Abstract

Aims of the Study:

To study the frequency of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) in patients of diabetes mellitus with dry eye.

Materials and Methods:

A case-control cross sectional study.

Sampling:

Purposive random sampling. Totally, 200 eyes of 100 patients of diabetes mellitus and an equal number of eyes of normal subjects as control, who were gender and age matched and all of whom were symptomatic for dry eye were assessed for MGD by noting the symptoms and determining the meibomian gland expression scale for volume and viscosity, and ocular surface staining with Lissamine green, and Fluorescein sodium. All the subjects were graded for the severity of MGD. The results were compared in both the groups to ascertain whether the frequency of MGD in diabetics is significantly more as compared to nondiabetics.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were analyzed by Chi-square test for significance. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results:

There was a significant increase in the frequency of MGD in diabetics as compared to the nondiabetics.

Conclusion:

Diabetes mellitus is associated with MGD.

Keywords: Dry Eye, Meibomian Gland Dysfunction, Meibomian Gland Expression Scale

INTRODUCTION

Dry eye has been defined in “The Report of the International Dry Eye Workshop”1 as a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that result in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by an increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface.1 Evaluation of dry eye is primarily based on the aqueous component of the tear film and includes tests such as tear-film breakup time and schirmer's tests. However, the evaporative component of dry eye is generally ignored. The problem becomes compounded if the patient is a diabetic, as dry eye is 50% more common in diabetics compared to nondiabetics. The prevalence of diabetes is estimated at 12–15% in India2 and more individuals are bound to seek medical help for diabetes-related ocular problems such as dry eye.

The term meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) was first coined by Gutgesell et al. in 1982.3 It was defined by the Tear film and Ocular Surface Society in 2011 in the International workshop on MGD as “a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands (MG), commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/quantitative changes in the glandular secretion.”4 The ocular surface is covered by the precorneal tear film that is a mixture of mucin, aqueous, and lipids produced by various structures. The lipid layer stabilizes the tear film and reduces the evaporation of tears. In MG disease, there is blockage of the orifice and stasis of the oil within the gland resulting in decreased secretion and abnormal composition of the tear film lipid layer. These factors lead to increased tear evaporation and tear osmolarity and inflammation in and around the gland and the adjacent ocular surface. The resultant scarring and hyperkeratosis further aggravates the ductal stenosis and leads to MG dropout. Associated abnormal bacterial colonization further exacerbates the condition by changing lipid secretions and causing inflammation.5 However, MG dropout is not synonymous with MGD.

There is a complex relationship between dry eye due to aqueous layer deficiency and dry eye due to MGD. Decreased tear production results in retention and accumulation of inflammatory products along the lid margin, which can lead to hyperkeratinization, stenosis of the ducts and MGD. This in turn can lead to increased evaporation of tears resulting in surface inflammation that may be communicated by the neural feedback loop from the ocular surface to the lacrimal gland. The resultant decreased lacrimal gland function further exacerbates the dry eye. Thus, MGD and dry eye disease due to aqueous layer deficiency are closely interrelated with nearly indistinguishable symptoms.6

As dry eye is more common in diabetics, the aim of this study was to determine and compare the frequency of MGD in patients with diabetes mellitus compared to an age and gender matched population of nondiabetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

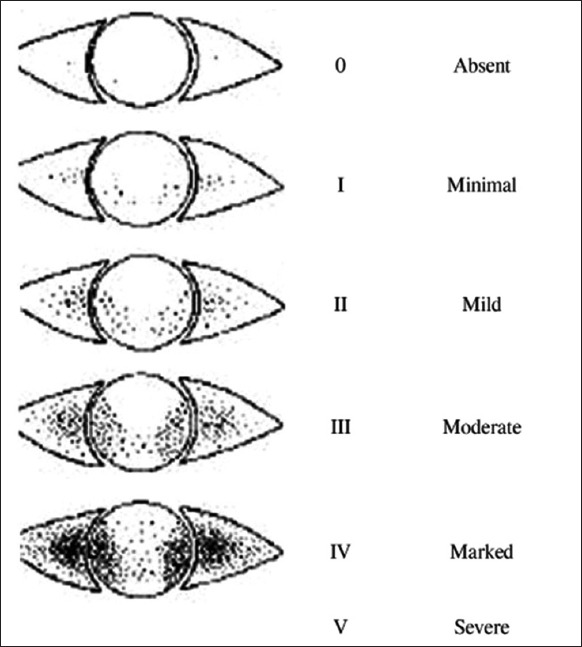

This was a cross-sectional, case-controlled study that evaluated 200 eyes of 100 diabetic (diabetic group) and 100 nondiabetic individuals (control group) respectively. The age range of both groups was from 40 to 65 years. Both the diabetic and control groups were enrolled from patients attending the hospital eye out patient department. The diabetic state was determined either by the history of medication for diabetes or an abnormal random blood sugar level of >200 mg/dl or HbA1C of >6.5% or fasting blood sugar of >126 mg/dl.7 Patients with pterygium, thyroid eye disease, on medications such as antihistamines and tricyclic antidepressants and postocular or refractive surgery were excluded from the study. After obtaining ethical clearance and ensuring informed consent, participants were assigned to age and gender matched diabetic and control groups. A detailed history was elicited for symptoms of ocular surface irritation such as foreign body sensation, grittiness, dryness, burning, teary eyes, and itching. Patients with frequent and persistent symptoms were classified grade 2 or higher on the MGD grading system. A general physical examination and detailed ophthalmic examination were performed. Corneal staining of the eye by an unquantified method was done, wherein a strip of commercially marketed sodium fluorescein containing 1 mg fluorescein (Fluostrip; Contacare Ophthalmics and Diagnostics, Gujarat, India) was moistened with a drop of saline, any excess saline was shaken off and the strip was applied to the inferior palpebral surface. The staining pattern was evaluated within 2 min at the slit lamp with ×16 magnification. After an interval of 5 min, the ocular surface was stained in a similar fashion with Lissamine green strips (Akriti ophthalmic products) each containing 1.5 mg of Lissamine green per strip. Examination at the slit lamp with ×16 was performed at a standard time interval of 1 min after placement of impregnated strip of Lissamine Green in the inferior fornix as staining is both time and concentration dependent. Lissamine green staining of the conjunctiva and fluorescein staining of the cornea were graded according to the Oxford grading scale7 as mild (grade I and II) moderate (grade III), and severe (grade IV and V) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Oxford panel for grading of corneal and conjunctival staining

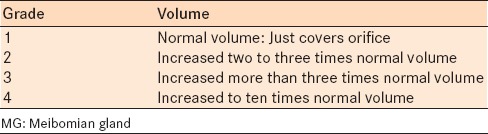

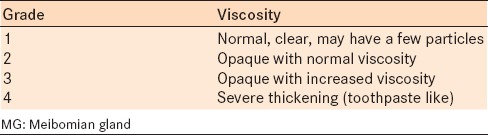

Meibomian gland function was assessed by examining the meibum expressed from the glands for volume and viscosity [Table 1a and b].8 Firm digital pressure was applied over the middle and nasal one-third of the upper and lower eyelid with the lid compressed against the globe until a dome of lipid was expressed from the orifice.

Table 1a.

Grading of MG expression: Volume

Table 1b.

Grading of MG expression: Viscosity

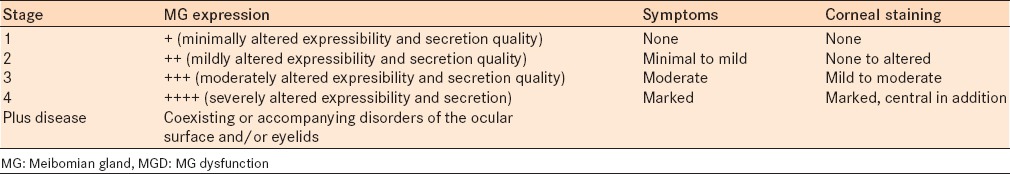

Meibomian gland dysfunction was graded based on the presence of all three of the following criteria: MG expression scale; symptoms and corneal staining [Table 2].4 All examinations were performed by a single observer (s) to exclude subjective bias.

Table 2.

Clinical summary of MGD staging

RESULTS

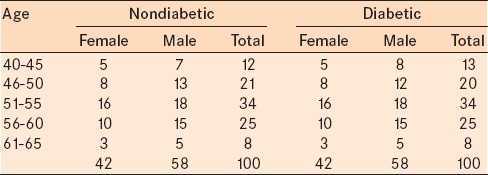

There were a total of 116 males and 84 females in the study. The youngest participant was a 40-year-old male, and the oldest was a 65-year-old male. The mean age of the participants was 52.36 ± 5.82 years in the nondiabetic group and 52.43 ± 6.0 years in the diabetic group. The mean age of males was 52.72 ± 5.96 years and 51.85 ± 5.6 years and of females was 52.5 ± 6.18 years and 52.33 ± 5.8 years in the control group and the diabetic group, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Age and gender distribution in nondiabetics and diabetics

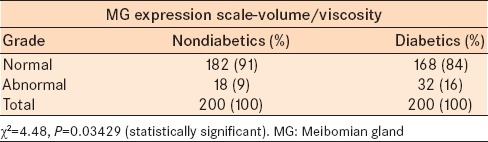

In the MG expression scale for volume and viscosity, 182 eyes in the control group and 168 eyes in diabetic group were grade 1. There were 18 eyes in the control group and 32 eyes in the diabetic group with grades 2 and 3 (moderate to severe alteration in volume and viscosity) which is considered abnormal [Table 4]. The frequency of abnormal MG expression grading (volume and viscosity) was significantly greater in the diabetic group as compared to the control group (Chi-square = 4.48, P = 0.03429).

Table 4.

Distribution of the proportion of the MG expression scale (volume and viscosity) in nondiabetics and diabetics

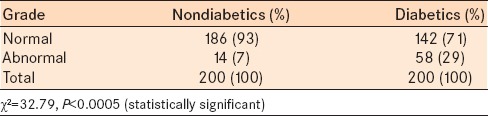

The number of eyes with grade 1 to IV Lissamine green and Fluorescein staining were significantly greater in the diabetic group (58 eyes) compared to the control group (14 eyes) (Chi-square = 32.79, P < 0.0005) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Distribution of proportion of various grades of lissamine and fluorescein staining in nondiabetics and diabetics

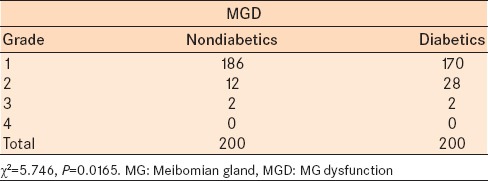

Meibomian gland dysfunction was assessed from the data of the MG expression scale – volume and viscosity, symptoms and staining of the eye and staged as 1, 2, 3, and 4. Grade 1 was considered normal as it included near normal MG expression and no symptoms with nil to minimal staining. In the diabetic group, 170 eyes were normal and 30 eyes had significant MGD (grade 2–4) compared to 186 normal eyes and 14 eyes with significant MGD (grade 2–4) in the control group [Table 6]. The results when analyzed with the Chi-square test showed a statistically significant difference in the severity of MGD in diabetics compared to the control group (Chi-square = 10.039, P = 0.0015).

Table 6.

Distribution of MGD in nondiabetics and diabetics

DISCUSSION

Ocular surface abnormalities during the course of diabetes mellitus have been documented in recent years. Studies by Seifart and Strempel9 show that 57% of type 1 diabetics, and 70% of type 2 diabetics have proven dry eye disease. They also found that higher the Hb1AC values, greater the severity of dry eye disease. The likely reason for the increased prevalence of dry eye in diabetics as compared to healthy subjects is the associated autonomic dysfunction seen in them. Diabetics are also found to have decreased corneal sensation more so in those having peripheral neuropathy. Studies have shown that the lacrimal gland function in diabetes mellitus is influenced by the associated peripheral neuropathy causing reduced basal tear production. Aldose reductase, the first enzyme of the sorbitol pathway, may also be involved. The oral administration of aldose reductase inhibitors has been shown to improve tear dynamics significantly.10 Diabetic retinopathy is associated with a decreased tear film function which is more severe in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy than those with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes mellitus may also be associated with or result in diverse orbital and adnexal problems such as blepharitis, blepharoptosis, xanthomas, and orbital infections.9

The aim of this hospital-based study was to determine the frequency and severity of MGD in diabetics compared to nondiabetics. However, correlation to blood sugar levels and severity of diabetic retinopathy was not evaluated. The grading of MGD was based on the report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of MGD.4

The quantitative and qualitative abnormalities of the lipid layer, secondary to MGD, can cause evaporative dry eye. In our study, there was a statistically significant difference in the frequency of moderate to severe alteration in MG secretion volume and viscosity between the nondiabetic (control) group and the diabetic group (P = 0.03429). There was also a statistically significant increase in corneal staining in the diabetic group as compared to the nondiabetic group (P < 0.0005).

Hom et al. reported a 38.9% prevalence of MGD in 398 subjects.11 We found that in the control group of 200 eyes there were 12 with stage 2 MGD and only 2 with stage 3 MGD (7% with MGD of stage 2 or above), and the rest (186 eyes) were stage 1 MGD (93%). In the diabetic group, there were 28 eyes with stage 2 MGD, and 2 eyes with stage 3 MGD (15% with MGD of stage 2 or above), and the rest (170 eyes) were stage 1 MGD (85%). The overall frequency of significant MGD in our study was 11% (44 out of 400 eyes). Epidemiological study of MGD is limited because there is no consensus on the criteria for standardized clinical assessment for MGD. The prevalence of MGD varies considerably in the literature from 3.5% to almost 70%, and it appears to be higher in Asian populations.8 The prevalence of MGD was 46.2% in a study from Bangkok12 and 60.8% in a Tiawanese eye study.13 A Japanese study reported a prevalence of 61.9%,14 and the Beijing Eye Study,15 reported a prevalence of 69.3%. In Caucasians MGD ranges from 3.5% in the Salisbury Eye Evaluation study,16 to 19.9% in the Melbourne study.17 In all these studies MGD was evaluated based on symptoms such as the frequency of eye dryness, gritty/sandy sensation, burning sensation, sticky sensation, watering/tearing, redness, crusting/discharge, and eyes stuck shut. However in our study, MGD was evaluated not only on the basis of symptoms but also corneal staining and MGD expression scale. In this study, the stages of MGD were primarily based on the altered expressibility and quality of the secretion of the MGs and corneal staining. A single observer (s) performed all examination to avoid any interobserver bias. Hence, eyes with minimally altered viscosity or volume of the secretion, prone to observer bias and with nil to minimal corneal staining and infrequent intermittent symptoms, were classified as stage 1 MGD which was considered normal for all practical purposes. The cut-off considered subjects significant MGD was stage II or above in our study. The samples selected for the study for both groups were those with ocular symptoms so that there would be a better study result yield although they were not specifically evaluated for dry eye.

A clinically significant finding of this study was the increased frequency of significant MGD in the diabetic group (15%) which was more than twice the prevalence in the non-diabetic (control) group (7%) (P = 0.0015). Since the prevalence of diabetes is about 12–15% in India, more individuals are likely to seek medical help for diabetes-related ocular problems such as MGD.

Meibomian gland dysfunction is an important cause of dry eye and the frequency of the more severe form is significantly greater in diabetics. This may be one of the causes for the increased prevalence of dry eye in diabetics. This study sampled a rural coastal population presenting to a tertiary hospital. However, these findings are not reflective of the entire population. Also, the sampled population was a symptomatic group that will alter the results. Hence, study with a larger, more representative population is warranted to assess the effects MGD in diabetics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Research in dry eye: Report of the research subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Work Shop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:179–93. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutgesell VJ, Stern GA, Hood CI. Histopathology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:383–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, Glasgow BJ, Dogru M, Tsubota K, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1922–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert DW. Physiology of the tear film. In: Smolin G, Thoft RA, editors. The Cornea. 3rd ed. Noida, India: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers WD. Meibomian gland disease. In: Pflugfelder SC, Beuerman RW, Stern ME, editors. Dry Eye and Ocular Surface Disease. Canada: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2004. pp. 247–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers AC. Diabetes mellitus. In: Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson J, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. USA: McGraw Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathers WD, Shields WJ, Sachdev MS, Petroll WM, Jester JV. Meibomian gland dysfunction in chronic blepharitis. Cornea. 1991;10:277–85. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifart U, Strempel I. The dry eye and diabetes mellitus. Ophthalmologe. 1994;91:235–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujishima H, Shimazaki J, Yagi Y, Tsubota K. Improvement of corneal sensation and tear dynamics in diabetic patients by oral aldose reductase inhibitor, ONO-2235: A preliminary study. Cornea. 1996;15:368–75. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hom MM, Martinson JR, Knapp LL, Paugh JR. Prevalence of meibomian gland dysfunction. Optom Vis Sci. 1990;67:710–2. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lekhanont K, Rojanaporn D, Chuck RS, Vongthongsri A. Prevalence of dry eye in Bangkok, Thailand. Cornea. 2006;25:1162–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000244875.92879.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin PY, Tsai SY, Cheng CY, Liu JH, Chou P, Hsu WM. Prevalence of dry eye among an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: The Shihpai eye study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1096–101. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchino M, Dogru M, Yagi Y, Goto E, Tomita M, Kon T, et al. The features of dry eye disease in a Japanese elderly population. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:797–802. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000232814.39651.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jie Y, Xu L, Wu YY, Jonas JB. Prevalence of dry eye among adult Chinese in the Beijing Eye study. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:688–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schein OD, Muñoz B, Tielsch JM, Bandeen-Roche K, West S. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:723–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarty CA, Bansal AK, Livingston PM, Stanislavsky YL, Taylor HR. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1114–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]