Abstract

The bone marrow microenvironment contains a heterogeneous population of stromal cells organized into niches that support hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and other lineage-committed hematopoietic progenitors. The stem cell niche generates signals that regulate HSC self-renewal, quiescence, and differentiation. Here, we review recent studies that highlight the heterogeneity of the stromal cells that comprise stem cell niches and the complexity of the signals that they generate. We highlight emerging data that stem cell niches in the bone marrow are not static but instead are responsive to environmental stimuli. Finally, we review recent data showing that hematopoietic niches are altered in certain hematopoietic malignancies, and we discuss how these alterations might contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Conceptual characteristics of the stem cell niche

The hematopoietic system requires constant replenishment of its end products, a large and heterogeneous array of terminally differentiated cells and corpuscles, which are essential for oxygenation, clotting, and immunity. Because this daily requirement continues throughout the life of an individual, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), the cells at the apex of this well-orchestrated hierarchy, require exceptional control of fate allocation. HSCs are routinely used for clinical applications, as in stem cell transplantation, and represent an important model to study mechanisms of stem cell control. Certainly, stem cell fate decisions are likely to be determined, in part, by cell autonomous signals1; however, the inception of the niche hypothesis was motivated by observations that stem cell potential is dependent on microenvironmental clues. Indeed, the initial definition of niche states that “the stem cell is seen in association with other cells which determine its behavior.”2 Although this definition was conceived to reconcile differences between spleen colony-forming cells and HSCs, the existence of regulatory stem cell niches was first demonstrated in the Drosophila gonad.3-5 Subsequently, niches were found to be critical for adult stem cells in skin, intestine, and brain.6-8 The first in vivo proof of microenvironmental regulation of HSCs in mammals used genetically altered murine models, and initiated a series of sophisticated experiments aimed at finding which components of the bone marrow microenvironment regulate HSCs.9-11 In this review, we will focus on components of the HSC niche where the concept of heterogeneity underlines the multiple cell fate choices available to the stem cell. We will also discuss how both physiologic and pathologic processes modulate multiple components of the niche, introducing evidence that the microenvironment contributes to the pathophysiology of disease, and conclude by predicting the potential of therapeutic manipulation of the niche.

Anatomy of stem cell niches in the bone marrow

Recent advances in imaging technologies have greatly improved our understanding of the organization of the bone marrow. The bone marrow is a highly vascular tissue.12,13 In long bones, central longitudinal arteries give rise to radial arteries that in turn branch into arterioles near the endosteum.12 The transition from arterioles to venous endothelium occurs in close proximity to the endosteum. Venous sinusoids extend back toward the central cavity where they coalesce into a large central sinus. Despite the high vascular density, the bone marrow is hypoxic, with the lowest oxygen tensions found near sinusoids in the central cavity.14

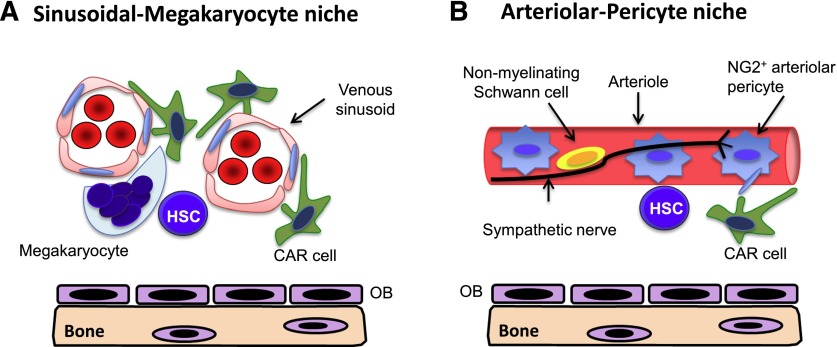

Initial studies using labeled HSC-enriched cell populations transplanted into recipients suggested a mostly endosteal location for HSCs.15-17 However, more recent studies suggest that the majority of HSCs are perivascular and enriched in the highly vascular endosteal region.12,18 This region contains a complex network of stromal cells that have been implicated in HSC maintenance including osteolineage cells, endothelial cells (both arteriolar and venous), pericytes, CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)-abundant reticular (CAR) cells, sympathetic nerves, and nonmyelinating Schwann cells. Recent evidence supports the presence of 2 stem cell niches in the bone marrow: the arteriolar niche and the sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niche (Figure 1). Here, we briefly review these niches separately, although whether they are truly distinct niches is currently unclear. Of note, both the arteriolar and sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niches localize to the endosteal region, placing osteolineage cells in/near these niches. However, it is clear that a subset of HSCs is located in the central marrow.19,20 Indeed, Sean Morrison and colleagues recently reported that HSCs were more common in the central marrow than near bone surfaces.20 Of note, in this study, HSCs were identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of the Ctnnal1 gene. Clearly, much of the controversy in the field may be due to the different experimental approaches used to localize HSCs in the bone marrow, as carefully reviewed elsewhere.21 It will be important to determine whether there are functional differences in HSCs that localize to these different niches. It is also worth noting that many of the key niche factors that regulate HSCs (eg, CXCL12, stem cell factor, and transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]) are produced by several stromal cell populations. Thus, there may be a degree of functional redundancy between the various stromal cell populations in their support of HSCs.

Figure 1.

Stem cell niches in the bone marrow. Current data support 2 niches in the bone marrow. (A) Sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niche. The sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niche contains sinusoidal endothelial cells, megakaryocytes, and CAR cells. (B) Arteriolar-pericyte niche. The arteriolar niche includes arteriolar endothelial cells, NG2+ arteriolar pericytes, CAR cells, sympathetic nerves, and nonmyelinating Schwann cells. (A-B) A subset of HSCs localize near the endosteum, placing osteoblast lineage cells (OB) in these niches.

Arteriolar niche

Paul Frenette’s group showed that quiescent HSCs preferentially localize to arterioles in the endosteal region.22 At its core, the arteriolar niche is composed of endothelial cells and nestin-GFPbright NG2+ arteriolar pericytes, both of which regulate HSCs. Bone marrow endothelial cell expression of stem cell factor (SCF),23 CXCL12,24,25 and E-selectin26 contribute to HSC maintenance, and regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells is required for hematopoietic recovery from myeloablation.27,28 Arteriolar pericytes express high levels of the niche factors CXCL12 and SCF, and conditional ablation of NG2+ cells is associated with increased HSC cycling and a loss of HSC-repopulating activity.22 Of note, fibroblastic colony-forming unit activity, which is associated with mesenchymal stem activity, is enriched in the nestin-GFPbright stromal cell population,22 which is consistent with prior studies implicating mesenchymal stem cells in HSC maintenance.25,29

Arterioles are decorated with sympathetic nerves and nonmyelinating Schwann cells, which have been reported to modulate HSC activity in the bone marrow. Sympathetic nerves regulate bone marrow stromal cell CXCL12 expression, thereby regulating HSC egress from the bone marrow.30,31 Nonmyelinating Schwann cells are a major source of activated TGF-β in the bone marrow,32 which contributes to HSC quiescence.33

Sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niche

Two recent studies suggest the presence of a stem cell niche defined by megakaryocytes in venous sinusoids.19,34 Approximately 20% of phenotypic HSCs localize directly adjacent to megakaryocytes in mice. Megakaryocytes are intimately associated with the bone marrow sinusoidal endothelium, extending cytoplasmic protrusions into the sinusoids to produce platelets. Conditional ablation of megakaryocytes results in increased HSCs and HSC cycling, and data suggest that megakaryocytes normally restrain HSC proliferation through production of CXCL4 and TGF-β.19,34 Conversely, megakaryocyte production of fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1) is thought to play a key role in supporting HSC and osteoblast expansion recovery following myeloablative therapy.34-36 Of note, the impact of the loss of HSC quiescence after megakaryocyte ablation on HSC self-renewal is an important but currently unanswered question. The sinusoidal-megakaryocyte niche also contains sinusoidal pericytes. Sinusoidal pericytes are not well characterized but likely overlap considerably with several previously defined mesenchymal stromal cell populations, including CAR cells, leptin-receptor+ stromal cells, and nestin-GFP+ stromal cells, each of which has been implicated in HSC maintenance.23,37-40

Osteolineage cells

The localization of HSCs to endosteal sites supported studies of the role of osteoblast lineage cells (which we will refer to as osteolineage cells) in the HSC niche. Indeed, the skeleton is absolutely necessary for mammalian hematopoiesis, as is demonstrated by genetic studies where lack of osteoblastic differentiation blocks hematopoiesis.41 Osteolineage cells produce a number of cytokines implicated in HSC regulation, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF),42 thrombopoietin,43,44 angiopoietin 1,11 and CXCL12.45 Expansion of osteolineage cells through targeted activation of parathyroid hormone receptor 19 or through conditional inactivation of bone morphogenic protein receptor type 1A10 is associated with an increase in HSCs. Conversely, conditional ablation of osteolineage cells is associated with a loss of HSCs in the bone marrow and extramedullary hematopoiesis.46

Despite these findings, the contribution of osteolineage cells, particularly mature osteoblasts, to HSC maintenance is controversial. In fact, a global increase in osteoblastic cells is not sufficient to expand HSCs because, for example, treatment of mice with the bone anabolic agent, strontium, leads to osteoblastic expansion but has no effect on HSC number or function.47 Conversely, in mice with chronic inflammatory arthritis, resulting in osteoblast suppression, HSCs are normal.48 Finally, conditional deletion of Cxcl1224,25 or Kitl23 from mature osteoblasts has no effect on HSCs. These apparently discrepant data may be due, at least in part, to the heterogeneity of osteolineage cells. In particular, a recent study showed that more primitive osteolineage cells express higher levels of SCF and CXCL12 and support the long-term-repopulating activity of HSCs better than more differentiated osteolineage cells.49 Thus, current evidence suggests that immature osteolineage cells rather than mature osteoblasts are required for HSC maintenance. However, the fact remains that a subset of HSCs is periendosteal, and the question of whether osteoblasts may play a role in the development of such niches or in their maintenance under specific conditions is still open. Data also suggest that cells of the osteoblastic lineage may provide support for lymphopoiesis and lymphoid tissue function.50-52 Indeed, ablation of osteolineage cells suppresses B and T lymphopoiesis in mice.50,52 Moreover, depletion of the chemokine CXCL12 from osteolineage cells results in loss of lymphoid progenitors in the marrow.24 Together, these studies suggest that osteolineage cells provide a specialized niche for lymphoid progenitors.

There also is evidence implicating osteocytes, which are differentiated osteolineage cells buried in compact and trabecular bone, in the regulation of hematopoiesis. Ablation of osteocytes results in impaired HSC mobilization from the bone marrow in response to G-CSF.53 Conversely, loss of Gsα in osteocytes results in enhanced myelopoiesis through increased local production of G-CSF.54 Collectively, these data suggest that specific stages of osteoblast maturation may regulate distinct types of hematopoietic progenitors.

Physiological regulation of stem cell niches in the bone marrow

There are emerging data that stem cell niches in the bone marrow are not static but instead are responsive to external cues. In this section, we highlight studies that describe alterations in stem cell niches in the bone marrow in response to physiological cues.

Stem cell mobilization

Perhaps the best-characterized example of extrinsic factors regulating stem cell niches in the bone marrow is cytokine-induced HSC mobilization. A shared feature of many hematopoietic cytokines, including G-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, thrombopoietin, kit ligand, and flt3 ligand, is their ability to mobilize HSCs from the bone marrow to blood.55 G-CSF, the prototypical mobilizing agent, induces HSC mobilization by altering the bone marrow microenvironment. Specifically, G-CSF suppresses mature osteoblasts,30,56,57 while increasing CAR cell numbers in the bone marrow.58 G-CSF suppresses CXCL12 expression in multiple mesenchymal stromal cell populations,57,59,60 endothelial cells,60 and CAR cells.58 CXCL12 signaling through CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) provides a key retention signal for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the bone marrow, and conditional deletion of Cxcl12 from stromal cells or pharmacologic inhibition of CXCR4 results in robust HSC mobilization.24,25,61 Indeed, studies of Cxcr4−/− bone marrow chimeras show that disruption of CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is the dominant mechanism by which G-CSF induces HSC mobilization.59

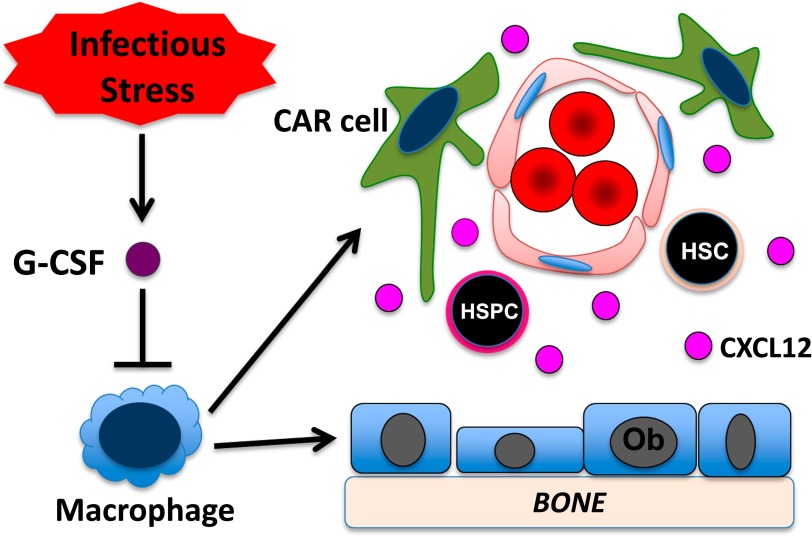

The G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) is not expressed on mesenchymal bone marrow stromal cells.40 Accordingly, studies of G-CSFR–deficient bone marrow chimeras show that G-CSFR expression on hematopoietic cells is sufficient to mediate robust HSPC mobilization.62 There is emerging evidence that monocytic cells in the bone marrow play a major role in regulating HSPC trafficking at baseline and in response to G-CSF. We generated transgenic mice in which expression of the G-CSFR is restricted to CD68+ monocytic cells.63 Treatment of these mice with G-CSF induces a marked suppression of osteoblast activity, decreased CXCL12 expression, and robust HSPC mobilization. Conditional ablation of monocytic cells using pharmacologic or genetic approaches results in osteoblast suppression, robust HSPC mobilization, and decreased expression of key stromal niche factors, including CXCL12, kit ligand, and angiopoietin-1.64,65 To further define the monocytic lineage cell population in the bone marrow that contributes to stem cell niche maintenance, Chow et al ablated CD169+ macrophages using transgenic mice that express the diphtheria toxin receptor under control of CD169 regulatory sequences.66 They showed that ablation of CD169+ macrophages resulted in modest HSPC mobilization and decreased expression of CXCL12, Kit ligand, and angiopoietin-1 from nestin-GFP+ bone marrow stromal cells. Together, these studies suggest a model in which G-CSF acting through a monocytic cell intermediate in the bone marrow regulates the activity of mesenchymal stromal cells in the bone marrow (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model of G-CSF–induced HSPC mobilization. Under basal conditions, monocytic cells in the bone marrow (here shown as macrophages) provide signals that help maintain CXCL12 expression from multiple mesenchymal stromal cell populations, including osteoblasts (Ob) and CAR cells. In response to infection, systemic levels of G-CSF are often increased. G-CSF signaling in monocytic cells leads to a loss of macrophages in the bone marrow. This, in turn, results in reduced CXCL12 expression from mesenchymal stromal cells and HSPC mobilization.

Circadian rhythms

The number of HSCs in the blood cycles in a circadian fashion in mice and humans.31,67 Frenette’s group showed that photic signals stimulate nerves in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, leading to increased norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerves in the bone marrow.31 The resulting activation of β3-adrenergic signaling in bone marrow stromal cells suppresses CXCL12 expression leading to HSC mobilization. Interestingly, a recent study suggested that chronic stress induces increased β3-adrenergic signaling in the bone marrow, resulting in reduced stromal CXCL12 expression and leukocyte mobilization.68

Neutrophils have also been shown to contribute to the circadian fluctuation in circulating HSCs. Hidalgo’s group showed that aged neutrophils selectively home to the bone marrow where they trigger macrophage activation.69 This, in turn, suppresses stromal CXCL12 expression and induces HSC mobilization.

Toll-like receptor signaling

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of pattern recognition receptors that are expressed on HSPCs,70 endothelial cells,71 and several mesenchymal stromal cell populations, including nestin-GFP+ stromal cells31 and CAR cells.58 Recent data show that TLR signaling regulates basal and stress hematopoiesis, at least in part, through alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment. A number of TLR ligands may be produced during infection, including lipopolysaccharide, single-stranded RNA, and peptidoglycans. Boettcher et al showed that LPS-induced increases in granulopoiesis are dependent on the stimulation of TLR4 on endothelial cells with subsequent increased production of G-CSF from an uncertain cellular source.72 Likewise, Burberry et al showed that infection of mice with Escherichia coli induced HSPC mobilization and decreased bone marrow CXCL12 expression that was dependent, in part, on TLR4 signaling in radio-resistant (likely stromal) cells.73 Intriguingly, Rutkowski et al showed the gut microbiota may regulate basal hematopoiesis through a TLR5-dependent mechanism leading to increased expression of the mobilizing cytokine, interleukin-6 (IL6).74 Of note, in addition to their effects on stromal cells, TLR ligands may regulate hematopoiesis in a cell-autonomous fashion.75

Hormonal signals

The parathyroid hormone (PTH) became a widely used tool in studying activation of the HSC niche76,77 after the identification of indirect HSC expansion in genetic and pharmacologic models of PTH receptor activation in osteolineage cells.9,78,79 Notably, activation of the PTH receptor solely in osteocytes is not sufficient to expand HSPCs, suggesting differential effects of PTH on osteolineage cells depending on maturation stages.9,80 The ability of PTH (1-34) to promote HSPC support and maintenance is likely the result of its stimulatory effect on various cell types in the marrow, including osteolineage cells and, indirectly, osteoclasts and even macrophages.81 PTH (1-34) can also act through T cells to promote Wnt10b secretion, increasing canonical Wnt signaling in both osteoblasts and HSCs. This activation of Wnt signaling promotes a bone anabolic effect on osteoblasts, and expansion of select HSPC populations.82,83 Wnt10b also stimulates expression of Jagged1 on osteoblasts, increasing their support capacity for the expanded short-term HSC (ST-HSC) population.83 In humans, PTH may have similar effects, as both postmenopausal women treated with teriparatide (PTH 1-34) and patients with primary hyperparathyroidism have increased circulating HSPCs.84-86 Whether PTH signaling is a physiologic regulator of the HSC niche is currently not known.

Another hormone recently found to modulate HSCs is estrogen (E2). It is well known that pregnancy is accompanied by expansion of the hematopoietic system, leading to much data suggesting a role for E2 in regulation of hematopoietic cells. For example, administration of 17β-estradiol to male mice leads to an increase of committed B-cell progenitors at the expense of HSPCs.87 Other studies have shown that estrogen treatment in mice depletes the number of T-cell lineage progenitors.88 In contrast, a direct effect of E2 on HSCs was only recently explored by Nakada et al. This group demonstrated expression of E2 receptors in HSCs, and found that E2 in pregnant females promotes HSPC self-renewal. They reported an increase in cycling HSPCs in female compared with male mice, a phenomenon that decreased with ovariectomy (OVX).89 This HSC response to E2 was predominantly cell-autonomous and depended on estrogen receptor-α because conditional inactivation of this receptor blocked female-specific HSC cycling.89 Other data have also supported a role for the niche in E2-dependent HSC changes. Li et al found that removal of E2 by OVX leads to expansion of ST-HSCs.90 This ST-HSC expansion was T-cell dependent because OVX of mice without T cells (TCRβ−/−) did not have expansion of ST-HSCs.90 The authors found that mice with OVX had increased expression of CD40 ligand, which stimulated T cells to secrete Wnt10b, a molecule previously shown to expand ST-HSCs.83 Therefore, E2 appears to engage HSCs both directly and indirectly through alterations in the niche. Because both effects are likely present during physiologic changes (such as pregnancy and the hypoestrogenism associated with lactation and menopause), E2 likely modulates HSCs and the niche in a dynamic fashion. In addition, E2 antagonism may initiate recovery mechanisms, which return the system to homeostasis. Together, these data demonstrate how hormones may engage HSCs both directly and through their niche.

Prostaglandin E2

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an inflammatory lipid produced by cyclooxygenase-2 capable of regulating HSCs.91 Although PGE2 is able to act directly on HSCs, as they express all receptors for PGE2,92 evidence also suggests that the HSC niche is activated by PGE2 and contributes to the effects of PGE2 on HSCs. For example, pretreatment of mesenchymal stem cells with dimethyl-PGE2 enhances their ability to support HSPC colony formation in vitro.93 PGE2 rapidly increases in the marrow microenvironment after radiation, and treatment of mice with dimethyl-PGE2 after sublethal radiation injury suppresses apoptotic gene expression in HSPCs and stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 activity in the marrow, specifically in a population of α-smooth muscle actin+ macrophages that participate in HSC support.94,95 Moreover, the PGE2 receptor EP4 (PGE receptor 4) regulates trafficking of HSCs in the bone marrow through modulation of mesenchymal/osteolineage populations.96 These functions of PGE2 are operative in nonhuman primates and healthy volunteers,96,97 providing a rationale for the use of drugs that modulate PGE2 expression to regulate HSPC function in the clinical setting.

Stem cell niches in the pathogenesis of hematopoietic malignancies

Recent data suggest a prominent role of the bone marrow microenvironment in the initiation and/or progression of hematopoietic malignancies, including myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and acute leukemia. Emerging data support the concept of a “malignant microenvironment” where the malignancy co-opts the normal microenvironment to increase its own support, while suppressing normal hematopoiesis. In this section, we highlight recent data implicating alterations in HSC niches in the pathogenesis and evolution of hematopoietic malignancies.

Myeloproliferative diseases

In murine models, alterations in bone marrow stromal cells are sufficient to initiate MPNs. Bone marrow transplantation studies show that deletion of retinoic acid receptor γ,98 the DNA-binding domain of RBP-Jk (necessary for canonical downstream Notch signaling),99 or the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma100 in bone marrow stromal cells results in an MPN-like phenotype. Moreover, deletion of Mib1, which is required for Notch signaling, results in an MPN-like phenotype, further implicating defective Notch signaling in bone marrow stroma in the pathogenesis of MPN.101

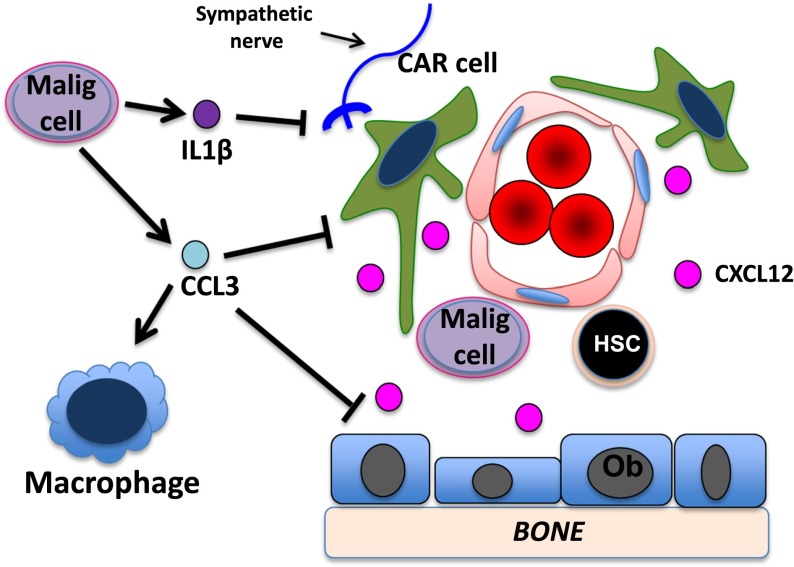

There also is evidence that malignant HSPCs in MPNs can alter the bone marrow microenvironment to selectively enhance their own support over normal HSCs. In a murine model of JAK2 V617F+ MPN, Arranz et al showed that mutant HSCs, through expression of IL1β, inhibited β3-adrenergic production from sympathetic nerves in the bone marrow, resulting in depletion of nestin-GFP+ stromal cells and accelerated MPN progression (Figure 3).102 Conversely, treatment with β3-adrenergic agonists inhibited MPN progression. Likewise, Schepers et al showed, using an inducible model of BCR-ABL+ MPNs, that development of MPN was associated with an expansion of endosteal osteoblastic lineage cells that preferentially supported leukemic stem cells over normal HSCs.103 This may be mediated, in part, by decreased bone marrow stromal expression of CXCL12, which results in reduced homing and retention of normal HSCs in the bone marrow.103,104 Interestingly, the effect of stromal alterations on MPN progression may be disease specific. Whereas increased osteoblastic PTH signaling inhibits BCR-ABL–induced MPN, it augments acute myeloid leukemia (AML) induced by the MLL-AF9 oncogene.105

Figure 3.

Malignant cells alter the HSC niche. Malignant (Malig) cells secrete factors including CCL3 and IL1β that, directly or through monocytic cells (here shown as macrophages) or sympathetic nerves, respectively, target multiple stromal cell populations implicated in the HSC niche, including CAR cells and osteoblasts (Ob). This results in decreased stromal cell CXCL12 expression and potentially other changes, which in turn, increase niche support of malignant cells over normal HSCs.

Myelodysplastic syndromes

Much data from both murine models and primary human samples suggest a role for bone marrow stromal cell populations in the pathogenesis of MDS106-108 (also reviewed in Balderman and Calvi109 and Bulycheva et al110). Mesenchymal stromal cells isolated from a variety of human MDS subtypes have been shown to have reduced proliferative capacity, increased senescence, impaired ability to undergo osteogenic differentiation, alterations in specific DNA methylation patterns, and diminished ability to support HSCs in long-term culture.111 For MDS, gene targeting of specific cell types within the bone marrow microenvironment has, however, provided evidence that alterations of the HSC niche constituents are capable of inducing secondary changes and malignant hematopoietic disease. Processing of microRNAs by the RNase III endonuclease Dicer1 is critical for their function, and Dicer1 disruption has been associated with tumorigenesis.112 When Dicer1 from osteolineage cells was selectively deleted in stromal cells by Sp7 (osterix) promoter-driven Cre expression, a severe MDS-like syndrome was initiated with the capability of transformation to leukemia.113 In spite of these convincing genetic data, our understanding of how the supportive mechanisms by which the niche regulates HSCs either fail or become subverted in myelodysplasia remain still poorly defined, in part because our definition of HSC niche components is evolving, and in part because malignant cells may modify their microenvironment. For example, recent data demonstrate that mesenchymal cell populations from MDS patients are essential for engraftment of MDS stem cells in xenografts, suggesting that reciprocal interactions between the microenvironment and MDS contribute to disease progression.114 Taken together, these data nonetheless highlight a role of the microenvironment, and specifically skeletal cell populations in the initiation of marrow failure syndrome, and suggest the potential for niche stimulation as a treatment strategy in MDS, a disease process with limited therapeutic options to date.115

Leukemia

Although the role of mature osteoblasts in normal HSC regulation is controversial, emerging data in genetic murine models suggest their contribution to leukemogenesis, and in leukemic transformation from MPNs. A recent study by Kode et al demonstrated that expression of a constitutively active β-catenin allele in osteoblasts induces myeloid leukemia with cytogenetics changes.116 In this genetic model, inhibition of Notch signaling, either through osteoblast deletion of the Notch ligand, Jagged 1, or through pharmacologic inhibition of γ-secretase, prevented the development of AML. A follow-up study showed that the β-catenin–induced increase in Jagged 1 expression in osteoblasts is dependent on Fox01.117 These observations were extended to human AML/MDS bone marrow samples, in which >30% of cases exhibited nuclear localization of β-catenin in osteoblasts and increased Notch receptor signaling.116 Osteopontin expression by osteoblasts may also contribute to leukemic progression. Similar to normal HSCs,118 osteopontin may regulate leukemic stem cell quiescence. Specifically, in a human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) xenograft model, neutralization of osteopontin was associated with increased ALL cell cycling and sensitivity to chemotherapy.119

Endothelial cells also have been implicated in leukemic progression. Using an activated Notch model of T-ALL, Pitt et al showed that, following transplantation, T-ALL cells preferentially localize to perivascular regions in the bone marrow.120 The development of lethal T-ALL in this model is dependent on CXCR4 signaling. Interestingly, deletion of Cxcl12 from endothelial cells, but not leptin receptor+ perivascular stromal cells, markedly attenuated T-ALL propagation in this model. Thus, these data suggest that CXCL12 expression from endothelial cells is uniquely required for efficient T-ALL proliferation and/or survival. Likewise, Cao et al suggest that the efficient propagation of malignant B cells from Eμ-Myc mice is dependent on endothelial cells.121 Specifically, they describe a paracrine loop that is initiated by FGF1 expression from the malignant B cells that activates the FGF receptor-1 on endothelial cells. This in turn induces endothelial Jagged1 expression, which stimulates malignant B cells.

Leukemic cell infiltration may alter the bone marrow microenvironment. Colmone et al showed, using a xenograft model of pre-B-ALL, that the presence of leukemic cells in the bone marrow results in impaired homing and mobilization of CD34+ cells from healthy donors that was dependent, in part, on increased stromal expression of SCF.122 Similar to JAK2 V617F MPN, infiltration of the bone marrow with AML induces alterations in the sympathetic nervous system that lead to a decrease in nestin-GFP+ stromal cells, while promoting osteoblast expansion.123 Conversely, we showed that increased expression of C-C motif ligand 3 (CCL3) by leukemic cells suppresses osteoblastic cells (Figure 3).124 Thus, leukemic cells may have diverse effects on osteoblastic cells and the bone marrow microenvironment in general. Recently, Duan et al showed that injection of a human ALL cell line into immunodeficient mice following irradiation induced a transient niche that is composed of mesenchymal stromal cells that surround clusters of ALL cells.125 Similar structures were observed in the bone marrow of patients with ALL following chemotherapy. Moreover, interference with the formation or function of this transient niche increased the sensitivity of the ALL cells to chemotherapy, suggesting that this specialized niche may contribute to ALL chemoresistance in vivo.

Metastatic cancer

Interactions of cancer cells with stromal cells in the HSC niche may also contribute to the development of metastatic bone disease. Shiozawa et al showed, using a prostate cancer xenograft model, that prostate cells directly compete with normal HSCs for niche support.77 Moreover, they showed that increasing “HSC niche space,” either by mobilizing HSCs with a CXCR4 antagonist or by expanding osteolineage cells with PTH, resulted in an increase in prostate cancer bone metastasis. Using a breast cancer xenograft model, Sethi et al showed that Jagged1 expression by osteolytic bone metastases activates osteoblasts, leading to tumor growth in the bone marrow.126 Of note, treatment with γ-secretase inhibitors in this model inhibited the development of breast cancer metastases.

Summary and future directions

There is compelling evidence that signals from the bone marrow microenvironment play a key role in the regulation of normal and malignant hematopoiesis. The ability of stromal cells in the bone marrow microenvironment to support hematopoiesis is dynamic and responsive to environmental cues such as inflammation and stress. Ongoing research to identify the signals that regulate bone marrow stromal cells may provide novel strategies to modulate hematopoiesis for therapeutic benefit. For example, a phase 1 trial of PTH to expand the stem cell niche and HSPCs prior to G-CSF treatment resulted in an acceptable level of HSPC mobilization in nearly 50% of patients who previously had a mobilization failure.86

Alterations in bone marrow stromal cells may contribute to the development of hematopoietic malignancies. Proof-of-principle experiments using transgenic mice carrying genetic alterations in bone marrow stromal cells establish that abnormal stromal cell function can lead to MPN-like disease in mice. For certain rare syndromes such as Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, genetic alterations in stromal cells likely contribute to impaired hematopoiesis. However, it is not clear whether somatic mutations in stromal cells contribute to hematopoietic malignancy. Rather, current evidence suggests that malignant hematopoietic cells produce factor(s) that alter stromal cell function, such as FGF4.121 Identification of these putative factors may provide novel targets for therapeutic intervention. For example, there is an ongoing clinical trial of a β3-adrenergic agonist to restore the damaged niche in patients with MPN (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02311569). An emerging theme is that malignant cells in the bone marrow alter nearby stromal cell expression of key niche factors, such as CXCL12 and Jagged1, which, in turn, promote malignant hematopoietic cell growth. Interestingly, these same factors also support normal HSCs. The mechanisms by which altered niche factor expression selectively supports malignant hematopoietic cell expansion need to be elucidated. Indeed, the likely coexistence of both malignant and benign niches in the bone marrow represents an opportunity for therapeutic manipulation to improve normal hematopoiesis while targeting malignant clones, and therefore should continue to be the focus of intense investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Calvi and Link laboratories for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney Diseases (grant DK081843), National Cancer Institute (grant CA166280), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant AI107376), National Institute on Aging (grant AGO46293) (L.M.C.), and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (grant HL60772) (D.C.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.M.C. and D.C.L. wrote this perspective.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Laura M. Calvi, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Box 693, Rochester, NY 14642; e-mail: laura_calvi@urmc.rochester.edu; and Daniel C. Link, Division of Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, Campus Box 8007, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: dlink@dom.wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Enver T, Pera M, Peterson C, Andrews PW. Stem cell states, fates, and the rules of attraction. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(5):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4(1-2):7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kai T, Spradling A. An empty Drosophila stem cell niche reactivates the proliferation of ectopic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(8):4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, Fuller MT. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science. 2001;294(5551):2542–2545. doi: 10.1126/science.1066707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407(6805):750–754. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116(6):769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Losick VP, Morris LX, Fox DT, Spradling A. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Greco V. Spatial organization within a niche as a determinant of stem-cell fate. Nature. 2013;502(7472):513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425(6960):836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nombela-Arrieta C, Pivarnik G, Winkel B, et al. Quantitative imaging of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell localization and hypoxic status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):533–543. doi: 10.1038/ncb2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sipkins DA, Wei X, Wu JW, et al. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature. 2005;435(7044):969–973. doi: 10.1038/nature03703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer JA, Ferraro F, Roussakis E, et al. Direct measurement of local oxygen concentration in the bone marrow of live animals. Nature. 2014;508(7495):269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Coverdale JA. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 2001;97(8):2293–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson A, Murphy MJ, Oskarsson T, et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18(22):2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Y, Yin T, Wiegraebe W, et al. Detection of functional haematopoietic stem cell niche using real-time imaging. Nature. 2009;457(7225):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruns I, Lucas D, Pinho S, et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1315–1320. doi: 10.1038/nm.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acar M, Kocherlakota KS, Murphy MM, et al. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature. 2015;526(7571):126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature15250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Méndez-Ferrer S, Scadden DT, Sánchez-Aguilera A. Bone marrow stem cells: current and emerging concepts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1335 doi: 10.1111/nyas.12641. 32-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunisaki Y, Bruns I, Scheiermann C, et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;502(7473):637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481(7382):457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. 2013;495(7440):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenbaum A, Hsu YM, Day RB, et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature. 2013;495(7440):227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkler IG, Barbier V, Nowlan B, et al. Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1651–1657. doi: 10.1038/nm.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hooper AT, Butler JM, Nolan DJ, et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avecilla ST, Hattori K, Heissig B, et al. Chemokine-mediated interaction of hematopoietic progenitors with the bone marrow vascular niche is required for thrombopoiesis. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):64–71. doi: 10.1038/nm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131(2):324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao WM, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124(2):407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452(7186):442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamazaki S, Ema H, Karlsson G, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147(5):1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamazaki S, Iwama A, Takayanagi S, Eto K, Ema H, Nakauchi H. TGF-beta as a candidate bone marrow niche signal to induce hematopoietic stem cell hibernation. Blood. 2009;113(6):1250–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-146480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao M, Perry JM, Marshall H, et al. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1321–1326. doi: 10.1038/nm.3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heazlewood SY, Neaves RJ, Williams B, Haylock DN, Adams TE, Nilsson SK. Megakaryocytes co-localise with hemopoietic stem cells and release cytokines that up-regulate stem cell proliferation. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2013;11(2):782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson TS, Caselli A, Otsuru S, et al. Megakaryocytes promote murine osteoblastic HSC niche expansion and stem cell engraftment after radioablative conditioning. Blood. 2013;121(26):5238–5249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-463414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33(3):387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokoyoda K, Egawa T, Sugiyama T, Choi BI, Nagasawa T. Cellular niches controlling B lymphocyte behavior within bone marrow during development. Immunity. 2004;20(6):707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Morrison SJ. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(2):154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deguchi K, Yagi H, Inada M, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Excessive extramedullary hematopoiesis in Cbfa1-deficient mice with a congenital lack of bone marrow. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255(2):352–359. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taichman RS, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support hematopoiesis through the production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179(5):1677–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian H, Buza-Vidas N, Hyland CD, et al. Critical role of thrombopoietin in maintaining adult quiescent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):671–684. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshihara H, Arai F, Hosokawa K, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung Y, Wang J, Schneider A, et al. Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts; a possible mechanism for stem cell homing. Bone. 2006;38(4):497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Visnjic D, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Katavic V, Lorenzo J, Aguila HL. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004;103(9):3258–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lymperi S, Horwood N, Marley S, Gordon MY, Cope AP, Dazzi F. Strontium can increase some osteoblasts without increasing hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2008;111(3):1173–1181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma YD, Park C, Zhao H, et al. Defects in osteoblast function but no changes in long-term repopulating potential of hematopoietic stem cells in a mouse chronic inflammatory arthritis model. Blood. 2009;114(20):4402–4410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura Y, Arai F, Iwasaki H, et al. Isolation and characterization of endosteal niche cell populations that regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116(9):1422–1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu J, Garrett R, Jung Y, et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;109(9):3706–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu JY, Purton LE, Rodda SJ, et al. Osteoblastic regulation of B lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gsalpha-dependent signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(44):16976–16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu VW, Saez B, Cook C, et al. Specific bone cells produce DLL4 to generate thymus-seeding progenitors from bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2015;212(5):759–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asada N, Katayama Y, Sato M, et al. Matrix-embedded osteocytes regulate mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(6):737–747. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fulzele K, Krause DS, Panaroni C, et al. Myelopoiesis is regulated by osteocytes through Gsα-dependent signaling. Blood. 2013;121(6):930–939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas J, Liu F, Link DC. Mechanisms of mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Curr Opin Hematol. 2002;9(3):183–189. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christopher MJ, Link DC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces osteoblast apoptosis and inhibits osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(11):1765–1774. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106(9):3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Day RB, Bhattacharya D, Nagasawa T, Link DC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor reprograms bone marrow stromal cells to actively suppress B lymphopoiesis in mice. Blood. 2015;125(20):3114–3117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, Long F, Link DC. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu F, Poursine-Laurent J, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor on hematopoietic progenitor cells is not required for their mobilization by G-CSF. Blood. 2000;95(10):3025–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Christopher MJ, Rao M, Liu F, Woloszynek JR, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):251–260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang MK, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, et al. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181(2):1232–1244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winkler IG, Sims NA, Pettit AR, et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood. 2010;116(23):4815–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chow A, Lucas D, Hidalgo A, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):261–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lucas D, Battista M, Shi PA, Isola L, Frenette PS. Mobilized hematopoietic stem cell yield depends on species-specific circadian timing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(4):364–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heidt T, Sager HB, Courties G, et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20(7):754–758. doi: 10.1038/nm.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Casanova-Acebes M, Pitaval C, Weiss LA, et al. Rhythmic modulation of the hematopoietic niche through neutrophil clearance. Cell. 2013;153(5):1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, et al. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24(6):801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andonegui G, Zhou H, Bullard D, et al. Mice that exclusively express TLR4 on endothelial cells can efficiently clear a lethal systemic Gram-negative bacterial infection. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):1921–1930. doi: 10.1172/JCI36411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boettcher S, Gerosa RC, Radpour R, et al. Endothelial cells translate pathogen signals into G-CSF-driven emergency granulopoiesis. Blood. 2014;124(9):1393–1403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-570762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burberry A, Zeng MY, Ding L, et al. Infection mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells through cooperative NOD-like receptor and Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(6):779–791. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rutkowski MR, Stephen TL, Svoronos N, et al. Microbially driven TLR5-dependent signaling governs distal malignant progression through tumor-promoting inflammation. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takizawa H, Boettcher S, Manz MG. Demand-adapted regulation of early hematopoiesis in infection and inflammation. Blood. 2012;119(13):2991–3002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-380113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Itkin T, Kaufmann KB, Gur-Cohen S, Ludin A, Lapidot T. Fibroblast growth factor signaling promotes physiological bone remodeling and stem cell self-renewal. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20(3):237–244. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283606162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shiozawa Y, Pedersen EA, Havens AM, et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1298–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI43414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adams GB, Martin RP, Alley IR, et al. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche [published corrections appear in Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(8):944 and Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(2):241]. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(2):238-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bromberg O, Frisch BJ, Weber JM, Porter RL, Civitelli R, Calvi LM. Osteoblastic N-cadherin is not required for microenvironmental support and regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2012;120(2):303–313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Calvi LM, Bromberg O, Rhee Y, et al. Osteoblastic expansion induced by parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in murine osteocytes is not sufficient to increase hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012;119(11):2489–2499. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cho SW, Soki FN, Koh AJ, et al. Osteal macrophages support physiologic skeletal remodeling and anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone in bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(4):1545–1550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315153111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terauchi M, Li JY, Bedi B, et al. T lymphocytes amplify the anabolic activity of parathyroid hormone through Wnt10b signaling. Cell Metab. 2009;10(3):229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li JY, Adams J, Calvi LM, et al. PTH expands short-term murine hemopoietic stem cells through T cells. Blood. 2012;120(22):4352–4362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu EW, Kumbhani R, Siwila-Sackman E, et al. Teriparatide (PTH 1-34) treatment increases peripheral hematopoietic stem cells in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(6):1380–1386. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brunner S, Theiss HD, Murr A, Negele T, Franz WM. Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with increased circulating bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(6):E1670–E1675. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00287.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ballen KK, Shpall EJ, Avigan D, et al. Phase I trial of parathyroid hormone to facilitate stem cell mobilization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(7):838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thurmond TS, Murante FG, Staples JE, Silverstone AE, Korach KS, Gasiewicz TA. Role of estrogen receptor alpha in hematopoietic stem cell development and B lymphocyte maturation in the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2000;141(7):2309–2318. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zoller AL, Kersh GJ. Estrogen induces thymic atrophy by eliminating early thymic progenitors and inhibiting proliferation of beta-selected thymocytes. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7371–7378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakada D, Oguro H, Levi BP, et al. Oestrogen increases haematopoietic stem-cell self-renewal in females and during pregnancy. Nature. 2014;505(7484):555–558. doi: 10.1038/nature12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li JY, Adams J, Calvi LM, Lane TF, Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. Ovariectomy expands murine short-term hemopoietic stem cell function through T cell expressed CD40L and Wnt10B. Blood. 2013;122(14):2346–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-487801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.North TE, Goessling W, Walkley CR, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature. 2007;447(7147):1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature05883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hoggatt J, Singh P, Sampath J, Pelus LM. Prostaglandin E2 enhances hematopoietic stem cell homing, survival, and proliferation. Blood. 2009;113(22):5444–5455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ikushima YM, Arai F, Hosokawa K, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) regulates murine hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells directly via EP4 receptor and indirectly through mesenchymal progenitor cells. Blood. 2013;121(11):1995–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Porter RL, Georger MA, Bromberg O, et al. Prostaglandin E2 increases hematopoietic stem cell survival and accelerates hematopoietic recovery after radiation injury. Stem Cells. 2013;31(2):372–383. doi: 10.1002/stem.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ludin A, Itkin T, Gur-Cohen S, et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express α-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(11):1072–1082. doi: 10.1038/ni.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoggatt J, Mohammad KS, Singh P, et al. Differential stem- and progenitor-cell trafficking by prostaglandin E2. Nature. 2013;495(7441):365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature11929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Goessling W, Allen RS, Guan X, et al. Prostaglandin E2 enhances human cord blood stem cell xenotransplants and shows long-term safety in preclinical nonhuman primate transplant models. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(4):445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walkley CR, Olsen GH, Dworkin S, et al. A microenvironment-induced myeloproliferative syndrome caused by retinoic acid receptor gamma deficiency. Cell. 2007;129(6):1097–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang L, Zhang H, Rodriguez S, et al. Notch-dependent repression of miR-155 in the bone marrow niche regulates hematopoiesis in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walkley CR, Shea JM, Sims NA, Purton LE, Orkin SH. Rb regulates interactions between hematopoietic stem cells and their bone marrow microenvironment. Cell. 2007;129(6):1081–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim YW, Koo BK, Jeong HW, et al. Defective Notch activation in microenvironment leads to myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2008;112(12):4628–4638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arranz L, Sánchez-Aguilera A, Martín-Pérez D, et al. Neuropathy of haematopoietic stem cell niche is essential for myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature. 2014;512(7512):78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature13383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schepers K, Pietras EM, Reynaud D, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasia remodels the endosteal bone marrow niche into a self-reinforcing leukemic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(3):285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang B, Ho YW, Huang Q, et al. Altered microenvironmental regulation of leukemic and normal stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(4):577–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krause DS, Fulzele K, Catic A, et al. Differential regulation of myeloid leukemias by the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1513–1517. doi: 10.1038/nm.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dror Y, Freedman MH. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: An inherited preleukemic bone marrow failure disorder with aberrant hematopoietic progenitors and faulty marrow microenvironment. Blood. 1999;94(9):3048–3054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li Y, Chen S, Yuan J, et al. Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells promote the reconstitution of exogenous hematopoietic stem cells in Fancg-/- mice in vivo. Blood. 2009;113(10):2342–2351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kerbauy DB, Deeg HJ. Apoptosis and antiapoptotic mechanisms in the progression of myelodysplastic syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2007;35(11):1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Balderman SR, Calvi LM. Biology of BM failure syndromes: role of microenvironment and niches. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:71–76. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bulycheva E, Rauner M, Medyouf H, et al. Myelodysplasia is in the niche: novel concepts and emerging therapies. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):259–268. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Geyh S, Oz S, Cadeddu RP, et al. Insufficient stromal support in MDS results from molecular and functional deficits of mesenchymal stromal cells. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1841–1851. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Raaijmakers MH, Mukherjee S, Guo S, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464(7290):852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Medyouf H, Mossner M, Jann JC, et al. Myelodysplastic cells in patients reprogram mesenchymal stromal cells to establish a transplantable stem cell niche disease unit. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(6):824–837. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bejar R, Steensma DP. Recent developments in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2014;124(18):2793–2803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-522136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kode A, Manavalan JS, Mosialou I, et al. Leukaemogenesis induced by an activating β-catenin mutation in osteoblasts. Nature. 2014;506(7487):240–244. doi: 10.1038/nature12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kode A, Mosialou I, Manavalan SJ, et al. FoxO1-dependent induction of acute myeloid leukemia by osteoblasts in mice [published online ahead of print June 25, 2015]. Leukemia. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.161. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Stier S, Ko Y, Forkert R, et al. Osteopontin is a hematopoietic stem cell niche component that negatively regulates stem cell pool size. J Exp Med. 2005;201(11):1781–1791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Boyerinas B, Zafrir M, Yesilkanal AE, Price TT, Hyjek EM, Sipkins DA. Adhesion to osteopontin in the bone marrow niche regulates lymphoblastic leukemia cell dormancy. Blood. 2013;121(24):4821–4831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pitt LA, Tikhonova AN, Hu H, et al. CXCL12-Producing Vascular Endothelial Niches Control Acute T Cell Leukemia Maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(6):755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cao Z, Ding BS, Guo P, et al. Angiocrine factors deployed by tumor vascular niche induce B cell lymphoma invasiveness and chemoresistance. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):350–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322(5909):1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hanoun M, Zhang D, Mizoguchi T, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia-induced sympathetic neuropathy promotes malignancy in an altered hematopoietic stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(3):365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Frisch BJ, Ashton JM, Xing L, Becker MW, Jordan CT, Calvi LM. Functional inhibition of osteoblastic cells in an in vivo mouse model of myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(2):540–550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Duan CW, Shi J, Chen J, et al. Leukemia propagating cells rebuild an evolving niche in response to therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):778–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sethi N, Dai X, Winter CG, Kang Y. Tumor-derived JAGGED1 promotes osteolytic bone metastasis of breast cancer by engaging notch signaling in bone cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]