Background: The relevance of ASXL2 to the function of the histone H2A deubiquitinase BAP1 remains unknown.

Results: ASXL2 promotes the assembly by BAP1 of a composite ubiquitin-binding interface (CUBI) required for DUB activity and coordination of cell proliferation.

Conclusion: Cancer-associated mutations of BAP1 disrupt BAP1-ASXL2 interaction and function.

Significance: We provide novel insights into BAP1 tumor suppressor function.

Keywords: cancer biology, cell proliferation, cellular senescence, deubiquitylation (deubiquitination), epigenetics, ASXL, BAP1, Calypso, histone H2A ubiquitination, Polycomb Group Proteins

Abstract

The deubiquitinase (DUB) and tumor suppressor BAP1 catalyzes ubiquitin removal from histone H2A Lys-119 and coordinates cell proliferation, but how BAP1 partners modulate its function remains poorly understood. Here, we report that BAP1 forms two mutually exclusive complexes with the transcriptional regulators ASXL1 and ASXL2, which are necessary for maintaining proper protein levels of this DUB. Conversely, BAP1 is essential for maintaining ASXL2, but not ASXL1, protein stability. Notably, cancer-associated loss of BAP1 expression results in ASXL2 destabilization and hence loss of its function. ASXL1 and ASXL2 use their ASXM domains to interact with the C-terminal domain (CTD) of BAP1, and these interactions are required for ubiquitin binding and H2A deubiquitination. The deubiquitination-promoting effect of ASXM requires intramolecular interactions between catalytic and non-catalytic domains of BAP1, which generate a composite ubiquitin-binding interface (CUBI). Notably, the CUBI engages multiple interactions with ubiquitin involving (i) the ubiquitin carboxyl hydrolase catalytic domain of BAP1, which interacts with the hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin, and (ii) the CTD domain, which interacts with a charged patch of ubiquitin. Significantly, we identified cancer-associated mutations of BAP1 that disrupt the CUBI and notably an in-frame deletion in the CTD that inhibits its interaction with ASXL1/2 and DUB activity and deregulates cell proliferation. Moreover, we demonstrated that BAP1 interaction with ASXL2 regulates cell senescence and that ASXL2 cancer-associated mutations disrupt BAP1 DUB activity. Thus, inactivation of the BAP1/ASXL2 axis might contribute to cancer development.

Introduction

Covalent attachment of ubiquitin on lysine or N-terminal residues of target proteins can influence substrate stability and function and as such exerts major roles in diverse cellular processes, including intracellular trafficking, protein quality control, cell cycle progression, transcription, DNA replication, and repair (1–5). Ubiquitination is catalyzed by the concerted action of E1 ubiquitin-activating, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating, and E3 ubiquitin ligases and generally results in the attachment of one or several ubiquitin molecules, i.e. mono- or polyubiquitination, respectively (3, 6). Ubiquitination events are tightly coordinated by DUBs,7 which are responsible for reversing this modification (7, 8).

Proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) are responsible for the specific and non-covalent recognition of free ubiquitin and of mono- or polyubiquitinated substrates. UBDs can be categorized into several families based on structural characteristics such as the presence of single or multiple α-helices, zinc fingers, or the pleckstrin homology fold, which constitute interfaces of low affinity interaction with one or multiple molecules of ubiquitin. UBD-containing proteins are thus widely involved in the proper and timely initiation, propagation, or termination of ubiquitin-mediated signaling events (3, 9).

The nuclear DUB BAP1 is a tumor suppressor deleted and mutated in an increasing number of cancers of diverse origins (10, 11). Indeed, somatic or germinal inactivating mutations in BAP1 are found in mesothelioma, uveal melanoma, cutaneous melanocytic tumors, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and breast and lung cancers, thereby making BAP1 the most frequently and widely mutated DUB-encoding gene in cancer (12–20). Previous studies indicated that BAP1 tumor suppressor function requires DUB activity and nuclear localization (21). Consistent with its role in tumor suppression, BAP1 was shown to act as a positive or a negative regulator of cell proliferation (21–24). Moreover, genetic ablation of BAP1 in mice inhibits embryonic development, whereas selective inactivation of BAP1 in the hematopoietic system induces severe defects in the myeloid cell lineage, recapitulating key features of myelodysplastic syndrome (19). At the molecular level, BAP1 acts as a chromatin-associated protein that is assembled into large multiprotein complexes containing several transcription factors and co-factors, including the following: host cell factor 1 (HCF-1); the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT); the lysine-specific demethylase KDM1B/LSD2/AOF1; the additional sex comb-like proteins ASXL1 and ASXL2 (ASXL1/2); the forkhead transcription factors FOXK1 and FOXK2; as well as the zinc finger transcription factor Yin Yang 1 (YY1) (22, 25, 26). BAP1 is recruited at gene promoter regions to activate transcription, and has been shown to regulate the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation (15, 26, 27). BAP1 is also recruited to sites of DNA double strand breaks to promote repair by homologous recombination (24, 28), and it is implicated in DNA replication-associated processes (29, 30). Moreover, BAP1 functions appear to be regulated by post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination (24, 30, 31). Nonetheless, the mechanism by which BAP1 function is coordinated by its partners remains poorly defined.

Calypso, the Drosophila ortholog of BAP1, is a Polycomb group (PcG) protein that interacts with the transcriptional regulator ASX and assembles the Polycomb-repressive DUB complex that deubiquitinates histone H2A Lys-118 (H2A Lys-119 in vertebrates, hereafter H2Aub) and promotes PcG target gene repression (32). Although the exact mechanism of repression remains unknown, it is interesting to note that the Polycomb-repressive complex 1 (PRC1), which catalyzes H2A ubiquitination, is also required for PcG target gene repression (33). Drosophila ASX protein is an atypical PcG factor, because it is involved in both transcriptional silencing and activation (34, 35). ASXL1 and ASXL2 (hereafter ASXL1/2) are paralogs that appear to have diverged from ASX during evolution and are reported to function with a number of co-repressors and co-activators, notably the lysine-specific demethylase KDM1A/LSD1, the PcG complex PRC2, and the trithorax group epigenetic regulators (36–39). Similar to the Polycomb-repressive DUB complex, a minimal complex containing mammalian BAP1 and the N-terminal region of ASXL1 was shown to deubiquitinate H2A in vitro, indicating the requirement of ASX or ASXL1 for DUB activity (32). The DUB activity of BAP1 toward histone H2A Lys-119 was also observed in vivo (20, 24, 27, 40). BAP1 was also shown to deubiquitinate and stabilize some of its interacting partners, including HCF-1 and OGT indicating the functional importance of its catalytic activity (19, 22, 23). ASXL1/2 contain two uncharacterized N-terminal domains, ASXN and ASXM, and a C-terminal plant homeodomain finger (36, 41). Interestingly, the DUB activity of a BAP1 family member, UCH37, is stimulated by RPN13 (ADRM1) 19S proteasome subunit (42–44), and phylogenetic studies suggest that RPN13 and ASXL1/2 share a conserved domain termed the DEUBiquitinase ADaptor (DEUBAD) domain corresponding to ASXM (45). This suggests that BAP1/ASXL1/2 might use a similar mechanism of DUB activation as UCH37/RPN13.

The genes encoding ASXL1/2 are involved in chromosomal translocations and are frequently truncated in various cancer types (46). ASXL1 is frequently mutated in myeloid malignancies. Most of these mutations generate truncated ASXL1 proteins that retain the N-terminal region required for interaction with BAP1 (32). Although ASXL1 interaction with BAP1 was initially revealed to be dispensable for leukemia development (39), it was recently shown that leukemia-associated mutations of ASXL1 lead to an aberrant enhancement of BAP1 DUB activity (47). Moreover, expression of these ASXL1 constructs in hematopoietic precursor cell line causes an overall depletion of H2Aub associated with defects in myeloid differentiation (47). However, the involvement of this interaction in other cancers remains unknown. In addition, the specific contribution of ASXL1 and ASXL2 to BAP1 function remains undefined. Here, we sought to determine how ASXL1/2 modulates the H2A DUB activity of BAP1, and the relevance of these factors for BAP1 tumor suppressor function. We mapped the exact interaction domains and motifs between BAP1 and ASXL1/2 and demonstrated that ASXL1/2 form two mutually exclusive complexes with BAP1, both of which are competent in deubiquitinating H2A. Furthermore, we showed that the loss of BAP1 expression in cancer is concomitant with a destabilization of ASXL2. We also found that the ASXM domain of ASXL1/2 is prerequisite for ubiquitin binding and deubiquitination by BAP1. Moreover, we found that BAP1 catalytic and non-catalytic domains form, along with the ASXM domain, a composite ubiquitin-binding interface (CUBI) required for promoting BAP1 DUB activity by ASXL1/2 and coordination of cell proliferation. Finally, we identified a cancer-derived mutation of BAP1 CTD, ΔR666-H669, which results in a selective loss of interaction with ASXL1/2 and inhibition of H2A DUB activity. The ΔR666-H669 mutation also abolishes the ability of BAP1/ASXL2 axis to regulate cell proliferation and cellular senescence, thus providing a link between BAP1 function and mechanisms of tumor suppression.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmids

Retroviral constructs pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1, pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1 C91S (catalytic dead), and pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1ΔHBM (BAP1 mutant deleted in the NHNY sequence corresponding to the HCF-1-binding motif), constructs to produce recombinant full-length GST-BAP1 and various deleted forms, and pET30a+ BAP1 for production of His-tagged BAP1 were previously described (26). pCDNA3-FLAG-H2A was obtained from M. Oren (48). pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1 ΔCTD1 and pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1 ΔCC2 were generated by PCR-based subcloning. Non-tagged pCDNA3-BAP1 and pCDNA3-BAP1-C91S were generated by subcloning the cDNAs from pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1 and pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-BAP1-C91S, respectively. siRNA-resistant constructs for BAP1, BAP1-C91S, BAP1 ΔCTD, BAP1R666-H669 were generated using gene synthesis (BioBasic) and then subcloned into modified pENTR D-Topo plasmid (Life Technologies, Inc.). Expression constructs of siRNA-resistant BAP1, BAP1 C91S, BAP1 ΔCTD, and BAP1 ΔR666-H669 were generated by recombination using LR clonase kit (Life Technologies, Inc.) into pMSCV-FLAG-HA-IRES-Puro or pDEST-Myc constructs (25). BAP1ΔUCH, BAP1ΔCC1, and BAP1ΔCTD were described (31) and were subcloned by PCR into pENTR. Ubiquitin constructs (Ub wild type, Ub VLI (V70A/L8A/I44A), Ub I36A, Ub I44A, and Ub D58A) flanked by att-B and att-P recombination sites were generated by gene synthesis (Life Technologies, Inc.) directly into pMK-Rq plasmid, and bacterial expression constructs were generated by recombination into pDEST-GST. Other ubiquitin mutants constructs (Ub TEK (K6A/L11A/T12A/T14A/E34A), Ub Il36 patch (L8A/I36A/L71A/L73A), Ub IL44 patch (L8A/L44A/H68A/V70A), Ub Phe-4 patch (Q2A/F4A/T14A), Ub (Q49A/R72A), and Ub (R42A/Q49A/D52A/R72A)) flanked by att-B and att-P recombination sites were generated by gene synthesis (BioBasic) directly into pUC57-Kan vector, and bacterial expression constructs were generated by recombination into pDEST-GST. Human cDNA ASXL1 (NCBI NM_015338.5) and ASXL2 (NCBI NM_018263.4) were cloned from HeLa total RNA by reverse transcription and inserted into pENTR D-Topo plasmid. BAP1 point mutations constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis in pENTR D-Topo BAP1 using PfuUltra high fidelity DNA polymerase. Human Myc-ASXL1 ΔASXM and Myc-ASXL2 ΔASXM constructs were generated by PCR-based subcloning of two fragments each ligated in-frame into pENTR D-Topo. Expression constructs of ASXL1, ASXL2 and corresponding vectors with deletions of ASXM were generated in pDEST-Myc and pDEST-FLAG. Other expression constructs for BAP1 and corresponding mutants forms were generated using LR clonase in pDEST-Myc, pDEST-FLAG, and bacterial pDEST-His. Full-length ASXM1 and ASXM2 and deletions mutants forms of ASXM2 (ASXM2(246–313-aa), ASXM2(300–401-aa), ASXM2(316–401-aa), and ASXM2(246–347-aa)) were subcloned by PCR and inserted into pENTR D-Topo plasmid. ASXM2 point mutation constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis in pENTR D-Topo ASXM2. Bacterial expression vectors of ASXM1, ASXM2, and respective mutant forms were generated in pDEST-GST and pDEST-MBP vectors. Human PAR-4 was cloned in-frame with GFP in pCDNA3 using PCR.

Cell Culture and Cell Transfection

Primary human skin fibroblasts (LF1), BAP1-deficient human lung squamous carcinoma NCI-H226, BAP1-deficient human mesothelioma NCI-H28, U2OS osteosarcoma, human embryonic kidney HEK293T (293T), cervical cancer HeLa, normal human lung fibroblasts (IMR90), phoenix ampho, and 293-GPG packaging cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. HeLa S3 cells were cultured in minimum essential media supplemented with FBS, l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin.

293T cells were transfected with the mammalian expressing vectors using polyethyleneimine (PEI) (Sigma). Three days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, or immunostaining.

Similar numbers of H226 BAP1-null cells stably expressing BAP1, BAP1C91S, or BAP1R666-H669 were seeded on the plates and cultured for 5 days. The clonogenic survival assay was essentially done as described before (24).

U2OS or LF1 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Inc.) with 200 pmol of either ON-TARGET plus non-targeting pool (D-001810) or ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool BAP1 (L-005791) (Thermo Scientific, Dharmacon) or with a pool of siRNA sequences purchased from Sigma targeting ASXL1 (pool of four oligonucleotides as follows: SASI_Hs02_00347642, SASI_Hs01_00200507, SASI_Hs01_00200508, and SASI_Hs01_00200509) and ASXL2 (two pools of four oligonucleotides, SASI_Hs01_00202197, SASI_Hs01_00202198, SASI_Hs01_00202199, SASI_Hs01_00202200 and SASI_Hs01_00202197, SASI_Hs01_00202200, SASI_Hs01_00202203, SASI_Hs01_00202201). Four days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting.

siRNA DUB Screen

HeLa cells were transfected with individual siRNA pool-targeting DUBs (ON-TARGETplus® SMARTpool® siRNA Library–human deubiquitinating enzymes) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Inc.). Three days post-transfection, cells were fixed and used for immunostaining with anti-H2Aub antibody, and the fluorescence signals were detected with a Fluoroskan AscentTM microplate fluorometer (Thermo Scientific), and the obtained values were used to derive the Z-scores. The screen was done in duplicate, and the values of H2Aub signals were normalized to DAPI staining.

qRT-PCR Analysis of mRNA Expression

Total RNA was used to prepare the cDNAs as described (26). The cDNAs were analyzed by real time PCR using SYBR Green DNA quantification kit (Life Technologies, Inc.) to determine levels of gene mRNAs. PCR was conducted on an Applied Biosystems® 7500 real time PCR systems (Life Technologies, Inc.). To ensure accurate quantification of mRNA, similar amounts of total RNA were complemented with an in vitro synthesized GAL4 mRNA, which was performed following the manufacturer's procedure (MAXIscript Kit Procedure, Life Technologies, Inc.). The transcript was synthesized from the pcDNA.3-GAL4 construct with the T7 promoter. The primers used are listed below. hASXL2-Forward, GAATCCAGGTGCGAAAAGTAC, and hASXL2-Reverse, GATGGAGACTGGAAAACGAGC and GAL4-Forward, CAACTGGGAGTGTCGCTACT, and GAL4-Reverse, AATCATGTCAAGGTCTTCTCGA.

Immunoblotting and Antibodies

Total cell extracts were used for SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting was done according to standard procedures (26). The band signals were acquired with a LAS-3000 LCD camera coupled to MultiGauge software (Fuji, Stamford, CT). Anti-FOXK2 rabbit polyclonal antibody was previously described (31). The rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-ASXL1 was generated using bacterially expressed fragment (700–950 amino acids of the human protein) with Pacific Immunology. Mouse monoclonal anti-BAP1 (C4, sc-28383), rabbit polyclonal anti-BAP1 (H300, sc-28236), rabbit polyclonal anti-YY1 (H414, sc-1703), rabbit polyclonal anti-OGT (H300, sc-32921), mouse monoclonal anti-CDC6 (180.2, sc-9964), mouse monoclonal anti-MCM6, mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin (B-5-1-2, sc-SC-23948), mouse monoclonal anti-p53 (DO-1, sc-126), mouse monoclonal anti-p16 (JC8, sc-56330), mouse monoclonal anti-MDM2 (SMP14, sc-965), rabbit polyclonal anti-FOXK1 (H-140, sc-134550), and mouse monoclonal anti-PARP1 (F2, sc-8007) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal anti-HCF-1 (A301-400A) and rabbit polyclonal anti-ASXL2 (A302-037A) were from Bethyl Laboratories. Mouse monoclonal anti-p21 (55643) was from Pharmingen. Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (M2) and rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (G7781) were from Sigma. Mouse monoclonal anti-Myc (9E10) was from Covance. Rabbit polyclonal anti-H2Aub Lys-119 (D27C4), mouse monoclonal anti-RB (4H1), rabbit polyclonal anti-pRB (Ser-807/811), and mouse monoclonal (HRP conjugated) anti-MBP (E8038) were from Cell Signaling. Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (MAB1501, clone C4) was from Millipore.

Immunodepletion and Immunoprecipitation

Immunodepletion experiments were done as described (26). Reciprocal immunoprecipitation from the BAP1 complexes was conducted essentially as described (31). Briefly, the purified BAP1 complexes were incubated with the indicated antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The immunodepleted complexes were recovered the next day with protein G-Sepharose beads saturated with 1% BSA. Co-immunoprecipitation was conducted as described (26).

Cell Lines with Stable Expression and Protein Complex Purification

HeLa S3 cell lines stably expressing FLAG-HA-BAP1, FLAG-HA-BAP1ΔCTD1, or FLAG-HA-BAP1R666-H669, H28 cell lines stably expressing FLAG-HA-BAP1 and FLAG-HA-BAP1C91S, as well as H226 cell lines stably expressing FLAG-HA-BAP1, FLAG-HA-BAP1C91S, and FLAG-HA- BAP1R666-H669 were generated following retroviral infection using pOZ-N-FLAG-HA-IRES-IL2R retroviral constructs and selection using anti-IL2 magnetic beads (Life Technologies, Inc.) (26). U2OS expressing siRNA-resistant FLAG-HA-BAP1, FLAG-HA-BAP1C91S, FLAG-HA-BAP1ΔCTD, and FLAG-HA-BAP1R666-H669 were generated following retroviral infection using pMSCV-FLAG-HA-IRES-Puro based constructs and selection with 3 μg/ml puromycin. Around 3 × 109 of HeLa S3 cells were used for the immunoaffinity purification of the different BAP1 complexes. The purification was done as described previously (31). Eluted complexes were used for silver stain, Western blot analysis, and in vitro ubiquitin pulldown and DUB assays.

In Vitro Interaction Assays

Protein interaction pulldown assays were conducted as described previously (26).

Ubiquitin Pulldown Interaction Assays

GST-ubiquitin immobilized beads and its corresponding mutant forms were purified using glutathione-agarose beads. For the ubiquitin-agarose pulldown interaction assays, His-BAP1 or the corresponding mutant forms (1.6 μg and 20 nm) were preincubated for 30 min to 1 h with GST-ASXM1 or GST-ASXM2 (2 μg each and 50 nm) or GST-ASXM2 deletion mutant forms at 4 °C in 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm PMSF, protease inhibitors mixture, and 2 mm DTT. The mixture was incubated for 3 h with ubiquitin-agarose beads (Boston Biochem), which were then washed six times with the same buffer. The associated proteins were eluted in Laemmli buffer and subjected to Western blotting. For the GST-ubiquitin (GST-Ub) pulldown interaction assays, His-BAP1 or His-BAP1 C91S or the recombinant BAP1 deletion mutants (1.6 μg and 20 nm) were preincubated for 30 min to 1 h with either MBP-ASM2 or its corresponding mutant forms (2 μg and 30 nm). The mixture was then incubated overnight with either GST-ubiquitin immobilized beads or mutant forms (3 μg and 80 nm). The beads were washed six times with the same buffer, and the associated proteins were subjected to Western blotting. For the GST-ubiquitin (GST-Ub) pulldown interaction assays using MBP-ASXM2 (2 μg and 30 nm) or MBP-CTD (3 μg and 40 nm), the purified proteins were incubated for 16 h with GST-ubiquitin immobilized beads (3 μg and 80 nm). The beads were washed six times with the same buffer, and the associated proteins were subjected to Western blotting.

Purification of the Nucleosomes and in Vitro DUB assay

Native nucleosomes were purified as described (24). The purified nucleosomes were used for the in vitro DUB assay using either FLAG-HA purified BAP1 complexes or bacterially purified His-BAP1 (8 ng and 2 pm) with or without bacterially purified GST-ASXM1/2 (10 ng and 4 pm) or MBP-ASXM2 (10 ng, 2,8 pm) as described (24). The DUB reaction was carried out in the reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, 1 mm MgCl2, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT) for the indicated times at 37 °C. The in vitro reaction was stopped by adding Laemmli buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Synchronization and Cell Cycle Analysis

U2OS cells were synchronized at the G1/S border using the method of thymidine (2 mm) double block and analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (49).

Immunofluorescence

The immunostaining procedure was carried as described previously (50).

Protein Sequence Analysis and Structure Modeling

Conservation of protein sequences was determined using Geneious 6.1.2 (Biomatters). The ubiquitin resolved three-dimensional structure PDB file (1UBQ) was downloaded from the PDB database. We used the Chimera software (UCSF Chimera Version 1.10) to visualize the three-dimensional structure and to highlight different ubiquitin interfaces.

Statistical Analysis

Most experiments were conducted at least three times. Quantifications were done for a representative experiment. DUB RNAi screen was conducted once. Cell counts for senescence studies were derived from one representative experiment and are shown as average with standard deviation.

Results

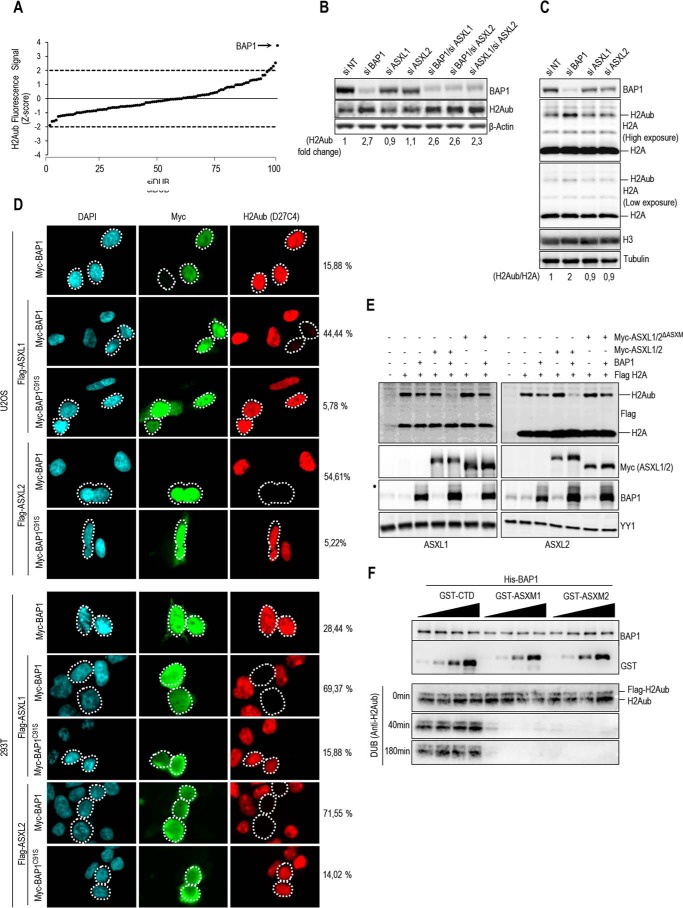

ASXL1 and ASXL2 Compete for Their Interaction with BAP1

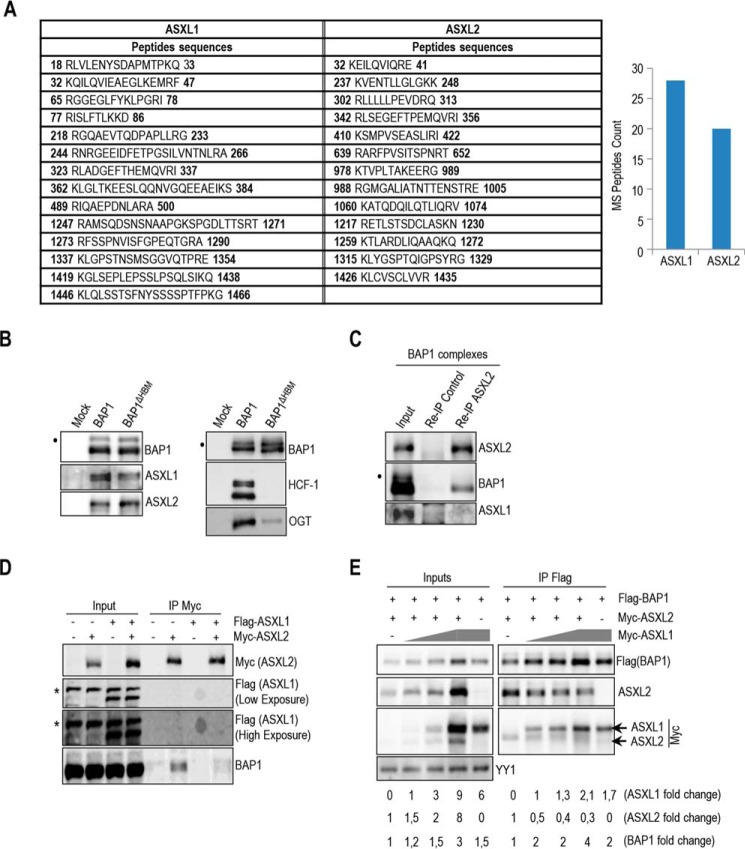

ASXL1 and ASXL2 factors co-purified with BAP1 (25, 26), and mass spectrometry peptide counts suggest that they are associated with BAP1 at similar levels (Fig. 1A). BAP1 interaction with ASXL1/2 was not affected by the loss of HCF-1, a major subunit of the BAP1 core complexes associated through its HCF-1-binding motif. We also note that the interaction between BAP1 and OGT is strongly reduced in the context of BAP1ΔHBM complexes, indicating that HCF-1 bridges OGT and BAP1 (Fig. 1B). We sought to further investigate the functional relationship between these factors. Immunoprecipitation (IP) of ASXL2 from purified BAP1 complexes did not show interaction with ASXL1 (Fig. 1C), and ASXL1 and ASXL2 failed to interact with each other following overexpression (Fig. 1D). We noted that BAP1 interaction with ASXL2 was reduced following expression of ASXL1 (Fig. 1D), suggesting that ASXL1 might compete with ASXL2 for BAP1 binding. To further confirm that ASXL1 and ASXL2 compete for interaction with BAP1, we overexpressed increasing amounts of ASXL1 with constant amounts of BAP1 and ASXL2 in 293T cells and conducted immunoprecipitation. Interestingly, although ASXL2 and BAP1 protein levels also increased following ASXL1 overexpression, we observed that ASXL2 was displaced from BAP1-containing protein complexes (Fig. 1E) indicating that ASXL1 and ASXL2 form two distinct complexes with BAP1.

FIGURE 1.

BAP1 interacts with either ASXL1 or ASXL2. A, BAP1 complexes contain relatively similar amounts of ASXL1/2 proteins. ASXL1/2 peptides were identified by mass spectrometry following the purification of BAP1 complexes from HeLa S3 cells. The amino acid positions of the peptides are indicated. B, HCF-1 is not required to maintain the interaction between BAP1 and ASXL1/2. Purification of BAP1 or BAP1ΔHBM (lacking the HCF-1-binding motif) complexes and detection of ASXL1/2 and BAP1 were done by immunoblotting (left panel). The immunopurified proteins were also analyzed by immunoblotting to detect the two major components of the BAP1 complexes, HCF-1 and OGT (right panel). Note that OGT is greatly reduced in the BAP1ΔHBM complexes due to the absence of HCF-1. C, reciprocal immunoprecipitation (Re-IP) of ASXL2 from the purified BAP1 complexes. D, 293T cells were transfected with Myc-ASXL2 (6 μg) with or without FLAG-ASXL1 (4 μg) expression vectors and harvested, 3 days later, for IP of Myc (ASXL2). E, 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-BAP1 (0.1 μg) and Myc-ASXL2 (3 μg) constructs in the presence of increasing amounts of Myc-ASXL1 construct (1, 2, and 5 μg) and harvested, 3 days later, for IP of BAP1 using anti-FLAG. Overexpressed Myc-ASXL2 was detected with anti-ASXL2 and anti-Myc antibodies. ASXL1 was detected with anti-Myc antibody. The difference in molecular weight allows discrimination between ASXL1 and ASXL2 bands. YY1 is used as a loading control. Quantification of band intensity for each protein was conducted relative to the lowest amount of transfected plasmid. The dot and the asterisk indicate a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (31) and nonspecific bands, respectively (B–D).

BAP1 and ASXL1/2 Are Co-regulated and Loss of BAP1 in Cancer Is Concomitant with ASXL2 Destabilization

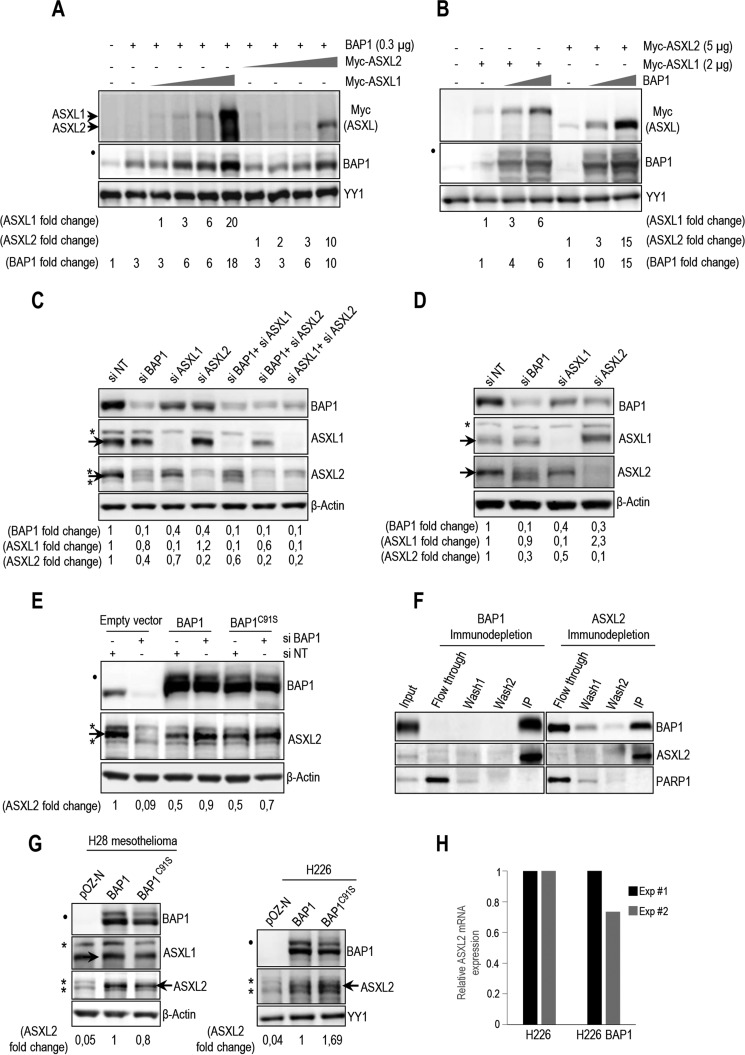

To further investigate the relevance of ASXL1 and ASXL2 in regulating BAP1 function, we transfected 293T cells with BAP1 and increasing amounts of Myc-tagged ASXL1/2-expressing constructs. We found that BAP1 protein levels increased with ASXL1/2 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Conversely, ASXL1/2 protein levels were also increased following overexpression of BAP1 (Fig. 2B). siRNA knockdown of either ASXL1 or ASXL2 in U2OS osteosarcoma cells or primary human fibroblasts resulted in a significant decrease of BAP1 protein levels (Fig. 2C,D), although combined knockdown of ASXL1/2 caused an even stronger decrease of BAP1 levels than depletion of individual proteins (Fig. 2C). This indicates that ASXL1/2 are necessary for maintaining proper protein levels of this DUB. We also observed that depletion of ASXL1 resulted in a noticeable decrease of ASXL2, although knockdown of ASXL2 caused an increase of ASXL1 (Fig. 2, C and D). Knockdown of BAP1 strongly reduced ASXL2 levels. This effect is independent of BAP1 DUB activity, as the decrease of ASXL2 protein in U2OS cells was prevented by re-expression of siRNA-resistant forms of BAP1, either wild type or catalytically dead mutant, BAP1C91S (Fig. 2E). The dependence of ASXL2 protein levels on BAP1 abundance suggests that ASXL2/BAP1 may form an obligate complex. Consistently, immunodepletion of endogenous proteins from HeLa nuclear extracts revealed that the majority of ASXL2 is associated with BAP1 (Fig. 2F). However, only about half the amount of BAP1 is in complex with ASXL2. PARP1 was used as a control, which remained in the flow-through fraction. Significantly, ASXL2 was down-regulated in BAP1-deficient H28 mesothelioma and H226 lung carcinoma cells, and re-expression of BAP1 or BAP1C91S restored ASXL2 protein levels in these cells, without affecting its mRNA levels (Fig. 2G,H). These data suggest that BAP1/ASXL1/2 interactions are regulated and that loss of BAP1 during cancer development results in concomitant loss of ASXL2 protein and function.

FIGURE 2.

BAP1 and ASXL1/2 are co-regulated, and loss of BAP1 in cancer is concomitant with ASXL2 depletion. A, 293T cells were transfected with BAP1 and increasing amounts of either Myc-ASXL1 (0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μg) or Myc-ASXL2 (0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μg) expression vectors and harvested, 3 days later, for immunoblotting. B, 293T cells were transfected with Myc-ASXL1 or Myc-ASXL2 with increasing amounts of BAP1 (0.3 and 1 μg) vectors and harvested, 3 days later, for immunoblotting. Quantification of band intensity for each protein was conducted relative to the lowest amount of transfected plasmid (A and B). C, protein levels following siRNA depletion of BAP1 and/or ASXL1/2 in U2OS cells. D, protein expression following siRNA depletion of BAP1, ASXL1, and ASXL2 in LF1 human fibroblasts. E, depletion of endogenous BAP1 using siRNA in U2OS cells stably expressing empty vector, siRNA-resistant BAP1 wild type, or siRNA-resistant BAP1 catalytic dead mutant (C91S). Protein levels of BAP1 and ASXL2 were detected by immunoblotting. Quantification of band intensity was conducted relative to the non-target siRNA control (C–E). F, immunodepletion of BAP1 or ASXL2 from HeLa nuclear extracts. The nuclear DNA damage signaling enzyme, PARP1, was used as a control, which mostly remained in the flow-through fraction. G, reconstitution by retroviral infection of H28 mesothelioma and H226 non-small lung carcinoma BAP1-deficient cells with BAP1 or BAP1C91S. Protein levels of BAP1 and mutants were detected by immunoblotting. H, mRNA of ASXL2 in reconstituted H226 cells was quantified by quantitative PCR. The data represent two independent experiments. β-Actin or YY1 are used as protein loading controls. Quantification of band intensity was conducted relative to BAP1-transfected samples (G). The dot and asterisks indicate a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (31) and nonspecific bands, respectively (A–E and G).

ASXM Domain of ASXL1/2 Is Required for Interaction with the CTD of BAP1

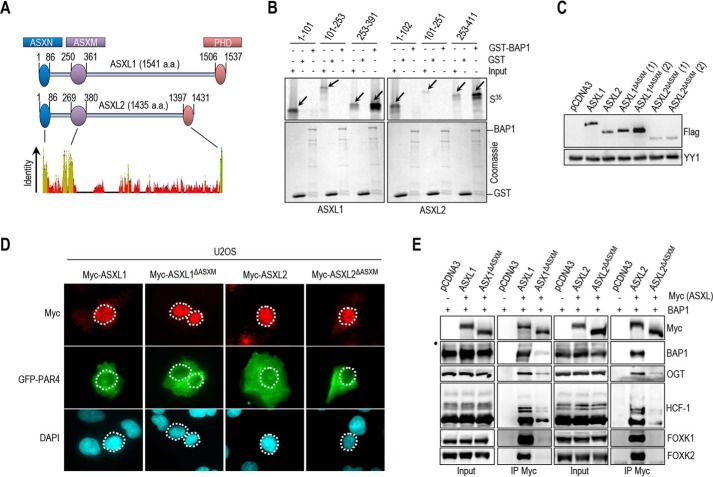

BAP1 was shown to interact with the N-terminal region of ASXL1 (1–337 aa) (32). To identify the exact domain of ASXL1/2 responsible for this interaction, we conducted GST-pulldown assays and found that in vitro-translated ASXM domain (ASXM1, 253–391 aa; ASXM2, 253–411 aa of ASXL1 and ASXL2, respectively) interacted with GST-BAP1 (Fig. 3A and B). To gain insights into the significance of the BAP1/ASXL1/2 interactions, we generated ASXL1/2 expression constructs lacking the BAP1-interacting domain (ASXL1/2ΔASXM). As expected, following transfection, protein levels of ASXL2ΔASXM, but not ASXL1ΔASXM, were reduced in comparison with their wild type counterparts (Fig. 3C). Of note, the polypeptides encoded by the ASXL1/2 constructs were essentially nuclear (Fig. 3D). GFP-PAR-4 fusion protein, which localizes in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, was included as a control (51). Next, after adjusting the amounts of transfected plasmids to obtain comparable expression of the wild type and mutant forms of ASXL1/2, we found that the ability of ASXL1/2 mutants, lacking their respective ASXM domain, to interact with BAP1 and to form protein complexes in vivo was strongly reduced (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

ASXM of ASXL1/2 is required for interaction with BAP1. A, schematic representation and conservation of ASXL1/2. B, GST pulldown assay using GST-BAP1 and methionine 35S-labeled ASXL1 or ASXL2 fragments. The arrows indicate the full-length forms of the fragments. C, ASXM is required for ASXL2, but not ASXL1, stability. FLAG-ASXL1/2 and their respective FLAG-ASXL1/2 ΔASXM mutants (3 μg each) were transfected in 293T cells which were harvested, 3 days post-transfection, for immunoblotting. A duplicate of transfection is shown for FLAG-ASXL1/2 ΔASXM mutants. D, U2OS cells were transfected with either Myc-ASXL1 (4 μg), Myc-ASXL1 ΔASXM (4 μg), Myc-ASXL2 (4 μg), or Myc-ASXL2 ΔASXM (4 μg) along with GFP-PAR4 (0.5 μg). Three days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunostaining using the indicated antibodies. The cells overexpressing the different forms of ASXL1/2 were encircled. E, 293T cells were transfected with Myc-ASXL1 (4 μg), Myc-ASXL1 ΔASXM (4 μg), Myc-ASXL2 (4 μg), or Myc-ASXL2 ΔASXM (6 μg), along with BAP1 (1 μg) vectors and harvested, 3 days post-transfection, for IP with anti-Myc. The dot indicates a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (E) (31).

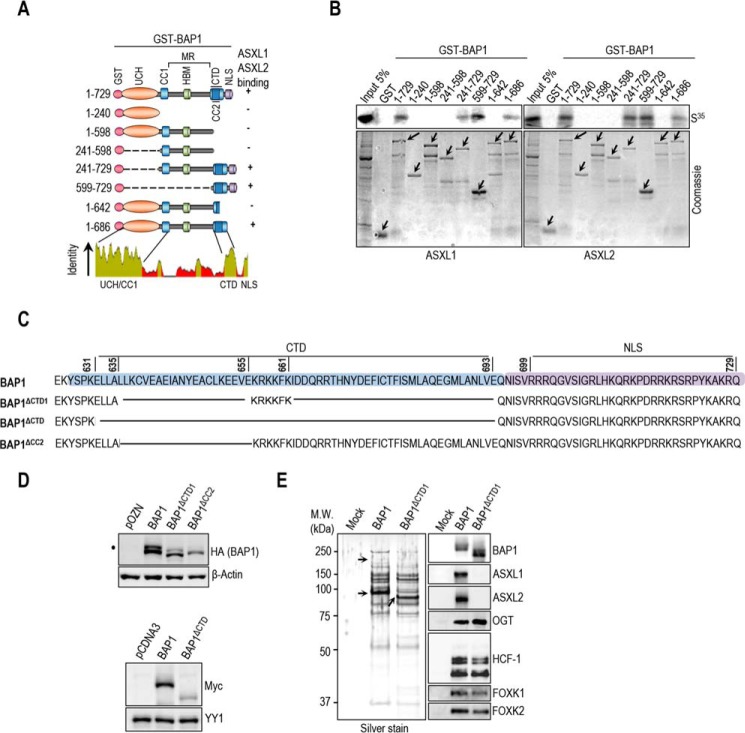

BAP1 contains a ubiquitin carboxyl hydrolase (UCH) catalytic domain and a coiled-coil motif (CC1) in the N-terminal region, as well as a C-terminal domain (CTD) containing a second coiled-coil motif (CC2) (Fig. 4A) (12, 23, 31). This DUB also possesses a big middle region that contains the HBM and other protein interaction motifs, separating UCH/CC1 from the CTD (12, 23, 40, 52). We found that only GST-tagged fragments of BAP1 containing an intact CTD interacted with ASXM domains of ASXL1/2 (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that ASXL1/2 use the ASXM domain to interact with the CTD of BAP1. To provide further insights into ASXL1/2/BAP1 interactions, we constructed BAP1 mutants disrupted in the CTD region (Fig. 4C). BAP1ΔCTD1 represents a deletion of CTD except for the KRKKFK putative nuclear localization signal (21). BAP1ΔCTD and BAP1ΔCC2 represent a complete deletion of the CTD and CC2, respectively. Supporting our findings reported above, we noticed that disruption of CTD resulted in decreased BAP1 protein levels (Fig. 4D). We also generated HeLa cell lines stably expressing BAP1 wild type or its mutant form lacking most of the CTD, BAP1ΔCTD1, and we used them for complex purification. To enable meaningful comparisons, the eluted complexes were adjusted by immunoblotting for similar amounts of BAP1 protein prior to silver staining. This revealed that BAP1 and BAP1ΔCTD1 complexes were quite similar in protein composition (Fig. 4E). However, immunoblotting analysis showed that the interaction between BAP1ΔCTD1 and ASXL1/2 was abolished (Fig. 4E). In contrast, association of BAP1ΔCTD1 with HCF-1/OGT remained unchanged in comparison with the wild type variant. Altogether, these results indicate that CTD and ASXM domains are necessary and sufficient for assembly of BAP1-ASXL1/2 complexes.

FIGURE 4.

BAP1 interacts with ASXL1/2 via its CTD domain. A, schematic representation of the BAP1 fragments used for in vitro pulldown in B. B, GST-pulldown assay using GST-BAP1 fragments and methionine 35S-labeled ASXM domains of ASXL1 or ASXL2. The arrows indicate the full-length forms of the fragments. C, schema of the different deletions in the CTD domain used to generate BAP1 mutants. BAP1ΔCTD1 represents a deletion of the CTD from 635 up to 693 amino acids except the KRKKFK motif, which is suggested to function as an NLS (21). We also generated a BAP1ΔCTD, which represents a mutant with a deletion of the CTD domain (Δ631–693 amino acids). BAP1ΔCC2 represents a mutant with a smaller deletion within the CTD domain (Δ635–655 amino acids). D, functional CTD is required for proper protein stability of BAP1. Protein expression levels of BAP1 and its CTD deletion mutant form in stable HeLa S cell lines are shown (top panel). Myc-BAP1, Myc-BAP1 ΔCTD expression constructs (3 μg each) were transfected in 293T cells, which were harvested, 3 days post-transfection, for immunoblotting (bottom panel). E, left panel, silver stain of the immunopurified BAP1 and BAP1ΔCTD1 complexes. Right panel, Western blot detection of components of the BAP1 complexes. The high and low arrows indicate the position of ASXL2 and BAP1 (WT and BAP1ΔCTD1), respectively. β-Actin or YY1 are used as protein loading controls. The dot indicates a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (D) (31).

BAP1 Is a Major DUB for H2Aub Lys-119 and Its Enzymatic Activity Is ASXM-dependent

Several DUBs, including BAP1, were reported to target H2Aub Lys-119 in mammals (4, 53). However, the relative contribution of each enzyme in H2A deubiquitination in vivo remained unknown. We conducted an siRNA screen using a library that covers the human DUB repertoire by analyzing the global increase of H2Aub using an in-cell Western assay. Depletion of BAP1 produced the most significant increase of H2Aub, indicating that this enzyme is a major DUB for this histone modification under normal growth conditions (Fig. 5A). To investigate how ASXL1/2 regulate mammalian BAP1 DUB activity in vivo, we conducted RNAi-mediated depletion of these factors, and we found that neither ASXL1 nor ASXL2 individual knockdown induced noticeable changes in global H2Aub levels (Fig. 5, B and C). However, combined knockdown of ASXL1 and ASXL2 resulted in significant increase of H2Aub, similar to the effect induced by BAP1 depletion (Fig. 5B). This prompted us to determine the respective contribution of ASXL1 and ASXL2 to the H2A DUB activity of BAP1. A striking BAP1-mediated deubiquitination of H2A was observed upon its co-expression with either ASXL1 or ASXL2, and this effect was dependent on BAP1 catalytic activity (Fig. 5D). Consistent with our mapping analysis, ASXL1 and ASXL2 lacking ASXM were unable to stimulate H2A deubiquitination (Fig. 5E). In addition, we purified monoubiquitinated nucleosomal FLAG-H2A, from 293T cells, that we used for in vitro DUB assay and found that ASXM1 or ASXM2, but not GST-CTD used as a control, is sufficient for stimulating BAP1-mediated deubiquitination of H2A (Fig. 5F). Based on these results, we concluded that interaction between ASXL1/2 and BAP1 requires ASXM, and the latter is necessary and sufficient for promoting BAP1-mediated deubiquitination of its physiological substrate H2Aub Lys-119.

FIGURE 5.

ASXM of ASXL1/2 stimulates BAP1 DUB activity. A, siRNA screen for DUBs that coordinate H2Aub levels. Following transfection with siRNA DUB library, HeLa cells were fixed and immunostained for H2Aub Lys-119 (H2Aub). The fluorescence signal was determined, and the values were used to derive the Z scores. B, knockdown of BAP1 or concomitant Knockdown of ASXL1 and ASXL2 induces a significant increase of the global level of H2Aub. U2OS cells were transfected with siRNA as indicated and harvested 4 days post-transfection for immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Quantification of band intensity for H2Aub was conducted relative to the non-target siRNA control (siNT). C, increase of H2Aub levels following BAP1 depletion is not due to a global increase of H2A. U2OS cells were transfected with siRNA of BAP1, ASXL1, and ASXL2 and harvested, 4 days post-transfection, for immunoblotting using the respective antibodies. Tubulin was used a loading control for soluble proteins and histone H3 as a loading control for histones levels. Quantification of band intensity for H2Aub was conducted relative to the non-modified histone H2, and the values were then normalized to the non-target siRNA control (siNT). D, ASXL1/2 promote BAP1 DUB activity toward H2Aub in vivo. U2OS cells (top panel) or 293T cells (bottom panel) were transfected with either Myc-BAP1 (0.5 μg) or Myc-BAP1 C91S (0.5 μg) expression constructs in the presence or absence of FLAG-ASXL1/2 (4 μg) expression constructs. Three days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunostaining using the indicated antibodies. The cells overexpressing BAP1 and BAP1C91S were encircled. Note that the transfections were conducted with plasmid ratios optimized to ensure that most BAP1-transfected cells also express ASXL1 or ASXL2. Cells overexpressing BAP1 were counted for change in H2Aub signal. The percentages at the right of the panel represent the number of cells showing very low signal of H2Aub versus the total number of BAP1-expressing cells. E, 293T cells were transfected as indicated using FLAG H2A (0.2 μg), BAP1 (1 μg), Myc-ASXL1 (4 μg), or Myc-ASXL1 ΔASXM (4 μg) vectors (left panel) and Myc-ASXL2 (4 μg) or Myc-ASXL2 ΔASXM (6 μg) vectors (right panel) and harvested, 3 days later, for immunoblotting. F, in vitro DUB assay of nucleosomal H2A using recombinant His-BAP1 (8 ng, 2 pm) in the presence of increasing amounts of recombinant GST-CTD, GST-ASXM1, or GST-ASXM2 (0.6, 1.2, 2, and 4 pm). β-Actin, tubulin, or YY1 was used as loading controls.

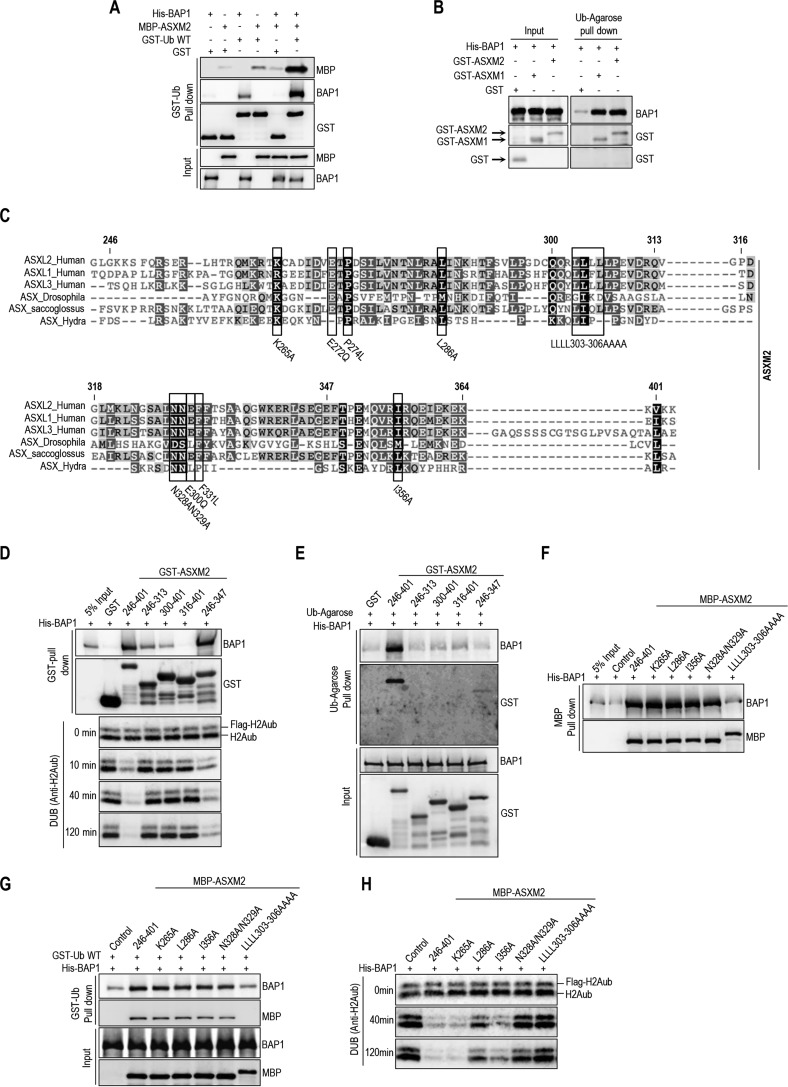

Identification of Domains and Motifs in ASXM Required for Promoting Ubiquitin Binding and DUB Activity toward Histone H2A of BAP1

To further dissect the mechanism of H2A deubiquitination by BAP1, we conducted ubiquitin pulldown assays and found that ASXM2 strongly enhanced BAP1 binding to ubiquitin (Fig. 6A). ASXM2 alone can directly bind ubiquitin, but this interaction was weak as an enrichment of about 2-fold above the background was observed (Fig. 6A). ASXM1 also promoted BAP1 binding to ubiquitin in a similar manner as ASXM2 (Fig. 6B). Because ASXM1 and ASXM2 domains acted similarly in promoting BAP1 binding to ubiquitin and DUB activity, we selected ASXM2 for further studies. Sequence alignment of ASXL proteins indicated that the ASXM domain is highly conserved (Fig. 6C). We generated several constructs encompassing several regions and conserved motifs of ASXM2 (Fig. 6C). We found that the 246–347-aa region interacted with BAP1 as efficiently as the full-length ASXM2(246–401-aa), although no interaction was observed for the 316–401-aa region (Fig. 6D). The 246–313- and 300–401-aa regions interacted only poorly with BAP1. These results suggest that critical interaction motifs are located within or overlapping with the 300–347-aa region (Fig. 6D). Only the full-length ASXM2 and the 246–347-aa fragment, which strongly interacted with BAP1, promoted its binding to ubiquitin and DUB activity. Nonetheless, we noted that the 246–347-aa fragment was significantly less competent in promoting BAP1 binding to ubiquitin, which could explain its weakness in promoting deubiquitination (Fig. 6, D and E). Next, we generated discrete mutations of several highly conserved residues of ASXM2 (Fig. 6C), and we found that ASXM2 interaction with BAP1 and ubiquitin binding are maintained for most mutants except for the L303A/L304A/L305A/L306A hydrophobic stretch mutant, which essentially lost its interaction with BAP1 (Fig. 6, F and G). As expected, the L303A/L304A/L305A/L306A mutant failed to stimulate DUB activity (Fig. 6H). Interestingly, although the L286A and N328A/N329A mutants were essentially equally efficient in promoting BAP1 binding to ubiquitin, their ability to deubiquitinate H2A was significantly different (Fig. 6G and H).

FIGURE 6.

ASXM enhances BAP1 binding to ubiquitin. A, recombinant His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm) and MBP-ASXM2 (2 μg, 30 nm) were incubated with either GST or GST-ubiquitin-agarose beads (3 μg, 80 nm), and the pulldown fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting. B, recombinant His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm) and GST-ASXM1 or GST-ASXM2 (2 μg, 40 nm) were incubated with ubiquitin-agarose beads, and the pulldown fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting. C, multiple sequence alignment between the ASXM domains of human ASXL1/2, Drosophila ASX, and other paralogs and orthologs of ASX. The mutants of ASXM2, including the cancer-associated mutants used in F–H and Fig. 9, are shown. D, GST pulldown interaction assay and in vitro DUB reactions of H2A using His-BAP1 and GST-ASXM2 (full-length and deletion mutant forms). For the pulldown assay, His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm) was incubated with GST-ASXM2 (2 μg, 40 nm) or the different fragment of GST-ASXM2 (2 μg, 50 nm). His-BAP1 (8 ng, 2 pm) and the different recombinant ASXM2 fragments (10 ng, 4 pm) were used for the DUB reactions. E, His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm) and the different GST-fused fragments of ASXM2 (2 μg, 40 nm) were subjected to ubiquitin-agarose pulldown assay followed by immunoblotting. F, MBP-pulldown interaction assay using recombinant MBP-ASXM2 (full-length and mutant forms) (2 μg, 30 nm) and His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm). G, GST-ubiquitin pulldown assay using MBP-ASXM2 full-length and the different mutant forms with His-BAP1. The pulldown was done as in A. H, in vitro DUB reactions of H2A using His-BAP1 (8 ng, 2 pm) and the different recombinant MBP-ASXM2 (10 ng, 2.8 pm).

Intramolecular Interactions in BAP1 Create an ASXM-dependent CUBI and Enable DUB Activity

The CTD of BAP1 is necessary and sufficient for the interaction between BAP1 and ASXL1/2 (Fig. 4). This domain also engages an intramolecular interaction with both the CC1 and the UCH domains to ensure BAP1 auto-deubiquitination and proper nuclear localization (31). Hence, we sought to test whether this intramolecular interaction in BAP1 is necessary for ASXM stimulation of ubiquitin binding and DUB activity. Indeed, as is the case for BAP1ΔUCH or BAP1C91S, BAP1ΔCTD was unable to deubiquitinate H2A following incubation with ASXM2 (Fig. 7, A and B). BAP1ΔCTD or BAP1ΔCC2 mutants were also incapable of deubiquitinating H2A in the context of BAP1 protein complexes in vitro (Fig. 7C), As a control, BAP1ΔHBM complexes were competent in promoting DUB activity (Fig. 7D), as shown previously (20). BAP1ΔCTD was also unable to promote BAP1 DUB activity in vivo when expressed with either ASXL1 or ASXL2 (Fig. 7E). In addition, although ASXM2 promoted binding to ubiquitin of both BAP1 and BAP1C91S, this domain failed to enhance ubiquitin binding of BAP1ΔCTD or BAP1ΔUCH (Fig. 7F). ASXM2 only partially promoted BAP1ΔCC1 binding to ubiquitin (Fig. 7, A and F), and this mutant is completely inactive in H2A deubiquitination (Fig. 7B). Thus, ASXM2 requires intramolecular interactions between multiple domains of BAP1 to promote ubiquitin binding and catalysis.

FIGURE 7.

Intramolecular interaction in BAP1 is required to create an ASXM-inducible CUBI. A, schematic representation of the different BAP1 mutants generated for in vitro experiments done in B. B, in vitro DUB reaction of nucleosomal H2A using His-BAP1 or its mutant forms (8 ng, 2 pm) in the presence or absence of MBP-ASXM2 (10 ng, 2,8 pm). C and D, in vitro deubiquitination assay of nucleosomal histone H2A using purified FLAG-HA BAP1, BAP1ΔCTD1, or BAP1ΔCC2 complexes. BAP1ΔHBM was used as a control because HCF-1 is not required for BAP1 DUB activity. E, in vivo DUB activity of BAP1ΔCTD is abolished due to the lack of interaction with ASXL1/2. FLAG-H2A (0.2 μg) expression construct was co-expressed in 293T cells with either Myc-BAP1 (1 μg) or Myc-BAP1 ΔCTD (1 μg) with or without Myc-ASXL1 (4 μg) or Myc-ASXL2 (6 μg) expression constructs. Three days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting. YY1 is used as a loading control. F, His-BAP1 mutants (1.6 μg, 20 nm) and MBP-ASXM2 (2 μg, 30 nm) were subjected to GST-ubiquitin pulldown assay followed by immunoblotting.

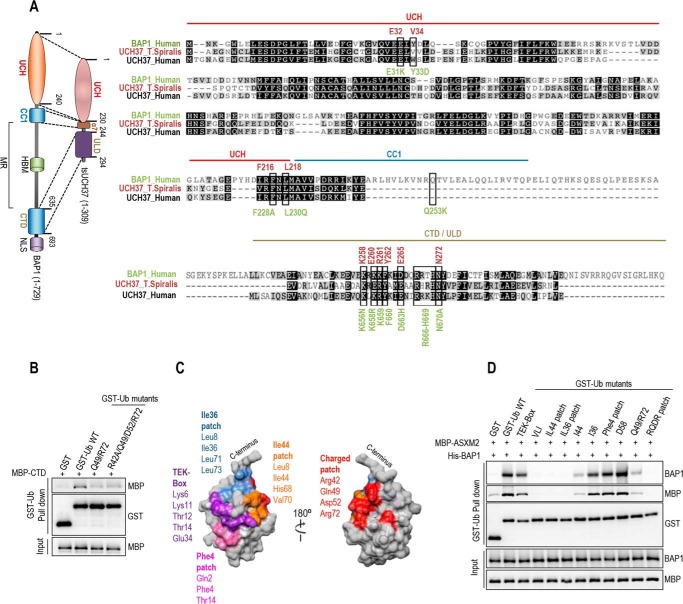

In contrast to the CC1 and CTD in BAP1, the corresponding domains in UCH37, helix α7, and ULD, respectively, are contiguous (Fig. 8A, left panel) (54). Nonetheless, co-crystallization of UCH37 of the worm Trichinella spiralis (tsUCH37) with ubiquitin indicated an intramolecular interaction similar to the one observed in BAP1 (54). In addition, Arg-261 and Tyr-262 residues of the ULD establish direct contacts with ubiquitin Lys-48 and Gln-49/Arg-72, respectively (54). Molecular dynamics simulation suggested that Glu-265 and Asn-272, part of a non-crystallized extension of the ULD, might also bind Arg-42 and Asp-52 of ubiquitin, respectively (54). Arg-261, Tyr-262, Glu-265, and Asn-272 are essentially conserved in BAP1 and correspond to Lys-659, Phe-660, Asp-663, and Asn-670, respectively (Fig. 8A, right panel). Thus, we were prompted to test whether the CTD is sufficient for binding ubiquitin in solution. We found that the CTD weakly interacted with ubiquitin, as a signal above the background was consistently observed (Fig. 8B). Importantly, mutation of ubiquitin Arg-42/Gln-49/Asp-52/Arg-72 residues (we termed the RQDR charged patch), involved in binding the tsUCH37 ULD, reduced this interaction (Fig. 8, B and C). Moreover, mutation of the RQDR patch also abolished ubiquitin binding by the BAP1-ASXM2 complex (Fig. 8D). Also, ubiquitin binding by BAP1-ASXM2 is completely abrogated by mutating the VLI, Ile-36 and Ile-144 hydrophobic patches of ubiquitin, which are involved in binding by the UCH domain (Fig. 8C and D) (54–56). These data indicate that the hydrophobic and the charged RQDR patches are necessary to ensure strong ubiquitin binding by the BAP1-ASXM2 complex. Finally, mutation of the TEK box, Phe-4 patch, or Asp-58 did not affect ubiquitin binding by BAP1-ASXM2 (Fig. 8, C and D). We concluded that ASXM induces the assembly of a composite ubiquitin-binding interface (CUBI) that requires catalytic and non-catalytic domains of BAP1 and involves multiple patches of ubiquitin.

FIGURE 8.

BAP1 CTD is a ubiquitin-interacting domain. A, comparison between BAP1 and UCH37. tsUCH37 of the worm T. spiralis, whose crystal structure was recently reported (38), was aligned with human UCH37 and BAP1. The functionally conserved domains between BAP1 and tsUCH37 are shown in the left panel. The alignment (right panel) shows conserved motifs and residues in the UCH, CC1, and CTD domains. The mutants of BAP1 including the cancer-associated mutants used in Fig. 9 are shown. Note the presence in the CTD of the cancer mutant BAP1R666-H669 with a deletion of the Arg-666 to His-669 amino acids. B, MBP-CTD (3 μg, 40 nm) of BAP1 was subjected to GST-ubiquitin pulldown assay using GST-ubiquitin wild type or its mutant forms (3 μg, 80 nm) (all residues were converted to alanines) and then analyzed by immunoblotting. C, ubiquitin structure showing the various interaction interfaces. D, GST-ubiquitin pulldown assay interaction assays using GST-ubiquitin wild type or its different mutant forms (all residues of each path were converted to alanines) and His-BAP1 with MBP-ASXM2 followed by immunoblotting. The pulldown was done as in Fig. 7F.

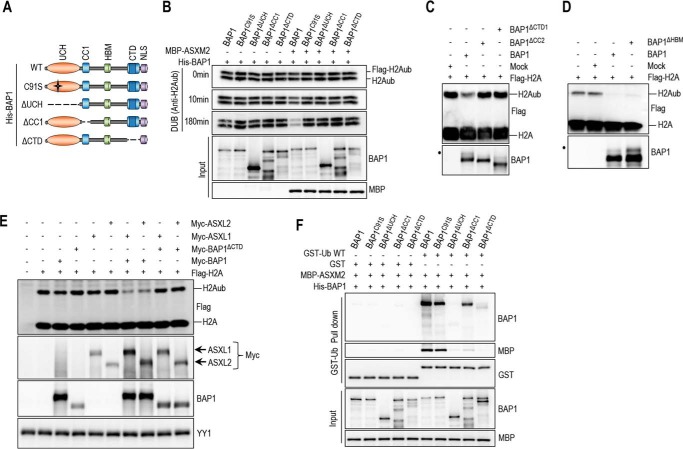

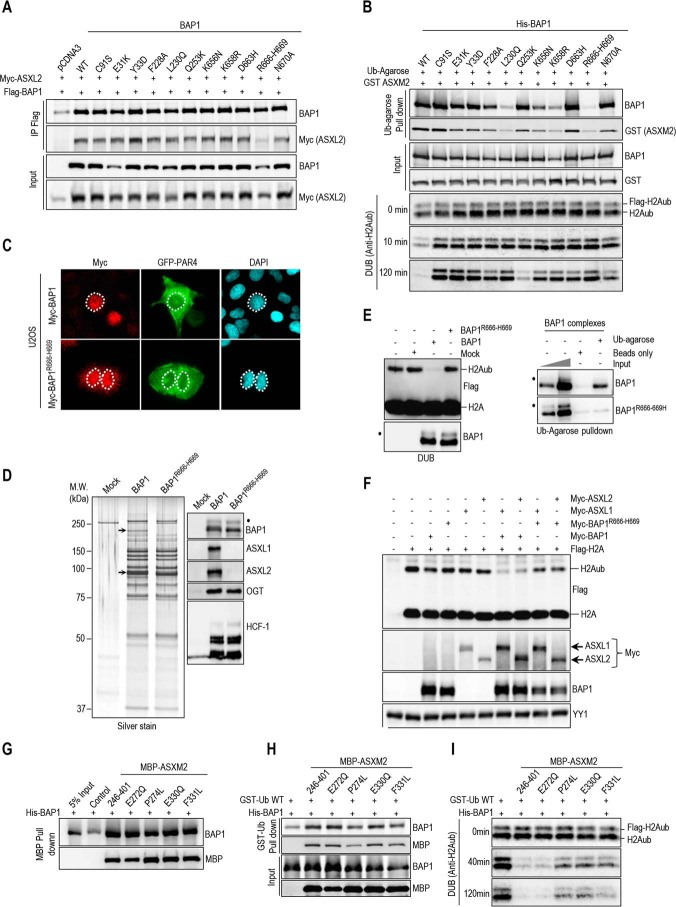

Cancer-derived Mutations Abolish BAP1 Interaction with ASXL1/2, Ubiquitin Binding, and DUB Activity

We asked whether tumor-associated mutations of BAP1 result in selective loss of interaction with ASXL1/2 and ubiquitin binding and catalysis. Based on our data and tsUCH37-ubiquitin co-crystal structure (54), we analyzed the previously reported cancer mutation landscape of BAP1 (cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics and COSMIC cancer databases), notably in solid tumors (e.g. uveal melanoma and renal cell carcinoma), and we selected several mutations within or near its UCH (E31K, Y33D), CC1 (L230Q, Q253K), and CTD (K656N, K658R, D663H, and R666-H669) domains (Fig. 8A) (13, 20). We also included additional mutations, not found in cancer, but corresponding to highly conserved amino acids in the vicinity of these cancer mutations (F228A, N670A) (Fig. 8A). We co-expressed these BAP1 mutants with ASXL2 and found that most mutations did not significantly affect protein interactions except for the R666-H669 mutant whose interaction with ASXL2 is strongly reduced (Fig. 9A). It is worth mentioning that although BAP1 and ASXL2 are overexpressed in 293T cells, reduced protein levels of R666-H669 mutant are still observed (Fig. 9A). In vitro ubiquitin pulldown interaction assays revealed that E31K and Y33D mutations in the UCH domain result in a reduced binding of BAP1/ASXM2 to ubiquitin (Fig. 9B). Significantly, several mutants in other domains, e.g. F228A, L230Q, K658R, and R666-H669, strongly affected the ability of BAP1/ASXM2 to bind ubiquitin (Fig. 9B). Most BAP1 mutants were also significantly disrupted in their ability to deubiquitinate H2A (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, the D663H mutant was essentially efficient in binding ASXM2 and ubiquitin but failed to promote efficient DUB activity. Because the deletion of amino acids R666-H669 abolished interaction with ASXL2, ubiquitin binding, and DUB activity, we selected this mutant for further biochemical and functional studies. Of note, BAP1R666-H669 is expressed predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 9C). We generated HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-HA-BAP1R666-H669 and conducted immuno-affinity purification of DUB complexes. After adjusting for similar amounts of immunopurified BAP1, we conducted silver staining of the eluted material. This indicated that R666-H669 mutation did not change the overall composition of BAP1 complexes as compared with the wild type, except for missing ASXL2 band in the purified BAP1R666-H669 complexes (Fig. 9D, left panel). ASXL1 co-migrates with other high molecular weight proteins and could not be discerned as a distinct band. Strikingly, Western blot analysis of the complexes indicated that BAP1R666-H669 does not interact with ASXL1/2, and interaction with HCF-1/OGT was not affected (Fig. 9D, right panel). Moreover, the purified BAP1R666-H669 complex was unable to deubiquitinate nucleosomal histone H2A (Fig. 9E, left panel) or to bind ubiquitin in vitro (Fig. 9E, right panel). Concordant with this data, neither full-length ASXL1 nor ASXL2 are capable of stimulating DUB activity by BAP1R666-H669 in vivo (Fig. 9F). To further investigate the disruption of BAP1/ASXL2 DUB activity in cancer, we selected several reported cancer-associated point mutations in ASXM2 (Fig. 6C), especially in solid tumors (e.g. breast carcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma), and we found that these mutations did not disrupt ASXM2 interaction with BAP1 (Fig. 9G). The BAP1-ASXM2 complex with the P274L mutation showed reduced binding to ubiquitin, although the ability of other mutants to bind ubiquitin was essentially unaffected (Fig. 9H). Finally, three of these mutants (P274L, E330Q, and F331L) showed reduced DUB activity toward H2A indicating that ASXL2 is also targeted by mutations that inhibit the enzymatic activity of the complex (Fig. 9I). Altogether, these results indicate that several cancer-associated mechanisms target the BAP1-/ASXL2 complexes inducing loss of ubiquitin binding and DUB activity.

FIGURE 9.

Disruption of BAP1 ubiquitin binding and DUB activity by cancer-associated mutations of BAP1 and ASXL2. A, R666-H669 BAP1 cancer mutation abolishes its interaction with ASXL2. Myc-ASXL2 (6 μg) construct was co-transfected in 293T with either FLAG-BAP1, FLAG-BAP1 C91S, or FLAG-BAP1 mutants constructs (1 μg), and cells were harvested for FLAG IP of BAP1 followed by immunoblotting. B, ubiquitin pulldown assay and in vitro DUB assays of nucleosomal H2A using GST-ASXM2 and His-BAP1, His-BAP1C91S, or the different recombinant mutant forms of BAP1. The same amounts of recombinant proteins as presented in Figs. 5–7 were used for the in vitro reactions. C, U2OS cells were transfected with either Myc-BAP1 (4 μg) or Myc-BAP1 R666-H669 (4 μg) along with GFP-PAR4 (0.5 μg). Three days later, cells were harvested for immunostaining using the indicated antibody. Cells expressing BAP1 or BAP1R666-H669 were encircled. D, BAP1 complexes were purified from HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-HA-BAP1 or FLAG-HA-BAP1R666-H669. Left panel, silver stain shows the profiles of the complexes. Right panel, Western blot detection of the major components of the BAP1 complexes. The high and low arrows indicate the position of ASXL2 and BAP1, respectively. E, in vitro DUB assay of nucleosomal H2A (top panel) and ubiquitin pulldown assay (bottom panel) using BAP1 and BAP1R666-H669 complexes. F, R666-H669 BAP1 cancer mutation results in the abrogation of its DUB activity in vivo. FLAG-H2A (0.2 μg) construct was co-expressed in 293T cells with either Myc-BAP1 (1 μg) or Myc-BAP1 R666-H669 (1 μg) with or without Myc-ASXL1 (4 μg) or Myc-ASXL2 (6 μg) expression constructs. Three days post-transfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting. G, His-BAP1 (1.6 μg, 20 nm) and MBP-cancer associated mutants forms of ASXM2 (2 μg, 30 nm) were subjected to MBP pulldown interaction assays. H and I, His-BAP1 and MBP-ASXM2 mutants were subjected as done in Figs. 6–8 to GST-ubiquitin pulldown assay (H) and in vitro DUB assay using nucleosomal H2A (I). The reactions were analyzed by immunoblotting. YY1 is used as a loading control. The dot indicates a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (D and E) (31).

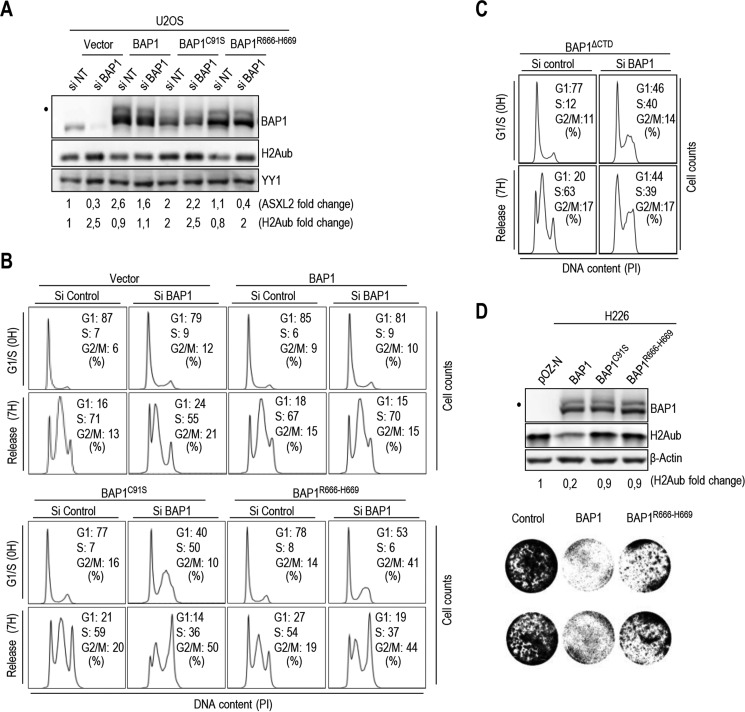

BAP1/ASXL1/2 Axis Is Required for Proper Cell Cycle Progression

We inquired to determine the biological significance of BAP1/ASXL1/2 interactions. Because BAP1 knockdown delays cell proliferation in multiple cell types (22, 23, 57), we sought to determine whether ASXL1/2 and BAP1 interactions influence cell cycle progression. We generated U2OS cells stably expressing comparable levels of siRNA-resistant BAP1, BAP1C91S or BAP1R666-H669 (Fig. 10A), and we conducted RNAi depletion of endogenous BAP1. Cells were then synchronized in early S phase using double thymidine block and released in the cell cycle. As expected, in the empty vector cells, depletion of endogenous BAP1 delayed S phase progression. Although re-expression of BAP1 rescued the defect induced by knockdown of endogenous BAP1, this was not observed with BAP1C91S nor BAP1R666-H669 (Fig. 10B). In addition, expression of BAP1C91S or BAP1R666-H669 significantly affected the ability of U2OS cells to be synchronized (Fig. 10B). Similar cell cycle defects were also observed following expression of BAP1 lacking CTD, BAP1ΔCTD (Fig. 10C). The increase of H2Aub levels following knockdown of BAP1 was prevented by re-expression of wild type BAP1 but not by BAP1R666-H669 or BAP1C91S mutants (Fig. 10A). We note that the higher levels of H2Aub in U2OS expressing BAP1C91S might result from a dominant negative effect on endogenous BAP1. Next, re-introduction of BAP1, but not the BAP1R666-H669 nor the BAP1C91S in the BAP1-deficient lung carcinoma cell line H226, promoted substantial H2A deubiquitination (Fig. 10D, top panel). In addition, unlike the wild type BAP1, which strongly inhibited cell proliferation as observed previously (21), the BAP1R666-H669 mutant only partially inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. 10D, bottom panel). Thus, physical interaction between ASXL1/2 and BAP1 and DUB activity are required for proper coordination of cell cycle progression.

FIGURE 10.

BAP1 regulates cell cycle progression in CTD-dependent manner. A, protein levels following depletion of endogenous BAP1 using siRNA in U2OS cells stably expressing siRNA-resistant BAP1, BAP1C91S, or BAP1R666-H669. B and C, mutations of CTD disrupts BAP1 function in regulating cell proliferation. Following siRNA for endogenous BAP1, U2OS cells stably expressing siRNA-resistant BAP1, BAP1C91S, BAP1R666-H669 or BAP1ΔCTD were synchronized by double thymidine block at the G1/S boundary and released 7 h to progress through S phase and were then subjected to FACS analysis. D, H226 BAP1-null cells stably expressing BAP1, BAP1C91S, or BAP1R666-H669 was analyzed by immunoblotting (top panel). Similar numbers of cells were plated and cultured for 5 days prior staining with crystal violet dye (bottom panel). YY1 and β-actin were used as a protein loading controls. The dot indicates a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (A and D) (31).

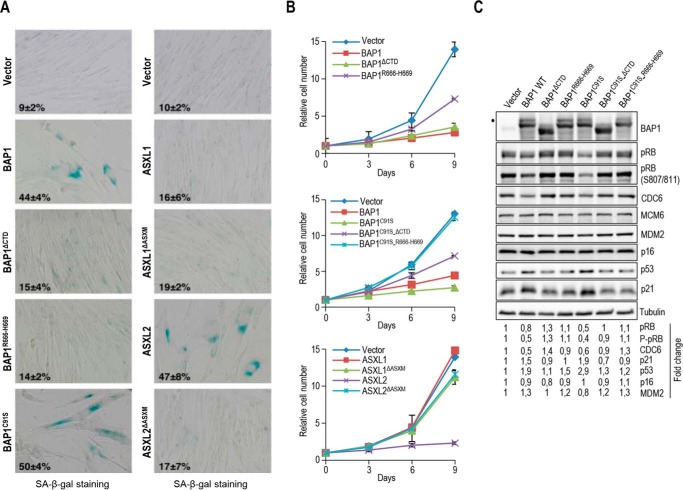

Enforced Expression of BAP1 or ASXL2 Induce Cellular Senescence and the p53/p21 Tumor Suppressor Pathway in CTD/ASXM-dependent Manner

Cellular senescence-associated cell cycle exit is a potent tumor suppressor mechanism. Because we established that BAP1 function is coordinated with ASXL1 and ASXL2 in regulating cell cycle progression, we were prompted to determine whether BAP1/ASXL1/2 might influence cellular senescence. Of note, PcG proteins, notably BMI1, are known to be involved in senescence (58–60). Therefore, we evaluated whether enforced expression of BAP1 triggers senescence in the normal diploid human fibroblasts IMR90 cell line model. Strikingly, retroviral overexpression of BAP1 reduced cell proliferation and induced senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity (Fig. 11A and B). Interestingly, overexpression of the BAP1C91S mutant also induced senescence with a more pronounced effect than the wild type form (Fig. 11, A and B). To probe whether this effect is due to the ability of BAP1 to interact with ASXL1/2, we evaluated the effect of BAP1ΔCTD and BAP1R666-H669 on cellular senescence. Indeed, these mutations significantly reduced the ability of BAP1 to induce senescence (Fig 11, A and B). Similar effects were observed for the double mutants BAP1C91S-ΔCTD, although a complete rescue was observed for BAP1C91S-R666-H669 (Fig. 11, A and B). In addition, overexpression of ASXL2, but not ASXL1, also strongly induced senescence and reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 11, A and B). Moreover, deletion of ASXM (ASXL2ΔASXM) inhibited the senescence-inducing ability of ASXL2, indicating the importance of ASXL2-BAP1 interaction in coordinating cellular senescence. To provide further insights into the molecular mechanism that orchestrate BAP1/ASXL2-mediated senescence, we evaluated the expression levels of known proteins that induce cellular senescence upon overexpression of BAP1, BAP1C91S, and corresponding mutants (Fig. 11C). We found that although the effect of BAP1 was less pronounced than the BAP1C91S form, overexpression of this DUB induced the p53/p21 tumor suppressor pathway. Overexpression of BAP1ΔCTD, BAP1R666-H669, BAP1C91S-ΔCTD, or BAP1C91S-R666-H669 did not up-regulate p53/p21 indicating the requirement for ASXL1/2 in BAP1-mediated senescence (Fig. 11C). We also observed a concomitant decrease of CDC6 and pRB following overexpression of BAP1 or BAP1C91S, and these effects required interaction with ASXL1/2. In contrast, no significant changes were observed on p16INK4a cell cycle inhibitor and the p53 E3 ligase MDM2. Altogether, these results indicate that the fine balance between ASXL1/2 complexes and their coordination of BAP1 DUB activity are required for the proper progression of cell cycle and tumor suppression.

FIGURE 11.

ASXL2 and BAP1 overexpression induces senescence in an ASXM- and CTD-dependent manner respectively. A, IMR90 cells were infected using retroviral expression vectors for BAP1, ASXL1, ASXL2, and their respective mutant forms. Eight days post-selection, the cells were fixed for staining of senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay (SA-β-gal). B, cells were also transduced with retroviral expression vectors for BAP1, ASXL1, ASXL2, and their respective mutant forms and counted every 3 days after selection to follow cell proliferation. 100 cells were counted in triplicate and data are presented as percentage of positive cells, average ± S.D. C, BAP1 overexpression triggers cellular senescence and induces the p53/p21 DNA damage response in an ASXL1/2-dependent manner. Eight days post-selection, the senescent cells were harvested for immunoblotting. Quantification of band intensity was conducted relative to the empty vector transduced cells. Tubulin was used as a protein loading controls. The dot indicates a monoubiquitinated form of BAP1 (C) (31).

Discussion

We provided novel insights into the mechanisms by which the DUB activity and function of the tumor suppressor BAP1 are coordinated. First, we revealed that BAP1 and ASXL1/2 protein levels are tightly regulated by each other. Notably, BAP1 protein levels are nearly completely reduced following concomitant depletion of ASXL1 and ASXL2. This regulation is highly conserved because, in Drosophila, deletion of ASX also destabilized dBAP1/Calypso (32). The fact that relatively similar protein amounts of ASXL1 and ASXL2 co-purified with mammalian BAP1 and that siRNA depletion of either ASXL1 or ASXL2 reduced BAP1 protein levels by approximately half, it is likely that BAP1-ASXL1 and BAP1-ASXL2 complexes coexist in the cells with a similar abundance. These complexes might exert distinct functions and/or compete for gene regulatory regions. We also found that depletion or loss of BAP1 destabilized ASXL2 but not ASXL1. These findings demonstrate for the first time the importance of complex assembly in maintaining proper protein levels of ASXL2, and hence its function in vivo. Thus, developmental or disease-associated inactivation or loss of expression of one component would result in a profound functional impact on the other partners. Indeed, loss of BAP1 in two tumor types of different histological origins, i.e. mesothelioma and non-small lung carcinoma, caused a severe reduction of ASXL2 protein levels. A survey of mutations in several cancers shows truncating mutations and deletions of BAP1 that would often result in the loss of the CTD and consequently ASXL1/2 interaction. Therefore, loss of ASXL2 function is a prevalent event in cancers with BAP1 mutations.

Similar to other post-translational modifications, ubiquitin recognition plays important roles in ubiquitin-dependent signaling (9). Often, UBDs involve distinct protein domains that engage interactions with the hydrophobic patches or other surfaces of ubiquitin and act as signal readers (9). Our study revealed that the CTD domain of BAP1 plays a central role in coordinating ubiquitin binding and catalysis by BAP1-ASXL1/2 complexes. First, the CTD is sufficient for binding an RQDR charged patch of ubiquitin and can be qualified as a bona fide UBD. Second, the CTD interacts with the CC1 and the UCH domains (31) and acts to stabilize the interaction of the ubiquitin with the catalytic domain. Third, the CTD also strongly interacts with the ASXM domain, and the latter induces ubiquitin binding by the CUBI and is required for catalysis. We also found that ASXM itself weakly binds ubiquitin and therefore would probably participate in ubiquitin positioning. Thus, our data support a model whereby UCH, CC1, CTD, and ASXM domains cooperate to generate an interface for stable binding with multiple ubiquitin patches, thus facilitating recruitment and specific substrate deubiquitination (Fig. 12). In support of our findings on BAP1/ASXL1/2, recent crystallography and molecular studies characterized the mechanism of activation of UCH37 by RPN13 (55, 56). The most remarkable similarities with BAP1 are the conserved intramolecular interaction between the DEUBAD of RPN13 and the ULD of UCH37 and the stimulatory effect of RPN13 at the level of substrate binding. Moreover, highly conserved amino acid residues in BAP1 and UCH37 are required for the interaction with the hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin. Finally, similar to ASXM, the DEUBAD of RPN13 also establishes a weak interaction with ubiquitin (55, 56). Thus, BAP1 and UCH37 share a highly conserved mechanism of cofactor-mediated DUB activation. Interestingly, INO80 chromatin remodeling factor also possesses a DEUBAD, and through molecular mimicry, this domain associates with and inhibits UCH37 (55, 56). Of note, BAP1 also interacts with INO80 ATPase, a component of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex, and promotes its deubiquitination (29). As INO80G (NFRKB) subunit of the complex inhibits UCHL5 through its DEUBAD, it will be interesting to determine whether, in specific contexts, this factor could also negatively regulate the DUB activity of BAP1.

FIGURE 12.

Model for the regulation of BAP1-mediated deubiquitination by ASXL1/2. An intramolecular interaction involving UCH/CC1 and CTD domains of BAP1 creates an ASXM-inducible CUBI that facilitates ubiquitin binding and catalysis. The red asterisks indicate cancer-associated mutations of BAP1 or ASXM that disrupt the CUBI.

Our protein complex purification studies indicated that deletion of BAP1 HBM domain does not interfere with BAP1 interaction with ASXL1/2. Conversely, mutation in CTD does not impact the interaction of BAP1 with HCF-1/OGT. Moreover, BAP1 complexes lacking HCF-1/OGT are competent in deubiquitinating nucleosomal histone H2A indicating that these components do not directly participate in ubiquitin binding and catalysis. Taking into account that dBAP1/Calypso does not possess the middle region, which was acquired later in vertebrate evolution (32), HCF1/OGT and ASXL1/2 appear to define two functional axes of the BAP1 complexes. Notably, HCF-1 recruits chromatin-modifying complexes, including MLL family of histone H3K4 methyltransferases, and Sin3-HDAC deacetylase complexes at gene regulatory regions (61, 62). Thus, HCF1/OGT and ASXL1/2 exert distinct, but likely concerted, functions tethered by BAP1. Indeed, similar to HCF-1 interactions with BAP1 (22), ASXL1/2 association with this DUB also regulates cell proliferation.

To establish the significance of BAP1-ASXL1/2 complexes for tumor suppression, we conducted RNAi rescue studies and showed that cancer-derived mutations that directly target BAP1/ASXL1/2 interaction result in a loss of DUB activity, increased H2Aub levels, and deregulation of cell cycle progression. In addition, mutations that directly target the BAP1 catalytic site are frequently found in cancer (11, 13, 20), and these mutations also result in increased H2Aub levels and deregulation of cell cycle control. These findings highlight the importance of the catalytic activity of BAP1-ASXL1/2 complexes for tumor suppression. Interestingly, overexpression of BAP1 or its catalytically dead form in primary human fibroblasts induced cellular senescence and up-regulation of the p53/p21 DNA damage response in a CTD-dependent manner, although more pronounced effects were observed for the catalytic inactive form of BAP1. It is currently unclear how both catalytically competent and inactive BAP1 promote cellular senescence. Nonetheless, as the catalytic dead BAP1 binds ubiquitin, it is possible that these effects are associated mostly with BAP1/ASXL1/2 binding to H2Aub rather than catalysis. Deregulation of H2Aub levels or its recognition might cause defects in transcriptional events (26), DNA double strand break repair (24), or replication fork progression (29), all of which could promote the induction of DNA damage and the p53 response and lead to genomic instability and cancer development. Although further studies are needed to address these possibilities, our findings nonetheless suggest that the proper balance of BAP1-ASXL1/2 complexes and their coordinated binding to ubiquitinated substrates and/or DUB activity are essential for normal control of cell proliferation. Another interesting finding is that overexpression of ASXL2, but not ASXL1, induces senescence in an ASXM-dependent manner. Taking into account that ASXL2 and BAP1 form an obligate complex, our study delineates that ASXL2 plays an important role in regulating BAP1 function in cell proliferation. Moreover, a cancer-derived mutation of BAP1 that abolishes its interaction with ASXL1/2 prevents cellular senescence, further supporting the notion that the BAP1/ASXL2 signaling axis is important for tumor suppression.

Although we cannot exclude that the BAP1/ASXL1/2 target other known substrates such HCF-1 and OGT (19, 23), our study and others provide strong support for the role of this DUB in the regulation of H2Aub levels and tumor suppression. Indeed (i) BAP1 was revealed as a major DUB for H2A in mammalian cells; (ii) several cancer mutations of BAP1 and ASXL2 target the UCH/CC1/CTD/ASXM platform, which is critical for ubiquitin binding and H2A deubiquitination, (iii) BAP1 null cancer cells display high H2Aub levels that could be reduced following reintroduction of BAP1, but not ASXL1/2 interaction-deficient mutants, (iv) both PcG proteins Ring1B and BMI1, two critical components of the PRC1 complex that catalyze H2A ubiquitination, regulate cell proliferation and are overexpressed in cancer (63–65). Thus, our study provides further insights into the potential involvement of H2Aub in tumorigenesis.

Author Contributions

S. D., I. H. M., and E. B. A. designed the study. S. D., I. H. M., and E. B. A. wrote the paper. S. D. and I. H. M. performed and analyzed the data presented in Figs. 1–5 and 10. S. D. conducted the experiments related to Figs. 8 and 9. S. D. and N. M. performed the experiments of Figs. 6 and 7. N. M. realized the experiments of Fig. 5, A and F. H. B. and N. M. performed the alignment analysis presented in Figs. 6C and 8A, respectively. H. B. conducted the experiments related to Figs. 5D and 8C. J. G. conducted the experiments of Figs. 1E and 2H. S. D., F. A. M., A. M., J. G., and N. V. G. I. designed and performed the experiments related to Fig. 11. H. P. realized the experiment of Fig. 3B. H. Y. performed the experiment of Fig. 2F. N. S. N. helped with the construction of mammalian expression vectors for ASXL1, ASXL2, ASXL1 ΔASXM, and ASXL2 ΔASXM. S. D. and N. M. designed and generated the expression vectors of the different mutant forms of BAP1, ASXM2, and ubiquitin used for the experiments related to Figs. 6–9. H. W., E. M., and M. C. provided reagents, suggested ideas for designing experiments, and analyzed the data. All the authors reviewed and interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yang Shi for support, Haider Dar, Sarah Hadj-Mimoune, Diana Adjaoud, and Marie-Anne Germain for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP-115132, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant 355814-2010 (to E.B.A.), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP-133442 (to F. A. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- DUB

- deubiquitinase

- H2Aub

- H2A Lys-119 ubiquitination

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- CUBI

- composite ubiquitin-binding interface

- UCH

- ubiquitin carboxyl hydrolase

- CC1

- coiled coil motif 1

- CC2

- coiled coil motif 2

- ULD

- C-terminal domain of UCH37

- UBD

- ubiquitin binding domain

- PcG

- Polycomb group proteins

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- aa

- amino acid

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- OGT

- O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase

- HBM

- HCF-1-binding motif.

References

- 1.MacGurn J. A., Hsu P. C., and Emr S. D. (2012) Ubiquitin and membrane protein turnover: from cradle to grave. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 231–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama K. I., and Nakayama K. (2006) Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 369–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komander D., and Rape M. (2012) The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond-Martel I., Yu H., and Affar el B. (2012) Roles of ubiquitin signaling in transcription regulation. Cell. Signal. 24, 410–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson S. P., and Durocher D. (2013) Regulation of DNA damage responses by ubiquitin and SUMO. Mol. Cell 49, 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger M. B., Hristova V. A., and Weissman A. M. (2012) HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 125, 531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., and Wilkinson K. D. (2009) Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eletr Z. M., and Wilkinson K. D. (2014) Regulation of proteolysis by human deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 114–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husnjak K., and Dikic I. (2012) Ubiquitin-binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 291–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murali R., Wiesner T., and Scolyer R. A. (2013) Tumours associated with BAP1 mutations. Pathology 45, 116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbone M., Yang H., Pass H. I., Krausz T., Testa J. R., and Gaudino G. (2013) BAP1 and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 153–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen D. E., Proctor M., Marquis S. T., Gardner H. P., Ha S. I., Chodosh L. A., Ishov A. M., Tommerup N., Vissing H., Sekido Y., Minna J., Borodovsky A., Schultz D. C., Wilkinson K. D., Maul G. G., Barlev N., Berger S. L., Prendergast G. C., and Rauscher F. J. 3rd. (1998) BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene 16, 1097–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbour J. W., Onken M. D., Roberson E. D., Duan S., Cao L., Worley L. A., Council M. L., Matatall K. A., Helms C., and Bowcock A. M. (2010) Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science 330, 1410–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel-Rahman M. H., Pilarski R., Cebulla C. M., Massengill J. B., Christopher B. N., Boru G., Hovland P., and Davidorf F. H. (2011) Germline BAP1 mutation predisposes to uveal melanoma, lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, and other cancers. J. Med. Genet. 48, 856–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bott M., Brevet M., Taylor B. S., Shimizu S., Ito T., Wang L., Creaney J., Lake R. A., Zakowski M. F., Reva B., Sander C., Delsite R., Powell S., Zhou Q., Shen R., Olshen A., Rusch V., and Ladanyi M. (2011) The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat. Genet. 43, 668–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein A. M. (2011) Germline BAP1 mutations and tumor susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 43, 925–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Testa J. R., Cheung M., Pei J., Below J. E., Tan Y., Sementino E., Cox N. J., Dogan A. U., Pass H. I., Trusa S., Hesdorffer M., Nasu M., Powers A., Rivera Z., Comertpay S., Tanji M., Gaudino G., Yang H., and Carbone M. (2011) Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat. Genet. 43, 1022–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiesner T., Obenauf A. C., Murali R., Fried I., Griewank K. G., Ulz P., Windpassinger C., Wackernagel W., Loy S., Wolf I., Viale A., Lash A. E., Pirun M., Socci N. D., Rütten A., Palmedo G., Abramson D., Offit K., Ott A., Becker J. C., Cerroni L., Kutzner H., Bastian B. C., and Speicher M. R. (2011) Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat. Genet. 43, 1018–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dey A., Seshasayee D., Noubade R., French D. M., Liu J., Chaurushiya M. S., Kirkpatrick D. S., Pham V. C., Lill J. R., Bakalarski C. E., Wu J., Phu L., Katavolos P., LaFave L. M., Abdel-Wahab O., Modrusan Z., Seshagiri S., Dong K., Lin Z., Balazs M., Suriben R., Newton K., Hymowitz S., Garcia-Manero G., Martin F., Levine R. L., and Dixit V. M. (2012) Loss of the tumor suppressor BAP1 causes myeloid transformation. Science 337, 1541–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pena-Llopis S., Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S., Liao A., Leng N., Pavia-Jimenez A., Wang S., Yamasaki T., Zhrebker L., Sivanand S., Spence P., Kinch L., Hambuch T., Jain S., Lotan Y., Margulis V., Sagalowsky A. I., Summerour P. B., Kabbani W., Wong S. W., Grishin N., Laurent M., Xie X. J., Haudenschild C. D., Ross M. T., Bentley D. R., Kapur P., and Brugarolas J. (2012) BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 44, 751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]