Abstract

We use template stripping to integrate metallic nanostructures onto flexible, stretchable, and rollable substrates. Using this approach, high-quality patterned metals that are replicated from reusable silicon templates can be directly transferred to polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates. First we produce stretchable gold nanohole arrays and show that their optical transmission spectra can be modulated by mechanical stretching. Next we fabricate stretchable arrays of gold pyramids and demonstrate a modulation of the wavelength of light resonantly scattered from the tip of the pyramid by stretching the underlying PDMS film. The use of a flexible transfer layer also enables template stripping using a cylindrical roller as a substrate. As an example, we demonstrate roller template stripping of metallic nanoholes, nanodisks, wires, and pyramids onto the cylindrical surface of a glass rod lens. These nonplanar metallic structures produced via template stripping with flexible and stretchable films can facilitate many applications in sensing, display, plasmonics, metasurfaces, and roll-to-roll fabrication.

Keywords: nanoplasmonics, template stripping, stretchable devices, nanohole array, pyramidal tips, metasurface, roller nanoimprint lithography, roll-to-roll fabrication

Metallic nanostructures such as nanoholes,1 nanoparticles,2−4 and sharp tips5 are key elements for plasmonics,6 metamaterials,7,8 and near-field optics.5 Advanced top-down fabrication methods can produce precision-patterned metallic nanostructures on solid substrates such as silicon wafers.9 Placing these metal nanostructures on stretchable substrates can add a new degree of freedom to plasmonic devices and metamaterials to mechanically tune their optical properties. These functional films can also wrap around nonplanar surfaces for applications such as strain sensors,10,11 touch panels,12 curved displays,13 and metasurfaces.14−16 To these ends, researchers have employed various methods such as transfer on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) films,17 stencil lithography,18 resist evaporation,19 transfer printing,20 and nanoskiving21 to demonstrate metal nanostructures on unconventional substrates.

In this work, we demonstrate the potential of template stripping to produce stretchable metallic films. Template stripping has emerged as a versatile technique to produce smooth patterned metals with high throughput for plasmonics, metamaterials, and near-field optics.22−29 Instead of directly patterning the metal films, here an inverse pattern is created in a reusable silicon template, replicated by a deposited metal film, and the patterned metal is removed from the silicon template. The use of crystalline silicon wafers for templates opens up many processing options such as plasma etching and crystal-orientation-dependent wet etching and enables films to be produced with much smoother surfaces than as-deposited metals. Previous work on template stripping demonstrated pattern transfers using optical adhesive, polyethylene films,27 or as free-standing metal foils after electroplating.24 Because this technique is based on transferring metals from a silicon wafer to a backing layer, it is possible to template-strip metals with stretchable films such as PDMS. Template stripping can produce planar films as well as 3D structures such as sharp metallic pyramids for imaging and spectroscopy applications.29

We report detailed methods to transfer patterned metal films from a silicon wafer to PDMS and show examples of mechanically tunable plasmonic resonances using periodic gold nanohole arrays and pyramidal tips. We also show that template stripping can be performed using a roller to transfer the patterned metals to cylindrical surfaces.

Results and Discussion

Previous work on stretchable plasmonic devices focused on changing the distance between metal nanoparticles on a PDMS surface. Here we template-strip continuous patterned metal films using a PDMS backing layer and mechanically modulate their optical transmission spectra. After characterization of planar structures, we extend our method to gold pyramids.

Fabrication and Characterization of Stretchable Gold Nanohole Arrays

Since the report of extraordinary optical transmission (EOT) in subwavelength hole arrays,1 nanohole arrays patterned in metals have become one of the most extensively studied plasmonic structures for fundamental optical physics30−33 as well as applications in spectroscopy,34−36 biosensing,37−39 and color filtering.40,41 High-throughput patterning of periodic nanohole arrays has been accomplished by techniques such as optical interference lithography,42,43 colloidal lithography,44 and template stripping.24,26 Here we perform template stripping of large-area gold nanohole arrays with stretchable PDMS films.

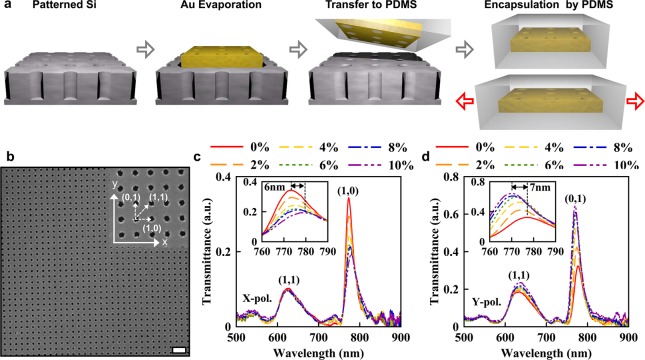

Our fabrication scheme is illustrated in Figure 1a. First, a Si template is produced by creating a 2D array of deep circular holes (180 nm diameter and 500 nm periodicity) in a Si wafer using nanoimprint lithography (Nanonex, NX-B200) and reactive ion etching (STS, 320PC). Then a 200 nm-thick Au film is deposited on the Si template through a shadow mask with an open area of 10 mm × 10 mm. During the metal evaporation process, nanoholes are formed in the deposited Au film.

Figure 1.

Stretchable gold nanohole arrays on a PDMS film. (a) Schematic of the fabrication process. (b) Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a gold nanohole array template-stripped using a PDMS backing layer. Scale bar: 1 μm. Inset: Zoomed-in SEM of the nanohole array (150 nm hole diameter and 500 nm period). (c) Measured optical transmission spectra from a nanohole array stretched along the x axis and illuminated with x-polarized light. The unstretched nanohole array exhibits two main resonance peaks: the (1,1) Bragg resonance at 635 nm and the (1,0) resonance at 777 nm. After stretching in the x direction, the (1,0) resonance in the x-polarization red-shifts while its intensity decreases. (d) Transmission spectra for the nanohole array on PDMS stretched along the x axis with illumination with y-polarized light. In this case, the (0,1) peak shifts to shorter wavelengths and its intensity increases.

Gold or silver films deposited on the oxidized surface of the Si template can readily be stripped using optical adhesive or sticky tape, but not with PDMS due to poor adhesion. Therefore, we use a self-assembled monolayer of 3-Mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane (MPT) as an adhesion layer between the metal film and PDMS. The use of a Ti or Cr adhesion layer is not desirable because they can increase unwanted plasmon damping in the nanohole arrays. MPT is vaporized and immobilized on the exposed Au surface of the nanohole array film and also on the Si surface that is not covered by the gold film. Then PDMS is spin-coated on the gold film over the Si template. The MPT layer formed on the gold surface acts as an adhesion promoter for PDMS while the MPT layer formed on the Si surface prevents PDMS from sticking there.45 After curing the PDMS at 60 °C for 12 h, the perforated Au film, which is now adhered to the PDMS substrate, is template-stripped. A scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a template-stripped periodic Au nanohole array (150 nm hole diameter) on a PDMS substrate is shown in Figure 1b. After template stripping, the top surface of the Au nanohole array is spin-coated again with PDMS for double-sided encapsulation during stretching experiments. This step also merges the EOT peaks from the top and bottom surfaces, simplifying the analysis of the EOT spectra.

The fabricated Au nanohole array is stretched using a home-built tool (Figure S1). Further information on the stretching method and tool can be found in the Supporting Information. The optical transmission spectra of the nanohole arrays were measured with incident light that is polarized parallel (Figure 1c) or orthogonal (Figure 1d) to the stretching direction (x-axis) with a gradually increasing strain level. Before stretching, the nanohole array exhibits two main EOT peaks at wavelengths of 635 nm (fwhm = 56 nm) and 790 nm (fwhm = 16 nm). These peaks are the (1,1) and (1,0) Bragg resonances, respectively, using the following equation to approximate the peak position:30

Here the integers (i, j) represent the Bragg resonance orders along the x- and y-axis, respectively, and εd and εm are the dielectric constants of the dielectric and metal, respectively.

As the nanohole array is stretched along the x-axis, parallel to the polarization of the incident beam, the corresponding (1,0) resonance peak red-shifts due to the increasing periodicity of the hole array (Figure 1c). As the circular holes are elongated in the x-direction with stretching, the electric field induced by surface charges becomes weaker and reduces the transmitted light intensity.46 When the polarization of input beam is perpendicular (i.e., along the y-axis) to the stretching direction (x-axis), opposite trends are observed; here the (0,1) resonance peak [before stretching, the (1,0) and (0,1) resonances are degenerate and in the same position] blue-shifts while the intensity of the peak increases (Figure 1d). The observed blue shift can be explained by the contraction of the film along the y-axis when it is stretched along the x-axis, a relationship that is determined by the Poisson’s ratios of the PDMS/Au composite film. The reduced array periodicity in the y-direction blue-shifts the peak wavelength. The peak intensity increases because of enhanced coupling of localized charges on the opposing edges of y-axial nanoholes.

The maximum spectral shift of the (1,0) or (0,1) resonance peak after stretching the PDMS substrate by 10% was about 7 nm and its measured line width (fwhm) was 20 nm. On the other hand, the (1,1) resonance peak does not move, as the change in length along the (1,1) direction is relatively small compared to the change in the (1,0) and (0,1) directions.

Our results indicate that the geometrical deformation of a nanohole array can induce polarization anisotropy in EOT. The changes in measured transmission spectra of nanohole arrays with stretching were compared with 3D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations (Fullwave, RSoft). The simulation results are in the Supporting Information (Figure S2). The measured spectral shift of 7 nm corresponds to only a 1% change in the length of the hole and periodicity while the entire substrate was stretched by 10%. The reason that the nanohole array only stretches by 1% is that cracks form in the surrounding substrate. Although the spectra were measured from a large 200 μm × 200 μm area of the nanohole array containing no cracks or wrinkles, the surrounding area of the full 8 mm × 8 mm template-stripped sample had random cracking which accounts for the increased stretching of the total film.

Fabrication and Characterization of Stretchable Gold Pyramids

Nonplanar 3D structures can also be transferred onto PDMS. For example, below we use our approach to fabricate arrays of Au pyramids. Because our pyramids were constructed from a gold layer that is intentionally thinner on one facet, SPPs can be launched with internal (i.e., backside) illumination, leading to nanofocusing of SPPs at the pyramid tip.47 The wavelength of the light scattered at the tip can then be modulated by regulating the angle of the pyramid facets with respect to the incident light via stretching.

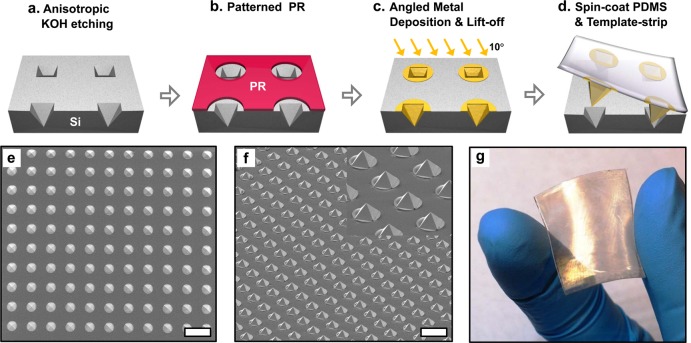

The fabrication process for asymmetric metallic pyramid arrays on PDMS substrates is depicted in Figure 2. First, an array of circular patterns is made in a silicon nitride (Si3N4) film on a Si wafer via photolithography (Karl Suss, MA-6) and dry etching (STS, 320PC). Second, anisotropic Si etching in a Potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution23,48,49 creates inverted pyramidal pits in the exposed regions and the silicon nitride mask is removed (Figure 2a). Next, circular photoresist patterns that reveal individual openings of pyramids are made to isolate each pyramid (Figure 2b). Then a 135 nm-thick Au film and a 10 nm-thick Ti adhesion layer are deposited at an incidence angle of 10° from normal by directional electron-beam evaporation (CHA, SEC 600), resulting in asymmetric Au pyramids with different Au thicknesses (45 and 120 nm) on opposing facets. After metal lift-off, an array of isolated, inverted Au pyramids is obtained (Figure 2c). Following O2 plasma exposure to break bridging oxygen bonds on the Ti surface, PDMS (10:1 weight ratio mixture of base resin and curing agent) is spin-coated onto the Si template with the Au pyramidal pit array. After curing for 12 h at 60 °C, the PDMS layer is peeled off of the Si template (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Fabrication of isolated gold pyramids template-stripped onto PDMS. (a) An array of pyramidal pits is formed by anisotropic etching in KOH through circular openings in a Si3N4 etch mask which is subsequently removed. (b) An array of 8 μm diameter circles in photoresist is patterned on top of the etched inverted pyramid array. (c) 135 nm of Au followed by 10 nm of Ti are deposited at 10° from normal using a directional e-beam evaporator. After lift-off, an array of disconnected, inverted Au pyramids is generated. (d) After oxygen plasma exposure to break bridging oxygen bonds, PDMS is spin-coated over the Au pyramidal pit array and cured at 60 °C for 12 h. The PDMS layer is then peeled off of the Si wafer. (e) Top-view and (f) bird’s eye view SEMs of a Au pyramid array on a PDMS substrate. Scale bar: (e), (f) 20 μm. (g) Photograph of 1 in. × 1 in. flexible PDMS film fully covered with gold pyramids.

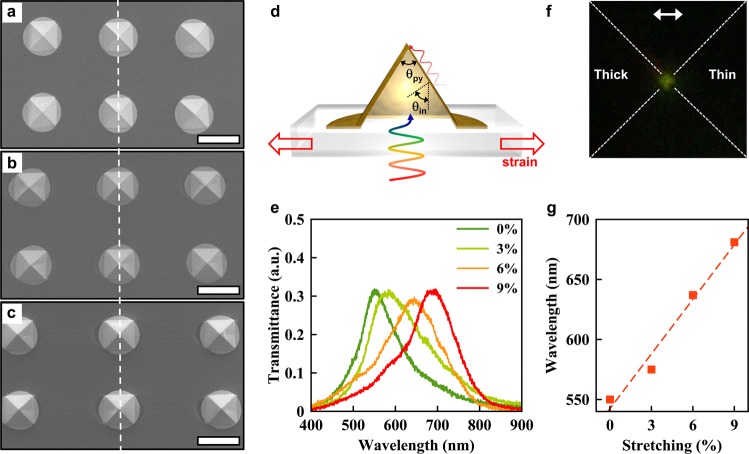

SEMs of stretchable gold pyramids on PDMS are shown in Figure 2e,f. The array of smooth and sharp Au pyramids can be fabricated over a large-area on PDMS as shown in Figure 2g. The base width of an unstretched pyramid as seen in Figure 3a is 7 μm. When the PDMS substrate is stretched by 10% and 20%, the base width of pyramid increases by about 5% and 10%, respectively, because the region consisting of only PDMS is stretched more than the area covered with gold.

Figure 3.

Tunable resonances of stretched metallic pyramids on PDMS. (a) The base width of the initial pyramid is 7 μm. (b) When the film is stretched to 10% past its initial length, the observed width increase of the pyramid’s base is about 5%. (c) When stretched to 20%, a 10% increase in the pyramid base width is observed. Scale bar: (a–c) 10 μm. (d) Cross-sectional schematic illustrating SPPs being generated on the thin Au face of the pyramid. (e) The measured spectra of scattered light at the pyramidal tip. As the applied force increases, the peak position of the spectra red-shifts from 545 to 682 nm. (f) CCD image of an asymmetric pyramidal tip that is internally illuminated with a white light source. The approximate position of the pyramidal tip is represented by dotted white lines. Green light (545 nm) is observed from the tip for no strain. (g) Spectral tuning of the light scattering at the tip by changing the incident angle via applied strain.

Angled electron-beam evaporation of Au simultaneously creates a large array of pyramids with two different thicknesses on opposing sides (45 and 120 nm). Verification of this through cross-sectional imaging has been shown in a previous paper.47 A 120 nm-thick Au film is optically opaque and hence blocks the incident light from the backside of the pyramid, whereas a 45 nm-thick Au film is optimal in exciting SPPs using a Kretschmann-like configuration. As illustrated in Figure 3d, stretching the Au pyramid changes the angle between the pyramid face and the incident light, which in turn changes the SPP coupling condition. Scattered light spectra from the pyramid tip and spectral shifts caused by stretching the pyramid are shown in Figure 3e. All spectra were measured with white light polarized parallel to the stretching direction. The resonance peak wavelength, initially located at 545 nm without an applied force, gradually increases up to 682 nm as the applied force increases. The decreased incident angle of light as the pyramid stretches with the applied force causes the wavelength shift.5 Assuming a conventional Kretschmann-like coupling mechanism,50 the incident light with θin reflects at the interface between Au and PDMS, resulting in an evanescent field with in-plane momentum kx = √ε sin θin propagating along the Au and PDMS interface, which excites SPPs at the interface between the Au and air. Thus, a reduced incident angle increases the wavelength of SPPs excited on the Au surface. The color green was observed at the tip when the resonance wavelength was located at 545 nm (Figure 3f) and the color red at 682 nm was seen for 9% strain. The wavelength of light scattered at the tip linearly increases with the mechanical strain, as shown in Figure 2g, demonstrating the tunability of the resonance by stretching a pyramid on the PDMS substrate. The pyramidal tips show a large resonance shift due to the strain, so large that the percentage change in wavelength is even larger than the percentage change in stretching. This high sensitivity to stretching likely originates from the high angular sensitivity of Kretschmann-like coupling of SPPs50 on the pyramidal facets.

Roller Template Stripping

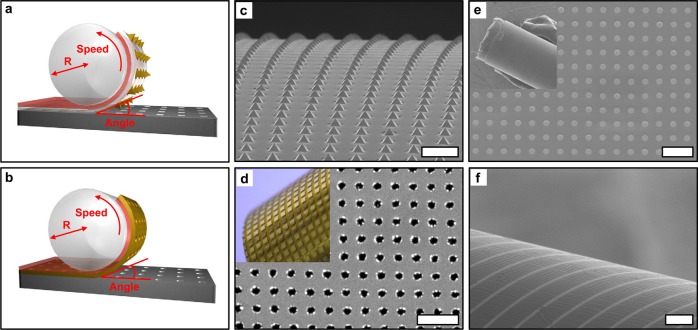

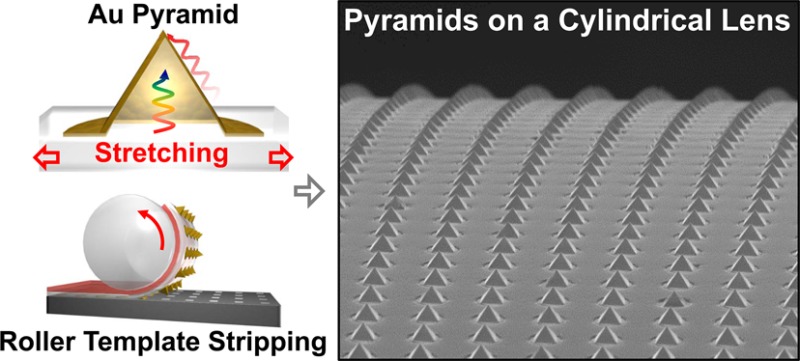

Metal structures on PDMS films can be placed conformally on nonplanar surfaces for various applications in optics, electronics, plasmonics, as well as metasurfaces. With template stripping, this transfer process can be made ever simpler and more controllable, because a cylindrical roller can be used to strip and transfer the patterned metal film onto a curved surface in a one-step rolling process, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a) Illustration of a roller template stripping process. Patterned metals on a silicon template are covered with a PDMS transfer layer (white) followed by a sticky double-sided Kapton tape (red). A glass rod lens is used as a rollable substrate to peel off patterned metals from the Si substrate and wrap them around its cylindrical surface. (b) Gold nanohole array films can be transferred using only a Kapton tape layer. (c) An array of 7 μm sized pyramids was rolled onto the curved surface of a glass rod (2 mm in diameter). Scale bar: 20 μm. (d) Nanohole patterns transferred onto a glass rod with a 10 mm diameter. The nanohole array with a 500 nm period and a 200 nm hole size was separated into 200 μm by 200 μm square patterns via standard photolithography before transferring to the glass rod. Scale bar: 1 μm. (e) An array of Au disks (200 nm diameter) was integrated onto the surface of a 1 mm radius glass rod using an optical epoxy transfer layer. Scale bar: 1 μm. (f) An array of parallel Au wires (5 μm width) was transferred onto a glass rod (2 mm diameter) with optical epoxy and a Kapton tape transfer layer. Scale bar: 30 μm.

During the peel-off process, a sticky transferring layer is attached to the supporting substrate, which in this case is the curved surface of glass rod lens. Here, a Kapton tape, a special type of polyimide, is used as the sticky transferring layer. By performing template stripping using a cylindrical roller, it is possible to control the bending angle of the flexible substrate (via the roller diameter) and the speed of template stripping (rolling speed) precisely. This technique can integrate both continuous and discontinuous patterned metal structures with curved surfaces in a facile and controlled manner. For 3D metallic patterns such as pyramidal structures, a supporting layer like PDMS is needed to fill the void inside the pyramid. The sticky transferring layer starts integrating the metallic pyramids onto the curved surface as it is rolled up. On the other hand, 2D metallic patterns like nanohole array can be directly transferred onto the roller using only a sticky transfer layer (Kapton tape) and no supporting layer (PDMS).

Our process, shown in Figure 4a,b, can be used to transfer various metallic structures onto rollable substrates. In Figure 4c, arrays of 7 μm sized pyramids are transferred onto the curved surface of a 2 mm diameter glass rod using both a support and transfer layer. Furthermore, Figure 4d shows the nanohole patterns transferred onto a 10 mm diameter glass rod. The nanohole array with 500 nm periodicity and 200 nm hole size was separated into 500 μm by 500 μm square patterns prior to template stripping by photolithography and wet etching. To reduce stress in the metal film and prevent cracking, the size of each nanohole array is limited to a few hundred microns.

For roller template stripping of submicron-size patterns from a Si substrate, optical adhesive (Norland Inc., NOA63) was used as a transfer layer instead of Kapton tape to enhance adhesion for small metal structures (Figure 4e,f). A thin layer of partially cured NOA63 is flexible and was wrapped around the glass rod lens. Using this approach, an array of gold disks (200 nm diameter) was successfully integrated on the glass surface of 1 mm radius using the optical epoxy supporting layer (Figure 4e). Metal wires (5 μm width) can also be transferred at various angles to the cylindrical axis of the rod lens (Figure 4f). In this case both the optical epoxy supporting and Kapton tape transferring layers were used. In this technique, both bending angle and strip speed can be used as process parameters. Moreover, the type of supporting layer could be selected according to the structure to be transferred. Such controllability can facilitate successful integration of smooth patterned metallic structures onto curved surfaces. For example, plasmonic nanostructures could readily be integrated onto the curved surface of an optical fiber or microsphere resonator for sensing applications. Since metallic apertures, nanoparticles, tips, and wire grids are basic building blocks for metasurfaces,15,16 our roller template stripping technique can provide a practical route for manufacturing large-area nonplanar metasurfaces. For applications requiring large-area patterning beyond the standard wafer scale, such as transparent electrodes,51 and flexible touch panels,12 roller template stripping may be combined with roll-to-roll processing schemes to mass-produce continuous patterned metal foils or polymer films embedded with high-quality patterned metals.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated a novel method of integrating plasmonic nanostructures such as Au nanohole arrays and pyramids with PDMS using template stripping allowing for mechanical tuning of the plasmonic properties of these nanostructures consisting of continuous metal films. Using our technique, it is possible to modulate the EOT spectra through nanohole arrays and the wavelength of light resonantly scattered at the tip of a gold pyramid. We took this approach one step further by demonstrating roller template stripping of metallic nanostructure onto cylindrical surface of a glass rod lens. This method can be combined with other cylindrical surfaces such as optical fibers, spherical surfaces such as microsphere resonators, or other structured surfaces to enable integration of plasmonic properties with light delivery mechanisms, and fabrication of optrodes, hyperlenses, nonplanar metamaterials,52,53 and cylindrical displays.13 Finally, nanopatterning on a cylindrical roller can be used for subsequent roll-to-roll nanoimprinting.54,55

Methods

Fabrication of Au Nanodisks and Wires

A standard Si wafer was spin-coated with thermal resist (Nanonex, NX-175) at 3500 rpm for 60 s. It was then imprinted using an 8 mm by 8 mm Si nanoimprint mold containing a post array with 200 nm diameters and a 500 nm period. The oxygen plasma was used to remove the residual thermal resist of the imprinted area. Micron-sized lines were patterned using SPR 179 positive photoresist, which was spin-coated on a bare Si wafer at 3000 r.p.m. for 60 s. A Cannon stepper was used for exposure at 250 mJ. After the developing process, residual photoresist in the exposed region was eliminated by 30 s of oxygen plasma (STS, 320PC). 100 nm of Au was deposited using an electron-beam evaporator (CHA, SEC600), followed by a lift-off process in acetone.

Far-Field Spectroscopic Measurements of Scattered Light from a Au Pyramidal Tip

It was measured on an inverted Nikon (Eclipse) microscope. The samples were placed inverted with pyramid tip facing down. White light was then illuminated through a condenser and polarizer and the light scattered at the tip was collected using a 100× objective (NA 0.9) and imaged using a low noise deep cooled CCD (Princeton Instruments, PIXIS) connected through a Newport spectrometer.

Optical Transmission Measurements from Au Nanohole Arrays Encapsulated in PDMS

It was characterized on an upright Nikon microscope. White light was illuminated via a condenser and collected through a 20× objective (NA 0.45). Spectral measurements were performed using a TE-cooled Ocean Optics QE65000.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research Young Investigator Program (S.-H.O.) and the National Science Foundation (CBET 1067681 and CMMI 1363334; to D.Y. and S.-H.O.). Device fabrication was performed at the Minnesota Nanofabrication Center at the University of Minnesota, which receives partial support from NSF through the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network. Electron microscopy was performed at the Characterization Facility at the University of Minnesota, which has received capital equipment from NSF MRSEC. D.J.N. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement Nr. 339905 (QuaDoPS Advanced Grant).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05279.

Experimental setup and computer simulations. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ebbesen T. W.; Lezec H. J.; Ghaemi H. F.; Thio T.; Wolff P. Extraordinary Optical Transmission Through Sub-Wavelength Hole Arrays. Nature 1998, 391, 667–669 10.1038/35570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maier S. A.; Kik P. G.; Atwater H. A.; Meltzer S.; Harel E.; Koel B. E.; Requicha A. A. G. Local Detection of Electromagnetic Energy Transport Below the Diffraction Limit in Metal Nanoparticle Plasmon Waveguides. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 229–232 10.1038/nmat852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Bjerneld E.; Käll M.; Borjesson L. Spectroscopy of Single Hemoglobin Molecules by Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 4357–4360 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halas N. J.; Lal S.; Chang W.-S.; Link S.; Nordlander P. Plasmons in Strongly Coupled Metallic Nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3913–3961 10.1021/cr200061k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny L.; Hecht B.. Principles of Nano-Optics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen T. W.; Genet C.; Bozhevolnyi S. I. Surface-Plasmon Circuitry. Phys. Today 2008, 61, 44–50 10.1063/1.2930735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaev V. M.; Cai W.; Chettiar U. K.; Yuan H.-K.; Sarychev A. K.; Drachev V. P.; Kildishev A. V. Negative Index of Refraction in Optical Metamaterials. Opt. Lett. 2005, 30, 3356–3358 10.1364/OL.30.003356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos S. P.; de Waele R.; Polman A.; Atwater H. A. A Single-Layer Wide-Angle Negative-Index Metamaterial at Visible Frequencies. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 407–412 10.1038/nmat2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist N. C.; Nagpal P.; McPeak K. M.; Norris D. J.; Oh S.-H. Engineering Metallic Nanostructures for Plasmonics and Nanophotonics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2012, 75, 036501. 10.1088/0034-4885/75/3/036501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amjadi M.; Pichitpajongkit A.; Lee S.; Ryu S.; Park I. Highly Stretchable and Sensitive Strain Sensor Based on Silver Nanowire–Elastomer Nanocomposite. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5154–5163 10.1021/nn501204t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L.; Zhang Y.; Zhang H.; Doshay S.; Xie X.; Luo H.; Shah D.; Shi Y.; Xu S.; Fang H.; et al. Optics and Nonlinear Buckling Mechanics in Large-Area, Highly Stretchable Arrays of Plasmonic Nanostructures. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 5968–5975 10.1021/acsnano.5b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Lee P.; Lee H.; Lee D.; Lee S. S.; Ko S. H. Very Long Ag Nanowire Synthesis and Its Application in a Highly Transparent, Conductive and Flexible Metal Electrode Touch Panel. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 6408–6414 10.1039/c2nr31254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H. O.; Tao A. R.; Schwartz A.; Gracias D. H.; Whitesides G. M. Fabrication of a Cylindrical Display by Patterned Assembly. Science 2002, 296, 323–325 10.1126/science.1069153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N.; Genevet P.; Kats M. A.; Aieta F.; Tetienne J.-P.; Capasso F.; Gaburro Z. Light Propagation with Phase Discontinuities: Generalized Laws of Reflection and Refraction. Science 2011, 334, 333–337 10.1126/science.1210713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kildishev A. V.; Boltasseva A.; Shalaev V. M. Planar Photonics with Metasurfaces. Science 2013, 339, 1232009. 10.1126/science.1232009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X.; Wong Z. J.; Mrejen M.; Wang Y.; Zhang X. An Ultrathin Invisibility Skin Cloak for Visible Light. Science 2015, 349, 1310–1314 10.1126/science.aac9411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryce I. M.; Aydin K.; Kelaita Y. A.; Briggs R. M.; Atwater H. A. Highly Strained Compliant Optical Metamaterials with Large Frequency Tunability. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4222–4227 10.1021/nl102684x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu S.; Huang M.; Artar A.; Yanik A. A.; Selvarasah S.; Dokmeci M. R.; Altug H. Flexible Plasmonics on Unconventional and Nonplanar Substrates. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4422–4430 10.1002/adma.201102430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Con C.; Cui B. Electron Beam Lithography on Irregular Surfaces Using an Evaporated Resist. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 3483–3489 10.1021/nn4064659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda D.; Shigeta K.; Gupta S.; Cain T.; Carlson A.; Mihi A.; Baca A. J.; Bogart G. R.; Braun P.; Rogers J. A. Large-Area Flexible 3D Optical Negative Index Metamaterial Formed by Nanotransfer Printing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 402–407 10.1038/nnano.2011.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Rioux R. M.; Whitesides G. M. Fabrication of Complex Metallic Nanostructures by Nanoskiving. ACS Nano 2007, 1, 215–227 10.1021/nn700172c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegner M.; Wagner P.; Semenza G. Ultralarge Atomically Flat Template-Stripped Au Surfaces for Scanning Probe Microscopy. Surf. Sci. 1993, 291, 39–46 10.1016/0039-6028(93)91474-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.-H.; Linn N. C.; Jiang P. Templated Fabrication of Periodic Metallic Nanopyramid Arrays. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 4551–4556 10.1021/cm0712319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal P.; Lindquist N. C.; Oh S.-H.; Norris D. J. Ultrasmooth Patterned Metals for Plasmonics and Metamaterials. Science 2009, 325, 594–597 10.1126/science.1174655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.-C.; Gao H.; Suh J. Y.; Zhou W.; Lee M. H.; Odom T. W. Enhanced Optical Transmission Mediated by Localized Plasmons in Anisotropic, Three-Dimensional Nanohole Arrays. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3173–3178 10.1021/nl102078j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im H.; Lee S. H.; Wittenberg N. J.; Johnson T. W.; Lindquist N. C.; Nagpal P.; Norris D. J.; Oh S.-H. Template-Stripped Smooth Ag Nanohole Arrays with Silica Shells for Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensing. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6244–6253 10.1021/nn202013v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Odom T. W. Tunable Subradiant Lattice Plasmons by Out-of-Plane Dipolar Interactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 423–427 10.1038/nnano.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-L.; Chen P.-W.; Wu S.-H.; Huang J.-B.; Yang S.-Y.; Wei P.-K. Enhancing Surface Plasmon Detection Using Template-Stripped Gold Nanoslit Arrays on Plastic Films. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2931–2939 10.1021/nn3001142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. W.; Lapin Z. J.; Beams R.; Lindquist N. C.; Rodrigo S. G.; Novotny L.; Oh S.-H. Highly Reproducible Near-Field Optical Imaging with Sub-20-Nm Resolution Based on Template-Stripped Gold Pyramids. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9168–9174 10.1021/nn303496g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Moreno L.; García-Vidal F. J.; Lezec H. J.; Pellerin K.; Thio T.; Pendry J. B.; Ebbesen T. W. Theory of Extraordinary Optical Transmission Through Subwavelength Hole Arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1114–1117 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.; Brolo A. G.; McKinnon A.; Rajora A.; Leathem B.; Kavanagh K. L. Strong Polarization in the Optical Transmission Through Elliptical Nanohole Arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 037401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.037401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Henzie J.; Odom T. W. Direct Evidence for Surface Plasmon-Mediated Enhanced Light Transmission Through Metallic Nanohole Arrays. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2104–2108 10.1021/nl061670r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Vidal F. J.; Martín-Moreno L.; Ebbesen T. W.; Kuipers L. Light Passing Through Subwavelength Apertures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 729–787 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brolo A. G.; Arctander E.; Gordon R.; Leathem B.; Kavanagh K. L. Nanohole-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 2015–2018 10.1021/nl048818w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison J. A.; O’Carroll D. M.; Schwartz T.; Genet C.; Ebbesen T. W. Absorption-Induced Transparency. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2085–2089 10.1002/anie.201006019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboktakin M.; Ye X.; Chettiar U. K.; Engheta N.; Murray C. B.; Kagan C. R. Plasmonic Enhancement of Nanophosphor Upconversion Luminescence in Au Nanohole Arrays. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 7186–7192 10.1021/nn402598e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolo A. G.; Gordon R.; Leathem B.; Kavanagh K. L. Surface Plasmon Sensor Based on the Enhanced Light Transmission Through Arrays of Nanoholes in Gold Films. Langmuir 2004, 20, 4813–4815 10.1021/la0493621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesuffleur A.; Im H.; Lindquist N. C.; Oh S.-H. Periodic Nanohole Arrays with Shape-Enhanced Plasmon Resonance as Real-Time Biosensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 243110. 10.1063/1.2747668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist N. C.; Lesuffleur A.; Im H.; Oh S.-H. Sub-Micron Resolution Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging Enabled by Nanohole Arrays with Surrounding Bragg Mirrors for Enhanced Sensitivity and Isolation. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 382–387 10.1039/B816735D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T.; Wu Y.-K.; Luo X.; Guo L. J. Plasmonic Nanoresonators for High-Resolution Colour Filtering and Spectral Imaging. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 59. 10.1038/ncomms1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos S. P.; Yokogawa S.; Atwater H. A. Color Imaging via Nearest Neighbor Hole Coupling in Plasmonic Color Filters Integrated Onto a Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor Image Sensor. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10038–10047 10.1021/nn403991d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzie J.; Lee M. H.; Odom T. W. Multiscale Patterning of Plasmonic Metamaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 549–554 10.1038/nnano.2007.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes J. W.; Ferreira J.; Santos M. J. L.; Cescato L.; Brolo A. G. Large-Area Fabrication of Periodic Arrays of Nanoholes in Metal Films and Their Application in Biosensing and Plasmonic-Enhanced Photovoltaics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 3918–3924 10.1002/adfm.201001262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Bantz K. C.; Lindquist N. C.; Oh S.-H.; Haynes C. L. Self-Assembled Plasmonic Nanohole Arrays. Langmuir 2009, 25, 13685–13693 10.1021/la9020614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. J.; Fosser K. A.; Nuzzo R. G. Fabrication of Stable Metallic Patterns Embedded in Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) and Model Applications in Non-Planar Electronic and Lab-on-a-Chip Device Patterning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005, 15, 557–566 10.1002/adfm.200400189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharian A. R.; Mansuripur M.; Moloney J. Transmission of Light Through Small Elliptical Apertures. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 2631–2648 10.1364/OPEX.12.002631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherukulappurath S.; Johnson T. W.; Lindquist N. C.; Oh S.-H. Template-Stripped Asymmetric Metallic Pyramids for Tunable Plasmonic Nanofocusing. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 5635–5641 10.1021/nl403306n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzie J.; Kwak E.-S.; Odom T. W. Mesoscale Metallic Pyramids with Nanoscale Tips. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1199–1202 10.1021/nl0506148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltasseva A.; Volkov V. S.; Nielsen R. B.; Moreno E.; Rodrigo S. G.; Bozhevolnyi S. I. Triangular Metal Wedges for Subwavelength Plasmon-Polariton Guiding at Telecom Wavelengths. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 5252–5260 10.1364/OE.16.005252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homola J.; Koudela I.; Yee S. S. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors Based on Diffraction Gratings and Prism Couplers: Sensitivity Comparison. Sens. Actuators, B 1999, 54, 16–24 10.1016/S0925-4005(98)00322-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.; Kim H. S.; Lee J.-Y.; Peumans P.; Cui Y. Scalable Coating and Properties of Transparent, Flexible, Silver Nanowire Electrodes. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2955–2963 10.1021/nn1005232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire M. C. K.; Pendry J. B.; Young I. R.; Larkman D. J.; Gilderdale D. J.; Hajnal J. V. Microstructured Magnetic Materials for RF Flux Guides in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Science 2001, 291, 849–851 10.1126/science.291.5505.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D.; Urzhumov Y.; Jung Y.; Kang G.; Baek S.; Choi M.; Park H.; Kim K.; Smith D. R. Broadband Electromagnetic Cloaking with Smart Metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1213. 10.1038/ncomms2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H.; Gilbertson A.; Chou S. Y. Roller Nanoimprint Lithography. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B: Microelectron. Process. Phenom. 1998, 16, 3926–3928 10.1116/1.590438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ok J. G.; Youn H. S.; Kwak M. K.; Lee K.-T.; Shin Y. J.; Guo L. J.; Greenwald A.; Liu Y. Continuous and Scalable Fabrication of Flexible Metamaterial Films via Roll-to-Roll Nanoimprint Process for Broadband Plasmonic Infrared Filters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 223102. 10.1063/1.4767995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.