Abstract

Background

Recent work has demonstrated the codevelopment of personality traits and alcohol use characteristics from early adolescence to young adulthood. Few studies, however, have tested whether alcohol use initiation impacts trajectories of personality over this time period. We examined the effect of alcohol use initiation on personality development from early adolescence to young adulthood.

Methods

Participants were male (nmen = 2,350) and female (nwomen = 2,618) twins and adoptees from 3 community-based longitudinal studies conducted at the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research. Data on personality traits of Positive Emotionality (PEM; Well-being), Negative Emotionality (NEM; Stress Reaction, Alienation, and Aggression), and Constraint (CON; Control and Harm Avoidance)—assessed via the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ)—and age of first drink were collected for up to 4 waves spanning ages 10 to 32.

Results

Alcohol use initiation was associated with significant decreases in levels of Well-being and CON traits, most notably Control; and significant increases in levels of all NEM traits, particularly Aggression. In general, the effects of alcohol use initiation on personality traits were moderated by gender and enhanced among those with earlier age of first drink.

Conclusions

From early adolescence to young adulthood, alcohol use initiation predicts deviations from normative patterns of personality maturation. Such findings offer a potential mechanism underlying the codevelopment of personality traits and alcohol use characteristics during this formative period of development.

Keywords: Personality Traits, Alcohol Use Initiation, Adolescence, Young Adulthood

Links between personality traits and alcohol use are well established (Littlefield and Sher, 2010). Individuals with drinking problems (vs. those without) have higher scores on traits of Negative Emotionality (NEM—the tendency to break down under stress; become easily agitated and hostile toward others; Jackson and Sher, 2003); lower scores on traits of Constraint (CON—the ability to inhibit impulses, plan, and avoid risk; Dom et al., 2006), and higher scores on some traits of Positive Emotionality (PEM—e.g., Well-being; Elkins et al., 2004).

Recent studies highlight the codevelopment of personality traits and alcohol use characteristics from adolescence to young adulthood (e.g., Littlefield et al., 2009, 2010; Quinn and Harden, 2013) and suggest that changes in one should be evaluated in the context of changes in the other. Two developmental models are relevant to this issue. A precursor model posits that traits increase risk for alcohol use. In support of this, prospective studies have found that higher scores on NEM traits and lower scores on CON and PEM traits predict subsequent increases in drinking during adolescence and young adulthood (MacPherson et al., 2010; Sher et al., 2000) and are linked to an earlier age of first drink (Malmberg et al., 2012; McGue et al., 2001).

An alternative model, which has received less attention in the literature, posits that alcohol use may affect the normative maturation of personality from adolescence to adulthood (Chassin and Haller, 2010; White et al., 2011). Specifically, most individuals decrease on NEM traits and increase on CON and PEM traits as they enter young adulthood (Donnellan et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2006). However, there is significant individual-level variability in trait trajectories across this period (Vaidya et al., 2008), particularly during adolescence (Soto et al., 2011). Alcohol use initiation, which typically occurs during adolescence, is a common life event that may partly account for these patterns. There are relatively few tests of whether the timing of alcohol use initiation accounts for variation in the development of personality traits; however, some studies have found earlier age of first drink to predict decreases in traits related to CON (White et al., 2011; Zernicke et al., 2010).

The Present Study

Using a large, mixed-gender sample spanning preadoles-cence (age 10) through young adulthood (age 32), we examined the extent to which alcohol use initiation had a discontinuous effect on the trajectories of personality traits of PEM (i.e., Well-being), NEM (i.e., Stress Reaction, Alienation, and Aggression), and CON (i.e., Control and Harm Avoidance). Specifically, we tested whether there was a change in the levels of these traits following alcohol initiation —over and above that predicted by aging alone. Further, we also explored whether effects of alcohol use initiation on trait levels were moderated by gender or timing of drinking onset. The later provides a test of the sensitive period hypothesis, which posits that the effect of drinking onset on risk for later alcohol problems may be magnified during early adolescence (DeWit et al., 2000).

We predicted alcohol use initiation would be associated with decreases in levels of Well-being and CON traits and increases in levels of NEM traits. We also predicted that traits previously shown to exhibit gender × time interactions during the transition from adolescence and young adulthood would also exhibit significant gender moderation in terms of the effect of alcohol initiation on trait levels. For example, prior research has observed larger increases in neuroticism and CON traits among girls than boys (Blonigen et al., 2008; Soto et al., 2011); thus, we predicted that the effects of alcohol use initiation on levels of Stress Reaction and CON traits to be larger among girls than boys. Finally, given that prior work has found an early versus later onset of drinking is associated with elevated lifetime rates of alcohol use disorders (AUD; Agrawal et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2008), and lower levels of PEM and CON traits, and higher levels of NEM traits (Hill et al., 2000; Malmberg et al., 2012), we predicted that the effects alcohol initiation on trait levels would be greater among those with earlier age of first drink.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

Participants were members of 3 ongoing, longitudinal epidemiological studies conducted at the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (MCTFR; Iacono et al., 2006): Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS; Iacono et al., 1999); Enrichment Study (MTFS-ES; Keyes et al., 2009); and Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS; McGue et al., 2007)—an adoption study. For all studies, families were eligible if they met the familial relationship conditions of the relevant study, lived within a day’s drive of the MCTFR laboratories, and the targeted children did not have cognitive or physical disabilities that would preclude participation in the day-long assessment.

For the MTFS and MTFS-ES, same-sex twins born in Minnesota from 1972 to 1984 and 1988 to 1994, respectively, were identified and located via public birth records. For the MTFS, families were recruited to participate the year the twins turned either 11 (n = 1,512) or 17 years old (n = 1,252). For the MTFS-ES, families were recruited the year the twins turned 11 years old (n = 998), and additional screening procedures were employed to ensure that one-half of participating families had at least 1 twin with conduct problems. For any given birth year, over 90% of twin families were located and over 80% of those who were eligible agreed to participate. Participating families were representative of the demographic profile of Minnesotans during the target birth years (Iacono et al., 1999; Keyes et al., 2009). Participants across the 2 studies were predominantly of European American ancestry (96%) and slightly more women (52%) than men.

The SIBS consists of 409 and 208 adoptive and nonadoptive families, respectively (n = 1,232), each with 2 siblings within 5 years of age of one another and between ages of 11 and 21 years old at intake. Adoptive families were identified from private adoption agencies in Minnesota and included 2 unrelated siblings (63.2% participation rate). Approximately two-thirds of adoptions were international (primarily East Asian ancestry) with a mean age of placement of 4.7 months (SD = 3.4). Nonadoptive families were ascertained via public birth records and selected to include a pair of biological siblings comparable in age and gender to adoptive sibling pairs (57.3% participation rate). Across all sibling pairs, small majorities were same-sex (60.8%), female (54.9%), and of European American ancestry (55.8%; the other major racial/ethnic groups were composed of Korean adoptees).

Participants from each study were invited to return for follow-up assessments every 3 to 5 years. Despite ongoing and/or unequal number of assessments across participants, aggregation of the data across all samples and follow-up assessments allowed for modeling of the data across ages 10 to 32. The age distribution and number of participants across each wave of assessment are shown in Table 1. Wave 1 denotes the intake assessment and thus includes the total number of participants across all studies. The first follow-up assessment (Wave 2) has been completed for all studies (92.1% retention rate). Across the remaining waves, the decreasing N is a function of ongoing assessments and study design. Ongoing assessments included the second follow-up for the MTFS-ES and SIBS (Wave 3) and Wave 4 for the MTFS-ES. Participants from the MTFS age 17 cohort had completed all scheduled assessments (Waves 1 to 4). MTFS assessments are scheduled to terminate when participants reach about age 30. SIBS participants are only scheduled to complete 3 waves of assessment. The mean true retention rate was approximately 90% across all completed follow-up assessments for each of the 3 studies and across different age and gender cohorts in the MTFS and MTFS-ES.

Table 1.

Number of Participants of Each Age at Each Assessment Wave

| Age | Assessment Wave 1 |

Assessment Wave 2 |

Assessment Wave 3 |

Assessment Wave 4 |

Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 11 | 104 | 104 | |||

| 12 | 119 | 119 | |||

| 13 | 255 | 5 | 260 | ||

| 14 | 1,047 | 82 | 1 | 1,130 | |

| 15 | 878 | 110 | 988 | ||

| 16 | 762 | 153 | 915 | ||

| 17 | 1,152 | 795 | 1,947 | ||

| 18 | 479 | 742 | 1,221 | ||

| 19 | 99 | 375 | 49 | 523 | |

| 20 | 32 | 465 | 14 | 511 | |

| 21 | 16 | 238 | 23 | 277 | |

| 22 | 2 | 41 | 19 | 62 | |

| 23 | 20 | 127 | 97 | 244 | |

| 24 | 38 | 335 | 530 | 930 | |

| 25 | 83 | 408 | 423 | 15 | 929 |

| 26 | 17 | 90 | 76 | 3 | 186 |

| 27 | 8 | 15 | 19 | 1 | 43 |

| 28 | 3 | 25 | 131 | 99 | 258 |

| 29 | 23 | 117 | 453 | 376 | 969 |

| 30 | 8 | 38 | 100 | 119 | 265 |

| 31 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 13 | 34 |

| 32 | 1 | 1 |

Assessment

Personality

Personality was assessed with the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen and Waller, 2008). This self-report questionnaire measures individuals’ typical affective and behavioral styles using a higher-order 3-factor structure of PEM, NEM, and CON. For the primary scales that were included in this study, the range of Cronbach’s alpha across the most common assessment ages (14, 17, 20, 24, and 29) is presented below. PEM captures a propensity to experience positive emotions and was measured in the current study by the primary scale of Well-being (α = 0.88 to 0.92). NEM captures a propensity to experience negative emotions and comprises scales of Stress Reaction (α = 0.87 to 0.90), Alienation (α = 0.87 to 0.92), and Aggression (α = 0.87 to 0.91). CON taps a tendency to be planful and cautious and averse to risk, and was measured in the current study by the primary scales of Control (α = 0.84 to 0.88) and Harm Avoidance (α = 0.84 to 0.87).

These 6 primary scales were selected for analysis because they (i) have each been linked to drinking problems during adolescence and/or young adulthood (Dom et al., 2006; Elkins et al., 2004; Jackson and Sher, 2003) and (ii) were administered at each assessment wave in MCTFR studies. Specifically, the 198-item version of the MPQ was administered at the ages 17, 24, and 29 assessments of the MTFS and MTFS-ES. An abbreviated version of the MPQ that included only scales of Well-being, Stress Reaction, Alienation, Aggression, Control, and Harm Avoidance was administered to twins at the age 14 assessment and to female twins from the age 17 cohort at their age 20 assessment. SIBS participants 16 years of age and older completed the 198-item version of the MPQ, while those younger than 16 years old completed the abbreviated MPQ. All MPQ data prior to age 13 were collected from SIBS participants. For any given assessment, 83 to 93% of participants had MPQ data. Across all studies, 1,340 and 632 participants had personality data at 3 and 4 waves of assessment, respectively. Per Little’s MCAR test, these data for the MPQ scales were missing completely at random (χ2 (82) = 101.94, p = 0.067).

Alcohol Use Initiation and Other Drinking Characteristics

At each assessment, participants were asked information on their history and pattern of drinking, which included the following question —”How old were you the first time you drank alcohol (on your own; more than your parents allowed you to)?”—as part of the Substance Abuse Module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins et al., 1988) (M = 15.9 years; SD = 2.2; range = 5.0 to 24.5). Among those who had ever consumed alcohol, the average frequency of drinking in the past 12 months was less than once per month at age 14, once per month at age 17, and 2 to 3 times per month at ages 20 and 24. The average number of drinks on a typical drinking day in the past 12 months was 2.1 (SD = 2.6) at age 14, 3.3 (SD = 3.5) at age 17, 4.3 (SD = 3.5) at age 20, and 3.5 (SD = 2.7) at age 24.

Statistical Analyses

For each trait, multilevel models were fit in HLM 7.0 (Scientific Software International Inc., Skokie, IL) to test (i) for effects of alcohol use initiation on the levels of MPQ traits and (ii) whether effects of initiation were moderated by gender or timing of drinking onset. Each model included 3 levels to account for nesting of participants within families and assessments within participants: Level 3 (nesting of participants within families); Level 2 (individual participants); and Level 1 (repeated measures across time within participants).

The following choices were made when modeling MPQ trait trajectories. First, as indicated by Durbin and colleagues’ (in press) analysis of this data set, models that include linear and nonlinear (i.e., quadratic and cubic) effects of age provide the best fit to the MPQ trait trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood (see also Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011). Thus, both linear and nonlinear effects of age were included in the models for this study. Data were included for up to 4 waves for each participant, and because participants varied in chronological age at the time of each assessment, change was modeled as a function of participants’ actual chronological ages at each assessment. We centered age at the first assessment wave (age 11). Although the number of participants was smaller for the earliest ages (11 to 14) than for ages 17 and older, we wanted to generate the most robust estimates for trait levels across the full developmental span covered in the sample so as to more accurately estimate the effect of alcohol initiation on traits, beyond the effects of age-related change. Second, we modeled age-related change in traits as fixed effects estimated for the sample as a whole, while the effect of alcohol initiation was allowed to vary across participants. Per Durbin and colleagues (in press), models in which linear and nonlinear effects are freely estimated did not provide a better fit than models in which they were fixed (i.e., models without random effects for the change parameters did not fit worse than models with the additional random effects). Third, effects of alcohol initiation on trait levels were modeled as within-subjects effects (time-varying coefficients at Level 1); thus, only participants who had MPQ data for at least 1 assessment prior and 1 following their age of drinking onset contributed to the estimation of parameters for the effects of alcohol initiation on trait levels.

To examine initiation effects, we entered a time-varying predictor at Level 1 (ALC NO/YES) to account for participant-specific timing of this event and its effect on trait elevation across the sample. A value of 0 was entered for this variable at Level 1 for each assessment prior to participants’ age of first drink, and a value of 1 was entered for each assessment wave after age of first drink. This allowed for tests of within-subject differences in trait levels before versus after drinking onset, that is, the extent to which alcohol use initiation was associated with subsequent differences in trait levels above and beyond the effects of age-related change, with age centered at 11:

Due to the number of data points before and after the typical age of initiation, we were unable to contrast slopes and examine effects of alcohol use initiation on rate of linear or nonlinear change in traits over time. Consequently, the initiation effects (and the graphs to be presented) only demonstrate, in the context of the average trait trajectory, the magnitude of the change in trait levels immediately after the average age of alcohol initiation, not the impact of initiation effects in the rate of change in traits over time. Next, for traits in which alcohol use initiation was associated with subsequent differences in trait levels before versus after drinking onset, we tested separate models in which gender and age of first drink moderated the magnitude of the initiation effects on trait levels. These moderators were entered at Level 2 as predictors of variation in the Level 1 effect of alcohol use initiation:

For the final moderation models, we accounted for the main effects of gender and age of first drink on the basic change parameters (i.e., intercept, age, age2, and age3) of each trait; that is, the moderator analyses included either gender or age of first drink as a significant Level 2 predictor of the Level 1 effects of these change parameters.

RESULTS

Model Fitting Results for the Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation

The fit of models that included only age-related (linear and nonlinear) change versus models that also included effects of alcohol initiation was compared using Akaike’s information criterion (AIC; lower values indicate a better fit to the data)—see Table 2. For each trait, a model that included the effects of initiation provided a better fit than a model that included only age-related change.

Table 2.

AIC Values for the Best-Fitting Models of Age-Related Change in MPQ Personality Traits Versus Models that Include an Effect of Alcohol Use Initiation on Level of the MPQ Traits

| Models |

||

|---|---|---|

| Trait | Linear + nonlinear age-related change |

Age-related change + effects of initiation |

| Well-being | 77340.57 | 67211.96 |

| Stress Reaction | 80307.65 | 69811.06 |

| Alienation | 79092.42 | 68598.05 |

| Aggression | 79598.00 | 68934.68 |

| Control | 77182.75 | 66875.31 |

| Harm Avoidance | 81904.56 | 77104.79 |

N = 3,211. AIC = Akaike’s information criterion. MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Linear + nonlinear age-related change = models that include effects for linear, quadratic, and cubic age-related change in traits over time. Age-related change + effects of initiation = models that include effects for linear, quadratic, and cubic age-related change in traits over time and an effect of alcohol use initiation on level of the MPQ traits. Lower AIC values denote better fit.

Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation on the Level of Personality Traits

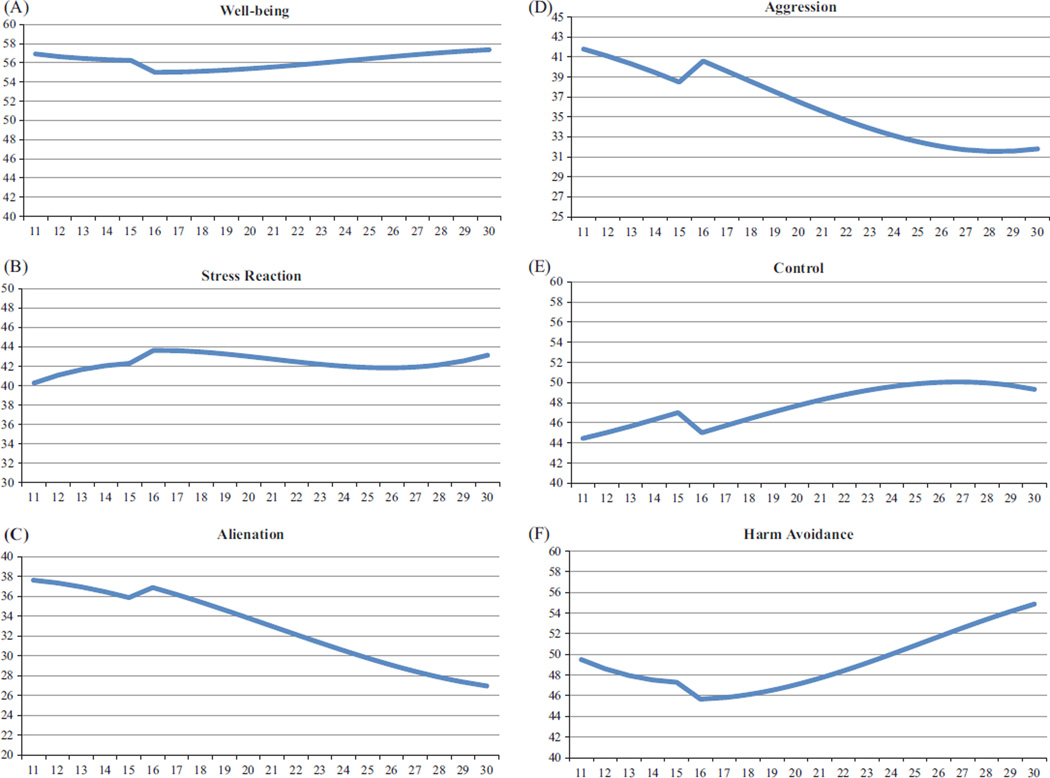

Table 3 shows the results of the best-fitting models, which tested whether there were significant differences in levels of MPQ traits before versus after drinking onset (accounting for effects of age-related change on traits, i.e., initial intercept; and age, age2, and age3 slopes). Effects of alcohol use initiation on trait level were significant for all traits. For Well-being and both CON traits, there were significant decreases in the level of these traits after drinking onset. Conversely, for NEM scales, there were significant increases in the level of all traits after drinking onset. A graphical representation of the age-related effects and initiation effects for each trait at the mean age of drinking onset (i.e., age 16) is provided in Fig. 1. To facilitate interpretation of initiation effects, we used the grand SD for each trait (Well-being = 7.98; Stress Reaction = 9.37; Alienation = 9.01; Aggression = 9.66; Control = 8.17; Harm Avoidance = 10.86) to express the initiation effects in terms of their size relative to the scale SD. For example, after the onset of drinking, the level of Well-being decreased by 0.16 SD (i.e., 1.24/7.98), and levels of Control and Harm Avoidance decreased by 0.33 and 0.15 SD, respectively, whereas levels of Stress Reaction, Alienation, and Aggression increased by 0.13, 0.18, and 0.32 SD, respectively.

Table 3.

Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation on the Level of MPQ Personality Traits

| Trait | Intercept (SE) | Age (SE) | Age2 (SE) | Age3 (SE) | Effect of initiation on trait level (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | 56.92*** (0.68) | −0.31 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.02) | −0.001* (0.0006) | −1.24*** (0.24) |

| Stress Reaction | 40.27*** (0.72) | 0.92*** (0.24) | −0.12*** (0.02) | 0.004*** (0.0006) | 1.26*** (0.27) |

| Alienation | 37.61*** (0.73) | −0.23 (0.24) | −0.06** (0.02) | 0.002*** (0.0006) | 1.66*** (0.26) |

| Aggression | 41.78*** (0.75) | −0.63* (0.24) | −0.06** (0.02) | 0.003*** (0.0006) | 3.08** (0.26) |

| Control | 44.46*** (0.65) | 0.55* (0.21) | 0.03 (0.02) | −0.002** (0.0006) | −2.69*** (0.23) |

| Harm Avoidance | 49.50*** (0.86) | −1.02*** (0.28) | 0.13*** (0.03) | −0.003*** (0.0007) | −1.60*** (0.27) |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

N = 3,211. MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

“Intercept” values reflect model-derived scores at age 11. Values for “age,” “age2,” and “age3” reflect the linear, quadratic, and cubic change, respectively, per year in that scale after the age of the intercept. The values for “effect of initiation on trait level” reflect the extent to which the level of a trait changed after the onset of drinking.

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of age-related change in Well-being (Panel A), Stress Reaction (Panel B), Alienation (Panel C), Aggression (Panel D), Control (Panel E), and Harm Avoidance (Panel F) from early adolescence to young adulthood, and the effects of alcohol use initiation on level of these traits at the mean age of initiation (age 16).

Moderation of Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation on the Level of Personality Traits by Gender and Age of First Drink

Tables 4 and 5 provide the results of exploratory models that tested (separately) whether the initiation effects were moderated by gender and age of first drink, respectively. Specifically, either gender or age of first drink was entered at Level 2 in the model as a predictor of variation in the Level 1 effect of alcohol use initiation. These effects are denoted as “gender on initiation effects” and “age of first drink on initiation effects” in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. For the sake of parsimony, the parameter estimates of the main effects of gender and age of first drink on the Level 1 basic change parameters are not presented in these tables, but are available upon request from the first author.

Table 4.

Moderation of Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation on the Level of MPQ Personality Traits by Gender

| Level 1 predictors |

Level 2 predictors |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Intercept (SE) | Age (SE) | Age2 (SE) | Age3 (SE) | Effects of initiation on trait level (SE) |

Gender on initiation effects (SE) |

Sex-specific initiation effects |

|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Well-being | 56.92*** (0.68) | −0.30 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.02) | −0.001* (0.0006) | −1.22*** (0.27) | −0.03(0.18) | −1.25 | −1.22 |

| Stress Reaction | 39.88*** (0.94) | 1.21** (0.31) | −0.15** (0.03) | 0.005*** (0.0007) | 1.82*** (0.39) | −0.37 (0.36) | 1.45 | 1.82 |

| Alienation | 37.66*** (0.73) | −0.26 (0.24) | −0.06** (0.02) | 0.002*** (0.0006) | 1.50*** (0.30) | 0.26 (0.20) | 1.76 | 1.50 |

| Aggression | 43.54*** (0.98) | −1.33** (0.30) | −0.003* (0.03) | 0.001*** (0.0007) | 2.38*** (0.36) | 1.93*** (0.37) | 4.31 | 2.38 |

| Control | 43.32*** (0.87) | 0.99** (0.28) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.004* (0.0006) | −2.33*** (0.30) | −0.83*** (0.22) | −3.16 | −2.33 |

| Harm Avoidance | 48.59*** (1.12) | −0.13 (0.34) | 0.05 (0.03) | −0.0008 (0.0008) | −0.89* (0.38) | −1.23* (0.39) | −2.12 | 0.89 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

N = 3,211. Gender (1 = male). “Intercept” values reflect model-derived scores at age 11. Values for “age,” “age2,” and “age3” reflect the linear, quadratic, and cubic change, respectively, per year in that scale after the age of the intercept. “Gender on initiation effects” reflects the effect of including gender at Level 2 as a predictor of individual differences in the initiation effects at Level 1. This coefficient denotes whether the magnitude of the effects of alcohol use initiation on a trait level was significantly different between men and women.

Table 5.

Moderation of Effects of Alcohol Use Initiation on the Level of Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire Personality Traits by Age of First Drink

| Level 1 predictors |

Level 2 predictors |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Intercept (SE) | Age (SE) | Age2 (SE) | Age3 (SE) | Effects of initiation on trait level (SE) |

Age of first drink on initiation effects (SE) |

Age-specific initiation effects |

|

| −1 SD |

+1 SD |

|||||||

| Well-being | 56.51** (2.08) | 0.27 (0.33) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.0001 (0.0008) | −7.01** (2.42) | 0.30** (0.13) | −2.10 | −1.58 |

| Stress Reaction | 50.05*** (3.60) | −1.53* (0.67) | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.0004*** (0.00008) | 9.15*** (2.53) | −0.47*** (0.14) | 2.71 | 0.64 |

| Alienation | 59.20*** (7.77) | −6.83** (2.30) | −0.51* (0.21) | −0.01* (0.006) | 11.01*** (2.68) | −0.54*** (0.15) | 3.61 | 1.24 |

| Aggression | 55.54** (2.19) | −0.89* (0.35) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.002* (0.0008) | 3.55 (2.51) | −0.06 (0.13) | 5.81 | 2.73 |

| Control | 15.19** (5.76) | 6.11** (1.72) | −0.40(0.16) | 0.009 (0.005) | −7.63*** (2.20) | 0.36** (0.12) | ||

| Harm Avoidance | 36.03*** (1.11) | −0.57 (0.39) | 0.08* (0.03) | −0.002* (0.0009) | 0.08 (2.79) | 0.05 (0.15) | 0.76 | 0.98 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

N = 3,211. “Intercept” values reflect model-derived scores at age 11. Values for “age,” “age2,” and “age3” reflect the linear, quadratic, and cubic change, respectively, per year in that scale after the age of the intercept. “Age of first drink on initiation effects” reflects the effect of including age of first drink (centered) at Level 2 as a predictor of individual differences in the initiation effects at Level 1. This coefficient denotes whether the magnitude of the effect of alcohol use initiation on a trait level varied significantly as a function of the timing of alcohol use initiation. The “Age-specific initiation effects” gives the respective effects of alcohol use initiation on trait levels at 1 SD below and 1 SD above the mean age of first drink.

Per Table 4, gender was a significant moderator of the initiation effects for Aggression, Control, and Harm Avoidance, that is, the magnitudes of the effect of alcohol use initiation on these trait levels were significantly different between men and women. For Aggression, there were increases for both men and women; however, the effect was larger in men. For Control, there were decreases for both men and women after drinking onset, although the effect was larger in men. For Harm Avoidance, there was a significant decrease for men, but minimal change for women.

Per Table 5, age of first drink was a significant moderator of the initiation effects for most traits, with the exception of Aggression and Harm Avoidance, that is, the magnitude of the effect of alcohol use initiation on a trait level varied significantly as a function of the timing of alcohol use initiation. Based on the age-specific initiation effects (1 SD below [≤13.7 years] and 1 SD above [≥18.1 years] the mean age of initiation), the initiation effect for each trait was enhanced among those with an earlier age of first drink. Specifically, for Well-being and Control, decreases in the levels of these traits as a function of drinking onset were larger for those with an earlier (vs. later) age of onset, whereas for Stress Reaction and Alienation, increases in the levels of these traits as a function of drinking onset were larger for those with an earlier (vs. later) age of onset.

DISCUSSION

This study tested whether alcohol use initiation impacted trajectories of personality development from early adolescence to young adulthood. Alcohol use initiation was associated with changes in levels of all trait trajectories examined; that is, levels of Well-being and CON traits (Control and Harm Avoidance) decreased after the onset of drinking, whereas levels of NEM traits (Stress Reaction, Alienation, and Aggression) increased after drinking onset. Notably, the magnitudes of these effects were greatest for Control and Aggression—2 of the strongest trait-based predictors of problematic drinking during the transition to adulthood (Elkins et al., 2006; Krueger, 1999).

The current findings help to refine models regarding the association between personality and alcohol use characteristics during adolescence and young adulthood (Littlefield et al., 2012; Quinn and Harden, 2013). Specifically, prior prospective studies have tended to focus on a precursor model, observing that higher NEM traits and lower CON and PEM traits are linked to an earlier age of first drink (Malmberg et al., 2012; McGue et al., 2001) and predict subsequent increases in drinking during adolescence and young adulthood (MacPherson et al., 2010; Sher et al., 2000). The current findings support an alternative model in which alcohol use affects the developmental trajectories of personality traits during this developmental timeframe. Indeed, these 2 models are not mutually exclusive as the effects between personality and alcohol use may operate in a reciprocal fashion. For example, Malmberg and colleagues (2013) reported reciprocal effects between onset of substance use and traits related to CON (i.e., sensation-seeking and impulsivity).

The present study did not test for reciprocal effects per se; however, the findings complement prior tests of the precursor model by suggesting that alcohol use initiation is not simply predicted by deviations from normative patterns of personality maturation, but may also predict such patterns of development. Collectively, support for the 2 models aligns with the corresponsive principle of personality development, which posits that life experiences enhance the traits that lead people into those experiences in the first place (Roberts et al., 2003). This principle has been shown to be applicable to the association between personality development and work experiences and marital quality—for example, Le and colleagues (2013)—but to our knowledge has not previously been applied to alcohol use characteristics. The present findings suggest that the corresponsive principle may serve as a useful theoretical framework to describe the codevelopment of personality and drinking during adolescence and young adulthood.

Another notable finding from our analyses was that the strength and directions of the initiation effects were moderated by gender and timing of drinking onset. Regarding gender, changes in the levels of most traits following initiation were in the same directions for men and women, but served to magnify gender differences in these traits during adolescence and young adulthood; that is, prior research has found Stress Reaction, Control, and Harm Avoidance to be higher among women than men during these periods, and traits of Alienation and Aggression, to be higher among men than women (Blonigen et al., 2008; Soto et al., 2011). The effects of alcohol use initiation enhanced these gender differences. Notably, changes in levels of Harm Avoidance diverged somewhat for men and women such that the onset of drinking was followed by increases among men in risk-taking tendencies, but no change in such tendencies for women. These findings suggest that transactions between personality development and alcohol use may follow distinct pathways to problematic drinking for men and women (Hicks et al., 2007).

The findings for moderation by age of first drink highlight the salience of this variable within the addiction literature. Earlier age of first drink may have detrimental consequences on brain development (Clark et al., 2008) and has been consistently linked to increased risk for AUD (Agrawal et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2008). Given that high NEM and low CON trait levels are robust predictors of AUD, the current findings in which earlier age of initiation was associated with greater increases in NEM and decreases in CON may account for why an early onset of drinking increases risk for developing AUD. Further, this finding suggests that the relevance of the corresponsive principle may not be uniform across development, with personality development more sensitive to effects of life events at some ages than others (DeWit et al., 2000). Specifically, effects of alcohol use initiation on levels of trait trajectories may be stronger when the onset of drinking occurs early in adolescence.

Although this study had several strengths including a large community-based, mixed-gender sample and prospective design over 4 time points, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, personality was assessed only via self-report questionnaires. Use of informant reports and behavioral tasks in future work will help corroborate the present findings and identify which effects are robust across assessment methods. Second, although the racial and ethnic profile of participants was consistent with the demographics of the particular geographic region and cohort, it was primarily of European American descent. Thus, generalizability of the findings may be limited. Third, for the sake of simplicity, our analysis of alcohol use characteristics was limited to age of first drink rather than regular or hazardous drinking patterns, for example binge drinking. However, age of first drink is a strong predictor of AUD and is therefore a variable of tremendous significance within the broader addiction literature. Finally, although our models of within-subject change provide a strong test of the “effect” of alcohol use initiation on personality trait development, true causal influence cannot be assumed.

In summary, alcohol use initiation predicted deviations from normative patterns of personality maturation during early adolescence to young adulthood. Future studies should examine these effects in concert with tests of the precursor model (cf., Malmberg et al., 2013), as well as examine whether reciprocal effects between personality traits and alcohol use characteristics are relevant for other drinking milestones (e.g., onset of AUD symptoms). Such studies would greatly expand our understanding of the interplay between personality and alcohol use characteristics during the formative years of adolescence and young adulthood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by USPHS grants DA 05147, AA 09367, DA 13240, and DA 034606. DMB was supported by a Career Development Award from VA Office of Research and Development (Clinical Science Research & Development). BMH was supported by K01 DA 025868. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Footnotes

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal A, Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Grant JD, Pergadia ML, Grucza R, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PAF, Martin NG, Heath AC. Evidence for an interaction between age at first drink and genetic influences on DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptoms. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2047–2056. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Carlson MD, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Stability and change in personality traits from late adolescence in early adulthood: a longitudinal twin study. J Pers. 2008;76:229–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Haller NM. The reciprocal influence of perceived risk for alcoholism and alcohol use over time: evidence for aversive transmission of parental alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:588–596. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Tapert SF. Alcohol, psychological dysregula-tion, and adolescent brain development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. Age of first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom G, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Differences in impulsivity and sensation seeking between early- and late-onset alcoholics. Addict Behav. 2006;31:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Conger RD, Burzette RG. Personality development from late adolescence to young adulthood: differential stability, normative maturity, and evidence for the maturity-stability hypothesis. J Pers. 2007;75:237–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Johnson W, Iacono WG, McGue M. Personality trait change from late childhood to young adulthood: evidence for nonlinearity and sex differences in change. Eur J Pers. in press doi: 10.1002/per.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, King SM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Personality traits and the development of nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drug disorders: prospective links from adolescence to young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:26–39. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Malone S, Iacono WG. The effect of parental alcohol and drug disorders on adolescent personality. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:670–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Tucker-Drob EM. Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: further evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol. 2011;47:739–746. doi: 10.1037/a0023279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Kramer M, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Gender differences and developmental change in externalizing disorders from late adolescence to early adulthood: a longitudinal-twin study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:433–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota twin family study. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M, Krueger RF. Minnesota center for twin and family research. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:978–984. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: a prospective state-trait analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:599–613. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The Enrichment Study of the Minnesota Twin Family Study: increasing yield of twin families at high risk for externalizing psy-chopathology. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:489–501. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. Personality traits in late adolescence predict mental disorders in early adulthood: a prospective-epidemiological study. J Pers. 1999;67:39–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le K, Donnellan MB, Conger R. Personality development at work: workplace conditions, personality changes, and the corresponsive principle. J Pers. 2013;82:44–56. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. The multiple, distinct ways that personality contributes to alcohol use disorder. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4:767–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Steinley D. Developmental trajectories of impulsivity and their association with alcohol use and related outcomes during emerging and young adulthood I. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Verges A, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Transactional models between personality and alcohol involvement: a further examination. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:778–783. doi: 10.1037/a0026912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW. Changes in sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity predicts increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M, Kleinjan M, Overbeek G, Vermulst AA, Lammers J, Engels RCME. Are there reciprocal relationships between substance use risk personality profiles and alcohol or tobacco use in early adolescence? Addict Behav. 2013;38:2851–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M, Kleinjan M, Vermulst AA, Overbeek G, Monshouwer K, Lammers J, Engels RCME. Do substance use risk personality dimensions predict the onset of substance use in early adolescence? A variable- and person-centered approach. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:1512–1525. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9775-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Association with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environment of adopt and non-adopt youth: evidence on range restriction from the sibling interaction and behavior study (SIBS) Behav Genet. 2007;37:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Harden KP. Differential changes in impulsivity and sensation seeking and the escalation of substance use from adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:223–239. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt T. Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:582–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Wing MJ, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Wood MD. Personality and substance use disorders: a prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto CJ, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J. Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: big five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100:330–348. doi: 10.1037/a0021717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Waller NG. Exploring personality through test construction: development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. In: Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment. Vol. 2. London: SAGE Publication Ltd; 2008. pp. 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya JG, Gray EK, Haig JR, Mroczek DK, Watson D. Differential stability and individual growth trajectories of big five and affective traits during young adulthood. J Pers. 2008;76:267–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Marmorstein NR, Crews FT, Bates ME, Mun E, Loeber R. Associations between heavy drinking and changes in impulse behavior among adolescent boys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernicke KA, Cantrell H, Finn PR, Lucas J. The association between earlier age of first drink, disinhibited personality, and externalizing psy-chopathology in young adults. Addict Behav. 2010;35:414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]