Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of a combined supplementation with magnesium, selenium and coenzyme Q10 on the morphology of the thyroid in patients with benign diseases. The clinical examination and treatment approach aims additionally at treating musculoskeletal and psychological stress.

Methods

A group of 8 patients (5 with hyperthyroidism, 3 with hypothyroidism) who initially attended a public institution received additional treatment at our private institution. The basic pharmacological treatment, i.e. substitution or thyreostatic, was kept unchanged. The inclusion of patients required good quality ultrasound images to be available.

Results

Initially the changes of the musculoskeletal system were corrected. Following this, stress components were also treated. After a period of 2–4 years of supplementation we observed a normalization of thyroid morphology as evidenced on ultrasound while at the same time there was a reduction of perfusion intensity. Thyroid antibody titers decreased in the majority of cases. Failure of the treatment was seen in 2 cases of chronic thyroiditis that was present for more than 10 years. The ultrasound images of these patients suggest a possible fibrosis.

Conclusions

In spite of the limitation due to the small number of cases, our observational study has delivered proof of concept for our examination and treatment model for benign thyroid disease.

General significance

Our results challenge validity of the prevailing dogma of a destructive unstoppable “autoimmune” destructive process of the gland. At the same time it shows new therapeutic options for patients with thyroid disease.

Abbreviations: fT4, free thyroxine; fT3, free triiodothyronine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; Tg Ab, anti-thyroglobulin antibodies; TSH-R-Ab, anti-TSH receptor antibodies; TPO Ab, anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies

Keywords: Magnesium, Selenium, Coenzyme Q10, Thyroid ultrasound, Benign thyroid disease, Thyroiditis

Highlights

-

•

Adequate magnesium levels in blood can be attained by long time supplementation.

-

•

Thyroid morphology in young patients with benign thyroid disease can improve with supplementation.

-

•

Additional supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 is needed in some cases.

-

•

Our results challenge the validity of the dogma of thyroid autoimmunity as an immovable process.

1. Introduction

More than 100 years ago Haraku Hashimoto presented the results of a histological examination of 4 cases of the so-called struma-lymphomatosa [1], a condition that is now known as Hashimoto's thyroiditis. While H. Hashimoto could not offer an explanation for the changes involved, 100 years later Caturegli and coworkers appear to share the same state-of-the-art by stating: “… still incompletely defined etiopathogenesis” (paragraph 1 in [2]). In daily practice ultrasound examination is one easily available method for the visualization of the changes associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In a recent publication Chaudhary and Bano enumerate the characteristic changes seen in Hashimoto's thyroiditis as well as in autoimmune hyperthyroidism: the typical image will show a heterogeneous hypo-echogenicity. The changes in both diseases can sometimes be indistinguishable [3]. The etiopathogenesis, i.e. the cause and development of a disease or an abnormal condition,1 of these benign thyroid diseases has been attributed to a dogmatic construct called autoimmunity which was initiated in the 1950s [4]. At the present time this dogma does not provide any therapeutic alternative and it is generally accepted that the end-stage situation will be the destruction of thyroid tissue.

Our own investigations on the etiopathogenesis of thyroid diseases have relied on a different methodology as immunologists have. In a first stage we described a relation of hyperthyroidism to alterations of the musculoskeletal system which went together with changes in the correlation between magnesium and calcium levels [5]. In another study we described the sub-optimal levels of selenium in patients with thyroid disease [6]. Recently, in 2014, we have been able to disclose a condition of magnesium deficiency that is a common denominator of hypothyroidism [7] as well as of hyperthyroidism [8]. The main events that correlate with this condition of magnesium deficiency are physical and psychological stressors. The introduction of new concepts in the medical field requires a proof of plausibility in order to be accepted. Proof of concept should provide clinical confirmation of a desired effect in patients with a specific disease. In a recent article Wong et al. handled the options of relying on an imaging method for this purpose [9]. The authors mention the following processes: “(1) early clinical experiments that are designed to demonstrate ‘proof of biology’ by testing a novel hypothesis that link target engagement (TE) to drug-induced biological changes expected to give clinical benefit and (2) subsequent clinical experiments that demonstrate proof of concept (PoC), i.e. engaging a particular target is linked to a meaningful change in a clinical end point thus demonstrating a new avenue to treat a condition in patients.” Following these lines of thought this study was conceived to bring a proof of concept of the WOMED model of benign thyroid disease. Our therapy concept includes the correction of musculoskeletal changes as well as treatment of psychological stress together with magnesium and selenium supplementation. The null hypothesis stated that no changes in thyroid morphology as seen in sonographic examinations could be expected to occur following treatment.

2. Materials and methods

We selected a series of 8 female patients initially attending a public institution. Five patients had hyperthyroidism and three had hypothyroidism. The patients were seen between 2008 and 2014. The age of the patients was between 24 and 39 years. In addition to the standard medical care provided at the public institution the subjects were also examined and treated at our private institution following the wish of the patients (WOMED, Innsbruck, Austria). All procedures were done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [10]. The term “The WOMED Model” refers to a combination of examination, diagnostic and therapeutical methods used routinely by us [7].

2.1. Standard and advanced thyroid sonography

The main objective indicator in this study was the sonographic evaluation of thyroid morphology. In the first place routine sonography evaluations were done using the Siemens Sonoline Antares machine using the VFX 13-5 transducer (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). Advanced quantitative 3D-power Doppler sonography was done using a Voluson Pro machine and the VOCAL software [11]. Recent follow-up examinations in December 2014 were done with a Toshiba Xario 200 machine with the 14L5 probe. Color Doppler was done in the Advanced Dynamic Flow ® mode [12], [13]. All sonography studies were done by the same investigator (RM).

2.2. Clinical examination and treatment approach

The principle of the clinical examination is to search for changes of the musculoskeletal system. These can be lateral tension, idiopathic moving toes and blockade of pelvic motion during inspiration [5], [7], [14]. When the subjects present these conditions a supplementation with magnesium is started. The preferred pharmacological form is pure magnesium citrate at a dose of 3 to 4 times 1.4 mmol per day in divided takes. After an initial period of 4 to 6 weeks manual medicine methods as well as acupuncture are then used to correct the alterations [7]. Psychological stress is investigated at the same time. Using a previously described method the influence of stressors is investigated and treated [15]. This treatment requires 3 to 4 sessions. Magnesium supplementation was maintained over a period of at least 4 years.

Thyroid hormones which have been prescribed previously were continued in the same dosage. Anti-thyroid medication was tapered according to the routine laboratory results.

3. Results

The initial sonography studies presented the characteristic inhomogeneous hypo-echogenic pattern. During supplementation and treatment of stressors we observed a restitution of thyroid morphology. This recovery took between 3 and 4 years. At the same time the initially increased vascularity diminished. During the time of magnesium supplementation blood levels of magnesium showed variations. These changes were correlated to previously identified psychological stressors (term examinations, unusual work load, divorce process, evening school).

Two of the cases presented were seen in relation to pregnancy. In the first case the initial TSH value was 17.2 mIU/L. This value dropped to 4.1 under magnesium supplementation. At this time pregnancy was detected and had an uneventful course. Late in pregnancy, 8th month, TSH rose again and thyroid medication was given. In the second case the initial TSH value was 16 mIU/L and dropped to 2.8 after starting on magnesium. In the subsequent months a pregnancy was detected and a healthy normal child was delivered. Thyroid medication was not given at any time. The graphical results are presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8.

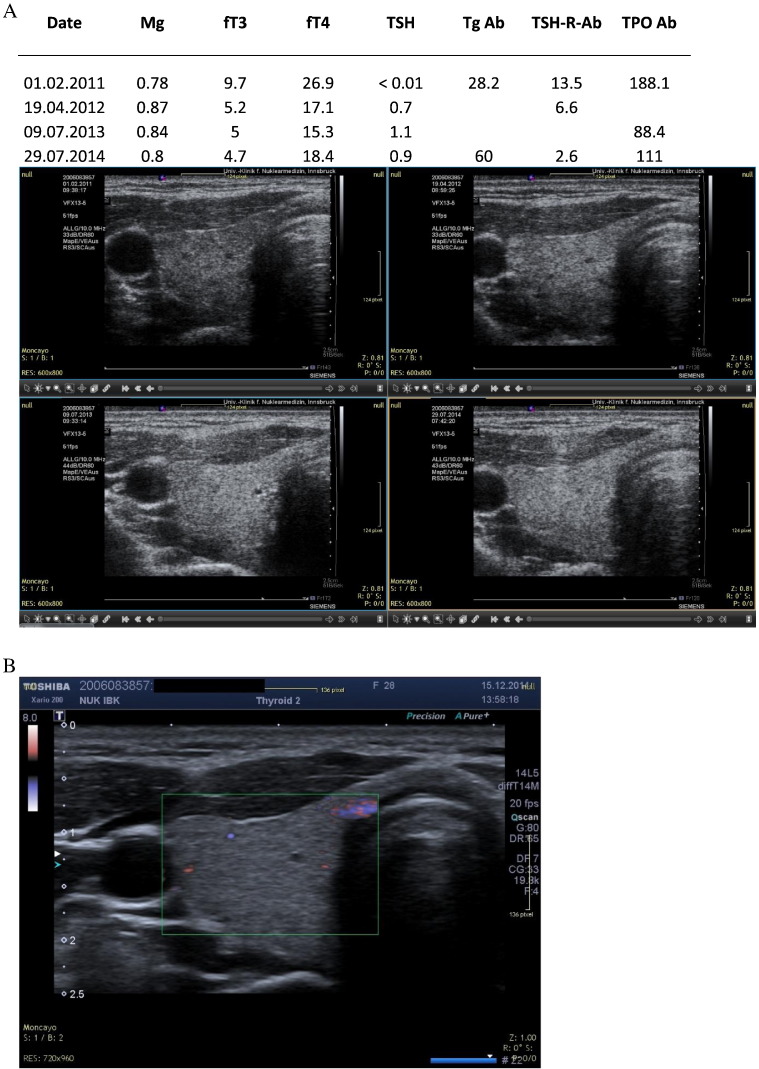

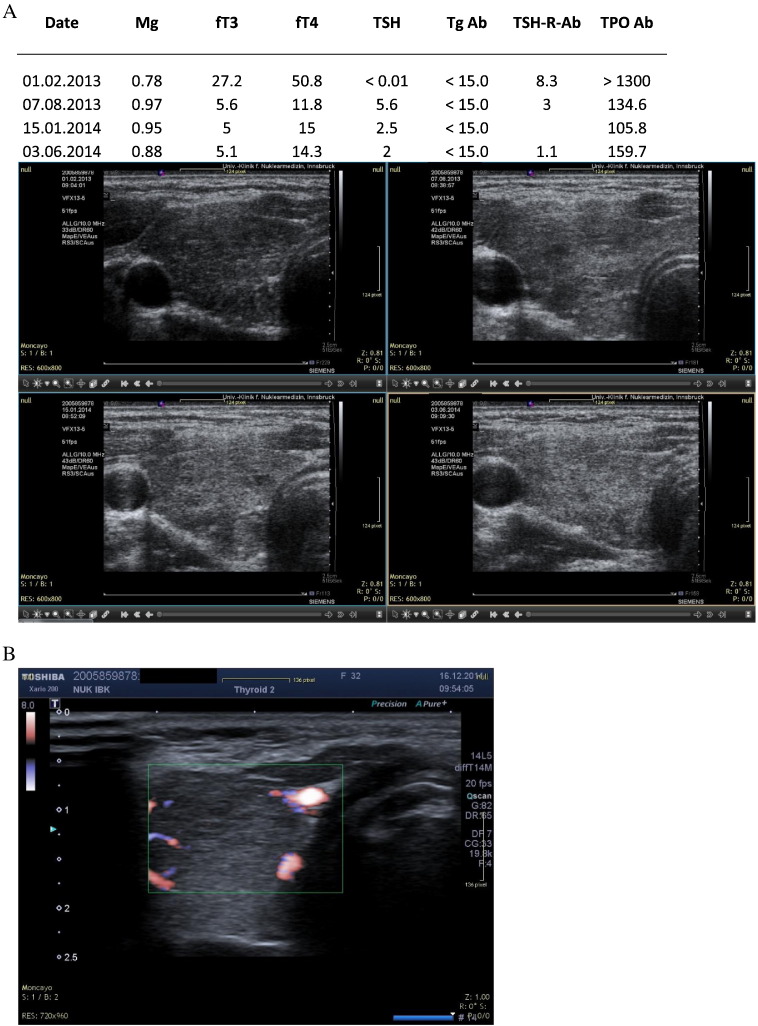

Fig. 1.

A. HM. Female patient with hyperthyroidism. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine. B: Current ultrasound image (2014) confirms normal morphology.

Fig. 2.

A. KC. Hyperthyroidism showing partial recovery. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine. B: Current ultrasound image (2014) showing partial recovery of morphology. Hyperperfusion is no longer present.

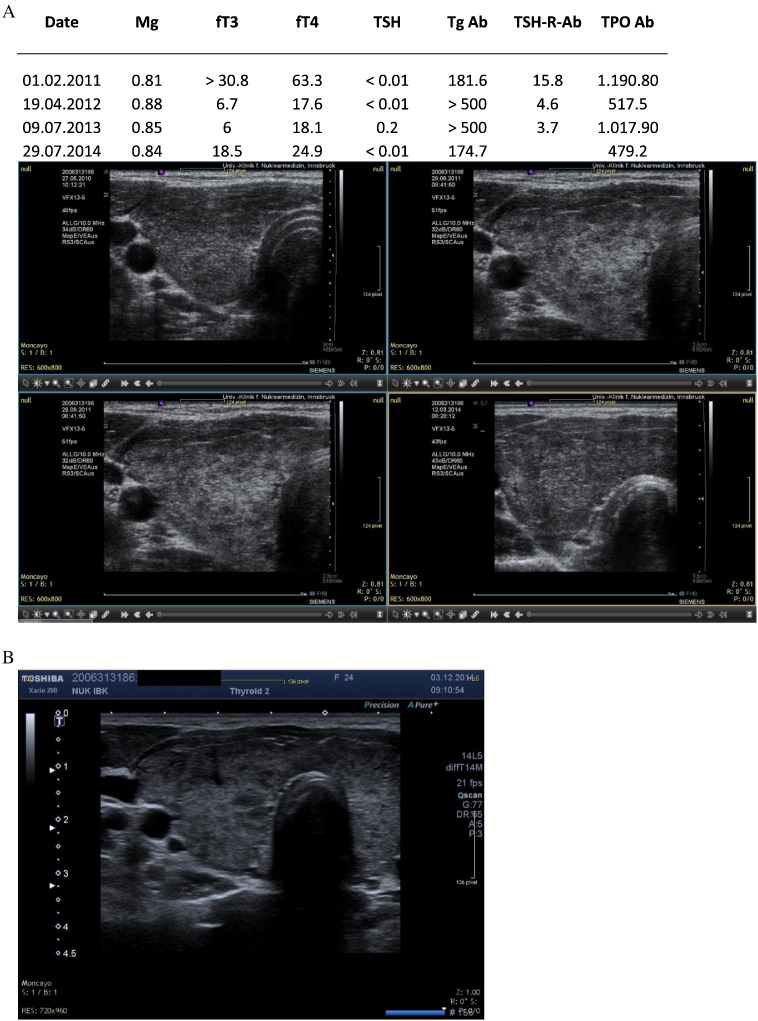

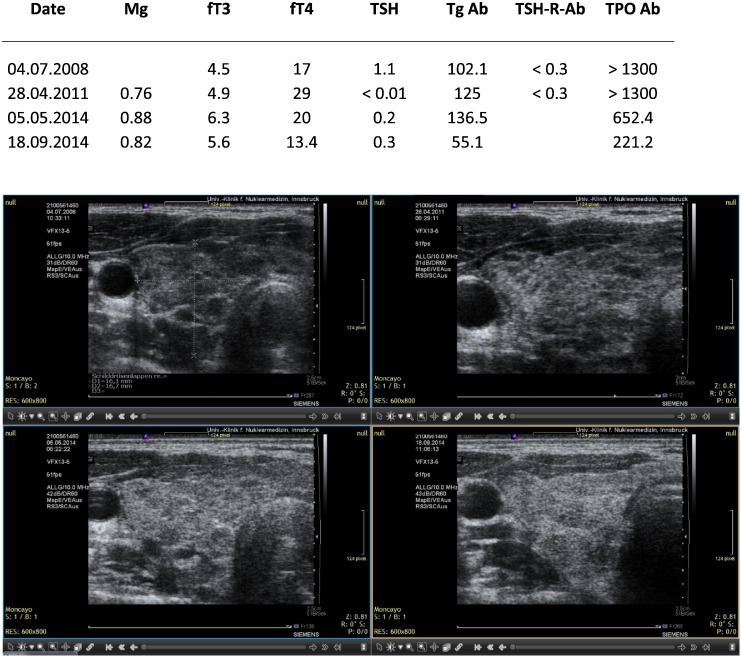

Fig. 3.

A. BM. Patient with hypothyroidism showing recovery after taking magnesium, selenium and coenzyme Q10. In August 2013 the patient was pregnant and thyroid medication was started after the TSH level had risen. At this time, however, fT4 levels were sufficient. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine.

Fig. 4.

KS. Hyperthyroidism in a woman with psychological stressors due to a divorce process min 2012–2014. The drop in magnesium in September 2014 was related to work overload. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine.

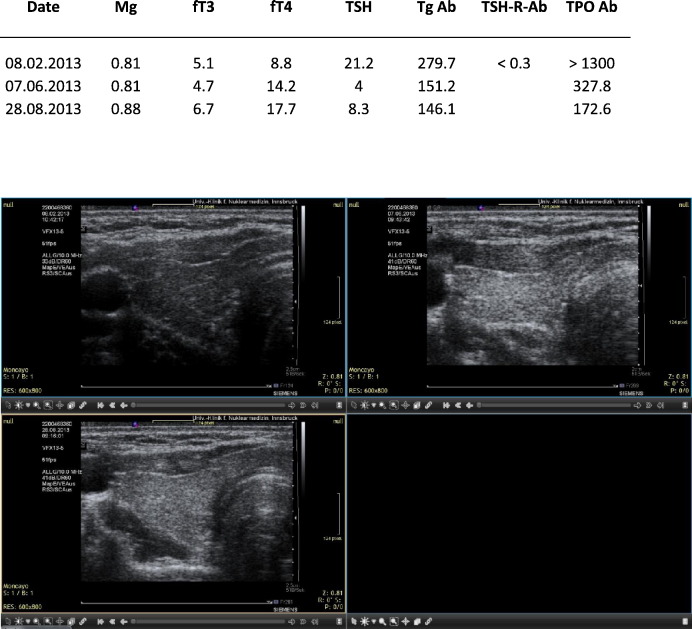

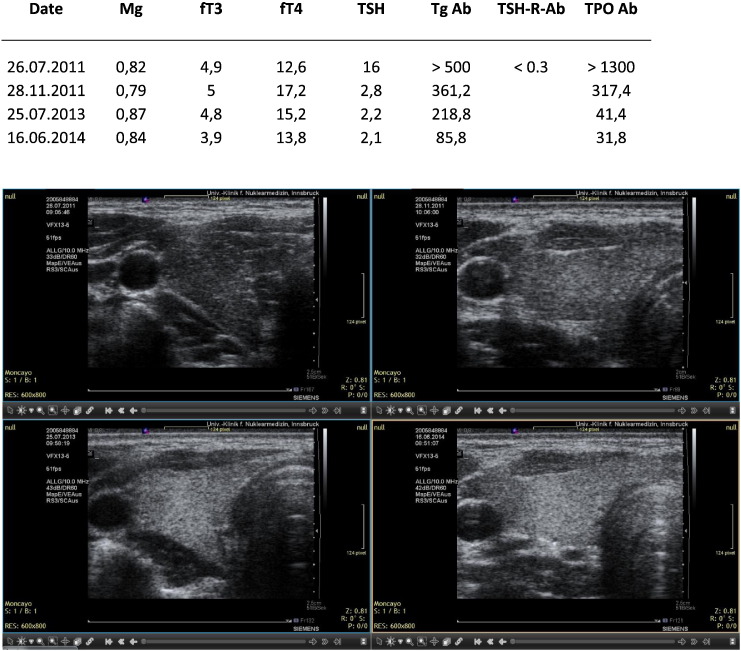

Fig. 5.

A. RN. Hyperthyroidism and subsequent uneventful pregnancy. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine. B: Current ultrasound image (2014) showing partial recovery of morphology.

Fig. 6.

LB. Quite heterogeneous ultrasound pattern initially. Correction with magnesium, selenium and coenzyme Q10. Sequential ultrasound images made with the Siemens Antares machine.

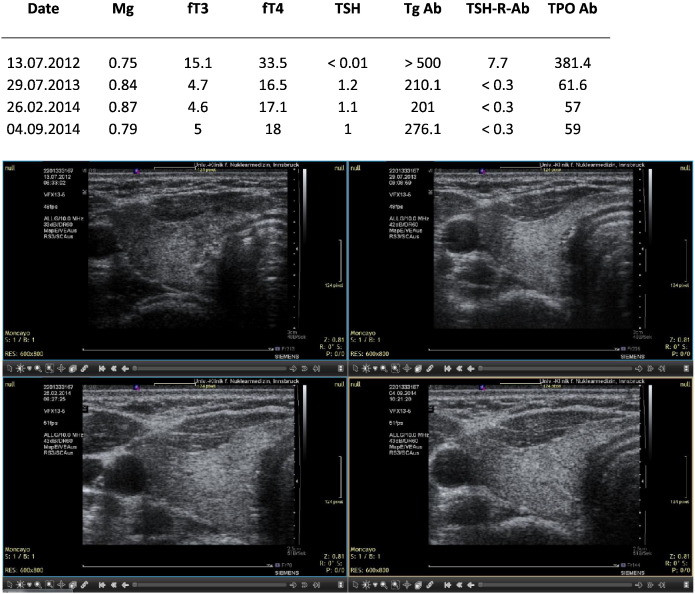

Fig. 7.

SK. Hypothyroidism corrected by magnesium supplementation. Uneventful pregnancy.

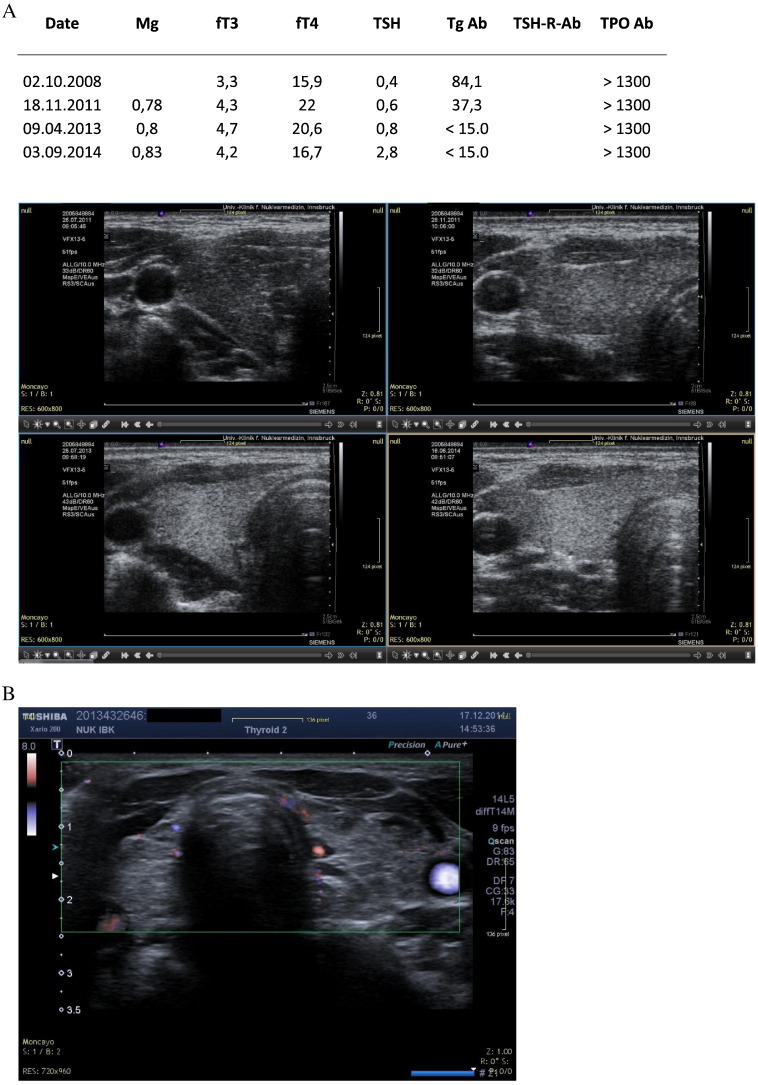

Fig. 8.

A. SR. Hypothyroidism coupled to coenzyme Q10 deficiency. B: Current ultrasound image (2014) showing partial recovery of morphology.

In one case of hypothyroidism with underlying coenzyme Q10 deficiency, hypervascularization could be corrected by means of combined supplementation with magnesium, selenium, and coenzyme Q10 during 3 months. In the last 3 months a Western herb compound was added. In short, the compound includes Ruta graveolens, Anemone pulsatilla, Hypericum perforatum, Serenoa serrulata, Schisandra chinensis, Ophiopogon japonicus, Glycyrrhiza glabra and Zingiber officinale [16]. The theoretical action mode of this multi-agent compound has been described elsewhere [17].

The use of color Doppler in the Advanced Dynamic Flow® mode provided images that better delineate the vascular structures within the thyroid.

A special perfusion pattern was observed in cases with suspected low levels of coenzyme Q10 (Fig. 9). In such a situation wide vessels were visible. This combination was observed in other patients not shown here.

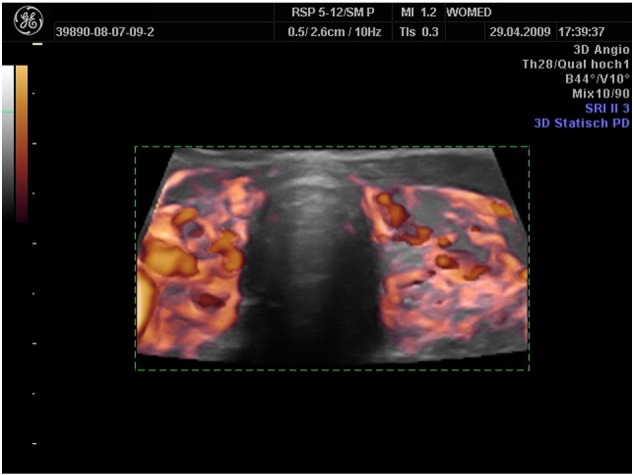

Fig. 9.

3D power Doppler of a woman with hyperthyroidism. Note the thickened vascular structures. We interpret this characteristic as an indirect sign or coenzyme Q10 deficiency. In two patients with thyroiditis the implementation of supplementation did not lead to any improvement of thyroid morphology. Both patients presented an image with hyperechogenic structures on the hypoechogenic thyroid (10A) as well as hyperperfusion (10B).

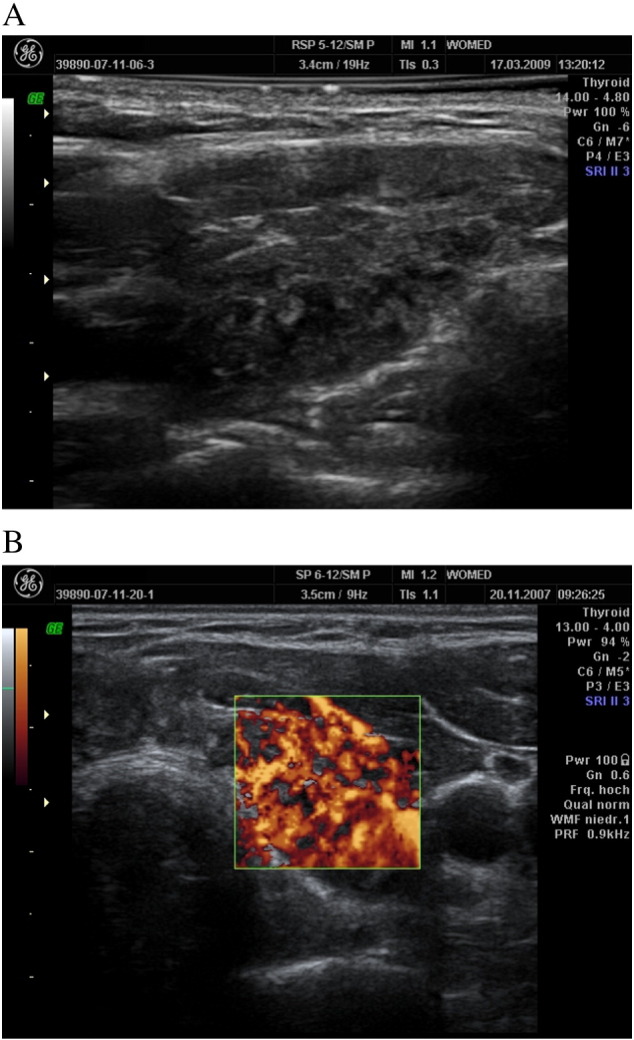

In two patients with thyroiditis the implementation of supplementation did not lead to any improvement of thyroid morphology (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Hyperechogenic structures on the hypoechogenic thyroid (10A) as well as hyperperfusion (10B) suggestive of fibrosis.

4. Discussion

This observational study demonstrates the recovery of thyroid morphology as seen on sonography after treating patients according to the principles of the WOMED model of thyroid disease. This approach expands the usual therapeutical measures used in thyroid disease and it applies both to patients with Grave's disease as well as to patients with Hashimoto's disease. The addition of 3D-power Doppler techniques has allowed us to identify patients who show characteristics of “thickened vessels” which appear to be related to low levels of coenzyme Q10. Two patients who did not respond to supplementation presented imaging data suggestive of fibrosis which can be found in the fibrous variant of thyroiditis [18], [19].

The apparent limitation of the study due to a small number of patients has to be viewed as a relative issue. In this account we have described patients who were initially attending a public hospital. In such a setting the treatment options can be reduced to thyroid hormone substitution or the administration of anti-thyroid drugs for hypo- or hyperthyroidism, respectively. The patients had shown personal motivation to seek additional therapeutic measures because the on-going pharmacological treatment had not eliminated all symptoms. In addition to this, the proof the concept of our treatment model required to have imaging material from the first clinical examination as well as to have follow-up examination done with the same technology. An additional factor that limited the inclusion of more patients was the lack of compliance to the supplementation. Oral magnesium supplementation requires a relatively long time. First positive results can be seen after 6–8 months. Some patients tend to stop supplementation if no improvement has been achieved within 2–3 months.

At our private practice we include all treatment methods according to the WOMED model from the first visit on. Patients seek our medical care for the same reason mentioned above: lack of satisfaction with conventional treatment. Unfortunately the original external imaging material is generally of very poor quality (mostly done with a 7.5 MHz probe). If better digital images had been available we could have included sonography material from more than 100 patients. Our strategy has been to follow up our patients using 3D power Doppler ultrasound. These experiences have been recently published [8]. The preliminary use of sonography with advanced dynamic flow capability appears to offer an alternative to 3D-power Doppler. Further studies are being done on this topic at the moment.

An additional issue that can be derived from our study is related to the concept of thyroid function interfering with pregnancy [20]. Two patients in our series went through pregnancy without any negative effects and taking solely magnesium citrate. This issue has not been addressed by other authors before. Our results suggest a role for magnesium in pregnancy.

The dogmatic model of autoimmunity has been described recently by Caturegli et al. [2]. The authors state: “The normal thyroid gland, being composed of thyroid follicles of various dimensions, scatters the ultrasounds significantly so that the lobes appear bright. In HT, on the contrary, thyroid follicles are destroyed and replaced by small lymphocytes so that the echogenicity of the thyroid parenchyma markedly decreases, becoming similar to that of the surrounding strap muscles.” Out results contradict this statement since a reconstitution of the morphological structure can be attained. Thus, the dogmatic model appears to have overseen practical and simple potentials for recovery. In addition to this we have enumerated flaws in the construction of animal models of thyroid autoimmunity recently (Section 4.8 in [8]).

Magnesium plays a role in thyroid physiology which is reflected by the recovery of normal thyroid morphology. Theoretically by avoiding a progressive deleterious change of thyroid morphology, potential complications such as malignancy should be preventable. We see the main role of magnesium in maintaining the integrity of complex V of the oxidative phosphorylation chain [8]. Alteration of this physiological array could contribute to malignant development since the metabolic pathway of thyroid cells would no longer rely on oxidative phosphorylation [21].

5. Conclusions

For the sake of patients with benign non-nodular thyroid disease, a practical approach based on biochemical parameters (e.g. magnesium, selenium, coenzyme Q10) and objective sonographical data should replace the obscure dogmatic model of autoimmunity.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version.

References

- 1.Hashimoto H. Zur Kenntniss der lymphomatösen Veränderung der Schilddrüse (struma lymphomatosa) Arch. Klin. Chir. 1912;97:219–248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caturegli P. Hashimoto thyroiditis: clinical and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.007. (PM:24434360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhary V., Bano S. Thyroid ultrasound. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;17:219–227. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.109667. (PM:23776892) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roitt I.M. Auto-antibodies in Hashimoto's disease (lymphadenoid goitre) Lancet. 1956;271:820–821. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(56)92249-8. (PM:13368530) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. A musculoskeletal model of low grade connective tissue inflammation in patients with thyroid associated ophthalmopathy (TAO): the WOMED concept of lateral tension and its general implications in disease. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2007;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-17. (PM:17319961) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moncayo R. The role of selenium, vitamin C, and zinc in benign thyroid diseases and of Se in malignant thyroid diseases: low selenium levels are found in subacute and silent thyroiditis and in papillary and follicular carcinoma. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-8-2. (PM:18221503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Exploring the aspect of psychosomatics in hypothyroidism: the WOMED model of body-mind interactions based on musculoskeletal changes, psychological stressors, and low levels of magnesium. Woman. 2014;1:1–11. ( http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213560X14000022) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. The WOMED model of benign thyroid disease: acquired magnesium deficiency due to physical and psychological stressors relates to dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation. BBA. Clin. 2015;3:44–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.11.002. ( http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.11.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong D.F. The role of imaging in proof of concept for CNS drug discovery and development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:187–203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.166. (PM:18843264) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2000;284:3043–3045. (PM:11122593) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Advanced 3D Sonography of the Thyroid: Focus on Vascularity. In: Thoirs K., editor. Sonography, Intech; 2012. pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heling K.S. Advanced dynamic flow — a new method of vascular imaging in prenatal medicine. A pilot study of its applicability. Ultraschall Med. 2004;25:280–284. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato T. Advanced dynamic flow. Igaku Butsuri. 2001;21:142–149. (PM:12766300) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moncayo R. 3D-MRI rendering of the anatomical structures related to acupuncture points of the Dai mai, Yin qiao mai and Yang qiao mai meridians within the context of the WOMED concept of lateral tension: implications for musculoskeletal disease. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2007;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-33. (PM:17425796) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moncayo R. Entspannungstherapie mittels Akupressur und Augenbewegungen. Ergebniskontrolle durch Applied Kinesiology Methoden. Dt. Ztschr. F. Akup. 2006;49:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross J. Practice & Materia Medica, Greenfields Press; Seattle: 2003. Combining Western Herbs and Chinese Medicine. Principles. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moncayo R. Reflections on the theory of “silver bullet” octreotide tracers: implications for ligand–receptor interactions in the age of peptides, heterodimers, receptor mosaics, truncated receptors, and multifractal analysis. EJNMMI Res. 2011;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-9. (PM:22214590) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y. Distinct histopathological features of Hashimoto's thyroiditis with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod. Pathol. 2012;25:1086–1097. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.68. (PM:22555173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz S.M., Vickery A.L., Jr. The fibrous variant of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Hum. Pathol. 1974;5:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(74)80063-8. (PM:4405879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poppe K., Glinoer D. Thyroid autoimmunity and hypothyroidism before and during pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 2003;9:149–161. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg012. (PM:12751777) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinopoulos C. Measurement of ADP–ATP exchange in relation to mitochondrial transmembrane potential and oxygen consumption. Methods Enzymol. 2014;542:333–348. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416618-9.00017-0. (PM:24862274) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.