Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to explore whether a methylation diet influences risk for adenomatous polyps (AP) either independently, or interactively with one-carbon metabolism-dependent gene variants, and whether such a diet modifies blood homocysteine, a biochemical phenotype closely related to the phenomenon of methylation.

Methods

249 subjects were examined using selective fluorescence, PCR and food frequency questionnaire to determine homocysteine, nine methylation-related gene polymorphisms, dietary methionine, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, vitamins B6 and B12.

Results

1). Both dietary methionine and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate intake are significantly associated with plasma homocysteine. 2). Dietary methionine is related to AP risk in 2R3R-TS wildtype subjects, while dietary B12 is similarly related to this phenotype in individuals heterozygous for C1420T-SHMT, A2756G-MS and 844ins68-CBS, and in those recessive for 2R3R-TS. 3). Dietary methionine has a marginal influence on plasma homocysteine level in C1420T-SHMT heterozygotes, while B6 exhibits the same effect on homocysteine in C776G-TCN2 homozygote recessive subjects. Natural 5-methyltetrahydrofolate intake is interesting: Wildtype A1298C-MTHFR, heterozygote C677T-MTHFR, wildtype A2756G-MS and recessive A66G-MSR individuals all show a significant reciprocal association with homocysteine. 4). Stepwise regression of all genotypes to predict risk for AP indicated A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR to be most relevant (p = 0.0176 and 0.0408 respectively). Results were corrected for age and gender.

Conclusion

A methylation diet influences methyl group synthesis in the regulation of blood homocysteine level, and is modulated by genetic interactions. Methylation-related nutrients also interact with key genes to modify risk of AP, a precursor of colorectal cancer. Independent of diet, two methylation-related genes (A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR) were directly associated with AP occurrence.

Keywords: Adenomatous polyp, Folate, Methionine, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6, Homocysteine, Colorectal cancer, Diet

Highlights

-

•

A methylation diet influences regulation of blood homocysteine level.

-

•

Gene variants interact with a methylation diet to influence homocysteine.

-

•

Methylation-related nutrients interact with key genes to modify adenoma risk.

-

•

Independent of diet, A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR were associated with adenoma risk.

1. Introduction

Epigenomic methylation controls gene expression, while methyl groups are also critical for driving neurotransmitter synthesis and thiol regulation, as well as other important areas of metabolism dependent upon methyl group availability. Clinical phenotypes that may be affected by alterations in methylation include those related to cancer, mood disorders and vascular disease [1].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer globally, and the fourth most common cancer-related cause of mortality [2]. Australia has particularly high rates, with CRC being the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [3]. Clinical and histopathological evidence suggests that most CRC arises from pre-existing benign adenomatous polyps (APs) [3], [4]. CRC and its benign adenoma antecedent are often linked to nutrition.

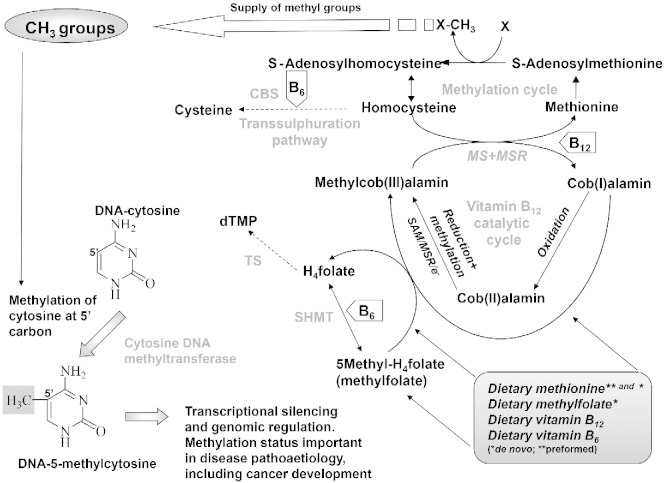

Dietary intake of folic acid (especially 5-methyltetrahydrofolate), vitamins B6, B12 and methionine are particularly important as sources of, or key factors in methyl group availability. This may be relevant in tumourgenesis as virtually all CRCs have aberrantly methylated genes [5]. The dietary supply of the former B-vitamins and methionine is critical in maintaining one-carbon metabolism [6]. Within one-carbon transfers, folate, in the form of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate [7] has a pivotal role in supplying a methyl group to convert homocysteine into methionine, a vitamin B12 dependent process involving methionine synthase (MS) and methionine synthase reductase (MSR) (Fig. 1). The major enzymatic source of one-carbon units in one-carbon metabolism is vitamin B6 dependent serinehydroxymethyl transferase (SHMT), and the key enzyme directing these one-carbon units to methyl group metabolism is methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) [7].

Fig. 1.

Dietary sources of preformed methyl groups and associated metabolism, including de novo synthesis of methionine. The figure shows where nutrients interact as cofactors and the role of methyl groups in gene expression.

De novo methionine derived from one-carbon metabolism provides around half our methionine requirement; diet provides the other half. Methionine is converted to S-adenosylmethionine, the universal methyl donor for methylation of a wide variety of biological substrates [8]. Other enzymes are also crucial to the balance between utilising one-carbon units for de novo methyl groups or dTMP, which is needed for DNA synthesis. Ultimately, both of these phenomena are critical determinants of tumourgenesis.

A shortage of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate or related components of a healthy ‘methylation diet’ will decrease the biosynthesis of S-adenosylmethionine, limiting the availability of methyl groups for methylation reactions. DNA hypomethylation in humans consuming a low folate diet has been reported in a number of studies [9], [10], [11], and it is reasonable to postulate that an individual's risk of developing a benign adenoma or subsequent CRC is influenced by B-vitamin nutrition. Vegetables, particularly green leafy and cruciferous vegetables, are a major source of folate. Studies suggest that both folate intake and folate status are inversely associated with neoplastic risk [12]. Common polymorphisms of the genes responsible for one-carbon metabolism have also been associated with colorectal neoplasia, providing further evidence for a causal relationship between folate and neoplasia [13], [14].

This study examines whether a methylation diet can influence risk for AP either independently or interactively with one-carbon metabolism-dependent gene variants C677T-MTHFR, A1298C-MTHFR, A66G-MSR, A2756G-MS, C1420T-SHMT, 2R3R-TS, 1494del6-TS, C776G-TCN2 and CβS-844ins. The study also examines whether such a diet can modify the blood homocysteine level, a biochemical phenotype closely related to the phenomenon of methylation.

2. Materials and methods

Two hundred and forty nine participants (56.2% female 43.8% male) at Gosford Hospital (NSW) undergoing routine screening for colonic pathology agreed to participate. Subjects were between 40 and 89 years of age at the time of examination (overall mean age 63.3) and were mentally competent to complete a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) interview. Local Human Research Ethics Committee approval was given and informed consent obtained prior to volunteers participating in the study.

2.1. DNA analysis

Folate gene variants were examined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify blood DNA followed by restriction enzyme digestion and gel electrophoresis; 2R3R-TS (rs34743033) and 1494del6-TS (rs16430), C1420T-SHMT (rs1979277), C776G-TCN2 (rs1801198), C677T-MTHFR (rs1801133), A1298C-MTHFR (rs1801131), A2756G-MS (rs1805087), A66G-MSR (rs10380) and CβS-844ins (no rs) were analysed according to the following methods respectively: Horie et al. [15], Ulrich et al. [16], Heil et al. [17], Pietrzyk et al. [18], Van der Put et al. [19], [20], [21], Wilson et al. [22] and Tsai et al. [23]. The term wildtype assumes ancestral genotype.

2.2. Food Frequency Questionnaire for intake of native 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, vitamins B6, B12, and methionine

Estimated daily intake of nutrients was assessed by interviewer administered FFQ. The questionnaire was extensive, covering 225 food items and all food groups. Subjects were also asked to provide a list of all supplements they were taking and were asked about these during the FFQ interview.

The FFQs were analysed using FoodworksTM 2.10.146 (Xyris Software, Brisbane, QLD, Australia). This package uses a number of food databases to cover the majority of foods consumed by Australians. These include the AusFoods (brands), Aus Nut (base foods) and the New Zealand—Vitamin and Mineral Supplements 1999 databases. Methods are as previously described and validated [24], [25], [26], [27]. Unlike the other nutrients assessed here, vitamin B12 data was evaluated by matching food items from the United States Department of Agricultural (USDA) National Nutrient Database for Standard References. Analysis differentiated between natural (5-methyltetrahydrofolate) and synthetic (pteroylmonoglutamate) folate as previously described [25]. It is reasonable to assume that semi-quantitative FFQs provide a relatively good overall measure of dietary habits, and reflect trends prior to any diagnosis of colonic pathology. This approach is assumed to better reflect longer term dietary habits as compared to other commonly used methods of dietary assessment such as the 24 hour recall method or the 7 day food diary. However, clearly this technique is still only a survey that may be subject to surveying bias and other potential variables.

2.3. Homocysteine assay

A sensitive and selective fluorescence assay was used to measure plasma homocysteine. Recombinant homocysteine α,γ-lyase produces hydrogen sulphide (H2S) from homocysteine without interference from cysteine or other plasma components. The H2S that is produced is determined following reaction with dibutylphenylenediamine to form a flourophore that fluoresces at 660 nm (Ex)/710 nm (Em). The method is as described by Tan et al. [28] and was performed on an OP-162 homocysteine reader supplied by Jei Daniel (JD) Biotech Corp, Taipei, Taiwan.

2.4. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP (version 11.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Associations between key variables and related parameters were assessed on an a priori basis, and examined using either standard least squares analysis, or, where nominal/ordinal data was examined, logistic regression analysis that fits the cumulative response probabilities to the logistic distribution function of a linear model using maximum likelihood; p value (p < 0.05) for the Wald χ2 test/effect likelihood ratio test (use as indicated), provided a significance marker for screening effects. Descriptive statistics are presented as appropriate.

Stepwise regression was performed in a mixed direction with significant probability [0.250] that a parameter be considered as a forward step and entered into the model or considered as a backward step and removed from the model. Mallow's Cp criterion was used for selecting the model where Cp first approaches p variables.

While an initial p value of 0.05 was set, a Benjamini–Hochberg False Detection Rate (B-HFDR) correction test was applied to control for multiple comparisons. Despite this, data is also provided without correction, since an argument exists against using such tests in exploratory data where potential relationships could be missed [30].

In using the above statistical tests, all values have been corrected for both age and gender.

3. Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the dietary intake of methionine, vitamins B6, B12 and natural 5-methyltetrahydrofolate. It also gives data for the plasma homocysteine level. Values show the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) for all subjects, subjects who have had at least one AP and subjects who have never had an AP.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for nutrient intake and blood homocysteine (mean and SEM).

| Dietary methionine (g/day) | Dietary vitamin B6 (mg/day) | Dietary vitamin B12 (μg/day) | Dietary 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (μg/day) | Plasma homocysteine (μmol/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 2.353 | 0.099 | 7.218 | 0.872 | 20.589 | 4.280 | 348.72 | 9.99 | 12.747 | 0.289 |

| AP (n = 57) | 2.454 | 0.202 | 5.435 | 0.758 | 11.748 | 2.109 | 356.12 | 16.96 | 13.170 | 0.729 |

| No AP (n = 192) | 2.322 | 0.115 | 7.749 | 1.108 | 23.228 | 5.511 | 346.48 | 11.99 | 12.687 | 0.322 |

Table 2 shows that the relationship between both dietary methionine intake and plasma homocysteine level, and dietary methylfolate intake and homocysteine level, is significant (p = 0.0109 and 0.0035; r = 0.113 and 0.113 respectively). The first association is positive, and the second is negative—relationships that are thus consistent with what might be expected on an a priori basis.

Table 2.

Relationship between i) nutrient intake and adenomatous polyp occurrence and ii) nutrient intake and homocysteine. Values are corrected for age and sex and represent p, r2 and in brackets, slope. Underlined data implies statistically significant (i.e. p<0.05).

| Dietary methionine (g/day) |

Dietary vitamin B6 (mg/day) |

Dietary vitamin B12 (μg/day) |

Dietary 5-methyltetrahydro folate (μg/day) |

Plasma homocysteine (μmol/L) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | r2 (slope) | p | r2 (slope) | p | r2 (slope) | p | r2 (slope) | p | r2 (slope) | |

| AP | NS | – | NS | – | NS | – | NS | – | aNS | – |

| Homocysteine | 0.0109 | 0.113 (0.570) | NS | – | NS | – | 0.0035 | 0.113 (− 0.007) | N/A | N/A |

Not included as part of the model involving nutrient intake and AP risk.

Table 3 examines how methyl group metabolism-related genetic profiles influence the relationship between nutrient intake and risk of AP. Dietary methionine is related to AP risk in 2R3R-TS wildtype subjects, while dietary vitamin B12 is similarly related to this phenotype in individuals heterozygous for C1420T-SHMT, A2756G-MS and 844ins68-CBS, and in those recessive for 2R3R-TS. Table 4 reports how methyl group metabolism-related genetic profiles influence any association between nutrient intakes and plasma homocysteine levels. Dietary methionine has a marginal influence on the plasma homocysteine level in C1420T-SHMT heterozygotes, while vitamin B6 exhibits the same (but significant) effect on homocysteine in C776G-TCN2 homozygote recessive subjects. However, the relationship to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate intake is perhaps most interesting: The wildtype A1298C-MTHFR and recessive A66G-MSR both showed a significant reciprocal association with homocysteine, and again this fits with what might be expected, especially given the critical role of MSR and MTHFR expression products in the de novo pathway of methionine biosynthesis from homocysteine. Dietary 5-methyltetrahydrofolate also exhibits a marginal reciprocal effect on homocysteine in A2756G-MS wildtypes and C677T-MTHFR heterozygotes.

Table 3.

Methyl group metabolism-related genotypes that exhibit a significant association between nutrient intake (methionine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) and adenoma risk. p has been determined using nominal logistic regression followed by an effect likelihood ratio test. Where significant, brackets show r2, slope and (in all cases), number of observations. Italics indicate values approaching significance. Results are corrected for age and sex. Where n < 20 statistics was not performed due to the inherent instability. Bold and underlined data implies statistically significant (i.e. p<0.05).

| Polymorphism | Dietary methionine |

Dietary vitamin B6 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | |

| 1494del6-TS | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (26) | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (26) |

| 2R3R-TS | ⁎0.0139 (0.132, − 0.798, 70) | NS (122) | NS (54) | NS (70) | NS (122) | NS (54) |

| C1420T-SHMT | NS (131) | NS (94) | NS (23) | NS (131) | NS (94) | NS (23) |

| C677T-MTHFR | NS (117) | NS (107) | NS (24) | NS (117) | NS (107) | NS (24) |

| A1298C-MTHFR | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (19) | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (19) |

| A2756G-MS | NS (170) | NS (71) | NS (7) | NS (170) | NS (71) | NS (7) |

| A66G-MSR | NS (51) | NS (115) | 0.0556 (0.110, − 0.865, 82) | NS (51) | NS (115) | NS (82) |

| 844ins68-CBS | NS (207) | NS (40) | N/A | NS (207) | NS (40) | N/A |

| C776G-TCN2 | NS (38) | NS (105) | NS (58) | NS (38) | NS (105) | NS (58) |

| Dietary vitamin B12 |

Dietary 5-methyltetrahydrofolate |

|||||

| Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | |

| 1494del6-TS | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (26) | NS (113) | NS (106) | NS (26) |

| 2R3R-TS | NS (70) | NS (122) | ⁎0.0295, 0.136, 0.143, 54) | 0.0503 (0.102, − 0.004, 70) | NS (119) | NS (54) |

| C1420T-SHMT | NS (131) | ⁎0.0147, 0.074, 0.044, 94) | NS (23) | NS (130) | NS (92) | NS (23) |

| C677T-MTHFR | NS (117) | NS (107) | NS (24) | NS (117) | NS (104) | NS (24) |

| A1298C-MTHFR | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (19) | NS (126) | NS (100) | NS (19) |

| A2756G-MS | NS (170) | ⁎0.0224, 0.114, 0.100, 71 | NS (7) | NS (168) | NS (70) | NS (7) |

| A66G-MSR | NS (51) | NS (115) | NS (82) | NS (49) | NS (114) | NS (82) |

| 844ins68-CBS | NS (207 | ⁎0.0256 (0.095, 0.132, 40) | N/A | NS (204) | NS (40) | N/A |

| C776G-TCN2 | NS (38) | NS (105) | NS (58) | NS (37) | NS (104) | NS (58) |

Table 4.

Methyl group metabolism-related genotypes that exhibit a significant association between nutrient intake (methionine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) and homocysteine. p has been determined using standard least squares regression followed by an effect likelihood ratio test. Where significant, brackets show r2, slope and (in all cases), number of observations. Italics indicate values approaching significance. Results are corrected for age and sex. Where n < 20 statistics was not performed due to the inherent instability. Bold and underlined data implies statistically significant (i.e. p<0.05).

| Polymorphism | Dietary methionine |

Dietary vitamin B6 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | |

| 1494del6-TS | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (25) | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (25) |

| 2R3R-TS | NS (70) | NS (121) | NS (54) | NS (70) | NS(121) | NS (54) |

| C1420T-SHMT | NS (130) | 0.0587 (0.124, 0.851, 94) | NS (23) | NS (130) | NS (94) | NS (23) |

| C677T-MTHFR | NS (116) | NS (107) | NS (24) | NS (116) | NS (107) | NS (24) |

| A1298C-MTHFR | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (18) | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (18) |

| A2756G-MS | NS (169) | NS (71) | NS (7) | NS (169) | NS (71) | NS (7) |

| A66G-MSR | NS (50) | NS (115) | NS (82) | NS (50) | NS (115) | NS (82) |

| 844ins68-CBS | NS (206) | NS (40) | N/A | NS (206) | NS (40) | N/A |

| C776G-TCN2 | NS (37) | NS (105) | NS (58) | NS (37) | NS (105) | ⁎0.0270 (0.239, − 0.171, 58) |

| Dietary vitamin B12 |

Dietary 5-methyltetrahydrofolate |

|||||

| Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | |

| 1494del6-TS | NS (116) | NS (106) | NS (25) | NS (113) | NS (106) | NS (25) |

| 2R3R-TS | NS (70) | NS (121) | NS (54) | NS (70) | NS (118) | NS (54) |

| C1420T-SHMT | NS (130) | NS (94) | NS (23) | NS (129) | NS (92) | NS (23) |

| C677T-MTHFR | NS (116) | NS (107) | NS (24) | NS (116) | ⁎0.0481 (0.196, − 0.006, 104) | NS (24) |

| A1298C-MTHFR | NS (127) | NS (102) | NS (18) | ⁎0.0004 (0.264, − 0.0001, 126) | NS (100) | NS (18) |

| A2756G-MS | NS (169) | NS (71) | NS (7) | ⁎0.0467 (0.103, − 0.004, 167) | NS (70) | NS (7) |

| A66G-MSR | NS (50) | NS (115) | NS (82) | NS (48) | NS (118) | ⁎0.0181 (0.089, − 0.009, 82) |

| 844ins68-CBS | NS (206) | NS (40) | N/A | NS (203) | NS (40) | N/A |

| C776G-TCN2 | NS (37) | NS (105) | NS (58) | NS (36) | NS (104) | NS (58) |

Stepwise regression analysis of all the genotypes was used to generate a model that best predicts the risk for adenoma (n = 247). A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR provided significant p values (p = 0.0176 and 0.0408 respectively) with a whole model r2 of 0.0877. When the model contained all genetic and dietary factors, A66G-MSR remained significant (p = 0.0259) with a whole model r2 of 0.0663. These loci are clearly both critical to the methylation process, and therefore Table 5 shows how the A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR genotypes and allele distribution varies with adenoma phenotype.

Table 5.

Stepwise regression analysis of all genotypes was used to generate a model that best predicts risk for adenoma (n = 247). A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR provided significant p values (p = 0.0176 and 0.0408 respectively) with a whole model r2 of 0.0877 (results corrected for age and sex). When the model contained all genetic and dietary factors, A66G-MSR remained significant (p = 0.0259 corrected for age and sex). The table therefore provides A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR genotype and allele distribution according to adenoma phenotype.

| Polymorphism | Adenoma |

Control |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | Wildtype | Heterozygote | Recessive | |

| A2756G-MS | 73.7% | 19.3% | 7% | 66.7% | 31.8% | 1.5% |

| A66G-MSR | 14% | 42.1% | 43.9% | 22.4% | 47.4% | 30.2% |

| Adenoma |

Control |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype allele | Recessive allele | Wildtype allele | Recessive allele | |

| A2756G-MS | 83.3% | 16.7% | 71.2% | 28.8% |

| A66G-MSR | 35.1% | 64.9% | 46.1% | 53.9% |

When a B-HFDR correction was applied for multiple testing, none of the results in Table 3 withstood the test. However, in Table 4 the relationship for 5-methyltetrahydrofolate remained significant following B-HFDR, with wildtype A1298C-MTHFR and A2756G-MS having corrected p values of 0.0036 and 0.0275 respectively.

4. Discussion

Genomic methylation is a critical process in facilitating gene regulation, with mounting evidence suggesting that micronutrients play an important role in many epigenetic phenomena [29], not just the obvious role that folate, methionine and vitamin B12 in particular play in facilitating methyl group transfer, but in wider phenomena such as microRNA occurrence/function [29]. The link between relevant aspects of one-carbon metabolism and colon pathoaetiology is compelling, and the present data provide valuable new information linking diet to the development of AP.

Findings strongly suggest that a diet that promotes foods rich in components needed as methyl group donors, can influence risk for AP, but not independently. The associations are largely interactive, with methionine linked to 2R3R-TS genotype and vitamin B12 linked to 2R3R-TS, C1420T-SHMT, A2756G-MS and 844ins68-CBS genotypes. The expression products of these genes are notable in that they introduce one-carbon units into one-carbon metabolism (SHMT) and regulate the balance between homocysteine remethylation and transsulphuration (MS and CBS). Thymidylate synthase is the key enzyme in DNA-dTMP synthesis, and is therefore likely to be relevant in the pathoaetiology of colonic neoplasms. Dietary factors were also linked to homocysteine levels via gene interaction, and of particular note is the role of natural food 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in lowering this thiol in an A1298C-MTHFR, C677T-MTHFR, A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR dependent fashion. When the B-HFDR correction is applied for multiple testing, the wildtype A1298C-MTHFR and A2756G-MS remain significant factors (p = 0.0036 and 0.0275 respectively). This is perhaps not too surprising, nor is a potential role for C1420T-SHMT in determining a relationship between dietary methionine and homocysteine (relationship approaches significance); provision of one-carbon units by SHMT will need to be regulated by methionine intake. However, it's more difficult to explain why dietary vitamin B6 should interact with TCN2 genotype to modify homocysteine, although this might stem from an overlap with vitamin B12 status in the regulation of the balance between homocysteine remethylation (B12 dependent) and transsulphuration (B6 dependent), especially given that the TCN2 expression product is important in B12 transport and metabolism.

While a diet rich in components needed as methyl group donors did not independently influence risk for AP, two of the components examined (methionine and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) did independently influence homocysteine. This is particularly interesting as a stepwise regression model that took account of all the polymorphisms examined found that only A2756G-MS and A66G-MSR had a significant influence on the occurrence of the adenoma phenotype. MS and MSR are the key enzyme proteins that convert homocysteine into methionine in a 5-methyltetrahydrofolate dependent reaction central to de novo methyl group synthesis. When a model that contained both all genetic and dietary factors was used, only A66G-MSR remained significant (p = 0.0259). As with the previous data, values were corrected for age and gender.

Van den Veyer has suggested that an optimal “methylation diet” should be investigated as part of the prevention and treatment of both developmental and adult onset disorders citing relevant conditions such as cancers, neural tube defects and Rett syndrome [31]. Certainly genomic methylation, as an epigenetic phenomenon, has been implicated as a mechanism in which maternal nutrition modifies offspring phenotype in both agouti mouse and honeybee models. These DNA methylation-related phenotypic changes have been linked to folate metabolism, and it is believed that organ-specific DNA methylation patterns are established during the foetal period via epigenetic reprogramming. This is not necessarily fixed and can be modulated over the course of a lifespan by environmental influences [32]. There is little doubt that the exposome, particularly dietary exposure, plays a major role in developmental processes, contributing to the developmental origins hypothesis of adult disease. Later in life, aberrant methylation status and dietary factors related to methylation potential have again been linked to cancers with virtually all CRCs having aberrantly methylated genes [5]. The relevance goes beyond this, with aberrant methylation underpinning aspects of the ageing process per se [32]. While the greatest attention has been on folate in respect of epigenetic processes, it seems likely that vitamins B2, B6, B12 and preformed methionine are also potentially important. The present study seems to highlight dietary vitamin B12 and natural 5-methyltetrahydrofolate as being particularly relevant when key variant genes related to methylation are taken into account (Table 3, Table 4).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study implicates dietary nutrients essential for methyl group synthesis in the regulation of blood homocysteine level, and suggests that genetic interactions contribute to this relationship. A methylation diet also seems to interact with key genes to modify the risk of AP, a clinical phenotype linked to the development of CRC. Independent of diet, two methylation-related genes were also directly associated with AP occurrence.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Selhub J. Folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 and one carbon metabolism. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2002;6:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan D.D., Win A.K., Walsh M.D., Walters R.J., Clendenning M., Nagler B., Pearson S.A., Macrae F.A., Parry S., Arnold J., Winship I., Giles G.G., Lindor N.M., Potter J.D., Hopper J.L., Rosty C., Young J.P., Jenkins M.A. Family history of colorectal cancer in BRAF p.V600E-mutated colorectal cancer cases. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:917–926. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AIHW . Cancer series no. 65. Cat. no. CAN 61. AIHW; Canberra: 2012. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program monitoring report: phase 2, July 2008– June 2011. (Viewed 21 October 2013 http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id = 10737421408) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon E.R., Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lao V.L., Grady W.M. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:686–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisco S., Choi S. Gene–nutrient interactions and DNA methylation. J. Nutr. 2002;132:2382S–2387S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2382S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucock M. Folic acid: nutritional biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease processes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000;71:121–138. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Engeland M., Weijenberg M.P., Roemen G.M.J.M., Brink M., de Bruïne A.P., Goldbohm R.A., van den Brandt P.A., Baylin S.B., de Goeij A.F.P.M., Herman J.G. Effects of dietary folate and alcohol intake on promoter methylation in sporadic colorectal cancer: the Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3133–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob R.A., Gretz D.M., Taylor P.C., James S.J., Pogribny I.P., Miller B.J., Henning S.M., Swendseid M.E. Moderate folate depletion increases plasma homocysteine and decreases lymphocyte DNA methylation in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 1998;128:1204–1212. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rampersaud G.C., Kauwell G.P., Hutson A.D., Cerda J.J., Bailey L.B. Genomic DNA methylation decreases in response to moderate folate depletion in elderly women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72:998–1003. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duthie S.J., Narayanan S., Blum S., Pirie L., Brand G.M. Folate deficiency in vitro induces uracil misincorporation and DNA hypomethylation and inhibits DNA excision repair in immortalized normal human colon epithelial cells. Nutr. Cancer. 2000;37:245–251. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC372_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch S., Sanchez H., Albala C., de la Maza M.P., Barrera G., Leiva L., Bunout D. Colon cancer in Chile before and after the start of the flour fortification program with folic acid. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;21:436–439. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328306ccdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slattery M.L., Potter J.D., Samowitz W., Schaffer D., Leppert M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, diet, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marugame T., Tsuji E., Kiyohara C., Eguchi H., Oda T., Shinchi K., Kono S. Relation of plasma folate and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism to colorectal adenomas. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003;32:64–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horie N., Aiba H., Oguro K., Hojo H., Takeishi K. Functional analysis and DNA polymorphism of the tandemly repeated sequences in the 5′-terminal regulatory region of the human gene for thymidylate synthase. Cell Struct. Funct. 1995;20:191–197. doi: 10.1247/csf.20.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrich C.M., Bigler J., Velicer C.M., Greene E.A., Farin F.M., Potter J.D. Searching expressed sequence tag databases: discovery and confirmation of a common polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1381–1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heil S.G., Van der Put N.M., Waas E.T., den Heijer M., Trijbels F.J., Blom H.J. Is mutated serine hydroxymethyltransferase (shmt) involved in the etiology of neural tube defects? Mol. Genet. Metab. 2001;73:164–172. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pietrzyk J.J., Bik-Multanowski M. 776C > G polymorphism of the transcobalamin II gene as a risk factor for spina bifida. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003;80:364. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Put N.M.J., Steegers-Theunissen R.P.M., Frosst P., Trijbels F.J., Eskes T.K., van den Heuvel L.P., Mariman E.C., den Heyer M., Rozen R., Blom H.J. Mutated methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase as a risk factor for spina bifida. Lancet. 1995;346:1070. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Put N.M., Gabreels F., Stevens E.M., Smeitink J.A., Trijbels F.J., Eskes T.K., van den Heuvel L.P., Blom H.J. A second common mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene: an additional risk factor for neural tube defects? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62:1044–1051. doi: 10.1086/301825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van der Put N.M.J., Van der Molen E.F., Kluijtmans L.A.J., Heil S.G., Trijbels J.M., Eskes T.K., Van Oppenraaij-Emmerzaal D., Banerjee R., Blom H.J. Sequence analysis of the coding region of human methionine synthase: relevance to hyperhomocysteinaemia in NTD and vascular disease. Q. J. Med. 1997;90:511–517. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.8.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson A., Platt R., Wu Q., Leclerc D., Christensen B., Yang H., Gravel R.A., Rozen R. A common variant in methionine synthase reductase combined with low cobalamin (vitamin B12) increases risk for spina bifida. Mol. Genet. Metab. 1999;67:317–323. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai M.Y., Bignell M., Schwichtenberg K., Hanson N.Q. High prevalence of a mutation in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;59:1262–1267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucock M., Yates Z., Martin C., Choi J.-H., Boyd L., Tang S., Naumovski N., Roach P., Veysey M. Hydrogen sulphide related thiol metabolism and nutrigenetics in relation to hypertension in an elderly population. Genes Nutr. 2013;8:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucock M., Yates Z., Boyd L., Naylor C., Choi J.-H., Ng X., Skinner V., Wai R., Kho R., Tang S., Roach P., Veysey M. Vitamin C related nutrient-nutrient and nutrient-gene interactions that modify folate status. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013;52:569–582. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucock M.D., Martin C.E., Yates Z.R., Veysey M. Diet and our genetic legacy in the recent anthropocene: a Darwinian perspective to nutritional health. J. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014;19:68–83. doi: 10.1177/2156587213503345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucock M., Ng X., Boyd L., Skinner V., Wai R., Tang S., Naylor C., Yates Z., Choi J.-H., Roach P., Veysey M. TAS2R38 bitter taste genetics, dietary vitamin C, and both natural and synthetic dietary folic acid predict folate status, a key micronutrient in the pathoaetiology of adenomatous polyps. Food Funct. 2011;2:457–465. doi: 10.1039/c1fo10054h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan Y., Hoffman R.M. A highly sensitive single-enzyme homocysteine assay. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1388–1394. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckett E.L., Yates Z., Veysey M., Duesing K., Lucock M. The role of vitamins and minerals in modulating the expression of microRNA. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2014;9:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0954422414000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelman A., Hill J., Yajima M. Why we (usually) don't have to worry about multiple comparisons. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2012;5:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van den Veyer I.B. Genetic effects of methylation diets. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002;22:255–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim K.C., Friso S., Choi S.W. DNA methylation, an epigenetic mechanism connecting folate to healthy embryonic development and aging. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009;20:917–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.