Abstract

Pediatricians play a key role in the healthy development of children. Nevertheless, the practice patterns of pediatricians have seldom been investigated. The current study analyzed the nationwide profiles of ambulatory visits to pediatricians in Taiwan, using the National Health Insurance Research Database. From a dataset that was randomly sampled one out of every 500 records among a total of 309,880,000 visits in 2012 in the country, 9.8% (n = 60,717) of the visits were found paid to pediatricians. Children and adolescents accounted for only 69.3% of the visits to pediatricians. Male pediatricians provided 80.5% of the services and the main workforces were those aged 40–49 years. The most frequent diagnoses were respiratory tract diseases (64.7%) and anti-histamine agents were prescribed in 48.8% of the visits to pediatricians. Our detailed results could contribute to evidence-based discussions on health policymaking.

Keywords: Pediatricians, national health insurance, ambulatory visits

1. Introduction

Pediatricians play a requisite role in child and adolescent health care, including providing neonatal care, managing congenital or developmental abnormalities and pediatric diseases. Since it was established approximately 200 years ago, the specialty has continued to develop into a well-rounded and unique subset of knowledge-based content [1]. In Taiwan, the child health care indices are as good as they are in the USA in the aspects such as newborn mortality, infant mortality, under-5 mortality, and the mortality of the population aged 1 to 18 years [2]. However, Taiwan has also become and ranked among the lowest fertility countries in recent decades, synchronizing with the global trend in the decline of fertility rates [3]. The turning point came in 1984 when Taiwan first experienced that total fertility rates (TFR) went lower than the replacement level. Taiwan’s TFR decreased further from 1.80 to 0.89 between 1990 and 2010, which inevitably impacted on the pediatricians, not to mention that pediatricians also have to compete with other specialists such as family medicine specialists and otorhinolaryngologists [4]. In the United States, a National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) has been conducted to survey who were providing care to America’s children [5] as well as the antimicrobial prescribing patterns for children [6,7,8,9]. The research on the antimicrobials prescribed by pediatricians have also been reported in some other countries [10,11,12]. In Taiwan, a previous study had investigated the role of pediatricians for children during 1999 to 2011 [13], and another one studied the common diagnosis in 2009 by collecting data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) [14]. Nevertheless, in many countries, including Taiwan, a nationwide survey on the demographic data of pediatricians and their practicing patterns is still lacking.

The current study aimed to study the characteristics of ambulatory visits to pediatricians on a nationwide base retrieving the record from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system in 2012. The variables analyzed included ages and genders of both patients and physicians, the procedures conducted, the diagnoses made, and the medications prescribed during these visits. The findings may present valuable information for future healthcare policymaking, and may deed as a comparison for longitudinal researches.

2. Methods

2.1. Database

The NHI program starting from 1995 in Taiwan has offered comprehensive health care to cover more than 99% of the country's residents. The National Health Insurance Administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare has released all the de-identified claims data traced back to 1999 for academic research in the form of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) [15]. The conduct of the study had been approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (2013-04-005E). Because of anonymized data that are publicly available on application, our study is exempt from full IRB review.

2.2. Study Population

We performed the descriptive and cross-sectional study by accessing the files sampled from those of the year 2012 (S_CD20120.DAT and S_OO20120.DAT of NHIRD). The dataset “CD” means collection of all the outpatient visit files, on the other hand, the dataset "OO" refers to the outpatient order files. These two collections of files, containing a total of 619,760 medical records, were acquired by a 0.2% sampling ratio from the CD and OO datasets for 2012, excluding dentistry and traditional Chinese medicine. Each record comprised the patient’s identification number, sex, birth date, date of consultation, medical facility, the specialty of the physician consulted, and up to three diagnosis codes as defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

The details of the medical records of 60,717 ambulatory visits to pediatricians were unpacked for analysis. The National Health Insurance Administration also listed reimbursable drugs with additional coding in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [16]. The basic data of the contracted medical care institutions offered the status of accreditation: academic medical center, metropolitan hospital, local community hospital, or physician clinic. The diagnoses, procedures and prescriptions of medications made during the visits were analyzed and compared among different levels of hospitals or clinics.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The programming software Perl version 5.20.2 was used for data processing, and then regular descriptive statistics were displayed.

3. Results

Of the 619,760 ambulatory visits collected in 2012, 9.8% (n = 60,717) were attended by pediatricians—ranking the fourth among all the physician specialties (Table 1). Pediatricians took charge of 5.1% of insurance cost claimed, amounting to an estimate of NT$309 billion.

Table 1.

Ambulatory visits covered by Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012, stratified by specialty (sampling rate: 1/500).

| Specialty | Number of Visits (%) | Cost Claimed (%) | Average Cost Claimed per Visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family medicine | 116,551 (18.8) | 51,157,561 (8.3) | 439 |

| Internal medicine | 70,615 (11.4) | 42,547,879 (6.9) | 602 |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 67,881 (11.0) | 29,718,395 (4.8) | 438 |

| Pediatrics | 60,717 (9.8) | 31,574,986 (5.1) | 520 |

| Ophthalmology | 37,692 (6.1) | 25,422,291 (4.1) | 674 |

| Obstetrics& Gynecology | 35,697 (5.8) | 19,674,700 (3.2) | 551 |

| Others | 230,607 (37.2) | 418,023,780 (67.6) | 1813 |

| Total | 619,760 (100.0) * | 618,119,592 (100.0) | 997 |

* The percentage of the ambulatory visits and cost claimed by specialty had been rounded, therefore the % in each of the table didn’t give a total of 100% just.

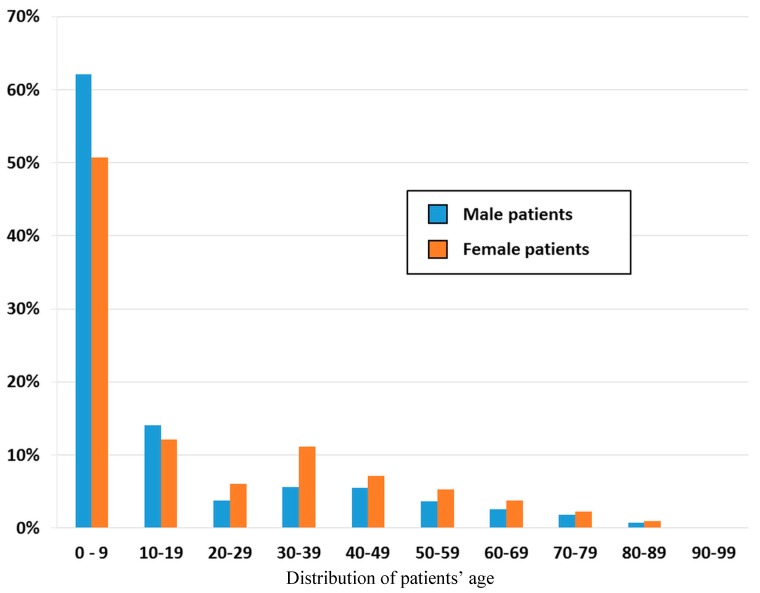

Among the patients paying the ambulatory visits to pediatricians, 52% were male, and 48% were female. Stratifying the data by age group we found that the group of patients aged 0–10 years accounted for the highest proportion (56.2%, n = 34,111) of ambulatory visits to pediatricians in both genders (male: 62.1%, n = 18,089; female: 50.7%, n = 16,022), followed by the patients aged 10–19 years (13.1%, n = 7963) in both genders (male: 14.1%, n = 4118; female: 12.1%, n = 3845). Children and adolescents accounted for nearly seventy percent (69.3%) of the ambulatory visits to pediatricians, while the other older groups, ≥20 years of age, accounted for 30.7% (n = 18,643) of the visits. There were more visits paid by female patients than by male patients (female, n = 11,712; male, n = 6931) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age and sex distribution of the patients who visited pediatricians, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500).

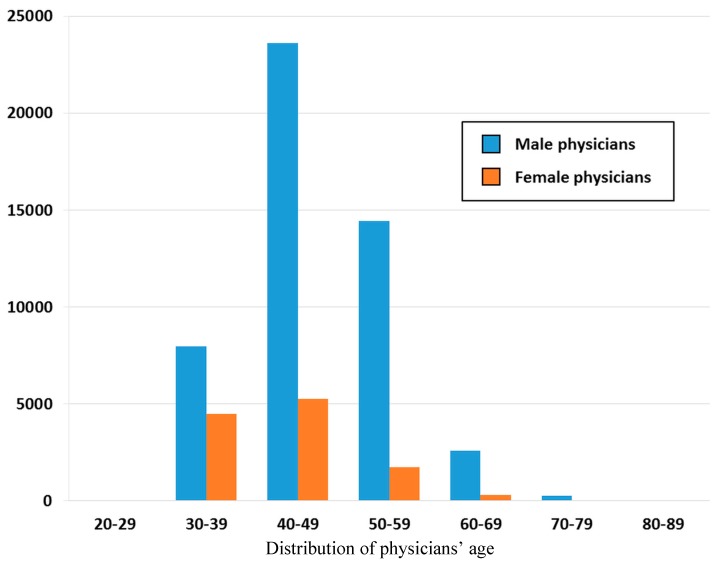

The number of ambulatory visits in reference to the pediatricians’ gender and age is presented in Figure 2. The patients, at whatever age groups, showed to pay more visits to male pediatricians than to female pediatricians. The pediatricians aged 40–49 years, in both genders, attended to the highest proportion of ambulatory visits (male = 23,603, female = 5255), as compared with the other age groups of pediatricians. There were fewer pediatricians in the male group aged 30–39 years (n = 7954), as compared with the same gender group of pediatricians aged 40–49 (n = 25,603) and 50–59 years (n = 14,433).

Figure 2.

Age and sex distribution of pediatricians, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500).

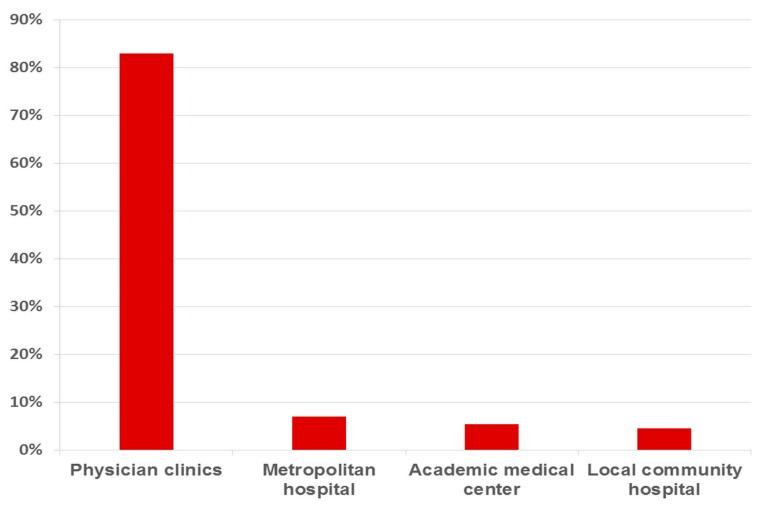

This study showed that practitioners remained the most important ambulatory care providers and managed 83.0% (n = 50,448) of the ambulatory care visits made by pediatricians (n = 60,717) from 619,760 sampled ambulatory visits in Taiwan, followed by metropolitan hospitals (7.0%, n = 4194), academic medical centers (5.4%), and local community hospitals (4.6%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pediatricians’ affiliation, stratified according to healthcare facility accreditation, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500).

We further analyzed the age distribution of the physicians, stratified in accordance with healthcare facility accreditation (Table 2). The ambulatory visits in the clinics were managed mostly by the physicians aged 40–49 years (n = 24,559), followed in frequency by the 50–59 years group (n = 13,758). In the academic medical centers, however, physicians aged 40–49 (n = 1321) and 50–59 (n = 1104) years showed to have managed similar numbers of ambulatory visits.

Table 2.

Pediatricians’ age affiliation, stratified according to healthcare facility accreditation, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500).

| Facility Level | 20–29 Years | 30–39 Years | 40–49 Years | 50–59 Years | 60–69 Years | 70–79 Years | 80–89 Years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician clinics | 20 | 9538 | 24,559 | 13,758 | 2307 | 251 | 12 | 50,448 * |

| Local community hospital | 3 | 827 | 1223 | 578 | 167 | 25 | 2 | 2825 |

| Metropolitan hospital | 7 | 1525 | 1755 | 734 | 171 | 0 | 2 | 4194 |

| Academic medical center | 21 | 545 | 1321 | 1104 | 240 | 19 | 0 | 3250 |

| Total | 51 | 12,435 | 28,858 | 16,174 | 2885 | 295 | 16 | 60,717 |

* There were three “unknown” in the physician clinics.

Among the ambulatory visits to pediatricians, 65.9% (n = 40,014) produced only one diagnosis. According to the major disease category, respiratory diseases were the most frequently coded diagnostic group (n = 39,305, 64.7%), followed by non-specific symptoms and signs, and other ill-defined conditions (n = 4872, 8.0%). The first diagnosis code in every medical record was analyzed and assembled into a list of the top 10 most common diagnosis groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ambulatory visits to pediatricians, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012, stratified by disease group and hospital level (sampling rate: 1/500, the percentage of diagnoses had been rounded).

| ICD9CM * | Diagnosis Group | Total N = 60,717 | Academic Medical Center N = 3250 | Metropolitan Hospital N = 4194 | Local Community Hospital N = 2825 | Physicians Clinics N = 50,448 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 465 | Acute upper respiratory infections | 13,461 (22.2) | 104 (0.2) | 287 (0.5) | 271 (0.5) | 12,799 (21.0) |

| 466 | Acute bronchitis & bronchiolitis | 7041 (11.6) | 121 (0.2) | 469 (0.8) | 348 (0.6) | 6103 (10.1) |

| 461 | Acute sinusitis | 3072 (5.1) | 58 (0.1) | 120 (0.2) | 86 (0.1) | 2808 (4.6) |

| 463 | Acute tonsilitis | 3030 (5.0) | 37 (0.1) | 163 (0.3) | 112 (0.2) | 2718 (4.5) |

| 460 | Acute nasopharyngitis | 2597 (4.3) | 13 (0.0) ** | 34 (0.1) | 33 (0.1) | 2517 (4.1) |

| 462 | Acute pharyngitis | 2580 (4.2) | 52 (0.1) | 118 (0.2) | 146 (0.2) | 2264 (3.7) |

| 558 | Other noninfectious gastroenteritis and colitis | 2032 (3.3) | 58 (0.1) | 120 (0.2) | 61 (0.1) | 1793 (2.9) |

| 464 | Acute laryngitis & tracheitis | 1688 (2.8) | 9 (0.0) ** | 20 (0.0) ** | 17 (0.0) ** | 1642 (2.7) |

| V20 | Health supervision of infant or child | 1644 (2.7) | 121 (0.2) | 239 (0.4) | 301 (0.5) | 983 (1.6) |

| 780 | Non-specific symptoms | 1544 (2.5) | 68 (0.1) | 170 (0.3) | 94 (0.2) | 1212 (2.0) |

* The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ** The value that had been rounded still less than 0.001 (0.1%).

Acute upper respiratory infection was the most common diagnosis (22.2%), followed in frequency by acute bronchitis & bronchiolitis (11.6%), acute sinusitis (5.1%), acute tonsilitis (5.0%) and acute nasopharyngitis (4.3%). The ranking of the diagnosis groups differed with accredited hospital level. For example, in academic medical centers, asthma was the most common diagnosis (n = 205, 0.3%), followed in order by allergic rhinitis (n = 182, 0.3%), epilepsy (n = 131, 0.2%), acute bronchitis & bronchiolitis (n = 121, 0.2%), infant and child health supervision (n = 121, 0.2%), acute upper respiratory infections (n = 104, 0.2%), bulbus cordis anomalies & anomalies of cardiac septal closure (n = 90, 0.2%), bronchopneumonia (n = 76, 0.1%), symptoms related to nutrition, metabolism & development (n = 74, 0.1%), and other endocrine disorders (n = 73, 0.1%).Overall, the most common procedures performed during ambulatory visits to pediatricians were chest view (0.7%, n = 425), complete blood count (0.7%, n = 404), humidity or aerosol therapy-time (0.6%, n = 383), white blood cell differential count (0.6%, n = 374), and general urine examination (0.5%, n = 304) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Top ten procedures and laboratory tests prescribed by pediatricians, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500 sampling).

| NHI Code * | Procedure | No. of Visits | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32001C | Chest view (including each view of chest film) | 425 | 0.7% |

| 08001C | Complete blood count | 404 | 0.7% |

| 57021C | Humidity or aerosol therapy- time | 383 | 0.6% |

| 08013C | White blood cell differential count | 374 | 0.6% |

| 06012C | General urine examination | 304 | 0.5% |

| 09026C | S-GPT/ALT | 225 | 0.4% |

| 09005C | Blood glucose | 212 | 0.3% |

| 57110C | Blood sampling | 208 | 0.3% |

| 18007B | Doppler color flow mapping | 178 | 0.3% |

| 09015C | Serum creatinine | 176 | 0.3% |

* Taiwan’s National Health Insurance code.

The utilization of the procedures also varied with different ambulatory care settings. For example, complete blood count was the most common procedure applied in medical centers, while humidity or aerosol therapy-time was performed most frequently in physician clinics. Of the ambulatory visits to pediatricians, 92.5% (n = 56,169) were managed by medication. Only 10.6% of the visits were given with a single drug prescription, whereas approximately 81.9% of the visits were prescribed with two or more drugs. Moreover, 50.5% had the prescriptions of four or more drugs. The most commonly prescribed medications were anti-histamine (48.8%), expectorants (32.0%) and cough suppressants (26.5%; Table 5).

Table 5.

Top ten drug classes prescribed by pediatricians, data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance in 2012 (sampling rate: 1/500).

| ATC Code * | Drug Classification | No. of Visits | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| R06A | Antihistamines for systemic use | 29,608 | 48.8 |

| R05C | Expectorants | 19,457 | 32.0 |

| R05D | Cough suppressants | 16,091 | 26.5 |

| M01A | Anti-inflammatory, non-steroids | 15,003 | 24.7 |

| R03C | Adrenergics for systemic use | 14,865 | 24.5 |

| N02B | Other analgesics and antipyretics | 14,021 | 23.1 |

| R01B | Nasal decongestants for systemic use | 11,451 | 18.9 |

| R05F | Cough suppressants & expectorants combinations | 9142 | 15.1 |

| A03A | Drugs for functional bowel disorders | 7640 | 12.6 |

| R03D | Other systemic drugs for obstructive airway diseases | 6463 | 10.6 |

* Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code.

4. Discussion

The present study confirmed the contribution of physician clinics as the main providers of the ambulatory care to attend to 83.0% (n = 50,448) of the visits to pediatricians. The primary medical practitioners took the heaviest responsibilities in managing the need for pediatric care. Namely, the pattern of ambulatory visits met the expectation of primary medical care for minor conditions.

The pediatricians are well-disciplined as a specialty to offer medical care for people before their adulthood, including neonates, infants, toddlers, pre-schools, school-ages, and adolescents. Therefore, in usual case, the patients who visit the pediatricians should fall into the range aged 0–19 years. However, we noticed a number of people who visited the pediatricians even after their twenties, which occurred more in female patients than in male patients. The reasons may be multiple. First, the female patients tend to care more about their own health condition and have more health seeking behaviors [17,18,19]. Second, mothers are more likely to bring their children to see doctors, therefore have more opportunities to visit the pediatricians than fathers do. Further, as listed in Table 3, upper respiratory infection is the most common diagnosis and might run the risk of group infection. That means the family who bring the children may also need medical care meanwhile.

In our study, more visits were paid to male physicians than to female physicians. The gender disparity turned more apparent with age of the physicians (Figure 2) possibly because fewer women were educated to become physicians in the past [20] (p.18, pp.161–162). Another finding was that the majority of visits went to pediatricians aged 40–49 years, coupled with the fact that most of the visits were managed in the clinics. The pediatricians aged 40–49 years were out of question regarded as the principal supply of workforce in the clinics. Among the number of investigations on manpower of pediatricians, a report from Taiwan has indicated an obvious shift of more and more workforce of the pediatricians from hospitals to local clinics, in view of the incessant drop of fertility condition that rendered insufficiency or aging of manpower in hospitals [21]. Similar phenomenon was also observed in obstetrician-gynecologists [22].

In Taiwan, unbalanced development among different medical specialties has always been a problem. According to a previous report, new applicants for pediatric residency training and candidates for licensure examination of pediatricians have both decreased in the recent years [21]. The rural-urban inequality of practicing pediatricians has also deteriorated due to the decrease of pediatricians [23]. The insufficient medical care was estimated to affect approximately 27% of the pediatric population [24]. Moreover, among the total of 319 townships in this island, 132 had no pediatrician at all. A longitudinal, retrospective study [25] was conducted and the result inferred that the amount of pediatricians would continue to decrease because of the reduced child populations, thus to increase the workload of each pediatrician.

As demonstrated in Table 3, respiratory diseases were the most common cause for ambulatory visits to pediatricians. This finding was consistent with a previous report [14], and could thus help explain why some common procedures such as blood examination or chest X-ray (Table 4) were relatively underused. URI does not require laboratory evidence for diagnosis and the children are usually intolerant of invasive procedures. Chest X-rays are not necessary for URI, either, unless there is concern about lower respiratory tract involvement.

Regarding the prescription of medication, anti-histamine agents were prescribed the most often, accounting for nearly half of the visits (48.8%). Symptomatic agents including non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, antipyretics, expectorants and cough suppressants were all commonly used for URI. Prescribing antibiotics in the pediatric population has become a global issue, especially concerning their overuse for URI. In the United States, the prescriptions of antibiotics for children with URI has decreased in these years [26,27,28]. Intervention by strict criteria, enforcement of national guidelines and community-wide campaign could have influences in antibiotics prescribing for children [29,30,31]. However, the low overall consumption of antibiotics is by no means an indicator of appropriate pediatric antibiotic prescribing [12]. American Academy of Pediatrics has published an article and presented that broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing accounts for 50% of antibiotic use in ambulatory pediatrics in respiratory conditions for which antibiotics are not indicated [32]. In Taiwan, we have guideline on community acquired pneumonia and influenza infection for children [33]. Ever since the NHI program restricted the use of antibiotics for URI in 2001, antibiotics never appear among the top 10 most prescribed medications. However, the appropriate use of antibiotics still needs continuing investigation.

The resources used in this study, which were compiled by the National Health Insurance Administration, impose certain limitations on our analysis. For instance, the results do not include self-paid procedures or medicines, such as expensive vaccines and medicine. In Taiwan, atypical pneumonia is not uncommon [34], but the use of macrolides (e.g., azithromycin) is self-paid except for erythromycin, unless laboratory confirmation is carried out. As for non-publicly funded vaccines, conjugated pneumococcal vaccine must be paid with coverage by some local governments in Taiwan. Nevertheless, since the NHI program pays for most diseases and preventive care, the above issues no longer have a significant impact on the pattern of ambulatory visits recorded in this study, although it should also be noted that our figures do not present a complete picture. Second, the pediatricians tend to make tentative rather than final diagnoses for claims at ambulatory setting. Therefore, the accuracy of the diagnoses is not guaranteed. Third, our analyses using visit-based sampling datasets might fail to reveal the comorbidities and subsequent status of the patients studied.

5. Conclusions

In Taiwan, male pediatricians aged 40–49 years provided most of the ambulatory care services. Physician clinics handled four-fifths of the ambulatory visits. Respiratory tract diseases accounted for 64.7% of the visits to pediatricians, and the majority of them were managed at the local clinics. In addition, prescribing multiple drugs for symptomatic patients with URI should be further investigated to evaluate their potential benefits or damage, and at the same time to appropriately allocate the costs.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted based in part on data from the NHIRD provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, or the National Health Research Institutes. This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC 100-2410-H-010-001-MY3) and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V104E10-001).

Author Contributions

Ling-Yu Yang conceived the idea for the study. Tzeng-Ji Chen carried out the analyses. An-Min Lynn drafted the manuscript. Ling-Yu Yang revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mahnke C.B. The growth and development of a specialty: The history of pediatrics. Clin. Pediatr. 2000;39:705–714. doi: 10.1177/000992280003901204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu M.H., Chen H.C., Wang J.K., Chiu H.H., Huang S.C., Huang S.K. Population-based study of pediatric sudden death in Taiwan. J. Pediatr. 2009;155 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y.H. Trends in low fertility and policy responses in Taiwan. Jpn. J. Popul. 2012;10:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin M.C., Lai M.S. Pediatricians’ role in caring for preschool children in Taiwan under the national health insurance program. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2009;108:849–855. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freed G.L., Dunham K.M., Gebremariam A., Wheeler J.R., Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics Which pediatricians are providing care to America’s children? An update on the trends and changes during the past 26 years. J. Pediatr. 2010;157 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCaig L.F., Besser R.E., Hughes J.M. Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA. 2002;287:3096–3102. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder J.A., Bates D.W., Lee G.M., Finkelstein J.A. Antibiotic treatment of children with sore throat. JAMA. 2005;294:2315–2322. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.18.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson K.L., Mandl K.D. Temporal patterns of medications dispensed to children and adolescents in a national insured population. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang T., Smith M.A., Camp P.G., Shajari S., MacLeod S.M., Carleton B.C. Prescription drug dispensing profiles for one million children: A population-based analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;69:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thrane N., Steffensen F.H., Mortensen J.T., Schønheyder H.C., Sørensen H.T. A population-based study of antibiotic prescriptions for Danish children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1999;18:333–337. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L., Mendoza R., Costa M.M., Ottoni E.J., Bertaco A.S., Santos J.C., D’avila N.E., Faria C.S., Zenobini E.C., Gomesa A. Antibiotic use in community-based pediatric outpatients in southern region of Brazil. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2005;51:304–309. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lass J., Odlind V., Irs A., Lutsar I. Antibiotic prescription preferences in paediatric outpatient setting in Estonia and Sweden. Springerplus. 2013;2 doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang C.M., Chan I.C., Lee Y.S., Tsao P.C., Yang C.F., Soong W.J., Chen T.J., Jeng M.J. Role of pediatricians in the ambulatory care of children in Taiwan, 1999–2011. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2015;56:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao P., Ku M., Lue K., Sun H. Respiratory tract infection is the major cause of the ambulatory visits in children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2011;37 doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-37-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Insurance Research Database. [(accessed on 30 October 2015)]. Available online: http://w3.nhri.org.tw/nhird/

- 16.World Health Organization ATC/DDD Index 2015. [(accessed on 30 October 2015)]. Available online: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 17.Galdas P.M., Cheater F., Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005;49:616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliver M.I., Pearson N., Coe N., Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. Brit. J. Psychiatry. 2005;186:297–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ek S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015;30:736–745. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taiwan Medical Association Stastics for 2014. 2015. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://www.tma.tw/tma_stats_2014/2014_stats.pdf.

- 21.Globalization Medical Education The Analysis of Variance of Physician Manpower over the Years. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://spaces.isu.edu.tw/~amed/Fileupload/results/20100809215021.pdf.

- 22.Lynn A.-M., Lai L.-J., Lin M.-H., Chen T.-J., Hwang S.-J., Wang P.-H. Pattern of ambulatory care visits to obstetrician-gynecologists in Taiwan: A nationwide analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:6832–6841. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liou J.S. Exam the Social Inequality Issues from Disparity between Urban and Rural Infant Mortality. 2004. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://handle.ncl.edu.tw/11296/ndltd/83353925990290415649.

- 24.Liao H.C. Spatial Accessibility to Pediatric Services in Taiwan. 2013. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://readopac2.ncl.edu.tw/nclJournal/search/detail.jsp?sysId=0006725343&dtdId=000040&search_type=detail&la=ch.

- 25.Huang S.S. Study on the Effect of Low Birth Rate to Supply and Demand of Pediatric Specialist Manpower in Taiwan. 2013. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://ir.kmu.edu.tw/handle/310902000/35668.

- 26.Halasa N.B., Griffin M.R., Zhu Y., Edwards K.M. Decreased number of antibiotic prescriptions in office-based settings from 1993 to 1999 in children less than five years of age. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2002;11:1023–1028. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nash D.R., Harman J., Wald E.R., Kelleher K.J. Antibiotic prescribing by primary care physicians for children with upper respiratory tract infections. Arch Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002;15:1114–1119. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller G.E., Hudson J. Children and antibiotics: Analysis of reduced use, 1996–2001. Med. Care. 2006;44:136–144. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208142.53164.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelstein J.A., Metlay J.P., Davis R.L., Rifas-Shiman S.L., Dowell S.F., Platt R. Antimicrobial use in defined populations of infants and young children. Arch Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000;154:395–400. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perz J.F., Craig A.S., Coffey C.S., Jorgensen D.M., Mitchel E., Hall S., Schaffner W., Griffin M.R. Changes in antibiotic prescribing for children after a community-wide campaign. JAMA. 2002;287:3103–3109. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tell D., Engström S., Mölstad S. Adherence to guidelines on antibiotic treatment for respiratory tract infections in various categories of physicians: A retrospective cross-sectional study of data from electronic patient records. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hersh A.L., Shapiro D.J., Pavia A.T., Shah S.S. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1053–1061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taiwan Pediatric Association Guidelines & Recommendations. [(accessed on 20 July 2015)]. Available online: http://www.pediatr.org.tw/english/guidelines.asp.

- 34.Liu F.C., Chen P.Y., Huang F., Tsai C.R., Lee C.Y., Wang L.C. Rapid diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children by polymerase chain reaction. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2007;40:507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]