Abstract

Little is known about how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will be implemented in publicly funded addiction health services (AHS) organizations. Guided by a conceptual model of implementation of new practices in health care systems, this study relied on qualitative data collected in 2013 from 30 AHS clinical supervisors in Los Angeles County, California. Interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed using a constructivist grounded theory approach with ATLAS.ti software. Supervisors expected several potential effects of ACA implementation, including increased use of AHS services, shifts in the duration and intensity of AHS services, and workforce professionalization. However, supervisors were not prepared for actions to align their programs’ strategic change plans with policy expectations. Findings point to the need for health care policy interventions to help treatment providers effectively respond to ACA principles of improving standards of care and reducing disparities.

Keywords: Health care reform, Organizational change, Addiction health services

Introduction

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) promises to bring about major changes in how addiction health services (AHS) organizations structure and deliver care. The ACA requires AHS organizations to shift from relatively isolated specialty care services to serving as critical players in public health, responsible for meeting high expectations concerning professionalization, billing capacity, evidence-based care, and proof of medical necessity for the services they provide (Buck 2011; Pating et al. 2012; Roy and Miller 2012). Recent evaluations have shown that AHS organizations, particularly small ones, are struggling to implement many of these changes (Guerrero et al. 2014; Molfenter 2014). In particular, AHS organizations have had difficulty creating new individualized billing and outcome reporting systems and delivering evidence-based psychosocial (e.g., contingency management) and pharmacological (medication-assisted) treatment services (Guerrero et al. 2014). Research is needed to identify barriers that inhibit AHS treatment organizations from implementing changes needed to adapt to the post-ACA environment and help them develop strategies to overcome these obstacles.

The consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) describes five major domains related to the uptake and implementation of evidence-based practices and innovations in health care organizations (Damschroder et al. 2009). These domains are the nature of interventions or policy changes (e.g., ACA), outer setting (e.g., funding resources, regulation), inner setting (e.g., organizational culture, implementation climate), individuals involved in implementation (e.g., supervisors and staff), and the implementation strategy (e.g., training and supervision; Damschroder et al. 2009). This study focused on one of those domains—the individuals involved in implementation—and their views on the other four domains. Specifically, we examined the expectations of AHS clinical supervisors concerning the ACA 6 months before full implementation began in January 2014.

The perceptions of clinical supervisors are particularly informative because their job roles give them insight into the effects of change at many levels. They regularly interact with clients (as part of their clinical oversight duties), counselors (in their supervisory role), and upper management (as intermediaries between line staff and organizational leadership; Guerrero 2010, 2013). Clinical supervisors are not the sole decision makers regarding program changes, but they generally have significant influence in specialty care because their responsibilities include budgeting, human resources, service delivery, and insurance billing and reporting. These are the main components that allow programs to implement new changes (Guerrero 2010). Therefore, clinical supervisors’ perspectives offer unique insights into the expected impact of the ACA, encapsulating perceptions of how ACA implementation will affect AHS clients, counselors, and organizations as a whole.

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative study involved individual semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of 30 clinical supervisors employed by AHS programs funded by the Department of Public Health in Los Angeles County. Data collection took place as part of a larger study examining ACA implementation by AHS organizations that serve minority communities. The sampling frame for the study included all 147 Los Angeles County outpatient AHS programs that serve communities with a Latino or African American population composition of 40 % or more.

To increase sample variation and capture the perspectives of clinical supervisors in different settings, we relied on quantitative data to inform sampling in the qualitative study. We identified and recruited clinical supervisors of programs that varied by population served, geographic location, insurance coverage, program requirements, organizational capacity, and treatment approach (outpatient drug-free and medication-assisted). Thirty supervisors agreed to participate (100 % response rate). Most supervisors were women (66 %), had a graduate degree (64 %), and provided direct services (77 %). The sample was culturally diverse, featuring participants with White (32 %), African American (32 %), Latino (32 %), and Asian (3 %) backgrounds. In addition to providing clinical supervision to their employees, all participants reported spending most of their time attending to their managerial responsibilities, including financial management, human resources, service delivery, and insurance billing and reporting.

The objective of the interviews was to understand how the expansion of Medicaid (referred as Medi-Cal in California) and other expected changes due to the ACA would affect different AHS agencies in Los Angeles County. At the conclusion of interviews, participants received a $50 retail store gift card. All study policies and procedures were approved by the institutional review board of The University of Southern California and the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, Substance Abuse Prevention and Control.

Data Collection and Analysis

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted between October and December 2013. Interviews took place either in person (n = 3) or over the phone (n = 27). In-depth qualitative interviewing was used to facilitate an understanding of the perceptions and interpretations of changes supervisors ascribed to the ACA and how these perceptions affected their environments and interactions (Blumer 1969; Charon 2007). Interviews lasted between 40 and 75 min and were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed, and checked for accuracy against original audio files. Some of the interview questions included: “How do you think that Medicaid expansion and health care reform will affect the services your organization provides?” “In what ways do you think these policy changes will improve the services you provide?” “In what ways do you think these policy changes will create new challenges in service delivery?” “What are your organization’s plans for training around Medicaid expansion and health care reform?”

Transcripts were managed in ATLAS.ti, a software program that facilitates qualitative data analysis and management. Personal identifiers were removed from all transcripts. Two PhD-level researchers trained in qualitative data analysis conducted the analysis using a constructivist grounded theory approach with open, focused, and axial coding strategies (Charmaz 2006). Each transcript was initially read in its entirety. Beginning with open coding, the researchers highlighted key phrases in the transcripts and paraphrased them into condensed open code, capturing the essence of each phrase. After 20 % of the transcripts had been coded, the researchers compared codes to ensure consistency. The researchers used open codes to create focused codes, or clusters of similar or related codes, and continued to meet regularly to discuss the content of each transcript to identify emerging categories. After completing open and focused coding, a preliminary codebook that listed the most recurrent and initial codes and categories was developed (Charmaz 2006). The remaining interview transcripts were analyzed using the codes established in the codebook. The codebook consisted of 29 code families and 93 codes with definitions.

After the codebook was established, two researchers separately coded all 30 interviews and conferred after all transcripts had been coded. In these meetings, they compared coding patterns and resolved disagreements related to code definitions. This iterative process helped enhance intercoder reliability and led to a well-defined codebook (Guest and MacQueen 2008). The dependability of the findings in the study was established by the transparent coding process and intercoder verification.

To visually present the data for further analysis, focused codes were used to create data-family matrices. Analysis within and across cases and coding categories of the families led to the construction of several overriding themes, or axial codes, related to perceptions and expectations regarding the ACA. At the axial level of coding, two researchers worked together to establish intercoder consistency by comparing data and interviews for variations and nuances to create descriptive categories within each theme. From these conversations, subcategories that described the characteristics and dimensions of the categories were articulated. Throughout the analysis process, researchers focused on using the data to understand participants’ perceptions and expectations regarding the ACA. Additionally, the authors maintained memos related to analytic decisions, consulted with other members of the research team, and discussed the relationships among codes that emerged from the data (Miles and Huberman 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1998).

Results

Table 1 describes the characteristics of study participants and the organizations that employed them. Most supervisors were employed at small programs serving fewer than 200 clients a month, mostly Latino or African American clients and Medi-Cal recipients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of addiction health services organizations (N = 30)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Client characteristics | ||

| More than 50 % Latino | 15 | 50 |

| More than 50 % African American | 7 | 23 |

| More than 50 % White | 6 | 20 |

| 50 % Latino and 50 % African American | 1 | 3 |

| 33 % Latino, 33 % African American, and 33 % White | 1 | 3 |

| Treatment model | ||

| Outpatient drug-free | 24 | 80 |

| Medication-assisted | 6 | 20 |

| ACA training | ||

| Received ACA training | 23 | 77 |

| Did not receive ACA training | 7 | 33 |

| ACA training quality | ||

| Reported that training was comprehensive | 1 | 3 |

| Reported training was minimal and expected more | 22 | 73 |

| Did not describe or receive training | 7 | 23 |

| Special client populationsa | ||

| Homeless | 16 | 39 |

| Dual diagnosis | 10 | 24 |

| Pregnant | 3 | 7 |

| HIV/AIDS | 3 | 7 |

| Alternative sentencing | 1 | 2 |

| Methadone maintenance | 5 | 12 |

| Trauma | 1 | 2 |

| None | 2 | 5 |

| Percentage of clients on Medi-Cal | ||

| 0 % | 2 | 7 |

| 1–25 % | 6 | 20 |

| 26–50 % | 6 | 20 |

| 51–75 % | 8 | 26 |

| 76–100 % | 8 | 26 |

| Other forms of insurance accepteda | ||

| Self-pay | 14 | 41 |

| Healthy Way LA (ACA bridge program) | 5 | 15 |

| Private insurance | 4 | 12 |

| County reimbursement | 3 | 9 |

| None | 5 | 15 |

| Unknown | 3 | 9 |

| Client capacity | ||

| 0–100 | 10 | 33 |

| 101–200 | 7 | 23 |

| 201–300 | 3 | 10 |

| 301–400 | 1 | 3 |

| Unknown | 9 | 30 |

ACA Affordable Care Act

Participants (supervisors) were able to select more than one category

Of the 30 clinical supervisors interviewed, 23 said that they had received training about the ACA but reported that this training was minimal and that they expected more training in the near future. More than half of the participants (n = 17) mentioned that they had no definite information about upcoming trainings on the ACA. In addition, supervisors reported that the majority of preparation for ACA implementation involved efforts to engage and enroll clients in new Medi-Cal programs. These efforts including training staff members as certified enrollment counselors and placing more energy as an organization into “enrolling clients and keeping clients on some form of insurance”.

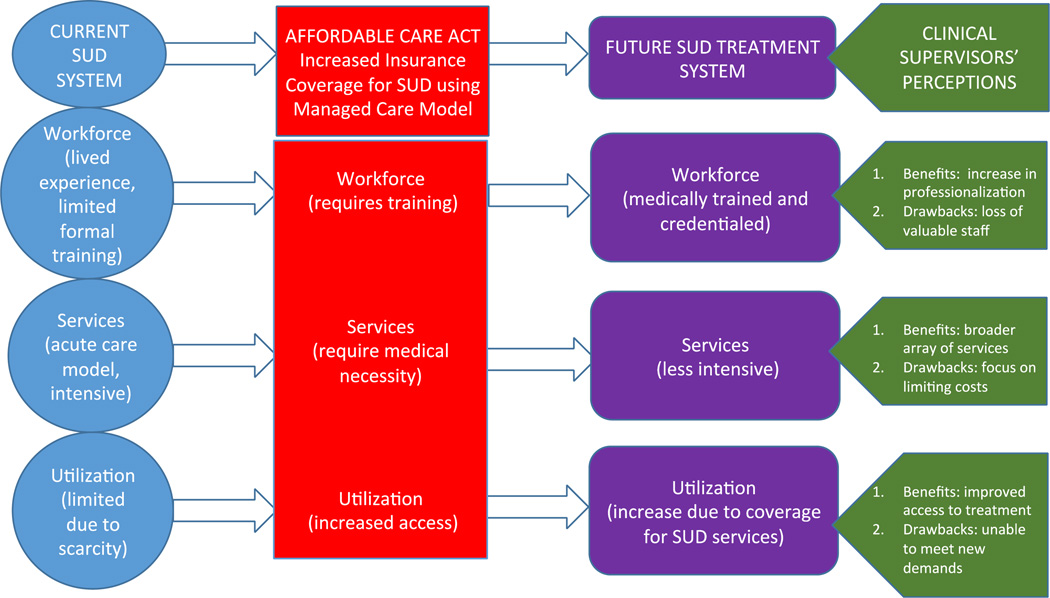

Three main themes emerged from discussions about the expected effects of the ACA on AHS organizations. Participants expected that the ACA would have a significant influence on their organizations by: (a) increasing use of AHS; (b) altering the duration and intensity of the services they provide; and (c) facilitating workforce professionalization. In each of these domains, respondents discussed expected positive and negative effects (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Themes perceived by AHS supervisors in 2013 before enactment of ACA public insurance expansion. ACA Affordable Care Act, AHS addiction health services, SUD substance use disorder

Increased Utilization of AHS

A majority of participants (n = 26) said they expected the ACA will significantly increase utilization of AHS. In particular, participants stated they believed that the expansion of Medicaid will increase AHS utilization by providing affordable care to low-income individuals who previously could not afford it. In addition, participants said the inclusion of AHS benefits in insurance plans will improve access to treatment by improving mechanisms of linkages and referrals to specialty AHS care. Whereas before the ACA, as one participant explained, prospective clients would “have to go out and look for it separately” from other aspects of their health care, AHS under the ACA will be coordinated, eligible for reimbursement, and accessed in the same way as other specialty health services.

Although most participants (n = 20) said they believed that increased use of AHS will be beneficial, several expressed reservations about the potential consequences for their treatment organizations. Some (n = 5) said they worried that the ACA will increase access to AHS so quickly and dramatically that their organizations will not be able to meet demand; statements that an influx of clients who urgently need intensive AHS would inundate treatment organizations, particularly smaller ones with limited capacity, were common among respondents. Some participants (n = 3) said they expected that the ACA will create a flood of clients that is not only too large but also too socioeconomically diverse for their organization’s comfort. For example, one respondent who worked at an agency that serves mostly upper-middle-class clients expressed concern that the ACA would compromise the agency’s niche in the AHS market by bringing in a lower-income clientele. Another participant expressed concern that by making treatment more accessible, the ACA will attract clients with relatively well-controlled substance use conditions or who are unwilling to put in the work needed to achieve and sustain recovery. These supervisors said they expected that by increasing the demographic and socioeconomic diversity of clients while also bringing in more clients with varying levels of addiction severity and willingness to change, the ACA would pose challenges for their treatment staff.

Supervisors also reported concerns that the addition of large numbers of clients to their clinic caseloads would overwhelm their organizations’ treatment capacity. As one participant stated:

One of the things that we [are] concerned about is the capacity and the influx of individuals who now would be eligible for services, and our capacity to meet their needs. We [are] looking at our staffing and seeing for the program … the capacity may then have to be increased [or else we will be] looking at a waiting list. We [are] anticipating an influx of clients who really need the service, and we wouldn’t be able to provide it because of the staff.

Duration and Intensity of AHS

Most participants (n = 18) said they expected that the ACA will have a significant effect on the duration and intensity of services delivered by their organizations. Some participants (n = 6) said they believed that the ACA may increase client access to preventive services to address risky drug use behaviors that can lead to drug dependence. Whereas the current treatment system focuses on treating the most severe cases of addiction, the increased availability of early intervention services may enable clients to receive help before they develop more acute substance use conditions. One participant stated that increased preventive care will be an improvement over the current system’s focus on treating substance use disorders “when they’re already too sick”. In addition, some participants said they expected that the ACA will improve their ability to deliver outpatient and medication-assisted treatment services.

However, some supervisors (n = 9) expressed serious concerns about the effects of the ACA and increased reliance on reimbursement from insurance companies in particular on service duration and intensity. Participants said insurance companies responsible for paying for care based on the ACA will be more focused on limiting costs than ensuring comprehensive care for substance use disorders. Consequently, they said they feared that insurance companies will try to force clients into less intensive and briefer treatment than clinically indicated; in practice, they said they expected insurance companies would push clients toward outpatient care instead of inpatient care, into group therapy instead of individual therapy, and limit treatment episodes to 3 months instead of the standard 6–12 months of treatment.

Moreover, as insurance providers become more involved in paying for addiction treatment, some participants (n = 7) said they expected clients and providers to lose control over critical decisions related to the initiation of AHS treatment. As one respondent stated, currently “if a person is disclosing that they have a history with substance use disorders and there’s detriment in their day-to-day life, their employment is affected, their house is affected, their health is affected, that plea in itself [is sufficient to be] approved for services”. However, if insurance companies make decisions about medical necessity, “we’re going to be dependent on what they approve” before initiating treatment.

In a similar vein, some participants (n = 9) reported concerns that insurance company requirements that treatment be authorized before care is delivered could inhibit service delivery and force many clients to prematurely discontinue treatment. One participant stated that currently “we don’t have to go back every week or every month for every six sessions and get another extension and justify why the person needs additional care”. However, with insurance companies, supervisors said they expected they will have to continually justify the medical necessity of AHS, something they stated will be difficult if clients have made progress toward recovery and are not in immediate danger of relapse. As one interviewee stated:

In theory, I’m for health care insurance … because I know there’s a lot of individuals that need coverage. … [But] if there’s a relapse in the future, or if there’s reoccurring [substance use disorders], we still don’t know what [services for that] are going to look like.

Workforce Professionalization

Due to changes implemented by the ACA, several participants (n = 10) predicted that insurance companies would require that their organizations employ a more “professionalized” workforce. They said they expected a need to hire new staff members with professional licenses or encourage existing employees to obtain additional credentials. Supervisors at seven clinics reported that their clinical employees lacked higher education and only had credentials from state substance abuse counselor accreditation agencies. Although these accreditations were sufficient to provide AHS in the past, seven participants said they expected that insurance companies would require treatment providers to have higher education degrees and formal behavioral health licenses to bill for services. As one respondent explained, “A lot of agencies—we’re not used to having substance abuse counselors or any kind of degrees. That’s going to be a challenge”.

However, a few participants (n = 3) acknowledged that the shift toward a more formally trained workforce would improve the quality of services delivered by their organizations. Some participants reported that in their treatment organizations, counselors who were not exposed to a formal graduate education on professional boundaries have difficulty establishing and maintaining appropriate professional boundaries with clients and developing appropriate therapeutic relationships. As staff members become more formally trained in behavioral health approaches, participants said they expected quality of clinical care to improve.

However, the same seven participants who reported that some of their staff members lacked higher degrees expressed concern that they will lose valuable employees due to pressure to phase out providers who are not clinically licensed. Though they acknowledged that current employees could theoretically pursue further education and training to obtain degrees and licenses needed to bill insurance companies in the future, participants said they were doubtful that their counselors will have the financial resources or time to invest in formal career development. The loss of less formally educated and unlicensed employees, participants said, would have a dramatic effect on the character of services their organizations deliver in the future. As several participants noted, most substance abuse counselors enter the AHS workforce after overcoming their own struggles with addiction, and their personal experience is a valuable tool for engaging clients in treatment and building therapeutic alliances. “The clients really respond to them and share their life experiences”, one respondent said. “I see great value in that in terms of building relationships in the treatment process”.

A common concern of participants was that AHS organizations lack capacity to handle the bureaucratic tasks and paperwork associated with billing insurance companies for services. Noting that insurance providers require a constant flow of formal assessments, reviews, and clinical reports, participants said their organizations will likely face significant challenges keeping up with new expectations regarding documentation and paperwork with their current staff. “It’s going to require a lot of manpower … people with some knowledge of that kind of stuff”, noted one respondent. “[But] we’re not having the funding to hire the new staff or resources”.

Discussion

Clinical supervisors said they expected that the implementation of the ACA would affect their organizations, their staff, their services, and their clients by increasing use of AHS, altering the duration and intensity of AHS services, and facilitating the professionalization of the AHS workforce. In each of these three domains, participants recognized the potential benefits (e.g., increased access to services, more preventive care for substance use disorders, improved quality of care) and possible drawbacks (e.g., difficulty serving new populations, insurance-imposed limitations on care, potential loss of staff members with lived experience with substance use disorders) of expected changes related to the ACA.

In explaining their expectations for change, supervisors touched on aspects of the five major domains of the CFIR model (Damschroder et al. 2009). They stressed how the ACA (e.g., policy changes) would affect funding resources and regulation from Medi-Cal (outer setting) and how programmatic changes in the workforce may affect the culture of programs (inner setting) and interventions to implement new services and quality standards (implementation strategy). Before full implementation began in January 2014, they generally reported expectations that the ACA would bring significant positive changes to the AHS field, but expressed ambivalence about whether or not the costs of these changes would outweigh the benefits for their treatment organizations.

The fact that supervisors said they believe that the ACA will have positive effects is encouraging, because it indicates that they may actively contribute to rather than hinder the implementation of required changes in AHS organizations to adapt to the post-ACA environment. Conversely, the fact that they still had significant reservations about the ACA’s impact is noteworthy and an indicator of obstacles that AHS organizations may encounter as they implement changes related to the ACA. To help facilitate successful ACA implementation in AHS organizations, policy makers and AHS organization leaders should consider concerns about the ACA expressed by clinical supervisors when designing future training and technical assistance activities.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the purposively selected sample of respondents was drawn from a discrete area in Los Angeles County and the qualitative approach prevents these data from being used to make generalizable statements. AHS organizations in California are relatively understaffed and in need of professional development (Padwa and Oeser 2013), so findings reported here may not be applicable to AHS organizations in other states or regions that are better integrated with local behavioral health and medical systems (e.g., metropolitan areas in Oregon, Massachusetts, and New York). However, a significant portion of AHS organizations across the country—mainly represented by small programs with three or fewer counselors—face challenges related to staff training and preparedness to integrate with the medical system that are similar to those documented in California (Dilonardo 2011; McLellan et al. 2003; Molfenter 2014).

Conclusions

This study highlights the need for professionals in the AHS field to be poised for change to ensure that the ACA’s insurance coverage expansion provision has the desired effect of enhancing access and quality of care and improving population health among low-income minorities accessing AHS. Health care management policy makers seeking to improve system readiness to implement policy with fidelity should consider provider interpretations of ACA policies and contemplation of enacting changes. By integrating training and dissemination sessions that may improve the fidelity of policy implementation in public health service systems, more effective implementation of critical components of the Medicaid expansion can be accomplished in AHS. Future research should inform interventions to enhance clinical supervisors’ knowledge as they face a degree of incongruence between the potential benefits of public health insurance expansion and the limited financial and technical assistance resources available to support the effective implementation of the ACA.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research and manuscript preparation was provided by a National Institute of Drug Abuse research grant (R33DA035634-03, PI: Erick Guerrero) and an implementation fellowship training grant (R25 MH080916, PI: Enola Proctor). The authors would like to thank treatment providers for their participation in this study and appreciate Drs. Gary Tsai and Tina Kim from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Substance Abuse Prevention and Control for their support. We also would like to acknowledge Eric Lindberg, from the School of Social Work at University of Southern California, for proofreading this paper.

References

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs. 2011;30:1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charon JM. Symbolic interactionism: An introduction, an interpretation. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation research. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilonardo J. Workforce issues related to: Physical and behavioral healthcare integration: Specifically substance use disorders and primary care. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/workforce/Workforce_Issues_Related_to_Physcial_and_BH_Integration.pdf.

- Guerrero EG. Managerial capacity and adoption of culturally competent practices in outpatient substance abuse treatment organizations. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG. Managerial challenges and strategic solutions to implementing organizational change in substance abuse treatment for Latinos. Administration in Social Work. 2013;37:286–296. doi: 10.1080/03643107.2012.686009. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Organizational capacity for service integration in community-based addiction health services. American Journal of Public Health. 2014a;104:e40–e47. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301842. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, He A, Kim A, Aarons GA. Organizational implementation of evidence-based substance abuse treatment in racial and ethnic minority communities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014b;41:737–749. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0515-3. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0515-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, editors. Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00156-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter TD. Addiction treatment centers’ progress in preparing for health care reform. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;46:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.018. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwa H, Oeser B. White paper on California substance use disorder treatment workforce development. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pating DR, Miller MM, Goplerud E, Martin J, Ziedonis DM. New systems of care for substance use disorders: Treatment, finance, and technology under health care reform. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;35:327–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.004. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, I II, Miller MM. The medicalization of addiction treatment professionals. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44:107–118. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.684618. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.684618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]