Background: The dopamine transporter establishes synaptic transmitter levels and strength of dopamine neurotransmission.

Results: Reciprocal modification of specific DAT phosphorylation and palmitoylation sites dictates steady-state and regulated transport capacity in the absence of trafficking.

Conclusion: The balance between phosphorylation and palmitoylation controls DA transport kinetics.

Significance: This is a previously unknown mode of transporter regulation that may be a point of dysregulation in dopamine imbalance disorders.

Keywords: post-translational modification (PTM), protein acylation, protein kinase C (PKC), protein palmitoylation, protein phosphorylation, DHHC, acyl protein transferases

Abstract

The dopamine transporter is a neuronal protein that drives the presynaptic reuptake of dopamine (DA) and is the major determinant of transmitter availability in the brain. Dopamine transporter function is regulated by protein kinase C (PKC) and other signaling pathways through mechanisms that are complex and poorly understood. Here we investigate the role of Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation in mediating steady-state transport kinetics and PKC-stimulated transport down-regulation. Using both mutational and pharmacological approaches, we demonstrate that these post-translational modifications are reciprocally regulated, leading to transporter populations that display high phosphorylation-low palmitoylation or low phosphorylation-high palmitoylation. The balance between the modifications dictates transport capacity, as conditions that promote high phosphorylation or low palmitoylation reduce transport Vmax and enhance PKC-stimulated down-regulation, whereas conditions that promote low phosphorylation or high palmitoylation increase transport Vmax and suppress PKC-stimulated down-regulation. Transitions between these functional states occur when endocytosis is blocked or undetectable, indicating that the modifications kinetically regulate the velocity of surface transporters. These findings reveal a novel mechanism for control of DA reuptake that may represent a point of dysregulation in DA imbalance disorders.

Introduction

The dopamine transporter (DAT)4 is a plasma membrane protein that actively transports extracellular dopamine (DA) into presynaptic dopaminergic neurons after transmitter release. Reuptake is the primary mechanism for DA clearance in the brain and controls the spatial and temporal availability of transmitter during neurotransmission (1). DAT is a target for addictive and therapeutic drugs that inhibit uptake or stimulate transmitter efflux and induce effects by increasing extracellular DA levels (2). Transport activity is tightly controlled by many signaling pathways that modulate reuptake in response to specific physiological demands (3–5), and dysregulation of these processes has been postulated to contribute to aberrant transmitter clearance in DA imbalance disorders such as Parkinson disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (4–7).

Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) has been well characterized to reduce DA transport Vmax and stimulate dynamin- and clathrin-dependent DAT endocytosis (5, 8, 9). Most studies to date have focused on membrane trafficking as the mechanism underlying PKC-induced transport reductions (10–14), but recent findings have shown that significant levels of down-regulation are retained when transporter endocytosis is blocked or impaired (15–17), indicating the presence of a kinetic regulatory mechanism that operates in concert with internalization.

The cytoplasmic domains of DAT contain sites for post-translational modifications that regulate various aspects of its functions (4, 5, 18). DAT undergoes PKC- and protein phosphatase 1-dependent phosphorylation on Ser-7 and other serines near the distal end of the N terminus (19, 20). These residues are not necessary for PKC-stimulated endocytosis of the transporter (21, 22), but their role in kinetic regulation of uptake has not yet been investigated. DAT is also palmitoylated on Cys-580 at the membrane-cytoplasm interface of the most C-terminal transmembrane helix (17). Acute inhibition of transporter palmitoylation enhances PKC-stimulated down-regulation and induces significant trafficking-independent decreases in transport Vmax (17), also suggesting a role for this modification in catalytic regulation of transport.

Here we investigate the relationship between Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation of DAT in steady-state transport kinetics and PKC-stimulated down-regulation, finding that these modifications are reciprocally regulated and induce opposing effects on Vmax and PKC responsiveness. The functional differences are driven by a trafficking-independent process in which reduced transport correlates with Ser-7 phosphorylation and increased transport correlates with Cys-580 palmitoylation. This demonstrates a previously unknown mechanism for control of DAT function and suggests the potential for these modifications to represent sites of dysregulation in DA imbalance disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

[7,8-3H]DA (45 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences; [9,10-3H]palmitic acid (73.4 Ci/mmol) was from Moravek; H332PO4 was from MP Biomedicals; Fluoro-Hance fluorographic reagent was from Research Products International; DA was from Research Biochemicals International; phorbol 12-myristate,13-acetate (PMA), oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), and okadaic acid (OA) were from EMD Millipore; DAT polyclonal antibody 16 (poly16) and monoclonal antibody 16 (mAb 16) were as previously described (23, 24); polyclonal antibodies for Rab5A, Rab7, and Na+/K+ ATPase were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; those for Rab11 were from BD Biosciences, and for HA were from Covance; X-tremeGENE HP transfection reagent was from Roche Applied Bioscience; methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS), HPDP biotin (sulfhydryl-reactive (N-(6-(biotinamido)hexyl)-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)-propionamide), sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, highcapacity NeutrAvidin-agarose resin, protease inhibitor tablets, and bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent were from Thermo Scientific; PitStop2® was from Abcam Biochemicals; (−)-cocaine and other fine chemicals were from Sigma. Rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All animals were housed and treated in accordance with regulations established by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the University of North Dakota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DAT Phosphorylation

For experiments in heterologously expressing cells, LLCPK1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant rat DATs (rDATs) were cultured and analyzed for phosphorylation as previously described (22). For DHHC experiments, cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids 24 h before the start of the experiment. Plasmids encoding HA-tagged DHHC2 and GST were the generous gift of Dr. Masaki Fukata, National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Japan. DHHA2 negative control with residue Cys-156 changed to alanine to create an inactive protein was created from DHHC2 by site-directed mutagenesis with codon substitution verified by sequencing (Eurofins MWG), and expression of all constructs was verified by anti-HA immunoblotting (not shown). Cells were labeled with phosphate-free medium containing 0.5–1 mCi/ml 32P for 2 h at 37 °C followed by application of test compounds for the indicated times. Cells were washed, pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100. Lysates were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 2 min, and resulting supernatants were adjusted to contain 0.5% SDS and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min to remove insoluble material. DATs were immunoprecipitated with poly16 followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (19, 23). For experiments in brain tissue, rat striatal synaptosomes were prepared and labeled with 32P as previously described (25). Briefly, synaptosomes prepared in sucrose-phosphate buffer (0.32 m sucrose and 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) at 120 mg/ml original wet weight were diluted 4-fold in oxygenated Krebs bicarbonate buffer (25 mm NaHCO3, 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.5 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MgSO4, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.3) containing [32P]orthophosphate (2 mCi/ml) and 10 μm OA to suppress tonic dephosphorylation. Samples were treated with vehicle (DMSO), 10 μm 2-bromopalmitate (2BP), or 1 μm PMA and incubated at 30 °C for 45 min. Synaptosomes were then placed on ice and washed 3 times with ice-cold Krebs bicarbonate buffer by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 12 min. Final synaptosomal pellets were solubilized in 100 μl of lysis buffer (60 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 0.5 mm SDS, 10% glycerol, 100 mm DTT, and 3% β-mercaptoethanol with 4 passages through a 26-gauge needle. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 20 min, and resulting supernatants were diluted 5-fold for DAT immunoprecipitation with poly16 followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Total DAT levels in each sample were determined by immunoblotting using mAb 16 (23).

DAT Palmitoylation

[3H]Palmitate labeling was performed in rDAT-LLCPK1 cells by incubation for 6–18 h with medium containing 0.5 mCi/ml [3H]palmitate and treatment with vehicle or test compounds for an additional 60 min. The cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 125 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm sodium fluoride), and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with poly16 followed by SDS-PAGE, treatment of gels with Fluoro-Hance, and autofluorography.

Analysis of palmitoylation by acyl-biotinyl exchange (ABE) was performed as described (17). For experiments in cells, lysates were prepared as above with 20 mm MMTS added to the lysis buffer to block free thiols. For experiments using brain tissue, rat striatal slices were preincubated in oxygenated Krebs bicarbonate buffer for 30 min at 30 °C with shaking at 105 rpm followed by treatment with vehicle or 1 μm OA plus 10 μm OAG for an additional 30 min. Oxygen (95% O2, 5% CO2) was gently blown across the top of the plate during the incubation. Tissue was homogenized in ice-cold sucrose-phosphate buffer with 15 strokes in a glass/Teflon homogenizer and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 12 min. The resulting P2 synaptosomal pellet was resuspended to 50 mg/ml original wet weight in ice-cold sucrose-phosphate buffer. The synaptosomal suspension was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 12 min at 4 °C and solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 2% SDS, 1 mm EDTA) containing protease inhibitors and 20 mm MMTS. Cell and synaptosomal lysates were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h with mixing followed by acetone precipitation and resuspension in lysis buffer containing MMTS and incubation at room temperature overnight with end-over-end rotation. Excess MMTS was removed by three sequential acetone precipitations followed by resuspension of precipitated proteins in 300 μl of a buffer containing 4% (w/v) SDS (4SB: 4% SDS, 50 mm Tris, 5 mm EDTA, pH 7.4). Each sample was divided into two equal portions that were treated for 2 h at room temperature with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, as control or 0.7 m hydroxylamine (NH2OH), pH 7.4, which cleaves the thioester bonds and removes endogenous palmitate groups. NH2OH was removed by three sequential acetone precipitations followed by resuspension of the precipitated proteins in 240 μl of 4SB buffer. Samples were diluted with 900 μl of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.4 mm HPDP biotin to label the liberated sulfhydryl groups and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with end-over-end mixing. Unreacted HPDP biotin was removed by three sequential acetone precipitations followed by resuspension of the final pellet in 75 μl of lysis buffer without MMTS. Samples were adjusted to contain 0.1% SDS by the addition of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and biotinylated proteins were extracted using NeutrAvidin resin. Proteins bound to the resin were eluted with sample buffer (60 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol) containing 100 mm DTT plus 3% β-mercaptoethanol and subjected to SDS-PAGE. DAT was identified by immunoblotting using mAb 16 (23). In all experiments the level of signal intensity from Tris controls was <5% of NH2OH levels.

Immunoprecipitation, Electrophoresis, and Immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitation of 32P- or [3H] palmitate-labeled DATs was conducted for 2 h at 4 °C using protein A-Sepharose beads cross-linked with poly16 antibody (17, 19), and the precipitated samples were electrophoresed on 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film for detection of radioactivity. For immunoblotting, proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and DATs were detected with mAb 16 as previously described (23). For all experiments, palmitoylated or phosphorylated DAT band intensities were quantified by densitometry using Quantity One (Bio-Rad) software and normalized to the amount of total DAT protein in the sample, and signals for treatment groups were expressed relative to control samples set to 100%. For cell surface expression determination WT or mutant rDAT-LLCPK1 cells were incubated with the membrane-impermeable biotinylating reagent sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, and biotinylated DATs were purified from cell lysates (25 μg of protein) by chromatography on NeutrAvidin beads, separated by SDS-PAGE, and quantified by immunoblotting (16). All experiments were performed a minimum of three times with similar results, and values were analyzed for statistical significance using Student's t test or one way ANOVA as indicated.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

S7A, C522A, and C580A DAT mutants used in this study were characterized previously (17, 20). S7A/C580A DAT was produced from a pcDNA 3.0 plasmid containing the DAT C580A cDNA sequence using the Stratagene QuikChange® kit with codon substitution verified by sequencing (Eurofins MWG). For production of stable transformants, LLCPK1 cells were transfected using X-tremeGENE transfection reagent and 0.5 μg of the mutant plasmid. Transformants were selected 24–48 h later by the addition of 800 μg/ml Geneticin (G418) to the cell culture medium. All mutants were active for [3H]DA transport, expressed at 30–50% that of the WT protein level, and showed ratios of total to cell surface expression that were comparable with that of the WT protein.

[3H]DA Uptake

WT or mutant rDAT-LLCPK1 cells were grown in 24-well plates to ∼80% confluence and rinsed twice with 0.5 ml of 37 °C Krebs-Ringer/HEPES buffer (KRH: 25 mm HEPES, 125 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.3 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 5.6 mm glucose, pH 7.4). Where indicated cells were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with vehicle or 1 μm PMA or with 250 μg/ml concanavalin A (ConA) for 30 min before the addition of PMA. Uptake was performed in triplicate for 8 min, with nonspecific uptake determined with 100 μm (−)-cocaine. For single point assays uptake was initiated by the addition of 10 nm [3H]DA plus 3 μm DA. For saturation analyses DA was varied from 1 to 30 μm. Cells were rapidly washed 2 times with ice-cold Krebs-Ringer/HEPES buffer and solubilized in 1% Triton X-100, and radioactivity contained in lysates was assessed by liquid scintillation counting. Kinetic values were analyzed by Prism, and Vmax values for each form were normalized to surface expression transporter levels determined in parallel for each experiment.

Subcellular Localization of Phosphorylated and Palmitoylated DATs

Subcellular fractions were generated by differential centrifugation as described (26). LLCPK1 cells stably expressing WT rDAT were cultured in 150-mm dishes, grown to ∼90% confluence, labeled with 32P when indicated, and treated with vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min. Cells were washed, scraped, and pelleted by centrifugation at 700 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pelleted cells were resuspended in Buffer C (0.25 m sucrose, 10 mm triethanolamine, 10 mm acetic acid, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.8) and homogenized in ice-cold Buffer C with 30 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 700 × g to remove nuclei, and post-nuclear supernatants (totals) were centrifuged sequentially at 16,000 × g for 12 min (16,000 × g membranes) and at 200,000 × g for 1 h (200,000 × g membranes). Resulting pellets were resuspended at the original volume in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. Fractions were immunoblotted for DAT, Na+/K+ ATPase, Rab5A, Rab7, and Rab11 or analyzed by ABE for detection of DAT palmitoylation. 32P-Labeled fractions were immunoprecipitated with poly16 followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography for detection of DAT phosphorylation.

Results

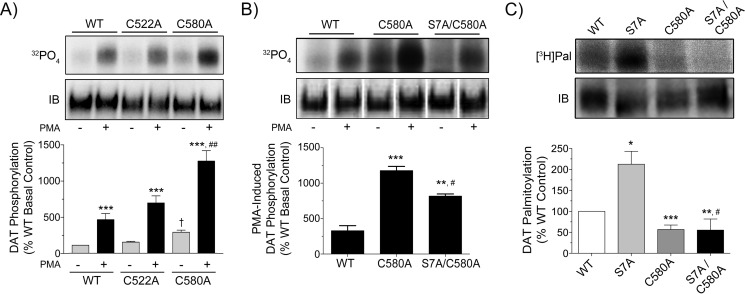

C580A DAT Displays Enhanced Phosphorylation on Ser-7

To determine if phosphorylation of DAT is affected by its level of palmitoylation, we examined the 32P labeling of C580A DAT, which shows an ∼50% reduction in palmitoylation, and C522A DAT, which shows no reduction in palmitoylation (17) as a specificity control. LLCPK1 cells expressing WT, C522A, or C580A DATs were labeled with 32P and treated with vehicle or PMA to activate PKC, and equal amounts of DAT were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography (Fig. 1A). WT DAT displayed typical levels of basal and stimulated phosphorylation, with PMA inducing increases to 420 ± 77% of basal (p < 0.001). C522A DAT showed the same pattern and intensity of labeling, indicating no effect of this residue on phosphorylation. In contrast, 32P labeling of C580A DAT was enhanced in both basal (263 ± 25% of WT basal, p < 0.05) and PMA-stimulated conditions (1154 ± 129% of WT basal, p < 0.001 versus C580A basal; p < 0.01 versus WT PMA), indicating that lack of palmitoylation on Cys-580 results in elevated basal and stimulated phosphorylation.

FIGURE 1.

Reciprocal phosphorylation and palmitoylation of DAT induced by mutagenesis. A and B, LLCPK1 cells expressing the indicated DAT forms were labeled in parallel with 32P and treated with vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min. Equal amounts of DAT determined by immunoblotting (IB) were immunoprecipitated and subjected to SDS-PAGE/autoradiography. Upper panels show representative autoradiograms and matching immunoblots. Histograms show quantification of 32P labeling (% WT basal, mean ± S.E.). A, ***, p < 0.001 PMA versus basal for indicated DAT forms; †, p < 0.05 C580A basal versus WT basal; ##, p < 0.01, C580A PMA versus WT PMA; n = 3–9. B, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 PMA for indicated forms versus WT PMA; #, p < 0.05, S7A/C580A PMA versus C580A PMA. n = 6 (WT), 6 (C580A), 3 (S7A/C580A). The vertical white dividing lines in the immunoblot in panel B indicate the removal of duplicate sample lanes. C, rDAT-LLCPK1 cells expressing the indicated DAT forms were labeled in parallel with [3H]palmitate. Equal amounts of DAT (IB) were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autofluorography. The upper panels show representative autoradiograms and matching immunoblots. The histogram shows quantification of [3H]palmitate labeling (% WT, mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 indicate forms versus WT; #, p < 0.05, S7A/C580A versus S7A. n = 9 (WT), 9 (S7A), 5 (C580A), 3 (S7A/C580A). Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test.

32P labeling of DAT reflects modification of all phosphorylation sites, including those in the distal PKC domain and in a membrane proximal proline-directed site (19, 20, 22, 27). Multiple serines in the distal N terminus are phosphorylated, but to date only Ser-7 has been identified as PKC-dependent (20). We thus generated the double mutant S7A/C580A as an initial approach to identify the site of enhanced phosphorylation on C580A DAT (Fig. 1B). Labeling of WT, C580A, and S7A/C580A forms in parallel with 32P shows PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of WT DAT (329 ± 72% of basal) and enhanced PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of C580A DAT (1178 ± 60% of WT basal; p < 0.001 versus WT PMA). PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of S7A/C580A DAT (818 ± 31% of WT basal) was significantly lower than the C580A PMA value (p < 0.05), indicating that a major fraction of the increased phosphorylation of C580A DAT occurred on Ser-7. Phosphorylation of S7A/C580A DAT remained elevated compared with the WT protein, however (p < 0.01 versus WT PMA), indicating that loss of Cys-580 palmitoylation leads to enhanced phosphorylation of other residues as well.

S7A DAT Displays Enhanced Palmitoylation on Cys-580

We then performed the reverse experiment to determine if Cys-580 palmitoylation is affected by Ser-7 phosphorylation. LLCPK1 cells expressing WT, S7A, C580A, or S7A/C580A rDATs were labeled with [3H]palmitate, and equal amounts of DAT were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/fluorography (Fig. 1C). WT DAT displayed a tonic level of [3H]palmitate labeling that reflects steady-state palmitate turnover, whereas S7A DAT, which shows ∼50% reduction in phosphorylation (20), shows strongly enhanced [3H]palmitate labeling (219 ± 34% relative to WT; p < 0.05). Parallel analysis of C580A and S7A/C580A DATs to investigate the site of increased palmitoylation showed that C580A DAT labeling was reduced to about half the WT level (57 ± 10% of WT; p < 0.001), consistent with our previous findings (17). Palmitoylation of S7A/C580A DAT was similarly reduced relative to the WT protein (55 ± 26% of WT; p < 0.01) and was significantly reduced relative to S7A DAT (p < 0.05 versus S7A), indicating that the enhanced palmitoylation seen on S7A DAT occurred on Cys-580.

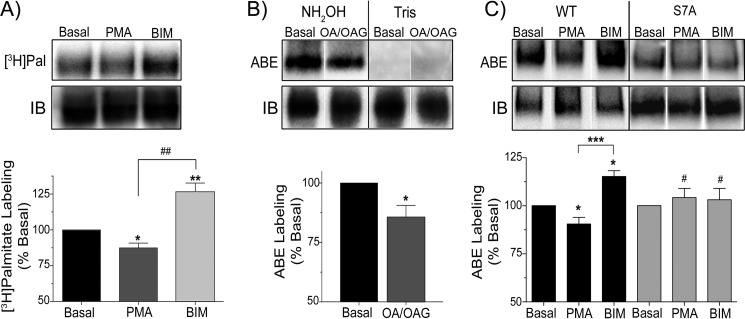

DAT Palmitoylation Is Regulated by Phosphorylation Modulators

These results demonstrate that prevention of Ser-7 phosphorylation or Cys-580 palmitoylation by mutagenesis leads to enhancement of the alternate modification. To determine if these changes are indirect effects of mutagenesis or are specific to the modifications, we then determined if similar changes would result from pharmacological modulation of the modifications in the WT protein. For analysis of rDAT palmitoylation changes in LLCPK1 cells we performed [3H]palmitate labeling in the presence of PMA, which enhances DAT phosphorylation, or the PKC inhibitor bisindoylmaleimide (BIM), which blocks PMA-stimulated DAT phosphorylation (9). [3H]Palmitate labeling of DAT was reduced 13 ± 3% by PMA (p < 0.05 versus basal) and increased 26 ± 7% by BIM (p < 0.01 versus basal; p < 0.01 versus PMA) (Fig. 2A). For analysis of responses in brain tissue we treated rat striatal slices with the PKC activator OAG plus the phosphatase inhibitor OA, which induces maximal phosphorylation of DAT in rat striatum (19). Analysis of DAT palmitoylation by ABE showed that OA/OAG induced a 15 ± 5% reduction in palmitoylation (p < 0.05 versus basal) (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that DAT palmitoylation is negatively regulated by PKC in both cells and brain tissue, suggesting this as a possible mechanism linking palmitoylation to PKC-dependent regulation of transport.

FIGURE 2.

Phosphorylation modulators regulate DAT palmitoylation via a Ser-7 dependent mechanism. A, rDAT-LLCPK1 cells were labeled for 6 h with [3H]palmitate and treated with vehicle, 1 μm PMA, or 10 μm BIM for an additional 60 min. Equal amounts of DAT were determined by immunoblotting (IB) were immunoprecipitated and subjected to SDS-PAGE/autofluorography. The upper panels show representative autoradiogram and matching immunoblots. The histogram shows quantification of [3H]palmitate labeling (% basal, mean ± S.E.), *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus basal; ##, p < 0.01 PMA versus BIM. (n = 4). B, rat striatal slices were treated with vehicle or 1 μm OA plus 10 μm OAG for 30 min, and DAT palmitoylation was assessed by ABE. The upper panels show representative ABE blots and matching total DAT immunoblots. The histogram shows quantification of DAT palmitoylation (% basal, mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05, OA/OAG versus basal. (n = 3). C, cells expressing WT or S7A DATs were treated with vehicle, 1 μm PMA, or 10 μm BIM for 60 min followed by assessment of DAT palmitoylation by ABE. The upper panels show representative NH2OH-treated ABE samples or total (IB) DAT. The histogram shows quantification of DAT palmitoylation (% basal, mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05, WT DAT, PMA, or BIM versus control; ***, p < 0.001, WT DAT, PMA versus BIM; #, p < 0.05, S7A DAT, PMA, or BIM versus WT DAT, PMA, or BIM (n = 6). Statistical analyses for A and C were performed by ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test and for B by Student's t test. Where present, vertical white dividing lines indicate the rearrangement of lane images from the same immunoblot or autoradiogram.

Because Ser-7 is a known PKC target on DAT, we examined the palmitoylation responsiveness of S7A DAT to determine if PKC regulation of palmitoylation was mediated by phosphorylation of this site or via an independent mechanism (Fig. 2C). Using ABE we found that palmitoylation of WT DAT was reduced by PMA (90 ± 3% of basal, p < 0.05) and increased by BIM (115 ± 3% of basal, p < 0.05; p < 0.001 versus PMA), consistent with the results found by [3H]palmitate labeling, whereas S7A DATs showed no alteration in palmitoylation with either PMA (101 ± 5% of control p > 0.05; p < 0.05 versus WT PMA) or BIM (103 ± 6% of control p > 0.05; p > 0.05 versus S7A PMA; p < 0.05 versus WT BIM) (Fig. 2C). This indicates that phosphorylation of Ser-7 is a prerequisite for PKC-dependent regulation of DAT palmitoylation, supporting a direct mechanistic link between these modifications.

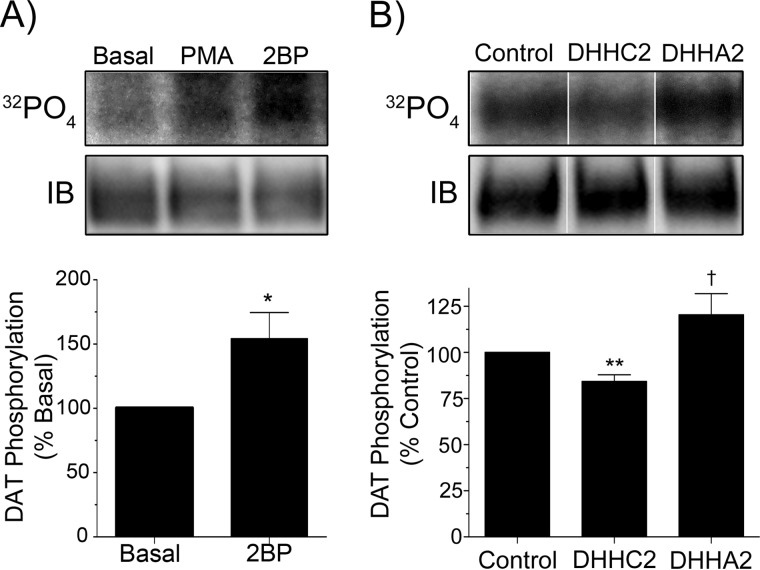

DAT Phosphorylation Is Regulated by Palmitoylation Modulators

We then sought to determine if pharmacological modulation of DAT palmitoylation would alter its phosphorylation state. Protein palmitoylation is controlled by protein acyltransferases (PATs) that catalyze palmitate addition and acyl protein thioesterases and protein palmitoyl thioesterases that catalyze palmitate removal (28), but there are few specific pharmacological activators or inhibitors available for the multiple known PATs, acyl protein thioesterases, and protein palmitoyl thioesterases. To assess the effects of reduced palmitoylation on DAT phosphorylation, we thus used the nonspecific PAT inhibitor 2BP, which rapidly reduces DAT palmitoylation in rat striatal synaptosomes by ∼50% without changing protein levels (17). Using 32P-labeled rat striatal synaptosomes, we found that acute 2BP application did not change total DAT protein but caused an increase in DAT phosphorylation (154 ± 20% of basal, p < 0.05) that was comparable to the stimulation induced in parallel samples by PMA (Fig. 3A). As 2BP has no known ability to stimulate PKC or other kinases (29), this indicates that the increased DAT phosphorylation results from acute suppression of the palmitoylation state.

FIGURE 3.

Palmitoylation modulators regulate DAT phosphorylation. A, rat striatal synaptosomes were labeled with 32P and treated with vehicle, 1 μm PMA, or 1 μm 2BP for 45 min, and equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated (IB) for DAT and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography. The upper panels show representative autoradiogram and a matching immunoblot. The histogram shows quantification of DAT 32P labeling (% basal, mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05, 2BP versus control (n = 3). B, rDAT-LLCPK1 cells transiently transfected with control (GST), DHHC2, or DHHA2 plasmids were labeled with 32P for 1 h, and DATs were immunoprecipitated and subjected to SDS-PAGE/autoradiography. The upper panels show representative autoradiogram and matching immunoblot. The vertical white dividing lines indicate the rearrangement of lane images from the same immunoblot or autoradiogram. The histogram shows quantification of DAT 32P labeling (% control ± S.E.). **, p < 0.01, DHHC2 versus control; †, p < 0.05, DHHA2 versus DHHC2 (n = 4). Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test.

To examine the effects of enhanced DAT palmitoylation on phosphorylation levels, we co-expressed rDAT-LLCPK1 cells with the PAT enzyme DHHC2, which we recently identified as one of a subset of neuronal PATs that enhance palmitoylation of DAT on Cys-580 (30). Our findings show that co-expression of DHHC2 reduced the 32P labeling of DAT to 84 ± 4% that of control (p < 0.01), whereas co-expression of DHHA2, the inactive form of the enzyme that does not increase DAT palmitoylation (30), does not affect 32P labeling (120 ± 11%; p > 0.05 versus DHHC2) (Fig. 3B). Together these results support the reciprocal regulation of DAT phosphorylation level by pharmacological modulation of Cys-580 palmitoylation in both cells and brain tissue.

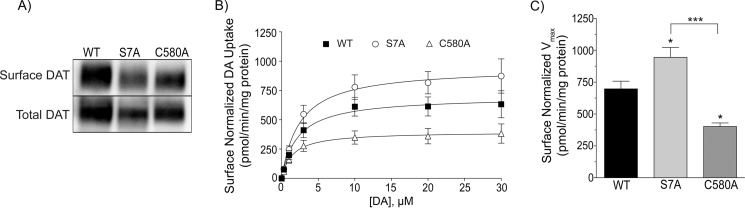

Ser-7 and Cys-580 Differentially Regulate Steady-state DA Transport Capacity

Previous studies have shown that DA transport Vmax is reduced by conditions that stimulate phosphorylation of the DAT distal N terminus (8, 9) and by inhibition of Cys-580 palmitoylation (17), suggesting that transport is decreased by phosphorylation of Ser-7 and other N-terminal serines and increased by Cys-580 palmitoylation. To further examine the role of these modifications on transport kinetics we performed [3H]DA saturation transport analyses for S7A, C580A, and WT DATs (Fig. 4). All experiments were performed in parallel and included analysis of samples for total and surface DAT expression. Relative to the WT transporter values set at 100%, total and cell surface expression of S7A DAT was 52 ± 5% and 46 ± 3%, respectively, and total and surface expression of C580A DAT was 55 ± 5% and 56 ± 4%, respectively (Fig. 4A). Fig. 4B shows uptake value averages for each form, normalized for surface expression. The Vmax of S7A DAT (945 ± 72 pmol/min/mg) was statistically greater than that of the WT protein (697 ± 56 pmol/min/mg; p < 0.05), and the C580A DAT Vmax (397 ± 34 pmol/min/mg) was significantly less than both WT and S7A DAT (p < 0.05 versus WT, p < 0.001 versus S7A) (Fig. 4C). Km values (WT DAT, 2.3 ± 0.8 μm; S7A DAT, 2.5 ± 0.8 μm; and C580A DAT, 1.5 ± 0.6 μm) were not significantly different. The order of DAT kinetic capacity, from highest to lowest, S7A > WT > C580A, is thus consistent with the Vmax of WT DAT being reduced by increases in Ser-7 phosphorylation and/or reduced Cys-580 palmitoylation and increased by enhanced Cys-580 palmitoylation and/or reduced Ser-7 phosphorylation. Using cell-surface biotinylation we found no significant substrate-induced internalization for any of the forms during the time frame of uptake (not shown), indicating that differential endocytosis during the transport assay did not contribute to these results, and the similar total and surface levels of S7A and C580A DAT forms argue against the possibility that their regulatory differences result from these factors.

FIGURE 4.

Ser-7 and Cys-580 differentially modulate DA transport Vmax. LLCPK1 cells expressing WT, S7A, and C580A DATs were analyzed in parallel for [3H]DA saturation transport kinetics, total DAT expression, and DAT cell-surface expression. A, representative immunoblots showing equal amounts of protein analyzed for DAT total and surface levels. B, [3H]DA saturation analysis normalized for relative transporter surface levels. Uptake values shown are the mean ± S.E. of five independent experiments. C, the histogram shows Vmax values for WT and mutant forms. *, p < 0.05 indicated form versus WT; ***, p < 0.001 S7A versus C580A. Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test.

Ser-7 and Cys-580 Differentially Control Kinetic Down-regulation of Transport

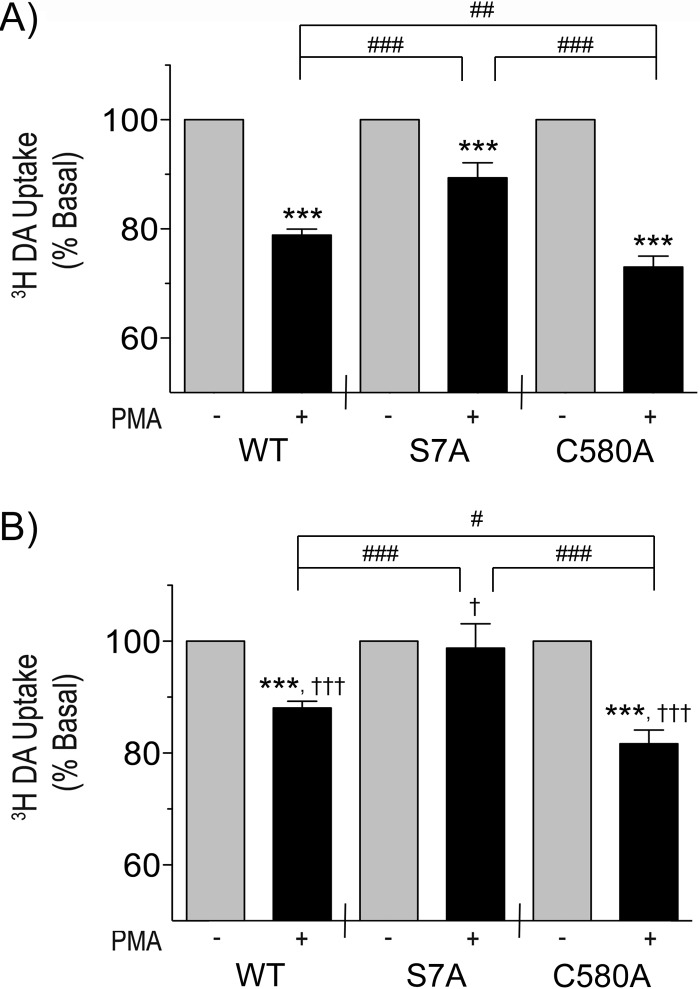

We then used WT, S7A, and C580A DATs to investigate the role of Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation in PMA-induced transport down-regulation (Fig. 5). In untreated cells, where DATs can undergo constitutive and regulated endocytosis (Fig. 5A), WT DATs showed a typical level of down-regulation (79 ± 1% of control; p < 0.001), and C580A DATs showed a statistically greater level of down-regulation (73 ± 2% of C580A control, p < 0.001; p < 0.01 versus WT PMA), consistent with our previous results (17). In contrast, S7A DATs showed less down-regulation (89 ± 3% of S7A control; p < 0.001) than either the WT (p < 0.001 versus WT PMA) or C580A forms (p < 0.001 versus C580A PMA).

FIGURE 5.

Ser-7 and Cys-580 differentially modulate kinetic down-regulation of transport. A, LLCPK1 cells expressing the indicated DAT forms were treated with vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min and assayed for [3H]DA uptake. Data are presented as % basal (mean ± S.E.) for each form. ***, p < 0.001 PMA versus basal for each form; ##, p < 0.01; ###, p < 0.001 PMA versus PMA for indicated combinations. n = 19 (WT), 7 (S7A), 15 (C580A). B, LLCPK1 cells expressing the indicated DAT forms were treated with 250 μg/ml ConA for 30 min followed by the addition of vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min and assayed for [3H]DA uptake. Data are presented as % basal (mean ± S.E.) for each form. ***, p < 0.001 PMA versus basal for indicated forms; #, p < 0.05; ###, p < 0.001 PMA versus PMA for indicated combinations; †, p < 0.05; †††, p < 0.001, PMA of indicated form in B versus PMA of corresponding form in A. n = 19 (WT), 7 (S7A), 13 (C580A). Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test.

To determine if these down-regulation differences arise from effects on endocytosis, we then examined the responses of the mutants when internalization was blocked. Several studies have shown by both surface biotinylation and confocal microscopy that stimulated internalization of DAT in heterologous expression systems and cultured neurons can be prevented with inhibitors of clathrin-mediated endocytosis including clathrin and dynamin siRNA (14, 31, 32), dynamin dominant negative suppression (16, 33), and ConA (16, 33).

For these experiments we used acute ConA to inhibit DAT endocytosis, as this treatment has no effect on the total expression, resting surface levels, or basal transport activity of DAT (33). With ConA pretreatment the magnitude of PKC-induced down-regulation for all DAT forms was significantly less than the levels observed in control cells (WT ConA versus WT control, p < 0.001; S7A ConA versus S7A control p < 0.05; C580A ConA versus C580A control, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B), consistent with reduction of down-regulation due to suppression of endocytosis. The extent of this reduction was similar for all three DAT forms, suggesting that in control conditions each of the transporters undergoes a similar level of PKC-induced endocytosis. Although further work is needed to more fully evaluate this issue, this interpretation is consistent with findings that transporter internalization does not require N-terminal phosphorylation (21) and suggests that Cys-580 palmitoylation also does not play a major role in this process.

Down-regulation of WT DAT in the presence of ConA (88 ± 1% of control, p < 0.001 versus WT basal) was about half the level seen in control conditions, which is consistent with our previous results (16) and indicates that transport reductions in control conditions occurred via relatively equal contributions from trafficking and non-trafficking processes. Strikingly, in ConA-treated cells, S7A DAT showed a complete absence of PMA-induced down-regulation (99 ± 4% of S7A basal, p > 0.05; p < 0.001 versus WT PMA; Fig. 5B), indicating that in control conditions most of its transport reduction occurred via endocytosis and that its lesser overall down-regulation was due to reduced kinetic regulation. In contrast, down-regulation of C580A DATs in ConA-treated cells (82 ± 3% of C580A basal, p < 0.001) remained greater than both WT (p < 0.05 versus WT PMA) and S7A DATs (p < 0.001 versus S7A PMA), indicating that its greater transport reduction in both control and ConA-treatment conditions was due to enhanced kinetic down-regulation. The rank order of kinetic down-regulation of these forms (C580A > WT > S7A) thus correlates positively with the level of Ser-7 phosphorylation and negatively with the level of Cys-580 palmitoylation and parallels the order of steady-state kinetics of these forms.

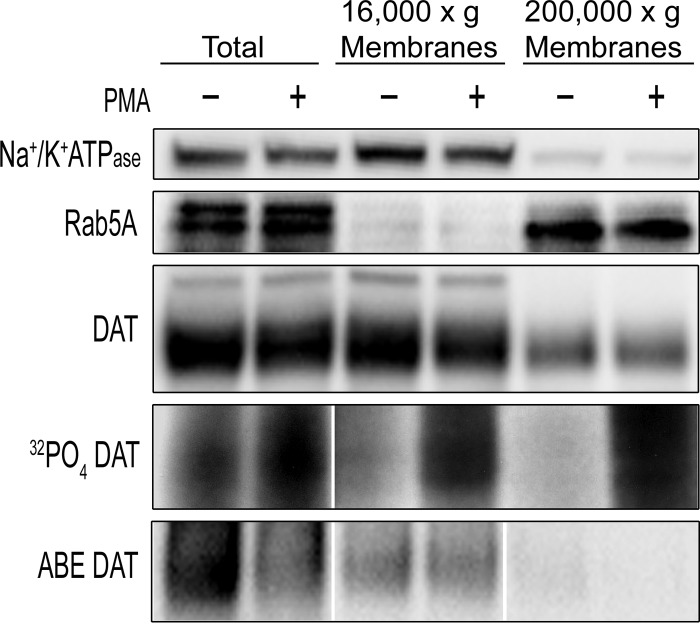

Phosphorylation and Palmitoylation Are Present on Surface Transporters

Kinetic regulation of uptake by phosphorylation and palmitoylation requires that the modifications be present on surface transporters. To investigate this, rDAT-LLCPK1 cells treated with vehicle or PMA were subjected to subcellular fractionation for analysis of DAT phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Post-nuclear supernatants were subjected to differential centrifugation to generate fractions enriched in plasma membranes (16,000 × g pellets) or endosomes (200,000 × g pellets) (26). Immunoblotting showed enrichment of the plasma membrane marker Na+/K+-ATPase in the 16,000 × g membranes and the early endosomal marker Rab5A in the 200,000 × g membranes, confirming the separation (Fig. 6). Markers for late endosomes (Rab7) and recycling endosomes (Rab11) were also enriched in the 200,000 × g membranes (not shown). Most of the DAT immunoreactivity was present in the 16,000 × g membranes (82 ± 2% of total) compared with the 200,000 × g membranes (18 ± 2% of total), consistent with numerous confocal microscopy studies showing the majority of DAT expression at the cell surface of cultured neurons and heterologously transfected cells (34–36) including rDAT-LLCPK1 cells.5 For phosphorylation analysis, cells were labeled with 32P, and DATs from each fraction were immunoprecipitated. Both basal and PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of DATs were clearly evident in the plasma membrane-enriched fraction, supporting the occurrence of regulated phosphorylation in this compartment. We also isolated 32P-labeled DATs by cell-surface biotinylation (not shown), further supporting this result. Phosphorylated transporters were also present in the endosome-enriched fraction, suggesting a possible role for this modification in additional functions. ABE analysis showed that palmitoylated transporters were highly enriched in the 16,000 × g membranes, strongly supporting the presence of phosphorylation and palmitoylation on surface transporters.

FIGURE 6.

Subcellular localization of phosphorylated and palmitoylated DATs. rDAT-LLCPK1 cells with 32P-labeling where indicated were treated with vehicle or 1 μm PMA for 30 min. Cells were homogenized, and post-nuclear supernatants (Total) were subjected to differential centrifugation to produce 16,000 × g membranes and 200,000 × g membranes. Fractions were immunoblotted for Na+/K+-ATPase, Rab5A, or DAT, immunoprecipitated for detection of DAT 32P labeling, or subjected to ABE (NH2OH-treated samples shown) for detection of DAT palmitoylation. Results are representative of three-four independent experiments performed in duplicate. Where present, vertical white dividing lines indicate the rearrangement of lane images from the same immunoblot or autoradiogram.

Discussion

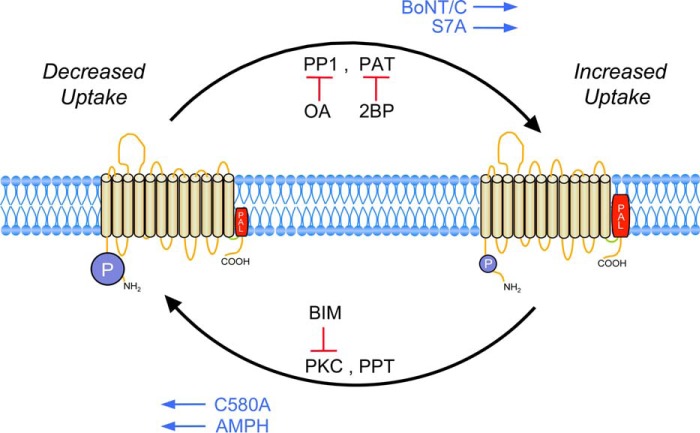

In this study we identify a previously unknown mechanism for regulation of DA transporters via a kinetic process that is driven by reciprocal levels of Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation. Fig. 7 and Table 1 summarize the numerous findings from this study and previous reports that support this concept. In this model the DAT population is driven toward increased phosphorylation and reduced palmitoylation by pharmacological or receptor-mediated activation of PKC, inhibition of protein phosphatase 1, inhibition of PATs, and C580A mutation (Refs. 8, 9, 17, and 19 and Figs. 1–3), whereas the population is driven toward reduced phosphorylation and increased palmitoylation by inhibition of PKC, overexpression of PATs, and S7A mutation (Refs. 8 and 9 and Figs. 1–3). In addition, DAT phosphorylation is increased in a PKC-dependent manner by binding or transport of amphetamines (22) and reduced via an unknown mechanism by botulinum neurotoxin C-mediated proteolysis of syntaxin 1A (37). Importantly, transporter function is connected to these modifications, as conditions that promote high phosphorylation or low palmitoylation reduce transport Vmax and enhance PKC-induced down-regulation (Refs. 8, 9, 17, and 22 and Figs. 4 and 5), and conditions that promote low phosphorylation or high palmitoylation (30, 37, Figs. 4 and 5) increase transport Vmax and suppress PKC-induced down-regulation.

FIGURE 7.

Reciprocal regulation of DAT by phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Schematic representation of DAT Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation cycles showing populations possessing high phosphorylation and low palmitoylation (left) or low phosphorylation and high palmitoylation (right), indicated by the size of blue phosphorylation (P) and red palmitoylation (PAL) symbols. Increased phosphorylation and/or decreased palmitoylation was induced by activation of PKC (PMA, OAG, Substance P), inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 (OA), or inhibition of PATs (2BP), whereas decreased phosphorylation and/or increased palmitoylation was induced by inhibition of PKC (BIM, staurosporin) or overexpression of PATs. Proteins are also driven in the directions indicated by S7A and C580A mutations, binding, or transport of amphetamines (AMPH) or treatment with botulinum neurotoxin C (BoNT/C). Conditions that increase phosphorylation or suppress palmitoylation reduce transport Vmax or enhance down-regulation, and conditions that reduce phosphorylation or increase palmitoylation increase transport Vmax or suppress down-regulation (Table 1). PPT, protein palmitoyl thioesterase.

TABLE 1.

Studies supporting reciprocal regulation of DAT by phosphorylation and palmitoylation

The indicated reference numbers (parentheses) demonstrate changes in the level of DA transport activity or PKC-stimulated transport down-regulation with parallel analysis of DAT phosphorylation (phosph) or palmitoylation (palm) (direction of changes are indicated by arrows). BoNT/C, botulinum neurotoxin C.

| Treatment/condition | Transport reducing conditions |

Transport increasing conditions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ phosph | ↓ palm | ↓ uptake | ↓ phosph | ↑ palm | ↑ uptake | |

| Phosphorylation modulators | PMA (8,9,16, 19,20, 21, 22) | PMA (Fig. 2) | PMA (8,9,16a, 21, 22) | BIM (8,9) | BIM (Fig. 2) | BIM (↓ down-reg) (9) |

| OAG (9) | OAG (9) | Stauro (8,9) | Stauro (↓ down-reg) (8,9) | |||

| SubstanceP (21) | SubstanceP (21) | |||||

| OA (9,19) | OA (Fig. 2) | OA (9, 21) | BonT/C (37) | BonT/C (37) | ||

| AMPH (22) | AMPH (22) | |||||

| Palmitoylation modulators | 2BP (Fig. 2) | 2BP (17) | 2BP (17a) | DHHC2 (Fig. 3) | DHHC2 (30) | DHHC2 (30a) |

| Mutations | C580A (Fig. 1) | C580A (17, Fig. 1) | C580A ↓ Vmax (Fig. 4a) (↑ down-reg) (17Fig. 5)a) | S7A (20) | S7A (Fig. 1) | S7A ↑ Vmax (Fig. 4a) (↓ down-reg) (Fig. 5a) |

a Studies showing the presence of transport up- or down-regulation when DAT endocytosis was blocked or when surface levels did not change.

Several observations now support the occurrence of these transport capacity alterations in both cell systems and brain tissue when endocytosis is blocked or cannot be detected (Table 1). In LLCPK1 cells ConA treatment blocks PMA-induced DAT endocytosis but does not eliminate transport down-regulation (16), and significant levels of down-regulation are also retained in cells subjected to dynamin dominant negative inhibition (16) or treatment with the clathrin inhibitor PitStop2®.5 In rat striatal synaptosomes prepared in hypertonic sucrose, which inhibits clathrin-mediated endocytosis (38), PMA and 2BP induced significant levels of transport down-regulation (∼25 and ∼60%, respectively), with no changes in DAT surface levels detected by surface biotinylation (17). In addition, enhanced palmitoylation of WT DAT driven by overexpression of DHHC enzymes increased DA uptake activity by 20–30% without affecting surface transporter levels (30). These results in combination with our finding of differential steady-state transport velocities in S7A and C580A forms and our evidence that Ser-7 phosphorylation and Cys-580 palmitoylation regulate each other strongly indicate that DAT activity in both cells and brain tissue is controlled by a kinetic mechanism driven by reciprocal phosphorylation and palmitoylation.

The basis for transporter kinetic regulation presumably involves alterations in the rate of the transport cycle. DAT is composed of 12 transmembrane (TM) domains, with TMs 1, 3, 6, and 8 forming the permeation pathway (39). Substrate translocation occurs via an alternating access mechanism in which the protein cycles through outwardly facing, occluded, and inwardly facing conformations that bind and release substrate on opposite sides of the membrane (40). These conformations are governed by extracellular and intracellular gates that control substrate access to the permeation pathway (39) and can be further regulated by Zn2+ binding, which stabilizes the outwardly facing form (41, 42), and interaction of cytoplasmic domains with syntaxin 1A and other binding partners (37, 43, 44). The equilibrium between these conformations determines the rate of forward transport and also impacts cocaine analog binding, which is favored by the outwardly facing form, and substrate efflux, which is thought to be favored by the inwardly facing form (45–48).

Although Ser-7 is far in primary sequence from the TM domains and separated physically from the core active site, its mutation reduces cocaine analog binding affinity and Zn2+ stimulation of binding (20), supporting its ability to impact the protein conformational equilibrium. The transition of DAT from the occluded to the inwardly facing conformation involves major rearrangements of the inner segment of TM1 (49, 50) and loss of interactions between N-terminal intracellular gate residue Arg-60 and its gating partners (4, 51). It is possible that Ser-7 is positioned near these regions and that its phosphorylation state impacts these or other intracellular domain conformational changes that occur during transport. Alternatively, phosphorylation of Ser-7 may regulate transport indirectly by affecting interactions of the N terminus with binding partners, as supported by our finding that botulinum neurotoxin C-induced proteolysis of syntaxin 1A leads to reduced DAT phosphorylation and enhanced transport Vmax (37). The mechanism for transporter regulation by palmitoylation is also likely to be indirect, as TM12, which contains Cys-580, is located outside the transporter core structure and does not contribute directly to the substrate active site (4, 52). Palmitoylation of TM12 may affect its tilt or orientation to indirectly impact the active site, alter interactions occurring between TM domains during the transport cycle, or affect transporter oligomerization or binding partner interactions.

The mechanisms underlying the reciprocal regulation of DAT phosphorylation and palmitoylation levels are also not known. Reciprocity between phosphorylation and palmitoylation has been found for other proteins, and for some this occurs via steric hindrance of the opposite modification. Examples of this include the β2-adrenergic receptor in which palmitoylation of Cys-341 sterically inhibits PKC-mediated phosphorylation of residues Ser-345 and Ser-346, which modulate the ability of the receptor to interact with Gs (53), and the AMPA receptor where palmitoylation of Cys-811 interferes with phosphorylation of Ser-816 and Ser-818, which modulate receptor surface levels (54). DAT differs from these proteins in that Ser-7 and Cys-580 are far apart in primary sequence, although it is not known if they are in three-dimensional proximity. Another possibility is that DAT phosphorylation and palmitoylation could occur in distinct membrane microdomains. DAT is distributed between cholesterol-rich membrane raft and nonraft domains, with those found in rafts possessing the highest proportion of PKC-mediated phosphorylation (16), and palmitoylation drives membrane raft partitioning of many proteins (55).

The finding that DA transport can be modulated at the cell surface by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism is similar to regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors (56) and the serotonin transporter (57), which undergo phosphorylation-mediated desensitization before internalization, and represents a major addition to the current paradigm that DAT regulation occurs by a phosphorylation-independent trafficking process (21, 22). It is possible that endocytotic and kinetic modes of DAT regulation provide distinct temporal functionalities for shaping short or long term dopaminergic tone or are linked to separate regulatory pathways that mediate different outputs. Once DATs are endocytosed they are trafficked to early endosomes where they are sorted for plasma membrane recycling or lysosomal degradation (12, 14). PKC-regulated phosphorylation and palmitoylation may also play roles in these events, as prolonged activation of PKC induces DAT lysosomal degradation (12, 58–60). Data in this study indicate the presence of phosphorylated DAT in intracellular membrane compartments and sustained suppression of DAT palmitoylation induces transporter degradation (17).

Increasing evidence supports a role for these regulatory mechanisms in the control of DA homeostasis in a variety of pathophysiological conditions. With respect to drug abuse, DAT phosphorylation is stimulated by psychostimulant substrates (22), regulates cocaine analog affinity (20), and is necessary for amphetamine-induced efflux (61). In addition, rare DAT coding polymorphisms, several of which have been associated with DA diseases such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and adult parkinsonism, have been shown to impact DAT regulatory properties linked to phosphorylation and palmitoylation including membrane raft partitioning, down-regulation, and efflux (6, 7, 15, 62–64), suggesting a potential contribution of the modifications to mechanisms of DA imbalances. Many of the enzymes that control DAT phosphorylation and palmitoylation are subject to inhibitory mutations, expression level alterations, and targeting defects that have been linked to diseases such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes (65–67), suggesting that similar conditions could contribute to DA imbalances via dysregulation of WT transporters and that these enzymatic inputs could represent therapeutic targets for DA disorders or drug addiction.

Author Contributions

J. D. F. and R. A. V. conceived and directed the project and wrote the paper. A. E. M., D. E. R., J. D. F., M. S., and M. A. S. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and helped write the paper.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Masaki Fukata, National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Japan, for the generous gift of DHHC coding plasmids.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R15 DA031991 (to J. D. F.), R01 DA13147 (to R. A. V.), P20 RR017699 (to the University of North Dakota from the COBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources), and P20 RR016741 (to the University of North Dakota from the INBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources. This work was also supported by an ND EPSCOR Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship (to D. E. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the content of this article.

J. D. Foster and R. A. Vaughan, unpublished data.

- DAT

- dopamine transporter

- rDAT

- rat DAT

- DA

- dopamine

- LLCPK1

- Lewis lung carcinoma-porcine kidney cells

- 2BP

- 2-bromopalmitate

- ABE

- acyl-biotinyl exchange

- BIM

- bisindolylmaleimide

- ConA

- concanavalin A

- MMTS

- methyl methanethiosulfonate

- mAb 16

- monoclonal antibody 16

- OA

- okadaic acid

- OAG

- oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol

- PAT

- palmitoyl acyltransferase

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- poly16

- polyclonal antibody 16

- HPDP biotin

- sulfhydryl-reactive (N-(6-(biotinamido)hexyl)-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)-propionamide

- TM

- transmembrane domain

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1.Giros B., Jaber M., Jones S. R., Wightman R. M., and Caron M. G. (1996) Hyperlocomotion and indifference to cocaine and amphetamine in mice lacking the dopamine transporter. Nature 379, 606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riddle E. L., Fleckenstein A. E., and Hanson G. R. (2005) Role of monoamine transporters in mediating psychostimulant effects. AAPS J. 7, E847–E851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt K. C., and Reith M. E. (2010) Regulation of the dopamine transporter: aspects relevant to psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1187, 316–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pramod A. B., Foster J., Carvelli L., and Henry L. K. (2013) SLC6 transporters: structure, function, regulation, disease association, and therapeutics. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 197–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughan R. A., and Foster J. D. (2013) Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34, 489–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakely R. D., Ortega A., and Robinson M. B. (2014) The brain in flux: genetic, physiologic, and therapeutic perspectives on transporters in the CNS. Neurochem. Int. 73, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowrishankar R., Hahn M. K., and Blakely R. D. (2014) Good riddance to dopamine: roles for the dopamine transporter in synaptic function and dopamine-associated brain disorders. Neurochem. Int. 73, 42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huff R. A., Vaughan R. A., Kuhar M. J., and Uhl G. R. (1997) Phorbol esters increase dopamine transporter phosphorylation and decrease transport Vmax. J. Neurochem. 68, 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaughan R. A., Huff R. A., Uhl G. R., and Kuhar M. J. (1997) Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and functional regulation of dopamine transporters in striatal synaptosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15541–15546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navaroli D. M., Stevens Z. H., Uzelac Z., Gabriel L., King M. J., Lifshitz L. M., Sitte H. H., and Melikian H. E. (2011) The plasma membrane-associated GTPase Rin interacts with the dopamine transporter and is required for protein kinase C-regulated dopamine transporter trafficking. J. Neurosci. 31, 13758–13770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melikian H. E., and Buckley K. M. (1999) Membrane trafficking regulates the activity of the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurosci. 19, 7699–7710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels G. M., and Amara S. G. (1999) Regulated trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. Clathrin-mediated internalization and lysosomal degradation in response to phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35794–35801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loder M. K., and Melikian H. E. (2003) The dopamine transporter constitutively internalizes and recycles in a protein kinase C-regulated manner in stably transfected PC12 cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22168–22174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorkina T., Hoover B. R., Zahniser N. R., and Sorkin A. (2005) Constitutive and protein kinase C-induced internalization of the dopamine transporter is mediated by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Traffic 6, 157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazei-Robison M. S., and Blakely R. D. (2005) Expression studies of naturally occurring human dopamine transporter variants identifies a novel state of transporter inactivation associated with Val382Ala. Neuropharmacology 49, 737–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster J. D., Adkins S. D., Lever J. R., and Vaughan R. A. (2008) Phorbol ester induced trafficking-independent regulation and enhanced phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter associated with membrane rafts and cholesterol. J. Neurochem. 105, 1683–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster J. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2011) Palmitoylation controls dopamine transporter kinetics, degradation, and protein kinase C-dependent regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 5175–5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristensen A. S., Andersen J., Jørgensen T. N., Sørensen L., Eriksen J., Loland C. J., Strømgaard K., and Gether U. (2011) SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 585–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster J. D., Pananusorn B., and Vaughan R. A. (2002) Dopamine transporters are phosphorylated on N-terminal serines in rat striatum. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25178–25186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moritz A. E., Foster J. D., Gorentla B. K., Mazei-Robison M. S., Yang J. W., Sitte H. H., Blakely R. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2013) Phosphorylation of dopamine transporter serine 7 modulates cocaine analog binding. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granas C., Ferrer J., Loland C. J., Javitch J. A., and Gether U. (2003) N-terminal truncation of the dopamine transporter abolishes phorbol ester- and substance P receptor-stimulated phosphorylation without impairing transporter internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4990–5000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cervinski M. A., Foster J. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2005) Psychoactive substrates stimulate dopamine transporter phosphorylation and down-regulation by cocaine-sensitive and protein kinase C-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40442–40449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaffaney J. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2004) Uptake inhibitors but not substrates induce protease resistance in extracellular loop two of the dopamine transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 692–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughan R. A. (1995) Photoaffinity-labeled ligand binding domains on dopamine transporters identified by peptide mapping. Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 956–964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughan R. A., Huff R. A., Uhl G. R., and Kuhar M. J. (1998) Phosphorylation of dopamine transporters and rapid adaptation to cocaine. Adv. Pharmacol. 42, 1042–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spector D. L., Goldman R. D., and Leinwand L. A. (1998) Cells: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster J. D., Yang J. W., Moritz A. E., Challasivakanaka S., Smith M. A., Holy M., Wilebski K., Sitte H. H., and Vaughan R. A. (2012) Dopamine transporter phosphorylation site threonine 53 regulates substrate reuptake and amphetamine-stimulated efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29702–29712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan J. A., and Gilman A. G. (1998) A cytoplasmic acyl-protein thioesterase that removes palmitate from G protein alpha subunits and p21(RAS). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15830–15837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davda D., El Azzouny M. A., Tom C. T., Hernandez J. L., Majmudar J. D., Kennedy R. T., and Martin B. R. (2013) Profiling targets of the irreversible palmitoylation inhibitor 2-bromopalmitate. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1912–1917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rastedt D. E., Foster J. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2014) Multiple palmitoyl acyltransferases modify DAT palmitoylation. FASEB J. 28, 803–805 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorkina T., Richards T. L., Rao A., Zahniser N. R., and Sorkin A. (2009) Negative regulation of dopamine transporter endocytosis by membrane-proximal N-terminal residues. J. Neurosci. 29, 1361–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorkina T., Caltagarone J., and Sorkin A. (2013) Flotillins regulate membrane mobility of the dopamine transporter but are not required for its protein kinase C-ependent endocytosis. Traffic 14, 709–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saunders C., Ferrer J. V., Shi L., Chen J., Merrill G., Lamb M. E., Leeb-Lundberg L. M., Carvelli L., Javitch J. A., and Galli A. (2000) Amphetamine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and cocaine-sensitive mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6850–6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L. B., Chen N., Ramamoorthy S., Chi L., Cui X. N., Wang L. C., and Reith M. E. (2004) The role of N-glycosylation in function and surface trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21012–21020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorkina T., Doolen S., Galperin E., Zahniser N. R., and Sorkin A. (2003) Oligomerization of dopamine transporters visualized in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28274–28283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao A., Richards T. L., Simmons D., Zahniser N. R., and Sorkin A. (2012) Epitope-tagged dopamine transporter knock-in mice reveal rapid endocytic trafficking and filopodia targeting of the transporter in dopaminergic axons. FASEB J. 26, 1921–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cervinski M. A., Foster J. D., and Vaughan R. A. (2010) Syntaxin 1A regulates dopamine transporter activity, phosphorylation and surface expression. Neuroscience 170, 408–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heuser J. E., and Anderson R. G. (1989) Hypertonic media inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis by blocking clathrin-coated pit formation. J. Cell Biol. 108, 389–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita A., Singh S. K., Kawate T., Jin Y., and Gouaux E. (2005) Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forrest L. R., Zhang Y. W., Jacobs M. T., Gesmonde J., Xie L., Honig B. H., and Rudnick G. (2008) Mechanism for alternating access in neurotransmitter transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10338–10343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norregaard L., Frederiksen D., Nielsen E. O., and Gether U. (1998) Delineation of an endogenous zinc-binding site in the human dopamine transporter. EMBO J. 17, 4266–4273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richfield E. K. (1993) Zinc modulation of drug binding, cocaine affinity states, and dopamine uptake on the dopamine uptake complex. Mol. Pharmacol. 43, 100–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvelli L., Blakely R. D., and DeFelice L. J. (2008) Dopamine transporter/syntaxin 1A interactions regulate transporter channel activity and dopaminergic synaptic transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14192–14197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Binda F., Dipace C., Bowton E., Robertson S. D., Lute B. J., Fog J. U., Zhang M., Sen N., Colbran R. J., Gnegy M. E., Gether U., Javitch J. A., Erreger K., and Galli A. (2008) Syntaxin 1A interaction with the dopamine transporter promotes amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beuming T., Kniazeff J., Bergmann M. L., Shi L., Gracia L., Raniszewska K., Newman A. H., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H., Gether U., and Loland C. J. (2008) The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 780–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shan J., Javitch J. A., Shi L., and Weinstein H. (2011) The substrate-driven transition to an inward-facing conformation in the functional mechanism of the dopamine transporter. PLoS ONE 6, e16350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thwar P. K., Guptaroy B., Zhang M., Gnegy M. E., Burns M. A., and Linderman J. J. (2007) Simple transporter trafficking model for amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. Synapse 61, 500–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guptaroy B., Fraser R., Desai A., Zhang M., and Gnegy M. E. (2011) Site-directed mutations near transmembrane domain 1 alter conformation and function of norepinephrine and dopamine transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 520–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnamurthy H., and Gouaux E. (2012) X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature 481, 469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dehnes Y., Shan J., Beuming T., Shi L., Weinstein H., and Javitch J. A. (2014) Conformational changes in dopamine transporter intracellular regions upon cocaine binding and dopamine translocation. Neurochem. Int. 73, 4–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kniazeff J., Shi L., Loland C. J., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H., and Gether U. (2008) An intracellular interaction network regulates conformational transitions in the dopamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17691–17701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beuming T., Shi L., Javitch J. A., and Weinstein H. (2006) A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1630–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moffett S., Adam L., Bonin H., Loisel T. P., Bouvier M., and Mouillac B. (1996) Palmitoylated cysteine 341 modulates phosphorylation of the β2-adrenergic receptor by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21490–21497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin D. T., Makino Y., Sharma K., Hayashi T., Neve R., Takamiya K., and Huganir R. L. (2009) Regulation of AMPA receptor extrasynaptic insertion by 4.1N, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 879–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blaskovic S., Blanc M., and van der Goot F. G. (2013) What does S-palmitoylation do to membrane proteins? FEBS J.280, 2766–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gainetdinov R. R., Premont R. T., Bohn L. M., Lefkowitz R. J., and Caron M. G. (2004) Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 107–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steiner J. A., Carneiro A. M., and Blakely R. D. (2008) Going with the flow: trafficking-dependent and -independent regulation of serotonin transport. Traffic 9, 1393–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miranda M., Wu C. C., Sorkina T., Korstjens D. R., and Sorkin A. (2005) Enhanced ubiquitylation and accelerated degradation of the dopamine transporter mediated by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35617–35624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miranda M., Dionne K. R., Sorkina T., and Sorkin A. (2007) Three ubiquitin conjugation sites in the amino terminus of the dopamine transporter mediate protein kinase C-dependent endocytosis of the transporter. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong W. C., and Amara S. G. (2013) Differential targeting of the dopamine transporter to recycling or degradative pathways during amphetamine- or PKC-regulated endocytosis in dopamine neurons. FASEB J. 27, 2995–3007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khoshbouei H., Sen N., Guptaroy B., Johnson L.', Lund D., Gnegy M. E., Galli A., and Javitch J. A. (2004) N-terminal phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter is required for amphetamine-induced efflux. PLos Biol. 2, E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bowton E., Saunders C., Erreger K., Sakrikar D., Matthies H. J., Sen N., Jessen T., Colbran R. J., Caron M. G., Javitch J. A., Blakely R. D., and Galli A. (2010) Dysregulation of dopamine transporters via dopamine D2 autoreceptors triggers anomalous dopamine efflux associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Neurosci. 30, 6048–6057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakrikar D., Mazei-Robison M. S., Mergy M. A., Richtand N. W., Han Q., Hamilton P. J., Bowton E., Galli A., Veenstra-Vanderweele J., Gill M., and Blakely R. D. (2012) Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder-derived coding variation in the dopamine transporter disrupts microdomain targeting and trafficking regulation. J. Neurosci. 32, 5385–5397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen F. H., Skjørringe T., Yasmeen S., Arends N. V., Sahai M. A., Erreger K., Andreassen T. F., Holy M., Hamilton P. J., Neergheen V., Karlsborg M., Newman A. H., Pope S., Heales S. J., Friberg L., Law I., Pinborg L. H., Sitte H. H., Loland C., Shi L., Weinstein H., Galli A., Hjermind L. E., Møller L. B., and Gether U. (2014) Missense dopamine transporter mutations associate with adult parkinsonism and ADHD. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3107–3120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mochly-Rosen D., Das K., and Grimes K. V. (2012) Protein kinase C, an elusive therapeutic target? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 937–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hornemann T. (2015) Palmitoylation and depalmitoylation defects. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 38, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Figueiredo J., da Cruz E Silva O. A., and Fardilha M. (2014) Protein phosphatase 1 and its complexes in carcinogenesis. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 14, 2–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]