Abstract

Background

The initiation of a pregnancy is a process that requires adequate energetic support. Recent observations at our Institution suggest a central role of magnesium in this situation. The aim of this study was to evaluate magnesium, zinc, selenium and thyroid function as well as anti-Müllerian hormone in early pregnancy following in-vitro fertilization as compared to spontaneous successful pregnancies.

Results

A successful outcome of pregnancy after IVF treatment was associated with 2 parameters: higher levels of anti-Müllerian hormone as well as higher levels of magnesium in the pre-stimulation blood sample. These two parameters, however, showed no correlation. Spontaneous pregnancies as well as pregnancies after IVF show a fall of magnesium levels at 2–3 weeks of gestation. This drop of magnesium concentration is larger following IVF as compared to spontaneous pregnancies. Parallel to these changes TSH levels showed an increase in early IVF-pregnancy. At this time point we also observed a positive correlation between fT4 and TSH. This was not observed in spontaneous pregnancies. Thyroid antibodies showed no correlation to outcomes.

Conclusions

In connection with the initiation of pregnancy following ovarian stimulation dynamic changes of magnesium and TSH levels can be observed. A positive correlation was found between fT4 and TSH in IVF pregnancies. In spontaneous pregnancies smaller increases of TSH levels are related to higher magnesium levels.

General significance

We propose that magnesium plays a role in early pregnancy as well as in pregnancy success independently from anti-Müllerian hormone. Neither thyroid hormones nor thyroid antibodies were related to outcome.

Keywords: Thyroid function, TSH, fT4, fT3, Magnesium, Pregnancy, IVF

Highlights

-

•

Lack of correlation of thyroid function parameters to IVF outcome

-

•

Significant drop of magnesium levels in early pregnancy after IVF

-

•

Positive correlation between fT4 and TSH levels in early pregnancy following IVF

-

•

Higher anti-Müllerian hormone levels are associated to successful IVF pregnancies.

-

•

Higher magnesium levels are associated to successful IVF pregnancies.

1. Introduction

In general physiological terms the metabolic needs during pregnancy are determined by a higher energetic output due to the development and growth of the fetus [1]. Historical accounts tell about an increase of thyroid volume during early pregnancy which can be interpreted as a correlate to an increased need of thyroid hormones [2]. Thyroid function plays an important role in this context since its actions are involved in energy delivery through mitochondrial processes [3], [4]. The exact role of thyroid function in infertility and pregnancy, however, has been debated since decades. Some of the first modern investigations on this topic which included determinations of thyroid function parameters, i.e. protein-bound iodine (PBI), were published in 1948 [5]. The past decades have witnessed many opinions and inconclusive results.

The utility and importance of an evaluation of thyroid function in the sensible area of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatments, e.g. in-vitro fertilization (IVF), is also a matter of discussion. In hypothyroidism, the delivery rate after IVF has been described as not optimal even when the patients were receiving substitution treatment [6]. A recent study by Mintziori et al. has questioned the relevance of recommended TSH levels as well as that of thyroid serology on the outcome of IVF [7]. Gracia et al. have described significant changes of fT4 and TSH following ART, however they recognized that the results needed to be compared to those which could be found in women attempting pregnancy without assistance [8]. Reinblatt et al. have investigated the relation of estradiol levels to TSH levels following ART [9]. The authors showed that TSH does not change significantly during the course of IVF treatment. One limitation of this study, as stated by the authors, was that fT4 levels were not measured. A similar situation can be found in the study by Benaglia et al. [10].

Next to thyroid function estrogen action is also necessary in early pregnancy. On the molecular level estradiol binding to its receptor requires magnesium [11]. Experimental data has shown that the addition of selenium to cultured granulosa cells will increase estradiol production [12]. Estrogens can inhibit iodine release from the thyroid [13], thus there could be a physiological mechanism that explains why TSH increases.

Three recent studies at our Institution have demonstrated magnesium deficiency as a common central biochemical alteration associated with either hypothyroidism [14] or hyperthyroidism [15] as well as with thyroid morphology [16]. Magnesium deficiency is also related to situations of psychological and physical stress. Correcting the stress components together with adequate magnesium supplementation, e.g. magnesium citrate, thyroid function can improve. At the same time the well-being of the patients is improved. Some cases will also require selenium and coenzyme Q10 supplements. On physiological terms, our model of benign thyroid disease considers magnesium deficiency as a condition that leads to mitochondrial dysfunction by altering the functional integrity of Complex V of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This alteration can result in less energy availability which is most commonly expressed as fatigue.

The role of magnesium in pregnancy has been a matter of investigation since decades. In 1930 Coons and Blunt described a negative magnesium balance toward the end of pregnancy [17]. Hurley, Cosens and Theriault described in 1976 teratogenic effect of magnesium deficiency in rats [18]. Experiments conducted by Wang et al. demonstrated adverse effects of magnesium deficiency on pregnancy outcome [19]. The animals put on a low magnesium diet had a high incidence of still births as well as a high incidence of mortality of live offspring in the post-partum period. If magnesium deficiency was introduced during lactation, the offspring had low serum and carcass magnesium values. Magnesium depletion during lactation also affected the mothers. An additional factor that can potentiate embryotoxic effects of magnesium deficiency is stress [20]. In the human setting we have demonstrated that stress influences the quality of life of patients with hypothyroidism while at the same time increased stress scores correlate with lower magnesium levels [14].

Following these introductory lines of thought we designed this study with the aim to analyze thyroid function parameters (fT3, fT4, TSH) and thyroid antibodies together with determinations of serum magnesium, zinc, selenium, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in patients undergoing IVF procedures. Data were collected prior to pregnancy as well during early pregnancy. Cases of spontaneous successful pregnancies were taken as a control group.

2. Materials and methods

This observational study was based on the clinical data obtained at our Institution (WOMED Therapiezentrum Kinderwunsch GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria) in the time period 2005–2012. All clinical procedures were conducted observing the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki [21]. Since the beginning of our clinical work in 2002 emphasis has been put on diagnostic procedures that included determinations of micronutrients and metals as well as a full evaluation of thyroid function [22] and thyroid ultrasound [23].

The discriminating characteristic for the study cohorts was the successful outcome of pregnancy. A successful pregnancy (IVF-pos.) was the result of either IVF or IVF following intra-cytoplasmatic sperm injection (ICSI) (n = 78). A control group with negative outcome after IVF (IVF-neg.; n = 38), in spite of having had class A embryos at embryo transfer [24], was included. These two groups were compared with women who had a successful spontaneous pregnancy (n = 28).

In all patients' biochemical data at a pre-pregnancy state was available. In the IVF group a second sample was also taken at the beginning of pregnancy, i.e. app. 2–3 weeks after embryo transfer. A sequential sample was also available at an early time of spontaneous pregnancy, i.e. the day when the pregnancy test was carried out, as well as in the 3rd trimester. The laboratory determinations included: fT3, fT4, TSH, thyroid antibodies, magnesium, zinc, selenium, FSH, hCG and estradiol as well as anti-Müllerian hormone. All determinations were carried out at a local laboratory facility (Labor Philadelphy, Innsbruck, Austria, http://www.phillab.at/).

Statistical analysis was done using IBM-SPSS version 21. Sequential data from the same patients were compared using Student's paired t-test. Data from the 3 groups were compared using ANOVA. A result was called significant if the p-value was < 0.05. Graphical data presentation was done using the box plot procedure.

3. Results

3.1. IVF characteristics

The mean age of the patients in the three study groups were: IVF-pos. 33.1 ± 4.1, IVF-neg. 34.3 ± 4.5, and spontaneous pregnancy 30.8 ± 5.2 years. Among all patients who required ART the number of previous pregnancies was as follows: 22 patients had 1, 3 had 2, and 1 patient had had 4 pregnancies. The number of follicles, the quality of follicles, as well as the number of oocytes did not differ between the IVF-pos. and IVF-neg. groups. In the IVF-pos. groups 2 patients received Gonal F® (Follitropin alfa), 41 patients had a long stimulation protocol, and 28 patients, a short stimulation protocol. In the IVF-neg. group 19 patients underwent a long stimulation protocol and 17 a short protocol. In the IVF-pos. groups 45 patients underwent IVF, 25 patients had ICSI, and 3 patients had testicular sperm extraction (TESE). In the IVF-neg. group the corresponding values were 23, 12, and 2 respectively. None of these basal characteristics showed any correlation to thyroid parameters, nor magnesium.

3.2. Laboratory parameters previous to stimulation or pregnancy

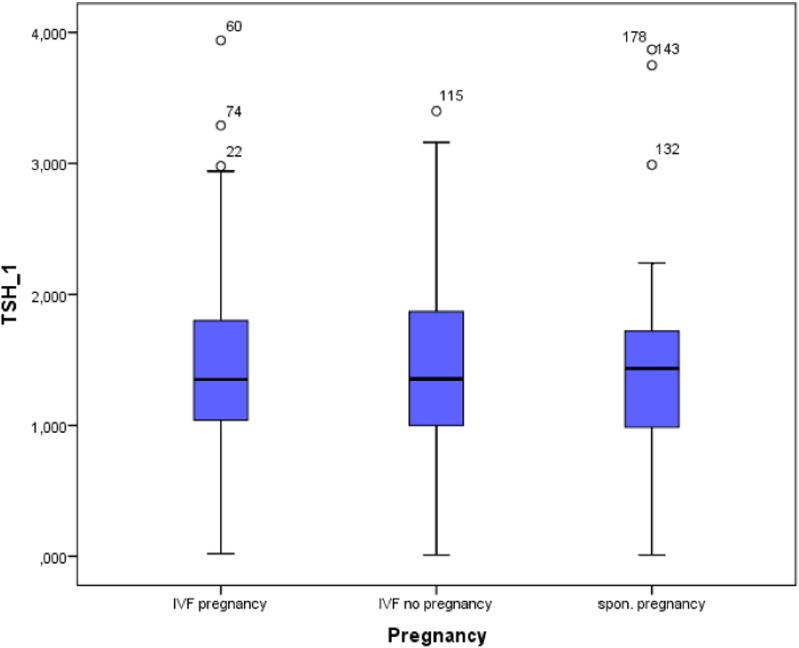

Basal thyroid function parameters, fT3, fT4 and TSH, did not differ between the 3 study groups. This was also observed for zinc, and selenium. In both IVF groups TSH values showed no correlation to either age, number of follicles or fertilization procedure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Box plot figure showing the observed TSH levels in the 3 study groups, p = n.s.

The percentage of positive findings for thyroid peroxidase antibodies was: 20.8% in IVF-pos., 12.9% in IVF-neg., and 15.4% in spontaneous pregnancies. The corresponding values for elevated anti-thyroglobulin antibodies were: 13.2%, 6.3%, and 15.4%, respectively.

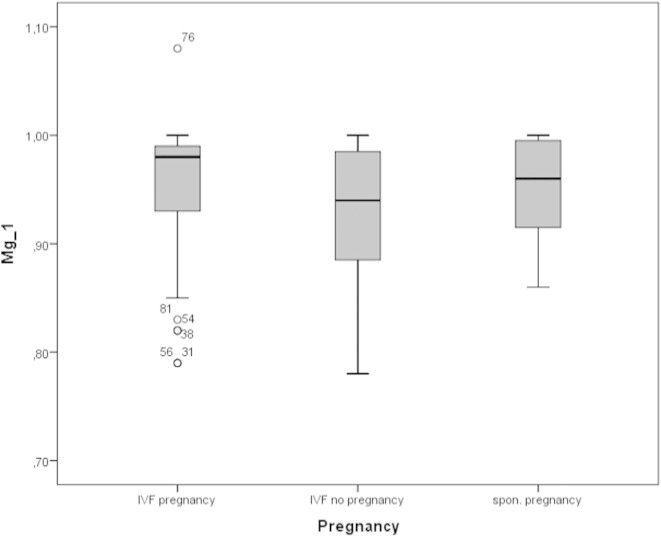

Serum levels of magnesium were higher in the IVF-pos. group compared to IVF-neg. group: 0.95 ± 0.06 vs. 0.93 ± 0.06 mmol/l, respectively (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). This was also observed when spontaneous pregnancies were compared to the IVF-neg. group: 0.95 ± 0.05 vs. 0.93 ± 0.06 mmol/l respectively (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Box plot figure showing the observed magnesium levels in the 3 study groups, p = n.s.

In connection to the IVF treatment we did not observe any relation between magnesium concentration and the number of follicles, nor the number of oocytes retrieved. Patients having either IVF or ICSI had similar magnesium levels. The AMH levels prior to stimulation were higher in the IVF-pos group as compared to the IVF-neg group: 36 ± 23.8, vs. 13 ± 19.2 pmol/l, respectively (p = 0.018).

3.3. Sequential parameters during early pregnancy

Table 1 shows the results for the relevant parameters.

Table 1.

Sequential changes of the biochemical parameters in early pregnancy.

Time points: _1: basal screening, _2: early pregnancy app. week 2–3, and _3: third trimester.

| IVF preg | IVF no preg | Spontaneous | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMH | 36.0 ± 23.8 | 19.2 ± 12.9 | |

| TSH_1 | 1.48 ± 0.69 | 1.50 ± 0.82 | 1.49 ± 0.92 |

| TSH_2 | 2.06 ± 1.06 | 1.44 ± 0.78 | |

| TSH_3 | 1.43 ± 0.57 | ||

| fT3_1 | 4.18 ± 0.82 | 4.38 ± 0.67 | 4.32 ± 1.30 |

| fT3_2 | 4.36 ± 0.69 | 4.34 ± 0.91 | |

| fT3_3 | 4.20 ± 0.56 | ||

| fT4_1 | 13.41 ± 2.25 | 14.67 ± 2.87 | 13.74 ± 4.24 |

| fT4_2 | 14.37 ± 2.24 | 14.12 ± 2.26 | |

| fT4_3 | 12.09 ± 1.52 | ||

| Mg_1 | 0.95 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| Mg_2 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | |

| Mg_3 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | ||

| Zn_1 | 13.12 ± 2.20 | 13.31 ± 2.34 | 13.53 ± 2.34 |

| Zn_2 | 12.72 ± 2.52 | 12.88 ± 2.10 | |

| Zn_3 | 10.41 ± 1.54 | ||

| SE_1 | 82.65 ± 25.06 |

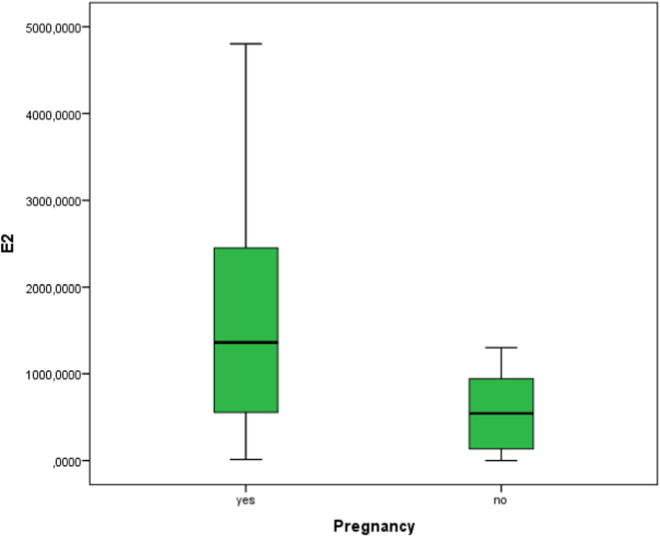

3.3.1. Estradiol levels following IVF

Estradiol levels were higher in the IVF-pos group as compared to the IVF-neg group, 1527 ± 1256.28, vs. 578.38 ± 487.57 pmol/l, respectively (p = 0.074) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Estradiol levels in relation to IVF outcome.

3.3.2. Thyroid function tests

In women with spontaneous pregnancies a slight drop in the concentration of TSH was observed (p = n.s.). In contrast to this situation there was a rise of TSH levels in the IVF-pos. group in the second sample: 1.47 ± 0.69 vs. 2.19 ± 1.56 mIU/l, respectively (p < 0.001). In the IVF-pos. group with a positive thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody finding the rise of TSH levels was higher than in antibody negative patients. This rise occurred in spite of having had higher magnesium levels at the pre-stimulation time point. Serum levels of fT3 and fT4 did not change in the sequential observation.

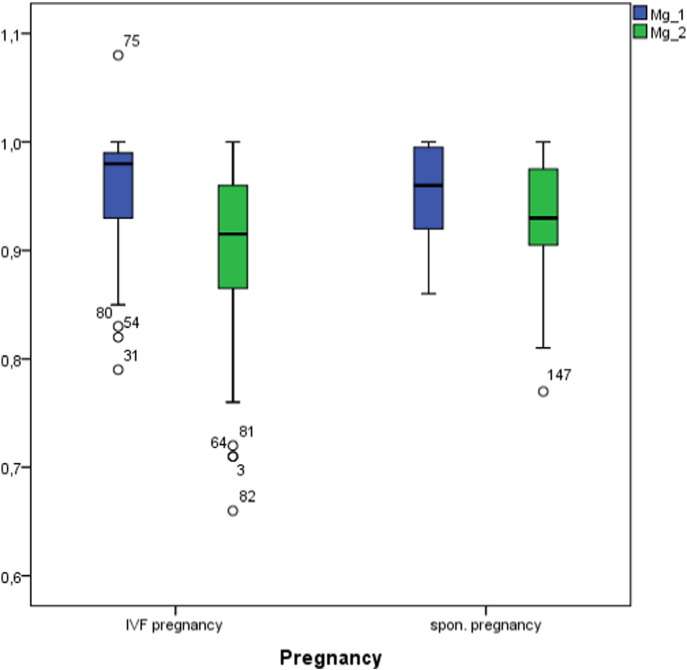

3.3.3. Magnesium and zinc levels

We found no relation between the number of previous pregnancies or the number of IVF interventions and magnesium levels (ANOVA, n.s.). We observed a significant drop of magnesium levels in the IVF-pos. group from 0.96 ± 0.05 mmol/l to 0.91 ± 0.08 mmol/l (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The changes were common to all stimulation protocols used. There was a slight drop of magnesium levels in spontaneous pregnancies from 0.95 ± 0.05 mmol/l to 0.92 ± 0.05 mmol/l (p = n.s.). In the 28th week of pregnancy we observed a drop in the concentration of zinc and magnesium in the group with spontaneous pregnancies. Magnesium levels in early pregnancy did not show any correlation with E2 levels.

Fig. 4.

Sequential magnesium levels in the pregnancy groups.

Zinc levels showed no significant changes during early pregnancy (13.12 ± 2.20 mmol/l to 12.72 ± 2.52 mmol/l in the IVF-pos group, and 13.53 ± 2.34 mmol/l to 12.88 ± 2.10 mmol/l for the group of spontaneous pregnancies). In this latter group a late drop to 10.41 ± 1.54 was observed. Zinc levels did not show any correlation to the other parameters.

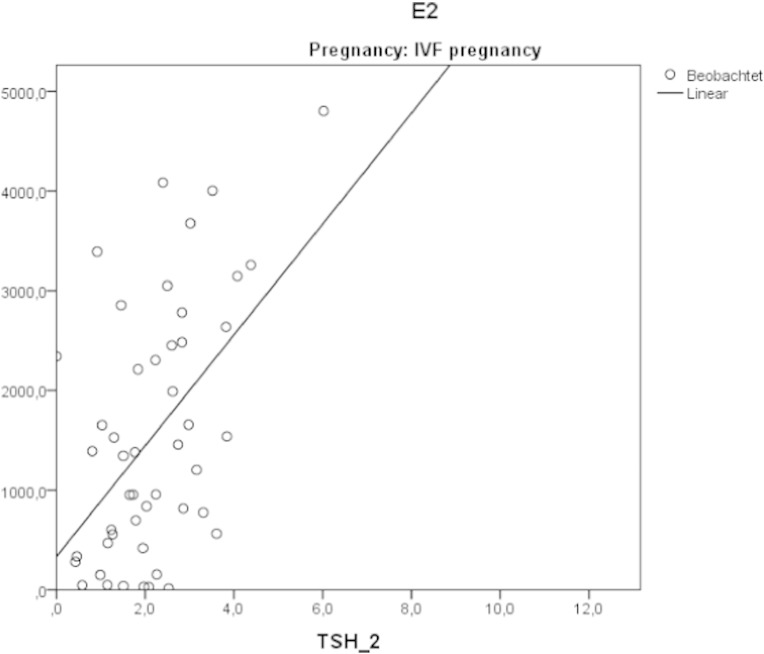

3.3.4. Correlation between estradiol and TSH levels in IVF-pos. and normal pregnancies

There was a positive correlation between E2 levels and follow-up TSH levels (r = 0.513, p < 0.001) in the IVF-pos. group. Such a relation was not seen in normal pregnancies (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between estradiol and TSH levels in the follow-up pregnancy sample. IVF pregnancies.

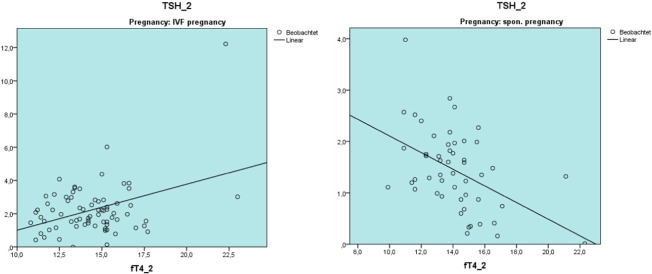

3.3.5. fT4, TSH magnesium and anti-Müllerian hormone levels after stimulation

At the early pregnancy time point the levels of fT4 levels showed a positive correlation with TSH levels in the IVF-pos. group. The opposite was observed in normal pregnancies. On the other hand fT3 levels showed a negative correlation to TSH_2 in both groups (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Different correlation patterns between fT4_2 and TSH_2 in IVF pregnancies and in spontaneous pregnancies.

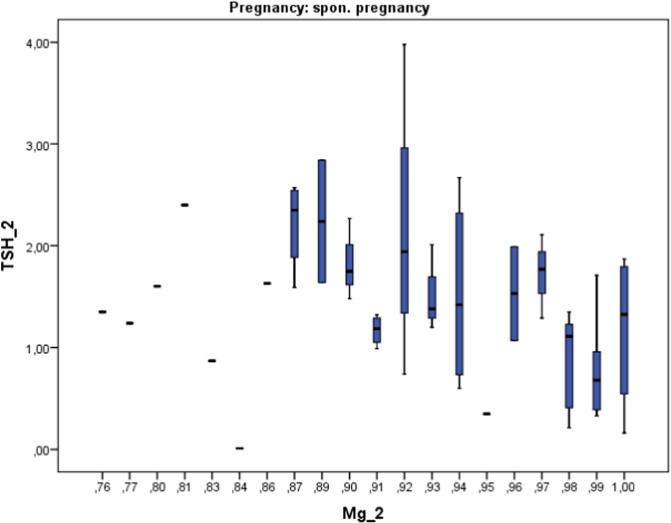

Combining the post-stimulation data on TSH and magnesium levels we observed a tendency toward lower increase of TSH levels with increasing magnesium concentration in the group of spontaneous pregnancies (Fig. 8). In the IVF-pos. group this tendency was not so apparent.

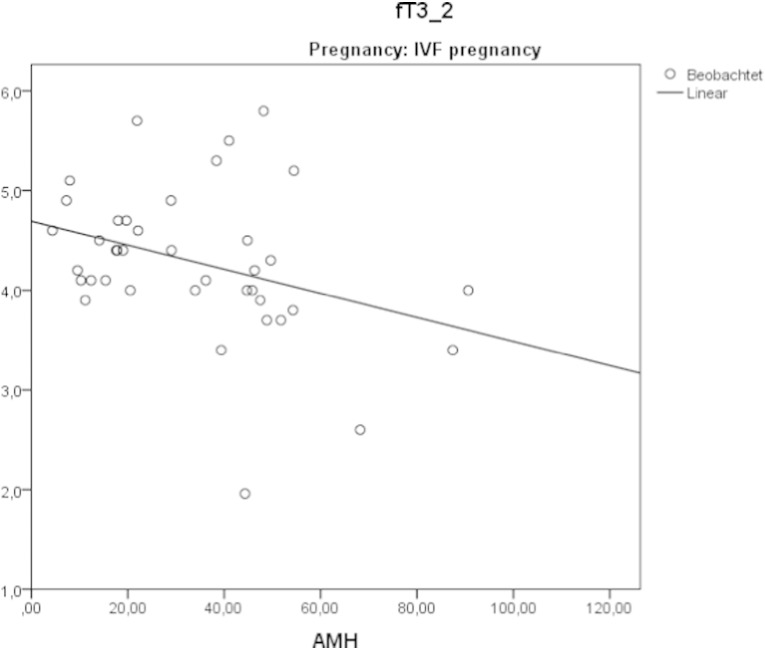

Fig. 8.

Negative correlation between anti-Müllerian hormone and fT3 in successful IVF pregnancies.

In the IVF-pos group a negative correlation between fT3 and anti-Müllerian hormone levels was observed. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels were found to correlate with the quality of follicles obtained (p = 0.008).

4. Discussion

4.1. Magnesium and IVF outcome

Our study reveals new physiological aspects related to ART procedures, thyroid function, magnesium, and pregnancy outcome. Successful IVF procedures were found to be associated with higher levels of magnesium in the basal serum sample. In early pregnancy magnesium levels fell significantly while TSH levels tended to increase in the IVF-pos. group. At the same time, an unexpected, previously not described physiological relation, i.e. a positive correlation, was found between fT4 and TSH which defies prevailing dogmas in Endocrinology. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels correlated to pregnancy success as expected [25]. A new finding is the negative correlation found between fT3 and anti-Müllerian hormone in the IVF-pos group. A lower TSH increase in cases of spontaneous pregnancies was observed to go along with higher magnesium levels.

Previous clinical studies have also dealt with the issue of fecundity and magnesium. In 2011 Bloom et al. looked at pre-conceptional concentrations of magnesium. The authors concluded that higher magnesium concentrations showed a trend toward an increased probability for pregnancy [26]. Similar results on the beneficial effects of selenium and magnesium supplementation in improving fecundity were reported already in 1994 [27]. These finding lend support to our observations.

4.2. Previous studies dealing with thyroid parameters and IVF

In the literature one can find some clinical studies that have had a similar design. In 2000 Muller et al. [28] described a drop of fT4 levels and an increase of TSH levels. These results contrast with the slight increase of fT4 which we have seen in IVF-pos and spontaneous pregnancies. The magnitude of TSH increase described by Muller was larger than the one we have observed. We believe that the results presented by Muller describe a heterogeneous population since the outcome of the ART procedure was not given. The lack of relevance of thyroid antibodies in relation to IVF success has been recently pointed out by Mintziori et al. [7]. The authors concluded that new insights into this subject are needed. Gracia et al. in 2012 [8] approached the question of changes in thyroid function following ART procedures. The initial TSH rise which they described was similar to the one we report here. The data displayed in Fig. 1, upper panel deserves a special comment. The graph describes increasing TSH levels in relation to thyroid peroxidase antibody status. The rise in TSH is greater in those with positive serology findings. Based on our own data on thyroid function and magnesium we hypothesize that those patients with positive serology could have suboptimal magnesium levels [15], [16]. In this paper we have shown the opposite effect of magnesium concentration on the subsequent TSH levels following ART (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Trends to lower TSH levels in relation to increasing magnesium levels in spontaneous pregnancies.

4.3. Estradiol and thyroid hormones

Our observations on serum estradiol levels and conception coincide with those made by Grebb et al. [29]. We can confirm the positive correlation between estradiol and TSH levels following as was described by Reinblatt [9]. Our data show a novel aspect of thyroid physiology, i.e. a positive correlation between fT4 and TSH in early pregnancy in the IVF-pos group. This situation can be seen as one of positive feedback between the pituitary and the thyroid. Factors leading to this regulatory switch could be the decrease of magnesium and the increase of estradiol levels as both can influence thyroid function [11], [13], [30], [31]. As a consequence we propose that the increase of TSH during early pregnancy following ART procedures could be considered to be a physiological adaptation and not an expression of hypothyroidism. This special situation is probably unique to IVF due to the supra-physiological condition being achieved in IVF.

Previous investigations have approached the question of thyroid function in the setting of ART and IVF. Several of these studies rely on the use of a recommended level of < 2.5 mIU/l for basal TSH which was termed “desirable” for pregnancy. In our clinical practice we consider this recommendation as being extremely critical since it comes from a consensus meeting where the authors attested that this value did not have sufficient clinical evidence [32]. Reh and coworkers have also looked critically at this “desirable” TSH level [33]. They stated in their conclusions that an increasing number of subjects would be falsely classified as being hypothyroid. In a similar way we have also commented recently on the inadequacy of such reference value [34]. Furthermore instituting thyroid hormone replacement alone has not been found to be effective to influence IVF outcome [35]. Quite recently other authors have also expressed similar opinions [36].

On energetic grounds mitochondrial biogenesis will require more thyroid hormone which will then be converted into triiodothyronine. Conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine in the cell requires sufficient selenium supply since the deiodinases are selenoproteins [37]. We hypothesize that the negative correlation seen between fT3 and anti-Müllerian hormone could be depicting a common process related to energy metabolism: high fT3 levels could compensate for lower anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations and vice versa. Unfortunately, we found no relevant literature on this topic.

4.4. Previous investigations on magnesium levels and IVF

Previous studies in humans have also shown a decrease of Mg levels during the IVF cycle [38]. In addition to this the authors found that magnesium levels in the follicular fluid were found to be higher than in serum [38]. O'Shaughnessy working with the determination of ionized cations showed that as estrogen levels rose, ionized magnesium levels fell [39]. It should be recalled that the choice to work with ionized magnesium determinations or not is an issue that depends on laboratory facilities. The method we have chosen is easily available.

The distribution of magnesium in ovarian follicles during ART has been shown by Silberstein et al. The authors proposed that the concentration of cations in the follicular fluid were the consequence of blood transudation where larger follicles had the highest levels of magnesium [40].

4.5. Hypothesis proposition: magnesium and telomerase in reproduction

What else can be of importance in face of low magnesium levels? There is now a fascinating answer to this question. The Alturas have demonstrated in 2014 that magnesium deficiency down regulates telomerase [41]. Connecting these findings one can find some relevant data on telomerase and ovarian function in the literature. In 2011 Chen et al. proposed an unknown factor to be regulating telomerase in granulosa cells. They speculated that telomerase could be related to testosterone [42]. On clinical grounds their clinical investigation showed that higher levels of telomerase were related to higher implantation and pregnancy rates (Fig. 2 in [42]). In a follow-up paper they discussed that telomerase activity is more important for the prediction of pregnancy after IVF [43]. One could interpret these results in the light of the findings of the Alturas [41]: sufficient magnesium ensures sufficient telomerase activity. Adding our results to this, we could also say that sufficient magnesium will maintain a normal thyroid function. High levels of anti-Müllerian hormone appear to be an independent prognostic factor.

5. Conclusions

In this present study we have observed that women with successful pregnancies have higher blood levels of magnesium. For this reason it appears sensible that magnesium levels should be optimized prior to ART. This has to be complemented by relaxation techniques that will reduce stress burden [14], [15]. Anti-Müllerian hormone appears to be an independent prognostic factor related to IVF success. Altogether we interpret the changes in thyroid function during early pregnancy following IVF as a regulatory mechanism oriented at maintaining mitochondrial biogenesis via thyroid hormones. The parallel increase of fT4 and TSH contradicts the general notion that it corresponds to hypothyroidism. Finally if our speculative hypothesis proposing a relation between magnesium and OXPHOS and telomerase can be confirmed, new perspectives in reproductive medicine will develop.

Abbreviations

- PBI

protein-bound iodine

- IVF

in-vitro fertilization

- fT4

free thyroxine

- fT3

free triiodothyronine

- TSH

thyroid stimulating hormone

- ICSI

intra cytoplasmatic sperm injection

- FSH

follicle stimulating hormone

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- TESE

testicular sperm extraction

- AMH

anti-Müllerian hormone

Contributions

All authors designed the study. IVF procedures were done by HM and SS. Thyroid examinations were conducted by RM. Data collection was done by SS. Statistical analysis was done by RM. The manuscript was written by RM. All authors approved the manuscript.

This study has been presented as a Master Thesis in order to fulfill the requirements for the degree of Master of Science M.Sc. (Clinical Embryology), University of Graz, Austria for SS in 2014.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Fantz C.R. Thyroid function during pregnancy. Clin. Chem. 1999;45:2250–2258. (PM:10585360) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katugampola S.L. The prevalence of goitre in pregnancy — a preliminary study. Ceylon J. Med. Sci. 1989;32:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillar T.M., Seitz H.J. Thyroid hormone and gene expression in the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory function. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1997;136:231–239. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1360231. (PM:9100544) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harper M.E., Seifert E.L. Thyroid hormone effects on mitochondrial energetics. Thyroid. 2008;18:145–156. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0250. (PM:18279015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters J.P. Pregnancy and the thyroid gland. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1948;20:449–463. (PM:18915667) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negro R. Levothyroxine treatment in thyroid peroxidase antibody-positive women undergoing assisted reproduction technologies: a prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20:1529–1533. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh843. (PM:15878930) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mintziori G. Association of TSH concentrations and thyroid autoimmunity with IVF outcome in women with TSH concentrations within normal adult range. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2014;77:84–88. doi: 10.1159/000357193. (PM:24356283) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gracia C.R. Thyroid function during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation as part of in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2012;97:585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.023. (PM:22260853) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinblatt S. Thyroid stimulating hormone levels rise after assisted reproductive technology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013;30:1347–1352. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0081-3. (PM:23955685) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benaglia L. Incidence of elevation of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014;173:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.11.003. (PM:24332278) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukai F., Murayama A. Association and dissociation of estrogen receptor with estrogen receptor-binding factors is regulated by Mg2 + J. Biochem. 1984;95:1227–1230. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134715. (PM:6746599) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basini G., Tamanini C. Selenium stimulates estradiol production in bovine granulosa cells: possible involvement of nitric oxide. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2000;18:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(99)00059-4. (PM:10701760) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaninovich A.A. Inhibition of thyroidal iodine release by oestrogens in euthyroid subjects. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh) 1982;99:386–392. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0990386. (PM:7072447) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Exploring the aspect of psychosomatics in hypothyroidism: the WOMED model of body–mind interactions based on musculoskeletal changes, psychological stressors, and low levels of magnesium. Woman Psychosom. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2014;1:1–11. ( http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213560X14000022) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. The WOMED model of benign thyroid disease: acquired magnesium deficiency due to physical and psychological stressors relates to dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation. BBA Clin. 2015;3:44–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Proof of Concept of the WOMED model of benign thyroid disease: restitution of thyroid morphology after correction of physical and psychological stressors and magnesium supplementation. BBA Clin. 2015;3:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coons C.M., Blunt K. The retention of nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium by pregnant women. J. Biol. Chem. 1930;86:1–16. ( http://www.jbc.org/content/86/1/1.full.pdf+html) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurley L.S. Teratogenic effects of magnesium deficiency in rats. J. Nutr. 1976;106:1254–1260. doi: 10.1093/jn/106.9.1254. (PM:956908) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F.L. Magnesium depletion during gestation and lactation in rats. J. Nutr. 1971;101:1201–1209. doi: 10.1093/jn/101.9.1201. (PM:5096139) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Günther T. Embryotoxic effects of magnesium deficiency and stress on rats and mice. Teratology. 1981;24:225–233. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420240213. (PM:7199766) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2000;284:3043–3045. (PM:11122593) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncayo R. The role of selenium, vitamin C, and zinc in benign thyroid diseases and of Se in malignant thyroid diseases: low selenium levels are found in subacute and silent thyroiditis and in papillary and follicular carcinoma. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-8-2. (PM:18221503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moncayo R., Moncayo H. Advanced 3D sonography of the thyroid: focus on vascularity. In: Thoirs K., editor. Sonography. Intech; 2012. pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rienzi L. The oocyte. Hum. Reprod. 2012;27(Suppl. 1):i2–i21. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des200. (PM:22811312) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kini S. Anti-mullerian hormone and cumulative pregnancy outcome in in-vitro fertilization. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2010;27:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9427-2. (PM:20467803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloom M.S. Associations between blood metals and fecundity among women residing in New York State. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011;31:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.09.013. (PM:20933593) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaren Howard J. Red cell magnesium and glutathione peroxidase in infertile women—effects of oral supplementation with magnesium and selenium. Magnes. Res. 1994;7:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller A.F. Decrease of free thyroxine levels after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;85:545–548. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6374. (PM:10690853) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greb R.R. Enhanced oestradiol secretion briefly after embryo transfer in conception cycles from IVF. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2004;9:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)62141-4. (PM:15353074) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphray H.P., Heaton F.W. Relationship between the thyroid hormone and mineral metabolism in the rat. J. Endocrinol. 1972;53:113–123. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0530113. (PM:5021254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaton F.W., Humphray H.P. Effect of magnesium status on thyroid activity and iodide metabolism. J. Endocrinol. 1974;61:53–61. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0610053. (PM:4133501) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abalovich M. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92(8 Suppl):s1–s47. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0141. (PM:17948378) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reh A. What is a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level? Effects of stricter TSH thresholds on pregnancy outcomes after in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2010;94:2920–2922. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.041. (PM:20655528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moncayo H., Moncayo R. The lack of clinical congruence in diagnosis and research in relation to subclinical hypothyroidism. Fertil. Steril. 2014;101:e30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.010. (PM:24534287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scoccia B. In vitro fertilization pregnancy rates in levothyroxine-treated women with hypothyroidism compared to women without thyroid dysfunction disorders. Thyroid. 2012;22:631–636. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0343. (PM:22540326) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghahosseini M. Effects of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) level on clinical pregnancy rate via In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) procedure. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 2014;28:46. (PM:25405112) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu J., Holmgren A. Selenoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;284:723–727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800045200. (PM:18757362) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azem F. Divalent cation levels in serum and preovulatory follicular fluid of women undergoing in vitro fertilization embryo transfer. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2004;57:86–89. doi: 10.1159/000075383. (PM:14671416) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Shaughnessy A. Circulating divalent cations in asymptomatic ovarian hyperstimulation and in vitro fertilization patients. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2001;52:237–242. doi: 10.1159/000052982. (PM:11729336) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silberstein T. Trace element concentrations in follicular fluid of small follicles differ from those in blood serum, and may represent long-term exposure. Fertil. Steril. 2009;91:1771–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.007. (PM:18423455) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah N.C. Short-term magnesium deficiency downregulates telomerase, upregulates neutral sphingomyelinase and induces oxidative DNA damage in cardiovascular tissues: relevance to atherogenesis, cardiovascular diseases and aging. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014;7:497–514. (PM:24753742) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H. Women with high telomerase activity in luteinised granulosa cells have a higher pregnancy rate during in vitro fertilisation treatment. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011;28:797–807. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9600-2. (PM:21717175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W. Telomerase activity is more significant for predicting the outcome of IVF treatment than telomere length in granulosa cells. Reproduction. 2014;147:649–657. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0223. (PM:24472817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.