Abstract

Local therapy for in-transit melanoma (ITM) is a treatment alternative for patients who are not good candidates for systemic therapy, regional therapy, or surgical management. In this case report, we describe 3 patients with ITM who were treated with intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (ILBCG) and/or topical imiquimod. Treatment course was dictated by the clinical response. Patient 1’s response to ILBCG monotherapy was not sufficient to cause disease regression; however, transition to topical imiquimod therapy resulted in complete and sustained response. Although patient 2 responded to ILBCG and imiquimod, she developed a hypersensitivity reaction to ILBCG; when topical imiquimod was continued as monotherapy, her clinical response was complete. Patient 3 responded completely to ILBCG monotherapy in injected lesions, but expired shortly thereafter from unrelated disease. Reports like this one are needed to define the success measures of local therapy in the treatment of ITM.

Key Words: in-transit melanoma, local therapy, intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, ILBCG, topical imiquimod

Often an ominous sign, in-transit melanoma (ITM) occurs when a primary melanoma extends locally and regionally. Depending on regional node involvement, staging of patients is assigned either stage IIIB or IIIC, for which there are several treatment options. When a single or small number of lesions is present, surgical excision is appropriate, but alone, is associated with high rates of local and regional disease recurrence.1 Another option, regional chemotherapy, such as isolated limb perfusion/infusion, carries the risk of regional toxicity.2 Other more conservative options for the treatment of ITM involve topical and intralesional therapy. Topical agents like diphencyprone have had partial or complete success in treating recurrent disease.3 Topical imiquimod, a Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist and immunomodulator, has been used either alone or in combination with other agents with success in treating superficial lesions.4 Intralesional therapy, such as Rose Bengal (PV-10), involves injection of an agent directly into a lesion and incites an antitumor immune response.5

Recently, a case series described success, with off-label use of intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (ILBCG) and topical imiquimod therapy in the treatment of stage III melanoma.1 In this series, 9 patients with ITM metastases but no distant metastases were started on a combination of ILBCG and topical imiquimod 5% cream. Topical imiquimod was used to induce greater inflammation to achieve sufficient immune responses in the setting of widely distributed lesions. The outcomes were favorable, with 5 patients attaining complete regression. Three others underwent resection of solitary resistant lesions and, ultimately, reached complete resolution. Overall, 78% of patients achieved complete and durable locoregional control. ILBCG and topical imiquimod therapy hold great promise for management of ITM, particularly when surgical management is not feasible, and other systemic modalities may confer significant toxicities. In this report, we describe the treatment course of 3 patients with at least stage IIIB and IIIC ITM. All 3 patients received ILBCG (Tice strain) as described by Kidner et al,1 and 2 received imiquimod either concurrently or sequentially.

CASE PRESENTATION

Patient 1: Sequential Therapy to Lower Leg ITM

An 86-year-old white female with dementia presented with a 2×2 cm dark brown plaque on her anterior left lower leg. The lesion had enlarged and become hypopigmented at the center in the last year, and several 3–4 mm nonpigmented pink nodules had appeared at lateral and inferior sites to the primary lesion (Fig. 1A). Biopsy of the primary lesion revealed a 1.4-mm-thick melanoma (Clark’s level IV), a mitotic rate of 2 per squared-mm, and no evidence of ulceration or regression. Further biopsy of a satellite lesion confirmed ITM. A positron emission tomography/computerized axial tomography scan was negative, consistent with T2aN2cM0, or stage IIIB disease. Because of the patient’s advanced age, advanced cardiopulmonary disease, and the extent of her melanoma lesions, the patient’s family (consenting for the patient) opted for ILBCG. She received a sensitization dose of 3 million colony-forming units (CFU) of BCG distributed among 8 lymph node basins, and 1.5 million CFU 2 weeks later. Intralesional injection doses after sensitization (350,000 CFU) were titrated to produce a moderate local inflammatory reaction. She tolerated the sensitization and first intralesional injections well, with only mild erythema, induration, then ulceration and crusting at the sensitization sites. Although the primary lesion faded from black to dull-gray, a month later, a new nodule on the medial left lower leg was noted outside the field of the previous ITM lesions: this was injected, along with 7 adjacent sites. She developed mild fever and chills (grade 1) following the BCG injection, which was controlled with acetaminophen.

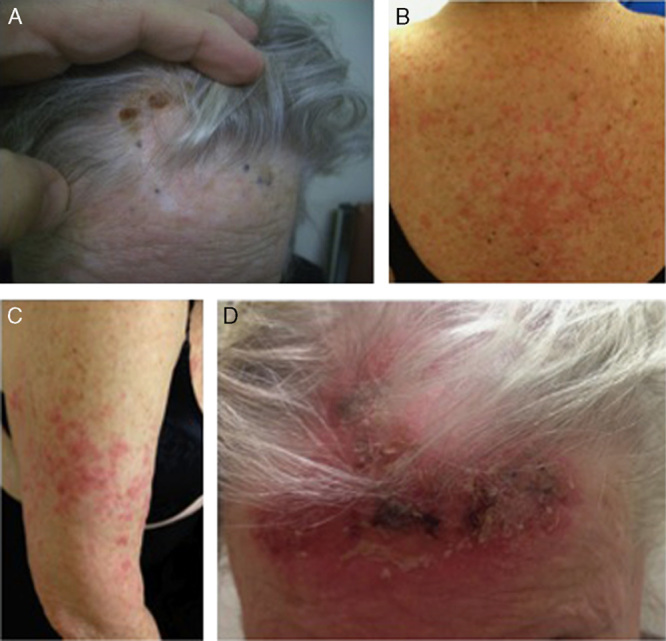

FIGURE 1.

Patient 1’s response. A, Primary lesion is a 2×2 cm dark brown plaque on the anterior left lower leg that had enlarged and become hypopigmented. Several 3–4 mm nonpigmented pink nodules appeared at lateral and inferior sites to the primary lesion. B, After several months of imiquimod topical therapy, all lesions developed variable degrees of inflammation and crusting. C, Almost 3 years after discontinuation of all therapy, the patient remained disease free.

Five weeks later, the primary lesion lost all pigment, however, 2 nonpigmented papules persisted, and a new erythematous papule at the inferior aspect of the in-transit field was biopsied and showed persistent melanoma. Upon reconsidering the options, the patient’s family opted for topical therapy. After 1 month of applying imiquimod 5% cream every other night, a new nodular plaque and a pink papule appeared, thus application was increased to nightly. The nodules then developed variable degrees of inflammation and crusting (Fig. 1B), followed by flattening and fading. With good response after 7 months of nightly therapy, the patient switched to 1 application every 2–3 days. In total, the patient received 3 BCG injections (1 initial sensitization and 2 ILBCG) and imiquimod for 34 weeks of active management and 28 weeks of maintenance therapy. Therapy was discontinued 6 months later, and 3 years and 11 months later, she remained disease free (Fig. 1C), eventually expiring from a small bowel obstruction unrelated to her melanoma.

Patient 2: Split Therapy to Scalp ITM

An 88-year-old white female presented with a 1-year history of crusting on the frontal scalp that developed dark pigmentation, prompting her to seek medical attention. On examination, the patient had nine 1–3 mm gray to purple-black macules and thin papules (Fig. 2A). Biopsy revealed a 1.5-mm-thick melanoma (Clark’s level IV), a mitotic rate of 4 per squared-mm, with evidence of ulceration. An additional biopsy showed changes consistent with ITM. Although no lymphadenopathy was revealed, her staging positron emission tomography/computerized axial tomography scan showed a pancreatic mass with subsequent biopsy revealing pancreatic adenocarcinoma, thus her melanoma was consistent with T2N2cM0, or stage IIIC. Because of her comorbid pancreatic disease, the patient opted for conservative treatment of her melanoma with ILBCG and topical imiquimod. She received a BCG sensitization dose of 3 million CFU, and 1.5 million CFU 2 weeks later. To compare treatment efficacy, she was subsequently started on split therapy: the right-sided lesions were injected with BCG, and the left-sided lesions treated with imiquimod 5% cream daily. Five days later, the patient developed numerous edematous, pink-red papules and plaques on the back and proximal bilateral arms (Figs. 2B, C), along with eyelid edema, without any systemic symptoms, and skin biopsy suggested a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction. The reaction resolved after 2 weeks of holding all therapy and applying clobetasol 0.05% cream twice daily.

FIGURE 2.

Patient 2’s response. A, Primary lesions are nine 1–3 mm gray to purple-black macules and thin papules on the frontal scalp. The crusted brown lesions were the sites of biopsy. B and C, Following 1 sensitization dose of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, the patient developed numerous edematous, pink-red papules and plaques on the back and proximal bilateral arms, consistent with lichenoid drug eruption. D, Following topical imiquimod application, most lesions faded and developed inflammatory changes and hemorrhagic crusting, and 6 weeks after discontinuation of therapy, signs of complete regression were observed (images not shown).

Because of persistent in-transit lesions, the patient restarted topical imiquimod, with daily applications on the right forehead, and every other day on the left forehead, where lesions had regressed to a large inflamed hemorrhagic crust. Therapy was then held for 6 weeks for her pancreatic surgery, and at follow-up, examination revealed 4 pink nodules with overlying crust and shallow ulcers on the right forehead, and 4 pigmented purple-black papules on the left forehead. Imiquimod applications were restarted every other day for 3 weeks, then increased to 5 times per week for another 3 weeks. By the end, most lesions were faded and had developed inflammation and hemorrhagic crusting (Fig. 2D), and therapy was then discontinued. In total, this patient received 2 BCG vaccinations (one sensitization and another intralesional) and 10 weeks of imiquimod on the left forehead and 7 weeks of imiquimod on the right forehead. At a follow-up visit 6 weeks after discontinuation of therapy, examination revealed skin-colored flat scars in the area of the primary melanoma along with faded light gray macules in place of the previous purple, pigmented papules, suggestive of regression. The patient expired 4 days later from an unrelated myocardial infarction.

Patient 3: ILBCG to Lower Leg ITM

A 90-year-old white male presented with a nonpigmented papule on the posterior right lower leg that was present for several years and recently increased in size. In the last year, he also developed a cluster of new pink papules adjacent to the original lesion in the posterior medial leg (Fig. 3A), but also a separate cluster in the inferolateral aspect of the leg (not shown). A few scattered nodules were also present on the posterior aspect. Biopsy of the original papule revealed an 8.25-mm-thick melanoma (Clark’s level IV), a mitotic rate of 8–9 per squared-mm, without ulceration or vascular invasion, but with evidence of regression. The patient declined a staging CT scan, so staging was determined to be at least T4aN2cMx, or stage IIIB. The patient was relatively healthy, with history of thyroid goiter and prostatic enlargement. After reviewing treatment options, he opted for conservative management with ILBCG, and received a sensitization dose, that resulted in erythema and induration at the site.

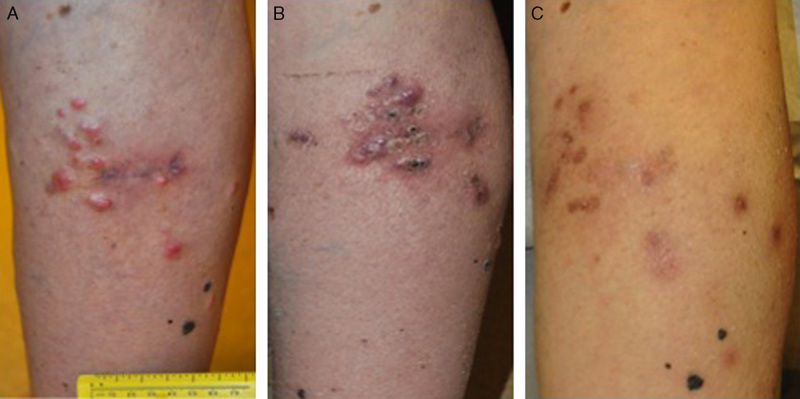

FIGURE 3.

Patient 3’s response. A, The primary lesion is a nonpigmented papule on the posterior right lower leg, surrounded by a cluster of pink papules in the posterior medial leg. B, Following 2 intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (ILBCG) injections in the posterior leg, injected lesions faded in color from black to gray and decreased in size and elevation, whereas uninjected lesions in the pretibial, medial lower, and posterior lower calf faded in color from black to gray and decreased in size and elevation. C, Six months from the first sensitization, there was a complete clinical response at the injected sites. A subcutaneous nodule was found beneath the prior biopsy site on the right posterior calf that had not been treated with ILBCG (not shown).

Over the next 3 weeks, the patient received 2 ILBCG injections in the posteromedial lesions of the right lower leg. Three weeks later, the injected lesions were erythematous and edematous. Because the lateral lesions were unchanged, they received an injection. Two weeks later, both posterior and lateral leg lesions demonstrated inflammation, without ulceration, some appearing flatter. Over the next 2 months, injected lesions began to soften and flatten, whereas uninjected lesions in the pretibial (not shown), medial lower, and posterior lower calf faded in color from black to gray and decreased in size and elevation (Fig. 3B). Two weeks later, or 6 months from the first sensitization, there was a complete clinical response at the injected sites (Fig. 3C), but a subcutaneous nodule was found beneath the prior biopsy site on the right posterior calf that had not been treated with ILBCG. Because of the solitary nature and subcutaneous site, an excisional biopsy was performed, which revealed melanoma within the dermis typical of satellite metastasis. The patient refused another staging CT scan or further treatment and expired from unrelated congestive heart failure.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report 3 patients with at least stage IIIB and IIIC melanoma who underwent a combination of ILBCG and imiquimod therapy. The response in patient 1 to ILBCG alone was not sufficient to cause disease regression, but transition to topical imiquimod therapy resulted in complete and sustained response. Patient 2 had begun to respond to treatment, but developed a hypersensitivity reaction, possibly due to the number of antigens introduced by BCG vaccine to her immune system. Subsequent continual treatment with topical imiquimod resulted in regression of the primary melanoma site, along with flattening and fading of the ITM nodules. Patient 3 responded completely to 3 BCG injections, until his disease progressed and he expired from unrelated causes.

Mechanistically, imiquimod is an innate immune agonist for TLR7. By activating TLR7, imiquimod induces proinflammatory cytokines that facilitate CD8+ antitumor responses and promote CD4+ helper T-cell responses.6 Approved for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratoses, and genital warts, imiquimod also has demonstrated efficacy in ITM metastases, as both single agent and in combination with topical gentian violet7 and intralesional interleukin-2,8 among others. These studies are promising, but more data are needed to determine success rates, long-term efficacy, and prediction of lesion response. One advantage of using topical imiquimod is the ability to treat a broad area of involvement with multiple diffuse lesions, in which ILT would be difficult or impractical.

In contrast to imiquimod, BCG is an attenuated, live vaccine of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that expresses various ligands, which predominantly bind to 2 TLRs, TLR2 and TLR4.9 In the 1970s, BCG was directly injected into the nodules of melanoma patients with intradermal or visceral metastases either in combination with surgical excision or as monotherapy.10 Results were promising with complete regression of 90% of injected lesions, but only 17% of uninjected nodules. Unfortunately, patients experienced high rates of fever, chills, localized abscesses, and regional lymphadenitis as great amounts were often injected, and it fell out of favor with dermatologists. In contrast, more recent reports, such as the case series by Kidner et al,1 suggest that proper dosing of ILBCG combined with topical imiquimod can lead to successful treatment of ITM metastases. In our study, 2 patients responded to a combination of BCG Tice strain and topical imiquimod 5% cream, although patient 2 experienced a hypersensitivity reaction to ILBCG, and 1 patient responded to ILBCG.

In this present study, we report 3 cases of patients with ITM who responded to topical imiquimod and/or ILBCG. Our study adds to the growing literature on the use of combination local therapy. Emerging reports as this one are needed to define the success rates of topical and intralesional immunotherapy in the treatment of ITM and the management of side effects such as hypersensitivity reactions. The advantages of local therapy include overall low morbidity, even in frail, elderly patients, and low cost. It should remain a treatment option for ITM in scenarios where regional therapy and surgical management may be suboptimal or not possible.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

All authors have declared there are no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kidner TB, Morton DL, Lee DJ, et al. Combined intralesional Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and topical imiquimod for in-transit melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35:716–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testori A, Verhoef C, Kroon HM, et al. Treatment of melanoma metastases in a limb by isolated limb perfusion and isolated limb infusion. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damian DL, Thompson JF. Treatment of extensive cutaneous metastatic melanoma with topical diphencyprone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:869–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman B, Poochareon VN, Villa AM. Novel dermatologic uses of the immune response modifier imiquimod 5% cream. Skin Ther Lett. 2002;7:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grotz TE, Mansfield AS, Kottschade LA, et al. In-transit melanoma: an individualized approach. Oncology. 2011;25:1340–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narayan R, Nguyen H, Bentow JJ, et al. Immunomodulation by imiquimod in patients with high-risk primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;321:163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbiser JL, Bips M, Seidler A, et al. Combination therapy of imiquimod and gentian violet for cutaneous melanoma metastases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:e81–e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia MS, Ono Y, Martinez SR, et al. Complete regression of subcutaneous and cutaneous metastatic melanoma with high-dose intralesional interleukin 2 in combination with topical imiquimod and retinoid cream. Melanoma Res. 2011;21:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O, et al. Maturation of human dendritic cells by cell wall skeleton of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin: involvement of toll-like receptors. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6883–6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morton D, Eilber F, Holmes E, et al. BCG immunotherapy of malignant melanoma: summary of a seven-year experience. Ann Surg. 1974;180:635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]