Abstract

Background

Nadroparin is used during hemodialysis to prevent clotting of the extra corporeal system. During nocturnal hemodialysis patients receive an increased dosage of nadroparin compared to conventional hemodialysis. We tested whether the prescribed dosage regimen of nadroparin, according to Dutch guidelines, causes accumulation of nadroparin.

Methods

Anti-Xa levels were used as an indicator of nadroparin accumulation. Anti-Xa was measured photometrically in 13 patients undergoing nocturnal hemodialysis for 4 nights a week. Nadroparin was administered according to Dutch dosage guidelines. We assessed anti-Xa levels at 4 time points during 1 dialysis week: before the start of the first dialysis session of the week (baseline), prior to (T1) and after the last dialysis session of the week (T2) and before the first dialysis of the following week (T3).

Results

Patients received 71–95 IU/kg at the start of dialysis and another 50% of the initial dosage after 4 h with a total cumulative dosage of 128 ± 24 IU/kg. Anti-Xa levels increased from 0.017 at baseline to 0.019 at T1 (p = 0.03). Anti-Xa levels were 0.419 ± 0.252 IU/ml at T2 (p < 0.001 vs baseline and T1), whereas anti-Xa levels were not changed at T3 compared to baseline.

Conclusion

Dosing of nadroparin according to Dutch guidelines in patients on nocturnal hemodialysis does not lead to accumulation of nadroparin. We therefore consider the Dutch dosage guidelines for nadroparin an effective and safe strategy.

General significance

This article is the first to present data on anti-Xa activity during nocturnal hemodialysis which is a widely used and potentially dangerous therapy.

Keywords: Anti-Xa, Low molecular weight heparin, Nadroparin, Nocturnal hemodialysis

Highlights

-

•

Higher dosages of nadroparin are administered during nocturnal hemodialysis.

-

•

Nadroparin can accumulate which leads to an increased bleeding risk.

-

•

We examined accumulation of nadroparin during nocturnal hemodialysis by measuring anti-Xa levels.

-

•

Accumulation of nadroparin does not occur during nocturnal hemodialysis.

-

•

Dutch guidelines for dosage of nadroparin in nocturnal hemodialysis are safe.

1. Introduction

Nocturnal in-centre hemodialysis (NCD) has become a treatment option with advantages for patients. Due to longer dialysis time and increased dialysis frequency, nocturnal hemodialysis raises quality of life and lowers mortality [1], [2]. To prevent clotting of the extra-corporeal system low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), nadroparin or dalteparin, is used preferably in the Netherlands. These fragments of heparin are safe and effective in preventing blood clots in the artificial kidney during conventional hemodialysis [3], [4]. However, dosing regimens of LMWHs are rarely studied. Differences in thrombogenicity of artificial kidneys [5], differences in drug clearance between LMWHs [6] and concomitant treatment with oral anticoagulation may influence the accuracy of LMWH treatment during hemodialysis. During nocturnal hemodialysis, patients are given a dosage that is at least 50% higher than in conventional hemodialysis. The higher dosage is also given four times a week compared to three times a week in conventional hemodialysis, leading to a substantially higher weekly dosage. Nadroparin is mostly cleared renally, so no significant clearance is expected in patients with no or minimal residual renal function. This may lead to accumulation of nadroparin. Patients undergoing dialysis already have a mildly elevated risk of bleeding due to uraemia. The elevated levels of urea cause a platelet dysfunction and an impaired interaction between platelets and the vessel wall [7]. This increased risk of bleeding is only partially restored by hemodialysis [8]. Should accumulation of nadroparin occur, this becomes another risk factor for major bleeding in patients who already have an increased bleeding risk [3], [9]. Bleeding due to nadroparin overdosage can only partially be corrected using protamine [10], [11].

In general, LMWHs are not cleared by the dialysis membrane [12]. Data on pharmacokinetics or accumulation of nadroparin or other LMWHs during nocturnal hemodialysis are not available [6]. Contrary to conventional heparin, the activity of nadroparin cannot be measured by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). The degree of anticoagulatory effect should be measured by anti-Xa activity [13], [14]. Reference values for anti-Xa activity are being described for treatment of venous thrombosis and are only available for patients with normal renal function. Reference values are depicted as peak values 4-h after subcutaneous injection. Reference values for intravenous injection are not available, and neither is the time at which peak values occur after intravenous injection.

The aim of this study is to determine whether the prescribed dosage regimen of nadroparin during nocturnal hemodialysis leads to accumulation of nadroparin measured by anti-Xa levels.

2. Material and methods

All patients, older than 18 years on a nocturnal hemodialysis schedule of 4 times 8 h a week, in our dialysis clinic (n = 13) were included after written informed consent was given. Patients using factor-Xa inhibitors other than nadroparin were excluded. Patients with active bleeding and/or changes in anticoagulant agents during the study were excluded. The hospital research and ethics committee has reviewed and approved the protocol.

The starting dosage recommended according to the Dutch guidelines of the Federation of Nephrology is 57–76 IU/kg for conventional hemodialysis. For nocturnal hemodialysis the guidelines recommend a second dosage of 50% of the initial dosage [15]. Dosage adjustments are made on clinical empirical grounds rather than by functional tests. Dosage LMWH will be raised when clotting occurs and lowered when the needle site is bleeding excessively [5]. In our patients on nocturnal hemodialysis treatment, nadroparin treatment was given according to these guidelines.

Anti-Xa levels taken prior to the next administration of nadroparin are the best way to assess accumulation [16], [17]. The 4 dialysis sessions were on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday night. Blood samples for anti-Xa measurements were taken 4 times in one week of dialysis: before the first dialysis of the week (baseline), prior to (T1) and after the fourth dialysis session of the week (T2), and before the first dialysis of the following week (T3). Samples were processed within 30 min and frozen at − 80 °C. Analysis was done after all samples were received. Frozen samples stay stable for several months [18]. Anti-Xa levels were measured photometrically using a chromogenic technique (ACL top, Instrumentation Laboratory). Dialysis data, medical history and standardized monthly laboratory testing were also reviewed. Statistical analysis was done using a t-test, a paired two-sample t-test and linear regression analysis. A multivariable linear regression analysis was used to analyse the influence of nadroparin dosage, Ktv, and acenocoumarol use on ∆T2–T1 although this test is limited by small sample size. In the analysis of ∆T2–T1, one patient was excluded due to a shorter than normal dialysis duration during this measurement. Results are shown as mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

All patients were on single needle dialysis with blood flow of 150 ml/min and dialysate flow of 300 ml/min. The FX100 (Fresenius) artificial kidney is used on all patients. Characteristics of the 13 included patients are shown in Table 1. Patients already had nocturnal hemodialysis treatment for 2 years. Only 3 patients had residual renal function. Monthly laboratory testing results before and after the study period are shown in Table 2. Although a statistically significant change in sodium levels was observed (p = 0.02), the sodium levels remained within the normal range. Phosphate levels were also different (p = 0.02). Thrombocyte counts of all patients were within normal range (mean 189, min 147 – max 253 × 109/l). Medical history revealed bleeding complications in 2 patients, more than one year before this study, with one case of gastro-intestinal bleeding from colonic polyps and one cyst bleeding in a polycystic kidney. No thrombo-embolic events were registered in any of the patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57 (7) |

| Dosage nadroparine/dialysis (IU) | 10,962 (3504) |

| Dosage nadroparine/kg/dialysis (IU/kg) | 128 (24) |

| Total Kt/v | 5.58 (1.17) |

| Residual Kt/v | 0.0223 (0.05) |

| Dialysis duration (min) | 469 (24) |

| Ultrafiltration (ml) | 1528 (773) |

| Total time on HD (months) | 41 (33) |

| Time on NCD (months) | 25 (29) |

| INR acenocoumarol users (n = 5) | 3.27 (1.41) |

| INR non acenocoumarol users (n = 8) | 1.01 (0.10) |

Table 2.

Laboratory values 2–4 weeks previous to anti-Xa measurements and 2–4 weeks after anti-Xa measurements.

| Pre-study (SD) | Post-study (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (mmol/l) | 7.2 (0.7) | 7.5 (0.7) |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 20.4 (3.2) | 19.8 (2.4) |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 140 (2) | 138 (3) |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 5.0 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.4) |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 885 (197) | 863 (149) |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 23 (5) | 24 (5) |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 2.27 (0.14) | 2.23 (.13) |

| Phosphate (mmol/l) | 1.45 (0.33) | 1.70 (0.32) |

| Albumin (g/l) | 36 (3) | 37 (3) |

3.2. Dosage of nadroparin

The mean dose of nadroparin was 128 ± 24 IU/kg/dialysis. There are 5 patients who were using acenocoumarol. The International Normalized Ratio (INR) of these patients is shown in Table 1. Three of the patients have artificial valves which explains the high INR. However the INR stayed within the intended range for all patients. The dose of nadroparin in this group is 28 IU/kg/dialysis lower compared to the 8 patients not using acenocoumarol (111 ± 15 IU vs 139 ± 22 IU/kg/dialysis; p = 0.03).

3.3. Anti-Xa activity

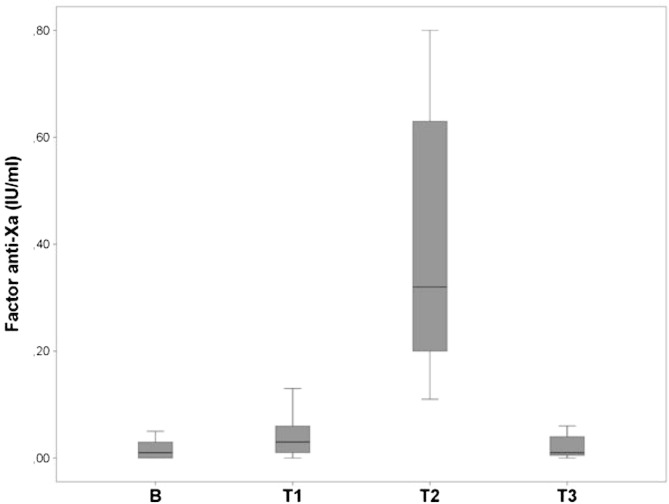

Anti-Xa activity at baseline (B) was 0.017 ± 0.02 IU/ml. At T1, anti-Xa activity was raised by 0.02 IU/ml compared to B (0.04 ± 0.04 vs 0.017 ± 0.02 IU/ml; p = 0.03). Anti-Xa activity at T2 was raised by 0.36 IU/ml compared to T1 (0.40 ± 0.25 vs 0.04 ± 0.04 IU/ml; p < 0.001). Levels of anti-Xa activity at T3 (0.02 ± 0.02 IU/ml) were not different from B (p = 0.77). Data shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Anti-Xa levels (IU/ml) at baseline (B), T1, T2 and T3.

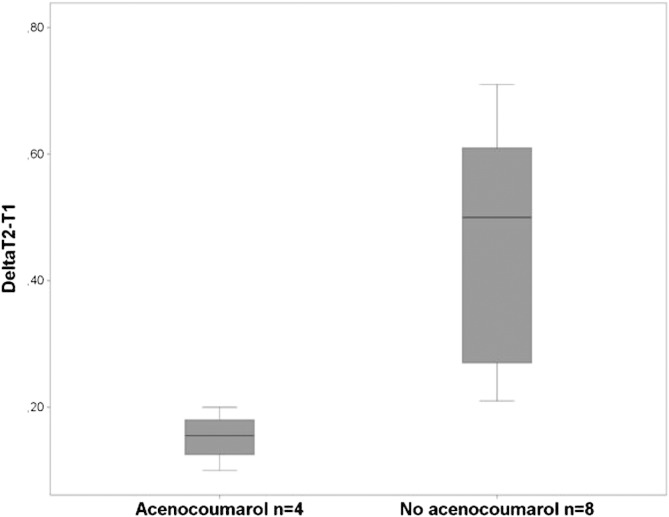

Multivariable linear regression analysis showed no significant association. Acenocoumarol use and dosage of nadroparin/kg were univariably predicting the variation of ∆T2–T1 (p = 0.02). Patients using acenocoumarol have a ∆T2–T1 of 0.31 IU/ml lower compared to patients not using acenocoumarol (0.15 ± 0.4 IU/ml vs 0.46 ± 0.2 IU/ml; p = 0.002). Data shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Delta T2-T1 (IU/ml) for patient using acenocoumarol and patients not on acenocoumarol.

3.4. Clinical observation

All 13 patients followed the prescribed dialysis schedule. During measurements, no changes were made in dialysis prescriptions or anticoagulation treatment. No bleeding complications nor thrombo-embolic events were observed during the study week. Lines and the artificial membrane were checked for clotting after dialysis. On one occasion a small blood clot was detected in the extracorporeal system at the end of dialysis. There were no consequences for further dialysis treatment or medication.

4. Discussion

Our patient population had an efficient nocturnal dialysis treatment and were clinically and biochemically stable. In this study, we demonstrated that compared to daytime hemodialysis, higher dosages of nadroparin during nocturnal hemodialysis do not lead to accumulation of nadroparin as measured by anti-Xa levels, since the anti-Xa levels at the start of two consecutive dialysis weeks (baseline and T3) were similar.

There was also no accumulation within a dialysis week, since anti-Xa activity showed no clinically relevant increase previous to the last dialysis of the week (baseline and T1). This is the moment with the shortest interval between the two following dialysis sessions, after three dialysis sessions in the study week, and thus with the highest expected risk of accumulation. The highest anti-Xa at this time interval was 0.13 IU/ml, but these levels of anti-Xa activity are not associated with a significant anticoagulation effect. Our data are in accordance with data of Stefoni et al. who showed that there is no anti-Xa activity of nadroparin 20 h after conventional hemodialysis, when administered as a bolus of 65 IU/kg [19]. Since there was no accumulation of anti-Xa activity during our study, this suggests that non-renal mechanisms lead to clearance of nadroparin in hemodialysis patients.

The exact time point at which the lowest anti-Xa levels are reached cannot be estimated from our study, as this would have required frequent measurements at shorter intervals following dialysis. These additional measurements are also needed to determine the half-life of nadroparin in nocturnal hemodialysis patients. No reliable half-life time could be calculated using our measurements because too many patients had undetectable anti-Xa levels at T3.

Anti-Xa activity after the last (4th) dialysis session (T2) in the study week was significantly elevated, 0.4 IU/ml with a wide range (± 0.25), in comparison to the start of that dialysis session (T1). This shows that nadroparin was effectively administered in all patients. The dosage of nadroparin/kg and the use of acenocoumarol are both significantly related with the change in anti-Xa activity during a dialysis session. In acenocoumarol users, the ∆T2–T1 was 0.31 IU/ml lower in comparison to patients without acenocoumarol. This is a consequence of the significantly lower dosage of nadroparin (− 20%) in the acenocoumarol group. All acenocoumarol users received the lowest starting dose of 8550 IU. Whether this dose can be further lowered is not clear and should be further investigated. Previous studies showed that LMWH dosages can be lowered safely in conventional hemodialysis [20], [21]. The group of patients without acenocoumarol used 139 IU/kg nadroparin, whereas the guideline recommends a total dose of 114 IU/kg for patients on NCD above 50 kg. This recommended dose seems to be the minimum dose for patients not using acenocoumarol, but is empirically raised in most patients when clotting of the extra corporeal system occurs.We observed no thrombo-embolic events or bleeding events in our patients in accordance with the results on anti-Xa activity. Only 1 small clot in the extracorporeal system was detected. An analysis of our patients' history since the start of NCD shows that two bleeding events and no thrombo-embolic event occurred in our population. The used dosage regimen, according to the guidelines, seems safe and effective in our population. Although our study population is small, it is similar to larger populations in the literature in terms of patient characteristics and biochemical characteristics [22].

In this study sample times were chosen to assess whether accumulation occurs. This means that our data do not compare with anti-Xa data during therapeutic dosing of LMWH, since these latter ranges are set as peak levels 4 h after subcutaneous injection in patients with normal kidney function. No data on intravenous administration in hemodialysis nor therapeutic ranges for patients with kidney failure are available. The clinical value of anti-Xa activity measurement is disputable. Dosage adjustments are made empirically and considered safe in conventional hemodialysis [3], [4]. Our study shows that patients on nocturnal hemodialysis receiving nadroparin in accordance with Dutch guidelines show no accumulation of nadroparin. Therefore, we conclude that it is not necessary to determine anti-Xa levels on a routine manner in a stable hemodialysis setting.

In conclusion, there is no risk of accumulation of nadroparin in patients on nocturnal, in-centre hemodialysis treatment who receive a cumulative weekly dosage of nadroparin twice as high compared to patients on conventional hemodialysis. The used dosage is effective in preventing clotting of the extracorporeal system and not associated with risk as no major bleeding events occurred in our population.

Disclosure of grants

This study is sponsored by the Medical Centre Leeuwarden (Grant number: 2013.10-01).

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank dr. H. de Wit, clinical chemist, Medical Centre Leeuwarden for performing anti-Xa activity measurements

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

Contributor Information

Edward Buitenwerf, Email: e.buitenwerf@gmail.com.

Arne J. Risselada, Email: arnejouke@gmail.com.

Eric N. van Roon, Email: E.N.van.Roon@ZNB.NL.

Nic J.G.M. Veeger, Email: nic.veeger@ZNB.NL.

Marc H. Hemmelder, Email: m.h.hemmelder@znb.nl.

References

- 1.Culleton B.F., Asola M.R. The impact of short daily and nocturnal hemodialysis on quality of life, cardiovascular risk and survival. J. Nephrol. 2011;24:405–415. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.8422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chazot C., Ok E., Lacson E. Trice-weekly nocturnal hemodialysis: the overlooked alternative to improve patient outcomes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim W., Cook D.J., Crowther M.A. Safety and efficacy of low molecular weight heparins for hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal failure: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:3192–3206. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000145014.80714.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer K.G. Essentials of anticoagulation in hemodialysis. Hemodial. Int. 2007;11:178–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suranyi M., Chow J.S. Review: anticoagulation for haemodialysis. Nephrology. 2010;15:386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid P., Fischer A.G., Wuillemin W.A. Low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with renal insufficiency. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2009;139:438–452. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.11284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberst M.E., Berkowitz L.R. Hemostasis and renal failure: pathophysioglogy and management. Am. J. Med. 1994;96:168. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Minno G., Martinez J. Platelet dysfunction in uremia. Multifaceted defect partially corrected by dialysis. Am. J. Med. 1985;79:552. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim W., Dentali F., Eikelboom J.W., Crowther M.A. Meta-analysis: low-molecular-weight heparin and bleeding in patients with severe renal insufficiency. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;144:673–684. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doutremepuich C., Bonini F. In vivo neutralization of low molecular weight heparin fraction CY 216 by protamine. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 1985;11:318. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bang C.J., Berstad A., Talstad I. Incomplete reversal of enoxaparin-induced bleeding by protamine sulfate. Haemostasis. 1991;21:155. doi: 10.1159/000216220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ljungberg B., Jacobson S.H., Lins L.E., Pejler G. Effective anticoagulation by a low molecular weight heparin in hemodialysis with a highly permeable polysulfone membrane. Clin. Nephrol. 1992;38:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrader J., Stibbe W., Kandt M. Low molecular weight heparin versus standard heparin. A long-term study in hemodialysis and hemofiltration patients. ASAIO Trans. 1990;36:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polkinghome K.R., McMahon L.P., Becker G.J. Pharmocokinetic studies of deltaparin (Fragmin), enoxaparin (Clexane) and danaparoid sodium (Orgaran) in stable chronic hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002;40:990–995. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.36331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nederlandse federatie voor Nefrologie richtlijn Antistolling bij hemodialyse. 2012. http://www.nefro.nl/uploads/Xg/1r/Xg1rqS6RM2dmgcMmhnq0mA/Antistolling-bij-HD-2012-update-febr-2013.pdf Available at: (Consulted 2013, September 11)

- 16.Ma J.M., Jackevicius C.A., Yeo E. Anti-Xa monitoring of enoxaparin for acute coronary syndromes in patients with renal disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004;38:1576–1581. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutescu E.A., Spinler S.A., Wittkowsky A., Dager W.E. Low-molecular weight heparins in renal impairment and obesity: available evidence and clinical practice recommendations across medical and surgical settings. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009;43:1064–1082. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization: use of anticoagulants in diagnostic laboratory investigation. 2002. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_DIL_LAB_99.1_Rev.2.pdf Available at:

- 19.Stefoni S., Cianciolo G., Donati G. Standard heparin versus low-molecular-weight heparin. A medium-term comparison in hemodialysis. Nephron. 2002;92:589–600. doi: 10.1159/000064086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sain M., Kovacic V., Radic J. What are the lowest doses of low molecular weight heparin for effective and safe hemodialysis in different subgroups of patients? Ther. Apher. Dial. 2014;18:208–209. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sain M., Ljutic D., Kovacic V. The individually optimized bolus dose of nadroparin is safe and effective in diabetic and nondiabetic patients with bleeding risk on hemodialysis. Hemodial. Int. 2011;12 doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ok E., Duman S., Asci G. Comparison of 4- and 8-h dialysis sessions in Thrice-weekly in-centre haemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011;26:1287–1296. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.