Abstract

Osteogenesis imperfecta type V (OI-V) has a wide clinical variability, with distinct clinical/radiological features, such as calcification of the interosseous membrane (CIM) between the radius-ulna and/or tibia-fibula, hyperplastic callus (HPC) formation, dislocation of the radial head (DRH), and absence of dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI). Recently, a single heterozygous mutation (c.-14C>T) in the 5′UTR of the IFITM5 gene was identified to be causative for OI-V. Here, we describe 7 individuals from 5 unrelated families that carry the c.-14C>T IFITM5 mutation. The clinical findings in these cases are: absence of DI in all patients, presence of blue sclera in 2 cases, and 4 patients with DRH. Radiographic findings revealed HPC in 3 cases. All patients presented CIM between the radius and ulna, while 4 patients presented additional CIM between the tibia and fibula. Spinal fractures by vertebral compression were observed in all individuals. The proportion of cases identified with this mutation represents 4% of OI cases at our institution. The clinical identification of OI-V is crucial, as this mutation has an autosomal dominant inheritance with variable expressivity.

Key Words: Autosomal dominant inheritance, IFITM5, Osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a collective term for a set of connective tissue syndromes with heterogeneous etiology characterized by bone fragility, susceptibility to bone deformity, and the occurrence of fractures. OI is considered to be the most common skeletal dysplasia, with an estimated prevalence of around 6-7 per 100,000 births [Van Dijk et al., 2010; Van Dijk and Sillence, 2014].

Several molecular studies identified 17 genes, primarily involved in the biosynthesis of collagen, in which mutations can be causative for OI. However, the International Nomenclature Group for Constitutional Disorders ICHG of the Skeleton (INCDS) standardized the classification of OI by keeping the 4 types that were originally described by Sillence et al. [1979], and adding OI type V [Warman et al., 2011; Van Dijk and Sillence, 2014]. This current classification is based on the severity and clinical features of the disorder and is comprised of: mild (OI type I/OI-I), lethal (OI type II/OI-II), severely deforming (OI type III/OI-III), moderately deforming (OI type IV/OI-IV), and OI type V (OI-V).

OI-V (OMIM 610967) is a nonlethal form that presents a wide variability in its severity, distinct clinical characteristics, and an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern [Shapiro et al., 2013; Van Dijk and Sillence, 2014]. It was originally described in 1908 by Battle and Shattock as a specific type of OI in which calcification of the interosseous membrane (CIM) was observed in the forearms and legs. Further studies complement this description, adding other specifically clinical characteristics and suggesting that OI-V corresponds to 4-5% of all OI cases [Bauze et al., 1975; Glorieux et al., 2000; Van Dijk and Sillence, 2014].

Among the main features of OI-V, the formation of hyperplastic callus (HPC) after corrective surgery or fracture is often observed as well as the absence of dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI), progressive calcification (ossification) of the interosseous membrane (CIM) between radius-ulna and/or tibia-fibula, and dislocation of the radial head (DRH) that causes restriction in the pronation and supination of the forearm [Glorieux et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013].

In 2012, a single heterozygous mutation (c.-14C>T) in the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) of the IFITM5 gene encoding the interferon-induced transmembrane protein 5 was described to be causative for OI-V. This mutation adds 5 amino acids (Met-Ala-Leu-Glu-Pro) to the N-terminus of the protein. The product of the IFITM5 gene, located on chromosome region 11p15.5, is also known as bone-restricted IFITM-like protein, a protein with 132 amino acids that has 2 transmembrane domains and an intracellular loop [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012]. After this specific mutation was published, several studies reported cases of individuals with the same mutation and phenotype of OI-V [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012; Takagi et al., 2013; Balasubramanian et al., 2013; Grover et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al., 2014; Lazarus et al., 2014; Reich et al., 2015].

The aims of this study were to describe the clinical and radiological characteristics of OI-V, in addition to analyzing the c.-14C>T mutation in the IFITM5 gene and to compare our findings to cases already reported in the literature.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Of the 125 registered OI patients at the Reference Center of Osteogenesis Imperfecta at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (CROI-HCPA), 35 patients, both male and female, were included in this study. The cases were selected according to clinical and radiological features of OI-V, and ranged in age from 1 to 52 years. Two additional cases, with suggestive features, were referred from other centers (Recife, PE, and Rio de Janeiro, RJ) for molecular analysis.

Data from medical records and radiographic images were reviewed for confirmation of clinical data and for the presence of CIM between the radius-ulna and/or the tibia-fibula as well as DRH, HPC formation or remodeling, scoliosis, and spine fractures. Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured by DEXA (Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry/HOLOGICQDR-4500, version 8.26:3, Waltham, Mass., USA). A Z- or T-score for bone mass that was 2 SD or more below the mean for the age of the patient was defined as low BMD, following the official consensus of the Brazilian Society for Clinical Densitometry in 2006 [Zerbini et al., 2007].

Clinical Reports

All cases reported here had a confirmed diagnosed of the c.-14C>T mutation in the IFITM5 gene.

Case 1

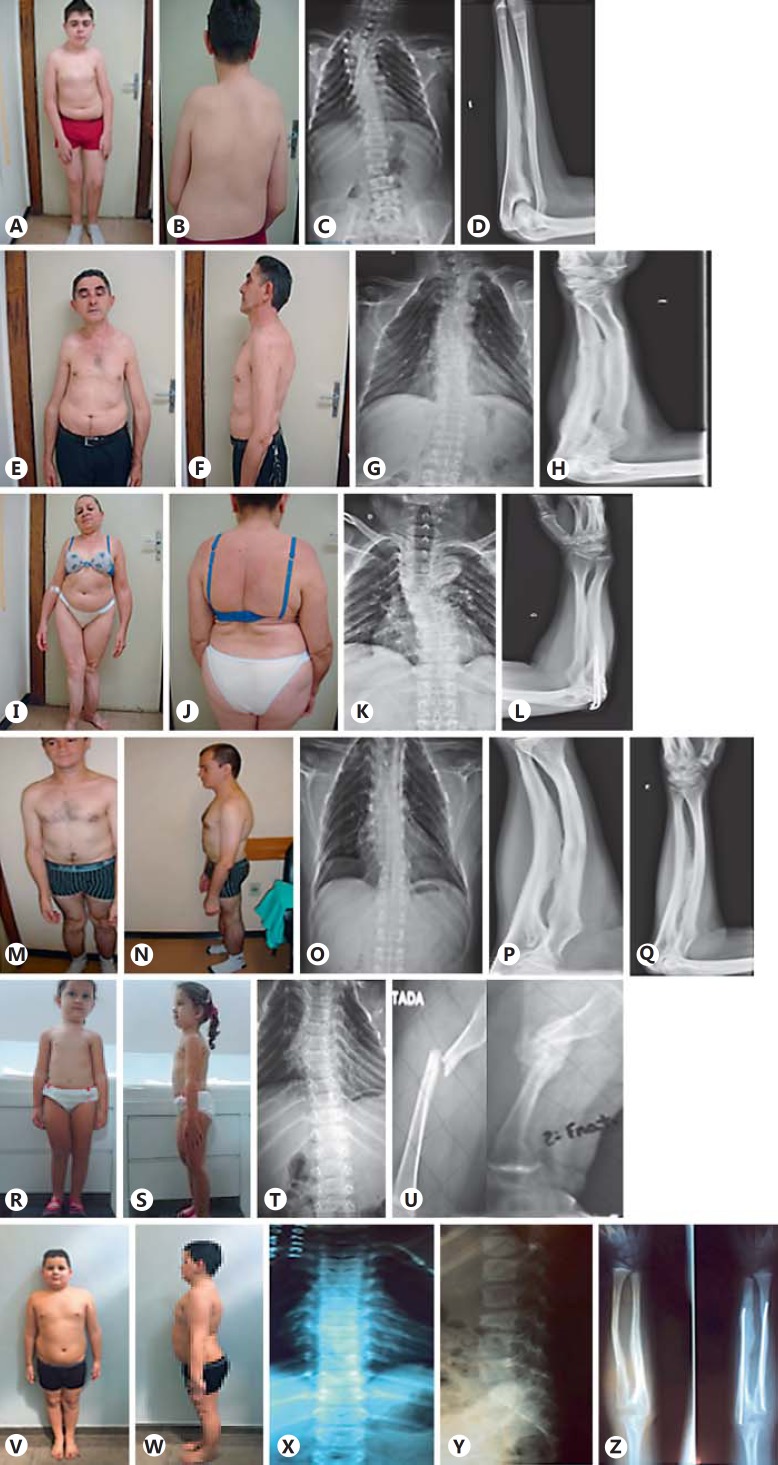

The boy, 14 years old, is the third child of nonconsanguineous parents (fig. 1A, B). His father (case 2), aunt (case 3), and paternal grandfather had a history of multiple fractures. He was born by cesarean section with a birth weight of 2,430 g (2nd percentile) and a length of 46 cm (2nd percentile). A large fontanel was observed at birth. At 3 months, upon admission to the hospital for pneumonia, rib fractures were observed on X-ray. This patient had ∼27 fractures distributed over the arms, forearms, femurs, legs, ribs, and spine (fig. 1C). The latest identified was a spinal fracture, at 13 years of age, and was treated with a brace. The patient has an intramedullary rod in the right femur and is able to walk independently. A physical examination at 14 years of age showed a height of 158.5 cm (25-50th percentile) and a weight of 62.8 kg (75-90th percentile), with a OFC of 56.5 cm (50-98th percentile). Ligamentous laxity, restriction of pronation and supination of the forearms, deformities of long bones, severe scoliosis and pronated feet, absence of blue sclera, and DI were observed. This patient has been on intravenous pamidronate treatment since 2 years of age. Radiographic examination showed deformities of the long bones and ribs, CIM between the forearm (fig. 1D) and leg bones, and proximal dislocation of the radius head. At 3 years of age, BMD was 0.450 g (Z-score: −5.8 SD) in the spine and 0.509 g/cm2 (Z-score: −3.5 SD) for the whole body. At age of 13, the spinal BMD score was 0.955 g/cm2 (Z-score: 0.7 SD) and the whole body score was 0.981 g/cm2 (Z-score: 1.1 SD).

Fig. 1.

Patients and radiological findings. Case 1: A, B Patient images. C Throracolumbar scoliosis and irregular rib positions. D CIM. Case 2: E, F Patient images. G Thoracic scoliosis and irregular rib positions. H CIM. Case 3: I, J Patient images. K Severe cervicothoracolumbar scoliosis. L CIM. Case 5: M, N Patient images. O Thoracic scoliosis and rib deformities. P, Q CIM and DRH. Case 6: R, S Patient images. T Reduction of height of vertebral bodies, scoliosis and rib deformities. U HPC after femur fracture. Case 7: V, W Patient images. X, Y Reduction of height of vertebral body and rib irregularities. Z CIM.

Case 2

This male patient, 51 years old, is the father of case 1 (fig. 1E, F). His first fracture, in the humerus, occurred at 12 months of age, and he reports a history of 16 fractures distributed among the clavicle, patella, forearms, spine, feet, and hands. He has a constant complaint of back pain. His height was 164.5 cm (5th percentile) with a weight of 59.3 kg (10-25th percentile). Upon physical examination, a slightly blue sclera, limitation of pronation and supination of the forearms, no DI, and an independent gait were observed. The patient had worn an orthopedic brace for several years due to scoliosis and had received treatment with oral bisphosphonate. Radiographic examination revealed deformity of the long bones and ribs, scoliosis associated with fracture by compression in several thoracolumbar vertebrae (fig. 1G), DRH and CIM of the bones of the forearms (fig. 1H) and legs. A protuberant remodeled callus on the humerus suggestive of HPC was noted. Bone mineral densitometry showed 0.747 g/cm2 (T-score: −3.9 SD) in the spine and 0.847 g/cm2 (T-score:-1.8 SD) for the total femur.

Case 3

This 52-year-old female is the paternal aunt of case 1 and a sister to case 2 (fig. 1I, J). Her first fracture occurred at 13 years of age in the right tibia and fibula. She had ∼7 fractures distributed among the femur, tibia, fibula, elbows, toes, and hands. On physical examination, her height was 127.5 cm (<2nd percentile) and weight 47.7 kg (10th percentile). Bone deformities, particularly an anterior bowing of the tibias, limitation of pronation and supination of the forearms, and lack of blue sclera and DI were observed. She was able to walk with support of an auxiliary device. She has received treatment with oral bisphosphonate. At 51, she was diagnosed with a melanoma in the neck and underwent surgical intervention. She presented with joint degeneration in the right hip and was determined to be a candidate for hip replacement surgery. The bone densitometry showed osteoporosis of the spine (BMD: 0.654 g/cm2; T-score: −4.4 SD) and distal radius (0.268 g/cm2; T-score: −4.3 SD), with proximal femoral osteopenia (BMD: 0.722 g/cm2; T-score: −1.8 SD). X-ray showed deformities of the long bones and ribs, with scoliosis associated with vertebral fractures (fig. 1K), DRH and CIM between the bones of the forearms (fig. 1L).

Case 4

This patient is an 18-year-old female with no available family history; she was adopted at 12 months of age. Her birth weight was 2,900 g (10-25th percentile) with a length of 47 cm (3-5th percentile) and an OFC of 34 cm (25th percentile). A large fontanel and fracture of the left clavicle was noted. She had multiple fractures distributed between the spine, pelvis, upper, and lower limbs. The latest fracture was in the pelvis at age 17. Her height was 137 cm (<3rd percentile) and her weight was 36 kg (<3rd percentile). On clinical examination, blue sclera, bone deformities in the arms and legs, and a lack of DI were noted. She had intramedullary rodding in the right femur and left tibia. Up until 14 years of age, she was able to walk at home with aid; however, upon the occurrence of a new fracture, she became wheelchair dependent. She was treated with cyclic pamidronate between 7 and 12 years of age and had received 14 cycles before pamidronate was replaced by oral bisphosphonate (alendronate). X-rays showed bone deformities in the long bones of the forearms and legs, vertebral fractures, and CIM between the bones of the forearms and legs.

Case 5

This patient is a 30-year-old male and the second son of nonconsanguineous parents with no family history of OI (fig. 1M, N). His first fracture occurred between 3 and 6 months of age, and he was diagnosed with OI at the age of 5 years. He presented with ∼30 fractures distributed among the spine, humerus, radius, ulna, femur, tibia, ribs, hands, and skull. The latest fracture occurred in the 5th metacarpal when he was 29 years old. Clinical evaluation showed a height of 146.6 cm (<3rd percentile), a weight of 49 kg (<3rd percentile), laxity of ligaments, lack of blue sclera and DI, bone deformities such as bowing of the long bones in the upper and lower limbs, limitation of pronation and supination of the forearms, and deformities of the feet. He was currently taking oral bisphosphonate (alendronate) and has an independent gait. X-rays at the age of 29 showed levoconvex scoliosis with a Cobb's angle of 10°, severe reduction of vertebrae height due to vertebral body compression fractures (fig. 1O), and deformities of the ribs and long bones, with DRH on the forearms, CIM between radius and ulna (fig. 1P, Q), and HPC in the left humerus. BMD measurements showed 0.741 g/cm2 (T-score: −1.9 SD) in the femoral neck and 0.610 g/cm2 (T-score: −4.4 SD) in the spine.

Case 6

This 3-year-old girl was referred from Recife, PE, Brazil (fig. 1R, S). She is the first daughter of nonconsanguineous parents with no family history of OI. She was diagnosed with OI after the first year of life, having had 4 fractures that were distributed among the femur, humerus and spine. Upon physical examination, her height was 95.5 cm (75-90th percentile), her weight was 15.2 kg (75-90th percentile) and she presented with joint laxity, scoliosis, the absence of blue sclera, and DI. She was treated with cyclic pamidronate and has an independent gait. Radiographic examination revealed the presence of wormian bones in the skull, dextroconvex scoliosis, and deformity of the ribs (fig. 1T) as well as microfractures that reduced the height of several vertebral bodies with greater involvement between the thoracic and lumbar spine transition at the age of 2. A femur fracture under consolidation with HPC formation in the site of the fracture was also observed (fig. 1U) and CIM between the forearms bones. Lower limb X-rays showed a difference of 1.01 cm between the limbs, with the right limb being shorter.

ase 7

This 10-year-old boy was referred from Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil (fig. 1V, W). He is the second son of nonconsanguineous parents; his mother and brother have OI. His first fracture occurred at 2 years of age, with a total of 6 fractures distributed between the right and left radius and the right tibia. Following the first fracture, surgical intervention for the placement of intramedullary rodding was performed. His height was 141 cm (75-90th percentile) and weight 53 kg (>97th percentile). He was observed to have dorsal kyphosis, bone deformities of the forearms, and the absence of blue sclera and DI. He had an independent gait and had been on oral bisphosphonate for 1 year. X-rays revealed a fracture by compression at the 3rd lumbar vertebra (fig. 1X, Y) at 10 years, bone deformities in the radius, ulna and ribs, and CIM between both forearm and leg bones (fig. 1Z). BMD for the right hip and lumbar spine was 0.888 g/cm2 (Z-score: 1.7 SD) and 0.734 g/cm2 (Z-score: 0.5 SD), respectively.

Molecular Analyses

To conduct molecular analyses, 5 ml of peripheral blood were collected from each patient, and DNA was extracted according to standard methods. A 370-bp fragment, encompassing the 5′UTR of the IFITM5 gene, was amplified by PCR using a Veriti® 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif., USA). The primers used were IFITM5_F 5′ CCGCAGGCTGTAATTTGTG 3′ (forward) and IFITM5_R 5′ CCACCTTGATGGAGTAGTGG 3′ (reverse), in a final concentration of 0.2 μM each. PCR reactions were designed to a final volume of 25 μl, with 200 μM dNTPs, 1.5 mM Mg2+, and 1 U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Foster City, Calif., USA). Amplification products were purified by the Exo/SAP protocol and subjected to Sanger sequencing using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 10 µl. Labeling reactions were performed in a thermocycler with an initial denaturing step of 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and final extension step of 72°C for 5 min. Samples were submitted to capillary electrophoresis in an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The resulting electropherograms were viewed and analyzed using Chromas Lite software (Technelysium Pty, Tewantin, Qld., Australia).

Results

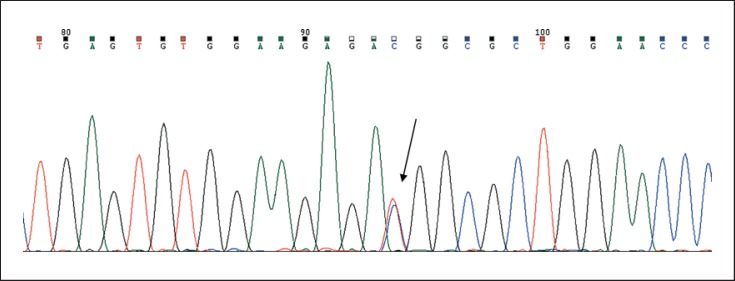

Among the 35 individuals analyzed at CROI-HCPA, 5 cases were found to harbor the OI-V-associated c.-14C>T mutation in the IFITM5 gene. Additionally, 2 individuals referred from others centers were also positive for this mutation (fig. 2). Clinical data and radiographic findings are described in table 1. Of the 7 patients harboring the IFITM5 mutation, 4 were males and 3 females. Two cases were isolated, 4 had a positive family history of OI, and in 1 case the family history was unavailable. Absence of DI was observed in all patients; 4 patients had DRH, and 1 had a bilateral displacement. Figure 1 shows patient and radiological images. HPC was confirmed via X-ray in 3 cases and was suspected in one additional case. All patients had CIM between the radius-ulna, and 4 individuals had additional CIM between the tibia-fibula. Spine fractures, by vertebral compression, as well as a characteristic pyramidal shape of the chest and ribs, were observed in all subjects.

Fig. 2.

Sanger sequencing showing c.-14C>T mutation in the IFITM5 gene.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiographic characteristics of patients with OI-V (mutation c.-14C>T in the IFITM5 gene) and a comparison to the literature

| Cases |

Literaturea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, male | 2, male | 3, female | 4, female | 5, male | 6, female | 7, male | ||

| Family history | + | + | + | unknown | – | – | + | |

| Age at clinical examination, years | 14 | 51 | 52 | 18 | 30 | 3 | 10 | |

| Mobility | independent | independent | independent with support | wheelchair dependent | independent | independent | independent | |

| Height, cm | 158.5 | 164.5 | 127.5 | 137 | 146.6 | 95.5 | 141 | |

| Short stature | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | 38% |

| DI | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0% |

| BS | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | 9.5% |

| BMD, SD | spine-Z: 0.7 total body-Z: 1.1 | spine-T: −3.9 total femur-T: −1.8 | spine-T: −4.4 femur-T: −1.8 distal radius-T: −4.3 | spine-Z: −2.0 total body-Z: −1.6 | spine-T: −4.4 femur-T: −1.9 | spine-Z: 0.5 right hip-Z: 1.7 | ||

| Age and first fracture | at birth, rib | 12 months, humerus | 13 years, tibia and fibula | at birth, clavicula | 3–6 months, unknown | 20 months, femur | 2 years, radius and tibia | |

| Fractures, n | 27 | 16 | 7 | 33 | 30 | 4 | 6 | |

| BP | pamidronate | alendronate | alendronate | alendronate or pamidronate | alendronate | pamidronate | alendronate | 28.5% |

| HPC | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | 64% |

| CIM | + R/U, T/F | + R/U, T/F | + R/U | + R/U, T/F | + R/U | + R/U | + R/U, T/F | 88% |

| DRH | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | 78% |

| Scoliosis | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | 51% |

| Spine fracture by compression | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 42% |

| c.–14C>T mutation in IFITM5 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 126 subjects identified |

BP = Bisphosphonate; BS = blue sclera; R/U = radius and ulna; T/F = tibia and fibula; + = yes/positive result; – = no/negative result.

Twelve studies were included describing 126 individuals analyzed with the phenotype of OI-V and c.–14C>T mutation [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012; Balasubramanian et al., 2013; Grover et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Takagi et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al., 2014; Lazarus et al., 2014; Reich et al., 2015].

Discussion

In this study, we describe 7 unreported cases with the diagnosis of OI-V carrying the c.-14C>T mutation in the 5′UTR of the IFITM5 gene. This number corresponds to ∼4% of all OI cases at CROI-HCPA. Although these individuals have been identified to harbor the same mutation, the severity of the disease phenotype varies significantly. IFITM5 is a member of the interferon-induced transmembrane gene family, and this specific heterozygous mutation has been described to be causative for OI-V [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012]. The specific function of IFITM5 in bone development has not been well elucidated, but it is known to increase ectopic ossification and appears to be involved in the process of bone formation and osteoblast maturation [Reich et al., 2015]. The expression of wild IFITM5 has been shown to be limited to osteoblasts, and the expression of mutant IFITM5 is restricted to bone and cartilage [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012].

In vitro studies using mouse models have shown that the product of the IFITM5 gene plays a role in mineralization during bone growth in the early mineralization stage and in prenatal development [Moffatt et al., 2008; Hanagata et al., 2011]. A neomorphic effect of Ifitm5 mutation in the bone was observed in a recent study of mutant Iftim5 transgenic mice. The OI-V mutation (c.-14C>T) in Ifitm5 led to low bone mass, abnormal osteoblast differentiation, delayed skeletal development, and skeletal defects in these mice that included abnormal rib cage formation, long bone deformities, and fractures [Lietman et al., 2015].

The clinical presentation of OI-V associated to this mutation ranges from moderate to severe, and the literature has described specific clinical features of this type of OI. The main features are absence of DI, HPC, CIM, and DRH with frequencies around 64, 88, and 78%, respectively [Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012; Takagi et al., 2013; Balasubramanian et al., 2013; Grover et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al., 2014; Lazarus et al., 2014; Reich et al., 2015]. However, some studies including patients with clinical diagnosis of OI-V were published before this specific related mutation was found in 2012 [Glorieux et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Zeitlin et al., 2006].

In general, these patients do not have discoloration of the sclera or wormian bones in the skull, but do present with frequent fractures that lead to bone deformity, short stature, scoliosis, vertebral compression fractures, and joint hypermobility [Glorieux et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013].

In the current study, we observed only 2 patients with blue sclera. Consistent with our findings, Shapiro et al. [2013] reported 2 out of 17 patients with blue sclera, while only 2 other studies have cited 2 or more cases of patients with OI-V presenting with blue sclera [Grover et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al, 2014]. Regarding DI, we observed no impairments of dentin, which is consistent with several previous studies [Glorieux et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Zeitlin et al., 2006; Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012; Takagi et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al., 2014].

Short stature seems to be frequent among individuals with OI-V; 9 previous studies in which 85 individuals were described included 57 who presented with reduced stature [Glorieux et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Cho et al., 2012; Semler et al., 2012; Takagi et al., 2013; Balasubramanian et al., 2013; Hoyer-Kuhn et al., 2014; Rauch et al., 2013; Guillén-Navarro et al., 2014]. Only one of the individuals in our study was dependent on a wheelchair for mobility, although this person had been able to walk independently through adolescence. Cho et al. [2012] observed, among a cohort of 19 individuals, only 8 with fully independent walking. In another study, among 16 subjects observed with this criterion, 2 presented gait with support, and 4 patients were dependent on a wheelchair for mobility [Shapiro et al., 2013].

Bone fragility is the main feature of OI, and OI-V with the IFITM5 mutation appears to be no exception. A wide variability in the age of the first fracture, as well as the total number of fractures, was seen in the patients in the current study. This is consistent with previous reports that included patients with the same mutation, which find that the number of fractures is indeed highly variable; frequencies from 0 to 30 fractures have been reported [Cho et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Lazarus et al., 2014; Reich et al., 2015]. Zhang et al. [2013] described 4 Chinese families with individuals aged between 4 and 29 years with the occurrence of 3-11 fractures. In our sample, 2 subjects had fractures at birth, and one had the first fracture at 13 years of age. This criterion also was analyzed in 2 previous studies; in the first study, 42% of patients had fractures at birth [Rauch et al., 2013]. In the second, 3 subjects experienced the first fracture before birth, still in utero [Reich et al., 2015].

Furthermore, we observed that all the patients had vertebral fractures by compression, and only one individual did not have scoliosis. Two previous studies have described the occurrence of vertebral fractures in 87 and 100% of the cases [Lee et al., 2006; Shapiro et al., 2013], and scoliosis was observed at a frequency between 50 and 76% in 5 studies involving 98 individuals [Glorieux et al., 2000; Zeitlin et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013]. Also relevant, the investigators in all these cases observed the patients to exhibit a pyramidal shape of the chest and ribs with an unusual form and downward slanting [Kim et al., 2013]. The cause for this alteration of the rib position and shape is unknown, and this feature has not been described in other types of OI.

Changes in bone mineralization arising from an increase in ectopic ossification lead to a characteristic osteoporotic phenotype in all of these patients; however, they also present with exuberant bone formation, reflected by the HPC development, which is unique to this type of OI [Cheung et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013]. Histomorphometrically, there are also differences in OI-V, as these individuals exhibit a lower rate of bone remodeling activation due to lower bone formation and resorption parameters when compared to patients with OI-IV [Glorieux et al., 2000].

In addition, we observed the presence of HPC only in the long bones and after fractures had occurred. HPC is a soft tissue anomaly characterized by exuberant bone formation with extensive expansion beyond the site of fracture, which occurs following fracture or surgery, and whose etiology remains unclear [Cheung et al., 2007; Shapiro et al., 2013]. In general, during the formation of HPC, biochemical changes are observed that include an increase of serum alkaline phosphatase and urinary excretion of N-telopeptide [Glorieux et al., 2000]. According to Cheung et al. [2007], fractures are the most common complication resulting from HPC and may lead to bone deformation. Additionally, a differential diagnosis with osteosarcoma needs to be carefully investigated.

All individuals presented CIM in the upper limbs, and 58% had DRH. CIM has often been observed in subjects with OI-V; similar to our findings, a high frequency of CIM around 80 and 100% have been reported in different studies [Cho et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Lazarus et al., 2014]. However, a greater variability in the presentation of DRH has been reported in the literature. In general, the frequency of DRH described varies between 60 and 100% in the OI-V individuals; however, Semler et al. [2012] did not observe DRH in either of 2 individuals analyzed [Cho et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013; Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013; Lazarus et al., 2014].

Clinical intrafamilial variability had been reported in OI-V [Rauch et al., 2013; Shapiro et al., 2013], as was observed in this study. Bone deformities and lack of DI were common clinical features between the described family members (cases 1, 2 and 3); however, case 3 had a severe short stature and ‘saber shin’ deformity of the tibias. Also, case 1 rapidly developed a severe scoliosis (Cobb's angle >45°) when he started puberty, different from other family members that had mild spine deformity. The mother and brother of case 7 also had OI clinical diagnosis; however, both experienced only a few fractures throughout life (2 and 9 fractures, respectively). Both siblings had CIM between radius-ulna, and only the brother had HPC.

In our study, all patients had received treatment with oral or intravenous bisphosphonate; however, the efficacy of this drug was not evaluated since this was not the goal of this study.

Among individuals with negative result to IFITM5 mutation analysis, the severity of OI ranged from mild to severe (OI-I: 3, OI-III: 10, OI-IV: 17). White and blue sclerae were observed, and 21 individuals had DI. In addition, the majority of these patients experienced multiple fractures since childhood and had some degree of joint mobility restriction at the forearm – deformity secondary to fracture or surgery intervention at the site. Some of these patients had scoliosis or vertebrae fracture, but none had the alteration of thorax shape similar to the individuals with positive mutation result. One patient had a very severe scoliosis going through surgery when she was only 11 years old, and a second patient had the first vertebral fracture at the early age of 6 years.

The present study has limitations; some of the data were retrospective, based on data recorded in medical charts. We did not have radiographic confirmation for all fractures; therefore, we also used clinical histories according to family information. Bisphosphonate treatment and bone densitometry results were not evaluated because of the many variables involved that were not within the scope of this study.

OI-V corresponds to 4% of OI cases in Brazil, which is similar to the overall incidence in other populations. All subjects described in this report had the c.-14C>T IFITM5 mutation and an OI-V phenotype similar to other populations previously described. CIM seems to be the most frequent feature present in this type of OI as well as the absence of DI. The confirmation of the specific IFITM5 mutation for diagnostic purposes is essential, as this will contribute to more specific genetic counseling and clinical management in these families.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (No. 13-0187), and all patients or guardians signed an informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their participation in this study. The study was supported by the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos/Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. E.B. was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) Proc. Número 3770/14-1.

References

- 1.Balasubramanian M, Parker MJ, Dalton A, Giunta C, Lindert U, et al. Genotype-phenotype study in type V osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Dysmorphol. 2013;22:93–101. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32836032f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battle WH, Shattock SG. A remarkable case of diffuse cancellous osteoma of the femur following a fracture, in which similar growths afterwards developed in connection with other bones. Proc R Soc Med. 1908;1:83–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauze RV, Smith R, Francis MJO. A new look at osteogenesis imperfecta. A clinical, radiological and biochemical study of forty-two patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung MS, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Natural history of hyperplastic callus formation in osteogenesis imperfecta type V. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1181–1186. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho TJ, Lee KE, Lee SK, Song SJ, Kim KJ, et al. A single recurrent mutation in the 5′-UTR of IFITM5 causes osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glorieux FH, Rauch F, Plotkin H, Ward L, Travers R, et al. Type V osteogenesis imperfecta: a new form of brittle bone disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1650–1658. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.9.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grover M, Campeau PM, Lietman CD, Lu JT, Gibbs RA, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta without features of type V caused by a mutation in the IFITM5 gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2333–2337. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillén-Navarro E, Ballesta-Martínez MJ, Valencia M, Bueno AM, Martinez-Glez V, et al. Two mutations in IFITM5 causing distinct forms of osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1136–1142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanagata N, Li X, Morita H, Takemura T, Li J, Minowa T. Characterization of the osteoblast-specific transmembrane protein IFITM5 and analysis of IFITM5-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29:279–290. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoyer-Kuhn H, Semler O, Garbes L, Zimmermann K, Becker J, et al. A nonclassical IFITM5 mutation located in the coding region causes severe osteogenesis imperfecta with prenatal onset. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1387–1391. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim OH, Jin DK, Kosaki K, Kim JW, Cho SY, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta type V: clinical and radiographic manifestations in mutation confirmed patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:1972–1979. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus S, McInerney-Leo AM, McKenzie FA, Baynam G, Broley S, et al. The IFITM5 mutation c.-14C>T results in an elongated transcript expressed in human bone; and causes varying phenotypic severity of osteogenesis imperfecta type V. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DY, Cho TJ, Choi IH, Chung CY, Yoo WJ, et al. Clinical and radiological manifestations of osteogenesis imperfecta type V. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:709–714. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lietman CD, Marom R, Munivez E, Bertin TK, Jiang MM, et al. A transgenic mouse model of OI type V supports a neomorphic mechanism of the IFITM5 mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffatt P, Gaumond MH, Salois P, Sellin K, Bessette MC, et al. Bril: a novel bone-specific modulator of mineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1497–1508. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauch F, Moffatt P, Cheung M, Roughley P, Lalic L, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta type V: marked phenotypic variability despite the presence of the IFITM5 c.-14C>T mutation in all patients. J Med Genet. 2013;50:21–24. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich A, Bae AS, Barnes AM, Cabral WA, Hinek A, et al. Type V OI primary osteoblasts display increased mineralization despite decreased COL1A1 expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E325–E332. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semler O, Garbes L, Keupp K, Swan D, Zimmermann K, et al. A mutation in the 5′-UTR of IFITM5 creates an in-frame start codon and causes autosomal-dominant osteogenesis imperfecta type V with hyperplastic callus. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro JR, Lietman C, Grover M, Lu JT, Nagamani SC, et al. Phenotypic variability of osteogenesis imperfecta type V caused by an IFITM5 mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1519–1522. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16:101–116. doi: 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi M, Sato S, Hara K, Tani C, Miyazaki O, et al. A recurrent mutation in the 5′-UTR of IFITM5 causes osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:1980–1982. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dijk FS, Sillence DO. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical diagnosis, nomenclature and severity assessment. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1470–1481. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Dijk FS, Pals G, van Rijn RR, Nikkels PG, Cobben JM. Classification of osteogenesis imperfecta revisited. Eur J Med Genet. 2010;53:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warman ML, Cormier-Daire V, Hall C, Krakow D, Lachman R, et al. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2010 revision. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:943–968. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeitlin L, Rauch F, Travers R, Munns C, Glorieux FH. The effect of cyclical intravenous pamidronate in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Bone. 2006;38:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zerbini CA, Pippa MG, Eis SR, Lazaretti-Castro M, Mota Neto H, et al. Clinical densitometry – official positions 2006. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2007;47:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, Li M, He JW, Fu WZ, Zhang CQ, Zhang ZL. Phenotype and genotype analysis of Chinese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta type V. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]