Abstract

Background

Stroke prevention by warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, has been an integral part in the management of atrial fibrillation. Vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein (MGP) has been known as a potent inhibitor of arterial calcification and osteoporosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that warfarin therapy affects bone mineral metabolism, vascular calcification, and vascular endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

We studied 42 atrial fibrillation patients at high-risk for atherosclerosis having one or more coronary risk factors. Twenty-four patients had been treated with warfarin for at least 12 months (WF group), and 18 patients without warfarin (non-WF group). Bone alkaline phosphatase (BAP) and under carboxylated osteocalcin (ucOC) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) were measured as bone metabolism markers. Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT) index measured by Endo-PAT2000 was used as an indicator of vascular endothelial function.

Results

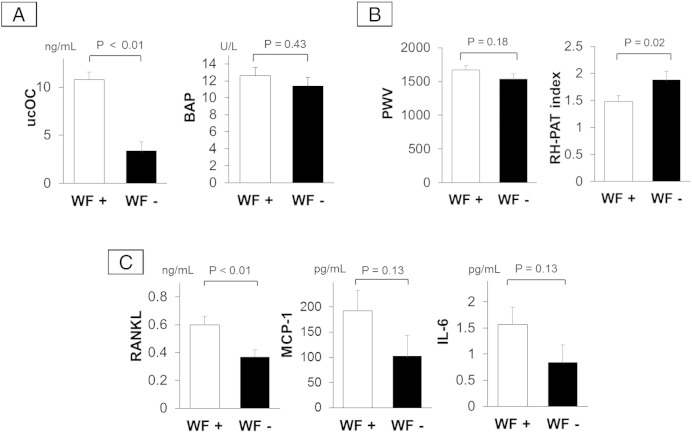

There were no significant differences in patient background characteristics and other clinical indicators between the two groups. In WF group, the ucOC levels were significantly higher than those in the non-WF group (10.3 ± 0.8 vs. 3.4 ± 0.9 ng/mL; P < 0.01), similarly, the RANKL levels in the WF group were higher than those in the non-WF group (0.60 ± 0.06 vs. 0.37 ± 0.05 ng/mL; P = 0.007). Moreover, RH-PAT index was significantly lower in the WF group compared to those in the non-WF group (1.48 ± 0.11 vs. 1.88 ± 0.12; P = 0.017).

Conclusions

Long-term warfarin therapy may be associated with bone mineral loss and vascular calcification in 60–80 year old hypertensive patients.

Abbreviations: MGP, matrix Gla protein; BAP, bone alkaline phosphatase; ucOC, under carboxylated osteocalcin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand; RH-PAT, reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry; OC, osteocalcin; Gas-6, growth arrest specific protein 6; BMD, bone mineral density; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

Keywords: ucOC, RANKL, RH-PAT index, Osteoporosis, Vascular endothelial dysfunction

Highlights

-

•

Stroke prevention by warfarin has been an integral part in the management of atrial fibrillation.

-

•

Warfarin prevents the activation of vitamin K-dependent proteins, MGP and Gas-6.

-

•

Long-term warfarin therapy increases the serum levels of ucOC and RANKL.

-

•

Long-term warfarin therapy is associated with vascular endothelial dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Until recently, warfarin and other vitamin K antagonists have been the only class of oral anticoagulants available for atrial fibrillation to reduce the risk of stroke. However, their use has been limited by a narrow therapeutic range that necessitates frequent monitoring and dose adjustments resulting in substantial risk and inconvenience [1]. There are three typical Vitamin K dependent proteins: osteocalcin (OC), matrix Gla protein (MGP), and growth arrest specific protein 6 (Gas-6) which play key functions in maintaining bone strength, vascular calcification inhibition, and cell growth regulation, respectively. On the other hand, warfarin prevents the activation of MGP and Gas-6; therefore, long-term use of warfarin is reported to be associated with osteoporotic fractures [2]. In addition, it is known that low vitamin K is associated with reduced bone mineral density (BMD) [3]. BMD tests can identify osteoporosis and determine the risk for fractures [4]. According to previous studies of ectopic calcification in osteoporosis patients and their animal models, we hypothesized that long-term warfarin therapy affects both bone mineral metabolism and vascular calcification [5], [6]. We examined blood biomarkers relating to BMD and vascular endothelial function in atrial fibrillation patients with or without long-term warfarin therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Patients were recruited from June 2013 to February 2014 at the Kitasato University Hospital and Kitasato University East Hospital, who were treated for atrial fibrillation at high-risk for atherosclerosis having one or more coronary risk factors. Sixty to eighty year old patients with hypertension were entered into the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: CHADS2 scores > 4, age > 80 years old, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 8.0% and blood pressure (BP) > 160/100 mm Hg. All subjects were given informed consent before participating in the study. The study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara, Japan.

2.2. Blood sample collection and measurement of clinical biomarkers

Blood samples were collected from all participants by venipuncture after an overnight fast. Biochemical markers, such as triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), plasma glucose, HbA1c, uric acid (UA), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), C-reactive protein (CRP), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) were measured. BAP and ucOC were measured as bone metabolism markers.

2.3. Measurement of cytokines

Blood samples for cytokine measurements were centrifuged for 10 min at approximately 3000 r/min 4 °C, and the serum was separated and stored at − 80 °C prior to analysis. We measured seven circulating serum cytokine levels. Circulating levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL), adiponectin, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), human pentraxin 3 (PTX3), interleukin-18 (IL-18), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. ELISA Kit for receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (USCN Life Science Inc., Houston, TX), human total adiponectin/Acrp30 Quantikine ELISA Kit, human CCL2/MCP-1 Quantikine ELISA Kit, human interleukin-6 (IL-6) Quantikine ELISA Kit, human pentraxin 3/TSG-14 Quantikine ELISA Kit, human TNF-α Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), and human IL-18 ELISA Kit (MBL International, Woburn, MA) were used.

2.4. Measurement of vascular endothelial function by Endo-PAT2000

Vascular endothelial function was examined by reactive hyperemia using Endo-PAT2000 (Itamar Medical Ltd., Caesarea, Israel). Using a fingertip peripheral arterial tonometry device, we measured digital pulse amplitude in the supine position to patients for 5 min at baseline and after a reactive hyperemia induced by a 5-min forearm cuff occlusion [7]. RH-PAT was measured in fasting condition. Before measurement, patients were asked to rest for 10 min. The data were digitized and computed automatically with Endo-PAT2000 software; the digital reactive hyperemia peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT) index, representing the endothelial function, was defined as the ratio of the mean post-deflation signal (in the 90 to 120-s post-deflation interval) to the baseline signal in the hyperemic finger and was normalized by the same ratio in the contra-lateral finger and was multiplied by a baseline correction factor, as calculated by the Endo-PAT2000 software.

2.5. Peripheral atherosclerosis assessment

Aortic stiffness was assessed by pulse wave velocity (PWV) and the average of the left and right values was used in the analysis. Ankle-brachial index (ABI) was calculated by dividing the highest systolic blood pressure in each ankle by the highest brachial pressure, and the average of the left and right values was also used in the analysis.

2.6. Assessment of bone mineral density

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements were used to detect bone mineral density. The DXA was used to measure femur neck and lumbar spine (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA). Standardized data acquisition and analysis techniques were used.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Continuous data are summarized as either mean ± SD or median, and categorical data are expressed as percentages. Data were compared by unpaired t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test where appropriate. Differences in proportions of variables were determined by chi-squared analysis. To evaluate the correlations between endothelial function and selected variables, we calculated the Spearman correlation coefficients between RH-PAT index and the following variables: 1) conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease: LDL-C, HDL-C, triglyceride, HbA1c, presence of hypertension, body mass index (BMI), and previous smoking, and history of coronary artery disease; 2) osteoporosis and vascular calcification-related markers (ucOC, RANKL, DXA, PWV, ABI). All parameters with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate Cox-regression analysis. We conducted multivariate logistic regression models to assess whether circulating RANKL was independently associated with RH-PAT index.

3. Results

3.1. Subject characteristics

We recruited 42 atrial fibrillation patients having one or more coronary risk factors in the clinic of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kitasato University Hospital and Kitasato University East Hospital (average age 68 years old, 15% female). Twenty-four patients who had been treated with warfarin at least 12 months were enrolled as the warfarin group (WF group), and 18 patients treated without warfarin were also enrolled as the non-warfarin group (non-WF group). Among the 18 patients, 10 patients received dabigatran, and 1 patient received apixaban.

3.2. Long-term warfarin therapy and atherosclerosis

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences in patient background characteristics between the WF group and the non-WF group, including coronary risk factors. As shown in Table 2, there was no significant difference in PWV. In addition, circulating levels of CRP and ABI were not different between the two groups.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics at baseline.

| Patients' characteristics | WF group (n = 24) |

Non-WF group (n = 18) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age (years) | 68.6 ± 1.4 | 67.1 ± 1.5 | 0.47 |

| Males, n (%) | 22 (92) | 14 (78) | 0.25 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 18 (75) | 11 (61) | 0.15 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 8 (33) | 2 (11) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (21) | 2 (11) | 0.68 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 16 (67) | 11 (61) | 0.59 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 0.6 | 22.4 ± 0.7 | 0.06 |

| CHADS2 score | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.02 |

The CHADS2 score is a clinical prediction score for estimating the risk of stroke in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. Values are means ± SD.

WF: warfarin; BMI: body mass index.

Table 2.

Patients' clinical data.

| Patients' clinical data | WF group (n = 24) |

Non-WF group (n = 18) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labo data | |||

| P (mg/dL) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.09 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 0.35 |

| BAP (U/L) | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 11.4 ± 1.1 | 0.39 |

| ucOC (ng/mL) | 10.3 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | < 0.01⁎ |

| Physiological function test | |||

| RH-PAT index | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.02⁎ |

| PWV (m/s) | 1672 ± 65 | 1536 ± 74 | 0.18 |

| Bone mineral density | |||

| DXA (g/cm2) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.19 |

| Cytokines | |||

| RANKL (ng/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | < 0.01⁎ |

| Adiponectin (ng/mL) | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | 0.56 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mL) | 192.3 ± 39.9 | 102.4 ± 41.0 | 0.13 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.13 |

| Pentraxin3 (ng/mL) | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 0.82 |

| IL-18 (pg/mL) | 309.2 ± 19.4 | 256.6 ± 19.9 | 0.07 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.60 |

Values are means ± SD. WF: warfarin; BAP: bone alkaline phosphatase; ucOC: under carboxylated osteocalcin; RH-PAT index: reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry index; PWV: pulse wave velocity; DXA: Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand; MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein-1; IL-6: interleukin-6; IL-18: interleukin-18 and TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

P < 0.05.

3.3. Calcification related biomarkers

There were significant differences in circulating levels of ucOC and RANKL between the two groups (Table 2). Serum levels of ucOC were significantly higher in the WF group than those in the non-WF group (10.3 ± 0.8 vs. 3.4 ± 0.9 ng/mL; P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). Serum levels of RANKL in the WF group were higher than those in the other (0.6 ± 0.1 vs. 0.4 ± 0.1 ng/mL; P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in DXA (P = 0.19) or prior history of bone fracture between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

A. A bone metabolism marker, serum levels of ucOC, were significantly higher in warfarin therapy patients rather than those in the non-warfarin group.

B. Atherosclerosis and vascular inflammatory marker, serum levels of RANKL, were higher in the warfarin group than those in the non-warfarin group.

C. Pulse wave velocity and endothelial function in patients with atrial fibrillation. Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT) index was significantly lower in warfarin group compared to that of the other group.

Values are means ± SD. * P < 0.05.

ucOC: under carboxylated osteocalcin; BAP: bone alkaline phosphatase and RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand.

3.4. Vascular endothelial function

RH-PAT is a noninvasive technique to assess the peripheral microvascular endothelial function by measuring changes in the digital pulse volume during reactive hyperemia. RH-PAT index in WF group was significantly lower compared to those in the non-WF group (1.5 ± 0.1 vs. 1.9 ± 0.16; P = 0.02) (Fig. 1C). Several clinical factors were associated with the RH-PAT index on univariate analysis (Table 3): BMI, HbA1c, BNP, LDL-C. However, serum levels of ucOC and RANKL were not correlated with RH-PAT index. The multivariate analysis revealed that BMI and BNP were independent predictors of endothelial dysfunction measured by RH-PAT. Those factors were negatively correlated with RH-PAT index (the BMI β was − 0.370 with a 95% CI of − 0.116 to − 0.007; P = 0.027, the BNP β was − 0.306 with a 95% CI of − 0.003 to − 1.265; P = 0.049).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of clinical factors associated with the RH-PAT index.

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | 95% CI | P value | β | 95% CI | P value |

| Age (years) | − 0.184 | − 0.042 to 0.013 | 0.289 | |||

| HR (/min) | − 0.332 | − 0.029 to 8.284 | 0.05 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | − 0.542 | − 0.143 to − 0.042 | < 0.001⁎ | − 0.370 | − 0.116 to − 0.008 | 0.027⁎ |

| CHADS2 score | − 0.191 | − 0.372 to 0.108 | 0.271 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | − 0.457 | − 0.639 to − 0.107 | 0.008⁎ | − 0.113 | − 0.362 to 0.184 | 0.510 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 0.364 | 0.0005 to 0.015 | 0.037⁎ | 0.244 | − 0.012 to 0.244 | 0.108 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | − 0.492 | − 0.005 to − 0.001 | 0.003⁎ | − 0.306 | − 0.004 to − 1.265 | 0.049⁎ |

| eGFR (mL/min) | − 0.008 | − 0.012 to 0.012 | 0.962 | |||

| P (mg/dL) | − 0.099 | − 0.393 to 0.232 | 0.602 | |||

| Ca (mg/dL) | 0.009 | − 0.554 to 0.581 | 0.962 | |||

| BAP (U/L) | 0.132 | − 0.025 to 0.055 | 0.449 | |||

| ucOC (ng/mL) | − 0.147 | − 0.049 to 0.020 | 0.398 | |||

| PWV (m/s) | 0.020 | − 0.0007 to 0.0007 | 0.914 | |||

| RANKL (ng/mL) | − 0.204 | − 0.019 to 0.005 | 0.240 | |||

| Adiponectin (ng/mL) | − 0.063 | − 0.041 to 0.029 | 0.724 | |||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | − 0.164 | − 0.172 to 0.063 | 0.355 | |||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | − 0.050 | − 0.033 to 0.025 | 0.779 | |||

Values are means ± SD.

HR: heart rate; BMI: body mass index; BAP: bone alkaline phosphatase; ucOC: under carboxylated osteocalcin; RH-PAT index: reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry index; PWV: pulse wave velocity; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that long-term warfarin therapy was associated with: 1) higher ucOC, a vitamin K-dependent bone resorption marker; 2) higher level of RANKL and 3) lower RH-PAT index. Although it was reported that long-term warfarin therapy was related to the progression of aortic stiffness in hemodialysis patients, PWV and DXA were not related in patients with long-term warfarin therapy [8]. In terms of early prediction of atherosclerosis, this is the first report to evaluate the association of long-term warfarin therapy with endothelial function.

Since warfarin is a vitamin K antagonist, patients who are on warfarin therapy must be prohibited from taking vitamin K-rich foods. Vitamin K-dependent bone proteins and extracellular matrix such as OC, MGP, and Gas-6 play an important role in controlling bone remodeling [3], [9]. These proteins and their matrix are activated with γ-carboxylation of glutamic acid residues. The fraction of imperfect γ-carboxylation is referred to as ucOC, which is produced and released from osteoblasts into the vitamin K insufficiency or deficiency. Serum ucOC is rapidly decreased with Vitamin K2 treatment [10]. On the other hand, regular intake of vitamin K increases BMD, and reduces the bone fracture risk [11]. Therefore, the high level of serum ucOC induced by long-term warfarin therapy is considered one of the risks of osteoporosis. It has been reported that 4.5 ng/mL of ucOC has a cut-off value to determine vitamin K insufficiency or deficiency for osteoporotic fractures [10]. In addition, it was also reported that serum ucOC is an independent determinant of carotid artery calcification and negatively correlates with renal function [12]. In the present study, we showed that serum ucOC level was three-times higher in long-term warfarin therapy patients compared to that in non-warfarin therapy patients. In the non-WF group, the circulating level of ucOC was within the normal range. Although the bone mineral density measured by DXA was not reduced in our study patients, long-term warfarin therapy may increase the risk of patient's osteoporosis in their future.

In addition, not only serum ucOC but also RANKL was higher in long-term warfarin therapy patients than that in the non-WF group. RANKL is a membrane binding type protein and a member of the TNF super family. An increasing level of RANKL was reported in vascular inflammation, atherosclerosis, and osteoporosis [13], [14], [15]. RANKL is expressed on the surface of osteoblasts and osteoclast precursor cells, promotes differentiation of osteoclast and induces the activity of bone resorption [16]. Intimal atherosclerotic calcification is the most common form of calcium accumulation, in association with macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). It is seen in people with risk factors of atherosclerosis development, and also in patients suffering from chronic arterial hypertension or osteoporosis [17]. Recent studies showed that, RANKL was able to induce VSMC calcification in vitro by binding to RANK [18], [19]. In this study, serum ucOC and RANKL were higher in the WF group, which suggests that vascular inflammation, calcification, and osteoporosis are increased in these patients. Long-term warfarin therapy might be associated with the high risk of osteoporosis and ectopic calcification in vasculature or heart valves.

Atrial fibrillation is associated with vascular thrombosis and inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [20]. We examined endothelial function using EndoPAT2000, which provides reliable and reproducible assessments of endothelial function [21], [22], [23]. RH-PAT index is a reproducible and less operator-dependent technique for endothelial function assessment that noninvasively reflects coronary endothelial function. In addition, RH-PAT index well reflects the risk factors of metabolic syndrome including obesity, and high cholesterol, diabetes, smoking [20]. Ohno Y. et al. reported that, an RH-PAT index value of < 1.67 is considered to indicate endothelial dysfunction in a population at risk for ischemic heart disease [24]. We showed that the RH-PAT index in the WF group was significantly lower than that in the non-WF group. In addition, we found that BMI and BNP were independent predictors of endothelial dysfunction measured by RH-PAT index. However, patients in the present study were not that of severe obesity or severe heart failure (the BMI median 23.4, the BNP median 84.2). Previous studies showed that, atrial fibrillation is associated with impairment of endothelial dysfunction [25]. In addition, patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia have been associated with impaired vasodilator responses [26], [27]. A lower level of digital hyperemia reaction in obese patients is consistent with impaired microvessel flow reserve, which may contribute to impaired blood flow supply in the setting of increased metabolic demand [28]. Pauriah et al. reported that plasma BNP was found to be an independent predictor of endothelial function in several biomarkers assessed by the invasive acetylcholine induced forearm vasodilatation technique [29]. Therefore, we considered that the atrial fibrillation patients who are obese, or have high levels of BNP might be at an increased risk of vascular endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial dysfunction is a key component of atherosclerosis and contributes to the development of clinical cardiovascular diseases [30]. Taking into consideration that the decrease of the RH-PAT index in the WF group was relatively mild compared to previous studies of patients with coronary heart disease or high-risk patients of atherosclerosis, further studies are needed to examine the correlation between the RH-PAT index and various coronary risk factors to predict atherosclerosis progression and prevent cardiovascular diseases.

The WASID (Warfarin–Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease) study reported that, they compared the efficacy of warfarin with aspirin for the prevention of major vascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or sudden death) in patients with symptomatic stenosis of a major intracranial artery, incidence of major vascular events was significantly lower in the warfarin group [31]. Recently, NOAC are rapidly integrated into clinical practice, warfarin is still an essential anticoagulant for artificial heart valve replacement surgery and intraventricular thrombus. Even though long-term warfarin therapy was associated with decreased vitamin K dependent bone proteins and promotes endothelial dysfunction, warfarin must be one of the important anticoagulant therapeutic strategies in future clinical settings. In the present study, we found that in osteoporosis patients who require long-term warfarin therapy, the limit of vitamin K intake is not preferable. Therefore, we should change to other anticoagulants as possible. In patients who can't change the warfarin, we conduct the screening of osteoporosis and it seems to be preferable to consider the treatment of osteoporosis other than vitamin K2 as necessary. However, since there is no evidence such as therapy is effective, further study is needed in the future. In addition, among patients at high-risk of atherosclerosis, patients who can't change warfarin are also need to be measured the endothelial function on a regular basis. Furthermore, it is important to control the other factors that cause vascular endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, it is important that we understand the effects and risks of warfarin therapy, especially in high-risk patients with osteoporosis and atherosclerosis.

5. Study limitations

This was an observational single-center prospective study with a limited number of patients, posing a significant risk of selection bias. We have measured the RH-PAT index to detect endothelial function, and some patients could not be measured by the RH-PAT index automatically due to tachy-arrhythmias. Because of the technical limitation, we had to exclude 7 patients from the study.

6. Conclusions

Long-term warfarin therapy may be associated with bone mineral loss and vascular calcification in 60–80 year old hypertensive patients.

Transparency document

Transparency document

Conflict of interest

Dr. Minako Yamaoka-Tojo was partly supported by grants from Bayer Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Other authors have nothing to disclose regarding this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supposed by a Grant-in Aid for Research Project from Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences, an International Grant from MSD (K.K.), and Bayer Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Boehringer Ingelheim (M.Y.-T.). Dr. Junya Ako received speaking honorarium from Bayer Pharma and Boehringer Ingelheim. The other authors have nothing to disclose regarding this manuscript.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Ruff C.T., Giugliano R.P., Braunwald E., Hoffman E.B., Deenadayalu N., Ezekowitz M.D., Camm A.J., Weitz J.I., Lewis B.S., Parkhomenko A., Yamashita T., Antman E.M. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gage B.F., Birman-Deych E., Radford M.J., Nilasena D.S., Binder E.F. Risk of osteoporotic fracture in elderly patients taking warfarin: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation 2. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:241–246. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binkley N.C., SÃœTTI J.W. Vitamin K nutrition and osteoporosis. J. Nutr. 1995;125(7):1812–1821. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.7.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamed S.A., Moussa E.M., Youssef A.H., Abd ElHameed M.A., NasrEldin E. Bone status in patients with epilepsy: relationship to markers of bone remodeling. Front. Neurol. 2014;5:142. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krüger T., Oelenberg S., Kaesler N., Schurgers L.J., van de Sandt A.M., Boor P., Schlieper G., Brandenburg V.M., Fekete B.C., Veulemans V., Ketteler M., Vermeer C., Jahnen-Dechent W., Floege J., Westenfeld R. Warfarin induces cardiovascular damage in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33(11):2618–2624. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tufano A., Coppola A., Contaldi P., Franchini M., Minno G.D. Oral anticoagulant drugs and the risk of osteoporosis: new anticoagulants better than old? Semin. Thromb. Hemost. Feb 19 2015 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1543999. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goswami N., Gorur P., Pilsl U., Anyaehie B., Green D.A., Bondarenko A.I., Roessler A., Hinghofer-Szalkay H.G. Effect of orthostasis on endothelial function: a gender comparative study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mac-Way F., Poulin A., Utescu M.S., De Serres S.A., Marquis K., Douville P., Desmeules S., Larivière R., Lebel M., Agharazii M. The impact of warfarin on the rate of progression of aortic stiffness in hemodialysis patients: a longitudinal study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014;29:2113–2120. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sv B. Vitamin K and bone health in adult humans. Vitam. Horm. 2008;78:393–416. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasukawa Y., Miyakoshi N., Ebina T., Aizawa T., Hongo M., Nozaka K., Ishikawa Y., Saito H., Chida S., Shimada Y. Effects of risedronate alone or combined with vitamin K2 on serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin and osteocalcin levels in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2014;32:290–297. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heiss C., Hoesel L.M., Wehr U., Wenisch S., Drosse I., Alt V., Meyer C., Horas U., Schieker M., Schnettler R. Diagnosis of osteoporosis with vitamin K as a new biochemical marker. Vitam. Horm. 2008;78:417–434. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okura T., Kurata M., Enomoto D., Jotoku M., Nagao T., Desilva V.R., Irita J., Miyoshi K., Higaki J. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin is a biomarker of carotid calcification in patients with essential hypertension. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2010;33:66–71. doi: 10.1159/000289575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osako M., Nakagami H., Shimamura M., Koriyama H., Nakagami F., Shimizu H., Miyake T., Yoshizumi M., Rakugi H., Morishita R. Cross-talk of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand signaling with renin–angiotensin system in vascular calcification. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:1287–1296. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.301099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndip A., Wilkinson F.L., Jude E.B., Boulton A.J., Alexander M.Y. RANKL-OPG and RAGE modulation in vascular calcification and diabetes: novel targets for therapy. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2251–2260. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3348-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki T., Tokimura F., Tanaka S. A review of denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2014;8:463–471. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S46192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panizo S., Cardus A., Encinas M., Parisi E., Valcheva P., López-Ongil S., Coll B., Fernandez E., Valdivielso J.M. RANKL increases vascular smooth muscle cell calcification through a RANK–BMP4-dependent pathway. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1041–1048. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collin-Osdoby P. Regulation of vascular calcification by osteoclast regulatory factors RANKL and osteoprotegerin. Circ. Res. 2004;95:1046–1057. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000149165.99974.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callegari A., Coons M.L., Ricks J.L., Rosenfeld M.E., Scatena M. Increased calcification in osteoprotegerin-deficient smooth muscle cells: dependence on receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand and interleukin 6. J. Vasc. Res. 2014;51:118–131. doi: 10.1159/000358920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander M.Y. RANKL links arterial calcification with osteolysis. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1032–1034. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin S.Y., Na J.O., Lim H.E., Choi C.U., Choi J.I., Kim S.H., Kim E.J., Park S.W., Rha S.W., Park C.G., Seo H.S., Oh D.J., Kim Y.H. Improved endothelial function in patients with atrial fibrillation through maintenance of sinus rhythm by successful catheter ablation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2011;22:376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubinshtein R., Kuvin J.T., Soffler M., Lennon R.J., Lavi S., Nelson R.E., Pumper G.M., Lerman L.O., Lerman A. Assessment of endothelial function by non-invasive peripheral arterial tonometry predicts late cardiovascular adverse events. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki H., Matsuzawa Y., Konishi M., Akiyama E., Takano K., Nakayama N., Kataoka S., Ebina T., Kosuge M., Hibi K., Tsukahara K., Iwahashi N., Endo M., Maejima N., Shinohara K., Taki N., Mitsugi N., Taguri M., Sugiyama S., Ogawa H., Umemura S., Kimura K. Utility of noninvasive endothelial function test for prediction of deep vein thrombosis after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Circ. J. 2014;78:1723–1732. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto M., Hara H., Moroi M., Ito S., Nakamura S., Sugi K. Impaired digital reactive hyperemia and the risk of restenosis after primary coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2014;21:957–965. doi: 10.5551/jat.19497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohno Y., Hashiguchi T., Maenosono R., Yamashita H., Taira Y., Minowa K., Yamashita Y., Kato Y., Kawahara K., Maruyama I. The diagnostic value of endothelial function as a potential sensor of fatigue in health. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:135–144. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshino S., Yoshikawa A., Hamasaki S., Ishida S., Oketani N., Saihara K., Okui H., Kuwahata S., Fujita S., Ichiki H., Ueya N., Iriki Y., Maenosono R., Miyata M., Tei C. Atrial fibrillation-induced endothelial dysfunction improves after restoration of sinus rhythm. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;30(168(2)):1280–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jongh R.T., Serné E.H., IJzerman R.G., de Vries G., Stehouwer C.D. Impaired microvascular function in obesity: implications for obesity-associated microangiopathy, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2529–2535. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129772.26647.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gokce N., Vita J.A., McDonnell M., Forse A.R., Istfan N., Stoeckl M., Lipinska I., Keaney J.F., Jr., Apovian C.M. Effect of medical and surgical weight loss on endothelial vasomotor function in obese patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005;95(2):266–268. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell G.F., Vita J.A., Larson M.G., Parise H., Keyes M.J., Warner E., Vasan R.S., Levy D., Benjamin E.J. Cross-sectional relations of peripheral microvascular function, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic stiffness: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112(24):3722–3728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.551168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pauriah M., Khan F., Lim T.K., Elder D.H., Godfrey V., Kennedy G., Belch J.J., Booth N.A., Struthers A.D., Lang C.C. B-type natriuretic peptide is an independent predictor of endothelial function in man. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2012;123(5):307–312. doi: 10.1042/CS20110168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widlansky M.E., Gokce N., Keaney J.F., Jr., Vita J.A. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chimowitz M.I., Kokkinos J., Strong J., Brown M.B., Levine S.R., Silliman S., Pessin M.S., Weichel E., Sila C.A., Furlan A.J. The Warfarin–Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Study. Neurology. 1995;45:1488–1493. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document