Key Points

MLL3 acts as tumor suppressor in FLT3-ITD AML.

The existence of DNMT3A mutations in remission samples implies that the DNMT3A mutant clone can survive induction chemotherapy.

Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with an FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) mutation is an aggressive hematologic malignancy with a grave prognosis. To identify the mutational spectrum associated with relapse, whole-exome sequencing was performed on 13 matched diagnosis, relapse, and remission trios followed by targeted sequencing of 299 genes in 67 FLT3-ITD patients. The FLT3-ITD genome has an average of 13 mutations per sample, similar to other AML subtypes, which is a low mutation rate compared with that in solid tumors. Recurrent mutations occur in genes related to DNA methylation, chromatin, histone methylation, myeloid transcription factors, signaling, adhesion, cohesin complex, and the spliceosome. Their pattern of mutual exclusivity and cooperation among mutated genes suggests that these genes have a strong biological relationship. In addition, we identified mutations in previously unappreciated genes such as MLL3, NSD1, FAT1, FAT4, and IDH3B. Mutations in 9 genes were observed in the relapse-specific phase. DNMT3A mutations are the most stable mutations, and this DNMT3A-transformed clone can be present even in morphologic complete remissions. Of note, all AML matched trio samples shared at least 1 genomic alteration at diagnosis and relapse, suggesting common ancestral clones. Two types of clonal evolution occur at relapse: either the founder clone recurs or a subclone of the founder clone escapes from induction chemotherapy and expands at relapse by acquiring new mutations. Relapse-specific mutations displayed an increase in transversions. Functional assays demonstrated that both MLL3 and FAT1 exert tumor-suppressor activity in the FLT3-ITD subtype. An inhibitor of XPO1 synergized with standard AML induction chemotherapy to inhibit FLT3-ITD growth. This study clearly shows that FLT3-ITD AML requires additional driver genetic alterations in addition to FLT3-ITD alone.

Introduction

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is a clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells caused by acquired and occasionally inherited genetic alterations.1 Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a tyrosine kinase receptor involved in proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. Constitutive activation of FLT3 by internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation is one of the most common molecular alterations in AML, occurring in approximately 20% to 30% of AML patients who have a comparatively poor clinical outcome and increased relapse rate.1-3 This oncogenic mutation inappropriately activates the cell surface tyrosine kinase receptor to signal downstream pathways via mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/AKT pathways. FLT3-ITD also potently activates STAT5 pathway-stimulating transcription of target genes (eg, cyclin-D1, c-Myc, and antiapoptotic genes p21 and Bcl-XL).4-7 Thus, FLT3-ITD enhances cellular proliferation and reduces apoptosis of hematopoietic blasts.

Although 70% of FLT3-ITD AML patients achieve a complete remission (CR) with conventional chemotherapy, the majority of patients eventually relapse and die of therapy-resistant leukemia.8 Recently, several small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting FLT3 have been investigated in phase 1/2 clinical trials.9-12 FLT3 inhibitors are efficient for a limited period of time in treating AML patients because these compounds are well tolerated at doses that achieve inhibition of FLT3.13,14 Heterozygous FLT3WT/ITD knockin mice developed a myeloproliferative neoplasm. However, these mice did not develop acute leukemia, suggesting that additional drivers are required for leukemogenesis.15,16 The additional mutations that cause AML include AML1-ETO fusion gene,17 CBFβ-SMMHC gene fusion,18 NUP98 translocations,19 NPM1,20 and loss of Tet2.21 Recently, many studies have reported exome sequencing of AML, but these studies have a limited number of FLT3-ITD subtypes and almost none have matched diagnosis and relapse samples.22-27 Therefore, a need exists to identify genomic abnormalities underlying the FLT3-ITD subtype at diagnosis (DX) and at relapse (REL) for a greater understanding of this disease and to guide the development of effective targeted therapies.

Methods

Patients and samples

Genomic DNAs (gDNAs) from 80 AML patient samples with the FLT3-ITD subgroup were collected at 3 different time points (DX, CR, and REL) by collaborating with several institutes. The German cohort consisted of 56 patients (38 with DX, CR, and REL samples and 18 with DX and CR samples) provided by Charite University School of Medicine, Berlin and Munich Leukemia Laboratory, Munich, Germany. The Japanese samples (3 patients with DX, CR, and REL samples) were provided by Nippon Medical School, Tokyo, Japan. The Taiwanese cohort consisted of 12 patients (7 with DX, CR, and REL samples and 5 with CR and REL samples) provided by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. The Singaporean cohort consisted of 9 patients (2 with DX, CR, and REL samples and 7 with DX and CR samples) provided by the National University Health System, Singapore. All samples were collected between September 1997 and August 2012. These samples were used for either whole-exome sequencing (WES) or targeted deep sequencing (TDS). Written independent consent was obtained from all patients for research studies using their samples. Clinical characteristics of these patients included age and sex, the distribution of French-American-British subtype, cytogenetics, bone marrow white blood cell counts, hemoglobin, platelets, survival, and FLT3-ITD status (supplemental Tables 1 and 6 available on the Blood Web site). Patients were treated with standard chemotherapy, including induction chemotherapy (100 mg/m2 cytosine arabinoside on days 1 to 7 via continuous intravenous dosing and 60 mg/m2 daunorubicin or idarubicin on days 4 to 6). Patients who achieved CR were usually given consolidation chemotherapy that involved either the same or similar drugs. FLT3-ITD AML patients with primary refractory disease were not included in this study. gDNA was extracted by using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit and a QIAamp DNA Investigator kit (QIAGEN). The Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Life Technologies) was used to quantify the concentration of gDNA. The intactness of each gDNA sample was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis using 0.7% agarose gel.

Exome capture, massively parallel sequencing, and analysis of WES data

gDNAs from DX, CR, and REL samples were used for WES as described previously28-30 (details are provided in the supplemental Data).

Clustering and clonal analysis, mutational signature, frequency analysis using TDS, significantly mutated gene analysis, pathway analysis, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analysis,31,32 cell culture, antibodies, RNA interference, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis and quantitative real-time PCR,33 gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting,33 and xenograft models33 are described in the supplemental Data.

Short-term cell proliferation assay

MOLM14 and MV4-11cells were transfected twice with scramble mixed-lineage leukemia 3 (MLL3) or FAT1 small interfering RNA (siRNA). The second transfection was performed after an additional 48 hours. After the second transfection, 8,000 cells were seeded in 96-well plates, and cell proliferation was measured by using 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated with 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (0.5 mg/mL) and incubated for 3 hours in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. Formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of stop solution (sodium dodecyl sulfate HCl). Absorbance was measured at 570 nm by using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO spectrophotometer (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland).

Colony-forming assay

For clonogenic assay, MV4-11 cells were harvested and counted after their second transfection with siRNA against MLL3, FAT1, or scramble MLL3, and 500 cells per condition were plated in Methocult H4230 medium (STEMCELL Technologies) and cultured for 7 to 10 days at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Colonies consisting of more than 50 cells were counted in both the control and experimental wells.

Statistical analysis

The false discovery rate q values for mutated genes were calculated by using the Mutational Significance in Cancer (MuSiC; http://gmt.genome.wustl.edu/packages/genome-music/) suite of tools with default parameters. The statistical analyses were conducted by using the two-tailed Student t test upon verification of the assumptions (eg, normality); otherwise, the nonparametric test was applied for short-term cell proliferation, quantitative PCR, colony formation, and xenografts.

Results

Identifying somatic mutations by using WES and TDS

Initially, WES was performed on 13 trios consisting of samples at DX and REL along with their CR (germ line control) as the discovery cohort. The average coverage of each base in the targeted region was 120-fold, with 78% of bases covered at least 20X (supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and supplemental Figure 1). SNP array (copy number analysis) was performed on 11 of these 13 trio samples. To eliminate contamination of the leukemic cells in CR, we included only those samples whose bone marrow blast counts in CR were <5% (supplemental Table 1).

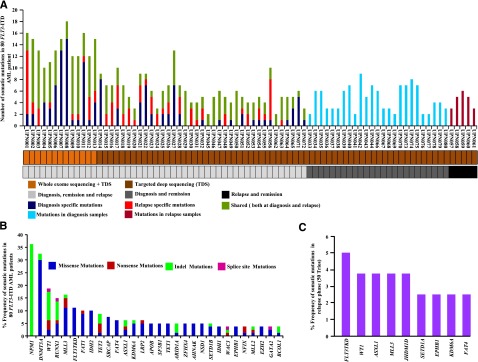

In total, 179 nonsilent somatic mutations of the WES of the discovery cohort were confirmed by Sanger sequencing, including 131 missense, 8 nonsense, 5 splice site mutations, 22 indels, and 13 in-frame insertion mutations (true positive rate, 92.1%; supplemental Tables 3 and 4 and supplemental Figure 2A-B). The average number of validated somatic mutations per sample was 13.6 (Figure 1A and supplemental Table 3), a mutation rate comparable to that in most hematologic malignancies23-27,30,34 but significantly lower than that present in solid tumors.35-40 A total of 75 shared mutations occurred at both DX and REL. Moreover, 64 mutations were DX specific, and 26 mutations were REL specific (supplemental Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Somatic mutations identified by WES and TDS of FLT3-ITD AML. (A) Number of mutations discovered for 50 individuals at DX, CR, and REL (light gray), 25 individuals at DX and CR (dark gray), and 5 individuals at CR and REL (black). Samples subjected to WES plus TDS or TDS only are color coded in light or dark brown, respectively. Dark blue, red, and dark green represent the number of somatic mutations at DX, REL, and both DX and REL, respectively. Light blue and magenta show the number of mutations observed in DX and REL samples, respectively. (B) Overall frequency of mutated genes in 80 FLT3-ITD AML patients. NPM1 gene mutations are missense frameshift mutations (green). (C) Frequency of specific somatic mutations detected only at REL in 50 trios (DX, CR, and REL paired).

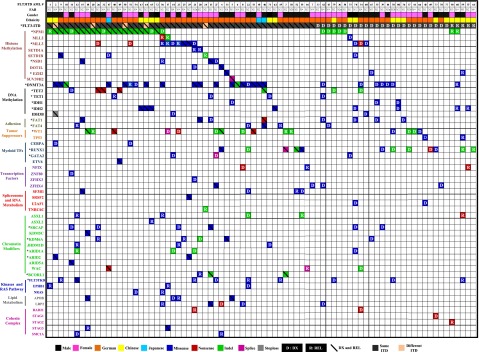

TDS of 151 genes (ascertained from the discovery cohort plus an additional 148 genes related to hematologic malignancies [The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA], http://cancergenome.nih.gov/; Cancer Gene Census, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/census/] supplemental Table 5) was performed on 67 additional FLT3-ITD patient samples (supplemental Table 6), as well as 2 FLT3-ITD-positive AML cell lines (frequency cohort). We also included 13 patients from the discovery cohort to ensure capture efficiency. Samples in the frequency cohort had a mean average coverage of the targeted regions of 107-fold, with 77% of the bases covered at least 30X (supplemental Table 7 and supplemental Figure 3). In total, 284 nonsilent somatic mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing with an average of 4.23 mutations per sample (true positive rate, 91.03%; Figure 1A and supplemental Tables 8 and 9). A total of 42 genes were mutated in more than 2 samples (supplemental Table 8), with 21 genes mutated at a frequency of more than 4% (Figure 1B). Recurrent mutations in 9 genes were also identified in the REL-specific phase (Figure 1C). WES and TDS found a high frequency of mutations of the NPM1 gene (36%), as well as genes related to DNA methylation (63%), chromatin modification (42%), histone methylation (38%), myeloid transcription factors (22%), tumor suppressors (20%), signaling (16%), adhesion (14%), lipid metabolism (11%), cohesin complex (10%), and spliceosomes (10%) (Figure 2). Hotspot mutations also occurred in several genes: DNMT3A (R882H and R882C), NPM1 (W288fs), FLT3-TKD (D835Y, D839G, Y597F, L601F, and N676), SF3B1 (K666N and K700E), U2AF1 (S34F and S34Y), IDH1 (R132H and R132C), and IDH2 (R140Q) (supplemental Figures 4A-C and 5A-D).

Figure 2.

Distribution of somatic mutations in 80 patients with FLT3-ITD AML. Each column displays French-American-British classification, sex, and ethnicity of an individual sample; each row denotes a specific gene. Recurrently mutated genes are color coded for missense (blue), nonsense (red), indel (green), splice site (purple), and stoploss (gray). The letters D and R or diagonal lines denote somatic mutation at DX, REL, and both DX and REL, respectively. Asterisks mark genes mutated at a significant (false discovery rate <0.05) recurrence rate. Mutated genes are clustered according to their pathways or family.

Heterozygous DNMT3A mutations were confirmed in 19 of 50 trios. The same DNMT3A mutation occurred at both DX and REL in 16 (85%) of 19 trios samples, whereas in 2 patients, DNMT3A mutations were lost at REL, and 1 patient with wild-type DNMT3A at DX gained a DNMT3A mutation at REL (supplemental Figure 6). Of note, DNMT3A mutations were detected at a variant allele frequency of <5% to 40% in 8 of 19 CR samples (supplemental Figure 7 and supplemental Table 10). This suggests that use of CR samples as a germline control limits the power to detect the mutations that exist in early clones that persist during CR. NPM1 mutations were lost in 3 of 22 patients at REL, whereas 19 of 22 patients had the same NPM1 mutation at both DX and REL (supplemental Figures 6 and 8).

The ITD mutations of the FLT3 locus were detected by using Pindel41 and Genomon ITDetector,42 which has high sensitivity to detect ITDs using soft clipped reads. All ITDs were detected in exon 14 of the FLT3 gene. In a majority of the cases (45 of 50 trios), ITDs occurred at the same position and with the same insertion sequence at both the DX and REL stages of the disease. However, 5 patients showed different ITD insertion at REL (supplemental Figure 6). On the basis of calculated variant allele frequency, FLT3-ITD was present in subclones at both DX and REL in 92% of the cases (46 of 50). However, FLT3-ITD was also observed as a part of the founder clone at DX and REL in 4% of the cases (2 of 50) (supplemental Table 11).

The MuSiC suite of tools was used to identify significantly mutated genes or selected candidate driver genes.43,44 Twenty genes with a higher-than-expected mutational prevalence were identified, including the well-known drivers relevant to AML pathogenesis (eg, DNMT3A, NPM1, WT1, FLT3, RUNX1, GATA2, TET2, EZH2, IDH1, and IDH2), along with novel genes that have only recently been implicated in AML pathogenesis, including MLL3, KDM6A, FAT1, NSD1, ARID2, SRCAP, and FAT4 (Figure 2 and supplemental Table 12). By using the MuSiC PathScan algorithm, 6 pathways were significantly enriched in the mutated gene list45,46 (supplemental Table 13). Moreover, co-occurrence was observed between mutations in DNMT3A and NPM1, DNMT3A and FAT1 (P < .032), IDH2 and NPM1 (P < .032), MLL3 and SRCAP (P < .05), EZH2 and KDM6 (P < .001), and FAT1 and NSD1 (P < .04). Mutual exclusivity was identified between NPM1 and RUNX1 (P < .036), NPM1 and MLL3 (P < .001), WT1 and MLL3 (P < .04), and MLL3 and RUNX1 (supplemental Figure 9A). Mutual exclusivity especially occurred in mutations of genes belonging to different biological categories, such spliceosomes, cohesin complex (supplemental Figure 9B), chromatin modifiers, and histone-modifying proteins (supplemental Figure 10A-B), suggesting that 1 mutation in these pathways is generally adequate for AML pathogenesis.

One of our goals in this study was to identify genomic therapeutic targets in FLT3-ITD AML. Ten genes with potentially druggable alterations were noted in 52 (65%) of 80 FLT3-ITD patients (supplemental Figure 11).

Mutational classes and mutational signature in FLT3-ITD AML

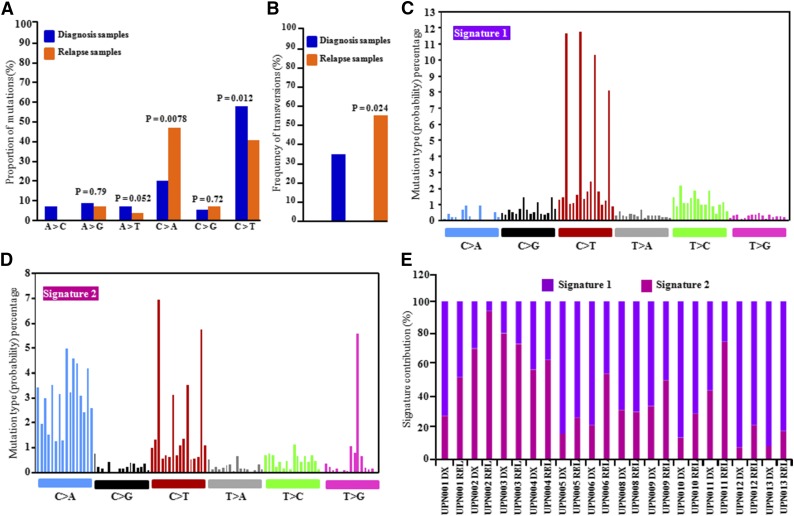

Discovery cohort patients were treated with cytarabine and daunorubicin (anthracycline) for induction therapy (supplemental Table 1). To examine the possible effects of chemotherapeutic agents on the mutational spectrum of REL samples, 6 classes of transition and transversion mutations were compared at DX vs REL.23 The C>T transitions were the most common mutations at DX and REL in the AML genomes, but their frequencies were different (P = .012) between DX-specific mutations (56%) and REL-specific mutations (38%). The average increase in C>A (26%; P = .0078) and C>G transversions occurred in REL-specific mutations (Figure 3A). In addition, overall frequency of transversions was higher in REL-specific AML samples (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Distribution of mutational nucleotide classes between DX and REL paired samples. (A) Proportion of nucleotide transition and transversion mutations at DX and REL of 14 patients studied by WES. (B) Overall frequency of transversions at DX and REL (13 patients). Z test (proportion test) was used for statistical significance. (C-D) Mutational signature using a 96 substitution classification based on substitution classes and the sequence context immediately to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the mutated base. Mutation types are represented using different colors. Horizontal axes display type of mutations; vertical axes represent percentage of mutations in a specific mutation type. (E) Percentage contribution of the two mutational processes identified by EMu analysis.

Each mutational process usually induces a unique combination of nucleotide changes that provide a signature. Mutational signature analysis using EMu software (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/emu/) showed that signatures 1 and 2 were enriched in the discovery cohort47-49 (Figure 3C-D). Signature 1 was enriched with C>T transition at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, an intrinsic mutational process reflecting deamination of 5-methylcytosine. Signature 2 showed predominance of C>T (transition) and C>A and C>G (transversion) in a thymine-phosphate-cytosine (TpC) context with enrichment in many REL samples (Figure 3E), which may be induced by chemotherapy in these REL samples.

Clonal evolution in FLT3-ITD AML

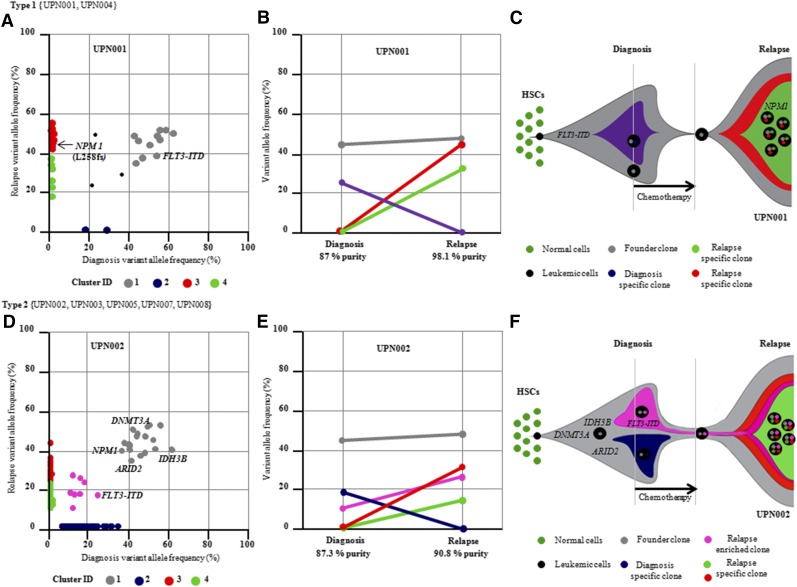

Several forms of clonal evolution occurred. The first is characterized by patient UPN001 (Figure 4A-C). Mutational clustering at DX and REL (UPN001) identified 4 clones with well-defined sets of mutations.23 Median mutant variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of clones (1 and 2) at DX were 44.4% and 23.53%, respectively. Clone 1 is the founder clone because all of these mutations are heterozygous with VAFs of ∼40% to 50%, and they are present in virtually all the leukemic cells at DX and REL (Figure 4A). Cluster 2 represents mutations present only in the DX clone. Clusters 3 and 4 were detected in the REL samples, suggesting that the founder clone gained additional (REL-specific) mutations, and these mutations perhaps provided resistance to chemotherapy (Figure 4A-C). Loss of DX-specific clone at REL suggested that DX-specific clones were indeed eradicated by chemotherapy (Figure 4C). In this case, NPM1 mutation in REL-specific clones seems to be a driver mutation, because NPM1 is recurrently mutated in AML. Mutational clustering of an additional 10 DX-REL pairs revealed 2 different types of clonal evolution at REL. In type 1 (UPN001 and UPN004), the dominant clone at DX accumulated more mutations and evolved as an REL-specific clone. In type 2 (UPN002, UPN003, UPN005, UPN007, and UPN008), a subclone bearing DX-specific mutations escaped from therapy, acquired additional mutations, and expanded at REL (Figure 4D-E). Additional mutations in the subclones may provide resistance to chemotherapy and be an important force for REL (Figure 4F). In UPN005 and UPN009, DNMT3A mutations were confirmed in CR samples with VAFs of 20% and 40%, respectively. This suggests that in these patients, the DNMT3A clone may persist in morphologic CRs and expand during CR resulting in REL in these patients. Our survival data also show that these patients have very short REL-free survival and overall survival.

Figure 4.

Clonal evolution from primary to REL in UPN001 and UPN002 and pattern of evolution observed in 13 DX and REL pairs. (A,D) Distribution of variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of validated mutations at DX and REL (UPN001 and UPN002). VAFs of genes in region of uniparental disomy are halved. Driver mutations, including FLT3-ITD, are indicated. Two mutational clusters were identified at DX and 2 were present at REL; 1 was present at both DX and REL. (B,E) Graphic representation of the relationship between clusters at DX and REL. Gray cluster represents founding clone at DX and REL. (C,F) Schematic representation of mutational clones and their evolution from DX to REL. Founder clone at DX evolved into REL clones by acquiring REL-specific mutations. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell.

MLL3 acts as a tumor suppressor gene in FLT3-ITD AML

MLL3 belongs to the TRX/MLL gene family mapping to chromosome 7q36.1,50,51 is reported to be mutated in several types of tumors52-54 (COSMIC, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/), and is also deleted in myeloid leukemias.55 Within the TCGA cohort, only 1 of 200 AML patients had a nonsense mutation (E2793X) (Figure 5A), and 24 (12%) of 200 AML patients had deletions in the MLL3 gene24 (supplemental Figure 13A). Interestingly, we observed somatic mutations of MLL3 in 15% (12 of 80) of FLT3-ITD samples, including 1 frameshift and 3 stop-gain mutations (Figure 5A). Our SNP chip data also showed that 3 of 11 samples had deletion of MLL3 (supplemental Figure 12). Interestingly, 2 of the 20 patients with FLT3-ITD in the TCGA cohort also had an MLL3 deletion24 (supplemental Figure 13A).

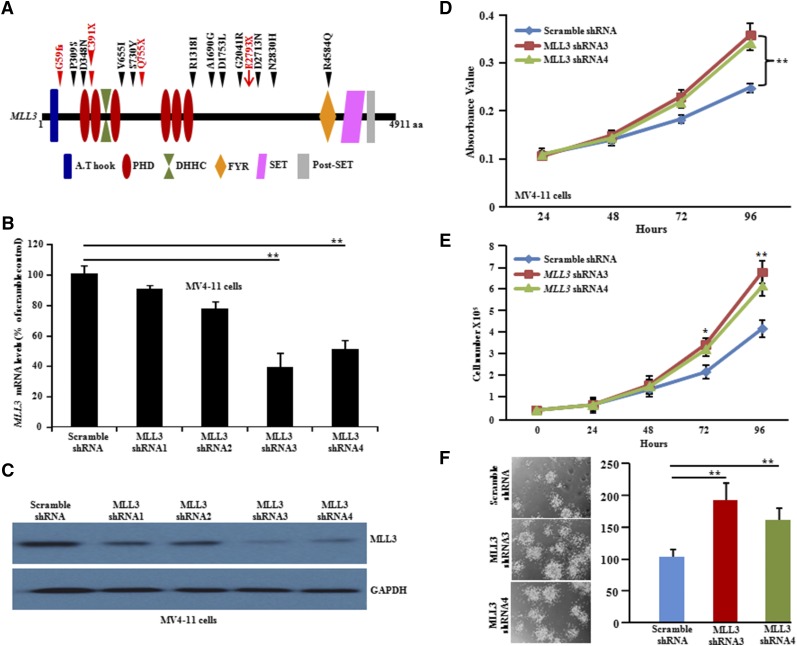

Figure 5.

MLL3 gene is mutated in FLT3-ITD AML both at DX and REL, and silencing of MLL3 in FLT3-ITD cells increased their growth in both liquid culture and clonogenic assay. (A) Schematic of the MLL3 domains and locations of the amino acid substitutions caused by somatic mutations detected by WES and TDS. Black or red triangles indicate missense mutations or nonsense mutations (either frameshift [fs] or stop-gain [X], respectively). Red arrow represents nonsense mutation identified in AML TCGA data. Structural motifs of gene: A.T hook (ATPase α/β signature), PHD (plant homeodomain), DHHC (palmitoyltransferase activity), FYR (phenylalanine tyrosine-rich domain), SET (suppressor of variegation, enhancer of zeste, trithorax). (B) Real-time PCR analysis showed reduced MLL3 mRNA in MLL3 shRNA-treated cells compared with scramble shRNA-treated cells. MLL3 shRNA3 and MLL3 shRNA4 showed approximately 50% to 60% knockdown in MV4-11 cells compared with scramble shRNA. (C) Western blot shows reduced MLL3 protein levels in MLL3 shRNA transduced cells (MV4-11) compared with scramble shRNA-treated cells. GAPDH is used as an internal control. (D) Short-term cell proliferation assays of MV4-11 cells transduced with either MLL3 shRNAs or scramble shRNA. Data represent means ± standard deviation (SD); n = 4. (E) For cell counting assay, 0.5 × 105 cells were plated in 6-well plates in quadruplets. Cell proliferation was measured by counting cells over a 5-day period. Results are shown as means ± SD; n = 4. (F) Methylcellulose colony assay showed a significant increase in the number of MV4-11 colonies after cells were transfected with MLL3 shRNA compared with scramble shRNA-treated cells. Data represent means ± SD; n = 3. *P ≤ .01; **P ≤ .001.

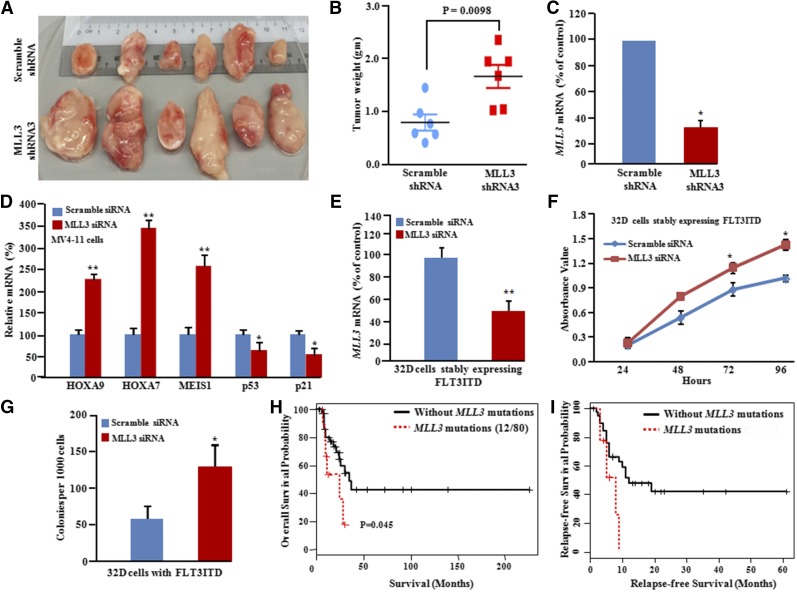

To study biological consequences of MLL3 inactivation in the FLT3-ITD subgroup of AML, MV4-11 cells (FLT3-ITD AML) were transduced with either MLL3 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or scramble shRNA. MLL3 silencing resulted in significantly increased cell growth in liquid culture and clonogenic growth in methylcellulose (Figure 5B-F). Xenograft growth was also significantly greater (size and weight of tumors) compared with scrambled knockdown cells (Figure 6A-C). To confirm on-target effects of shRNA knockdown, MLL3 expression was also silenced with siRNA, and similar results were observed (supplemental Figure 13B-D). MLL3 depletion in MV4-11 cells resulted in decreased p21 and p53 messenger RNA expression compared with control cells and a significant upregulation of HOXA7 (3.5-fold), HOXA9 (2.0-fold), and MEIS1 (2.5-fold) (Figure 6D). The latter suggests that HOX genes might be targets of MLL3 in FLT3-ITD AML.56 Moreover, depletion of wild-type MLL3 with murine MLL3 siRNA in murine 32D myeloid cells stably expressing murine FLT3-ITD increased cell growth in liquid culture and clonogenic growth in soft-gel culture (Figure 6E-G) compared with scramble siRNA-treated cells. In addition, FLT3-ITD patients with MLL3 mutations had a worse prognosis compared with FLT3-ITD patients without MLL3 mutations, as reflected by overall survival and REL-free survival (Figure 6H-I). Together, these results strongly suggest that MLL3 acts as a tumor suppressor gene that is frequently lost in FLT3-ITD-mutant cells.

Figure 6.

MLL3 acts as a recessive gene mutated in FLT3-ITD subgroup. (A) Xenografts (4 weeks) were established using MV4-11 cells stably expressing either scramble or MLL3 shRNA. Scale is in centimeters. (B) Weight of individual tumors in each group (mean ± SD; P = .0098). (C) Relative mRNA expression of MLL3 (quantitative PCR) in xenografts. Values represent mean ± SD; n = 3. *P < .05. (D) Quantitative PCR showed relative increase in mRNA levels of HOXA7, HOXA9, and MEIS, and relative decrease in the mRNA levels of p21 and p53 (growth-inhibitory genes). Data represent mean ± SD; n = 3. *P < .05; **P ≤ .01. (E,F) Knockdown of murine MLL3 in 32D cells stably expressing murine FLT3-ITD caused increased cell growth in liquid culture. Data represent mean ± SD; n = 3. *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01. (G) Methylcellulose colony formation assay of 32D cells (stably expressing murine FLT3-ITD) transfected with either scramble siRNA or siRNA MLL3. Data represent mean ± SD; n = 3. *P ≤ .05. (H) Survival curves of AML patients either with or without MLL3 mutations. (I) Relapse-free survival curves of AML patients either with or without MLL3 mutations.

FAT mutations and XPO1 inhibition in FLT3-ITD AML

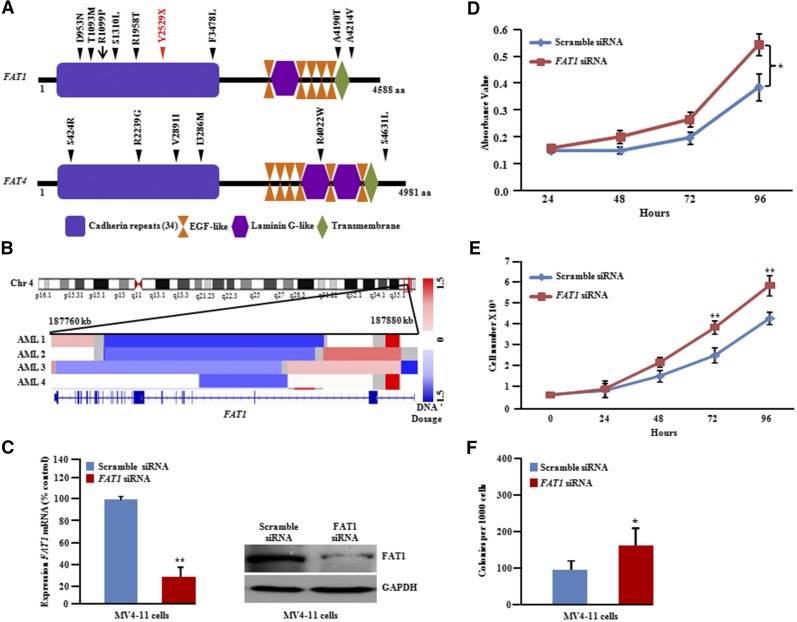

The FAT1 gene is located on human chromosome 4q35.2, a prevalent region of deletion in human cancer.57-59 We identified and verified an unexpectedly high rate (10%) of FAT1 mutations in FLT3-ITD samples (8 of 80) (Figure 7A). TCGA data analysis showed focal deletion on chromosome 4q35.2 containing FAT1 in 2% of AML samples (4 of 200) (Figure 7B) and a single patient with a missense mutation (R1099P) (Figure 7A). Our SNP chip data also showed that 1 of 11 patients had a deletion of FAT1 at REL (supplemental Figure 14). To study the biological role of FAT1 inactivation in FLT3-ITD, the expression of the FAT1 gene was silenced in MV4-11 cells by using siRNA against FAT1 (Figure 7C). A significant increase in cellular proliferation in liquid culture and soft-gel culture was observed in these FAT1-depleted cells (Figure 7D-E).

Figure 7.

FAT1 and FAT4 somatic mutations in FLT3-ITD AML at DX and REL. (A) Schematic of FAT1 and FAT4 genes with the locations of alterations. Black or red triangles show either missense or stop-gain, respectively. Red arrow represents missense mutation present in AML TCGA data set. Conserved domains are displayed by using UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/). (B) IGV (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv) heat map of 4q35.2 shows deletional peak with FAT1 deletion culled from 200 AML patients (TCGA consortium; http://cancergenome.nih.gov). (C) Real-time and protein blot display knockdown of FAT1 in MV4-11 cells. Quantitative PCR data represent means ± SD; n = 3. **P ≤ .01. (D) Cell growth showed increased proliferation with FAT1 knockdown in MV4-11 cells (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide assay; quadruplicate experiments). Data represent means ± SD. *P ≤ .05. (E) Cell counting assay: 0.5 × 105 cells were plated in 6-well plates in quadruplets, and cell proliferation was measured by counting cells over a 5-day period. Results are shown as means ± SD; n = 4. (F) Methylcellulose colony assay of MV4-11 cells transfected with either scramble control or FAT1 siRNA. Data represent means ± SD; n = 3. *P ≤ .05.

TCGA data analysis showed that 3% of AML samples (6 of 200) had focal deletion of FAT4 (supplemental Figure 15A). FAT4 was moderately frequently mutated (5%; 4 of 80) in our FLT3-ITD samples, occurring in a mutually exclusive manner to samples with FAT1 mutations (supplemental Figure 15B).

Recent studies showed that XPO1 levels were higher in AML patients with FLT3 mutations.60-62 Elevated levels of XPO1 in our RNA sequencing data were confirmed by real-time data at REL compared with DX (supplemental Figure 16A). An XPO1 inhibitor (KPT330) combined with standard AML induction chemotherapy is in clinical trials. We found that KPT330 combined with standard AML chemotherapy synergistically inhibited proliferation of FLT3-ITD AML cells (supplemental Figure 16B-D).

Discussion

AML occurs because of a series of mutations and results in aberrant proliferation and impaired differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.63 Next-generation sequencing has allowed a high-throughput, comprehensive characterization of cancer genomes that can aid in making clinical decisions. In the last few years, genes from adult AML patients have been extensively sequenced.16-20 A few reports included a limited number of DX and REL samples.23,64,65 However, none included DX and REL matched samples of FLT3-ITD AML. In this study, we sequenced a very large FLT3-ITD cohort that included DX and REL paired samples (supplemental Tables 1 and 6) to discover the mutations associated with FLT3-ITD. We discovered that the average number of coding mutations (single nucleotide variants and indels) was 13.6 mutations per sample, which is comparable to AML in general (∼10 mutations per sample)23-27,30,34 and clearly lower than that in solid tumors. All the mutations were validated by Sanger sequencing. Recurrent mutations in 10 genes were also identified in the REL-specific phase but not at DX in 50 trio (DX, CR, and REL) samples. This may be the result of small subclones having VAFs of less than 5% at DX. Our sequencing depth (120X) limits the power to detect subclones with VAFs of less than 5%. The previous reported high rate of mutations of FLT3, NPM1, DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and WT1 genes highlights the power of WES/whole-genome sequencing.23-27,66 However, the frequency of these mutations varied remarkably between the genomes of normal karyotype French-American-British M1 AML and M3 AML (PML-RARA fusion),67 suggesting that AML is heterogeneous and supports the further characterization of different AML subtypes. In our study, mutations were found in previously identified driver genes (NPM1, DNMT3A, WT1, FLT3, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, RUNX1, ASXL1, and FAT4) as well as either novel or previously unappreciated genes, including MLL3, FAT1, SRCAP, NSD1, KDM6A, LRP2, and APOB (supplemental Table 16). Several genes such as DNMT3A, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, SF3B1, U2AF1, and FLT3 (supplemental Figures 4 and 5) showed hotspot mutations, mostly in line with earlier studies.

Comparative mutation analysis of primary and relapsed paired samples showed high stability of mutations in DNMT3A, NPM1, IDH2, RUNX1, and TET2, whereas less stability was observed in IDH1 and FLT3-ITD (supplemental Figure 6). This was congruent with previously published studies.68-74

The overall mutational spectrum of 80 FLT3-ITD patients showed a high prevalence of C>T transitions, but an increase in C>A and C>G transversion occurred in REL compared with DX samples, suggesting that chemotherapy has a potential effect on the mutational spectrum at REL. Few copy-number changes were identified in REL of these patients on the SNP chip, indicating that the increased rate of transversion was not associated with genomic instability. C>A transversions were frequent events in patients with AML and lung cancer (in patients exposed to tobacco-borne carcinogens).23,75

The most represented signatures in our cohort were signature 1 and signature 2. Signature 1 is associated with the age of the patients and is dominant in various malignancies, including myeloid, breast, kidney, and prostate cancer and glioblastoma.47,49 Signature 2 was enriched in the REL samples, suggesting that this signature may be caused by induction chemotherapy, but larger patient cohorts will be required to confirm this observation.

Clonal expansion is a hallmark of cancers. Clonal evolution is greatly influenced by chemotherapeutic agents because these agents are continuously selecting resistance clones, the main basis for reoccurrence of disease.76 Our study extends the previous findings, which recently described the pattern of clonal evolution in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia and AML by using fluorescence in situ hybridization, copy-number alterations (SNP arrays), and next-generation sequencing.23,77-80 We found that either the dominant clone at DX gained additional mutations and expanded as an REL-specific clone or a subclone at DX escaped chemotherapy and became the major clone at REL. Taken together, these data suggest that relapsed AML cells usually gain additional mutations during chemotherapy, possibly contributing to drug resistance. In this context, 5 patients displayed different ITD insertion sequences in the FLT3 gene between DX and REL, suggesting that this is a possible mechanism of clonal evolution. In our data, DNMT3Amut was found at a high VAF at DX and REL, indicating that DNMT3Amut is part of the founder clone, and its perseverance in CR revealed that the clone bearing DNMT3Amut may survive chemotherapy and expand during CR. These findings suggest that DNMT3Amut is one of the most durable and early mutations during leukemogenesis.64,67,81-83 To achieve long-term disease-free survival, future therapies need to eradicate all the preleukemic clones present at DX that persist during treatment and contribute to REL.

Strikingly, mutations of different genes in the histone methyltransferase complex were mutually exclusive, suggesting that they have an important role in pathogenesis of this disease. We observed recurrent mutations as well as deletions in MLL3 in our FLT3-ITD cohort. MLL3 is one of the most frequently mutated and deleted genes in human cancers including AML,84,85 but the biological significance of these alterations is unknown. In our in vitro studies, selective inhibition of human and murine MLL3 using siRNA in human MV4-11 cells (FLT3-ITD) and murine cells (32D cells stably expressing murine FLT3-ITD) accelerated their proliferation in liquid culture and colony formation in methylcellulose gel. Moreover, stable knockdown of MLL3 in MV4-11 cells promoted tumor growth in a xenograft model. This suggests that MLL3 acts as a tumor suppressor whereas loss in FLT3-ITD AML contributes to the aggressive nature of the disease. More work is clearly needed to test whether heterozygous FLT3WT/ITD knockin mice develop leukemia when crossed with MLL3 heterozygous knockout mice. Recent studies also suggest that MLL3 suppression alone is not sufficient to drive leukemogenesis but instead cooperates with p53 loss to block the differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, leading to a myelodysplastic syndrome-like disease.86 Another study showed that somatic cancer mutations of MLL3 resulted in loss of its enzymatic activity (H3K4 methylation), which affects the epigenetic landscape.87

FAT1 inhibition increased proliferation of MV4-11 cells in both liquid and soft-gel culture. Mutual exclusivity between FAT1 and FAT4 suggests that either one of these genes enhances the progression of leukemia. More research is required to test the biological role and molecular mechanism of the FAT family in AML progression.

In summary, we reported the mutational landscape of the 80 FLT3-ITD cases and identified a number of novel driver genes. We also highlighted a deregulated drug target that offers potential avenues for treatment of AML, an aggressive leukemia. These data together provide an enhanced road map for studying the molecular basis underlying this deadly malignancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof H. Serve and Dr J. Mueller for gifts of 32D cells stably expressing murine wild-type FLT3 and FLT3-ITD, Ori Kalid and Sharon Shacham for providing KPT330 (XPO1 inhibitor), and Dr P. Tan for generously sharing related facilities.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute grant R01CA026038-35 (H.P.K.), National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence initiative (H.P.K.), the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its Singapore Translational Research Investigator Award (H.P.K.), NSC91-2314-B-182-032 (Taiwan), NHRI-EX96-9434SI (Taiwan), the Eleanor and Glenn Padnick Discovery Fund in Cellular Therapy, and a generous donation from the Melamed family.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.G. and H.P.K. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; M.G., D.K., Y.N., K.Y., Z.J.Z., S.H.K., L.-W.D., Q.-Y.S., D.-C.L. W.C., V.M., A.S., and S.V. performed the experiments; Y.N., A.M., K.Y., Y.O., Y.S., K.C., H.T., S.M., L.-Z.L., K.-T.T., M.S., and H.Y. performed bioinformatic analysis; T.A., K.I., S.W., H.Y., W.J.C., S.-K.Y.K., A.E.-J.Y., J.S., K.-A.K., S.M.K., H.M.K., T.H., M.L., M.-C.K., L.-Y.S., I.-W.B., and O.B. coordinated sample collection and processing; and M.G., Y.N., D.K., S.O., and H.P.K. analyzed and discussed the data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.H. is employed by and partly owns the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory. T.A. is employed by the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Manoj Garg, Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Centre for Translational Medicine, 14 Medical Drive MD-6, Singapore 117599; e-mail: csimg@nus.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368(9550):1894–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fröhling S, Scholl C, Levine RL, et al. Identification of driver and passenger mutations of FLT3 by high-throughput DNA sequence analysis and functional assessment of candidate alleles. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(6):501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirewalt DL, Radich JP. The role of FLT3 in haematopoietic malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(9):650–665. doi: 10.1038/nrc1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi S. Downstream molecular pathways of FLT3 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia: biology and therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levis M, Small D. FLT3: ITDoes matter in leukemia. Leukemia. 2003;17(9):1738–1752. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkenkamp KU, Geugien M, Lemmink HH, Kruijer W, Vellenga E. Regulation of constitutive STAT5 phosphorylation in acute myeloid leukemia blasts. Leukemia. 2001;15(12):1923–1931. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parcells BW, Ikeda AK, Simms-Waldrip T, Moore TB, Sakamoto KM. FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 in normal hematopoiesis and acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1174–1184. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estey EH. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2014 update on risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(11):1063–1081. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisberg E, Barrett R, Liu Q, Stone R, Gray N, Griffin JD. FLT3 inhibition and mechanisms of drug resistance in mutant FLT3-positive AML. Drug Resist Updat. 2009;12(3):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tickenbrock L, Müller-Tidow C, Berdel WE, Serve H. Emerging Flt3 kinase inhibitors in the treatment of leukaemia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11(1):153–165. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravandi F, Alattar ML, Grunwald MR, et al. Phase 2 study of azacytidine plus sorafenib in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT-3 internal tandem duplication mutation. Blood. 2013;121(23):4655–4662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kindler T, Breitenbuecher F, Kasper S, et al. Identification of a novel activating mutation (Y842C) within the activation loop of FLT3 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood. 2005;105(1):335–340. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knapper S. FLT3 inhibition in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;138(6):687–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz M, Burnett A, Lo-Coco F, Löwenberg B. FLT3 inhibition as a targeted therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21(6):594–600. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833118fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu SH, Heiser D, Li L, et al. FLT3-ITD knockin impairs hematopoietic stem cell quiescence/homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(3):346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Bailey E, Greenblatt S, Huso D, Small D. Loss of the wild-type allele contributes to myeloid expansion and disease aggressiveness in FLT3/ITD knockin mice. Blood. 2011;118(18):4935–4945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schessl C, Rawat VP, Cusan M, et al. The AML1-ETO fusion gene and the FLT3 length mutation collaborate in inducing acute leukemia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2159–2168. doi: 10.1172/JCI24225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HG, Kojima K, Swindle CS, et al. FLT3-ITD cooperates with inv(16) to promote progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(3):1567–1574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenblatt S, Li L, Slape C, et al. Knock-in of a FLT3/ITD mutation cooperates with a NUP98-HOXD13 fusion to generate acute myeloid leukemia in a mouse model. Blood. 2012;119(12):2883–2894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-382283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mupo A, Celani L, Dovey O, et al. A powerful molecular synergy between mutant Nucleophosmin and Flt3-ITD drives acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1917–1920. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih AH, Jiang Y, Meydan C, et al. Mutational cooperativity linked to combinatorial epigenetic gain of function in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):502–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jan M, Snyder TM, Corces-Zimmerman MR, et al. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(149):149ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481(7382):506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(4):309–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456(7218):66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kon A, Shih LY, Minamino M, et al. Recurrent mutations in multiple components of the cohesin complex in myeloid neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1232–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg M, Okamoto R, Nagata Y, et al. Establishment and characterization of novel human primary and metastatic anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines and their genomic evolution over a year as a primagraft. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):725–735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478(7367):64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nannya Y, Sanada M, Nakazaki K, et al. A robust algorithm for copy number detection using high-density oligonucleotide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping arrays. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6071–6079. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida K, Toki T, Okuno Y, et al. The landscape of somatic mutations in Down syndrome-related myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1293–1299. doi: 10.1038/ng.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garg M, Kanojia D, Okamoto R, et al. Laminin-5γ-2 (LAMC2) is highly expressed in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma and is associated with tumor progression, migration, and invasion by modulating signaling of EGFR. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):E62–E72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475(7354):101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govindan R, Ding L, Griffith M, et al. Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell. 2012;150(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee W, Jiang Z, Liu J, et al. The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature. 2010;465(7297):473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature09004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah SP, Morin RD, Khattra J, et al. Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2009;461(7265):809–813. doi: 10.1038/nature08489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469(7331):539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin DC, Hao JJ, Nagata Y, et al. Genomic and molecular characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):467–473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):860–867. doi: 10.1038/ng.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(21):2865–2871. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiba K, Shiraishi Y, Nagata Y, et al. Genomon ITDetector: a tool for somatic internal tandem duplication detection from cancer genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(1):116–118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dees ND, Zhang Q, Kandoth C, et al. MuSiC: identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Res. 2012;22(8):1589–1598. doi: 10.1101/gr.134635.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wendl MC, Wallis JW, Lin L, et al. PathScan: a tool for discerning mutational significance in groups of putative cancer genes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(12):1595–1602. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.India Project Team of the International Cancer Genome Consortium. Mutational landscape of gingivo-buccal oral squamous cell carcinoma reveals new recurrently-mutated genes and molecular subgroups. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2873. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fischer A, Illingworth CJ, Campbell PJ, Mustonen V. EMu: probabilistic inference of mutational processes and their localization in the cancer genome. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell Reports. 2013;3(1):246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shilatifard A. The COMPASS family of histone H3K4 methylases: mechanisms of regulation in development and disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051710-134100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgan MA, Shilatifard A. Drosophila SETs its sights on cancer: Trr/MLL3/4 COMPASS-like complexes in development and disease. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(9):1698–1701. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00203-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ellis MJ, Ding L, Shen D, et al. Whole-genome analysis informs breast cancer response to aromatase inhibition. Nature. 2012;486(7403):353–360. doi: 10.1038/nature11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, et al. Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491(7424):399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zang ZJ, Cutcutache I, Poon SL, et al. Exome sequencing of gastric adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent somatic mutations in cell adhesion and chromatin remodeling genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):570–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruault M, Brun ME, Ventura M, Roizès G, De Sario A. MLL3, a new human member of the TRX/MLL gene family, maps to 7q36, a chromosome region frequently deleted in myeloid leukaemia. Gene. 2002;284(1-2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alharbi RA, Pettengell R, Pandha HS, Morgan R. The role of HOX genes in normal hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1000–1008. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris LG, Kaufman AM, Gong Y, et al. Recurrent somatic mutation of FAT1 in multiple human cancers leads to aberrant Wnt activation. Nat Genet. 2013;45(3):253–261. doi: 10.1038/ng.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG, et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(10):1097–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saburi S, Hester I, Goodrich L, McNeill H. Functional interactions between Fat family cadherins in tissue morphogenesis and planar polarity. Development. 2012;139(10):1806–1820. doi: 10.1242/dev.077461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kojima K, Kornblau SM, Ruvolo V, et al. Prognostic impact and targeting of CRM1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(20):4166–4174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-447581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ranganathan P, Yu X, Na C, et al. Preclinical activity of a novel CRM1 inhibitor in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(9):1765–1773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Etchin J, Sanda T, Mansour MR, et al. KPT-330 inhibitor of CRM1 (XPO1)-mediated nuclear export has selective anti-leukaemic activity in preclinical models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(1):117–127. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Löwenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(14):1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(7):2548–2553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324297111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wakita S, Yamaguchi H, Omori I, et al. Mutations of the epigenetics-modifying gene (DNMT3a, TET2, IDH1/2) at diagnosis may induce FLT3-ITD at relapse in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1044–1052. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150(2):264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krönke J, Bullinger L, Teleanu V, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(1):100–108. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schnittger S, Kern W, Tschulik C, et al. Minimal residual disease levels assessed by NPM1 mutation-specific RQ-PCR provide important prognostic information in AML. Blood. 2009;114(11):2220–2231. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hou HA, Kuo YY, Liu CY, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: stability during disease evolution and clinical implications. Blood. 2012;119(2):559–568. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shih LY, Huang CF, Wu JH, et al. Internal tandem duplication of FLT3 in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: a comparative analysis of bone marrow samples from 108 adult patients at diagnosis and relapse. Blood. 2002;100(7):2387–2392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chou WC, Hou HA, Chen CY, et al. Distinct clinical and biologic characteristics in adult acute myeloid leukemia bearing the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation. Blood. 2010;115(14):2749–2754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schnittger S, Haferlach C, Ulke M, Alpermann T, Kern W, Haferlach T. IDH1 mutations are detected in 6.6% of 1414 AML patients and are associated with intermediate risk karyotype and unfavorable prognosis in adults younger than 60 years and unmutated NPM1 status. Blood. 2010;116(25):5486–5496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-267955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krönke J, Schlenk RF, Jensen KO, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the German-Austrian acute myeloid leukemia study group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2709–2716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mullighan CG, Phillips LA, Su X, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322(5906):1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anderson K, Lutz C, van Delft FW, et al. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature. 2011;469(7330):356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature09650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Notta F, Mullighan CG, Wang JC, et al. Evolution of human BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2011;469(7330):362–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller CA, White BS, Dees ND, et al. SciClone: inferring clonal architecture and tracking the spatial and temporal patterns of tumor evolution. PLOS Comput Biol. 2014;10(8):e1003665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, et al. HALT Pan-Leukemia Gene Panel Consortium. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506(7488):328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pløen GG, Nederby L, Guldberg P, et al. Persistence of DNMT3A mutations at long-term remission in adult patients with AML. Br J Haematol. 2014;167(4):478–486. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klco JM, Spencer DH, Miller CA, et al. Functional heterogeneity of genetically defined subclones in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dolnik A, Engelmann JC, Scharfenberger-Schmeer M, et al. Commonly altered genomic regions in acute myeloid leukemia are enriched for somatic mutations involved in chromatin remodeling and splicing. Blood. 2012;120(18):e83–e92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-401471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li WD, Li QR, Xu SN, et al. Exome sequencing identifies an MLL3 gene germ line mutation in a pedigree of colorectal cancer and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(8):1478–1479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-470559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen C, Liu Y, Rappaport AR, et al. MLL3 is a haploinsufficient 7q tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(5):652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weirich S, Kudithipudi S, Kycia I, Jeltsch A. Somatic cancer mutations in the MLL3-SET domain alter the catalytic properties of the enzyme. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]