Abstract

The cerebral cortex and cerebellum are high level neural centers that must interact cooperatively to generate coordinated and efficient goal directed movements, including those necessary for a well-timed conditioned response. In this review we describe the progress made in utilizing the forebrain-dependent trace eyeblink conditioning paradigm to understand the neural substrates mediating cerebro-cerebellar interactions during learning and consolidation of conditioned responses. This review expands upon our previous hypothesis that the interaction occurs at sites that project to the pontine nuclei (Weiss & Disterhoft, 1996), by offering more details on the function of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex during acquisition and the circuitry involved in facilitating pontine input to the cerebellum as a necessary requisite for trace eyeblink conditioning. Our discussion describes the role of the hippocampus, caudal anterior cingulate gyrus, basal ganglia, thalamus, and sensory cortex, including the benefit of utilizing the whisker barrel cortical system. We propose that permanent changes in the sensory cortex, along with input from the caudate and claustrum, and a homologue of the primate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, serve to bridge the stimulus free trace interval and allow the cerebellum to generate a well-timed conditioned response.

The neuronal substrates of memory and associative learning have been a major topic of investigation, and several behavioral paradigms have been developed to examine these mechanisms during acquisition, consolidation and extinction. Eyeblink conditioning (EBC) and fear conditioning are two widely used paradigms to study associative learning. The neural substrates and cellular mechanisms that underlie them are relatively well understood (Disterhoft & Oh, 2006; De Zeeuw & Yeo, 2005; Fanselow & Poulos, 2005; Christian & Thompson, 2003; Myer, Bryant, DeLuca & Gluck, 2002; Ivry, 1997; Sigurdsson, Doyere, Cain & Ledoux, 2006; Maren, 2005; Kim & Jung, 2006; Sacchetti, Scelfo & Strata, 2005; Rudy, Huff & Matus-Amat, 2004; Atallah, Frank & O’Reilly, 2004; Everitt, Cardinal, Parkinson & Robbins, 2003), as are the stimulus parameters for achieving optimal conditioning (Schneiderman, Fuentes, Gormezano, 1962; Schneiderman & Gormezano, 1964; Weiss, Knuttinen et al., 1999; Davis, 1989; Davis, Schlesinger, Sorenson, 1989). These two Pavlovian conditioning paradigms rely on the paired presentation of a conditioning stimulus (CS) and an unconditioned stimulus (US) to evoke a conditioned response (CR) that ameliorates the aversive nature of the US after training (Pavlov, 1927). The CS is often a tone and the US is an airpuff to the eye (or a periorbital shock) for eyeblink conditioning, or an aversive shock to the paws for fear conditioning. The CR is clearly evident on individual trials by its onset prior to presentation of the US, or by its presence on CS alone test trials (see Fig. 1). Both paradigms have been useful for studies on the genetic, molecular, and biophysical basis of learning and memory with transgenic, knockout, and mutant mice (Kishimoto et al., 2006; Koekkoek et al., 2005; Bao et al., 1998; Weiss et al., 2002; Ohno, Tseng, Silva, Disterhoft, 2005), however this review will focus on the EBC paradigm.

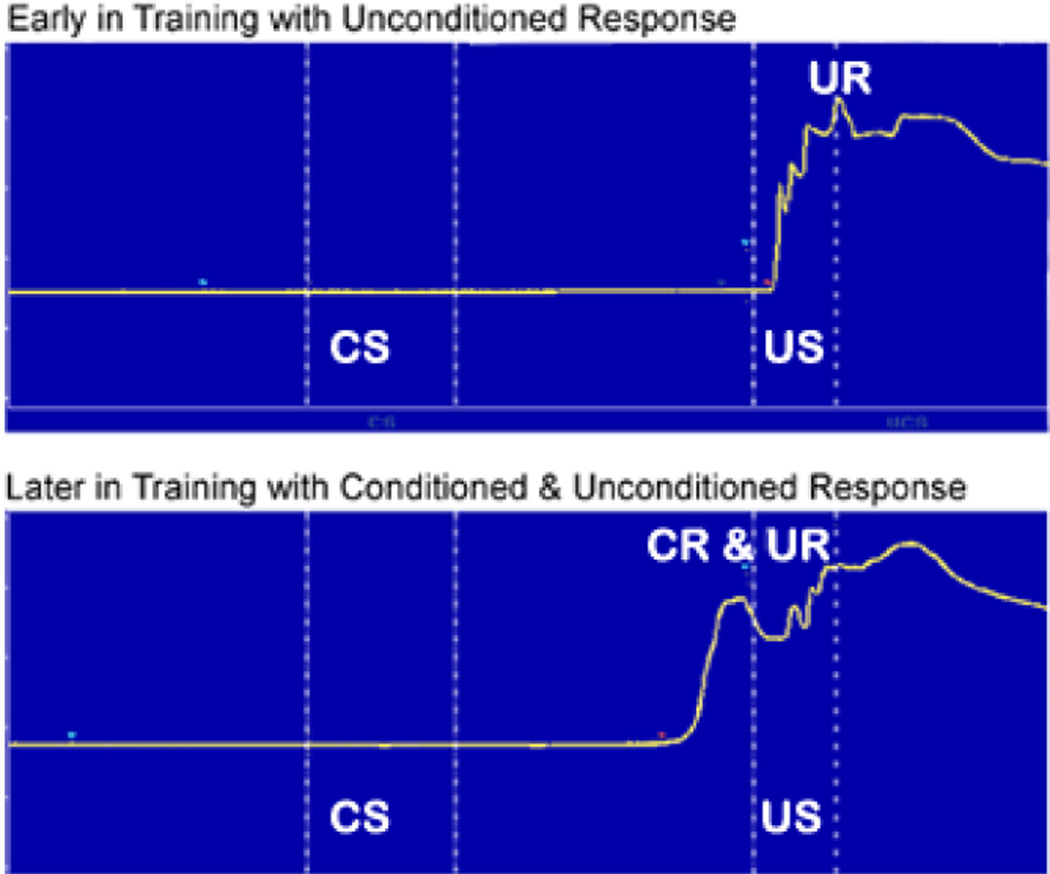

Figure 1.

Examples of behavioral responses early and late in training during trace eyeblink conditioning. The CS was 250 ms and was 150 ms. Extension of the nictitating membrane (representing a blink) is indicated by an increase in voltage across time. Early in training there is an unconditioned response (UR) to the corneal airpuff US. Later in training the rabbit has learned that the CS predicts the presentation of the US and exhibits a conditioned response (CR) that is evoked by the CS and tends to peak at the time of US onset.

The cerebral cortex and cerebellum, especially the motor cortex and premotor areas, are high level neural centers that must interact cooperatively to generate coordinated and efficient goal directed movements. A recent review (Ramnani, 2006) described how this interaction could occur using efference copies of motor commands in a feed forward model of motor control such that prefrontal circuits could use their flexibility to solve new motor problems and allow the cerebellum to adjust its circuits to eventually make movements automatically. This review will describe the details of the neuronal substrates and interconnections between prefrontal cortex and cerebellum that might mediate this interaction, especially in regard to associative motor learning during trace eyeblink conditioning.

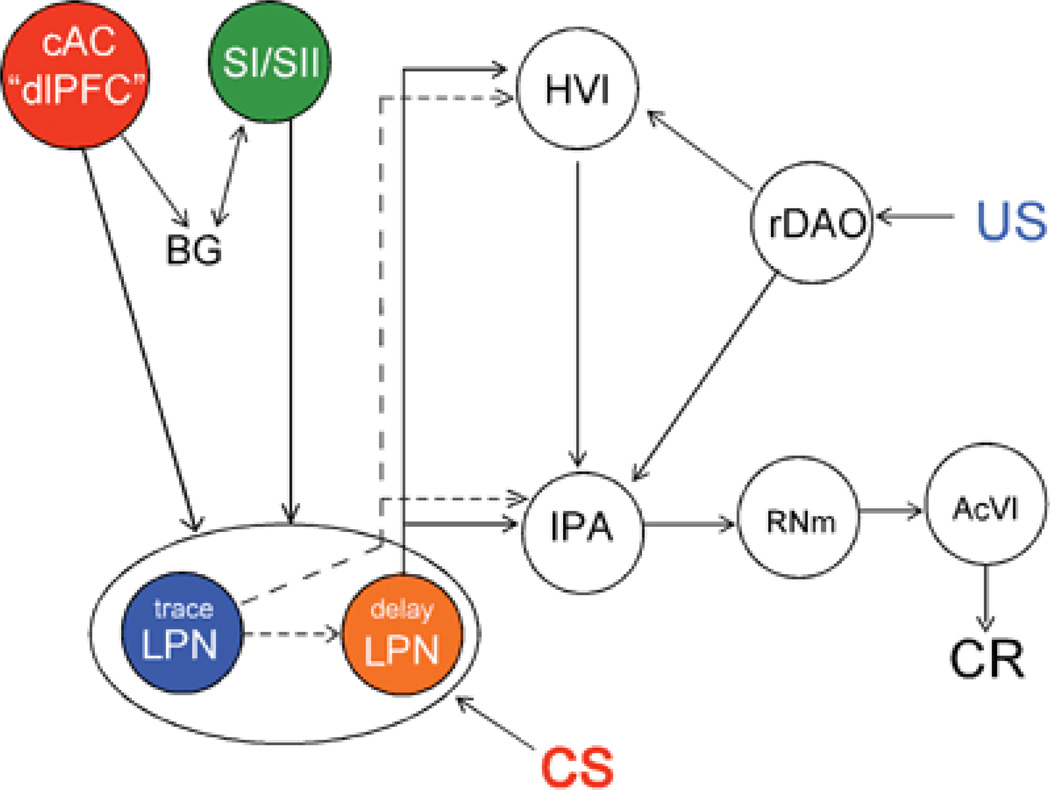

Interactions of the cerebellum and hippocampus during eyeblink conditioning have been demonstrated by abolition of trace conditioned blinks following hippocampal lesions (Moyer et al., 1990; Solomon et al., 1986) or of dentate-interpositus lesions (Woodruff-Pak, Lavond & Thompson, 1985), and by the abolition or prevention of conditioned hippocampal pyramidal neuron activity following lesions of the cerebellar nuclei (Clark et al., 1984; Sears & Steinmetz, 1990; Sears, Logue & Steinmetz, 1996; Ryou et al., 1998). These bidirectional lesion effects of the hippocampus and cerebellum are evidence that interactions between the two regions are required, especially for mediating forebrain-dependent trace eyeblink conditioning where the offset of the CS and onset of the US are separated in time. Determining the nature of the interaction between the two regions is challenging since there are no direct connections from one region to the other. Several years ago we proposed a circuit that could functionally connect the two regions via the frontal cortex and pons (Weiss and Disterhoft, 1996). We have since expanded and modified that circuit based on our lesion (Weible et al., 2000), electrophysiological (Weible et al., 2003), and anatomical (Weible, Weiss & Disterhoft, submitted) studies of the cingulate gyrus within the frontal cortex. The additional parts of the revised circuit include a required attentional role for the caudal anterior cingulate gyrus (cAC) for acquisition, involvement of the basal ganglia (especially the caudate and claustrum) in associating the CS and US, the possibility of permanent memory storage within the sensory cortex that mediates the CS, and the role of interconnections between the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex or subiculum for mediating permanent memory storage in the neocortex. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), which has been identified in primates as a region involved in the planning of motor actions and which has a percentage of neurons that maintain their increased firing rate to a conditioned cue (Fuster, 1973), is an area of interest that has been omitted because it has not yet been adequately characterized functionally in the rabbit or rodent brain. A summary diagram of the interconnections of these nuclei that might mediate cortico-cerebellar interactions during trace eyeblink conditioning is shown in Figure 2. Each of these areas plus the cerebellum and hippocampus will be discussed in the following sections.

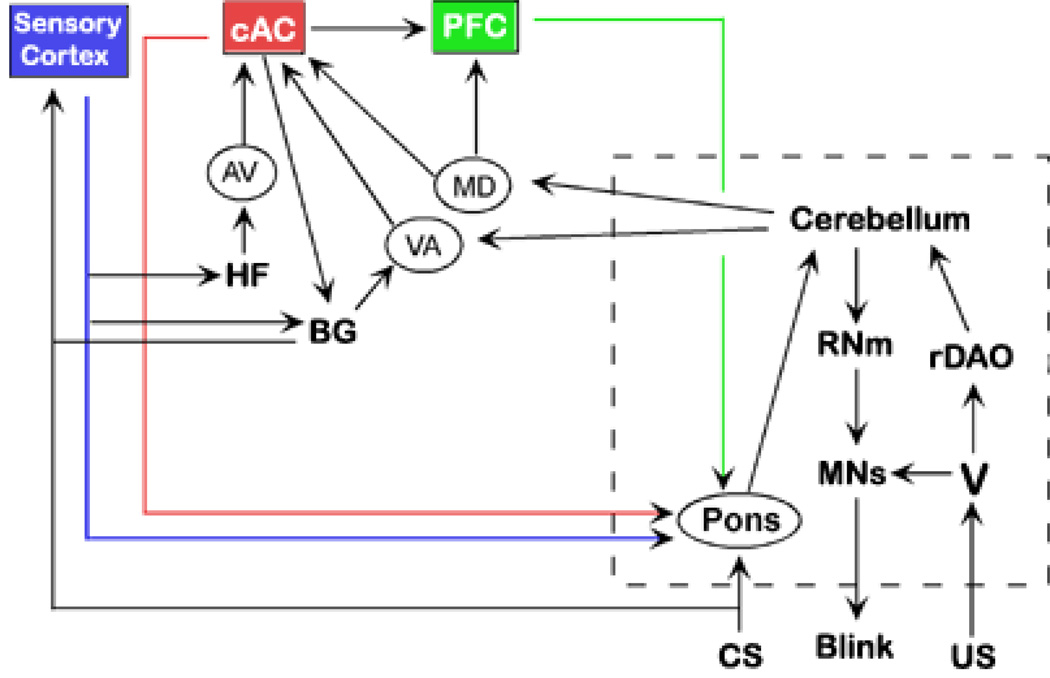

Figure 2.

A schematic of the connections that might mediate trace eyeblink conditioning (arrows do not necessarily indicate monosynaptic connections). The circuit shows a forebrain circuit that converges upon the cerebellar circuit. The structures mediating delay conditioning are enclosed by the dashed box. AV anteroventral thalamus; BG basal ganglia; cAC caudal anterior cingulate; PFC prefrontal cortex; HF hippocampal formation; rDAO rostral dorsal accessory olive; MD dorsomedial thalamus; MNs motor neurons; PFC prefrontal cortex; RNm magnocellular red nucleus, V trigeminal nucleus, VA ventral anterior thalamus.

Cerebellum & Hippocampus

The cerebellum was first found to be essential for delay conditioning by Thompson and colleagues (McCormick, Clark, Lavond & Thompson, 1982; Clark, McCormick, Lavond & Thompson 1984). Lesions of the cerebellar interpositus nucleus abolished previously acquired CRs and prevented the acquisition of CRs (Lavond & Steinmetz, 1989; Lewis, Lo Turco, Solomon, 1987). The fact that the unconditioned response (UR) was still intact indicates that the impairment was not related to the motor system per se. Since CRs could be retained following complete decerebration of conditioned rabbits (Mauk & Thompson, 1987), the cerebellum and its associated brainstem circuitry appear to be sufficient to mediate delay conditioning. Similarly, cerebellar lesions in human patients prevent EBC (Daum, Schugens, et al., 1993; Bracha et al., 2000; Gerwig et al., 2006) and an age-related loss of cerebellar Purkinje neurons parallels an impairment in behavioral conditioning (Woodruff-Pak, 1988).

The hippocampus was subsequently found by lesion experiments to be essential for trace EBC where the memory demands of the paradigm are increased by separating the CS and US in time (the cerebellum is also required for trace conditioning, Woodruff-Pak et al., 1985). A stimulus free trace interval of 500 ms was found to be sufficient to require hippocampal function in rabbits (Moyer et al., 1990; Solomon et al., 1986) and 250 ms was found to be sufficient for rats (Weiss, Boumeester et al., 1999) and mice (Tseng, Guan, Disterhoft & Weiss, 2004). Since the lesioned animals had intact URs and acquired CRs when the trace interval was reduced to zero (so that the CS and US were contiguous in time), the data suggest that the cerebellum and hippocampus mediate associative processes involved in conditioning as opposed to pure sensory or motor roles. The lack of responses to CS alone trials following the presentation of explicitly unpaired stimuli further supports the associative nature of the learning, i.e. pseudoconditioning did not occur.

But, why does the cerebellum require hippocampal input when the trace interval is longer than a critical duration? Weiss and Disterhoft (1996) proposed that hippocampal circuitry is needed to potentiate the effect of the CS at the pontine nuclei on its way to the cerebellum where the CS and US are integrated within the cerebellar cortex and deep nuclei. Thompson (1986) summarized data and proposed a cerebellar centered circuit that would receive CS information from the brainstem and pons via mossy fibers to Purkinje cells and the deep nuclei, and US information from the brainstem and inferior olive to Purkinje cells and the deep nuclei. The mechanism underlying CS-US associations during delay conditioning may be long term depression (LTD) of parallel fiber – Purkinje cell synapses (Karachot, Kado, Ito, 1994) or of mossy fiber-deep cerebellar nuclear synapses (Zhang & Linden, 2006), which are both critically dependent on the relative timing of the two inputs. Mutant mice which are deficient in LTD in cerebellar cortex have impaired delay eyeblink conditioning (Aiba et al., 1994), and a transgenic mouse (L7-PKCI) with Purkinje cell specific inhibition of protein kinase C has impaired adaptation of the vestibular-ocular reflex (De Zeeuw et al., 1998), another form of associative motor learning. These results suggest that LTD may mediate cerebellar dependent motor learning when the stimuli are appropriately timed. Although most experiments examining LTD use conjoint stimulation of the parallel fibers and Purkinje cell (a timing not compatible with EBC), Schreurs (Freeman, Shi & Scheurs, 1998; Scheurs, Oh & Alkon, 1996) omitted GABA blockers (bicuculline) from their recording chamber and reported pairing-specific long-term depression of Purkinje cell EPSPs (a form of LTD) from rabbit cerebellar slice by pairing a high frequency train of stimuli to the parallel fibers 80 ms before a brief low frequency train to the climbing fiber input. Thus, LTD within cerebellar cortex may help to mediate associative motor learning, but more evidence is needed to confirm this hypothesis (Mauk, Garcia, Medina & Steele, 1998), and hippocampal based inputs to the cerebellum may facilitate LTD when the timing of CS and US is less than optimal (Raymond, Lisberger & Mauk, 1996).

Learning dependent changes that occur in the hippocampus involve an increase in the intrinsic excitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, i.e., the post burst afterhyperpolarization (AHP) of neurons recorded from slices of previously conditioned rabbits is reduced relative to the AHP recorded from neurons of rabbits that were presented with an equivalent number of stimuli in an explicitly unpaired fashion (Disterhoft, Coulter & Alkon, 1986). This increased excitability is transient (Moyer Thompson, Disterhoft, 1996) and was found to decrease gradually to baseline levels within a two week period following the time at which the rabbits achieved a behavioral criterion of 80% CRs (no further training was given after criterion was achieved). Conditioning related activity was more robust on the day of initial CR performance, as compared to either the day before or two days after initial CR performance as found with in vivo recordings of hippocampal pyramidal neurons during trace eyeblink conditioning (McEchron & Disterhoft, 1997; Weible et al., 2006). Similar results were found in monkeys learning a visual association task (Wirth et al., 2003). The first conditioning specific changes in activity occur even earlier in the trial sequence during delay conditioning (Berger, Alger & Thompson, 1976), perhaps because the task is learned much more quickly than trace conditioning. However, even though hippocampal changes occur with delay conditioning procedures, it is interesting that the task can be learned without a functioning hippocampus. The response profiles of many hippocampal pyramidal neurons during delay conditioning mimics the amplitude and time course of CRs (Solomon et al., 1983), and have been referred to by many as neuronal models of behavior. The response profiles during trace conditioning are much more diverse, do not tend to reflect the shape of the CR, and include many neurons with decreases in activity relative to baseline (Weiss, Kronforst-Collins & Disterhoft, 1996; Weible, et al., 2006). The significance of this response diversity still needs to be better understood but clearly may reflect the more complex hippocampal processing required for successful trace conditioning.

Lastly, most studies examining in vivo hippocampal physiology during trace EBC have concentrated on area CA1 since it is the output of the hippocampus proper. However, a systematic study of neuronal responses and interactions among the entorhinal cortex, hippocampus (areas CA1 and CA3) and subiculum (an output of the hippocampus) is clearly needed to better understand the processing of information necessary for hippocampal-dependent learning and hippocampal-cortical-cerebellar interactions that might mediate memory.

Caudal Anterior Cingulate Gyrus (cAC)

Although hippocampal neurons exhibit learning related changes in activity prior to the expression of trace CRs, the earliest changes we have recorded so far have been found in the cAC (Weible et al., 2003), an area that when lesioned prevents acquisition of trace CRs (Weible et al., 2000). These changes occurred during the first 10 CS-US pairings. The acquisition deficits observed by Weible and colleagues are in agreement with findings from an earlier study by Kronforst-Collins and Disterhoft (1998) who demonstrated that lesions of the frontal poles resulted in acquisition deficits only when the area damaged included the cAC (or caudal medial prefrontal cortex). These two studies clearly indicate a role for the cAC in the acquisition of trace EBC. However, the nature of that role remained unknown until we examined the activity of single neurons in vivo across 10 days of trace conditioning and compared neuronal responses to conditioned (tone) and unconditioned (air-puff) stimuli when presented in either a paired (trace conditioning) or unpaired (pseudo conditioning) fashion. Neurons were grouped according to whether they exhibited significant increases or decreases in firing rate during one or more specified trial intervals. Robust CS-elicited increases and decreases in firing rate were observed at the onset of training. During trace conditioning, significant CS-elicited increases continued across training sessions, with the greatest proportion of responsive neurons being observed during the first two training sessions. During pseudoconditioning, the mean increase in firing rate in response to the CS was initially comparable to that observed during trace conditioning, but then declined rapidly to baseline levels within the first 30 training trials, with no difference in the proportion of neurons exhibiting significant CS-elicited increases in firing rate observed across sessions. Neurons exhibiting significant CS-elicited increases in firing rate also exhibited increases in response to the US that were more robust than US-elicited responses observed during pseudo conditioning. The single neuron data from this study suggest that neurons of the cAC, most robustly involved early in training, indicate behavioral salience of stimuli that were originally neutral, and hence mediate an attentional role during the conditioning process. An example of the single neuron data is shown in figure 3.

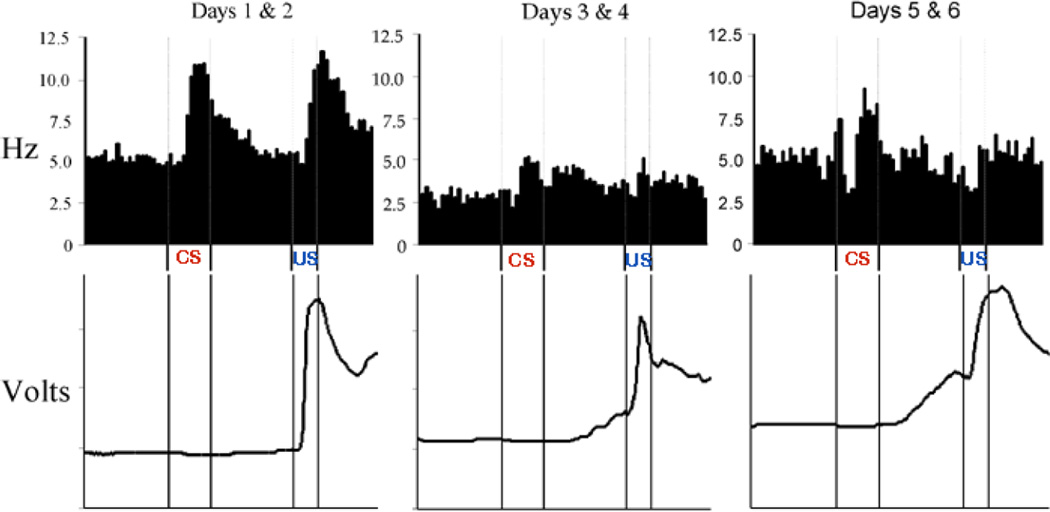

Figure 3.

cAC neurons exhibit robust responses to the  and

and  during the first two sessions of trace conditioning. The top panels show that the responses gradually return towards the baseline level of activity (which is lower than at the start of training) during sessions 3 & 4, and then increase again as CRs begin to be emitted during sessions 5 & 6. The bottom panels show mean blink responses for the sessions (up is extension of the nictitating membrane).

during the first two sessions of trace conditioning. The top panels show that the responses gradually return towards the baseline level of activity (which is lower than at the start of training) during sessions 3 & 4, and then increase again as CRs begin to be emitted during sessions 5 & 6. The bottom panels show mean blink responses for the sessions (up is extension of the nictitating membrane).

Subsequent analyses of the afferent and efferent connections of the cAC support the hypothesized attentional role in conditioning. We injected wheatgerm agglutinin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) into the region of cAC that affects trace EBC (Weible, Weiss & Disterhoft, submitted) and found retrograde labeling of neurons in the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (HDB) and the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM). Both the HDB and the NBM are components of the basal forebrain cholinergic system which is involved in a range of cognitive functions, including EBC and the control of attention (Everitt & Robbins, 1997; Sarter et al., 2005). The importance of the cholinergic system for EBC and hippocampal physiology has been known for many years. Solomon et al (1983) demonstrated that scopolamine (a cholinergic antagonist) impairs EBC by its actions within the hippocampus. Aging is also often associated neuroanatomically with an impaired cholinergic system (Bartus, Dean, Beer, & Lippa, 1982; Coyle, Price, & DeLong, 1982; Coyle, Price, & DeLong, 1983; Hagan et al., 1988; Solomon, Groccia-Ellison, Levine, Blanchard & Pendlebury, 1990) and behaviorally with impaired EBC (Knuttinen, Gamelli, Weiss, Power & Disterhoft, 2001; Knuttinen, Power, Preston & Disterhoft, 2001; Moyer, Power, Thompson & Disterhoft, 2000; Solomon, Beal & Pendlebury, 1988; Thompson, Moyer & Disterhoft, 1996). The behavioral impairment is ameliorated with cholinergic agonists and cholinesterase inhibitors (Kronforst-Collins et al., 1997; Weiss et al., 2000; Simon et al., 2004; Weible et al., 2004; Woodruff-Pak, Vogel, Wenk 2001). Aside from being at least partially responsible for age-related impairments, the cholinergic system may facilitate an attentional role for the cAC by its connections from the NBM and HDB, structures which are themselves particularly vulnerable to aging (Smith & Booze, 1995). The cAC could then affect the hippocampus via thalamo-cortical, striatal-cortical, or claustral-cortical projections as shown in Figure 4.

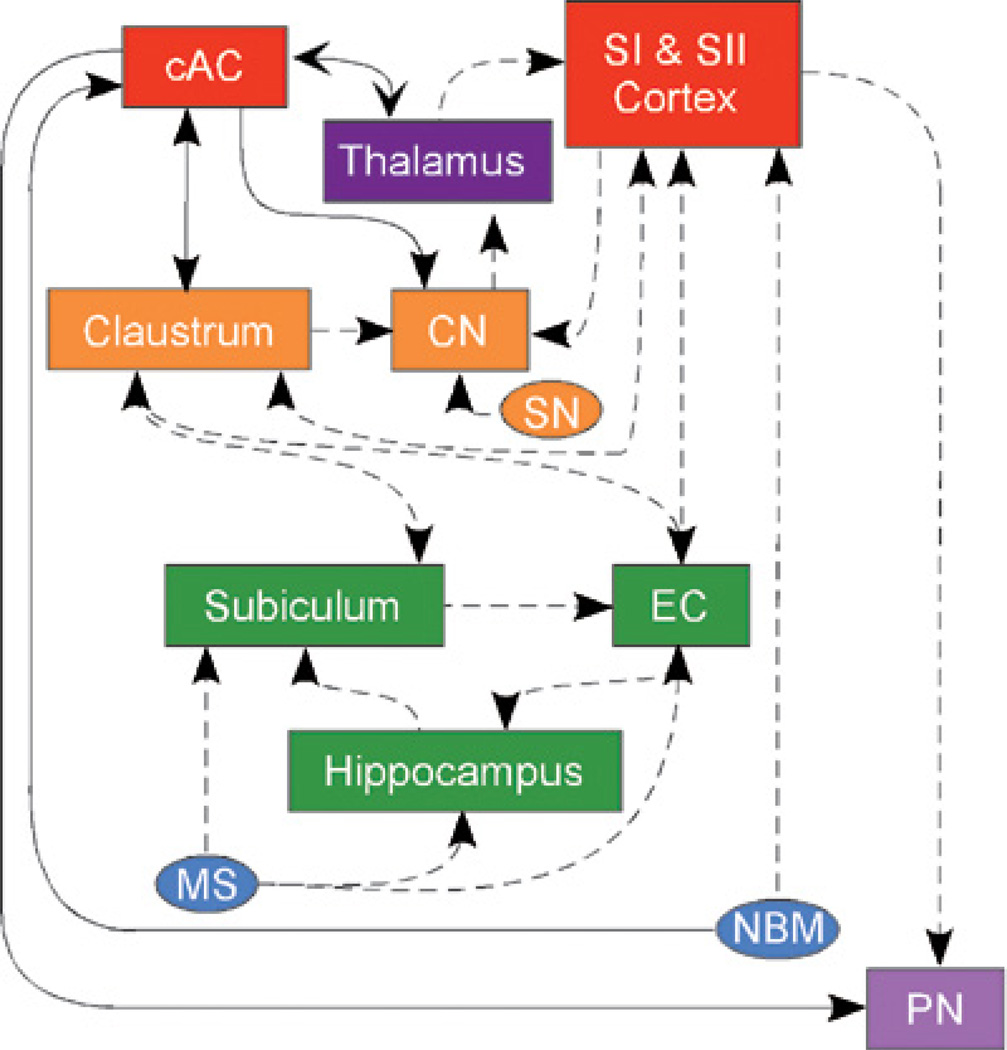

Figure 4.

Connections of the cAC that might mediate an attentional role that facilitates acquisition of forebrain dependent eyeblink conditioning. CN caudate nucleus; SN substantia nigra; EC entorhinal cortex; MS medial septum; NBM nucleus basalis Meynert; PN pontine nuclei. Connections represented by solid connections were demonstrated by Weible et al. (submitted).

The cAC could also affect the cerebellum directly via projections to the pontine nuclei which we have shown with the histochemical detection of transported WGA-HRP (Weible et al., 2006) and with the transport of MnCl2 which is visualized with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, unpublished observations). The later projections may be to either the same pontine cells that relay CS information to the cerebellum during delay conditioning, or to a separate population of pontine neurons (“trace pontine cells”) that then project on to the “delay pontine cells.” Although more experiments are needed to determine which of these two possibilities exists, recent data from Mauk’s laboratory (Kalmbach et al., 2006) suggest that there are at least two different populations of pontine cells mediating delay and trace conditioning. A diagram illustrating these possibilities is shown in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Projections to pontine cells that could mediate trace and delay conditioning. The figure indicates that there could be one or more populations of pontine neurons that relay the CS to the cerebellum. cAC caudal anterior cingulate gyrus; SI/SII primary and secondary somatosensory cortex; BG basal ganglia; HVI hemispheric lobule six; rDAO rostral dorsal accessory olive; IPA anterior interpositus nucleus; RNm magnocellular red nucleus; AcVI accessory abducens nucleus (controls eyeball retraction and extension of the nictitating membrane), LPN lateral pontine nucleus. Arrows do not necessarily indicate monosynaptic connections.

Hippocampus and Frontal Cortex

The hippocampus is necessary for acquisition of trace EBC according to lesion studies (Moyer et al., 1990; Solomon et al., 1986), but since patient H.M. (who had bilateral resection of the temporal lobes to treat his epilepsy, Scoville & Milner, 1957) has intact remote autobiographical memories, the hippocampus would not be expected to be required for the retrieval and expression of previously acquired trace CRs. This prediction was supported by a lesion study in rabbits (Kim et al., 1995) which showed that hippocampal lesions abolished CRs if done one day following behavioral criterion, but not if done 30 days after criterion. Similar results have been found for the rat (Takehara, Kawahara & Kirino, 2003) and mouse (Takehara, Kawahara, Takatsuki & Kirino, 2002), and as mentioned previously, learning related changes in the AHP of hippocampal pyramidal neurons return to baseline within one to two weeks following behavioral criterion (Moyer, Thompson & Disterhoft, 1996).

Circumscribed hippocampal lesions in humans also leave remote autobiographical memories intact (Bayley, Gold, Hopkins & Squire, 2005) as suggested by the effects of a more global temporal lobectomy as in the case of patient H.M. Thus, the hippocampus appears to be necessary for trace eyeblink conditioning only temporarily during initial acquisition and consolidation. The cortex is hypothesized to contain the site of permanent memories (Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991; McClelland et al., 1995; Rolls & Kesner, 2006). The data clearly support the conclusion that the hippocampus and cerebellum are involved in trace EBC, but how and where the trace interval is encoded is still unknown. We hypothesize that this site will be at a cortical region with access to the pons, as suggested earlier (Weiss & Disterhoft, 1996).

As mentioned previously, the rabbit homologue of the primate dlPFC is an obvious part of frontal cortex to examine during trace EBC. In primate, this region receives input from the cerebellum via the dorsomedial (MD) thalamus (the VL thalamus also receives input from the cerebellum but does not appear to be related to conditioned hippocampal activity, Sears, Logue & Steinmetz, 1996). The elegant transneuronal tracing studies in nonhuman primates from Peter Stick’s laboratory revealed differences between cerebello-cortical loops that might mediate motor activity or cognition (Kelly & Strick, 2003), and which could explain the differential activation of conditioned hippocampal activity related to the VL and MD thalamus. They found that area MI (representing the arm, but a similar connection should be present for eye related regions) is reciprocally linked to discrete areas in cerebellar hemispheric lobules IV-VI, whereas area 46 of the dlPFC is reciprocally linked with Crus II of the cerebellar cortex. These results are consistent with an involvement of HVI, IPA and VL thalamus in forebrain-independent delay conditioning and suggest that Crus II, MD thalamus and dlPFC are involved in forebrain-dependent trace conditioning.

Several studies in primates have shown that neurons in the dlPFC have activity that persists throughout the delay period in delayed matching to sample tasks (Bodner, Kroger & Fuster, 1996; Fuster, 1990, 1991; Wallis & Miller, 2003; Funahashi, 2006), a feature that could mediate working memory processes. Fuster et al (2000) demonstrated that the responses of neurons were sensitive to cues specific for another stimulus, e.g. a specific tone indicating which color to pick for a reward (Quintana, Yajeva & Fuster, 1988). Activity related to oculomotor behavior, especially saccades, is also recorded from neurons of the dlPFC (Pierrot-Deseilligny et al, 2003, 2004). Finally, age-related changes in the microcolumnar organization of area 46 in rhesus monkeys are significantly correlated with age-related declines in cognition (Cruz, Roe, Urbanc, Cabral, Stanley & Rosene, 2004). All of these results suggest that the homologue of area 46 in the dlPFC should be appropriate to mediate the trace interval during EBC.

The delay period in delay match to sample tasks might be mediated by the same circuitry even though the delay match to sample task uses a much longer delay than does trace eyeblink conditioning, i.e. several seconds vs 0.5 sec. Recordings from this region will be necessary to determine if in fact neurons in the rabbit dlPFC mediate the trace interval, however the rabbit homologue of the primate dlPFC is not well understood or identified. Projections from the MD thalamus should be quite useful to identify this region since this is how the dlPFC is usually defined (Rose & Woolsey, 1948). The dlPFC may in fact mediate the trace interval, but its role is likely to be one involved in planning the response rather than executing the response. Identifying the location of these neurons will be necessary in order to record and characterize their response patterns during conditioning.

Buchanan and colleagues (Buchanan et al., 1989) injected HRP or WGA-HRP into the MD thalamus in rabbits and identified a midline region of labeled cells that may be the rabbit homologue of the dlPFC. This was confirmed anatomically by them with injections of WGA-HRP into the target region, and was similarly confirmed by Arikuni and Ban (1978). This region is shown in their Figure 1B and resulted from an HRP injection that was restricted to the MD thalamus. The retrogradely labeled cells were found within a column of cells that appears to be within layers 5 and 6 of the midline cortex rostral to the genu of the corpus callosum, and appear to be near the border of the rostromedial and caudalmedial anterior cingulate gyrus as defined by Weible et al. (2000). The location of these neurons also appears to be deeper than those recorded by Weible et al. (2003) which suggests that a more thorough survey of the anterior cingulate gyrus will be necessary to determine if any of the neurons exhibit persistent firing during the trace interval, and if this slightly more anterior region of midline cortex is indeed the rabbit homologue of the primate dlPFC.

The Role of Sensory Cortex in Trace Eyeblink Conditioning

The most common sensory modality for studying EBC has been sound, either pure tones or white noise. We started using stimulation of the mystacial vibrissae (Das et al. 2001; Galvez et al., 2006) during EBC in order to take advantage of the well defined somotopic arrangement of neurons that respond to whisker stimulation in rabbits (Gould, 1986) to facilitate defining changes in processing of the conditioned stimulus that may occur during associative learning. Although most studies of the whisker cortex have been done in rat or mouse (Woolsey & Van der Loos, 1970, Woolsey, 1996) the rabbit offers the advantages of being amenable to restraint while fully conscious, and has a skull large enough to easily support the hardware necessary for large scale recording studies. Swadlow has studied cortical networks in the rabbit whisker cortex (Swadlow, 2002; Swadlow et al., 2005) and we have begun to study learning-related changes in the rabbit barrel cortex (Galvez et al., 2006 a,b). Das et al. (2001) demonstrated delay EBC with whisker vibration as a CS in the rabbit and Galvez et al. (2006a) demonstrated trace EBC and a learning specific expansion of the stimulated whisker cortical barrels as visualized with cytochrome oxidase. The whisker signaled CRs were robust enough to be triggered by stimulation of a single whisker after conditioning to a row of whiskers, and the row-specific expansion was especially impressive given that there was only a total of 125 seconds of whisker vibration during the entire experiment (the summed time of vibrissae vibration during the average number of trials to criterion across several days of training). Finally, rabbit EBC was successful when microstimulation of the barrel cortex was substituted for a vibrissae CS using a (presumably) non-hippocampal 250 msec trace paradigm (Leal-Campanario et al., 2006).

Tactile information in the vibrissae system travels from individual whiskers to cortex in a one-to-one orientation via a tri-synaptic pathway (maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve to medullary barrelets to thalamic barreloids to somatosensory barrel cortex, Woolsey & Van der Loos, 1970; Woolsey, 1996). The primary sensory neurons of layer IV are arranged in an orderly matrix of barrel-like groupings of neurons with each barrel predominantly representing a single whisker. This arrangement can be seen in rodent brain with Nissl stained sections and with the metabolic marker cytochrome oxidase (Land & Simons 1985; Wong-Riley & Welt, 1980) when the sections are cut tangentially to the cortical surface. The rabbit also has an exquisitely precise whisker representation (Gould, 1986), but the anatomical arrangement is not evident in Nissl stained sections as it is in the brains of rodents. Cortical “barrels” are however evident in the rabbit brain with the metabolic marker cytochrome oxidase and neurons within the cytochrome oxidase rich patches are responsive to vibration of individual whiskers (Galvez, et al., 2006a). Thus, we can easily combine anatomical, physiological, and behavioral measures to analyze neural mechanisms of learning.

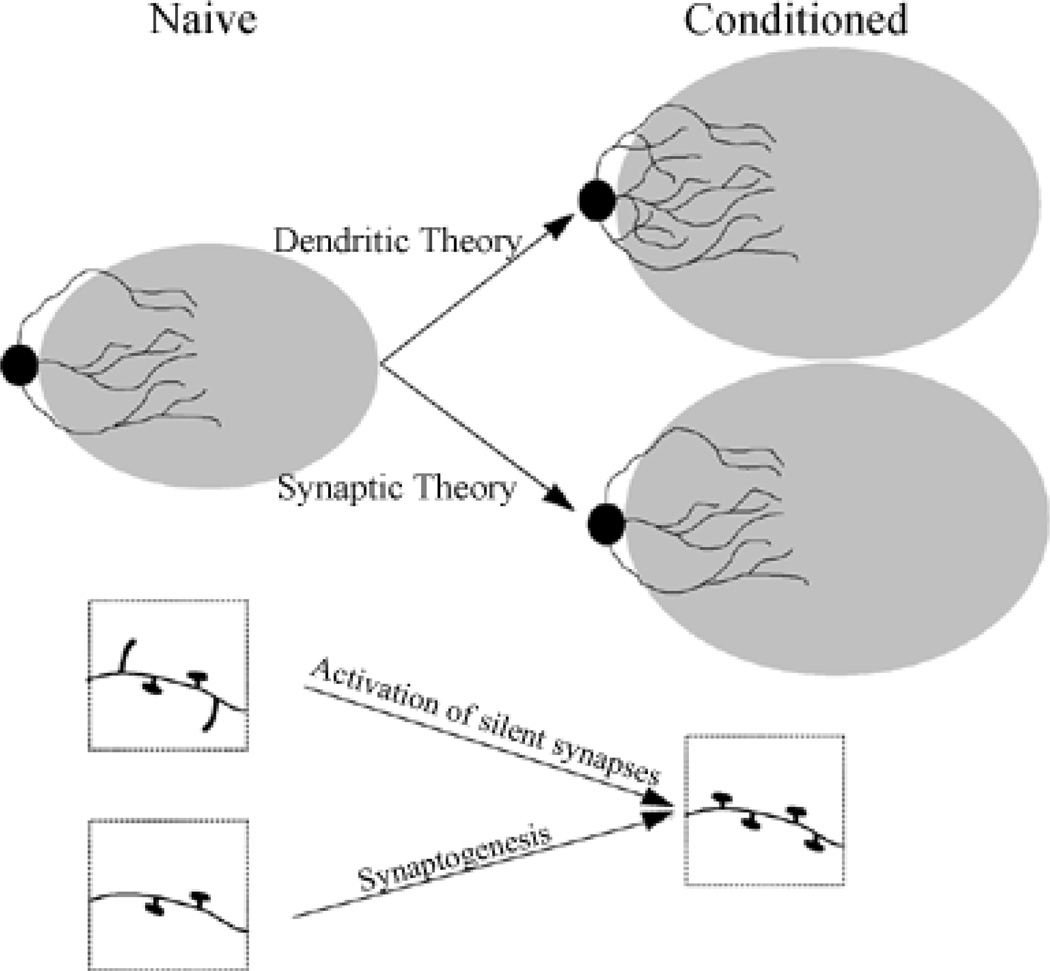

Our recent studies of the primary barrel cortex suggest that the CS-activated cortical barrels are critical for acquisition of trace conditioned blinks. We have four lines of evidence to support this contention (Galvez et al., 2006b). First, pretraining lesions of the barrels associated with the whiskers subsequently stimulated during conditioning prevent acquisition of the task. Second, lesions of barrels associated with whiskers that were not stimulated did not impair behavior, i.e. the learning was not different from saline injected controls. Third, the neurons responsive to the whiskers that were stimulated for the CS exhibit learning specific increases in their CS evoked firing rate (unpublished data). Fourth, we have demonstrated a learning specific expansion of barrels activated by the CS (Galvez et al., 2006a). The lesion effect is not due to a loss of perception since 1) the rabbits exhibit CRs to the CS when shifted to a delay paradigm dependent solely upon neural circuitry of the brainstem and cerebellum, and 2) rabbits given the same lesion after training exhibit an initial drop in performance that then returns towards pre-lesion levels after additional days of training. Importantly, the impairment following the post-training lesions appears to affect adaptively timed CRs specifically, i.e. those in which the eyelid is closed at the time of airpuff delivery. Thus, the rabbits cannot use the vibrissae afferent information adaptively in forebrain-dependent trace EBC, at least initially after the post-training lesion and before retraining. This is further evidence that the rabbits can “perceive” the whisker vibration CS after the barrel cortex lesion and suggests that cerebellar-mediated timing control is impaired by the loss of cortico-cerebellar afferents. These results suggest that the barrel cortex could be a site for long term storage of an important aspect of the association, and that the storage may be mediated partly by the expansion of the barrels representing conditioned whiskers (Figure 6). This expansion may be due to the development of new synapses or to the expansion of existing synapses by the insertion of additional AMPA receptors (Lisman, 2003).

Figure 6.

Whisker-signalled conditioning increases the size of cortical barrels as detected with cytochrome oxidase staining. The increase may be the result of increased dendritic growth or increased number of synapses (by synaptogenesis or activation of silent synapses), or a combination of both, as portrayed in this cartoon illustration.

In addition to using lesion techniques to determine if the barrel cortex is necessary to learn the association, we have begun to examine multiple single neuron activity in the barrel cortex of conditioned and non-conditioned whiskers during learning. The focus of this ongoing study is to determine if learning the trace association modulates conditioned cortical barrel single unit neuronal activity, and if this modulated response could account for the conditioning induced change in behavior, i.e. an increase in the number of CRs. We monitored single-unit neuronal activity in the barrel cortex with independently movable multi-channel electrode arrays. Our preliminary data indicate that approximately 10% of the neurons sampled in the conditioned barrels (CS Whiskers) exhibit a significant increase in firing rate during the CS, but only 0.7% in non-conditioned barrels (Non-CS whiskers). Given that we use a low amplitude vibration as a CS, we are not surprised by the low number of significantly responsive neurons in both conditioned and non-conditioned barrels, especially since barrel cortical neurons predominantly receive input from a single whisker and exhibit preferences for both the angle and frequency of deflection, which we have not optimized. However, the difference between the percentage of responding conditioned and control neurons is significantly different, and these results further suggest that the barrel cortex is not only modulated by conditioning, but could be a potential site for long-term storage for trace-eyeblink associations.

Lastly, we have been using fMRI in order to examine large areas of brain simultaneously and repeatedly over the course of learning. The rabbit is ideal for this type of experiment since it appears to tolerate restraint very well. We have demonstrated activation of the visual cortex (and lateral geniculate nucleus) with light flashes (Wyrwicz et al., 2000) and activation of the cerebellar nucleus and deactivation of the cerebellar cortex during delay conditioning with a visual conditioning stimulus (Miller et al., 2003). Recently we have been examining the whisker barrel cortex in order to utilize the well defined somatotopy of the barrel cortex (Talk et al., 2006), and plan to use vibration of the whiskers as a CS during fMRI of conditioning processes.

In addition to CS-specific input, the somatosensory cortex also receives input from the eye and periorbital region which are stimulated by the airpuff (or shock) US during conditioning. Modulation of the response to the US in this area as conditioning progresses is also possible. In fact, Wikgren et al. (2003) recorded form rabbit somatosensory cortex during delay conditioning (tone CS, airpuff US) and reported significant learning-specific increases in multiple unit activity that “modeled” the CR. The exact location of the recordings was not reported, but probably included the eye zone and reflect the impact of the US or an efference copy of the CR since the increased neural activity was not present on trials where the CR was not emitted.

The idea that primary sensory cortex plays a role in long-term-memory storage of trace-associations is not novel (Weinberger et al., 1993). Various paradigms involving different sensory cortical regions have been demonstrated to exhibit experience-dependent plasticity. For example, focal retinal lesions induce a topographic reorganization in primary visual cortex (Darian-Smith & Gilbert, 1994, 1995). Training a subject to respond to a specific orientation of a visual stimulus alters both the sensitivity and the preferred orientation of receptive fields within primary visual cortex (Schoups et al., 2001; Ghose et al., 2002). Auditory frequency discrimination training shifts the preferred frequency of neurons towards that of the rewarded frequency (Disterhoft & Stuart, 1976; Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005). We showed that auditory cortex neurons changed their firing patterns to a tone CS at their preferred frequency during delay eyeblink conditioning in rabbits (Kraus & Disterhoft, 1982). Tactile discrimination alters the somatosensory cortical representation of the hand (Jenkins et al., 1990; Recanzone et al., 1992) following stimulation of the digits, and neuronal firing rates increase in primary somatosensory barrel cortex following whisker stimulation in a non-learning context (Krupa et al., 2004). However, the cerebellum is likely to be involved as well when cortical plasticity is associated with a conditioned response. The two regions then need to interact, most likely through the thalamus or pons with important contributions from the prefrontal cortex.

Aside from the primary sensory cortex changing with learning, the secondary association cortex may change as well. Gould’s (1986) electrophysiological mapping study of the rabbit somatosensory cortex revealed a second adjacent “map” of the body oriented as an approximate mirror image of the map in SI. This area, referred to as SII, is smaller than SI and contains neuronal clusters that have relatively larger receptive fields. As in other mammals the representations of the different body surfaces are less disproportionately represented in SII than in SI, and the receptive fields of SII neurons, as for SI neurons, are mostly contralateral. Hoffer et al., (2003) examined rats for the pattern of SII afferents from SI and found that labeled fibers from the same barrel row overlap in SII more than do projections from different barrel rows; similar results were found for the mouse (Carvell & Simons, 1986). This indicates that SII facilitates the integration of sensory information received from neighboring barrels that represent whiskers in the same row. Additionally, Alloway, Mutic Hoffer and Hoover (2000) found that projections from both SI and SII exhibit substantial amounts of divergence within the dorsolateral striatum. Tracer injections in both cortical areas also produced dense anterograde and retrograde labeling in the thalamus, especially in the ventrobasal complex (VB) and in the medial part of the posterior (POm) nucleus, i.e., regions that represent the whiskers.

The finding of conditioning specific changes in barrel cortex is thus not surprising. The cortex, especially sensory, sensory association cortices, and entorhinal cortex are obvious candidates for the permanent repository of memories, and the connections of the cAC (Weible, Weiss & Disterhoft, submitted) suggest that brain regions such as the caudate nucleus and / or claustrum within the basal ganglia may serve to integrate the CS and US across cortical regions and project information ultimately to the pontine nuclei before reaching the cerebellum.

Basal Ganglia

The main afferents of the basal ganglia have been shown in several species, including the rabbit (Carman, Cowan & Powell, 1963), to arise in an orderly manner from all areas of cortex (layer 5) to the striatum (caudate and putamen). A major afferent source of fibers originates from the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta. The main efferent targets are the globus pallidus and the substantia nigra pars reticulata which then projects to the VA thalamus, and lesions of the substantia nigra retard acquisition of EBC when tone and periorbital shock are paired in a trace 0 (delay) paradigm (Kao & Powell, 1988). In terms of forebrain-cerebellar interactions, it is important to note that Peter Strick’s laboratory (Hoshi et al., 2005) has demonstrated a disynaptic connection from the cerebellar nuclei to the striatum in nonhuman primate that could mediate on-line correction or adjustments of ongoing motor programs. Kelly and Strick (2003) demonstrated separate output channels from the cerebellar nuclei to prefrontal and motor areas of the cortex with transneuronal transport of herpes simplex virus. The functional impact of these connections was shown by Pasupathy and Miller (2005) while recording from the caudate and areas 9 and 46 of the PFC in monkeys trained to make reversals of a newly acquired memory guided saccadic eye movements to one of two potential targets. They found that caudate neurons exhibited a rapid and robust change in firing rate and directional selectivity for the saccade after the reversal as compared to neurons from the PFC (those neurons exhibited a slower shift in directional selectivity). This result suggests that the striatum may play a teaching role for the frontal cortex, probably via dopaminergic input to the striatum. The PFC can then modulate the pontine nuclei or thalamus to affect the cerebellum.

Responses of rabbit striatal neurons have been examined during delay EBC (White et al., 1994) and were found to be similar to those of the hippocampus during delay EBC, i.e, responses to the US were found early in training and responses during the CR were observed later in training. The response latencies (relative to CR onset) were short (10–50 ms) suggesting that the activity is involved in the initial generation rather than the expression of the CR (cerebellar nuclear neurons have a 40–80 ms lead relative to the CR), and responses to the CS were rare. Recently, Graybiel and colleagues (Blazquez et al., 2002) examined the monkey striatum during a variety of tasks, including delay EBC with a tone CS. Importantly, they only examined a single cell type, the tonically active interneurons (TANs) and found that the population of responses was tightly coupled to the probability that a stimulus would evoke a CR. The percent of responding cells increased from 11–92% as the percent of CRs increased to a plateau level, and then decreased from 100% responders to 40% during extinction training. In addition to electrophysiological recording studies, lesions of basal ganglia have also been done, but only with delay EBC. Delay eyeblink conditioning is disrupted but not abolished by lesions of the caudate (Powell et al., 1978), substantia nigra (Kao & Powell, 1988), or injection of neuroleptic drugs (Harvey & Gormezano, 1981; Sears & Steinmetz, 1990).

Other learning paradigms have been used during striatal recordings as well, e.g., studies of maze running in rats indicate that the striatum is involved in associative motor learning, especially as new movements are established as habits (Barnes, Kubota, Hu, Jin & Graybiel, 2005). Barnes et al. (2005) also found that during a discriminative T maze task, the activity of rat striatal neurons changed from being active during exploration of the main alley to being active at the start and end of each run. This learning dependent change tended to reverse itself during extinction training (when no reward was present). Interestingly, the avian homologue of the basal ganglia is also involved in song learning rather than song production (Doupe, Perkel, Reiner & Stern, 2005; Farries, Ding & Perkel, 2005).

Other studies with maze running tasks also suggest that the caudate may be more involved in integrating cortical relationships rather than being the site of permanent memory, i.e., disruption of the circuit immediately after training, but not an hour or more later impairs retention of a learned task (Wyers et al., 1968; Gold & King, 1972; Wyers & Deadwyler, 1971). Lastly, activation of a single whisker in unanesthetized rats was sufficient to increase glucose utilization within the caudate and in a single column of SI cortex (Brown et al., 1996). These studies suggest that whisker stimulation during trace eyeblink conditioning should be sufficient to activate the striatum, and that caudate lesions done prior to conditioning should cause an impairment relative to nonlesioned controls. This remains to be tested with trace conditioning procedures.

The results from these various experiments on the basal ganglia suggest an important role for the striatum in EBC, perhaps as a mediator of information flow from prefrontal association cortex to rostral motor areas that are involved in “cognitive” motor control (McFarland & Haber, 2002). However, since Graybiel and colleagues used delay conditioning, which can still be retained in decerebrate rabbits (Mauk & Thompson, 1987), a direct examination of striatal responsivity during forebrain dependent EBC is necessary to confirm its role during forebrain-cerebellar interactions.

Claustrum

The claustrum is included here since it was found to have dense and reciprocal connections with the cAC (Weible, Weiss & Disterhoft, submitted). The main mass of the striatum consists of the caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus; while the claustrum, subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra are usually included in the basal ganglia as a whole (Brodal, 1981). However, the claustrum is derived from the insular lobe of the cerebral cortex, and the caudate and putamen are derived from the telencephalon. The claustrum receives an orderly projection from all parts of cortex (Carman, Cowan & Powell, 1964, Druga, 1968; Machi, Bentivoglio, Minciacchi, et al., 1978), projects to both the subiculum (Amaral & Cowan, 1980) and the caudate (Arikuni & Kubota, 1985), and is found in all mammals examined so far (Kowianski et al, 1999). These connections would enable the claustrum to bind together different components of a single episode. This type of processing was revealed with a human imaging study that revealed activation of the claustrum with a cross-modal matching task (Hadjikhani & Roland, 1998).

The claustrum is connected reciprocally and bilaterally with a broad range of neocortical sensory and motor areas (Norita, 1977; Hughes, 1980; Macchi et al., 1981; Markowitsch et al., 1984; Minciacchi et al., 1985; Sloniewski et al., 1986) and allocortical structures (Markowitsch et al., 1984). Neurons of the claustrum are also responsive to unimodal and polymodal sensory stimulation (Chaichich & Powell, 2004). The claustrum is generally organized so that the cortex connects to the closest part of it, i.e. rostral to rostral, caudal to caudal. Thus, the anterior dorsal part tends to be somatosensory and motor related, the posterior dorsal tends to be visual, and the posterior ventral tends to be auditory (Narkiewicz, 1964). Discrete visual and somatosensory subdivisions of the claustrum have been demonstrated electrophysiologically as well (Olson & Graybiel, 1980). This relationship also exits in the rabbit (Kowianski et al., 2000). The principal cells of the claustrum have reciprocal connections with the cortex, mostly to layer 4, but also to layer 6. Crick and Koch (2005) proposed that the claustrum serves to bind temporally disparate events into a single percept that is experienced at one point in time. This is exactly what is needed to give behavioral significance to a CS that is initially neutral in trace EBC. In fact, Crick and Koch suggested using a trace conditioning paradigm to explore the function of the claustrum.

Reciprocal labeling was also observed with multiple thalamic nuclei. Two of these, the medial dorsal (MD) and ventral lateral (VL) thalamic nuclei, receive direct projections from the dentate deep cerebellar nucleus (Stanton, 1980; Yamamoto et al., 1992; Middleton & Strick, 1994), which is critically involved with circuitry mediating the basic eyeblink conditioned response (Clark et al., 1984; McCormick & Thompson, 1984; Woodruff-Pak et al., 1985; Mauk & Thompson, 1987). Though early studies incorporating delay EBC questioned recruitment of the MD and VL thalamic nuclei during training (Gabriel et al., 1996; Sears et al., 1996), Powell and Churchwell (2002) recently demonstrated that MD lesions retarded acquisition of trace EBC with a peri-orbital shock US.

Hippocampus and Cortex

The classic trisynaptic circuit of the hippocampus includes projections from the entorhinal cortex (EC) to dentate gyrus, to area CA3, and then to CA1. CA1 then projects outside the hippocampus proper to the subiculum which projects to the medial frontal cortex and caudal cingulate gyrus (Rosene & Hosen, 1977; Goldman-Rakic, Selemon & Schwartz, 1984). Among these regions, area CA1 and CA3 have been extensively studied with simple delay conditioning. Many of the pyramidal neurons exhibit what has become known as “neural models” of behavior, i.e., the activity profiles of the neurons in terms of rate by time, resemble the patterns of CRs in terms of amplitude of response by time.

There are also feedback loops between the EC and the hippocampus such that superficial and deep EC neurons project to and receive projections from the hippocampus, respectively (Gnatkovsky & de Curtis, 2006; Kloosterman et al., 2003). More specifically, layer II of EC projects to dentate gyrus, and layer III of EC projects to CA1 and CA3; the subiculum and CA1 both project back to the EC (Kloosterman et al., 2004). The projections from EC back to association cortex could mediate the binding of multiple representations for a common episode that is one of the more likely roles of the hippocampus in episodic memory formation (Cohen, Ryan, et al., 1999), especially since lesions of the EC in monkeys disrupt the flexible manipulation of memory required for challenging tasks such as paired associate learning (Buckmaster, Eichenbaum, Amaral, Suzuki & Rapp, 2004). The binding of sensory information should also account for contextual fear conditioning (Corcoran, Desmond, Frey & Maren, 2005) and trace EBC. In addition, the reciprocating circuits between hippocampus / subiculum and EC provide a neural substrate for the EC to serve as a comparator of hippocampal input and output, and to adjust its output to CA1 and CA3 in order to change the temporal firing sequence of different CA1 neurons (Lorincz & Buzsaki, 2000; Yamaguchi, 2003). Furthermore, layer V neurons in the entorhinal cortex exhibit calcium and muscarinic dependent graded changes in firing frequency that remain stable after each of several consecutive depolarizing stimuli (Egorov et al., 2002). Parts of this theory have been used to explain the change in the temporal order of firing of neurons with adjacent place fields. However, the theory could also be used to explain the gradual and parallel shortening of the onset latency for the CR and CA1 hippocampal unit activity that occurs during delay EBC (Berger & Thompson 1978; Weiss, Kronforst-Collins & Disterhoft, 1996). Similar CA1 “neural models” of the CR during trace EBC have not been as obvious (Weiss, Kronforst-Collins & Disterhoft, 1996; McEchron & Disterhoft, 1999; Weible et al., 2006), but perhaps the “modeling” is more likely to be found in the EC given its potential role as a comparator of hippocampal input and output.

Thalamus

The cortex can affect the pontine nuclei directly, and hence the cerebellum, but cooperative interactions of the cortex and cerebellum require feedback from one region to the other. The thalamic nuclei, especially the anterior-ventral (AV) and ventral-anterior (VA) nuclei, are situated to provide such feedback. Weiss and Disterhoft (1996) proposed that the VA nucleus would provide feedback from the cerebellum to the frontal cortex, and that the AV thalamus would provide feedback from the hippocampus (via the subiculum) to the frontal cortex. Missing from this discussion was the role of the MD thalamus which receives input from the cerebellum and projects to most of the medial wall of the cortex rostral to the corpus callosum, including the cAC (Benjamin, Jackson & Golden, 1978; Weible et al., submitted; Vogt et al., 1992), and which has long been known to be involved in working memory (Markowitsch, 1982). The MD thalamus projects to the dlPFC which has neurons that appear to mediate a memory trace during delayed matching to sample tasks in primates, and there must be reciprocal connections since cooling the dlPFC diminishes spontaneous firing of MD neurons (Alexander & Fuster, 1973). In regards to EBC, knife cuts that disconnect the MD thalamus from the PFC retard acquisition of trace 0 conditioning with a periorbital shock US (Buchanan & Powell, 1988), as do lesions of the MD thalamus (Buchanan, 1994). We assume the effect would be more severe with a hippocampally-dependent trace interval, especially since monkeys are impaired on a delayed response task when their prefrontal cortex temperature was lowered to between 15 and 20 degrees centigrade (Alexander & Fuster, 1973; Bauer & Fuster, 1976). A comparison of the MD and AV “cognitive” thalamic nuclei with the VA “somatomotor” thalamus, in relation to the activity in the PFC, should help to understand better the role of the thalamic nuclei in acquisition and consolidation of trace EBC.

The role of the AV thalamus is especially interesting in light of the memory impairment associated with Korsakoff’s syndrome where the mamillary bodies and thalamus degenerate due to thiamine deficiency. The amnestic subtype of these patients have impaired delay EBC (McGlinchey-Berroth et al., 1995) in addition to the impaired declarative memory, and Harding et al. (2000) determined that the amnesia is specific to those patients with additional neuronal loss in the anterior thalamic nucleus.

The posterior thalamic nucleus (PO) also needs to be examined since neurons in this region exhibit large learning related changes in firing rates early in the trial sequence of a tone discriminative learning task for food reinforcement (Disterhoft & Olds, 1972). This increase may be due to presynaptic inhibition of inhibitory zona incerta afferents into the medial PO nucleus (Masri et al., 2006). A small percentage of POm neurons also respond to noxious stimuli (Chiaia, Rhoades, Fish & Killackey, 1991), and receive projections from SI and SII. Changes in the responsiveness of neurons coding for noxious stimuli may account for learning that occurs even though the US is still delivered, as in the case of conditioning with a periorbital shock US. In this situation the subject does not avoid or even escape the shock, but if neurons coding for pain are functionally inhibited, the CR may mediate a reward (perhaps by changes in the dopamine system) to further facilitate conditioning.

Acetylcholine, Dopamine and the Basal Forebrain / Midbrain

An important constraint on memory formation in the hippocampal-entorhinal system is the level of neuromodulation by acetylcholine (ACh). Cholinergic neurons in the NBM and nucleus accumbens as well as within the medial septum provide input to the cortex and hippocampus respectively, and lesions of the NBM in rabbits prior to conditioning reduce the amount of heart rate conditioning while having no affect on EBC (Ginn & Powell, 1992). Higher levels of ACh correlate with larger amplitude theta oscillations, and cholinergic blockade reduces theta oscillation amplitude (Monmaur et al., 1997). Hasselmo (1999) has suggested that higher tonic levels of ACh during arousal increases the activitiy of inhibitory interneurons, suppresses hippocampal feedback to the EC, and leaves transmission from EC→CA1 and EC→CA3 intact (Hasselmo & Schnell, 1994; Sarter, Hasselmo, Bruno & Givens, 2005) such that the sensory representations are not distorted. In contrast, during slow-wave sleep or quiet wakefulness, less ACh (Marrosu et al., 1995) allows feedback from the hippocampus back to cortical association areas (Power, 2004; Gais & Born, 2004). These effects may well be associated with the theory that memory is consolidated during slow wave sleep (Wilson & McNaughton, 1994).

Many of the studies on the cholinergic system and learning were done with rats, but the rabbit brain has also been examined (Varga et al., 2003) and found to have cholinergic projection neurons in the medial septum, vertical and horizontal diagonal bands of Broca, ventral pallidum, and the NBM / substantia innominata complex. Dense NGF binding sites (a marker for the cholinergic system) have also been found in the rabbit caudate-putamen, but not after quinolinic lesions of intrinsic neurons, suggesting the presence of cholinergic interneurons (Altar et al., 1991). Furthermore, intrastriatal injections of choline facilitate acquisition of an autoshaping lever pressing task in rats (Diaz del Guante et al, 1993), and scopolamine impaired a passive avoidance task when administered 2 min, but not 15 min after training (Diaz del Guante et al., 1991) which suggests a role in acquisition, but not a site of consolidation.

Our recent tract tracing study of the cAC (Weible et al., submitted) demonstrated projections to all these areas (except medial septum and vertical limb of DBB). In relation to EBC, Buchanan et al. (1997) found that lesions of the basal forebrain retarded, but did not prevent acquisition of delay EBC, and scopolamine (a muscarinic antagonist) prevents trace, but not delay EBC (Kaneko & Thompson, 1997). Also, we have shown that cholinergic agonists facilitate acquisition of trace EBC in aging rabbits and increase the excitability of their CA1 pyramidal neurons (Disterhoft & Oh, 2003; Weiss et al., 2000; Weible et al., 2004). The effects of cholinergic modulation can be quite substantial as demonstrated by the massive reorganization of the rat auditory cortex which favors the expansion of the representation for a tone frequency that was paired repeatedly with electrical stimulation of the nucleus basalis (Kilgard & Merzenich, 1998). A similar reorganization of the best frequency towards that which was used for training for auditory neurons has been demonstrated as a result of fear conditioning and it has been proposed that cholinergic input plays an important role in this reorganization (Weinberger, 1996). These results suggest that the firing properties of basal forebrain neurons should be examined further during trace EBC.

The dopaminergic system also needs to be examined to fully understand the mechanisms mediating forebrain-dependent EBC. This system, arising from the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (VTA), is often referred to as mediating a teaching role during associative learning that might mediate consolidation of memory. Hyvarinen et al. (2006) recently reported that post-trial hypothalamic stimulation facilitated trace EBC in rabbits presumably by the activation of glutamatergic and dopaminergic fibers (You, Chen & Wise, 2001). Other learning paradigms are also facilitated by dopamine. White and Viaud (1991) injected d-amphetamine or a dopamine D2 agonist into the rat caudate and facilitated conditional emotional responses to a visual or olfactory cue depending upon whether they injected the postereoventral or ventrolateral part respectively. Schultz and colleagues (Ljungberg, Apicella & Schultz 1992; Schultz et al., 1993; Mirenowicz & Schultz, 1994) recorded from nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in the monkey and found neurons that respond to unexpected rewards, such as food or fruit juice, but not to the same stimuli after learning had consolidated. A similar result was found in monkeys trained to make memory guided saccades (Kawagoe, Takikawa & Hikosaka, 2004). The results indicated that the dopaminergic neurons responded to the juice reward when the monkey was not being trained, and to the cue when the monkey was doing the task, but only if one of several cues was being rewarded; the response was not evident if all cues were rewarded. The activity of these neurons may “teach” that a new behavior is required to obtain a reward; and the activity would decrease as the behavior becomes consolidated, perhaps by feedback form the hippocampal-prefrontal-striatal system (Eblin & Graybiel, 1995) as reward prediction errors are minimized (Waelti, Dickinson & Schultz, 2001). The mechanism mediating the dopaminergic dependent striatal association may be LTD at the cortico-striatal synapse since Calabresi et al. (1992) have reported that 6-OHDA lesions prevent LTD in striatal slices, unless a dopamine agonist was added to the bath, and Aosaki et al. (1994) found that unilateral MPTP lesions of the striatum eliminated CR-related activity of the tonically active neurons, but did not alter spontaneous activity, or the CR in well trained animals where the reward was no longer unexpected. Feedback to the dopaminergic system could originate from the ventral subiculum since Floresco et al. (2001) reported that infusions of NMDA into the ventral subiculum increased the spontaneous firing of dopaminergic cells, an effect that was abolished by infusions of kynurenic acid (a glutamate receptor antagonist) into the nucleus accumbens. The authors suggest that the ventral subiculum activates the nucleus accumbens which inhibits the ventral pallidum and releases the tonic inhibitory drive upon the VTA so that the number of spontaneously firing dopaminergic cells increases.

Pontine Nuclei

Several studies indicate that the lateral pontine nuclei (LPN) are part of the CS pathway mediating delay EBC (Knowlton & Thompson, 1988; Berger & Bassett 1992; Cartford et al., 1997; Clark et al., 1997; Bao, Chen & Thompson, 2000), including the finding that electrical stimulation of the LPN serves as an effective CS (Steinmetz et al. 1989; Castro-Alamancos & Borrell 1993; Tracy & Steinmetz 1998). However, the LPN are believed to be a relay for CS information during delay EBC, rather than a site of plasticity for the learned response (Tracy et al. 1998).

The pontine nuclei receive extensive projections from the cortex and other regions. Leergaard et al. (2004) found that cortical and subcortical pathways through the basal ganglia and cerebellum are anatomically segregated at the level of the pons. The SI, SII, and MI projections demonstrated that whisker-related projections from SI and MI are largely segregated. Furthermore, SI contributes significantly more corticopontine projections than MI, and the SI/SII projections to the pons exhibit more overlap than do the SI/SII projections to the striatum. These structural differences indicate a larger capacity for integration of information within the same sensory modality in the pontocerebellar system compared to the basal ganglia which has more widely overlapping projections. Thus, the sensory integration could be occurring in the cortex and striatum and then project to the cerebellum via the pontine nuclei.

We proposed that direct projections from the cAC to the LPN (Weible et al., submitted) may be important to the conditioning of auditory stimuli, given the proposed role for the LPN as a relay for auditory-CS information, and we expect the same for somatosensory stimuli. During tone signaled conditioning, CS-excitatory neurons in the cAC of trace conditioned subjects maintained significantly elevated firing rates during the first 250 ms of the 500 ms trace interval throughout the first four days of training. This activity could prolong the effect of the CS by continuing to stimulate the LPN after tone offset as proposed by Weiss and Disterhoft (1996). In this way, the LPN could function as a relay signaling CS presentation to the cerebellar circuit. The relay could be direct, i.e., to the same pontine cells that project to the cerebellar cortex and deep nucleus, or the cAC could be projecting to one or more populations of pontine cells that then project onto the cells that ultimately project into the cerebellum. More experiments are needed to answer these questions.

Conclusions

In summary, we have taken advantage of the forebrain-dependent trace eyeblink conditioning paradigm to investigate cerebro-cerebellar interactions during learning. A concentrated series of lesion, recording, and tract tracing studies in the caudal anterior cingulate gyrus revealed that neurons in this part of cortex are necessary for acquisition of CRs. Although the electrophysiological responses suggest that the area is not necessary for retention of CRs, the tract tracing studies revealed several regions, including the caudate, claustrum, and thalamic nuclei which might help to consolidate the neural substrate of the trace CR. We are currently investigating these regions. Our investigations of hippocampal physiology, both in vitro and in vivo, also indicate that it is a substrate for temporary storage during learning rather than a site of consolidated memories. Most recently we have been investigating the sensory cortex for a site of consolidated memories. Our data indicate that it is a likely site for memory storage of learning specific changes regarding the whisker-vibration CS. The role of the caudate and claustrum may then be to bind together information from different cortical areas with help from the thalamic nuclei. This integration of CS and US information is obviously necessary to associate the CS and US in order to produce a CR. Our transition to the whisker barrel system in the rabbit has facilitated our studies in the sensory cortex and has let us use multiple single neuron recording, cytochrome oxidase activity, site specific lesions, and fMRI to investigate learning-related changes that may mediate memory. We anticipate that our paradigm and methodology will become even more informative as we continue to explore cerebro-cerebellar interactions during learning.

Acknowledgements

Supported by: R01-MH47340 (JFD) and RO1 NS44617 to A.M. Wyrwicz.

References

- Aiba A, Kano M, Chen C, Stanton ME, Fox GD, Herrup K, Zwingman TA, Tonegawa S. Deficient cerebellar long-term depression and impaired motor learning in mGluR1 mutant mice. Cell. 1994;79(2):377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Fuster JM. Effects of cooling prefrontal cortex on cell firing in the nucleus medialis dorsalis. Brain Res. 1973;61:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway KD, Mutic JJ, Hoffer ZS, Hoover JE. Overlapping corticostriatal projections from the rodent vibrissal representations in primary and secondary somatosensory cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428(4):51–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Dugich-Djordjevic M, Armanini M, Bakhit C. Medial-to-lateral gradient of neostriatal NGF receptors: relationship to cholinergic neurons and NGF-like immunoreactivity. J Neurosci. 1991;11(3):828–836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00828.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Cowan WM. Subcortical afferents to the hippocampal formation in the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1980;189(4):573–591. doi: 10.1002/cne.901890402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Graybiel AM, Kimura M. Effect of the nigrostriatal dopamine system on acquired neural responses in the striatum of behaving monkeys. Science. 1994;265(5170):412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.8023166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikuni T, Ban T., Jr Subcortical afferents to the prefrontal cortex in rabbits. Exp Brain Res. 1978;32(1):69–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00237391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikuni T, Kubota K. Claustral and amygdaloid afferents to the head of the caudate nucleus in macaque monkeys. Neurosci Res. 1985;2(4):239–254. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(85)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah HE, Frank MJ, O'Reilly RC. Hippocampus, cortex, and basal ganglia: insights from computational models of complementary learning systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82(3):253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chen L, Qiao X, Knusel B, Thompson RF. Impaired eye-blink conditioning in waggler, a mutant mouse with cerebellar BDNF deficiency. Learn Mem. 1998;5(4–5):355–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chen L, Thompson RF. Learning- and cerebellum-dependent neuronal activity in the lateral pontine nucleus. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114(2):254–261. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TD, Kubota Y, Hu D, Jin DZ, Graybiel AM. Activity of striatal neurons reflects dynamic encoding and recoding of procedural memories. Nature. 2005;437(7062):1158–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217(4558):408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer RH, Fuster JM. Delayed-matching and delayed-response deficit from cooling dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1976;90(3):293–302. doi: 10.1037/h0087996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PJ, Gold JJ, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. The neuroanatomy of remote memory. Neuron. 2005;46(5):799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin RM, Jackson JC, Golden GT. Cortical projections of the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1978;141(2):251–265. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger TW, Alger B, Thompson RF. Neuronal substrate of classical conditioning in the hippocampus. Science. 1976;192:483–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1257783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger TW, Bassett JL. System properties of the hippocampus. In: Gormezano I, Wasserman EA, editors. Learning and memory: The behavioral and biological substrates. Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Berger TW, Thompson RF. Neuronal plasticity in the limbic system during classical conditioning of the rabbit nictitating membrane response. II: Septum and mammillary bodies. Brain Res. 1978;156(2):293–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez PM, Fujii N, Kojima J, Graybiel AM. A network representation of response probability in the striatum. Neuron. 2002;33(6):973–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracha V, Zhao L, Irwin KB, Bloedel JR. The human cerebellum and associative learning: dissociation between the acquisition, retention and extinction of conditioned eyeblinks. Brain Res. 2000;860(1–2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal A. Neurological anatomy in relation to clinical medicine. 3rd Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LL, Hand PJ, Divac I. Representation of a single vibrissa in the rat neostriatum: peaks of energy metabolism reveal a distributed functional module. Neuroscience. 1996;75(3):717–728. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL. Mediodorsal thalamic lesions impair acquisition of an eyeblink avoidance response in rabbits. Behav Brain Res. 1994;65(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Powell DA, Thompson RH. Prefrontal projections to the medial nuclei of the dorsal thalamus in the rabbit. Neurosci Lett. 1989;106(1–2):55–59. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Penney J, Tebbutt D, Powell DA. Lesions of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and classical eyeblink conditioning under less-than-optimal stimulus conditions: role of partial reinforcement and interstimulus interval. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(5):1075–1085. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Powell DA. Parasagittal thalamic knife cuts retard Pavlovian eyeblink conditioning and abolish the tachycardiac component of the heart rate conditioned response. Brain Res Bull. 1988;21(5):723–729. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster CA, Eichenbaum H, Amaral DG, Suzuki WA, Rapp PR. Entorhinal cortex lesions disrupt the relational organization of memory in monkeys. J Neurosci. 2004;24(44):9811–9825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1532-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Maj R, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Long-term synaptic depression in the striatum: physiological and pharmacological characterization. J Neurosci. 1992;12(11):4224–4233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04224.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman JB, Cowan WM, Powell TP. The organization of cortico-striate connexionsin the rabbit. Brain. 1963;86:525–562. doi: 10.1093/brain/86.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman JB, Cowan WM, Powell TP. The cortical projection upon the claustrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964;27:46–51. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.27.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartford MC, Gohl EB, Singson M, Lavond DG. The effects of reversible inactivation of the red nucleus on learningrelated and auditory-evoked unit activity in the pontine nuclei of classically conditioned rabbits. Learning and Mem. 1997;3(6):519–531. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvell GE, Simons DJ. Somatotopic organization of the second somatosensory area (SII) in the cerebral cortex of the mouse. Somatosens Res. 1986;3(3):213–237. doi: 10.3109/07367228609144585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA, Borrell J. Active avoidance behavior using pontine nucleus stimulation as a conditioned stimulus in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1993;55(1):109–112. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90013-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chachich ME, Powell DA. The role of claustrum in Pavlovian heart rate conditioning in the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus): anatomical, electrophysiological, and lesion studies. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(3):514–525. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaia NL, Rhoades RW, Fish SE, Killackey HP. Thalamic processing of vibrissal information in the rat: II. Morphological and functional properties of medial ventral posterior nucleus and posterior nucleus neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1991;314(2):217–236. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian KM, Thompson RF. Neural substrates of eyeblink conditioning: acquisition and retention. Learn Mem. 2003;10(6):427–455. doi: 10.1101/lm.59603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GA, McCormick DA, Lavond DG, Thompson RF. Effects of lesions of the cerebellar nuclei on conditioned behavioral and hippocampal neuronal responses. Brain Res. 1984;291:125–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Gohl EB, Lavond DG. The learning-related activity that develops in the pontine nuclei during classical eye-blink conditioning is dependent on the interpositus nucleus. Learn Mem. 1997;3(6):532–544. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.6.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Ryan J, Hunt C, Romine L, Wszalek T, Nash C. Hippocampal system and declarative (relational) memory: summarizing the data from functional neuroimaging studies. Hippocampus. 1999;9(1):83–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:1<83::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Desmond TJ, Frey KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts the acquisition and contextual encoding of fear extinction. J Neurosci. 2005;25(39):8978–8987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Brain mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1982;17(11):55–63. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1982.11702412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer's disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219(4589):1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FC, Koch C. What is the function of the claustrum? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1458):1271–1279. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz L, Roe DL, Urbanc B, Cabral H, Stanley HE, Rosene DL. Age-related reduction in microcolumnar structure in area 46 of the rhesus monkey correlates with behavioral decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2004;101(45):15846–15851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Gilbert CD. Axonal sprouting accompanies functional reorganization in adult cat striate cortex. Nature. 1994;368:737–740. doi: 10.1038/368737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Gilbert CD. Topographic reorganization in the striate cortex of the adult cat and monkey is cortically mediated. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1631–1647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01631.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Weiss C, Disterhoft JF. Eyeblink conditioning in the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) with stimulation of the mystacial vibrissae as a conditioned stimulus. Behav. Neurosci. 2001;115:731–736. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum I, Schugens MM, Ackermann H, Lutzenberger W, Dichgans J, Birbaumer N. Classical conditioning after cerebellar lesions in humans. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(5):748–756. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Neural systems involved in fear-potentiated startle. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;563:165–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb42197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Schlesinger LS, Sorenson CA. Temporal specificity of fear conditioning: effects of different conditioned stimulus-unconditioned stimulus intervals on the fear-potentiated startle effect. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1989;15(4):295–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]