Abstract

Introduction

A preponderance of relevant research has indicated reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms following smoking abstinence. This secondary analysis investigated whether the phenomenon extends to smokers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods

The study setting was an 11-Week double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial of osmotic release oral system methylphenidate (OROS-MPH) as a cessation aid when added to nicotine patch and counseling. Participants were 255 adult smokers with ADHD. The study outcomes are: anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)) and depressed mood (Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI)) measured one Week and six Weeks after a target quit day (TQD). The main predictor is point - prevalence abstinence measured at Weeks 1 and 6 after TQD. Covariates are treatment (OROS-MPH vs placebo), past major depression, past anxiety disorder, number of cigarettes smoked daily, demographics (age, gender, education, marital status) and baseline scores on the BAI, BDI, and the DSM-IV ADHD Rating Scale.

Results

Abstinence was significantly associated with lower anxiety ratings throughout the post-quit period (p<0.001). Depressed mood was lower for abstainers than non-abstainers at Week 1 (p<0.05), but no longer at Week 6 (p=0.83). Treatment with OROS-MPH relative to placebo showed significant reductions at Week 6 after TQD for both anxiety (p<0.05) and depressed mood (p<0.001), but not at Week 1. Differential abstinence effects of gender were observed. Anxiety and depression ratings at baseline predicted increased ratings of corresponding measures during the post-quit period.

Conclusion

Stopping smoking yielded reductions in anxiety and depressed mood in smokers with ADHD treated with nicotine patch and counseling. Treatment with OROS-MPH yielded mood reductions in delayed manner.

Keywords: Smoking Abstinence, ADHD, Anxiety, Depressive Mood

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains a leading risk factor for increased morbidity and premature mortality. Smoking cessation can substantially reduce those risks; however, achieving tobacco abstinence can be difficult. Although many smokers report a desire to stop smoking, not all make a serious quit attempt. Among multiple barriers to a quit attempt is the fear that stopping smoking would remove various benefits attributed to cigarette smoking and, instead, exacerbate or provoke negative affective states previously suppressed by tobacco. Empirical evidence, however, has provided mixed support. Multiple indications that anxiety increases during the first 1-3 days and up to two Weeks post-cessation (Hughes, 2007) contrast with the observation of decreased anxiety in weekly ratings throughout the 4-Week post-cessation period in a sample of completely abstinent smokers (West & Hajek, 1997). With regard to depression, the Hughes 2007 review identified numerous studies that indicated increased dysphoria with abstinence as well as differences in the time course (peaking variously at 3 days to Weeks) but also cited several cessation trials that found no change or decreases in post-cessation dysphoria. Later trials conducted in smokers with past or current depression, also offered mixed evidence of increased (Evins et al, 2008) as well as unchanged or decreased levels of anxiety and depression (Berlin et al, 2010; Blalock et al, 2008) during the first early Weeks and up to 12 Weeks following stopping smoking. Demonstrating inconsistency of evidence from large scale studies, a study that followed 491 smokers from a smoking clinic through six months of follow-up, observed that anxiety decreased in abstainers but increased in relapsers (McDermott et al, 2013); by contrast, in an international longitudinal study of 3545 smokers, no change in anxiety scores was seen (Shahab et al, 2014).

A recent meta-analysis of 26 longitudinal studies (Taylor et al, 2014) that overwhelmingly indicated favorable rather than adverse consequences of abstinence may help put the controversy to rest. Abstinence compared to continued smoking was associated with greater decline in depression, anxiety, stress, and with improvements in quality of life and positive affect. Analyses by length of follow-up (acute treatment period versus months of follow-up), type of study sample (clinical or community-based population), the presence or not of past mental illness, psychological intervention, and methods to ascertain abstinence status, did not alter the main finding.

None of the studies included in the Taylor meta-analysis employed smokers identified as persons with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), prompting the present investigation. ADHD is a neuropsychiatric condition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5% (Polanczyk et al, 2007). Persons with ADHD are more frequently smokers (Pomerleau et al., 2003; Sullivan & Levin, 2001; Tercyak et al, 2002), and experience greater difficulty quitting smoking than smokers without ADHD (Covey et al, 2008; Humfleet et al., 2005; Pomerleau et al., 1995). The co-presence of mental illness, known to compromise smokers’ ability to quit smoking (Cook et al, 2014), is higher in persons with ADHD (Cumyn et al, 2009).

The ability of nicotine to ameliorate inattentiveness (Conners et al., 1996; Levin, et al., 1996) and deficits in dopaminergic function related to inattentiveness (Volkow et al., 2007) and impulse control (Diergaarde et al, 2008) suggests a “self-medication” rationale. Accordingly, for smokers with ADHD, nicotine abstinence could be expected to aggravate inattentiveness and restlessness, the core symptoms of ADHD, thereby preventing successful smoking cessation. However, earlier reports from a smoking cessation trial of an ADHD medication (osmotic release oral system methylphenidate (OROS-MPH)) for smokers with ADHD found no association overall between abstinence and change in ADHD symptoms throughout the trial (Covey et al, 2010; Winhusen et al, 2010). Whether abstinence exerted an effect on anxiety and depression was not examined. Negative affect following abstinence, an undesirable clinical outcome by itself, can result in a return to smoking within weeks after quitting (Covey et al, 1990; West et al, 1989). Conversely, evidence of improved mood states following abstinence could increase motivation, confidence, and success in efforts to stop smoking.

The present study is a secondary analysis of data from the aforementioned Smoking/ADHD trial (Winhusen et al, 2010) to investigate post-abstinence trends in anxiety and depression among smokers with ADHD. Intent-to-treat analysis of the study data did not find a significant effect of OROS-MPH versus placebo treatment on cessation outcome (Winhusen et al, 2010). Nevertheless, the study revealed a sizable proportion (43% of 255) that achieved prolonged abstinence spurring the present effort to determine the direction of symptom change following the target quit day (TQD).

We hypothesized that decreased anxiety and depression after quit day would be more characteristic of abstainers than non-abstainers. Further, since OROS-MPH, the medication tested for smoking cessation in the parent trial, is well-demonstrated to decrease ADHD symptoms (Wilens et al, 2011), we also predicted that participants randomized to OROS-MPH would have significantly lower anxiety and depression than placebo-treated participants. In corollary analysis, we examined whether a change in ADHD symptoms during the trial influenced post-cessation anxiety and depression. Finally, we explored main effects of subjects’ characteristics measured at baseline, i.e., age, gender, ADHD symptoms, baseline anxiety and depression symptom levels, and a history of anxiety or depressive disorder.

2. METHODS

Two hundred and fifty-five adult smokers who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD comprised the study sample. The protocol, procedures and methods for the multi-site, randomized, placebo controlled trial have been described in detail elsewhere (Winhusen et al, 2010). Eligible participants were smokers of 10 or more cigarettes daily, aged 18 to 55 years, met diagnostic criteria for ADHD (total ADHD scores > 22) (Du Paul et al, 1998), were not treated with psychostimulants within the last 30 days, wished to quit, and were in good physical health. Exclusion criteria included use of tobacco products other than cigarettes in the past Week, positive urine screen for an illicit drug, meeting DSM-IV criteria for current major depression, anxiety disorder, substance dependence, a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychosis, significant suicidal/homicidal risk, and medical conditions contraindicating use of OROS-MPH. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to use an adequate method of birth control were excluded.

Participants were recruited at six study sites (Cambridge, Massachusetts; Columbus, Ohio; New York City, New York (2 sites); Portland, Oregon; and Rochester, Minnesota). Individuals interested in participation received a thorough explanation of the study and provided signed informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study. The trial was sponsored by the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network and conducted between December 2005 and January 2008.

The study included a four-week pre-quit phase and a seven-week planned abstinence period. Participants were randomized to OROS-MPH or matching placebo in a 1:1 ratio with stratification by site. For those randomized to OROS-MPH, the starting dose of 18 mg/day was increased during the first two study Weeks to a maximum of 72 mg/day. All participants received study medication (OROS-MPH or placebo) during Weeks 1-11 and were instructed to use 21 mg/24h nicotine patches daily starting on the target quit date (i.e., study day 27) through the end of Week 11. The nicotine patch dose was tapered during Weeks 12 to 14. A smoking cessation counselor provided individual 10-minute counseling at each clinic visit during Weeks 1 through 11. Smoking cessation counseling was standardized using manual-based counseling that followed principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (Croghan et al, 2012) monitored by Mayo Clinic supervisors. Study participants received $25 per research visit and $50 at the end-of-treatment visit.

Measures

Participants’ self-reported levels of anxiety and depressed mood during the past week were measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck & Steer, 1993) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI II) (Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996), respectively. Both the BAI and the BDI II are 21-item 4-point (0-3) Likert-type questionnaires. Reported internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha is 0.94 for the BAI (Beck & Steer, 1993); and 0.93 for the BDI II (Beck et al., 1996). These inventories were administered at baseline and at Weeks 1 and 6 after TQD.

The outcomes of interest were anxiety (BAI) and depressed mood (BDI-II) measured at Weeks 1 and 6. The main predictor was point-prevalence weekly abstinence at Week 1 and Week 6 after TQD. Abstinence from cigarettes was assessed at each visit using the time-line follow-back method (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), verified by exhaled carbon monoxide <8 parts per million (Jarvis et al, 1987). Covariates were: treatment (with OROS-MPH or placebo), baseline scores on the BAI, the BDI, the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS), past anxiety disorder, past major depressive disorder (MDD), demographic variables (age, gender, education, marital status), number of cigarettes smoked per day, and compliance with nicotine patch and OROS-MPH/placebo treatment. Medication and nicotine patch compliance at Weeks 1 and 6 after TQD were calculated by dividing the self-reported number of pills/patches taken by the number prescribed in the past Week.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics were not different by treatment group (Winhusen et al., 2010) or end-of-treatment abstinence status (Covey et al, 2010). The study attendance and assessment completion were not different by treatment group, baseline anxiety or depressive mood. The generalized linear model (GLM) was applied to anxiety and depressive mood at Week 1 and Week 6 after TQD. Each outcome was modeled as a function of point-prevalent abstinence at assessment time-points (Week 1 and Week 6 after TQD), treatment (OROS-MPH vs. placebo), and the posited co-variates. Interactions among the predictors were tested. The effects of compliance to nicotine patch and OROS-MPH/ placebo treatment were controlled and clinical sites were entered as a fixed effect in the models. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random (Little & Rubin, 2002). The GLM methodology handled within-subject correlation arising from repeated measures using the procedure PROC GENMOD in SAS (SAS 9.3).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

The mean age of the sample (N=255) was 37.8 years (SD=9.9); 57% were male, 79% white, and 44% never married. The average education level was 14.4 (SD=2.4) years. The mean baseline BAI score was 6.15 (SD = 6.45, range=0-30; range by symptom level was: 68.5% minimal 0-7, 21.7% mild 8-15, 8.6% moderate 16-25, and 1.2% severe >=26). The mean baseline BDI score was 9.1 (SD = 8.1, range=0-39; range by symptom level was: 61.4% minimal 0-9, 24.8% mild 10-18, 12.6% moderate 19-29, and 1.2% severe >=30). None met criteria for a current DSM-IV diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive disorder. Thirty four percent reported past anxiety disorder; the same proportion reported past major depression.

3.2 Anxiety and Depressive Mood Scores

Anxiety scores (BAI) decreased across the sample, from 6.15 (SD=6.45) at baseline to 5.05 (SD=5.28) at Week 1 after TQD (baseline vs. Week 1, t = 2.98, p<.01), to 3.84 (SD=4.56) at Week 6 after TQD (Week 1 vs. Week 6 t = 4.18, p<.0001). Depression scores (BDI) also decreased across the total sample, from 9.1 (SD=8.1) at baseline, to 6.73 (SD=5.53) at Week 1 after TQD (baseline vs. Week 1, t= 4.39, p<.0001), and 5.20 (SD=5.40) at Week 6 after TQD (Week 1 vs. Week 6, t = 5.09, p<.0001).

3.3 Abstinence Effects on Anxiety and Depression

Baseline anxiety scores did not differ by abstinence status at Week 1 TQD (t=0.17, p=0.87), or at Week 6 (t=1.55, p=0.12) after TQD. Similarly, baseline depression scores did not differ by abstinence status at Week 1 (t=0.37, p=0.71), or Week 6 (t=0.74, p=0.46). The lack of difference in baseline anxiety and depression scores by abstinence status after TQD negates the possibility that differing trends in mood ratings after TQD, described below, were extensions of pre-quit day conditions.

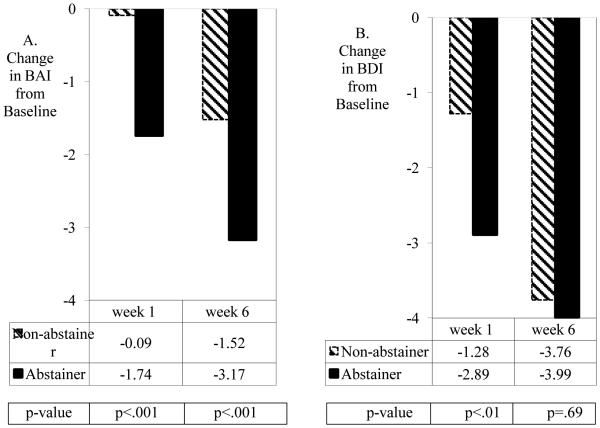

Abstainer versus non-abstainer status was associated with a greater decline in anxiety scores from baseline to Weeks 1 and 6 after TQD (Figure 1A). The GLM model for anxiety measured at Weeks 1 and 6 (Table 1) indicated statistical significance for the main effect of abstinence (p<0.001). For depression scores, Figure 1B shows a decline from baseline to Week 1, although no longer at Week 6 after TQD. The GLM model for depression measured at Weeks 1 and 6 indicated a significant interaction of abstinence status with time (β=1.39, s.e.=0.67, p<0.05). As shown in Table 1, the effect of abstinence on depression at Week 1 was significant (p<0.05), but not at Week 6 (p=0.83). Figure 1B shows that at Week 6 depressed mood among non-abstainers had approached the reduced levels of depression seen among abstainers.

Figure 1.

Estimated change in Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) scores by point-prevalence abstinence (A), and estimated change in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores by point-prevalence abstinence (B) for participants with ADHD in a randomized double-blind smoking cessation trial of OROS-MPH vs. placebo added to nicotine patch and counseling.

Table 1.

Generalized linear regressions on anxiety and depressive mood after target quit day (TQD) for smokers with ADHD in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled smoking cessation trial of OROS-MPH vs. placebo (N=255)

| Anxiety | Depressive Mood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | s.e. | Beta | s.e. | |

| Main Predictors | ||||

| Point-prevalence Abstinence | −1.63*** | 0.45 | ||

| Abstinence by Week : At Week 1 At Week 6 |

−1.51* | 0.61 | ||

| −0.21 | 0.55 | |||

| Covariates | ||||

| Treatment (OROS-MPH vs. Placebo) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Treatment by Week: At Week 1 At Week 6 |

0.06 | 0.64 | −0.98 | 0.68 |

| −1.47* | 0.60 | −2.41*** | 0.67 | |

| History of Anxiety Disorder | −0.15 | 0.64 | −0.26 | 0.69 |

| Baseline Beck Anxiety Inventory | 0.29*** | 0.06 | -- | -- |

| History of Major Depression | 0.94 | 0.68 | 2.02** | 0.75 |

| Baseline Beck Depression Inventory | -- | -- | 0.20*** | 0.05 |

| ADHD Scores at Baseline | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day at baseline | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Gender (female) | 1.31* | 0.54 | 0.88 | 0.67 |

Age, gender, marital status, education, and treatment compliance were controlled for in the models; none were significant except for gender on anxiety. No three-way interactions were significant.

p<05,

p<.01,

p<.001

3.4 Treatment, gender, and other covariate effects

OROS-MPH or placebo treatment had begun upon randomization at the initial clinic visit. At Week 1 after TQD, anxiety and depression ratings showed no difference by drug treatment; at Week 6 after TQD (Table 1), anxiety and depression scores were significantly lower with OROS-MPH than placebo (for anxiety, p<0.05; for depression, p<0.001). The interaction effects of treatment and time on post-quit anxiety (β=−1.52, s.e.=0.58, p<0.05) and depression (β=−1.44, s.e.=0.59, p<0.05) indicating greater effects over time were significant. The two-way interaction effect on anxiety and depression of treatment and abstinence and the three-way interaction effect among treatment, time and abstinence were not significant.

The GLM model showed a significant main effect of gender on anxiety but not on depression. (Table 1). Further analysis showed a significant effect on anxiety of the interaction of abstinence with gender (χ2(1)=7.44, p<0.01). In men, anxiety scores after quit day declined from baseline regardless of abstinence status; in women, anxiety scores declined from baseline among abstainers, but were unchanged, relative to baseline level, among non-abstainers. There was no treatment by gender effect on anxiety (χ2(1)=0.37,p=0.54). For depression, a similar significant interaction of abstinence with gender was observed (χ2(1)=4.73, p<0.05). Considering the significant two-way interaction effect on depression between abstinence and time (indicating stronger abstinence effect at Week 1) (Table 1), depression scores at Week 1 declined from baseline for men regardless of abstinence status and for abstinent women, but remained at baseline levels for non-abstinent women. There was no significant interaction of treatment with gender (χ2(1)=0.02, p=0.90).

Baseline anxiety predicted an increase in post-cessation anxiety; baseline depression and a history of major depression predicted an increase in post-cessation depressed mood. ADHD symptoms ratings and number of cigarettes per day reported at baseline did not influence the post-quit mood states.

3.5. Change in ADHD symptoms

ADHD symptoms declined during the trial, significantly more with OROS-MPH than placebo treatment (Covey et al, 2010; Winhusen et al, 2010). To investigate whether this change influenced the decline in anxiety and depression after TQD, we examined a time-lag effect of change in ADHD symptoms from baseline to Week 4 on the mood ratings at Week 6. For anxiety, for which a significant main effect of abstinence was seen ( p<0.001, Table 1), adjustment for change in ADHD symptoms (β= −0.06, s.e.=0.03,p<0.05) the effect of OROS-MPH on anxiety at Week 6 was no longer significant (β = −1.05, s.e.=0.59, p=0.07). A different pattern was observed for depressed mood. With adjustment for change in ADHD symptoms (β= −0.08, s.e.=0.03, p<0.01), the significant impact of OROS-MPH on depression at Week 6 although remaining significant (β=−1.61, s.e.=0.69, p<0.05) was attenuated relative to the unadjusted treatment effect at Week 6 (β = −2.46, s.e.= 0.67, p<0.001).

3.6 Elevated anxiety and/or depressed mood after quit day

A very few cases deviated from the general trend of reductions in anxiety or depression during the trial. Of 220 completers, only four reported elevated anxiety or mood symptoms relative to baseline. One moderate reporter at baseline changed to severe at Week 6; three minimal/mild reporters at baseline moved to moderate at Week 6 after TQD. Six other reports of moderate (5) or severe (1) symptoms at Week 6 were unchanged from baseline.

4. DISCUSSION

To sum up: 1) anxiety and depressed mood declined overall, 2) abstinence showed a greater decline than non-abstinence on anxiety consistently during the trial; an effect of abstinence on depression was short-lived, observed one week after quit day but not at the end of the trial; 3) OROS-MPH improved mood relative to placebo treatment but in delayed manner; 4) higher baseline ratings on anxiety and depression predicted higher symptom scores after TQD; 5) gender and change in ADHD symptoms influenced the post-cessation trends in the mood ratings; 6) cases of worsened mood following abstinence were rare.

At the end of the trial (Week 6), depression had declined relative to baseline in similar manner according to abstinence status; whereas anxiety scores decreased significantly more among abstainers. The shared experience of standard smoking cessation treatments, i.e., nicotine patch and cognitive behavioral counseling, across the sample may explain the pervasive decline in depressed mood. Nicotine patch use has been shown to decrease depression in smokers (Korhonen et al, 2006) as well as non-smokers (McClernon et al., 2006), and cognitive behavioral counseling is an efficacious treatment for depression (Driessen and Holton, 2010). More pointedly, in a sample of persons with ADHD, nicotine patch treatment reduced negative mood and ADHD regardless of smoking or nonsmoking history (Gehricke et al, 2009). The greater mood improvement among abstainers within a week after quit day, signified by lower depression scores, may have been a transient effect brought on by feelings of elation and relief upon achievement of the targeted goal that were not experienced by non-abstainers. For the longer term, the confluence and accumulation of benefits generated by the various treatments received may have affected all participants including many of those unable to achieve abstinence.

For anxiety symptoms, decline from baseline level at both Weeks 1 and 6 was significantly greater among abstainers than non-abstainers. Thus, whereas mood ratings decreased for both anxiety and depression, the patterns over time in response to abstinence were different. Sources of the apparent greater responsivity of anxiety to cigarette withdrawal may lie in the complex relationships involving nicotine, variously anxyiolitic and anxiogenic (Piccioto et al, 2002) and specific interactions with neurobiological and psychological features of ADHD.

OROS-MPH produced better outcomes on the post-cessation mood ratings compared to placebo, albeit in delayed manner. Prior analysis had shown significant efficacy of OROS-MPH towards reduction of ADHD symptoms (Winhusen et al, 2010) and no effect of abstinence on ADHD symptoms (Berlin et al, 2012). The significant treatment effects observed at Week 6 were nullified with respect to anxiety and attenuated for depression. These trends suggest partial mediation of the decline in anxiety and depression by the change in ADHD symptoms. Thus, although direct efficacy for smoking cessation of OROS-MPH was not shown (Winhusen et al, 2010), the medication could have exerted therapeutic benefit indirectly through its ability to reduce negative affect. Increased depression mood after quit day can reduce the abstinence rate (Covey et al, 1990); positive affect during smoking cessation strongly predicts abstinence (Kenford et al, 2002).

Prior analysis had indicated no gender effect on the abstinence rate at the end of the trial (Covey et al, 2010) and further analysis herein found no gender difference in baseline anxiety (t=0.62, p=0.54) and depression (t=0.01, p=0.99) scores. Data after quit day, however, suggest a worse sensitivity to smoking cessation failure in women than men. Reduction in anxiety and depression occurred in abstinent men and women as well as in non-abstinent men, but not among non-abstinent women. If true, the distinct trend of no mood improvement in women who continue to smoke despite exposure to established treatments is a cause for concern and a rationale for further investigation. .

Only four subjects reported worsened mood relative to baseline level. This paucity of adverse psychological consequences is consistent with findings from community-based smokers (McDermott et al; 2013; Shahab et al, 2014) and smokers with depression (Berlin et al, 2010; Blalock et al, 2006). More negative mood events after quitting, described by others (Borelli et al, 1996; Stage et al, 1996), could have occurred among the 35 study dropouts but the small number affected may not have changed the results. Nevertheless, even if rare, instances of worsened mood following abstinence deserve clinical and investigative attention.

Limitations: the study had design characteristics that warrant cautionary interpretation and limited generalization to other smokers. These include the lack of a non-ADHD comparison group, exclusion of persons with a current psychiatric diagnosis other than ADHD or nicotine dependence, and the use of combination treatments. The use of abstinence and mood ratings reported at the same time points prevents assumptions of inference or causality. Nonetheless, since the post-quit anxiety and depression scores had shown marked declines relative to their pre-quit numbers, it is more likely that the post-quit events were consequences rather than instigators of the smoking cessation attempt. Because data collection took place only during the active treatment period, sustainability of our findings in the long-term and in the absence of the active treatments is unknown. Strengths: these include careful diagnosis of ADHD, the large sample size especially in light of the selectivity of the diagnostic inclusion criteria, and the use of multi-item ratings of anxiety and depressive mood measured at multiple time-points.

The main finding from this study is that anxiety and depressive symptoms may get better, not worse, with abstinence among smokers with ADHD. With the caveat that smokers in the present study received smoking cessation treatment with nicotine patch and counseling, the finding extends to smokers with ADHD previous observations of mental health benefit of cessation in other clinically diagnosed smokers and those from the general community. Additionally, through an ability to promote positive affective response to abstinence, the data suggest that OROS-MPH could be an important adjunct for achieving smoking abstinence. Validation of findings from this secondary analysis could advance discovery and development of treatments for persons dually diagnosed with nicotine dependence and ADHD.

Highlights.

♣ The preponderance of prior evidence indicates mood improvement following abstinence.

♣ Data from a smoking cessation trial were investigated to determine if that overall trend applies to smokers with ADHD.

♣ This secondary analysis on 255 smokers with ADHD treated with nicotine patch and randomized to receive adjunctive slow release methylphenidate or placebo found that anxiety and depression declined over the entire sample following smoking abstinence.

♣ The decline in anxiety and depressed mood following a target quit day was significantly greater in abstainers than non-abstainers and, in delayed manner, among those treated with methylphenidate than placebo.

♣ Instances of worsened mood following abstinence (4/255) were rare.

Acknowledgments

Funding. Supported by: NIDA K24 DA022412 (Nunes), NIDA U10 DA013035 (Nunes & Rotrosen), U10-DA013732 (Winhusen).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: Clinical Trials.gov http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Identifier: NCT00253747

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Tx: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin I, Chen H, Covey l.S. Depressive mood, suicide ideation and anxiety in smokers who do and smokers who do not manage to stop smoking after a target quit day. Addiction. 2010;105:2209–2216. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03109.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock JA, Robinson JD, Wetter DW, Schreindorfer LS, Cinciripini PM. Nicotine withdrawal in smokers with current depressive disorders undergoing intensive smoking cessation treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:122–8. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.122. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Niaura R, Keuthen NJ, Goldstein MG, DePue JD, Murphy C, Abrams DB. Development of major depressive disorder during smoking-cessation treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:534–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v57n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Levin ED, Sparrow E, Hinton SC, Erhardt D, Meck WH, March J. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. PMID: 24399556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Depression and depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Comp Psychiatry. 1990;31(4):350–4. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(90)90042-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Hu M, Winhusen T, Weissman J, Berlin I, Nunes EV. OROS-methylphenidate or placebo for adult smokers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: racial/ethnic differences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:156–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.002. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Manubay J, Jiang H, Nortick M, Palumbo D. Smoking cessation and inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity: A post hoc analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1717–1725. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443536. doi:10.1080/14622200802443536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croghan IT, Trautman JA, Winhusen T, Ebbert JO, Kropp FB, Schroeder DR, Hurt RD. Tobacco dependence counseling in a randomized multisite clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:576–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.014. doi: 10.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumyn L, French L. Hechtman Comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:673–83. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401004. 1. PMID: 19835674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretations. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Evins AE, Culhane MA, Alpert JE, Pava J, Liese BS, Farabaugh A, Fava M. A controlled trial of bupropion added to nicotine patch and behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in adults with unipolar depressive disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;6:660–6. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818ad7d6. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818ad7d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen E, Holton SD. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mood Disorders: Efficacy, Moderators and Mediators. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:537–555. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diergaarde L, Pattij T, Poortvliet I, Hogenboom F, de Vries W, Schoffelmeer AN, De Vries TJ. Impulsive choice and impulsive action predict vulnerability to distinct stages of nicotine seeking in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service report. The Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff, and Consortium Representatives. JAMA. 2000;283:3244–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke JG, Hong N, Whalen CK, Steinhoff K, Wigal TL. Effects of transdermal nicotine on symptoms, moods, and cardiovascular activity in the everyday lives of smokers and nonsmokers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:644–55. doi: 10.1037/a0017441. doi: 10.1037/a0017441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nic Tob Research. 2007;9:315–327. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet GL, Prochaska JJ, Mengis M, Cullen J, Muñoz R, Reus V, et al. Preliminary evidence of the association between the history of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and smoking treatment failure. Nic Tob Res. 2005;7:453–460. doi: 10.1080/14622200500125310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Saloojee Y. Comparison of tests to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:1435–38. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.11.1435. doi:10.2105/AJPH.77.11.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Predicting relapse back to smoking: Contrasting affective and physical models of dependence. J Consult and Clin Psychology. 2002;70:216–227. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen T, Kinnunen TH, Garvey AJ. Impact of nicotine replacement therapy on post-cessation mood profile by pre-cessation depressive symptoms. Tob Induc Dis. 2006;3:17–33. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-3-2-17. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-3-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Conners CK, Sparrow E, Hinton SC, Erhardt D, Meck WH, Rose JE, March J. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 1996;123:55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MS, Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Hankins M, Aveyard P. Change in anxiety following successful and unsuccessful attempts at smoking cessation: cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202:62–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.114389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Hiott FB, Westman EC, Rose JE, Levin ED. Transdermal nicotine attenuates depression symptoms in nonsmokers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:125–33. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0516-y. Epub 2006 Sep 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Darlene CA, Brunzell H, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1097–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00006. DOI: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Downey KK, Snedecor SM, Mehringer AM, Marks JL, Pomerleau OF. Smoking patterns and abstinence effects in smokers with no ADHD, childhood ADHD, and adult ADHD symptomatology. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Downey KK, Stelson FW, Pomerleau CS. Cigarette smoking in adult patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab L, Andrew S, West R. Changes in prevalence of depression and anxiety following smoking cessation: results from an international cohort study (ATTEMPT) Psychol Medicine. 2014;44:127–141. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000391. doi:10.1017/S0033291713000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Techniques to Assess Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press, Inc; New Jersey: 1992. pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stage KB, Glassman AH, Covey LS. Depression after smoking cessation: case reports. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:467–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v57n1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MA, Levin FR. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2001;931:251–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05783.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GT, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Lerman C, Audrain J. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms with levels of cigarette smoking in a community sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:799–805. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, et al. Profound decreases in dopamine release in striatum in detoxified alcoholics: possible orbitofrontal involvement. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12700–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3371-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hajek P. What happens to anxiety levels on giving up smoking? Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1589–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychol Med. 1989;9:981–5. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Morrison NR, Prince J. An update on the pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011 2011 Oct;11(10):1443–65. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.137. 1. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen TM, Somoza EC, Brigham GS, Liu DS, Green CA, Covey LS, Dohrer EM. Impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment on smoking cessation intervention in ADHD smokers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1680–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05089gry. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05089gry. PMID: 20492837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]