Abstract

Given their essential role in adaptive immunity, antigen receptor loci have been the focus of analysis for many years and are among a handful of the most well studied genes in the genome. Their investigation led initially to a detailed knowledge of linear structure and characterization of regulatory elements that confer control of their rearrangement and expression. However, advances in DNA FISH and imaging combined with new molecular approaches that interrogate chromosome conformation have led to a growing appreciation that linear structure is only one aspect of gene regulation and in more recent years the focus has switched to analyzing the impact of locus conformation and nuclear organization on control of recombination. Despite decades of work and intense effort from numerous labs we are still left with an incomplete picture of how antigen receptor loci are regulated. This chapter summarizes our advances to date and points to areas that need further investigation.

Keywords: RAG, V(D)J recombination, allelic exclusion, ATM, homologous pairing, nuclear organization, pericentromeric heterochromatin, CTCF

1. OVERVIEW OF V(D)J RECOMBINATION

In total there are seven antigen receptor loci, four T cell receptor (Tcr) loci (Tcrg, Tcrd, Tcrb and Tcra) and three B cell specific immunoglobulin genes (Igh, Igk and Igl). B and T cells make use of this modest investment in DNA to generate an almost infinite assortment of different specificity receptors that can be used to combat a wide variety of invading pathogens. Somatic rearrangement of variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) gene segments arrayed along each locus generates this receptor diversity enabling specific recognition of foreign antigen, which is a fundamental feature of the adaptive immune response (Helmink and Sleckman, 2012; Tonegawa, 1983).

1.1 RAG binding

Recombination is mediated by the lymphoid-specific recombinase, consisting of RAG1 and RAG2 (the protein products of the recombination activating genes 1 and 2). The RAG1 protein, which harbors the endolytic activity, functions in conjunction with RAG2, a co-factor that is essential for recombinase activity (Mombaerts et al., 1992; Shinkai et al., 1992; Spanopoulou et al., 1994). The RAG1 protein cleaves specifically at highly conserved recombination sequences (RSSs) made up of heptamers and nonamer motifs separated by non-conserved spacers of either 12 or 23bps (Kim et al., 1999; Landree et al., 1999). The RAG1/2 complex preferentially binds two RSS sites of different spacer lengths, brings them together and cuts at the borders of these elements generating DSBs. RSSs, which flank the individual V, D and J gene segments, are distributed throughout each antigen receptor locus and synapse formation and cleavage can occur between regions that are many kilobases apart. The four broken ends (two coding ends and two signal ends) are held together in a RAG post cleavage complex that directs repair through the non homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which is important for the maintenance of genome stability (Deriano et al., 2011; Helmink and Sleckman, 2012; Lee et al., 2004; Schatz and Swanson, 2011). Recent ground breaking analyses of the crystal structures of these two proteins indicates that the RAG1-RAG2 heterotetramer is Y-shaped, with a RAG1-RAG2 heterodimer constituting each arm (Kim et al., 2015). The structure explains numerous mutations known to be associated with immunodeficiencies.

According to ChIP-seq analysis, the binding profile of RAG1 and RAG2 overlaps with that of H3K4me3 (Ji et al., 2010). Promiscuous genome wide binding to this active chromatin mark is mediated via a plant homeodomain (PHD) in RAG2 (Liu et al., 2007b; Matthews et al., 2007). However, each RAG protein can bind in the absence of the other, and when RAG1 is bound without RAG2 it binds in an RSS specific manner and is not found at H3K4me3 enriched promoters (Ji et al., 2010). This finding suggests that binding of the proteins can occur individually at differential locations or together as a preformed RAG1/2 complex that directs both proteins to RSSs as well as H3K4me3 enriched regions.

The question of how and what controls RAG targeting at the locus and allele specific level on the individual antigen receptor loci continues to be an area under investigation. Moreover, there is the puzzle about how, in normal circumstances, other genes in the genome with the appropriate or cryptic recognition sequences are protected from being cleaved. Since cryptic RSSs are found every 1–2Kb in the genome, promiscuous RAG1 binding could contribute to off-target cleavage occurring within non-antigen receptor loci. Indeed RAG targeting has been linked to genetic defects in IKZF1, Notch1, SIL-SCL, Bcl11b, PTEN, ETV6, BTG1, TBL1XR1, and CDKN2A-CDKN2B that are associated with numerous B and T acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs) (Mendes et al., 2014; Mullighan et al., 2008; Onozawa and Aplan, 2012; Papaemmanuil et al., 2014).

1.2 Lineage and stage specific rearrangement

Given the risks entailed by repeated cutting and pasting, V(D)J recombination is tightly regulated with respect to target gene accessibility, RAG expression and the activities of the DNA damage signaling and repair pathways. As the recombinase machinery (the RAG proteins) and the DNA targets (RSSs) are the same for each antigen receptor locus in both lineages, lymphocytes restrict recombination by controlling the accessibility of the individual loci (Figure 1). First, rearrangement is restricted by lineage: Ig gene segments complete rearrangement only in B cells, and Tcr gene segments rearrange only in T cells. Second, rearrangement is ordered by stage within a given lineage: the Ig heavy chain (Igh) is rearranged at the pro-B cell stage of development prior to Ig light chain (kappa or lambda) rearrangement in pre-B cells. Furthermore, DH-to-JH recombination at the Igh locus must take place in pre-pro-B cells before VH-to-DJH rearrangement can begin in pro-B cells.

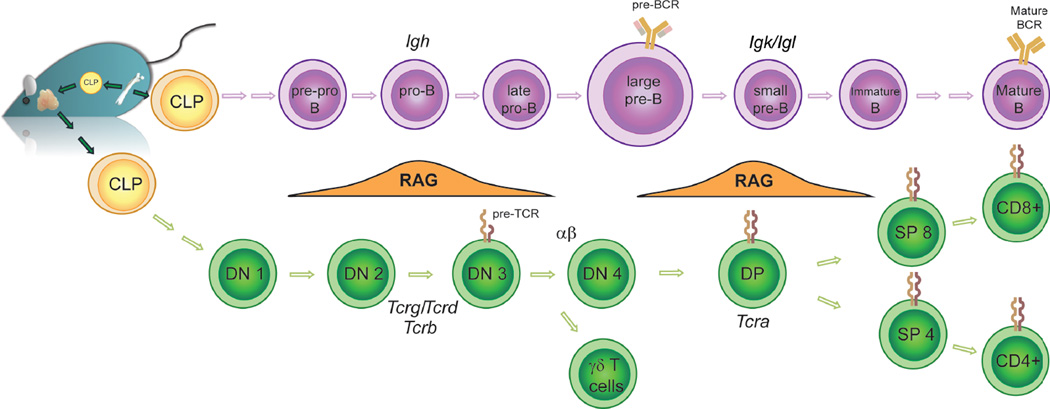

Figure 1.

Scheme showing the different stages of B and T cell development where rearrangement of the Ig or Tcr loci take place.

In T cells the situation is more complex as productive rearrangement of the different Tcr loci gives rise to two distinct lineages: Tcrg/Tcrd and Tcrb/Tcra recombination leads to γδ and αβ T cells, respectively (Ciofani and Zuniga-Pflucker, 2010; Krangel, 2009). Nonetheless, recombination of the different loci overlaps such that Tcrg, Tcrd and Tcrb are all rearranged at the early CD4−CD8− double negative DN2/3 stage of development, while Tcra recombination occurs later in double positive (DP) cells after successful Tcrb rearrangement (Livak et al., 1999). In addition, promiscuous DH-to JH rearrangement of the Igh locus occurs at low level in T lineage cells (predominantly the DN cell stage) (Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Kurosawa et al., 1981). Multi-locus rearrangement in the same developmental compartment increases the risks associated with recombination and the probability of aberrant repair (Chaumeil et al., 2013b). Regulation of recombination is further complicated because Tcra and Tcrd, which are rearranged in DN and DP cell stages, respectively, share the same chromosomal location with Tcrd embedded between the Vα and Jα gene segments of Tcra.

2. LINEAR STRUCTURE OF THE ANTIGEN RECEPTOR LOCI

Antigen receptor loci consist of large arrays of V gene segments (ranging from 34 in Tcrb to 183 segments in Igh that are dispersed over 0.67Mb and 2.4Mb, respectively). A much smaller proximal domain containing D, J and C gene segments that encompass potent enhancers, occupies genomic regions in the kb range (4kb in Igk, 25kb in Tcrb, 70kb in Tcra and 26kb in Igh). Although all the loci are comprised of the same basic units (V, D and J gene segments) that are flanked by RSSs and a constant region, each antigen receptor locus has a unique structure that impacts their regulation (Figure 2–5).

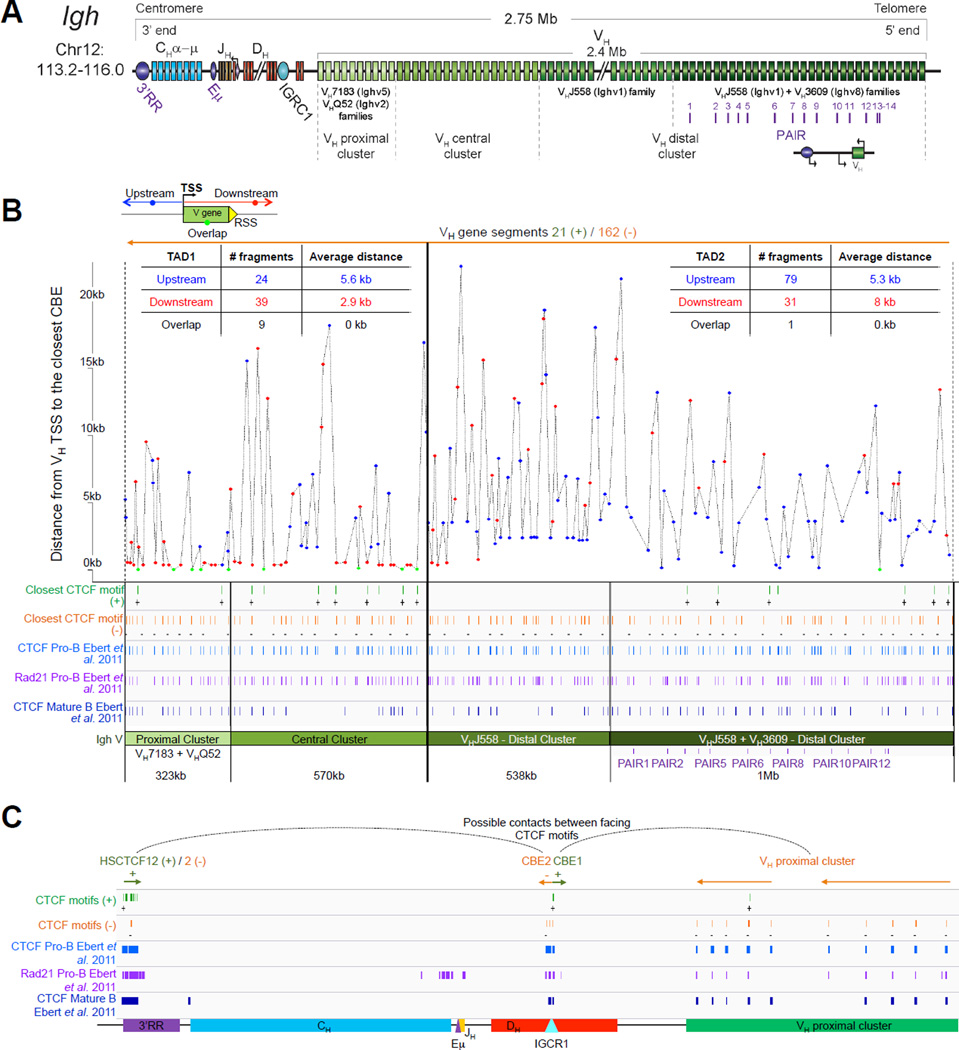

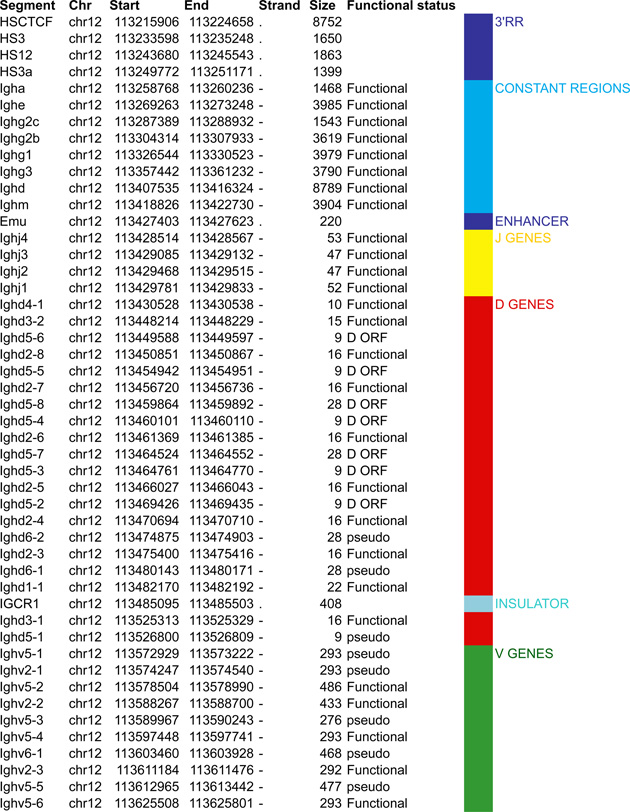

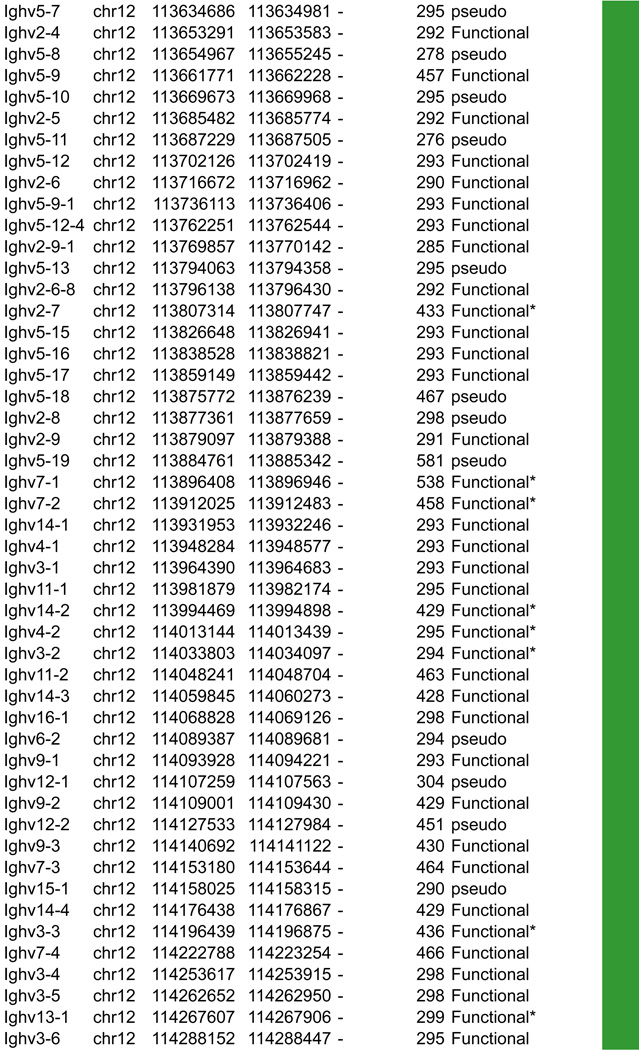

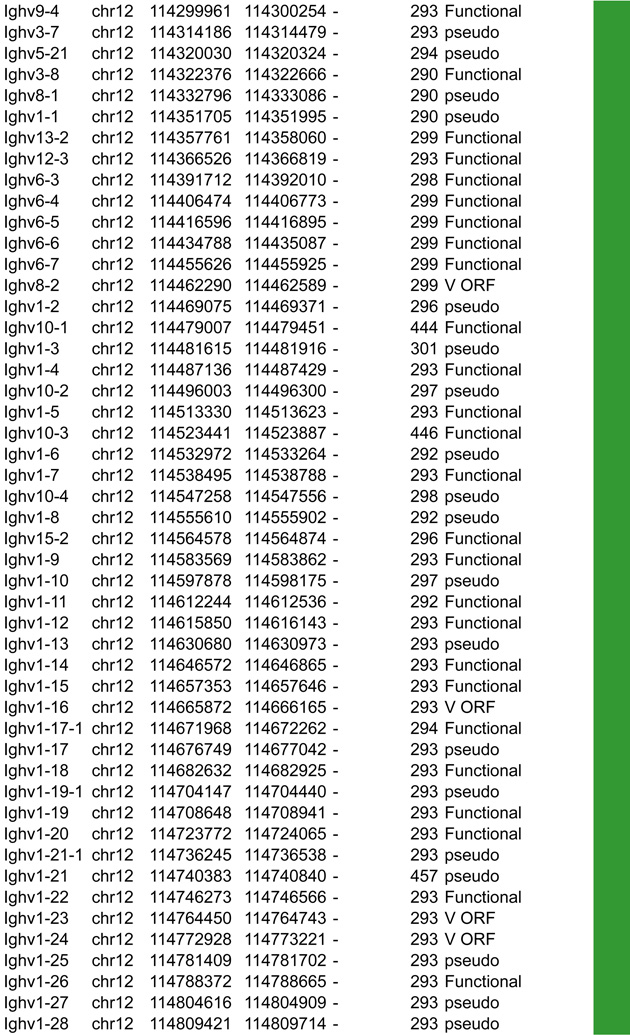

Figure 2.

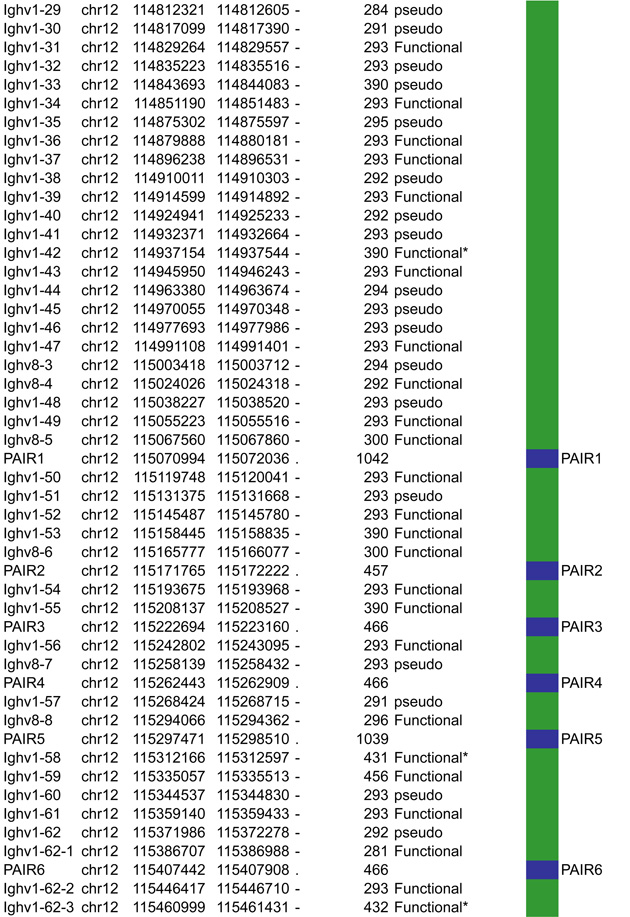

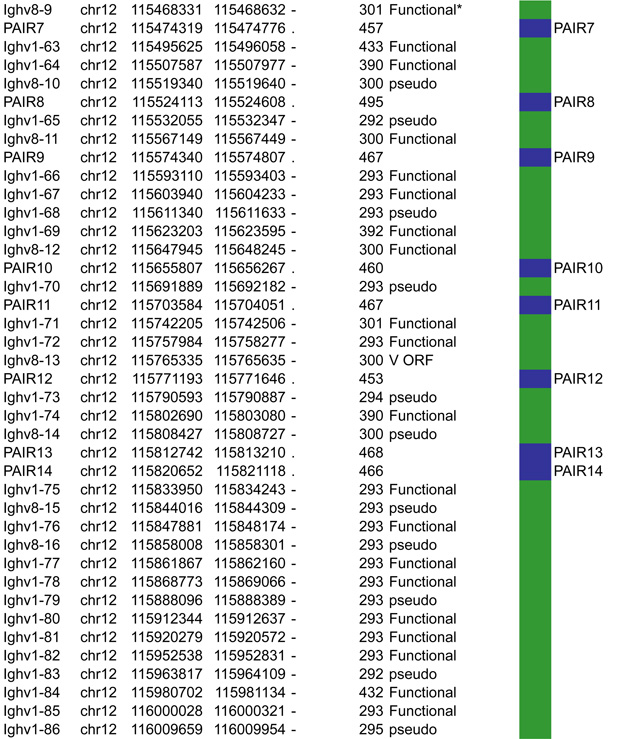

A. Igh linear structure and its cis acting elements. Igh spans 2.75Mb. VH, DH, JH and CH segments are organized in separate clusters with all segments in the same 5’-to-3’ orientation on the minus strand of chromosome 12. Igh contains 183 VH segments (113 functional), 20 DH segments (10 functional), 4 JH and 8 CH (all functional). It is of note that 2 DH segments (one of which is functional) are located 5’ to the intergenic insulator IGCR1. The VH array contains VH sub-clusters determined by the type of VH families represented: the proximal cluster enriched for VH7183 (IghV5) and VHQ52 (IghV2) segments; the central cluster which does not include specific family types and the distal cluster enriched for VHJ558 (IghV1) and VH3609 (IghV8) segments. B. Distribution of CTCF binding elements (CBEs) within the Igh VH gene region. Distance from the TSS of each VH gene to the closest CBE is reported and marked as upstream, downstream or overlapping depending on the CBE location relative to the TSS. Closest CBEs have been selected among motifs falling within CTCF peaks called from pro-B cells ChIP-seq data (Ebert et al., 2011). CTCF motifs were called using FIMO (part of the MEME suite) with p-value < 10e-4. This analysis identifies 125 CBEs (54 in TAD1 and 71 in TAD2). The vast majority of VH segments (162 of the 183) are associated to a CBE on the minus strand (+), pointing towards the 3’ end of the Igh locus. The average distance between a VH segment and its closest CBE is around 5kb and overall there is no relationship to upstream or downstream localization of the motif. However, the Murre lab described two sub-domains constituting the VH array (annotated TAD1 and TAD2 here) (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2008) which show specificity in localization of the closest CBE associated with different distances. TAD1 contains more downstream sites which are closer than upstream ones. In contrast, TAD2 contains more upstream sites which are closer than the downstream ones. C. Zoomed in region of the 3’end of Igh to highlighting the orientation of CBEs. CTCF binding motifs have been selected by intersection with CTCF peaks called from published pro-B cell ChIP-seq data (Ebert et al., 2011). CBE1 and CBE2 are pointing away from one another i(Lin et al., 2015) potentially enabling loop formation between convergent motifs on CBE1 and the 5’ VH cluster and CBE2 and the 3’RR. Segment annotations, with coordinates, strand orientation and functional status as well as coordinates for regulatory elements are provided in Table 1. Annotations correspond to the mm10/GRCm38 genome assembly which uses the C57BL/6 strain as genome reference and were collected from NCBI (Igh gene ID: 111507; Igk gene ID: 243469; Tcrb gene ID: 21577; Tcra Gene ID: 21473) and IMGT/LIGM-DB databases (Giudicelli et al., 2006). VH segments (green), DH segments (red), JH segments (orange) and CH constant region (blue), enhancers (purple), insulators (aqua).

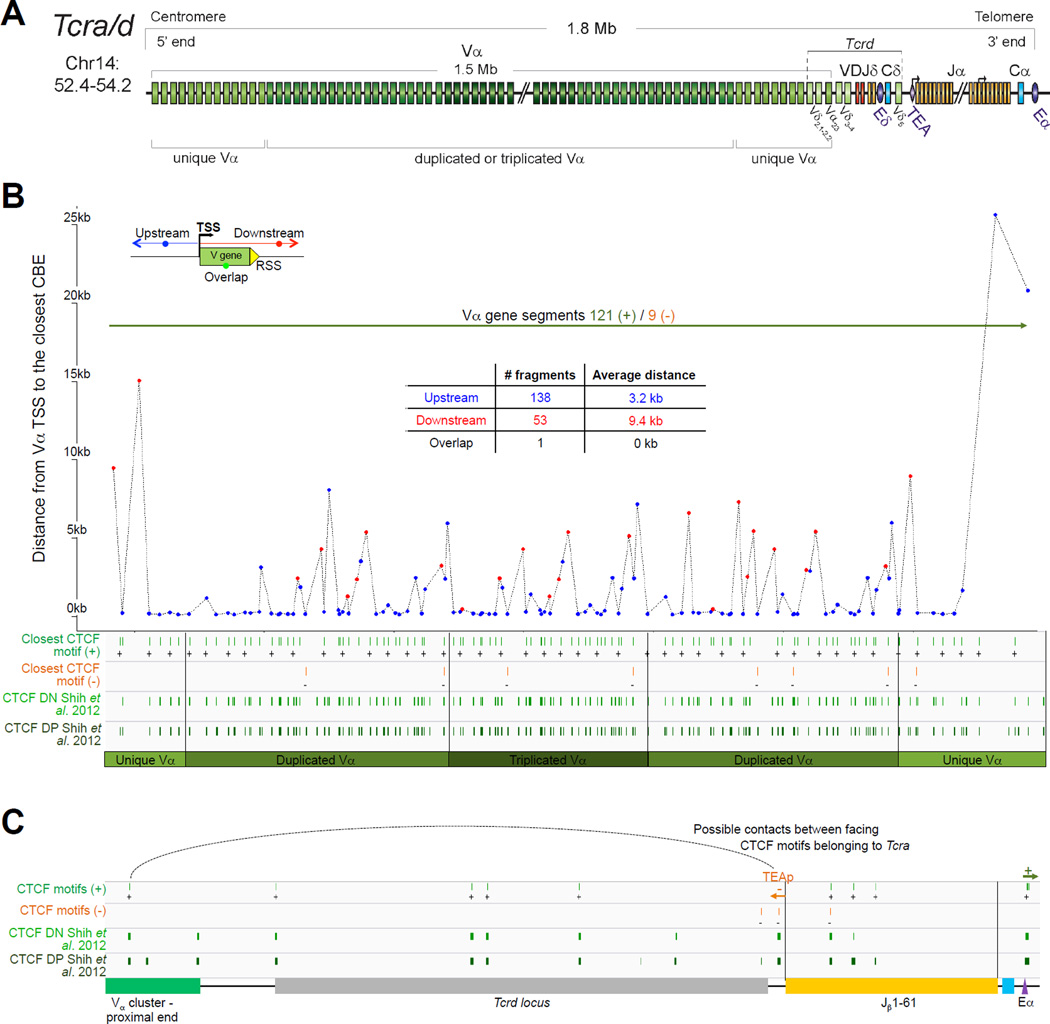

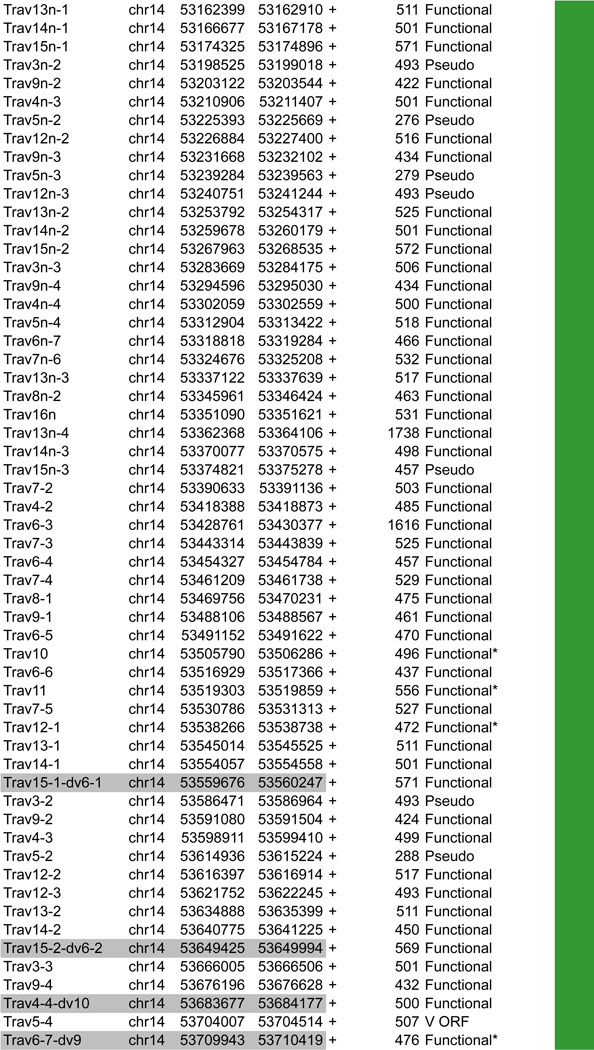

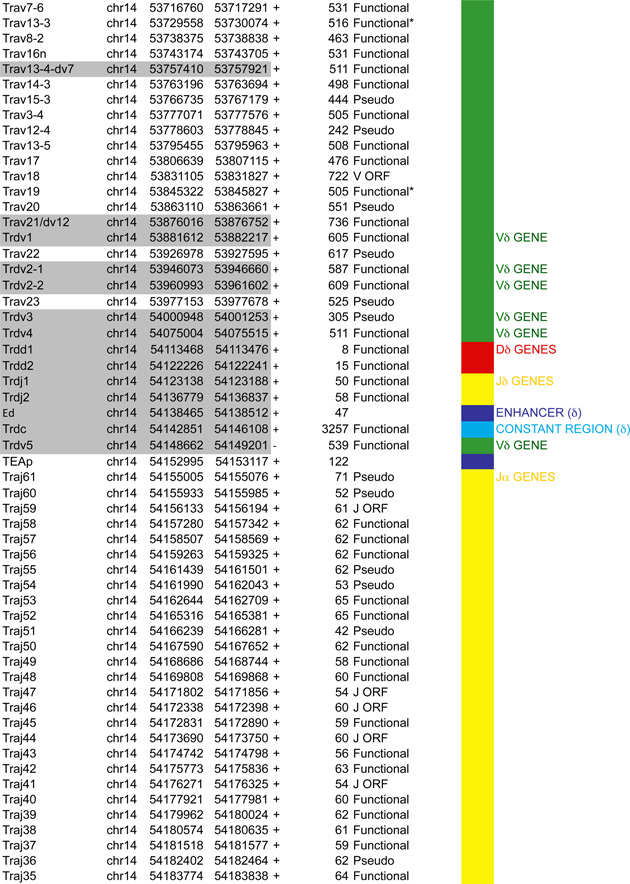

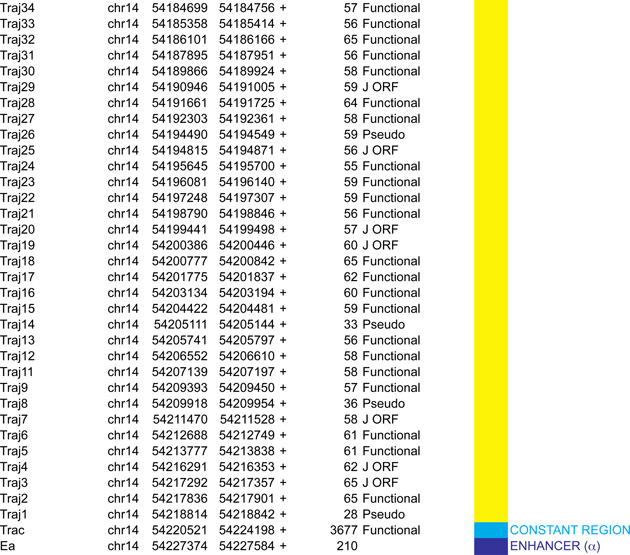

Figure 5.

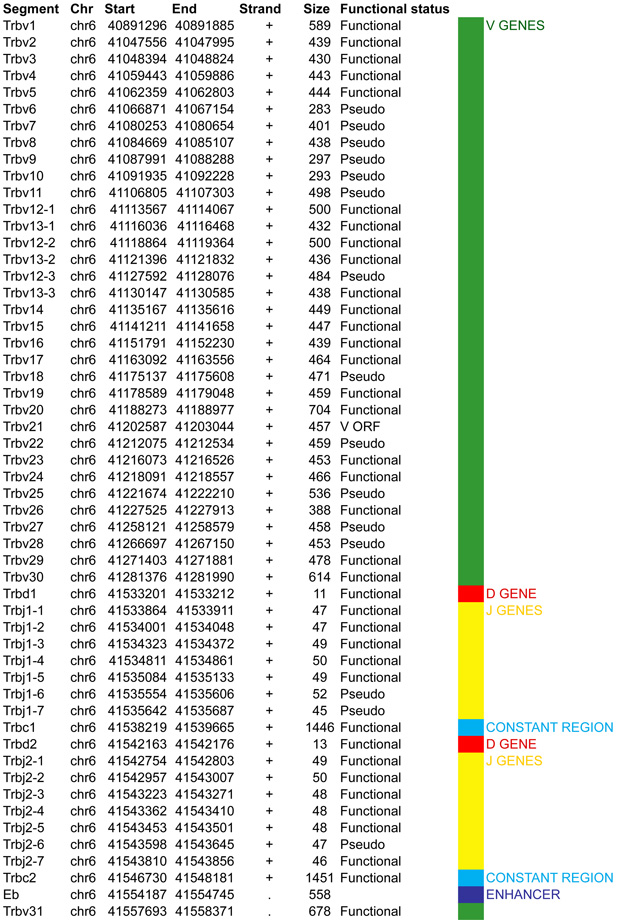

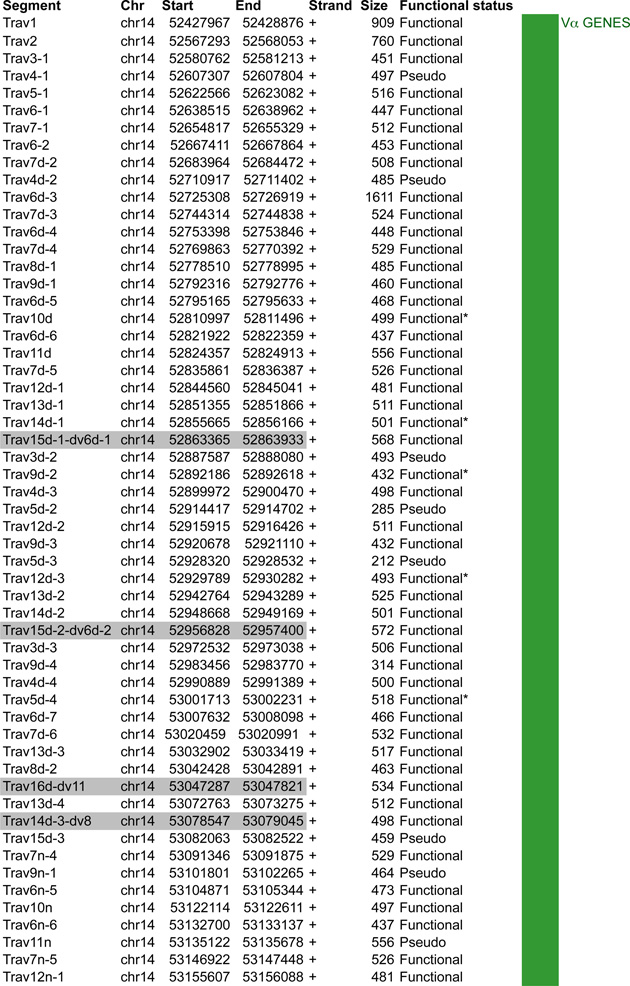

A. Tcra linear structure and its cis acting regulatory elements. Tcra spans 1,65Mb on the murine chromosome 14. It contains 130 Vα segments (108 functional) spread out over 1.55Mb and located upstream of 60 Jα genes (38 functional) and a single Cα gene. In the C57BL/6 background, the Vα array is composed of triplicated clusters located in the center with 8 and 10 unique segments on each side respectively. Tcra shares V segments with the Tcrd locus that is embedded within its locus. These 10 V segments, annotated Trav*-dv*, rearrange either to Jα or to Dδ. B. CTCF binding element (CBE) distribution along Tcra V segments array. Closest CTCF binding motifs from the TSS of each Vα gene segment were called using CTCF peaks from DP cells ChIP-seq data (Shih et al., 2012). The Vα cluster harbors 124 closest CBEs. 121 of the 130 Vα segments are associated to CTCF motifs in the same orientation ((+) orientation) pointing towards the 3’ end of the Tcra locus. The average distance between a Vα segment and its closest CTCF motif is around 3kb for motifs located upstream and 9kb for motifs located downstream. C. Zoomed in region of the proximal domain of Tcra to highlight the orientation of CBEs. The CTCF motif associated to TEAp (−) is facing the (+) motifs of the V segments towards the 5’ end of the locus.

2.1. Igh

The murine Igh locus spans 2.75Mb (nearly a quarter of the yeast genome) and is located at the distal end of chromosome 12 in mouse. It contains a total of 113 functional VH segments that are dispersed over 2.4Mb. Igh holds 10–15 functional DH segments (depending on the mouse strain), 4 JH gene segments and 8 different constant regions that are all preceded by switch regions with the exception of Cδ. These are used as substrates for class switch recombination (CSR) which generates different Ig isotypes that streamline antibody effector function after encounter with an antigen (IgE, IgG, IgA etc) (Figure 2A).

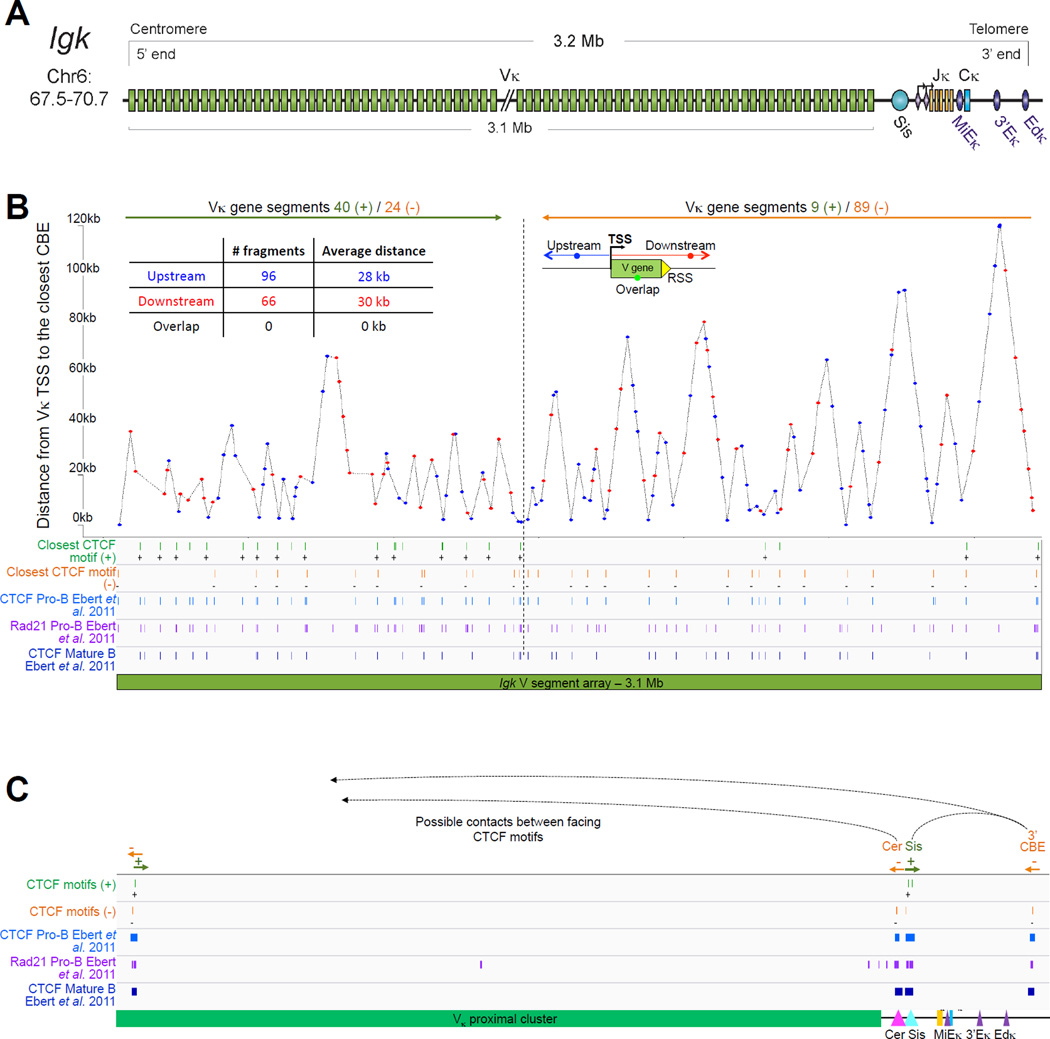

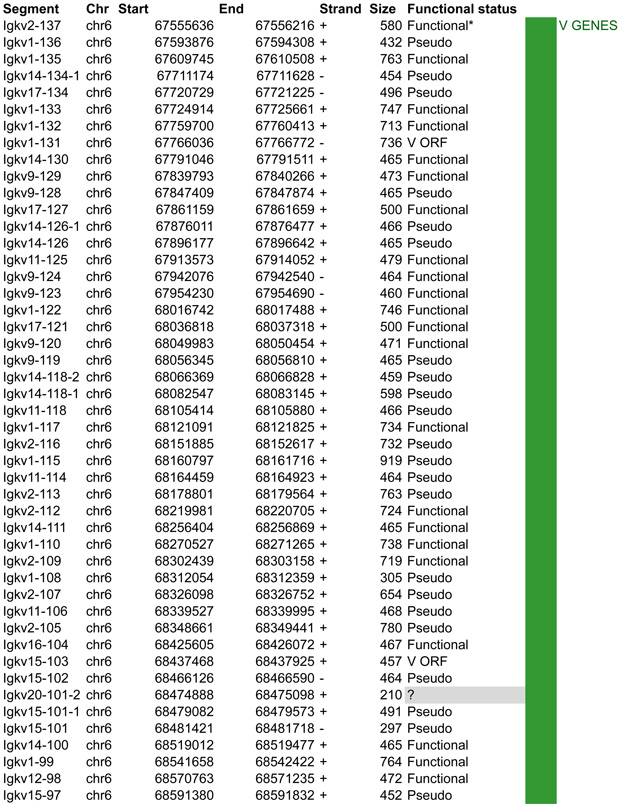

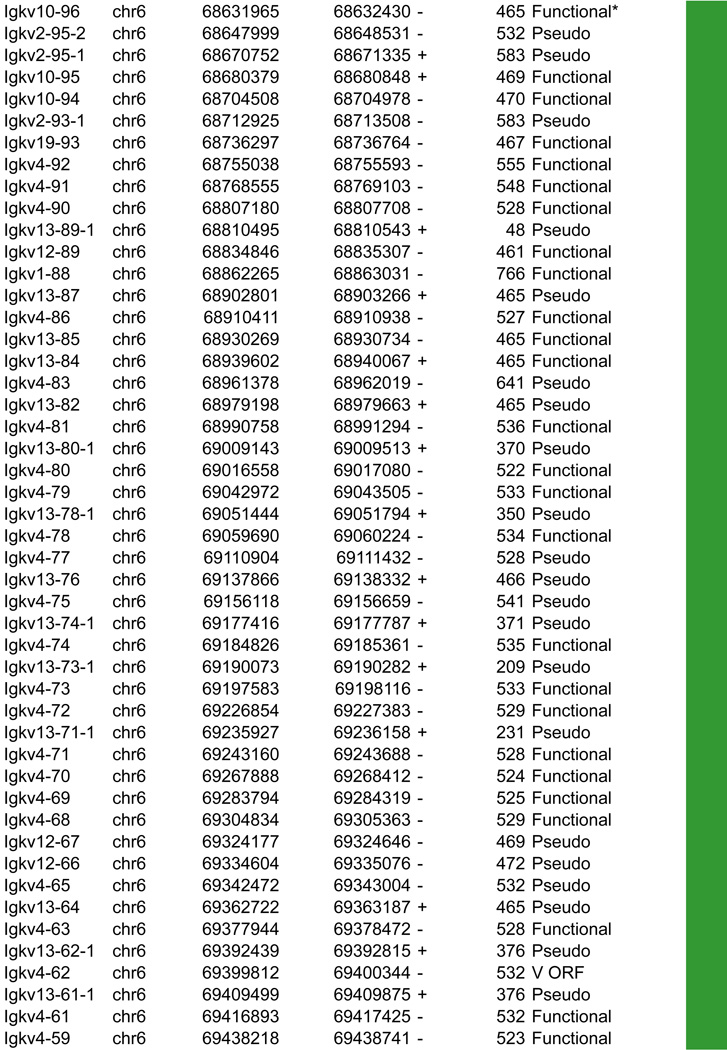

2.2 Igk

The Igk light chain locus is located on the mouse chromosome 6. It spans 3.17Mb and contains 92 functional Vκ segments, 4 functional Jκs and a single Cκ region. In contrast to Igh, Igk does not contain any D gene segments (Figure 3A). Another feature of the Igk locus is that half of the Vκs are in reverse orientation and are rearranged by non-destructive inversion, which leads to retention of the segments located between the joining Vκ and Jκ segments. This conserves Vκ segments for (i) secondary rearrangements that can occur with remaining downstream Jκs in the event of nonproductive rearrangement, and (ii) receptor editing which functions to eliminate self reactive receptors or enable IGK to associate with IGH (Feddersen et al., 1990; Halverson et al., 2004; Pelanda et al., 1997; Prak and Weigert, 1995; Tiegs et al., 1993). Ongoing rearrangement and receptor editing is possible because of the lack of D gene segments and recombination on each allele can continue until all the Jκ gene segments are used up. Based on the delayed activation of Igl, it is estimated that three rounds of rearrangement are possible for each Igk allele (Arakawa et al., 1996), which corresponds to the number of functional Jκ gene segments. While no specific order is determined for Vκ rearrangement (Nadel et al., 1998), primary rearrangement generally involve the most 5’Jκ segment, Jκ1 (Yamagami et al., 1999).

Figure 3.

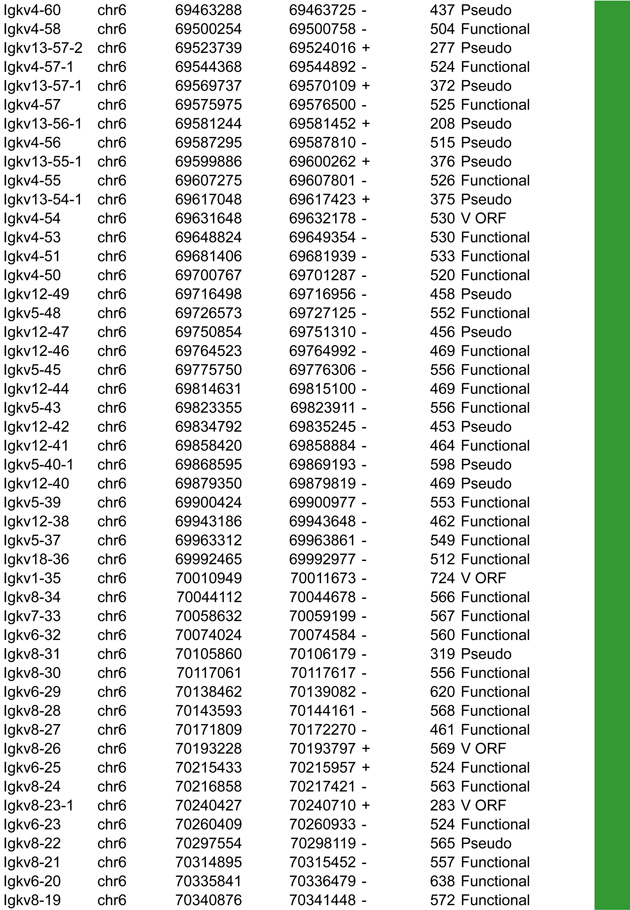

A. Igk linear structure and its cis acting regulatory elements. Igk spans 3.17Mb on the murine chromosome 6. It contains 162 Vκ segments (92 functional), 5 Jκs (4 functional, Jκ3 is a pseudogene with a mutated RSS not recognized by RAG) and a single Cκ region. Half of the Vκs are positioned in reverse orientation and are rearranged by non-destructive inversion. All the other segments of the locus follow a (+) strand orientation. B. CTCF binding element (CBE) distribution within the Vκ region. Closest CTCF binding motifs from the TSS of each Vκ gene segment were called using CTCF peaks from pro-B cells ChIP-seq data (Ebert et al., 2011). The Vκ cluster harbors 59 closest CBEs which display alternative orientation but there is an enrichment of Vκ segments associated to (+) motifs at the distal part and (−) motifs at the proximal part of the Vκ cluster (40 (+) / 24 (−) versus 9 (+) / 89 (−) respectively). It should be noted that several segments can be associated with the same CTCF motif. The fact that Vκ rearrangement can occur via inversion could explain this non specific orientation that is in contrast to what is seen for the Igh locus. There is no apparent correlation between the CTCF motif orientation and the Vκ segment orientation. However there are more segments associated to a CTCF motif with the same orientation (62%) as opposed to an inverse orientation (38%). The average distance between a Vκ segment and its closest CTCF motif is much larger than for Igh - 30kb versus 5kb – and there is no relationship to upstream or downstream localization of the motif. C. Zoomed in region of the proximal domain of Igk to highlight the orientation of CBEs. The CTCF motif at the 3’ boundary is directed towards the Igk locus, which could facilitate intra-locus contacts. Cer and Sis display a similar organization to IGCR1, which encompasses CBE1 and 2 in Igh that have opposite orientations pointing away from each other towards the 5’ end and the 3’ end respectively. Sis and the 3’ boundary anchor display constitutive CTCF binding throughout B cell development. They contain motifs with a head to head orientation that could promote proximal domain segregation, which is important for limiting proximal Vκ recombination and restricting Igk enhancer interactions to the Igk locus outside of its rearrangement stages (Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2011; Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2011).

2.3 Tcrb

The T cell receptor beta locus, Tcrb, is encoded by 700kb of DNA on mouse chromosome 6. The vast majority of the locus (~624kb) is comprised of 22 functional Vβ gene segments. Except for Vβ31, which is localized downstream of the proximal domain in an inverted orientation, all the Vβ genes are located upstream of a duplicated cluster of ‘1 Dβ, 7 Jβ and 1 Cβ’ of which 11 of the 14 Jβs are functional. In addition to this atypical proximal duplication, 2 clusters of trypsinogen genes, that are inactive in lymphocytes, separate the bulk of the Vβ array from the first Dβ segment on the 3’ side (separation of 250kb) as well as from the first Vβ segment, Vβ1 located at the 5’ end of the locus (Figure 4A).

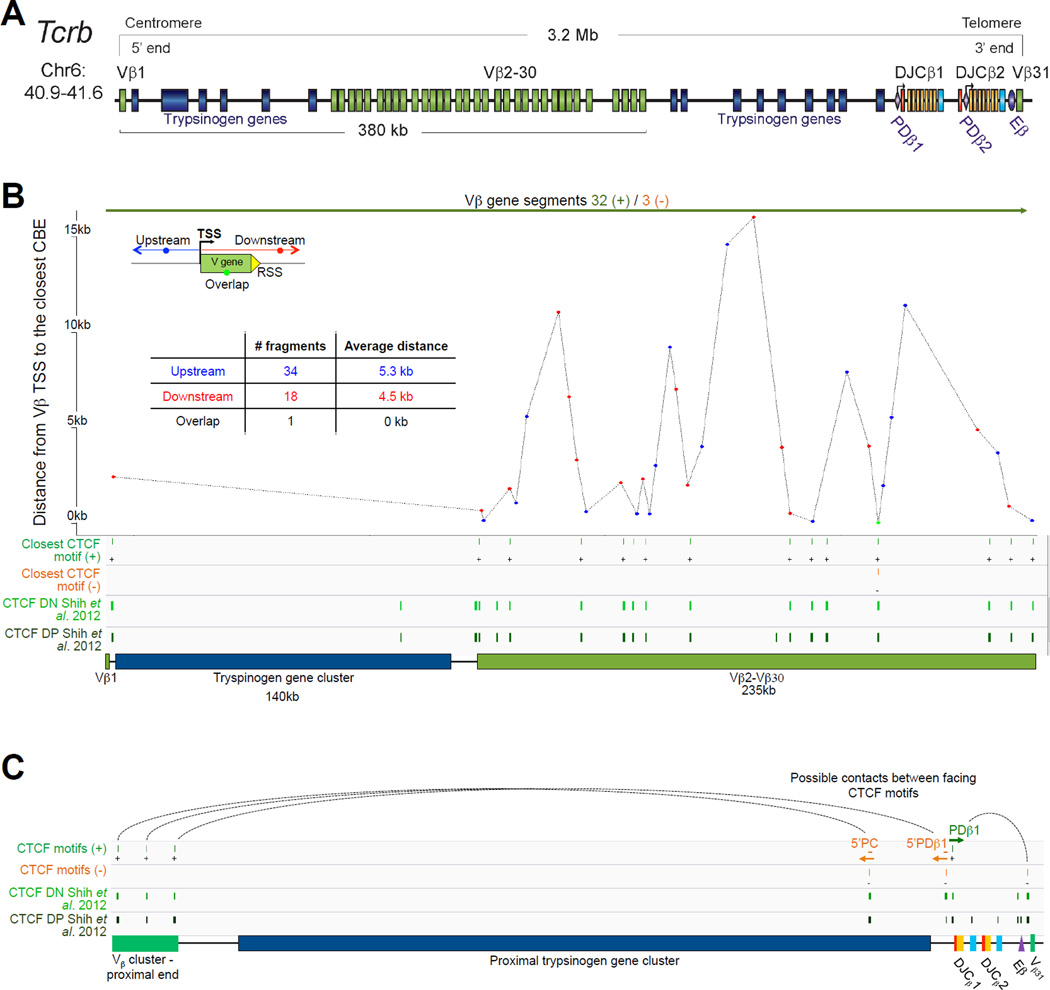

Figure 4.

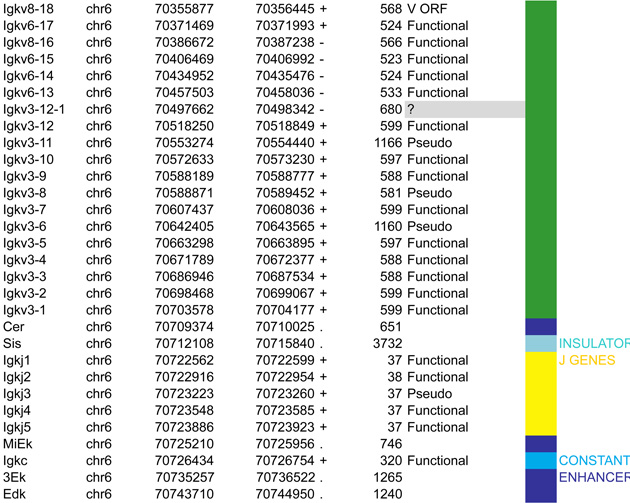

A. Tcrb linear structure and its cis acting regulatory elements. Tcrb encompasses 700kb on the murine chromosome 6. It contains 35 Vβ gene segments (22 functional) spread out over 624kb, with the exception of Vβ31 that is localized at the 3’ end of the locus in an inverted orientation. All the other segment of the locus follow a (+) strand orientation. The proximal domain is duplicated with a total of 2 Dβ, 14 Jβ (11 functional) and 2 Cβ gene segments. Two clusters of trypsinogen genes separate the bulk of Vβ genes from the first Dβ segment on the 3’ side (separation of 250kb) as well as from the Vβ1 segment located at the 5’ end. B. CTCF binding element (CBE) distribution along Tcrb Vβ gene segments (excluding Vβ31). Closest CTCF binding motifs from the TSS of each Vβ gene segment were called using CTCF peaks from DN cells ChIP-seq data (Shih et al., 2012). The Vβ cluster harbors 21 closest CBEs. 33 of the 35 Vβ segments are associated to CTCF motifs in the same orientation ((+) orientation for Vβ1 to Vβ30; (−) orientation for Vβ31). Motifs associated with Vβ1 to Vβ30 point towards the 3’ end of the Tcrb locus and could establish contact with the facing motif in the 5’PDβ1 region. The average distance between a Vβ segment and its closest CTCF motif is around 5kb with no relationship to upstream or downstream localization of the motif. C. Zoomed in region of the proximal domain of Tcrb to highlight the orientation of CBEs. The CTCF motif associated to PDβ1 (+) is facing the 3’ end motif (−) located between Eβ and Vβ31. In contrast, the 5’PDβ1 and 5’PC (5’Prss2-CTCF) motifs (−) face motifs located at Vβ segments (+). This is one more example where the region between the V array and the proximal domain harbors a composite element containing CTCF motifs pointing away from each other towards the 5’ end and the 3’ end of the locus.

2.4 Tcra

As mentioned above the most striking feature of the Tcra locus is that Tcrd is embedded within it and the two loci share a subset of V genes (Figure 5A). The whole locus spans 1.6Mb in the 129 mouse strain and 2.0Mb in C57BL/6. These differences stem from repeat regions within the V gene cluster of which there are two in strain 129 and three in C57BL/6. The Tcrd locus (which is located between the Vα and Jα gene segments of Tcra) harbors two Dδ, two Jδ genes and one Cδ gene segment. There are 5 Vδ specific genes located in the 3’ unique Vα cluster and a single Vδ gene in reverse orientation that is located downstream of Cδ (Vδ5) adjacent to the Jα array that is comprised of 60 gene segments.

Tcrd rearrangement occurs in DN cells prior to Tcra rearrangement in DP cells. This order is important because the first round of Tcra rearrangement deletes the Tcrd gene. Unlike the other loci that contain D gene segments (Igh and Tcrb) Tcrd is not subjected to ordered rearrangement. Thus Vδ-to-Dδ and Dδ-to-Jδ rearrangement occur at the same time, which enables Dδ gene segments to recombine together to form DDδ gene rearrangements (Monroe et al., 1999). Tcrd makes use of only a subset of V gene segments including several Tcrd specific V genes (TRDV1, TRDV2-1, TRDV2-2, TRDV4, TRDV5) and some V gene segments that are shared with Tcra (TRAV21/DV12, TRAV13-4/DV7, TRAV6-7/DV9, TRAV4-4/DV10, TRAV14D-3/DV8, TRAV16D/DV11, and four members of the TRAV15/DV6 family) (Hawwari and Krangel, 2005). TRDV4 rearranges specifically in fetal thymocytes and is repressed in adult thymocytes by constitutively high levels of a suppressive modification, H3K9me2 (Hao and Krangel, 2011). The local accessibility of Vδ gene segments determines which genes undergo rearrangement in DN cells and a recent study showed that replacing the promoter of a Tcra specific Vα gene, TRAV12 with the TRAV15/DV6 promoter increases the usage of the TRAV12 in Tcrd recombination (Hao and Krangel, 2011; Naik et al., 2015). Tcra recombination occurs after Tcrd recombination in DP cells and it has recently been shown that IL-7 signaling contributes to the control of stage specificity by preventing premature Tcra rearrangement in DN4 cells (Boudil et al., 2015).

3. NUCLEAR ORGANIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON ACCESSIBILITY

With the exception of the stages in development where they recombine, antigen receptor loci are by default inaccessible to the RAG proteins. Opening up of the loci for rearrangement occurs at multiple levels including DNA demethylation, activation of chromatin, initiation of sense and antisense germline transcription, nucleosome repositioning, relocation of the loci from inaccessible repressive nuclear locations (peripheral lamin associated domains or pericentromeric heterochromatin) to accessible euchromatin, and locus contraction (which brings distal V gene segments into close physical contact with the proximal DJC domain enabling recombination between widely separated gene segments) as reviewed in (Chaumeil and Skok, 2013; Hewitt et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2010). All of these changes are regulated by lineage and stage specific activation of cis regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers, chromatin insulators and others) that recruit transcription factors and structural proteins such as CTCF and cohesin that orchestrate changes which promote ordered recombination within each locus as outlined in §4. In this section we focus on changes in nuclear organization that occur during rearrangement.

3.1 Subnuclear localization

DNA FISH analyses by our lab and others revealed that there are links between the location of antigen receptor loci and their activation status. The first study to demonstrate that the proximity of a gene relative to the nuclear periphery is reflective of an inactive state focused on the immunoglobulin loci (Kosak et al., 2002). Igh alleles are located at the nuclear periphery in T lineage cells and they move inwards just prior to the onset of recombination at the pro-B cell stage. Further detailed analysis revealed that in pre-pro-B cells and T lineage cells the locus is anchored at the periphery through its 5’ VH gene segments while the 3’ end, containing the DHJHCH cluster of gene segments is more centrally located. This orientation is compatible with DHJH segments having access to euchromatically located recombinase enzymes and rearrangement being restricted to DH and JH gene segments in both these cell types (Figure 6) (Fuxa et al., 2004). Peripherally located VH gene segments are refractory to RAG and do not get recombined in these cells.

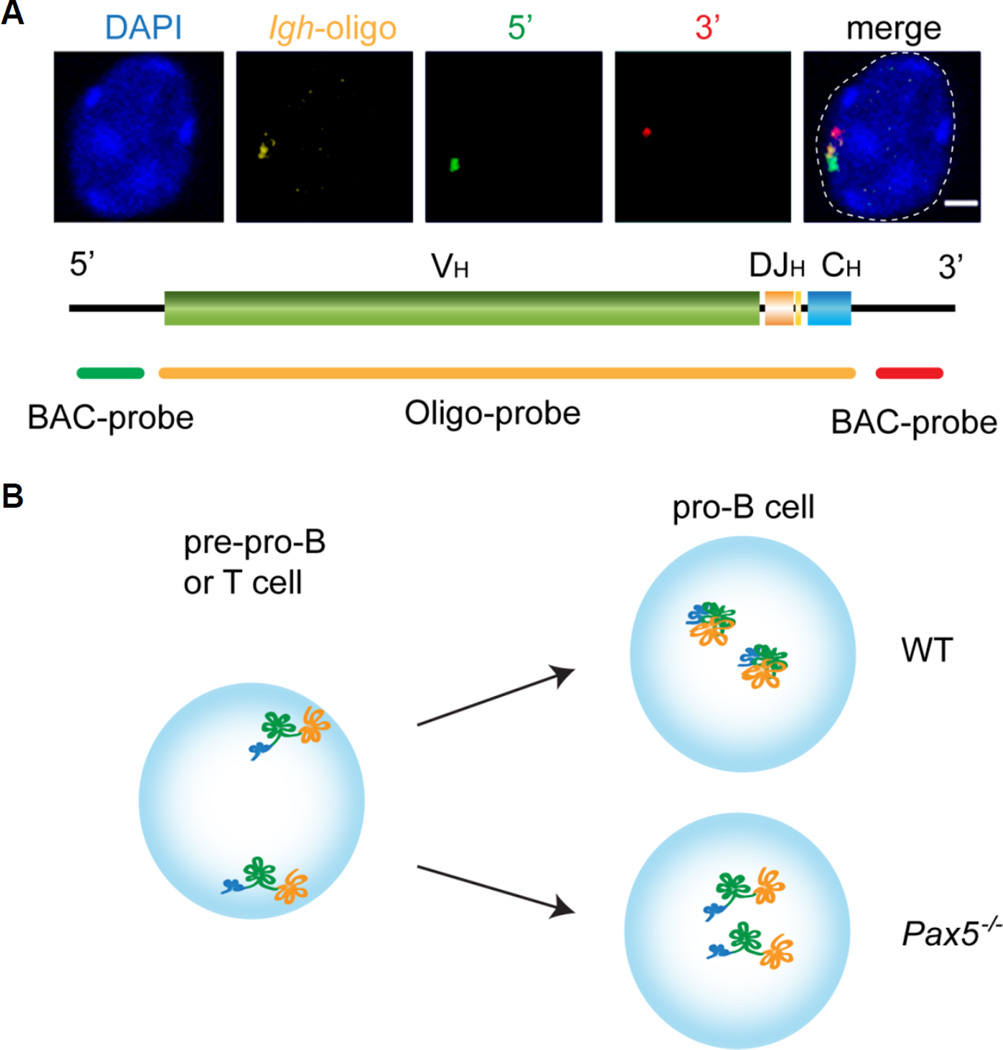

Figure 6.

The Igh locus is activated by a two step mechanism that involves relocation to the center of the nucleus and Pax5-mediated locus contraction at the time of recombination in Pro-B cells. A. 3D DNA FISH showing the location of the Igh locus and its orientation at the nuclear periphery when it is in a decontracted state. A probe scheme is shown below the FISH images identifying the location of 5’ and 3’ BAC probes relative to an oligonucleotide probe that covers the entire Igh locus. B. Scheme showing the two-step activation of Igh.

3.2 Locus contraction

The antigen receptor loci all occupy large expanses of DNA ranging from 1Mb (Tcrb) to over 3MB (Igk) that mostly encompass V gene segments. This presents a logistical problem since rearrangement requires the formation of a synapse between recombining regions that can be widely separated on the linear chromosome. The first 3D DNA FISH analyses of antigen receptor loci in developing lymphocytes revealed that the Igh locus is in an extended position in lymphocyte progenitors and non-B cells and that in recombining cells it is in a contracted conformation (Fuxa et al., 2004; Kosak et al., 2002). This is also the case for the Igk, Tcrb and Tcra loci, however unlike the other antigen receptor loci, Igk is contracted in pro-B cells, the stage prior to recombination, which may be a reflection of the fact that Igk can undergo low-level recombination in these cells (Roldan et al., 2005; Skok et al., 2007). In all cases, locus contraction brings widely dispersed V gene segments into contact with the proximal DJC domain through chromatin looping to provide every V gene an equal opportunity to rearrange. However, it should be noted that other factors, such as RSS sequence, chromatin status and transcriptional activity also influence which V gene is targeted for recombination.

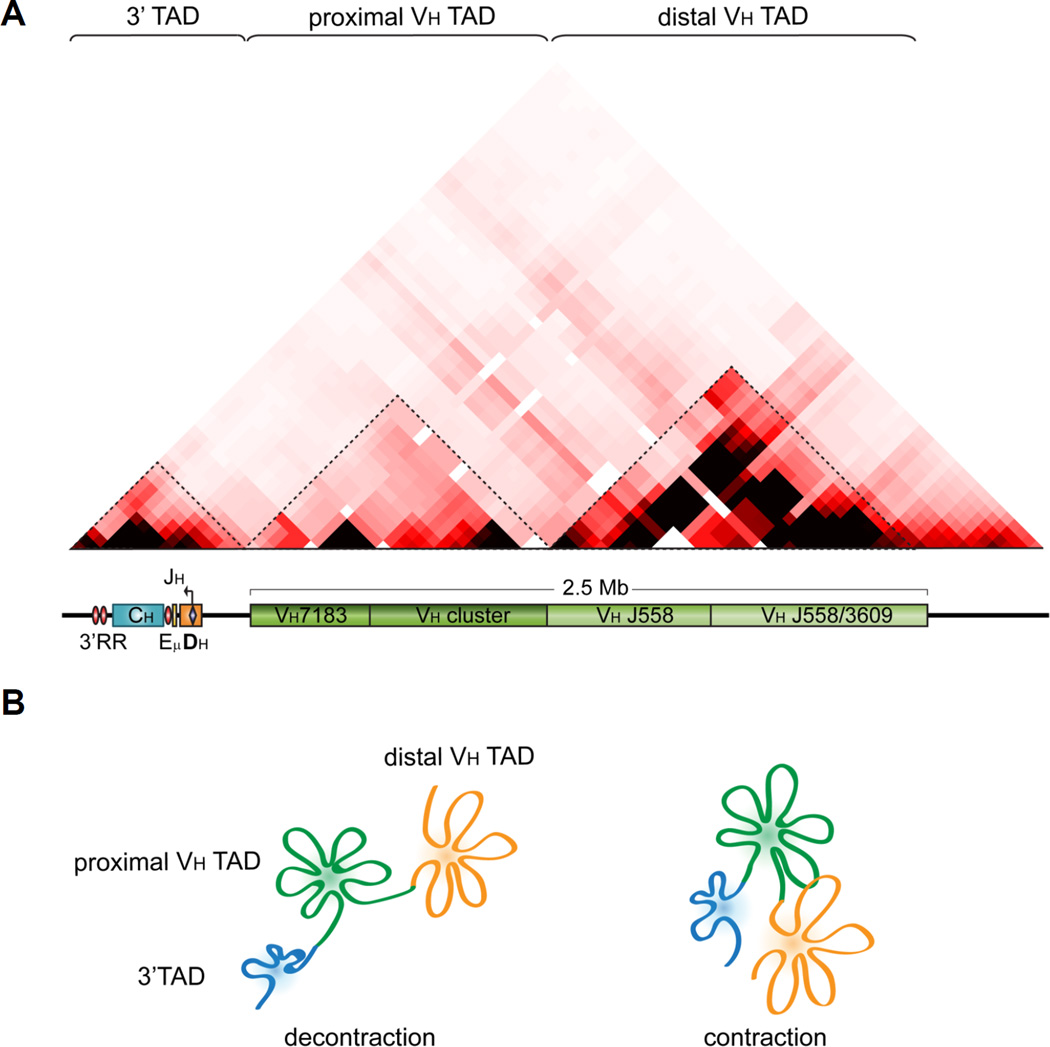

Detailed FISH analysis by the Murre lab investigating loop formation of the Igh locus used multiple small probes combined with mathematical modeling to reveal that the VH genes of the Igh locus are folded into two one megabase rosette-like structures that are connected by linkers. The rosettes are separated from each other in pre-pro-B and T cells consistent with a decontracted state and they interact with each other in pro-B cells when the locus is contracted (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2008). The rosettes are compatible with TAD structures that were defined four years later as a result of Hi-C chromosome conformation analyses that analyze interactions between everything and everything (Dixon et al., 2012; Nora et al., 2012; Sexton et al., 2012). TAD structures are highly self-interacting regions that are separated by distinct boundaries. 5C analyses performed in the Skok lab delineates two distinct TADs for the proximal and distal VH gene domains that are consistent with the Murre labs findings and with a separation of their regulation (Figure 2B and 7) Contraction – or inter TAD association – is a reversible process and once recombination has taken place the loci are once again found in a decontracted conformation. This is discussed in more detail in the context of allelic exclusion (see §5).

Figure 7.

Locus contraction of the Igh locus involves interaction of two TADs or rosette structures that encompass the VH gene region. A. Scheme showing the various gene segments of the Igh locus relative to a 5C matrix of Igh interactions in DP cells (unpublished BH and JS). B. Scheme showing rosette like structure of the Igh locus as identified by DNA FISH analyses (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2008).

Most of the early work focusing on understanding the mechanisms underlying locus contraction centered on the Igh locus, in part because the B cell specific transcription factor, Pax5 was the first factor to be identified as essential for altering locus conformation. Pax5 is upregulated at the pro-B cell stage after the initiation of DH-to-JH rearrangement, which starts at the earlier pre-pro-B cells stage (Fuxa et al., 2004). In the absence of Pax5, the two Igh alleles are found in an extended form in the center of the nucleus (Fuxa et al., 2004) and in this conformation only the 4 most proximal VH genes out of a total of nearly 200, can undergo recombination, underlining the importance of this process in generating antibody diversity (Roldan et al., 2005). Pax5 is essential for mediating contraction in B cells. However, ectopic expression of this factor in T cells cannot induce a change in locus conformation although it does have an impact on relocalizing the two alleles from the periphery to the center of the nucleus (Figure 6). These findings indicate that another, yet unidentified, factor that is present in B cells but not T cells, is required for contraction (Fuxa et al., 2004). Relocation to the center of the nucleus in T cells ectopically expressing Pax5 likely occurs as an indirect effect of Pax5 on upregulating another B cell specific transcription factor, EBF.

Based on these observations we put forward a two-step model for Igh activation (Figure 6) (Roldan et al., 2005). In lymphoid progenitor cells the Igh locus is found in an extended conformation and is anchored at the nuclear periphery via its 5’ end. The central more accessible location of the DHJH segments is compatible with DH-to-JH rearrangement occurring at low levels in T cells as previously reported (Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Kurosawa et al., 1981). Upregulation of EBF early in B cell development induces relocation of Igh to the center of the nucleus, which increases DH-to-JH rearrangement and allows VH-to DJH recombination involving proximal VH genes. Distal VH gene rearrangement is not possible when the locus is in an extended conformation and thus Pax5 expression at the pro-B cell stages is required for inclusion of these segments in the antibody repertoire.

No lineage and stage specific factors have been identified as essential for locus contraction of Igk, Tcrb or Tcra. However, ubiquitously expressed YY1, which has been shown to be important for Igh locus contraction (Liu et al., 2007a; Medvedovic et al., 2013), has also been identified as important for mediating Igk contraction (Liu et al., 2007a; Pan et al., 2013). Furthermore, CCCTC-binding factor, CTCF and its binding partner cohesin also play important roles, as reviewed in (Chaumeil and Skok, 2012) and discussed in more detail below.

3.3 Allelic pairing and pericentromeric localization

Accessibility of antigen receptor loci has been linked to proximity to a second repressive compartment of the nucleus, pericentromeric heterochromatin (PCH). The Fisher lab was the first to show that transcriptionally inactive genes localize to pericentromeric heterochromatin in developing T cells (Brown et al., 1999) and subsequent studies led to the discovery that productively rearranged and non-productively rearranged Igh alleles are found in distinct nuclear compartments in mature activated B cells (Skok et al., 2001). Differences in nuclear localization of highly expressed productively rearranged versus low expressing non-productively rearranged alleles led to the idea that repositioning to pericentric regions could play a role in allelic exclusion (Roldan et al., 2005; Skok et al., 2007). Indeed it does, but not surprisingly this turns out to be just one aspect of control. In the case of the antigen receptor loci, pericentromeric localization is linked to homologous and heterologous antigen receptor allele pairing, which in turn is linked to control of allele and locus specific accessibility ensuring that breaks are introduced asynchronously on one allele or locus at a time.

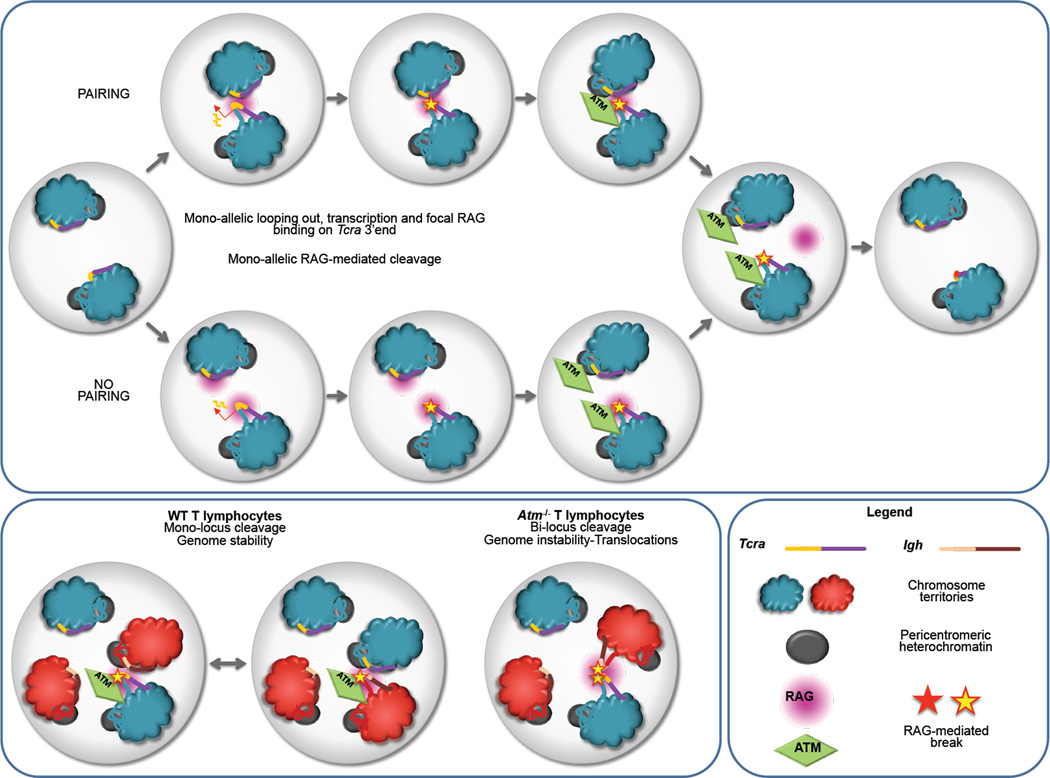

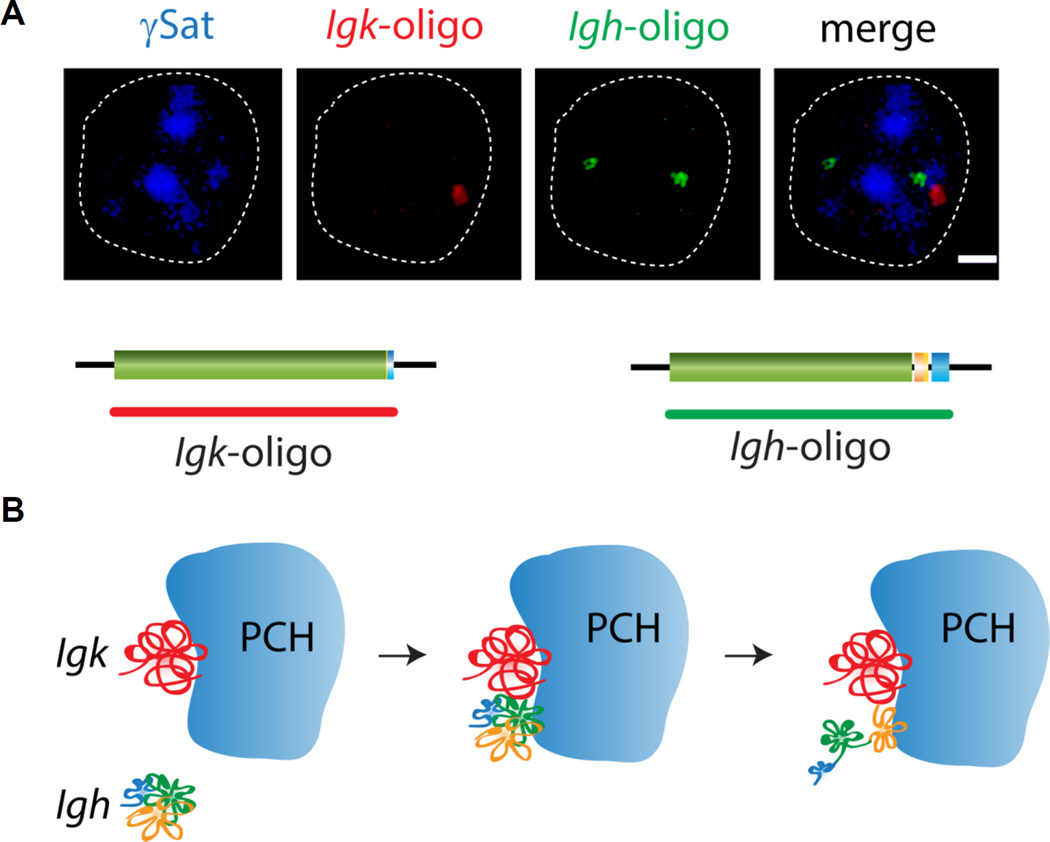

Briefly, we discovered that RAG proteins enhance association of recombining homologous and heterologous loci in euchromatic regions of the nucleus. Pairing is mediated by RAG induced higher-order looping of one allele away from its respective chromosome territory. RAG-mediated cleavage is targeted to the looped out allele and once the break is introduced the DNA damage sensing factor, ATM (ataxia telengiectasia mutated) is recruited in cis to the site to initiate repair. Both the C-terminal portion of RAG2 and ATM perform the same function and act in trans on other recombining alleles (homologues) or loci (heterologues e.g. Igh and Tcra) repositioning them to PCH and inhibiting further higher-order loop formation (Figure 8). This may be part of the mechanism that serves to prevent further cleavage until repair of the first break is completed (Chaumeil et al., 2013a; Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Chaumeil and Skok, 2013; Hewitt et al., 2009). Together these data support a model in which breaks occur on paired alleles, however since allelic association is likely transient and cleavage a rapid event with repair occurring over several hours, it is not surprising we find repair foci on both paired and unpaired alleles. Given these observations our model is difficult to prove without a live imaging system that can track these events over time.

Figure 8.

Model of ATM-mediated control of cleavage. Changes in nuclear accessibility of the antigen-receptor loci are linked with mono-allelic and mono-locus rearrangement and maintenance of genome integrity.

Is pairing necessary for this level of control? We hypothesize that pairing is required for cleavage as well as feedback control of cleavage as close proximity could be important for coordinating trans control by ATM and the C-terminal portion of RAG2. Although RAG is found in abundance in euchromatic regions of the nucleus and is enriched at H3K4me3 marked chromatin (Ji et al., 2010), RAG-mediated cleavage is inherently inefficient (it would be dangerous if it were any other way) as RAG-mediated breaks are only detected in around 20% or less of recombining cells as determined by immuno-FISH analyses of breaks (Chaumeil et al., 2013a; Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Hewitt et al., 2009). It is thus not inconceivable that the chance of a break occurring improves as the local concentration of RAG increases. However, it could be argued that increasing the local concentration of RAG in recombination centers via association of RAG bound genes (Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Chaumeil and Skok, 2013) would increase the risk of cleavage on closely associated loci. Not so, if feedback control of RAG cleavage via an ATM-mediated mechanism occurs in a localized fashion (Figure 8).

Support for this idea comes from feedback control of Spo-11p mediated cleavage during meiosis: ATM appears to play a similar role in regulating the introduction of breaks in this process, however it is clear that cleavage control occurs in a localized fashion in meiosis (Garcia et al., 2015; Lange et al., 2011). Since feedback control of recombination appears to be conserved in meiosis and V(D)J recombination it likely shares common mechanistic features, the details of which have yet to be worked out. In both cases feedback control of cleavage is important for maintenance of genome stability and in the case of V(D)J recombination, asynchronous cleavage provides a means of (i) maintaining genome instability and preventing the generation of translocations and (ii) initiating allelic exclusion, ensuring that both alleles are not rearranged at the same time which could lead to the generation of two productively recombined alleles (discussed in §5 below).

3.4 Igk-Igh allelic pairing and its impact on Igh locus contraction

A further example of pairing linked to PCH localization comes from a transient interaction between Igh and Igk that occurs at the pre-B cell stage of development (Hewitt et al., 2008). We discovered that association of one Igk allele with one Igh allele at PCH triggers (i) the repositioning of Igh to PCH and (ii) Igh locus decontraction. This serves to (i) reduce accessibility of partially recombined (DJH rearranged) Igh alleles that could otherwise go on being rearranged in pre-B cells, and to (ii) prevent ongoing mid and distal VH rearrangement occurring during light chain rearrangement. Inter-locus Igk-Igh pairing and Igh decontraction rely on the 3’Eκ Igk enhancer: in its absence there is reduced Igk-Igh pairing, reduced Igh localization at PCH and Igh remains in a contracted conformation increasing the level of mid and distal VH rearrangement detected in pre-B cells (Figure 9) (Hewitt et al., 2008). Intriguingly, the intronic enhancer of Igk, MiEκ, has an antagonistic effect on Igk-Igh pairing, Igh localization at PCH and decontraction which are all increased in its absence in association with reduced levels of mid and distal VH rearrangement in pre-B cells (Hewitt et al., 2008). Stopping ongoing rearrangement of Igh at the pre-B cell stage is important because a second productively rearranged Igh allele could potentially violate allelic exclusion.

Figure 9.

An interaction between Igk and Igh is responsible for Igh PCH association and Igh locus decontraction post recombination, at the pre-B cell stage. A. 3D DNA FISH showing the Igk-Igh interaction at PCH in pre-B cells. Oligonucleotide probes encompassing the entire Igk and Igh loci were used for this analysis. B. Scheme showing Igk-Igh interaction at PCH leading to Igh locus decontraction.

4. CIS ACTING ELEMENTS THAT CONTROL ACCESSIBILITY AND RECOMBINATION

In this section we aim to highlight functions of cis acting elements and their role in regulating accessibility, locus conformation and ordered recombination. In particular we will focus on the most recent work identifying regulatory elements that play an important role in all of these aspects of control. All of these elements are depicted in Figures 2–5. In particular, in these figures we have focused on CTCF binding elements, (CBEs) as these are an important component of long range interactions. For all loci we have analyzed the orientation of the CBEs as a recent study demonstrates that loop bases involve a pair of CTCF sites in a head to head orientation (Rao et al., 2014), and it is possible that the directionality of the CTCF sites determines who interacts with whom. In addition we analyzed the location of the closest CBE relative to the TSS of each V gene and have marked whether these are upstream, downstream or overlapping with it and whether there is any pattern to this organization on the individual loci. Segment annotations with coordinates, strand orientation and functional status as well as coordinates for regulatory elements are provided in Table 1. Annotations were collected from NCBI (Igh gene ID: 111507; Igk gene ID: 243469; Tcrb gene ID: 21577; Tcra Gene ID: 21473) and IMGT/LIGM-DB databases (Giudicelli et al., 2006) using the mm10 genome build that uses the C57BL/6 strain as the reference genome.

Table 1.

4.1 Important cis acting elements and their function in Igh rearrangement

4.1.1 The intronic enhancer Eμ

The intronic enhancer Eμ, located in the 700kb region that separates the JH and the CH clusters is a combination of a 220bp core enhancer element (cEμ) and two 310–350bp flanking matrix attachment regions (MARs). Deletion of Eμ has been shown to impair both DH to JH and VH to DJH recombination. In Eμ knockout mouse models, sense μ0 (initiated at the DHQ52 region), lμ transcripts (which originate 3’ of the Eμ core (Lennon and Perry, 1985; Perlot et al., 2005) and antisense transcripts in the JH and DH regions (Afshar et al., 2006) are severely impaired. However, despite the defect in V(D)J recombination and a partial block in B cell development at the pro-B cell stage, Eμ deletion (core or full length) does not severely affect germline sense or antisense transcription in the VH region or VH gene usage (Afshar et al., 2006; Perlot et al., 2005). Moreover, this enhancer does appear to be important for efficient Igμ-chain expression and strong signaling through the pre-BCR and BCR (Marquet et al., 2014)

4.1.2 The 3’ regulatory region

The 3’ regulatory region (3’RR), located 200kb downstream of the CH cluster, spans 30kb and contains multiple enhancer elements with strict B-lineage specificity (HS3a, HS1–2, HS3b and HS4) and a proposed insulator region containing CTCF binding sites (HS5, 6, 7 and 8) which also bind cohesin and likely act as a Igh 3′ chromatin boundary (Degner et al., 2011; Garrett et al., 2005). These hypersensitive sites mostly show occupancy by transcription factors in mature B cells as this enhancer is not implicated in V(D)J regulation but controls CSR and somatic hypermutation, which take place in mature germinal center B cells after encounter with antigen (Khamlichi et al., 2000; Pinaud et al., 2011; Rouaud et al., 2013). In line with its role in these late events, the binding profile of Pax5 to the 3’RR is altered during CSR leading to enrichment on HS1–2, HS4 and HS7 (Chatterjee et al., 2011).

4.1.3 PAIR elements

The Busslinger lab identified 14 PAIR elements (Pax5-Activated Intergenic Repeats), within the distal VH region that contain functional CTCF, E2A and Pax5 binding sites (Ebert et al., 2011). 11 out of the 14 PAIR elements are found immediately upstream of VH3609 genes interspersed within the distal VHJ558 gene family. Detailed investigation of PAIRS 4, 6 and 7 demonstrate binding of Pax5, E2A and CTCF in pro-B cells. In contrast, at the later pre-B cell stage there is depletion of Pax5 at these sites (Ebert et al., 2011). Pax5 binding at the pro-B cell stage correlates with the presence of antisense transcripts, that are distinct from those identified by the Corcoran lab (Bolland et al., 2004). These PAIR elements are implicated in locus contraction since Pax5 binding at the pro-B cell stage coincides with contraction, and Pax5 depletion in pre-B cells corresponds to a decontracted state (Roldan et al., 2005). It is of interest that neither of the Igh enhancers (Eμ and the 3’RR region) or the IGCR1 insulator site have any impact on locus contraction, suggesting that only elements within the VH cluster are required (Medvedovic et al., 2013). The involvement of PAIRs in Igh contraction will need to be confirmed with genetic approaches that target these elements.

4.1.4 The intergenic control region 1 (IGCR1)

The intergenic control region 1 (IGCR1) is located within a 100kb-long intergenic region, which separates the VH and DH gene segments of Igh. It spans 4.3kb and lies between VH81× (Ighv5-1) and DFL16.1 (2.1kb upstream of DFL16.1 also named Ighd1-1). IGCR1 consists of six hypersensitive (HS) sites (HS 1 to 6). Two conserved CTCF binding sites, HS4/5 that exhibit enhancer blocking activity, mark a sharp boundary of antisense transcription that stops at least 40kb from the VH genes (Featherstone et al., 2010). In T cells and early pre-pro-B cells undergoing DH-JH rearrangement, the two CTCF sites separate regions of active and inactive chromatin in the DH and VH regions, respectively. Antisense transcription, which occurs at high level within this region in these cells is reduced in pro-B cells where VH-DJH recombination takes place. Thus, it was proposed that the two CTCF sites act as an insulator preventing the spreading of chromatin activation and transcription into the VH region during DH-JH rearrangement (Featherstone et al., 2010).

Deletion of the 4.1kb fragment (named the IGCR1) encompassing both CTCF binding elements (CBE1/2) alongside potential binding sites for other regulators (YY1 and PU.1) demonstrated that mutant alleles in a RAG deficient background were indeed associated with upregulation of proximal VH7183 and VHQ52 transcripts and an enrichment of active histone marks in pro-B cells. Increased accessibility/transcription of proximal VH genes is linked to preferential rearrangement of VH7183 and VHQ52 at the expense of distal VHJ558 gene rearrangement in recombination competent IGCR1 targeted cells. Furthermore, mutant CBE alleles can undergo VH-DH rearrangement prior to DH-JH rearrangement, indicating a role for these elements in regulating ordered rearrangement (Guo et al., 2011). Additionally, mutant Igh alleles can undergo VH-DJH recombination in developing thymocytes, in contrast to wild-type counterparts which normally only undergo DH-JH rearrangement. Thus the two CBE sites have a role in regulating lineage specific, ordered rearrangement as reviewed in (Chaumeil and Skok, 2012).

In more recent studies the Alt lab extended their analysis of the CBE sites by scrambling each element to separately assess their individual contributions to these processes (Lin et al., 2015). They demonstrate that scrambling of CBE1 but not CBE2 impacts allele expression such that in F1 mice harboring a 129 IgMa CBE1 mutated allele and a C57BL/6 IgMb WT allele, resulting B cells were found to express half as many IgMa compared to IgMb alleles. However, this defect was much more severe in F1 mice if both CBEs were mutated simultaneously. In line with their previous findings (Guo et al., 2011), mutation of either CBE1 or CBE2 led to a decrease in distal VH gene rearrangement but this defect was more pronounced in CBE1−/− mice. Double CBE1/CBE2−/− mice however had the most severe defect.

These mutant mice also display defects in ordered rearrangement such that direct VH-to-DJH joins were detected in CBE1−/− mice and variably in CBE2−/− mice, but again this was most pronounced in the double CBE1/CBE2−/− mutants. Finally, mutant CBE1 and 2 mice displayed low levels of proximal VH-to-DJH rearrangements in T cells but lineage inappropriate rearrangement was much more severe in the double CBE1/CBE2−/− mice. No defects in allelic inclusion were observed in any of the three mutant mice. However, in line with what was previously observed in the double CBE1/CBE2−/− mutant mice (Guo et al., 2011), the presence of a productively rearranged V1–8 knockin allele did not suppress proximal VH-to-DJH rearrangement. These rearrangements were detected in spleen on CBE2−/− alleles but more so on CBE1−/− alleles, however they were predominantly non-productive. No distal VH gene rearrangements were observed likely because locus contraction was impaired as we previously showed in mice harboring a rearranged transgene that skip past the pro-B cell stage of development (Roldan et al., 2005).

Together these studies indicate that CBE1 has a more pronounced effect on ordered rearrangement and feedback control than CBE2 and the Alt lab suggest that this could be explained in two ways. First, CBE1 contains binding sites for PU.1 and YY1 and the presence of these binding sites could impact these functions. Second, and more interesting is the observation that the orientation of the CTCF site within CBE1 is in the opposite direction to the 60 VH CTCF sites, while the CTCF site within CBE2 is in the opposite orientation to the 10 3’ CTCF sites (Figure 2), with the implication that CBE2 interacts with the 3’RR region, promoting DH-to JH rearrangement and inhibiting direct VH-to-DJH joins. CBE1 on the other hand could interact with CBEs in VH genes. It is of note that deletion of both CBE1/2 sites does not alter locus contraction as determined by 4C-seq from the Eμ viewpoint, that measures interactions specifically with this region alone (Medvedovic et al., 2013). However, there has been no 4C-seq analyses from the viewpoint of CBE1/2 so we do not know what impact combined or individual deletion of these CTCF insulator sites has on surrounding interactions, and whether the change in chromatin boundaries that accompanies their deletion is matched by a change in interaction boundaries, as shown by us in the Hoxa locus (Narendra et al., 2015). A detailed analysis of looping in wild-type versus mutant CBE1 and 2 B cells could help resolve these issues. Furthermore, it would be interesting to find out what effect reversing the orientation of the two CBE sites has on regulation of the Igh locus.

4.2 Important cis acting elements and their function in Igk rearrangement

4.2.1 Enhancers

Igk possesses three powerful B cell-specific transcriptional enhancers: the matrix attachment region (MAR) and the intronic enhancer, iEκ, (together known as the MiEκ) are located between the Jκ and Cκ gene segments while two additional enhancers, 3'Eκ and Edκ, are found 8.5kb and 15.5kb downstream of the constant region (Liu et al., 2002; Meyer et al., 1990; Zhou et al., 2010). MiEκ and 3’Eκ are both important for rearrangement and deletion of either one leads to a reduction in the ratio of κ/λ expressing B cells, while the double mutant is sufficient to abrogate Igk recombination altogether (Inlay et al., 2002; Inlay et al., 2006). In contrast, an absence of both the 3’Eκ and Edκ leads to a dramatic reduction in germline and rearranged transcription, a reduction in active chromatin marks, increased DNA methylation and reduced levels of rearrangement. Furthermore, in mature cells IGλ is exclusively expressed on the cell surface despite functional rearrangement of Igk. This indicates that in the absence of both the 3’Eκ and Edκ the intronic enhancer is incapable of triggering Igk transcription (Zhou et al., 2010). Conditional knockout of the 3'Eκ in mature cells with an Edκ deletion leads to complete silencing of the Igk locus (Zhou et al., 2013). In these mice the mature B cells partially dedifferentiate, inducing RAG1/2 expression along with other pro-B cell makers and re-differentiate after triggering Igl gene rearrangement. These findings demonstrate that 3’Eκ and Edκ are essential for both the establishment and maintenance of transcriptional activity of Igk.

4.2.2 Promoters that influence Jκ usage

Igk germline transcription is initiated from two promoters located 150bp (proximal) and 3.5kb (distal) upstream of Jκ1 that give rise to the κ0 transcripts (Schlissel, 2004) (Figure 3). The κ0 0.8 and κ0 1.1 germ line transcripts are initiated from the proximal and distal promoters respectively and spliced to the Cκ region (Engel et al., 1999; Martin and van Ness, 1990). Germline transcription from these promoters is linked to rearrangement, and deletion of a 4kb region encompassing the two promoters has a marked impact on rearrangement of the allele bearing the deletion (Cocea et al., 1999). Recent studies from the Schlissel lab demonstrate a role for the proximal promoter in directing primary rearrangements to Jκ1, thereby ensuring the retention of other Jκ segments that can be used in subsequent rounds of recombination for receptor editing. They show that the distal but not the proximal promoter is active in both recombining and editing cells. Deletion of the proximal promoter leads to increased breaks on Jκ2 and decreased usage of Jκ1 and this correlates with an increase in H3K4me3 levels and transcription in the Jκ1 region. Thus the proximal promoter acts as a suppressor of accessibility and secondary recombination. Since it is inactive in recombining B cells the Schlissel lab propose that it could be a result of promoter interference that is also found in Tcra where the active TEA suppresses activity of downstream Jα promoters (Abarrategui and Krangel, 2006, 2007).

4.2.3 Sis and Cer

Two additional regulator elements within Igk, Sis - hypersensitivity sites 3–6 (HS3–6) and Cer -hypersensitivity sites 1–2 (HS1–2), reside in the 18kb intervening Vκ-Jκ sequence (Liu et al., 2002). Sis (Silencer in the Intervening sequence) is a recombination silencer and heterochromatin targeting element. It binds both Ikaros and CTCF and directs the repositioning of Igk to PCH in pre-B cells (Liu et al., 2006). Deletion of Sis leads to reduced distal Vκ and enhanced proximal Vκ usage (Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2011; Xiang et al., 2011). The neighboring CTCF binding site, Cer (Contracting element for recombination) plays a role in Igk locus contraction (Xiang et al., 2013). Like Sis, deletion of Cer increases proximal and diminishes distal Vκ usage although it has no impact on germline transcription or chromatin. Additionally, an absence of Cer leads to rearrangement of Igk in T cells. This is somewhat surprising since, unlike Igh, there is no evidence for Igk activation in T cells. Double deletion of both Cer and Sis gives rise to increased transcription of proximal Vκ in both pre-B and splenic B cells (Xiang et al., 2014). In this respect Cer and Sis behave in a similar manner to the CTCF binding elements, CBE1/2 in the Igh locus, although mutation of the IGCR1 does not appear to impact Igh locus contraction as determined by 4C-seq (Medvedovic et al., 2013) (see §4.1.3 above), while in contrast DNA FISH analyses of Igk alleles with deleted Cer (or double deleted Cer and Sis) demonstrate a dramatic effect on Igk contraction (Xiang et al., 2013, 2014). It is difficult to compare the effects of the 4C-seq and DNA-FISH analyses in these two studies as neither give a complete picture of how interactions are altered across each locus in entirety. The 4C-seq analysis was performed from the Eμ viewpoint in IGCR1 mutated cells and this serves to highlight interactions from Eμ alone (Medvedovic et al., 2013) while the FISH analyses provide information on the distances separating three points on the Igk locus and offers no details of intra-locus interactions (Xiang et al., 2013, 2014).

4.2.4 Pre-BCR signaling and its impact on long-range interactions

Functional rearrangement of one Igh allele in pro-B cells leads to cell surface expression of the pre-BCR, which is comprised of IGH paired with surrogate light chain. Pre-BCR signaling in large pre-B cells drives proliferation and subsequent differentiation to the small pre-B cell stage where cells exit cell cycle and Igk rearrangement is initiated. To examine changes in Igk locus conformation by 4C–seq during the transition from the pro- to the pre-B cell stage, the Hendriks lab used pre-BCR signaling mutants of increasing severity (mice lacking Btk, Slp65 or both together) on a RAG deficient background (Stadhouders et al., 2014). These analyses revealed that pre-BCR signaling reduces interactions of the three enhancers with Igk flanking sequences and increases interactions of the 3’Eκ with the Vκ regions, without altering Vκ interactions with the MiEκ (these are already in close contact at the pro-B cell stage). It is of note that in all cases the enhancers interact more frequently with functional versus non-functional Vκs in pre-B cells. The Sis element also displays an altered interaction pattern within the Igk locus in pro-B and pre-B cells, interacting much more with the proximal domain (JκCκ) in pro-B cells compared to pre-B cells. In the latter, the interaction profile spreads to the Vκ gene region, which may be a reflection of a change in transcriptional activity although transcriptional profiles in pro-B cells are not shown in this study (Stadhouders et al., 2014). Vκ interactions correlate strongly with binding of E2A and Ikaros that are frequently found close to promoters and bind to the 3‘Eκ, MiEκ and Sis regulatory elements (Bossen et al., 2012; Kil et al., 2012; Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2011; Ribeiro de Almeida et al., 2012). Furthermore, interactions occur preferentially if both E2A and Ikaros are present together, versus Ikaros alone and the presence of both factors is linked to frequency of Vκ gene usage.

4.3 Important cis acting elements and their function in Tcrb rearrangement

4.3.1 The Eβ enhancer and promoters

Eβ is the sole known enhancer of Tcrb. It spans 550bp and is located 6kb downstream of the Cβ2 region and about 3kb upstream Vβ31 (Figure 4). Eβ facilitates activation of promoters flanking each of the two Dβ segments (McMillan and Sikes, 2008; Sikes et al., 1998). PDβ1, positioned immediately 5’ of the Dβ1 12-RSS, was the first germline Tcrb promoter discovered. It uses a TATA element situated in the RSS spacer to initiate transcription at Dβ1. PDβ1 is bound by T cell-restricted transcription factors including SP1, GATA-3, and members of the ETS, RUNX and bHLH families. Most of these factors also bind Eβ (Doty et al., 1999; Sikes et al., 1998; Tripathi et al., 2000). Deletion of Eβ or PDβ1 dramatically affects T cell development in the following way. An Eβ deficiency gives rise to a similar phenotype as RAG deficiency in terms of Tcrb rearrangement. A total absence of germline transcription in the proximal DJCβ1-DJCβ2 domain leads to a failure of Tcrb rearrangement and a block in T cell development at the DN3 stage (Bories et al., 1996; Bouvier et al., 1996). In contrast, targeted deletion of PDβ1 specifically attenuates DJβ1 rearrangement without affecting DJβ2 and V-DJβ2 rearrangements (Whitehurst et al., 1999). These phenotypes demonstrate the importance of Eβ in modulating chromatin accessibility across both DJCβ regions, while the contribution of each promoter is specifically directed towards their associated DJβ clusters.

The DJβ2 comprise two promoters, one upstream (5’PDβ2) and one downstream (3’PDβ2) of the Dβ2 segment. Analogous to PDβ1, 5’ PDβ2 is located immediately 5’ to Dβ2 and binds GATA-3, RUNX1 and E47 (McMillan and Sikes, 2009). However, PDβ2 is inactive prior to Dβ2-Jβ2 recombination. Germline transcription at the DJβ2 cluster is driven by the NFκB dependant promoter 3’PDβ2, located several hundred bp downstream of Dβ2 (McMillan and Sikes, 2008). Repression of 5’PDβ2 is ensured by USF-1, a constitutively expressed bHLH protein that binds in the spacer of the Dβ2 12-RSS. It has recently been shown that the introduction of DNA DSBs relieves the USF-mediated repression of Dβ2 (Stone et al., 2012). Following DJβ recombination, 5’PDβ2 is activated and both DJβ clusters are transcribed and can rearrange with distant Vβ genes.

Little is known about the developmental regulation of Vβ promoters. They are responsible for germline as well as rearranged transcription of Vβ elements. Similarly they are involved in regulating recombinase accessibility as deletion of the Vβ31 promoter leads to a 10 fold decrease in Vβ31 rearrangement (Ryu et al., 2004). Unlike proximal promoters, Vβ promoters do not appear to require Eβ for their transcriptional activation in DN3 (Mathieu et al., 2000). However this enhancer can increase expression of the most highly transcribed subset of Tcrb Vβ segments in DN thymocytes.

4.3.2 Long range interactions

A recent paper from the Oltz lab investigated the role of enhancers and an insulator in shaping the interaction landscape of Tcrb that is so important for ensuring diversification of the Tcrb repertoire (Majumder et al., 2015). Using 3C (one to one interaction analysis) with an anchor on Eβ they show that an absence of this enhancer leads to reduced interactions with the rest of the locus, however interactions from this view-point to the mid Vβ gene region (Vβ12–13, Vβ14, Vβ16 and Vβ20) are maintained, although the 3C signal is lower than controls. In line with contraction analyses of other enhancer deficient antigen receptor loci, the Oltz lab find that deletion or inactivation of Eβ (through introduction of mutations in RUNX binding sites) does not disrupt the interaction between Dβ clusters and the Vβ gene segments despite ablation of germline transcription and reduced H3K4me3 levels in the region. This indicates that even transcription is dispensable for long-range interactions between Vβ, Dβ and Jβ gene segments. Nonetheless Eβ could still have an impact on Vβ gene repertoire as it alters germline transcription of a subset of Vβ genes, but this is not testable because Eβ is essential for activation and recombination of the DβJβ region.

Their studies demonstrate that the promoter PDβ1 is important for interactions between the Dβ2 region and distal Vβ genes because a 3.5kb deletion impacts the 3C signal on these Vβ genes when Dβ2 is used as an anchor. This deletion also reduces CTCF levels at distal Vβ genes without impacting transcription or cohesin levels. Reduced CTCF binding may explain alterations in Vβ interaction frequency with the proximal DβJβ domain. It is of note that the PDβ1 deletion does not alter interactions from the distal Vβ5 viewpoint. In addition, proximal Vβ gene interactions with the DβJβ domain do not require the PDβ1, however interactions between proximal and distal Vβ genes do. In contrast, a minimal deletion of the PDβ1 promoter does not impact long-range Vβ to DβJβ interactions, despite its impact on Dβ1 transcription. Interactions between the distal Vβs and the DβJβ thus rely on a 3kb region just upstream of the PDβ1 promoter. However distal V gene interactions occur most robustly with the 5’Prss2-CTCF (5’PC) site, which is intact in the 3.5kb deleted promoter allele and furthermore CTCF binding is not altered at the 5’PC if this region is deleted. The 5’PC can be distinguished by a 5’ repetitive tract (which contains a viral LTR that is expressed at low levels in DN cells that harbors insulator properties) and a pair of CTCF/RAD21 binding sites. The Prss2 gene is normally inactive in WT, minimal PDβ1 deletion or Eβ mutated alleles. However it is activated if the entire 3.5kb promoter is deleted and the chromatin around the promoter region is enriched for H3K4me3. This mark spreads from the PDβ1 and PDβ2 region all the way up to the 5’PC in the PDβ1 mutant suggesting that a chromatin boundary has been disrupted. This chromatin barrier appears to be required for mediating interactions between the distal Vβ gene segments (where, in contrast to the proximal domain there is robust CTCF binding) and the PDβ region. Future studies will be required to identify the transcription factors that are involved in this interaction. Certainly, it is clear that these insulator sites are a common feature of antigen receptor loci as they are found in Tcrb, Igk and Igh. In the case of Igk and Igh, deletion of these elements increases transcription and recombination in the proximal domain, perhaps disrupting interactions with distal Vβ gene segments that have not yet been resolved with current methods of analysis (see §6.2).

4.4 Important cis acting elements and their function in Tcra/d rearrangement

4.4.1 Enhancers and promoters

There are two enhancers in the Tcra/d locus: Eδ and Eα regulate Tcrd and Tcra rearrangement, respectively (Figure 5) (Krangel, 2009). The Eδ, which is located between the Jδ and Cδ gene segments, regulates germline transcription of the promoter pDδ in the DJδ region. The Eδ functions locally in adult DN cells and its deletion Eδ reduces Tcrd rearrangement by ten fold although it does not alter accessibility of the Vδ genes (Hao and Krangel, 2011). In addition, Eδ appears to be dispensable for Tcrd expression after rearrangement (Monroe et al., 1999).

The Eα is essential for Tcra rearrangement and it also regulates expression from rearranged Tcrd alleles (Krangel, 2009; Monroe et al., 1999). Deletion of Eα blocks Tcra rearrangement and T cell development (Sleckman et al., 1997). Eα regulates a “T early α” promoter (TEAp) located just upstream of the Jα array, and this in turn activates the Jα array. Specifically the TEA promoter targets primary rearrangement at the extreme 5’ of the Jα array by opening up the RSSs of these genes (Hawwari et al., 2005). This maximizes the use of Jα segments during secondary rearrangement as use of the 3’ Jαs in the first round of rearrangement could result in deletion of intervening segments leaving few substrates for subsequent recombination events. The Eα also regulates germline transcription and accessibility of the proximal Vα genes via long-range interactions (over 500kb) (Hawwari et al., 2005). In addition, the Eα mediates interactions between the proximal Vα and Jα gene segments, which are essential for synapsis and rearrangement (Shih et al., 2012).

As with the other loci, long distance interactions between cis-elements are essential for Tcra and Tcrd rearrangement. Chromatin organizers like Cohesin and CTCF play an important role in mediating long range interactions (Seitan et al., 2011; Shih et al., 2012) and reviewed in (Chaumeil and Skok, 2012). Cohesin binds to the Tcra locus control region (LCR), the Eα enhancer, the Jα49 promoter, the TEAp, sites located between Tcrd and the first Vα segments and to Vα gene promoters in DP cells. Deletion of Rad21, one of the cohesin complex components, impairs the interaction between the Eα and TEAp, which in turn impacts activation of distal 3’ Jα genes and impairs secondary Tcra rearrangements (Seitan et al., 2011). CTCF also mediates interaction between the Eα and TEAp and binds to the proximal Vα gene promoters, which may assemble a rosette with Vα, Eα and Jα (Shih et al., 2012).

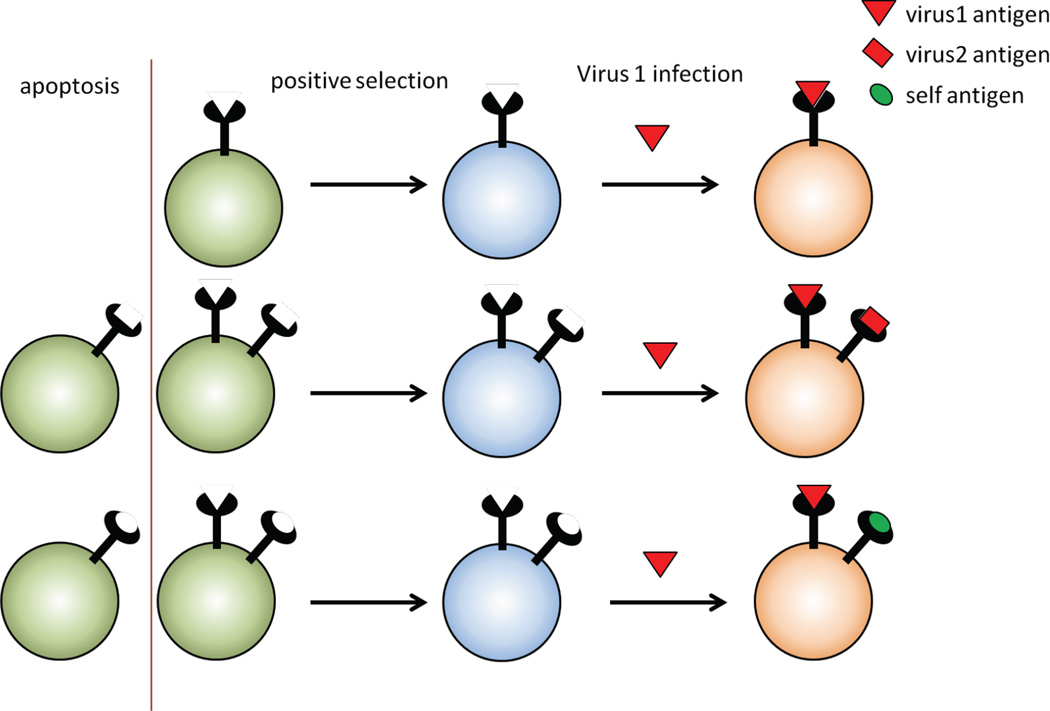

5. ALLELIC EXCLUSION

Antigen receptors are expressed from only one allele in individual lymphocytes to ensure unique receptor specificity. This is fundamental to the proper functioning of the adaptive immune response, which relies on clonal expansion of lymphocytes expressing receptors that specifically recognize an invading pathogen. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying monospecific receptor expression - allelic exclusion - has proved to be a challenging puzzle, likely because the process involves multiple levels of control. However, allelic exclusion is not infallible as dual Tcr or Ig receptor expressing T and B cells are found at low frequency in the periphery (Fournier et al., 2012; Pelanda, 2014). Although tolerance mechanisms exist to restrain dual receptor cells with a self-reactive receptor (Fournier et al., 2012) these cells can become activated and cause autoimmune disease if the non-self-reactive receptor recognizes a pathogenic antigen (Ercolini and Miller, 2009; Flodstrom-Tullberg, 2003; Ji et al., 2010; Pelanda, 2014). Nonetheless, the effects of these dual receptor cells are not altogether negative as their presence can be beneficial in counteracting infection because allelically included cells expand the receptor repertoire and may in some instances be important for combatting an invading pathogen (He et al., 2002); Thus evolution may tolerate a certain frequency of allelically included dual receptor cells, balancing an autoimmune outcome with that of counteracting infection (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Evolution may tolerate a certain frequency of allelically included dual receptor cells, balancing an autoimmune outcome with that of counteracting infection

All the antigen receptor loci are regulated in a unique manner and in particular they all are subjected to different controls when it comes to allelic inclusion. The Igh locus is subject to stringent allelic exclusion and only 2–4% of mouse spleen B cells contain two in-frame rearrangements with 0.01% expressing dual receptors. Igk and Tcrb are also subject to fairly stringent controls and allelic inclusion occurs at a frequency of 1–7% and 1–3%, respectively. Tcra on the other hand, can rearrange both alleles prior to differentiation, but the frequency of allelic inclusion on the cell surface is only due to 10%, which may be due to post-translation control (Brady et al., 2010).

As mentioned above, allelic exclusion ensures the expression of only one productively rearranged allele (Jung et al., 2006; Vettermann and Schlissel, 2010). The other allele can be non functional for one of three reasons: (i) it remains in germline configuration (Igk or Tcra) or is partially recombined having undergone D-to-J but not V-to-DJ rearrangement (Tcrb or Igh), (ii) the allele has an out of frame rearrangement and the mRNA is degraded by the nonsense mediated decay (NMD) pathway, (iii) the allele encodes a protein that cannot pair with its partner (ie Igh with Igk or Tcrb with Tcra) and thus a receptor cannot be assembled on the surface. In this way allelic exclusion is very different from other well known mono-allelically expressed genes such as olfactory receptors or those resulting from X inactivation, or parental imprinting.

As a general rule, allelic exclusion is enforced during the process of V(D)J rearrangement (Figure 11). However, in some cells with dual rearrangements, the product of only one allele is expressed at the cell surface as a result of post-translational silencing, and in this case allelic exclusion is enforced by a later event (Alam and Gascoigne, 1998).

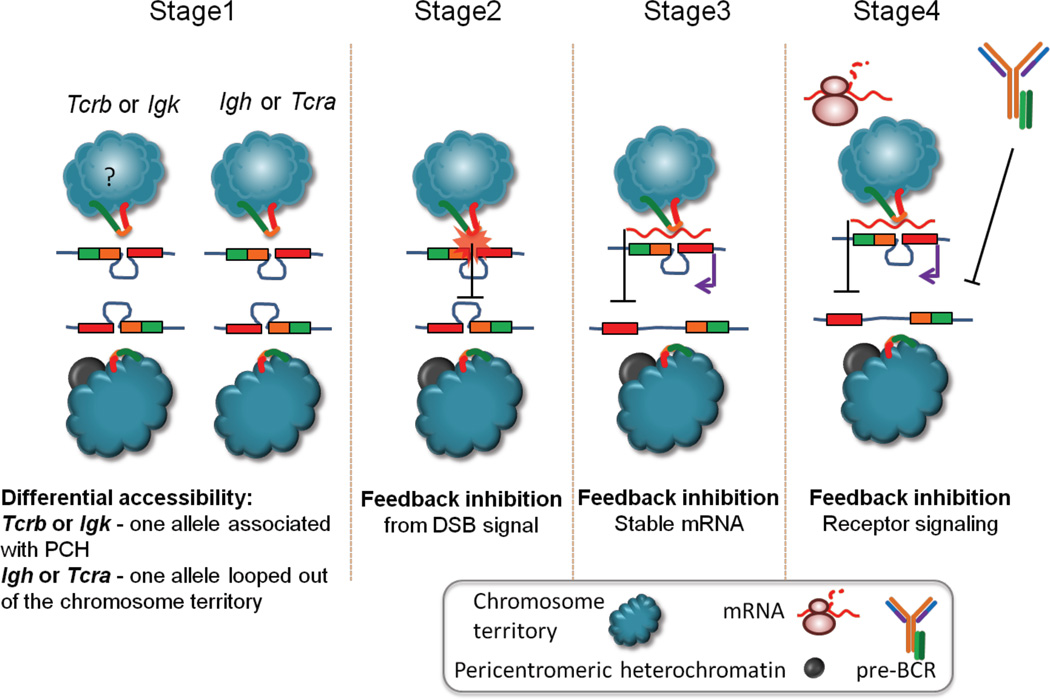

Figure 11.

Allelic exclusion is enforced at multiple stages of development

5.1 Asynchronous rearrangement

Early models proposed that asynchronous recombination occurred as a result of low efficiency recombination (RAG breaks are introduced in around 20% or less cells at any one time) which reduces the chances of rearrangement occurring on the two alleles at the same time. Added to this, the imprecise nature of junctions results in a high failure rate of rearrangements (two out of three will be non-productive) and this in itself will contribute to the initiation of allelic exclusion. Whilst these facts are indisputable it is also now well established that breaks are introduced in a regulated asynchronous manner on all antigen receptor alleles analyzed (Igh, Igk and Tcra) (figure 8) (Chaumeil et al., 2013a; Chaumeil and Skok, 2013; Hewitt et al., 2009). Rearrangement on one allele at a time involves regulation in trans and allelic communication, which may or may not be reliant on pairing (discussed in §3.3). As described in §3.3, the introduction of RAG-mediated cleavage on one allele recruits ATM to the site of the break and this acts in trans on the other allele preventing the introduction of further breaks by a mechanism that involves repositioning of the other allele to repressive pericentromeric heterochromatin and curtailment of higher-order looping (Figure 8).

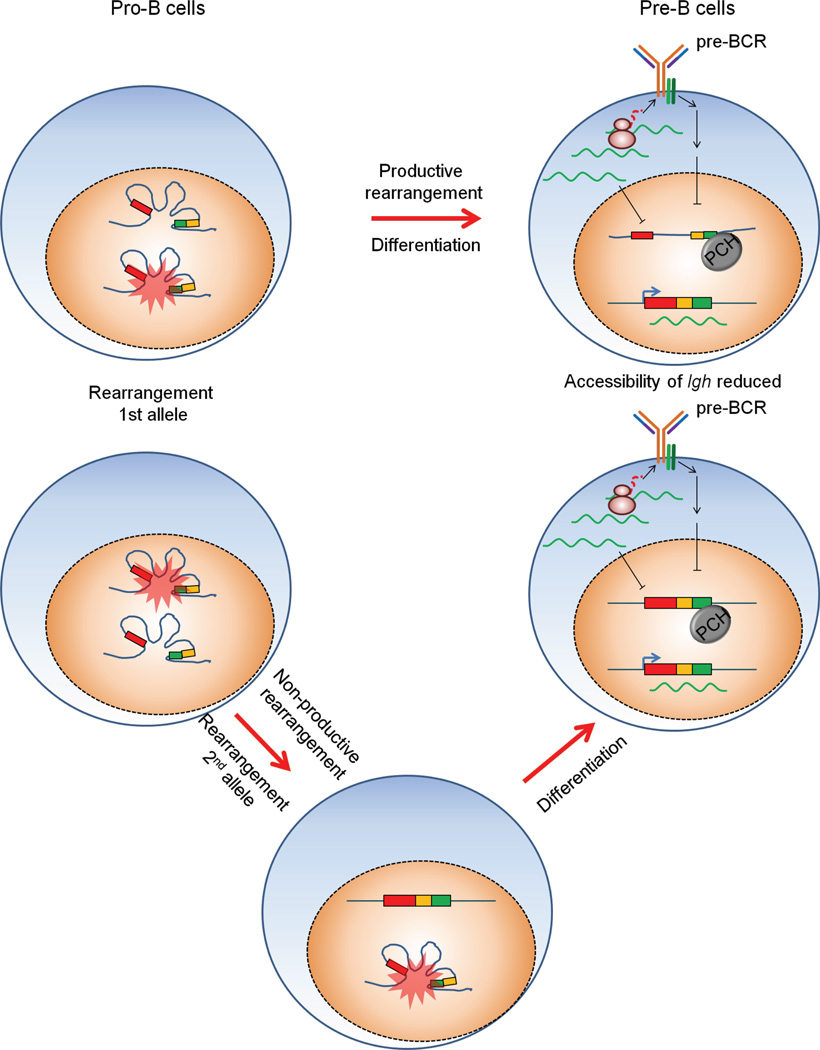

DNA FISH analyses has revealed that in most cells the two Igh and Tcra alleles are both located in euchromatic regions of the nucleus prior to the onset of recombination, and thus by this means of assessment homologues appear to be equivalently accessible to RAG. Despite this observation, our data suggest that mono-allelic targeting of Igh and Tcra occurs preferentially on highly transcribed alleles that are looped outside of their respective chromosome territories and that for both these loci loop formation occurs on only one allele at a time (Chaumeil et al., 2013a; Chaumeil et al., 2013b). We have not yet examined RAG targeting of Igk and Tcrb in the context of higher-order loop formation, however we do know that in contrast, to Igh and Tcra, prior to recombination, one Igk and Tcrb allele are associated with repressive pericentomeric heterochromatin and / or the nuclear lamina in pre-B and DN T cells respectively, while the other allele is found in a euchromatic location where RAG targeting occurs (Roldan et al., 2005; Schlimgen et al., 2008; Skok et al., 2007). Thus differential accessibility of the two alleles may play a role in determining which allele is targeted (Figure 12). However these studies provide no information about whether differential positioning of the two alleles is heritably transmitted or whether the two alleles are equally likely to find themselves in opposite locations in the same, or a subsequent cell cycle.

Figure 12.

Reduced accessibility of Igh downstream of pre-BCR signaling occurs as a result of differentiation and an alteration in signaling pathways that do not support continued accessibility of this locus

5.1.1 Replication timing

Studies from the Bergman lab support a deterministic model of accessibility that relies on the observation that homologous antigen receptor alleles are asynchronously replicated (Mostoslavsky et al., 2001). As a general principal, early replicating loci are more active than late replicating loci. Thus, based on this premise, differences in replication timing likely reflect differences in activation status of homologues and differences in accessibility that may predispose one allele to recombine before the other. According to their data, allelic choice is a random process that mirrors the process of X inactivation. Through lineage tracing experiments they determined that allelic choice (which correlates with differences in replication timing), could be imposed early on in lymphoid development at the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) stage; a subgroup of single CLP cells gives rise to mature B cells that all express Igk from the same allele (Farago et al., 2012). Thus commitment occurs prior to rearrangement, but once allelic differences are imposed they are heritably transmitted through development.

5.1.2 The impact of non-productive rearrangements

A recent study by the Barreto lab presents data that disagree with the Bergman lab’s findings (Alves-Pereira et al., 2014). In this study clonal analysis of reconstituted single IgMa/IgMb heterozygous hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in irradiated RAG deficient recipients consistently generated equal numbers of IgMa and IgMb expressing B cells in each animal. Moreover, PCR analysis showed the expected differences in the retention of a VH-DH intergenic fragment (60% in the VDJH/DJH and 40% in VDJH/VDJH configuration). In contrast CLP-derived clones were completely skewed to either IgMa or IgMb expressing cells and highly skewed clones were found more frequently in Ly6d+ B cell progenitors compared to the more uncommitted Ly6d- cells. Furthermore, Ly6d+ cells and pro-B cells have a similar capability to skew clones. Analyses of Igh rearrangement status on both the productive and silent alleles in skewed clones indicate that the bias to rearrange one allele can be explained by the impact of non-productive rearrangement. Thus, their findings support the idea that the two Igh alleles are synchronously competent to undergo rearrangement. Furthermore, in contrast to the Bergman lab’s findings, they demonstrate that the bias observed for Igh is not reproduced for Igk suggesting that this locus is not pre-committed in the CLP stage of B cell development. Taken together, these data suggest that allelic exclusion of Ig loci differs from X-chromosome inactivation as no stable epigenetic mark is propagated until pro-B cells start rearranging. The key difference in the Barreto and Bergman lab’s studies is that the Bergman lab did not analyze the rearrangement status of the silent allele.

5.2 Feedback Inhibition

5.2.1 Feedback inhibition through the introduction of a DSB break

As discussed in §3.3 above, feedback inhibition occurs at the level of breaks (Figure 8 and 11). A break in one allele or locus inhibits further breaks during repair as a result of ATM and RAG2 mediated control. In the absence of the C terminus of RAG2 and ATM bi-allelic and bi-locus breaks are introduced and this can lead to the generation of intra-locus translocations (Chaumeil et al., 2013a; Chaumeil et al., 2013b; Chaumeil and Skok, 2013; Deriano et al., 2011; Hewitt et al., 2009 6058) which are a hallmark of ATM deficiency. Clearly controlling the number of breaks that are introduced per cell at any one time is important for maintenance of genome stability and thwarting the occurrence of translocations. However feedback control also contributes to the initiation of allelic exclusion by preventing the simultaneous rearrangement of homologues that could lead to allelic inclusion. Support for this comes from the observation that ATM deficient mice have increased allelic inclusion of Igh, Igk and Tcrb (Steinel et al., 2014; Steinel et al., 2013). The C terminus of RAG2 and ATM also inhibit the introduction of bi-allelic breaks on Tcra (Chaumeil et al., 2013a) even though this locus is not subjected to stringent enforcement of allelic exclusion. Thus ATM mediated control of cleavage appears to be a common mechanism that is shared by different loci in recombining lymphocytes as well as in cells undergoing meiosis (see §3.3) (Lange et al., 2011).

5.2.2 Control of recombination via regulation of RAG expression – implications for allelic exclusion

It is clearly critical to have mechanisms in place to control RAG activity to ensure that cleavage does not occur across cell cycle as this could lead to genome instability. Productive rearrangement of an Igh or Tcrb allele in pro-B or DN cells, respectively leads to cell surface expression of the pre-BCR or pre-TCR. Signaling through these two receptors results in a proliferative burst and subsequent differentiation to the pre-B or DP cell stage where Igk, Igl or Tcra are recombined. There are two known mechanisms that have evolved to prevent the introduction of breaks during cell cycle. The first involves degradation of RAG2 protein (Lee and Desiderio, 1999) and the second involves control of Rag1 expression (Johnson et al., 2012). Both mechanisms are also important for preventing the introduction of further breaks on the second allele, which could violate allelic exclusion.

5.2.3 Feedback Inhibition by productive mRNA

Two thirds of transcripts generated by rearrangement are out-of-frame. In contrast to mRNAs from productively rearranged alleles, these are degraded by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway, which selectively degrades transcripts harboring premature termination codons (Figure 11) (Weischenfeldt et al., 2008). Recent studies suggest that mRNA from productively rearranged alleles can have a role in suppressing rearrangement and initiating allelic exclusion. The evidence for this comes from two complementary mouse models. The first harbors a dominant-negative mutation of Rent1/hUpf1, an essential trans-effector of the NMD pathway. This mutation induces premature shut-off of Tcrb rearrangement causing a block in T cell development at the DN stage. This defect can be rescued with a productively rearranged Tcrb transgene, suggesting that mRNA has a function in V(D)J recombination independent of its protein product (Frischmeyer-Guerrerio et al., 2011).

Further support for a negative regulatory role for mRNA in recombination comes from a mouse model that has the endogenous DQ52JH cluster replaced by a VHB1–8 VDJ exon rendered nonproductive by the introduction of a termination codon at position 5 on one allele (Ter5 allele) (Lutz et al., 2011). Transcription of the targeted Igh allele is driven by its physiological Igh chain promoter in one mouse line (Ter5hi), while in the other transcription is driven by a weak, truncated DQ52 promoter (Ter5lo). This results in the production of Ter5 high and low amounts of stable Igh transcripts, respectively that do not encode protein. Thus, stable Igμ mRNA is separated from translation into IGH protein. The presence of stable Ter5hi transcripts leads to a severe block in B cell differentiation at the pro-B cell stage and a corresponding decrease in the pre-B cell compartment. Importantly, the block in development is linked to a decreased frequency of recombined Igh alleles, while the RAG recombinase remains unaffected (Lutz et al., 2011) (Figure 11). Recombination of the wild type allele is inhibited in the Ter5hi heterozygous cells, preventing the generation of a productively rearranged Igh allele that could drive development to the pre-B cell stage. In contrast, there is a significantly higher frequency of Igh rearrangement on the non-targeted allele in the heterozygous Ter5lo mice. Thus it appears that the difference in mRNA stability allows pro-B cells to distinguish between productive and non productive Ig gene rearrangements and that the presence of stable Igμ transcripts contributes to Igh chain allelic exclusion.

5.2.4 Feedback Inhibition at the level of protein