Abstract

Backgrounds

Glycero-lysophospholipids (glycero-LPLs), which are known to exert potent biological activities, have been demonstrated to be secreted from activated platelets in vitro; however, their association with platelet activation in vivo has not been yet elucidated. In this study, we investigated the correlations between the blood levels of each glycero-LPL and serotonin, a biomarker of platelet activation, in human subjects to elucidate the involvement of platelet activation in glycero-LPLs in vivo.

Methods and Results

We measured the plasma serotonin levels in 141 consecutive patients undergoing coronary angiography (acute coronary syndrome, n = 38; stable angina pectoris, n = 71; angiographically normal coronary arteries, n = 32) and investigated the correlations between the plasma levels of serotonin and glycero-LPLs. The results revealed the existence of a specific and significant association between the plasma serotonin and plasma lysophosphatidylserine (LysoPS) levels. On the contrary, regular aspirin intake failed to affect the plasma LysoPS levels despite the fact that the plasma lysophosphatidic acid, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, lysophosphatidylglycerol, and lysophosphatidylinositol levels were lower in those who had taken aspirin regularly.

Conclusion

We found a specific positive correlation between the blood levels of serotonin and LysoPS, a new lipid mediator. Thus, LysoPS might be specifically involved in strong platelet activation, which is associated with the release of serotonin.

General Significance

Our present results suggest the possible involvement of LysoPS in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic diseases.

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; Glycero-LPL, glycero-lysophospholipid; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; LysoPA, lysophosphatidic acids; LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LysoPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; LysoPG, lysophosphatidylglycerol; LysoPI, lysophosphatidylinositol; LPL, lysophospholipid; LysoPS, lysophosphatidylserine; NCA, angiographically normal coronary arteries; PS, phosphatidylserine; PS-PLA1, phosphatidylserine-specific phospholipase A1;; SAP, stable angina pectoris

Keywords: Glycero-lysophospholipids, Lysophosphatidylserine, Serotonin, Aspirin, Acute coronary syndrome

Highlights

-

•

A significant positive correlation between the plasma serotonin and lysophosphatidylserine was observed.

-

•

Regular intake of aspirin had no influence on plasma lysophosphatidylserine.

-

•

PS-PLA1 was correlated with lysophosphatidylserine only in acute coronary syndrome.

1. Background

Abnormal platelet activation is involved in the pathogenesis of several fatal diseases, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the incidence of which continues to increase worldwide, threatening human health. Therefore, it would be desirable to identify novel biomarkers reflecting platelet activation to develop as new targets for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of such diseases. While many candidate molecules have been proposed, glycero-lysophospholipids (glycero-LPLs) are among the promising targets. Glycero-LPL is composed of a glycerol backbone with one fatty-acid chain and one hydrophilic compartment, according to which the molecules are classified as lysophosphatidic acid (LysoPA), lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LysoPE), lysophosphatidylglycerol (LysoPG), lysophosphatidylinositol (LysoPI), and lysophosphatidylserine (LysoPS) [1], [2]. At present, they are drawing much attention, since several specific receptors against glycero-LPLs have recently been identified [3], [4].

Among the glycero-LPLs, LysoPA has been most investigated from the aspect of involvement in platelet activation; LysoPA has been demonstrated to be secreted from activated platelets [5], [6] and to induce platelet shape changes, platelet-monocyte aggregation and further aggregation of platelets [7], [8], [9]. Furthermore, minor glycero-LPLs other than LysoPA, such as LysoPS [10], LysoPC, LysoPE [11] and LysoPI [12] have also been demonstrated to be secreted from activated platelets in vitro, although their physiological roles in platelet activation and the consequent pro-atherosclerotic responses have not yet been fully elucidated.

Recently, we reported that the plasma glycero-LPL levels were significantly increased in subjects with ACS, but not in those with stable angina pectoris (SAP), as compared to the levels in subjects with angiographically normal coronary arteries (NCA) [13]. Although based on the findings from previous in vitro experiments [5], [6], [10], [11], [12], the source of the elevated glycero-LPL levels in subjects with ACS might be speculated to be activated platelets, it remains to be definitively elucidated whether the glycero-LPLs are actually derived from platelets in vivo and whether any differences exist among the glycero-LPLs in the pathways by which they are secreted from activated platelets.

In this study, we measured the levels of serotonin as a biomarker of platelet activation in plasma samples [14], [15], [16] obtained from the subjects for our previous study and investigated the correlations between the plasma levels of the glycero-LPLs and this thrombotic biomarker.

2. Methods

2.1. Samples from patients who underwent coronary angiography and measurement of the LPL species

The collection of samples from subjects who underwent coronary angiography in our previous study has been described in earlier reports [13], [17]. The present study was conducted with the approval of the ethics review committee at Juntendo University Hospital, all the participants signed informed consent forms, and the study was registered in the UMIN protocol registration system (#UMIN000002103). This study was also approved by the institutional review boards of both the University of Tokyo and the Juntendo University School of Medicine.

Arterial blood samples were obtained from the arterial sheaths of all the patients in the angiography room prior to the coronary angiography procedures. The blood samples were collected directly into glass vacutainer tubes with or without EDTA to obtain plasma and serum samples, respectively. The samples were immediately placed on ice. The anticoagulated samples were then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant comprising the plasma was carefully collected, avoiding contamination with the cell components. Whole blood samples collected in tubes not containing EDTA-2Na were left to clot, and the serum was separated by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min. Both the plasma and serum samples were stored in aliquots at − 80 °C, and subjected to one freeze–thaw cycle before the measurement of the LPLs and to two freeze–thaw cycles before the measurement of serotonin. Quantification of the glycero-LPLs was performed by LC-MS/MS, as previously described [13], [18].

2.2. Measurement of plasma serotonin

The plasma serotonin was separated by HPLC with a column-switching system and was specifically converted into a fluorescent derivative with benzylamine for convenience of detection, as described previously [19], [20].

2.3. Measurement of the serum phosphatidylserine-specific phospholipase A1 (PS-PLA1) levels

The PS-PLA1 antigen levels in the serum were determined using a two-site immunoenzymetric assay with a PS-PLA1 assay reagent and the TOSOH AIA system (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) [21].

2.4. Statistical analysis

All the data were statistically analyzed using SPSS (Chicago, IL). The results were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison between two groups was carried out using the Mann–Whitney U test, while that among three groups was conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Games Howell test as a post-hoc test, since normality or equality of variance was rejected by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test or the Levene test for most of the parameters or analyses. Correlations were determined using the Spearman correlation test. P < 0.05 was regarded as denoting statistical significance in all the analyses.

3. Results

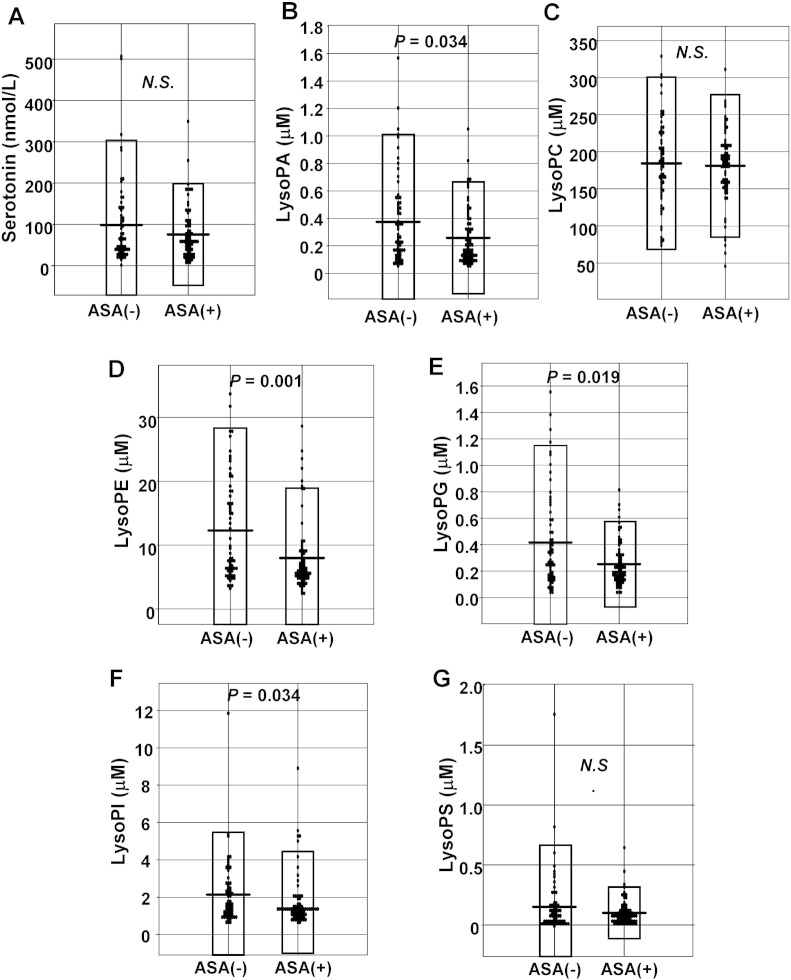

3.1. Plasma serotonin was not significantly elevated in subjects with ACS

The basic characteristics and plasma glycero-LPL levels of the three groups of subjects (NCA, SAP, and ACS) are described in the previous reports [13], [17]. As shown in Fig. 1, no significant elevation of the plasma serotonin level was observed in the ACS patients, although after the values deviating from the − 3 S.D. to + 3 S.D. range were eliminated, the plasma serotonin levels were found to be significantly increased in the ACS group (NCA: 53.3 ± 41.8 nmol/L, SAP: 81.2 ± 60.7 nmol/L, and ACS: 90.2 ± 74.5 nmol/L). In this study, we performed the following analyses using all the data including the outliers.

Fig. 1.

The plasma concentrations of serotonin in the subjects who underwent coronary angiography.

The plasma serotonin levels in the NCA, SAP and ACS groups.

3.2. Plasma serotonin showed a significant positive correlation with the plasma LysoPS

To investigate whether glycero-LPLs are actually secreted from activated platelets in vivo, as reported from in vitro studies, and whether any differences might exist among the plasma levels of the glycero-LPLs, we next compared the plasma level of each glycero-LPL with the plasma serotonin level. Interestingly, the plasma serotonin level was found to be specifically and significantly correlated with the plasma level of LysoPS (Fig. 2A, r = 0.365, P < 0.001), but not with the plasma levels of the other glycero-LPLs, including LysoPA. When the data analysis was confined to the subjects with ACS or SAP, the specific significant correlation between the plasma serotonin and LysoPS levels was again observed (ACS [n = 38]: Fig. 2B, r = 0.370, P = 0.022; SAP [n = 71], r = 0.410, P < 0.01), while no significant correlation was obtained in NCA group.

Fig. 2.

Correlations between the plasma levels of serotonin and the glycero-LPLs.

The correlation between the plasma levels of serotonin and the glycero-LPLs levels in all subjects (A) and in the subjects with ACS (B).

Since we determined the plasma glycero-LPL levels by LC-MS/MS, we could also obtain the plasma concentrations of each molecular species of the glycero-LPLs (14:0, 16:0, 16:1, 18:0, 18:1, 18:2, 18:3, 20:3, 20:4, 20:5, 22:5, and 22:6). Therefore, we next compared the plasma levels of each molecular species of the glycero-LPLs with the plasma serotonin. As shown in Table 1, the plasma levels of 18:0, 18:2, 20:5 and 22:6 LysoPS, but not of any of the other molecular species of the glycero-LPLs (except for 22:6 LysoPE, which showed a weak correlation [r = 0.187, P = 0.027]), were significantly correlated with the plasma serotonin level.

Table 1.

Correlation between the plasma serotonin level and plasma levels of the glycero-LPL species.

| Molecular species | LysoPA | LysoPC | LysoPE | LysoPG | LysoPI | LysoPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14:0 | 0.124 | 0.106 | 0.102 | − 0.008 | − 0.087 | − 0.064 |

| 16:0 | − 0.041 | 0.019 | − 0.031 | 0.142‡ | 0.062 | − 0.058 |

| 16:1 | 0.031 | 0.040 | − 0.007 | 0.103 | 0.078 | 0.114 |

| 18:0 | 0.029 | 0.040 | 0.009 | 0.089 | − 0.004 | 0.330⁎ |

| 18:1 | 0.044 | 0.059 | 0.035 | 0.096 | 0.105 | 0.159‡ |

| 18:2 | 0.017 | 0.053 | 0.112 | 0.103 | 0.089 | 0.211† |

| 18:3 | 0.051 | 0.063 | − 0.058 | 0.032 | 0.034 | − 0.046 |

| 20:3 | 0.035 | 0.084 | 0.083 | 0.010 | 0.085 | 0.063 |

| 20:4 | 0.148‡ | 0.042 | 0.124 | 0.107 | 0.113 | 0.260 |

| 20:5 | − 0.022 | 0.061 | 0.099 | − 0.062 | 0.092 | 0.203† |

| 22:5 | 0.041 | 0.137 | 0.084 | 0.008 | 0.097 | 0.067 |

| 22:6 | 0.119 | 0.132 | 0.187† | 0.059 | 0.044 | 0.210† |

Correlation between the plasma serotonin level and plasma levels of the glycero-LPL species.

The Spearman r value is expressed.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.10.

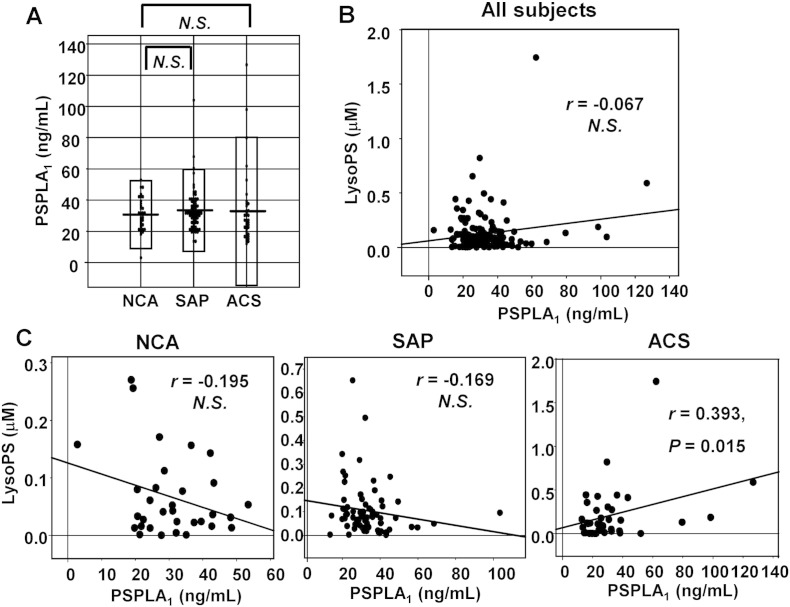

3.3. Regular intake of aspirin had no influence on the plasma LysoPS levels

In this study, 76 of the 141 subjects were regularly taking aspirin [17], although even those subjects who had not been taking aspirin regularly took aspirin before they entered the catheter lab. Since aspirin attenuates the activation of platelets, we next investigated the influence of regular aspirin intake on the plasma glycero-LPL levels. The results revealed that regular intake of aspirin had no effect on the plasma serotonin levels (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, in regard to the levels of the glycero-LPLs, the plasma LysoPA, LysoPE, LysoPG and LysoPI levels were lower in those who had taken aspirin regularly, while the plasma LysoPC and LysoPS remained unaffected (Fig. 3B–G). We speculate that the plasma LysoPC level might not be modulated by regular intake of aspirin, because the plasma LysoPC level is several hundred μM even in normal subjects. On the other hand, the reason for the absence of any relation between the plasma LysoPS and regular aspirin intake remains to be resolved.

Fig. 3.

Effects of regular aspirin intake on the plasma glycero-LPL levels.

The plasma serotonin and glycero-LPL levels in the subjects who had (ASA [+]) and had not (ASA [−]) taken aspirin regularly.

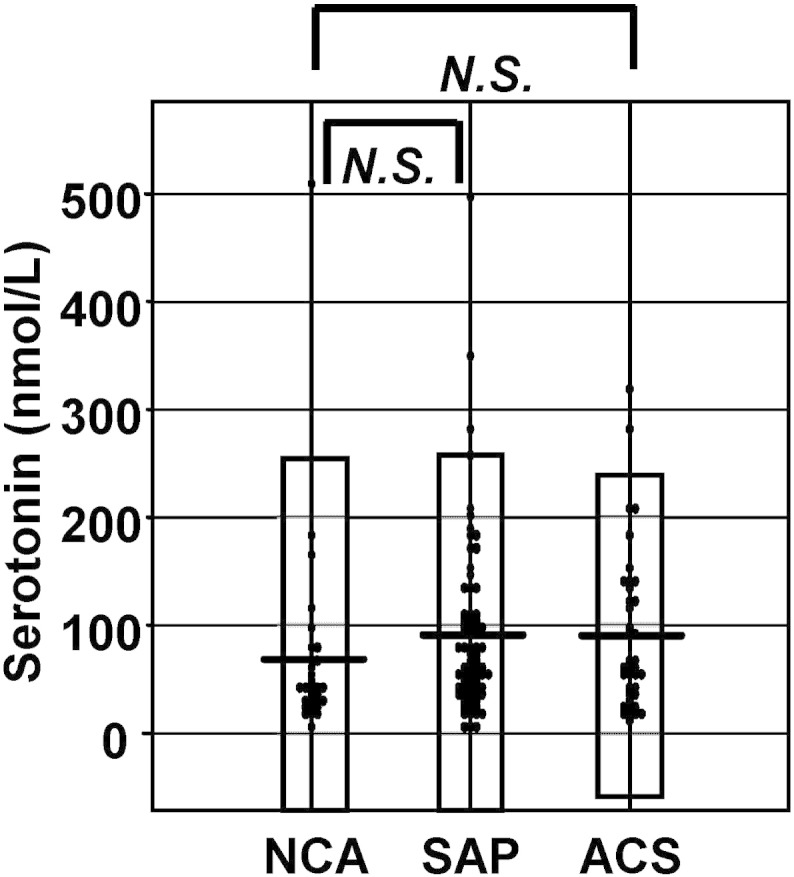

3.4. Serum PS-PLA1 levels showed significant correlation with the plasma LysoPS levels only in ACS group

Although the biosynthetic pathway of LysoPS in vivo has not yet been clearly elucidated, PS-PLA1 has been assumed as the enzyme catalyzing the production of LysoPS utilizing phosphatidylserine (PS) as the substrate [21], [22], [23]. Therefore, we also measured the serum PS-PLA1 level in this study with the assay we had constructed [21]. Considering that recombinant PS-PLA1 concentration is well associated with the activity of PS-PLA1 in vitro [22], the antigen level of PS-PLA1 likely reflects the activity of PS-PLA1, although measuring the activity of PS-PLA1 may be more suitable. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, there were no significant differences in the serum PS-PLA1 level among the NCA, SAP and ACS groups, and no significant correlation between the serum PS-PLA1 and plasma LysoPS levels. When the subjects were confined to ACS, however, the significant correlation between the serum PS-PLA1 and plasma LysoPS levels was observed (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that PS-PLA1 might not determine the plasma LysoPS level in a steady state but that PS-PLA1 somehow affected the plasma LysoPS level in ACS.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the serum PS-PLA1 and plasma LysoPS levels.

(A) Serum PS-PLA1 levels in the NCA, SAP and ACS groups. (B) Correlation between the serum PS-PLA1 and plasma LysoPS levels in all the subjects. (C) Correlation between the serum PS-PLA1 and plasma LysoPS levels separately in NCA, SAP, and ACS groups.

4. Discussion

Platelet activation is one of the events responsible for the development of ACS and is also known to be involved in the subsequent pro-atherosclerotic responses, such as further activation of platelets, migration of inflammatory cells, induction of inflammatory cytokines, and so on [24], [25]. Recently, glycero-LPLs, such as LysoPA, have emerged as novel bioactive lipids, and are proposed as one of the new targets for atherosclerotic diseases [26]. Based on a recent study, we reported that the plasma levels of the glycero-LPLs are increased in subjects with ACS [13]; however, it remained unknown whether activated platelets are involved in the elevation of the plasma glycero-LPLs in vivo and whether any differences might exist among the glycero-LPLs in the pathways by which their levels increased.

In this study, we measured the plasma serotonin level and investigated the correlations between the plasma levels of glycero-LPLs and serotonin, to determine if a specific association might exist between any of the glycero-LPLs and platelet activation in vivo. We observed that plasma serotonin showed a specific significant positive correlation with the plasma LysoPS (Fig. 2), but not with the plasma levels of any of the other glycero-LPLs. Considering that rather strong stimulation is needed for platelets to secrete serotonin [27], [28], it is possible that the strong platelet activation associated with the release of serotonin might be involved in the generation of LysoPS.

Contrary to the specific positive correlation between the plasma serotonin and LysoPS, the plasma concentrations of LysoPA, LysoPE, LysoPG and LysoPI were lower in those who took aspirin regularly (Fig. 3B, D, E, F), suggesting that activation of platelets was somehow involved in the release of these glycero-LPLs. In this study, neither the plasma serotonin levels (Fig. 3A) nor the plasma LysoPS levels (Fig. 3G) were lower in those who took aspirin regularly, whereas in a previous in vitro experiment, aspirin reportedly attenuated the release of serotonin from platelets [29]. One possible explanation was that at the point of collecting blood samples, those subjects who had not been taking aspirin regularly took rather high-dose of aspirin before they entered the catheter lab. Therefore, this different timing of aspirin intake between those who had taken aspirin regularly and those had not might make the interpretation difficult. In any case, we can safely conclude that the dynamism of LysoPS might be somehow different from the other glycero-LPLs based on the analysis on the influence of regular aspirin intake on glycero-LPLs.

One possible mechanism underlying the positive correlation between the plasma serotonin and LysoPS levels might involve PS-PLA1 and its substrate, PS. At present, production of LysoPS from PS is believed to be catalyzed by PS-PLA1 [21], [22], [23]. In the resting state, PS is localized on the inner side of plasma membrane [30], [31] while PS-PLA1 is not expressed in human platelets [23]. Therefore PS is not accessible to PS-PLA1 in the circulation. When platelets are strongly activated, however, this membrane asymmetry is lost and PS can be exposed extracellularly to the plasma/serum milieu in the blood [32]. Moreover, strongly activated platelets secrete PS-containing microparticles into the circulation [32], [33]. Taken together, when platelets are so strongly activated that they secrete serotonin, PS-PLA1 can access its substrate, PS, shifting to the outer membrane of the platelets or residing on microparticles, to produce LysoPS. Regarding the role of PS-PLA1 in determining the plasma LysoPS, we obtained their significant positive correlation in ACS group, but not in NCA or SAP group (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that the plasma LysoPS levels might increase to a greater degree in those who had higher PS-PLA1 in circulation only in the condition where the substrate PS is accessible to PS-PLA1, such as ACS.

Although PS-PLA1 might be somehow involved in the production of LysoPS, other pathways independent of PS-PLA1 might exist, since we have observed the significant positive correlation between the plasma LysoPS level and the plasma serotonin concentration not only in ACS, but also in SAP subjects (r = 0.410, P < 0.001), whose LysoPS had no correlation with PS-PLA1 (Fig. 4C). Actually, when we stimulated washed platelets (which do not contain PS-PLA1) with thrombin, we observed that LysoPS as well as other glycerol–lysophospholipids were secreted (data not shown). Further basic studies are needed to elucidate the source of LysoPS.

Investigation of the source of LysoPS is important for elucidating the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Although the roles of LysoPS, especially in the field of atherosclerotic and thrombotic diseases, remain to be fully elucidated at present, we recently reported that the dual actions of LysoPS on macrophages may have a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic diseases; LysoPS promotes foam cell formation, while it attenuates the expressions of inflammatory mediators [34]. Reportedly, LysoPS exerts several biological actions on the blood cells; it causes degranulation of mast cells [35], [36], suppression of T lymphocyte proliferation [37], and the engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages [38], [39]. Moreover, the receptor for LysoPS has recently been identified [3], [40], which is considered as a new pharmacological target in various fields. Thus, in view of the emerging importance of LysoPS, further investigation of the association between the plasma levels of serotonin and LysoPS will be important.

The main limitation of this study is that we could not measure PF-4 or β-TG, well-known biomarkers for platelet activation other than serotonin, since we prepared the samples without the special anti-platelet cocktail CTAD (needed for the plasma sampling for the assay of these two markers) and were concerned our samples might not be suitable for the measurement of PF-4 or β-TG. Although serotonin is more hardly to increase ex vivo, i.e., after venipuncture, compared with PF-4 or β-TG [20], the determinant factors for the plasma serotonin are not only the secretion from activated platelet, but also the production by enterochromaffin cells in intestine and the uptake of serotonin by platelets and several pathological states of subjects other than platelet activation such as depression and use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor might somehow influence the plasma serotonin level. Therefore, we cannot deny the possibility that LysoPS derived from the other sources than platelets, for example apoptotic endothelial cells generated in ACS. Further studies are needed utilizing the specific biomarkers for platelet activation, such as PF-4 or β-TG, to demonstrate the involvement of platelet activation in the source of glycerol–LPLs in vivo.

Another limitation is that we measured the biomarkers such as PS-PLA1 and glycerol–LPLs in the blood samples taken from the arterial sheaths, while the venous blood samples are ordinarily utilized for the similar clinical studies. Although we measured these biomarkers using the identical blood samples to directly compare related parameters to obtain mechanistic insights into the metabolism of glycerol–LPLs in vivo, the possibility of this sampling difference affecting the data cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the concentrations of biomarkers such as glycerol–LPLs and serotonin in the peripheral blood samples may not represent the exact concentrations in the local lesions, where the pathological events are occurring. Therefore, LysoPS on the surface of platelets, for example, might be more reliable markers for platelet activation than plasma LysoPS.

In summary, we found the existence of a specific positive correlation between the plasma levels of serotonin and LysoPS, a newly reported important lipid mediator. LysoPS production might be related to strong platelet activation, which caused serotonin to be released extracellularly from the cells.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25253040 (Y.Y.) and CREST (15gm0710001h0103) from JST.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Makide K., Kitamura H., Sato Y., Okutani M., Aoki J. Emerging lysophospholipid mediators, lysophosphatidylserine, lysophosphatidylthreonine, lysophosphatidylethanolamine and lysophosphatidylglycerol. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grzelczyk A., Gendaszewska-Darmach E. Novel bioactive glycerol-based lysophospholipids: new data — new insight into their function. Biochimie. 2013;95:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makide K., Uwamizu A., Shinjo Y., Ishiguro J., Okutani M., Inoue A., Aoki J. Novel lysophosphoplipid receptors: their structure and function. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55:1986–1995. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kihara Y., Mizuno H., Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors in drug discovery. Exp. Cell Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sano T., Baker D., Virag T., Wada A., Yatomi Y., Kobayashi T., Igarashi Y., Tigyi G. Multiple mechanisms linked to platelet activation result in lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate generation in blood. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21197–21206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerrard J.M., Robinson P. Identification of the molecular species of lysophosphatidic acid produced when platelets are stimulated by thrombin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;1001:282–285. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siess W., Tigyi G. Thrombogenic and atherogenic activities of lysophosphatidic acid. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;92:1086–1094. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haseruck N., Erl W., Pandey D., Tigyi G., Ohlmann P., Ravanat C., Gachet C., Siess W. The plaque lipid lysophosphatidic acid stimulates platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation in whole blood: involvement of P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors. Blood. 2004;103:2585–2592. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pamuklar Z., Lee J.S., Cheng H.Y., Panchatcharam M., Steinhubl S., Morris A.J., Charnigo R., Smyth S.S. Individual heterogeneity in platelet response to lysophosphatidic acid: evidence for a novel inhibitory pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:555–561. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama K., Kudo I., Inoue K. Phospholipid degradation in rat calcium ionophore-activated platelets is catalyzed mainly by two discrete secretory phospholipase As. J. Biochem. 1995;117:1280–1287. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama K., Shimizu F., Setaka M. Simultaneous separation of lysophospholipids from the total lipid fraction of crude biological samples using two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 2000;41:142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billah M.M., Lapetina E.G. Formation of lysophosphatidylinositol in platelets stimulated with thrombin or ionophore A23187. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:5196–5200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurano M., Suzuki A., Inoue A., Tokuhara Y., Kano K., Matsumoto H., Igarashi K., Ohkawa R., Nakamura K., Dohi T., Miyauchi K., Daida H., Tsukamoto K., Ikeda H., Aoki J., Yatomi Y. Possible involvement of minor lysophospholipids in the increase in plasma lysophosphatidic acid in acute coronary syndrome. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:463–470. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueras J., Domingo E., Cortadellas J., Padilla F., Dorado D.G., Segura R., Galard R., Soler J.S. Comparison of plasma serotonin levels in patients with variant angina pectoris versus healed myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005;96:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanai H., Hirowatari Y. A significant association of plasma serotonin to cardiovascular risk factors and changes in pulse wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012;157:312–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirowatari Y., Hara K., Shimura Y., Takahashi H. Serotonin levels in platelet-poor plasma and whole blood from healthy subjects: relationship with lipid markers and coronary heart disease risk score. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2011;18:874–882. doi: 10.5551/jat.8995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohi T., Miyauchi K., Ohkawa R., Nakamura K., Kishimoto T., Miyazaki T., Nishino A., Nakajima N., Yaginuma K., Tamura H., Kojima T., Yokoyama K., Kurata T., Shimada K., Yatomi Y., Daida H. Increased circulating plasma lysophosphatidic acid in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;413:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okudaira M., Inoue A., Shuto A., Nakanaga K., Kano K., Makide K., Saigusa D., Tomioka Y., Aoki J. Separation and quantification of 2-acyl-1-lysophospholipids and 1-acyl-2-lysophospholipids in biological samples by LC-MS/MS. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55:2178–2192. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D048439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirowatari Y., Hara K., Kamihata H., Iwasaka T., Takahashi H. High-performance liquid chromatographic method with column-switching and post-column reaction for determination of serotonin levels in platelet-poor plasma. Clin. Biochem. 2004;37:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohkawa R., Hirowatari Y., Nakamura K., Ohkubo S., Ikeda H., Okada M., Tozuka M., Nakahara K., Yatomi Y. Platelet release of beta-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4 and serotonin in plasma samples. Clin. Biochem. 2005;38:1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura K., Igarashi K., Ohkawa R., Saiki N., Nagasaki M., Uno K., Hayashi N., Sawada T., Syukuya K., Yokota H., Arai H., Ikeda H., Aoki J., Yatomi Y. A novel enzyme immunoassay for the determination of phosphatidylserine-specific phospholipase A(1) in human serum samples. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2010;411:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T., Aoki J., Nagai Y., Dohmae N., Takio K., Doi T., Arai H., Inoue K. Serine phospholipid-specific phospholipase A that is secreted from activated platelets A new member of the lipase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2192–2198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoki J., Nagai Y., Hosono H., Inoue K., Arai H. Structure and function of phosphatidylserine-specific phospholipase A1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1582:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrell C.N., Aggrey A.A., Chapman L.M., Modjeski K.L. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood. 2014;123:2759–2767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-462432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Hundelshausen P., Schmitt M.M. Platelets and their chemokines in atherosclerosis—clinical applications. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:294. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spector A.A. Plaque rupture, lysophosphatidic acid, and thrombosis. Circulation. 2003;108:641–643. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000082307.85449.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnamurthi S., Joseph S., Kakkar V.V. Synergistic potentiation of 5-hydroxytryptamine secretion by platelet agonists and phorbol myristate acetate despite inhibition of agonist-induced arachidonate/thromboxane and beta-thromboglobulin release and Ca2+ mobilization by phorbol myristate acetate. Biochem. J. 1986;238:193–199. doi: 10.1042/bj2380193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowley S.T., Dempsey E.C., Horwitz K.B., Horwitz L.D. Platelet-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation is modulated by the growth amplification factors serotonin and adenosine diphosphate. Circulation. 1994;90:1908–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai T.H., Tsai W.J., Chen C.F. Aspirin inhibits collagen-induced platelet serotonin release, as measured by microbore high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1995;669:404–407. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeung T., Gilbert G.E., Shi J., Silvius J., Kapus A., Grinstein S. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science. 2008;319:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1152066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leventis P.A., Grinstein S. The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010;39:407–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan X., Shi J., Fu Y., Gao C., Yang X., Li J., Wang W., Hou J., Li H., Zhou J. Role of erythrocytes and platelets in the hypercoagulable status in polycythemia vera through phosphatidylserine exposure and microparticle generation. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;109:1025–1032. doi: 10.1160/TH12-11-0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freyssinet J.M., Toti F. Formation of procoagulant microparticles and properties. Thromb. Res. 2010;125(Suppl. 1):S46–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishikawa M., Kurano M., Ikeda H., Aoki J., Yatomi Y. Lysophosphatidylserine has bilateral effects on macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2015;22:518–526. doi: 10.5551/jat.25650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin T.W., Lagunoff D. Interactions of lysophospholipids and mast cells. Nature. 1979;279:250–252. doi: 10.1038/279250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith G.A., Hesketh T.R., Plumb R.W., Metcalfe J.C. The exogenous lipid requirement for histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells stimulated by concanavalin A. FEBS Lett. 1979;105:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80887-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellini F., Bruni A. Role of a serum phospholipase A1 in the phosphatidylserine-induced T cell inhibition. FEBS Lett. 1993;316:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81724-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frasch S.C., Fernandez-Boyanapalli R.F., Berry K.Z., Leslie C.C., Bonventre J.V., Murphy R.C., Henson P.M., Bratton D.L. Signaling via macrophage G2A enhances efferocytosis of dying neutrophils by augmentation of Rac activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:12108–12122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.181800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frasch S.C., Fernandez-Boyanapalli R.F., Berry K.A., Murphy R.C., Leslie C.C., Nick J.A., Henson P.M., Bratton D.L. Neutrophils regulate tissue neutrophilia in inflammation via the oxidant-modified lipid lysophosphatidylserine. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:4583–4593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.438507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue A., Ishiguro J., Kitamura H., Arima N., Okutani M., Shuto A., Higashiyama S., Ohwada T., Arai H., Makide K., Aoki J. TGFalpha shedding assay: an accurate and versatile method for detecting GPCR activation. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1021–1029. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.