxibustion were excluded. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included sham acupuncture, conventional care or relaxation. | Hot flushes. | 6 (202) | Yes |

| Peng, 2010 | OnlyRCT | Various | Jun.2008 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, or auricular acupuncture. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included conventional care, sham acupuncture or no treatment. | Cancer related pain. | 7 (634) | No |

| Pu, 2010 | OnlyRCT | Various | Jun.2009 | Needle acupuncture or electro-acupuncture. | Conventional care. | Nausea, vomiting and treatment related gastrointestinal adverse reaction. | 6 (461) | Yes |

| Choi, 2012a | OnlyRCT | Various | Apr.2011 | Needle acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, electro-acupuncture or “fire needle”. | Sham acupuncture or conventional care. | Cancer related pain, operation related pain. | 15 (1157) | Yes |

| Hurlow, 2012 | OnlyRCT | Various | Oct.2010 | Single or dual channel TENS | Placebo or placebo plus conventional care. | Cancer related pain. | 3 (88) | No |

| Paley, 2012 | OnlyRCT | Various | Jun.2012 | Penetrating acupuncture: including needle acupuncture or auricular acupuncture. | Sham acupuncture or conventional care. | Cancer related pain. | 3 (204) | No |

| Posadzki, 2013 | OnlyRCT | Various | Nov.2012 | Needle acupuncture plus electro-acupuncture; or needle acupuncture plus education. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included sham acupuncture or conventional care. | Cancer-related fatigue | 7 (548) | No |

| Zeng, 2013 | OnlyRCT | Various | May2013 | Needle acupuncture. Trials using acupuncture without needle insertion was excluded. | Sham acupuncture, conventional care, self- acupressure, no treatment or waiting list. | Cancer-related fatigue, quality of life, functional well-being | 7 (689) | Yes |

| Lian, 2014 | OnlyRCT | Various | Jun.2010 | Needle acupuncture or electro-acupuncture | Chemotherapy, conventional care or sham acupuncture | Vomiting, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, peripheral neuropathy; cancer pain, post-operative urinary retention, quality of life, vasomotor syndrome, recovery of gastrointestinal function. | 33 (2503) | No |

Keys: RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Table 2. Characteristics of included systematic reviews of RCT on acupuncture and related therapies for cancer palliative care.

| First authorand year ofpublication | Includedstudy design | Diagnosis | Searchperiod | Nature of acupunctureand relatedinterventions | Nature ofcontrolinterventions | Outcomes | No. of studies(No. of patients)included | Meta- analysisconducted? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen, 2013 | Only RCT | Lung cancer | Jun. 2013 | Needle acupuncture, acupoints injection, moxibustion, and applications of acupoint plaster or magnet. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included conventional care or CHM alone. | Various outcomes, including nausea and vomiting, tumor response, quality of life (measured by Karnofsky performance status & EORCT-QLQ-C30). | 31 (1758) | Yes |

| Lee, 2014 | Only RCT | Various | Apr. 2013 | Moxibustion (direct, indirect, heat-sensitive, moxa burner, or natural moxibustion). | Conventional care. | Cancer-related fatigue | 4 (374) | Yes |

| Cheon, 2014 | Only RCT | Various | Mar. 2013 | Acupoints injection with Chinese herbal extract solution; or with conventional medications. | Conventional care | Cancer related pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, lleus, hiccup, fever, quality of life and gastrointestinal symptoms | 22 (2459) | Yes |

| Ezzo, 2014 | Only RCT | Various, | Not reported | Needle acupuncture; acupressure; electro-acupuncture or TENS. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included conventional care, sham acupuncture, or conventional care plus sham acupuncture. | Chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting, or both. | 11 (1247) | Yes |

Keys: CHM: Chinese herbal medicine; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Table 3. Characteristics of included systematic reviews of various study design on acupuncture and related therapies for cancer palliative care.

| First authorand year ofpublication | Includedstudy design | Diagnosis | Searchperiod | Nature ofacupuncture andrelated interventions | Nature ofcontrolinterventions | Outcomes | No. of studies(No. of patients)included | Meta analysisconducted? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee, 2005 | Quasi-RCT | Various | Feb. 2004 | Needle acupuncture, ear acupuncture or electro-acupuncture. Other related therapies including laser acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion and TENS were not reviewed. | Conventional care or sham acupuncture. | Cancer related pain, operation related pain. | 7 (368) | No |

| Lu, 2007 | RCT or quasi-RCT | Various | 2004 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture with warming needle or acupuncture point injection with saline. | Chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy with vitamins or non-herbal supplements | Leukocytes level. | 11 (960) | Yes |

| Lee, 2009a | RCT, quasi-RCT, or observational studies | Prostate cancer | Dec. 2008 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture or auricular acupuncture. | Conventional care. | Hot flushes. | 6 (132) | No |

| Chao, 2009 | RCT, quasi-RCT, or case series study | Breast cancer | Oct. 2008 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, acupoints injection, self-acupressure or acupoints stimulation by devices. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included placebo, conventional care or no treatment. | Cancer therapy-related adverse events: hot flashes, nausea and vomiting, lymphedema, leukopenia. | 26 (1548) | No |

| Dos Santos, 2010 | RCT and case series | Breast cancer | Apr. 2009 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, acupuncture plus acupressure or auricular acupuncture. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included sham acupuncture, conventional care, waiting list or no treatment. | Cancer therapy-related adverse events: hot flashes, fatigue, pain, dyspnea, psychological well-being, lymphedema and vomiting. | 12 (612) | No |

| O’Sullivan, 2011 | RCTs and SR of RCTs | Head and neck cancer | 2010 | Needle acupuncture or electro-acupuncture. ‘Non-needling’ techniques including laser acupuncture, acupressure or acupuncture-like TENS were not considered. | Sham acupuncture or conventional care. | Irradiation-induced xerostomia | 3 (123) | No |

| Choi, 2012b | RCT and quasi-RCT | Various | Jul. 2011 | Needle acupuncture or electro-acupuncture. Other related therapies, including laser acupuncture, acupressure, auricular acupuncture using pressure device, acupoints injection and moxibustion were not considered. | Conventional care. | Cancer related hiccups. | 5 (296) | Yes |

| Finnegan-John, 2013 | RCT and quasi-RCT | Various | Jun. 2012 | Needle acupuncture or acupressure. | Sham acupuncture. | Cancer-related fatigue | 1 (35) | No |

| Zheng, 2014 | RCT and quasi-RCT | Various | 2013 | Needle acupuncture alone or needle acupuncture plus conventional care. | Conventional care alone. | Cancer related pain | 5 (395) | Yes |

| Frisk, 2014 | RCT and case series | Various | Oct. 2012 | Needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture or auricular acupuncture. | No restriction on type of control. Controls included conventional care, sham acupuncture or no treatment. | Hot flushes. | 17 (599) | No |

Keys: RCT, randomized controlled trial; SR, systematic review; TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Table 4. Methodological quality of included systematic reviews on acupuncture and related treatment for cancer palliative care.

| First author andpublication year | AMSTAR item |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Lee, 2005 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N | N |

| Lu, 2007 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Lee, 2009a | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Lee, 2009b | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Chao, 2009 | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Peng, 2010 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Dos Santos, 2010 | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Pu, 2010 | N | Y | Y | NR | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| O’Sullivan, 2010 | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Choi, 2012a | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Hurlow, 2012 | Y | NR | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Paley, 2012 | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Choi, 2012b | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Posadzki, 2013 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Zeng, 2013 | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Finnegan-John, 2013 | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | N |

| Chen, 2013 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Zheng, 2014 | N | Y | Y | NR | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Lee, 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Frisk, 2014 | N | NR | Y | N | N | N | N | N | NA | N | N |

| Cheon, 2014 | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Ezzo, 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Lian, 2014 | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | NA | N | N |

| # of Yes (%) | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.3) | 23 (100.0) | 13 (56.5) | 6 (26.1) | 12 (52.2) | 22 (95.6) | 18 (78.3) | 9 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Keys: N, no; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; Y, yes (SR fulfilling the criteria); # of Yes, number of yes; AMSTAR item: 1. Was an ‘a priori’ design provided? 2. Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? 3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? 4. Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? 5. Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? 6. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? 7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? 8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? 9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? 10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? 11. Was the conflict of interest included?

Table 5. Clinical evidence on the effectiveness of needle acupuncture on cancer palliative care related symptoms-evidence from SR of RCT.

| First author and publication year | Outcome assessment method | Main results | Notes on interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer related pain | |||

| Peng, 2010 | Total response rate or VAS | One RCT with low RoB reported that auricular acupuncture provides statistically significant relief on CRP when compared to sham acupuncture on Day 30 (p = 0.02) and Day 60 (p < 0.001). | This SR included the same low RoB RCT as Lee 2005 did. All the other six studies suggested positive effect of acupuncture in reducing CRP, although they are judged to have high RoB according to the Jadad scale. Five out of the six studies used total response rate as the primary outcome, which was not a validated outcome. |

| Choi, 2012a | Validated scales or VAS | Acupuncture showed positive add-on effect on response rate when compared to conventional care alone. No significant differences were found in the comparisons of acupuncture versus conventional care on response rate, or acupuncture versus sham acupuncture on pain score. | Considerable heterogeneity (I2 > = 67%) was observed in all three meta-analyses. One study was the same low RoB trial identified by Lee, 2005. All the other trials had poor reporting quality, and were judged as having unclear RoB. |

| Hurlow, 2012 | Validated scales | When comparing TENS with placebo, the results suggested that TENS may improve bone pain during movement. No superior effect in other pain outcomes when comparing TENS with placebo or sham TENS. | All the three trials had small sample sizes (n = 15, 24 and 49). All of them had either unclear RoB for allocation concealment or blinding of outcome assessment. |

| Paley, 2012 | Validated scales | One RCT with low RoB found that auricular acupuncture provided statistically significant relief on CRP when compared to sham acupuncture on Day 30 (p = 0.02) and Day 60 (p < 0.001). | Evidence from the only well designed RCT indicated effective ness of auricular acupuncture in relieving CRP. The other two studies were non-blinded and had incomplete outcome data. |

| Lian, 2014 | VAS or efficacy rate | Results from all six studies suggested that acupuncture is effective in reducing CRP. | RoB of the six studies were assessed with Jadad scale in this SR, of which all scored 2-3 out of a total of 5. However, rationale for supporting these ratings was not given. |

| Cancer related fatigue | |||

| Posadzki, 2013 | Validated scales for measuring fatigue | In the two trials with low RoB, one (n = 29) reported significant reduction in fatigue level at 2 weeks in the needle acupuncture group, as compared with the sham acupuncture group. Another study (n = 23) found no significant difference between the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups. | Acupuncture may be useful for reducing CRF but both trials were underpowered due to small sample size. |

| Zeng, 2013 | General CRF change score | All four sets of comparison favored acupuncture; however, only one comparison (acupuncture plus education versus conventional care) reached statistically significant difference on general CRF level. | All the comparisons had high heterogeneity (I2 values ranged from 65% to 94%, under random effect model.). Three trials had low RoB while the other four trials was judged to have high RoB. One had incomplete outcome data the other three lacked of allocation concealment and blinding. |

| Hot Flashes | |||

| Lee, 2009b | diary or logbooks | Results from meta-analysis suggested that acupuncture is effective in reducing hot flashes frequency during treatment when compared to sham acupuncture. However, such difference was not seen after the treatment. | These studies were judged to have low RoB using the Jadad scale, with scoring ranged from 4 to 5 out of 5. Allocation concealment procedures were properly implemented. |

| Nausea and vomiting | |||

| Pu, 2010 | Effective rate | Results from meta-analyses indicate that electro-acupuncture and conventional care had similar effect for reducing CINV. | Clinical evidence was from one single clinical trial with poor reporting quality. RoB of this trial was judged to be unclear. |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Zeng, 2013 | Change in general QoL scores | Acupuncture showed no favorable effect in improving QoL when compared to sham acupuncture at 10-week follow-up. | These three studies had low RoB. Considerable heterogeneity was found among the three studies (I2 = 92%, random effect model was used). |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Lian, 2014 | QoL assessment scales and various indexes | Both studies suggested that acupuncture plus conventional care can significantly improve quality of life in cancer patients compared to conventional care alone. | These two trials were judged to have 2 or 3 scores out of 5 in the Jadad scale. However, no rationale was provided on how these scorings were rated. |

| Other symptoms | |||

| Choi, 2012b | Response rates on reducing hiccup | Results from meta-analysis suggested a favorable effect of acupuncture on response rate for patients’ hiccup as compared to conventional care. | All the three studies had poor reporting quality on RoB related information, and were judged to have unclear RoB. |

Keys: CINV, chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting; CRF, cancer related fatigue; CRP, cancer related pain; MFI, multidimensional fatigue inventory; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RoB, risk of bias; SR, systematic review; TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VAS, Visual analog scale for pain.

Table 6. Clinical evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture related therapies on cancer palliative care related symptoms-evidence from SR of RCT.

| First author and publication year | Outcome assessment method | Main results | Notes on interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer related pain | |||

| Cheon, 2014 | Response rate | Controversial results were reported among the eight studies. As compared to conventional care, seven studies suggested benefit of acupoint injection in alleviating CRP. While the other one failed to find any positive effect from acupoint injection. | All included trials had high RoB for blinding, and unclear RoB on allocation concealment. All the included trails used response rate as the primary outcome, which was not a validated instrument. |

| Cancer related fatigue | |||

| Lee, 2014 | Response rate | Compared to conventional care alone, combination of moxibustion and conventional care showed favorable effect on response rate for CRF. | All the four trials had poor reporting quality. They were judged as having unclear RoB for both allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment. Considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 74%) was found in this random effect meta-analysis. |

| Nausea and vomiting | |||

| Chen, 2013 | Effective rate in reducing of nausea and vomiting (Grade II-IV) | The occurrence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting at Grade II-IV was remarkably reduced in the acupuncture plus conventional care when compared to conventional care alone. | The SR authors did not provide details on RoB among the included studies. |

| Cheon, 2014 | Response rate | Acupoints injection is suggested to be more effective than conventional care for CINV. | All the included trials had high RoB for blinding, and unclear RoB on allocation concealment. |

| Ezzo, 2014 | Proportion of patients with vomiting/nausea and Mean nausea/nausea severity | Acupuncture is effective in reducing the proportion of patients experiencing acute vomiting, but not in reducing the mean number of delayed vomiting episode, and in reducing severity of acute or delayed nausea. | The authors mentioned that only trials with low RoB were included, but there are no detailed assessment results on RoB for each of the trials. |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Chen, 2013 | QLQ-C30 total score | Acupuncture can improve QoL for lung cancer patients as compared to conventional care. | The SR authors did not provide details on RoB assessment for these two studies. |

| Cheon, 2014 | Responder rate (% in Karnofsky score) | Acupoints injection significantly improved QoL compared to conventional care (responder rate: 50% versus 25%, p < 0.01). | Evidence was reported from one single study (n = 108). Details on RoB of this study were not provided by the SR authors. |

| Other symptoms | |||

| Cheon, 2014 | Response rates on reducing hiccup | Both trials reported a higher responder rate in the acupoints injection group as compared to conventional care. Result from one study reached statistically significance while the other did not. | The two studies had unclear RoB for allocation concealment and high RoB for blinding. |

Keys: CINV, chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting; CRF, cancer related fatigue; CRP, cancer related pain; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RoB, risk of bias; SR, systematic review.

Table 7. Clinical evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies on cancer palliative care related symptoms-evidence from SR on various types of study design.

| First author and publication year | Outcome assessment method | Main results | Notes on interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer related pain | |||

| Lee, 2005 | VAS or patients’ verbal assessment | One RCT with low RoB found auricular acupuncture provides statistically significant relief on CRP when compared to sham acupuncture on Day 30 (p = 0.02) and Day 60 (p < 0.001). | Evidence from the only well designed RCT indicated the effective ness of auricular acupuncture on relieving CRP. The other studies were either non-blinded (n = 2) or designed as case series (n = 4). |

| Chao, 2009 | VAS | Controversial results were reported among the three studies. Significant positive effect from acupuncture was found in studies using VAS and number of analgesia applied (p < 0.05) as measures for CRP, but such result was not seem on Sedation score (p > 0.05). | RoB of the three studies were assessed with Jadad scale in this SR. No details on each RoB domain were provided to facilitate judgment on the overall trustworthy of evidence. |

| Dos Santos, 2010 | VAS, or validated scales | Evidence from both studies suggested that acupuncture is useful in reducing CRP. | One study was the same low RoB trial identified by Lee, 2005. The other study was judged to have high RoB for lack of allocation concealment and blinding. |

| Zheng, 2014 | Symptoms improvement rate | Insufficient evidence to judge the effectiveness of wrist ankle acupuncture in treating cancer pain. | All the included studies were judged to have high RoB for allocation concealment and blinding. However, no rationale supporting the RoB assessment results were provided. Symptom improvement rate was used as the primary outcome, which was not a validated instrument. |

| Cancer related fatigue | |||

| Dos Santos, 2010 | MFI | Needle acupuncture group had significantly higher improvement (36%) when compared to either acupressure group (19%) or sham acupressure (0.6%) group. | This trial was judged to have low RoB by the SR authors. |

| Finnegan-John, 2013 | MFI | This SR identified the same trial as Dos Santos, 2010. | See interpretation on results from Dos Santos 2010. |

| Hot Flashes | |||

| Lee, 2009a | Validated scales or patient diary | One trial with low RoB found both needle acupuncture and needle acupuncture + electro-acupuncture were effective for treating hot flush in prostate cancer patients when compared with baseline. No between group difference was found. | The only low RoB RCT compared needle acupuncture with electro-acupuncture; no other comparison was reported by the SR authors. The other five trials was judged to have high RoB with the Jadad scale, but no rationale were given on how the scoring was given. |

| Chao, 2009 | Self-administrated questionnaires | One trial with low RoB reported significant positive effect of acupuncture in reducing hot flushes when compared with sham acupuncture. However, other low RoB trial did not find any difference between the two groups. | The other five trials were judged as having high RoB using the Jadad scale; of which two of them were case series studies. |

| Dos Santos, 2010 | Daily diary/log records No. of hot flashes | Two trials with low RoB found that acupuncture was more effective in reducing hot flushes when compared to sham acupuncture, although the results from one of them did not reach statistical significance. | Current evidence from two trials with low RoB suggests that acupuncture may be useful in reducing hot flashes in breast cancer patients. However, two of the other three trials had high RoB. One did not implement no allocation concealment or blinding; and the other one was only a case series study. |

| Frisk, 2014 | Not reported | Results indicated that acupuncture treatment can reduce hot flashes in women with breast cancer and men with prostate cancer over a 3 months period. Nevertheless, it is not reported that how the outcome was measured. | The SR authors reported all the seven trial scored ≥3 score out of 5 in the Jadad scale, however, no rationale on the scorings were given. |

| Nausea and vomiting | |||

| Chao, 2009 | Validated scale | One trial with low RoB reported positive effect of electro-acupuncture in treating CINV when compared with sham acupuncture or conventional care. The effect persisted for five days, and it was not sustained from ninth days onward. | The remaining 10 trials were judged to have high RoB by the Jadad scale, of which two of them were case series studies. However, no rationale on the scorings was given. |

| Nausea and vomiting | |||

| Dos Santos, 2010 | Total no. of vomiting episodes and no. of vomiting free days | Patients in electro-acupuncture group had significantly greater proportion of nausea-and-vomiting-free days than patients in the other two groups during a 5-day treatment period; this benefit did not persist onward to the ninth days follow up. This SR identified the same low RoB trial as in Chao, 2009 above. | This evidence was from one clinical trial with low RoB for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment. However, RoB for blinding of participants and personnel were high. |

| Other symptoms | |||

| Lu, 2007 | Leucopenia (change in WBC count | Results from meta-analysis suggested that acupuncture plus conventional care was an effective option for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia as compared to conventional care alone. | All the included studies were judged to be of high RoB under the Jadad scale. However, no rationale was provided on how these scorings were rated. |

| Chao, 2009 | RILP | The authors reported that WBC level were increased but no further details were provided. | The result is reported from a small case series study. |

| Chao, 2009 & Dos Santos, 2010 | BCRL | In both SRs, acupuncture was found to be effective in treating BCRL. It is mentioned that the participants’ body circulation was enhanced, and sense of heaviness was reduced. Patients have also reported significant improvement on the range of movements, including shoulder flexion and abduction of the affected limbs. | The result is reported from a small case series study |

| Choi, 2012b | Response rates on reducing hiccup | Results from meta-analysis suggested a favorable effect of acupuncture on response rate for patients’ hiccup as compared to conventional care. | All the three studies had poor reporting quality on RoB related information, and were judged to have unclear RoB. |

| O’Sullivan, 2011 | Improvement on Xerostomia as measured by SFR | All three trials reported significant improvement on SFR when compared to baseline (p < 0.05), but no significant differences were seen between acupuncture and sham acupuncture group. | All the three studies used objective outcome measurements to reduce detection bias. One trial has low RoB for allocation concealment while the other two have unclear RoB. |

| Other symptoms | |||

| Dos Santos, 2010 | Rating scale on dyspnea. | In both groups, significantly improvement on dyspnea scores were observed immediately after treatment (p = 0.003). Dyspnea scores were slightly higher in acupuncture group than sham group, however, no significant differences were seen. | The trial was judged to have low RoB, but there is a lacking of blinding of personnel. |

Keys: BCRL, breast cancer-related lymphedema; CINV, chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting; CRP, cancer related pain; MFI, multidimensional fatigue inventory; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RILP, radiotherapy induced leukopenia; RoB, risk of bias; SFR, salivary flow rates; SR, systematic review; VAS, Visual analog scale for pain; WBC, white blood cell.

Methodological quality of included SRs

All of the SRs conducted a comprehensive literature search (AMSTAR Item 3). Twenty-two (95.7%) assessed the scientific quality of the included studies (AMSTAR Item 7). Only five (21.7%) provided an a priori design to the SRs (AMSTAR Item 1). Although all of the SRs provided references to the included studies, only six (26.1%) provided lists of both included and excluded studies (AMSTAR Item 5). None of the SRs stated any conflict of interest on the included studies as well as on the SR itself (AMSTAR Item 11). Only 13 SRs (56.5%) included conflict of interest of the SR itself (AMSTAR Item 11). Of the 11 SRs that conducted meta-analyses, eight (81.8%) used appropriate statistical methods to combine the study findings (AMSTAR Item 9), but none assessed the likelihood of publication bias (AMSTAR Item 10). The details can be found in Table 4 and Appendix 3.

Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies

Cancer-related pain

Ten SRs6,7,8,12,13,21,22,26,27,32 synthesised clinical evidence on the use of acupuncture and related therapies in the reduction of CRP, of which only two22,26 conducted a meta-analysis (Table 7, Appendix 4). Zheng and colleagues26 included five studies (395 patients) that evaluated the effectiveness of wrist-ankle acupuncture on the symptom improvement rate. Their results showed no statistical differences in the symptom improvement rate between wrist-ankle acupuncture plus conventional care and conventional care alone (pooled risk ratio [RR], 1.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92 to 1.36). Choi and colleagues22 summarised evidence from various forms of acupuncture and related therapies, and their synthesised results showed that acupuncture and related therapies plus conventional care had a slightly stronger effect in the reduction of CRP (pooled RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.64) than conventional care alone. However, no statistical differences were found in the response rates of acupuncture and related therapies and those of conventional analgesic treatment (pooled RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.28). No significant difference was seen in the pain score between acupuncture (including auricular acupuncture and electro-acupuncture) and sham acupuncture (pooled standard mean difference [SMD], –0.41; 95% CI, –1.39 to 0.49).

Meta-analysis was not conducted in the other SRs6,7,8,13,21,27,32 (Tables 5, 6, 7 and Appendix 4). Three SRs8,21,27 (Tables 5 and 7 and Appendix 4) identified one RCT with a low RoB and mentioned that auricular acupuncture provided statistically significant relief on CRP when compared with sham acupuncture.

Cancer-related fatigue

Five SRs7,9,24,28,31 summarised evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies in the treatment of CRF, and two conducted meta-analyses (Tables 5, 6, 7 and Appendix 4). Zeng and colleagues28 assessed the effectiveness of acupuncture for CRF in various types of cancer patients (Table 5 and Appendix 4). Four meta-analyses were conducted for different comparisons, and all results showed a reduction of CRF with acupuncture. However, only one meta-analysis showed that acupuncture plus education could significantly reduce CRF in cancer patients when compared to conventional care (two RCTs; pooled SMD, –2.12; 95% CI, –3.21 to –1.03). One of the pooled RCTs provided information on the net benefit of acupuncture. In this trial, acupuncture plus conventional care was compared with conventional care alone; the mean difference was –2.52 (95% CI, –2.85 to –2.19). However, the validity of these results was compromised because the two RCTs did not implement allocation concealment and blinding.

Another SR31 investigated the effects of moxibustion on CRF (Table 6 and Appendix 4). The pooled results demonstrated that moxibustion plus conventional care could significantly improve CRF over conventional care alone (pooled RR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.29 to 2.32), but it is uncertain whether the outcomes were assessed with validated scales. Readers should note that all four trials included in this meta-analysis had poor reporting quality, so their RoB was unclear.

Hot flashes

Five SRs6,7,17,18,25 summarised evidence on acupuncture and related therapies for the treatment of hot flashes in patients with breast cancer6,7,17, prostate cancer18, or both25 (Tables 5 and 7 and Appendix 4). Only one study17 conducted a meta-analysis to compare acupuncture with sham acupuncture (Table 5 and Appendix 4). The results favoured acupuncture in the reduction of the frequency of hot flashes during treatment (pooled weighted mean difference [WMD], 1.91; 95% CI, 0.10 to 3.71). However, this difference was attenuated after treatment (pooled WMD, 3.09; 95% CI, –0.04 to 6.23). In contrast, one SR28 investigated the long-term effects of acupuncture (3 to 21 months of follow-up) and concluded that its benefits could be sustained for at least 3 months in women with breast cancer and in men with prostate cancer (Table 5 and Appendix 4).

Nausea and vomiting

Six SRs6,7,14,20,30,32 synthesised evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies on CINV (Tables 5, 6, 7 and Appendix 4). Four14,20,30,32 SRs conducted meta-analyses. Two20,32 reported that the results of acupuncture and related therapies for CINV were better than those of the control group (no details on the control intervention were provided). Another SR14 found that acupuncture could reduce the proportion of patients who experienced acute vomiting but did not reduce the mean number of delayed vomiting episodes or the severity of acute or delayed nausea. The remaining SR30 suggested that acupuncture and conventional medications had similar effects in the reduction of CINV, but this conclusion was based on a single RCT with an unclear RoB.

Quality of life

Four SRs12,20,28,32 synthesised evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for improving cancer patients’ QoL (Tables 5, 6 and Appendix 4). Two SRs20,28 conducted meta-analyses; one20 reported that acupuncture improves QoL in patients with lung cancer when compared to conventional care alone (pooled SMD, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.90), but the other28 found no favourable effects of acupuncture when compared to sham acupuncture (pooled SMD, 0.99; 95% CI, –0.70 to 2.68). The results of the two SRs12,32 that narratively summarised the results of the included RCTs described the favourable effects of acupuncture and related therapies in improving QoL when compared with conventional care or chemotherapy alone. It should be highlighted that only one SR12 reported a low RoB for all included trials, and the other three SRs12,20,32 did not provide details on the RoB of the included studies.

Leucopenia

Two SRs6,23 summarised the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies in the reversal of cancer treatment–induced leucopenia (Table 7 and Appendix 4). One SR23 focused on chemotherapy-induced leucopenia, and the results of the meta-analysis demonstrated that acupuncture promoted an increase in the white blood cell count (pooled WMD, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.64 to 1.81). The other SR6 reported a positive effect on radiotherapy-induced leucopenia, but this conclusion was supported by only one small case series with seven patients.

Lymphedema

Two SRs6,7 reported the results from one case series study, which concluded that acupuncture was effective in reducing lymphedema related to breast cancer. It was mentioned that the patients experienced significant improvement in their range of movements for shoulder flexion and abduction of the affected limb. Attention should be paid to the lack of a control group and the small sample size (29 patients) in this study (Table 7 and Appendix 4).

Hiccups

Choi and colleagues29 reviewed the effectiveness of needle or electro-acupuncture in the relief of hiccups in cancer patients (Table 5 and Appendix 4). Their meta-analysis showed that acupuncture can significantly reduce hiccups (pooled RR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.26 to 2.78) when compared with conventional care alone. It should be noted that all three included studies had unclear RoB and that the reliability of the outcome measurement approaches were doubtful.

Xerostomia

An SR19 assessed the effectiveness of needle or electro-acupuncture for the treatment of irradiation-induced xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer (Table 7 and Appendix 4). All three trials reported a significant reduction in xerostomia compared to baseline salivary flow rates after acupuncture or sham acupuncture. There was no significant difference between the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups.

Dyspnea

Dos Santos and colleagues7 identified one RCT with a low RoB that evaluated the effects of acupuncture in the treatment of dyspnea in patients with breast cancer (Table 7 and Appendix 4). Patients in both the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups showed statistically significant improvement in their dyspnea scores immediately after treatment. Although the improvement was slightly greater in the acupuncture group, it was not significantly different from the sham acupuncture group.

Psychological well-being

The effect of acupuncture on psychological well-being was discussed in two SRs7,28; however, neither found any significant beneficial effect of acupuncture when compared to a control group.

Adverse effects of acupuncture and related therapies

Of the 23 SRs, six7,8,20,21,24,25 did not describe any information on adverse events, two23,29 reported that the included studies did not mention any adverse events and two22,30 mentioned that all of the included studies reported no adverse events. The remaining 13 SRs6,9,12,13,14,17,18,19,26,27,28,31,32 reported adverse events that were attributable to acupuncture and related therapies. A wide range of minor adverse events was reported, which including bleeding at the acupuncture site, skin irritation, discomfort, transient rash, electrical shock sensation and tingling. There were no reports of serious AE that required medical management.

Discussion

This updated overview of 23 SRs summarised the clinical evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture in palliative care for cancer from 248 primary studies that included 17,392 participants. The effects of acupuncture on 12 outcomes that are highly relevant to palliative care of cancer, including CRP, CRF, hot flashes, vomiting and nausea, QoL, leucopenia, lymphedema, hiccups, xerostomia, dyspnea, psychological well-being and adverse events, were synthesised. Compared to the previous overview11, we identified and reported results from 14 additional, updated SRs. The clinical evidence from this overview suggests that acupuncture and related therapies are likely to be effective in improving CRF, CINV and leucopenia. In the context of current best practice, acupuncture and related therapies may be considered as additional treatments to the guideline-recommended treatment with glucocorticoids, 5-HT3 antagonists and/or NK1R antagonists in patients with moderate or high risk of emesis33. For leucopenia, antibacterial and antifungal prophylaxis are currently not recommended for patients with solid tumors who are undergoing conventional chemotherapy34. Acupuncture and related therapies may serve as an alternative prophylaxis, with a therapeutic goal of reducing the duration of neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count of less than 1500 cells/μL) to less than 7 days. Finally, acupuncture and related therapies can be considered as an adjunct in patients who experience persistent CRF after they receive first-line treatment. Such application is of high clinical relevance because it is well acknowledged that management of CRF is often suboptimal35. Although one SR demonstrated the effectiveness of acupuncture in the management of chronic pain36, we identified conflicting results on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies in the management of CRP. Conflicting results were also found in the treatment of hot flashes and hiccups and in the improvement of QoL. No adequately powered, well-designed RCT has been performed to clarify the potential role of acupuncture and related therapies in the management of xerostomia, dyspnea, lymphedema and psychological well-being. Future trials should focus on these under-investigated areas.

Although the application of acupuncture and related therapies in the management of CRF, CINV and leucopenia is supported by results from RCTs, the reporting quality of these studies is often poor, which hindered us from assessing the RoB in these RCTs, and future confirmatory trials should adhere to CONSORT recommendations for reporting. Researchers should also adopt a comparative effectiveness approach and design trials that allow real-world evaluation of acupuncture and related therapies. Specifically, the combined effects of acupuncture and related therapies in addition to guideline-recommended conventional care (e.g., glucocorticoids, 5-HT3 antagonists and/or NK1R antagonists in CINV) should be compared with conventional care alone so that the additional benefits of acupuncture can be elucidated37. Although this approach can make the choice of control intervention more straightforward, the design of a treatment protocol for acupuncture and related therapies is more challenging because it includes a wide variety of techniques38. Different researchers may use different techniques, and in other cases the treatment protocol can be individualised according to Chinese medicine diagnostic principles. Such variation is reflected in the included SRs–many adopted a less-restrictive approach and embraced various techniques6,7,8,9,14,18,20,21,22,23,25, whereas others focused only on a single technique such as moxibustion31 and TENS13. As a result, the meta-analyses often pooled trials with highly heterogeneous acupuncture and control interventions14,23, which makes interpretation of their results very difficult. Network meta-analysis39 could be a solution that takes into account the heterogeneity amongst treatments in both groups. Unfortunately, the exact intervention protocols used in trials are often not reported31, which prevented us from performing such an analysis. Finally, the interpretability of the reported results is also limited because of the wide variations in the choice of outcome measures. For example, pain was measured with a visual analogue scale in some primary studies, but in others it was reported as a binary response rate22. Future trials should choose the most clinically relevant endpoint as the primary outcome40 and measure it using a validated method11 so as to ensure the utility of future clinical evidence41.

When deciding on the scope of this overview, we tried to balance the need to reduce heterogeneity at the intervention level on the one hand and the need to ensure appropriate reflection of real clinical practice on the other. Although focusing exclusively on needle acupuncture may facilitate understanding of the effects of a single style of acupuncture, failure to report results from other related therapies may also reduce the comprehensiveness of this overview42. From a pragmatic perspective, a combination of needle acupuncture and related therapies such as moxibustion43 or TENS44 is often used in everyday clinical practice. In addition to treatment heterogeneity, the inclusion criteria in the original study design amongst SRs also requires a balance between reporting only the best available evidence from RCTs and taking a more inclusive approach to ensure comprehensiveness. Although the RCT is the best study design to provide evidence on effectiveness, the results from studies with weaker designs may inform the planning of future RCTs45, of which both are valuable from research and clinical practice perspectives. To make this overview informative for clinicians and researchers, we set broad inclusion criteria so that all available evidence on needle acupuncture and related therapies was presented46,47, but the data are separated according to the type of treatment and study design.

The methodological quality of the SRs included in this overview was satisfactory. Good performance in the following areas was noted: conducting duplicate study selection and data extraction, implementing comprehensive literature search, assessing the scientific quality of included studies and appropriately incorporating scientific quality in the formulation of conclusions. At the same time, improvements should be made in the following areas.

(i) The provision of an a priori design for the SRs would reduce the potential bias from reviewers, increase the SR’s transparency and prevent duplicate work on the same topic10.

(ii) Listing both included and excluded studies would ensure comprehensive reporting of SRs and allow readers to examine the excluded studies if they had a different perspective on eligibility criteria10.

(iii) Assessing the publication bias of included studies would inform readers on whether the results were generated from an unbiased sample of related studies10.

(iv) Clarifying conflicts of interest is important because it is well known that financial support might introduce bias to the SR process48.

In conclusion, acupuncture and related therapies have demonstrated favourable therapeutic effects in the management of CRF, CINV and leucopenia in cancer patients. Conflicting evidence exists for the treatment of CRP, hot flashes and hiccups and in the improvement of QoL. The currently available evidence is insufficient to support or refute the potential of acupuncture and related therapies in the management of xerostomia, dyspnea and lymphedema and in the improvement of psychological well-being. No serious adverse effects were reported in the included studies, consistent with the results of previous SRs that concluded that acupuncture is a relatively safe treatment option49,50. Future comparative effectiveness research in this area should pay attention to:

(i) improving the reporting and methodological quality of trials;

(ii) developing an acupuncture treatment protocol using an expert consensus technique, taking into account regulatory requirements and the constraints of the practice setting;

(iii) describing the treatment protocol according to the STRICTA51 and TIDieR checklist52, so that the procedure can be replicated in other trials or be adopted into clinical practice if it is found to be effective; and

(iv) choosing guideline-recommended treatment for the control group and validating outcome measures.

Methods

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

The Cochrane handbook version 5.1.0.10 states that an SR should aim to ‘identify, appraise and synthesise all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question’. Following this definition, we judged a publication as an SR if it sought to answer an explicit clinical question by examining evidence from at least two electronic databases. In this overview, any SRs (including both Cochrane SRs and non-Cochrane SRs) that summarised clinical evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer were considered eligible. If an SR summarised evidence on multiple palliative care techniques, those that reported evidence on acupuncture and related therapies separately were also included.

Participants

To be eligible, the SRs had to include clinical trials that recruited patients with a diagnosis of any type of cancer who have received acupuncture and related therapies for supportive or palliative care.

Interventions & control treatments

Any form of acupuncture was considered in this overview. We included SRs that summarised evidence on invasive acupuncture (including needle acupuncture, electro-acupuncture and auricular acupuncture) and non-invasive techniques such as laser acupuncture or acupressure. We also included acupoint injection, moxibustion and TENS. For control treatments, we included SRs that summarised studies that included any type of intervention without acupuncture or the related treatments described above. These interventions included conventional treatment, behavioural therapy, Chinese herbal medicine treatment, sham acupuncture, addition to a waiting list or no treatment.

Outcomes of interest

We summarised all reported cancer-related or treatment-related outcomes in this overview to provide a comprehensive picture of the available clinical evidence on acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer.

Literature search

We searched four international databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect ) and three Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Databases, Wan Fang Digital Journals and Taiwan Periodical Literature Databases) from their inception through July 2014 to identify potential SRs. For MEDLINE and EMBASE, a specialised search filter for SR articles was used53,54. Comprehensive searches of each database with a full Boolean search strategy were conducted, and the details are reported in Appendix 1.

Literature selection, data extraction and methodological quality assessment

The citations retrieved from the databases were independently screened and assessed for eligibility by two researchers (XY, RH); disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. If a disagreement could not be resolved, a third reviewer (VC) was invited to make a judgment. For duplicate publications, the most updated version was selected.

The following data were extracted from each eligible SR: (i) basic characteristics, including eligibility criteria, designs of included studies, number of included studies, total number of patients and bibliographic information; (ii) details on patients, interventions, controls and outcomes; (iii) synthesised results, including pooled summary effects of each comparison for each outcome if meta-analysis were conducted.

The methodological quality of the included SRs was assessed with the validated Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR)55 instrument. A detailed operational guide for AMSTAR can be found in Appendix 2. Data extraction and methodological quality assessment were conducted independently by two researchers; disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. Any unresolved discrepancies were judged by a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

The clinical evidence reported in the included SRs was synthesised narratively under each outcome. The effects on dichotomous data were summarised with the pooled RR, which measures the risk of a certain outcome in the treatment group as compared to the risk in the control group across trials. The pooled SMD or WMD was used for continuous outcomes. The SMD was used if a variety of measurement methods were used for the same outcome, and the WMD was used when the outcome was measured with the same method. The protocol of this overview has been registered in PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/DisplayPDF.php?ID=CRD42014015576).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wu, X. et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer: overview of systematic reviews. Sci. Rep. 5, 16776; doi: 10.1038/srep16776 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Hospital Authority of Hong Kong (Reference number: 8110016609).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Study concept and design: V.C., E.H. and J.W. Acquisition of data: X.Y.W. and R.H. Analysis and interpretation of data: X.Y.W. and R.H. Drafting of the manuscript: X.Y.W and V.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: V.C., E.Z., B.N. and K.T. Administrative, technical, or material support: S.W. and J.W. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. (2012) Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx. (Accessed: 9th November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. (Accessed: 9th November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. H. et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 7, 436–473 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Too much treatment? Aggressive medical care can lead to more pain, with no gain. Consum Rep 73, 40–44 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. D., Dean-Clower E., Doherty-Gilman A. & Rosenthal D. S. The Value of Acupuncture in Cancer Care. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 22, 631–648, doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.04.005 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L. F. et al. The efficacy of acupoint stimulation for the management of therapy-related adverse events in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 118, 255–267, doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0533-8 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos-Santos S. et al. Acupuncture for Treating Common Side Effects Associated With Breast Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Medical Acupuncture 22, 81–97, doi: 10.1089/acu.2009.0730 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paley C. A., Johnson M. I., Tashani O. A. & Bagnall A. Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD007753, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007753.pub2 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadzki P. et al. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Support care cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 21, 2067–2073, doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1765-z (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. & Green S., Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. (2011) Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. (Accessed: 9th November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Towler P., Molassiotis A. & Brearley S. G. What is the evidence for the use of acupuncture as an intervention for symptom management in cancer supportive and palliative care: an integrative overview of reviews. Support care 21, 2913–2923, doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1882-8 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian W. L., Pan M. Q., Zhou D. H. & Zhang Z. J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for palliative care in cancer patients: A systematic review. Chin J Integr Med 20, 136–147, doi: 10.1007/s11655-013-1439-1 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlow A. et al. Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3, CD006276, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006276.pub3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzo J. et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD002285, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Y. et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of traditional chinese medicine must search chinese databases to reduce language bias. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013, 812179, doi: 10.1155/2013/812179 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 10 Questions to help you make sense of reviews. Available at: www.sph.nhs/sph-files/casp. (Accessed: 9th November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Kim K. H., Choi S. M. & Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115, 497–503, doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0230-z (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Kim K. H., Shin B. C., Choi S. M. & Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating hot flushes in men with prostate cancer: a systematic review. Support care 17, 763–770, doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0589-3 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan E. M. & Higginson I. J. Clinical effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in the treatment of irradiation-induced xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Acupunct Med 28, 191–199, doi: 10.1136/aim.2010.002733 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Y., Li S. G., Cho W. C. S. & Zhang Z. J. The role of acupoint stimulation as an adjunct therapy for lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complem Altern M 13, doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H., Peng H. D., Xu L. & Lao L. X. Efficacy of acupuncture in treatment of cancer pain: a systematic review Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine [Chinese] 8, 501–509, doi: 10.3736/jcim20100601 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi T. Y., Lee M. S., Kim T. H., Zaslawski C. & Ernst E. Acupuncture for the treatment of cancer pain: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Support care cancer 20, 1147–1158, doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1432-9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. et al. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia: exploratory meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Soc Integr Oncol 5, 1–10 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan-John J., Molassiotis A., Richardson A. & Ream E. A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther 12, 276–290, doi: 10.1177/1534735413485816 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisk J. W., Hammar M. L., Ingvar M. & Spetz Holm A. C. E. How long do the effects of acupuncture on hot flashes persist in cancer patients? Support care 22, 1409–1415, doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2126-2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Yu Y. H. & Fang F. F. Meta-Analysis on Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture of Cancerous Pain. Jouranl of Liaoning University of TCM [Chinese] 16, 152–155 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Schmidt K. & Ernst E. Acupuncture for the relief of cancer-related pain–A systematic review. Eur J Pain 9, 437–444, doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.10.004 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., Luo T., Finnegan-John J. & Cheng A. S. K. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther 13, 193–200, doi: 10.1177/1534735413510024 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi T. Y., Lee M. S. & Ernst E. Acupuncture for cancer patients suffering from hiccups: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 20, 447–455, doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.07.007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H. h., Yu T., Gao X. & Mao J. J. Systematic Evaluation on Clinical Therapetic Effect of Acupuncture for Treatmen of Gastrointestinal Untoward Reaction by Malignant Tumor Chemotherapy. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research [Chinese] 21, 1476–1480, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2010.06.087 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. et al. The effectiveness and safety of moxibustion for treating cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Support care cancer 22, 1429–1440, doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2161-z (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon S. et al. Pharmacopuncture for cancer care: A systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 1–14, doi: 10.1155/2014/804746 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch E. et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 29, 4189–4198, doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.34.4614 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bow E. Treatment and prevention of neutropenic fever syndromes in adult cancer patients at low risk for complications. (2014) Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-of-neutropenic-fever-syndromes-in-adult-cancer-patients-at-low-risk-for-complications. (Accessed: 9th November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Koornstra R. H. T., Peters M., Donofrio S., van den Borne B. & de Jong F. A. Management of fatigue in patients with cancer–A practical overview. Cancer Treat Rev 40, 791–799, doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.01.004 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers A. J. et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 172, 1444–1453, doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt C. et al. Effectiveness guidance document (EGD) for acupuncture research–a consensus document for conducting trials. BMC Complem Altern M 12, 148, doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-148 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. NIH Consensus Conference. Acupuncture. JAMA 280, 1518–1524, doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1518 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A., Higgins J. P. T., Geddes J. R. & Salanti G. Conceptual and Technical Challenges in Network Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 159, 130–137, doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00008 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargon E. et al. Choosing Important Health Outcomes for Comparative Effectiveness Research: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 9, e99111, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster W. J. Making the Best Match: Selecting Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials and Outcome Studies. Am J Occup Ther 67, 162–170, doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.006015 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon K. et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 350, h2147, doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos S. et al. Acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: A randomized controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol 41, 1056–1063, doi: d10.1080/00365520600580688 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Hirota S., Katsumi Y., Ochi H. & Kitakoji H. A pilot study on using acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to treat knee osteoarthritis (OA). Chin Med 3, 2, doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-3-2 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordzij M. et al. Sample size calculations: basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25, 1388–1393, doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp732 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidich A.B., Pilalas D., Contopoulos-Ioannidis D. G. & Ioannidis J. P. A. Most meta-analyses of drug interventions have narrow scopes and many focus on specific agents. J Clin Epidemiol 66, 371–378, doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.10.014 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J. P. A. & Karassa F. B. The need to consider the wider agenda in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: breadth, timing, and depth of the evidence. BMJ 341, c4875, doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4875 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yank V., Rennie D. & Bero L. A. Financial ties and concordance between results and conclusions in meta-analyses: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 335, 1202, doi: 10.1136/bmj.39376.447211.BE (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Shang H., Gao X. & Ernst E. Acupuncture-related adverse events: a systematic review of the Chinese literature. Bull World Health Organ 88, 915–921c, doi: 10.2471/blt.10.076737 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. et al. The Safety of Pediatric Acupuncture: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 128, e1575, doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1091 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prady S. L., Richmond S. J., Morton V. M. & MacPherson H. A Systematic Evaluation of the Impact of STRICTA and CONSORT Recommendations on Quality of Reporting for Acupuncture Trials. PLoS ONE 3, e1577, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001577 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T. C. et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348, g1687, doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montori V. M., Wilczynski N. L., Morgan D. & Haynes R. B. Optimal search strategies for retrieving systematic reviews from Medline: analytical survey. BMJ 330, 68, doi: 10.1136/bmj.38336.804167.47 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski N. L. & Haynes R. B. EMBASE search strategies achieved high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving methodologically sound systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 60, 29–33, doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.001 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B. et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7, 10, doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.