Abstract

The colonization of the oral cavity is a prerequisite to the development of oropharyngeal candidiasis.

Aims:

The aims of this study were: to evaluate colonization and quantify Candida spp. in the oral cavity; to determine the predisposing factors for colonization; and to correlate the levels of CD4+ cells and viral load with the yeast count of colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) in HIV-positive individuals treated at a University Hospital. Saliva samples were collected from 147 HIV patients and were plated on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) and chromogenic agar, and incubated at 30 ºC for 72 h. Colonies with similar morphology in both media were counted and the result expressed in CFU/mL.

Results:

Of the 147 HIV patients, 89 had positive cultures for Candida spp., with a total of 111 isolates, of which C. albicans was the most frequent species (67.6%), and the mean of colonies counted was 8.8 × 10³ CFU/mL. The main predisposing factors for oral colonization by Candida spp. were the use of antibiotics and oral prostheses. The use of reverse transcriptase inhibitors appears to have a greater protective effect for colonization. A low CD4+ T lymphocyte count is associated with a higher density of yeast in the saliva of HIV patients.

Keywords: Candida, HIV; Candidiasis; Oral; Colonization

RESUMO

A colonização da cavidade oral pode ser considerada um pré-requisito para o desenvolvimento de candidíase orofaríngea. Os objetivos deste estudo foram: avaliar e quantificar espécies de Candida isoladas da cavidade oral, para determinar os fatores predisponentes para a colonização, e correlacionar os níveis de células CD4+ e carga viral em indivíduos HIV-positivos atendidos em um hospital universitário. Foram coletadas amostras de saliva de 147 pacientes portadores do HIV, as quais foram semeadas em Ágar Sabouraud Dextrose (ASD) e ágar cromogênico e incubadas a 30 °C por 72 horas. As colônias com morfologia semelhante em ambos os meios foram contadas e o resultado expresso em unidade formadora de colônias por mililitro (UFC/mL). Dos 147 pacientes HIV positivos, 89 apresentaram culturas positivas para Candida spp., totalizando 111 isolados, e C. albicans foi a espécie mais frequente (67,6%). A contagem média de colônias foi de 8.8 × 10³ UFC/mL. Os principais fatores predisponentes para colonização oral por Candida spp. foram a utilização de antibióticos e de próteses orais. O uso de antirretroviral da classe de inibidores da transcriptase reversa pareceu ter maior efeito protetor para a colonização. Baixa contagem de linfócitos T CD4+ está relacionada com maior densidade de leveduras na saliva de indivíduos HIV positivos.

INTRODUCTION

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is characterized by an impaired immune system, resulting in a continuing decrease in the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes. As a result of this, several opportunistic infections may be present in an individual infected with HIV, including cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystosis and candidiasis5 , 12 , 24.

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the most common fungal infection in individuals with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and 90% of them develop this infection at least once during the course of the disease3 , 21.

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the treatment of HIV infection causes a reduction in the occurrence of opportunistic infections. However, oropharyngeal candidiasis is still common among individuals with late diagnosis and those that do not respond successfully to treatment24 , 31. Currently, six classes of antiretroviral drugs are available in Brazil: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, fusion inhibitors, and co-receptors4.

Colonization of the oral cavity does not always culminate in oropharyngeal candidiasis. However, such colonization can be considered a prerequisite for the development of the disease. Before the onset of symptoms of infection, there is usually an intense colonization by Candida spp.8 , 33. Other factors that favor the colonization of the oral cavity by Candida species include: smoking, diabetes mellitus, oral prostheses, extreme age, antibiotics, decreased salivary flow, food habits, and nutritional status10 , 24 , 29.

In oral fungal microbiota, and in other mucosal microbiota of the body, Candida species have been observed to be prevalent, with C. albicans being the species most often isolated. Meanwhile, in recent years, there has been an increase in isolation of other species including C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. krusei and C. dubliniensis 19 , 24 , 31.

An important marker for the carrier state or infection is the count of colony-forming units (CFUs) of yeast in the oral cavity. Individuals who are only carriers of Candida spp. have a colony count of < 1000 CFU/mL of saliva, whereas individuals who have infection present with a colony count exceeding 4000 CFU/mL9 , 15.

The aims of this study were: to evaluate colonization and quantify Candida spp. in the oral cavity of HIV-positive individuals treated at a University Hospital; to determine the predisposing factors for colonization; and to investigate the correlation between the levels of CD4+ cells and viral load with the yeast count.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was classified as cross-sectional, which verified the presence of Candida spp. only at the time of saliva collection without monitoring the patient after sampling.

Research subjects and sample collection: saliva samples were collected from 147 seropositive HIV individuals in the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Uberlandia, Minas Gerais State, Brazil.

During routine consultations in the Infectious Diseases Clinic, patients received guidelines about the study and were invited to participate in the research. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Human Research of the Federal University of Uberlandia, protocol 368/11.

Demographic and clinical data for each individual research participant was obtained using a questionnaire, prior to collection of the saliva sample. Medical records were reviewed to obtain data such as age; form of HIV infection; time of diagnosis; use of antifungal agents and/or antibiotics within 30 days and/or seven days prior to collection of the saliva sample; antiretroviral therapy used; values of CD4+ cells; viral load (these values were measured up to two weeks prior to saliva collection); history of oral candidiasis; use of oral prostheses; and smoking status.

After that, patients were requested to collect approximately 2 mL of unstimulated saliva in sterilized tubs. When collecting the saliva sample, no patients had clinically active oral candidiasis.

Sample processing, quantification and identification of yeasts: the saliva sample was homogenized with sterile glass beads, and serial decimal dilutions were made (10- 1 to 10- 3) in sterile saline solution (0.9%). Then, aliquots of 10 µL of pure saliva and of the dilutions were added to plates containing Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) (Sigma, Rockville, USA) containing chloramphenicol (100 mg/L), and similarly to other plates containing Chromogenic Agar (Conda, Madrid, Spain). The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 72 h. Colonies with similar morphology in both media were counted and the result was expressed in colony-forming units per milliliter of saliva (CFU/mL).

Individual colonies from each sample were identified using the classical methodology and the Auxacolor2(r) system (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), and thereafter stored in BHI-glycerol at −20 ºC, and in sterile distilled water kept at room temperature22 , 30.

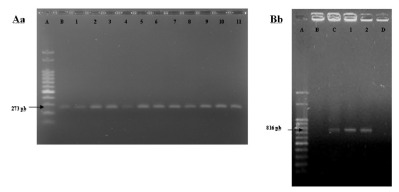

The samples identified as C. albicans were submitted to molecular testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for confirmation of the species or alternatively identification of C. dubliniensis. The DNA used in the PCR reactions was obtained according to the proposed by LUO & MITCHELL (2002) modified20. Three CFU previously grown in SDA for 24 h were transferred to 50 µL of sterile distilled water and 2 µL of this cellular suspension were directly used in PCR. Specific primers were used for C. albicans (forward: 3'TTT ATC AAC TTG TCA CAC CAG A5', reverse: 5'ATC CCG CCT TAC CAC TAC CG3') and C. dubliniensis: (forward: 3'AAA TGG GTT TGG TGC CAA ATT A5', reverse: 5'GTT GGC ATT GGC AAT AGC TCT A3')13.

Statistical analysis: patients included in the study were divided into two groups based on the results of the saliva sample culture: (1) colonized and (2) non-colonized. All patients who yielded at least one colony of Candida spp. in the culture were included in the first group (Group 1). Group 2 included all individuals with negative culture for Candida species.

Qualitative variables associated with either Group 1 or 2 were investigated using p-values and the odds ratio (OR)-values. For analysis of differences in qualitative variables between the two groups of patients, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Comparison of the average CFU/mL with the range of CD4+ T lymphocytes and of viral load was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Non-parametric tests were applied for the analysis of quantitative variables without normal probability distributions. All tests were applied using a significance level of 5%.

Fig. 1. - Agarose gel electrophoresis of specific primer for Candida albicans (Aa) and Candida dubliniensis (Bb). Aa: A) Molecular weight, B) C. albicans ATCC90028, 1-11) study samples. Bb: A) molecular weight, B) C. albicans ATCC90028, C) C. dubliniensis INCQS 40172, D) negative control, 1-2) study samples.

RESULTS

Of the 147 patients included in this study, 84 were male and 63 were female. Age ranged from 17-73, with a mean age of 44.7 and a median of 44. Of the 147 patients, 101 (68.7%) acquired HIV by heterosexual contact, 19 (12.9%) by homosexual contact, one (0.7 b%) congenitally, one (0.7%) by a work-related accident, one (0.7%) through a blood transfusion, and 24 patients (16.3%) were unable to inform how they were infected. The mean time for diagnosis of HIV infection was 8.4 years. Within this study group, 13 patients (8.8%) did not use any antiretroviral therapy at the time of collection of saliva sample; 68 (46.3%) used reverse transcriptase inhibitors, 61 (41.5%) used a protease inhibitor associated with a transcriptase inhibitor, and five (3.4%) combined the use of protease inhibitors with antiretroviral transcriptase and integrase inhibitors.

Candida spp. was isolated in 60.5% (89) of the patients, with a total of 111 isolates, and C. albicans was the most frequent species (67.6%). Candida non-Candida species accounted for 32.4% of the total isolates (Table 1). Among the 89 patients with a positive Candidaspecies culture, 69 (77.5%) were colonized by only one species of Candida, and 20 (22.5%) had a combination of two or more species (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution and frequency of association of Candida species isolated from the oral cavity of HIV patients treated at the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil, in t2012.

| Species | Frequency of isolates | Percentage (%) | Association of different species | Frequency of isolates | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 75 | 67.6 | C. albicans + C. parapsilosis | 6 | 30 |

| C. parapsilosis | 10 | 9.0 | C. albicans + C. tropicalis | 5 | 25 |

| C. tropicalis | 8 | 7.2 | C. albicans + C. glabrata | 2 | 10 |

| C. glabrata | 5 | 4.5 | C. albicans + C. krusei | 2 | 10 |

| C. krusei | 4 | 3.6 | C. albicans + C. kefyr | 1 | 5 |

| C. dubliniensis | 3 | 2.7 | C. dubliniensis + C. lusitaniae | 1 | 5 |

| C. kefyr | 2 | 1.8 | C. albicans + C. dubliniensis | 1 | 5 |

| C. famata | 1 | 0.9 | C. albicans + C. parapsilosis + C. tropicalis | 1 | 5 |

| C. guilliermondii | 1 | 0.9 | C. albicans + C. glabrata + C. tropicalis | 1 | 5 |

| C. lusitaniae | 1 | 0.9 | |||

| C. peliculosa | 1 | 0.9 | |||

| 111 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

The mean count of colonies per milliliter of saliva was 8.8 × 10³ CFU/mL, and the median was 8 × 10² CFU/mL (ranging from 10² to 5 × 105 CFU/mL).

Predisposing factors for colonization of the oral cavity by Candidaspecies are listed in Table 2. There was a significant statistical difference between colonized and non-colonized individuals with respect to the use of antibiotics (p = 0.0254, OR = 3.2) and the use of dental prostheses (p = 0.0173, OR = 2.46). However, use of HAART (p = 0.5671), use of antifungal agents (p = 0.7102), smoking (p = 0.3868), gender (p = 0.4215), age (p = 0.2529), CD4+ cell count (p = 0.5234), viral load (p = 0.2954), history of candidiasis (p = 0.8628), and time of HIV diagnosis (p = 0.2758) did not differ significantly between colonized and non-colonized patients.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics and rate of Candida oral colonization in 147 patients with HIV treated at the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 2012.

| Factors predisposing | Colonized (89) | Non-colonized (58) | p-value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of antibiotics | 24 (27%) | 6 (10.3%) | 0.0254 | 3.2000 |

| Use of antifungal | 5 (5.6%) | 5 (8.6%) | 0.7102 | 0.6310 |

| Smoker | 0.3868 | |||

| Yes | 27 (30.3%) | 13 (22.4%) | 1.5074 | |

| No | 62 (69.7%) | 45 (77.6%) | 0.6634 | |

| Use of dental prostheses | 0.0173 | |||

| Yes | 45 (50.6%) | 17 (29.3%) | 2.4666 | |

| No | 44 (49.4%) | 41 (70.7%) | 0.4054 | |

| Use of HAART | 80 (89.9%) | 54 (93.1%) | 0.5671 | 1.5146 |

| Sex | 0.4215 | |||

| Female | 41 (46%) | 22 (37.9%) | 1.3977 | |

| Male | 48 (54%) | 36 (62.1%) | 0.7154 | |

| Age | 45.6 | 43.5 | 0.2529 | |

| CD4+ | 544 ± 331 | 562 ± 319 | 0.5234 | |

| Viral load | 20215.7 ± 88698 | 5387.2 ± 21473.9 | 0.2954 | |

| Historical of oral candidiasis | ||||

| Yes | 27 (30.4%) | 16 (27.6%) | 0.8628 | 1.1431 |

| No | 62 (69.6%) | 42 (72.4%) | 0.8748 |

By analyzing the relationship between HAART (which includes different classes of antiretroviral drugs) and oral colonization by Candida spp., it was found that individuals who used a combination of reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors were more likely to be colonized than those using reverse transcriptase inhibitors alone (p = 0.0315). When comparing other therapeutic regimens among themselves and with those individuals who were not receiving HAART at the time of collection, no statistical differences were observed (p > 0.05). Compared with the other therapeutic schemes, and those who did not use HAART, no statistical difference was observed (p > 0.05).

The mean count of CD4+ cells was 551 cells/mm³, and the median was 557 cells/mm³ (range, 3-1619 cells/mm³). There were 25 (17%) patients who had < 200 CD4+ cells/mm³ at the time of collection of the saliva; 108 (73.4%) patients had an undetectable viral load (< 50 copies/mL), whereas 13 (8.8%) had a viral load of > 20,000 copies/mL.

Comparing the CD4+ cell count and the viral load of patients who had at least one isolate of Candida spp. in the oral cavity with those who had a negative culture, a very close p-value of 0.05 yielded in the range of 0-200 cells/mm³ in the case of CD4+ (p = 0.0546) (Table 3). The viral load did not differ significantly between colonized and non-colonized individuals (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of HIV-positive individuals colonized and not colonized by Candida spp. according to the CD4+ T lymphocyte cell count and viral load of patients treated at the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 2012.

| CD4 (cells/mm³) | Colonized (89) | Not colonized (58) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of individuals | Average (CD4) | No. of individuals | Average (CD4) | ||

| 0-200 | 17 (19.1%) | 123.7 | 8 (13.8%) | 70.3 | 0.0546 |

| 201-350 | 9 (10.1%) | 273.2 | 11 (19%) | 271.3 | 1.0000 |

| >350 | 63 (70.8%) | 694.6 | 39 (67.2%) | 743.5 | 0.1164 |

| Total | 89 (100%) | 544.1 | 58 (100%) | 561.1 | 0.5234 |

| Viral load (CFU/mL) | No. of individuals | Average (viral load) | No. of individuals | Average (viral load) | |

| <50 | 62 (69.6%) | - | 46 (79.3%) | - | 1.0000 |

| 51-20000 | 18 (20.2%) | 4317.8 | 8 (13.8%) | 6047.5 | 0.4899 |

| >20000 | 9 (10.2%) | 191274.8 | 4 (6.9%) | 66021.7 | 0.1474 |

Comparing the mean of the CFU/mL in saliva for the different ranges of CD4+ T lymphocytes, it was observed that those within the range of 0-200 CD4+ cells/mm³ tended to have a greater CFU/mL than those patients with CD4+ cells > 350 cells/mm³ (p = 0.0001) (Table 4). This statistical difference was not observed when comparing the mean CFU/mL between the different ranges of viral load (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between number of CD4+ cells and concentration of yeasts (CFU/mL) and viral load and concentration of yeasts in the saliva of HIV-positive patients treated at the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, in 2012.

| CD4+ (cells/mm³) | Colonized | CFU/mL (average) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-200a | 17 | 7.4 × 10³ | ab0.2631 |

| 201-350b | 9 | 5.5 × 10³ | ac0.0001 |

| >350c | 63 | 9.7 × 10³ | bc0.0948 |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | |||

| <50d | 62 | 9.8 ´ 10³ | de0.2259 |

| 51-20000e | 18 | 3.6 × 10³ | df:0.4549 |

| >20000f | 9 | 8.0 × 10³ | ef0.1270 |

| Total | 89 | 8.8 × 10³ |

Note: a, b, c: variation ranges of CD4 cells used as a reference at the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlândia, to begin, maintain or change antiretroviral therapy until the conclusion of this study ab, ac, bc: results from the statistical comparison between the mean of CFU/mL of three tracks CD4+ T lymphocytes. d, e, f: variation ranges of viral load. ab, ac, bc: result of statistical comparison between the mean CFU/mL of three tracks viral load.

DISCUSSION

Persistent colonization of the oral cavity by Candida spp. can be considered a predisposing factor for the development of oropharyngeal candidiasis11 , 16. In HIV patients, this has been given considerable attention due to the high incidence of oropharyngeal candidiasis and a high density of yeast in the oral cavity may be an important marker for disease progression1 , 3.

The frequency of HIV-positive individuals colonized by Candida spp. (as well as the species present) varies between different regions of the planet as a result of geographical, climatic and ethnic differences6 , 23. In this study, 60.5% of saliva samples were positive for Candida species. Studies show that in Brazil the rate of colonization has ranged from 58 to 62% in patients with HIV6 , 21. However, in countries such as Mexico, Turkey, Argentina and USA, higher rates have been reported11 , 24 , 27 , 28.

The predominant species found in this study was C. albicans (67.6%), corroborating the findings of similar studies in Sao Paulo, Argentina and Nigeria, which yielded a frequency of C. albicans of 51.5%, 58.9% and 45%, respectively21 , 24 , 26. Candida non-albicans species accounted for 32.4% of the total isolates: C. parapsilosis, (followed by C. tropicalis), was the most common. This frequency is higher than that reported by LI et al. in China23 (19.8%) and by WINGETER et al. in southern Brazil (7%)34. However, this increased percentage of Candida non-albicans species, besides having a major effect on clinical procedures, confirms a trend observed in other similar studies11 , 25.

Colonization by more than one Candida species has been reported previously11 , 23 , 24. In our study, 22.5% of patients were colonized by at least two species, and association was predominantly between C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (six of 20). Other studies have showed predominant association between C. albicans and C. glabrata 11 , 21 , 23 , 24.

Analysis of the concentration of yeast in saliva (8.8 ´ 103 CFU/mL) was higher than that previously observed in Sao Paulo (Brazil) and in the south of India (5.2 ´ 10² CFU/mL and 3 ´ 10² CFU/mL, respectively). However, the technique used for collecting that material was a swab of the oral cavity and rinse in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, respectively17 , 21. There is no consensus on the cut-off level of CFU/mL differentiating individuals colonized by yeast or having oropharyngeal candidiasis, yeast count > 4 × 10³ CFU/mL can be considered a sign of oral candidiasis9 , 15. The discrepancy in the average CFU/mL between studies may be explained by the different methodology used for collection of the saliva sample, as some techniques are more sensitive than others11.

Ways of reducing colonization may contribute to a decreased incidence and severity of oral candidiasis or even to a decreased risk of candidemia, hence the importance of identifying the individual's characteristics and habits that are associated with high oral cavity colonization by Candida spp., together with any potential modifications to these characteristics and habits. The use of antibiotics and dental prostheses were considered predisposing factors for colonization of the oral cavity by Candida species (and probably for the development of oral candidiasis). A similar study in Taiwan also observed the relationship between these two factors and oral colonization by Candida spp35. This relationship is explained by the fact that prolonged administration of antibiotics can cause an imbalance in the oral microbiota, thus allowing the proliferation of other microorganisms present there, including Candida species7. However, the use of an oral prosthesis is an important factor in colonization because of the trauma that the mucosa may suffer if it is not adjusted correctly, and/or due to poor hygiene, that also may occur14.

In the present study, the frequency of individuals colonized or not by Candida spp. was not related to the use of HAART therapy, confirming the results obtained in similar studies11 , 18 , 27. However, ARRIBAS et al. 2, LI et al.23 and YANG et al.36 observed a significant reduction in the rate of oral colonization in individuals who were using HAART. When we analyzed the relationship of a range of therapeutic regimens involving a number of classes of antiretroviral drugs, it was observed that the schema that included reverse transcriptase inhibitors combined with protease inhibitors was related to a greater frequency of colonized individuals compared with individuals whose HAART therapy included only a combination of reverse transcriptase inhibitors. YANG et al.36, observed a significant reduction in the rate of oral colonization, among those individuals included in their studies, that was related to the use of HAART therapy without, however, relating the class of drugs used.

A reduced frequency of individuals with HIV colonized by Candidaspp. has also been reported by WU et al.35, who demonstrated a reduction of oral colonization by Candida yeasts among individuals who used transcriptase inhibitors only. Possible mechanisms for the influence of HAART on oral colonization by Candida spp. are unknown. However, an explanation for the relationship between the use of protease inhibitors and an increased incidence of oral colonization by Candida species may be the greater immunological impairment and longer HIV infection period of individuals using protease inhibitors at the time of saliva sample collection, since the use of this class of antiretrovirals is only recommended when the combination of other classes of antiretrovirals has been ineffective in combating viral replication and, consequently, controlling HIV infection. Nevertheless, other studies may seek to confirm these findings, and thus contribute to elucidating the possible mechanisms that interfere with the proliferation of microorganisms and their adherence to the surface of the oral cavity.

Previous studies have sought to investigate the relationship between oral cavity colonization by Candida species with counts of CD4+ cells and viral load21 , 24 , 27.

When comparing the load of yeast present in the saliva of individuals colonized by Candida spp. with CD4+ T lymphocyte count and viral load, it was observed that patients with a lower count of CD4+ cells showed a higher CFU/mL of saliva. This suggests that a low CD4+ cell count may be associated with a higher number of yeast in the saliva of individuals with HIV. This relationship may be explained by the hypothesis that HIV infection may not only compromise the oral mucosal immunity but also stimulate the expression of virulence factors in the yeasts, since it has been observed, in vitro, that HIV stimulates the secretion of a proteolitic enzyme by C. albicans 32. However, when the same comparison was made in relation to the viral load of the subjects studied, this was not found to have a statistically significant difference, maybe because the number of subjects studied was insufficient to demonstrate the relationship. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature that have set out to examine the relationship of the concentration of yeasts in saliva to the CD4+ cell count and the viral load.

In conclusion, it was observed that despite C. albicans being the most frequent species, the Candida non-albicans species represented a significant percentage of isolates. In addition, the yeast count in the saliva of patients was greater than that observed in previous studies. The use of antibiotics and oral prostheses are directly related to oral colonization by Candida spp. However, the use of HAART had no statistically significant influence in reducing the colonization of the site in question, but use of the antiretroviral class of reverse transcriptase inhibitors alone appears to have a greater protective effect against colonization. Finally, a low CD4+ T lymphocyte count seemed to be associated with a higher number of yeast being present in the saliva of HIV patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) for the scholarship for R.P. Menezes. Thanks are given to the students Bruna Nogueira da Silva and Thais Chimatti Felix for helping with the collection of saliva samples and identification of the isolates, and to Rodrigo Augusto Machado de Moraes for the revision of the text. The authors would also like to thank the INCQS (Instituto Nacional de Controle de Qualidade em Saúde) for providing the reference strains included in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Abeid HM, Abu-Elteen KH, Elkarmi AZ, Hamad MA. Isolation and characterization ofCandida spp. in Jordanian cancer patients: prevalence, pathogenic determinants, and antifungal sensitivity. . Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arribas JR, Hernández-Albujar S, González-García JJ, Peña JM, Gonzalez A, Cañedo T. Impact of protease inhibitor therapy on HIV-related oropharyngeal candidiasis. AIDS. 2000;14:979–985. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005260-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badiee P, Alborzi A, Davarpanah MA, Shakiba E. Distributions and antifungal susceptibility ofCandida species from mucosal sites in HIV positive patients. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13:282–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais . Antirretrovirais utilizados. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2013. http://www.aids.gov.br/pagina/quais-sao-os-antirretrovirais [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks GF, Carroll KC, Butel JS, Morse SA, Mietzner TA.AIDS and lentivirusWeitz M, Lebowitz H.Medical microbiology thNew York: McGraw-Hill; 2010609–622. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campisi G, Pizzo G, Milici ME, Mancuso S, Margiotta V. Candidal carriage in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:281–286. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.120804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cisterna R, Ezpeleta G, Telleria O, Spanish Candidemia Surveillance Group. Nationwide sentinel surveillance of bloodstreamCandidainfections in 40 tertiary care hospitals in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4200–4206. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00920-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Collins CD, Cookinham S, Smith J. Management of oropharyngeal candidiasis with localized oral miconazole therapy: efficacy, safety, and patient acceptability. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:369–374. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S14047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Costa KR, Ferreira JC, Komesu MC, Candido RC. Candida albicansandCandida tropicalisin oral candidosis: quantitative analysis, exoenzyme activity, and antifungal drug sensitivity. Mycopathologia. 2009;167:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellepola AN, Khan ZU, Joseph B, Chandy R, Philip L. Prevalence ofCandida dubliniensisamong oralCandidaisolates in patients attending the Kuwait University Dental Clinic. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:271–276. doi: 10.1159/000323440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erköse G, Erturan Z. OralCandida colonization of human immunodeficiency virus infected subjects in Turkey and its relation with viral load and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. Mycoses. 2007;50:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esebelahie NO, Enweani IB, Omoregie R. Candidacolonisation in asymptomatic HIV patients attending a tertiary hospital in Benin City, Nigeria. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:20322–20322. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v8i0.20322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estrada-Barraza D, Dávalos-Martínez A, Flores-Padilla L, Mendoza-De Elias R, Sánchez-Vargas LO. Comparación entre métodos convencionales, ChromAgarCandiday el método de la PCR para la identificación de especies deCandidaen aislamientos clínicos. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2011;28:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falcão AFP, Santos LB, Sampaio NM. Candidíase associada a próteses dentárias. Sitientibus(Feira de Santana) 2004;30:135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farah CS, Ashman RB, Challacombe SJ. Oral candidoses. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:553–562. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong IW, Laurel M, Burford-Mason A. Asymptomatic oral carriage ofCandida albicansin patients with HIV infection. Clin Invest Med. 1997;20:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girish Kumar CP, Menon T, Rajasekaran S, Sekar B, Prabu D. Carriage ofCandida species in oral cavities of HIV infected patients in South India. Mycoses. 2009;52:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottfredsson M, Cox GM, Indridason OS, De Almeida GM, Heald AE, Perfect JR. Association of plasma levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and oropharyngealCandidacolonization. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:534–537. doi: 10.1086/314887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutiérrez J, Morales P, Gonzáles MA, Quindós G. Candida dubliniensis, a new fungal pathogen. J Basic Microbiol. 2002;42:207–227. doi: 10.1002/1521-4028(200206)42:3<207::AID-JOBM207>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo G, Mitchell TG. Rapid identification of pathogenic fungi directly from cultures by using multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2860–2865. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2860-2865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junqueira JC, Vilela SF, Rossoni RD, Barbosa JO, Costa AC, Rasteiro VM. Oral colonization by yeasts in HIV-positive patients in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2012;54:17–24. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652012000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacaz CS, Porto E, Martins JEC. Tratado de micologia médica. São Paulo: Sarvier; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YY, Chen WY, Li X, Li HB, Wang L, He L. Asymptomatic oral yeast carriage and antifungal susceptibility profile of HIV-infected patients in Kunming, Yunnan Province of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:13–46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luque AG, Biasoli MS, Tosello ME, Binolfi A, Lupo S, Magaró HM. Oral yeast carriage in HIV-infected and non-infected populations in Rosario, Argentina. Mycoses. 2008;52:53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macêdo DPC, Farias AMA, Lima RG, Neto, Silva VKA, Leal AFG, Neves RP. Infecções oportunistas por leveduras e perfil enzimático dos agentes etiológicos. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42:188–191. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822009000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nweze EI, Ogbonnaya UL. OralCandidaisolates among HIV-infected subjects in Nigeria. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel PK, Erlandsen JE, Kirkpatrick WR, Berg D, Westbrook SD, Louden C. The changing epidemiology of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with HIV/AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:262471–262471. doi: 10.1155/2012/262471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Vargas LO, Ortiz-López NG, Villar M, Moragues MD, Aguirre JM, Cashat-Cruz M. OralCandidaisolates colonizing or infecting human immunodeficiency virus-infected and healthy persons in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4159–4162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4159-4162.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schelenz S, Abdallah S, Gray G, Stubbings H, Gow I, Baker P. Epidemiology of oral yeast colonization and infection in patients with hematological malignancies, head neck and solid tumors. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva JO, Costa PP, Reche SHC. Manutenção de leveduras por congelamento a -20°C. Rev Bras Anal Clín. 2008;40:73–74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan DJ, Westerneng TJ, Haynes KA, Bennett DE, Coleman DC. Candida dubliniensissp. nov: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV infected individuals. . Microbiology. 1995;141:1507–1521. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tosun I, Aydin F, Kaklikkaya N, Erturk M. Induction of secretory aspartyl proteinase ofCandida albicansby HIV-1 but not HIV-2 or some other microorganisms associated with vaginal environment. Mycopathologia. 2005;159:213–218. doi: 10.1007/s11046-004-2226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas KG, Joly S. Carriage frequency, intensity of carriage, and strains of oral yeast species vary in the progresssion to oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:341–350. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.341-350.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wingeter MA, Guilhermetti E, Shinobu CS, Takaki I, Svidzinski TI. Identificação microbiológica e sensibilidadein vitro deCandida isoladas da cavidade oral de indivíduos HIV positivos. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:272–276. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu CJ, Lee HC, Yang YL, Chang CM, Chen HT, Lin CC. Oropharyngeal yeast colonization in HIV-infected outpatients in southern Taiwan: CD4 count, efavirenz therapy and intravenous drug use matter. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang YL, Hung CC, Wang AH, Tseng FC, Leaw SN, Tseng YT. Oropharyngeal colonization of HIV-infected outpatients in Taiwan by yeast pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2609–2612. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00500-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]