Abstract

Introduction:

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is rare in North America; however, the morbidity can be devastating. This analysis represents the first reported penile cancer experience at a tertiary care centre in Canada.

Methods:

We carried out a retrospective review of all patients who received care at our centre for penile SCC from 2005 until the present time. Epidemiological and clinical data were collected for all patients. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier methods with log-rank test and Cox regression for univariate and multivariate analysis, respectively.

Results:

We identified 42 patients who were treated at our centre for penile SCC. Of these, 29% underwent excisional biopsy, 38% had partial penectomy, and 33% had total penectomy. Five patients with high-risk tumours underwent modified inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND), while 7 patients had radical ILND for clinically palpable disease. Overall, the median cancer specific survival (CSS) was undefined, with a 60% survival at 102 months. However CSS was significantly correlated to pT stage, pN stage, and tumour grade. The median follow-up was 25 months (interquartile range: 11–48).

Conclusion:

These findings confirm the poor CSS of patients with positive lymph nodes in penile SCC. Patients with pN0 after ILND had a durable CSS. Risk factors for penile SCC were confirmed as elevated body mass index, positive smoking history, and lack of circumcision. This first epidemiologic report on penile SCC from a Canadian tertiary care centre should be expanded to other national centres.

Introduction

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is rare in North America; however the morbidity can be devastating.1 The incidence is highest in developing countries, likely linked to a preponderance of risk factors.2 Identified risk factors for this disease include tobacco use, chronic inflammation, balanitis, lichen sclerosus, phimosis, poor hygiene, absence of childhood circumcision, and sexually transmitted diseases, especially human papillomavirus (HPV), which is related to 45% to 80% of penile cancers.2–10 Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Association of Urology (EAU) on managing penile SCC point to the extent of regional lymph node metastasis as the most important prognostic factor for survival.11,12 Consequently, the management of nodal disease is critical.

Clinically node negative patients harbour a risk of micrometastatic lymph node involvement of up to 25%.13 Thus lesions with high-risk features should be managed with modified inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND) even if patients are clinically node negative.14–16 Early lymph node dissection has demonstrated a survival benefit rather than waiting for surgery at time of nodal recurrence.17–19 Low-risk lesions, defined as stage T1a or less and grade 1, are able to be managed with surveillance only following treatment of the primary lesion.

Adjuvant chemotherapy has demonstrated benefit in the setting of advanced nodal disease (pN2 or pN3), although the evidence for radiotherapy is less clear.20,21 In the case of bulky nodal disease not suitable for resection, the EAU recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on several small studies using a variety of chemotherapy regimens, with responders able to undergo nodal dissection.20,22,23

The above recommendations and guidelines are based on limited data due to the low incidence of penile SCC. Further, most reports come from developing countries where the disease is more common. To our knowledge, this analysis represents the first reported penile cancer experience of a tertiary care centre in Canada. We hope to not only inform on current treatment regimens, but also to draw attention to the complete lack of institutional data from many Canadian centres.

Methods

We carried out a retrospective review of all patients who received care at our centre for penile SCC from 2005 to 2015. We collected epidemiological and clinical data, including age, smoking history, circumcision status, body mass index (BMI), TNM staging, tumour pathology, treatment history and oncologic outcome, for all patients. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method for univariate analysis and Cox regression for multivariate analysis.

Results

We identified 42 patients who were treated at our centre for penile SCC between 2005 and 2015. The median age was 66 years old (interquartile range [IQR]: 56–78), median BMI was 30.7 (IQR: 27–36); half of the patients had a history of smoking and 69% were uncircumcised prior to adulthood (Table 1). In regards to primary treatment, 29% underwent excisional biopsy, 38% had partial penectomy, and 33% had total penectomy. The median follow-up was 25 months (IQR: 11–48).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Variable | Mean (IQR) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 66 (56–78) | |

| BMI | 30.7 (27–36) | |

| Neonatal circumcision | ||

| Yes | 1 (2.4) | |

| No | 29 (69.0) | |

| Not documented | 12 (28.6) | |

| Smoker | ||

| Yes | 21(50.0) | |

| No | 11 (26.2) | |

| Not documented | 10 (23.8) | |

| Primary surgery | ||

| Excisional biopsy | 12 (28.6) | |

| Partial penectomy | 16 (38.1) | |

| Total penectomy | 14 (33.3) | |

| T Stage | ||

| Carcinoma in situ | 7 (16.7) | |

| T1 | 10 (23.8) | |

| T2 | 19 (45.2) | |

| T3 | 6 (14.3) | |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 27 (64.3) | |

| N1 | 1 (2.4) | |

| N2 | 2 (4.8) | |

| N3 | 12 (28.6) | |

| Clinical nodal status at presentation | ||

| Clinically node negative | 32 (76.2) | |

| Clinically node positive | 10 (23.8) | |

| Grade | ||

| G1 | 17 (40.5) | |

| G2 | 20 (47.6) | |

| G3 | 5 (11.9) |

IQR: interquartile range; BMI: body mass index.

Patients with clinically negative lymph nodes

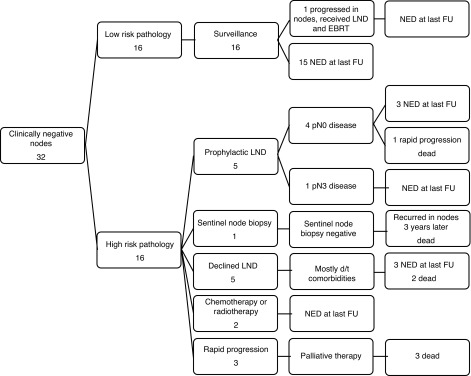

Of the 32 patients with clinically negative lymph nodes (cN0), 16 patients with low-risk pathology underwent surveillance only. Of these, only 1 had progression for which he underwent bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection (BILND) and pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) followed by external beam radiotherapy. At last follow-up, this patient had no evidence of disease at 85 months after his original surgery and 65 months after completing radiotherapy.

The remaining 16 patients with cN0 disease were deemed high risk based on the pathology of their primary tumours (Fig. 1). Of these, 5 underwent prophylactic, modified BILND and of these, 4 were pN0 and 1 had pN3 disease. Of these 4 patients with pN0 disease, 1 underwent a rapid progression of disease and he died following salvage surgery and palliative chemotherapy. The remaining 4 patients had no evidence of disease at their most recent follow-up. One patient underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was negative for malignancy. Unfortunately this patient had disease recurrence 3 years later and died after salvage LND and palliative chemotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Clinically node negative outcomes. LND: lymph node dissection; d/t: due to; EBRT: external beam radiotherapy; NED: no evidence of disease; FU: follow-up.

Of these 16 patients, 10 did not undergo surgical intervention for nodal disease. One received concurrent chemoradiotherapy and was alive with no evidence of disease at 39 months following his primary surgery. One patient received external beam radiotherapy and had no evidence of disease at the most recent follow-up 30 months following his primary surgery. Of these 10 patients, 5 declined or were not offered prophylactic BILND due to comorbidities. Of these, 3 patients had no evidence of disease at most recent follow-up and 2 experienced recurrence and died after palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy, respectively. Finally, 3 patients progressed rapidly and died before intervention could be performed.

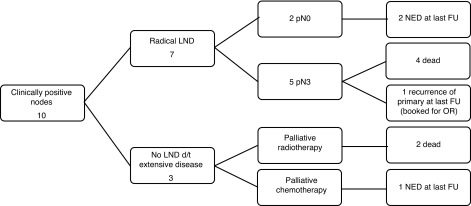

Patients with clinically positive outcomes

Clinically palpable nodal disease was present in 10 patients (Fig. 2). Of these, 7 underwent surgical management with radical BILND as well as a further PLND in 3 of these 7. Pathology returned with pN3 disease in 5 of 7 patients, 4 of whom received additional palliative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy prior to death and the remaining patient survived for 28 months with no evidence of disease before having a recurrence of his primary tumour. This patient is booked to undergo total penectomy for salvage. Of the 7, 2 patients had pN0 disease, 1 with no evidence of disease at last follow up and the other patient with pN0 disease had a metastatic deposit in the subcutaneous suprapubic tissue which was removed. He received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy and is also without evidence of disease at the most recent follow-up. The remaining 3 patients with clinically positive nodal disease were not surgical candidates due to extensive disease. Interestingly, 1 patient responded very well to chemotherapy and is presently alive with no evidence of disease. The other 2 patients died after palliative radiotherapy.

Fig. 2.

Clinically node positive outcomes. LND: lymph node dissection; d/t: due to; EBRT: external beam radiotherapy; NED: no evidence of disease; FU: follow-up; OR: operating room.

Statistical analysis

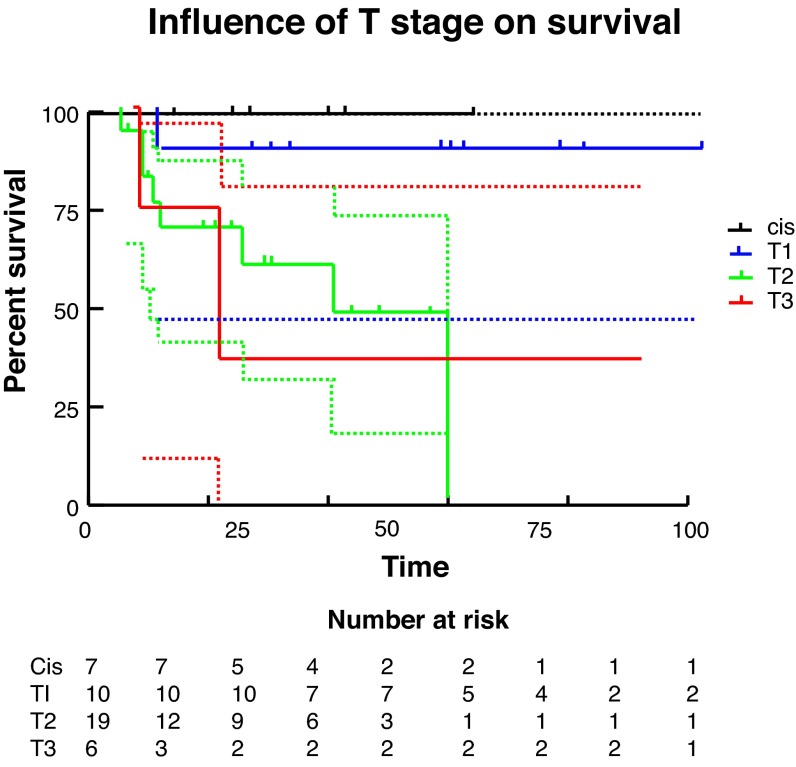

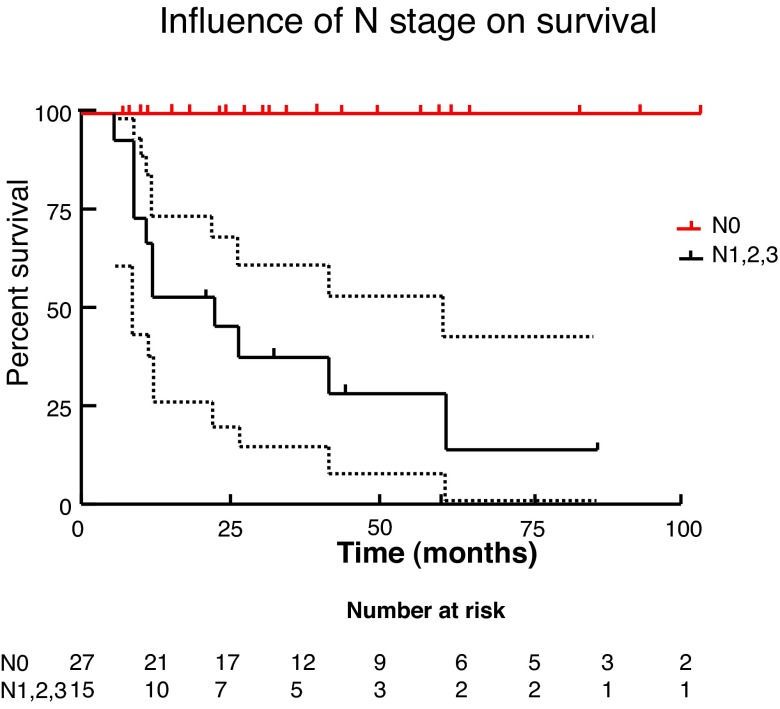

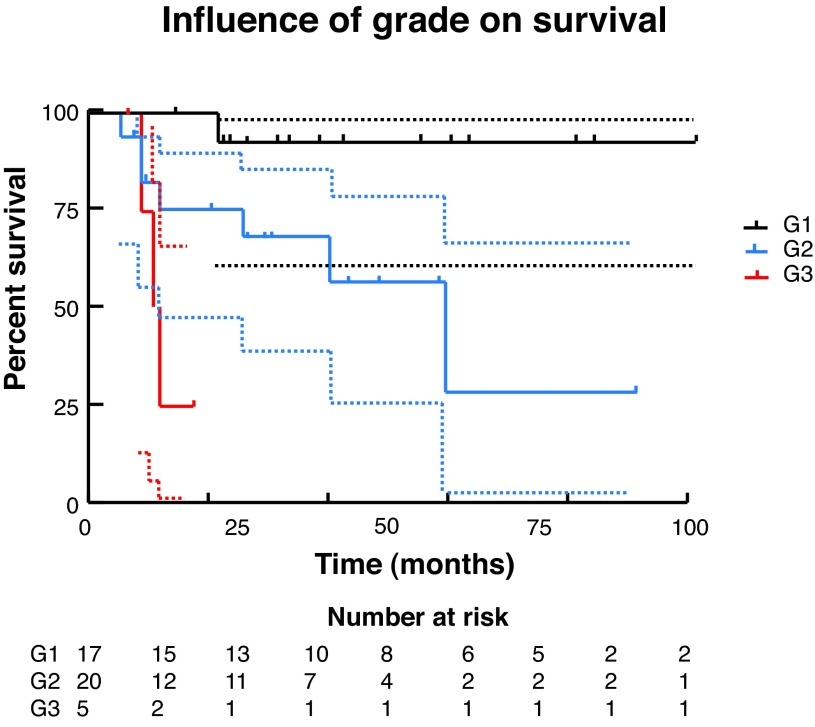

We used Kaplan-Meier methods to calculate survival curves and carry out univariate analysis to determine the influence of T stage, N stage, and grade on survival (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig 5). At the univariate level, all 3 factors significantly affected cancer-specific survival (CSS) with N stage being the most significant. We then carried out Cox regression for multivariate analysis. At this level, none of the factors remained significant, likely due to the small sample size.

Fig. 3.

Influence of T stage on survival. CIS: carcinoma in situ.

Fig. 4.

Influence of N stage on survival.

Fig. 5.

Influence of grade on survival.

Discussion

We found a high preponderance of known risk factors for penile SCC. Specifically, obesity, smoking history, absence of childhood circumcision were all frequent within our study population. These findings agree with previously published data.2 Unfortunately, we were unable to collect data on other reported risk factors, such as HPV status, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Penile SCC is much more frequent in developing countries and specifically among rural residents and those with low socioeconomic status.24 As such, we would expect the profile of patients seen in a tertiary care centre in Canada to reflect these differences as well. Moving forward, investigations into the role of HPV in penile SCC and any effects on prevention, prognosis, and treatment will be of great interest.25

In the present study, 10 patients presented with clinically palpable nodal disease – the strongest predictor of poor prognosis.26 Of these, 3 had such extensive disease that they were deemed inoperable and treated with palliative intent only. The remaining 7 patients underwent radical LND in line with EAU and NCCN guidelines.11,12 Unfortunately, the morbidity of this procedure is quite high, most frequently revolving around wound healing and lymphedema (ranging from 25%–50%).27,28 Within our group, 5 patients had pN3 disease and 4 died while the fifth survived 28 months before having a penile recurrence and is booked for salvage total penectomy.

Due to the high morbidity and poor outcome, regardless of surgical resection, we question the benefit of aggressive nodal dissection in this group of patients. In other disease sites of SCC, such as cervical or anal carcinoma, chemotherapy and radiotherapy play an important role in the management of nodal disease. As such, we propose that chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be beneficial in this setting. Salvage lymphadenectomy may best be considered after partial or complete response following this treatment strategy.

In regards to patients with clinically negative lymph nodes, we found a sustained CSS in those with low-risk primary tumours, as well as those with high-risk primaries who underwent prophylactic ILND and were stage pN0. However, we also found that many of our patients who met the criteria for high-risk pathology did not receive prophylactic ILND as per the guidelines.11,12 This is in keeping with previously published North American data.29

In analyzing these cases, there were two recurrent themes. Firstly, older patients with comorbidities who were not deemed good surgical candidates. Secondly, patients who declined further surgery due to concerns of potential morbidity. In two cases, patients underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy respectively, and both were alive without evidence of disease at last follow-up. This illustrates the inability to rigidly impose guidelines, but rather the importance of tailoring recommendations to the specific patient population. Due to the natural history of penile SCC, many patients are of advanced age and often have several comorbid conditions. In this setting, despite the preference for nodal dissection to obtain definitive pathology and for disease control, the operative risk and morbidity may be too high and chemotherapy or radiotherapy may offer reasonable alternatives. In vulvar carcinoma, which has many parallels to penile SCC, the roles of radiation and chemotherapy have been well-studied and we should endeavour to follow suit for penile SCC.30

Finally, survival analysis was carried out via Kaplan-Meier methodology and both univariate and multivariate analyses were completed to identify prognostic factors, specifically tumour T stage, N stage, and grade. Multivariate analysis via Cox regression did not demonstrate a significant association between either T or N stage or tumour grade and survival. This is likely due to the small sample in this study. Due to the limited incidence of this disease within Canada, multicentre collaboration would allow for improved analysis. On univariate analysis, increasing T stage, N stage and grade were all significantly associated with decreasing survival, with N stage being the most important. Median survival was 22 months for T3 disease, 41 months for T2 disease, and undefined for T1 or Tis disease. For any N stage >0, the median survival was 22 months. Grade 3 disease had median survival of only 11.5 months, while it is 60 months for grade 2 disease, and undefined for grade 1 disease.

Conclusion

This is the first epidemiologic report on penile SCC from a Canadian tertiary academic care centre. These findings confirm the poor survival of patients with positive lymph nodes in penile SCC. Patients with pN0 disease after prophylactic ILND had a durable CSS. Risk factors for penile SCC are elevated BMI, positive smoking history, and lack of circumcision. Survival analysis demonstrated that T stage, N stage, and grade were all possible predictors of CSS, although more data are needed to confirm this. Due to the low incidence in Canada of penile SCC, this study should be expanded to other national centres to better inform treatment decisions.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Beech and Dr. Power declare no competing financial or personal interests. Dr. Izawa is a member of the advisory board for Jannssen and was for Watson. He has received a commerical grant from Abbott. Dr. Pautler has received unrestricted grants from Paladin and Sanofi. He is currently participating in a clinical trial with Astellas. Dr. Chin is a member of the advisory boards for Profound Medical Inc., US HIFU, Amgem Canada, Sanofi-Aventis, AstraZeneca, Abbvie, Janssen Inc., Astellas, Minogue Medical, and Intuitive Surigical. He has received payment for service from Profound Medical Inc. He has also received grants from Profound Medical Inc., US HIFU, Astellas, Sanofi-Aventis, and Abbvie. He is currently participating in a clinical trial with Profound Medical Inc., US HIFU, Astellas, Sanofi-Aventis, and Abbvie.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Pettaway CA, Lynch D, Jr, Davis D. Tumors of the Penis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi L, Novick AC, et al., editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007. pp. 959–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pow-Sang MR, Ferreira U, Pow-Sang JM, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:S2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillner J, von Krogh G, Horenblas S, et al. Etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2000;205:189–93. doi: 10.1080/00365590050509913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sufrin G, Huben R. Benign and malignant lesions of the penis. In: Jy G, editor. Adult and Pediatric Urology. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical Publisher; 1991. p. 1643. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Penile cancer: Importance of circumcision, human papillomavirus and smoking in in situ and invasive disease. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:606–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar FH, Miles BJ, Plieth DH, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus in squamous neoplasm of the penis. J Urol. 1992;147:389–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maden C, Sherman KJ, Beckmann AM, et al. History of circumcision, medical conditions, and sexual activity and risk of penile cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:19–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Depasquale I, Park AJ, Bracka A. The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int. 2000;86:459–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Micali G, Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, et al. Penile cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:369–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Mirri F, et al. Penile carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus: A multicenter survey. J Urol. 2006;175:1359–63. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakenberg OW, Compérat E, Minhas S, et al. EAU guidelines on penile cancer: 2014 update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Penile Cancer (Version 1.2015). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slaton JW, Morgenstern N, Levy DA, et al. Tumor stage, vascular invasion and the percentage of poorly differentiated cancer: independent prognosticators for inguinal lymph node metastasis in penile squamous cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:1138–42. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horenblas S. Lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Part 2: The role and technique of lymph node dissection. BJU Int. 2001;88:473–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2001.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solsona E, Iborra I, Rubio J, et al. Prospective validation of the association of local tumor stage and grade as a predictive factor for occult lymph node micrometastasis in patients with penile carcinoma and clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes. J Urol. 2001;165:1506–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villavicencio H, Rubio-Briones J, Regalado R, et al. Grade, local stage and growth pattern as prognostic factors in carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol. 1997;32:442–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Lont AP, et al. Patients with penile carcinoma benefit from immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases. J Urol. 2005;173:816–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154565.37397.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDougal WS. Preemptive lymphadenectomy markedly improves survival in patients with cancer of the penis who harbor occult metastases. J Urol. 2005;173:681. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000153484.07200.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulkarni JN, Kamat MR. Prophylactic bilateral groin node dissection versus prophylactic radiotherapy and surveillance in patients with N0 and N1-2A carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol. 1994;26:123–8. doi: 10.1159/000475360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bermejo C, Busby JE, Spiess PE, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by aggressive surgical consolidation for metastatic penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:1335–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagliaro LC, Crook J. Multimodality therapy in penile cancer: When and which treatments? World J Urol. 2009;27:221–5. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagliaro LC, Williams DL, Daliani D, et al. Neoadjuvant paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin chemotherapy for metastatic penile cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3851–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leijte JAP, Kerst JM, Bais E, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced penile carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2007;52:488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalyal PL, Rambau PF, Masalu N, et al. Ten-year surgical experiences with penile cancer at a tertiary care hospital in northwestern Tanzania: A retrospective study of 236 patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:71. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0482-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bethune G, Campbell J, Rocker A, et al. Clinical and pathologic factors of prognostic significance in penile squamous cell carcinoma in a North American population. Urology. 2012;79:1092–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ficarra V, Akduman B, Bouchot O, et al. Prognostic factors in penile cancer. Urology. 2010;76:S66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koifman L, Hampl D, Koifman N, et al. Radical open inguinal lymphadenectomy for penile carcinoma: Surgical technique, early complications and late outcomes. J Urol. 2013;190:2086–92. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao K, Tu H, Li YH, et al. Modified technique of radical inguinal lymphadenectomy for penile carcinoma: Morbidity and outcome. J Urol. 2010;184:546–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thuret R, Sun M, Lughezzani G, et al. A contemporary population-based assessment of the rate of lymph node dissection for penile carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:439–46. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longpre MJ, Lange PH, Kwon JS, et al. Penile carcimoma: Lessons learned from vulvar carcinoma. J Urol. 2013;189:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]